Submitted:

14 January 2025

Posted:

14 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

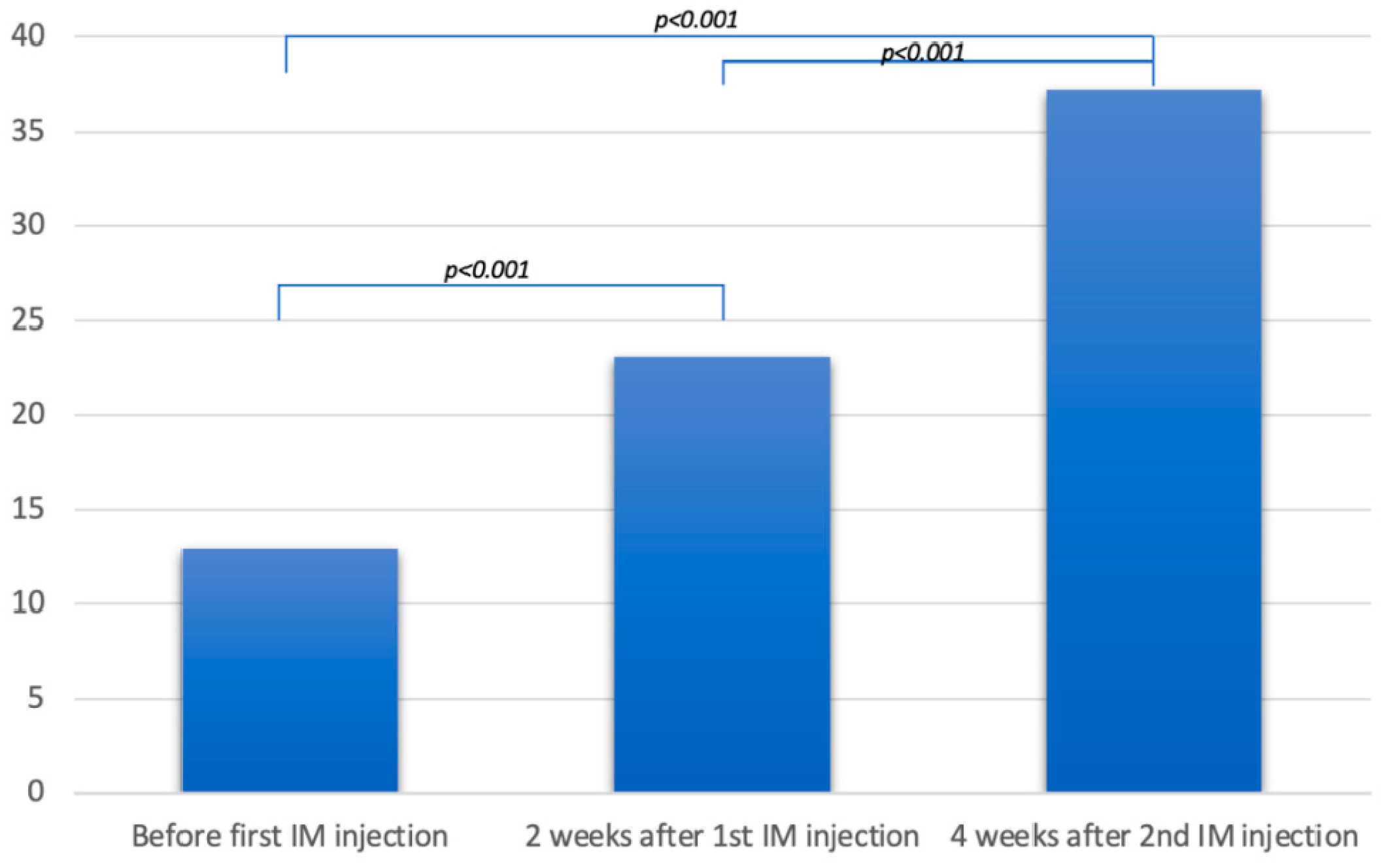

Objective: To assess the response to intramuscular vitamin D in patients not respond-ing to oral supplementation. Methods: A retrospective series included patients, with systemic sclerosis and a history of subclinical poor vitamin D status that was resistant to at least 6 months of oral supplementation, to whom intramuscular vitamin D2 was administered. Results: Twelve patients were identified, with a mean age of 47.8 years. All were women. Five had diffuse systemic sclerosis and seven had localized systemic sclerosis. The mean duration of the disease was 17.9 years, with a mean modified Rod-nan skin score of 14.9. All patients were twice injected, at a 15-day interval, 300,000 IU of ergocalciferol into the anterior gluteus muscle. The mean serum level of 25(OH)D increased from 12.9 ng/mL before the first injection, to 23 ng/mL two weeks after the first injection, and 37.1 ng/mL four weeks after the second injection (p<0.001). No side effects were observed. Conclusion: It is the first report of safely normalizing vitamin D levels with intramuscular ergocalciferol in patients with systemic sclerosis.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Patients

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Protocol

2.4. Measurement of Serum 25(OH)D

2.5. Statistical Analysis

2.6. Patient Consent

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Consent to participate

Written Consent for publication

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- van den Hoogen F, Khanna D, Fransen J, Johnson SR, Baron M, Tyndall A, et al. 2013 classification criteria for systemic sclerosis: an American College of Rheumatology/European League against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Arthritis Rheum 2013;65:2737–47. [CrossRef]

- Giuggioli D, Colaci M, Cassone G, Fallahi P, Lumetti F, Spinella A, et al. Serum 25-OH vitamin D levels in systemic sclerosis: analysis of 140 patients and review of the literature. Clin Rheumatol 2017;36:583–90. [CrossRef]

- Diaconu A-D, Ostafie I, Ceasovschih A, Șorodoc V, Lionte C, Ancuța C, et al. Role of Vitamin D in Systemic Sclerosis: A Systematic Literature Review. J Immunol Res 2021;2021:9782994. [CrossRef]

- Kechichian E, Ezzedine K. Vitamin D and the Skin: An Update for Dermatologists. Am J Clin Dermatol 2018;19:223–35. [CrossRef]

- Chen TC, Chimeh F, Lu Z, Mathieu J, Person KS, Zhang A, et al. Factors that influence the cutaneous synthesis and dietary sources of vitamin D. Arch Biochem Biophys 2007;460:213–7. [CrossRef]

- Tripkovic L, Lambert H, Hart K, Smith CP, Bucca G, Penson S, et al. Comparison of vitamin D2 and vitamin D3 supplementation in raising serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D status: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr 2012;95:1357–64. [CrossRef]

- Bikle DD. Vitamin D Insufficiency/Deficiency in Gastrointestinal Disorders. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research 2007;22:V50–4. [CrossRef]

- Gannagé-Yared M-H, Chemali R, Sfeir C, Maalouf G, Halaby G. Dietary calcium and vitamin D intake in an adult Middle Eastern population: food sources and relation to lifestyle and PTH. Int J Vitam Nutr Res 2005;75:281–9. [CrossRef]

- Lucas RM, Gorman S, Geldenhuys S, Hart PH. Vitamin D and immunity. F1000Prime Rep 2014;6:118. [CrossRef]

- Wharton B, Bishop N. Rickets. Lancet 2003;362:1389–400. [CrossRef]

- Corrado A, Colia R, Mele A, Di Bello V, Trotta A, Neve A, et al. Relationship between Body Mass Composition, Bone Mineral Density, Skin Fibrosis and 25(OH) Vitamin D Serum Levels in Systemic Sclerosis. PLoS One 2015;10:e0137912. [CrossRef]

- Gupta N, Farooqui KJ, Batra CM, Marwaha RK, Mithal A. Effect of oral versus intramuscular Vitamin D replacement in apparently healthy adults with Vitamin D deficiency. Indian J Endocrinol Metab 2017;21:131–6. [CrossRef]

- Marie I, Ducrotté P, Denis P, Menard J-F, Levesque H. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009;48:1314–9. [CrossRef]

- Arnson Y, Amital H, Agmon-Levin N, Alon D, Sánchez-Castañón M, López-Hoyos M, et al. Serum 25-OH vitamin D concentrations are linked with various clinical aspects in patients with systemic sclerosis: a retrospective cohort study and review of the literature. Autoimmun Rev 2011;10:490–4. [CrossRef]

- Trombetta AC, Smith V, Gotelli E, Ghio M, Paolino S, Pizzorni C, et al. Vitamin D deficiency and clinical correlations in systemic sclerosis patients: A retrospective analysis for possible future developments. PLoS One 2017;12:e0179062. [CrossRef]

- An L, Sun M-H, Chen F, Li J-R. Vitamin D levels in systemic sclerosis patients: a meta-analysis. Drug Des Devel Ther 2017;11:3119–25. [CrossRef]

- Artaza JN, Norris KC. Vitamin D reduces the expression of collagen and key profibrotic factors by inducing an antifibrotic phenotype in mesenchymal multipotent cells. J Endocrinol 2009;200:207–21. [CrossRef]

- Gorman S, Zafirau MZ, Lim EM, Clarke MW, Dhamrait G, Fleury N, et al. High-Dose Intramuscular Vitamin D Provides Long-Lasting Moderate Increases in Serum 25-Hydroxvitamin D Levels and Shorter-Term Changes in Plasma Calcium. J AOAC Int 2017;100:1337–44. [CrossRef]

- Zhang L, Duan Y, Zhang T-P, Huang X-L, Li B-Z, Ye D-Q, et al. Association between the serum level of vitamin D and systemic sclerosis in a Chinese population: a case control study. Int J Rheum Dis 2017;20:1002–8. [CrossRef]

- Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 1992;1:98–101. [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi A, Gupta B, Tiwari S, Pratyush DD, Singh S, Singh SK. Parenteral vitamin D supplementation is superior to oral in vitamin D insufficient patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab Syndr 2017;11 Suppl 1:S373–5. [CrossRef]

- Mechanick JI, Apovian C, Brethauer S, Garvey WT, Joffe AM, Kim J, et al. CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINES FOR THE PERIOPERATIVE NUTRITION, METABOLIC, AND NONSURGICAL SUPPORT OF PATIENTS UNDERGOING BARIATRIC PROCEDURES - 2019 UPDATE: COSPONSORED BY AMERICAN ASSOCIATION OF CLINICAL ENDOCRINOLOGISTS/AMERICAN COLLEGE OF ENDOCRINOLOGY, THE OBESITY SOCIETY, AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR METABOLIC & BARIATRIC SURGERY, OBESITY MEDICINE ASSOCIATION, AND AMERICAN SOCIETY OF ANESTHESIOLOGISTS - EXECUTIVE SUMMARY. Endocr Pract 2019;25:1346–59. [CrossRef]

- Sanders KM, Seibel MJ. Therapy: New findings on vitamin D3 supplementation and falls - when more is perhaps not better. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2016;12:190–1. [CrossRef]

- Camacho PM, Petak SM, Binkley N, Diab DL, Eldeiry LS, Farooki A, et al. AMERICAN ASSOCIATION OF CLINICAL ENDOCRINOLOGISTS/AMERICAN COLLEGE OF ENDOCRINOLOGY CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINES FOR THE DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT OF POSTMENOPAUSAL OSTEOPOROSIS-2020 UPDATE. Endocr Pract 2020;26:1–46. [CrossRef]

- Fassio A, Adami G, Rossini M, Giollo A, Caimmi C, Bixio R, et al. Pharmacokinetics of Oral Cholecalciferol in Healthy Subjects with Vitamin D Deficiency: A Randomized Open-Label Study. Nutrients 2020;12:E1553. [CrossRef]

- Wylon K, Drozdenko G, Krannich A, Heine G, Dölle S, Worm M. Pharmacokinetic Evaluation of a Single Intramuscular High Dose versus an Oral Long-Term Supplementation of Cholecalciferol. PLoS One 2017;12:e0169620. [CrossRef]

- Yu SB, Lee Y, Oh A, Yoo H-W, Choi J-H. Efficacy and safety of parenteral vitamin D therapy in infants and children with vitamin D deficiency caused by intestinal malabsorption. Ann Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 2020;25:112–7. [CrossRef]

- Choi HS, Chung Y-S, Choi YJ, Seo DH, Lim S-K. Efficacy and safety of vitamin D3 B.O.N intramuscular injection in Korean adults with vitamin D deficiency. Osteoporos Sarcopenia 2016;2:228–37. [CrossRef]

| Patient | Age (years) | Sex | SSc type | Disease duration (years) |

Modified Rodnan skin score | Previous cure with oral vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) | Serum level of 25(OH)D (ng/mL) | ||||

| Dose (IU/week) | Duration (months) | Before the first IM injection | 2 weeks after the first IM injection | 4 weeks after the second IM injection | |||||||

| 1 | 50 | F | systemic | 17 | 22 | 10.000 | 6 | 12 | 27 | 41 | |

| 2 | 54 | F | localized | 21 | 12 | 10.000 | 6 | 09 | 21 | 47 | |

| 3 | 62 | F | systemic | 30 | 28 | 10.000 | 6 | 14 | 23 | 34 | |

| 4 | 41 | F | localized | 10 | 8 | 10.000 | 6 | 12 | 30 | 47 | |

| 5 | 49 | F | localized | 18 | 10 | 10.000 | 6 | 21 | 29 | 36 | |

| 6 | 60 | F | localized | 25 | 13 | 10.000 | 6 | 10 | 21 | 45 | |

| 7 | 40 | F | systemic | 15 | 18 | 10.000 | 6 | 12 | 25 | 39 | |

| 8 | 43 | F | systemic | 17 | 20 | 10.000 | 6 | 11 | 21 | 31 | |

| 9 | 51 | F | localized | 28 | 15 | 10.000 | 6 | 6 | 15 | 29 | |

| 10 | 35 | F | systemic | 12 | 12 | 10.000 | 8 | 18 | 22 | 32 | |

| 11 | 49 | F | localized | 13 | 8 | 10.000 | 6 | 15 | 21 | 29 | |

| 12 | 39 | F | localized | 9 | 13 | 10.000 | 7 | 15 | 22 | 36 | |

| Mean | 47.8 | 17.9 | 14.9 | 6 | 12.9 | 23 | 37.1 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).