Submitted:

14 January 2025

Posted:

14 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

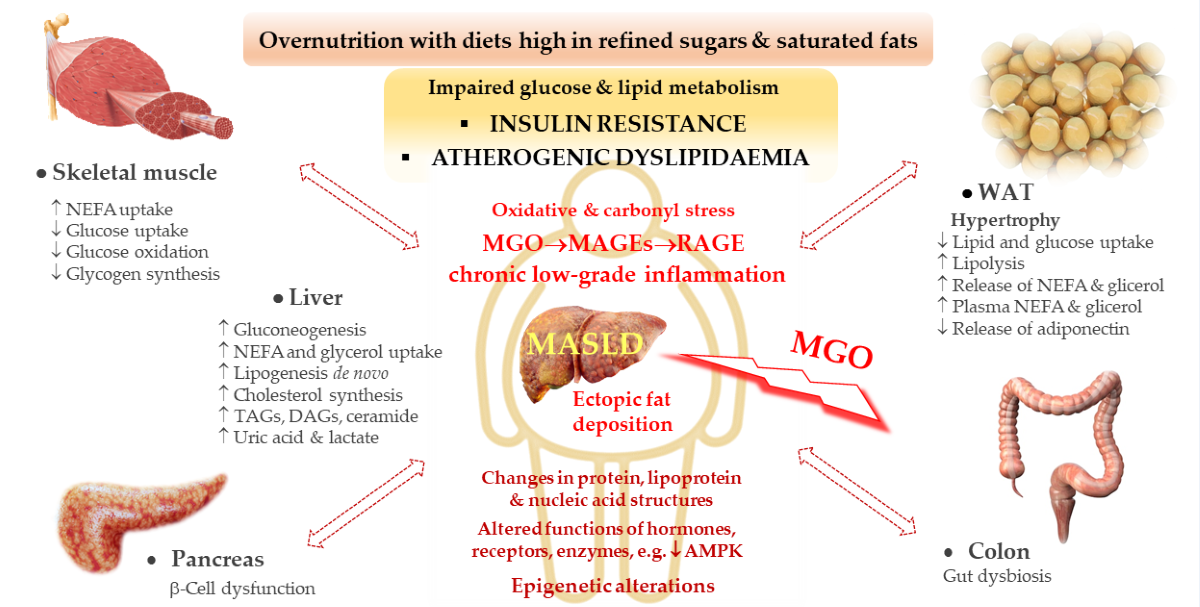

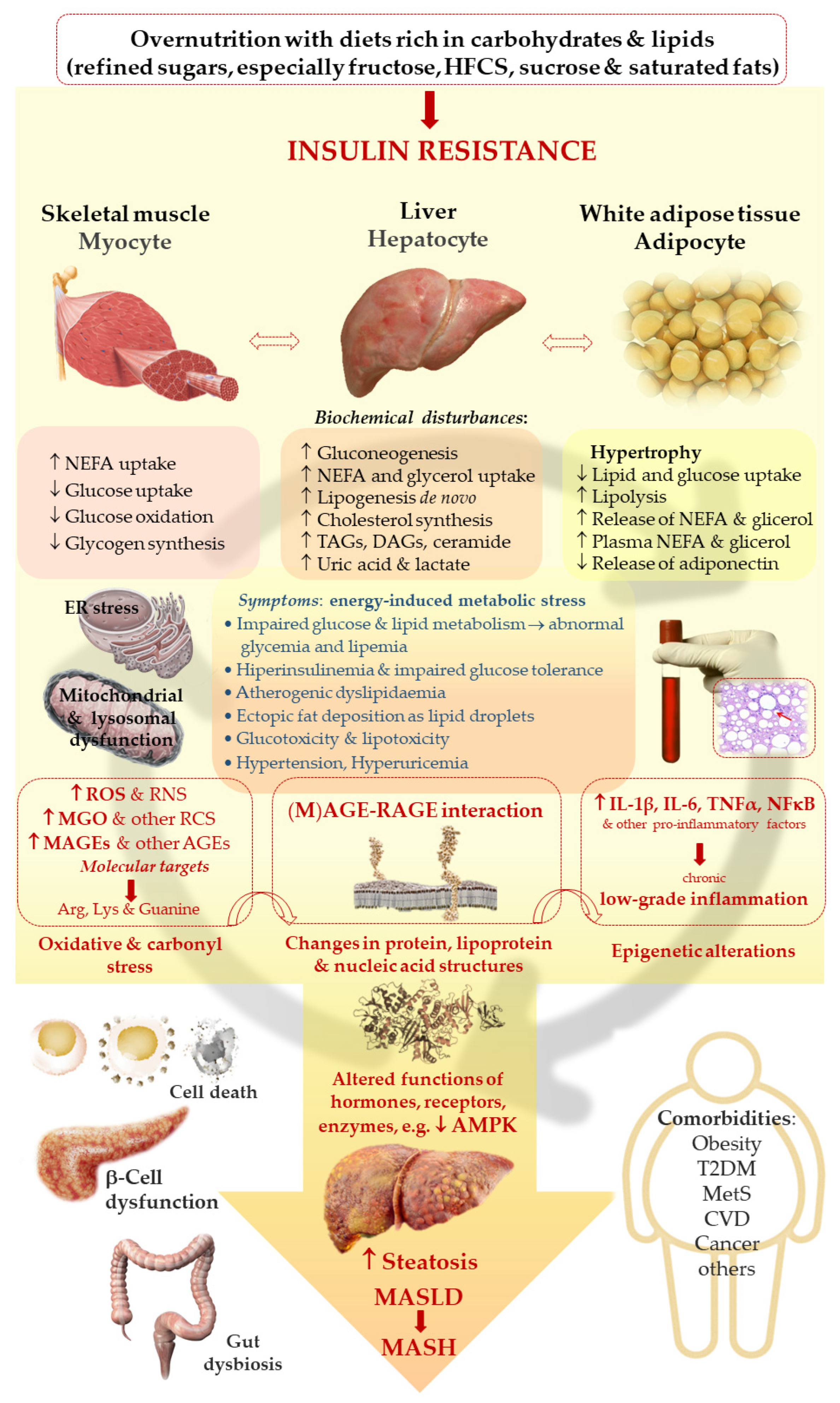

2. Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD)

2.1. Ferroptosis as a Possible Mechanism Contributing to Cell Death in MASLD

2.2. AMP-Activated Protein Kinase as the Major Signaling Node Impaired in MASLD

2.3. Gut-Liver Axis—How Dysfunctional Gastrointestinal Tract (GIT) Affects MASLD and Vice Versa?

2.4. Deleterious Effects of Advanced Glycation End Products Exerted Through the Induction of Their Receptors (Advanced Glycation End Products Receptors) in MASLD

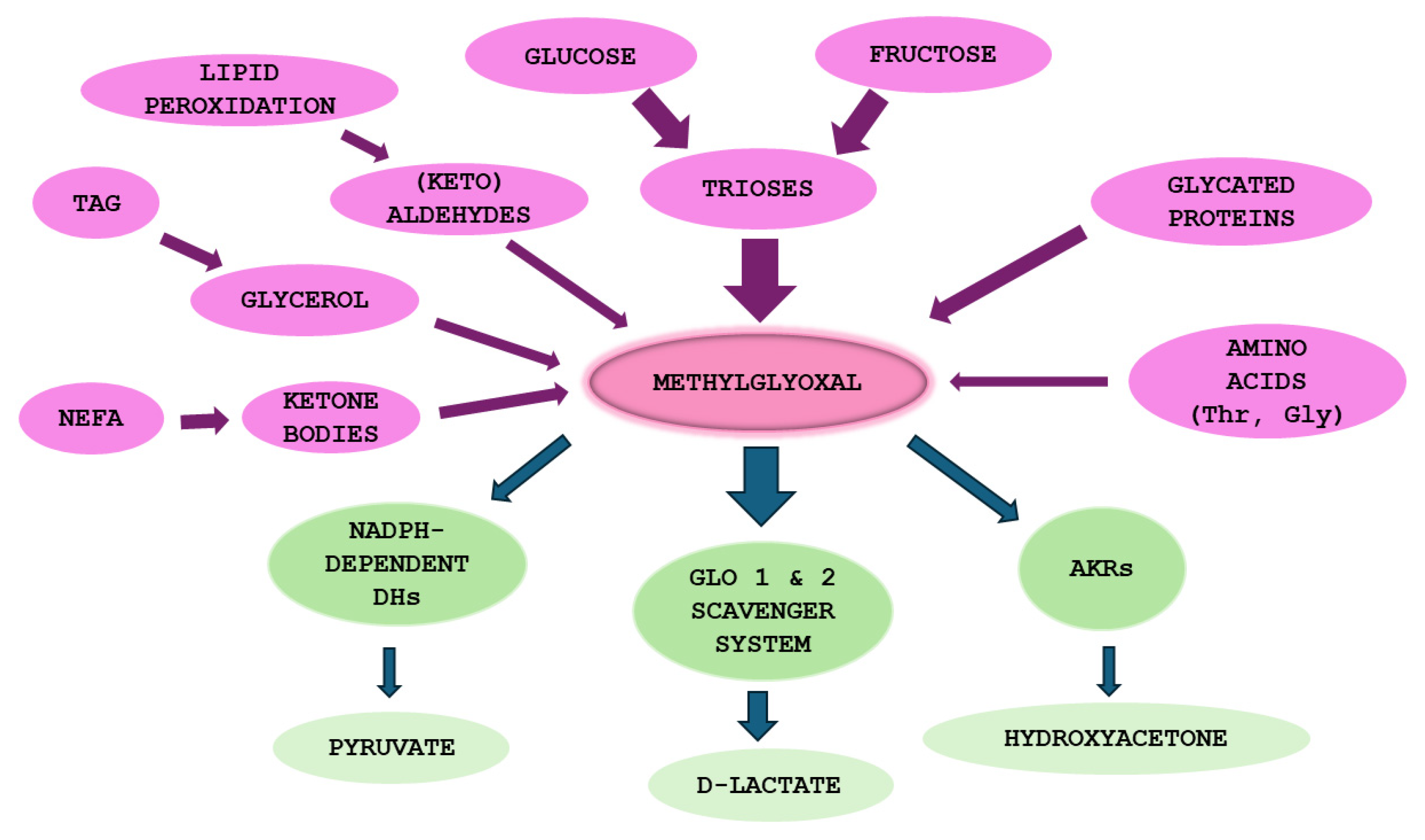

3. Methylglyoxal (MGO)

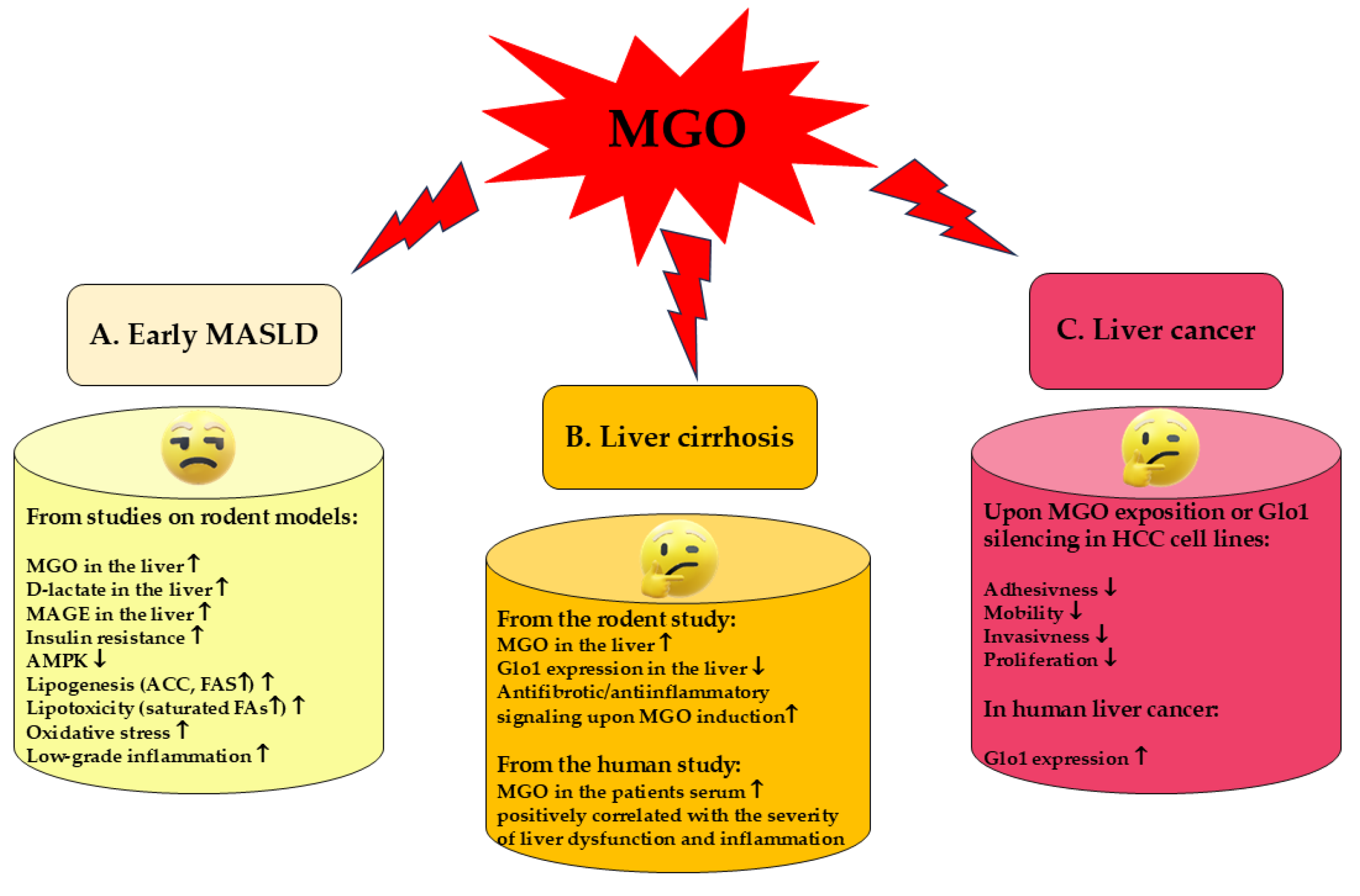

4. MGO in MASLD

4.1. MGO in the Early MASLD

4.2. MGO in Liver Cirrhosis

4.3. MGO in Liver Cancer

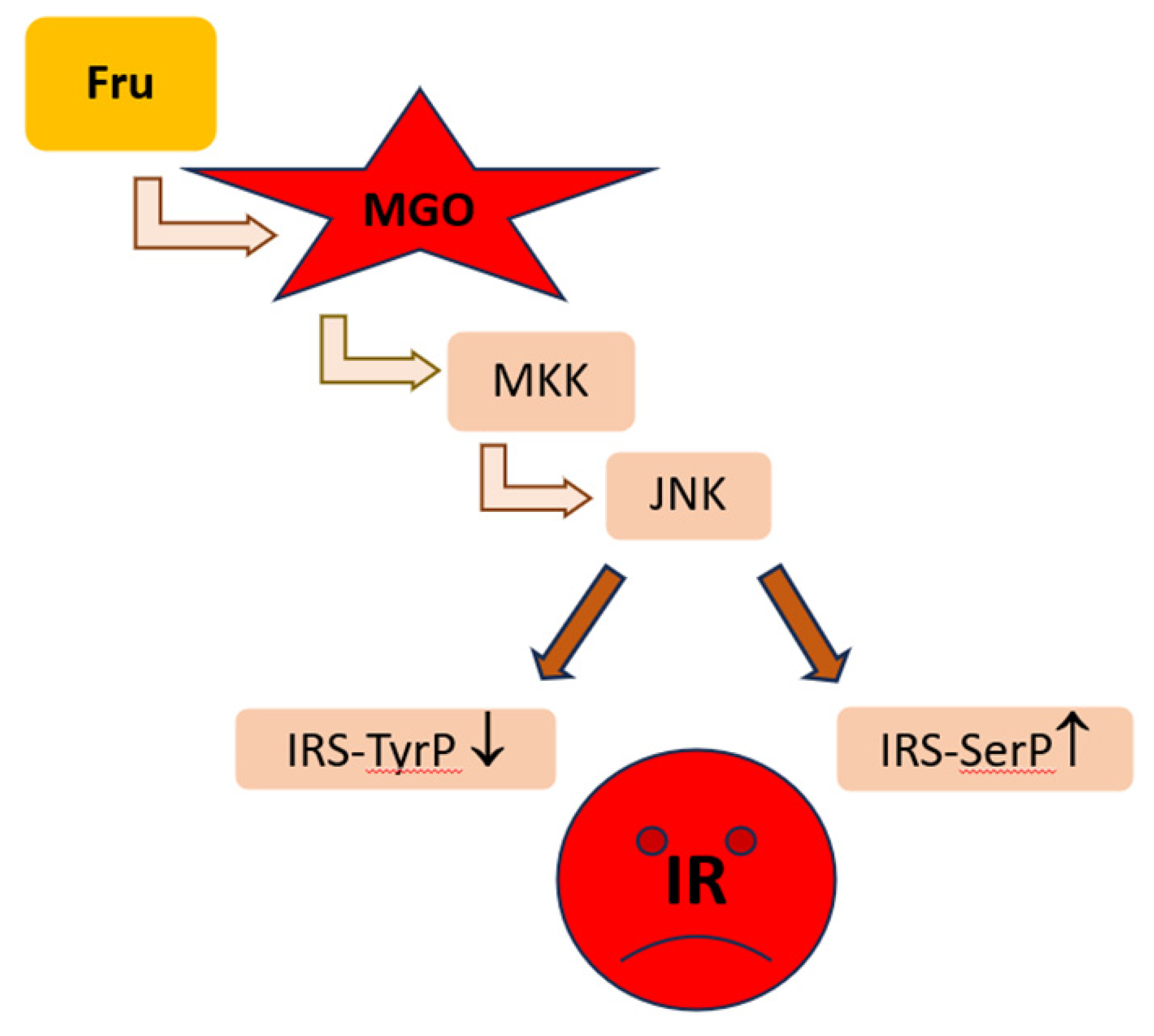

5. Contribution of Fructose-Derived MGO to MASLD Development

6. Approved and Potential Therapies in MASLD

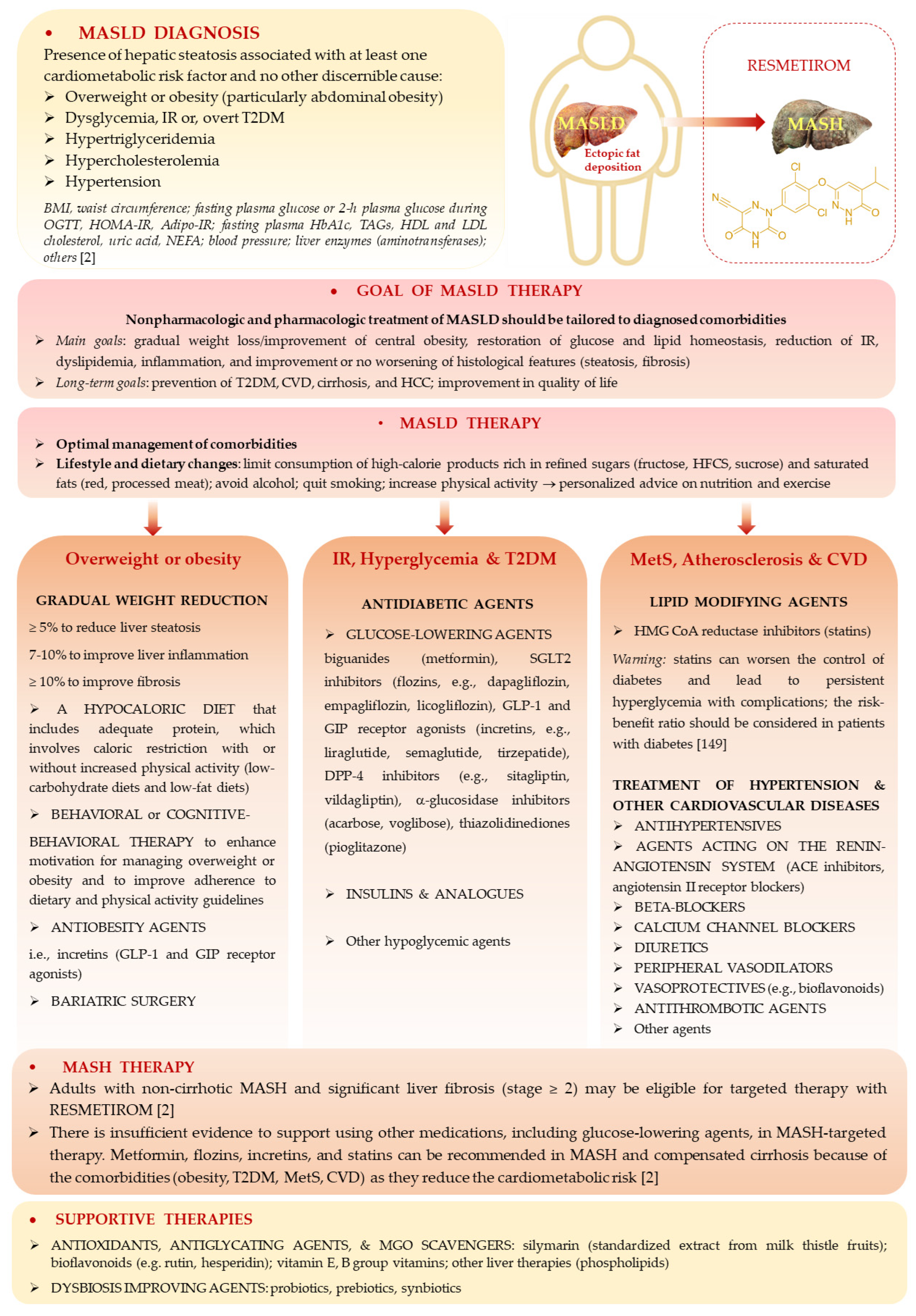

6.1. Recommended Therapies and Medications

6.2. MGO, AGEs, and Gut Microbiota as Therapeutic Targets

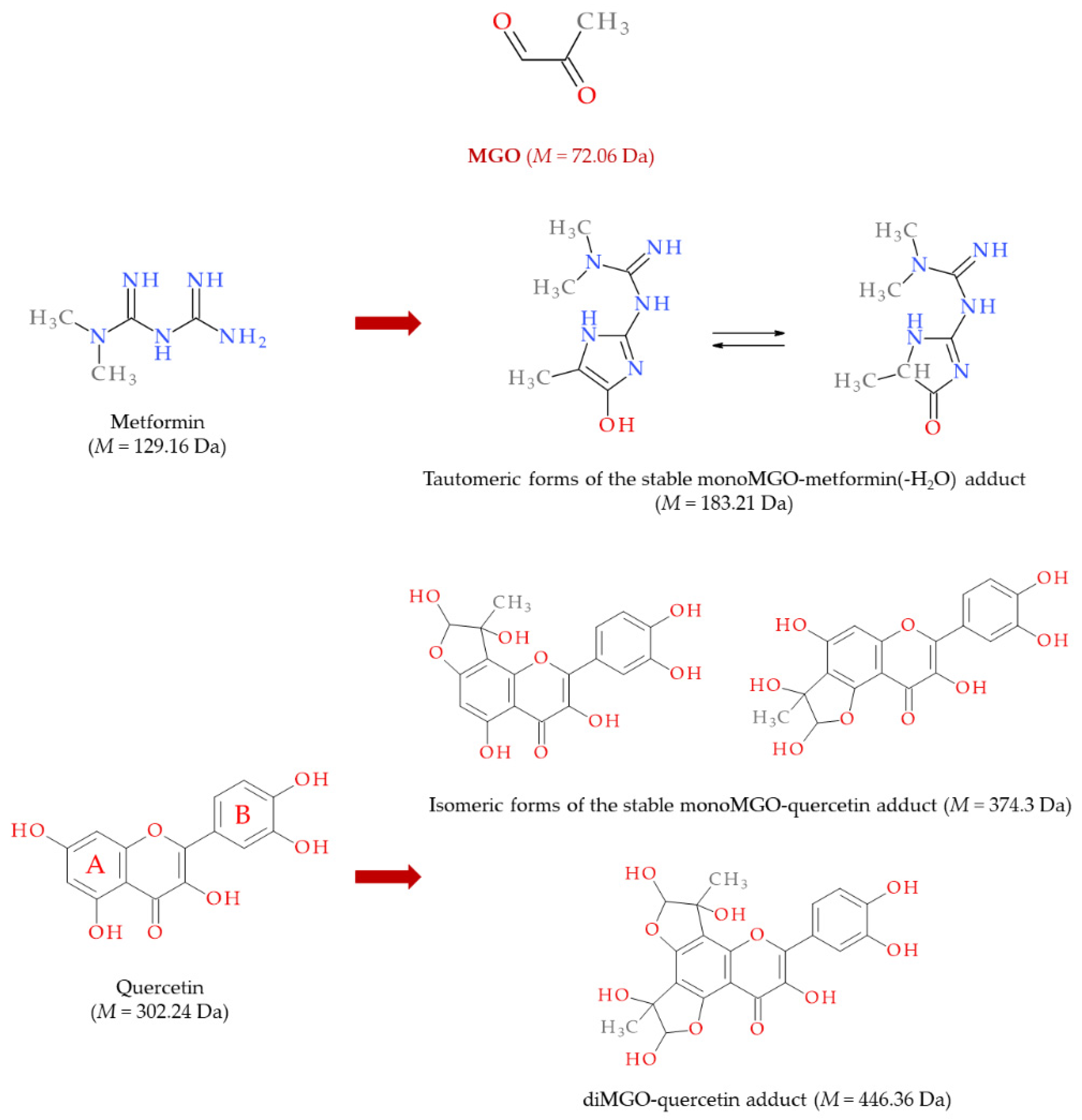

6.3. MASLD Therapy with MGO Scavengers and Antiglycation Agents

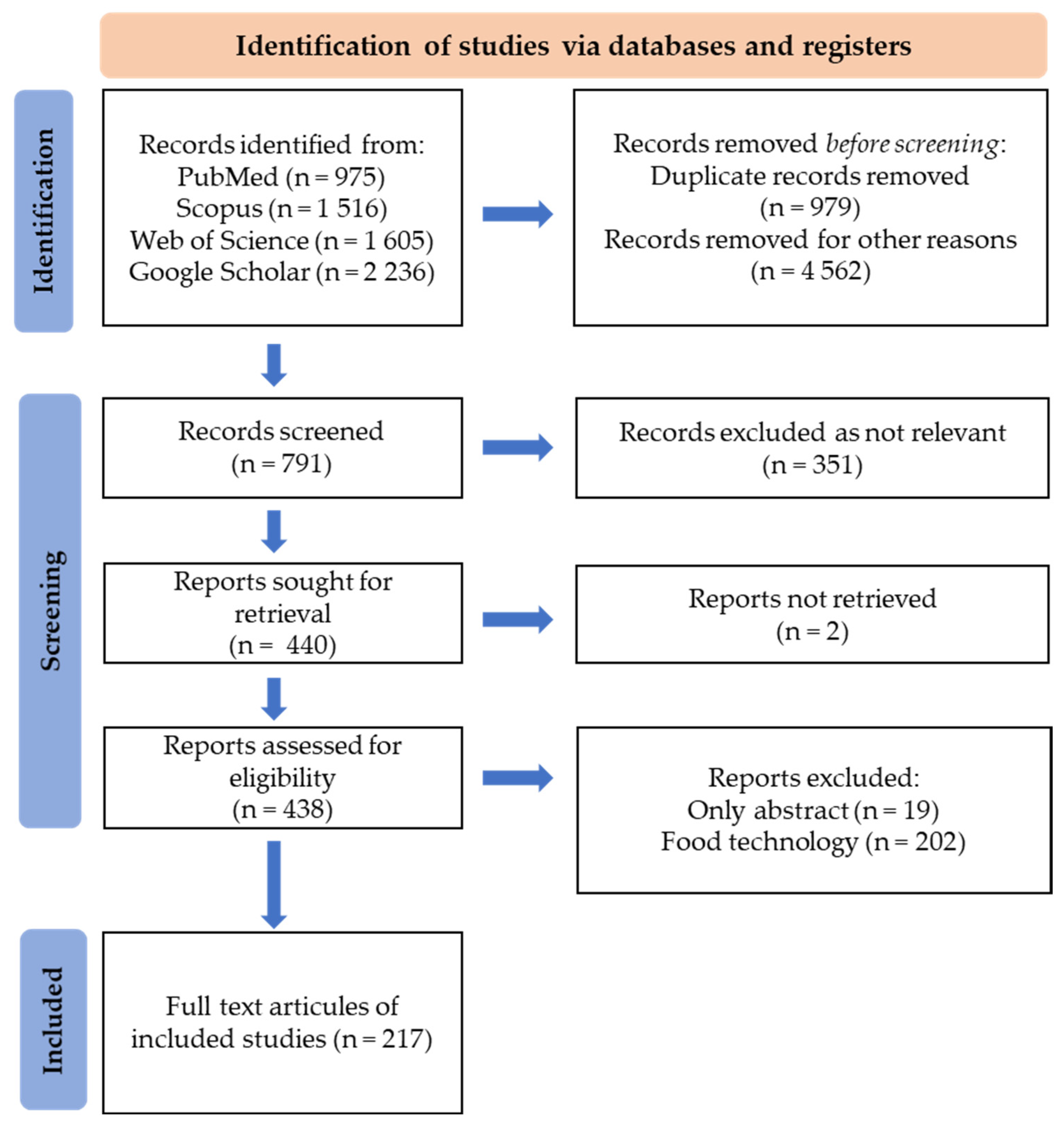

7. Methodology

8. Conclusions and Remarks for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACC | acetyl-CoA carboxylase |

| AceCS | acetyl-CoA synthetase |

| AGEs | advanced glycation end products |

| AIFM2 | factor mitochondria associated 2A |

| ALP | alkaline phosphatase |

| ALT | alanine aminotransferase |

| AMPK | AMP-activated protein kinase |

| ArgP | Argpyrimidine |

| ApoE−/− | apolipoprotein E knockout |

| AST | aspartate aminotransferase |

| AUC | area under the curve |

| α-SMA | alpha-smooth muscle actin |

| BCAA | branched chain amino acids |

| CaMKKβ | Ca21/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase β |

| CCl4 | carbon tetrachloride |

| CD43 | leukosialin (mucin-like protein expressed on the surface of most hematopoietic cells) |

| CEdG | N2-carboxyethyl-20–deoxyguanosine |

| CEL | Nε-(1-carboxyethyl)lysine = N6-(1-carboxyethyl)lysine |

| Chol | Cholesterol |

| ChREBP | carbohydrate-responsive element-binding protein |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| CTGF | connective tissue growth factor |

| CVD | cardiovascular diseases |

| DAGs | Diacylglycerols |

| DAMPs | damage-associated molecular patterns |

| DMT1 | divalent metal transporter 1 |

| DNL | de novo lipogenesis |

| ECM | extracellular matrix |

| FAs | fatty acids |

| FAS | fatty acid synthase |

| Fru | Fructose |

| FXR | farnesoid X receptor |

| GA | Glyceraldehyde |

| GAPDH | glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| GGT | γ-glutamyl transpeptidase |

| GIT | gastrointestinal tract |

| Glc | Glucose |

| Glo1 | glyoxalase 1 |

| Glo2 | glyoxalase 2 |

| GLUT-4 | insulin-dependent glucose transporters in skeletal muscle and adipose tissue |

| GPx | glutathione peroxidase |

| GPX4 | glutathione peroxidase 4 |

| GSH | reduced glutathione |

| GSSG | oxidized glutathione |

| HCC | hepatocellular carcinoma |

| HDL-Chol | high-density lipoproteins cholesterol |

| Hep G2 | epithelial hepatoblastoma cell line |

| HFCS | high-fructose corn syrup |

| HFD | high-fat diet |

| HHTg | hereditary hypertriglyceridemic rats |

| HO | heme oxygenase |

| HOMA | homeostatic model assessment |

| HSCs | hepatic stellate cells |

| IR | insulin resistance |

| IRS-1,2 | insulin receptor substrate 1,2 |

| JNK | c-jun NH2-terminal kinase |

| KCs | Kupffer cells |

| LKB1 | liver kinase B1 |

| LPO | lipid peroxidation |

| LPS | lipopolysaccharide |

| LSECs | liver sinusoidal endothelial cells |

| MAGEs | MGO-derived advanced glycation end products |

| MAPKs | mitogen-activated protein kinases |

| MASLD | metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease |

| MCP-1 | monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 |

| MDA | malondialdehyde |

| MetS | metabolic syndrome |

| MG-dG | 3-(20–deoxyribosyl)-6,7-dihydro-6,7-dihydroxy-6/7-methylimidazo-[2,3-b]purin-9(8)one |

| MG-H1 | Nδ -(5-hydro-5-methyl-4-imidazolon-2-yl)-ornithine |

| MG-H2 | 2-amino-5-(2-amino-5-hydro-5-methyl-4- imidazolon-1-yl)-pentanoic acid |

| MG-H3 | 2-amino-5-(2-amino-4-hydro-4-methyl-5-imidazolon-1-yl)-pentanoic acid |

| MGO | methylglyoxal |

| MKK7 | mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 7 |

| NEFA | non-esterified fatty acids |

| NF-κB | nuclear factor-kB |

| NOX | NADPH oxidase |

| Nrf2 | nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 |

| PARP | poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase |

| PRR | pattern recognition receptors |

| PUFAs | polyunsaturated fatty acids |

| p38 MAPK | p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| RAGE | advanced glycation end products receptor |

| RCS | reactive carbonyl species |

| RCT | randomized controlled trial |

| RNS | reactive nitrogen species |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| SCFAs | short chain fatty acids |

| SMAD3 | a protein involved in TGFβ signal transduction |

| SOD | superoxide dismutase |

| SREBP | sterol regulatory element-binding protein |

| TAGs | triacylglycerols |

| TAK1 | TGFβ-activated kinase 1 |

| TBARS | thiobarbituric acid reactive substances |

| TC | total cholesterol |

| TCA | tricarboxylic acid cycle (Krebs cycle) |

| T2DM | type 2 diabetes mellitus |

| TfR1 | transferrin receptor 1 |

| TGFβ | transforming growth factor β |

| THP | tetrahydropyrimidine |

| TNFα | tumor necrosis factor alfa |

| Trx | thioredoxin |

| WR | Wistar rats |

References

- Eslam, M.; Newsome, P.N.; Sarin, S.K.; Anstee, Q.M.; Targher, G.; Romero-Gomez, M.; Zelber-Sagi, S.; Wai-Sun Wong, V.; Dufour, J.F.; Schattenberg, J.M.; et al. A new definition for metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease: An international expert consensus statement. J. Hepatol. 2020, 73, 202–209. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL); European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD); European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO). European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL). EASL-EASD-EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). J. Hepatol. 2024, 81, 492–542. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buzzetti, E.; Pinzani, M.; Tsochatzis, E.A. The multiple-hit pathogenesis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Metabolism 2016, 65, 1038–1048. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loomba, R.; Friedman, S.L.; Shulman, G.I. Mechanisms and disease consequences of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Cell 2021, 184, 2537–2564. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gofton, C.; Upendran, Y.; Zheng, M.H.; George, J. MAFLD: How is it different from NAFLD? Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 2023, 29 (Suppl. S17–S31), 371. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Li, Y.; Yang, P.; Ye, J.; Xu, Q.; Wu, J.; Wang, Y. Updated mechanisms of MASLD pathogenesis. Lipids Health Dis. 2024, 23, 117. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yao, J.; Wu, D.; Qiu, Y. Adipose tissue macrophage in obesity-associated metabolic diseases. Front. Immunol. 2022, 2; 977485. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Xu, L.; Yan, X.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, B.; Yu, S.; Fu, J.; Liu, Y.; Su, J. Macrophage Polarization Mediated by Mitochondrial Dysfunction Induces Adipose Tissue Inflammation in Obesity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9252. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Huneault, H.E.; Ramirez Tovar, A.; Sanchez-Torres, C.; Welsh, J.A.; Vos, M.B. The Impact and Burden of Dietary Sugars on the Liver. Hepatol. Commun. 2023, 7, e0297. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Salavrakos, M.; de Timary, P.; Ruiz Moreno, A.; Thissen, J.P.; Lanthier, N. Fructoholism in adults: The importance of personalised care in metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease. JHEP Rep. 2021, 4, 100396. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ribeiro, A.; Igual-Perez, M.J.; Santos Silva, E.; Sokal, E.M. Childhood Fructoholism and Fructoholic Liver Disease. Hepatol. Commun. 2018, 3, 44-51. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lustig, R.H. Fructose: Metabolic, hedonic, and societal parallels with ethanol. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2010, 110, 1307–1321. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, J.; Wu, L.; Wei, J.; Wu, J.; Guo, C. The Gut Microbiome and Ferroptosis in MAFLD. J. Clin. Transl. Hepatol. 2023, 11, 174-187. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jayachandran, M.; Qu, S. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and gut microbial dysbiosis- underlying mechanisms and gut microbiota mediated treatment strategies. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2023, 24, 1189-1204. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benedé-Ubieto, R.; Cubero, F.J.; Nevzorova, Y.A. Breaking the barriers: The role of gut homeostasis in Metabolic-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD). Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2331460. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Canfora, E.E.; Meex, R.C.R.; Venema, K.; Blaak, E.E. Gut microbial metabolites in obesity, NAFLD and T2DM. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2019, 15, 261-273. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindén, D.; Romeo, S. Therapeutic opportunities for the treatment of NASH with genetically validated targets. J. Hepatol. 2023, 79, 1056-1064. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozlitina, J.; Smagris, E.; Stender, S.; Nordestgaard, B.G.; Zhou, H.H.; Tybjærg-Hansen, A.; Vogt, T.F.; Hobbs, H.H.; Cohen, J.C. Exome-wide association study identifies a TM6SF2 variant that confers susceptibility to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat. Genet. 2014, 46, 352–356. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Liu, Y.L.; Reeves, H.L.; Burt, A.D.; Tiniakos, D.; McPherson, S.; Leathart, J.B.; Allison, M.E.; Alexander, G.J.; Piguet, A.C.; Anty, R.; et al. TM6SF2 rs58542926 influences hepatic fibrosis progression in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 4309. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chen, X.; Li, J.; Kang, R.; Klionsky, D.J.; Tang, D. Ferroptosis: Machinery and regulation. Autophagy 2021, 17, 2054-2081. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shen, X.; Yu, Z.; Wei, C.; Hu, C.; Chen, J. Iron metabolism and ferroptosis in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: What is our next step? Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2024, 326, E767–E775. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, B.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, M.; Yang, S.; Tong, R.; Li, W.; Long, E. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: Ferroptosis related mechanisms and potential drugs. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1286449. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Peleman, C.; Francque, S.; Berghe, T.V. Emerging role of ferroptosis in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: Revisiting hepatic lipid peroxidation. EBioMedicine 2024, 102, 105088. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yao, C.; Lan, D.; Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Qi, S.; Liu, Y. Porphyromonas gingivalis is a risk factor for the development of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease via ferroptosis. Microbes Infect. 2023, 25, 105040. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, P.; Saltiel, A.R. From overnutrition to liver injury: AMP-activated protein kinase in nonalcoholic fatty liver diseases. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 12279-12289. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- von Loeffelholz, C.; Coldewey, S.M.; Birkenfeld, A.L. A Narrative Review on the Role of AMPK on De Novo Lipogenesis in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Evidence from Human Studies. Cells 2021, 10, 1822. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhao, P.; Sun, X.; Chaggan, C.; Liao, Z.; In Wong, K.; He, F.; Singh, S.; Loomba, R.; Karin, M.; Witztum, J.L.; et al. An AMPK-caspase-6 axis controls liver damage in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Science 2020, 367, 652-660. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wu, P.; Zhao, J.; Guo, Y.; Yu, Y.; Wu, X.; Xiao, H. Ursodeoxycholic acid alleviates nonalcoholic fatty liver disease by inhibiting apoptosis and improving autophagy via activating AMPK. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020, 529, 834-838. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.H.; Park, J.S.; Lee, Y.S.; Han, J.; Lee, D.K.; Kwon, S.W.; Han, D.H.; Lee, Y.H.; Bae, S.H. SQSTM1/p62 activates NFE2L2/NRF2 via ULK1-mediated autophagic KEAP1 degradation and protects mouse liver from lipotoxicity. Autophagy 2020, 16, 1949-1973. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fang, C.; Pan, J.; Qu, N.; Lei, Y.; Han, J.; Zhang, J.; Han, D. The AMPK pathway in fatty liver disease. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 970292. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhu, S.; Wu, Z.; Wang, W.; Wei, L.; Zhou, H. A revisit of drugs and potential therapeutic targets against non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Learning from clinical trials. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2024, 47, 761-776. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallianou, N.G.; Kounatidis, D.; Psallida, S.; Vythoulkas-Biotis, N.; Adamou, A.; Zachariadou, T.; Kargioti, S.; Karampela, I.; Dalamaga, M. NAFLD/MASLD and the Gut-Liver Axis: From Pathogenesis to Treatment Options. Metabolites 2024, 14, 366. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Puetz, A.; Kappel, B.A. Gut Microbiome in Dyslipidemia and Atherosclerosis. In Gut Microbiome, Microbial Metabolites and Cardiometabolic Risk; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp.1–29. [CrossRef]

- Al Samarraie, A.; Pichette, M.; Rousseau, G. Role of the Gut Microbiome in the Development of Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5420. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bellucci, E.; Chiereghin, F.; Pacifici, F.; Donadel, G.; De Stefano, A.; Malatesta, G.; Valente, M.G.; Guadagni, F.; Infante, M.; Rovella, V.; et al. Novel therapeutic approaches based on the pathological role of gut dysbiosis on the link between nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and insulin resistance. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2023, 27, 1921-1944. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, S.P.; Karunakar, P.; Taraphder, S.; Yadav, H. Free Fatty Acid Receptors 2 and 3 as Microbial Metabolite Sensors to Shape Host Health: Pharmacophysiological View. Biomedicines 2020, 8, 154. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Farooqui, N.; Elhence, A.; Shalimar. A Current Understanding of Bile Acids in Chronic Liver Disease. J. Clin. Exp. Hepatol. 2022 12, 155-173. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Leung, C.; Herath, C.B.; Jia, Z.; Andrikopoulos, S.; Brown, B.E.; Davies, M.J.; Rivera, L.R.; Furness, J.B.; Forbes, J.M.; Angus, P.W. Dietary advanced glycation end-products aggravate non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 22, 8026–8040. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sakasai-Sakai, A.; Takeda, K.; Takeuchi, M. Involvement of Intracellular TAGE and the TAGE-RAGE-ROS Axis in the Onset and Progression of NAFLD/NASH. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 748. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Liu, J.; Jin, Z.; Wang, X.; Jakoš, T.; Zhu, J.; Yuan, Y. RAGE pathways play an important role in regulation of organ fibrosis. Life Sci. 2023, 323, 121713. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, C.; Herath, C.B.; Jia, Z.; Goodwin, M.; Mak, K.Y.; Watt, M.J.; Forbes, J.M.; Angus, P.W. Dietary glycotoxins exacerbate progression of experimental fatty liver disease. J. Hepatol. 2014, 60, 832–838. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ott, C.; Jacobs, K.; Haucke, E.; Navarrete Santos, A.; Grune, T.; Simm, A. Role of advanced glycation end products in cellular signaling. Redox Biol. 2014, 2, 411–429. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Iwamoto, K.; Kanno, K.; Hyogo, H.; Yamagishi, S.; Takeuchi, M.; Tazuma, S.; Chayama, K. Advanced glycation end products enhance the proliferation and activation of hepatic stellate cells. J. Gastroenterol. 2008, 43, 298-304. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, X.G.; Xia, J.R.; Li, W.D.; Lu, F.L.; Liu, J.; Lu, Q.; Zhi, H. Anti-fibrotic effects of specific-siRNA targeting of the receptor for advanced glycation end products in a rat model of experimental hepatic fibrosis. Mol. Med. Rep. 2014, 10, 306–314. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, P.; Deng, Q.; Gao, J.; Yu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Guan, W.; Hu, J.; Tan, Q.; Zhou, L.; et al. Therapeutic effects of antigen affinity-purified polyclonal anti-receptor of advanced glycation end-product (RAGE) antibodies on cholestasis-induced liver injury in rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2016, 779, 102–110. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dehnad, A.; Fan, W.; Jiang, J.X.; Fish, S.R.; Li, Y.; Das, S.; Mozes, G.; Wong, K.A.; Olson, K.A.; Charville, G.W.; et al. AGER1 downregulation associates with fibrosis in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and type 2 diabetes. J. Clin. Investig. 2020, 130, 4320-4330. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Asadipooya, K.; Lankarani, K.B.; Raj, R.; Kalantarhormozi, M. RAGE is a Potential Cause of Onset and Progression of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2019, 2019, 2151302. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Schalkwijk, C.G.; Stehouwer, C.D.A. Methylglyoxal, a Highly Reactive Dicarbonyl Compound, in Diabetes, Its Vascular Complications, and Other Age-Related Diseases. Physiol. Rev. 2020, 100, 407–461. [CrossRef]

- Phillips, S.A.; Thornalley, P.J. The formation of methylglyoxal from triose phosphates. Investigation using a specific assay for methylglyoxal. Eur. J. Biochem. 1993, 212, 101–105. [CrossRef]

- Sousa Silva, M.; Gomes, R.A.; Ferreira, A.E.; Ponces Freire, A.; Cordeiro, C. The glyoxalase pathway: The first hundred years and beyond. Biochem. J. 2013, 453, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Morgenstern, J.; Campos Campos, M.; Nawroth, P.; Fleming, T. The Glyoxalase System-New Insights into an Ancient Metabolism. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 939. [CrossRef]

- Phillips, S.A.; Mirrlees, D.; Thornalley, P.J. Modification of the glyoxalase system in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Effect of the aldose reductase inhibitor Statil. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1993, 46, 805–811. [CrossRef]

- Berdowska, I.; Matusiewicz, M.; Fecka, I. Methylglyoxal in Cardiometabolic Disorders: Routes Leading to Pathology Counterbalanced by Treatment Strategies. Molecules 2023, 28, 7742. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Galligan, J.J.; Wepy, J.A.; Streeter, M.D.; Kingsley, P.J.; Mitchener, M.M.; Wauchope, O.R.; Beavers, W.N.; Rose, K.L.; Wang, T.; Spiegel, D.A.; et al. Methylglyoxal-derived posttranslational arginine modifications are abundant histone marks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2018, 115, 9228–9233. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Richarme, G.; Mihoub, M.; Dairou, J.; Bui, L.C.; Leger, T.; Lamouri, A. Parkinsonism-associated protein DJ-1/Park7 is a major protein deglycase that repairs methylglyoxal- and glyoxal-glycated cysteine, arginine, and lysine residues. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 1885–1897. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Richarme, G.; Liu, C.; Mihoub, M.; Abdallah, J.; Leger, T.; Joly, N.; Liebart, J.C.; Jurkunas, U.V.; Nadal, M.; Bouloc, P. et al. Guanine glycation repair by DJ-1/Park7 and its bacterial homologs. Science 2017, 357, 208–211. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolgacheva, L.P.; Berezhnov, A.V.; Fedotova, E.I.; Zinchenko, V.P.; Abramov, A.Y. Role of DJ-1 in the mechanism of pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 2019, 51, 175–188. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Smolders, S.; Van Broeckhoven, C. Genetic perspective on the synergistic connection between vesicular transport, lysosomal and mitochondrial pathways associated with Parkinson’s disease pathogenesis. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2020, 8, 63. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pfaff, D.H.; Fleming, T.; Nawroth, P.; Teleman, A.A. Evidence Against a Role for the Parkinsonism-associated Protein DJ-1 in Methylglyoxal Detoxification. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 685–690. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mazza, M.C.; Shuck, S.C.; Lin, J.; Moxley, M.A.; Termini, J.; Cookson, M.R.; Wilson, M.A. DJ-1 is not a deglycase and makes a modest contribution to cellular defense against methylglyoxal damage in neurons. J. Neurochem. 2022, 162, 245-261. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Richarme, G.; Abdallah, J.; Mathas, N.; Gautier, V.; Dairou, J. Further characterization of the Maillard deglycase DJ-1 and its prokaryotic homologs, deglycase 1/Hsp31, deglycase 2/YhbO, and deglycase 3/YajL. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 503, 703-709. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richarme, G.; Dairou, J. Parkinsonism-associated protein DJ-1 is a bona fide deglycase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017, 483, 387-391. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreeva, A.; Bekkhozhin, Z.; Omertassova, N.; Baizhumanov, T.; Yeltay, G.; Akhmetali, M.; Toibazar, D.; Utepbergenov, D. The apparent deglycase activity of DJ-1 results from the conversion of free methylglyoxal present in fast equilibrium with hemithioacetals and hemiaminals. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 18863-18872. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rabbani, N.; Thornalley, P.J. Methylglyoxal, glyoxalase 1 and the dicarbonyl proteome. Amino Acids. 2012, 42, 1133–1142. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez-Castillo, C.; Shuck, S.C. Diet and Obesity-Induced Methylglyoxal Production and Links to Metabolic Disease. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2021, 34, 2424–2440. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalapos, M.P. Where does plasma methylglyoxal originate from? Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2013, 99, 260–271. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schumacher, D.; Morgenstern, J.; Oguchi, Y.; Volk, N.; Kopf, S.; Groener, J.B.; Nawroth, P.P.; Fleming, T.; Freichel, M. Com-pensatory mechanisms for methylglyoxal detoxification in experimental & clinical diabetes. Mol. Metab. 2018, 18, 143–152. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Morgenstern, J.; Fleming, T.; Schumacher, D.; Eckstein, V.; Freichel, M.; Herzig, S.; Nawroth, P. Loss of Glyoxalase 1 Induces Compensatory Mechanism to Achieve Dicarbonyl Detoxification in Mammalian Schwann Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 3224–3238. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ahmed, N.; Argirov, O.K.; Minhas, H.S.; Cordeiro, C.A.; Thornalley, P.J. Assay of advanced glycation endproducts (AGEs): Surveying AGEs by chromatographic assay with derivatization by 6-aminoquinolyl-N-hydroxysuccinimidyl-carbamate and application to Nepsilon-carboxymethyl-lysine- and Nepsilon-(1-carboxyethyl)lysine-modified albumin. Biochem. J. 2002, 364, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Klöpfer, A.; Spanneberg, R.; Glomb, M.A. Formation of arginine modifications in a model system of Nα-tert-butoxycarbonyl (Boc)-arginine with methylglyoxal. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 394–401. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N.; Dobler, D.; Dean, M.; Thornalley, P.J. Peptide mapping identifies hotspot site of modification in human serum albumin by methylglyoxal involved in ligand binding and esterase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 5724–5732. [CrossRef]

- Oya, T.; Hattori, N.; Mizuno, Y.; Miyata, S.; Maeda, S.; Osawa, T.; Uchida, K. Methylglyoxal modification of protein. Chemical and immunochemical characterization of methylglyoxal-arginine adducts. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 18492–18502. [CrossRef]

- Lieuw-a-Fa, M.L.; Schalkwijk, C.G.; Engelse, M.; van Hinsbergh, V.W. Interaction of Nepsilon(carboxymethyl)lysine- and methylglyoxal-modified albumin with endothelial cells and macrophages. Splice variants of RAGE may limit the responsiveness of human endothelial cells to AGEs. Thromb. Haemost. 2006, 95, 320–328. [CrossRef]

- Lo, T.W.; Westwood, M.E.; McLellan, A.C.; Selwood, T.; Thornalley, P.J. Binding and modification of proteins by methylglyoxal under physiological conditions. A kinetic and mechanistic study with N alpha-acetylarginine, N alpha-acetylcysteine, and N alpha-acetyllysine, and bovine serum albumin. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 32299–32305.

- Zhang, J.; Guo, J.; Yang, N.; Huang, Y.; Hu, T.; Rao, C. Endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated cell death in liver injury. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 1051. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ajoolabady, A.; Kaplowitz, N.; Lebeaupin, C.; Kroemer, G.; Kaufman, R.J.; Malhi, H.; Ren, J. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in liver diseases. Hepatology 2023, 77, 619-639. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gugliucci, A. Fructose surges damage hepatic adenosyl-monophosphate-dependent kinase and lead to increased lipogenesis and] hepatic insulin resistance. Med. Hypotheses 2016, 93, 87–92. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.C.; Chou, C.K.; Chuang, M.C.; Li, Y.C.; Lee, J.A. Elevated levels of liver methylglyoxal and d-lactate in early-stage hepatitis in rats. Biomed. Chromatogr. 2018, 32, e4039. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Y.; Wang, D.; Moran, G.; Estrada, A.; Pagliassotti, M.J. Fructose-induced stress signaling in the liver involves methylglyoxal. Nutr. Metab. 2013, 10, 32. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wei, Y.; Pagliassotti, M.J. Hepatospecific effects of fructose on c-jun NH2-terminal kinase: Implications for hepatic insulin resistance. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2004, 287, E926–E933. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tournier, C.; Whitmarsh, A.J.; Cavanagh, J.; Barrett, T.; Davis, R.J. Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 7 is an activator of the c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997, 94, 7337–7342. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Neves, C.; Rodrigues, T.; Sereno, J.; Simões, C.; Castelhano, J.; Gonçalves, J.; Bento, G.; Gonçalves, S.; Seiça, R.; Domingues, M.R.; et al. Dietary Glycotoxins Impair Hepatic Lipidemic Profile in Diet-Induced Obese Rats Causing Hepatic Oxidative Stress and Insulin Resistance. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2019, 2019, 6362910. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Peter, A.; Schleicher, E.; Kliemank, E.; Szendroedi, J.; Königsrainer, A.; Häring, H.U.; Nawroth, P.P.; Fleming, T. Accumulation of Non-Pathological Liver Fat Is Associated with the Loss of Glyoxalase I Activity in Humans. Metabolites 2024, 14, 209. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hüttl, M.; Markova, I.; Miklánková, D.; Zapletalova, I.; Kujal, P.; Šilhavý, J.; Pravenec, M.; Malinska, H. Hypolipidemic and insulin sensitizing effects of salsalate beyond suppressing inflammation in a prediabetic rat model. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1117683. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Malinská, H.; Hüttl, M.; Miklánková, D.; Trnovská, J.; Zapletalová, I.; Poruba, M.; Marková; I. Ovariectomy-Induced Hepatic Lipid and Cytochrome P450 Dysmetabolism Precedes Serum Dyslipidemia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4527. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, P.; Sang, S. Dietary Genistein Inhibits Methylglyoxal-Induced Advanced Glycation End Product Formation in Mice Fed a High-Fat Diet. J. Nutr. 2019, 149, 776-787. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spanos, C.; Maldonado, E.M.; Fisher, C.P.; Leenutaphong, P.; Oviedo-Orta, E.; Windridge, D.; Salguero, F.J.; Bermúdez-Fajardo, A.; Weeks, M.E.; Evans, C.; et al. Proteomic identification and characterization of hepatic glyoxalase 1 dysregulation in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Proteome Sci. 2018, 16, 4; Erratum in Proteome Sci. 2018, 16, 13. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Depner, C.M.; Traber, M.G.; Bobe, G.; Kensicki, E.; Bohren, K.M.; Milne, G.; Jump, D.B. A metabolomic analysis of omega-3 fatty acid-mediated attenuation of western diet-induced nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in LDLR-/-mice. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e83756. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hollenbach, M.; Thonig, A.; Pohl, S.; Ripoll, C.; Michel, M.; Zipprich, A. Expression of glyoxalase-I is reduced in cirrhotic livers: A possible mechanism in the development of cirrhosis. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0171260. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Loarca, L.; Sassi-Gaha, S.; Artlett, C.M. Two α-dicarbonyls downregulate migration, invasion, and adhesion of liver cancer cells in a p53-dependent manner. Dig. Liver Dis. 2013, 45, 938–946. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.; Yang, X.; He, Q.; Chen, Q.; Yu, L. Glyoxalase 1 is up-regulated in hepatocellular carcinoma and is essential for HCC cell proliferation. Biotechnol. Lett. 2014, 36, 257–263. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michel, M.; Hollenbach, M.; Pohl, S.; Ripoll, C.; Zipprich, A. Inhibition of Glyoxalase-I Leads to Reduced Proliferation, Migration and Colony Formation, and Enhanced Susceptibility to Sorafenib in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 785. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Michel, M.; Hess, C.; Kaps, L.; Kremer, W.M.; Hilscher, M.; Galle, P.R.; Moehler, M.; Schattenberg, J.M.; Wörns, M.A.; Labenz, C.; et al. Elevated serum levels of methylglyoxal are associated with impaired liver function in patients with liver cirrhosis. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 20506. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hollenbach, M. The Role of Glyoxalase-I (Glo-I), Advanced Glycation Endproducts (AGEs), and Their Receptor (RAGE) in Chronic Liver Disease and Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2466. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fernando, D.H.; Forbes, J.M.; Angus, P.W.; Herath, C.B. Development and Progression of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: The Role of Advanced Glycation End Products. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5037. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nigro, C.; Leone, A.; Fiory, F.; Prevenzano, I.; Nicolò, A.; Mirra, P.; Beguinot, F.; Miele, C. Dicarbonyl Stress at the Crossroads of Healthy and Unhealthy Aging. Cells 2019, 8, 749. [CrossRef]

- Zemva, J.; Fink, C.A.; Fleming, T.H.; Schmidt, L.; Loft, A.; Herzig, S.; Knieß, R.A.; Mayer, M.; Bukau, B.; Nawroth, P.P. et al. Hormesis enables cells to handle accumulating toxic metabolites during increased energy flux. Redox Biol. 2017, 13, 674–686. [CrossRef]

- Ravichandran, M.; Priebe, S.; Grigolon, G.; Rozanov, L.; Groth, M.; Laube, B.; Guthke, R.; Platzer, M.; Zarse, K.; Ristow, M. Impairing L-Threonine Catabolism Promotes Healthspan through Methylglyoxal-Mediated Proteohormesis. Cell Metab. 2018, 27, 914–925.e5. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Liang, X.; Zheng, X.; Huang, H.; Chen, X.; Wu, K.; Wang, B.; Ma, S. Glo1 genetic amplification as a potential therapeutic target in hepatocellular carcinoma. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2014, 7, 2079–2090. [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Liu, Y.; Zhu, X.; Zhu, J.; Liao, S.; Tang, Q.; Liu, K.; Guan, X.; Zhang, J.; Feng, Z. Identification of differential expression of genes in hepatocellular carcinoma by suppression subtractive hybridization combined cDNA microarray. Oncol. Rep. 2007, 18, 943–951. [PubMed]

- Taïbi, N.; Al-Balas, Q.A.; Bekari, N.; Talhi, O.; Al Jabal, G.A.; Benali, Y.; Ameraoui, R.; Hadjadj, M.; Taïbi, A.; Boutaiba, Z.M.; et al. Molecular docking and dynamic studies of a potential therapeutic target inhibiting glyoxalase system: Metabolic action of the 3, 3 ‘-[3-(5-chloro-2-hydroxyphenyl)-3-oxopropane-1, 1-diyl]-Bis-4-hydroxycoumarin leads overexpression of the intracellular level of methylglyoxal and induction of a pro-apoptotic phenomenon in a hepatocellular carcinoma model. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2021, 345, 109511. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thornalley, P.J.; Rabbani, N. Glyoxalase in tumourigenesis and multidrug resistance. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2011, 22, 318–325. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nokin, M.J.; Durieux, F.; Bellier, J.; Peulen, O.; Uchida, K.; Spiegel, D.A.; Cochrane, J.R.; Hutton, C.A.; Castronovo, V.; Bellahcène, A. Hormetic potential of methylglyoxal, a side-product of glycolysis, in switching tumours from growth to death. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 11722. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bellier, J.; Nokin, M.J.; Lardé, E.; Karoyan, P.; Peulen, O.; Castronovo, V.; Bellahcène, A. Methylglyoxal, a potent inducer of AGEs, connects between diabetes and cancer. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2019, 148, 200–211. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, T.; Abdelmalek, M.F.; Sullivan, S.; Nadeau, K.J.; Green, M.; Roncal, C.; Nakagawa, T.; Kuwabara, M.; Sato, Y.; Kang, D.H.; et al. Fructose and sugar: A major mediator of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Hepatol. 2018, 68, 1063–1075. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mortera, R.R.; Bains, Y.; Gugliucci, A. Fructose at the crossroads of the metabolic syndrome and obesity epidemics. Front. Biosci.-Landmark 2019, 24, 186–211. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, R.J.; Lanaspa, M.A.; Sanchez-Lozada, L.G.; Tolan, D.; Nakagawa, T.; Ishimoto, T.; Andres-Hernando, A.; Rodriguez-Iturbe, B.; Stenvinkel, P. The fructose survival hypothesis for obesity. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2023, 378, 20220230. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Brownlee, M. Biochemistry and molecular cell biology of diabetic complications. Nature 2001, 414, 813–820. [CrossRef]

- Brownlee, M. The pathobiology of diabetic complications: A unifying mechanism. Diabetes 2005, 54, 1615–1625. [CrossRef]

- Giacco, F.; Brownlee, M. Oxidative stress and diabetic complications. Circ. Res. 2010, 107, 1058–1070. [CrossRef]

- Barinova, K.V.; Serebryakova, M.V.; Melnikova, A.K.; Medvedeva, M.V.; Muronetz, V.I.; Schmalhausen, E.V. Mechanism of inactivation of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase in the presence of methylglyoxal. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2023, 733, 109485. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeuchi, M.; Takino, J.I.; Sakasai-Sakai, A.; Takata, T.; Tsutsumi, M. Toxic AGE (TAGE) Theory for the Pathophysiology of the Onset/Progression of NAFLD and ALD. Nutrients 2017, 9, 634. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Takeuchi, M.; Suzuki, H.; Takeda, K.; Sakai-Sakasai, A. (2024). Toxic advanced glycation end-products (TAGE) are major structures of cytotoxic AGEs derived from glyceraldehyde. Med. Hypotheses 2024, 183, 111248. [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, M.; Sakasai-Sakai, A.; Takata, T.; Takino, J.I.; Koriyama, Y.; Kikuchi, C.; Furukawa, A.; Nagamine, K.; Hori, T.; Matsunaga, T. Intracellular Toxic AGEs (TAGE) Triggers Numerous Types of Cell Damage. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 387. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Takeuchi, M. Toxic AGEs (TAGE) theory: A new concept for preventing the development of diseases related to lifestyle. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2020, 12, 105. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sakasai-Sakai, A.; Takata, T.; Takino, J.I.; Takeuchi, M. Impact of intracellular glyceraldehyde-derived advanced glycation end-products on human hepatocyte cell death. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 14282. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sakai-Sakasai, A.; Takeda, K.; Suzuki, H.; Takeuchi, M. Structures of Toxic Advanced Glycation End-Products Derived from Glyceraldehyde, A Sugar Metabolite. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 202. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gugliucci, A. Formation of Fructose-Mediated Advanced Glycation End Products and Their Roles in Metabolic and Inflammatory Diseases. Adv. Nutr. 2017, 8, 54–62. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Petagine, L.; Zariwala, M.G.; Patel, V.B. Alcoholic liver disease: Current insights into cellular mechanisms. World J. Biol. Chem. 2021, 12, 87–103. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wilson, D.F.; Matschinsky, F.M. Ethanol metabolism: The good, the bad, and the ugly. Med. Hypotheses. 2020, 140, 109638. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalavalapalli, S.; Leiva, E.G.; Lomonaco, R.; Chi, X.; Shrestha, S.; Dillard, R.; Budd, J.; Romero, J.P.; Li, C.; Bril, F.; et al. Adipose Tissue Insulin Resistance Predicts the Severity of Liver Fibrosis in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes and NAFLD. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2023, 108, 1192–1201. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, L.; Qiu, K.; Zheng, W.; Kong, W.; Zeng, T. Uric acid may serve as the sixth cardiometabolic criterion for defining MASLD. J. Hepatol. 2024, 80, e152–e153. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Y.; Yang, H.; Jeon, S.; Cho, K.W.; Kim, S.J.; Kim, S.; Lee, M.; Suh, J.; Chae, H.W.; Kim, H.S.; et al. Prediction of insulin resistance and elevated liver transaminases using serum uric acid and derived markers in children and adolescents. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2024, 78, 864–871. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosmas, C.E.; Bousvarou, M.D.; Kostara, C.E.; Papakonstantinou, E.J.; Salamou, E.; Guzman, E. Insulin resistance and cardiovascular disease. J. Int. Med. Res. 2023, 51, 3000605231164548. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, Q.; Qin, B. Association between remnant cholesterol and insulin resistance levels in patients with metabolic-associated fatty liver disease. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 4596. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Genua, I.; Cusi, K. Pharmacological Approaches to Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Current and Future Therapies. Diabetes Spectr. 2024, 37, 48–58. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Paulino, P.J.I.V.; Cuthrell, K.M.; Tzenios, N. Non Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease; Disease Burden, Management, and Future Perspectives. Int. Res. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 7, 1–13. http://archive.pcbmb.org/id/eprint/1800.

- Shinozaki, S.; Tahara, T.; Miura, K.; Lefor, A.K.; Yamamoto, H. Pemafibrate therapy for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is more effective in lean patients than obese patients. Clin. Exp. Hepatol. 2022, 8, 278–283. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang, S.; Zhao, J.; Xie, F.; He, H.; Johnston, L.J.; Dai, X.; Wu, C.; Ma, X. Dietary fiber-derived short-chain fatty acids: A potential therapeutic target to alleviate obesity-related nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Obes. Rev. 2021, 22, e13316. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkhouri, N.; Scott, A. An Update on the Pharmacological Treatment of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Beyond Lifestyle Modifications. Clin. Liver Dis. 2018, 11, 82–86. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhao, J.; Li, B.; Zhang, K.; Zhu, Z. The effect and safety of obeticholic acid for patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Medicine 2024, 103, e37271.

- Harrison, S.A.; Bedossa, P.; Guy, C.D.; Schattenberg, J.M.; Loomba, R.; Taub, R.; Labriola, D.; Moussa, S.E.; Neff, G.W.; Rinella, M.E.; et al. MAESTRO-NASH Investigators. A Phase 3, Randomized, Controlled Trial of Resmetirom in NASH with Liver Fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 390, 497–509. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, S.A.; Taub, R.; Neff, G.W.; Lucas, K.J.; Labriola, D.; Moussa, S.E.; Alkhouri, N.; Bashir, M.R. Resmetirom for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 2919–2928. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Harrison, S.A.; Wong, V.W.; Okanoue, T.; Bzowej, N.; Vuppalanchi, R.; Younes, Z.; Kohli, A.; Sarin, S.; Caldwell, S.H.; Alkhouri, N.; et al. Selonsertib for patients with bridging fibrosis or compensated cirrhosis due to NASH: Results from randomized phase III STELLAR trials. J. Hepatol. 2020, 73, 26–39. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anstee, Q.M.; Neuschwander-Tetri, B.A.; Wai-Sun Wong, V.; Abdelmalek, M.F.; Rodriguez-Araujo, G.; Landgren, H.; Park, G.S.; Bedossa, P.; Alkhouri, N.; Tacke, F.; et al. Cenicriviroc Lacked Efficacy to Treat Liver Fibrosis in Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis: AURORA Phase III Randomized Study. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 22, 124–134.e1. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blair, H.A. Elafibranor: First Approval. Drugs 2024, 84, 1143–1148; Erratum in Drugs 2024, 84, 1165. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keam, S.J. Resmetirom: First Approval. Drugs 2024, 84, 729–735. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petta, S.; Targher, G.; Romeo, S.; Pajvani, U.B.; Zheng, M.H.; Aghemo, A.; Valenti, L.V.C. The first MASH drug therapy on the horizon: Current perspectives of resmetirom. Liver Int. 2024, 44, 1526–1536. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jophlin, L.L.; Singal, A.K.; Bataller, R.; Wong, R.J.; Sauer, B.G.; Terrault, N.A.; Shah, V.H. ACG Clinical Guideline: Alcohol-Associated Liver Disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2024, 119, 30–54. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yki-Järvinen, H.; Luukkonen, P.K.; Hodson, L.; Moore, J.B. Dietary carbohydrates and fats in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 18, 770–786. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, W.K.; Chuah, K.H.; Rajaram, R.B.; Lim, L.L.; Ratnasingam, J.; Vethakkan, S.R. Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD): A State-of-the-Art Review. J. Obes. Metab. Syndr. 2023, 32, 197–213. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hansen, C.D.; Gram-Kampmann, E.M.; Hansen, J.K.; Hugger, M.B.; Madsen, B.S.; Jensen, J.M.; Olesen, S.; Torp, N.; Rasmussen, D.N.; Kjærgaard, M.; et al. Effect of Calorie-Unrestricted Low-Carbohydrate, High-Fat Diet Versus High-Carbohydrate, Low-Fat Diet on Type 2 Diabetes and Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 2023, 176, 10–21. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cha, J.Y.; Kim, S.Y.; Lim, Y.W.; Choi, K.H.; Shin, I.S. Comparative Effectiveness of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and Behavioral Therapy in Obesity: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Settings. 2024. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hegazi, O.E.; Alalalmeh, S.O.; Shahwan, M.; Jairoun, A.A.; Alourfi, M.M.; Bokhari, G.A.; Alkhattabi, A.; Alsharif, S.; Aljehani, M.A.; Alsabban, A.M.; et al. Exploring Promising Therapies for Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A ClinicalTrials.gov Analysis. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2024, 17, 545–561. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gastaldelli A, Cusi K, Fernández Landó L, Bray R, Brouwers B, Rodríguez, Á. Effect of tirzepatide versus insulin degludec on liver fat content and abdominal adipose tissue in people with type 2 diabetes (SURPASS-3 MRI): A substudy of the randomised, open-label, parallel-group, phase 3 SURPASS-3 trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2022, 10, 393–406. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gastaldelli, A.; Cusi, K.; Landó, L.F.; Bray, R.; Brouwers, B.; Rodríguez, Á.; Menzen, M. Effect of Tirzepatide Versus Insulin Degludec on Liver Fat Content and Abdominal Adipose Tissue in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes (SURPASS-3 MRI). Diabetol. Und Stoffwechs. 2023, 18 (Supp. S15–S16), P-004. [CrossRef]

- Koh, B.; Xiao, J.; Ng, C.H.; Law, M.; Gunalan, S.Z.; Danpanichkul, P.; Ramadoss, V.; Sim, B.K.L.; Tan, E.Y.; Teo, C.B.; et al. Comparative efficacy of pharmacologic therapies for MASH in reducing liver fat content: Systematic review and network meta-analysis. Hepatology 2024. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Wang, X.; Yan, C.; Li, C.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, L.; Liang, E.; Liu, T.; Mao, J. Effect of metformin on nonalcoholic fatty liver based on meta-analysis and network pharmacology. Medicine 2022, 101, e31437. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mansi, I.A.; Chansard, M.; Lingvay, I.; Zhang, S.; Halm, E.A.; Alvarez, C.A. Association of Statin Therapy Initiation with Diabetes Progression: A Retrospective Matched-Cohort Study. JAMA Intern. Med. 2021, 181, 1562–1574. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mansi, I.A.; Sumithran, P.; Kinaan, M. Risk of diabetes with statins. BMJ 2023, 381, e071727. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbasi, F.; Lamendola, C.; Harris, C.S.; Harris, V.; Tsai, M.S.; Tripathi, P.; Abbas, F.; Reaven, G.M.; Reaven, P.D.; Snyder, M.P.; et al. Statins Are Associated with Increased Insulin Resistance and Secretion. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2021, 41, 2786–2797. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Galicia-Garcia, U.; Jebari, S.; Larrea-Sebal, A.; Uribe, K.B.; Siddiqi, H.; Ostolaza, H.; Benito-Vicente, A.; Martín, C. Statin Treatment-Induced Development of Type 2 Diabetes: From Clinical Evidence to Mechanistic Insights. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4725. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ling, Z.; Shu, N.; Xu, P.; Wang, F.; Zhong, Z.; Sun, B.; Li, F.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, K.; Tang, X.; et al. Involvement of pregnane X receptor in the impaired glucose utilization induced by atorvastatin in hepatocytes. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2016, 100, 98–111. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wah Kheong, C.; Nik Mustapha, N.R.; Mahadeva, S. A Randomized Trial of Silymarin for the Treatment of Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 15, 1940–1949.e8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarro, V.J.; Belle, S.H.; D’Amato, M.; Adfhal, N.; Brunt, E.M.; Fried, M.W.; Reddy, K.R.; Wahed, A.S.; Harrison, S. Silymarin in NASH and C Hepatitis (SyNCH) Study Group. Silymarin in non-cirrhotics with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: A randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0221683; Erratum in PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0223915. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ceriello, A. Hypothesis: The “metabolic memory”, the new challenge of diabetes. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2009, 86 (Suppl. S1), S2–S6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobbie, L.J.; Burgess, J.; Hamid, A.; Nevitt, S.J.; Hydes, T.J.; Alam, U.; Cuthbertson, D.J. Effect of a Low-Calorie Dietary Intervention on Liver Health and Body Weight in Adults with Metabolic-Dysfunction Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD) and Overweight/Obesity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1030. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ma, Y.; Sun, Y.; Sun, L.; Liu, X.; Zeng, R.; Lin, X.; Li, Y. Effects of gut microbiota and fatty acid metabolism on dyslipidemia following weight-loss diets in women: Results from a randomized controlled trial. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 5511–5520. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seethaler, B.; Nguyen, N.K.; Basrai, M.; Kiechle, M.; Walter, J.; Delzenne, N.M.; Bischoff, S.C. Short-chain fatty acids are key mediators of the favorable effects of the Mediterranean diet on intestinal barrier integrity: Data from the randomized controlled LIBRE trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 116, 928–942. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Losasso, C.; Eckert, E.M.; Mastrorilli, E.; Villiger, J.; Mancin, M.; Patuzzi, I.; Di Cesare, A.; Cibin, V.; Barrucci, F.; Pernthaler, J.; et al. Assessing the Influence of Vegan, Vegetarian and Omnivore Oriented Westernized Dietary Styles on Human Gut Microbiota: A Cross Sectional Study. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 317. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- De Filippis, F.; Pellegrini, N.; Vannini, L.; Jeffery, I.B.; La Storia, A.; Laghi, L.; Serrazanetti, D.I.; Di Cagno, R.; Ferrocino, I.; Lazzi, C.; et al. High-level adherence to a Mediterranean diet beneficially impacts the gut microbiota and associated metabolome. Gut 2016, 65, 1812–1821. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landry, M.J.; Ward, C.P.; Cunanan, K.M.; Durand, L.R.; Perelman, D.; Robinson, J.L.; Hennings, T.; Koh, L.; Dant, C.; Zeitlin, A.; et al. Cardiometabolic Effects of Omnivorous vs. Vegan Diets in Identical Twins: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2344457; Erratum in JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2350422. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tanaka, M.; Nakayama, J. Development of the gut microbiota in infancy and its impact on health in later life. Allergol. Int. 2017, 66, 515–522. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monda, V.; Villano, I.; Messina, A.; Valenzano, A.; Esposito, T.; Moscatelli, F.; Viggiano, A.; Cibelli, G.; Chieffi, S.; Monda, M.; et al. Exercise Modifies the Gut Microbiota with Positive Health Effects. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2017, 2017, 3831972. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sun, C.; Li, A.; Xu, C.; Ma, J.; Wang, H.; Jiang, Z.; Hou, J. Comparative Analysis of Fecal Microbiota in Vegetarians and Omnivores. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2358. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Prochazkova, M.; Budinska, E.; Kuzma, M.; Pelantova, H.; Hradecky, J.; Heczkova, M.; Daskova, N.; Bratova, M.; Modos, I.; Videnska, P.; et al. Vegan Diet Is Associated with Favorable Effects on the Metabolic Performance of Intestinal Microbiota: A Cross-Sectional Multi-Omics Study. Front. Nutr. 2022, 8, 783302. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rinninella, E.; Raoul, P.; Cintoni, M.; Franceschi, F.; Miggiano, G.A.D.; Gasbarrini, A.; Mele, M.C. What is the Healthy Gut Microbiota Composition? A Changing Ecosystem across Age, Environment, Diet, and Diseases. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 14. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Takeuchi, M.; Suzuki, H.; Sakai-Sakasai, A. Major generation route of cytotoxic protein adducts derived from acetaldehyde, a metabolite of alcohol. Med. Hypotheses 2024, 189, 111385. [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, T.; Shibamoto, T. Analysis of methyl glyoxal in foods and beverages. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1985, 33, 1090–1093. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/pdf/10.1021/jf00066a018.

- Hopper, D.J.; Cooper, R.A. The regulation of Escherichia coli methylglyoxal synthase; a new control site in glycolysis? FEBS Lett. 1971, 13, 213–216. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Booth, I.R.; Ferguson, G.P.; Miller, S.; Li, C.; Gunasekera, B.; Kinghorn, S. Bacterial production of methylglyoxal: A survival strategy or death by misadventure? Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2003, 31 Pt 6,1406–1408. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baskaran, S.; Rajan, D.P.; Balasubramanian, K.A. Formation of methylglyoxal by bacteria isolated from human faeces. J. Med. Microbiol. 1989, 28, 211–215. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandrangsu, P.; Dusi, R.; Hamilton, C.J.; Helmann, J.D. Methylglyoxal resistance in Bacillus subtilis: Contributions of bacillithiol-dependent and independent pathways. Mol. Microbiol. 2014, 91, 706–715. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Srebreva, L.N.; Stoynev, G.A.; Ivanov, I.G. Evidence for excretion of glycation agents from E. coli cells during growth. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2009, 23, 1068–1071. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Guo, T.L. Dietary advanced glycation end-products elicit toxicological effects by disrupting gut microbiome and immune homeostasis. J. Immunotoxicol. 2021, 18, 93–104. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yuan, X.; Liu, J.; Nie, C.; Ma, Q.; Wang, C.; Liu, H.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, M.; Li, J. Comparative Study of the Effects of Dietary-Free and -Bound Nε-Carboxymethyllysine on Gut Microbiota and Intestinal Barrier. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 5014–5025. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aschner, M.; Skalny, A.V.; Gritsenko, V.A.; Kartashova, O.L.; Santamaria, A.; Rocha, J.B.T.; Spandidos, D.A.; Zaitseva, I.P.; Tsatsakis, A.; Tinkov, A.A. Role of gut microbiota in the modulation of the health effects of advanced glycation end-products (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 2023, 51, 44. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Xie, F.; Zhao, J.; Liu, D.; Wan, Z.; Sun, K.; Wang, Y. Associations of dietary advanced glycation end products with liver steatosis via vibration controlled transient elastography in the United States: A nationwide cross-sectional study. Eur. J. Nutr. 2024, 63, 173–183. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beisswenger, P.J.; Howell, S.K.; Touchette, A.D.; Lal, S.; Szwergold, B.S. (1999). Metformin reduces systemic methylglyoxal levels in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 1999, 48, 198–202. [CrossRef]

- Kinsky, O.R.; Hargraves, T.L.; Anumol, T.; Jacobsen, N.E.; Dai, J.; Snyder, S.A.; Monks, T.J.; Lau, S.S. Metformin Scavenges Methylglyoxal to form a Novel Imidazolinone Metabolite in Humans. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2016, 29, 227–234. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shao, X.; Chen, H.; Zhu, Y.; Sedighi, R.; Ho, C.T.; Sang, S. Essential Structural Requirements and Additive Effects for Flavonoids to Scavenge Methylglyoxal. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 3202–3210. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhan, L.; Wen, Q.; Feng, Y.; Luo, Y.; Tan, T. Trapping Methylglyoxal by Taxifolin and Its Metabolites in Mice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 5026–5038. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhuiyan, M. N. I., Mitsuhashi, S., Sigetomi, K., & Ubukata, M. (2017). Quercetin inhibits advanced glycation end product formation via chelating metal ions, trapping methylglyoxal, and trapping reactive oxygen species. Bioscience, biotechnology, and biochemistry, 81(5), 882-890. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Chen, C.; Zhang, B.; Huang, Q. The inhibitory effects of flavonoids on α-amylase and α-glucosidase. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 60, 695–708. [CrossRef]

- Proença, C.; Ribeiro, D.; Freitas, M.; Fernandes, E. Flavonoids as potential agents in the management of type 2 diabetes through the modulation of α-amylase and α-glucosidase activity: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 3137–3207. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, J.; Ferruzzi, M.G.; Hamaker, B.R. Structural requirements of flavonoids for the selective inhibition of α-amylase versus α-glucosidase. Food Chem. 2022, 370, 130981. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, J.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, C.; Yang, W.; Liu, H.; Lv, Z.; Liu, J.; Jiao, Z. Inhibition of Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 by Flavonoids: Structure-Activity Relationship, Kinetics and Interaction Mechanism. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 892426. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chen, S.; Wang, X.; Cheng, Y.; Gao, H.; Chen, X. A Review of Classification, Biosynthesis, Biological Activities and Potential Applications of Flavonoids. Molecules 2023, 28, 4982. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang, M.; Lu, Y.; Wu, Q.; Chen, G.; Zhao, H.; Ho, C.T.; Li, S. Biotransformation and Gut Microbiota-Mediated Bioactivity of Flavonols. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 8317–8331. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Kurita, A.; Nakashima, S.; Zhu, B.; Munemasa, S.; Nakamura, T.; Murata, Y.; Nakamura, Y. 3,4-Dihydroxyphenylacetic acid is a potential aldehyde dehydrogenase inducer in murine hepatoma Hepa1c1c7 cells. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2017, 81, 1978–1983. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fecka, I.; Bednarska, K.; Kowalczyk, A. In Vitro Antiglycation and Methylglyoxal Trapping Effect of Peppermint Leaf (Mentha × piperita L.) and Its Polyphenols. Molecules 2023, 28, 2865. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ramos, F.M.M.; Ribeiro, C.B.; Cesar, T.B.; Milenkovic, D.; Cabral, L.; Noronha, M.F.; Sivieri, K. Lemon flavonoids nutraceutical (Eriomin®) attenuates prediabetes intestinal dysbiosis: A double-blind randomized controlled trial. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 11, 7283–7295. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Malik, A.; Malik, M.; Qureshi, S. Effects of silymarin use on liver enzymes and metabolic factors in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Can. Liver J. 2024, 7, 40–53. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Li, S.; Duan, F.; Li, S.; Lu, B. Administration of silymarin in NAFLD/NASH: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Hepatol. 2024, 29, 101174. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, J.; Zhi, M.; Gao, X.; Hu, P.; Li, C.; Yang, X. Effect and the probable mechanisms of silibinin in regulating insulin resistance in the liver of rats with non-alcoholic fatty liver. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2013, 46, 270–277. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Velussi, M.; Cernigoi, A.M.; De Monte, A.; Dapas, F.; Caffau, C.; Zilli, M. Long-term (12 months) treatment with an anti-oxidant drug (silymarin) is effective on hyperinsulinemia, exogenous insulin need and malondialdehyde levels in cirrhotic diabetic patients. J. Hepatol. 1997, 26, 871–879. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, S.; Fan, Y.; Yan, Q.; Fan, X.; Wu, B.; Han, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, H.; Niu, J. The therapeutic effect of silymarin in the treatment of nonalcoholic fatty disease: A meta-analysis (PRISMA) of randomized control trials. Medicine 2017, 96, e9061. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jin, Y.; Wang, X.; Chen, K.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, L.; Zeng, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Pan, Z.; Wang, D.; Li, Z.; et al. Silymarin decreases liver stiffness associated with gut microbiota in patients with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lipids Health Dis. 2024, 23, 239. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yi, M.; Manzoor, M.; Yang, M.; Zhang, H.; Wang, L.; Zhao, L.; Xiang, L.; Qi, J. Silymarin targets the FXR protein through microbial metabolite 7-keto-deoxycholic acid to treat MASLD in obese mice. Phytomedicine 2024, 133, 155947. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Ji, K.; Du, F.; Jin, N.; Boesch, C.; Farag, M.A.; Li, H.; Liu, X.; Xiao, J. Does Flavonoid Supplementation Alleviate Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2023, 67, e2300480. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 89. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Mori, T.; Jiang, Y.; Hu, C.; Osaki, Y.; Yoneki, Y.; Sun, Y.; Hosoya, T.; Kawamata, A.; Ogawa, S.; et al. Methylglyoxal contributes to the development of insulin resistance and salt sensitivity in Sprague-Dawley rats. J. Hypertens. 2009, 27, 1664–1671. [CrossRef]

- Dhar, A.; Desai, K.M.; Wu, L. Alagebrium attenuates acute methylglyoxal-induced glucose intolerance in Sprague-Dawley rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2010, 159, 166–175. [CrossRef]

- Nigro, C.; Raciti, G.A.; Leone, A.; Fleming, T.H.; Longo, M.; Prevenzano, I.; Fiory, F.; Mirra, P.; D’Esposito, V.; Ulianich, L.; et al. Methylglyoxal impairs endothelial insulin sensitivity both in vitro and in vivo. Diabetologia 2014, 57, 1485–1494. [CrossRef]

- Nigro, C.; Leone, A.; Raciti, G.A.; Longo, M.; Mirra, P.; Formisano, P.; Beguinot, F.; Miele, C. Methylglyoxal-Glyoxalase 1 Balance: The Root of Vascular Damage. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 188. [CrossRef]

- Shamsaldeen, Y.A.; Mackenzie, L.S.; Lione, L.A.; Benham, C.D. Methylglyoxal, A Metabolite Increased in Diabetes is Associated with Insulin Resistance, Vascular Dysfunction and Neuropathies. Curr. Drug Metab. 2016, 17, 359–367. [CrossRef]

- Mey, J.T.; Haus, J.M. Dicarbonyl Stress and Glyoxalase-1 in Skeletal Muscle: Implications for Insulin Resistance and Type 2 Diabetes. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2018, 5, 117. [CrossRef]

- Riboulet-Chavey, A.; Pierron, A.; Durand, I.; Murdaca, J.; Giudicelli, J.; Van Obberghen, E. Methylglyoxal impairs the insulin signaling pathways independently of the formation of intracellular reactive oxygen species. Diabetes 2006, 55, 1289–1299. [CrossRef]

- Engelbrecht, B.; Mattern, Y.; Scheibler, S.; Tschoepe, D.; Gawlowski, T.; Stratmann, B. Methylglyoxal impairs GLUT4 trafficking and leads to increased glucose uptake in L6 myoblasts. Horm. Metab. Res. 2014, 46, 77–84. [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Wu, L. Accumulation of endogenous methylglyoxal impaired insulin signaling in adipose tissue of fructose-fed rats. Mol. Cell Biochem. 2007, 306, 133–139. [CrossRef]

- Dhar, A.; Dhar, I.; Jiang, B.; Desai, K.M.; Wu, L. Chronic methylglyoxal infusion by minipump causes pancreatic beta-cell dysfunction and induces type 2 diabetes in Sprague-Dawley rats. Diabetes 2011, 60, 899–908. [CrossRef]

- Matafome, P.; Santos-Silva, D.; Crisóstomo, J.; Rodrigues, T.; Rodrigues, L.; Sena, C.M.; Pereira, P.; Seiça, R. Methylglyoxal causes structural and functional alterations in adipose tissue independently of obesity. Arch. Physiol. Biochem. 2012, 118, 58–68. [CrossRef]

- Hüttl, M.; Markova, I.; Miklankova, D.; Makovicky, P.; Pelikanova, T.; Šeda, O.; Šedová, L.; Malinska, H. Adverse Effects of Methylglyoxal on Transcriptome and Metabolic Changes in Visceral Adipose Tissue in a Prediabetic Rat Model. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 803. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, T.; Matafome, P.; Sereno, J.; Almeida, J.; Castelhano, J.; Gamas, L.; Neves, C.; Gonçalves, S.; Carvalho, C.; Arslanagic, A.; et al. Methylglyoxal-induced glycation changes adipose tissue vascular architecture, flow and expansion, leading to insulin resistance. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1698. [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Olson, D.J.; Ross, A.R.; Wu, L. Structural and functional changes in human insulin induced by methylglyoxal. FASEB J. 2006, 20, 1555–1557. [CrossRef]

- Fiory, F.; Lombardi, A.; Miele, C.; Giudicelli, J.; Beguinot, F.; Van Obberghen, E. Methylglyoxal impairs insulin signalling and insulin action on glucose-induced insulin secretion in the pancreatic beta cell line INS-1E. Diabetologia 2011, 54, 2941–2952. Erratum in: Diabetologia 2012, 55, 272. [CrossRef]

- Bo, J.; Xie, S.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, C.; Guan, Y.; Li, C.; Lu, J.; Meng, Q.H. Methylglyoxal Impairs Insulin Secretion of Pancreatic β-Cells through Increased Production of ROS and Mitochondrial Dysfunction Mediated by Upregulation of UCP2 and MAPKs. J. Diabetes Res. 2016, 2016, 2029854. [CrossRef]

| Experimental Model | Detailed Observations | Major Findingsin the Liver Tissue/Cells | Ref./Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early MASLD | |||

| Seven-week-old male Wistar rats (WR) divided into 2 groups: (1) WR injected with (0.3 mL/kg/week of 40%) CCl4 (in soy bean oil) for 4 weeks. (2) WR injected with the same volume of soybean oil (control group) |

In the serum (as compared with control group): increase in D-lactate; no change in AST, ALT and MGO concentration. In the liver: increase in MGO level and D-lactate. In the urine: increase in D-lactate; no change in MGO concentration. |

In the model of early MASLD: MGO and D-lactate in the liver ↑ |

[78]/2018 |

| (1) 6-month-old male hereditary hypertriglyceridemic rats (HHTg) as the non-obese prediabetic model treated or not-treated with salsalate (2) WR as the control group |

In HHTg rats (in comparison with WR and attenuated by salsalate); In the liver: increase in MGO, TAGs, Chol; increase in oxidative stress (TBARS ↑, GSH/GSSG ↓, SOD ↓). Upon salsalate treatment in HHTg: increased expression of Glo1 gene associated with MGO decrease. |

In the model of hypertriglyceridemia/prediabetes: MGO, lipids and oxidative stress in the liver ↑ |

[84]/2023 |

| Female Wistar rats (WR) divided into 2 groups: (1) Ovariectomized WR used as a model of postmenopausal MetS (W-OVX); (2) Sham-operated WR as a control (W-sham) |

In W-OVX rats (in comparison with W-sham rats); In the serum: increase in leptin, FAs, HDL-Chol, MCP-1; no change in TAGs and Chol. In the liver: increase in MGO and TAG; no change in Glo1 (mRNA and activity) and Chol; increase in oxidative stress (TBARS ↑, GSH/GSSG ↓, GPx ↓); In the muscle: increase in TAGs. |

In the model of postmenopausal MetS: MGO, TAGs and oxidative stress in the liver ↑ |

[85]/2021 |

| Male WR divided into four groups: (1) control (Ct) with standard diet A03 (5% triglycerides and 45% carbohydrates) (2) methylglyoxal group (MG) with standard diet and MGO administration (rats fed 75 mg MGO kg-1 daily for 18 weeks) (3) high-fat diet-fed group (HFD) (40% triglycerides and 10% carbohydrates) (4) high-fat diet group with MGO supplementation (rats fed 75 mg MGO kg-1 daily for 18 weeks) (HFDMG) |

Effect of MGO supplementation (HFDMG group compared to control and/or MG or HFD rats); In blood plasma: increase in NEFA; decrease in albumin; decrease in adiponectin (as compared to raised adiponectin in HFD). In the liver: increase in inflammatory cells (F4/80 ↑—a marker of macrophages/Kupffer cells); increase in MAGEs (MG-H1 ↑, CEL ↑, but ArgP=); decrease in insulin receptor phosphorylation at Tyr1163; decrease in phosphorylation of ACC (ACC activity ↑);decrease in phosphorylation of AMPK (AMPK activity ↓) decrease in cardiolipin 70:2; increase in expression of FAS and AceCS; no change in membrane RAGE; no change in Glo1 expression (but Glo1 activity ↑ in MG; Glo1 activity ↓ in HFDMG) |

Upon MGO supplementation in the liver: inflammation, MAGE, IR, ACC ↑ AMPK ↓ IR ↑ |

[82]/2019 |

| Male C57BL/6J mice divided into 8 groups: Study 1 (mice fed for 16 weeks with): (1) low-fat diet (10% fat energy) (LF) (2) very-high-fat diet (60% fat energy) (VHF) (3) very-high-fat diet with 0.25% genistein (VHF-G). Study 2 (mice fed for 18 weeks with): (4) low-fat diet (10% fat energy) (LF) (5) moderately high-fat diet (HF) (6) moderately high-fat diet with MGO (110–145 mg/kg/day) (HFM) (7) moderately high-fat diet with MGO and 0.067% genistein (HFM-GL) (8) moderately high-fat diet with MGO and 0.2% genistein (HFM-GH) |

Genistein effect (VHF-G vs. VHF and HFM-GH vs. HFM); In blood plasma: decrease in MGO, AGEs, Glc, Chol, ALT, AST. In the liver and kidney: decrease in AGEs; increase in Glo1/2 and aldose reductase expression; decrease in RAGE expression. In the liver: decrease in TAGs level. |

Upon genistein supplementation in the liver Glo1/2, TAGs, RAGE and AGEs ↓ |

[86]/2019 |

| (1) Primary rat hepatocytes (isolated from WR) (PRH) incubated with Glc (8 mM) and inulin (0.12%) with or without inulinase in the absence or presence of insulin for up to 4 h. (2) PRH incubated with Glc (8 mM) and inulin (0.12%) and MGO (20 µM) in the absence or presence of insulin for 4 h. |

Effects of Fru delivery in PRH (in comparison with PRH exposed only to Glc): around 2-fold increase in MGO in hepatocytes. Effects of Fru delivery or MGO exposition in PRH: increase in phosphorylation of MKK7, JNK and serine307 of IRS-1 (in the absence and presence of insulin); decrease in insulin-stimulated tyrosine phosphorylation of IRS-1 and IRS-2. |

Upon Fru treatment in rat hepatocytes: MGO ↑ Upon Fru/MGO treatment in rat hepatocytes: IR ↑ |

[79]/2013 |

| Liver cirrhosis | |||

| (1) Male WR treated with CCl4 and phenobarbital for 8 weeks (early cirrhosis without ascites) or 12–14 weeks (advanced cirrhosis with ascites) (2) Male WR treated with CCl4 for 12–14 weeks, and Glo1 inhibitor (ethyl pyruvate—EP) starting from week 8. Primary rat hepatocytes (pHEP), primary hepatic stellate cells (pHSC) and primary liver sinusoidal endothelial cells (pLSEC) isolated from control and cirrhotic WR Normal hepatic stellate cells (HSZ-B-S1) |

In comparison with pHEP: decreased Glo1 expression in pHSC and pLSEC derived from control WR. In the whole liver, and pHEP, pHSC and pLSEC in cirrhosis (in comparison with healthy WR): decreased Glo1 expression (and lower in advanced cirrhosis as compared to early cirrhosis). In pHSC and pLSEC in cirrhosis (in comparison with healthy WR): decreased Glo1 activity. In the whole liver and pHEP in cirrhosis (in comparison with healthy WR): increased Glo1 activity In the whole liver in cirrhosis (in comparison with healthy WR): increased MGO level (and higher increase in advanced cirrhosis as compared to early cirrhosis) Upon LPS induction of HSZ-B-S1: increase in Glo1 activity. Upon EP or MGO treatment of LPS-induced HSZ-B-S1: decrease in TNF-α, collagen-I and α-SMA. Upon EP treatment of LPS-induced HSZ-B-S1: decrease in LPS-induced NF-κB stimulation, inhibition of LPS-induced reduction of Nrf2, reduction of LPS-induced pERK, no effect on ERK expression. Effect of EP treatment on cirrhotic WR (compared to cirrhotic livers without EP treatment): reduction of fibrotic tissue, reduction of α-SMA, TGF-β, NF-κB expression, increase in Nrf2 expression. |

In the model of cirrhosis: in the liver MGO ↑ in the liver and liver cells Glo1 expression ↓ in the liver and hepatocytes Glo1 activity ↑ |

[89]/2017 |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | |||

| Human HCC cell lines: Huh-7, HepG2 and Hep3B. |

Effect of 1 µM MGO on Huh-7 and HepG2 cells (but not Hep3B): inhibition of cells adhesion to collagen, and invasion through Matrigel (via promoting p53 localization in the nucleus by MGO). |

Upon MGO treatment: attenuation of cancer cells invasiveness |

[90]/2013 |

| Human HCC cell lines: Hep3B, SK-HEP-1 and SMMC-7721 |

Effect of Glo1 knock-down in Hep3B, SK-HEP-1 and SMMC-7721 cell lines: inhibition of the cells proliferation; Effect of Glo1 over-expression in Hep3B, SK-HEP-1 and SMMC-7721 cell lines: no effect on the cells growth. |

Upon Glo1 silencing: inhibition of cancer cells proliferation |

[91]/2014 |

| Human HCC cell lines: Huh-7 and HepG2 Murine hepatocyte cell line AML12 |

In comparison with normal AML12 cells: Glo1 up-regulation in Huh-7 cells (at mRNA, protein and activity levels); Glo1 up-regulation in HepG2 cells (only at mRNA level); Effects of Glo1 inhibition in Huh-7 cells (by 1–20 mM ethyl pyruvate or 1–10 µM BrBzGSHCp2): reduction of proliferation, migration and colony formation; decreased expression of PDGFR-β, VEGFR2, VEGF, pERK/ERK, NF-κB; increased expression of Nrf2 Effects of 2.5–10 µM sorafenib (a multi-tyrosine kinase inhibitor approved for the therapy of advanced HCC): increase in Glo1 and MGO. |

Upon Glo1 silencing: inhibition of cancer cells proliferation, migration and invasiveness |

[92]/2019 |

| Human HCC cell line HepG2 incubated with palmitic or oleic acids for 24 h. | Glo1 expression: decrease in oleic acid treated HepG2 cells. MGO concentration: increase in both palmitic and oleic acids treated HepG2 and their culture media. |

Upon FAs treatment of hepatoma cells: MGO ↑ Glo1 ↓ |

[87]/2018 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).