Submitted:

13 January 2025

Posted:

15 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

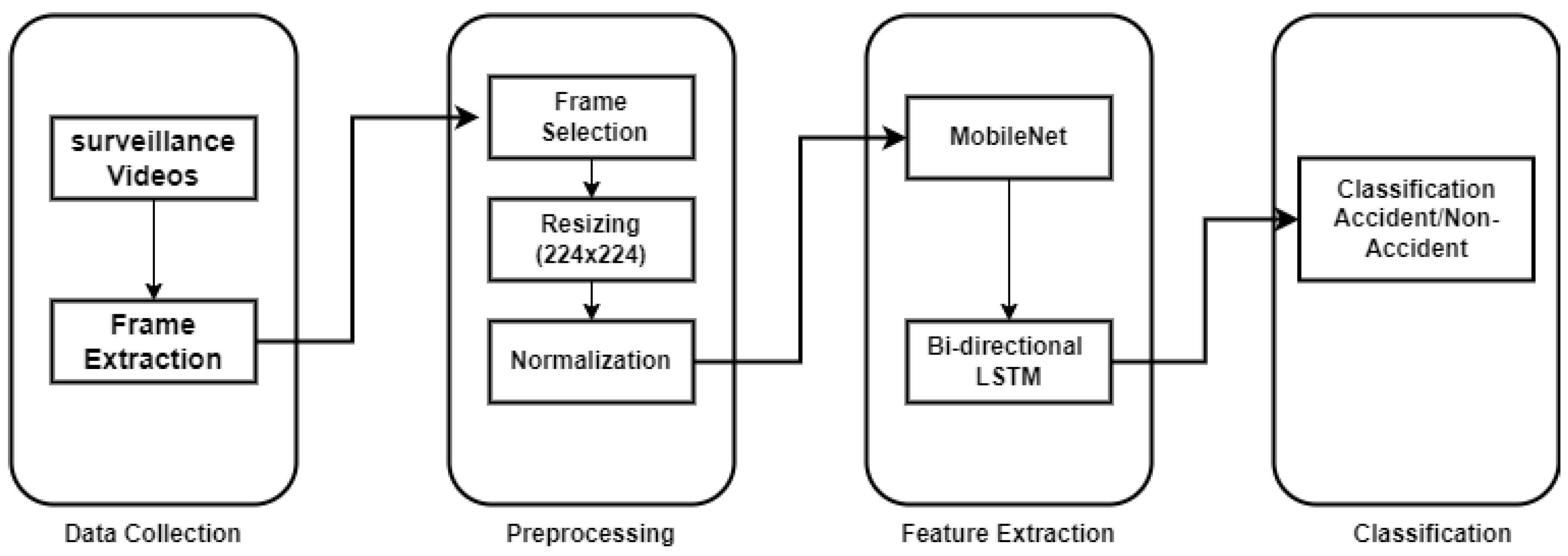

3. ARCHITECTURE & METHODOLOGY

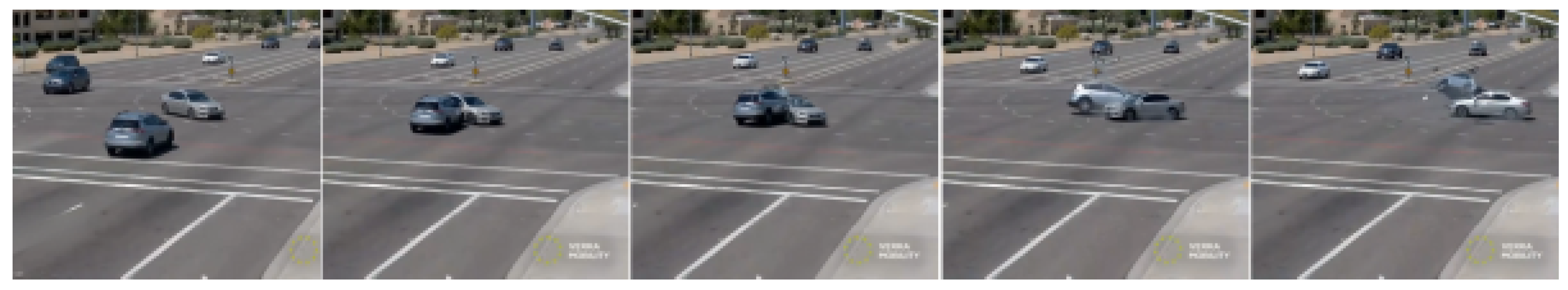

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Preprocessing

3.3. Spatial Feature Extraction

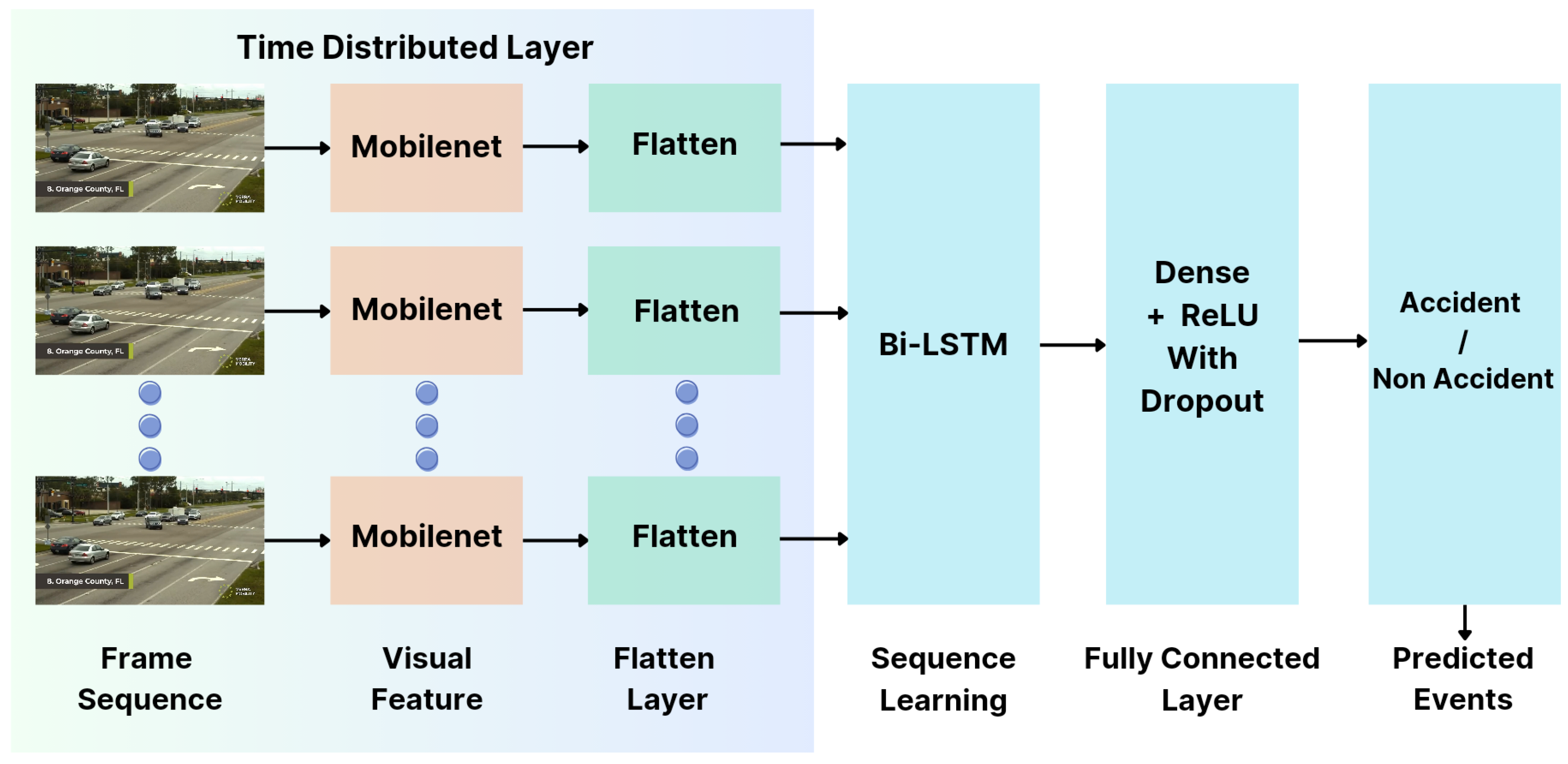

3.3.1. MobileNet & ImageNet

3.4. Learning Algorithm

3.4.1. Model Description

| Layer | Neurons | Activation | Dropout |

|---|---|---|---|

| Input | 2257920 | N/A | N/A |

| TimeDistributed | N/A | N/A | 0.25 |

| TimeDistributed | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Bidirectional LSTM | 64 | N/A | 0.25 |

| Dense | 256 | ReLU | 0.25 |

| Dense | 128 | ReLU | 0.25 |

| Dense | 64 | ReLU | 0.25 |

| Dense | 32 | ReLU | N/A |

| Output | 2 | Sigmoid | N/A |

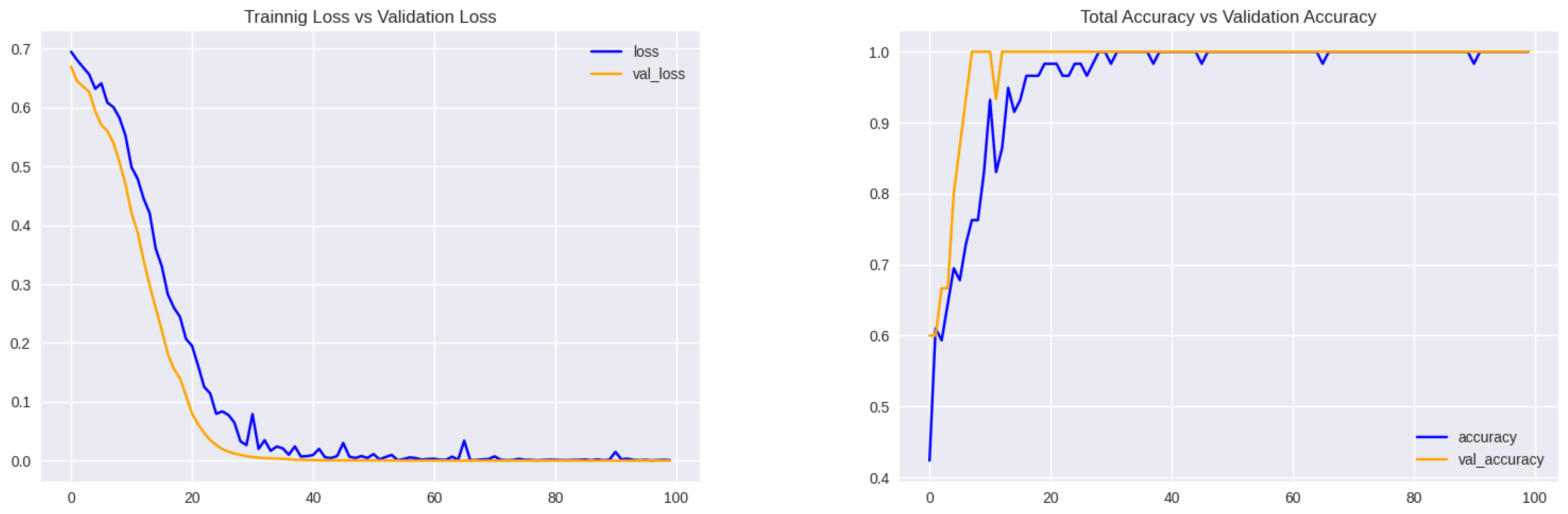

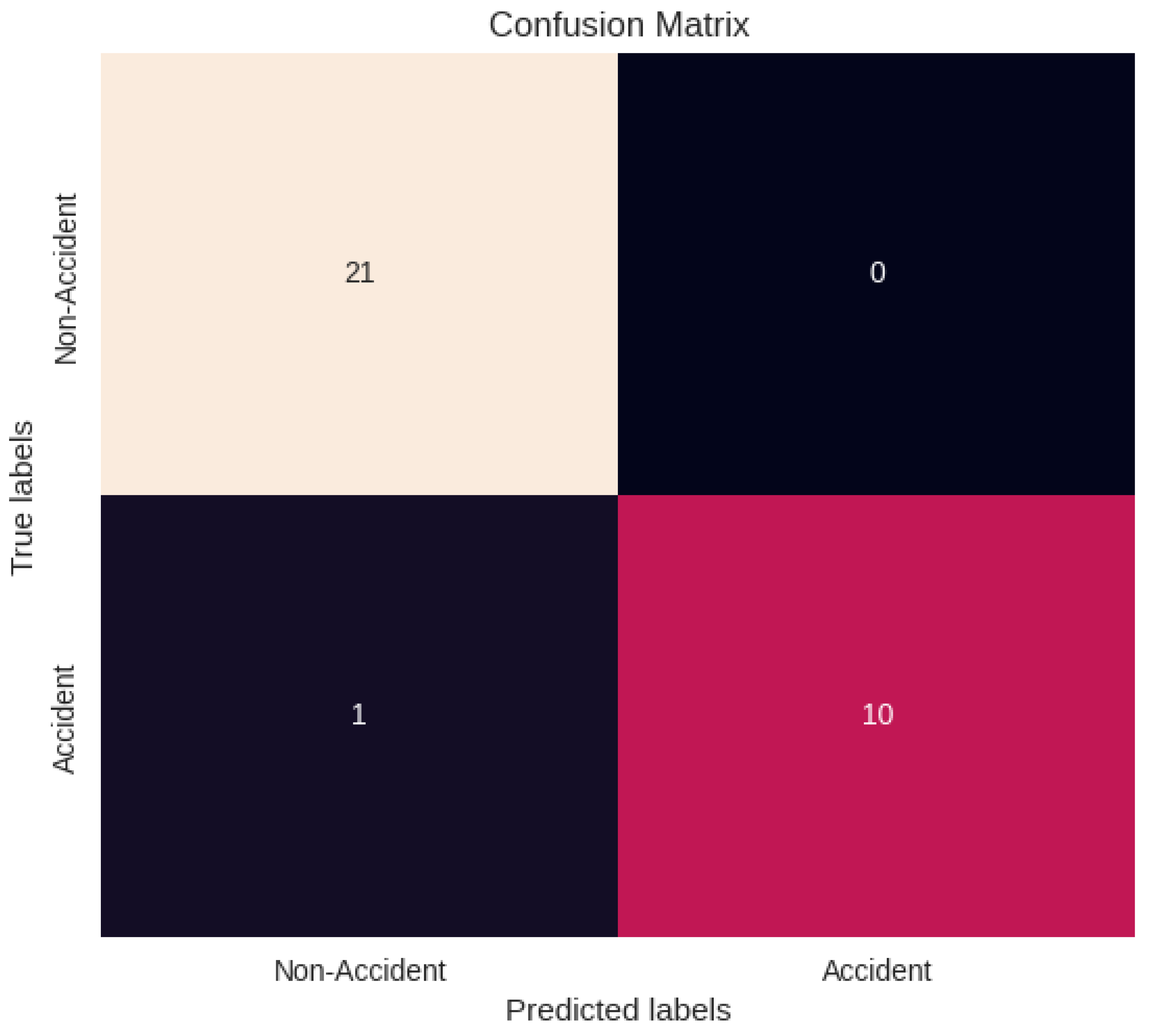

4. Result & Analysis

| Class | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | Support |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Accident | 0.95 | 1.00 | 0.98 | 21 |

| Accident | 1.00 | 0.91 | 0.95 | 11 |

| Macro Avg | 0.98 | 0.95 | 0.96 | 32 |

| Weighted Avg | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 32 |

5. Conclusions & Future Works

Acknowledgments

References

- Brake. “Global road safety statistics, [Online]. Available: https://www.brake.org.uk/get-involved/take-action/mybrake/knowledge-centre/global-road-safety. [Accessed: 19-Dec-2023].

- Nivolianitou, Z.; Leopoulos, V.; Konstantinidou, M. Comparison of techniques for accident scenario analysis in hazardous systems. Journal of Loss Prevention in the Process Industries 2004, 17, 467–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijjina, E.P.; Chand, D.; Gupta, S.; Goutham, K. Computer vision-based accident detection in traffic surveillance. In Proceedings of the 2019 10th International conference on computing, communication and networking technologies (ICCCNT). IEEE; 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Yanbin, Y.; Lijuan, Z.; Mengjun, L.; Ling, S. Early warning of traffic accident in Shanghai based on large data set mining. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Intelligent Transportation, Big Data & Smart City (ICITBS). IEEE; 2016; pp. 18–21. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, S.; Sunny, S.J.; Roney, R.M. Accident Detection Using Convolutional Neural Networks. 2019 International Conference on Data Science and Communication (IconDSC), 2019; 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- HD, A.K.; Prabhakar, C. Vehicle abnormality detection and classification using model based tracking. International Journal of Advanced Research in Computer Science 2017, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Svenson, O. Accident and incident analysis based on the accident evolution and barrier function (AEB) model. Cognition, Technology & Work 2001, 3, 42–52. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.F.; Xie, M.; Chin, K.S.; Fu, X.J. Accident analysis model based on Bayesian Network and Evidential Reasoning approach. Journal of Loss Prevention in the Process Industries 2013, 26, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elahi, M.M.L.; Yasir, R.; Syrus, M.A.; Nine, M.S.Z.; Hossain, I.; Ahmed, N. Computer vision based road traffic accident and anomaly detection in the context of Bangladesh. In Proceedings of the 2014 International Conference on Informatics, Electronics & Vision (ICIEV). IEEE; 2014; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, H.; Reddy, R.K.; Karthik, A. S-CarCrash: Real-time crash detection analysis and emergency alert using smartphone. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Connected Vehicles and Expo (ICCVE). IEEE; 2016; pp. 36–42. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A.; Deb, K. Categorization of actions in soccer videos using a combination of transfer learning and Gated Recurrent Unit. ICT Express 2022, 8, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarma, M.S.; Deb, K.; Dhar, P.K.; Koshiba, T. Traditional Bangladeshi sports video classification using deep learning method. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PACKT Books. What is transfer learning? | PACKT Books. [Online], 2023. [Accessed: 08-Dec-2023].

- Harvey, M. Creating Insanely Fast Image Classifiers with MobileNet in TensorFlow, 2017. Accessed: 08-Dec-2023.

- Website. Accessed: 08-Dec-2023.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).