Submitted:

16 January 2025

Posted:

16 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. A. alternata Allergen Extraction and Polymerization

2.2. Analysis of the Protein and Allergenic Profile of the Extracts: SDS-PAGE and Immunoblotting

2.3. Physicochemical Analysis and Chemical Composition of the Extracts: Analysis of Amino Acid Content, Nuclear Magnetic Resonance and Mass Spectrometry

2.4. Analysis of the Allergenic Activity: IgE/IgG ELISA Competition Assays

2.5. Analysis of the Immunogenicity: Mice Immunization

2.6. Analysis of the Enzymatic Activity of Allergen Native Extracts and Allergoids

2.7. Stability of Grass Extracts in Mixture with Alternaria Allergoids

3. Results

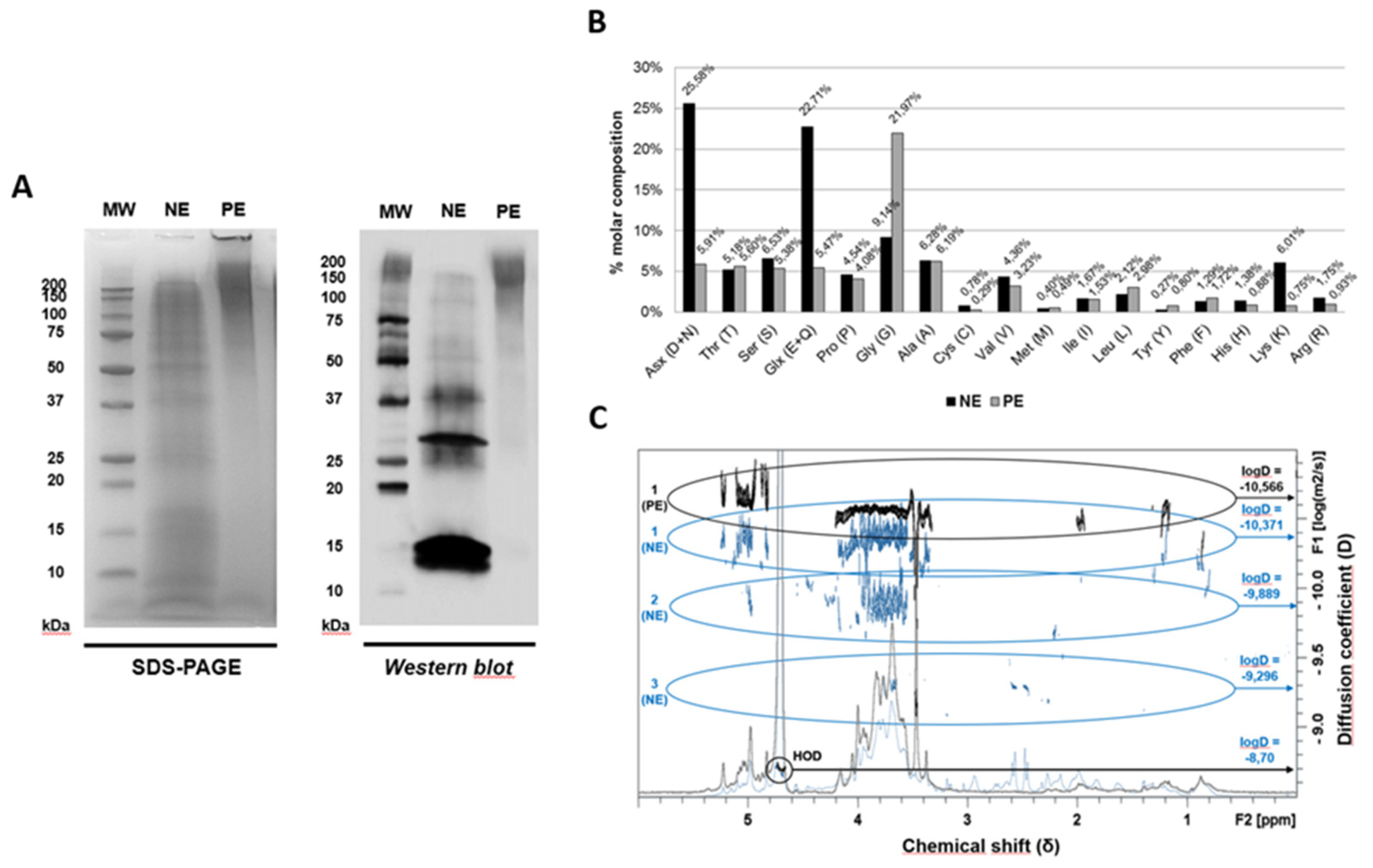

3.1. Protein and Allergenic Profile of the Extracts: SDS-PAGE and Immunoblotting

3.2. Physicochemical Composition Analysis of the Extracts: Amino acid Content, Nuclear Magnetic Resonance and Mass Spectrometry

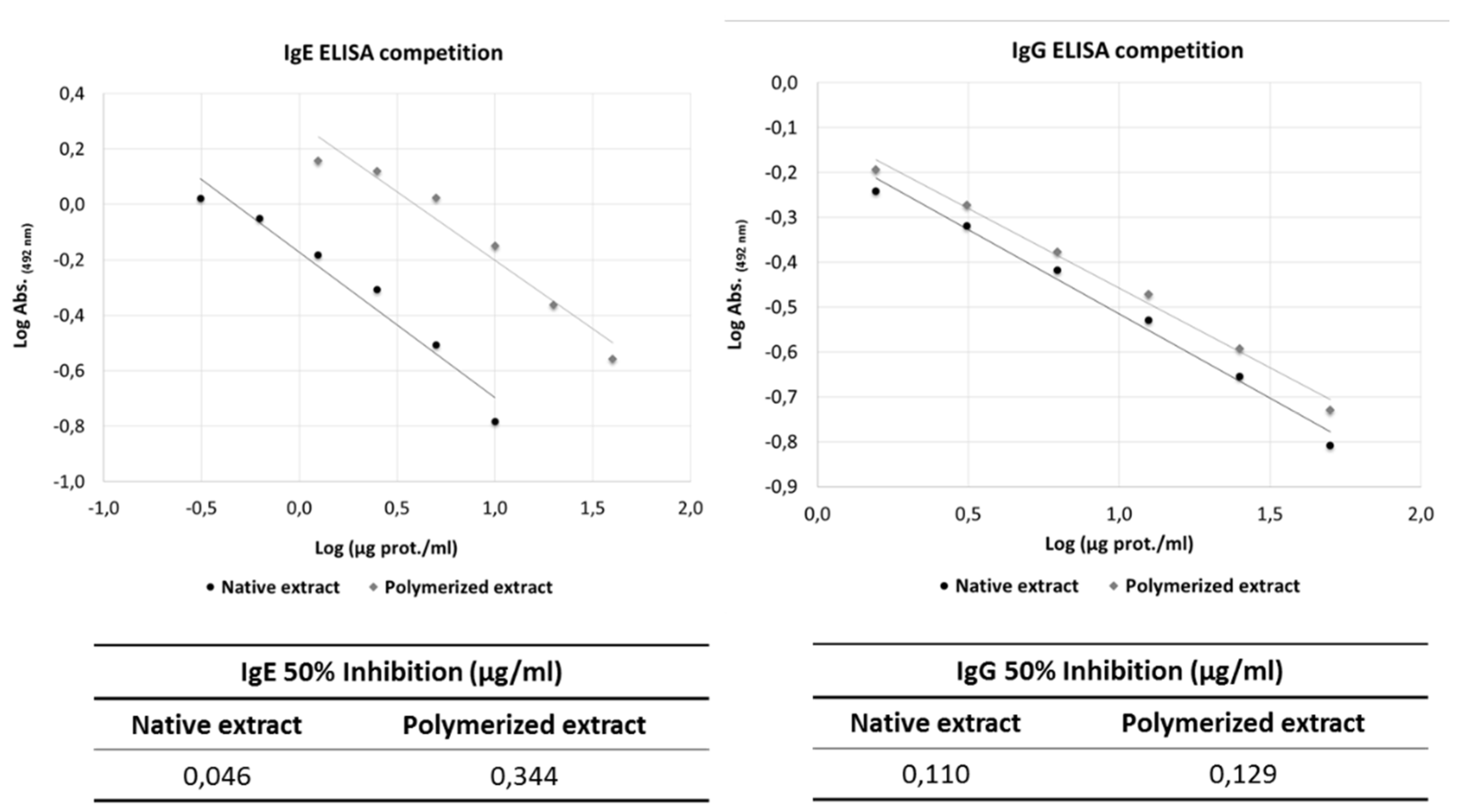

3.3. Allergenic Activity Analysis: IgE/IgG ELISA Competition Assays

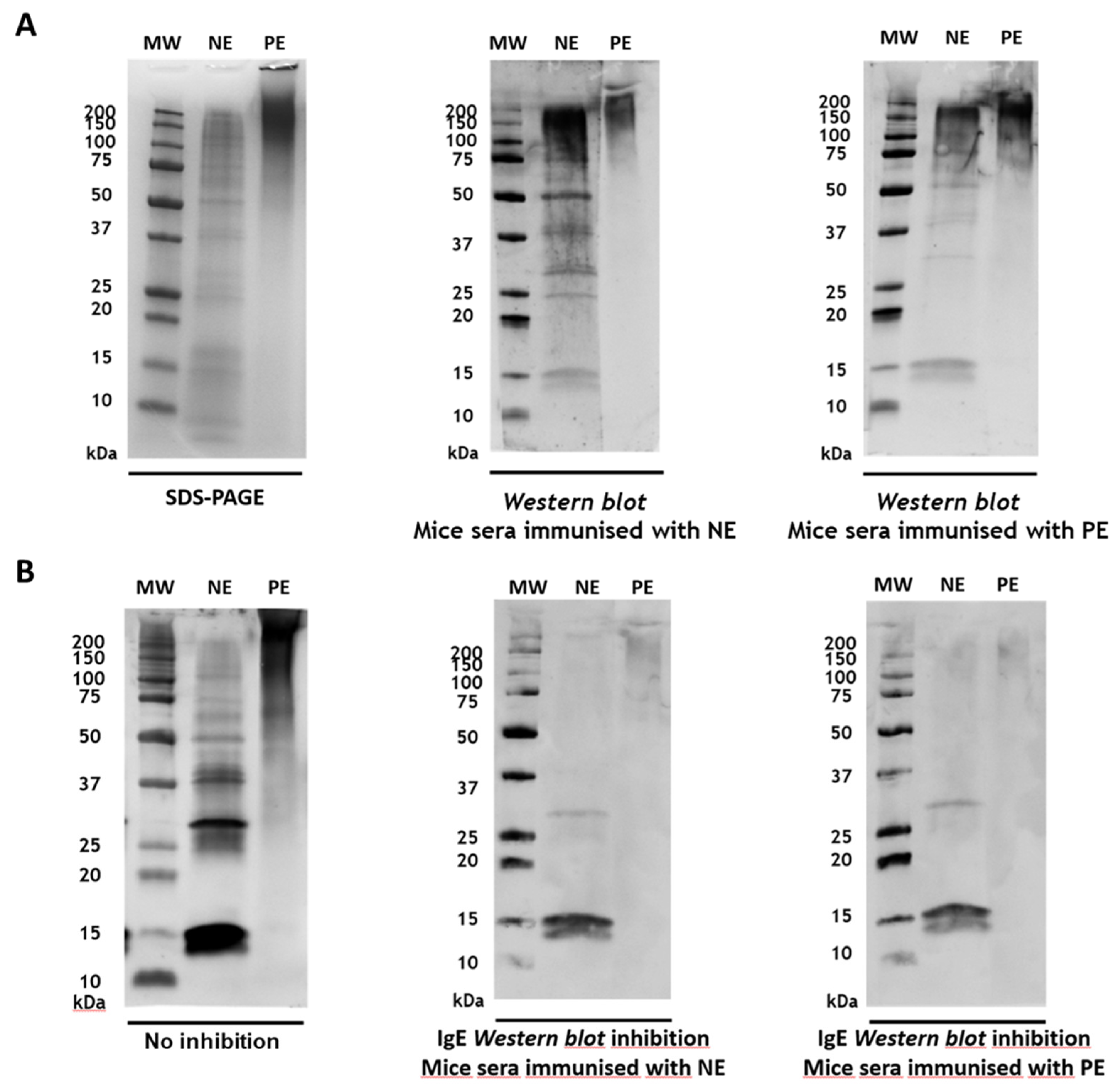

3.4. Immunogenicity and Inhibition of IgE Reactivity by Mouse IgG Antibodies Induced with A. alternata PE

3.5. Enzymatic Activity of Native and Polymerised Extracts

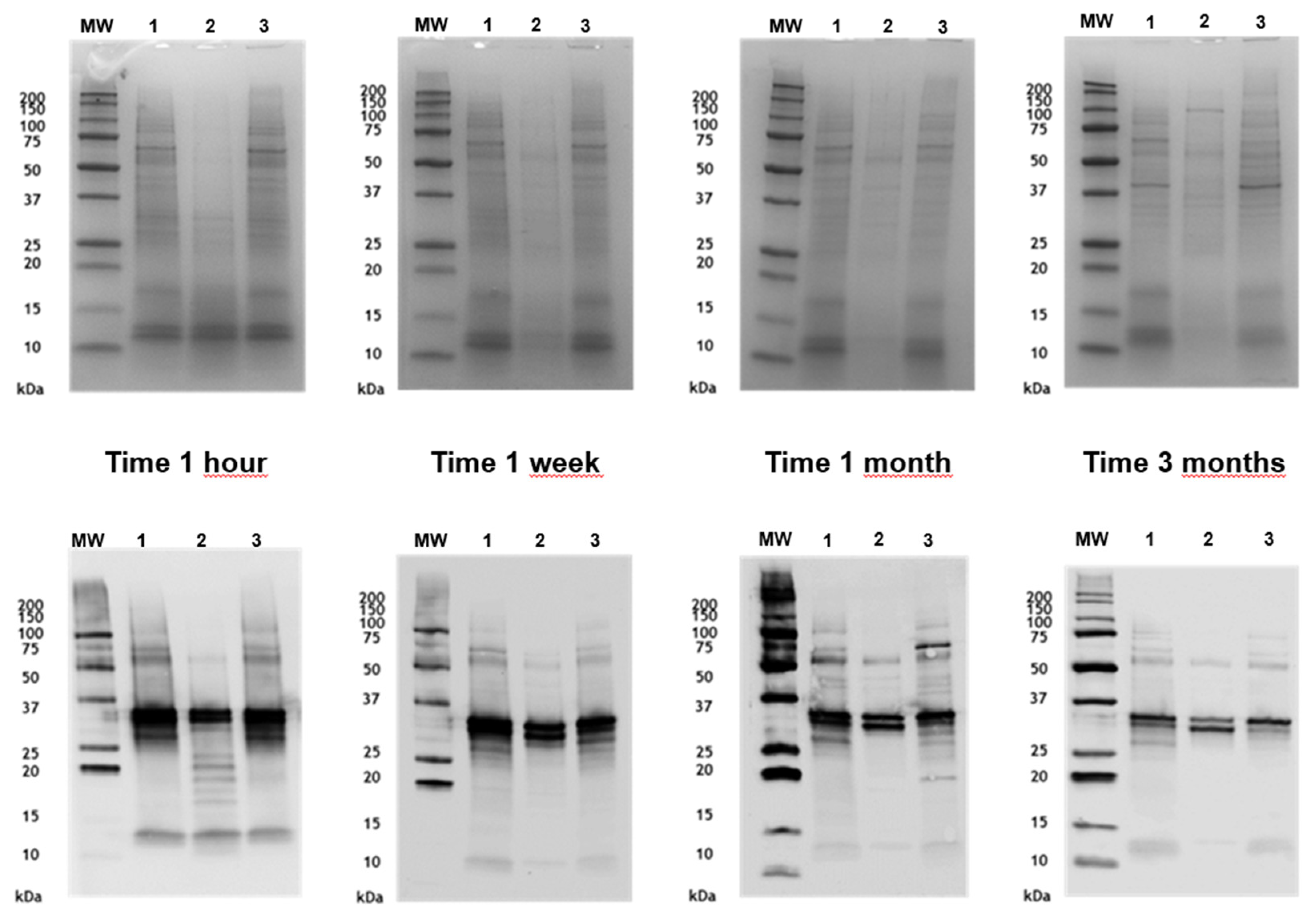

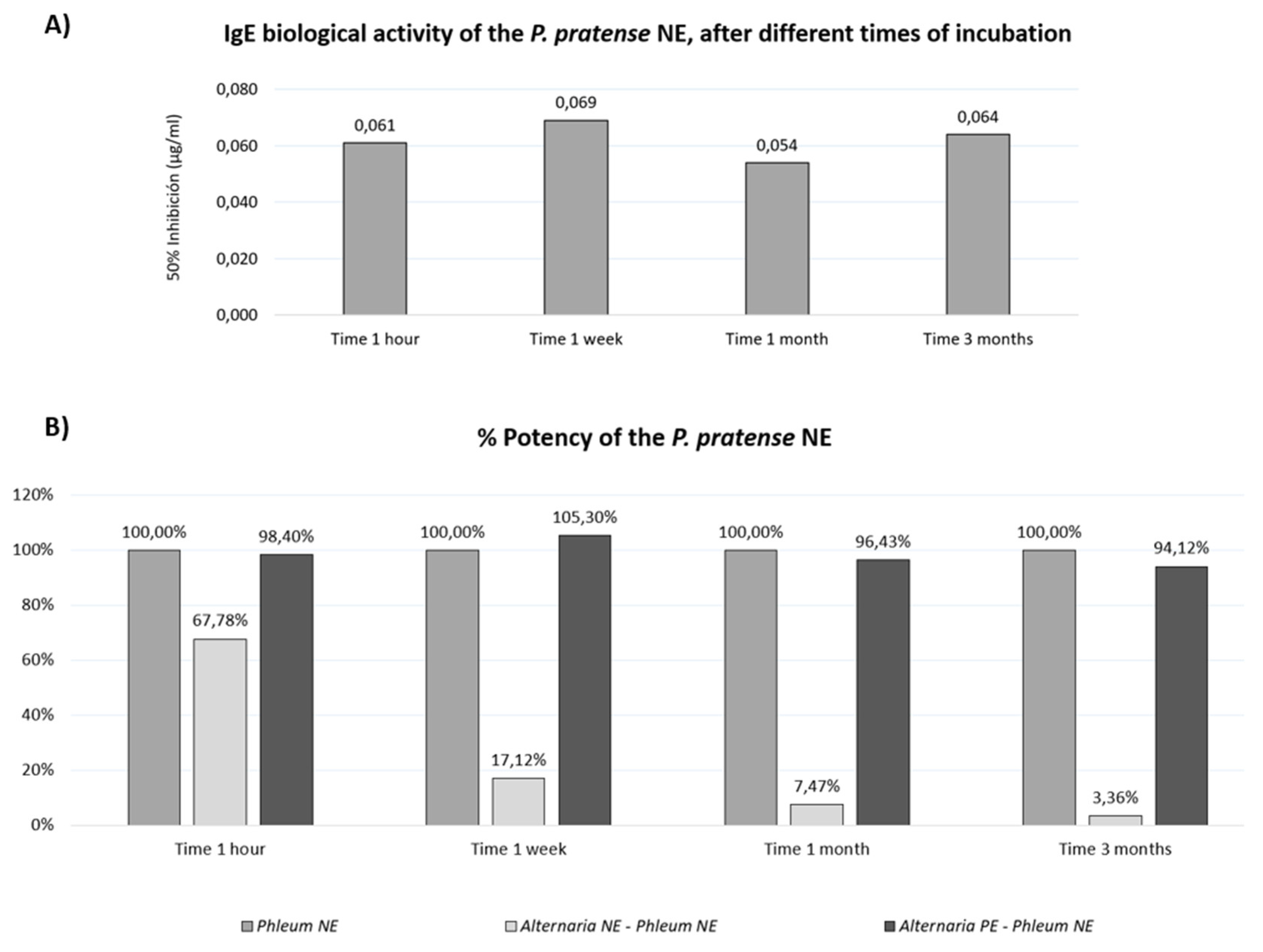

3.6. Stability of Grass Extracts in Mixture with Alternaria Allergoids

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- López Couso, V.P.; Tortajada-Girbés, M.; Rodriguez Gil, D.; Martínez Quesada, J.; Palacios Pelaez, R. Fungi Sensitization in Spain: Importance of the Alternaria alternata Species and Its Major Allergen Alt a 1 in the Allergenicity. J Fungi (Basel) 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masaki, K.; Fukunaga, K.; Matsusaka, M.; Kabata, H.; Tanosaki, T.; Mochimaru, T.; Kamatani, T.; Ohtsuka, K.; Baba, R.; Ueda, S. Characteristics of severe asthma with fungal sensitization. Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology 2017, 119, 253–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möller, C.; Dreborg, S.; Ferdousi, H.A.; Halken, S.; Høst, A.; Jacobsen, L.; Koivikko, A.; Koller, D.Y.; Niggemann, B.; Norberg, L.A.; et al. Pollen immunotherapy reduces the development of asthma in children with seasonal rhinoconjunctivitis (the PAT-study). J Allergy Clin Immunol 2002, 109, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klain, A.; Senatore, A.A.; Licari, A.; Galletta, F.; Bettini, I.; Tomei, L.; Manti, S.; Mori, F.; Miraglia del Giudice, M.; Indolfi, C. The Prevention of House Dust Mite Allergies in Pediatric Asthma. Children 2024, 11, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosca, M.A.; Licari, A.; Olcese, R.; Marseglia, G.; Sacco, O.; Ciprandi, G. Immunotherapy and Asthma in Children. Frontiers in Pediatrics 2018, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Bona, D.; Frisenda, F.; Albanesi, M. Efficacy and safety of allergen immunotherapy in patients with allergy to molds: A systematic review. 2018, 48, 1391–1401. [CrossRef]

- Brehler, R.; Rabe, U. Allergen-specific immunotherapy for mold allergies. Allergo Journal International 2024, 33, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostergaard, P.A.; Kaad, P.H.; Kristensen, T. A prospective study on the safety of immunotherapy in children with severe asthma. Allergy 1986, 41, 588–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twaroch, T.E.; Curin, M.; Valenta, R.; Swoboda, I. Mold allergens in respiratory allergy: From structure to therapy. Allergy, asthma and immunology research 2015, 7, 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaad, P.H.; Ostergaard, P.A. The hazard of mould hyposensitization in children with asthma. Clinical allergy 1982, 12, 317–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jutel, M.; Agache, I.; Bonini, S.; Burks, A.W.; Calderon, M.; Canonica, W.; Cox, L.; Demoly, P.; Frew, A.J.; O'Hehir, R.; et al. International Consensus on Allergen Immunotherapy II: Mechanisms, standardization, and pharmacoeconomics. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2016, 137, 358–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvaro-Lozano, M.; Akdis, C.A.; Akdis, M.; Alviani, C.; Angier, E.; Arasi, S.; Arzt-Gradwohl, L.; Barber, D.; Bazire, R.; Cavkaytar, O.; et al. EAACI Allergen Immunotherapy User's Guide. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. Off. Publ. Eur. Soc. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2020, 31 (Suppl. S25), 1–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akdis, M.; Akdis, C.A. Mechanisms of allergen-specific immunotherapy: Multiple suppressor factors at work in immune tolerance to allergens. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2014, 133, 621–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobsen, L.; Valovirta, E. How strong is the evidence that immunotherapy in children prevents the progression of allergy and asthma? Current opinion in allergy and clinical immunology 2007, 7, 556–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricketti, P.A.; Alandijani, S.; Lin, C.H.; Casale, T.B. Investigational new drugs for allergic rhinitis. Expert opinion on investigational drugs 2017, 26, 279–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, X.; Reihill, J.A.; Douglas, L.E.J.; Martin, S.L. Airborne indoor allergen serine proteases and their contribution to sensitisation and activation of innate immunity in allergic airway disease. Eur Respir Rev 2024, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kespohl, S.; Raulf, M. Mould allergens: Where do we stand with molecular allergy diagnostics?: Part 13 of the series Molecular Allergology. Allergo journal international 2014, 23, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, T.; Iijima, K.; Radhakrishnan, S.; Mehta, V.; Vassallo, R.; Lawrence, C.B.; Cyong, J.C.; Pease, L.R.; Oguchi, K.; Kita, H. Asthma-related environmental fungus, Alternaria, activates dendritic cells and produces potent Th2 adjuvant activity. Journal of immunology 2009, 182, 2502–2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardona Villa, R.; Yépes Núñez, J.J.; Salgado Vélez, H.; Montoya Guarín, C.J. Aspectos básicos de las reacciones de hipersensibilidad y la alergia. In Alergia. Abordaje clínico, diagnóstico y tratamiento, Panamericana, Ed. 2010; p. 736.

- Borger, P.; Koeter, G.H.; Timmerman, J.A.; Vellenga, E.; Tomee, J.F.; Kauffman, H.F. Proteases from Aspergillus fumigatus induce interleukin (IL)-6 and IL-8 production in airway epithelial cell lines by transcriptional mechanisms. The Journal of infectious diseases 1999, 180, 1267–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauffman, H.F.; Tomee, J.F.C.; van de Riet, M.A.; Timmerman, A.J.B.; Borger, P. Protease-dependent activation of epithelial cells by fungal allergens leads to morphologic changes and cytokine production. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2000, 105, 1185–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, H.Y.; Tam, M.F.; Chou, H.; Peng, H.J.; Su, S.N.; Perng, D.W.; Shen, H.D. Pen ch 13 allergen induces secretion of mediators and degradation of occludin protein of human lung epithelial cells. Allergy 2006, 61, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamhamedi-Cherradi, S.-E.; Martin, R.E.; Ito, T.; Kheradmand, F.; Corry, D.B.; Liu, Y.-J.; Moyle, M. Fungal proteases induce Th2 polarization through limited dendritic cell maturation and reduced production of IL-12. The Journal of Immunology 2008, 180, 6000–6009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boitano, S.; Flynn, A.N.; Sherwood, C.L.; Schulz, S.M.; Hoffman, J.; Gruzinova, I.; Daines, M.O. Alternaria alternata serine proteases induce lung inflammation and airway epithelial cell activation via PAR2. American journal of physiology. Lung cellular and molecular physiology 2011, 300, L605–L614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.C.; Chuang, J.G.; Su, Y.Y.; Chiang, B.L.; Lin, Y.S.; Chow, L.P. The protease allergen Pen c 13 induces allergic airway inflammation and changes in epithelial barrier integrity and function in a murine model. The Journal of biological chemistry 2011, 286, 26667–26679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snelgrove, R.J.; Gregory, L.G.; Peiro, T.; Akthar, S.; Campbell, G.A.; Walker, S.A.; Lloyd, C.M. Alternaria-derived serine protease activity drives IL-33-mediated asthma exacerbations. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology 2014, 134, 583–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanovas, M.; Fernandez-Caldas, E.; Alamar, R.; Basomba, A. Comparative study of tolerance between unmodified and high doses of chemically modified allergen vaccines of Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2005, 137, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaker, A.M.; Al-Kadah, B.; Luther, U.; Neumann, U.; Wagenmann, M. An accelerated dose escalation with a grass pollen allergoid is safe and well-tolerated: A randomized open label phase II trial. Clinical and translational allergy 2015, 6, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himly, M.; Carnes, J.; Fernandez-Caldas, E.; Briza, P.; Ferreira, F. Characterization of allergoids. Arbeiten aus dem Paul-Ehrlich-Institut (Bundesinstitut fur Impfstoffe und biomedizinische Arzneimittel) Langen/Hessen 2009, 96, 61–69. [Google Scholar]

- Manzano, A.I.; Javier Canada, F.; Cases, B.; Sirvent, S.; Soria, I.; Palomares, O.; Fernandez-Caldas, E.; Casanovas, M.; Jimenez-Barbero, J.; Subiza, J.L. Structural studies of novel glycoconjugates from polymerized allergens (allergoids) and mannans as allergy vaccines. Glycoconj J 2016, 33, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, M.; Gallego, M.; Iraola, V.; Taules, M.; de Oliveira, E.; Moya, R.; Carnes, J. In vitro evidence of efficacy and safety of a polymerized cat dander extract for allergen immunotherapy. BMC immunology 2017, 18, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passalacqua, G.; Pasquali, M.; Ariano, R.; Lombardi, C.; Giardini, A.; Baiardini, I.; Majani, G.; Falagiani, P.; Bruno, M.; Canonica, G.W. Randomized double-blind controlled study with sublingual carbamylated allergoid immunotherapy in mild rhinitis due to mites. Allergy 2006, 61, 849–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez Mosquera, M.; Sola Martinez, F.J.; Montoro de Francisco, A.; Chivato Perez, T.; Sanchez Moreno, V.; Rodriguez-Marco, A.; Hernandez-Pena, J. Satisfaction and perceived effectiveness in patients on subcutaneous immunotherapy with a high-dose hypoallergenic pollen extract. European annals of allergy and clinical immunology 2016, 48, 188–193. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Roger, A.; Depreux, N.; Jurgens, Y.; Heath, M.D.; Garcia, G.; Skinner, M.A. A novel and well tolerated mite allergoid subcutaneous immunotherapy: Evidence of clinical and immunologic efficacy. Immunity, inflammation and disease 2014, 2, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez Del Río, P.; Vidal, C.; Just, J.; Tabar, A.I.; Sanchez-Machin, I.; Eberle, P.; Borja, J.; Bubel, P.; Pfaar, O.; Demoly, P.; et al. The European Survey on Adverse Systemic Reactions in Allergen Immunotherapy (EASSI): A paediatric assessment. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. Off. Publ. Eur. Soc. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2017, 28, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abel-Fernández, E. Producción y caracterización de extractos alergénicos polimerizados de Alternaria alternata. Evaluación de su alergenicidad e inmunogenicidad. Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Madrid, España, 2017.

- Morales, M.; Gallego, M.T.; Iraola, V.; Moya, R.; Santana, S.; Carnes, J. Preclinical safety and immunological efficacy of Alternaria alternata polymerized extracts. Immunity, inflammation and disease 2018, 6, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Bona, D.; Albanesi, M.; Macchia, L. Is immunotherapy with fungal vaccines effective? Current opinion in allergy and clinical immunology 2019, 19, 646–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozek, A.; Pyrkosz, K. Immunotherapy of mold allergy: A review. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics 2017, 13, 2397–2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, M.F.; Postigo, I.; Tomaz, C.T.; Martinez, J. Alternaria alternata allergens: Markers of exposure, phylogeny and risk of fungi-induced respiratory allergy. Environment international 2016, 89-90, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abel-Fernández, E.; Martínez, M.J.; Galán, T.; Pineda, F. Going over Fungal Allergy: Alternaria alternata and Its Allergens. J Fungi (Basel) 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirkovic, T.D.; Bukilica, M.N.; Gavrovic, M.D.; Vujcic, Z.M.; Petrovic, S.; Jankov, R.M. Physicochemical and immunologic characterization of low-molecular-weight allergoids of Dactylis glomerata pollen proteins. Allergy 1999, 54, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahler, H.; Stuwe, H.; Cromwell, O.; Fiebig, H. Reactivity of T cells with grass pollen allergen extract and allergoid. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 1999, 120, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Matas, M.A.; Gallego, M.; Iraola, V.; Robinson, D.; Carnés, J. Depigmented allergoids reveal new epitopes with capacity to induce IgG blocking antibodies. BioMed research international 2013, 2013, 284615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Starchenka, S.; Bell, A.J.; Mwange, J.; Skinner, M.A.; Heath, M.D. Molecular fingerprinting of complex grass allergoids: Size assessments reveal new insights in epitope repertoires and functional capacities. World Allergy Organ J 2017, 10, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamji, M.H.; Francis, J.N.; Würtzen, P.A.; Lund, K.; Durham, S.R.; Till, S.J. Cell-free detection of allergen-IgE cross-linking with immobilized phase CD23: Inhibition by blocking antibody responses after immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2013, 132, 1003–1005.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reithofer, M.; Böll, S.L.; Kitzmüller, C.; Horak, F.; Sotoudeh, M.; Bohle, B.; Jahn-Schmid, B. Alum-adjuvanted allergoids induce functional IgE-blocking antibodies. 2018, 48, 741–744. [CrossRef]

- Rauber, M.M.; Wu, H.K.; Adams, B.; Pickert, J.; Bohle, B. Birch pollen allergen-specific immunotherapy with glutaraldehyde-modified allergoid induces IL-10 secretion and protective antibody responses. 2019, 74, 1575–1579. [CrossRef]

- Abel-Fernández, E.; Fernández-Caldas, E. Allergy to fungi: Advances in the understanding of fungal allergens. Mol Immunol 2023, 163, 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armentia, A.; Martín-Armentia, S.; Moral, A.; Montejo, D.; Martin-Armentia, B.; Sastre, R.; Fernández, S.; Corell, A.; Fernandez, D. Molecular study of hypersensitivity to spores in adults and children from Castile & Leon. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr) 2019, 47, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, D.; Tabar, A.I.; Castillo, M.; Martínez-Gomariz, M.; Dobski, I.C.; Palacios, R. Changes in the Sensitization Pattern to Alternaria alternata Allergens in Patients Treated with Alt a 1 Immunotherapy. J Fungi (Basel) 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celakovska, J.; Vankova, R.; Bukac, J.; Cermakova, E.; Andrys, C.; Krejsek, J. Atopic Dermatitis and Sensitisation to Molecular Components of Alternaria, Cladosporium, Penicillium, Aspergillus, and Malassezia—Results of Allergy Explorer ALEX 2. Journal of Fungi 2021, 7, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, H.S.; Ikle, D.; Buchmeier, A. Studies of allergen extract stability: The effects of dilution and mixing. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology 1996, 98, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grier, T.J.; LeFevre, D.M.; Duncan, E.A.; Esch, R.E. Stability of standardized grass, dust mite, cat, and short ragweed allergens after mixing with mold or cockroach extracts. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. Off. Publ. Am. Coll. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2007, 99, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esch, R.E. Allergen immunotherapy: What can and cannot be mixed? The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology 2008, 122, 659–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coop, C.A. Immunotherapy for mold allergy. Clinical reviews in allergy and immunology 2014, 47, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kordash, T.R.; Amend, M.J.; Williamson, S.L.; Jones, J.K.; Plunkett, G.A. Effect of mixing allergenic extracts containing Helminthosporium, D. farinae, and cockroach with perennial ryegrass. Annals of allergy 1993, 71, 240–246. [Google Scholar]

| ENZYMATIC ACTIVITY | NATIVE EXTRACT |

| Alkaline phosphatase | + |

| Esterase (C4) | + |

| Esterase lipase (C8) | + |

| Lipase (C14) | - |

| Leucine arylamidase | + |

| Valine arylamidase | - |

| Cystine arylamidase | - |

| Trypsin | + |

| α-chymotrypsin | - |

| Acid phosphatase | + |

| Naphthol AS-BI-phosphohydrolase | + |

| α-galactosidase | + |

| β -galactosidase | + |

| β-glucuronidase | - |

| α-glucosidase | + |

| β-glucosidase | + |

| N-acetyl-β-glucosaminidase | + |

| β-mannosidase | + |

| α-fucosidase | - |

| PROTEOLYTIC ACTIVITY | NATIVE EXTRACT | POLYMERISED EXTRACT | % DIMINUTION |

| Trypsin | 119.049 | 0.321 | 99.73 |

| Serine protease | 6172.52 | 614.03 | 90.05 |

| Cysteine protease | 3.55 | 1.45 | 59.15 |

| Acid phosphatase | 98.62 | 28.27 | 71.33 |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 543.86 | 134.80 | 75.21 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).