Submitted:

14 January 2025

Posted:

14 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Background/Objectives: Oral hygiene is crucial to preventing dental caries. However, many preschool children fail to maintain proper oral hygiene practices due to a lack of assistance from parents and dentists because tooth brushing seems too lengthy and tedious. The goal of this article is to design a gamified mobile application called "GoGo Brush" that will appeal to Arab preschoolers and verify its effectiveness in enhancing their oral condition and their parents' knowledge. Methods: There were two groups: a study group of 122 children and parents, and a control group of 50 children. Parents in the study group filled in questionnaires, and all children received toothbrushes and education on oral hygiene. Plaque and gingival indices were measured. The study group was introduced to the GoGo Brush app and a video on plaque removal. The app's effectiveness was assessed over one week and one month. Changes in plaque and gingival status were noted. Researchers also conducted a usability evaluation of the app. Results: The app led to significant improvements in plaque and gingival indices after one month compared to the baseline and control groups. Plaque scores decreased from 2.41±0.28 to 0.695±0.25 (p<0.001) and gingival scores from 0.942±0.36 to 0.325±0.2 (p<0.001). Parental awareness of oral health topics also increased. Conclusion: The Go Go Brush app shows promise in improving oral health among preschool children and enhancing parental awareness, highlighting the potential of technology-assisted interventions in early childhood dental care ten pertinent keywords specific to the article yet reasonably common within the subject discipline.)

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Utilization of mobile health application.

2.2. Mobile health applications for oral hygiene promotion.

3. Materials and Methods

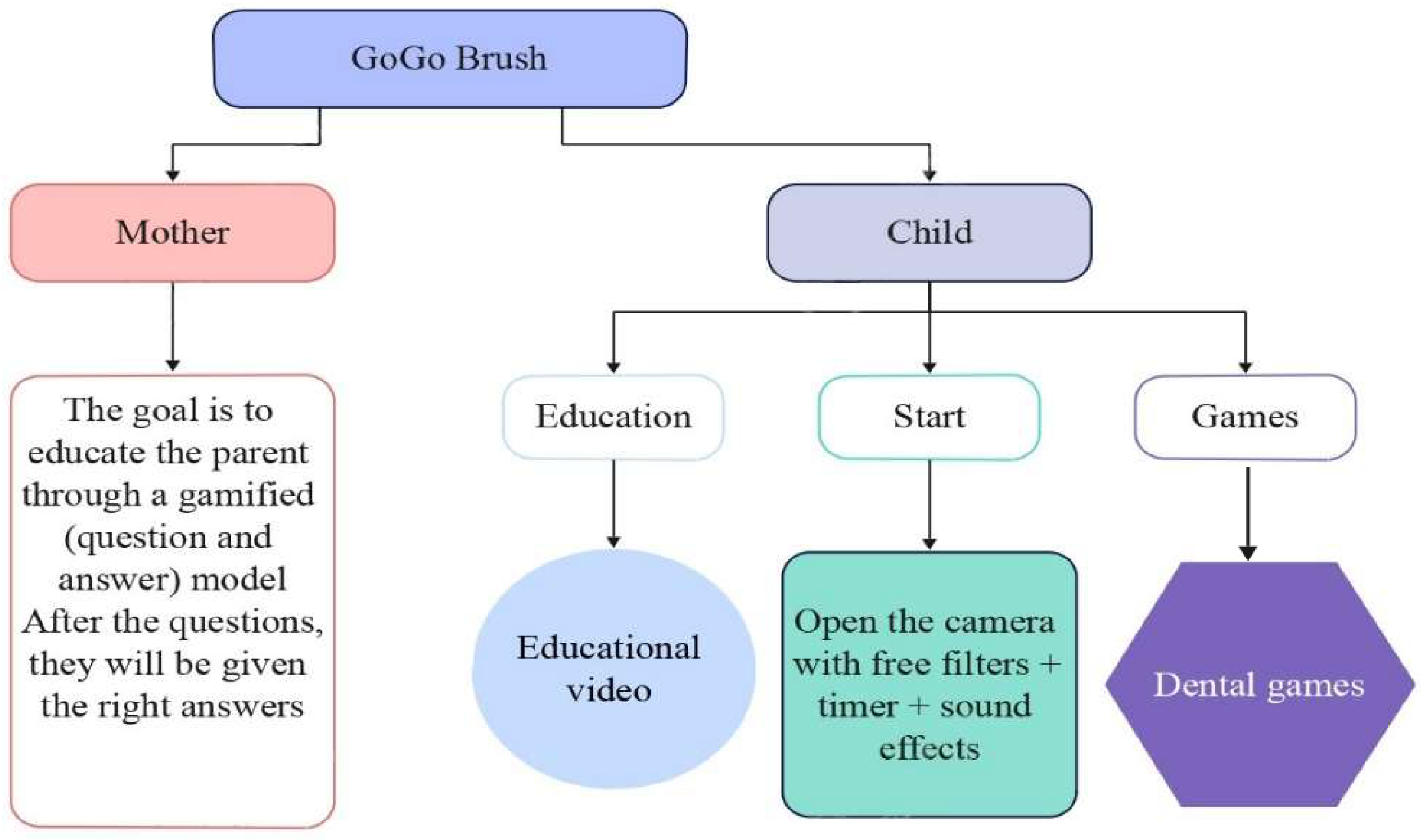

3.1. Design and Development of “Go Go Brush” Application

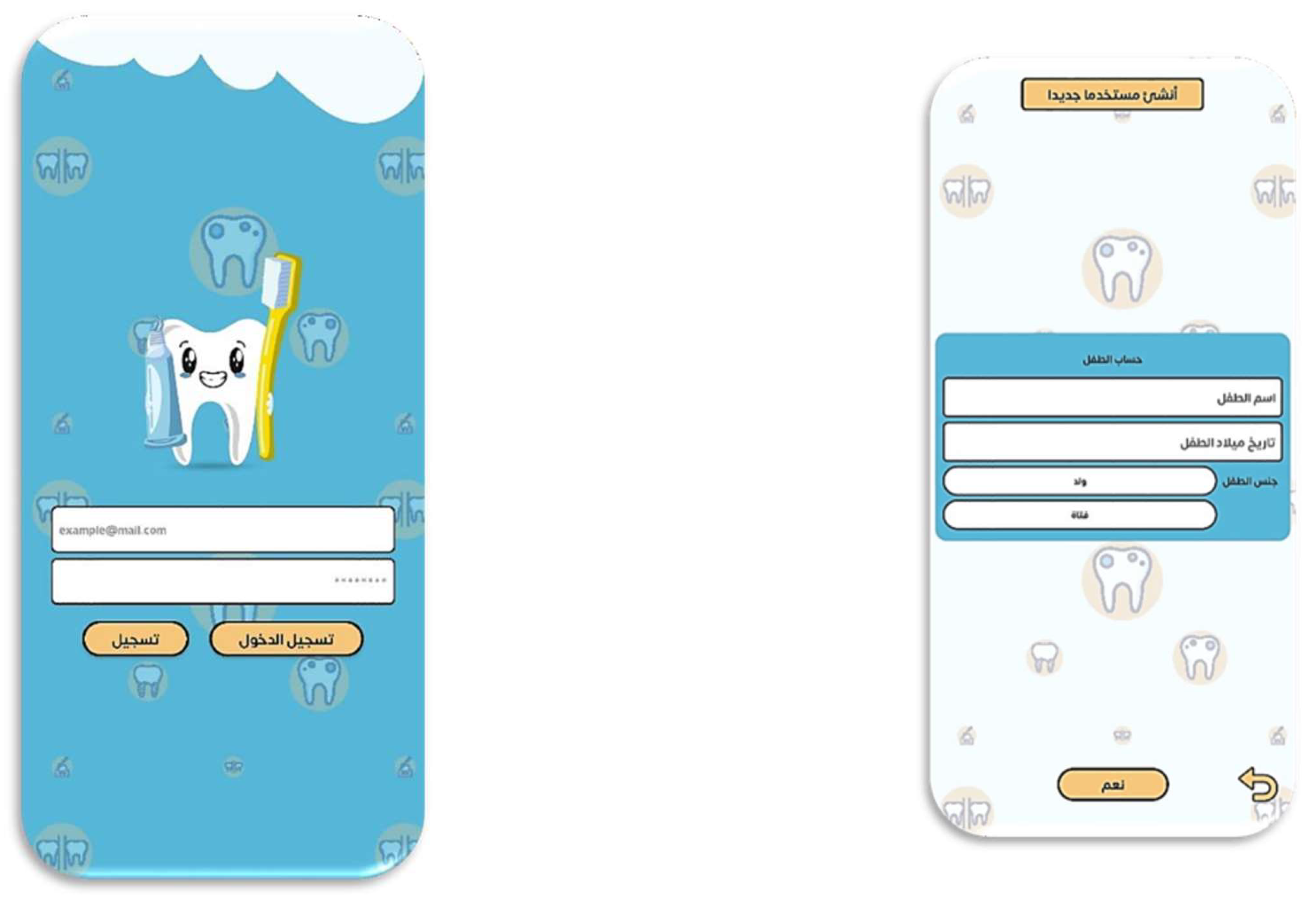

3.1.1. General description

3.1.2. Analysis of the application

3.1.3. Design of Go Go Brush: The app includes:

- Screens description:

- The splash screen is the first screen users see, displaying a logo and start button (Figure 3).

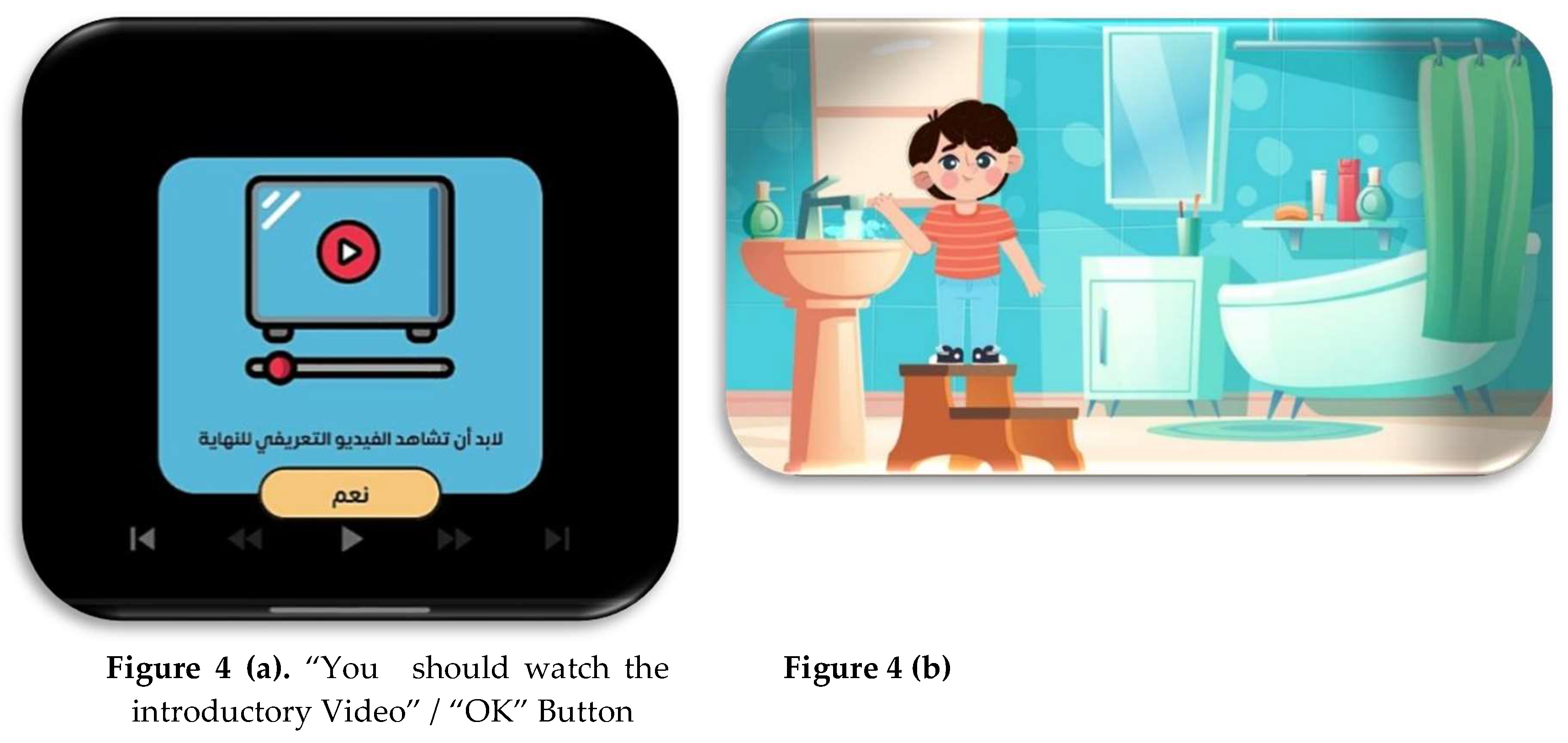

- Educational video: A mandatory, one-minute video explaining the Fones' circular tooth brushing technique in Egyptian Arabic (Figure 4).

- Home screen: Features three buttons:

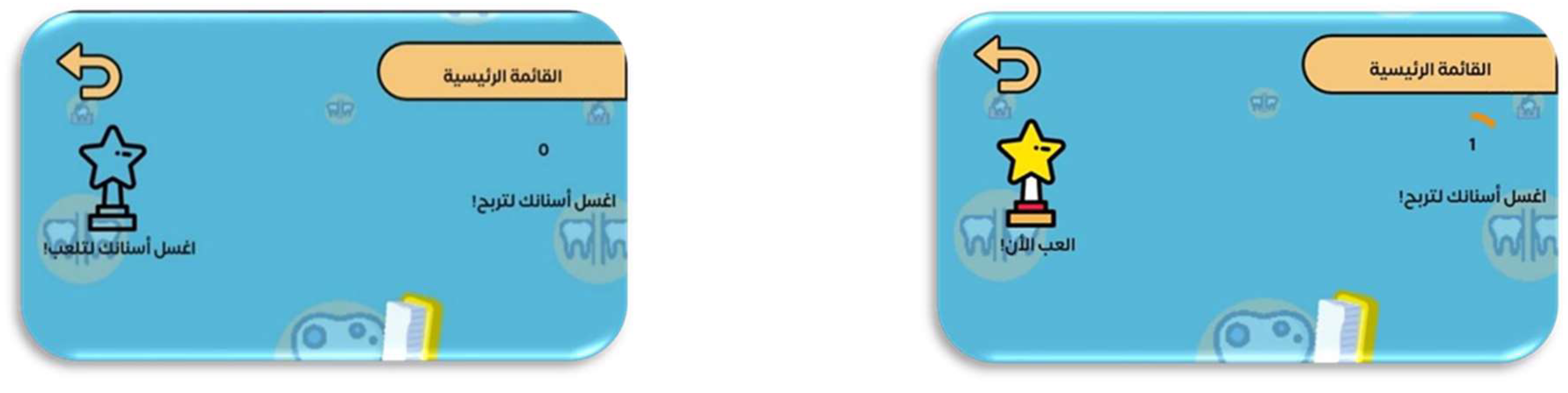

- Play: Unlocks four games after brushing once a day (Figure 10).

- Choose a cap: New caps unlock weekly for consistent brushing (Figure 11).

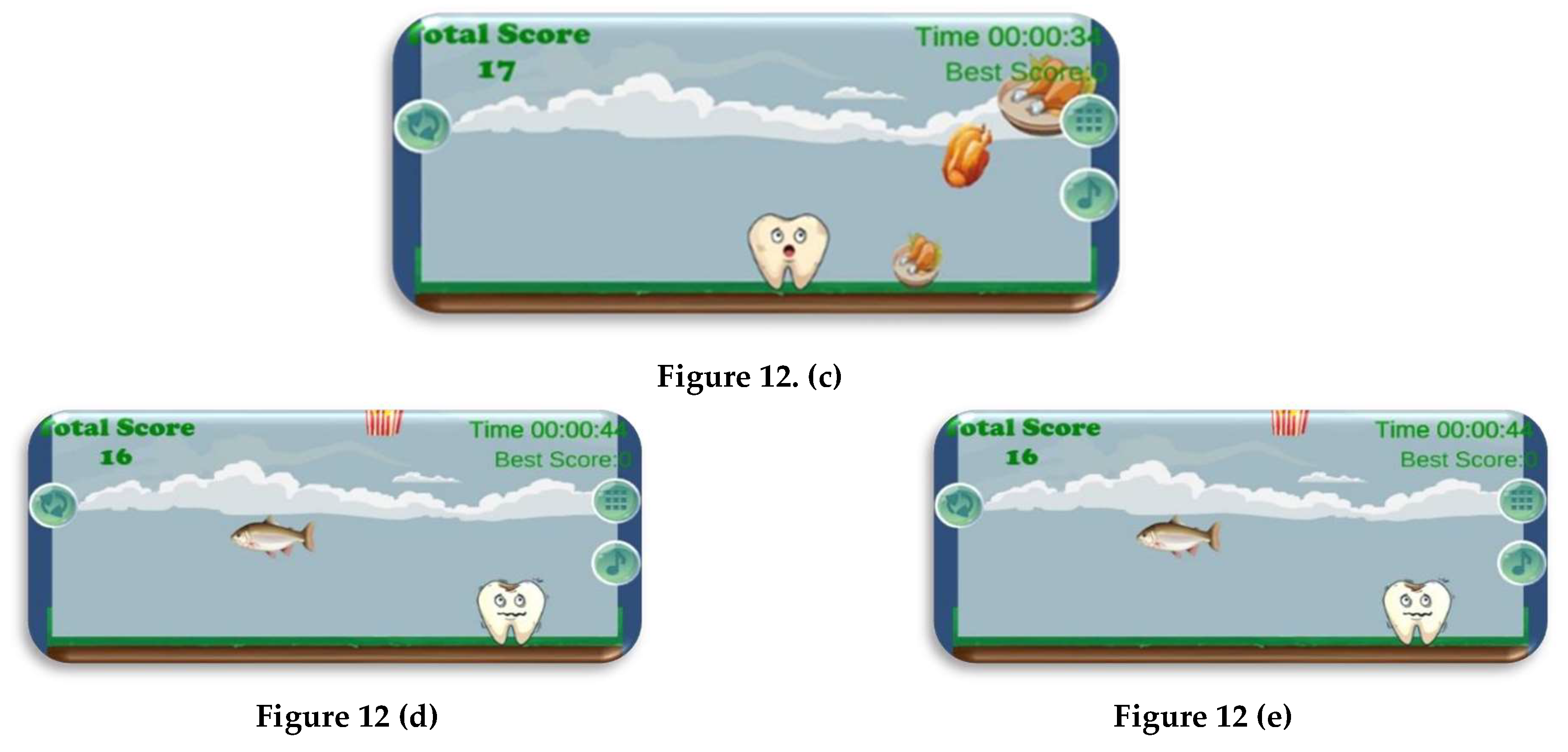

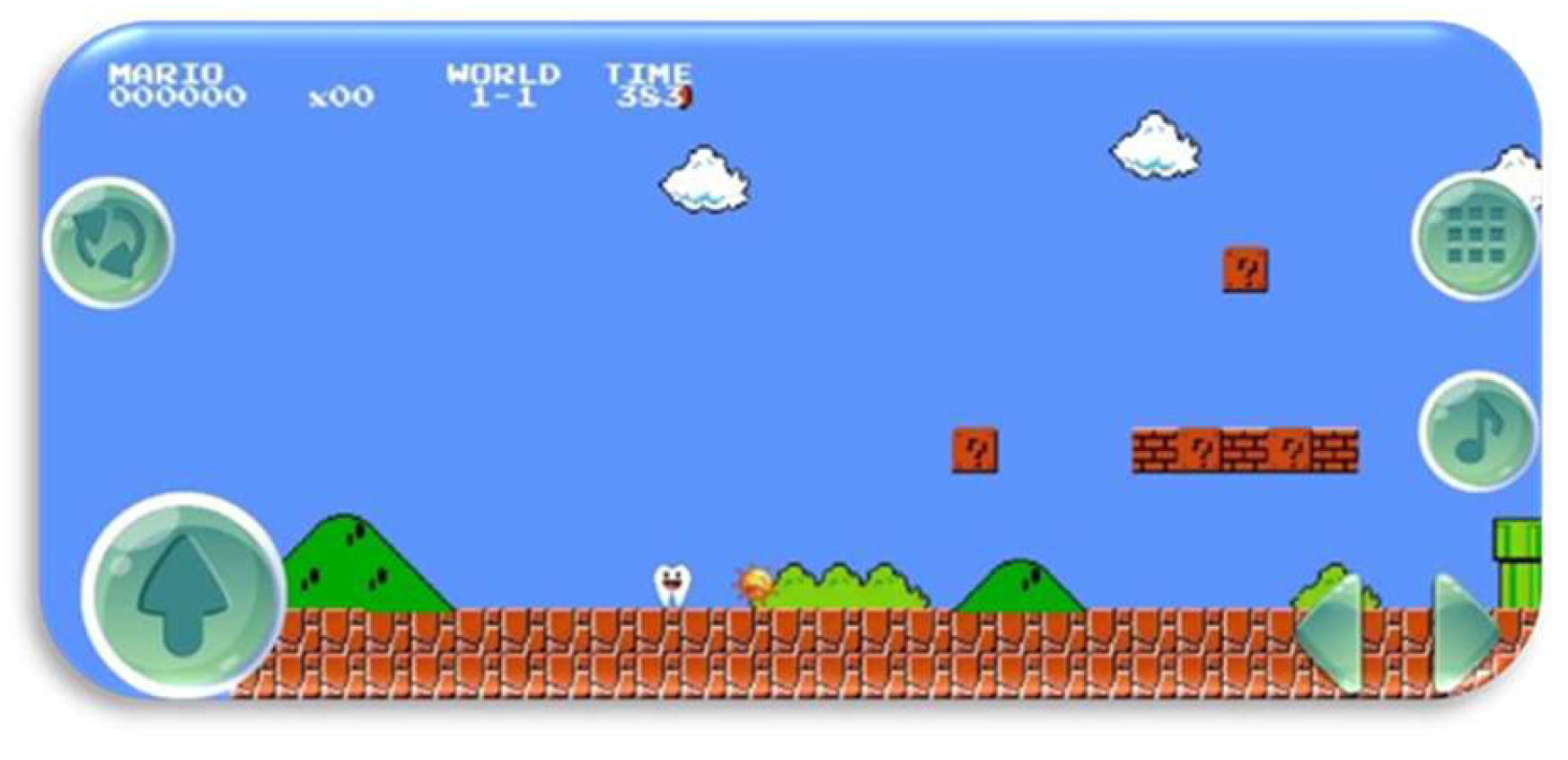

- Games menu: Four games designed to motivate children about dental health:

- Catch Food: Selects healthy foods to gain points (Figure 12).

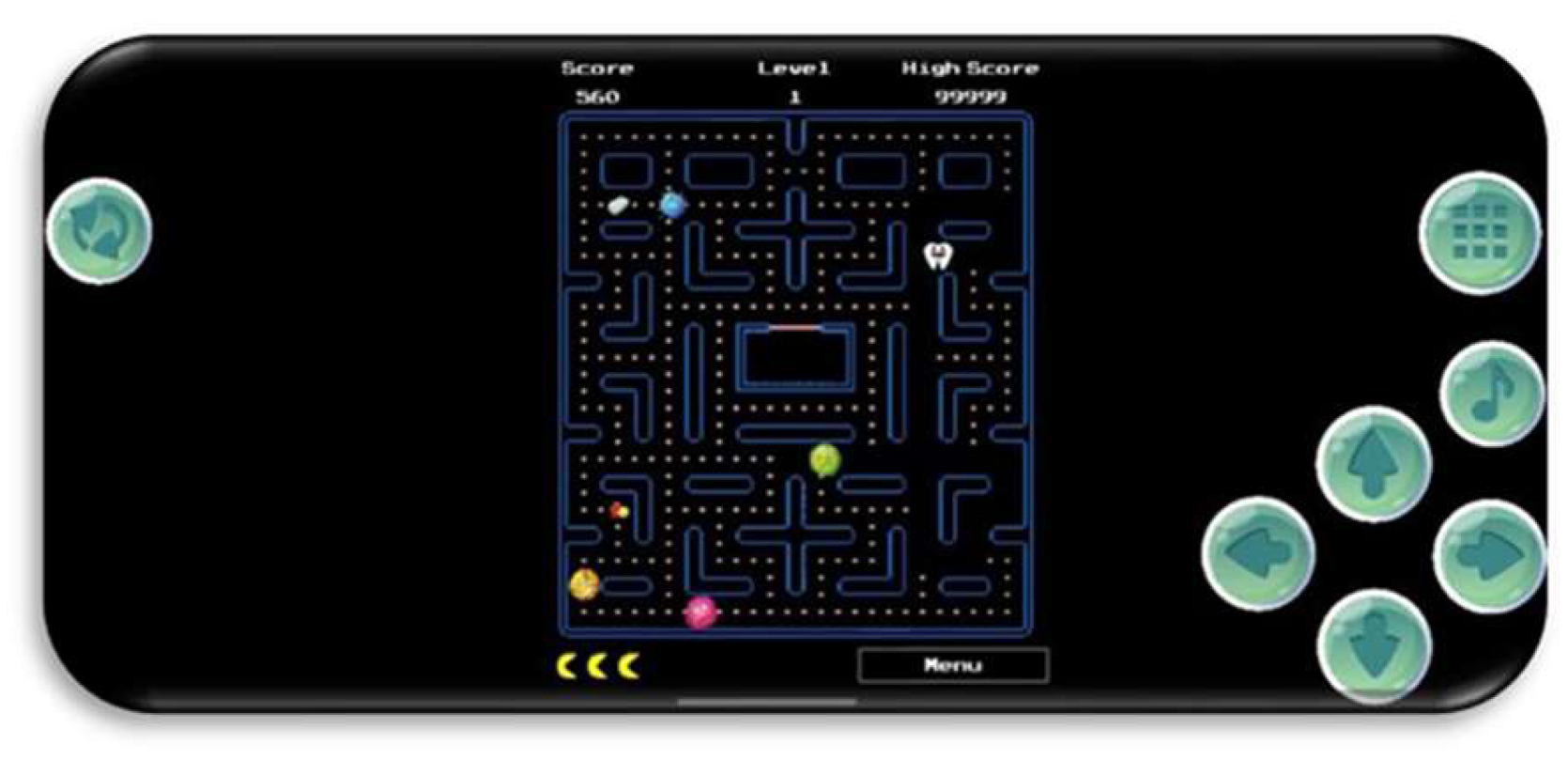

- Pac-Man style game: Modified for dental health, with a tooth character avoiding bacteria (Figure 13).

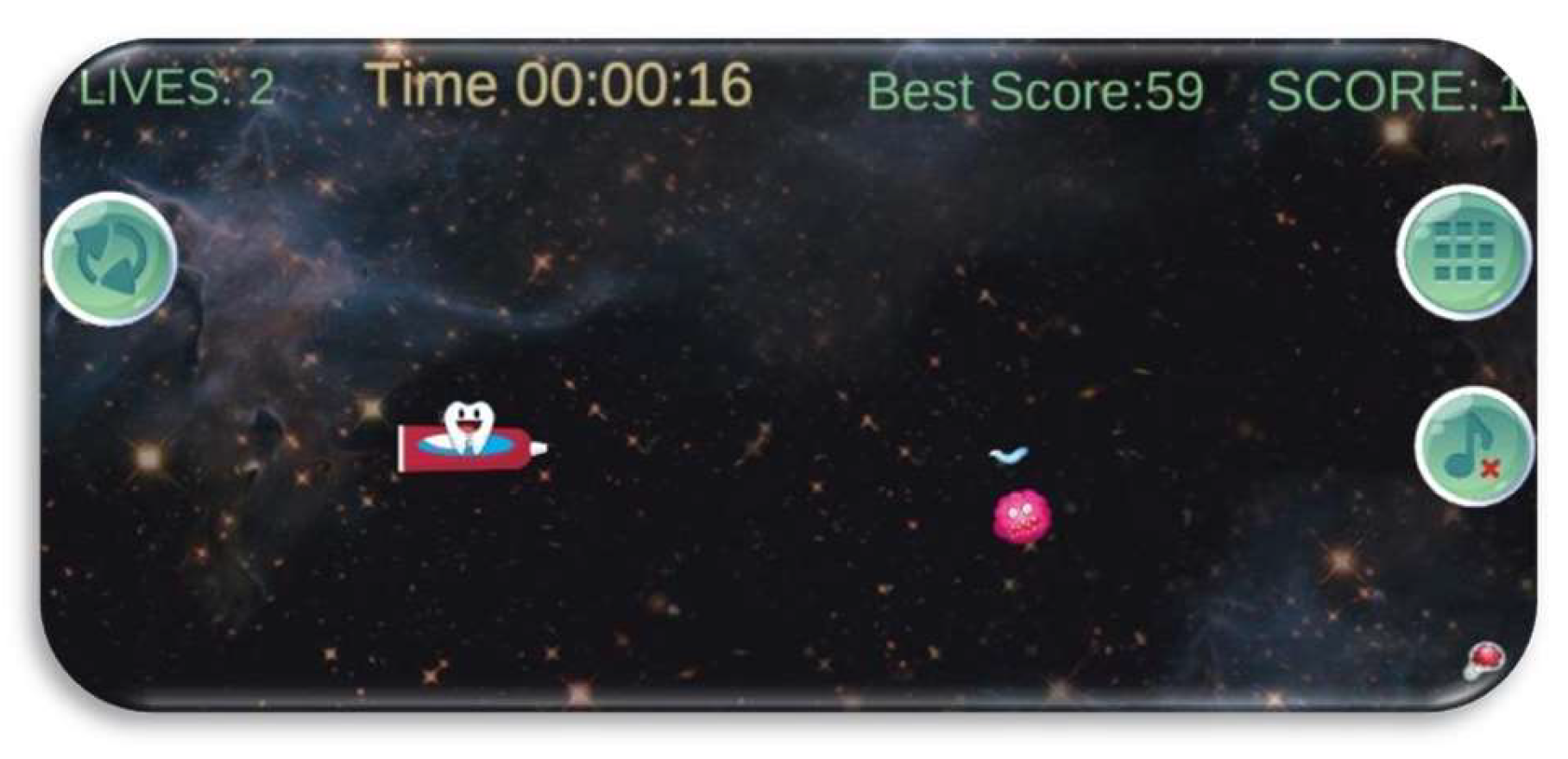

- Space Tooth: A tooth character uses toothpaste to destroy bacteria (Figure 14)

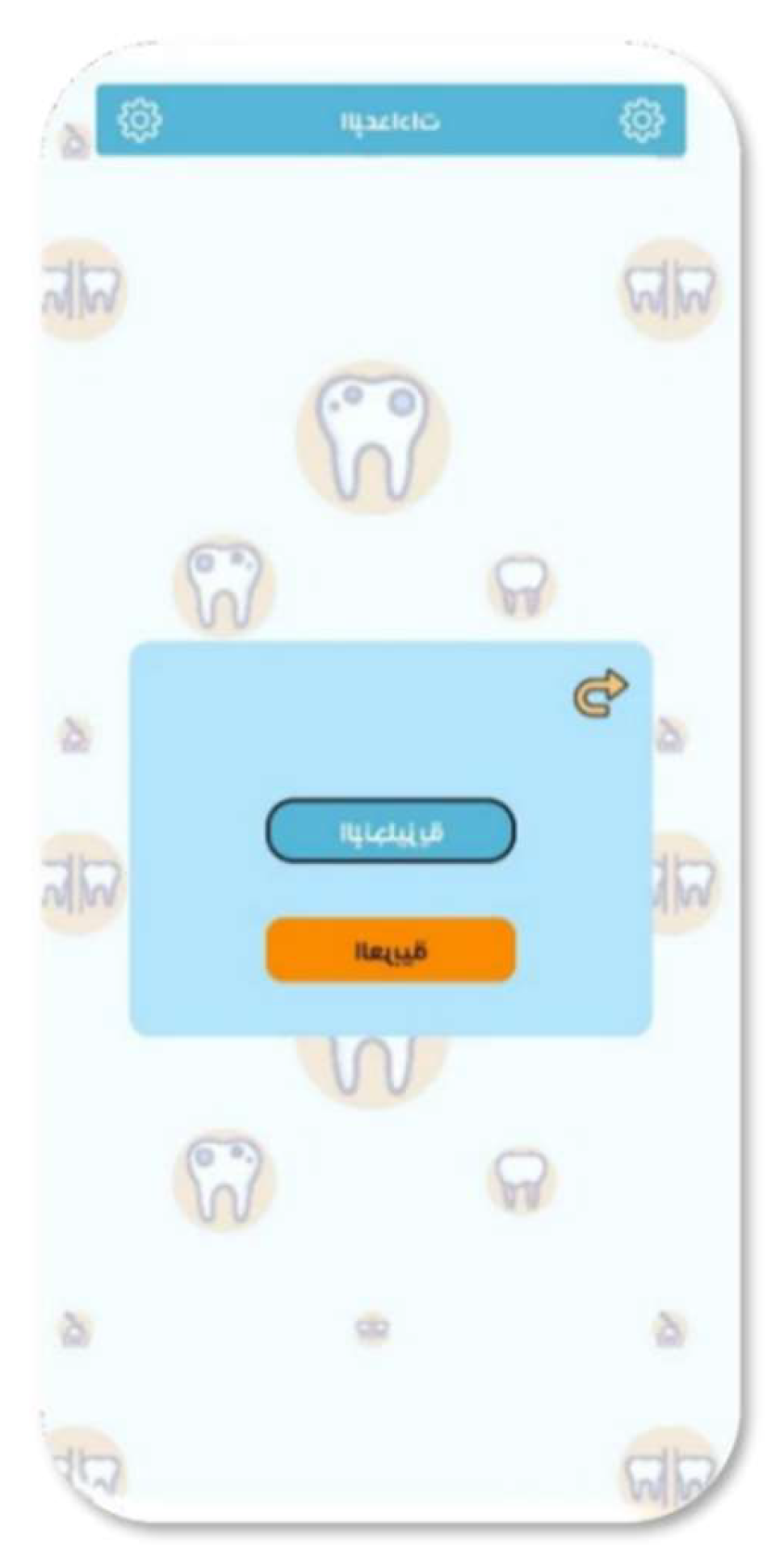

- Settings screen: Accessible only to parents, includes seven options:

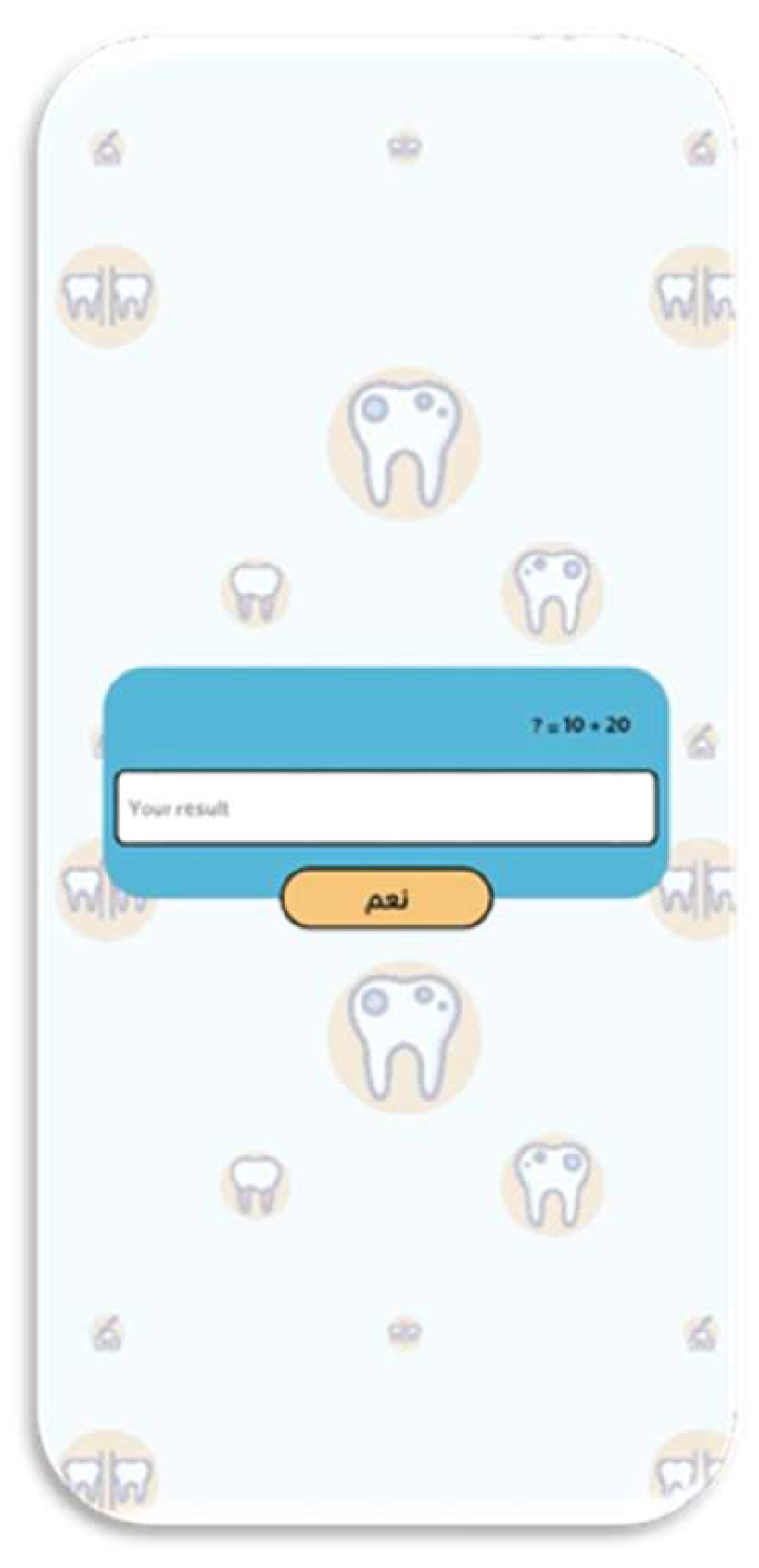

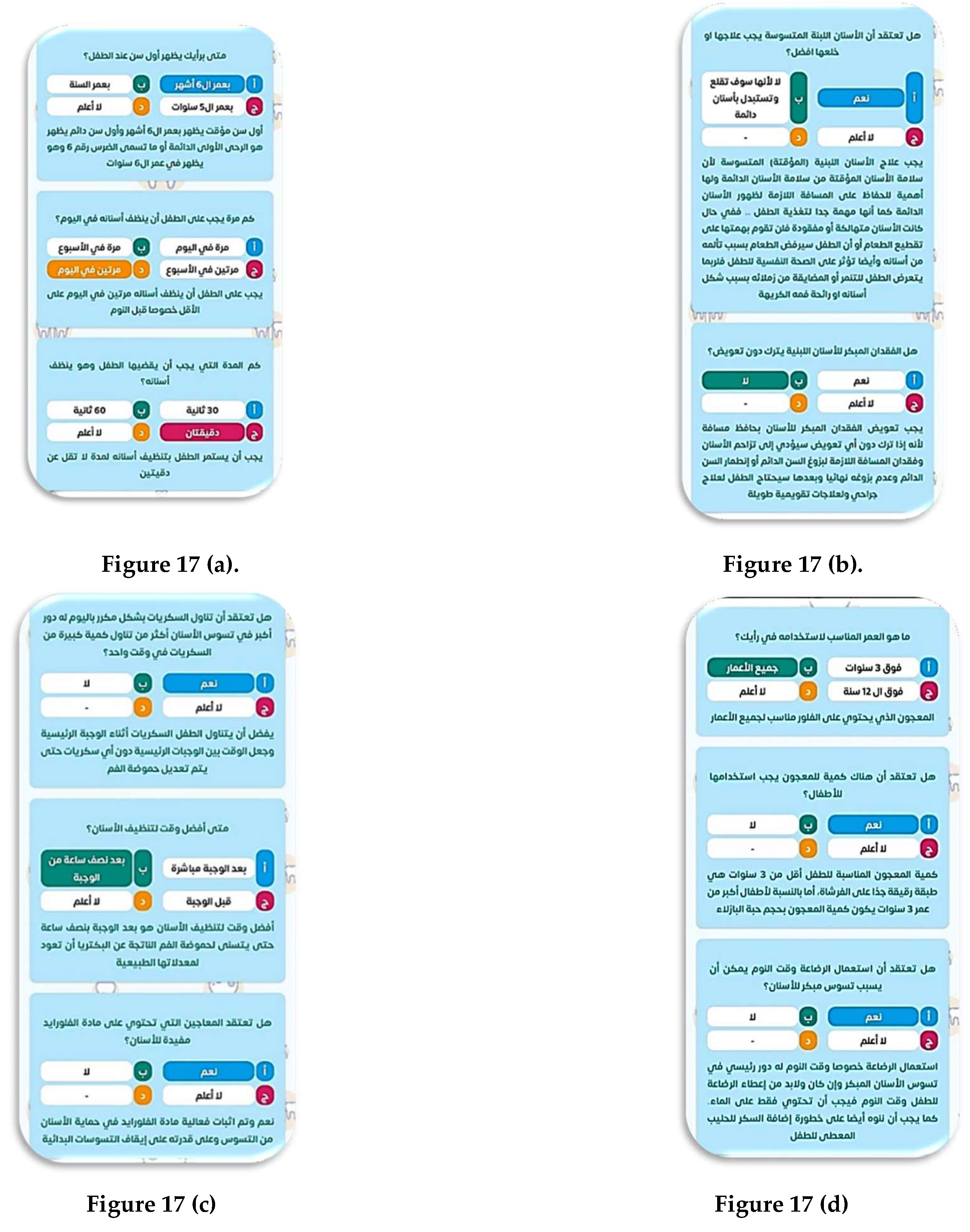

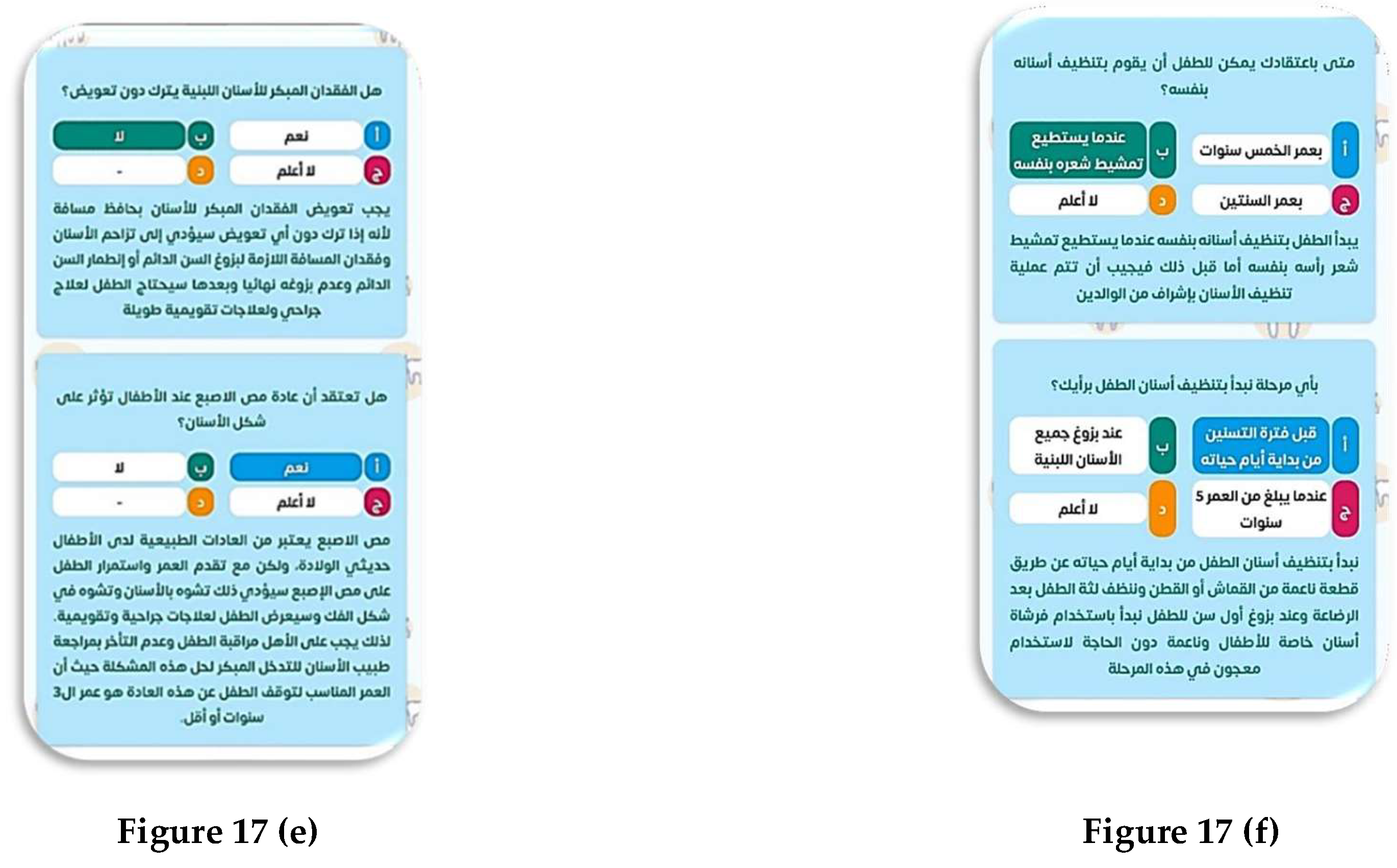

- Prove yourself: Educational questions promoting parental awareness (Figure 16).

- Watch the intro video: Replays the educational video (Figure 4).

- Questionnaire screens. Figure 17

- Brushing settings: Controls brushing time from 30 seconds to two minutes (Figure 18).

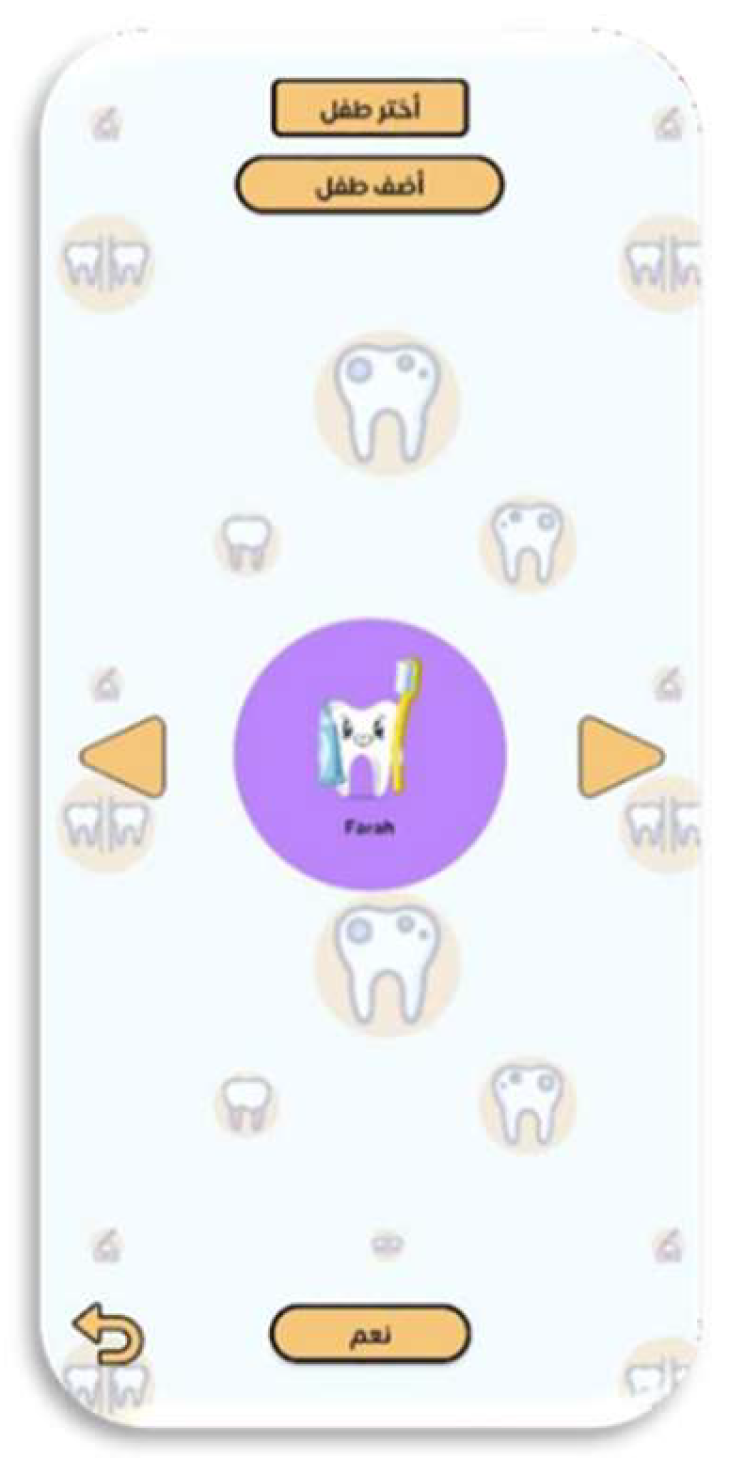

- Change user: Allows adding and switching between multiple children (Figure 19).

- Language: Switches between Arabic and English versions of the app (Figure 20).

- Privacy policy: Views the app's privacy policies (Figure 21).

- Log out: Logs out the user.

3.1.4. The Followed “Design for children’ guidelines, principals and standards” in Go Go Brush

3.1.5. Applying the Game-Based Learning and Gamification Techniques in Go Go Brush Application.

- Gamification is not competitive, while game-based learning is.

- Gamification incorporates game design elements into traditional learning environments to increase engagement.

- Awards are given in gamification for accomplishing objectives.

- Gamification involves a series of tasks, while game-based learning has goals and rules.

- Game-based learning requires more time and resources to develop.

- Gamification for task completion rewards.

- Game-based learning through actual games to teach dental concepts.

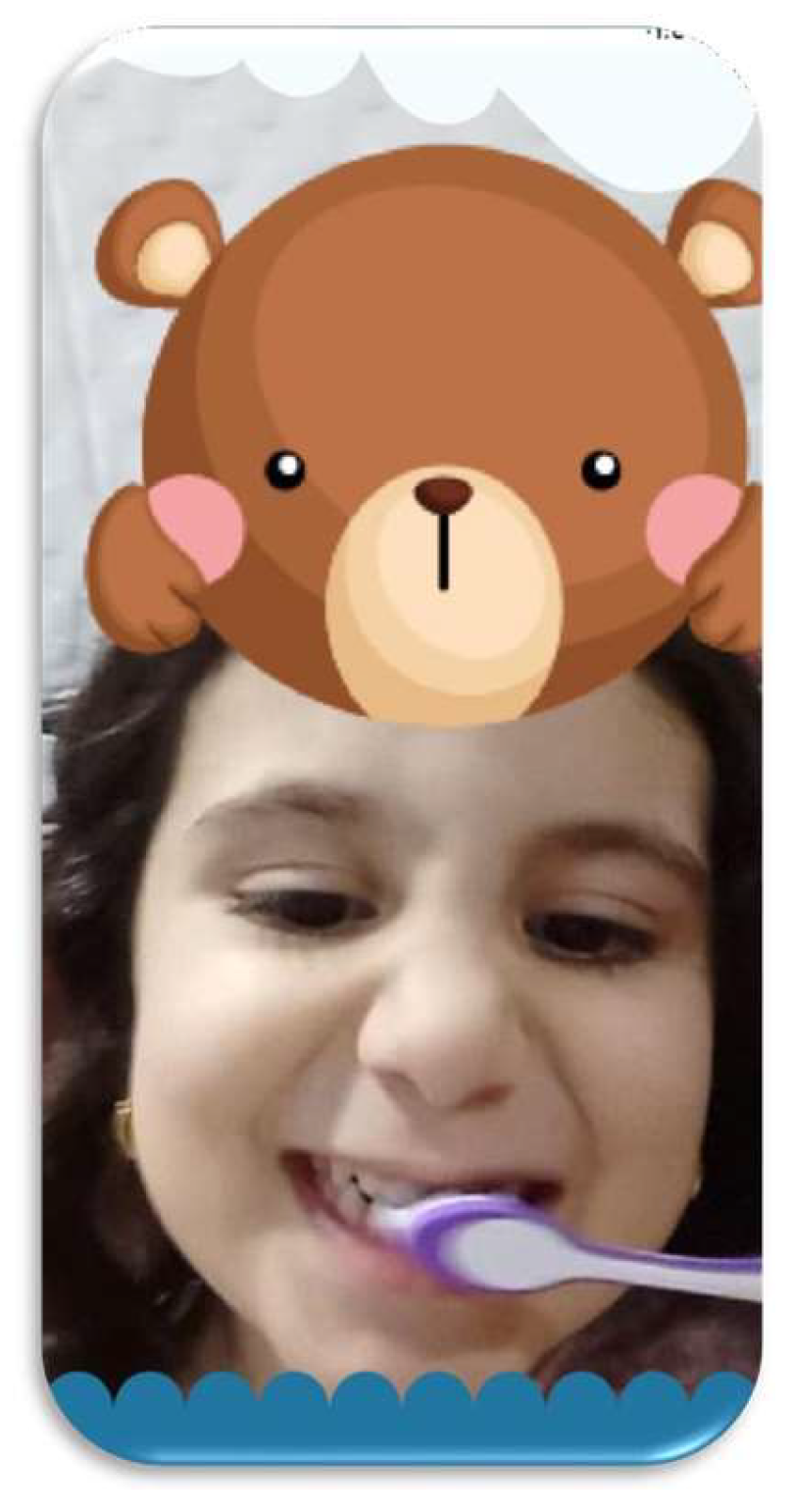

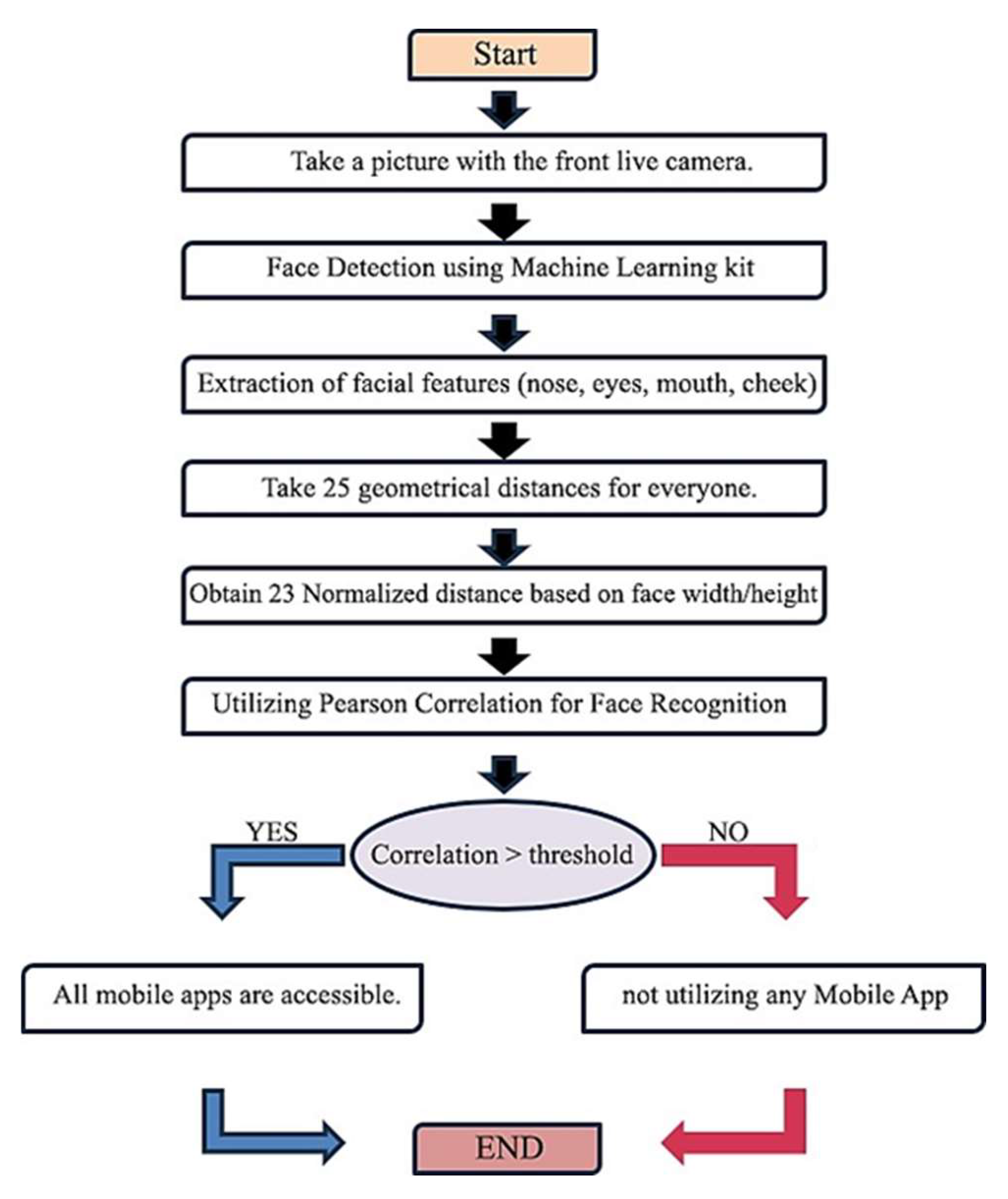

3.1.6. Algorithm and Methodology of Face Recognition.

- Augmented Reality: AR enhances a real-world environment with virtual information, improving user interaction and sensory experience. It benefits both indoor and outdoor use by enhancing user contact with the real world [49].

3.2. Methodology

3.2.1. Sampling

- Ethical considerations: Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Mansoura Research Ethics Committee, Faculty of Dentistry, Mansoura University (code number: A03051021). Informed consent was obtained from parents for their children's participation.

- Sample size calculation: The sample size was calculated with 5% significance and 95% power using G*Power 3.1.9.7, based on [4]. The mean practice score before intervention was 13.69 (SD=3.89) and after intervention was 16.02 (SD=3.48). The sample size was increased to 172 participants from an initial 110.

- Study population: From 230 screened children, 172 (84 girls, 88 boys) were selected based on inclusion criteria: normal mentality, age 4-6 years, and having a smartphone. Exclusion criteria included systemic diseases (e.g., diabetes), history of anxiety disorder, and plaque index score less than two.

- Study procedure: Participants were divided into a study group (122 children, 59 girls, 63 boys) and a control group (50 children, 25 girls, 25 boys). The study included a clinical part and a questionnaire, with follow-ups at baseline, one week, and one month.

3.2.2. Clinical part.

- Ensure the child meets the inclusion criteria.

- Parent completes the questionnaire and consents.

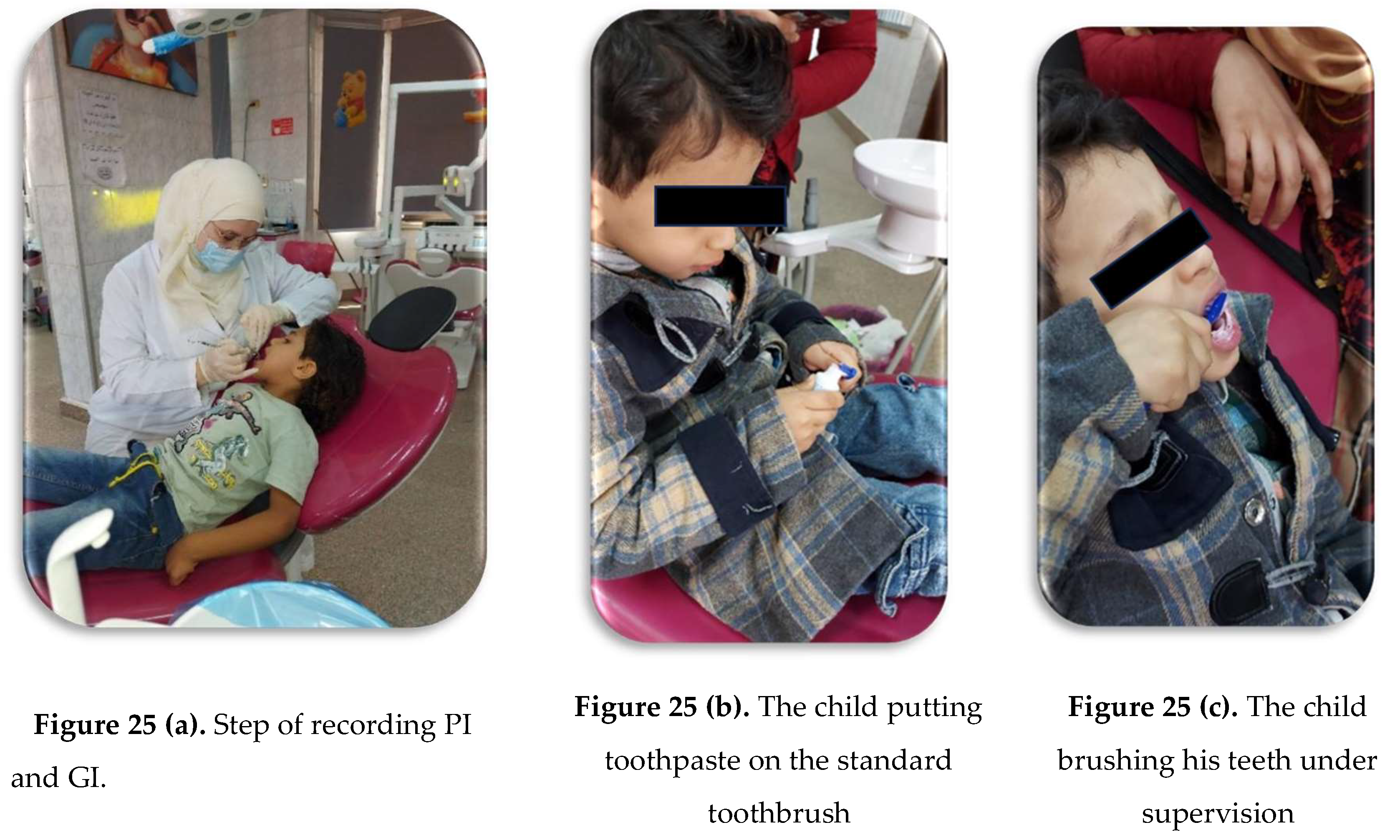

- Apply disclosing agent to show plaque areas to the child (Figure 24).

- Examine plaque and gingival index using a diagnostic kit. Scores are based on the “Löe & Silness” modified dental plaque index [50].

- Plaque index: Scores range from zero to three based on plaque visibility and removal.

- Gingival index: Scores range from zero to three based on inflammation and bleeding.

- Demonstrate Fones’ circular tooth brushing technique using a dental demo [51].

- Provide a standard toothbrush and fluoride toothpaste, educating on proper toothpaste amount.

- Supervise child’s tooth brushing for two minutes (Figure 28a-c).

- Reapply disclosing agent to show brushing effectiveness (Figure 29).

- Record plaque index again.

- Install Go Go Brush app on parents’ phones and guide them on usage, especially the "Prove Yourself" section.

- Child watches the educational video twice.

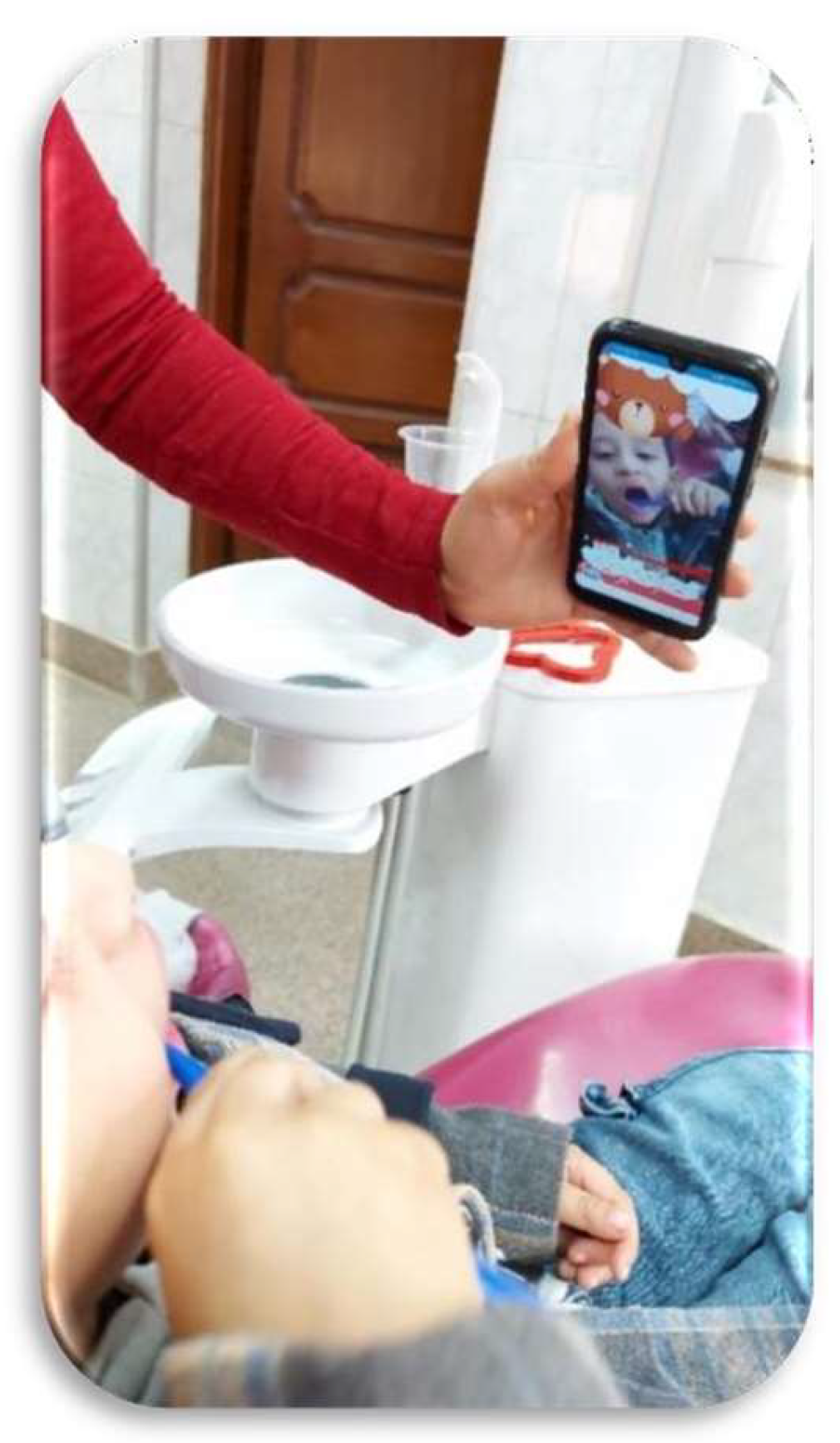

- Child uses the app’s "Get Brushing" feature with camera filter (Figure 30).

- Instruct parents and child to use the app daily at bedtime until the next visit.

- Second Visit: One week after the first visit, the app rewards a new cap, confirming the child’s use. Record GI and PI, and schedule the third visit.

- Third Visit: After one month of using the app, record GI and PI, and parent completes the awareness questions.

- Control Group: Follow the same steps as the study group, excluding the mobile application usage. Evaluate plaque and gingival status at baseline, one week, and one month.

- Demographic information.

- Practical questions.

- Awareness questions.

- "Irregular" = 2

- "When there is a problem" = 1

- "Never" = 0

- Three times a day = 0

- Twice a day = 1

- Once a day = 2

- Rarely = 3

- Not every day = 4

- Irregularly = 1

- Never cleaned = 0

- Once a day = 2

- More than once a day = 3

- Always = 3

- Frequently = 2

- Rarely = 1

- Never = 0

- Always = 3

- Most of the time = 2

- Sometimes = 1

- Never = 0

- I don't know = 0

- The third part includes 15 questions assessing parents' knowledge about primary teeth care. Answers are "yes," "no," or "I don't know," scored as "1" for correct and "0" for incorrect answers. The app includes a "prove yourself" section with questions and explanations to promote awareness. Parents completed the questionnaire on the first and third visits.

3.3. Validity and Reliability

- The questionnaire translation was tested by five dental professionals and modified based on their feedback.

- A pilot study with 20 mothers at Mansoura University's pediatric dentistry clinics refined the questionnaire, achieving a coefficient of agreement of 90% and 92%.

3.4. Statistical Analysis

- Qualitative data were described using numbers and percentages and compared by McNemar test.

- Continuous variables were presented as mean ± SD for normally distributed data. Paired groups were compared with paired t-tests, different groups with Independent t-tests, and more than two groups with ANOVA. Repeated measures ANOVA was used for one group at different follow-up periods.

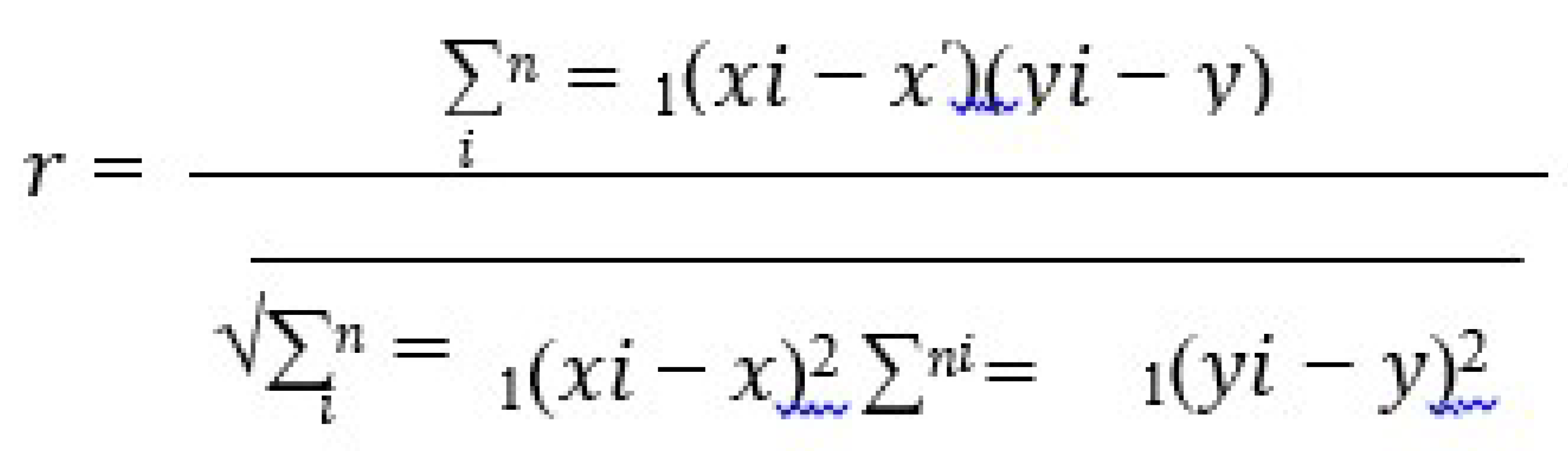

- Spearman correlation was used for continuous data and ordinal data.

4. Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Children's susceptibility to dental caries.

5.2. Development of the gamification application.

5.3. Impact measurement.

5.4. Choice of platform.

5.5. Reminder notifications.

5.6. Effectiveness in orthodontic patients.

5.7. Correlation with demographics.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sukanto, S.; Ibnurrafif, R.; Sulistiyani, S.; Lestari, S.; Pujiastuti, P.; Setyorini, D.; Probosari, N.; Budirahardjo, R.; Prihatiningrum, B. Description of dental caries in primary molars and the effect of giving dental health education on dental and oral hygiene in preschooler. Int. J. Med. Sci. Clin. Res. Stud. 2023, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, R.V.; Badrapur, N.C.; Mittapalli, H.; Srivastava, B.K.; Eshwar, S.; Jain, V. "Brush up": An Innovative Technological Aid for Parents to Keep a Check of Their Children's Oral Hygiene Behaviour. Rev. Paul. Pediatr. 2021, 39, e2020085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gimenez, T.; Bispo, B.A.; Souza, D.P.; Viganó, M.E.; Wanderley, M.T.; Mendes, F.M.; Bönecker, M.; Braga, M.M. Does the decline in caries prevalence of Latin American and Caribbean children continue in the new century? Evidence from systematic review with meta-analysis. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0164903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahaei, Z.; Moradian, E.; Falahati-Marvast, F. Improving dental-oral health learning in students using a mobile application (“My tooth”): A controlled before and after study. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2022, 20, 512–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fijacko, N.; Gosak, L.; Cilar, L.; Novsak, A.; Creber, R.M.; Skok, P.; Stiglic, G. The Effects of Gamification and Oral Self-Care on Oral Hygiene in Children: Systematic Search in App Stores and Evaluation of Apps. J. Med. Internet Res. Mhealth Uhealth 2020, 8, e16365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, S.C.; Bezerra, A.C.B.; Toledo, O.A. Effectiveness of teaching methods for toothbrushing in preschool children. Braz. Dent. J. 2002, 13, 133–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pareek, S.; Nagaraj, A.; Yousuf, A.; Ganta, S.; Atri, M.; Singh, K. Effectiveness of supervised oral health maintenance in hearing impaired and mute children-A parallel randomized controlled trial. J. Int. Soc. Prev. Community Dent. 2015, 5, 176. [Google Scholar]

- Hotwani, K.; Sharma, K.; Nagpal, D.; Lamba, G.; Chaudhari, P. Smartphones and tooth brushing: content analysis of the current available mobile health apps for motivation and training. Eur. Arch. Paediatr. Dent. 2020, 21, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolfaghari, M.; Shirmohammadi, M.; Shahhosseini, H.; Mokhtaran, M.; Mohebbi, S.Z. Development and evaluation of a gamified smart phone mobile health application for oral health promotion in early childhood: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Oral Health 2021, 21, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Underwood, B.; Birdsall, J.; Kay, E. The use of a mobile app to motivate evidence-based oral hygiene behaviour. Br. Dent. J. 2015, 219, E2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luxton, D.D.; McCann, R.A.; Bush, N.E.; Mishkind, M.C.; Reger, G.M. mHealth for mental health: Integrating smartphone technology in behavioral healthcare. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2011, 42, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demidowich, A.P.; Lu, K.; Tamler, R.; Bloomgarden, Z. An evaluation of diabetes self-management applications for Android smartphones. J. Telemed. Telecare 2012, 18, 235–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huckvale, K.; Car, M.; Morrison, C.; Car, J. Apps for Asthma Self-Management: A Systematic Assessment of Content and Tools. BMC Med. 2012, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kristjánsdóttir, Ó.B.; Fors, E.A.; Eide, E.; Finset, A.; Stensrud, T.L.; van Dulmen, S.; Wigers, S.H.; Eide, H. A Smartphone-Based Intervention with Diaries and Therapist-Feedback to Reduce Catastrophizing and Increase Functioning in Women with Chronic Widespread Pain: Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2013, 15, e2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, J.A.; Moreau, J.F.; Akilov, O.; Patton, T.; English, J.C.; Ho, J.; Ferris, L.K. Diagnostic Inaccuracy of Smartphone Applications for Melanoma Detection. JAMA Dermatol. 2013, 149, 422–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campos, L.; Cavalcante, J.P.; Machado, D.P.; Marcal, E.; Silva, P.G.B.; Rolim, J. Development and Evaluation of a Mobile Oral Health Application for Preschoolers. Telemed J. E Health 2019, 25, 492–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheerman, J.F.; van Meijel, B.; van Empelen, P.; Verrips, G.H.; van Loveren, C.; Twisk, J.W.; Pakpour, A.H.; van den Braak, M.C.; Kramer, G.J. The Effect of Using a Mobile Application (“WhiteTeeth”) on Improving Oral Hygiene: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2020, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spetz, J.; Pourat, N.; Chen, X.; Lee, C.; Martinez, A.; Xin, K.; Hughes, D. Expansion of Dental Care for Low-Income Children Through a Mobile Services Program. J. Sch. Health 2019, 89, 619–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrazzano, G.; Cantile, T.; Sangianantoni, G.; Ingenito, A. Effectiveness of a Motivation Method on the Oral Hygiene of Children. Eur. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2008, 9, 183–187. [Google Scholar]

- Sadana, G.; Gupta, T.; Aggarwal, N.; Rai, H.K.; Bhargava, A.; Walia, S. Evaluation of the Impact of Oral Health Education on Oral Hygiene Knowledge and Plaque Control of School-going Children in the City of Amritsar. J. Int. Soc. Prev. Community Dent. 2017, 7, 259–263. [Google Scholar]

- Subburaman, N.; Madan Kumar, P.D.; Iyer, K. Effectiveness of Musical Toothbrush on Oral Debris and Gingival Bleeding Among 6–10-Year-Old Children: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Indian J. Dent. Res. 2019, 30, 196–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yıldırım, S.; Kayaaltı-Yüksek, S. The Effects of Motivational Methods Applied During Toothbrushing on Children's Oral Hygiene and Periodontal Health. Pediatr. Dent. 2020, 42, 424–430. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Akkaya, D.D.; Sezici, E. Teaching Preschool Children Correct Toothbrushing Habits Through Playful Learning Interventions: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2021, 56, e70–e76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scherenberg, V.; Kramer, U. Schöne neue Welt: Gesünder mit Health-Apps? Hintergründe, Handlungsbedarf und schlummernde Potenziale. Jahrb. Healthc. Mark. 2013, 115–119. [Google Scholar]

- Underwood, B.; Birdsall, J.; Kay, E. The use of a mobile app to motivate evidence-based oral hygiene behaviour. Br. Dent. J. 2015, 219, E2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiordelli, M.; Diviani, N.; Schulz, P.J. Mapping mHealth research: a decade of evolution. J. Med. Internet Res. 2013, 15, e2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventola, C.L. Mobile devices and apps for health care professionals: uses and benefits. Pharm. Ther. 2014, 39, 356. [Google Scholar]

- Klasnja, P.; Pratt, W. Healthcare in the pocket: mapping the space of mobile-phone health interventions. J. Biomed. Inform. 2012, 45, 184–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, R.B.; Leshner, G.; Almond, A. The extended iSelf: The impact of iPhone separation on cognition, emotion, and physiology. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 2015, 20, 119–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Free, C.; Phillips, G.; Watson, L.; Galli, L.; Felix, L.; Edwards, P.; Patel, V.; Haines, A. The effectiveness of mobile-health technologies to improve health care service delivery processes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2013, 10, e1001363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtz, B.; Mitchell, K.M.; Holmstrom, A.J.; Cotten, S.R.; Dunneback, J.K.; Jimenez-Vega, J.; Ellis, D.A.; Wood, M.A. An mHealth-Based Intervention for Adolescents With Type 1 Diabetes and Their Parents: Pilot Feasibility and Efficacy Single-Arm Study. J. Med. Internet Res. Mhealth Uhealth 2021, 9, e23916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinschert, P.; Jakob, R.; Barata, F.; Kramer, J.N.; Kowatsch, T. The Potential of Mobile Apps for Improving Asthma Self-Management: A Review of Publicly Available and Well-Adopted Asthma Apps. J. Med. Internet Res. Mhealth Uhealth 2017, 5, e113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camacho-Rivera, M.; Vo, H.; Huang, X.; Lau, J.; Lawal, A.; Kawaguchi, A. Evaluating Asthma Mobile Apps to Improve Asthma Self-Management: User Ratings and Sentiment Analysis of Publicly Available Apps. J. Med. Internet Res. Mhealth Uhealth 2020, 8, e15076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Weng, L.; Chen, Z.; Cai, H.; Lin, X.; Hu, Z.; Li, N.; Lin, B.; Zheng, B.; Zhuang, Q.; Du, B.; Zheng, Z.; Liu, M. Development and Testing of a Mobile App for Pain Management Among Cancer Patients Discharged From Hospital Treatment: Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Med. Internet Res. Mhealth Uhealth 2019, 7, e12542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pangti, R.; Mathur, J.; Chouhan, V.; Kumar, S.; Rajput, L.; Shah, S.; Gupta, A.; Dixit, A.; Dholakia, D.; Gupta, S.; Gupta, S.; George, M.; Sharma, V.K.; Gupta, S. A machine learning-based, decision support, mobile phone application for diagnosis of common dermatological diseases. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2021, 35, 536–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, L. Immune response, inflammation, and the clinical spectrum of COVID-19. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiersinga, W.J.; Rhodes, A.; Cheng, A.C.; Peacock, S.J.; Prescott, H.C. Pathophysiology, transmission, diagnosis, and treatment of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a review. JAMA 2020, 324, 782–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, R.L.; Haskell, J.; Jenkins, B.; Capizzo, L.F.; Cooper, E.L.; Morphis, B. Innovative Use of a Mobile Web Application to Remotely Monitor Nonhospitalized Patients with COVID-19. Telemed. J. E Health 2022. [CrossRef]

- James, S.L.; Abate, D.; Abate, K.H.; Abay, S.M.; Abbafati, C.; Abbasi, N.; Abbastabar, H.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdela, J.; Abdelalim, A.; Abdollahpour, I.; Abdulkader, R.S.; Abebe, Z.; Abera, S.F.; Abil, O.Z.; et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2018, 392, 1789–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathyasri, P.; Kandavel, S. Mobile Smartphone Apps Fororal Dental Health-Review Article. Eur. J. Mol. Clin. Med. 2020, 7, 6755–6759. [Google Scholar]

- Zotti, F.; Pietrobelli, A.; Malchiodi, L.; Nocini, P.F.; Albanese, M. Apps for oral hygiene in children 4 to 7 years: Fun and effectiveness. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2019, 11, e795–e801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobson, D.; Jacobson, J.; Leong, T.; Lourenco, S.; Mancl, L.; Chi, D.L. Evaluating Child Toothbrushing Behavior Changes Associated with a Mobile Game App: A Single Arm Pre/Post Pilot Study. Pediatr. Dent. 2019, 41, 299–303. [Google Scholar]

- Alkilzy, M.; Midani, R.; Hofer, M.; Splieth, C. Improving Toothbrushing with a Smartphone App: Results of a Randomized Controlled Trial. Caries Res. 2019, 53, 628–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez Cazaux, S.; Lefer, G.; Rouches, A.; Bourdon, P. Toothbrushing training programme using an iPad® for children and adolescents with autism. Eur. Arch. Paediatr. Dent. 2019, 20, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.P.P.; Séllos, M.C.; Ramos, M.E.B.; Soviero, V.M. Oral hygiene frequency and presence of visible biofilm in the primary dentition. Braz. Oral Res. 2007, 21, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharififard, N.; Sargeran, K.; Gholami, M.; Zayeri, F. A music- and game-based oral health education for visually impaired school children; multilevel analysis of a cluster randomized controlled trial. BMC Oral Health 2020, 20, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Designing for Children’s Rights. Design Principles. Available online: http://designingforchildrensrights.org/ (accessed on July 2022).

- Sedgwick, P. Pearson’s correlation coefficient. BMJ 2012, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.W.; Cheong, K.H. Adoption of Virtual and Augmented Reality for Mathematics Education: A Scoping Review. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 13693–13703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silness, J.; Löe, H. Periodontal disease in pregnancy II. Correlation between oral hygiene and periodontal condition. Acta Odontol. Scand. 1964, 22, 121–135. [Google Scholar]

- Bok, H.J.; Lee, C.H. Proper Tooth-Brushing Technique According to Patient’s Age and Oral Status. Int. J. Clin. Prev. Dent. 2020, 16, 149–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Gottlieb, M. Gamification Mobile Applications: A Literature Review of Empirical Studies. In Proceedings of the Springer International Publishing; 2023; pp. 933–946. [Google Scholar]

- Marçal, E.; Andrade, R.; Rios, R. Learning Using Mobile Devices with Virtual Reality Systems. Novas Tecnol. Educ. 2005, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Prensky, M. Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants Part 2: Do They Really Think Differently? On the Horizon 2001, 9, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tootell, H.; Freeman, M.; Freeman, A. (Eds.) Generation Alpha at the Intersection of Technology, Play and Motivation. In Proceedings of the 2014 47th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Machado, L.; Valença, A.; Morais, A. A Serious Game for Education about Oral Health in Babies. Tempus Actas Saúde Coletiva 2016, 10, 167–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Morais, A.; Machado, L.; Valença, A. Planning a Serious Game for Oral Health for Babies. Rev. Inform. Teor. Apl.-RITA 2011, 18, 158–175. [Google Scholar]

- Marchetti, G.; Fraiz, F.C.; Nascimento, W.M.D.; Soares, G.M.S.; Assuncao, L. Improving Adolescents' Periodontal Health: Evaluation of a Mobile Oral Health App Associated with Conventional Educational Methods: A Cluster Randomized Trial. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2018, 28, 410–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, M.S.; Medina-Solis, C.E.; Minaya-Sanchez, M.; Pontigo-Loyola, A.P.; Villalobos-Rodelo, J.J.; Islas-Granillo, H.; de la Rosa-Santillana, R.; Maupome, G. Dental Plaque, Preventive Care, and Tooth Brushing Associated with Dental Caries in Primary Teeth in Schoolchildren Ages 6–9 Years of Leon, Nicaragua. Med. Sci. Monit. 2013, 19, 1019–1026. [Google Scholar]

- Attin, T.; Hornecker, E. Tooth Brushing and Oral Health: How Frequently and When Should Tooth Brushing Be Performed? Oral Health Prev. Dent. 2005, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Shirmohammadi, M.; Razeghi, S.; Shamshiri, A.; Mohebbi, S. Impact of Smartphone Application Usage by Mothers in Improving Oral Health and its Determinants in Early Childhood: A Randomised Controlled Trial in a Paediatric Dental Setting. Eur. Arch. Paediatr. Dent. 2022, 23, 629–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkadhi, O.H.; Zahid, M.N.; Almanea, R.S.; Althaqeb, H.K.; Alharbi, T.H.; Ajwa, N.M. The Effect of Using Mobile Applications for Improving Oral Hygiene in Patients with Orthodontic Fixed Appliances: A Randomised Controlled Trial. J. Orthod. 2017, 44, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zotti, F.; Dalessandri, D.; Salgarello, S.; Piancino, M.; Bonetti, S.; Visconti, L.; Paganelli, C. Usefulness of an App in Improving Oral Hygiene Compliance in Adolescent Orthodontic Patients. Angle Orthod. 2016, 86, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashirian, S.; Shirahmadi, S.; Seyedzadeh-Sabounchi, S.; Soltanian, A.R.; Karimi-Shahanjarini, A.; Vahdatinia, F. Association of Caries Experience and Dental Plaque with Sociodemographic Characteristics in Elementary School-Aged Children: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Oral Health 2018, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| # | The principal | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Gather and respect children’s views | The Privacy Policy is explained in the Go Go Brush app. When the user initially downloads it, he or she is prompted to agree to it.If the family has more than one child, the application enables the addition of additional children to improve sharing between brothers. Furthermore, the presence of a Prove Yourself part for parents encourages parental participation in the application.The application is also free to download from Google Play. (Figure 25) |

| 2 | Everyone can use | The application has no sexual connotations or violent references and is suitable for children aged from four to six.The app never supports racism.Available to all children, male and female.When the child is dedicated tobrushing their teeth, they win several caps filters, and the app subsequently allows them to select which hat they want to wear when brushing their teeth with the camera. |

| 3 | Use communication children can understand | The clarity and simplicity of Go Go Brush's design accomplished this. It also includes an educational video that attracts children with images, sound, and even the time limit of one minute, so the child does not grow bored or lose interest. The language utilized in the video is Arabic, specifically the Egyptian dialect, because the research was conducted in Egypt, and we wanted to choose a dialect that is appropriate for children's culture.Sound effects have also been added when the child brushes his teeth using the camera and filter.The application's colors are particularly appealing to the children, and the associated caps are likewise shaped like animals that children enjoy.In terms of design and simplicity of play, the games developed in the app are appropriate for the age of thechildren targeted in our research. |

| 4 | Allow and support exploration | The application, through the games inside it, allows the child to play, make mistakes, and then learn from those mistakes. The child learns healthy and unhealthy foods for his teeth in the Catch food game by changing the form of the tooth that receives the food. He can learn from his mistakes not just in this game, but in all of the games listed, because he may replay the game several times if he loses.The application teaches the child how to clean his teeth and motivates him to do so through daily and weekly rewards. We also urge that parents brush their child's teeth with him to ensure that he has learned this skill. |

| 5 | Encourage children toplay with others | Not applicable. |

| 7 | Keep children safe and protected | The app does not contain any harmful or inappropriate content, the child will not be exposed to any unwanted or illegal content given that the application doesn't showcase any advertisements.We are considering that the behavior we are promoting and trying to develop is to teach the child how to maintain his or her oral health through different actions such as brushing their teeth and eating healthy food. |

| 8 | Do not misuse children’s data | No unnecessary information is collected from children or their parents.All data collected is general information about the age and gender of the child only.The privacy of all information collected from users is respected and this matter is explained in the attached privacy policy. Nobody looks at it and it is not sold to anyone |

| 9 | Help children recognize and understand commercial activities | The application does not contain any advertisements or any in-app purchases. |

| 10 | Design for future | The application provides this principle by displaying the correct behaviors that maintain health and differentiate them from the wrong behaviors so that the child can learn. |

| Demographic data | The studied groups (n=172) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Age (Years) Mean ± SD Min-Max |

4.98± 0.80 4-6 |

||

| Sex Male Female |

88 (51.2%) 84 (48.8%) |

||

| Social class Poor Moderate Good Excellent |

17 (9.9 %) 64 (37.2 %) 60 (34.8 %) 31 (18.1 %) |

||

|

Mother age Mean ± SD Min-Max |

31.20±4.40 24-42 |

||

|

Mother education Less than secondary educated Secondary educated University Postgraduate |

26 (21.3 %) 29 (23.8 %) 47 (38.5 %) 20 (16.4 %) |

||

|

Father education Less than secondary educated Secondary educated University Postgraduate |

23 (18.9 %) 21 (17.2 %) 56 (45.9 %) 22 (18.0 %) |

||

| Mother age Mean ± SD Min-Max |

31.20±4.40 24-42 |

|---|---|

|

Mother education Less than secondary educated Secondary educated University Postgraduate |

26 (21.3 %) 29 (23.8 %) 47 (38.5 %) 20 (16.4 %) |

|

Father education Less than secondary educated Secondary educated University Postgraduate |

23 (18.9 %) 21 (17.2 %) 56 (45.9 %) 22 (18.0 %) |

| Practice score | Study group (n=122) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency of dentist visits for your child Never At emergency Irregular Regular every 6 m |

48 (39.3%) 34 (27.9%) 34 (27.9%) 6 (4.9%) |

||

| Does your child rinse his mouth after eating sugar? Never Rarely |

17 (13.9%) 55 (45.1%) |

||

| Usually Always |

46 (37.7%) 4 (3.3%) |

||

| How many times does your child eat sugar a day? Rarely Sometimes Once daily Twice daily Three times/ day |

24 (19.7%) 26 (21.3%) 24 (19.7%) 6 (4.9%) 42 (34.4%) |

||

| Does your child brush his teeth? Yes No |

108 (88.5%) 14 (11.5%) |

||

| Who cleans your child's teeth? His parents One of his brothers/ sisters Himself under the supervision of his parents Himself |

45 (36.9%) 4 (3.3%) 52 (42.6%) 21 (17.2%) |

||

| How often does your child brush his teeth? Never Irregular Once per day More than one time /day |

3 (2.5%) 58 (47.5%) 52 (42.6%) 9 (7.4%) |

||

| Do you use a toothpaste that contains fluoride? I don’t know/Never. Sometimes Usually Always |

60 (49.2%) 22 (18.0%) 15 (12.3%) 25 (20.5%) |

||

| Total practice score Poor practice ≤ 10 Good practice > 10 |

77 (63.1%) 45 (36.9%) |

||

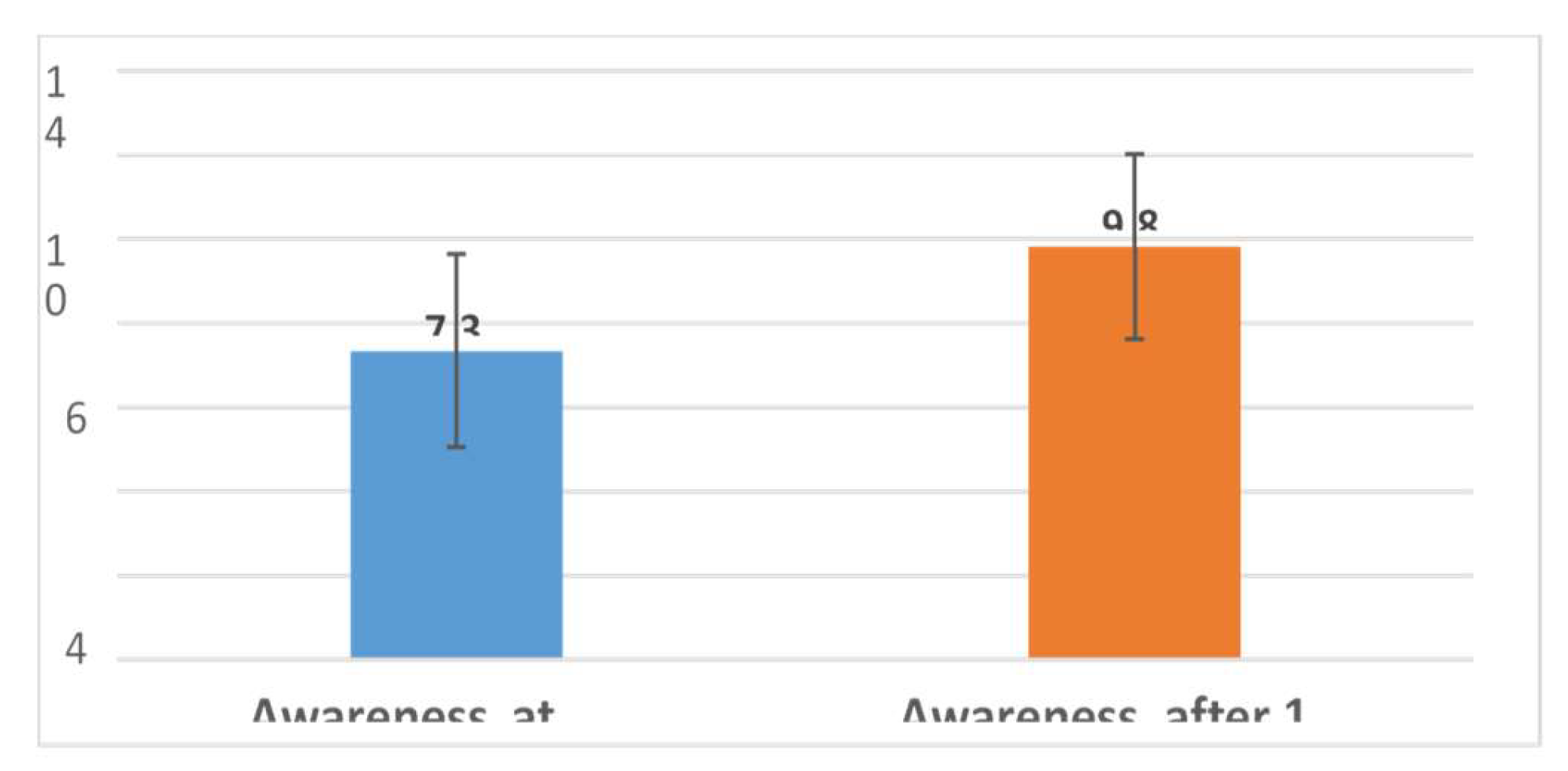

| Awareness questions | Awareness at baseline | Awareness after 1 month of using the Go Go Brush app | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correct | Incorrect | Correct | Incorrect | ||

| Q1. The first primary tooth erupts on average at 6 months of age | 82 (67.2%) | 40 (32.8%) | 108 (88.5%) | 14 (11.5%) | ≤0.001* |

| Q2. Fluoridated toothpaste can be used for children under 3 years of age. | 34 (27.9%) | 88 (72.1%) | 94 (77.0%) | 28 (23.0%) | ≤0.001* |

| Q3. the ideal amount of toothpaste is about the size of a pea | 91 (74.6%) | 31 (25.4%) | 115 (94.3%) | 7 (5.7%) | ≤0.001* |

| Q4. White lines or spots are the first signs of caries in children | 35 (28.7%) | 87 (71.3%) | 77 (63.1%) | 45 (36.9%) | ≤0.001* |

| Q5. Toothbrushing should be started following the eruption of the first primary teeth | 19 (15.6%) | 103 (84.4%) | 29 (23.8%) | 93 (76.2%) | 0.052 |

| Q6. Children should not use fluoride toothpaste | 19 (15.6%) | 103 (84.4%) | 65 (53.3%) | 57 (46.7%) | ≤0.001* |

| Q7. Fluoridated toothpaste prevents dental caries | 57 (46.7%) | 65 (53.3%) | 103 (84.4%) | 19 (15.6%) | ≤0.001* |

| Q8. The frequency of intake of sugary substances plays a more important role than the total amount consumption of sugar in caries development | 102 (83.6%) | 20 (16.4%) | 107 (87.7%) | 15 (12.3%) | 0.359 |

| Q9. The acidity of t h e oral environment caused by the activity of bacteria after mealsreturns to normal after 5 minutes | 7 (5.7%) | 115 (94.3%) | 37 (30.3%) | 85 (69.7%) | ≤0.001* |

| Q10. Bottle-feeding can cause early childhood caries | 50 (41.0%) | 72 (59.0%) | 87 (71.3%) | 35 (28.7%) | ≤0.001* |

| Q11. Carious primary teeth need to be restored | 102 (83.6%) | 20 (16.4%) | 104 (85.2%) | 18 (14.8%) | 0.791 |

| Q12. Carious primary teeth can effect on permanent teeth | 51 (41.8%) | 71 (58.2%) | 67 (54.9%) | 55 (45.1%) | 0.008* |

| Q13. Early missing of primary teeth does not need any replacement or space maintainers | 53 (43.4%) | 69 (56.6%) | 89 (73.0%) | 33 (27.0%) | ≤0.001* |

| Q14. Early missing of primary teeth without space maintainers will lead to crowding and loss of space for permanent teeth | 88 (72.1%) | 34 (27.9%) | 104 (85.2%) | 18 (14.8%) | 0.002* |

| Q15. Healthy primary teeth are essential for the child's mental health | 105 (86.1%) | 17 (13.9%) | 119 (97.5%) | 3 (2.5%) | 0.001* |

|

Mean ± SD Min-Max |

7.34±2.30 1-15 |

9.82±2.25 3-15 |

t=12.25 P≤0.001* |

||

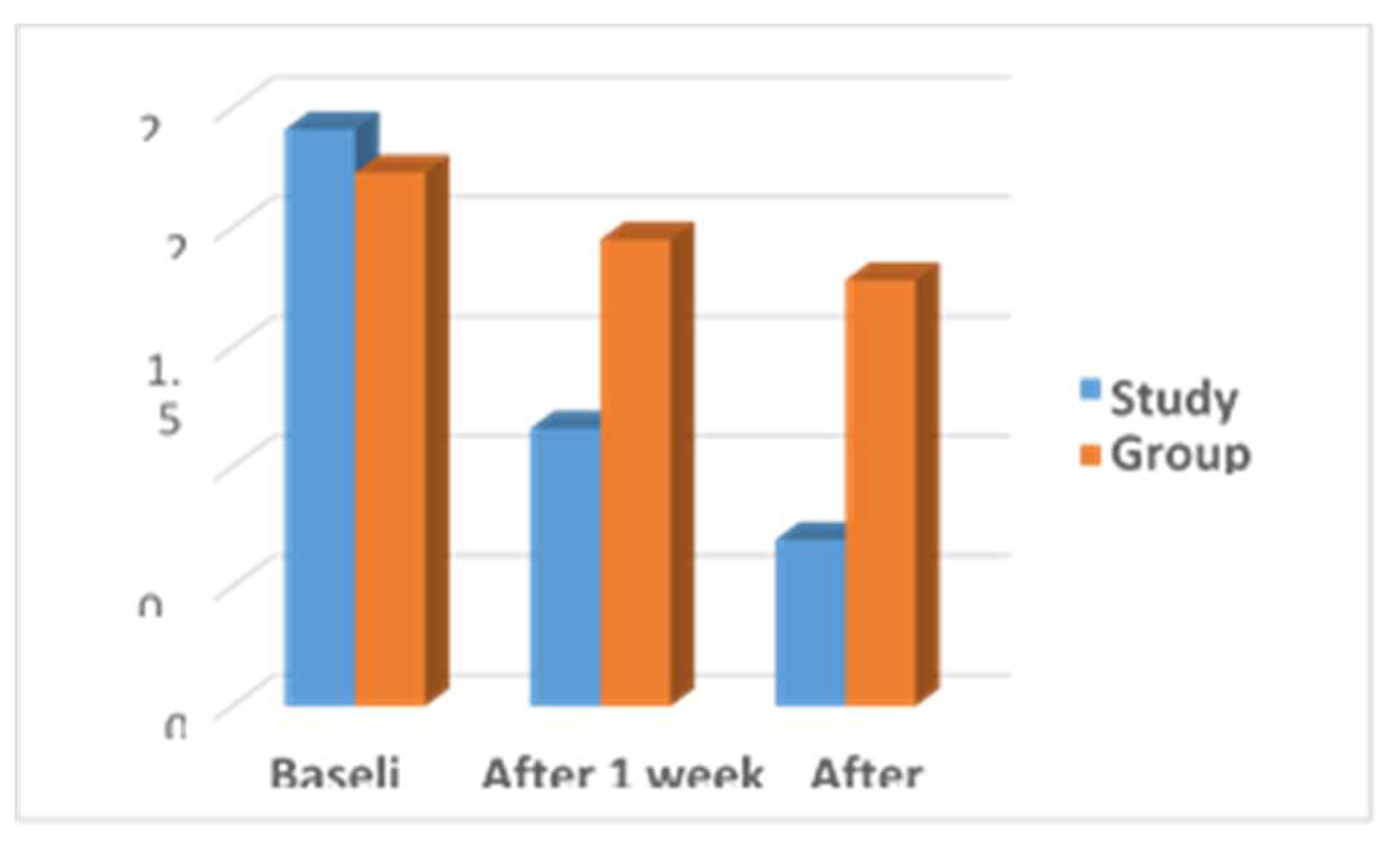

| Plaque Index score | Study Group Mean ± SD |

Control Group Mean ± SD |

Independent t-test | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 2.41±0.28 | 2.23±0.33 | t=2.32 | 0.06 |

| After 1 week | 1.16±0.38 | 1.95±0.35 | t=19.63 | ≤0.001* |

| After 1 month | 0.695±0.25 | 1.78±0.37 | t=22.29 | ≤0.001* |

| Repeated ANOVA | F=50.049 p ≤0.001* |

F=47.69 p ≤0.001* |

- |

- |

|

Post hoc LSD test |

P1≤0.001* p2≤0.001* p3≤0.001* |

P1≤0.001* p2≤0.001* p3≤0.001* |

- |

- |

| Gingival index score | Study Group Mean ± SD |

Control Group Mean ± SD |

Independent t-test | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 0.942±0.36 | 0.982±0.45 | t=2.52 | 0.06 |

| After 1 week | 0.615±0.23 | 0.958±0.22 |

t=11.71 |

≤0.001* |

| After 1 month | 0.325±0.2 | 0.708±0.43 |

t=21.42 |

≤0.001* |

| Repeated ANOVA | F=61.412 p ≤0.001* |

F=81.4 p≤0.001* |

- |

- |

|

Post hoc LSD test |

P1≤0.001* p2≤0.001* p3≤0.001* |

P1= 0.735 p2≤0.001* p3≤0.001* |

- |

- |

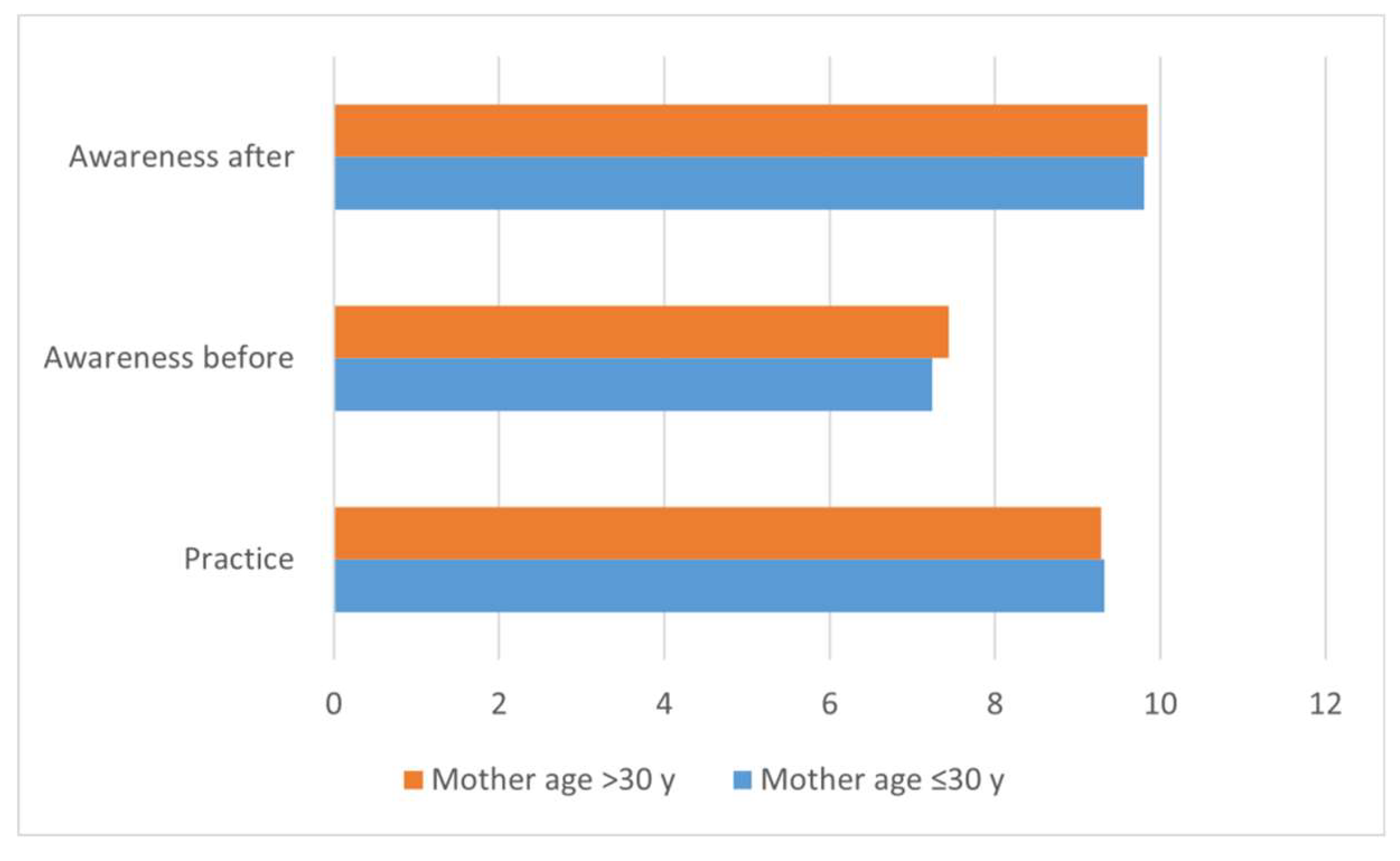

| Items | Practice score | Awareness score at baseline |

Awareness score after one month |

|---|---|---|---|

| other age | |||

|

≤30 y (n=65) >30 y (n=57) |

9.32±2.81 9.28±2.98 |

7.24±1.96 7.44±2.64 |

9.80±2.25 9.84±2.27 |

|

Independent t-test (P value) |

t=0.081 P=0.936 |

t=0.459 P=0.647 |

t=0.102 P=0.919 |

| Items (parameter) | Practice score | |

|---|---|---|

| Raw | P value | |

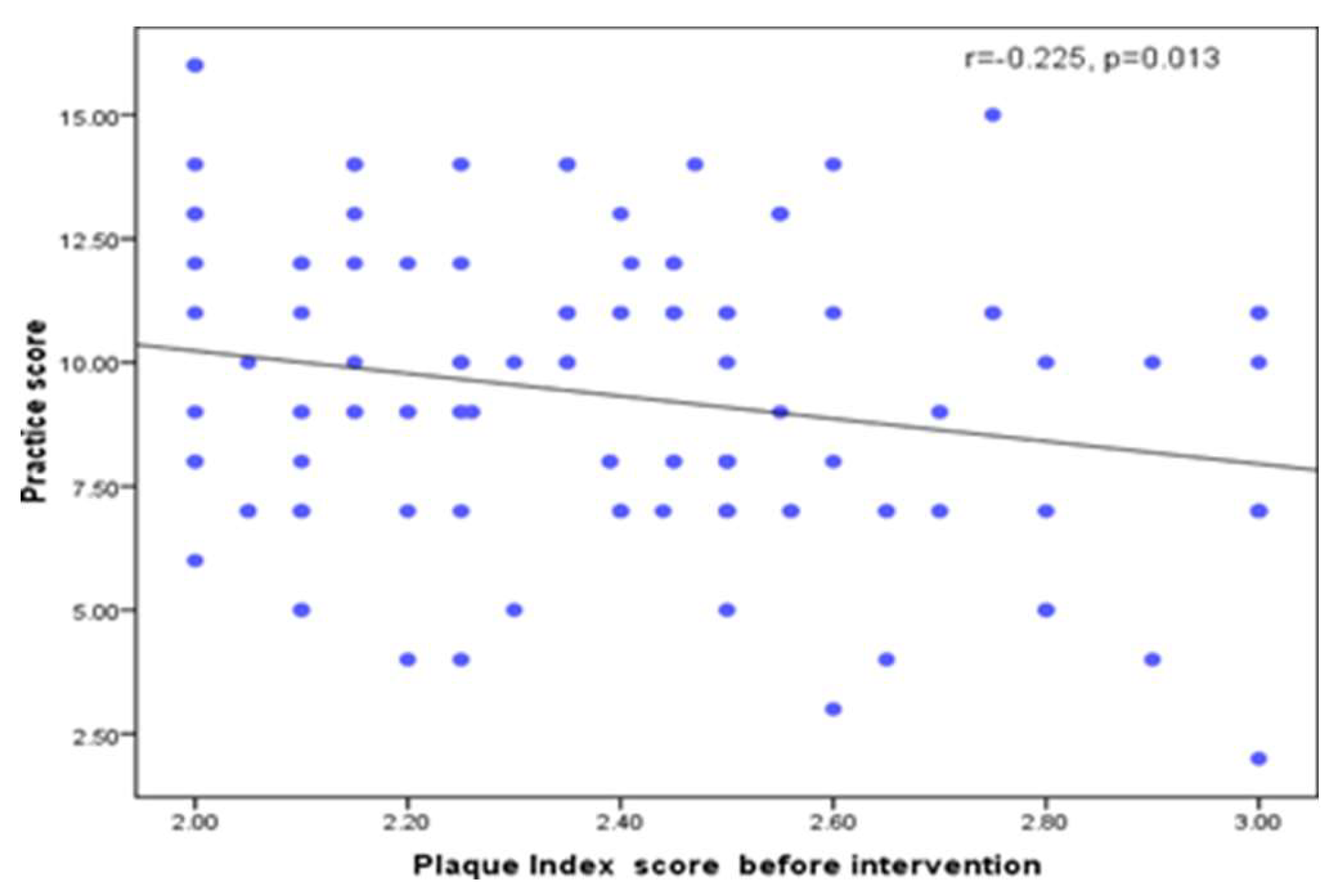

| Plaque index | ||

| Plaque Index score before intervention | -0.225 | 0.013* |

| Plaque Index score after 1 week of using the app | -0.075 | 0.413 |

| Plaque Index score after 1 month of using the app | 0.001 | 0.998 |

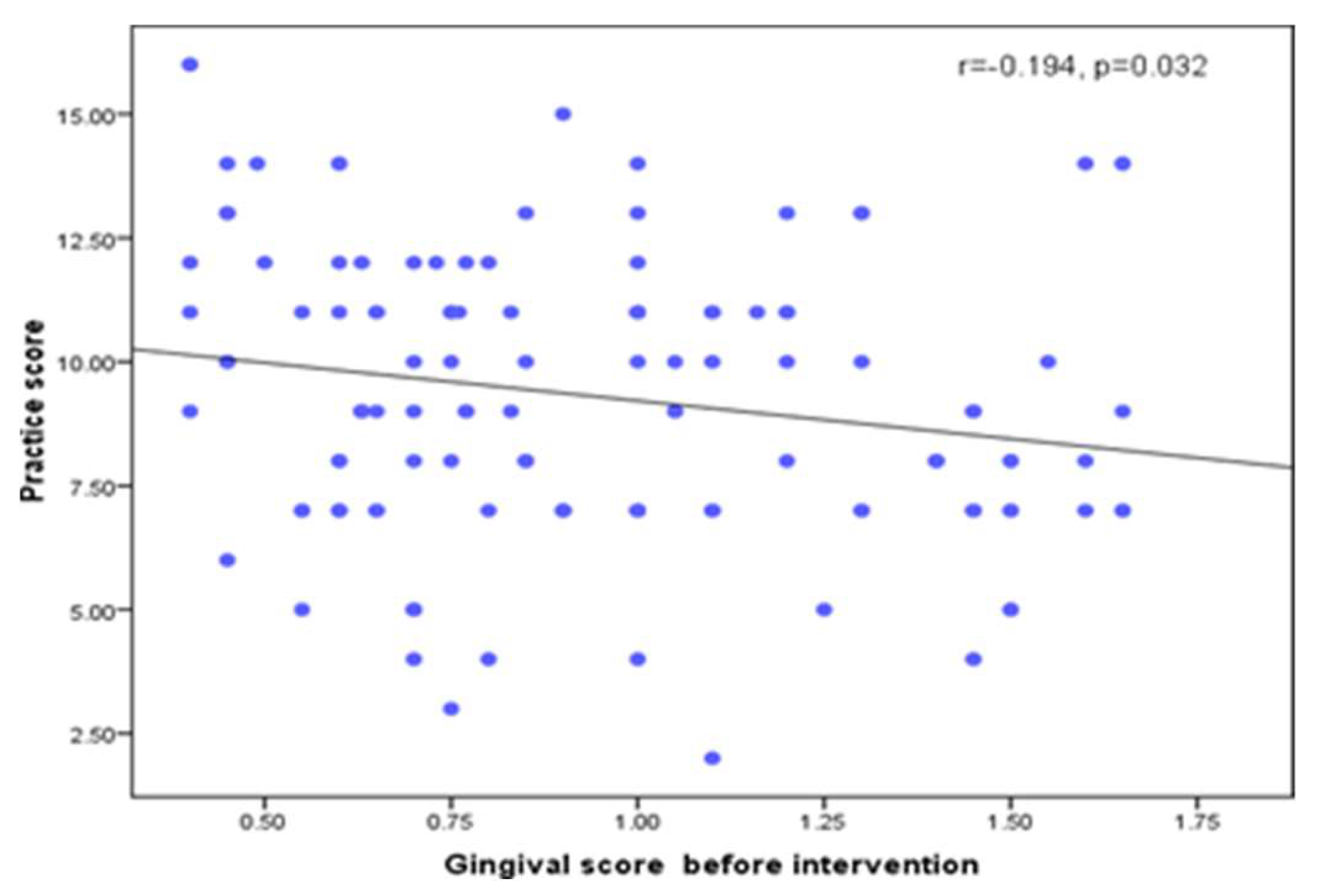

| Gingival Index | ||

| Gingival score before intervention | -0.194 | 0.032* |

| Gingival score after 1 week of using the app | -0.139 | 0.127 |

| Gingival score after 1 month of using the app | -0.074 | 0.417 |

| Demographic data | ||

| Age (Years) | 0.151 | 0.097 |

| Mother age | 0.022 | 0.806 |

| Social class | 0.190 | 0.036* |

|

Moth er education |

0.269 | 0.003* |

| Father education | 0.231 | 0.011* |

| Items | Awareness at baseline | Awareness after one month | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw | P value | Raw | P value | |

| Plaque index | ||||

| Plaque Index score before intervention | -0.066 | 0.472 | 0.066 | 0.472 |

| Plaque Index score after 1 week of using the app | -0.058 | 0.525 | 0.001 | .996 |

| Plaque Index score after 1 month of using the app | 0.049 | 0.300 | -0.095 | 0.300 |

| Gingival index | ||||

| Gingival score before intervention | -0.190 | 0.036* | 0.028 | 0.763 |

| Gingival score after 1 week of using the app | -0.143 | 0.116 | -0.121 | 0.184 |

| Gingival score after 1 month of using the app | -0.061 | 0.507 | -0.134 | 0.142 |

| Demographic data | ||||

| Age (Years) | 0.099 | 0.276 | 0.104 | 0.256 |

| Mother age | 0.122 | 0.181 | 0.069 | 0.452 |

| Social class | 0.133 | 0.145 | 0.040 | 0.660 |

| Mother education | 0.206 | 0.023* | 0.064 | 0.486 |

| Father education | 0.277 | 0.002* | 0.079 | 0.386 |

| Father education | 0.277 | 0.002* | 0.079 | 0.386 |

| Items | Mean plaque index score at baseline | Mean plaque index score after 1 week |

Mean plaque index score after 1 month |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw | P | Raw | P | Raw | P | |

| Age (Years) | 0.005 | 0.952 | 0.123 | 0.179 | 0.120 | 0.189 |

| Mother age | -0.098 | 0.281 | -0.190 | 0.036* | 0.020 | 0.825 |

| Social class | -0.289 | 0.001* | -0.245 | 0.006* | -0.154 | 0.090 |

| Mother education | -0.323 | ≤0.001* | -0.200 | 0.027* | -0.043 | 0.638 |

| Father education | -0.294 | 0.001* | -0.158 | 0.082 | -0.032 | 0.725 |

| Items | Maen gingival index score at baseline | Mean gingival index score after 1 week | Mean gingival index score after 1 month |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw | P | Raw | P | Raw | P | |

| Age (Years) | -0.103 | 0.257 | -0.039 | 0.673 | -0.014 | 0.881 |

| Mother age | -0.158 | 0.083 | -0.197 | 0.03* | -0.031 | 0.731 |

| Social class | -0.381 | ≤0.001* | -0.252 | 0.005* | -0.194 | 0.033* |

| Mother education | -0.494 | ≤0.001* | -0.266 | 0.003* | -0.108 | 0.237 |

| Father education | -0.451 | ≤0.001* | -0.283 | 0.002* | -0.105 | 0.251 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).