Submitted:

13 January 2025

Posted:

15 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most frequent cardiac arrhythmia with an estimated five million cases globally. This condition increases the likelihood of developing cardiovascular complications such as thromboembolic events, with a fivefold increase in risk of both heart failure and stroke. Contempo-rary challenges include better understanding AF pathophysiology, and optimizing therapeutical options, due to current lack of efficacy and adverse effects of anti-arrhythmic drug therapy. Hence, the identification of novel biomarkers in biological samples would greatly impact the diagnostic and therapeutic opportunities offered to AF patients. Long non-coding RNAs, micro RNAs, circular RNAs and genes involved in heart cell differentiation are particularly relevant to understanding gene regulatory effects on AF pathophysiology. Proteomic remodelling may also play an important role in the structural, electrical, ion channel and interactome dysfunctions associate with AF patho-genesis. Different devices for processing RNA and proteomic samples vary from RNA sequencing, microarray to a wide range of mass spectrometry techniques such as Orbitrap, Quadrupole, LC-MS and hybrid systems. Since AF atrial tissue samples require a more invasive approach to be retrieved and analysed, blood plasma biomarkers were also considered. A range of different sample pre-processing techniques and bioinformatic methods across studies were examined. The objective of this descriptive review is to examine the most recent developments of transcriptomics, proteomics and bioinformatics in Atrial Fibrillation.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

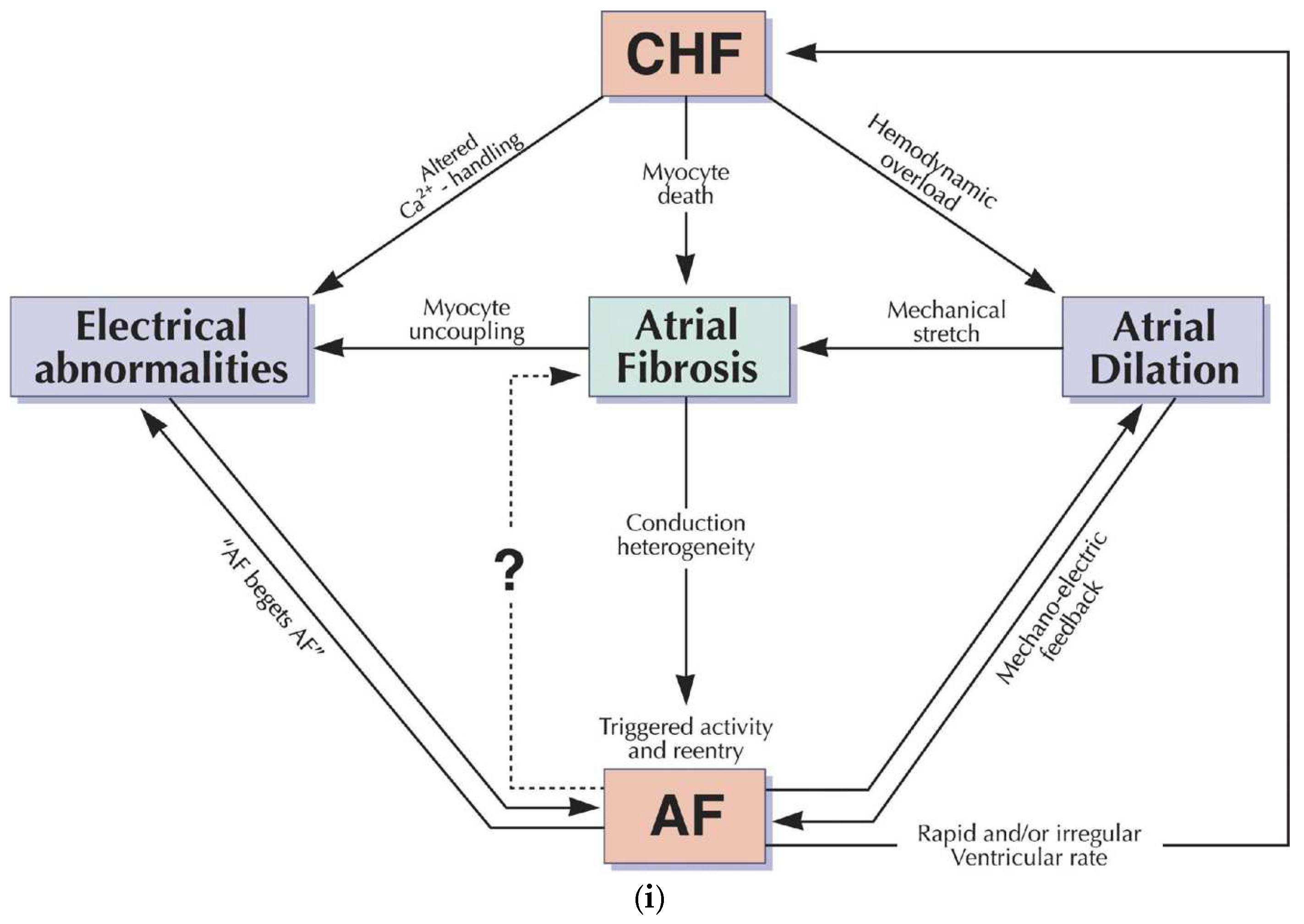

2. Relationship of Biomarkers with AF Pathogenesis

2.1. Transcriptomics

2.1.1. PITX2 (Paired-like Homeodomain Transcription Factor 2)

2.1.2. BMP10 (Bone Morphogenetic Protein 10)

2.1.3. LncRNA

2.1.4. miRNAs

2.1.5. circRNAs

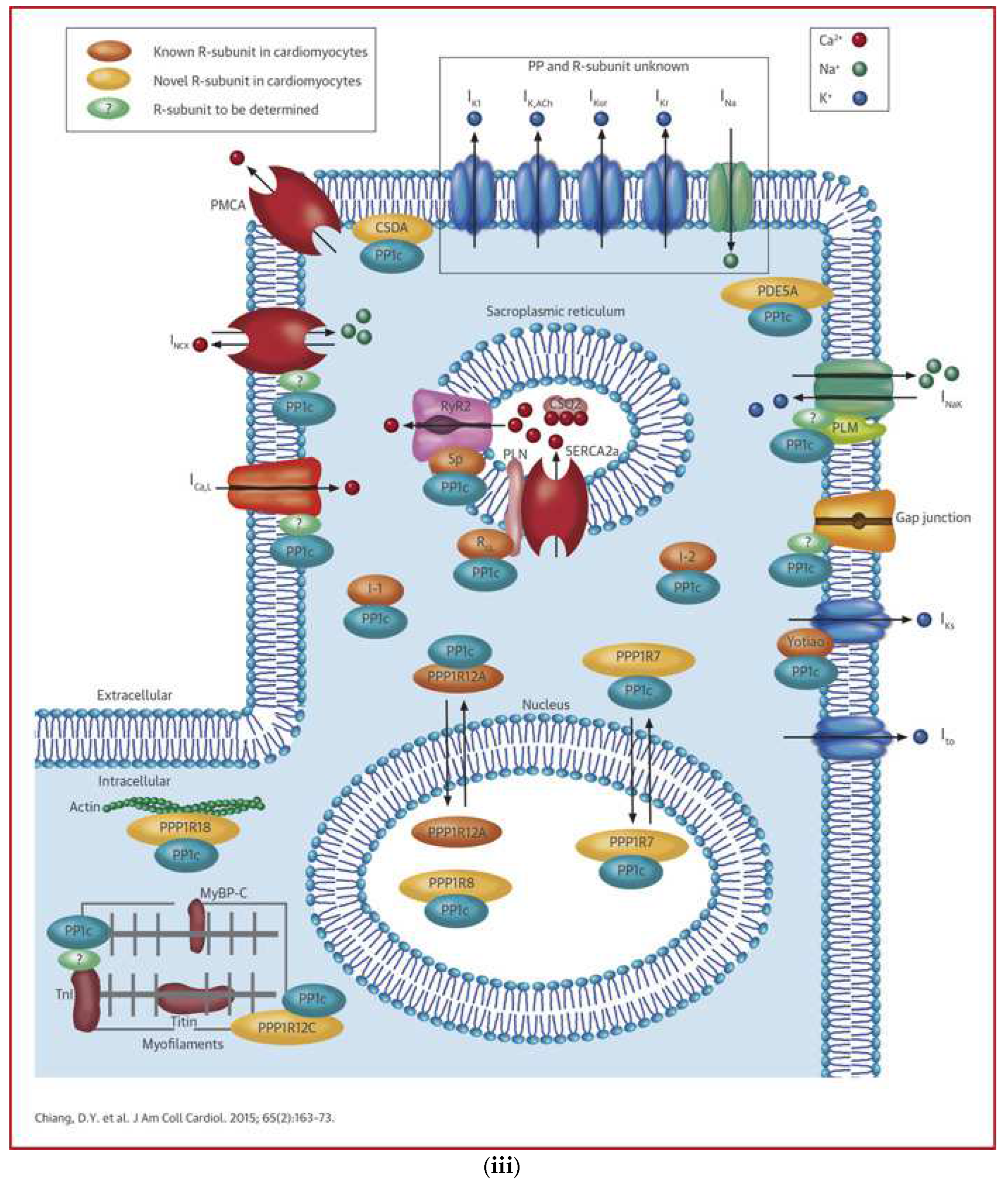

2.2. Proteomics

2.3. Sarcomeric Proteins

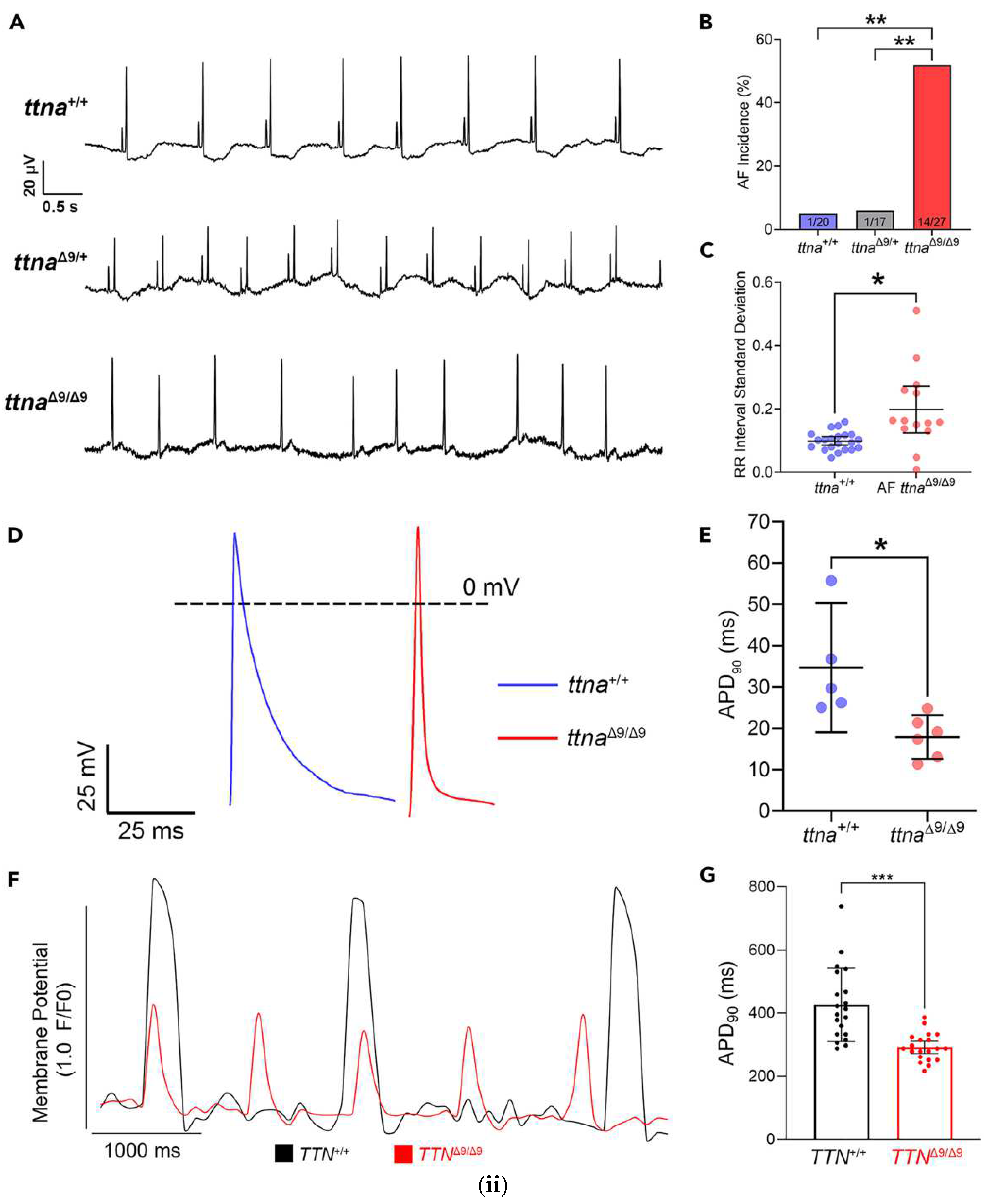

2.3.1. Titin

2.3.2. Myosin Heavy Chain 6,7 (MYH6, MYH7)

2.3.3. Myomesin

2.4. Cadherin and Connexin

2.5. Decorin

2.5.1. AF Related Ion Channels

2.5.2. Miscellaneous

Endolysosomal Proteins

Citrate Synthase

IGFs and IGFBPs

BNP

3. Sample Processing Devices and Technologies

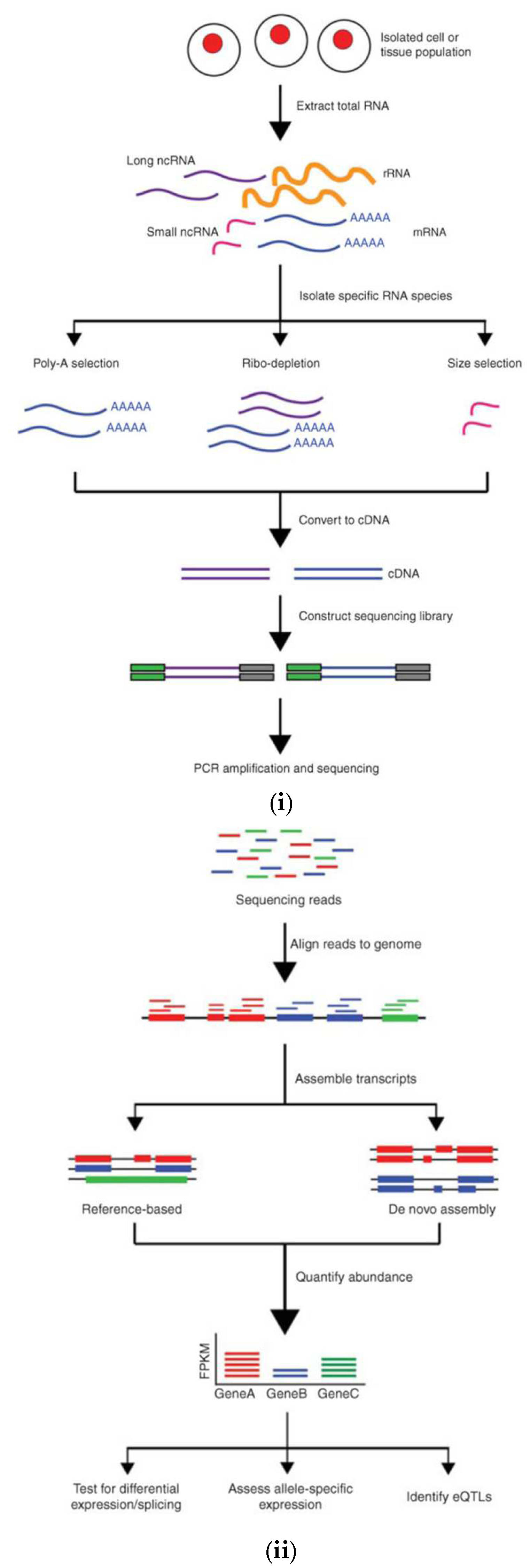

3.1. Transcriptomics

| Omics | Tissue type | Device | Study reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transcriptomics | Atrial tissue | RNA-sequence based: - Illumina NovaSeq -Illumina HiSeq |

[21] [8,22] |

| Microarray Platforms: - Affymetrix GeneChip - Agilent Microarrays |

[20,23] [4] |

||

| Blood plasma | RNA-Sequence based: - Illumina NovaSeq |

[17] | |

| Microarray platforms: - Agilent Microarray |

[39] | ||

| Proteomics | Atrial tissue | Orbitrap based systems | [2,9,22,26,27,28,29,30] |

| TOF based systems | [8,31] |

3.2. Proteomics

4. Statistical Transformations and Tests Applied for Datasets

5. Bioinformatic Packages, Tools or Methods

| Statistical analysis techniques | Dimensionality reduction techniques | Principal Component Analysis (PCA) | [9] |

| Multiple Co-inertia Analysis | [22] | ||

| Parametric tests | Paired t-test | [4,19,23,30] | |

| Unpaired t-test (Student’s t-test) | [19,23,27,29,30] | ||

| Nonparametric tests | Mann-Whitney U test | [2,15,20,26,30] | |

| Kruskal-Wallis test | [26] | ||

| Normality tests | Shapiro-Wilk test | [2,15,26] | |

| Kolmogorov-Smirnov test | [15] | ||

| Multivariate analysis | One and two-way ANOVA tests | [4,8,23,30] | |

| Post Hoc analysis | Bonferroni correction | [23,25,30] | |

| Benjamini-Hochberg method | [2,19,24] | ||

| Regression models | Cox proportional hazard | [15,24,25] | |

| Logistic regression | [15,19,24] | ||

| Bioinformatics packages, tools and methods | Functional Enrichment Analysis | Gene Ontology | [17,22,31] |

| KEGG | [17,26,31,39] | ||

| Limma | [21,26] | ||

| DESeq2 | [15,21] | ||

| Cytoscape | [17,39] | ||

| Cytohubba | [17] | ||

| Metascape | [21] | ||

| DAVID | [17] |

6. Conclusions and Future Perspective

References

- Global epidemiology of atrial fibrillation: An increasing epidemic and public health challenge’. Accessed: Oct. 22, 2024. Available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/epdf/10.1177/1747493019897870?src=getftr&utm_source=sciencedirect_contenthosting&getft_integrator=sciencedirect_contenthosting.

- Kawasaki, M.; Meulendijks, E.R.; Berg, N.W.E.v.D.; Nariswari, F.A.; Neefs, J.; Wesselink, R.; Baalman, S.W.E.; Jongejan, A.; Schelfhorst, T.; Piersma, S.R.; et al. Neutrophil degranulation interconnects over-represented biological processes in atrial fibrillation. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elsheikh, S.; Hill, A.; Irving, G.; Lip, G.Y.; Abdul-Rahim, A.H. Atrial fibrillation and stroke: State-of-the-art and future directions. Curr. Probl. Cardiol. 2023, 49, 102181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooley, N.; Cowley, M.J.; Lin, R.C.Y.; Marasco, S.; Wong, C.; Kaye, D.M.; Dart, A.M.; Woodcock, E.A. Influence of atrial fibrillation on microRNA expression profiles in left and right atria from patients with valvular heart disease. Physiol. Genom. 2012, 44, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burdett, P.; Lip, G.Y.H. Atrial fibrillation in the UK: predicting costs of an emerging epidemic recognizing and forecasting the cost drivers of atrial fibrillation-related costs. Eur. Hear. J. - Qual. Care Clin. Outcomes 2020, 8, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migdady, I.; Russman, A.; Buletko, A.B. Atrial Fibrillation and Ischemic Stroke: A Clinical Review. Semin. Neurol. 2021, 41, 348–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopinathannair, R.; Chen, L.Y.; Chung, M.K.; Cornwell, W.K.; Furie, K.L.; Lakkireddy, D.R.; Marrouche, N.F.; Natale, A.; Olshansky, B.; Joglar, J.A.; et al. Managing Atrial Fibrillation in Patients With Heart Failure and Reduced Ejection Fraction: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circ. Arrhythmia Electrophysiol. 2021, 14, 688–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.-Y.; Hou, H.-T.; Yang, Q.; Liu, X.-C.; He, G.-W. Chloride Channels are Involved in the Development of Atrial Fibrillation – A Transcriptomic and proteomic Study. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 10215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayagama, T.; Charles, P.D.; Bose, S.J.; Boland, B.; Priestman, D.A.; Aston, D.; Berridge, G.; Fischer, R.; Cribbs, A.P.; Song, Q.; et al. Compartmentalization proteomics revealed endolysosomal protein network changes in a goat model of atrial fibrillation. iScience 2024, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagris, M.; Antonopoulos, A.S.; Theofilis, P.; Oikonomou, E.; Siasos, G.; Tsalamandris, S.; Antoniades, C.; Brilakis, E.S.; Kaski, J.C.; Tousoulis, D. Risk factors profile of young and older patients with myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc. Res. 2021, 118, 2281–2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lip, G.Y.; Tse, H.F.; A Lane, D. Atrial fibrillation. Lancet 2011, 379, 648–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, S.S.; Levy, D.; Vasan, R.S.; Wang, T.J. The Framingham Heart Study and the epidemiology of cardiovascular disease: a historical perspective. Lancet 2014, 383, 999–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bizhanov, K.A.; Аbzaliyev, K.B.; Baimbetov, A.K.; Sarsenbayeva, A.B.; Lyan, E. Atrial fibrillation: Epidemiology, pathophysiology, and clinical complications (literature review). J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2022, 34, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hersi, A.; Mitchell, L.B.; Wyse, D.G. Atrial fibrillation: Challenges and opportunities. Can. J. Cardiol. 2006, 22, 21C–26C. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reyat, J.S.; Chua, W.; Cardoso, V.R.; Witten, A.; Kastner, P.M.; Kabir, S.N.; Sinner, M.F.; Wesselink, R.; Holmes, A.P.; Pavlovic, D.; et al. Reduced left atrial cardiomyocyte PITX2 and elevated circulating BMP10 predict atrial fibrillation after ablation. J. Clin. Investig. 2020, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Chen, Y.; Tao, T.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Y.; Luo, J.; Guo, Y. Identification of microRNA biomarkers in serum of patients at different stages of atrial fibrillation. Hear. Lung 2020, 49, 902–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Lu, K.; Wang, Y.; Shi, Y.; Ma, W.; Chen, X.; Li, B.; Shao, Y. Analyses of lncRNA and mRNA profiles in recurrent atrial fibrillation after catheter ablation. Eur. J. Med Res. 2024, 29, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Identification of a long non-coding RNA as a novel biomarker and potential therapeutic target for atrial fibrillation’. Accessed: Nov. 05, 2024. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE64904.

- Zhang, J.; Xu, Y.; Xu, S.; Liu, Y.; Yu, L.; Li, Z.; Xue, X.; Wang, H. Plasma Circular RNAs, Hsa_circRNA_025016, Predict Postoperative Atrial Fibrillation After Isolated Off-Pump Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting. J. Am. Hear. Assoc. 2018, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, O.; Lavall, D.; Theobald, K.; Hohl, M.; Grube, M.; Ameling, S.; Sussman, M.A.; Rosenkranz, S.; Kroemer, H.K.; Schäfers, H.-J.; et al. Rac1-Induced Connective Tissue Growth Factor Regulates Connexin 43 and N-Cadherin Expression in Atrial Fibrillation. Circ. 2010, 55, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, M.C.; Simonson, B.; Roselli, C.; Xiao, L.; Herndon, C.N.; Chaffin, M.; Mantineo, H.; Atwa, O.; Bhasin, H.; Guedira, Y.; et al. Large-scale single-nuclei profiling identifies role for ATRNL1 in atrial fibrillation. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Franco, A.; Rouco, R.; Ramirez, R.J.; Guerrero-Serna, G.; Tiana, M.; Cogliati, S.; Kaur, K.; Saeed, M.; Magni, R.; Enriquez, J.A.; et al. Transcriptome and proteome mapping in the sheep atria reveal molecular featurets of atrial fibrillation progression. Cardiovasc. Res. 2020, 117, 1760–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, F.-C.; Lin, Y.-C.; Chang, S.-H.; Chang, G.-J.; Hsu, Y.-J.; Lin, Y.-M.; Lee, Y.-S.; Wang, C.-L.; Yeh, Y.-H. Differential left-to-right atria gene expression ratio in human sinus rhythm and atrial fibrillation: Implications for arrhythmogenesis and thrombogenesis. Int. J. Cardiol. 2016, 222, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staerk, L.; Preis, S.R.; Lin, H.; Lubitz, S.A.; Ellinor, P.T.; Levy, D.; Benjamin, E.J.; Trinquart, L. Protein Biomarkers and Risk of Atrial Fibrillation. Circ. Arrhythmia Electrophysiol. 2020, 13, e007607–e007607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, D.; Benson, M.D.; Ngo, D.; Yang, Q.; Larson, M.G.; Wang, T.J.; Trinquart, L.; McManus, D.D.; Lubitz, S.A.; Ellinor, P.T.; et al. Proteomics Profiling and Risk of New-Onset Atrial Fibrillation: Framingham Heart Study. J. Am. Hear. Assoc. 2019, 8, e010976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teng, F.; Han, X.; Yu, P.; Li, P.-B.; Li, H.-H.; Zhang, Y.-L. Time series proteome profile analysis reveals a protective role of citrate synthase in angiotensin II-induced atrial fibrillation. J. Hypertens. 2022, 40, 765–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, D.Y.; Lebesgue, N.; Beavers, D.L.; Alsina, K.M.; Damen, J.M.A.; Voigt, N.; Dobrev, D.; Wehrens, X.H.; Scholten, A. Alterations in the Interactome of Serine/Threonine Protein Phosphatase Type-1 in Atrial Fibrillation Patients. Circ. 2015, 65, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Sun, L.; Chen, L.; Liu, S.; Zhong, L.; Cui, M. Comprehensive metabolomic and proteomic analyses reveal candidate biomarkers and related metabolic networks in atrial fibrillation. Metabolomics 2019, 15, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barallobre-Barreiro, J.; Gupta, S.K.; Zoccarato, A.; Kitazume-Taneike, R.; Fava, M.; Yin, X.; Werner, T.; Hirt, M.N.; Zampetaki, A.; Viviano, A.; et al. Glycoproteomics Reveals Decorin Peptides With Anti-Myostatin Activity in Human Atrial Fibrillation. Circulation 2016, 134, 817–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Ly, O.T.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Z.; Ibarra, B.A.; Pavel, M.A.; Brown, G.E.; Sridhar, A.; Tofovic, D.; Swick, A.; et al. Transient titin-dependent ventricular defects during development lead to adult atrial arrhythmia and impaired contractility. iScience 2024, 27, 110395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.-K.; Teng, S.; Bai, F.; Liao, X.-B.; Zhou, X.-M.; Liu, Q.-M.; Xiao, Y.-C.; Zhou, S.-H. Changes of ubiquitylated proteins in atrial fibrillation associated with heart valve disease: proteomics in human left atrial appendage tissue. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 10, 1198486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PubChem, ‘PITX2 - paired like homeodomain 2 (human)’. Accessed: Nov. 20, 2024. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/PITX2/human.

- Kirchhof, P.; Kahr, P.C.; Kaese, S.; Piccini, I.; Vokshi, I.; Scheld, H.-H.; Rotering, H.; Fortmueller, L.; Laakmann, S.; Verheule, S.; et al. PITX2c Is Expressed in the Adult Left Atrium, and Reducing Pitx2c Expression Promotes Atrial Fibrillation Inducibility and Complex Changes in Gene Expression. Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 2011, 4, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syeda, F.; Kirchhof, P.; Fabritz, L. PITX2-dependent gene regulation in atrial fibrillation and rhythm control. J. Physiol. 2017, 595, 4019–4026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BMP10 bone morphogenetic protein 10 [Homo sapiens (human)] - Gene - NCBI’. Accessed: Nov. 20, 2024. [Online]. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/27302.

- Winters, J.; Kawczynski, M.J.; Gilbers, M.D.; Isaacs, A.; Zeemering, S.; Bidar, E.; Maesen, B.; Rienstra, M.; van Gelder, I.; Verheule, S.; et al. Circulating BMP10 Levels Associate With Late Postoperative Atrial Fibrillation and Left Atrial Endomysial Fibrosis. JACC: Clin. Electrophysiol. 2024, 10, 1326–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papait, R.; Kunderfranco, P.; Stirparo, G.G.; Latronico, M.V.G.; Condorelli, G. Long Noncoding RNA: a New Player of Heart Failure? J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 2013, 6, 876–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Y.; Yang, M.; Liu, D.; Zhao, Q. Immune remodeling and atrial fibrillation. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 927221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Huang, R.; Gu, J.; Jiang, W. Identification of long non-coding RNAs as novel biomarker and potential therapeutic target for atrial fibrillation in old adults. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 10803–10811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divakaran, V.; Mann, D.L. The Emerging Role of MicroRNAs in Cardiac Remodeling and Heart Failure. Circ. Res. 2008, 103, 1072–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saliminejad, K.; Khorram Khorshid, H.R.; Soleymani Fard, S.; Ghaffari, S.H. An overview of microRNAs: Biology, functions, therapeutics, and analysis methods. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 5451–5465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duisters, R.F.; Tijsen, A.J.; Schroen, B.; Leenders, J.J.; Lentink, V.; van der Made, I.; Herias, V.; van Leeuwen, R.E.; Schellings, M.W.; Barenbrug, P.; et al. miR-133 and miR-30 regulate connective tissue growth factor: Implications for a role of microRNAs in myocardial matrix remodeling. Circ. Res. 2009, 104, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Tsitsiou, E.; Herrick, S.E.; Lindsay, M.A. MicroRNAs and the regulation of fibrosis. FEBS J. 2010, 277, 2015–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junior, A.d.S.M.; Ferreira, L.C.; Barbosa, L.J.V.; Silva, D.d.M.e.; Saddi, V.A.; Silva, A.M.T.C. Circulating MicroRNAs as Specific Biomarkers in Atrial Fibrillation: A Meta-Analysis. Non-Coding RNA 2023, 9, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, C.; Tan, C.; Liu, X. Circular RNAs: a new frontier in the study of human diseases. J. Med Genet. 2016, 53, 359–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kristensen, L.S.; Andersen, M.S.; Stagsted, L.V.W.; Ebbesen, K.K.; Hansen, T.B.; Kjems, J. The biogenesis, biology and characterization of circular RNAs. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2019, 20, 675–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GEO Accession viewer’. Accessed: Dec. 04, 2024. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE133420.

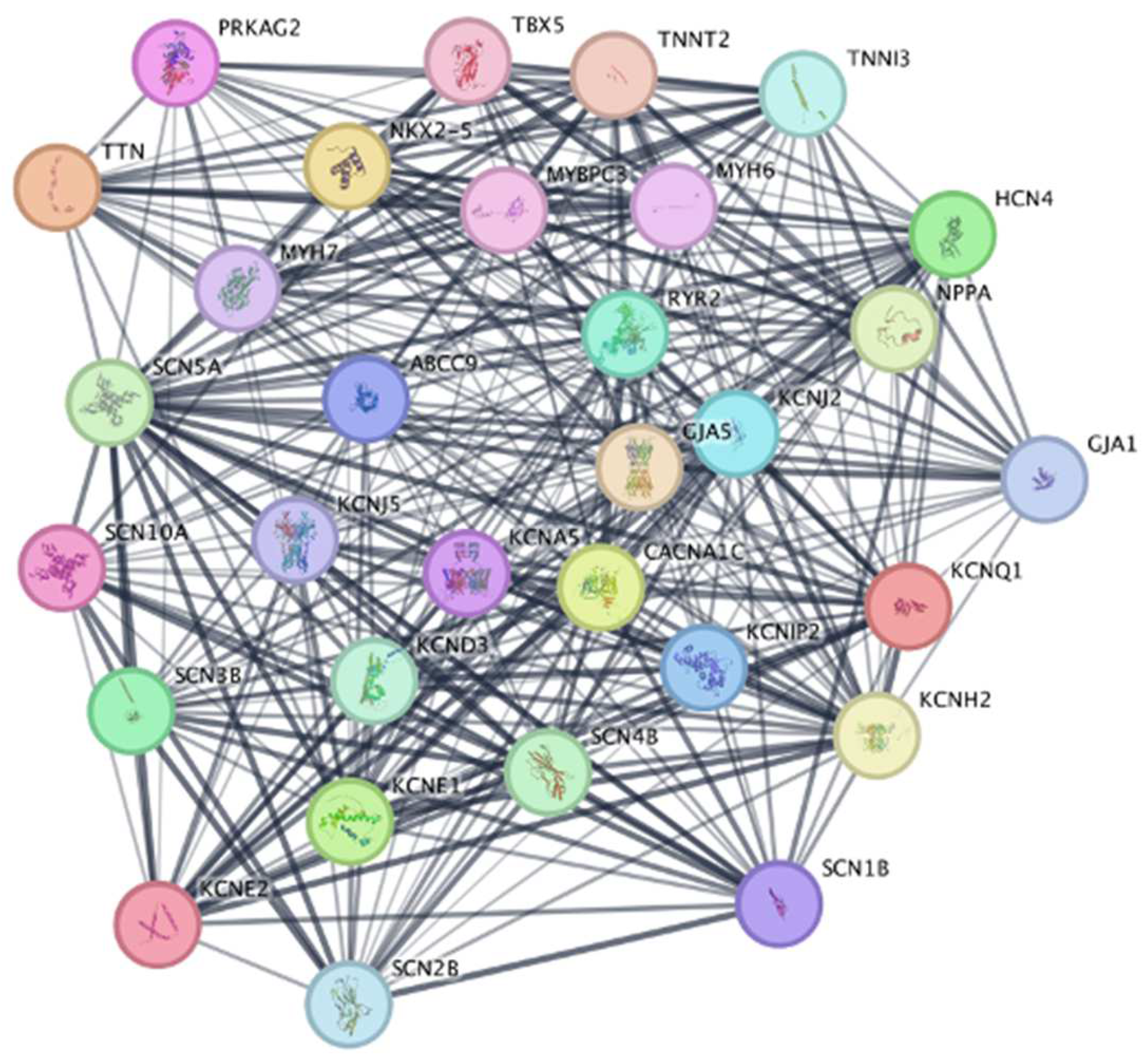

- searching ... STRING: functional protein association networks’. Accessed: Nov. 23, 2024. Available online: https://string-db.org/cgi/network?pollingId=buljH8bHxGoh&sessionId=bkyH6nNi1F4o&urldisam=bzTt2mboak0t.

- Ahlberg, G.; Refsgaard, L.; Lundegaard, P.R.; Andreasen, L.; Ranthe, M.F.; Linscheid, N.; Nielsen, J.B.; Melbye, M.; Haunsø, S.; Sajadieh, A.; et al. Rare truncating variants in the sarcomeric protein titin associate with familial and early-onset atrial fibrillation. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.H.; Weng, L.-C.; Roselli, C.; Lin, H.; Haggerty, C.M.; Shoemaker, M.B.; Barnard, J.; Arking, D.E.; Chasman, D.I.; Albert, C.M.; et al. Association Between Titin Loss-of-Function Variants and Early-Onset Atrial Fibrillation. JAMA 2018, 320, 2354–2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahdavi, V.; Chambers, A.P.; Nadal-Ginard, B. Cardiac alpha- and beta-myosin heavy chain genes are organized in tandem. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1984, 81, 2626–2630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.P. Factors controlling cardiac myosin-isoform shift during hypertrophy and heart failure. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2007, 43, 388–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenauer, R.; Lange, S.; Hirschy, A.; Ehler, E.; Perriard, J.-C.; Agarkova, I. Myomesin 3, a Novel Structural Component of the M-band in Striated Muscle. J. Mol. Biol. 2008, 376, 338–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burstein, B.; Nattel, S. Atrial Fibrosis: Mechanisms and Clinical Relevance in Atrial Fibrillation. Circ. 2008, 51, 802–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrev, D. Electrical Remodeling in Atrial Fibrillation. Herz 2006, 31, 108–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akar, F.G.; Nass, R.D.; Hahn, S.; Cingolani, E.; Shah, M.; Hesketh, G.G.; DiSilvestre, D.; Tunin, R.S.; Kass, D.A.; Tomaselli, G.F. Dynamic changes in conduction velocity and gap junction properties during development of pacing-induced heart failure. Am. J. Physiol. Circ. Physiol. 2007, 293, H1223–H1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akar, F.G.; Spragg, D.D.; Tunin, R.S.; Kass, D.A.; Tomaselli, G.F. Mechanisms Underlying Conduction Slowing and Arrhythmogenesis in Nonischemic Dilated Cardiomyopathy. Circ. Res. 2004, 95, 717–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellman, J.; Lyon, R.C.; Sheikh, F. Extracellular matrix remodeling in atrial fibrosis: Mechanisms and implications in atrial fibrillation. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2009, 48, 461–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Birk, D.E. The regulatory roles of small leucine-rich proteoglycans in extracellular matrix assembly. FEBS J. 2013, 280, 2120–2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burstein, B.; Nattel, S. Atrial Fibrosis: Mechanisms and Clinical Relevance in Atrial Fibrillation. Circ. 2008, 51, 802–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Lv, M.; Cheng, T.; Zhou, Y.; Yuan, G.; Chu, Y.; Luan, Y.; Song, Q.; Hu, Y. Bibliometric analysis of atrial fibrillation and ion channels. Hear. Rhythm. 2024, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Csepe, T.A.; Hansen, B.J.; Dobrzynski, H.; Higgins, R.S.; Kilic, A.; Mohler, P.J.; Janssen, P.M.; Rosen, M.R.; Biesiadecki, B.J.; et al. Molecular Mapping of Sinoatrial Node HCN Channel Expression in the Human Heart. Circ. Arrhythmia Electrophysiol. 2015, 8, 1219–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Y.-L.; Bai, J.; Lin, Q.-Y.; Liu, R.-S.; Yu, X.-H.; Li, H.-H. Immunoproteasome Subunit β5i Promotes Ang II (Angiotensin II)–Induced Atrial Fibrillation by Targeting ATRAP (Ang II Type I Receptor–Associated Protein) Degradation in Mice. Hypertension 2019, 73, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delafontaine, P.; Song, Y.-H.; Li, Y. Expression, Regulation, and Function of IGF-1, IGF-1R, and IGF-1 Binding Proteins in Blood Vessels. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2004, 24, 435–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, C.S.; Chen, M.-H.; Lacey, S.M.; Yang, Q.; Sullivan, L.M.; Xanthakis, V.; Safa, R.; Smith, H.M.; Peng, X.; Sawyer, D.B.; et al. Circulating Insulin-Like Growth Factor-1 and Its Binding Protein-3. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2010, 30, 1479–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnabel, R.B.; Yin, X.; Gona, P.; Larson, M.G.; Beiser, A.S.; McManus, D.D.; Newton-Cheh, C.; A Lubitz, S.; Magnani, J.W.; Ellinor, P.T.; et al. 50 year trends in atrial fibrillation prevalence, incidence, risk factors, and mortality in the Framingham Heart Study: A cohort study. Lancet 2015, 386, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, C.; Xu, Q. Roles of insulin-like growth factor (IGF) binding proteins in regulating IGF actions. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2005, 142, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duron, E.; Vidal, J.-S.; Funalot, B.; Brunel, N.; Viollet, C.; Seux, M.-L.; Treluyer, J.-M.; Epelbaum, J.; Bouc, Y.L.; Hanon, O. Insulin-Like Growth Factor I, Insulin-like Growth factor Binding Protein 3, and Atrial Fibrillation in the Elderly. Journals Gerontol. Ser. A 2013, 69, 1025–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Z.; Jia, Y.; Zhu, B. BNP and NT-proBNP as Diagnostic Biomarkers for Cardiac Dysfunction in Both Clinical and Forensic Medicine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnabel, R.B.; Larson, M.G.; Yamamoto, J.F.; Sullivan, L.M.; Pencina, M.J.; Meigs, J.B.; Tofler, G.H.; Selhub, J.; Jacques, P.F.; Wolf, P.A.; et al. Relations of Biomarkers of Distinct Pathophysiological Pathways and Atrial Fibrillation Incidence in the Community. Circulation 2010, 121, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.J.; Gona, P.; Larson, M.G.; Tofler, G.H.; Levy, D.; Newton-Cheh, C.; Jacques, P.F.; Rifai, N.; Selhub, J.; Robins, S.J.; et al. Multiple Biomarkers for the Prediction of First Major Cardiovascular Events and Death. New Engl. J. Med. 2006, 355, 2631–2639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukurba, K.R.; Montgomery, S.B. RNA Sequencing and Analysis. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2015, 2015, 951–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukurba, K.R.; Montgomery, S.B. RNA Sequencing and Analysis. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2015, 2015, 951–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, S.E.; Boone, B.E. Next-Generation Sequencing Strategies. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2018, 9, a025791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. Dacey, ‘The Illumina Symphony: Unveiling the Pros, Cons, and Diverse Use Cases of Illumina Sequencing Instruments’, Dovetail Biopartners. Accessed: Dec. 28, 2024. Available online: https://dovetailbiopartners.com/2023/08/09/exploring-the-illumina-symphony-unveiling-the-pros-cons-and-diverse-use-cases-of-all-illumina-sequencing-instruments/.

- Modi, A.; Vai, S.; Caramelli, D.; Lari, M. The Illumina Sequencing Protocol and the NovaSeq 6000 System’, Methods Mol. Biol. Clifton NJ, vol. 2242, pp. 15–42, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Illumina Sequencing(2020)’, Genome Sequencing Service Center. Accessed: Dec. 28, 2024. Available online: https://med.stanford.edu/gssc/services/sequencing1.html.

- Illumina HiSeq 2500’. Accessed: Dec. 09, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://genohub.com/ngs-sequencer/14/illumina-hiseq-2500/.

- Bumgarner, R. Overview of DNA Microarrays: Types, Applications, and Their Future. Curr. Protoc. Mol. Biol. 2013, 101, 22.1.1–22.1.11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Affymetrix GeneChip » Microarray and Sequencing Resource | Boston University’. Accessed: Dec. 09, 2024. Available online: https://www.bumc.bu.edu/microarray/services/affymetrix-genechip/.

- Zhang, G.; Annan, R.S.; Carr, S.A.; Neubert, T.A. Overview of Peptide and Protein Analysis by Mass Spectrometry. Curr. Protoc. Protein Sci. 2010, 62, 16.1.1–16.1.30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aebersold, R.; Mann, M. Mass spectrometry-based proteomics. Nature 2003, 422, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mass Spectrometry Techniques and Analysis: An Overview’, BiologyInsights. Accessed: Dec. 07, 2024. Available online: https://biologyinsights.com/mass-spectrometry-techniques-and-analysis-an-overview/.

- Allen, D.; McWhinney, B. Quadrupole Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry: A Paradigm Shift in Toxicology Screening Applications. 2019, 40, 135–146. [CrossRef]

- S. N. Thomas, ‘Chapter 10 - Mass spectrometry’, in Contemporary Practice in Clinical Chemistry (Fourth Edition), W. Clarke and M. A. Marzinke, Eds., Academic Press, 2019, pp. 171–185. [CrossRef]

- M. Yavor, ‘Chapter 8 Time-of-Flight Mass Analyzers’, in Advances in Imaging and Electron Physics, vol. 157, in Optics of Charged Particle Analyzers, vol. 157., Elsevier, 2009, pp. 283–316. [CrossRef]

- J. C. Fjeldsted, ‘Chapter 2 - Advances in Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry’, in Comprehensive Analytical Chemistry, vol. 71, S. Pérez, P. Eichhorn, and D. Barceló, Eds., in Applications of Time-of-Flight and Orbitrap Mass Spectrometry in Environmental, Food, Doping, and Forensic Analysis, vol. 71., Elsevier, 2016, pp. 19–49. [CrossRef]

- P. Eichhorn, S. P. Eichhorn, S. Pérez, and D. Barceló, ‘Chapter 5 - Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry Versus Orbitrap-Based Mass Spectrometry for the Screening and Identification of Drugs and Metabolites: Is There a Winner?’, in Comprehensive Analytical Chemistry, vol. 58, A.R. Fernandez-Alba, Ed., in TOF-MS within Food and Environmental Analysis, vol. 58., Elsevier, 2012, pp. 217–272. [CrossRef]

- Allen, D.; McWhinney, B. Quadrupole Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry: A Paradigm Shift in Toxicology Screening Applications. 2019, 40, 135–146. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.N.; Thomas, S.N.; French, D.; French, D.; Jannetto, P.J.; Jannetto, P.J.; Rappold, B.A.; Rappold, B.A.; Clarke, W.A.; Clarke, W.A. Liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry for clinical diagnostics. Nat. Rev. Methods Prim. 2022, 2, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douglas, D.J.; Frank, A.J.; Mao, D. Linear ion traps in mass spectrometry. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 2004, 24, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, X.; Xie, J.; Chu, S.; Jiang, Y.; An, Y.; Li, C.; Gong, X.; Zhai, R.; Huang, Z.; Qiu, C.; et al. Quadrupole-Linear Ion Trap Tandem Mass Spectrometry System for Clinical Biomarker Analysis. Engineering 2022, 16, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glish, G.L.; Burinsky, D.J. Hybrid mass spectrometers for tandem mass spectrometry. 2011, 19, 161–172. [CrossRef]

- M. Scigelova and D. Kusel, ‘Thermo Scientific LTQ Orbitrap’.

- PS-64391-LC-MS-Orbitrap-Fusion-Lumos-Tribrid-PS64391-EN.pdf’. Accessed: Dec. 14, 2024. Available online: https://assets.thermofisher.com/TFS-Assets/CMD/Specification-Sheets/PS-64391-LC-MS-Orbitrap-Fusion-Lumos-Tribrid-PS64391-EN.pdf.

- T. F. S. Inc, ‘Q Exactive Benchtop Quadrupole-Orbitrap Mass Spectrometer’.

- Busardò, F.P.; Kyriakou, C.; Marchei, E.; Pacifici, R.; Pedersen, D.S.; Pichini, S. Ultra-high performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (UHPLC–MS/MS) for determination of GHB, precursors and metabolites in different specimens: Application to clinical and forensic cases. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2017, 137, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, C.; Noirel, J.; Ow, S.Y.; Salim, M.; Pereira-Medrano, A.G.; Couto, N.; Pandhal, J.; Smith, D.; Pham, T.K.; Karunakaran, E.; et al. An insight into iTRAQ: where do we stand now? Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2012, 404, 1011–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noirel, J.; Evans, C.; Salim, M.; Mukherjee, J.; Ow, S.Y.; Pandhal, J.; Pham, T.K.; Biggs, C.A.; Wright, P.C. Methods in Quantitative Proteomics: Setting iTRAQ on the Right Track. Curr. Proteom. 2011, 8, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duhok Polytechnic University; Hasan, B.M.S.; Abdulazeez, A.M. A Review of Principal Component Analysis Algorithm for Dimensionality Reduction. J. Soft Comput. Data Min. 2021, 02. [CrossRef]

- Greenacre, M.; Groenen, P.J.F.; Hastie, T.; D’enza, A.I.; Markos, A.; Tuzhilina, E. Principal component analysis. Nat. Rev. Methods Prim. 2022, 2, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, E.J.; Long, Q. Sparse multiple co-Inertia analysis with application to integrative analysis of multi -Omics data. BMC Bioinform. 2020, 21, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Fralick, D.; Zheng, J.Z.; Wang, B.; Tu, X.M.; Feng, C. The Differences and Similarities Between Two-Sample T-Test and Paired T-Test., 29, 184–188. [CrossRef]

- Neideen, T.; Brasel, K. Understanding Statistical Tests. J. Surg. Educ. 2007, 64, 93–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.K. T test as a parametric statistic. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 2015, 68, 540–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, P.; Pandey, C.M.; Singh, U.; Gupta, A.; Sahu, C.; Keshri, A. , Descriptive statistics and normality tests for sta-tistical data. Ann. Card. Anaesth. 2019, 22, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nahm, F.S. Nonparametric statistical tests for the continuous data: the basic concept and the practical use. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 2016, 69, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, P.; Singh, U.; Pandey, C.M.; Mishra, P.; Pandey, G. Application of student's t-test, analysis of variance, and covariance. Ann. Card. Anaesth. 2019, 22, 407–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-Y. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) comparing means of more than two groups. Restor. Dent. Endod. 2014, 39, 74–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbangba, C.E.; Aide, E.S.; Honfo, H.; Kakai, R.G. On the use of post-hoc tests in environmental and biological sciences: A critical review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- W. Haynes, ‘Benjamini–Hochberg Method’, in Encyclopedia of Systems Biology, W. Dubitzky, O. Wolkenhauer, K.-H. Cho, and H. Yokota, Eds., New York, NY: Springer, 2013, pp. 78–78. [CrossRef]

- E. Doan, ‘Type I and Type II Error’, in Encyclopedia of Social Measurement, K. Kempf-Leonard, Ed., New York: Elsevier, 2005, pp. 883–888. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.; Chitnis, U.; Jadhav, S.; Bhawalkar, J.; Chaudhury, S. Hypothesis testing, type I and type II errors. Ind. Psychiatry J. 2009, 18, 127–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. L. Hazelton, ‘Univariate Linear Regression’, in International Encyclopedia of Education (Third Edition), P. Peterson, E. Baker, and B. McGaw, Eds., Oxford: Elsevier, 2010, pp. 482–488. [CrossRef]

- DESeq2’, Bioconductor. Accessed: Dec. 28, 2024. Available online: http://bioconductor.org/packages/DESeq2/.

- Smyth, G.K.; Ritchie, M.; Thorne, N.; Wettenhall, J.; Shi, W.; Hu, Y. ‘Linear Models for Microarray and RNA-Seq Data User’s Guide’.

- Kemena, C.; Dohmen, E.; Bornberg-Bauer, E. DOGMA: a web server for proteome and transcriptome quality assessment. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, W507–W510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonidia, R.P.; Domingues, D.S.; Sanches, D.S.; de Carvalho, A.C.P.L.F. MathFeature: feature extraction package for DNA, RNA and protein sequences based on mathematical descriptors. Briefings Bioinform. 2021, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stražar, M.; Žitnik, M.; Zupan, B.; Ule, J.; Curk, T. Orthogonal matrix factorization enables integrative analysis of multiple RNA binding proteins. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, 1527–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Tissue type | Biomarkers | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomics | Blood plasma | ||

| Atrial tissue | |||

| Transcriptomics | Blood plasma | BMP10 | [15] |

| miR-146a-3p, miR-125b-5p, miR-34a-5p, miR-150-3p | [16] | ||

| lncRNA: TMEM51-AS1-201 | [17] | ||

| lncRNA: NONHSAT040387, NONHSAT098586 | [18] | ||

| hsa_circRNA_025016 | [19] | ||

| Atrial tissue | HCN1, AGL | [9] | |

| Rac1, RohA, CTGF, N-cadherin, Cx43 | [20] | ||

| miR-21, miR-146b-5p, miR-133a&b, miR-30 family, miR-10b, miR100 | [4] | ||

| CLIC 1-6 | [8] | ||

| PITX2, BMP10 | [15] | ||

| ATRNL1, KCNN3 | [21] | ||

| PITX2, KCNJ3,5, CACNA1C, SCNA5, TTN, MYOM1 | [22] | ||

| RyR2, SERCA2, IP3R1 | [23] | ||

| Proteomics | Blood plasma | IGF1, IGFBP1, NT-proBNP | [24] |

| ADAMTS13, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide, BMPR1A | [25] | ||

| Atrial tissue | GAA, Rab7a, CTBL, VPS25, CCT2 (endolysosomal complex) | [9] | |

| CLIC 1,4,5, collagen type IV | [8] | ||

| LCN2, MPO, MYH10 | [2] | ||

| OXPHOS complex, citrate synthase | [26] | ||

| PP1c interactome: PPP1R7, CSDA, PDE5A | [27] | ||

| GSS, Decorin | [28,29] | ||

| TTN∆9/∆9 (deletion titin) | [30] | ||

| TTN, MYH6 | [31] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).