Submitted:

16 January 2025

Posted:

17 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

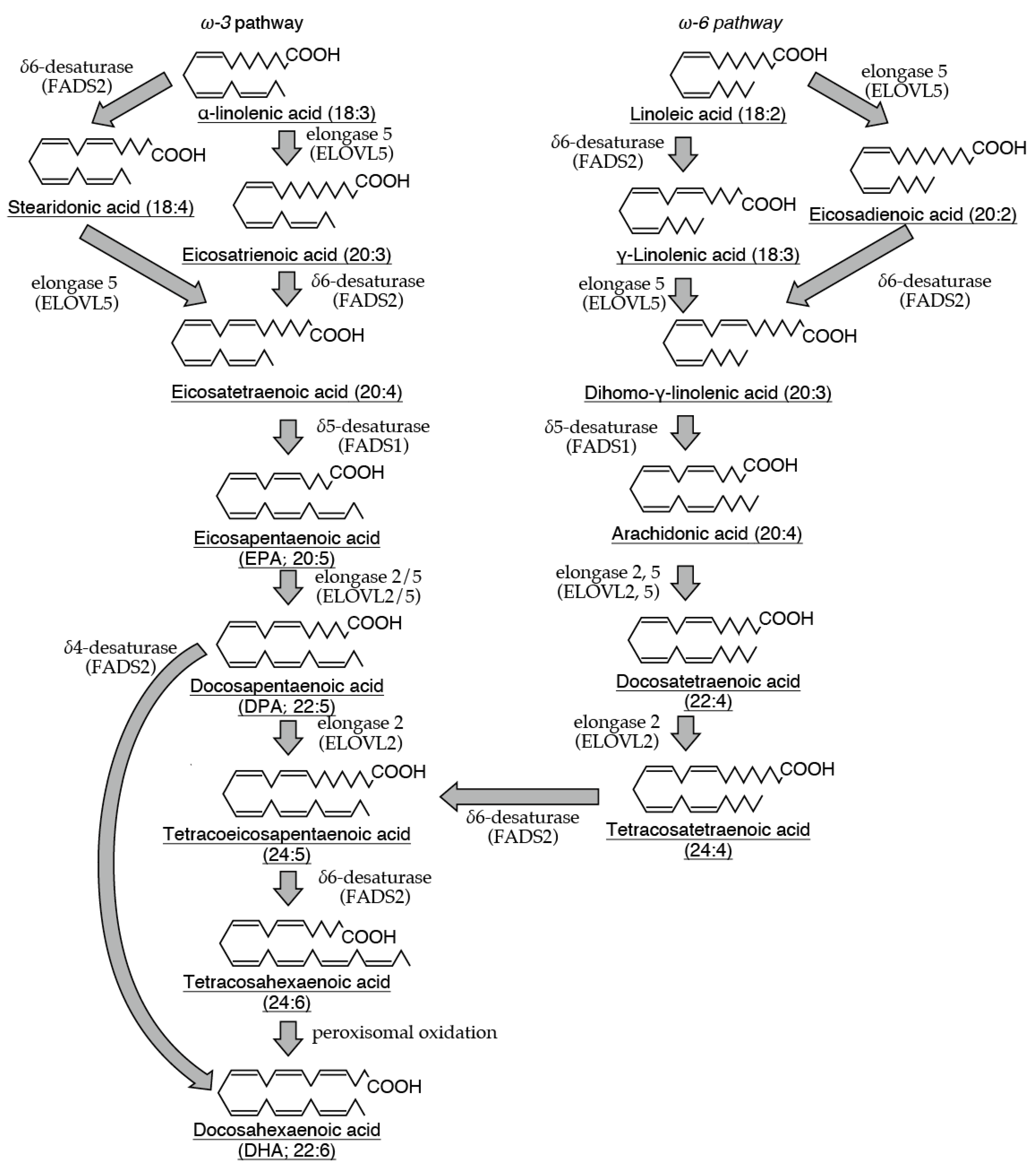

Many polyunsaturated fatty acids within cells exhibit diverse physiological functions. Particularly, arachidonic acid is the precursor of highly bioactive prostaglandins and leukotrienes, which are proinflammatory mediators. However, polyunsaturated fatty acids, such as arachidonic, docosahexaenoic, and eicosapentaenoic acids, can be metabolized into specialized proresolving mediators (SPMs), which have anti-inflammatory properties. Given that proinflammatory mediators and SPMs are produced via similar enzymatic pathways, SPMs can play a crucial role in mitigating excessive tissue damage induced by inflammation. Mast cells are immune cells that are widely distributed and strategically positioned at interfaces with the external environment, such as the skin and mucosa. As immune system sentinels, they respond to harmful pathogens and foreign substances. Upon activation, mast cells release various proinflammatory mediators, initiating an inflammatory response. Furthermore, these cells secrete factors that promote tissue repair and inhibit inflammation. This dual function positions mast cells as central regulators, balancing between the body’s defense mechanisms and the need to minimize tissue injury. This review investigates the production of SPMs by mast cells and their subsequent effects on these cells. By elucidating the intricate relationship between mast cells and SPMs, this review aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of the mechanism by which these cells regulate the delicate balance between tissue damage and repair at inflammatory sites, ultimately contributing to the resolution of inflammatory responses.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

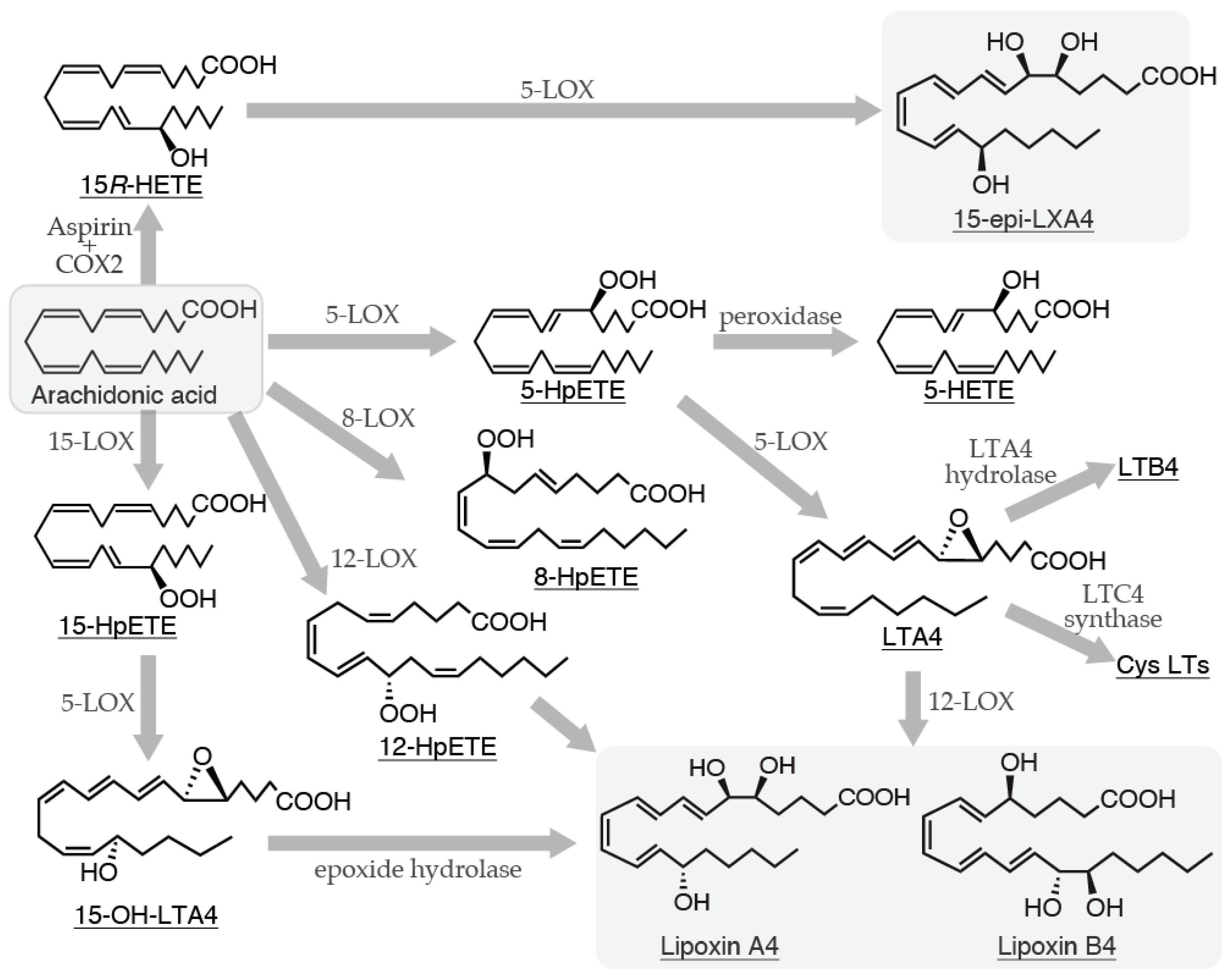

2. LXs

2.1). Biosynthetic Pathways of LXs and Their Relationship with Mast Cells

2.2). LX Receptors and Their Expression in Mast Cells

2.3). The Regulatory Role of LXs in Mast Cell Function

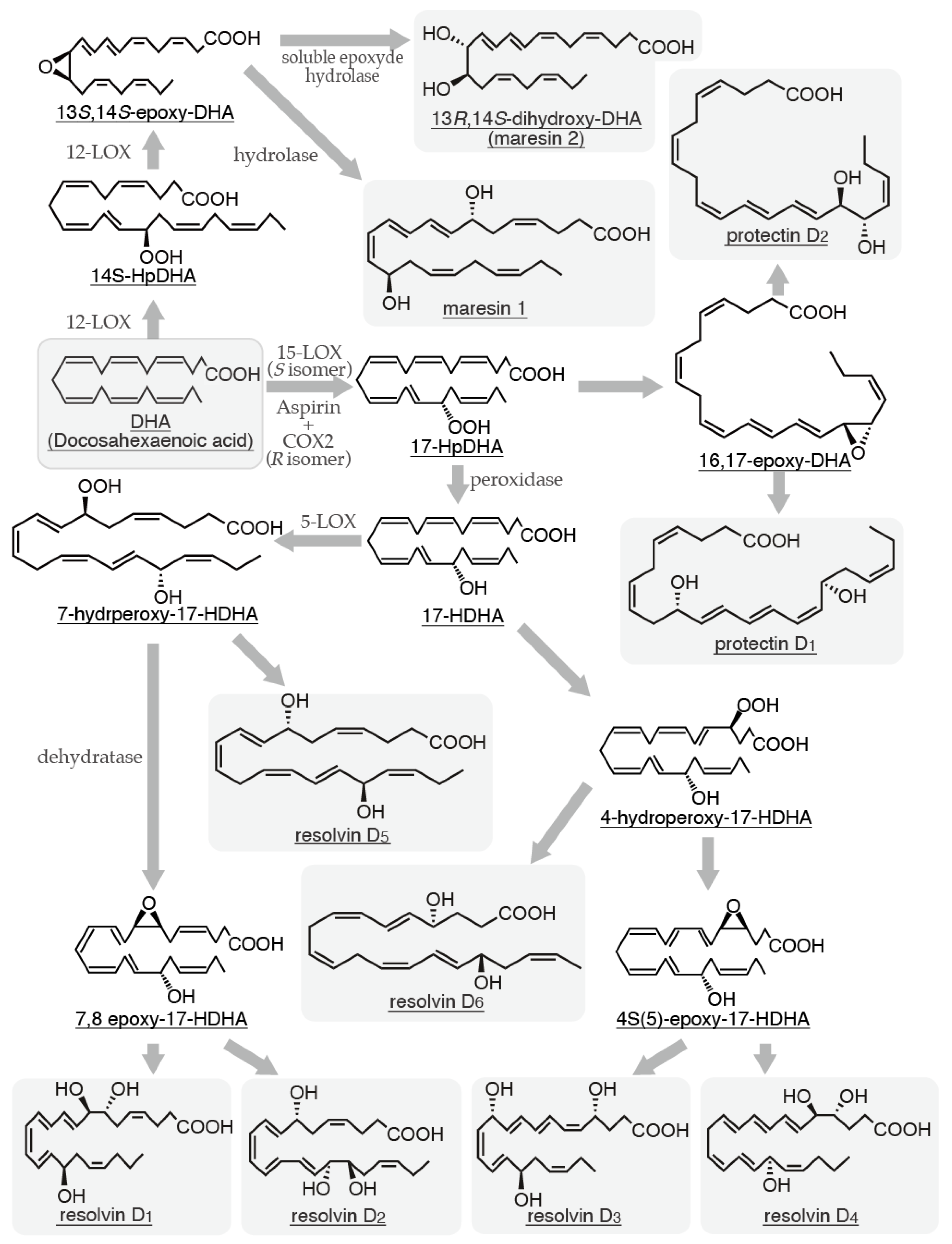

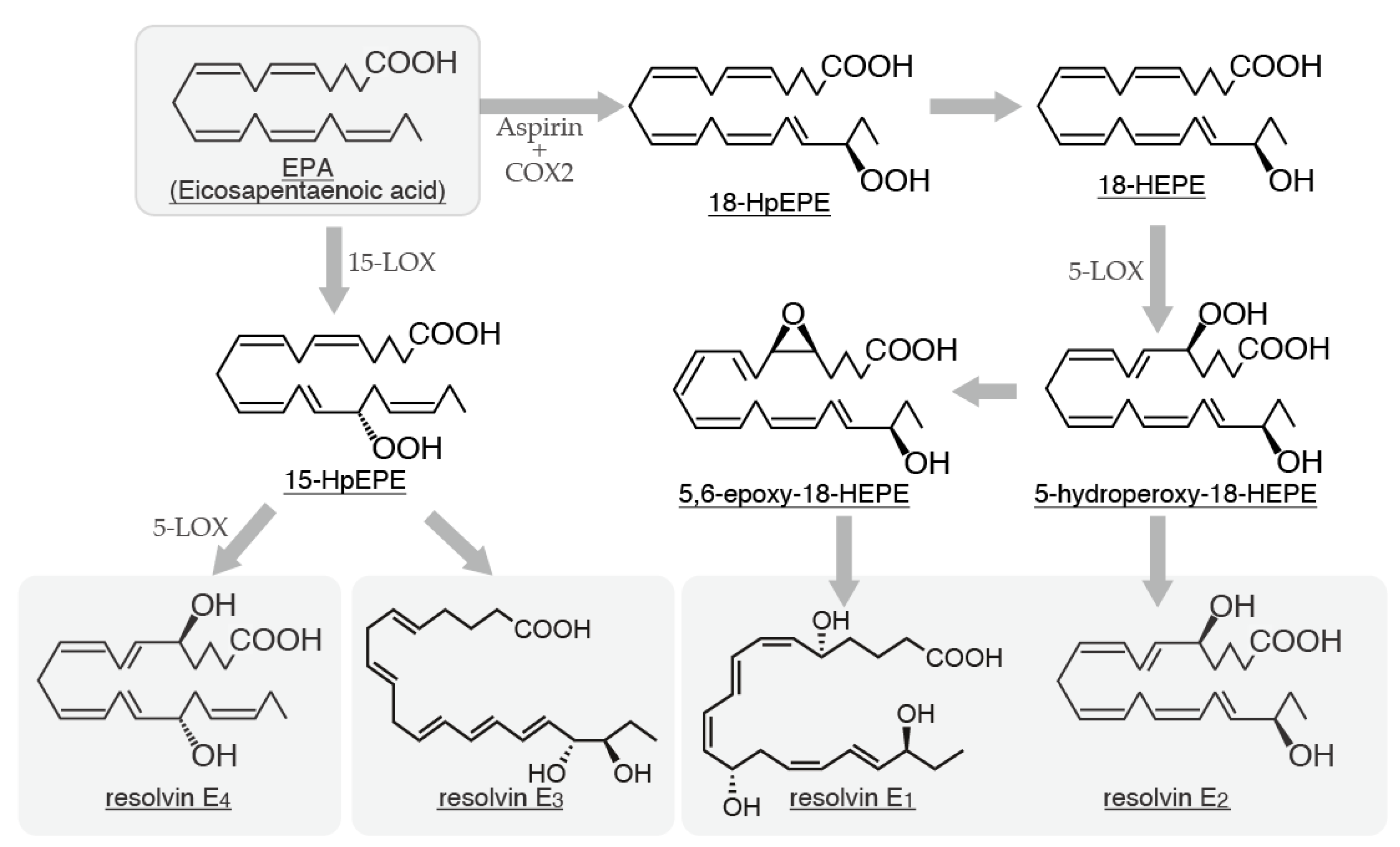

3. Rvs

3.1. Biosynthetic Pathways of Rvs and Their Relationship with Mast Cells

3.2. Resolvin Receptors and Their Expression in Mast Cells

3.3. The Regulatory Role of Rvs in Mast Cell Function

4. PD and MaRs

4.1. Biosynthetic Pathways of PD and MaRs and Their Relationships with Mast Cells

4.2. PD and MaR Receptors and Their Expression in Mast Cells

4.3. The Regulatory Role of PD and MaRs in Mast Cell Function

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

References

- Spector, A.A.; Kim, H.Y. Discovery of essential fatty acids. J Lipid Res. 2015, 56, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saini, R.K.; Keum, Y.S. Omega-3 and omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids: Dietary sources, metabolism, and significance - A review. Life Sci. 2018, 203, 255–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serhan,C. N.; Yacoubian,S.; Yang, R. Anti-inflammatory and pro-resolving lipid mediators. Annu Rev Pathol. 2008, 3, 279–312.

- Schwab, J.M.; Serhan, C.N. Lipoxins and new lipid mediators in the resolution of inflammation. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2006, 6, 414–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norling, L.V.; Serhan, C.N. Profiling in resolving inflammatory exudates identifies novel anti-inflammatory and pro-resolving mediators and signals for termination. J Intern Med. 2010, 268, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bannenberg, G.; Serhan, C.N. Specialized pro-resolving lipid mediators in the inflammatory response: An update. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010, 1801, 1260–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godson, C.; Guiry, P.; Brennan, E. Lipoxin Mimetics and the Resolution of Inflammation. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2023, 63, 429–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufrusine, B.; Di Francesco, A.; Oddi, S.; Scipioni, L.; Angelucci, C.B.; D'Addario, C.; Serafini, M.; Häfner, A.K.; Steinhilber, D.; Maccarrone, M.; Dainese, E. Iron-dependent trafficking of 5-lipoxygenase and impact on human macrophage activation. Front Immunol. 2019, 10, 1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahnt, A.S.; Häfner, A.K.; Steinhilber, D. The role of human 5-Lipoxygenase (5-LO) in carcinogenesis - a question of canonical and non-canonical functions. Oncogene. 2024, 43, 1319–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Gu, J.; Vandenhoff, G.E.; Liu, X.; Nadler, J.L. Role of 12/15-lipoxygenase in the expression of MCP-1 in mouse macrophages. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008, 294, H1933–1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, N.K.; Rao, G.N. Emerging role of 12/15-Lipoxygenase (ALOX15) in human pathologies. Prog Lipid Res. 2019, 73, 28–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conrad, D.J. The arachidonate 12/15 lipoxygenases. A review of tissue expression and biologic function. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 1999, 17, 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, E.Z.; Jamur, M.C.; Oliver, C. Mast cell function: a new vision of an old cell. J Histochem Cytochem. 2014, 62, 698–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutowska-Owsiak, D.; Selvakumar, T.A.; Salimi, M.; Taylor, S.; Ogg, GS. Histamine enhances keratinocyte-mediated resolution of inflammation by promoting wound healing and response to infection. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2014, 39, 187–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Numata, Y.; Terui, T.; Okuyama, R.; Hirasawa, N.; Sugiura, Y.; Miyoshi, I.; Watanabe, T.; Kuramasu, A.; Tagami, H.; Ohtsu, H. The accelerating effect of histamine on the cutaneous wound-healing process through the action of basic fibroblast growth factor. J Invest Dermatol. 2006, 126, 1403–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levi-Schaffer, F.; Kupietzky, A. Mast cells enhance migration and proliferation of fibroblasts into an in vitro wound. Exp Cell Res. 1990, 188, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishida, K.; Hasegawa, A.; Yamasaki, S.; Uchida, R.; Ohashi, W.; Kurashima, Y.; Kunisawa, J.; Kimura, S.; Iwanaga, T.; Watarai, H.; Hase, K.; Ogura, H.; Nakayama, M.; Kashiwakura, J.I.; Okayama, Y.; Kubo, M.; Ohara, O.; Kiyono, H.; Koseki, H.; Murakami, M.; Hirano, T. Mast cells play role in wound healing through the ZnT2/GPR39/IL-6 axis. Sci Rep. 2019, 9, 10842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulka, M.; Fukuishi, N.; Metcalfe, D.D. Human mast cells synthesize and release angiogenin, a member of the ribonuclease A (RNase A) superfamily. J Leukoc Biol. 2009, 86, 1217–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weller, K.; Foitzik, K.; Paus, R.; Syska, W.; Maurer, M. Mast cells are required for normal healing of skin wounds in mice. FASEB J. 2006, 20, 2366–2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asboe-Hansen, G. Mast cells in health and disease. Bull N Y Acad Med. 1968, 44, 1048–1056. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Trabucchi, E.; Radaelli, E.; Marazzi, M.; Foschi, D.; Musazzi, M.; Veronesi, A.M.; Montorsi, W. The role of mast cells in wound healing. Int J Tissue React. 1988, 10, 367–372. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Serhan, C.N.; Hamberg, M.; Samuelsson, B. Trihydroxytetraenes: a novel series of compounds formed from arachidonic acid in human leukocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1984, 118, 943–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, S. Comprehensive natural products chemistry. Elsevier: London, UK, 1999; pp.255-271.

- Shrhan, C.N. On the relationship between leukotriene and lipoxin production by human neutrophils: evidence for differential metabolism of 15-HETE and 5-HETE. Biophys Acta. 1989, 1004, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brezinski, M.E.; Serhan, C.N. Selective incorporation of (15S)-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid in phosphatidylinositol of human neutrophils: agonist-induced deacylation and transformation of stored hydroxyeicosanoids. Acad Sci USA. 1990, 87, 6248–6252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, M.; Serhan, C.N. Lipoxin generation by permeabilized human platelets. Biochemistry. 1992, 31, 8269–8277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, K.G.; Luna-Gomes, T.; Mesquita-Santos, F.; Corrêa, R.; Assunção, L.S.; Atella, G.C.; Weller, P.F.; Bandeira-Melo, C.; Bozza, P.T. Schistosomal Lipids Activate Human Eosinophils via Toll-Like Receptor 2 and PGD(2) Receptors: 15-LO Role in Cytokine Secretion. Front Immunol. 2019, 9, 3161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, M. Lipoxin and aspirin-triggered lipoxins. Sci. World J. 2010, 10, 1048–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulugeta, S.; Suzuki, T.; Hernandez, N.T.; Griesser, M.; Boeglin, W.E.; Schneider, C. Identification and absolute configuration of dihydroxy-arachidonic acids formed by oxygenation of 5S-HETE by native and aspirin-acetylated COX-2. J Lipid Res. 2010, 51, 575–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serhan, C.N.; Takano, T.; Gronert, K.; Chiang, N.; Clish, C.B. Lipoxin and aspirin-triggered 15-epi-lipoxin cellular interactions anti-inflammatory lipid mediators. Clin Chem Lab Med. 1999, 37, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Wu, L.; Chen, J.; Dong, L.; Chen, C.; Wen, Z.; Hu, J.; Fleming, I.; Wang, D.W. Metabolism pathways of arachidonic acids: mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021, 6, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, K.; Liu, J.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, H.; Huang, C.; Ma, J.; Shen, G.X.; Ye, D.; Huang, B. Microparticles mediate enzyme transfer from platelets to mast cells: a new pathway for lipoxin A4 biosynthesis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010, 400, 432–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szymczak-Pajor, I.; Kleniewska, P.; Wieczfinska, J.; Pawliczak, R. Wide-Range Effects of 1,25(OH)2D3 on Group 4A Phospholipases Is Related to Nuclear Factor κ-B and Phospholipase-A2 Activating Protein Activity in Mast Cells. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2020, 181, 56–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gronert, K.; Gewirtz, A.; Madara, J.L.; Serhan, C.N. Identification of a human enterocyte lipoxin A4 receptor that is regulated by interleukin (IL)-13 and interferon gamma and inhibits tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced IL-8 release. J Exp Med. 1998, 187, 1285–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnamoorthy, S.; Recchiuti, A.; Chiang, N.; Yacoubian, S.; Lee, C.H.; Yang, R.; Petasis, N.A.; Serhan, C.N. Resolvin D1 binds human phagocytes with evidence for proresolving receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010, 107, 1660–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, M.; Godson, C.; Guiry, P.J.; Agerberth, B.; Haeggström, J.Z. Leukotriene B4/antimicrobial peptide LL-37 proinflammatory circuits are mediated by BLT1 and FPR2/ALX and are counterregulated by lipoxin A4 and resolvin E1. FASEB J. 2011, 25, 1697–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krepel, S.A.; Wang, J.M. Chemotactic Ligands that Activate G-Protein-Coupled Formylpeptide Receptors. Int J Mol Sci. 2019, 20, 3426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, P.M.; Ozçelik, T.; Kenney, R.T.; Tiffany, H.L.; McDermott, D.; Francke, U. A structural homologue of the N-formyl peptide receptor. Characterization and chromosome mapping of a peptide chemoattractant receptor family. J Biol Chem. 1992, 267, 7637–7643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badolato, R.; Johnston, J.A.; Wang, J.M.; McVicar, D.; Xu, L.L.; Oppenheim, J.J.; Kelvin, D.J. Serum amyloid A induces calcium mobilization and chemotaxis of human monocytes by activating a pertussis toxin-sensitive signaling pathway. J Immunol. 1995, 155, 4004–4010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuang, Y.; Liu, H.; Edward Zhou, X.; Kumar, Verma, R.; de Waal, P.W.; Jang, W.; Xu, T.H.; Wang, L.; Meng, X.; Zhao, G.; Kang, Y.; Melcher, K.; Fan, H.; Lambert, N.A.; Eric Xu, H.; Zhang, C. Structure of formylpeptide receptor 2-G(i) complex reveals insights into ligand recognition and signaling. Nat Commun. 2020, 11, 885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-García, S.; Jaén, R.I.; Fernández-Velasco, M.; Delgado, C.; Boscá, L.; Prieto, P. Lipoxin-mediated signaling: ALX/FPR2 interaction and beyond. Pharmacol Res. 2023, 197, 106982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migeotte, I.; Communi, D.; Parmentier, M. Formyl peptide receptors: a promiscuous subfamily of G protein-coupled receptors controlling immune responses. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2006, 17, 501–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiore, S.; Maddox, J.F.; Perez, H.D.; Serhan, C.N. Identification of a human cDNA encoding a functional high affinity lipoxin A4 receptor. J Exp Med. 1994, 180, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mun, B.; Obi, P.; Szlenk, C.T.; Natesan, S. Structural basis for the access and binding of resolvin D1 (RvD1) to formyl peptide receptor 2 (FPR2/ALX), a class A GPCR. bioRxiv. 2024, Preprint, 2024.09.23.614540.

- Petri, M.H.; Laguna-Fernández, A.; Gonzalez-Diez, M.; Paulsson-Berne, G.; Hansson, G.K.; Bäck, M. The role of the FPR2/ALX receptor in atherosclerosis development and plaque stability. Cardiovasc Res. 2015, 105, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doens, D.; Fernández, P.L. Microglia receptors and their implications in the response to amyloid beta for Alzheimer's disease pathogenesis. J Neuroinflammation. 2014, 11, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bena, S.; Brancaleone, V.; Wang, J.M.; Perretti, M.; Flower, R.J. Annexin A1 interaction with the FPR2/ALX receptor: identification of distinct domains and downstream associated signaling. J Biol Chem. 2012, 287, 24690–24697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wang, J.; Xia, F.; Wan, J.B.; Lu, J.; Ye, R.D. Dual modulation of formyl peptide receptor 2 by aspirin-triggered lipoxin contributes to its anti-inflammatory activity. FASEB J. 2020, 34, 6920–6933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christophe, T.; Karlsson, A.; Dugave, C.; Rabiet, M.J.; Boulay, F.; Dahlgren, C. The synthetic peptide Trp-Lys-Tyr-Met-Val-Met-NH2 specifically activates neutrophils through FPRL1/lipoxin A4 receptors and is an agonist for the orphan monocyte-expressed chemoattractant receptor FPRL2. J Biol Chem. 2001, 276, 21585–21593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, R.M.; Fattori, V.; Saito, P.; Pinto, I.C.; Rodrigues, C.C.A.; Melo, C.P.B.; Bussmann, A.J.C.; Staurengo-Ferrari, L.; Bezerra, J.R.; Vignoli, J.A.; Baracat, M.M.; Georgetti, S.R.; Verri, W.A. Jr.; Casagrande, R. The Lipoxin Receptor/FPR2 Agonist BML-111 Protects Mouse Skin Against Ultraviolet B Radiation. Molecules. 2020, 25, 2953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stenfeldt, A.L.; Karlsson, J.; Wennerås, C.; Bylund, J.; Fu, H.; Dahlgren, C. Cyclosporin H, Boc-MLF and Boc-FLFLF are antagonists that preferentially inhibit activity triggered through the formyl peptide receptor. Inflammation. 2007, 30, 224–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, H.K.; Gil, C.D.; Oliani, S.M.; Gavins, F.N. Targeting formyl peptide receptor 2 reduces leukocyte-endothelial interactions in a murine model of stroke. FASEB J. 2015, 29, 2161–2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinniah, A.; Yazid, S.; Perretti, M.; Solito, E.; Flower, R.J. The role of the Annexin-A1/FPR2 system in the regulation of mast cell degranulation provoked by compound 48/80 and in the inhibitory action of nedocromil. Int Immunopharmacol. 2016, 32, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, N.; Ruddick, A.; Arthur, G.K.; Wan, H.; Woodman, L.; Brightling, C.E.; Jones, D.J.; Pavord, I.D.; Bradding, P. Primary human airway epithelial cell-dependent inhibition of human lung mast cell degranulation. PLoS One. 2012, 7, e43545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirault, J.; Bäck, M. Lipoxin and Resolvin Receptors Transducing the Resolution of Inflammation in Cardiovascular Disease. Front Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norling, L.V.; Dalli, J.; Flower, R.J.; Serhan, C.N.; Perretti, M. Resolvin D1 limits polymorphonuclear leukocyte recruitment to inflammatory loci: receptor-dependent actions. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012, 32, 1970–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motwani, M.P.; Colas, R.A.; George, M.J.; Flint, J.D.; Dalli, J.; Richard-Loendt, A.; De Maeyer, R.P.; Serhan, C.N.; Gilroy, D.W. Pro-resolving mediators promote resolution in a human skin model of UV-killed Escherichia coli-driven acute inflammation. JCI Insight. 2018, 3, e94463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balta, M.G.; Schreurs, O.; Hansen, T.V.; Tungen, J.E.; Vik, A.; Glaab, E.; Küntziger, T.M.; Schenck, K.; Baekkevold, E.S.; Blix, I.J.S. Expression and function of resolvin RvD1n-3 DPA receptors in oral epithelial cells. Eur J Oral Sci. 2022, 130, e12883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnardottir, H.; Thul, S.; Pawelzik, S.C.; Karadimou, G.; Artiach, G.; Gallina, A.L.; Mysdotter, V.; Carracedo, M.; Tarnawski, L.; Caravaca, A.S.; Baumgartner, R.; Ketelhuth, D.F.; Olofsson, P.S.; Paulsson-Berne, G.; Hansson, G.K.; Bäck, M. The resolvin D1 receptor GPR32 transduces inflammation resolution and atheroprotection. J Clin Invest. 2021, 131, e142883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiang, N.; Barnaeva, E.; Hu, X.; Marugan, J.; Southall, N.; Ferrer, M.; Serhan, C.N. Identification of Chemotype Agonists for Human Resolvin D1 Receptor DRV1 with Pro-Resolving Functions. Cell Chem Biol. 2019, 26, 244–254e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundeen, K.A.; Sun, B.; Karlsson, L.; Fourie, A.M. Leukotriene B4 receptors BLT1 and BLT2: expression and function in human and murine mast cells. J Immunol. 2006, 177, 3439–3447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Min, A.; Lee, Y.A.; Kim, K.A.; El-Benna, J.; Shin, M.H. SNAP23-Dependent Surface Translocation of Leukotriene B4 (LTB4) Receptor 1 Is Essential for NOX2-Mediated Exocytotic Degranulation in Human Mast Cells Induced by Trichomonas vaginalis-Secreted LTB4. Infect Immun. 2016, 85, e00526–16. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nam, Y.H.; Min, D.; Kim, H.P.; Song, K.J.; Kim, K.A.; Lee, Y.A.; Kim, S.H.; Shin, M.H. Leukotriene B4 receptor BLT-mediated phosphorylation of NF-kappaB and CREB is involved in IL-8 production in human mast cells induced by Trichomonas vaginalis-derived secretory products. Microbes Infect. 2011, 14-15, 1211-1220.

- Machado, F.S.; Johndrow, J.E.; Esper, L.; Dias, A.; Bafica, A.; Serhan, C.N.; Aliberti, J. Anti-inflammatory actions of lipoxin A4 and aspirin-triggered lipoxin are SOCS-2 dependent. Nat Med. 2006, 12, 330–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, T.; Izumi, T.; Seyama, Y.; Tadokoro, K.; Rådmark, O.; Samuelsson, B. Characterization of leukotriene A4 synthase from murine mast cells: evidence for its identity to arachidonate 5-lipoxygenase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986, 83, 4175–4179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ro, M.; Lee, A.J.; Kim, J.H. 5-/12-Lipoxygenase-linked cascade contributes to the IL-33-induced synthesis of IL-13 in mast cells, thus promoting asthma development. Allergy. 2018, 73, 350–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulliksson, M.; Brunnström, A.; Johannesson, M.; Backman, L.; Nilsson, G.; Harvima, I.; Dahlén, B.; Kumlin, M.; Claesson, H.E. Expression of 15-lipoxygenase type-1 in human mast cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007, 1771, 1156–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, J.F. 5-Hete. In: Wilson, J.F. (eds) Drugs Eicosanoids. Immunoassay Kit Directory, vol 1 / 3 / 4. Springer, Dordrecht. 1995 pp1768.

- Feltenmark, S.; Gautam, N.; Brunnström, A.; Griffiths, W.; Backman, L.; Edenius, C.; Lindbom, L.; Björkholm, M.; Claesson, H.E. Eoxins are proinflammatory arachidonic acid metabolites produced via the 15-lipoxygenase-1 pathway in human eosinophils and mast cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008, 105, 680–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.J.; Goretzki, A.; Rainer, H.; Zimmermann, J.; Schülke, S. Immune Metabolism in TH2 Responses: New Opportunities to Improve Allergy Treatment - Cell Type-Specific Findings (Part 2). Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2023, 23, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conti, P.; Reale, M.; Barbacane, R.C.; Panara, M.R.; Bongrazio, M.; Theoharides, T.C. Role of lipoxins A4 and B4 in the generation of arachidonic acid metabolites by rat mast cells and their effect on [3H] serotonin release. Immunol Lett. 1992, 32, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baxendell, H.; Haduch, A.; Alwine, J.; Naumov, N.; Falo, L.D.; Sumpter, T.L. Lipoxin A4 restrains mast cell function and inhibits type 2 mediated cutaneous inflammation. J Immunol. 2018, 200 (1_Supplement), 105.4.

- Karra, L.; Haworth, O.; Priluck, R.; Levy, B.D.; Levi-Schaffer, F. Lipoxin B₄ promotes the resolution of allergic inflammation in the upper and lower airways of mice. Mucosal Immunol. 2015, 8, 852–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gastardelo, T.S.; Cunha, B.R.; Raposo, L.S.; Maniglia, J.V.; Cury, P.M.; Lisoni, F.C.; Tajara, E.H.; Oliani, S.M. Inflammation and cancer: role of annexin A1 and FPR2/ALX in proliferation and metastasis in human laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. PLoS One. 2014, 9, e111317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serhan, C.N.; Clish, C.B.; Brannon, J.; Colgan, S.P.; Chiang, N.; Gronert, K. Novel functional sets of lipidderived mediators with anti-inflammatory actions generated from omega-3 fatty acids via cyclooxygenase 2-nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and transcellular processing. J Exp Med. 2000, 192, 1197–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serhan, C.N.; Hong, S.; Gronert, K.; Colgan, S.P.; Devchand, P.R.; Mirick, G.; Moussignac, R.L. Resolvins: a family of bioactive products of omega-3 fatty acid transformation circuits initiated by aspirin treatment that counter proinflammation signals. J Exp Med. 2002, 196, 1025–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serhan, C.N. Pro-resolving lipid mediators are leads for resolution physiology. Nature. 2014, 510, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalli, J.; Chiang, N.; Serhan, C.N. Elucidation of novel 13-series resolvins that increase with atorvastatin and clear infections. Nat Med. 2015, 21, 1071–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filep, J.G. Clearing NETs with T-series resolvins. Blood. 2022, 139, 1128–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, S.F.; Vickery, T.W.; Serhan, C.N. Chiral lipidomics of E-series resolvins: aspirin and the biosynthesis of novel mediators. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011, 1811, 737–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serhan, C.N.; Libreros, S.; Nshimiyimana, R. E-series resolvin metabolome, biosynthesis and critical role of stereochemistry of specialized pro-resolving mediators (SPMs) in inflammation-resolution: Preparing SPMs for long COVID-19, human clinical trials, and targeted precision nutrition. Semin Immunol. 2022, 59, 101597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalli, J.; Serhan, C.N. Identification and structure elucidation of the pro-resolving mediators provides novel leads for resolution pharmacology. Br J Pharmacol. 2019, 76, 1024–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puzzovio, P.G.; Pahima, H.; George, T.; Mankuta, D.; Eliashar, R.; Tiligada, E.; Levy, B.D.; Levi-Schaffer, F. Mast cells contribute to the resolution of allergic inflammation by releasing resolvin D1. Pharmacol Res. 2023, 189, 106691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, N.; de la Rosa, X.; Libreros, S.; Serhan, C.N. Novel Resolvin D2 Receptor Axis in Infectious Inflammation. J Immunol. 2017, 198, 842–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Tonello, R.; Im, S.T.; Jeon, H.; Park, J.; Ford, Z.; Davidson, S.; Kim, Y.H.; Park, C.K.; Berta, T. Resolvin D3 controls mouse and human TRPV1-positive neurons and preclinical progression of psoriasis. Theranostics. 2020, 10, 12111–12126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalli, J.; Winkler, J.W.; Colas, R.A.; Arnardottir, H.; Cheng, C.Y.; Chiang, N.; Petasis, N.A.; Serhan, C.N. Resolvin D3 and aspirin-triggered resolvin D3 are potent immunoresolvents. Chem Biol. 2013, 20, 188–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, N.; Serhan, C.N. Structural elucidation and physiologic functions of specialized pro-resolving mediators and their receptors. Mol Aspects Med. 2017, 58, 114–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flak, M.B.; Koenis, D.S.; Sobrino, A.; Smith, J.; Pistorius, K.; Palmas, F.; Dalli, J. GPR101 mediates the pro-resolving actions of RvD5n-3 DPA in arthritis and infections. J Clin Invest. 2020, 130, 359–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fredman, G.; Ozcan, L.; Spolitu, S.; Hellmann, J.; Spite, M.; Backs, J.; Tabas, I. Resolvin D1 limits 5-lipoxygenase nuclear localization and leukotriene B4 synthesis by inhibiting a calcium-activated kinase pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014, 111, 14530–14535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pope, N.H.; Salmon, M.; Davis, J.P.; Chatterjee, A.; Su, G.; Conte, M.S.; Ailawadi, G.; Upchurch, G.R. Jr. D-series resolvins inhibit murine abdominal aortic aneurysm formation and increase M2 macrophage polarization. FASEB J. 2016, 30, 4192–4201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, M.; Gemperle, C.; Rimann, N.; Hersberger, M. Resolvin D1 Polarizes Primary Human Macrophages toward a Proresolution Phenotype through GPR32. J Immunol. 2016, 196, 3429–3437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulciner, M.L.; Serhan, C.N.; Gilligan, M.M.; Mudge, D.K.; Chang, J.; Gartung, A.; Lehner, K.A.; Bielenberg, D.R.; Schmidt, B.; Dalli, J.; Greene, E.R.; Gus-Brautbar, Y.; Piwowarski, J.; Mammoto, T.; Zurakowski, D.; Perretti, M.; Sukhatme, V.P.; Kaipainen, A.; Kieran, M.W.; Huang, S.; Panigrahy, D. Resolvins suppress tumor growth and enhance cancer therapy. J Exp Med. 2018, 215, 115–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botten, N.; Hodges, R.R.; Li, D.; Bair, J.A.; Shatos, M.A.; Utheim, T.P.; Serhan, C.N.; Dartt, D.A. Resolvin D2 elevates cAMP to increase intracellular [Ca2+] and stimulate secretion from conjunctival goblet cells. FASEB J. 2019, 33, 8468–8478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnouri, M.W.; Roquid, K.A.; Bonnavion, R.; Cho, H.; Heering, J.; Kwon, J.; Jäger, Y.; Wang, S.; Günther, S.; Wettschureck, N.; Geisslinger, G.; Gurke, R.; Müller, C.E.; Proschak, E.; Offermanns, S. SPMs exert anti-inflammatory and pro-resolving effects through positive allosteric modulation of the prostaglandin EP4 receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2024, 121, e2407130121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardoso, R.D.R.; Chambo, S.D.; Zaninelli, T.H.; Bianchini, B.H.S.; Silva, M.D.V.D.; Bertozzi, M.M.; Saraiva-Santos, T.; Franciosi, A.; Martelossi-Cebinelli, G.; Garcia-Miguel, P.E.; Borghi, S.M.; Casagrande, R.; Verri, W.A. Resolvin D5 (RvD5) Reduces Renal Damage Caused by LPS Endotoxemia in Female Mice. Molecules. 2022, 28, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouhadoun, A.; Manikpurage, H.D.; Deschildre, C.; Zalghout, S.; Dubourdeau, M.; Urbach, V.; Ho-Tin-Noe, B.; Deschamps, L.; Michel, J.B.; Longrois, D.; Norel, X. DHA, RvD1, RvD5, and MaR1 reduce human coronary arteries contractions induced by PGE(2). Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2023, 165, 106700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiurchiù, V.; Leuti, A.; Dalli, J.; Jacobsson, A.; Battistini, L.; Maccarrone, M.; Serhan, C.N. Proresolving lipid mediators resolvin D1, resolvin D2, and maresin 1 are critical in modulating T cell responses. Sci Transl Med. 2016, 8, 353ra111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connor, K.M.; SanGiovanni, J.P.; Lofqvist, C.; Aderman, C.M.; Chen, J.; Higuchi, A.; Hong, S.; Pravda, E.A.; Majchrzak, S.; Carper, D.; Hellstrom, A.; Kang, J.X.; Chew, E.Y.; Salem, N. Jr.; Serhan, C.N.; Smith, L.E.H. Increased dietary intake of omega-3-polyunsaturated fatty acids reduces pathological retinal angiogenesis. Nat Med. 2007, 13, 868–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Recchiuti, A.; Krishnamoorthy, S.; Fredman, G.; Chiang, N.; Serhan, C.N. MicroRNAs in resolution of acute inflammation: identification of novel resolvin D1-miRNA circuits. FASEB J. 2011, 25, 544–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.Z.; Zhang, L.; Liu, T.; Park, J.Y.; Berta, T.; Yang, R.; Serhan, C.N.; Ji, R.R. Resolvins RvE1 and RvD1 attenuate inflammatory pain via central and peripheral actions. Nat Med. 2010, 16, 592–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohira, T.; Arita, M.; Omori, K.; Recchiuti, A.; Van Dyke, T.E.; Serhan, C.N. Resolvin E1 receptor activation signals phosphorylation and phagocytosis. J Biol Chem. 2010, 285, 3451–3461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymańska, P.; Luzak, B.; Miłowska, K.; Golański, J. The Anti-Aggregative Potential of Resolvin E1 on Human Platelets. Molecules. 2023, 28, 5323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herová, M.; Schmid, M.; Gemperle, C.; Hersberger, M. ChemR23, the receptor for chemerin and resolvin E1, is expressed and functional on M1 but not on M2 macrophages. J Immunol. 2015, 194, 2330–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiang, N.; Sakuma, M.; Rodriguez, A.R.; Spur, B.W.; Irimia, D.; Serhan, C.N. Resolvin T-series reduce neutrophil extracellular traps. Blood. 2022, 139, 1222–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, C.P.B.; Saito, P.; Martinez, R.M.; Staurengo-Ferrari, L.; Pinto, I.C.; Rodrigues, C.C.A.; Badaro-Garcia, S.; Vignoli, J.A.; Baracat, M.M.; Bussmann, A.J.C.; Georgetti, S.R.; Verri, W.A.; Casagrande, R. Aspirin-Triggered Resolvin D1 (AT-RvD1) Protects Mouse Skin against UVB-Induced Inflammation and Oxidative Stress. Molecules. 2023, 28, 2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldan, J.T.; Jansen, C.; Speck, M.; Maaetoft-Udsen, K.; Cordasco, E.A.; Faiai, M.; Shimoda, L.M.N.; Greineisen, W.E.; Turner, H.; Stokes, A.J. Insulin-induced lipid body accumulation is accompanied by lipid remodelling in model mast cells. Adipocyte. 2019, 8, 265–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.; Ding, S.; Liu, S.; Li, X.; Tang, X.; Sun, L. Resolvin D1 Improves the Treg/Th17 Imbalance in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Through miR-30e-5p. Front Immunol. 2021, 12, 668760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piersigilli, F.; Bhandari, V. Biomarkers in neonatology: the new "omics" of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016, 29, 1758–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agier, J.; Brzezińska-Błaszczyk, E.; Żelechowska, P.; Wiktorska, M.; Pietrzak, J.; Różalska, S. Cathelicidin LL-37 Affects Surface and Intracellular Toll-Like Receptor Expression in Tissue Mast Cells. J Immunol Res. 2018, 2018, 7357162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee, P.K.; Marcheselli, V.L.; Serhan, C.N.; Bazan, N.G. Neuroprotectin D1: a docosahexaenoic acid-derived docosatriene protects human retinal pigment epithelial cells from oxidative stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004, 101, 8491–8496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Périz, A.; Planagumà, A.; Gronert, K.; Miquel, R.; López-Parra, M.; Titos, E.; Horrillo, R.; Ferré, N.; Deulofeu, R.; Arroyo, V.; Rodés, J.; Clària, J. Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) blunts liver injury by conversion to protective lipid mediators: protectin D1 and 17S-hydroxy-DHA. FASEB J. 2006, 20, 2537–2539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariel, A.; Li, P.L.; Wang, W.; Tang, W.X.; Fredman, G.; Hong, S.; Gotlinger, K.H.; Serhan, C.N. The docosatriene protectin D1 is produced by TH2 skewing and promotes human T cell apoptosis via lipid raft clustering. J Biol Chem. 2005, 280, 43079–43086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serhan, C.N.; Gotlinger, K.; Hong, S.; Lu, Y.; Siegelman, J.; Baer, T.; Yang, R.; Colgan, S.P.; Petasis, N.A. Anti-inflammatory actions of neuroprotectin D1/protectin D1 and its natural stereoisomers: assignments of dihydroxy-containing docosatrienes. J Immunol. 2006, 176, 1848–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcheselli, V.L.; Hong, S.; Lukiw, W.J.; Tian, X.H.; Gronert, K.; Musto, A.; Hardy, M.; Gimenez, J.M.; Chiang, N.; Serhan, C.N.; Bazan, N.G. Novel docosanoids inhibit brain ischemia-reperfusion-mediated leukocyte infiltration and pro-inflammatory gene expression. J Biol Chem. 2003, 278, 43807–43817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, A.R.; Spur, B.W. First total synthesis of the pro-resolving lipid mediator 7(S),12(R),13(S)-Resolvin T2 and its 13(R)-epimer. Tetrahedron Lett. 2020, 61, 151857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serhan, C.N.; Fredman, G.; Yang, R.; Karamnov, S.; Belayev, L.S.; Bazan, N.G.; Zhu, M.; Winkler, J.W.; Petasis, N.A. Novel proresolving aspirin-triggered DHA pathway. Chem Biol. 2011, 18, 976–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serhan, C.N.; Yang, R.; Martinod, K.; Kasuga, K.; Pillai, P.S.; Porter, T.F.; Oh, S.F.; Spite, M. Maresins: novel macrophage mediators with potent antiinflammatory and proresolving actions. J Exp Med. 2009, 206, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, B.; Wang, C.W.; Arnardottir, H.H.; Li, Y.; Cheng, C.Y.; Dalli, J.; Serhan, C.N. Maresin biosynthesis and identification of maresin 2, a new anti-inflammatory and pro-resolving mediator from human macrophages. PLoS One. 2014, 9, e102362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isobe, Y.; Kato, T.; Arita, M. Emerging roles of eosinophils and eosinophil-derived lipid mediators in the resolution of inflammation. Front Immunol. 2012, 3, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serhan, C.N.; Dalli, J.; Karamnov, S.; Choi, A.; Park, C.K.; Xu, Z.Z.; Ji, R.R.; Zhu, M.; Petasis, N.A. Macrophage proresolving mediator maresin 1 stimulates tissue regeneration and controls pain. FASEB J. 2012, 26, 1755–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalli, J.; Zhu, M.; Vlasenko, N.A.; Deng, B.; Haeggström, J.Z.; Petasis, N.A.; Serhan, C.N. The novel 13S,14S-epoxy-maresin is converted by human macrophages to maresin 1 (MaR1), inhibits leukotriene A4 hydrolase (LTA4H), and shifts macrophage phenotype. FASEB J. 2013, 27, 2573–2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cezar, T.L.C.; Martinez, R.M.; Rocha, C.D.; Melo, C.P.B.; Vale, D.L.; Borghi, S.M.; Fattori, V.; Vignoli, J.A.; Camilios-Neto, D.; Baracat, M.M.; Georgetti, S.R.; Verri, W.A. Jr.; Casagrande, R. Treatment with maresin 1, a docosahexaenoic acid-derived pro-resolution lipid, protects skin from inflammation and oxidative stress caused by UVB irradiation. Sci Rep. 2019, 9, 3062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, S.; Xie, Y.K.; Zhang, Z.J.; Wang, Z.; Xu, Z.Z.; Ji, R.R. GPR37 regulates macrophage phagocytosis and resolution of inflammatory pain. J Clin Invest. 2018, 128, 3568–3582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.H.; Shin, K.O.; Kim, J.Y.; Khadka, D.B.; Kim, H.J.; Lee, Y.M.; Cho, W.J.; Cha, J.Y.; Lee, B.J.; Lee, M.O. A maresin 1/RORalpha/12-lipoxygenase autoregulatory circuit prevents inflammation and progression of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. J Clin Invest. 2019, 129, 1684–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.H.; Kim, H.J.; Na, H.; Nam, M.W.; Kim, J.Y.; Kim, J.S.; Koo, S.H.; Lee, M.O. RORα Induces KLF4-Mediated M2 Polarization in the Liver Macrophages that Protect against Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Cell Rep. 2017, 20, 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, X.; Hao, Y.; Wu, C.; Fu, Y.; Su, N.; Chen, H.; Ying, B.; Wang, H.; Su, L.; Cai, H.; He, Q.; Cai, M.; Sun, J.; Lin, J.; Scott, A.; Smith, F.; Huang, X.; Jin, S. Maresin 1 intervention reverses experimental pulmonary arterial hypertension in mice. Br J Pharmacol. 2022, 179, 5132–5147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiang, N.; Libreros, S.; Norris, P.C.; de la Rosa, X.; Serhan, C.N. Maresin 1 activates LGR6 receptor promoting phagocyte immunoresolvent functions. J Clin Invest. 2019, 129, 5294–5311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamoorthy, N.; Walker, K.H.; Brüggemann, T.R.; Tavares, L.P.; Smith, E.W.; Nijmeh, J.; Bai, Y.; Ai, X.; Cagnina, R.E.; Duvall, M.G.; Lehoczky, J.A.; Levy, B.D. The Maresin 1-LGR6 axis decreases respiratory syncytial virus-induced lung inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2023, 120, e2206480120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baccari, G.C.; Pinelli, C.; Santillo, A.; Minucci, S.; Rastogi, R.K. Mast cells in nonmammalian vertebrates: an overview. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2011, 290, 1–53. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, J.J.; Morales, J.K.; Falanga, Y.T.; Fernando, J.F.; Macey, M.R. Mast cell regulation of the immune response. World Allergy Organ J. 2009, 2, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).