Submitted:

14 January 2025

Posted:

15 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

- Group 1 PH: Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension (PAH).

- Group 2 PH: PH due to Left Heart Disease.

- Group 3 PH: PH due to lung diseases and/or hypoxia.

- Group 4 PH: PH due to Pulmonary artery obstructions.

- Group 5 PH: PH due to multifactorial mechanisms.

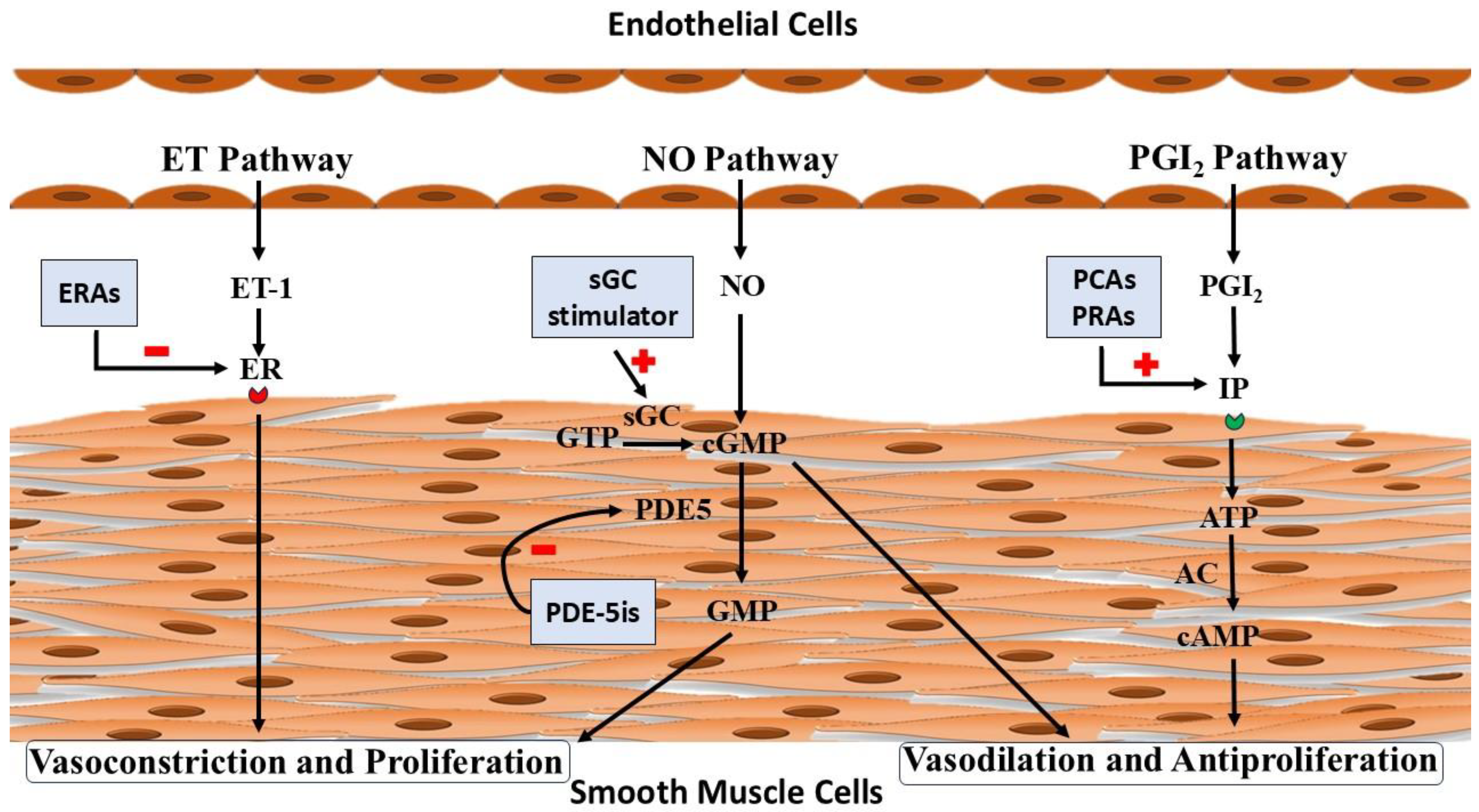

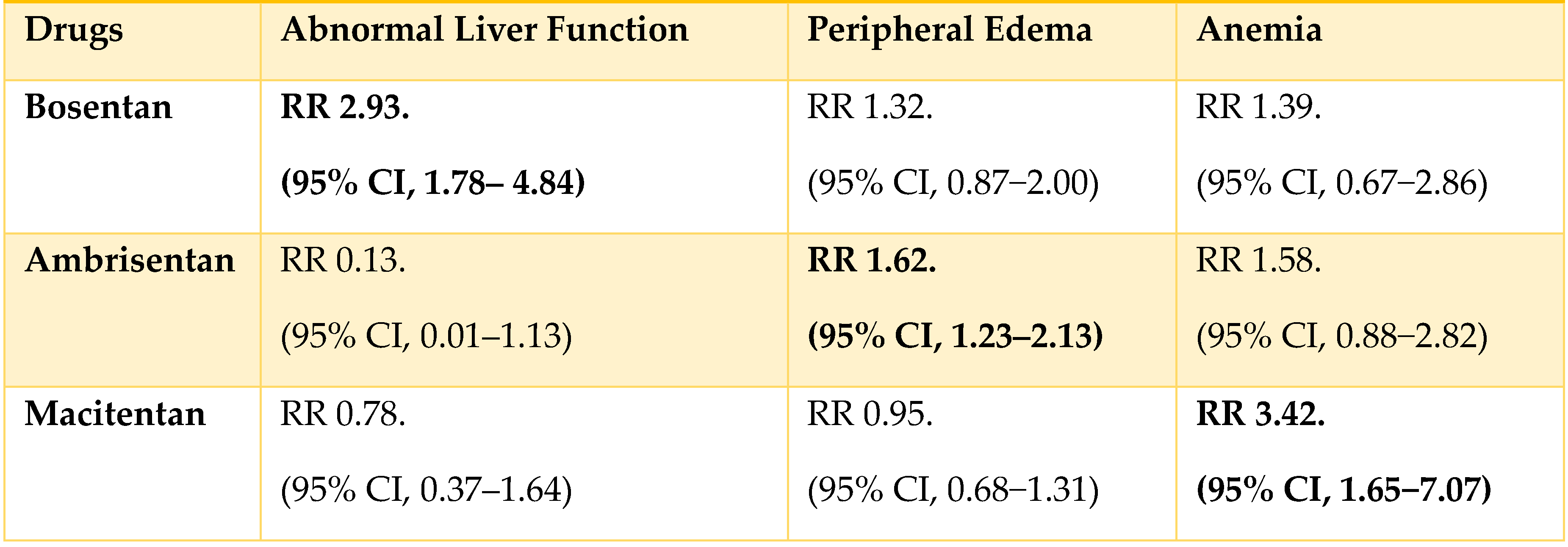

Endothelin Receptor Antagonists (ERAs):

Nitric Oxide-cyclic Guanosine Monophosphate (cGMP) Stimulators:

Phosphodiesterase-5 Inhibitors (PDE-5i):

Soluble Guanylate Cyclase (sGC) stimulator

Prostacyclin analogues and receptor agonists:

Fixed-Dose Combination Drug (Macitentan/Tadalafil)

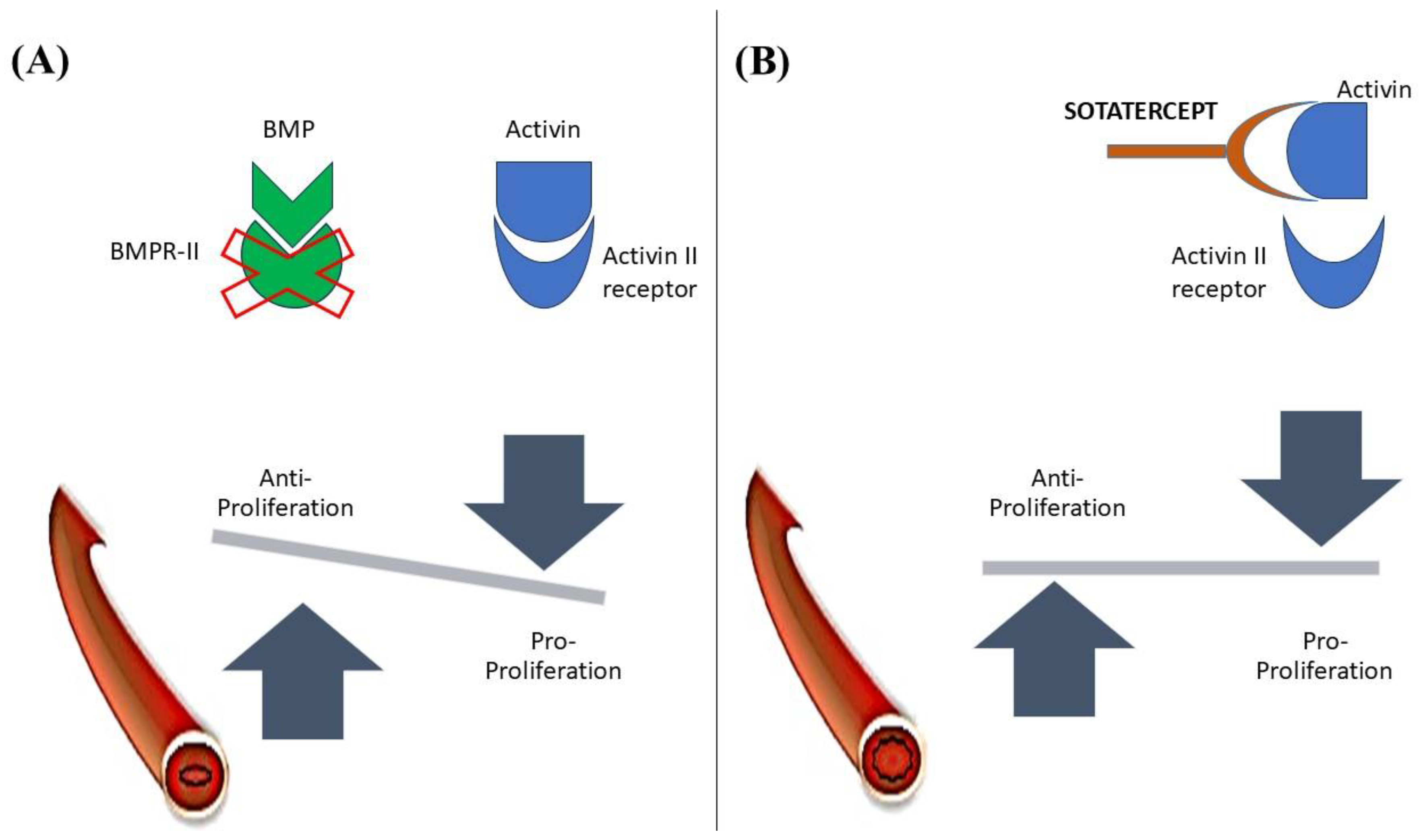

Activin signaling Inhibitor:

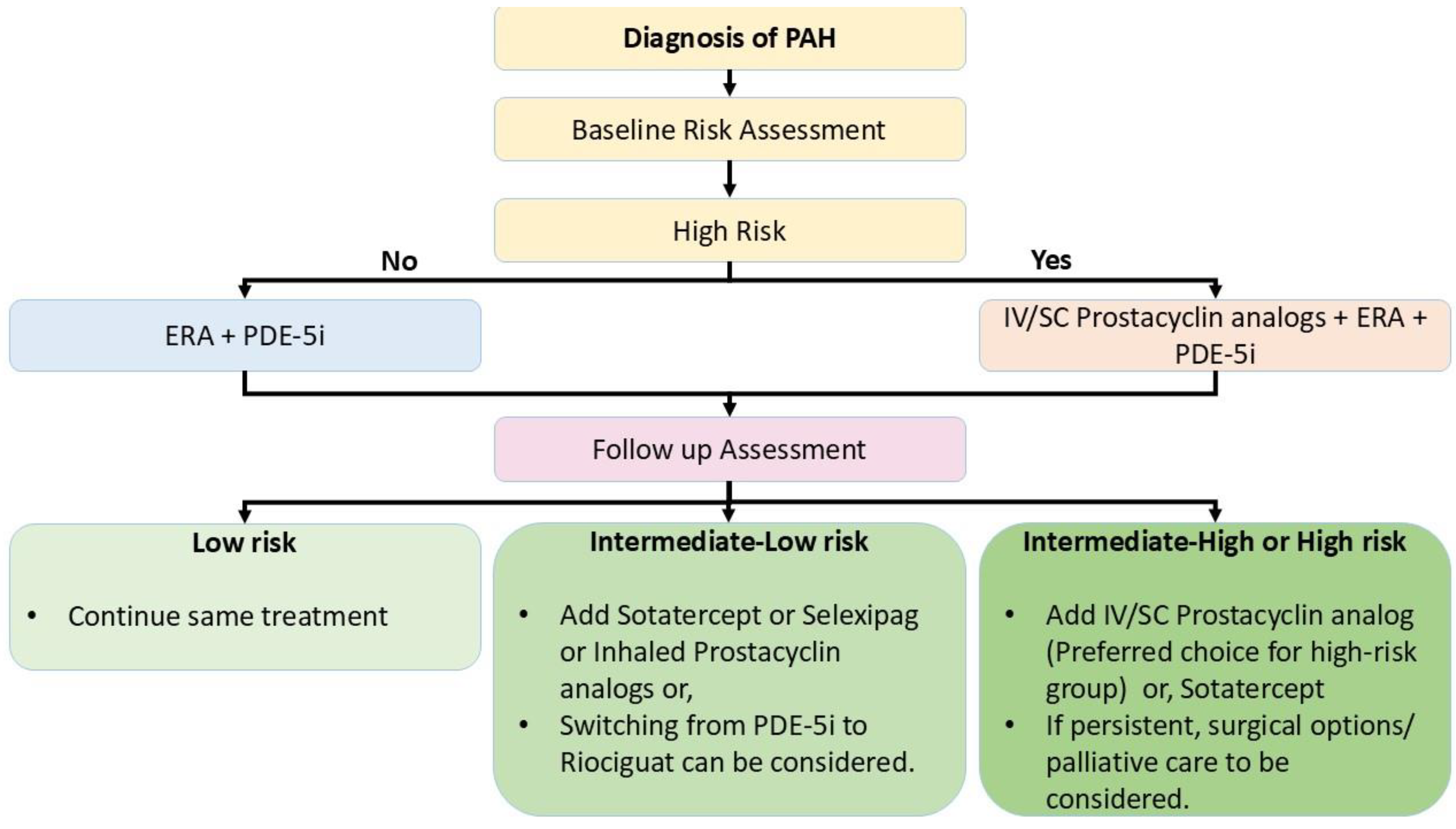

Treatment Algorithm

Surgical Strategies in Severe Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension (PAH):

Risk Assessment and Decision-Making for Treatment:

Surgical Strategies:

Right to Left Shunting:

Atrial Septostomy

Potts Shunt

Pulmonary artery denervation (PADN):

Thoracic Organ Transplantation:

Lung Transplantation

Heart-Lung Transplantation (HLT)

Decision-Making for Surgical Treatment[1,60,61]:

Emerging Surgical Strategies:

Hybrid Approaches

Mechanical Support Devices

Precision Medicine in Surgical PAH Management

Palliative care: An overlooked extra panel of support for PAH therapy:

What is on the Horizon?

Regenerative Medicine: A potential curative approach for a patient with PAH

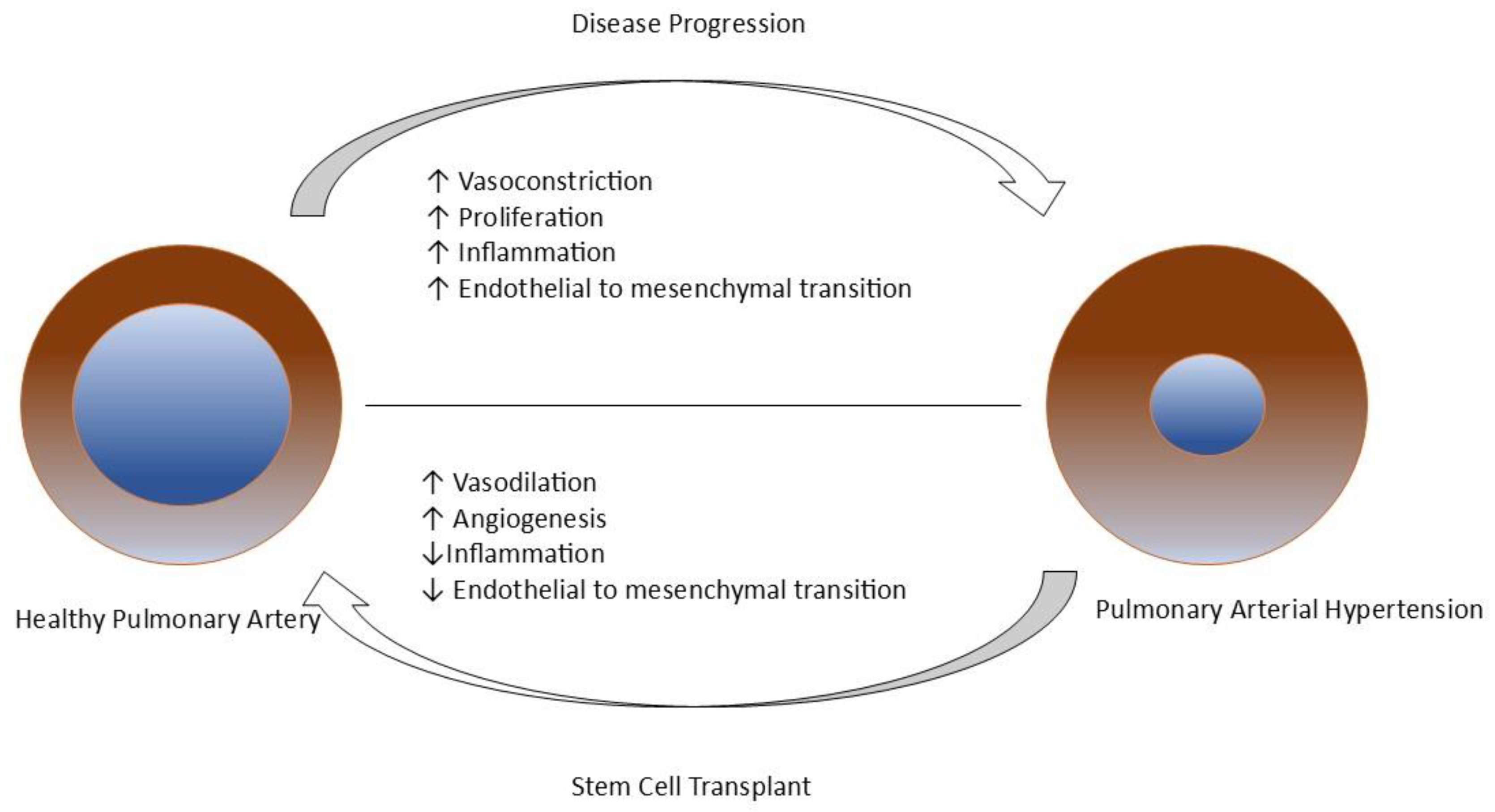

Stem Cell Therapy

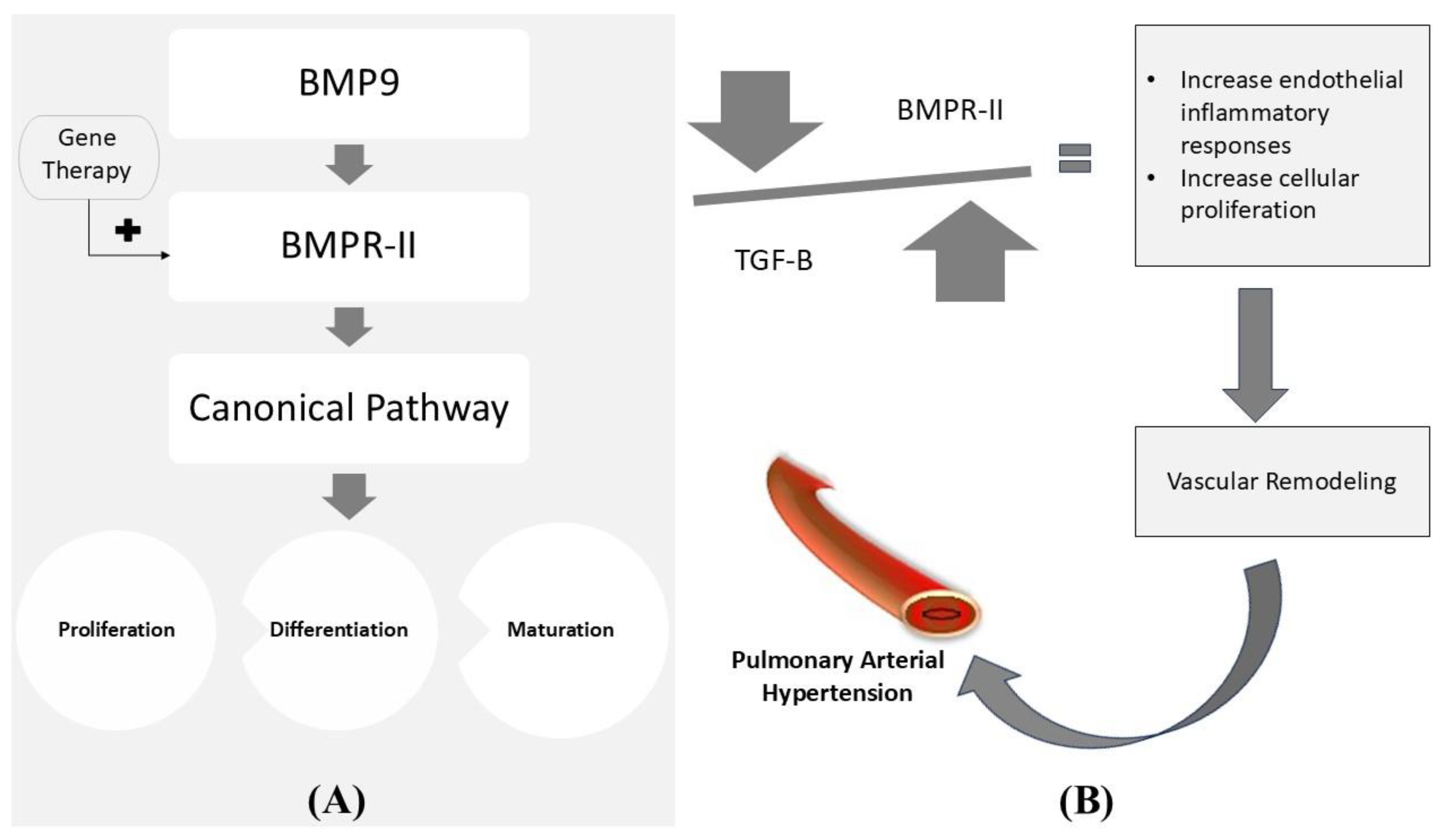

Gene Therapy

Epigenetic Medicines

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Humbert, M.; Kovacs, G.; Hoeper, M.M.; Badagliacca, R.; Berger, R.M.F.; Brida, M.; Carlsen, J.; Coats, A.J.; Escribano-Subias, P.; Ferrari, P.; et al. 2022 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Eur. Respir. J. 2023, 61, 2200879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonneau, G.; Montani, D.; Celermajer, D.S.; Denton, C.P.; Gatzoulis, M.A.; Krowka, M.; Williams, P.G.; Souza, R. Haemodynamic definitions and updated clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension. Eur. Respir. J. 2019, 53, 1801913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wijeratne, D.T.; Lajkosz, K.; Brogly, S.B.; Lougheed, M.D.; Jiang, L.; Housin, A.; Barber, D.; Johnson, A.; Doliszny, K.M.; Archer, S.L. Increasing Incidence and Prevalence of World Health Organization Groups 1 to 4 Pulmonary Hypertension: A Population-Based Cohort Study in Ontario, Canada. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual Outcomes 2018, 11, e003973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D'Alonzo, G.E.; Barst, R.J.; Ayres, S.M.; Bergofsky, E.H.; Brundage, B.H.; Detre, K.M.; Fishman, A.P.; Goldring, R.M.; Groves, B.M.; Kernis, J.T.; et al. Survival in patients with primary pulmonary hypertension. Results from a national prospective registry. Ann. Intern. Med. 1991, 115, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGoon, M.D.; Miller, D.P. REVEAL: A contemporary US pulmonary arterial hypertension registry. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2012, 21, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humbert, M.; Sitbon, O.; Chaouat, A.; Bertocchi, M.; Habib, G.; Gressin, V.; Yaici, A.; Weitzenblum, E.; Cordier, J.F.; Chabot, F.; et al. Pulmonary arterial hypertension in France: Results from a national registry. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2006, 173, 1023–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietra, G.G.; Capron, F.; Stewart, S.; Leone, O.; Humbert, M.; Robbins, I.M.; Reid, L.M.; Tuder, R. Pathologic assessment of vasculopathies in pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004, 43, S25–S32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lüscher, T.F.; Barton, M. Endothelins and Endothelin Receptor Antagonists: Therapeutic Considerations for a Novel Class of Cardiovascular Drugs. Circulation 2000, 102, 2434–2440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hynynen, M.M.; Khalil, R.A. The Vascular Endothelin System in Hypertension - Recent Patents and Discoveries. Recent Patents Cardiovasc. Drug Discov. 2006, 1, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clozel, M.; Breu, V.; A Gray, G.; Kalina, B.; Löffler, B.M.; Burri, K.; Cassal, J.M.; Hirth, G.; Müller, M.; Neidhart, W. Pharmacological characterization of bosentan, a new potent orally active nonpeptide endothelin receptor antagonist. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1994, 270, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingman, M.; Ruggiero, R.; Torres, F. Ambrisentan, an endothelin receptor type A-selective endothelin receptor antagonist, for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2009, 10, 1847–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolli, M.H.; Boss, C.; Binkert, C.; Buchmann, S.; Bur, D.; Hess, P.; et al. The Discovery of N -[5-(4-Bromophenyl)-6-[2-[(5-bromo-2-pyrimidinyl)oxy]ethoxy]-4-pyrimidinyl]- N ′-propylsulfamide (Macitentan), an Orally Active, Potent Dual Endothelin Receptor Antagonist. J Med Chem. 2012, 55, 7849–7861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, L.J.; Badesch, D.B.; Barst, R.J.; Galiè, N.; Black, C.M.; Keogh, A.; Pulido, T.; Frost, A.; Roux, S.; Leconte, I.; et al. Bosentan Therapy for Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 346, 896–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Lebron, B.N.; Risbano, M.G. Ambrisentan: A review of its use in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Ther. Adv. Respir. Dis. 2017, 11, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galiè, N.; Olschewski, H.; Oudiz, R.J.; Torres, F.; Frost, A.; Ghofrani, H.A.; et al. Ambrisentan for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension: Results of the ambrisentan in pulmonary arterial hypertension, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter, efficacy (ARIES) study 1 and 2. Circulation 2008, 117, 3010–3019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pulido, T.; Adzerikho, I.; Channick, R.N.; Delcroix, M.; Galiè, N.; Ghofrani, A.; Jansa, P.; Jing, Z.-C.; Le Brun, F.-O.; Mehta, S.; et al. Macitentan and Morbidity and Mortality in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 809–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-J.; Wang, N.; Gu, Z.-C.; Wei, A.-H.; Cheng, A.-N.; Fang, S.-S.; Du, H.-L.; Wang, L.-Z.; Zhang, G.-Q. A network meta-analysis for safety of endothelin receptor antagonists in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Cardiovasc. Diagn. Ther. 2019, 9, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Förstermann, U.; Sessa, W.C. Nitric oxide synthases: Regulation and function. Eur. Heart J. 2012, 33, 829–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wharton, J.; Strange, J.W.; Møller, G.M.O.; Growcott, E.J.; Ren, X.; Franklyn, A.P.; Phillips, S.C.; Wilkins, M.R. Antiproliferative Effects of Phosphodiesterase Type 5 Inhibition in Human Pulmonary Artery Cells. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2005, 172, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galiè, N.; Ghofrani, H.A.; Torbicki, A.; Barst, R.J.; Rubin, L.J.; Badesch, D.; Fleming, T.; Parpia, T.; Burgess, G.; Branzi, A.; et al. Sildenafil Citrate Therapy for Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 353, 2148–2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, L.J.; Badesch, D.B.; Fleming, T.R.; Galiè, N.; Simonneau, G.; Ghofrani, H.A.; et al. Long-term treatment with sildenafil citrate in pulmonary arterial hypertension: The SUPER-2 study. Chest 2011, 140, 1274–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galie, N.; Brundage, B.H.; Ghofrani, H.A.; Oudiz, R.J.; Simonneau, G.; Safdar, Z.; Shapiro, S.; White, R.J.; Chan, M.; Beardsworth, A.; et al. Tadalafil Therapy for Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Circulation 2009, 119, 2894–2903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrishko, R.E.; Dingemanse, J.; Yu, A.; Darstein, C.; Phillips, D.L.; Mitchell, M.I. Pharmacokinetic interaction between tadalafil and bosentan in healthy male subjects. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2008, 48, 610–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oudiz, R.J.; Brundage, B.H.; Galiè, N.; Ghofrani, H.A.; Simonneau, G.; Botros, F.T.; Chan, M.; Beardsworth, A.; Barst, R.J. Tadalafil for the Treatment of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2012, 60, 768–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, H.; Brown, Z.; Burns, A.; Williams, T. Phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors for pulmonary hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019, 1, CD012621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghofrani, H.; Hoeper, M.; Halank, M.; Meyer, F.; Staehler, G.; Behr, J.; Ewert, R.; Weimann, G.; Grimminger, F. Riociguat for chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension and pulmonary arterial hypertension: A phase II study. Eur. Respir. J. 2010, 36, 792–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghofrani, H.-A.; Galiè, N.; Grimminger, F.; Grünig, E.; Humbert, M.; Jing, Z.-C.; Keogh, A.M.; Langleben, D.; Kilama, M.O.; Fritsch, A.; et al. Riociguat for the Treatment of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 330–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubin, L.J.; Galiè, N.; Grimminger, F.; Grünig, E.; Humbert, M.; Jing, Z.-C.; Keogh, A.; Langleben, D.; Fritsch, A.; Menezes, F.; et al. Riociguat for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension: A long-term extension study (PATENT-2). Eur. Respir. J. 2015, 45, 1303–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghofrani, H.-A.; Grimminger, F.; Grünig, E.; Huang, Y.; Jansa, P.; Jing, Z.-C.; Kilpatrick, D.; Langleben, D.; Rosenkranz, S.; Menezes, F.; et al. Predictors of long-term outcomes in patients treated with riociguat for pulmonary arterial hypertension: Data from the PATENT-2 open-label, randomised, long-term extension trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 2016, 4, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majed, B.H.; Khalil, R.A. Molecular Mechanisms Regulating the Vascular Prostacyclin Pathways and Their Adaptation during Pregnancy and in the Newborn. Pharmacol. Rev. 2012, 64, 540–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuder, R.M.; Cool, C.D.; Geraci, M.W.; Wang, J.; Abman, S.H.; Wright, L.; Badesch, D.; Voelkel, N.F. Prostacyclin Synthase Expression Is Decreased in Lungs from Patients with Severe Pulmonary Hypertension. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1999, 159, 1925–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomberg-Maitland, M.; Olschewski, H. Prostacyclin therapies for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur. Respir. J. 2008, 31, 891–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubin, L.J. Treatment of Primary Pulmonary Hypertension with Continuous Intravenous Prostacyclin (Epoprostenol): Results of a Randomized Trial. Ann Intern Med. 1990, 112, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barst, R.J.; Rubin, L.J.; Long, W.A.; McGoon, M.D.; Rich, S.; Badesch, D.B.; Groves, B.M.; Tapson, V.F.; Bourge, R.C.; Brundage, B.H.; et al. A Comparison of Continuous Intravenous Epoprostenol (Prostacyclin) with Conventional Therapy for Primary Pulmonary Hypertension. N. Engl. J. Med. 1996, 334, 296–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLaughlin, V.V.; Shillington, A.; Rich, S. Survival in primary pulmonary hypertension: The impact of epoprostenol therapy. Circulation. 2002, 106, 1477–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitbon, O.; Humbert, M.; Nunes, H.; Parent, F.; Garcia, G.; Hervé, P.; et al. Long-term intravenous epoprostenol infusion in primary pulmonary hypertension: Prognostic factors and survival. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002, 40, 780–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simonneau, G.; Barst, R.J.; Galie, N.; Naeije, R.; Rich, S.; Bourge, R.C.; et al. Continuous subcutaneous infusion of treprostinil, a prostacyclin analogue, in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002, 165, 800–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, I.; Gomez-Sanchez, M.; Kneussl, M.; Naeije, R.; Escribano, P.; Skoro-Sajer, N.; Vachiery, J.-L. Efficacy of Long-term Subcutaneous Treprostinil Sodium Therapy in Pulmonary Hypertension. Chest 2006, 129, 1636–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tapson, V.F.; Gomberg-Maitland, M.; McLaughlin, V.V.; Benza, R.L.; Widlitz, A.C.; Krichman, A.; et al. Safety and efficacy of IV treprostinil for pulmonary arterial hypertension: A prospective, multicenter, open-label, 12-week trial. Chest 2006, 129, 683–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomberg-Maitland, M.; Tapson, V.F.; Benza, R.L.; McLaughlin, V.V.; Krichman, A.; Widlitz, A.C.; Barst, R.J. Transition from Intravenous Epoprostenol to Intravenous Treprostinil in Pulmonary Hypertension. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2005, 172, 1586–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, V.V.; Benza, R.L.; Rubin, L.J.; Channick, R.N.; Voswinckel, R.; Tapson, V.F.; et al. Addition of inhaled treprostinil to oral therapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension: A randomized controlled clinical trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010, 55, 1915–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spikes, L.A.; Bajwa, A.A.; Burger, C.D.; Desai, S.V.; Eggert, M.S.; El-Kersh, K.A.; et al. BREEZE: Open-label clinical study to evaluate the safety and tolerability of treprostinil inhalation powder as Tyvaso DPITM in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Pulm circ. 2022, 12, e12063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, N.; Smoot, K.; Patzlaff, N.; Miceli, M.; Waxman, A. Plain Language Summary of the INCREASE Study: Inhaled Treprostinil (Tyvaso) for the Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension Due to Interstitial Lung Disease. Futur. Cardiol. 2023, 19, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, A.; Smith, J.; Qureshi, M.R.; Uysal, A.; Patel, K.K.; Herazo-Maya, J.D.; et al. Evolution of pulmonary hypertension in interstitial lung disease: A journey through past, present, and future. Front Med (Lausanne) 2023, 10, 1306032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olschewski, H.; Simonneau, G.; Galiè, N.; Higenbottam, T.; Naeije, R.; Rubin, L.J.; et al. Inhaled Iloprost for Severe Pulmonary Hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2002, 347, 322–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLaughlin, V.V.; Oudiz, R.J.; Frost, A.; Tapson, V.F.; Murali, S.; Channick, R.N.; et al. Randomized study of adding inhaled iloprost to existing bosentan in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006, 174, 1257–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simonneau, G.; Torbicki, A.; Hoeper, M.M.; Delcroix, M.; Karlócai, K.; Galiè, N.; Degano, B.; Bonderman, D.; Kurzyna, M.; Efficace, M.; et al. Selexipag: An oral, selective prostacyclin receptor agonist for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur. Respir. J. 2012, 40, 874–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sitbon, O.; Channick, R.; Chin, K.M.; Frey, A.; Gaine, S.; Galiè, N.; Ghofrani, H.-A.; Hoeper, M.M.; Lang, I.M.; Preiss, R.; et al. Selexipag for the Treatment of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 2522–2533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galiè, N.; Barberà, J.A.; Frost, A.E.; Ghofrani, H.-A.; Hoeper, M.M.; McLaughlin, V.V.; Peacock, A.J.; Simonneau, G.; Vachiery, J.-L.; Grünig, E.; et al. Initial Use of Ambrisentan plus Tadalafil in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 834–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grünig, E.; Jansa, P.; Fan, F.; Hauser, J.A.; Pannaux, M.; Morganti, A.; Rofael, H.; Chin, K.M. Randomized Trial of Macitentan/Tadalafil Single-Tablet Combination Therapy for Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2024, 83, 473–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massagué, J. TGF-beta signal transduction. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998, 67, 753–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yndestad, A.; Larsen, K.-O.; Øie, E.; Ueland, T.; Smith, C.; Halvorsen, B.; Sjaastad, I.; Skjønsberg, O.H.; Pedersen, T.M.; Anfinsen, O.-G.; et al. Elevated levels of activin A in clinical and experimental pulmonary hypertension. J. Appl. Physiol. 2009, 106, 1356–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakaoka, T.; Gonda, K.; Ogita, T.; Otawara-Hamamoto, Y.; Okabe, F.; Kira, Y.; Harii, K.; Miyazono, K.; Takuwa, Y.; Fujita, T. Inhibition of rat vascular smooth muscle proliferation in vitro and in vivo by bone morphogenetic protein-2. J. Clin. Investig. 1997, 100, 2824–2832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkinson, C.; Stewart, S.; Upton, P.D.; Machado, R.; Thomson, J.R.; Trembath, R.C.; Morrell, N.W. Primary Pulmonary Hypertension Is Associated With Reduced Pulmonary Vascular Expression of Type II Bone Morphogenetic Protein Receptor. Circulation 2002, 105, 1672–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yung, L.-M.; Yang, P.; Joshi, S.; Augur, Z.M.; Kim, S.S.J.; Bocobo, G.A.; Dinter, T.; Troncone, L.; Chen, P.-S.; McNeil, M.E.; et al. ACTRIIA-Fc rebalances activin/GDF versus BMP signaling in pulmonary hypertension. Sci. Transl. Med. 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humbert, M.; McLaughlin, V.; Gibbs, J.S.R.; Gomberg-Maitland, M.; Hoeper, M.M.; Preston, I.R.; et al. Sotatercept for the Treatment of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2021, 384, 1204–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoeper, M.M.; Badesch, D.B.; Ghofrani, H.A.; Gibbs, J.S.R.; Gomberg-Maitland, M.; McLaughlin, V.V.; Preston, I.R.; Souza, R.; Waxman, A.B.; Grünig, E.; et al. Phase 3 Trial of Sotatercept for Treatment of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 1478–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasrollahizadeh, A.; Soleimani, H.; Nasrollahizadeh, A.; Hashemi, S.M.; Hosseini, K. Navigating the Sotatercept landscape: A meta-analysis of clinical outcomes. Clin Cardiol. 2024, 47, e24173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, K.M.; Gaine, S.P.; Gerges, C.; Jing, Z.-C.; Mathai, S.C.; Tamura, Y.; McLaughlin, V.V.; Sitbon, O. Treatment algorithm for pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur. Respir. J. 2024, 64, 2401325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stącel, T.; Latos, M.; Urlik, M.; Nęcki, M.; Antończyk, R.; Hrapkowicz, T.; Kurzyna, M.; Ochman, M. Interventional and Surgical Treatments for Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 3326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keogh, A.M.; Mayer, E.; Benza, R.L.; Corris, P.; Dartevelle, P.G.; Frost, A.E.; Kim, N.H.; Lang, I.M.; Pepke-Zaba, J.; Sandoval, J. Interventional and Surgical Modalities of Treatment in Pulmonary Hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009, 54, S67–S77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zebadua, R.; Zayas, N.; Lopez, J.; Zorrilla, L.; Pozas, M.; Villalobos, M.; et al. Survival of patients diagnosed with Pulmonary Hypertension undergoing Atrial Septostomy. In: 1301 - Pulmonary hypertension [Internet]. European Respiratory Society; 2022 [cited 2025 Jan 8]. p. 4186. Available online: http://publications.ersnet.org/lookup/doi/10.1183/13993003.congress-2022.4186.

- Baruteau, A.-E.; Serraf, A.; Lévy, M.; Petit, J.; Bonnet, D.; Jais, X.; Vouhé, P.; Simonneau, G.; Belli, E.; Humbert, M. Potts Shunt in Children With Idiopathic Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension: Long-Term Results. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2012, 94, 817–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, C.; Yang, Z.; Kan, J.; Gu, H.; et al. Pulmonary Artery Denervation for Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension: A Sham-Controlled Randomized PADN-CFDA Trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2022, 15, 2412–2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otto, M.; McGiffin, D.; Whitford, H.; Kure, C.; Snell, G.; Diehl, A.; Orosz, J.; Burrell, A.J. Survival and left ventricular dysfunction post lung transplantation for pulmonary arterial hypertension. J. Crit. Care 2022, 72, 154120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecker, F.; Keller, H.; Vasa-Nicotera, M.; Iken, S.; Holubec, T. Percutaneous dual-outflow extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support in secondary right ventricular failure. JTCVS Tech. 2022, 13, 125–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leopold, J.A.; Maron, B.A. Precision Medicine in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Circ. Res. 2019, 124, 832–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benincasa, G.; DeMeo, D.L.; Glass, K.; Silverman, E.K.; Napoli, C. Epigenetics and pulmonary diseases in the horizon of precision medicine: A review. Eur Respir J. 2021, 57, 2003406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khirfan, G.; Tonelli, A.R.; Ramsey, J.; Sahay, S. Palliative care in pulmonary arterial hypertension: An underutilised treatment. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2018, 27, 180069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiansen, D.; Porter, S.; Hurlburt, L.; Weiss, A.; Granton, J.; Wentlandt, K. Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension: A Palliative Medicine Review of the Disease, Its Therapies, and Drug Interactions. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020, 59, 932–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loisel, F.; Provost, B.; Haddad, F.; Guihaire, J.; Amsallem, M.; Vrtovec, B.; et al. Stem cell therapy targeting the right ventricle in pulmonary arterial hypertension: Is it a potential avenue of therapy? Pulm Circ. 2018, 8, 2045893218755979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouwer, K.M.; Hoogenkamp, H.R.; Daamen, W.F.; van Kuppevelt, T.H. Regenerative medicine for the respiratory system: Distant future or tomorrow’s treatment? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013, 187, 468–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mason, C.; Dunnill, P. A Brief Definition of Regenerative Medicine. Regen. Med. 2008, 3, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissman, I.L. Stem cells: Units of development, units of regeneration, and units in evolution. Cell 2000, 100, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bisserier, M.; Pradhan, N.; Hadri, L. Current and emerging therapeutic approaches to pulmonary hypertension. Rev. Cardiovasc. Med. 2020, 21, 163–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaenisch, R.; Young, R. Stem Cells, the Molecular Circuitry of Pluripotency and Nuclear Reprogramming. Cell 2008, 132, 567–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dulak, J.; Szade, K.; Szade, A.; Nowak, W.; Józkowicz, A. Adult stem cells: Hopes and hypes of regenerative medicine. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2015, 62, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, R.; Xu, T.; Wang, X.; Yang, L.; Wang, J.; Huang, X. Stem cell therapy in pulmonary hypertension: Current practice and future opportunities. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2023, 32, 230112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, S.; Jung, J.-H.; Ahn, K.-J.; Jang, A.Y.; Byun, K.; Yang, P.C.; Chung, W.-J. Stem Cell and Exosome Therapy in Pulmonary Hypertension. Korean Circ. J. 2022, 52, 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, X.; Du, L.; Hu, Y.; Fan, Y.; Xu, Q. Stem/Progenitor Cells and Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2021, 41, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.W.; Sun, Z. Stem Cell Therapy for Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension: An Update. J. Hear. Lung Transplant. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dierick, F.; Solinc, J.; Bignard, J.; Soubrier, F.; Nadaud, S. Progenitor/Stem Cells in Vascular Remodeling during Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Cells 2021, 10, 1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.-X.; Pan, Y.-Y.; Zhao, Y.-Y.; Wang, X.-X. Endothelial Progenitor Cell-Based Therapy for Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Cell Transplant. 2013, 22, 1325–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaya, N.; Kangawa, K.; Kanda, M.; Uematsu, M.; Horio, T.; Fukuyama, N.; Hino, J.; Harada-Shiba, M.; Okumura, H.; Tabata, Y.; et al. Hybrid Cell–Gene Therapy for Pulmonary Hypertension Based on Phagocytosing Action of Endothelial Progenitor Cells. Circulation 2003, 108, 889–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.D.; Courtman, D.W.; Deng, Y.; Kugathasan, L.; Zhang, Q.; Stewart, D.J. Rescue of monocrotaline-induced pulmonary arterial hypertension using bone marrow-derived endothelial-like progenitor cells: Efficacy of combined cell and eNOS gene therapy in established disease. Circ Res. 2005, 96, 442–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granton, J.; Langleben, D.; Kutryk, M.B.; Camack, N.; Galipeau, J.; Courtman, D.W.; et al. Endothelial NO-Synthase Gene-Enhanced Progenitor Cell Therapy for Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension: The PHACeT Trial. Circulation Research. 2015, 117, 645–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.X.; Zhang, F.R.; Shang, Y.P.; Zhu, J.H.; Xie, X.D.; Tao, Q.M.; et al. Transplantation of Autologous Endothelial Progenitor Cells May Be Beneficial in Patients With Idiopathic Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2007, 49, 1566–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farkas, L.; Kolb, M. Vascular Repair and Regeneration as a Therapeutic Target for Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Respiration 2013, 85, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukumitsu, M.; Suzuki, K. Mesenchymal stem/stromal cell therapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension: Comprehensive review of preclinical studies. J. Cardiol. 2019, 74, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.-C.; Ke, M.-W.; Cheng, C.-C.; Chiou, S.-H.; Wann, S.-R.; Shu, C.-W.; Chiou, K.-R.; Tseng, C.-J.; Pan, H.-W.; Mar, G.-Y.; et al. Therapeutic Benefits of Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells in Monocrotaline-Induced Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0142476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicholson, M.W.; Ting, C.Y.; Chan, D.Z.H.; Cheng, Y.C.; Lee, Y.C.; Hsu, C.C.; et al. Utility of iPSC-Derived Cells for Disease Modeling, Drug Development, and Cell Therapy. Cells 2022, 11, 1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, G.A.R.; Paiva R de, M.A. Gene therapy: Advances, challenges and perspectives. Einstein (Sao Paulo). 2017, 15, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.-T.; Charng, M.-J.; Chi, P.-L.; Cheng, C.-C.; Hung, C.C.; Huang, W.-C. Gene Mutation Annotation and Pedigree for Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Patients in Han Chinese Patients. Glob. Hear. 2021, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fazal, S.; Bisserier, M.; Hadri, L. Molecular and Genetic Profiling for Precision Medicines in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Cells 2021, 10, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, A.M.; Holmes, M.D.; Danilov, S.M.; Reynolds, P.N. Targeted gene delivery of BMPR2 attenuates pulmonary hypertension. Eur. Respir. J. 2012, 39, 329–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, R.L.; Reynolds, A.M.; Bonder, C.S.; Reynolds, P.N. BMPR2 gene therapy for PAH acts via Smad and non-Smad signalling. Respirology 2016, 21, 727–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theilmann, A.L.; Hawke, L.G.; Hilton, L.R.; Whitford, M.K.; Cole, D.V.; Mackeil, J.L.; Dunham-Snary, K.J.; Mewburn, J.; James, P.D.; Maurice, D.H.; et al. Endothelial BMPR2 Loss Drives a Proliferative Response to BMP (Bone Morphogenetic Protein) 9 via Prolonged Canonical Signaling. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2020, 40, 2605–2618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Xu, G.; Yu, Y.; Lin, J. The role of TGF-β or BMPR2 signaling pathway-related miRNA in pulmonary arterial hypertension and systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2021, 23, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benincasa, G.; DeMeo, D.L.; Glass, K.; Silverman, E.K.; Napoli, C. Epigenetics and pulmonary diseases in the horizon of precision medicine: A review. Eur. Respir. J. 2021, 57, 2003406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dave, J.; Jagana, V.; Janostiak, R.; Bisserier, M. Unraveling the epigenetic landscape of pulmonary arterial hypertension: Implications for personalized medicine development. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napoli, C.; Benincasa, G.; Loscalzo, J. Epigenetic Inheritance Underlying Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2019, 39, 653–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinical trials.gov [Internet].

| Mean Pulmonary Artery Pressure (mPAP) | ≥ 20 mmHg |

| Pulmonary Arterial Wedge Pressure (PAWP) | ≤ 15 mmHg |

| Pulmonary Vascular Resistance (PVR) | ≥ 2 WU (Wood units) |

|

Idiopathic PAH (IPAH) Heritable PAH (HPAH) Drug and toxin induced PAH (DT-PAH) PAH associated with: Connective tissue disease (CTD) HIV infection Portal Hypertension Congenital Heart Disease (CHD) Schistosomiasis PAH long term responders to Calcium channel blockers PAH with overt features of venous/capillaries (PVOD/PCH) involvement. Persistent PH of the newborn syndrome. |

| M/T FDC | Macitentan | Treatment Effect | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reduction in PVR | 45% | 23% | 29% reduction |

| Geometric mean ratio of change in PVR | 0.55 (95% CI= 0.50-0.60) | 0.77 (95% CI= 0.69-0.87) | 0.71 (95% CI=0.61-0.82) |

| M/T FDC | Tadalafil | Treatment Effect | |

| Reduction in PVR | 44% | 22% | 28% reduction |

| Geometric mean ratio of change in PVR | 0.56(95% CI= 0.52-0.60) | 0.78 (95% CI= 0.72-0.84) | 0.72 (95% CI= 0.64-0.80) |

| Invasive therapy | Right to left shunting (AS, Potts shunt) Pulmonary artery denervation Others: RVAD, Right Ventricular Pacing, ECMO |

| Non-invasive therapy | Pain management Symptomatic treatment Treatment of underlying psychiatric disorders Specific therapy |

| Others | Counselling Financial assistance |

| Title | Primary Outcome Measures | Time Frame |

|---|---|---|

| Positioning Imatinib for Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension (PIPAH) | Identifying the highest tolerated doseChange in pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) | 12 months24 months |

| Clinical Trial of 2- hydroxbenzylamine (2-HOBA) in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension | Change in acetylated Superoxide Dismutase 2 (SOD2) and Long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (LCAD) in plasma. | Baseline and 12-weeks |

| Apabetalone for Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension (APPROACH-2) | Placebo-corrected change from baseline in PVR at week 24 | Baseline, and 24 weeks |

| Metabolic Remodeling in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension (PAH) | Change in ratio of oxidative metabolism to glycolysis | Baseline and 6 months |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).