Submitted:

15 January 2025

Posted:

16 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- What are the main e-tendering implementation barriers identified in the existing literature in the construction industry?

- How can the main barriers identified be grouped based on geographical locations or regions?

- Which electronic tendering barriers are common across all the geographical regions?

- What are the 10 crucial electronic tendering barriers that affect the tendering process in the construction industry?

- How can the organizations overcome the identified barriers

2. Literature Review

2.1. The barriers to electronic tendering implementation

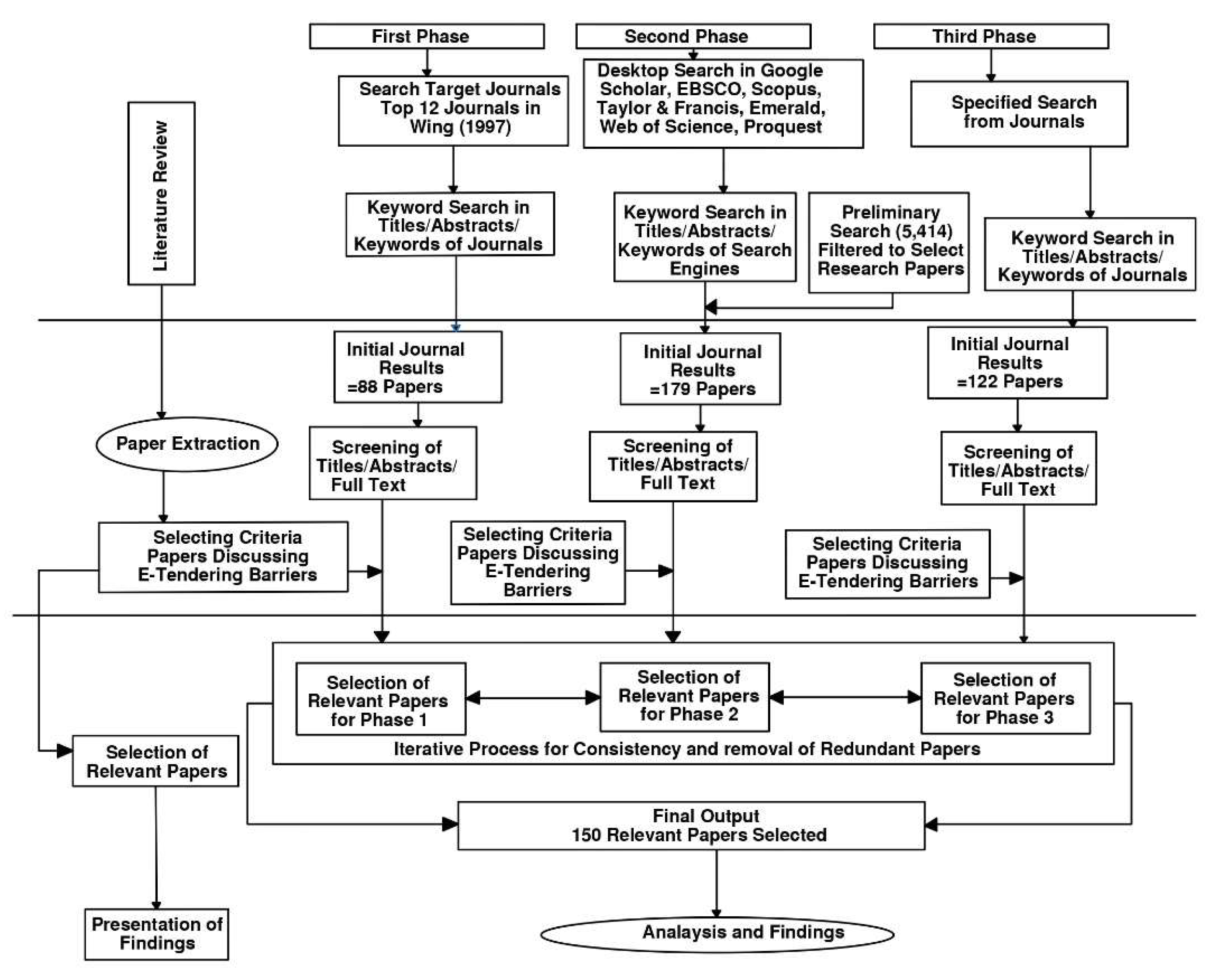

3. Research Methodology

3.1. First phase - searching for target journals

- "Electronic procurement" OR "E-procurement": These keywords encompass the concept of digital or electronic processes for procurement. Including both variations ensures that the search captures articles using either term.

- "Electronic Tendering" OR "E-Tendering": These terms represent the concept of electronic tendering processes in construction projects. Including both variations ensures that articles using either term are included in the search results.

- "Barriers" OR "Challenges": These keywords specify the focus of the research—identifying barriers or challenges related to electronic procurement and tendering. These terms indicate that the search is looking for articles discussing obstacles or difficulties faced in implementing these digital processes.

- "Construction Industry": This keyword defines the context within which the electronic procurement and tendering processes are being studied. It ensures that the search results are relevant to the construction sector.

- Significant technological changes: The chosen timeframe encapsulates a period during which there were notable advancements in technology and digital transformation. This timeframe covers a decade where the construction industry witnessed significant changes in the adoption and integration of digital tools.

- Critical period of adoption: The years between 2010 and 2024 marked a critical period for the adoption of e-tendering practices. Many industries, including construction, were transitioning from traditional methods to digital platforms during this timeframe.

- Timeliness: By focusing on more recent years, the study could provide insights that are relevant to current industry challenges and trends, making the findings more applicable and actionable.

3.2. Second phase - desktop search

3.3. Third phase: the specific journal search

3.4. Trend in publications

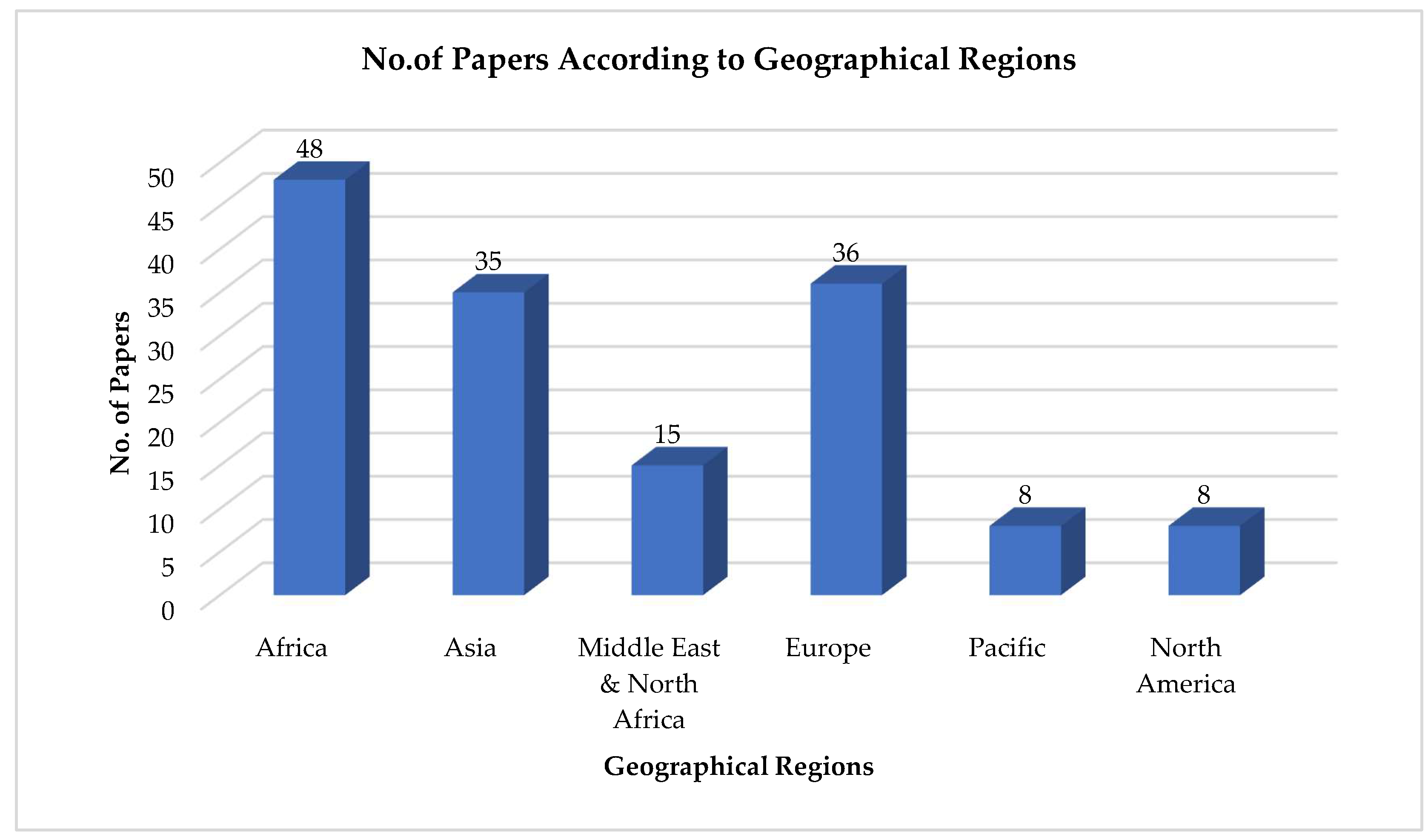

3.5. Publication by geographical regions

3.6. Identified barriers to e-tendering implementation by geographical regions

3.6.1. Critical Barriers to e-tendering in Africa

| No. | E-tendering barriers | Author |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Inadequate data security/ cyber security risk | [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 36, 37,38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 45, 46, 47] |

| 2 | Inadequate ICT and internet infrastructure (Poor internet, High-speed expensive internet services, difficulties in transitioning from paper-based to electronic systems) | [1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 11, 10, 12, 13, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 24, 25, 28, 29, 30, 31, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 48] |

| 3 | Lack of uniform standard or policy and Inadequate legal framework | [1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 9, 8, 10, 11, 12, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 32, 33, 37, 38, 40, 42, 43, 44, 45] |

| 4 | Inadequate technical /ICT skilled personnel (lack of professional training, lack of adequate knowledge and skills, Unavailability of e-procurement experts) | [1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 11, 13, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 22, 25, 27, 28, 29, 30, 32, 33, 34, 35, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 47, 48,] |

| 5 | Reluctance/ resistance to change | [1, 2, 7, 9, 10, 11, 13, 14, 16, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 27, 29, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 45, 48] |

| 6 | High investment cost of implementation/High technology cost | [1, 5, 7, 9, 11,10, 14, 17, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 37, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 45] |

| 7 | Lack of Support/Lack of Management Support | [1, 2, 3, 5, 11, 13, 15, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 25, 27, 31, 34, 37, 39, 40, 41, 43, 44, 45, 48] |

| 8 | Lack of general awareness of benefits/information of e-procurement systems/ Low levels of awareness and knowledge about e-procurement technology. | [7, 11, 12, 14, 15, 17, 24, 27, 28, 29, 31, 32, 37, 38, 39, 40, 42, 43, 44, 45] |

| 9 | Software non-compatibility /interoperability issues | [5, 7, 15, 21, 22, 25, 27, 28, 29, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 43, 47] |

| 10 | Unreliable electric power supply | [1, 5, 11,15,17,23, 25, 28,29, 39, 40, 41, 43] |

| 11 | Technical malfunctioning of the portal | [1, 2, 9, 11, 12, 15, 17, 23, 30, 37, 43] |

| 12 | The complexity and user-unfriendliness/complex interface | [38, 40, 42, 43, 46] |

| 13 | Lack of monitoring of supplier’s compliance/lack of performance evaluation | [39, 41, 43] |

| 14 | Unethical Practices (transparency issues) | [42, 43, 44] |

| 15 | Fear of loss of jobs | [47] |

3.6.2. Critical barriers to e-tendering in Asia

3.6.3. Critical Barriers to e-tendering from the Middle East and North Africa

3.6.4. Critical Barriers to e-tendering in Europe

3.6.5. Critical barriers to e-tendering in the Pacific

3.6.6. Critical barriers to e-tendering from North America

4. Findings and Discussions

4.1. Comparison of the main barriers to e-tendering based on geographical regions.

4.2. The main barriers to e-tendering across all geographical regions.

Top 10 barriers across all regions with the most frequent occurrences

- The top ten barriers were selected based on their high frequency of occurrence across different regions, indicating that these challenges are widespread and significantly affect electronic tendering adoption globally.

- Impact on electronic tendering implementation

- Focusing on the top ten barriers allows for a more in-depth discussion and recommendation of feasible solutions and strategies to overcome these challenges.

- Regional Relevance

- Limiting the discussion to ten barriers helps maintain clarity and focus and provides a clear and concise discussion that is easier for stakeholders to understand and act upon.

- Prioritization of Resources: In most cases, organizations often have limited resources to address challenges, hence, discussing the top ten barriers, can help prioritize the allocation of resources to the most pressing issues.

Inadequate data security/cyber security issues:

Resistance to change

Inadequate legal framework or lack of uniform standards or policies.

Inadequate technical / ICT skilled personnel

Inadequate ICT and Internet infrastructure in the organization to facilitate e-tendering

High investment cost of implementation

Lack of support

Lack of trust and awareness of benefits of e-procurement systems

Software non-compatibility / interoperability challenges

Portal technical malfunction and technical issues

4.3. Solutions to the Barriers and Best Practices For E-tendering and The Future of E-tendering

- Improving ICT Infrastructure: E-tendering relies heavily on reliable ICT infrastructure. As a result, numerous governments and organizations must invest in the development of ICT infrastructure, particularly in underserved areas, in order to ensure reliable and widespread Internet access.

- Improved Cybersecurity: Implementing sophisticated features like encryption, multi-factor authentication, and regular security audits helps safeguard E-tendering systems from cyber threats.

- Training Program Organizations: Institutional training programs can increase acceptance rates of E-tendering systems. This can be done by providing stakeholders with workshops and training programs that improve technical proficiency and understanding of e-tendering processes.

- Standardized Protocols Development: The establishment of well-standardized standards and regulations for e-tendering can help to streamline operations, eliminate confusion, and increase efficiency. It can be achieved through collaboration among governments, industry entities, and international organizations.

- Promotion of Inclusivity: Implementing inclusive policies and practices, including accessible platform designs and focused outreach initiatives, can guarantee that excluded groups possess equal opportunities to engage in e-tendering.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

5.1. Implication of the study

5.2. Contribution to the body of knowledge

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdullahi, A. (2023). Electronic-Procurement Implementation Model for Public Sector Construction Projects in Abuja, Doctoral dissertation, Abuja, Nigeria.

- Abdullahi, B.; Ibrahim, Y.M.; Ibrahim, A.; Bala, K. Development of e-tendering evaluation system for Nigerian public sector. Journal of Engineering, Design and Technology 2020, 18, 122–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-ELSamen, A.; Chakraborty, G.; Warren, D. A process-based analysis of e-procurement adoption. Journal of Internet Commerce 2010, 9, 243–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addo, S.K. Challenges of E-Procurement Adoption in the Ghana Public Sector: A Survey of in the Ministry of Finance. Scholarly Journal of Arts & Humanities 2019, 1, 44–80. [Google Scholar]

- Adebayo, V. O. and Evans, R. D. (2015). Adoption of e-procurement systems in developing countries: A Nigerian public sector perspective. In 2015 2nd International Conference on Knowledge-Based Engineering and Innovation (KBEI), IEEE, November 5-6, 2015, Tehran, Iran. pp. 20–25.

- Aduwo, E.B.; Ibem, E.O.; Uwakonye, O.; Tunji-Olayeni, P.F.; Ayo-Vaughan, K. Barriers to the uptake of e-procurement in the Nigerian building industry. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Information Technology 2016, 89, 133–147. [Google Scholar]

- Aghimien, D.; Aigbavboa, C.; Oke, A.; Thwala, W.; Moripe, P. Digitalization of construction organizations–a case for digital partnering. Musa 2020, 22, 1950–1959. [Google Scholar]

- Aguiar Costa, A. and Grilo, A. BIM-based e-procurement: An innovative approach to construction e-procurement. The Scientific World Journal, 2015(4):1-15. [CrossRef]

- Aguila, Juan-Carlos, "E-Procurement Challenges & Supplier Enablement in California Counties" 2020. Master's Projects. 961. San Jose State University, California, USA. [CrossRef]

- Ahimbisibwe, A.; Wilson, T.; Ronald, T. Adoption of E-procurement technology in Uganda: Migration from the manual public procurement systems to the Internet. Journal of Supply Chain Management 2018, 3, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, T., Aljafari, R., and Venkatesh, V. 2019. The government of Jamaica’s electronic procurement system: experiences and lessons learned. Internet Research, 29(6), 1571-1588. [CrossRef]

- Aibinu, A., and Al-Lawati, A. 2010. Using the PLS-SEM technique to model construction organizations' willingness to participate in e-bidding. Automation in Construction, 19, 714-724. [CrossRef]

- Al Hazza, M. H., Muqtadar, M., El Salamony, K., Bourini, I. F., Sakhrieh, A., and Alnahhal, M. 2023. Investigation study of the challenges in green procurement implementation in construction projects in UAE. Civil Engineering Journal, 9(4), 849-859. [CrossRef]

- Ali, R.F.; Memon, N.A.; Pathan, A.A. Beyond Traditional Practices: Investigating Cutting-Edge E-Procurement Initiatives for Contractor Selection in Punjab Pakistan Construction Industry–A Case Study of Public Sector Clients. Tropical Scientific Journal 2023, 2, 79–94. [Google Scholar]

- Alkalbani, S., Rezgui, Y., Vorakulpipat, C. and Wilson, I. E. 2013. ICT adoption and diffusion in the construction industry of a developing economy: The case of the sultanate of Oman. Architectural Engineering and Design Management, Vol. 9, 62-75. [CrossRef]

- Allal-Chérif, O., and Babai, M. Z. 2012. Do Electronic Marketplaces Improve Procurement Performance? In Supply Chain Forum: An International Journal (Vol. 13, No. 3, pp. 40–54). Taylor & Francis. [CrossRef]

- Alsaç, U. 2017. EKAP: Turkey's Centralized E-Procurement System. In Digital Governance and E-Government Principles Applied to Public Procurement. IGI Global, pp. 126–150. [CrossRef]

- Altayyar, A. and Beaumont-Kerridge, J. An investigation into barriers to the adoption of e-procurement within selected SMEs in Saudi Arabia. Journal of Business and Economics 2016, 7, 451–66. [Google Scholar]

- Altayyar, A. and Beaumont-Kerridge, J. (2016a). External factors affecting the adoption of e-procurement in Saudi Arabian SMEs. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 229, pp. 363–375. [CrossRef]

- Al-Yahya, M. and Panuwatwanich, K. Implementing e-tendering to improve the efficiency of public construction contracts in Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Procurement Management 2018, 11, 267–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Yahya, M. , Skitmore, M., Bridge, A., Nepal, M. P., and Cattell, D. E-tendering readiness in construction: an a priori model. International journal of procurement management 2018, 11, 608–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amalia, F. 2016. Socio-Technical Analysis of Indonesian Government E-Procurement System Implementation. The Indonesian Journal of Accounting Research, 19(1), PP 22-50. [CrossRef]

- Aman, A., and Kasimin, H. 2011. E-procurement implementation: a case of Malaysia government. Transforming Government: People, Process and Policy, 5(4), 330-344. [CrossRef]

- Amuda-Yusuf, G.; Gbadamosi, S.; Adebiyi, R.T.; Rasheed, A.S.; Idris, S.; Eluwa, S.E. Barriers to Electronic Tendering Adoption by Organisations in Nigerian Construction Industry. Environmental Technology & Science Journal 2019, 10, 46–55. [Google Scholar]

- Anumba, C.J.; Ruikar, K. Electronic commerce in construction—trends and prospects. Automation in construction 2002, 11, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, G. , Tuncan, M., Birgonul, M. T., and Dikmen, I. E-bidding proposal preparation system for construction projects. Building and Environment 2006, 41, 1406–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azanlerigu, J.A.; Akay, E. Prospects and challenges of e-procurement in some selected public institutions in Ghana. European Journal of Business and Management 2015, 7, 61–76. [Google Scholar]

- Aziz, N. M. 2024. Towards Digital Future: Unlocking Strategies to Integrate E-Tendering in The Construction Landscape. Planning Malaysia, 22(32). [CrossRef]

- Badi, S., Ochieng, E., Nasaj, M., and Papadaki, M. 2021. Technological, organizational and environmental determinants of smart contracts adoption: UK construction sector viewpoint. Construction Management and Economics, 39(1), 36-54. [CrossRef]

- Bahreman, B. 2014. E-procurement in Iran cement industry limitations and benefits. In 2014 11th International Conference on Information Technology: New Generations (pp. 581–586). IEEE. 7-9 April 2014, Las Vegas, NV, USA. [CrossRef]

- Bala, K., and Dahiru, A. 2013. Identification of barriers and enablers of e-procurement processes in PPP projects delivery in Nigeria. PPP International Conference 2013 Body of Knowledge. University of Central Lancashire (UCLAN) Preston, UK 18–20 March 2013, pp. 423 -432.

- Baladhandayutham; Venkatesh, S. e-Procurement-An Empirical Study on Construction Projects Supply Chain Kuwait. International Journal of Management 2012, 3, 82–100. [Google Scholar]

- Baladhandayutham, T. and Shanthi Venkatesh. (2012a). Construction Industry in Kuwait – An Analysis of E-Procurement Adoption concerning Supplier’s Perspective. International Journal of Management Research and Development (IJMRD), 2(1), SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3540671.

- Beauvallet, G., Boughzala, Y. and Assar, S. 2011. E-procurement, from project to practice: Empirical evidence from the French public sector. In Practical studies in e-government, Springer, New York, NY, pp. 13–27. [CrossRef]

- Belisari, S., Binci, D. and Appolloni, A. 2020. E-procurement adoption: A case study about the role of two Italian advisory services. Sustainability, Vol. 12, pp. 7476. [CrossRef]

- Bello, W.A.; Iyagba, R.O. Comparative Analysis of Barriers to E-procurement among Quantity Surveyors in UK and Nigeria. Scottish Journal of Arts, Social Sciences and Scientific Studies 2013, 14, 175–187. [Google Scholar]

- Benzidia, S. 2013. E-Design: Toward a new collaborative exchange of upstream e-supply chain. In Supply Chain Forum: An International Journal (Vol. 14, No. 4, pp. 4–9). [CrossRef]

- Betts, M. , Black, P., Christensen, S., Dawson, E., Du, R., Duncan, B. and Gonzalez Nieto, J. Towards secure and legal e-tendering. Journal of Information Technology in Construction 2006, 11, 89–102. [Google Scholar]

- Boughzala, Y., Bouzid, I., and Boughzala, I. 2012. Factors of public e-procurement adoption: An Exploratory Field study with French practitioners. In Supply Chain Forum: An International Journal (Vol. 13, No. 3, pp. 56–68). [CrossRef]

- Bowmaster, J., Rankin, J. and Perera, S. 2016. E-business in the architecture, engineering, and construction (AEC) industry in Canada: An Atlantic Canada study.CIB TG83: e-Business in Construction, pp. 1–32. [CrossRef]

- Bromberg, D., & Manoharan, A. 2015. E-procurement implementation in the United States: Understanding progress in local government. Public Administration Quarterly, 39(3), pp. 360–392. [CrossRef]

- Bubala, C., & Lesa, C. 2024. Examining E-Government Procurement System Adoption by Procuring Entities in Zambia. International Journal of Engineering and Management Research, 14(2), 40-53. [CrossRef]

- Bulut, C., & Yen, B. P. 2013. E-procurement in the public sector: a global overview. Electronic Government, an International Journal, 10(2), 189-210. [CrossRef]

- Chan, A. P. and Owusu, E. K. 2022. Evolution of Electronic Procurement: Contemporary Review of Adoption and Implementation Strategies. Buildings, Vol. 12, pp. 198. [CrossRef]

- Changsen, Z. 2012. The study on the enterprises' E-Procurement in China. In 2012 3rd International Conference on System Science, Engineering Design and Manufacturing Informatization (Vol. 1, pp. 233–236). IEEE. 20-21 Oct. 2012. Chengdu, China. [CrossRef]

- Cherian, T. M., and Kumaran, L. A. 2016. E-business in the construction industry: Opportunities and challenges. Indian Journal of Science and Technology, Vol. 9, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Chien, H.J.; Barthorpe, S. Current Usage Of E-Business in The Taiwanese Construction Industry. International journal of engineering technology and scientific innovation 2010, 1, 69–76. [Google Scholar]

- Chilipunde, R.L. Electronic tendering in the Malawian construction industry: the dilemmas and benefits. Journal of Modern Education Review 2013, 3, 791–800. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, A. A., Arantes, A. and Tavares, L. V. 2013. Evidence of the impacts of public e-procurement: The Portuguese experience. Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management, Vol. 19, pp. 238–246. [CrossRef]

- AbdulAzeez A.D., Badiru, Y. Y., and Gabriel, B. B. 2015. A survey of public construction management agencies readiness for E-procurement adoption. Jurnal Teknologi, Vol .77, pp. 85–92. [CrossRef]

- Deraman, R.; Salleh, H.; Rahim, F.A. Implementing e-Purchasing in construction organizations: an exploratory study to identify organizational critical success factors. International Journal of Business and Management Studies 2012, 4, 209–225. [Google Scholar]

- Dlakuseni, S.; Kanyepe, J.; Tukuta, M. Working towards a Framework for Enhancing Public E-Procurement for Zimbabwe State Owned Enterprises (SOEs). International Journal of Supply Chain Management (IJSCM) 2018, 7, 339–348. [Google Scholar]

- Doherty, N. F., McConnell, D. and Ellis-Chadwick, F. 2013. Institutional responses to electronic procurement in the public sector. International Journal of Public Sector Management, Vol. 26, pp. 495–515. [CrossRef]

- Du, R., Foo, E., Nieto, J. G., & Boyd, C. 2005. Designing secure e-tendering systems. In International Conference on Trust, Privacy and Security in Digital Business, Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, Germany, Vol. 3592, 70-79. [CrossRef]

- Eadie, R. and Perera, S. C. 2016. The state of construction e-business in the UK. Construct I.T. For Business, Manchester, pp. 1–25. [CrossRef]

- Eadie, R.; Perera, S.; Heaney, G. A cross-discipline comparison of rankings for e-procurement drivers and barriers within UK construction organizations. Journal of Information Technology in Construction 2010, 15, 217–233. [Google Scholar]

- Eadie, R., Perera, S. and Heaney, G. (2010a). Identification of key process areas in the production of an e-capability maturity model for UK construction organizations. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Innovation in Architecture, Engineering and Construction (AEC), June 9-11, 2010, The Nittany Lion, Pennsylvania State University, USA. [CrossRef]

- Eadie, R.; Perera, S.; Heaney, G. Identification of e-procurement drivers and barriers for UK construction organizations and ranking of these from the perspective of quantity surveyors. Journal of Information Technology in Construction 2010, 23–43. [Google Scholar]

- Eadie, R., Perera, S., and Heaney, G. 2011. Key process area mapping in the production of an e-capability maturity model for UK construction organizations. Journal of Financial Management of Property and Construction, 16, 197-210. [CrossRef]

- Elsanosi, A. 2020. Impact of e-procurement in the construction industry SMEs of Ireland. Doctoral dissertation, Dublin Business School, Dublin Ireland.

- Fernandes, T. and Vieira, V. 2015. Public e-procurement impacts in small and medium enterprises. International Journal of Procurement Management, Vol. 8, pp. 587–607. [CrossRef]

- Gajendran, T. , and Perera, S. 2017. The Australian Construction e-Business Review. report published by CIB TG83: e-Business in Construction, University of Newcastle, Western Sydney University, and the Australian Institute of Building (AIB). [CrossRef]

- Gambo, M. M., Dodo, M., and Yusuf, H. 2019. Assessment of stakeholders’ perception of risk factors associated with the adoption of e-procurement in the Nigerian construction industry. In West Africa Built Environment Research (WABER) Conference Proceedings, Accra, Ghana, pp. 188–199. [CrossRef]

- Gardena, F. 2013. A model to measure e-procurement impacts on organizational performance. Journal of Public Procurement, 13(2), 215-242. [CrossRef]

- Gascó, M., Cucciniello, M., Nasi, G., and Yuan, Q. 2018. Determinants and barriers of e-procurement: A European comparison of public sector experiences. Proceedings of the 51st Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, 1-10. Hilton Waikoloa Village, Hawaii, January 3 - 6, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Gholampur, S. 2018. E-procurement adoption impacts on organizations “Performance and maturity”: An exploratory case study (Order No. 28214637). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (2489854414). Retrieved from https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/e-procurement-adoption-impacts-on-organisations/docview/2489854414/se-2?accountid=15340.

- Gihozo, D. 2020. Adoption of e-procurement in Rwandan Public institutions (Publication Number 4FE25E) Linnaeus University, Växjö Campus].

- Gong, T., Tao, X., Das, M., Liua, Y., and Chenga, J. 2022. Blockchain-based e-tendering evaluation framework. International Journal of Automation & Digital Transformation, 1(1), 75-93. [CrossRef]

- Goswami, Y., Agrawal, A. and Bhatia, A. 2020. E-Governance: A Tendering Framework Using Blockchain with Active Participation of Citizens. In 2020 IEEE International Conference on Advanced Networks and Telecommunications Systems (ANTS), New Delhi, India, pp. 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Grilo, A., and Jardim-Goncalves, R. 2011. Challenging electronic procurement in the AEC sector: A BIM-based integrated perspective. Automation in Construction, 20(2), 107-114. [CrossRef]

- Gunasekaran, A., and Ngai, E. W. 2008. Adoption of e-procurement in Hong Kong: empirical research. International Journal of Production Economics, Vol. 113, pp. 159–175. [CrossRef]

- Gurakar, E. C. and Tas, B. K. O. 2016. Does public e-procurement deliver what it promises? Empirical evidence from Turkey. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, Vol. 52, pp. 2669–2684. [CrossRef]

- Gurgun, A. P., Kunkcu, H., Koc, K., Arditi, D., and Atabay, S. 2024. Challenges in the Integration of E-Procurement Procedures into Construction Supply Chains. Buildings, 14(3), 605. [CrossRef]

- Hajdari, B. Technical Parts for Application E-Procurement in the Republic of Kosovo. Prizren Social Science Journal 2018, 2, 96–108. [Google Scholar]

- Hamma-adama, M., and Ahmad, A. B. S. E. 2021. Challenges and Opportunities of E-Procurement in the Construction Industry. Journal of Construction Materials, Vol. 2, pp. 4–7. [CrossRef]

- Hanak, T., Chadima, T., & Šelih, J. 2017. Implementation of online reverse auctions: Comparison of Czech and Slovak construction industry. Engineering Economics, 28(3), 271-279. [CrossRef]

- Hasan, H. B. 2017. A study on the implementation of e-GP (Electronic Government Procurement System) in public works department: impact on present procurement practices and future scopes, Doctoral dissertation, BRAC University, Dhaka, Bangladesh.

- Hashim, N.; Man, M.Y.S.; Kamarazaly, M.A.H.; King, S.L.S.; Ling, S.S.C.A.; Yaakob, S.A.M. The application of the paperless concept in Malaysian construction e-tendering system, from QS consultants’ perspective. Journal of Built Environment, Technology, and Engineering 2020, 8, 101–110. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, H. 2013. Factors affecting the extent of e-procurement use in small and medium enterprises in New Zealand: Ph.d thesis, Business Information Systems, Massey University, Manawatu Campus, New Zealand.

- Hassan, M. 2021. Implementation of E-Procurement with BIM collaboration in the Construction Industry. MSc. Thesis in Construction and Real Estate Management, Metropolia UAS and HTW Berlin, Germany.

- Hayden, E., van Kan, D., Chan, M., Arowoiya, V., and Mohamed, M. 2023. Chapter E-Procurement in the Australian Construction Industry: Benefits, Barriers, and Adoption. CONVR 2023. Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Construction Applications of Virtual Reality, 13 to 16 November 2023, Florence, Italy, pp. 489–498. [CrossRef]

- Hilmi, R., Breesam, H., and Saleh, A. 2019. Readiness for E-Tendering in the Construction Sector- Designing a Computer Programme. Civil Engineering Journal. [CrossRef]

- Hossain, S. 2016. The prospects and challenges of E-Government Procurement (E-GP) in Bangladesh case study on the Public Works Department (PWD). Ph.D Thesis, BRAC University, Dhaka, Bangladesh.

- Ibem, E.O.; Laryea, S. e-Procurement use in the South African construction industry. Journal of Information Technology in Construction (ITcon) 2015, 20, 364–384. [Google Scholar]

- Ibem, E. O. and Laryea, S. 2017. E-tendering in the South African construction industry. International Journal of Construction Management, Vol.17, pp. 310–328. [CrossRef]

- Ibem, E. O., Aduwo, E. B. and Ayo-Vaughan, E. A. 2017. e-Procurement adoption in the Nigerian building industry: Architects’ perspective. Pollack Periodica, Vol. 12, pp. 167–180. [CrossRef]

- Ibem, E., Aduwo, E., Afolabi, A., Oluwunmi, A., Tunji-Olayeni, P., Ayo-Vaughan, E., and Uwakonye, U. 2021. Electronic (e-) Procurement Adoption and Users’ Experience in the Nigerian Construction Sector. International Journal of Construction Education and Research, 17, 258 - 276. [CrossRef]

- Ilhan, N., and Rahim, M. M. 2017. Benefits of e-procurement systems implementation: Experience of an Australian municipal council. In Digital Governance and E-Government Principles Applied to Public Procurement, IGI Global, pp. 249–266. [CrossRef]

- Isikdag, U. An evaluation of barriers to e-procurement in the Turkish construction industry. International Journal of Innovative Technology and Exploring Engineering 2019, 8, 252–259. [Google Scholar]

- Isikdag, U., Underwood, J., Ezcan, V., and Arslan, S. 2011. Barriers to e-procurement in the Turkish AEC industry. In Proceedings of the CIB W78-W102 2011: International Conference–Sophia Antipolis, France, Vol. 26, pp. 28–38.

- Isimbi Uwadede, D. 2016. Adoption of e-procurement and implementation of basic principles of public procurement in Rwanda, Doctoral dissertation, University of Rwanda, Kigali, Rwanda.

- Issabayeva, S., Yesseniyazova, B., and Grega, M. 2019. Electronic public procurement: Process and cybersecurity issues. NISPAcee Journal of Public Administration and Policy, 12(2), 61-79. [CrossRef]

- Jama, E. M., Mwanza, B. G., & Mwanaumo, E. M. 2024. E-procurement Adoption Barriers encountered by Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs) in the Republic of South Sudan. African Journal of Commercial Studies, 4(1), 48-68. [CrossRef]

- Jayawardhena, M. U. G., & Jayaratne, P. 2019. Evaluation of Adopting E-Procurement and Its Impact on Performance in Apparel Supply Chain in Sri Lanka. 9th International Conference on Operations and Supply Chain Management, 15 – 18 December 2019, RMIT University, Vietnam, pp. 1–12.

- Jayawardhena, M. , and Jayaratne, P. 2018. Evaluation of e-procurement adoption and its impact on apparel supply chain performance. R4TLI Conference Proceedings, pp. 1–5.

- Kajewski, S. and Weippert, A. 2004. E-Tendering: Benefits, challenges, and recommendations for practice. In Williams, K (Ed.) Clients Driving Innovation CRC Construction Innovation International Conference Proceedings. Australian Cooperative Research Centre for Construction Innovation, CD ROM, pp. 1–11.

- Kamotho, D. K. 2014. E-procurement and procurement performance among state corporations in Kenya, Doctoral dissertation, University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya.

- Kanyambo, M. 2017. Challenges affecting the implementation of e-procurement in the Malawi Public Sector: -The Case of Malawi Housing Corporation, Lilongwe City Council, Kamuzu Central Hospital, Immigration Department and Malawi Defence Force, Doctoral dissertation, University of Bolton, Bolton, UK.

- Kazaz, A. , Inusah, Y., & Ulubeyli, S. 2022. Barriers to e-tendering adoption and implementation in the construction industry: 2010–2022 Review. In Conference: 7th International Project and Construction Management Conference At: Istanbul (pp. 2010–2022).

- Kelechi, G.; Amade, B.; Okereke, G. Implementation of e-procurement in mitigating corrupt practices in construction project delivery. PM World Journal 2024, 13, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Khahro, S.H.; Hassan, S.; Zainun NY, B.; Javed, Y. Digital Transformation and E-Commerce in Construction Industry: A Prospective Assessment. Academy of Strategic Management Journal 2021, 20, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Khalil, C. 2015. Towards the adoption of E-Tendering in the public sector of the Egyptian construction industry Master's Thesis, the American University in Cairo. AUC Knowledge Fountain. pp. Cairo, Egypt, 1-149.

- Khalil, C. A. and Waly, A. F. 2015. Challenges and Obstacles facing Tenderers Adopting e-Tendering in the Public Sector of the Construction Industry in Egypt. 5th International. In 11th Construction Specialty Conference, Vancouver, British Columbia, Vol. 8, pp. 086–10. [CrossRef]

- Korir, S.; Afande, F.O.; Maina, P. Constraints to effective implementation of E-procurement in the public sector: A survey of selected Government Ministries in Kenya. Journal of Information Engineering and Application 2015, 5, 59–83. [Google Scholar]

- Laryea, S. and Ibem, E. 2014. Barriers and prospects of e-procurement in the South African construction industry. Paper presented at the 7th Annual Quantity Surveying Research Conference, CSIR International Convention Centre; 21 – 23 September 2014, Pretoria, South Africa.

- Lines, B. C., Perrenoud, A. J., Sullivan, K. T., Kashiwag, D. T., & Pesek, A. 2017. Implementing Project Delivery Process Improvements: Identification of Resistance Types and Frequencies. Journal of Management in Engineering, 33(1), 04016031. [CrossRef]

- Lou EC, W.; Alshawi, M. Critical success factors for e-tendering implementation in construction collaborative environments: people and process issues. Journal of Information Technology in Construction 2009, 14, 98–109. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y. , Li, Y., Skibniewski, M., Wu, Z., Wang, R. and Le, Y. 2015. Information and communication technology applications in architecture, engineering, and construction organizations: a 15-year review, Journal of Management in Engineering, Vol. pp. 31, 1-19. [CrossRef]

- Maepa, D. N., Mpwanya, M. F., and Phume, T. B. 2023. Readiness factors affecting e-procurement in South African government departments. Journal of Transport and Supply Chain Management, 17(0), a874. [CrossRef]

- Maleki, M., Karimi, M., Reyan, H. and Cruz-Machado, V. 2017. E-Procurement Platform Implementation Feasibility Study and Challenges: A Practical Approach in Iran. In Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on Management Science and Engineering Management, Springer, Singapore, pp. 843–855. [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, G. and Sloan, B. 2001. The potential impact of electronic procurement and global sourcing within the UK construction industry. In Proceedings of ARCOM 17th Annual Conference, University of Salford, UK, pp. 231–239.

- Mehdipoor, A., Iordanova, I., Mehdipoorkaloorazi, S., & Ghadim, H. 2022. Implementation of Electronic Tendering in Malaysian Construction Industry: A Case Study in The Preparation and Application of E-Tendering. International Journal of Automation and Digital Transformation. Vol. 1, pp. 69–74. [CrossRef]

- Mind Commence, 2022. ICT infrastructure. https://mindcommerce.com/report-category/ict-infrastructure/#read-more. Date of access 30.06.2022.

- Mobayo, J.O.; Makinde, J.K. Assessment of the Prospects and Challenges of E-Procurement Practices COVID-19. Built Environment Journals 2020, 20, 13–23. [Google Scholar]

- Moges Dereje, H., & Assefa Habete, G. 2023. The Adoption of Electronic Procurement and Readiness Assessment in Central Ethiopia Regional State). International Journal of Engineering and Advanced Technology (IJEAT), ISSN: 2249-8958 (Online), Volume-13 Issue-5, June 2024, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4869967 or. [CrossRef]

- Mohamad Bohari, A.A.; Zulkifi MZ, A.; Sebri, N.I.; Mahat, N. E-Procurement Implementation Challenges During The COVID-19 Pandemic COVID-19. Built Environment Journals 2023, 20, 13–23. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed, S. 2013. Towards E-Procurement implementation in Tanzania: construction industry preparedness. B.Sc. Thesis, Ardhi University, Tanzania.

- Mohd Nawi, M.N.; Deraman, R.; Bamgbade, J.A.; Zulhumadi, F.; Mehdi Riazi, S.R. E-procurement in Malaysian construction industry: benefits and challenges in implementation. International Journal of Supply Chain Management (IJSCM) 2017, 6, 209–213. [Google Scholar]

- Mohungoo, I., Brown, I., & Kabanda, S. 2020. A systematic review of implementation challenges in public E-Procurement. In Responsible Design, Implementation and Use of Information and Communication Technology: 19th IFIP WG 6.11 Conference on e-Business, e-Services, and e-Society, I3E 2020, Skukuza, South Africa, April 6–8, 2020, Proceedings, Part II 19 (pp. 46–58). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Motaung, J. R. , & Sifolo, P. P. S. 2023. Benefits and Barriers of Digital Procurement: Lessons from an Airport Company. Sustainability. [CrossRef]

- Mukelas, M. F. M. and Zawawi, E. A. 2012. Theoretical framework for ICT implementation in the Malaysian construction industry: Issues and challenges. In 2012 International Conference on Innovation Management and Technology Research, IEEE, 21-22 May 2012, Malacca, Malaysia, pp. 275–279. [CrossRef]

- Mukhongo, R.A.; Aila, F.O. Assessment of road contractors’ e-procurement adoption barriers in Kenya rural roads authority, Kenya. International Journal of Development and Sustainability 2018, 7, 1286–1298. [Google Scholar]

- Musa, U., Jaafar, M., and Raslim, F. M. 2023. E-procurement adoption in Nigeria: perceptions from the public sector employees. Arab Gulf Journal of Scientific Research. [CrossRef]

- Naeem, M. 2021. Uncovering and Addressing the Challenges in the Adoption of E-Procurement System: Adoption Process Stages in SMEs. International Journal of Information Systems and Supply Chain Management (IJISSCM), 14, pp. 1–22. [CrossRef]

- Nasirian, A. , Arashpour, M. and Abbasi, B. 2019. Critical literature review of labor multiskilling in construction, Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, Vol. 145 No. 1, pp. 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Ndubuaku, N. G. , and Jerry, G. 2023. Utilizing e-Tendering in the Procurement of Construction Projects. In Global Market and Trade. IntechOpen. [CrossRef]

- Neef, D. 2001. E-procurement: From strategy to implementation. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Financial Times/Prentice Hall. ISBN: 0130914118.

- Nizakat, R. Z., Memon, N. A., Vighio, A. A., Mustafa, A., and Hussain, A. 2022. E-procurement in the construction industry of Pakistan: A case study of contractor related to public sector projects. International Research Journal of Modernization in Engineering Technology and Science, 4(4), 1046. https://www.irjmets.com.

- Nkhata, J. B. 2014. E-Procurement of Construction Materials in The Malawi Construction Industry. BSc. Thesis. The Polytechnic, University of Malawi, Malawi.

- Nurmandi, A. and Kim, S. 2015, Making e-procurement work in a decentralized procurement system: A comparison of three Indonesian cities, International Journal of Public Sector Management, Vol. 28 No. 3, pp. 198–220. [CrossRef]

- Ofori, D., and Fuseini, O. I. 2019. Electronic government procurement adoption in Ghana: critical success factors. Advances in Research, Vol. 21, pp. 18–34. [CrossRef]

- Owusu, F. D. 2015. The readiness of public procurement entities in Ghana for e-procurement: Perspective of procurement practitioners in the road sector in Ghana (Masters dissertation, Dept. of Building Technology, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana.

- Oyediran, O.S.; Akintola, A.A. A Survey of the State of the Art of E-Tendering in Nigeria. Journal of Information Technology in Construction (ITcon) 2011, 16, 557–576. [Google Scholar]

- Ozumba, A. O. U., & Shakantu, W. 2018. Exploring challenges to ICT utilization in construction site management. Construction innovation, 18(3), 321-349. [CrossRef]

- Pala, M. , Edum-Fotwe, F., Ruikar, K., Peters, C., and Doughty, N. 2016. Implementing commercial information exchange: a construction supply chain case study. Construction Management and Economics,. [CrossRef]

- Pop, C.S. The barriers to implementing e-procurement. Studia Universitatis Vasile Goldiş, Arad-Seria Ştiinţe Economice 2011, 21, 120–124. [Google Scholar]

- Premathilaka, K.M.; Fernando RL, S. Premathilaka, K.M.; Fernando RL, S. Critical success factors affecting e-procurement adoption in public sector organizations in Sri Lanka. Journal of Business Research and Insights (former Vidyodaya Journal of Management) 2020, 6.

- Rahim, M.M.; As-Saber, S.N. E-procurement adoption process: an arduous journey for an Australian city council. International Journal of Electronic Finance 2011, 5, 150–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizki, A. A. 2019. The Impact of E-Procurement Implementation in Infrastructure Projects. Jurnal Ilmiah Administrasi Publik, 5(3), 420-431. [CrossRef]

- Saidu, I.; Abubakar, M.I.; Ola-Awo, W.; Oke, A.; Alumbugu, P.O. Implementation of E-Procurement in Public Building Projects of the Federal Capital Territory Administration, Abuja. Environmental Technology & Science Journal 2020, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Salifu, Z. N., Nangpiire, C., Dawdi, A. A., and Yussif, F. 2023. Assessing the Extent of Electronic Procurement Adoption Challenges in the Public Sector of Ghana. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues, 13(2), 72-78. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Rodríguez, C.; Martínez-Lorente, A.R.; Hemsworth, D. E-procurement in small and medium-sized enterprises; facilitators, obstacles, and effect on performance. Benchmarking: An International Journal 2019, 27, 839–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnitzler, M. and Österlund, O. 2015. Evaluation of implementing e-procurement in the Swedish construction industry. Master’s Thesis, Jönköping International Business School. Jönköping, Sweden.

- Siahaan, A. Y. and Khamdiyah, M. 2017. The Implementation of E-Procurement Related to Government’s Goods/Services in Department of Public Works Medan. In International Conference on Public Policy, Social Computing and Development, 19th to 20th October 2017 2017. Medan, North Sumatra, Indonesia. Atlantis Press, pp. 170–174.

- Sithole, R. A. 2017. Implementation of e-procurement by the Gauteng Department of Infrastructure Development and its impact on the development of small and medium construction firms. Doctoral dissertation, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa.

- Solanke, B. H. and Fapohunda, J. A. 2015. Impacts of E-commerce on construction materials procurement for sustainable construction. IEEE, In 2015 World Congress on Sustainable Technologies (WCST), pp. 65–70.

- Songok, J. 2018. E-Procurement Implementation and Performance of Public Universities in Kenya. Doctoral dissertation, University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya.

- Sunmola, F. T. and Shehu, Y. U. 2020. A Case Study on Performance Features of Electronic Tendering Systems. Procedia Manufacturing, 51, 1586–1591. [CrossRef]

- Svidronova, M.M.; Nemec, J. E-Procurement in Self-Governing Regions in Slovakia. Lex Localis-Journal of Local Self-Government 2016, 14, 324–337. [Google Scholar]

- Svidronova, M. M., and Mikus, T. 2015. E-procurement as the ICT innovation in the public services management: the case of Slovakia. Journal of Public Procurement, 15(3), 317-340. [CrossRef]

- Sydorenko, O. The influence of the implementation of E-tendering on the competitiveness of small and medium enterprises in the construction industry. Economics & Education 2017, 2, 35–40. [Google Scholar]

- Syed, A. M. Z. 2016. Barriers to Governmental Sector E-bidding Within Saudi Arabia’s Construction Industry. Doctoral dissertation, King Fahd University of Petroleum and Minerals, Saudi Arabia.

- Tan JJ, R.; Suhana, K. Application of e-tendering in the Malaysian construction industry. INTI Journal Special Edition–Built Environment 2016, 94–101. [Google Scholar]

- Tjan, I.; Basalamah MS, I.A.; Sirat, A.H. Assessment of E-Procurement of Construction Products and Services. Jurnal Manajemen Bisnis 2023, 10, 206–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toktaş-Palut, P.; Baylav, E.; Teoman, S.; Altunbey, M. The impact of barriers and benefits of e-procurement on its adoption decision: An empirical analysis. International Journal of Production Economics 2014, 158, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, Q.; Drew, S.; Stewart, R.A. Evolutionary Model of e-Procurement Adoption: A Case of the Vietnam Construction Industry. International Journal of Sustainable Construction Engineering and Technology 2021, 12, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, Q.D.; Nguyen TQ, T.; Nazir, S. Initial adoption vs. institutionalization of e-procurement in construction firms: the role of government in developing countries. International Journal of Enterprise Information Systems 2014, 10, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, Q.; Zhang, C.; Sun, H.; Huang, D. Initial adoption versus institutionalization of e-procurement in construction firms: An empirical investigation in Vietnam. Journal of Global Information Technology Management 2014, 17, 91–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udo, N. E., Ekanem, S. N. and Ibrahim, S. 2020. The adoption of an e-tendering system for Nigerian construction contract issues and the way forward. Proceedings of the 5th Research Conference of the NIQS (RECON 5), Nigeria. pp. 754–763.

- Umi Kalsuma, Z.Z.; Lee Honga, M.; Siti Nor Azniza Ahmad, S. E-tendering: Improvement model in Malaysia public sector’s construction industry. Malaysian Construction Research Journal 2021, 12, 271–286. [Google Scholar]

- Vu, D. 2024. Digital Transformation E-procurement: Analyse of The Barriers to applying E-procurement in Vietnamese SMEs. Thesis, Lapland University of Applied Sciences, Vietnam.

- White, K. M., & Clarkson, P. J. 2024. Exploring the barriers to innovation adoption in the UK construction industry. 18th International Design Conference (DESIGN 2024), Cavtat, Dubrovnik, Croatia 20 - 23 May 2024, (Proceedings of the Design Society), 4, 2473-2482.

- Wimalasena, N.N.; Gunatilake, S. The readiness of construction contractors and consultants to adopt e-tendering: The case of Sri Lanka. Construction Innovation 2018, 18, 350–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, B.; Skitmore, M.; Xia, B. A critical review of structural equation modeling applications in construction research. Automation in Construction 2015, 49, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yevu, S.K.; Yu, A.T.W. The ecosystem of drivers for electronic procurement adoption for construction project procurement: A systematic review and future research directions. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management 2019, 27, 411–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yevu, S. K., Yu, A. T. W., and Darko, A. 2021. Barriers to electronic procurement adoption in the construction industry: a systematic review and interrelationships. International Journal of Construction Management, pp. 964–978. [CrossRef]

- Yevu, S.K.; Yu AT, W.; Nani, G.; Darko, A.; Tetteh, M.O. Electronic procurement systems adoption in construction procurement: A global survey on the barriers and strategies from the developed and developing economies. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management 2022, 148, 04021186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Perera, S.; Udeaja, C.; Ru, X. 2012. The state of the art in e-business: a case study from the Chinese construction industry. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Innovation in Architecture, Engineering and Construction (AEC), August 15-17, 2012, Sao Paulo, Brazil.

- Zunk, B.M.; Marchner, M.; Uitz, I.; Lerch, C.; Schiele, H. The role of E-procurement in the Austrian construction industry: Adoption rate, benefits and barriers. International journal of industrial engineering and management 2014, 5, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Factors | Author |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Inadequate technical/ICT skilled personnel | [1, 3, 4, 6, 5, 7, 8, 11, 13, 14, 15, 16, 18, 19, 20, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 30, 33, 34] |

| 2 | Lack of data integrity/trust/ lack of security of data/authentication/Privacy issues/Confidentiality of information/Cybersecurity Risks | [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 21, 24, 26, 27, 28, 31, 33, 34] |

| 3 | Lack of uniform standard or policy and Inadequate legal framework | [1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12, 14, 15, 17, 20, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 30, 33, 34, 35] |

| 4 | High investment cost of implementation/Lack of financial resource | [1, 3, 4, 6, 5, 7, 8, 9, 11, 15, 16, 17, 23, 24, 25, 29, 34, 35] |

| 5 | Reluctance/ resistance to change/ internal cultural issues | [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 11, 18, 19, 23, 25, 29, 31, 32, 34, 35] |

| 6 | Inadequate ICT and internet infrastructure / Poor IT infrastructure to support e-tendering systems | [5, 6, 8, 10, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 20, 18, 21, 23, 25, 28, 30, 31, 32, 34, 35] |

| 7 | Lack of Support | [3, 4, 5, 6, 10, 11, 15, 20, 19, 23, 24, 27, 32, 34] |

| 8 | Technological updates/high maintenance cost/Technical malfunctioning of the portal | [2, 5, 7, 11, 12, 13, 15, 20, 21, 23, 34] |

| 9 | Lack of trust and awareness of benefits of e-procurement systems, skepticism/ Insufficient promotion and understanding of e-tendering among stakeholders/Difficulties in engaging stakeholders. | [1, 5, 11, 16, 19, 23, 24, 25, 27, 28, 29, 35] |

| 10 | Poor communication | [3, 4, 6, 10, 14, 15, 20, 23, 24, 25] |

| 11 | Software non-compatibility / interoperability issues | [4, 6, 9, 10, 13, 15, 19, 21, 35] |

| 12 | Complex user interface | [3, 10, 20, 23] |

| 13 | Unethical practices (transparency issues) | [23, 27] |

| 14 | Inadequate monitoring of supplier’s compliance/ lack of performance evaluation | [25, 33] |

| 15 | Lack of planning | [28, 34] |

| 16 | Change Management | [29, 32] |

| 17 | Lack of mobile applications | [22] |

| 18 | Lack of best practices and pilot projects | [27] |

| 19 | Dual operation mode difficulty (traditional & digital) | [29] |

| 20 | The choice of suppliers is too arbitrary and the lack ofscientific management/ many suppliers leading to the complex evaluation process | [33] |

| No. | Factors | Author |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Reluctance/ resistance to change/ internal cultural Issues | [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 15] |

| 2 | High investment cost of implementation/Lack of financial resource | [1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, 13, 14, 15] |

| 3 | Lack of uniform standard or policy/Inadequate legal framework | [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 13, 14, 15] |

| 4 | Inadequate data security challenges/ Cyber security issues | [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 12, 15] – (11) |

| 5 | Inadequate ICT and Internet infrastructure/weak infrastructure | [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 10, 12, 13, 15] |

| 6 | Lack of Support | [2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 13, 14, 15] |

| 7 | Inadequate technical/skilled personnel/ lack of education and training | [1, 6, 7, 8, 9, 13, 14, 15] |

| 8 | Software non-compatibility / interoperability issues | [1, 4, 5, 6, 7, 10, 12] |

| 9 | Lack of trust and awareness of the benefits of e-procurement systems | [1, 3, 7, 9, 14] |

| 10 | Technical malfunctioning of the portal/ Internet and technical challenges | [4, 5, 7,13] |

| 11 | Dual operation mode difficulty (traditional & digital)/Deficiency in merging systems | [15] |

| No. | Factors | Author |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lack of uniform standard or policy and Inadequate legal framework/ Legal and regulatory challenges | [2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 15, 16, 17, 20, 22, 25, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 36 |

| 2 | Reluctance/ resistance to change | [1, 2, 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 16, 17, 18, 19, 23, 25, 27, 28, 29, 31, 32, 33, 36] |

| 3 | Inadequate technical/ICT skilled personnel/ Lack of knowledge regarding e-tendering/ inadequate computing skills | [1, 2, 4, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 17, 18, 19, 20, 22, 25, 27, 29, 31, 32] |

| 4 | Software non-compatibility / interoperability | [1, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, 13, 16, 17, 21, 18, 22, 27, 29, 30, 31, 32, 34, 35] |

| 5 | Inadequate data security challenges/Cyber security issues | [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 27, 30, 31, 32, 34] |

| 6 | Inadequate ICT and Internet infrastructure/Undeveloped infrastructure | [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 9, 12, 14, 16, 24, 25, 27, 28, 31, 32, 34] |

| 7 | Lack of Support | [1, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 16, 17, 20, 25, 32] |

| 8 | High investment cost of implementation | [4, 5, 6, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 27, 31, 32, 33] |

| 9 | Lack of trust, skepticism, and awareness of benefits of e-procurement systems/Lack of information/ limited publicity/ Lack of commitment from suppliers | [1, 7, 8, 9, 11, 13, 16, 17, 18, 24, 25, 26, 37] |

| 10 | User unfriendliness and inflexibility of the electronic system / complex interface | [8, 10,11,12, 25, 27, 28, 29, 31, 36] |

| 11 | Infective communication | [8, 10,11,12, 25, 27, 28, 29, 31, 36] |

| 12 | There is a lack of a forum for exchanging ideas on e-procurement/ lack of pioneering firms and pilot projects/insufficient case availability. | [8, 9, 10, 11, 26, 31] |

| 13 | Other competing initiatives, Excessive number of e-platforms, Competition amongst hub-providers | [8, 11, 12, 17, 25, 31] |

| 14 | Technical malfunctioning of the portal | [9, 10, 12, 17, 18] |

| 15 | Lack of widely accepted e-procurement software | [6, 8, 10, 11, 17] |

| 16 | Inadequate change management | [25] |

| 17 | Inadequate clear identification of roles/responsibilities | [25] |

| 18 | Lack of production planning system | [31] |

| 19 | Many suppliers leading to the complex evaluation process | [31] |

| 20 | High transaction frequency leads to inefficient procurement | [31] |

| 21 | Poor relationship with suppliers | [32] |

| No. | Factors | Author |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | High investment cost of implementation/ High costs of software and hardware | [1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8] |

| 2 | Reluctance/ resistance to change | [1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8] |

| 3 | Inadequate technical/ICT skilled personnel | [1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 8] |

| 4 | Inadequate or data security challenges | [1, 2, 3, 6, 7, 8] |

| 5 | Lack of trust and awareness of benefits of e-procurement systems/difficulty in judging the usefulness and potential of e-tendering/Lack of Information | [2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8] |

| 6 | Lack of Support | [2, 3, 4, 7, 8] |

| 7 | Lack of legal frameworks and standards supporting the adoption of the selected technology/policies, regulations, and standards | [1, 3, 7] |

| 8 | Technical malfunctioning of the portal | [2, 3] |

| 9 | High complexity of the selected technology dissemination system/System Complexity | [7, 8] |

| 10 | Lacks widely used e-procurement software solutions | [1] – (1) |

| 11 | Software Compatibility Issues/Interoperability challenges | [7] – (1) |

| 12 | Lack of public demand for the selected technology | [7] – (1) |

| 13 | Inadequate research in IT in construction (R&D)/inadequate pilot studies | [7] – (1) |

| 14 | Unethical practices | [8] – (1) |

| No. | Factors | Author |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Inadequate ICT and Technological Capacity | [1, 2, 3, 5,7, 8] |

| 2 | Inadequate data security challenges | [1, 2, 3, 5] |

| 3 | Reluctance/ resistance to change/ internal cultural issues (Cultural elements, organization, and strategy) | [1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8] |

| 4 | User Experience Issues/Complex user interface | [1, 3, 2, 8] |

| 5 | High investment cost of implementation/ Budget Constraints | [3, 2, 5, 7, 8] |

| 6 | Lack of Support | [1, 2, 8] |

| 7 | Inadequate technical/skilled personnel/ Inadequate in-house IT personnel/Inadequate training | [1, 2, 8] |

| 8 | Inadequate research in IT in construction (R&D)/ inadequate pilot studies | [3, 5] |

| 9 | Technical malfunctioning of the portal | [2] |

| 10 | Lack of uniform standard or policy/ Complex Regulations/legal challenges | [3, 7, 8] |

| 11 | Lack of widely used e-procurement software solutions | [3] |

| No. | Barrier | Frequency/ Rank | Africa | Asia | Middle East & North Africa | Europe | Pacific | North America |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Inadequate data security/ Cybersecurity issues | 101 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 2. | Reluctance/resistance to change | 101 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 3. | Inadequate legal framework or lack of uniform standards or policies | 100 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 4. | Inadequate technical/ ICT skilled personnel |

97 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 5. | Inadequate ICT and Internet infrastructure | 88 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 6. | High investment cost of implementation/High technology cost | 84 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 7. | Lack of Support/ Lack of Management Support | 69 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 8. | Lack of trust and awareness of the benefits of e-procurement systems | 56 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | X |

| 9. | Software non-compatibility /interoperability issues | 53 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | X |

| 10. | Technical malfunctioning of the portal | 34 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 11. | Complex user interface | 24 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | X |

| 12. | Ineffective communication | 15 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | X | X |

| 13. | Unreliable electric power supply | 13 | ✓ | X | X | X | X | X |

| 14. | Insufficient forum, pioneering firms, studies, or pilot projects | 10 | X | ✓ | X | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 15. | Lack of widely used e-procurement software solutions | 7 | X | X | X | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| 16. | Unethical Practices (transparency issues) | 6 | ✓ | ✓ | X | X | ✓ | X |

| 17. | Other competing initiatives, Excessive number of e-platforms | 6 | X | X | X | ✓ | X | X |

| 18. | Lack of monitoring of supplier’s compliance/lack of performance evaluation | 5 | ✓ | ✓ | X | X | X | X |

| 19. | Lack of adequate planning | 3 | X | ✓ | X | ✓ | X | X |

| 20. | Inadequate change management | 3 | X | ✓ | X | ✓ | X | X |

| 21. | Dual operation mode difficulty (traditional & digital) | 2 | X | ✓ | ✓ | X | X | X |

| 22. | The choice of suppliers is too arbitrary and the lack of scientific management | 2 | X | ✓ | X | ✓ | X | X |

| 23. | Inadequate clear identification of roles/responsibilities | 1 | X | X | X | ✓ | X | X |

| 24. | Insufficient public demand for the selected technology | 1 | X | X | X | X | ✓ | X |

| 25. | Fear of loss of jobs | 1 | ✓ | X | X | X | X | X |

| 26. | Many suppliers leading to the complex evaluation process | 1 | X | X | X | ✓ | X | X |

| 27. | High transaction frequency leads to inefficient procurement | 1 | X | X | X | ✓ | X | X |

| 28. | Poor Relationship with Suppliers | 1 | X | X | X | ✓ | X | X |

| 29. | Lack of Mobile Applications | 1 | X | ✓ | X | X | X | X |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).