1. Introduction

ChatGPT is a large-scale language artificial intelligence (AI) model with 175 billion parameters, released in November 2022 by OpenAI [

1]. Built on the natural language processing (NLP) technology called “generative pre-trained transformer” (GPT), ChatGPT generates conversational text responses to a given input. Its potential applications in healthcare have gained traction in recent years, with examples emerging in neuromodulation and pain management [

2,

3,

4].

Notably, NLP-based tools like ChatGPT have shown promise in addressing patient queries across various medical specialties, offering innovative ways to communicate complex information and enhance patient understanding [

5]. However, the areas of application, potential use cases, and limitations remain topics of ongoing debate [

6,

7].

Spinal cord stimulation (SCS) is an advanced neuromodulation therapy widely used to manage chronic pain conditions that have not responded to more conservative therapies. Commonly utilized for conditions such as failed back surgery syndrome, complex regional pain syndrome, and other conditions of neuropathic pain, spinal cord stimulation aims to provide significant pain relief and improve quality of life [

8]. Nevertheless, despite its effectiveness for some patients, it requires careful patient selection, as not everyone may benefit from the procedure. Additionally, many patients have concerns and questions about treatment, trialing, system implantation, and long-term management [

9]. Consequently, providing clear, accurate, and comprehensible information can alleviate these concerns, fostering informed decision-making and treatment confidence [

10,

11]. In this context, AI-based tools can be employed as supplementary resources for patient education, with the potential to deliver accessible, reliable, and consistent information.

This study aimed to evaluate the reliability, accuracy, and comprehensibility of ChatGPT’s responses to common questions about SCS, addressing a critical need for high-quality patient education in chronic pain management. Specifically, we investigated the feasibility of the chatbot to address patient concerns and improve comprehension of a complex medical procedure.

2. Materials and Methods

Study Objectives

This study evaluated the reliability, accuracy, and comprehensibility of ChatGPT’s responses to common patient questions about SCS. A secondary objective was to assess the potential utility of ChatGPT in improving patient understanding and acceptance of SCS by addressing frequently asked questions across pre-procedural, intra-procedural, and post-procedural domains.

Query Strategy

Thirteen of the most common patient questions regarding SCS implants were identified based on clinical expertise, literature review [

12], and on-line sources [

13]. These questions, detailed in

Table 1, were categorized into three domains: pre-procedural (questions 1–2), intra-procedural (questions 3–4), and post-procedural (questions 5–13). Each question was submitted to GPT 4.0 on July 25, 2024, using the prelude: “

If you were a physician, how would you answer a patient asking…” The AI-generated responses were recorded for evaluation. Consequently, an in-depth review process was implemented to ensure coverage of clinical nuances and patient-specific scenarios in AI-generated responses.

Evaluation Process

The responses were assessed by a panel of 12 participants, including 10 interventional chronic pain physicians with expertise in SCS and 2 non-healthcare professionals experienced in patient education for chronic pain management. The addition of feedback from non-healthcare participants provided insights into the readability and accessibility of the information, ensuring the study captured diverse perspectives.

Each participant independently evaluated the responses using a Likert scale across three dimensions: reliability (1–6 points), accuracy (1–3 points), and comprehensibility (1–3 points). Reliability was defined as the consistency and trustworthiness of the responses, accuracy as alignment with current medical knowledge on SCS, and comprehensibility as the clarity and ease of understanding for patients. Responses were deemed acceptable if they scored at least 4 points for reliability, 2 points for accuracy, and 3 points for comprehensibility, consistent with the cutoff criteria used in prior studies evaluating similar constructs.

Statistical Analysis

Quantitative data were expressed as means with standard deviations (SD). Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS v. 26 software to evaluate agreement among participant ratings and identify patterns in ChatGPT’s performance. The study was exempt from the Institutional Review Board review as no patient-related data was involved.

3. Results

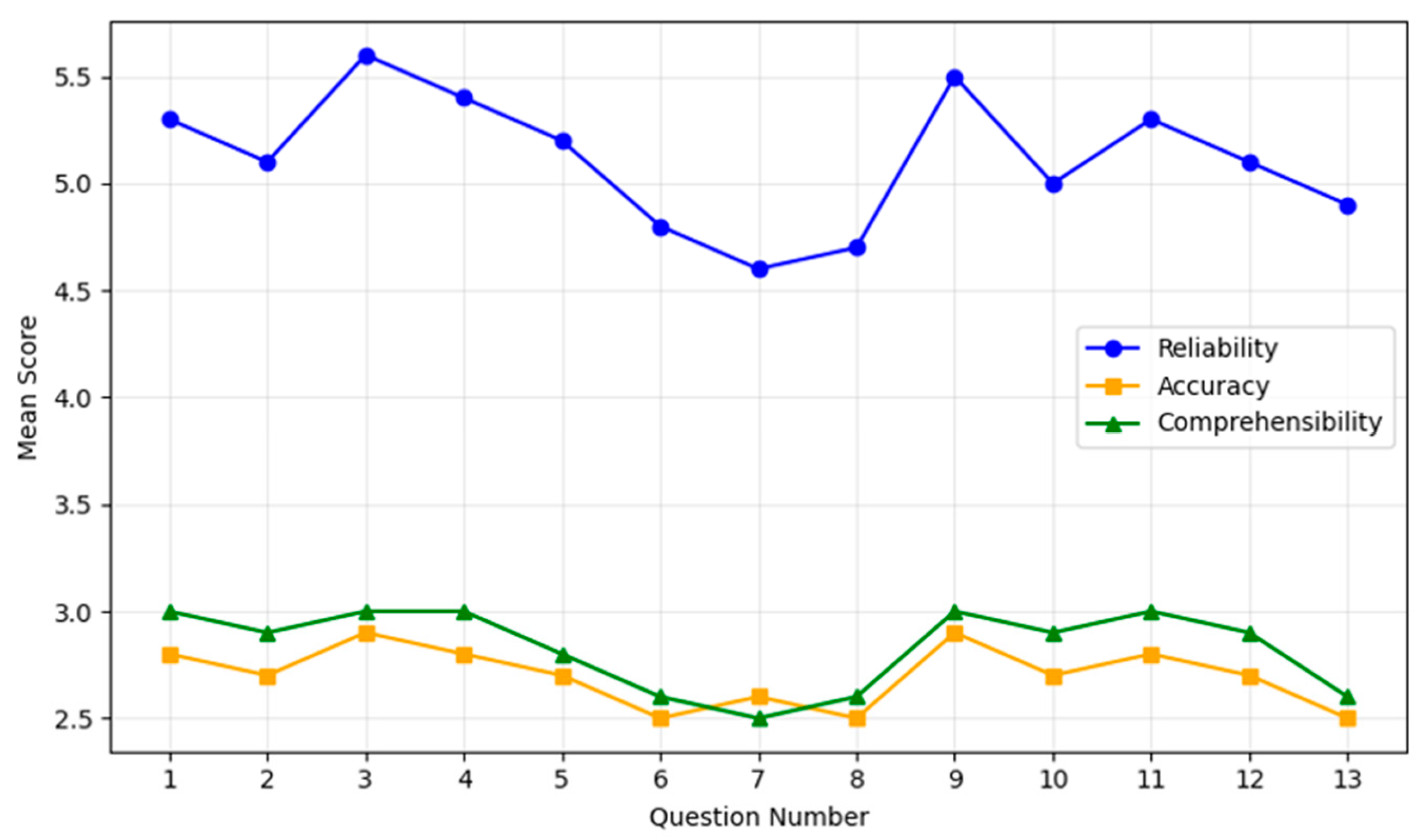

The overall mean reliability of ChatGPT’s responses was 5.1 ± 0.7, with 92% of responses scoring ≥4 (

Table 2). Q7 and Q12 received slightly lower reliability scores of 4.6 ± 0.8 and 4.8 ± 0.9, respectively, while Q3 and Q9 achieved the highest ratings, with mean scores of 5.6 ± 0.5 and 5.5 ± 0.5.

The overall mean accuracy was 2.7 ± 0.3, with 95% of the responses rated as sufficiently accurate (≥2). Q5 and Q11 scored the highest for accuracy at 2.9 ± 0.1, whereas Q10 and Q13 were rated lower, with scores of 2.5 ± 0.3 and 2.6 ± 0.4, respectively.

Comprehensibility was rated 2.8 ± 0.2 on average, with 98% of responses meeting or exceeding the threshold of ≥3. Q4 and Q9 achieved the highest comprehensibility scores of 3.0 ± 0.0, while Q13 received the lowest rating of 2.5 ± 0.4, with evaluators suggesting simpler language for improved clarity (

Figure 1).

These results highlight differences in performance between general and technical queries. Higher scores were observed for procedural and post-procedural questions, while responses to technical questions, such as those addressing waveform types and device troubleshooting, showed room for improvement (

Table 2).

4. Discussion

This study demonstrates ChatGPT’s capability to provide reliable and comprehensible answers to common patient questions regarding SCS. The high reliability (5.1 ± 0.7) and comprehensibility (2.8 ± 0.2) scores suggest that ChatGPT performs well in general patient education, particularly for procedural expectations and post-operative management. For example, its responses to questions like “What is spinal cord stimulation?” and “What are the risks and benefits?” were rated highly for clarity and alignment with clinical explanations. This underscores ChatGPT’s potential to distill complex medical information into accessible, patient-friendly language.

However, the model demonstrated limitations when addressing technical or context-specific topics, such as waveform types (Q7) and advanced troubleshooting (Q12), where scores were lower. This likely reflects ChatGPT’s reliance on publicly available general knowledge, which may not include detailed or nuanced medical content. These findings align with previous studies demonstrating that AI can perform well in general education but may fall short in handling specialized topics or adhering to rapidly evolving medical guidelines [

14,

15].

The challenges of integrating ChatGPT into clinical practice extend beyond its ability to provide accurate responses. The model’s training data may limit its relevance in fields like SCS, where advancements are frequent. Additionally, the model cannot provide culturally or linguistically tailored responses, which are essential for addressing the diverse needs of patient populations.

Notably, ethical and legal considerations, such as the risk of misinformation and ensuring accountability, must also be addressed before AI tools like ChatGPT can be widely adopted [

6,

16].

Despite these challenges, the results highlight ChatGPT’s promise as a supplementary tool for patient education. By simplifying medical concepts and addressing general patient concerns, AI models can enhance patient engagement and comprehension. To achieve broader utility, future iterations of ChatGPT and similar platforms should incorporate domain-specific training, regularly updated datasets, and improved adaptability for diverse clinical and cultural contexts.

4.1. Limitations

Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, the small sample size and the focus on responses generated by a single AI platform (ChatGPT 4.0) may limit the generalizability of the findings. While ChatGPT provides valuable insights, its capabilities cannot fully represent other AI models, such as Google Gemini (formerly Bard) or Microsoft Co-Pilot, which leverage related but distinct underlying technologies [

17]. Including comparisons across multiple platforms would provide a more comprehensive evaluation and reduce the risk of overgeneralizing findings from a single system.

Second, the surveyed participants were predominantly healthcare professionals affiliated with specific institutions, which may introduce bias and limit the applicability of the findings to broader or more diverse populations. Third, ChatGPT’s reliance on publicly available data, with a cutoff in September 2021, constrains its ability to address advancements in rapidly evolving fields like SCS. This limitation underscores the need for continuous updates to training datasets to ensure relevance in clinical practice.

Finally, the study did not assess patient perceptions directly, instead relying on evaluations by healthcare professionals and non-clinical participants. Future research should include patient-focused assessments to better understand the practical utility of AI-generated responses in real-world clinical settings.

4.2. Perspectives

Integrating AI tools like ChatGPT into standard clinical practice for spinal cord stimulation (SCS) and other interventional pain procedures holds significant promise. Nevertheless, to maximize its clinical utility, AI tools like ChatGPT should be regularly updated with domain-specific and regionally relevant data to ensure their accuracy and relevance in rapidly evolving fields like SCS.

Additionally, the inclusion of AI into clinical workflows must prioritize its role as an adjunct to healthcare professionals, who are essential for tailoring information to individual patient needs and navigating complex clinical scenarios. This human-in-the-loop process, where the algorithm implements human feedback to train the model for accurate prediction [18[, is mandatory for adapting AI outputs to cultural, linguistic, and individual patient needs.

Future efforts should focus on enhancing AI capabilities through domain-specific training, expanding datasets to reflect current knowledge, and validating their effectiveness in diverse patient populations. By complementing, rather than replacing, physician-patient interactions, AI-based tools have the potential to improve patient engagement, adherence, and outcomes in advanced therapies like SCS.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that ChatGPT has significant potential as a supplementary tool for patient education in SCS. Due to its reliable, accurate, and comprehensible responses to general queries highlight, the chatbot can be implemented to simplify complex medical information and support patient understanding. However, the AI’s limitations in addressing highly technical or context-specific topics and its reliance on an outdated knowledge base underscore the need for further refinement and validation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.L.; methodology, S.L.; software, E.S.; validation, M.D., G.L., and M.C.; formal analysis, G.L.; investigation, L.K.; resources, C.L.R.; data curation, M.C.; writing—original draft preparation, G.L.; writing—review and editing, E.S.; visualization, M.C.; supervision, E.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data collected and generated for this investigation are available from the first author (G.L).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SCS |

Spinal cord stimulation |

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| GPT |

generative pre-trained transformer |

References

- OpenAI. Introducing ChatGPT. November 30, 2022 (https://openai.com/blog/chatgpt).

- Lee TC, Staller K, Botoman V, Pathipati MP, Varma S, Kuo B. ChatGPT Answers Common Patient Questions About Colonoscopy. Gastroenterology. 2023;165(2):509-511.e7. [CrossRef]

- Robinson CL, D’Souza RS, Yazdi C, Diejomaoh EM, Schatman ME, Emerick T, Orhurhu V. Reviewing the Potential Role of Artificial Intelligence in Delivering Personalized and Interactive Pain Medicine Education for Chronic Pain Patients. J Pain Res. 2024 Mar 6;17:923-929.

- Slitzky M, Yong RJ, Bianco GL, Emerick T, Schatman ME, Robinson CL. The Future of Pain Medicine: Emerging Technologies, Treatments, and Education. J Pain Res. 2024 Aug 30;17:2833-2836. [CrossRef]

- Cascella M, Shariff MN, Lo Bianco G, Monaco F, Gargano F, Simonini A, Ponsiglione AM, Piazza O. Employing the Artificial Intelligence Object Detection Tool YOLOv8 for Real-Time Pain Detection: A Feasibility Study. J Pain Res. 2024 Nov 9;17:3681-3696. [CrossRef]

- Wang C, Liu S, Yang H, Guo J, Wu Y, Liu J. Ethical Considerations of Using ChatGPT in Health Care. J Med Internet Res. 2023 Aug 11;25:e48009. [CrossRef]

- Haltaufderheide J, Ranisch R. The ethics of ChatGPT in medicine and healthcare: a systematic review on Large Language Models (LLMs). NPJ Digit Med. 2024;7(1):183. [CrossRef]

- Lo Bianco G, Papa A, Gazzerro G, Rispoli M, Tammaro D, Di Dato MT, Vernuccio F, Schatman M. Dorsal Root Ganglion Stimulation for Chronic Postoperative Pain Following Thoracic Surgery: A Pilot Study. Neuromodulation. 2021;24(4):774-778. [CrossRef]

- Lo Bianco G, Tinnirello A, Papa A, Marchesini M, Day M, Palumbo GJ, Terranova G, Di Dato MT, Thomson SJ, Schatman ME. Interventional Pain Procedures: A Narrative Review Focusing On Safety and Complications. PART 2 Interventional Procedures For Back Pain. J Pain Res. 2023;16:761-772. [CrossRef]

- Renovanz M, Haaf J, Nesbigall R, Gutenberg A, Laubach W, Ringel F, Fischbeck S. Information needs of patients in spine surgery: development of a question prompt list to guide informed consent consultations. Spine J. 2019;19(3):523-531. [CrossRef]

- Everett CR, Novoseletsky D, Cole S, Frank J, Remillard C, Patel RK. Informed consent in interventional spine procedures: how much do patients understand? Pain Physician. 2005 Jul;8(3):251-5. Erratum in: Pain Physician. 2005 Oct;8(4):423.

- Witkam RL, Kurt E, van Dongen R, Arnts I, Steegers MAH, Vissers KCP, Henssen DJHA, Engels Y. Experiences From the Patient Perspective on Spinal Cord Stimulation for Failed Back Surgery Syndrome: A Qualitatively Driven Mixed Method Analysis. Neuromodulation. 2021;24(1):112-125. [CrossRef]

- Pain.com. Available at: https://www.pain.com/en/personal-support-resources/questions-and-answers.html. Last accessed: Dec 22, 2024.

- Boscardin CK, Gin B, Golde PB, Hauer KE. ChatGPT and Generative Artificial Intelligence for Medical Education: Potential Impact and Opportunity. Acad Med. 2024;99(1):22-27. [CrossRef]

- Preiksaitis C, Rose C. Opportunities, Challenges, and Future Directions of Generative Artificial Intelligence in Medical Education: Scoping Review. JMIR Med Educ. 2023;9:e48785. [CrossRef]

- Choudhury A, Chaudhry Z. Large Language Models and User Trust: Consequence of Self-Referential Learning Loop and the Deskilling of Health Care Professionals. J Med Internet Res. 2024 Apr 25;26:e56764. [CrossRef]

- Cascella M, Semeraro F, Montomoli J, Bellini V, Piazza O, Bignami E. The Breakthrough of Large Language Models Release for Medical Applications: 1-Year Timeline and Perspectives. J Med Syst. 2024;48(1):22. [CrossRef]

- Slade P, Atkeson C, Donelan JM, Houdijk H, Ingraham KA, Kim M, Kong K, Poggensee KL, Riener R, Steinert M, Zhang J, Collins SH. On human-in-the-loop optimization of human-robot interaction. Nature. 2024;633(8031):779-788. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).