Submitted:

14 January 2025

Posted:

14 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

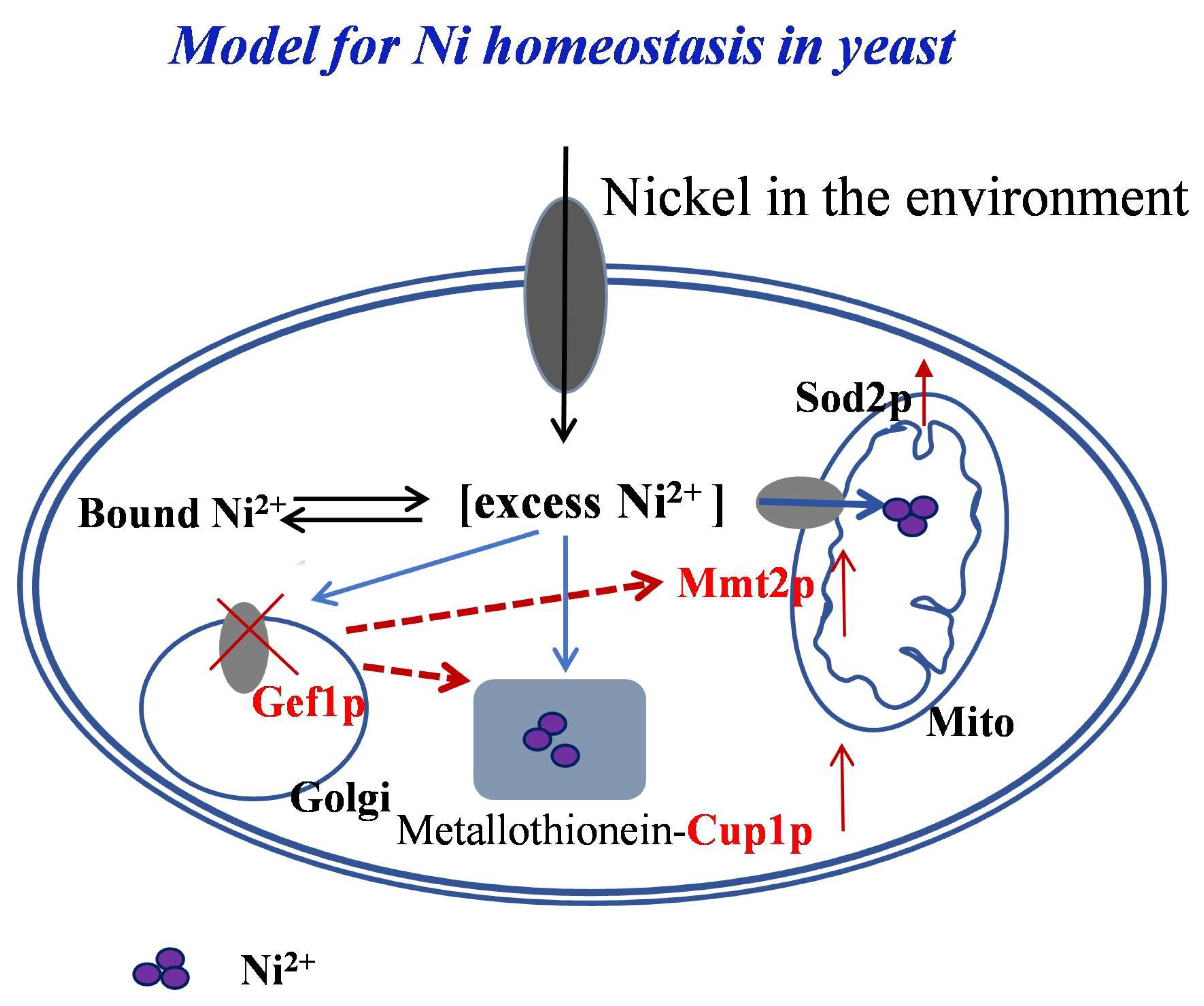

Nickel is a trace element essential for human life. Currently, studies on the metabolism and function of nickel ions mainly focus on prokaryotes, while the role of nickel ions in eukaryotes is still being explored. In this study, we found for the first time that GEF1 which encodes Gef1p, a chloride transport protein located in the Golgi membrane, is involved in nickel ion metabolism in yeast. The GEF1 knockout strain (gef1∆) showed strong resistance to excess nickel ions, and the content of nickel ions in gef1∆ cells was significantly elevated. The results of transcriptomics analysis showed significant upregulation of MMT2 and CUP1 in gef1∆ cells supplemented with nickel. Both MMT2 and CUP1 overexpressed in the gef1∆ strain showed a growth advantage on nickel media. Nickel ion content in the mitochondria of cells overexpressing MMT2 was significantly elevated, and the levels of reactive oxygen species were significantly decreased in strains overexpressing either the MMT2 or CUP1 genes. This study reveals that the GEF1 gene plays an important role in nickel homeostasis, and that upregulation of MMT2 and CUP1 is critical for gef1∆ strains to counteract ROS formation and growth defect by nickel ions.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Yeast Strains, Culture Media, and Growth Assays

2.2. Plasmid Manipulation

2.3. Western Blot Nalysis

2.4. Metal Measurement

2.5. Quantitative PCR

2.6. Measurement of Intracellular ROS Level

2.7. Fluorescence Microscopy

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

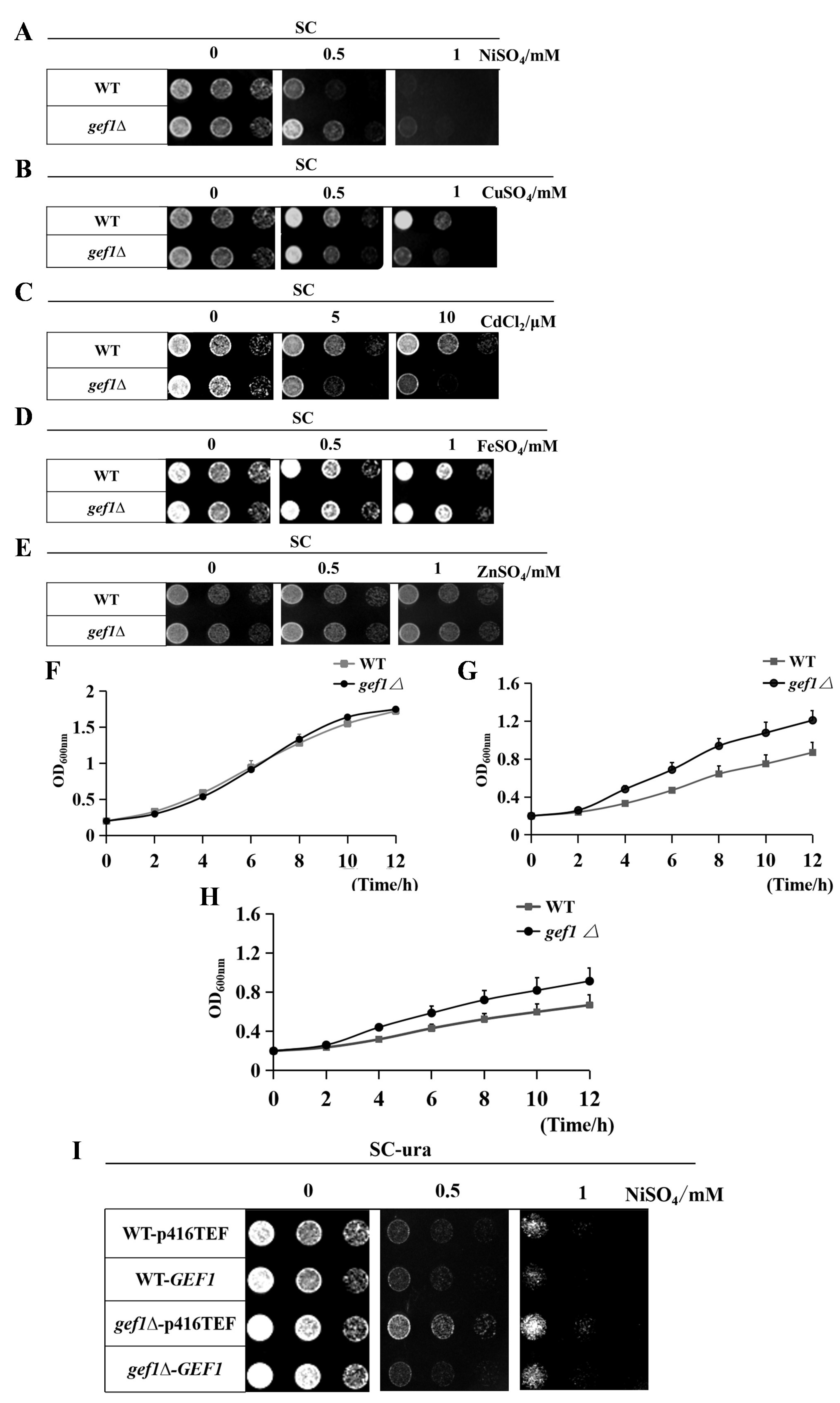

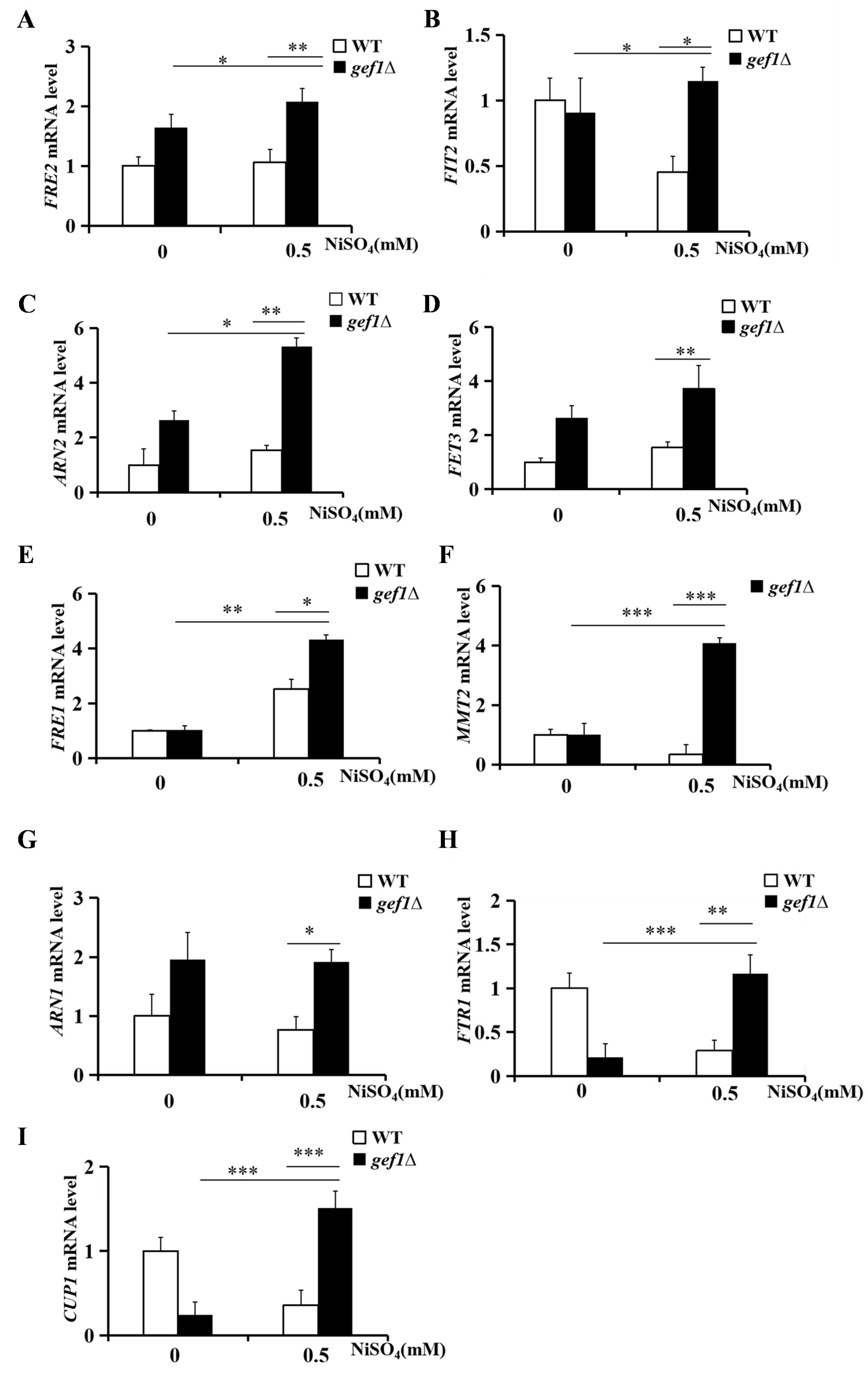

3.1. Gef1p Is a New Molecular Factor Involved in Nickel Ion Metabolism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae

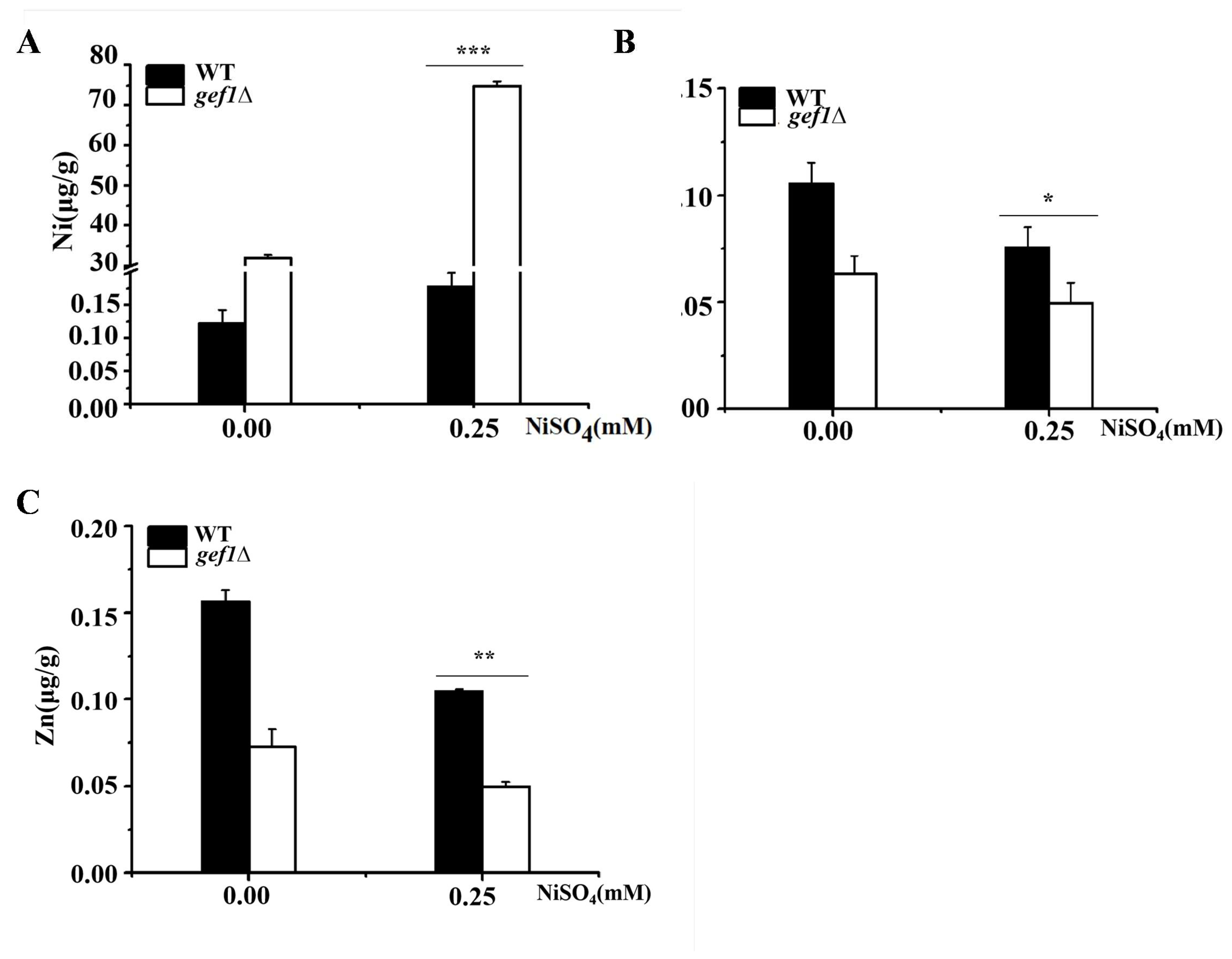

3.2. GEF1 Deletion Significantly Increases the Nickel Content in Cells Under Condition of Nickel Excess

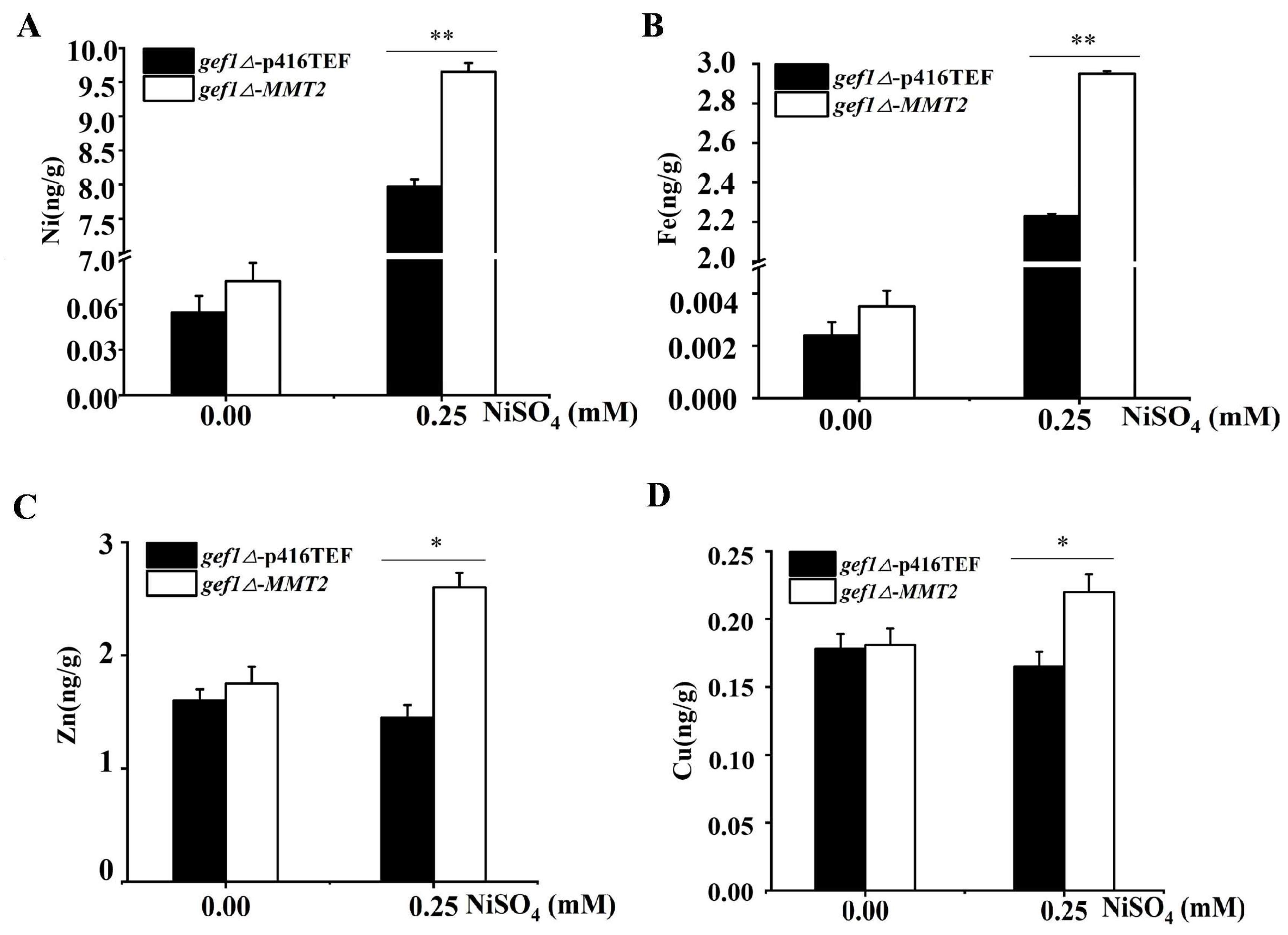

3.3. MMT2 Transports Excess Nickel to Mitochondria and Changes the Distribution of Nickel Ions

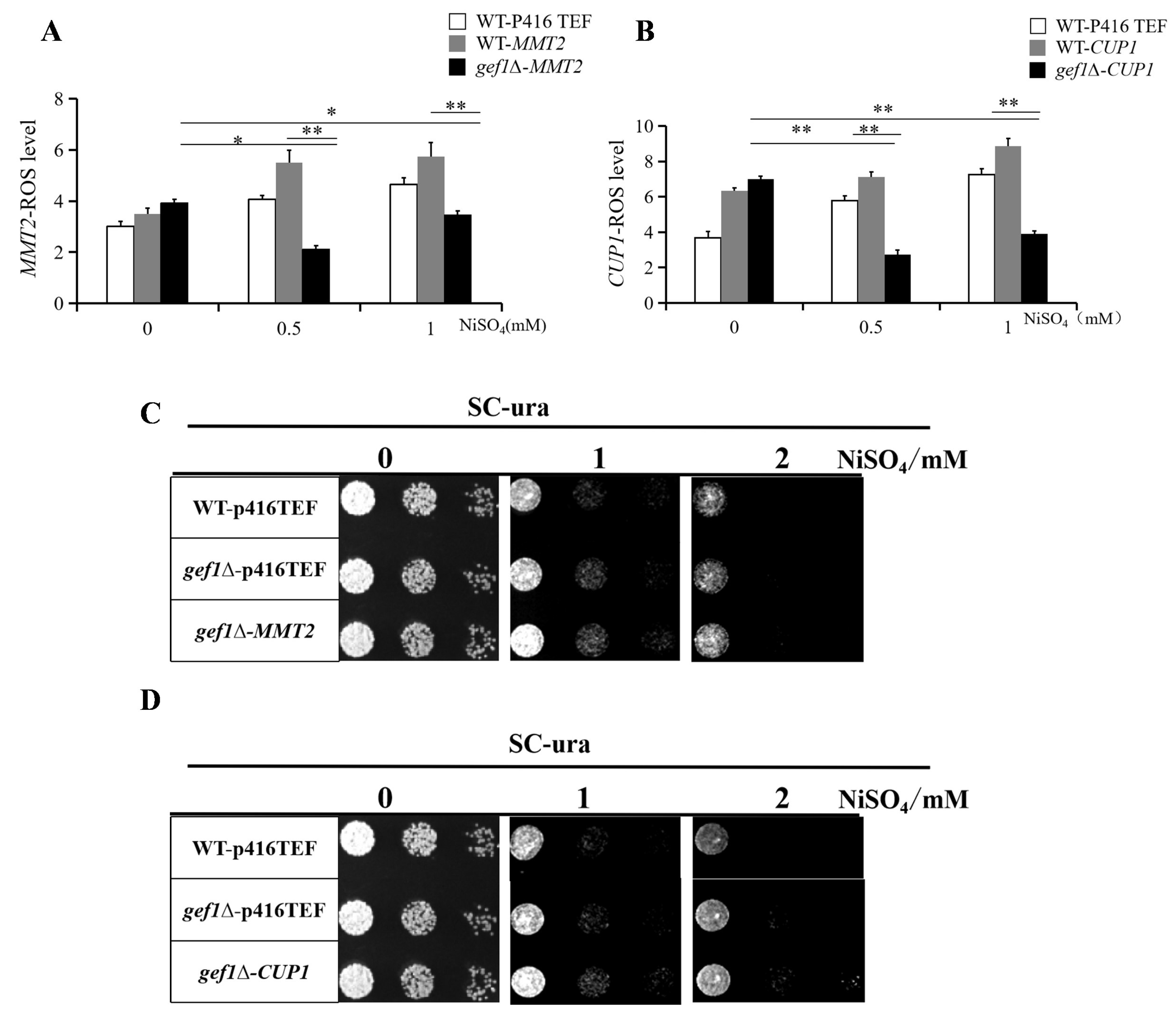

3.4. Over-Expression of MMT2/CUP1 Reduces Intracellular ROS Level

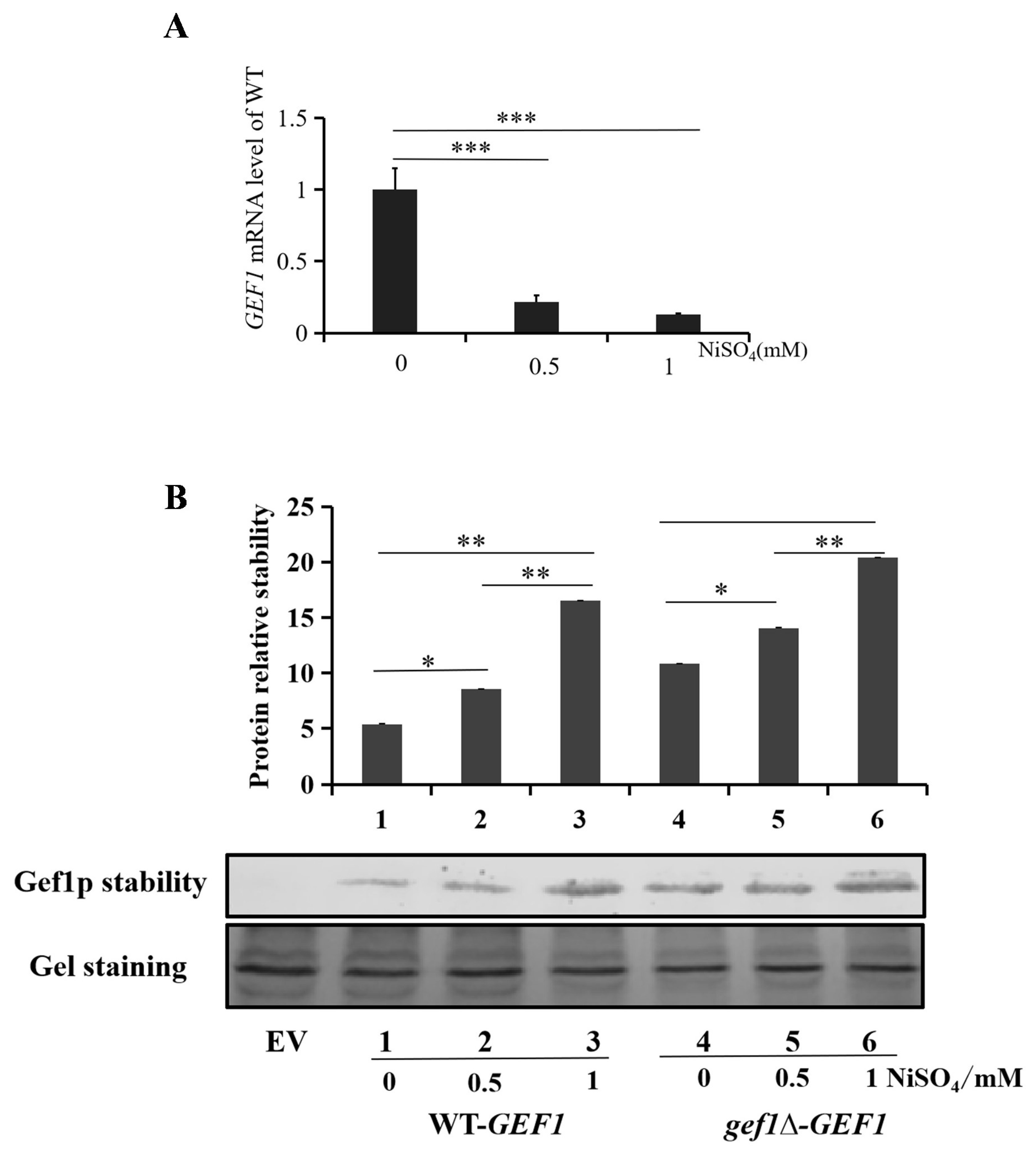

3.5. Nickel Ions Play an Important Role in Regulating mRNA and Protein Expression of GEF1

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anke, M.; Groppel, B.; Kronemann, H.; Grün, M. Nickel--an Essential Element. IARC Sci Publ. 1984, 339–365. [Google Scholar]

- Trumbo, P.; Yates, A.A.; Schlicker, S.; Poos, M. Dietary Reference Intakes: Vitamin A, Vitamin K, Arsenic, Boron, Chromium, Copper, Iodine, Iron, Manganese, Molybdenum, Nickel, Silicon, Vanadium, and Zinc. J Am Diet Assoc. 2001, 101, 294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, K.K.; Honnutagi, R.; Mullur, L.; Reddy, R.C.; Das, S.; Majid, D.S.A.; Biradar, M.S. Chapter 26 - Heavy Metals and Low-Oxygen Microenvironment—Its Impact on Liver Metabolism and Dietary Supplementation In Dietary Interventions in Liver Disease; Watson, R.R., Preedy, V.R., Eds.; Academic Press, 2019; pp. 315–332 ISBN 978-0-12-814466-4.

- Genchi, G.; Carocci, A.; Lauria, G.; Sinicropi, M.S.; Catalano, A. Nickel: Human Health and Environmental Toxicology. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020, 17, 679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slotkin, T.A.; Skavicus, S.; Card, J.; Levin, E.D.; Seidler, F.J. Diverse Neurotoxicants Target the Differentiation of Embryonic Neural Stem Cells into Neuronal and Glial Phenotypes. Toxicology. 2016, 372, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, J.; Shi, X.; Li, Q.; Zhao, M.; Wang, L.; Lee, J.; Tao, M.; Wu, X. A Novel Functional Role of Nickel in Sperm Motility and Eukaryotic Cell Growth. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2019, 54, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvi, A.; Parveen, S.; Khan, S.; Naseem, I. Nickel Toxicology with Reference to Male Molecular Reproductive Physiology. Reprod Biol. 2020, 20, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noguromi, M.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Sato, K.; Oyakawa, S.; Okamoto, K.; Murata, H.; Tsukuba, T.; Kadowaki, T. Rab44 Deficiency Induces Impaired Immune Responses to Nickel Allergy. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambelli, B.; Ciurli, S. Nickel and Human Health. Met Ions Life Sci. 2013, 13, 321–357. [Google Scholar]

- Can, M.; Armstrong, F.A.; Ragsdale, S.W. Structure, Function, and Mechanism of the Nickel Metalloenzymes, CO Dehydrogenase, and Acetyl-CoA Synthase. Chem Rev. 2014, 114, 4149–4174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobley, H.L.; Garner, R.M.; Bauerfeind, P. Helicobacter Pylori Nickel-Transport Gene nixA: Synthesis of Catalytically Active Urease in Escherichia Coli Independent of Growth Conditions. Mol Microbiol. 1995, 16, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, A.J.; Guerra, C.; Phung, V.; Nair, S.; Seetharam, R.; Satir, P. GEF1 Is a Ciliary Sec7 GEF of Tetrahymena Thermophila. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 2009, 66, 483–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, S.; Guerra, C.; Satir, P. A Sec7-Related Protein in Paramecium. FASEB J. 1999, 13, 1249–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greene, J.R.; Brown, N.H.; DiDomenico, B.J.; Kaplan, J.; Eide, D.J. The GEF1 Gene of Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Encodes an Integral Membrane Protein; Mutations in Which Have Effects on Respiration and Iron-Limited Growth. Mol Gen Genet. 1993, 241, 542–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flis, K.; Bednarczyk, P.; Hordejuk, R.; Szewczyk, A.; Berest, V.; Dolowy, K.; Edelman, A.; Kurlandzka, A. The Gef1 Protein of Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Is Associated with Chloride Channel Activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002, 294, 1144–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaxiola, R.A.; Yuan, D.S.; Klausner, R.D.; Fink, G.R. The Yeast CLC Chloride Channel Functions in Cation Homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998, 95, 4046–4050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Rodríguez, A.; Trejo, A.C.; Coyne, L.; Halliwell, R.F.; Miledi, R.; Martínez-Torres, A. The Product of the Gene GEF1 of Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Transports Cl- across the Plasma Membrane. FEMS Yeast Res. 2007, 7, 1218–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasvari, Z.; Kovalev, N.; Nagy, P.D. The GEF1 Proton-Chloride Exchanger Affects Tombusvirus Replication via Regulation of Copper Metabolism in Yeast. J Virol. 2013, 87, 1800–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Alonso, L.; Romero, A.M.; Martínez-Pastor, M.T.; Puig, S. Iron Regulatory Mechanisms in Saccharomyces Cerevisiae. Front Microbiol. 2020, 11, 582830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.E.; Lindahl, P.A. CUP1 Metallothionein from Healthy Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Colocalizes to the Cytosol and Mitochondrial Intermembrane Space. Biochemistry. 2023, 62, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winzeler, E.A.; Shoemaker, D.D.; Astromoff, A.; Liang, H.; Anderson, K.; Andre, B.; Bangham, R.; Benito, R.; Boeke, J.D.; Bussey, H.; et al. Functional Characterization of the S. Cerevisiae Genome by Gene Deletion and Parallel Analysis. Science. 1999, 285, 901–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, R.; Sun, J.; Simth, N.; Zhao, M.; Lee, J.; Ke, Q.; Wu, X. A Novel Assessment System of Toxicity and Stability of CuO Nanoparticles via Copper Super Sensitive Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Mutants. Toxicol In Vitro. 2020, 69, 104969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mumberg, D.; Müller, R.; Funk, M. Yeast Vectors for the Controlled Expression of Heterologous Proteins in Different Genetic Backgrounds. Gene. 1995, 156, 119–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bian, J.; Wang, L.; Wu, J.; Simth, N.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Wu, X. MTM1 Plays an Important Role in the Regulation of Zinc Tolerance in Saccharomyces Cerevisiae. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2021, 66, 126759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gietz, R.D.; Schiestl, R.H.; Willems, A.R.; Woods, R.A. Studies on the Transformation of Intact Yeast Cells by the LiAc/SS-DNA/PEG Procedure. Yeast. 1995, 11, 355–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, N.; Xu, Y.; Smith, N.; Chen, H.; Guo, Z.; Lee, J.; Wu, X. MTM1 Displays a New Function in the Regulation of Nickel Resistance in Saccharomyces Cerevisiae. Metallomics. 2022, 14, mfac074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furukawa, S.; Fujita, T.; Shimabukuro, M.; Iwaki, M.; Yamada, Y.; Nakajima, Y.; Nakayama, O.; Makishima, M.; Matsuda, M.; Shimomura, I. Increased Oxidative Stress in Obesity and Its Impact on Metabolic Syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2004, 114, 1752–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Bertram, S.; Kaplan, J.; Jia, X.; Ward, D.M. The Mitochondrial Iron Exporter Genes MMT1 and MMT2 in Yeast Are Transcriptionally Regulated by Aft1 and Yap1. J Biol Chem. 2020, 295, 1716–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soboh, B.; Adrian, L.; Stripp, S.T. An in Vitro Reconstitution System to Monitor Iron Transfer to the Active Site during the Maturation of [NiFe]-Hydrogenase. J Biol Chem. 2022, 298, 102291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis-Kaplan, S.R.; Askwith, C.C.; Bengtzen, A.C.; Radisky, D.; Kaplan, J. Chloride Is an Allosteric Effector of Copper Assembly for the Yeast Multicopper Oxidase Fet3p: An Unexpected Role for Intracellular Chloride Channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998, 95, 13641–13645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, C.M.; Schreiter, E.R.; Stultz, C.M.; Drennan, C.L. Structural Basis of Low-Affinity Nickel Binding to the Nickel-Responsive Transcription Factor NikR from Escherichia Coli. Biochemistry. 2010, 49, 7830–7838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baksh, K.A.; Pichugin, D.; Prosser, R.S.; Zamble, D.B. Allosteric Regulation of the Nickel-Responsive NikR Transcription Factor from Helicobacter Pylori. J Biol Chem. 2021, 296, 100069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.-H.; Won, H.-S.; Lee, M.-H.; Lee, B.-J. Effects of Salt and Nickel Ion on the Conformational Stability of Bacillus Pasteurii UreE. FEBS Lett. 2002, 522, 135Thank you for your reply. We have updated the manuscript and system based on your email. We will proceed the manuscript as soon as possible–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).