1. Introduction

1.1. Background

Malaria is a global disease affecting tropical and subtropical regions and, despite interventions and strategies aimed at malaria control, it contributes significantly to the global mortality rate [

1]. In 2022, 249 million estimated cases of malaria were recorded in Africa, which accounts for 93.6% of malaria-related morbidity, and 95.4% of malaria-related mortality, cases globally. Approximately 78.1% of the malaria-related deaths in Africa were recorded in children under 5 years of age, making this a vulnerable group for malaria infection. The highest percentage of cases was recorded in Nigeria, representing 26.8%, followed by The Democratic Republic of Congo, which accounts for 12.3%, 5.1% from Uganda and 4.2% from Mozambique [

2].

Ghana, also in the World Health Organisation (WHO) African region, accounts for 2.1% of recorded malaria cases (15th highest globally) and it is reported to have recorded a decline of malaria incidence of about 40% between 2015–2021 [

2]. Though malaria intervention and control measures are ongoing, malaria in Ghana accounts for over 30% of the overall outpatient cases recorded and remains one of the leading causes of death, making the disease a significant burden on the nation’s resources, which requires constant strategizing and re-strategizing of public health interventions to reduce or eliminate the impact of the disease [

3].

Malaria is classified in Ghana to be endemic, enduring, or continually occurring throughout the year. It has seasonal variations that are more prominent in the northern part of the country than the south [

4]. The period of transmission is found to be dependent on the dry and wet seasons, with the dry seasons (December to March) recording fewer transmissions. The wet season in the north (May to September) records the highest rainfall volumes in August, whereas in the north and middle belt of the country, it occurs from April to June and then again in September to November [

4]. The highest rates of malaria cases in the northern Ghana are recorded between July and November, whilst the south has a peak transmission period between May to November, with fewer cases recorded from May to June and higher case count recorded from October to November [

4].

According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [

5], climate and weather directly affect the rate of malaria transmission, and this effect may be reduced by the influence of both health care responses and socio-economic structures. Studies that have investigated the relationship between climatic factors and various vector borne infections globally provide evidence that supports the contention that climatic factors provide an enabling environment for mosquitos [

6]. Specifically in Ghana, some researchers have also contributed to understanding how malaria may be impacted by climate variability [

7,

8,

9] and point to the importance of further research to explore the nature of the relationship at the national and local level.

To further understand the climate-malaria relationships in Ghana, this paper aims to explore the nation’s climatic conditions that may enhance or suppress the spread of malaria and/or the malaria vector. The annual climate variability of Ghana’s climate zones [

10] will be examined with a view to determining the malaria situation in Ghana in different temperature, humidity and precipitation regimes.

To achieve the aims of this study, the investigation focuses on the compilation, critical analysis and contextualization of a new, regional malaria dataset in the context of climate metrics from Ghana. Such an assessment is of significant value on its own as the literature is currently lacking in such local level analyses of the climate-malaria relationship in Ghana. We also present and discuss these data with a view to informing more detailed and sophisticated environmental health analyses in future work.

1.2. Climate Variables and Malaria

In this section we present an overview of studies investigating the relationships between malaria and the key meteorological variables, and review studies that have proposed climatic zoning of Ghana.

1.2.1. Temperature

There are a range of results investigating temperature and malaria. Some studies have shown that temperatures above 34°C have a detrimental effect on the survival rate of the malaria parasite, thus slowing the transmission of the malaria disease [

11,

12,

13]. Some studies also found temperatures of 26–28°C to be optimum for malaria transmission [

14,

15], while others have identified 25°C as the optimum temperature for malaria transmission [

16]. Furthermore, this is 5–6°C lower than the estimated optimum range of around 30–31°C calculated elsewhere [

17]. These ranges mostly fall within the broader temperature window of a modelling study, which gave the range of 17–30°C as a suitable temperature range to support parasite development and malaria transmission [

13].

1.2.2. Precipitation

Some epidemiological studies show a strong correlation between precipitation and malaria cases [

7,

18,

19,

20], while others report the contrary [

21,

22,

23]. Though these studies do not state categorically the optimum range of rainfall volume needed for malaria transmission, the influence of rainfall on malaria can be understood as follows: higher volumes of recorded rainfall incidence have been linked to lower levels of malaria cases, which is most likely because of floods eliminating the vector breeding sites [

24,

25]; and extremely low rainfall will still provide a suitable environment for malaria vectors once there is some amount of water retained, even in the smallest pool during the phase of aquatic development of the mosquito vectors. Further, drought, which causes pools to dry up, does not necessarily lead to restricted malaria transmission as certain periods in the life cycle of the mosquito vector do not require pools to thrive [

25]. In summary, the influence of rainfall on mosquito vectors can be non-linear and is dependent on the stage of vector development at the point in time.

1.2.3. Humidity

Studies examining humidity and malaria suggests that when the mean monthly humidity falls below 55% or rises beyond 80%, the life span of the vector is reduced drastically with a corresponding effect on malaria transmission [

26,

27]. When the relative humidity is within optimum range of 55–80%, the life span of the adult mosquito is prolonged, leading to maturation and subsequent transmission of the infectious disease [

28].

1.2.4. Climate Zones in Ghana

The relationship that exists between climatic variability and malaria cases in Ghana is poorly understood with minimal investigation into the links [

7]. This points to the need for research to understand the role climate variability plays in Ghana and if there are opportunities to use enhanced knowledge of the relationship to inform evidence-based interventions for control or elimination.

One way of doing this could be through the lens of climatic zones. Several classifications of zones exist in Ghana based on objective criteria for zoning. Comparisons of these classifications show similarities in location which implies they are physically meaningful. For example, the Food and Agricultural Organisation (FAO) in 2005 established seven agro-ecological zones in the country: Sudan Savannah, Guinea Savannah, Transitional, Deciduous Forest, Moist Evergreen, Wet Evergreen, and Coastal Savannah [

29]. Another classification [

30] put the country under four climatic regions: Tropical Continental or Savannah; Wet Semi-Equatorial; South-western Equatorial; and Dry Equatorial. A more recent classification, explored further in this paper, is the analysis of Bessah et al. [

10]. They employed cluster analysis and principal component analysis to classify the country into three climatic zones – Savannah, Forest and Coastal – using long term (1976–2018) temperature, rainfall, and humidity data from the 22 synoptic stations located in Ghana (see

Section 2.3).

The Bessah et al. [

10] climatic zones will be used in this study to investigate how malaria cases vary in relation to the climatic conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

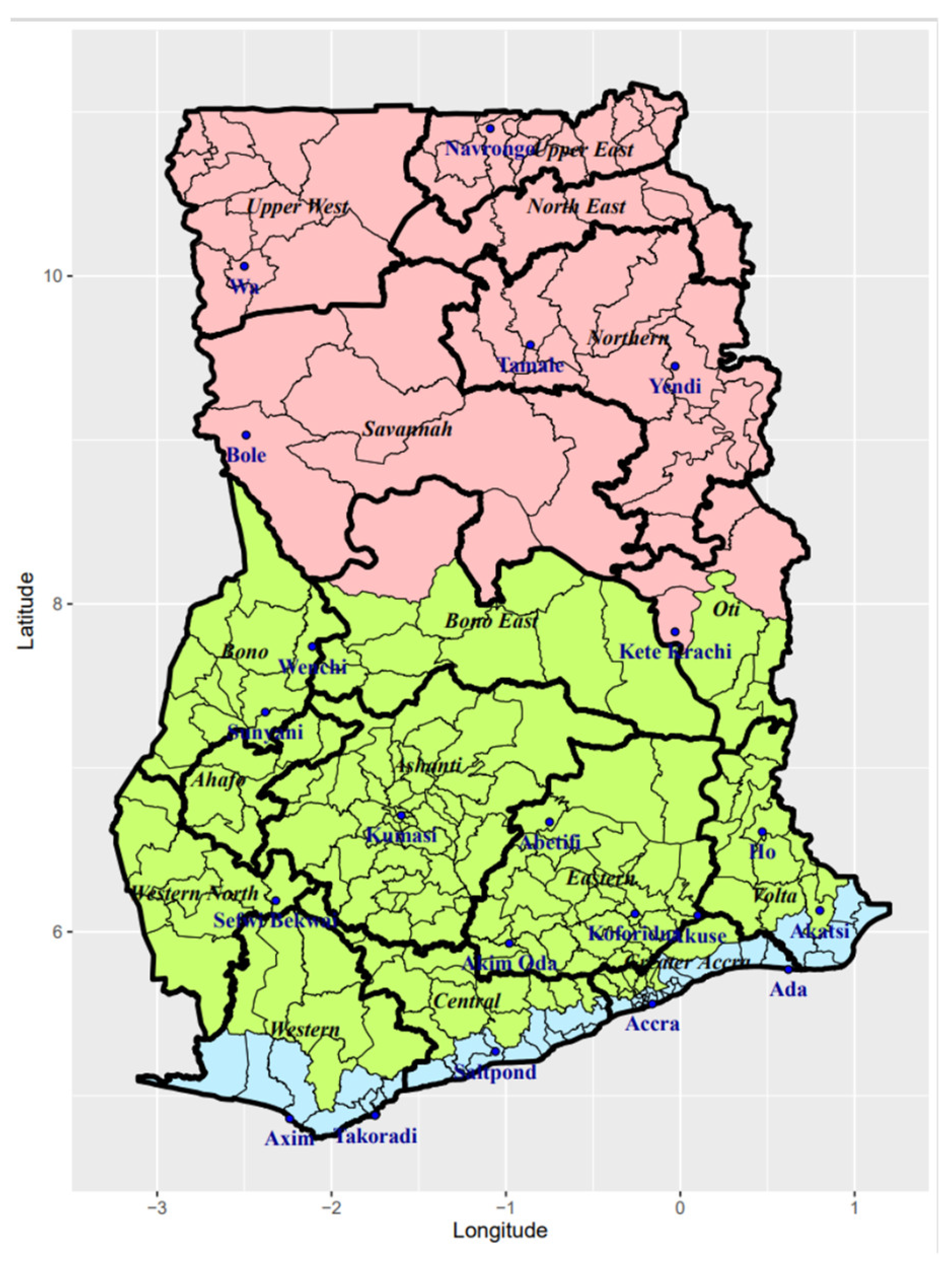

Ghana is a country in West Africa (

Figure 1) and is bordered in the north by Burkina Faso, east by Togo, west by Cote d’Ivoire, and south by the Gulf of Guinea. The country is situated approximately between latitudes 4.50°N and 11.50°N and longitude 3.50°W and 1.30°E with a total land area of 239,460 km

2 and a water area of 8,520 km

2 [

31].

Ghana’s population stood at 30,792,608 in 2021 with 50.7% females and 49.3% males. The country’s population has grown five-fold since independence in the year 1957 [

32]. Up to 2018, Ghana was formally divided into ten regions, namely: Greater Accra, Central, Eastern, Northern, Upper East, Upper West, Brong Ahafo, Western, Ashanti, and Volta. After December 27, 2018, four of those regions were subdivided to create 6 new regions: Western North, Ahafo, Bono, Bono East, Savannah, and North East (

Figure 1). This, however, did not alter the external borders of the country [

32]. The largest and smallest regions are Savannah and Greater Accra, respectively, and the most populous are Greater Accra and Ashanti while the least populous are Savannah and Ahafo (

Table 1). The regions, in turn, are made up of 261 districts, with Ashanti region having the highest number of districts and North East and Ahafo having the fewest districts [

32].

2.2. Malaria Case and Case Rate Data

Malaria case data at the district level was acquired from the Ghana Health Service and aggregated to the national and regional scale. The data span the period 2008–2022, which covers the point when the regions were redefined. Where regional boundaries changed, the case numbers were calculated for the new regions for the whole 2008–2022 window by aligning the districts, which did not change in 2018, with new regional boundaries.

There was also a change in reporting in some districts during this period: 1) some districts will have reported all fevers as malaria cases; 2) some will have reported results of random diagnostic testing to identify malaria cases; and 3) some will have changed from 1) to 2) during the period. It is not possible to unravel the potential influence of these changes on the data but, given the similarity of the national figures with other sources of data (e.g., World Health Organisation [

33]) we are confident that this is not a significant factor.

Malaria case incidence rates (i.e., cases per 1000 of population) were calculated at the national and regional level by using population census data for 2010 and 2021 [

32] with the population figures for the full 2008–2022 range calculated using linear interpolation or extrapolation. There was an approximate 2.1% population growth rate between the two census dates with a change from 24.7 million in 2010 to 30.8 million in 2021.

The malaria data are anonymous with no identification markers or any method by which to trace individuals that were infected with malaria. Nonetheless, ethical approval was sought and granted from the relevant bodies.

2.3. Meteorological Data

Daily and monthly climate data for 2008–2022 were acquired from the Ghana Meteorological Agency (GMet) across the 22 synoptic stations (

Table 2). The climate variables include maximum and minimum temperature, mean temperature, rainfall, and humidity. (Note that humidity data were only available up to 2018.) The different datasets were tested for validity and distribution with the Shapiro-Wilk test for normality, and monthly and annual means were calculated. Months that had more than 20% of the daily data missing were discarded. If the missing daily data was below the 20% threshold, the gap was filled with linear interpolation.

Climate variability is further explored by looking at the interannual patterns and annual cycles in the data, separated by climate zone, using descriptive statistics (e.g., box plots) and the implications for providing a favorable environment for malaria vectors and malaria transmission at large using simple inferential statistical techniques (e.g., Pearson’s correlation).

3. Results and Discussion

In this section we provide results from the analysis of the malaria and climate data. We investigate trends and patterns that may define a relationship between the variables and seek to understand how this reflects on the malaria situation in Ghana. The section concludes with correlation analyses to reveal an overview of relationships between the variables, both at the national and climatic zone levels, and contextualize the individual analysis of malaria data and climate data to show how the climate variability may be impacting on malaria.

3.1. Summary of Annual Malaria Cases 2008–2022

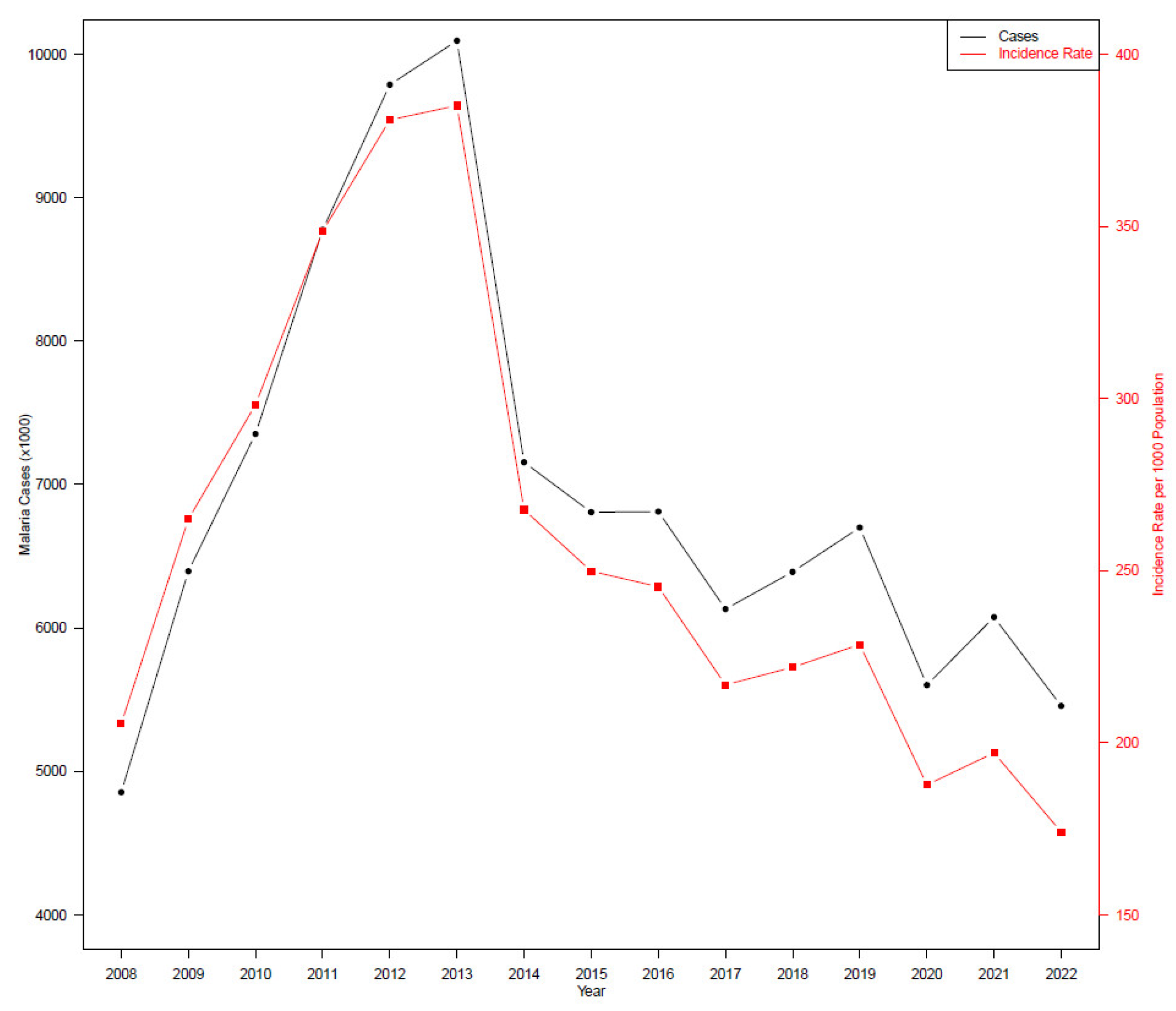

Figure 2 shows the annual malaria cases and incidence rate data at the national level. The data shows a steep increase in malaria cases from 2008–2013, followed by a sharp decline in 2014 and then a steady fall through to 2022.

This decline in cases may be partially attributed to malaria control programs and initiatives rolled out in Ghana, which include the Roll Back Malaria (RBM) programs and Ghana Malaria Operational Plan with grants and fundings from partner institutions ensuring nationwide coverage of these control strategies [

34]. The Roll Back Malaria initiative was first launched in 1999, with the aim of multi sectoral partnerships to ensure malaria treatment and prevention becomes readily and largely accessible. This led to the development of a ten-year National Malaria Strategic Plan from 2000 to 2010 aiming to reduce malaria morbidity and mortality by 50% [

35]. These plans have since been intensified with novel and more effective treatment plans; introduction of artemisinin-based combination therapy, indoor spraying, and administering anti-malarial prophylaxis to pregnant women at the antenatal clinics. The second phase of RBM became the updated strategic plan that was carried out from 2008–2015 as well as an updated National Malaria Control Strategic carried out for the years 2014–2020 [

35].

Whilst these strategies overlap with the decline in malaria cases in 2014 (

Figure 2) there is no strong evidence for a step change in intervention that could explain the drop in cases. This raises the question of whether climate variability could have been a significant driving factor of this decline alongside the RBM initiative. This will be investigated further with the climate analysis (Section 3.4).

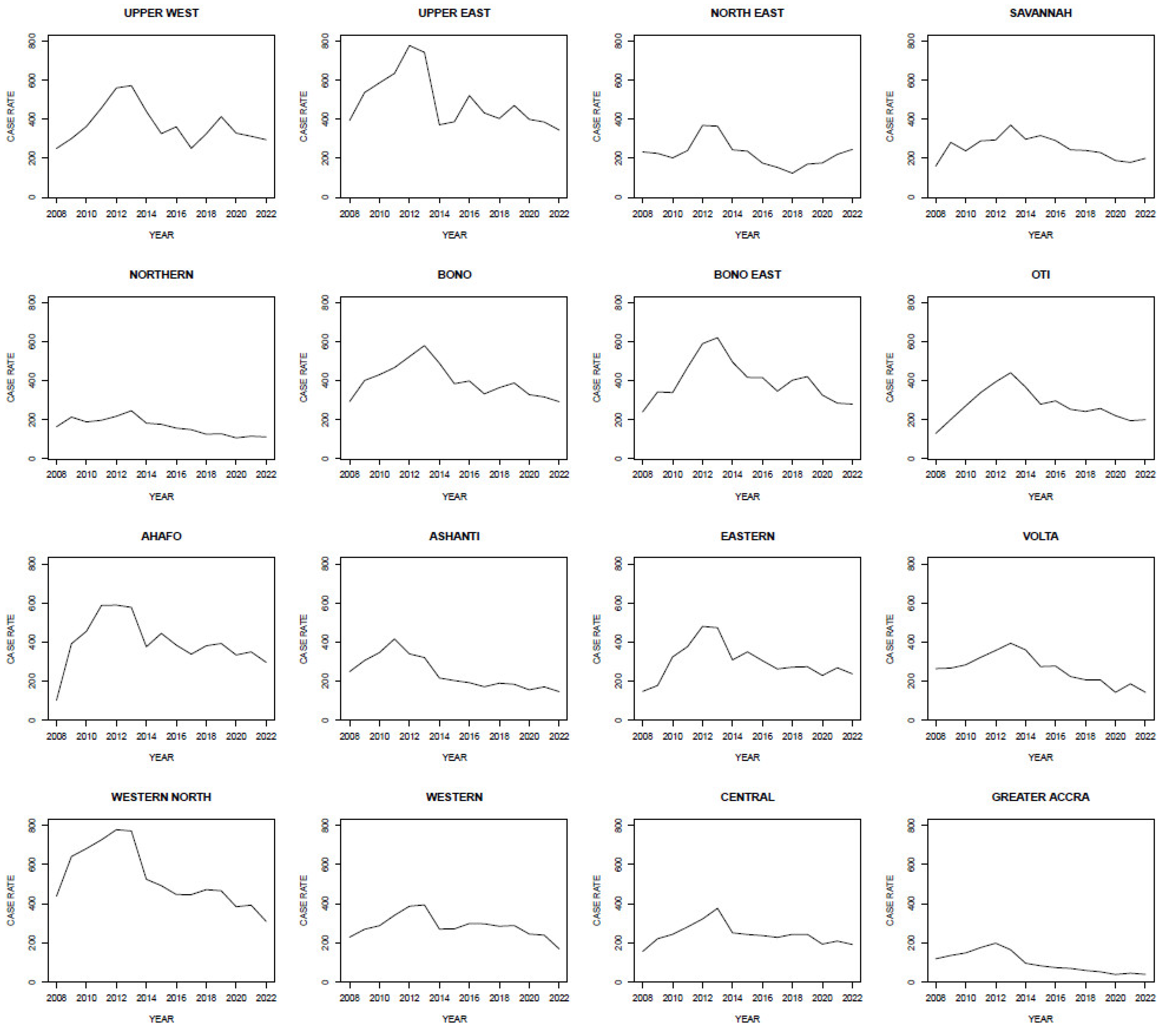

Figure 3 breaks down the malaria case rate data by the 16 administrative regions. The Western North region has the highest incidence rate followed by the Upper East region. These two regions also show the most pronounced drops in 2014. The Greater Accra region, the capital and most populous region of Ghana, shows the lowest incidence rate throughout the period 2008–2022.

Though this overview is important for regional planning and intervention strategies for malaria control, it is noted that the climate zones identified by Bessah et al. [

10] do not align well with the administrative regions. To further understand the dynamics of the malaria data, the districts have been assigned to the climate zones to replicate these zones as accurately as possible, indicated by the shading in

Figure 1.

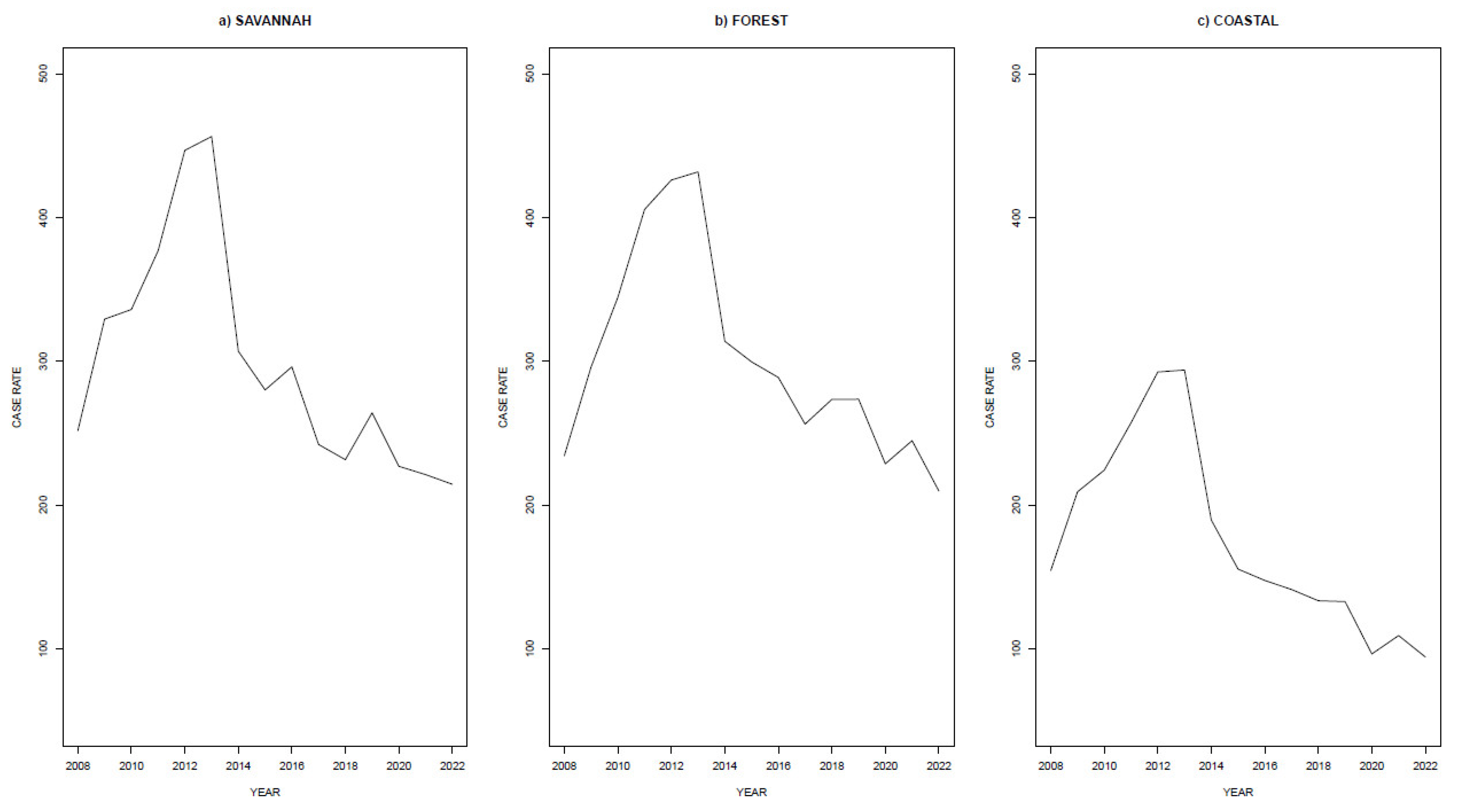

Figure 4 shows the result of this reclassification for the malaria incidence rate across the savannah, forest, and coastal climatic zones. It shows that the coastal zone recorded lower malaria case rates than the other two zones for 2008–2022. The Savannah climatic zone, on the other hand, recorded the highest case rates. It is also notable that the decline of malaria cases from the period 2014–2022 is seen across all climatic zones, similar to the pattern of the national cases.

Further analysis in this section centers on how the climate variability across the zones may or may not be a contributing factor to the malaria seasonality at the climate zone or national scale.

3.2. Climate Analysis

3.2.1. Interannual Temperature Variability

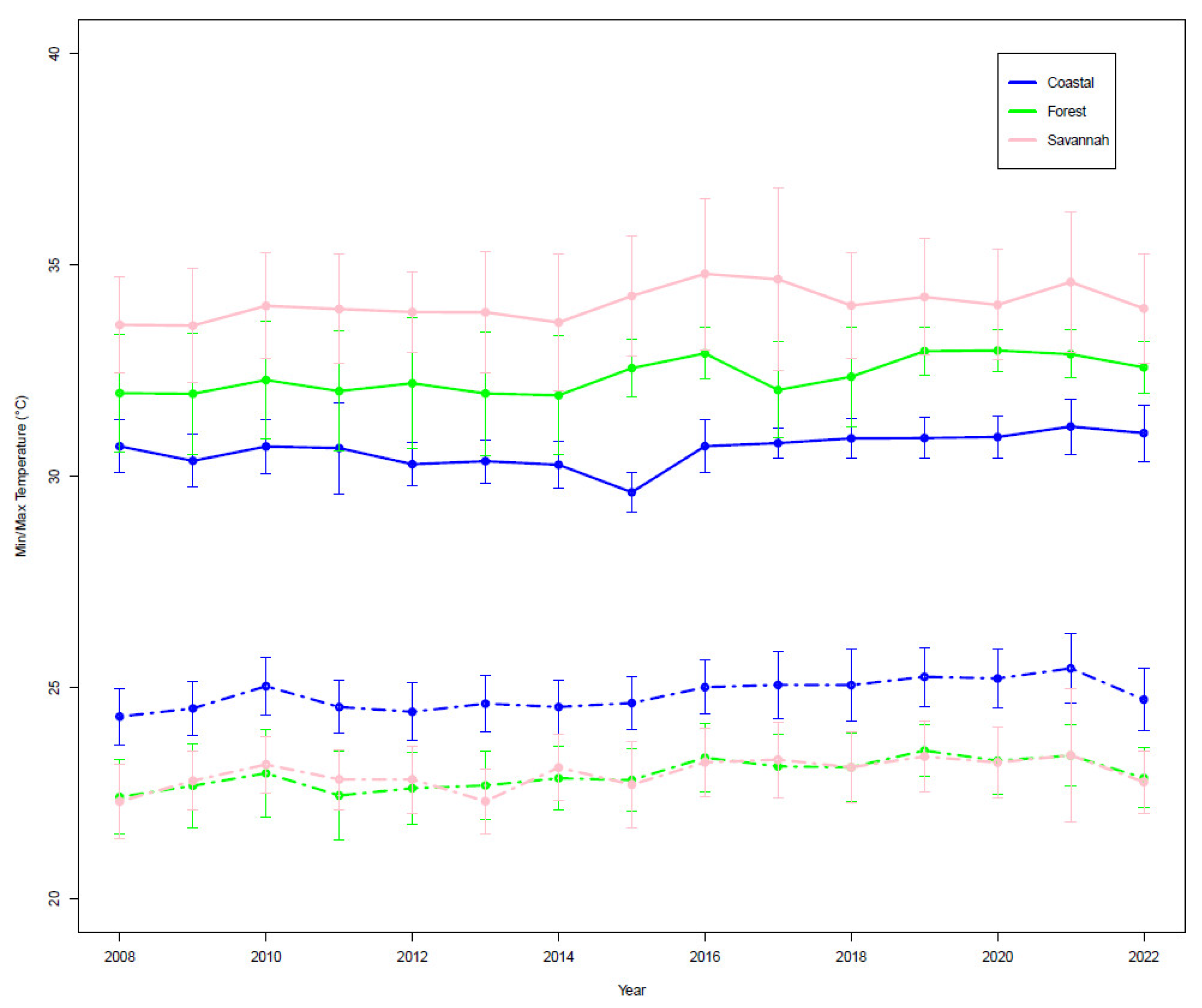

The annual mean maximum and mean minimum temperature variability of the climate zones are shown in

Figure 5 and give a broad indication of the environmental conditions that the malaria vectors are exposed to; the distribution of sub-annual measurements will be examined in

Section 3.2.2.

The annual data show a noticeable change in the maximum annual temperature from 2008–2013 and 2014–2022 for the forest and savannah climatic zones. The savannah climatic zone records temperatures above 34°C from 2014/15 to 2017/18, which was highlighted in

Section 1.2.1 as temperature values outside the optimum range of 17°C–33°C. Accordingly, this may have influenced vector activity and malaria transmission in the zone because temperatures above 34°C affects survival of the malaria vectors, reducing population of adult mosquitoes significantly [

25]. The forest climatic zone shows temperatures above 32.5°C in the years 2015 and 2016, falling back below 32.5°C in 2017 and recording slight increase for the rest of the years under study. The coastal zone also follows a similar pattern of notable changes in temperature from 2014 but showing a drop to below 30°C between 2014 and 2015, then rising back above 30°C up to 2022.

Annual mean minimum temperatures fluctuate much less across the three climatic zones from 2008–2022 (

Figure 5). Together with a weak positive trend from 2012–2021 being the only notable feature, this means that coastal and forest climatic zones record annual mean minimum and maximum temperature that are within the range of optimum temperatures across all years while savannah saw annual mean temperature recordings inconducive for malaria vector activity.

An important consideration is the fact that, although the annual mean minimum and maximum temperatures of the two climatic zones may have been within the optimum range for malaria transmission, daily-to-seasonal fluctuations in temperature play a more important role in malaria transmission. The reason being that the spatiotemporal malaria zone range is influenced by varying thresholds of temperature on the timescale of the lifecycle of the vector, which is much shorter than a year. Therefore, given that malaria cases peak at different times of year in the different climatic zones, we need to examine the annual cycle to further understand how the interannual trends are affecting the annual cycle over time and the impact on malaria case rates.

3.2.2. Annual Cycle of Temperature

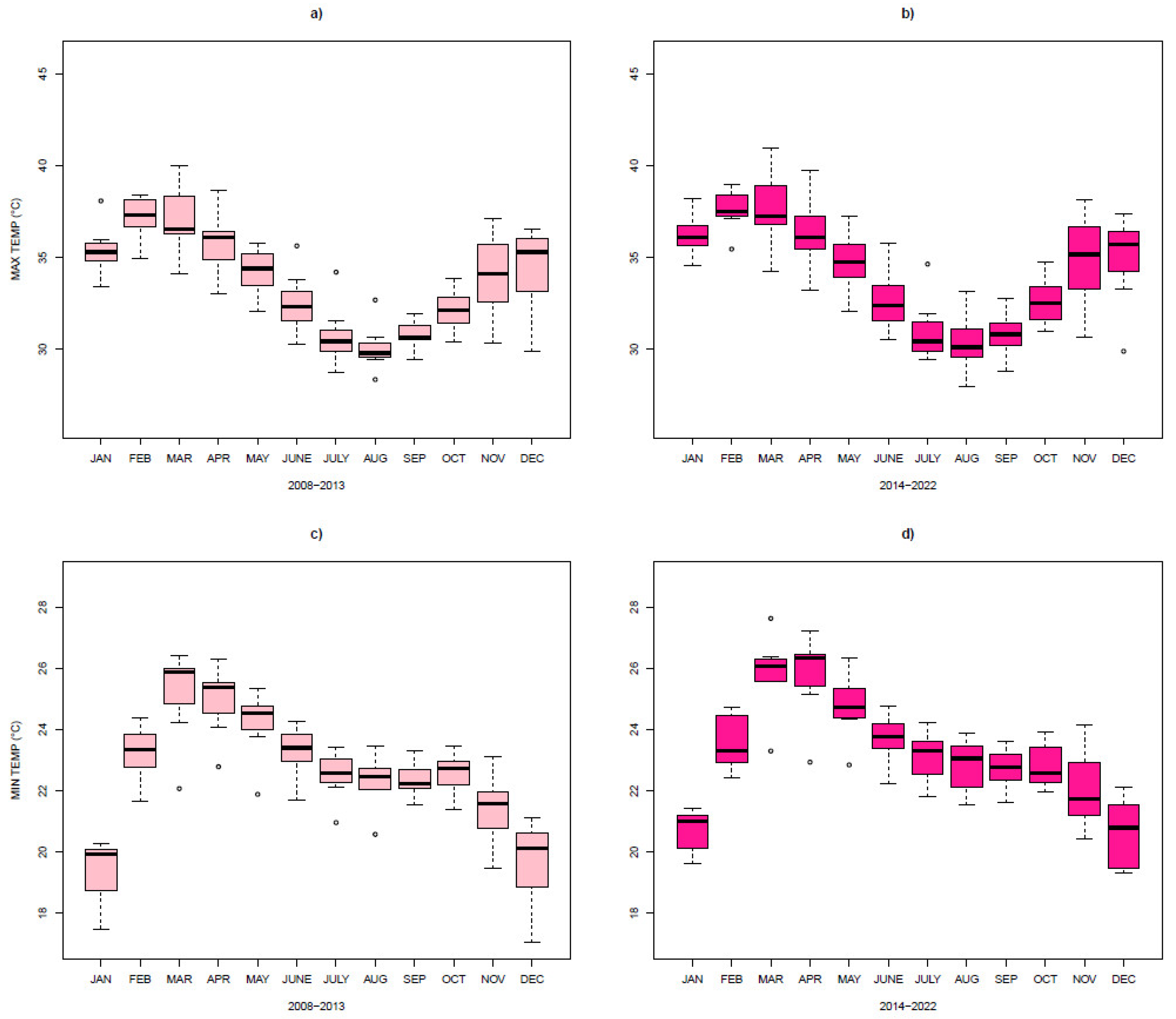

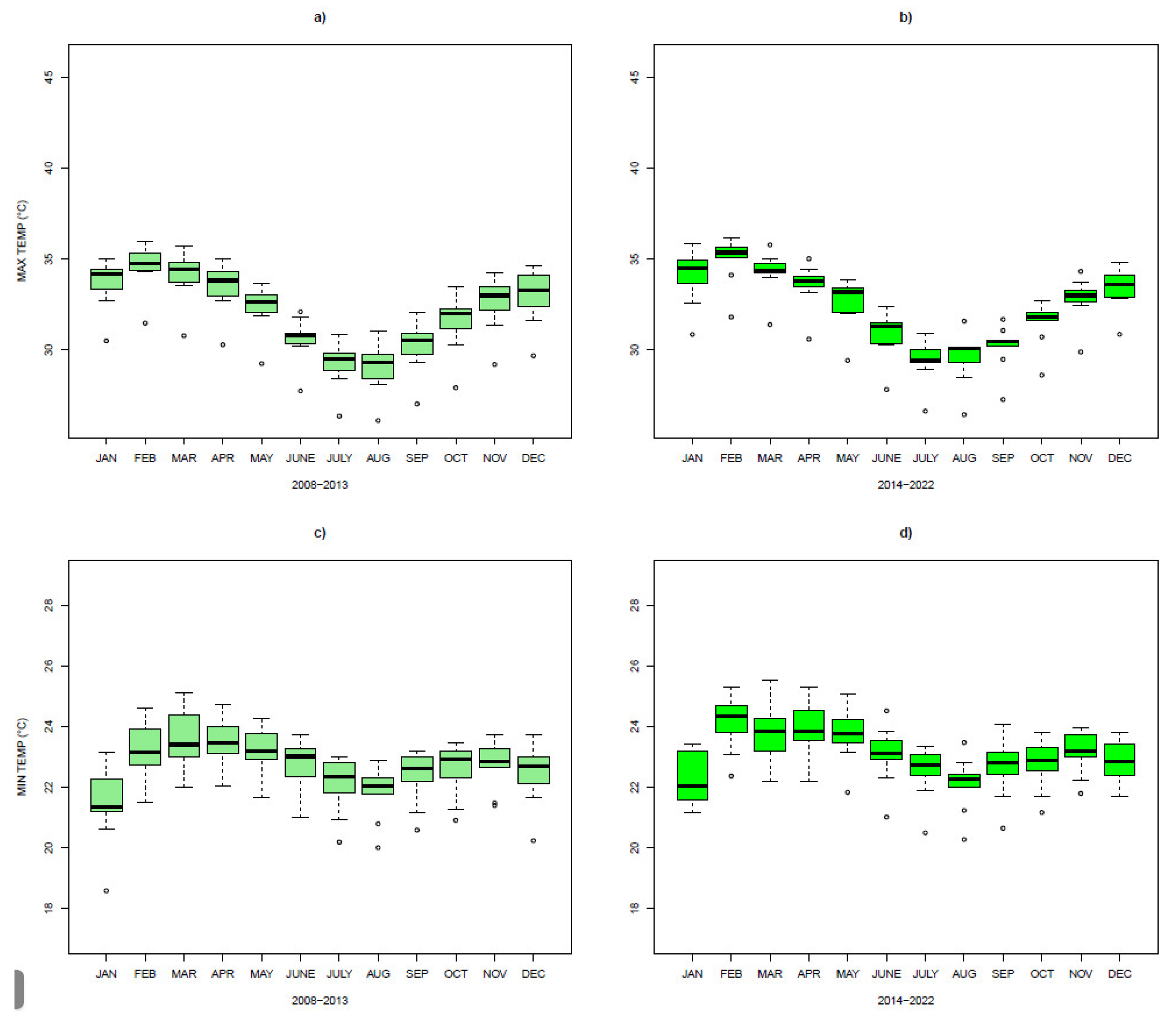

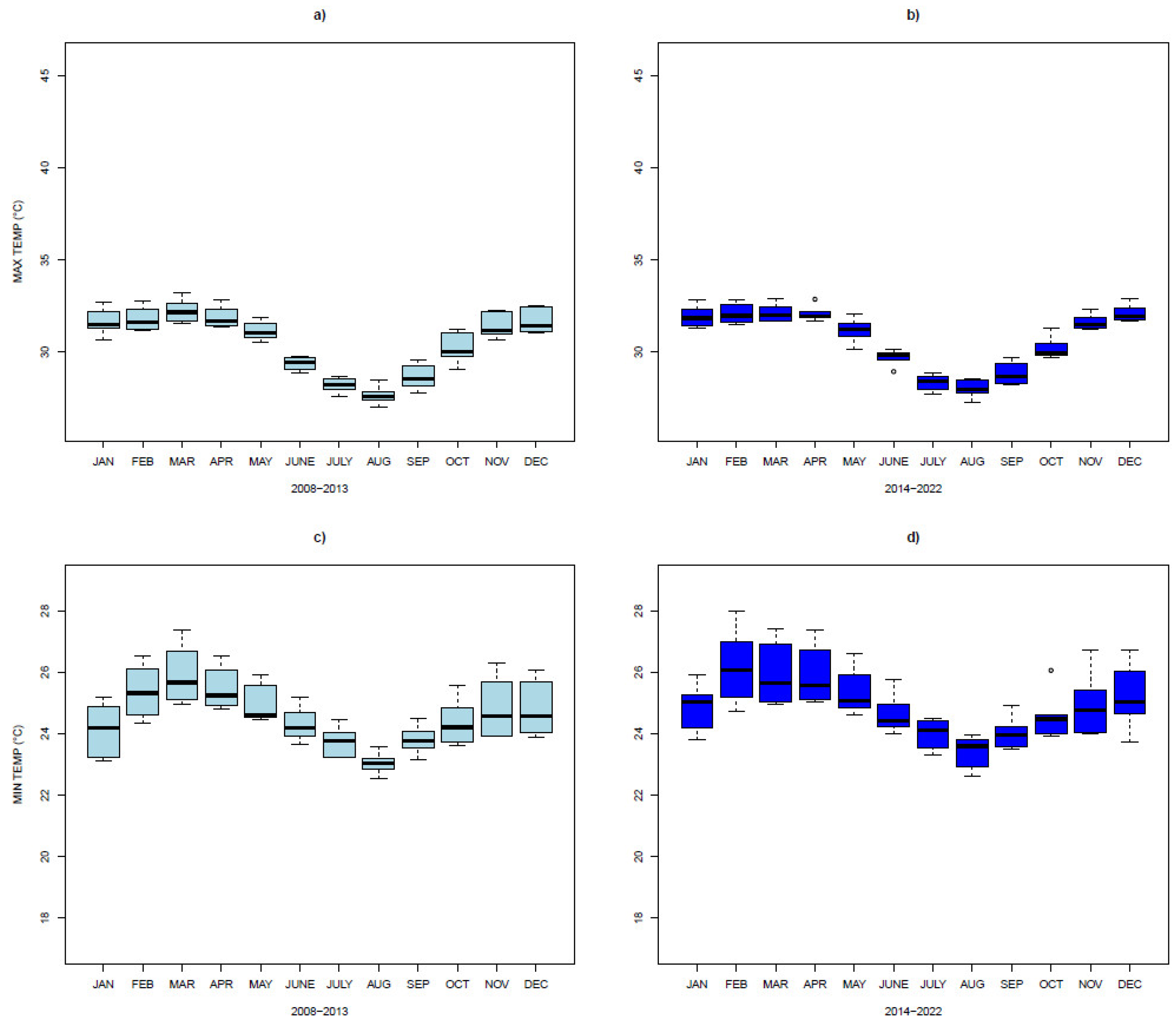

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 show the annual cycle of maximum and minimum temperatures for the three climatic zones: savannah, forest and coastal, respectively. The data are divided into two parts – 2008–2013 and 2014–2022 – to enable a more thorough investigation into the change in annual temperatures that appeared to occur in 2014 that was identified in

Section 3.2.1. This change was also coincident with the steep decline in malaria cases in Ghana so the discussion here will also consider the temperature regime in the context of optimum environmental conditions for malaria transmission.

The savannah climatic zone (

Figure 6), and the forest climatic zone (

Figure 7) show that the mean monthly maximum temperature was higher from November to May while coastal climatic zone (

Figure 8) presents an optimum temperature all year that is conducive for the survival of the malaria vector with the observed temperature range of 23–33°C with a much less pronounced peak period between November to April.

As discussed in

Section 1.1, the northern part of the country is noted to record high rates of malaria cases from July to November. For the south, the peak of the malaria season is from October to November with fewer cases recorded from May to June. Comparing these patterns with the climate variability seen in

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8, the savannah climate zone shows median monthly maximum temperatures within optimum ranges from June to October and median monthly maximum temperatures that exceeds the optimum threshold of 34°C from November to May. Median monthly minimum temperature recorded at the savannah climatic zone in December and January are between 19–20°C, which is lower than the usual range of temperature that is favourable for the malaria vector. These findings are consistent with a peak malaria period in July to November: this period corresponds to the months where the optimum minimum to maximum temperature ranges for the malaria vector are recorded. That said, and as shown in

Figure 6b,d, there has been an increase in median December minimum temperature in the savannah zone in the order of 0.5–1°C that could be responsible for slowing in the decline of malaria cases after 2014 (

Figure 4a) and/or, if this pattern persists, an extension in the malaria season potentially leading to an increase in cases.

The annual cycle of maximum and minimum temperatures in both the forest (

Figure 7) and coastal (

Figure 8) climatic zones demonstrate important similarities and differences to the savannah climatic zone.

The forest climatic zone regularly shows maximum temperatures during January to March above the 34°C upper threshold of the optimum temperatures for vector activity.

Figure 7c shows evidence that maximum temperatures in January and February increased after 2014 in the forest zone (increase in the median in the order of 1°C), which may have further constrained the period of optimum conditions for the vectors and contributed to the steep decline in malaria cases from 2014 onwards. June to October, on the other hand, records favourable temperature ranges for vector activity, typically between 21 and 33°C. Beyond this period, the maximum temperature in November (

Figure 7a,c) shows a reduction to below 34°C after 2014, which may have contributed to the slowing of the decline in cases after that point (

Figure 4b). The is also some evidence of a lagged relationship between temperature on malaria: the start of the malaria season in the southern and middle belt of Ghana begins in May, one month after the median of the maximum temperature distribution drops beneath 34°C in April.

In the coastal climatic zone, the minimum to maximum temperature ranges is within the optimum malaria vector range for the whole year. Maximum temperature recording is approximately 3–4°C higher in November to May as compared to June to October. Minimum temperatures in the coastal zone show a much less pronounced increase from August to December when compared to maximum temperatures but there is a steeper increase from January to March. Whilst the temperature ranges are conducive to malaria transmission all year round, other conditions, such as precipitation also needs to be considered.

3.2.3. Interannual Variability and Annual Cycle of Precipitation and relative Humidity

This section examines the variability of rainfall and humidity in Ghana by examining the annual changes from 2008 to 2022 and by examining the annual cycle. We will also examine how these variables may influence malaria transmission.

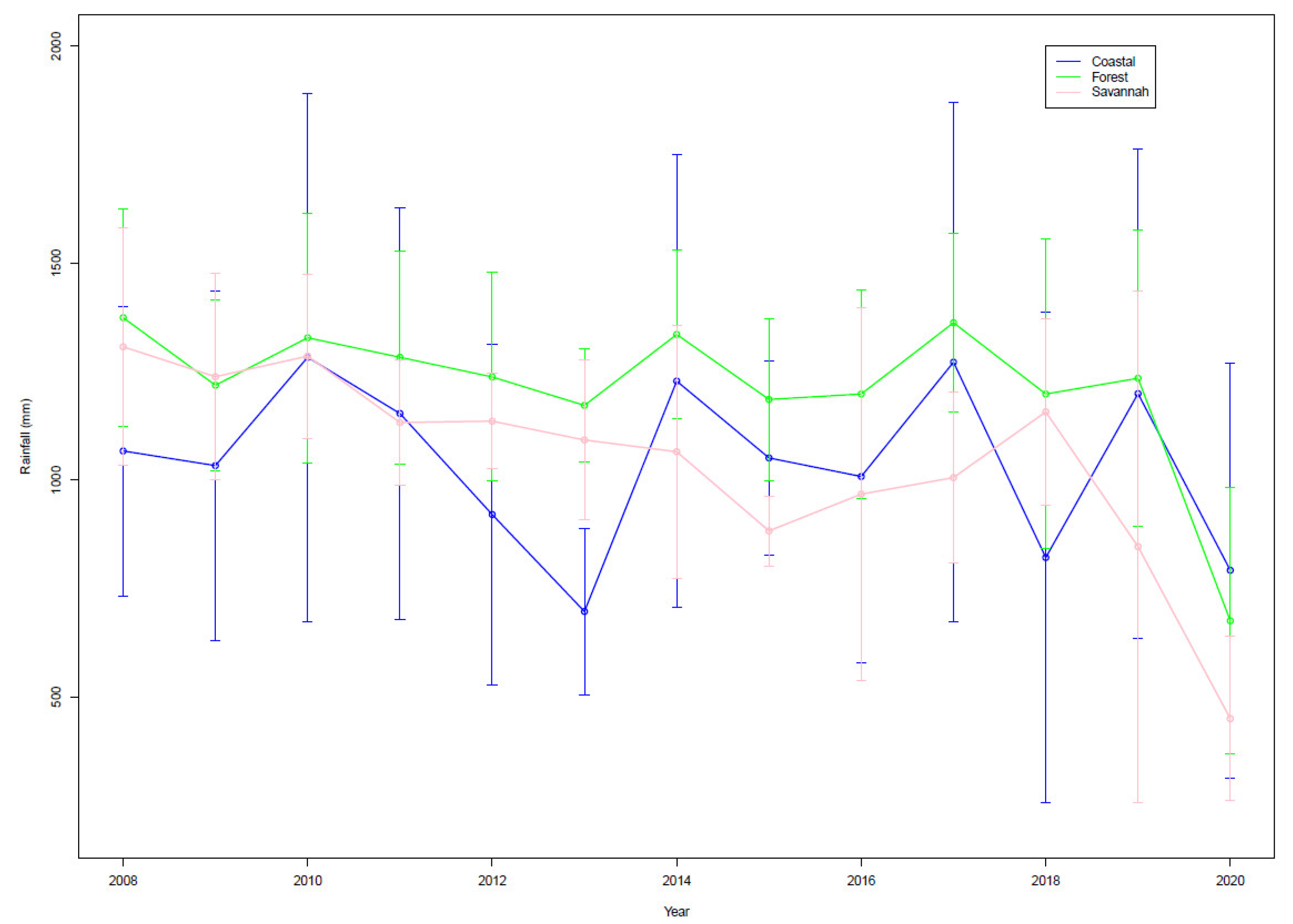

The interannual variability of rainfall by climate zones is shown in

Figure 9. It has been reported that, in Sub Saharan Africa regions, minimum monthly rainfall volume of 80 mm is needed for malaria transmission with a maximum monthly rainfall threshold of 400–600 mm as above that may cause flooding of mosquito breeding grounds resulting in vector death at the aquatic stage of development [

36]. This study found that the rainfall variability in Ghana maintains a viable range that supports malaria transmission for the most years across the three climatic zones.

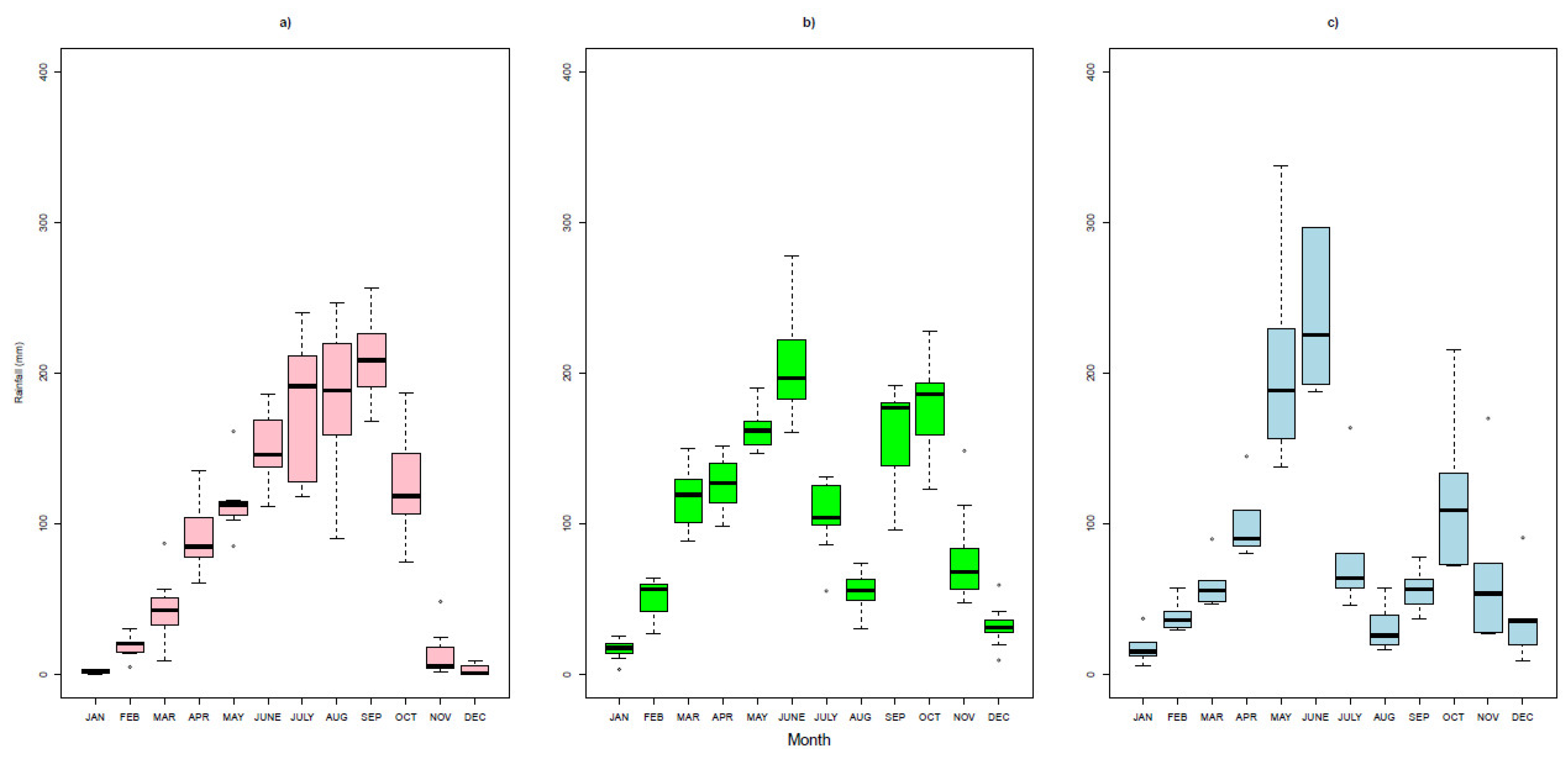

Figure 10 shows that the savannah zone receives very low rainfall in November to January and moderate to high rainfall volume from April to September. These observations are consistent with a malaria season that begins in July and ends in November. The forest and coastal zones demonstrate broadly bi-modal patterns of rainfall with peaks in June and October with moderate to high rainfall almost consistently from March/April to October. December, January, and February record rainfall below 80 mm across all climate zones. Similarly, these observations are consistent with a malaria season that begins in May and ends in November. Elsewhere, a low correlation between rainfall and malaria has been identified [

7], however lagged correlations for up to 4 months can demonstrate a link between these two variables, which appears to fit with initial observations of the data presented here.

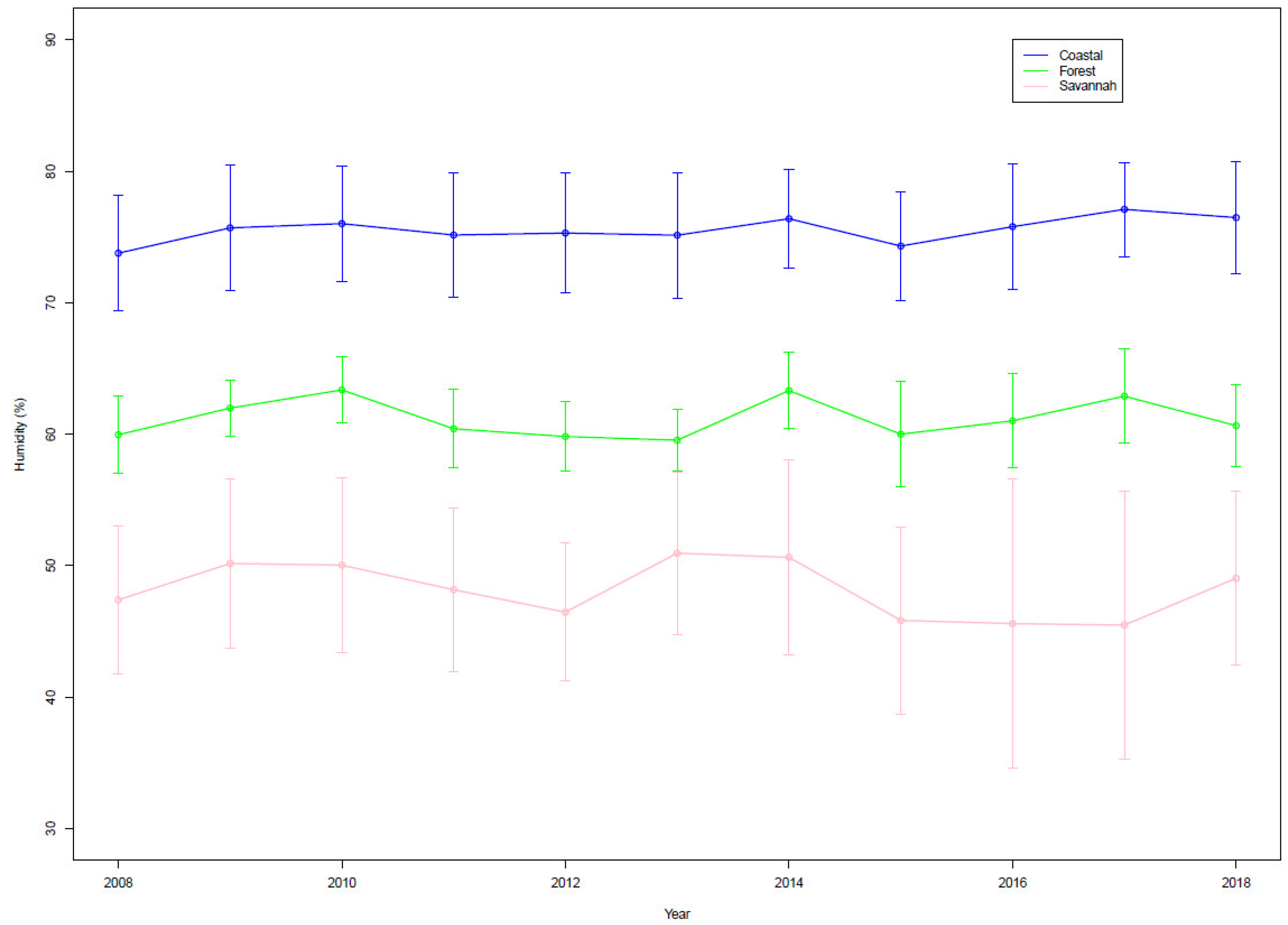

For relative humidity (RH),

Figure 11 shows that the savannah climatic zone recorded values between 45–51% for 2008–2018 (data were not available after 2018), the forest climatic zone between 59–64%, and the coastal zone between 73–77% i.e., a south-to-north negative gradient as the zones move further from the coast. Given the optimum range of RH is 55–80% [

25], these data show that the forest and coastal climate zones present an interannual RH variability that remains suitable for vector growth and malaria transmission in all years. The savannah climatic zone, however, fluctuates below the optimum range in certain years.

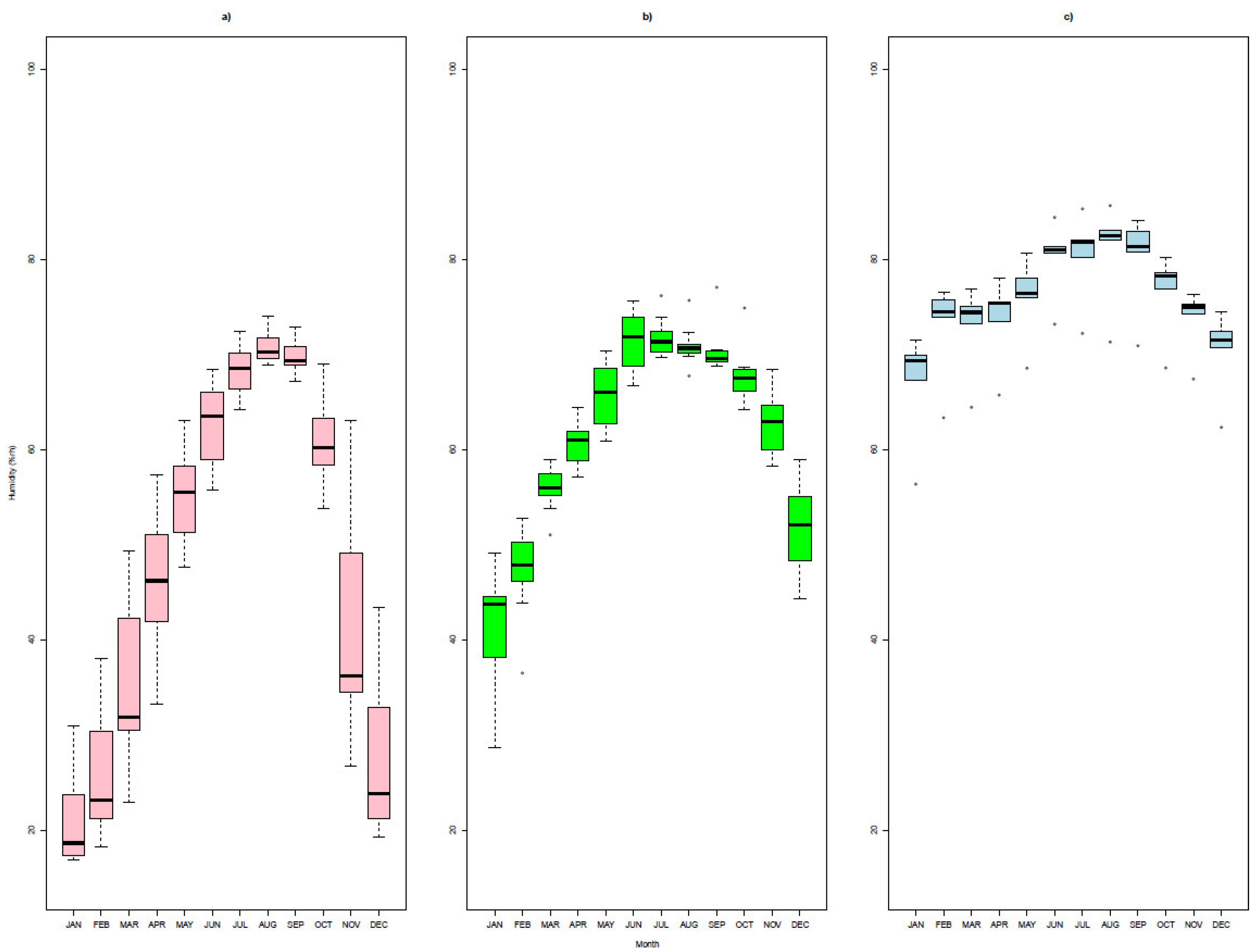

The within-year RH variability (

Figure 12) is more revealing of the most important relative humidity variability: the coastal zone has RH of 55–80% in all months apart from June to September when it is over 80%; the forest zone has RH of 55–80% in all months apart from December to March when it is below 55%; and for the savannah zone, the median RH is only within 55–80% range for May to October.

3.2.4. Summary of the Climate Analysis

Table 3 summarises the key periods when the climate variables are conducive to malaria transmission. This provides a qualitative perspective on the climate-malaria relationship that will be explored statistically in the next section.

3.3. Correlation of Malaria and Climate Variables

Further to identifying the periods where different elements of the climate regime are favorable to malaria transmission, we can apply simple inferential statistics tools to identify patterns of co-variability between the variables. Therefore,

Table 4 shows the results of a Pearson’s correlation analysis between malaria incidence rate and climate variables at the national and climate zone scale. At the national level, temperature has a moderate, negative correlation with malaria cases, where an increase in one variable broadly coincides with a decrease in the another. Rainfall is positively correlated but the relationship is also only moderate. The only statistically significant relationships are between malaria cases and mean and maximum temperature.

For the climate zones,

Table 4 also shows the relationship of malaria and climate variables at those spatial scales. There is a negative association with temperature in all climate zones, indicating an increase in temperature is be associated with a decline in malaria cases. The relationship is strongest at the coastal zone with a correlation coefficient of around -0.6 (p=0.02) for mean temperatures, -0.51 (p=0.05) for maximum temperatures and -0.59 (p=0.02) for minimum temperatures.

Rainfall volume at the climatic zone has a weak positive association with malaria incidence rate and humidity shows a weaker positive correlation with malaria cases also across all climate zones.

These simple correlation analyses are valuable in identifying where there is likely to be a linear relationship between variables and that is most strongly associated with temperature variability and change. The results are broadly in line with the more qualitative discussion around the relationships from

Section 3.2 i.e., that temperature increases occur alongside case rate declines. Where there are more complicated relationships, for example with precipitation and humidity, we are developing more sophisticated modelling approaches, including Bayesian modelling approaches (e.g., [

37,

38]), where multivariate and nonlinear relationships can be investigated in more depth alongside the inclusion of metrics of policy interventions.

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

4. Conclusions

This study provides the background understanding of the malaria-climate relationship in Ghana using climatic zone demarcations. Using data spanning from 2008–2022 for malaria, temperature, and rainfall variables, and 2008–2018 for humidity, the inter- and intra-annual patterns and trends were identified for malaria case rates, temperature, rainfall, and humidity data at the national and climate zone level. The suitability of the climate conditions for vector survival and growth was assessed to understand how climate may contribute to malaria incidence in Ghana.

We show that the coastal climatic zone has a year-round temperature suitability that supports vector growth and transmission and has the highest correlation coefficients between temperature and malaria case rates. Despite this, the coastal zone has the lowest malaria case rates of the three climatic zones, perhaps pointing to a further factor suppressing malaria cases, such as greater impact of social interventions in the major urban centers e.g., Accra.

Overall, analysis of malaria incidence rate per 1000 population shows a sharp decline from 2014, and further steady decline of cases till 2022, following a sharp rise from 2008 to 2013. This led to further investigation into the annual cycle of temperature across the climate zones from 2008–2013 and 2014–2022 to identify any changes that can be related to the malaria situation. This revealed there were indeed some significant changes in the climate variables between these two periods, especially at the savannah region. The forest and coastal regions also record temperature changes and variations conducive for vector activity and malaria transmission but maintains optimum ranges for vector activity all through 2008–2022.

The important months in the transmission cycle were identified from the literature, which is at its peak in June to October across all climatic zones. These months record optimum temperatures for the malaria vector and were further identified to record optimum ranges of precipitation and humidity for malaria transmission. When the annual cycle of the two periods before and after 2014 was compared, a sharp rise in malaria cases is observed (2008–2013), followed by a sharp, and then steady, fall in malaria cases (2014–2022). It was also observed that November to May, which seasonally records climate variability out of the optimum range in the savannah climatic zone, recorded an even more unfavorable temperature condition from 2014–2022, with a notable increase in temperature within the other two climatic zones. This underpins climate changes occurring within the country which may result in the suppression of cases in already low-risk areas, as well as a more notable reduction of cases in previously high-risk areas.

This study will be followed by modelling studies to understand the potentially non-linear and multivariate relationship that exists between malaria cases and climate variables in Ghana. The results presented here represent a background to understanding the possible influence of Ghana’s climate variability on Malaria, which is known to be a climate sensitive disease. It is also useful for planning climate proofing malaria control programs in Ghana. Understanding the malaria-climate dynamic through climatic zoning will inform the implementation of seasonal malaria chemoprevention, and where and when in the year to send adequate prophylaxis, adequate treated insecticide net, vector spraying and enforce public health education for malaria prevention considering climate favorability.

Further research should be undertaken considering how the seasonality of temperature, precipitation humidity as well as windspeed, sunshine hours and diurnal temperature range, alongside metrics of policy interventions, to understand how covariation of these climatic variables interplay in impacting malaria transmission. Furthermore, more sophisticated statistical modelling tools should be applied to understand and predict the future changes to the disease with the impact of short- to medium-term climate changes in the future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.R. and S.S.; methodology, A.R. and S.S.; software, E.A.; validation, E.A. and A.R.; formal analysis, E.A.; investigation, E.A.; resources, A.R. and S.S.; data curation, E.A.; writing—original draft preparation, E.A. and A.R.; writing—review and editing, E.A., S.S, and A.R.; visualization, E.A.; supervision, A.R. and S.S.; project administration, A.R. and S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GMet |

Ghana Meteorological Agency |

| RH |

Relative Humidity |

| WHO |

World Health Organisation |

References

- Badmos, A.O.; Alaran, A.J.; Adebisi, Y.A.; Bouaddi, O.; Onibon, Z.; Dada, A.; Lin, X.; Lucero-Prisno, D.E. What sub-Saharan African countries can learn from malaria elimination in China. Tropical Medicine and Health 2021, 49, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization: World malaria report 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/global-malaria-programme (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Ejigu, B.A.; Wencheko, E. Spatial Prevalence and Determinants of Malaria among under-five Children in Ghana. MedRxiv 2021. 2021.03.12.21253436. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. President’s Malaria Initiative Ghana Malaria Operational Plan 2022. Available online: www.pmi.gov (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Cissé, G.; McLeman, R.; Adams, H.; Aldunce, P.; Bowen, K.; Campbell-Lendrum, D.; Clayton, S.; Ebi, K.L.; Hess, J.; Huang, C.; Liu, Q.; McGregor, G.; Semenza, J.; Tirado, M.C. Health, Wellbeing, and the Changing Structure of Communities. In Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D.C., Tignor, M., Poloczanska, E.S., Mintenbeck, K., Alegría, A., Craig, M., Langsdorf, S., Löschke, S., Möller, V., Okem, A., Rama, B., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA; pp. 1041–1170.

- Klepac, P.; Hsieh, J.L.; Ducker, C.L.; Assoum, M.; Booth, M.; Byrne, I.; Dodson, S.; et al. Climate change, malaria and neglected tropical diseases: a scoping review. Transactions of The Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 2024, 118, 561–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klutse, N.A.B.; Aboagye-Antwi, F.; Owusu, K. .; Ntiamoa-Baidu, Y. Assessment of Patterns of Climate Variables and Malaria Cases in Two Ecological Zones of Ghana. Open Journal of Ecology 2014, 4, 764–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asare, E.O.; Amekudzi, L.K. Assessing Climate Driven Malaria Variability in Ghana Using a Regional Scale Dynamical Model. Climate 2017, 5, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ankamah, S.; Nokoe, K.S.; Iddrisu, W.A. Modelling Trends of Climatic Variability and Malaria in Ghana Using Vector Autoregression. Malaria Research and Treatment 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessah, E.; Amponsah, W.; Owusu Ansah, S.; Afrifa, A.; Yahaya, B. , Senyo Wemegah, C.; Tanu, M.; Amekudzi, L.K.; Agyei Agyare, W. Climatic zoning of Ghana using selected meteorological variables for the period 1976-2018. Meteorological Applications, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Turell, M.J. Effect of environmental temperature on the vector competence of Aedes fowleri for rift valley fever virus. Research in Virology 1989, 140, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egbendewe-Mondzozo, A.; Musumba, M.; Mccarl, B.A.; Wu, X. Climate Change and Vector-borne Diseases: An Economic Impact Analysis of Malaria in Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2000, 8, 913–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agusto, F.B.; Gumel, A.B.; Parham, P.E. Qualitative assessment of the role of temperature variations on malaria transmission dynamics. Journal of Biological Systems 2015, 23, 597–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, L.L.M.; Whitehead, S.A.; Thomas, M.B. (2003). Quantifying the effects of temperature on mosquito and parasite traits that determine the transmission potential of human malaria. PLOS Biology 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta, S. Burden of climate change on malaria mortality. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health 2018, 221, 782–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mordecai, E.A.; Paaijmans, K.P.; Johnson, L.R.; Balzer, C.; Ben-Horin, T.; Moor, E.; Mcnally, A.; Pawar, S.; Ryan, S.J.; Smith, T.C.; Lafferty, K.D. Optimal temperature for malaria transmission is dramatically lower than previously predicted. Ecology Letters 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paaijmans, K.P.; Read, A.F.; Thomas, M.B. Understanding the link between malaria risk and climate. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2009, 106, 13844–13849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oesterholt, M.J.A.M.; Bousema, J.T.; Mwerinde, O.K.; Harris, C.; Lushino, P.; Masokoto, A.; Mwerinde, H.; Mosha, F.W.; Drakeley, C.J. Spatial and temporal variation in malaria transmission in a low endemicity area in northern Tanzania. Malaria Journal 2006, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomson, M.C.; Doblas-Reyes, F.J.; Mason, S.J.; Hagedorn, R.; Connor, S.J.; Phindela, T.; Morse, A.P.; Palmer, T.N. Malaria early warnings based on seasonal climate forecasts from multi-model ensembles. Nature 2006, 439, 576–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpalu, W.; Codjoe, S.N.A. Economic analysis of climate variability impact on malaria prevalence: The case of Ghana. Sustainability 2013, 5, 4362–4378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, S.I.; Rogers, D.J.; Randolph, S.E.; Stern, D.I.; Cox, J.; Shanks, D.; Snow, R. (2002). Hot topic or hot air? Climate change and malaria resurgence in East African highlands. Trends Parasitol. 2002, 18, 530–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dev, V.; Dash, A.P. Rainfall and malaria transmission in north-eastern India. Annals of Tropical Medicine and Parasitology 2007, 101, 457–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Hoek, W.; Konradsen, F.; Perera, D.; Amerasinghe, P.H.; Amerasinghe, F.P. Correlation between rainfall and malaria in the dry zone of Sri Lanka. Annals of Tropical Medicine & Parasitology 1997, 91, 945–949. [Google Scholar]

- Nsereko, G.; Kadobera, D.; Okethwangu, D.; Nguna, J.; Rutazaana, D.; Kyabayinze, D.J.; Opigo, J.; Ario, A.R. (2020). Malaria outbreak facilitated by appearance of vector-breeding sites after heavy rainfall and inadequate preventive measures: Nwoya District, Northern Uganda, February-May 2018. Journal of Environmental and Public Health 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nissan, H.; Ukawuba, I.; Thomson, M. Climate-proofing a malaria eradication strategy. Malaria Journal, 2021; 20. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya, S.; Sharma, C.; Dhiman, R.C.; Mitra, A.P. (2006) Climate change and malaria in India. Current Science 2006, 90, 369–375. [Google Scholar]

- Haque, U.; Glass, G.E.; Bomblies, A.; Hashizume, M.; Mitra, D.; Haque, R.; Yamamoto, T. The role of climate variability in the spread of malaria in Bangladeshi highlands. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e14341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, L.; Bi, P.; Cazelles, B.; Zhou, S.; Huang, C.; Yang, J. One-year delayed effect of fog on malaria transmission: A time-series analysis in the rain forest area of Mengla County, south-west China. Malaria Journal, 2008; 7. [Google Scholar]

- FAO: Fertilizer use by crop in Ghana. Rome (2005): Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Available online: https://www.fao.org/4/a0013e/a0013e00.htm (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Abass, K. A regional geography of Ghana for senior high schools and undergraduates; Pictis Publications: Accra, Ghana, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Asante, F.A.; Amuakwa-Mensah, F. Climate change and variability in Ghana: Stocktaking. Climate 2015, 3, 78–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghana Statistical Service: 2021 population & housing census. Available online: https://statsghana.gov.gh/gssmain/fileUpload/pressrelease/Population_projection_280624_final_ffa2[1][2]_with_links[_final_website.pdf (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- WHO: Ghana Malaria incidence (per 1000 population at risk) Available online:. Available online: https://data.who.int/indicators/i/B868307/442CEA8?m49=288 (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- U.S. President’s Malaria Initiative Ghana Malaria Operational Plan 2020. Available online: www.pmi.gov (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Country Coordinating Mechanism (CCM) Ghana: Malaria in Ghana: 2018-2020 Principal Recipients. Available online: https://www.ccmghana.net/index.php/principal-recipients/2018-2020/malaria (accessed on 24 May 2022).

- Yamba, E.I.; Fink, A.H.; Badu, K.; Asare, E.O.; Tompkins, A.M.; Amekudzi, L.K. Climate Drivers of Malaria Transmission Seasonality and Their Relative Importance in Sub-Saharan Africa. GeoHealth 2023, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitolo, C.; Scutari, M.; Ghalaieny, M.; Tucker, A.; Russell, A. Modeling Air Pollution, Climate, and Health Data Using Bayesian Networks: A Case Study of the English Regions. Earth and Space Science 2018, 5, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harwood, H.; Hall, R.; Di Capua, G.; Russell, A.; Tucker, A. Using Bayesian Networks to investigate the influence of subseasonal Arctic variability on midlatitude North Atlantic circulation. Journal of Climate 2021, 34, 2319–2335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Map of Ghana showing: the 16 administrative regions demarcated by the thick black borders and labelled in black; and the 261 districts demarcated by the thin black borders (no labels). The map is divided into the three climatic zones by colors: blue areas represent the coastal climatic zone; green areas represent the forest climatic zone; and pink areas represent the savannah climatic zone. The 22 GMet synoptic stations are labelled in blue.

Figure 1.

Map of Ghana showing: the 16 administrative regions demarcated by the thick black borders and labelled in black; and the 261 districts demarcated by the thin black borders (no labels). The map is divided into the three climatic zones by colors: blue areas represent the coastal climatic zone; green areas represent the forest climatic zone; and pink areas represent the savannah climatic zone. The 22 GMet synoptic stations are labelled in blue.

Figure 2.

Annual malaria cases (red line and axis) and incidence rate (black line and axis) from 2008 to 2022 in Ghana.

Figure 2.

Annual malaria cases (red line and axis) and incidence rate (black line and axis) from 2008 to 2022 in Ghana.

Figure 3.

Malaria incidence rate (cases per 1000 of population) for each of the 16 administrative regions in Ghana for 2008–2022. The plots for the regions have been arranged as similarly as possible to represent how they are situated geographically in Ghana.

Figure 3.

Malaria incidence rate (cases per 1000 of population) for each of the 16 administrative regions in Ghana for 2008–2022. The plots for the regions have been arranged as similarly as possible to represent how they are situated geographically in Ghana.

Figure 4.

Malaria incidence rate (cases per 1000 of population) for the three climatic zones from 2008–2022: a) savannah; b) forest; and c) coastal.

Figure 4.

Malaria incidence rate (cases per 1000 of population) for the three climatic zones from 2008–2022: a) savannah; b) forest; and c) coastal.

Figure 5.

Annual mean maximum and mean minimum temperature of the climate zones for 2008–2022. The maximum temperature is represented by solid lines and the minimum temperature by dash lines. The vertical lines represent +/- 1 standard deviation. The savannah climatic zone is shown in pink, forest in green and coastal in blue.

Figure 5.

Annual mean maximum and mean minimum temperature of the climate zones for 2008–2022. The maximum temperature is represented by solid lines and the minimum temperature by dash lines. The vertical lines represent +/- 1 standard deviation. The savannah climatic zone is shown in pink, forest in green and coastal in blue.

Figure 6.

Boxplots of minimum and maximum temperatures for the savannah climatic zone: a) maximum temperatures for 2008–2013; b) maximum temperatures for 2014–2022; c) minimum temperatures for 2008–2013; and d) maximum temperatures from 2014–2022. The bold horizontal line shows the median, the box represents the interquartile range, the whiskers represent the range and circles show outliers i.e., greater (less) than the third (first) quartile plus (minus) 1.5 times the interquartile range.

Figure 6.

Boxplots of minimum and maximum temperatures for the savannah climatic zone: a) maximum temperatures for 2008–2013; b) maximum temperatures for 2014–2022; c) minimum temperatures for 2008–2013; and d) maximum temperatures from 2014–2022. The bold horizontal line shows the median, the box represents the interquartile range, the whiskers represent the range and circles show outliers i.e., greater (less) than the third (first) quartile plus (minus) 1.5 times the interquartile range.

Figure 7.

As for

Figure 6 but for the forest climate zone.

Figure 7.

As for

Figure 6 but for the forest climate zone.

Figure 8.

As for

Figure 6 but for the coastal climate zone.

Figure 8.

As for

Figure 6 but for the coastal climate zone.

Figure 9.

Annual average precipitation totals from the GMet stations for the climate zones for 2008–2022. The vertical lines represent +/- 1 standard deviation. The savannah climatic zone is shown in pink, forest in green and coastal in blue.

Figure 9.

Annual average precipitation totals from the GMet stations for the climate zones for 2008–2022. The vertical lines represent +/- 1 standard deviation. The savannah climatic zone is shown in pink, forest in green and coastal in blue.

Figure 10.

Boxplots of precipitation for the three climate zones for 2008–2022: a) savannah; b) forest; c) coastal.

Figure 10.

Boxplots of precipitation for the three climate zones for 2008–2022: a) savannah; b) forest; c) coastal.

Figure 11.

Annual average relative humidity from the GMet stations for the three climate zones (savannah in pink, forest in green, coastal in blue) for 2008–2022.

Figure 11.

Annual average relative humidity from the GMet stations for the three climate zones (savannah in pink, forest in green, coastal in blue) for 2008–2022.

Figure 12.

Boxplots of relative humidity variability from the GMet stations for the three climatic zones for 2008–2022: a) savannah in pink; b) forest in green; and c) coastal in blue.

Figure 12.

Boxplots of relative humidity variability from the GMet stations for the three climatic zones for 2008–2022: a) savannah in pink; b) forest in green; and c) coastal in blue.

Table 1.

Regions in Ghana with their Population and Population Density. Source: [

32].

Table 1.

Regions in Ghana with their Population and Population Density. Source: [

32].

| Region |

Population |

Population Density (km-2) |

| Ahafo |

564,668 |

108.6 |

| Ashanti |

5,440,463 |

222.7 |

| Bono |

1,208,649 |

108.8 |

| Bono East |

1,203,400 |

51.8 |

| Central |

2,859,821 |

291.0 |

| Eastern |

2,925,653 |

151.0 |

| Greater Accra |

5,455,692 |

1678.3 |

| North East |

658,946 |

72.6 |

| Northern |

2,310,939 |

87.1 |

| Oti |

747,248 |

67.5 |

| Savannah |

653,266 |

18.7 |

| Upper East |

1,301,226 |

49.0 |

| Upper West |

901,502 |

173.6 |

| Volta |

1,659,040 |

148.6 |

| Western |

2,060,585 |

148.6 |

| Western North |

880,921 |

87.4 |

| Total |

30,832,019 |

128.8 |

Table 2.

The 22 synoptic stations of GMet and their coordinates classified under the three climatic zones [

10].

Table 2.

The 22 synoptic stations of GMet and their coordinates classified under the three climatic zones [

10].

| Synoptic station (zone) |

Latitude |

Longitude |

| Tamale (savannah) |

9.42 |

-0.85 |

| Yendi (savannah) |

9.45 |

-0.02 |

| Bole (savannah) |

9.03 |

-2.48 |

| Navrongo (savannah) |

10.90 |

-1.10 |

| Wa (savannah) |

10.05 |

-2.50 |

| Kete Krachi (savannah) |

7.82 |

-0.03 |

| Kumasi (forest) |

6.72 |

-1.60 |

| Sunyani (forest) |

7.33 |

-2.33 |

| Wenchi (forest) |

7.75 |

-2.10 |

| Ho (forest) |

6.60 |

0.47 |

| Akatsi (forest) |

6.12 |

0.80 |

| Koforidua (forest) |

6.08 |

-0.25 |

| Akuse (forest) |

6.10 |

0.12 |

| Akim - Oda (forest) |

5.93 |

-0.98 |

| Abetifi (forest) |

5.60 |

-0.17 |

| Sefwi Bekwai (forest) |

6.20 |

-2.33 |

| Accra (coastal) |

5.60 |

-0.17 |

| Tema (coastal) |

5.62 |

0.00 |

| Ada (coastal) |

5.38 |

0.63 |

| Saltpond (coastal) |

5.20 |

-1.07 |

| Takoradi (coastal) |

4.88 |

-1.77 |

| Axim (coastal) |

4.87 |

-2.23 |

Table 3.

Overview of the climate conditions favourable for malaria transmission in the three climatic zones.

Table 3.

Overview of the climate conditions favourable for malaria transmission in the three climatic zones.

| |

Coastal |

Forest |

Savannah |

| Malaria season |

May-Nov |

May-Nov |

Jul-Nov |

| Temperature (interannual) |

Within 21–33°C optimum range for all years |

Within 21–33°C optimum range for all years |

Exceeds 34°C after 2014 (21–33°C optimum range) |

| Temperature (annual cycle) |

21–33°C all year |

21–33°C in Apr-Dec |

21–33°C in Jun-Nov |

| Precipitation (interannual) |

Within 690–1300 mm, optimum range for all years |

Within 670–1400 mm, optimum range for all years |

Within 450–1400 mm, optimum range for all years |

| Precipitation (annual cycle) |

Moderate to high Apr-Sept |

Moderate to high Mar-Oct |

Moderate to high Mar-Oct |

| RH (interannual) |

73–77% (within 55–80% optimum range) |

59–64% (within 55–80% optimum range) |

45–51% (outside 55–80% optimum range) |

| RH (annual cycle) |

55–80% in Oct-May |

55–80% in Apr-Nov |

55–80% in May-Oct |

Table 4.

Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) between annual malaria incidence rate and the collected climate variables for 2008-2022 (2008-2018 only for humidity). The p-value is shown in brackets after r and r is shown in bold where p<0.05.

Table 4.

Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) between annual malaria incidence rate and the collected climate variables for 2008-2022 (2008-2018 only for humidity). The p-value is shown in brackets after r and r is shown in bold where p<0.05.

| Climate variable |

r (national) |

r (savannah) |

r (forest) |

r (coastal) |

| Mean temp. |

-0.54 (0.04) |

-0.44 (0.10) |

-0.50 (0.06) |

-0.60 (0.02) |

| Max temp. |

-0.55 (0.03) |

-0.34 (0.22) |

-0.47 (0.07) |

-0.51 (0.05) |

| Min temp. |

-0.49 (0.07) |

-0.45 (0.09) |

-0.48 (0.07) |

-0.59 (0.02) |

| Rainfall |

-0.42 (0.11) |

0.47 (0.08) |

0.47 (0.08) |

0.32 (0.24) |

| Humidity |

0.02 (0.96) |

0.32 (0.34) |

-0.32 (0.33) |

-0.19 (0.60) |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).