Introduction

Peritoneal dialysis (PD) is a high-quality and cost-effective renal replacement therapy (RRT) that employs the peritoneum as a semi-permeable membrane, enabling selective diffusion of metabolic waste products into a peritoneal dialysis solution (PDS) instilled within the peritoneal cavity via a surgically implanted catheter (Roumeliotis et al., 2020). Through this mechanism, PD serves as a substitute for renal filtration, thereby extending the life expectancy of patients with renal failure.

Globally, PD accounts for 9% of all RRT (Bello et al., 2022). In Mexico PD is administered to 59% of patients with renal failure, and an annual cost of up to $120,00.00 MXN (Vasquez-Jimenez & Madero, 2020).

Despite its clinical benefits, the intrinsic components of PDS — such as low pH, high glucose concentrations, glucose degradation products (GDPs), and advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) — along with the patient’s uremic state, contribute with to inflammatory process that promote the development of the peritoneal fibrosis (Roumeliotis et al., 2020). This pathological remodeling progressively compromises the efficacy of PD resulting in functional failure of peritoneal membrane (Uiterwijk et al., 2020). Consequently, both chronic inflammation and the uremic milieu are the principal drivers of peritoneal membrane dysfunction. Addressing these mechanisms through nutritional strategies is essential to prolong the functional viability of PD and improve the quality of life of patients undergoing this therapy (Bello et al., 2022).

Arthrospira maxima is a cyanobacterium traditionally consumed as a dietary supplement due its bioactive properties (Lafarga et al., 2020; Memije-Lazaro et al., 2018). Through its C-phycocyanin (CPC) — one of its major bioactive components — A. maxima exhibits anti-inflammatory, anti-angiogenic (Jayanti et al., 2021), immunomodulatory, and anti-fibrotic effects (Blas-Valdivia et al., 2022; DiNicolantonio et al., 2021; C. Li et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2022; Mundo-Franco et al., 2024). However, its potential role in mitigating complications associated with peritoneal dialysis remains unexplored. Therefore, this study aims to evaluate the effectiveness of A. maxima on the development of peritoneal remodeling induced by an acute uremic peritoneal model.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Care and procedures were performed in accordance with the regulation set in NOM-062- ZOO-1999 (DOF, 1999), and were approved by the Institutional Animal Ethical Committee (CEI-ENCB) for the care and use of laboratory animals (ZOO-003-2024).

Twenty male Wistar rats weighing 300-350 g were allowed to acclimatize for two weeks before experiments. Animals were housed in individual cages in a standard animal facility with regulated temperature at 21 ± 2 °C, 40-60% of relativity humidity, a 12 h light-dark cycle (lights on at 08:00), and at libidum access to standard diet (RatChow 5001, LabDiet®, Richmond, USA.) and tap water.

Uremic Peritoneal Dialysis Model

Animals were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (35 mg/kg, IP) and bilateral nephrectomy — to induce uremic state — or sham surgery was performed as previously reported (Rojas-Franco et al., 2022). Briefly, blood samples were collected from caudal vein, and ventral laparotomy was conducted to expose both kidneys. Blood vessels and ureter were occluded, and the kidneys were removed. A sterilized peritoneal catheter was implanted into the peritoneal cavity and fixed to the abdominal wall using 4-0 silk suture. The catheter was tunneled subcutaneously until the interscapular back. Afterwards, 30 mL/kg of 1.5% glucose pre-warmed (37° C) dialysis solution (Dianeal, Baxter, Deerfield, USA) was instilled via the catheter and drained after 10 min to corroborate the permeability of catheter and then it was secured with a silicon tip (Fujii et al., 2009). Finally, animals were administered during all the experiment with of enrofloxacin (10 mg/kg/d, SC) and tramadol (10 mg/kg/d, PO) to prevent infections and avoid pain.

Experimental design

Animals were divided into four groups (n=5): (1) Sham (Sham + standard diet); (2) enriched diet (Sham +

A. maxima-enriched diet); (3) UPD (Uremic peritoneal dialysis + standard diet); and (4) UPD + Enriched diet.

A. maxima-enriched diet was prepared by mixing powdered standard diet with

A. maxima (Spiral Spring, CDMX, Mexico) in a ratio of 80:20. Diets were provided to animals following surgery and its composition are shown in

Table 1.

The PD sessions started 24 h later surgery and lasted for five days. A blood sample from caudal vein was collected and PD was performed instilling 30 mL/kg of pre-warmed 1.5% glucose dialysis solution through the catheter and drained after 2 hours. Another blood sample from caudal vein was collected after PD session (Fujii et al., 2009). PD session was performed daily, as well as feed intake and body weight measure. Energy intake was calculated according to energy supply of diets (

Table 1) and the data are presented as normalized energy intake in kJ per 100 g of body weight.

At the end of the experiment, animals were euthanized by sodium pentobarbital overdose (150 mg/kg, IP). Briefly 10 mL of sterile isotonic saline solution (ISS) was injected into the peritoneal cavity and held for 2 minutes with a soft massage. Wash was recovered in 1 mL of new ISS and immediately centrifugated at 600 × g for 10 min. Afterwards, intracardiac blood was collected and five liver imprints of each animal were obtained using glass slides coated with 6% (p/v) gelatin. A 2 × 2 cm of the abdominal wall close to the end of catheter was dissected and frizzed at -80° C to molecular evaluation. Mesenteric, retroperitoneal and gonadal adipose tissue were dissected and weighed. Results of adipose tissue are presented as g of adipose tissue per 100 g of body weight.

Biochemical Analysis

Serum was obtained by centrifugation at 3500 × g for 5 min. Assays were conducted using a 96 well microplate adjusting the final volume to 100 µL, following the proportion of reactive:sample according to kits from Spinreact® (Girona, Spain), Randox (Crumlin, Irland) or Wiener Lab (Rosario, Argentin). The absorbances were measured using a spectrophotometer MultiSkan Go (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, USA.).

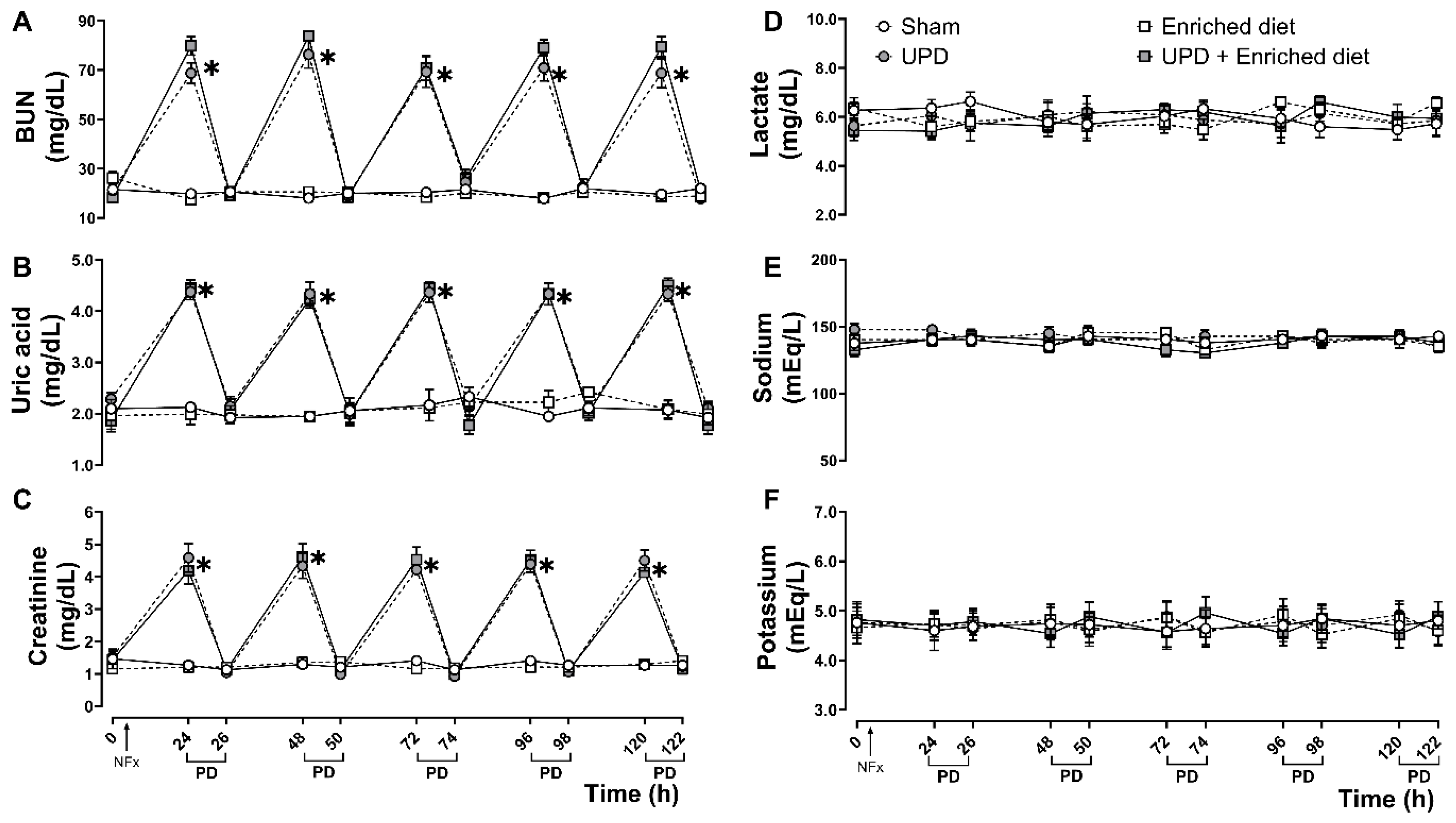

Blood urea nitrogen (BUN, 41042), uric acid (41002), creatinine (CR524), lactate (LC2389), sodium (1001385) and potassium (PT1600) were measured before and after dialysis sessions, while calcium (1152002), inorganic phosphorus (1382321), albumin (1001020), total proteins (PT1630A), triglycerides (TR1697) and cholesterol (CH200) were measured only at the end of the experiment.

Microscopic Evaluation of Peritoneal Alterations

Cellular composition in peritoneum was analyzed in peritoneal wash by discarding the supernatant and resuspending the pellet in 1 mL of ISS and vortexed for 30 sec. Afterwards, suspension was mingled with Türk reagent (1:1) and total cells were quantified in a hematocytometer, and differential cellular count was made using Wright stain. The results are expressed as cell type x106 per mL (Zareie et al., 2005). Liver imprints were stained with Wright’s and mesothelial cells as well as alterations were counted in 20 fields by a blind observer to the experiment (Hekking et al., 2001). Results are presented as mesothelial cells x102 per mm2 and percentage of activated mesothelial cells in UPD groups.

Molecular Evaluation of Peritoneal Alterations

iNOS (sc-7271), collagen α-III (sc-271249), and eNOS (sc-376751) expression levels were determined by Western Blot, following the protocol previously reported (Rojas-Franco et al., 2021). Briefly, abdominal wall tissue homogenized in 1.5 mL of phosphate buffer (10 mM, pH 7.4), and total protein concentration was quantified using Bradford. Primary antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX) were used at a 1:1000 dilution, and β-actin (sc-47778) served as loading control for constitutive protein expression. Band optical density (OD) was analyzed using ImageJ image analysis software and results are expressed as OD protein/OD β-actin ratio normalized.

Statistical Analysis

GraphPad Prism (v8.0.1, GraphPad Software, MA, USA) was used for statistics. Activated mesothelial cells are expressed as median ± interquartile range (IQR) and were analyzed by Mann-Whitney U-test. The rest of the results are expressed as mean ± standard error of mean (SEM). Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed using procedure (Sham or UDP) and treatment (Standard diet or Enriched diet) as factors, while Two-way repeated measures (RM) ANOVA were performed using groups and time as factors. The ANOVA were followed by Tukey post hoc test. In all test P<0.05 was regarded as statistically significative difference.

Results

Peritoneal Leukocytes Composition

The UPD group demonstrated a ~1.92-fold increase in basophils; ~1.89-fold in eosinophils; ~10.77-fold in neutrophils; ~2.05-fold in lymphocytes, ~2.25-fold in macrophages, and no changes in monocytes compared to Sham group. However, UPD + enriched diet prevented the alterations in basophils, eosinophils, neutrophils and lymphocytes, while there were no changes in the macrophage’s population compared to UPD group, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Effect of of A. maxima-enriched diet on peritoneal leukocytes populations on UPD.

Table 2.

Effect of of A. maxima-enriched diet on peritoneal leukocytes populations on UPD.

| Cells (106/mL) |

Sham |

Enriched diet |

UPD |

UPD +Enriched diet |

| Basophils |

0.48 ± 0.08 |

0.44 ± 0.10 |

0.92 ± 0.11* |

0.68 ± 0.09#

|

| Eosinophils |

8.5 ± 1.25 |

8.44 ± 1.3 |

16.06 ± 0.41* |

9.64 ± 0.84#

|

| Neutrophils |

1.04 ± 0.17 |

0.8 ± 0.34 |

11.2 ± 1.39* |

4.02 ± 1#

|

| Lymphocytes |

4.02 ± 0.43 |

4.46 ± 0.93 |

8.6 ± 1.13* |

4.42 ± 0.37#

|

| Monocytes |

3.64 ± 0.48 |

3.96 ± 0.93 |

4.84 ± 0.29 |

5.1 ± 0.26 |

| Macrophages |

9.74 ± 1.07 |

9.66 ± 1.29 |

22 ± 1.09* |

25.9 ± 2.55* |

Peritoneal Remodeling Markers

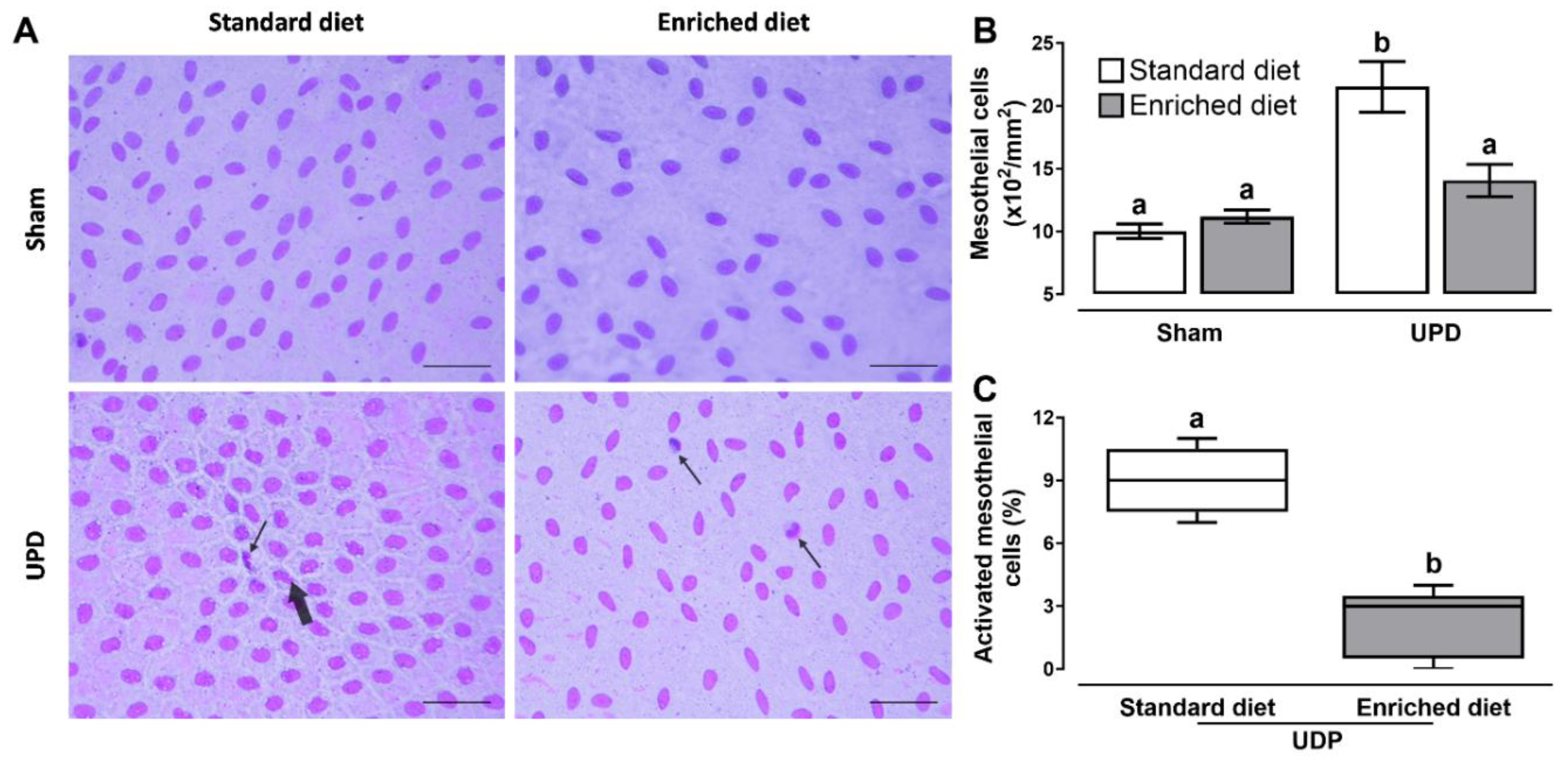

Figure 2 illustrates the effect of A. maxima- enriched diet on peritoneal remodeling markers. Panel B shows that the UPD rats exhibited a ~2.15-fold increase in cellularity, while UPD + enriched diet showed a ~1.14-fold increase compared to the Sham group. Additionally, the UPD groups displayed the presence of activated mesothelial cells, characterized by bone-shape nuclei (thick arrow) and indicating the first phase of transdifferentiate myofibroblast, as shown in panel C. This activation was reduced to ~24.4 in the UPD + enriched diet group when establishing as 100% the UPD group. Other cells (e.g. leukocytes) were also observed (thin arrow).

Figure 2. (A) Representative photomicrographs of liver imprints. Activated bone-shaped nuclei (thick arrow) and other cells (thin arrow). Wright’s stain at 400× magnification. The lower right bar represents 250 µm. (B) Morphometric cellularity and (C) activated mesothelial cells. In B the values represent mean ± SEM and were evaluated by Two-way RM ANOVA and Tukey post hoc test. In C the values represent median ± IQR and were evaluated by Mann-Whitney U-test. Different letters indicate significant differences (a≠b) P<0.05. UPD: uremic peritoneal dialysis.

Figure 2.

(A) Representative photomicrographs of liver imprints. Activated bone-shaped nuclei (thick arrow) and other cells (thin arrow). Wright’s stain at 400× magnification. The lower right bar represents 250 µm. (B) Morphometric cellularity and (C) activated mesothelial cells. In B the values represent mean ± SEM and were evaluated by Two-way RM ANOVA and Tukey post hoc test. In C the values represent median ± IQR and were evaluated by Mann-Whitney U-test. Different letters indicate significant differences (a≠b) P<0.05. UPD: uremic peritoneal dialysis.

Figure 2.

(A) Representative photomicrographs of liver imprints. Activated bone-shaped nuclei (thick arrow) and other cells (thin arrow). Wright’s stain at 400× magnification. The lower right bar represents 250 µm. (B) Morphometric cellularity and (C) activated mesothelial cells. In B the values represent mean ± SEM and were evaluated by Two-way RM ANOVA and Tukey post hoc test. In C the values represent median ± IQR and were evaluated by Mann-Whitney U-test. Different letters indicate significant differences (a≠b) P<0.05. UPD: uremic peritoneal dialysis.

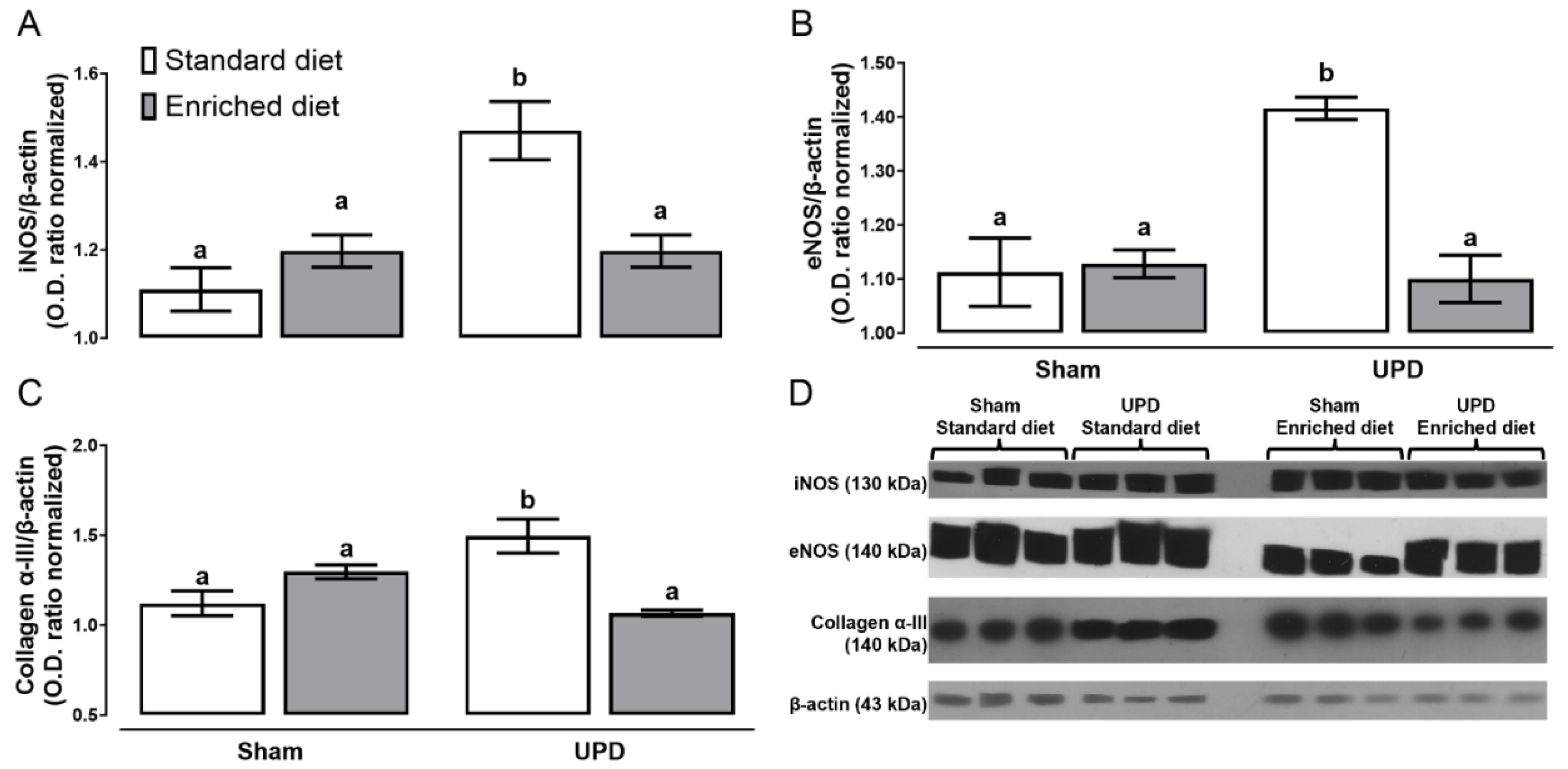

The effect of A. maxima on the expression of proteins associated with peritoneal remodeling are illustrated in Figure 3. The UPD groups exhibited higher levels of iNOS (~1.32-fold), eNOS(~1.27-fold), and collagen α-III expression (~1.33-fold), respect Sham group. In contrast, the UPD + enriched diet group did not show an increase in the expression of these proteins compared to Sham.

Figure 3. Effect of A. maxima-enriched diet on (A) iNOS, (B) eNOS, and (C) Collagen α- III as peritoneal remodeling markers of uremic peritoneal dialysis. The values represent mean ± SEM. Two-way ANOVA and Tukey post hoc test. Different letters indicate significant differences (a ≠ b ≠ c) P<0.05. UPD: uremic peritoneal dialysis.

Figure 3.

Effect of A. maxima-enriched diet on (A) iNOS, (B) eNOS, and (C) Collagen α- III as peritoneal remodeling markers of uremic peritoneal dialysis. The values represent mean ± SEM. Two-way ANOVA and Tukey post hoc test. Different letters indicate significant differences (a ≠ b ≠ c) P<0.05. UPD: uremic peritoneal dialysis.

Figure 3.

Effect of A. maxima-enriched diet on (A) iNOS, (B) eNOS, and (C) Collagen α- III as peritoneal remodeling markers of uremic peritoneal dialysis. The values represent mean ± SEM. Two-way ANOVA and Tukey post hoc test. Different letters indicate significant differences (a ≠ b ≠ c) P<0.05. UPD: uremic peritoneal dialysis.

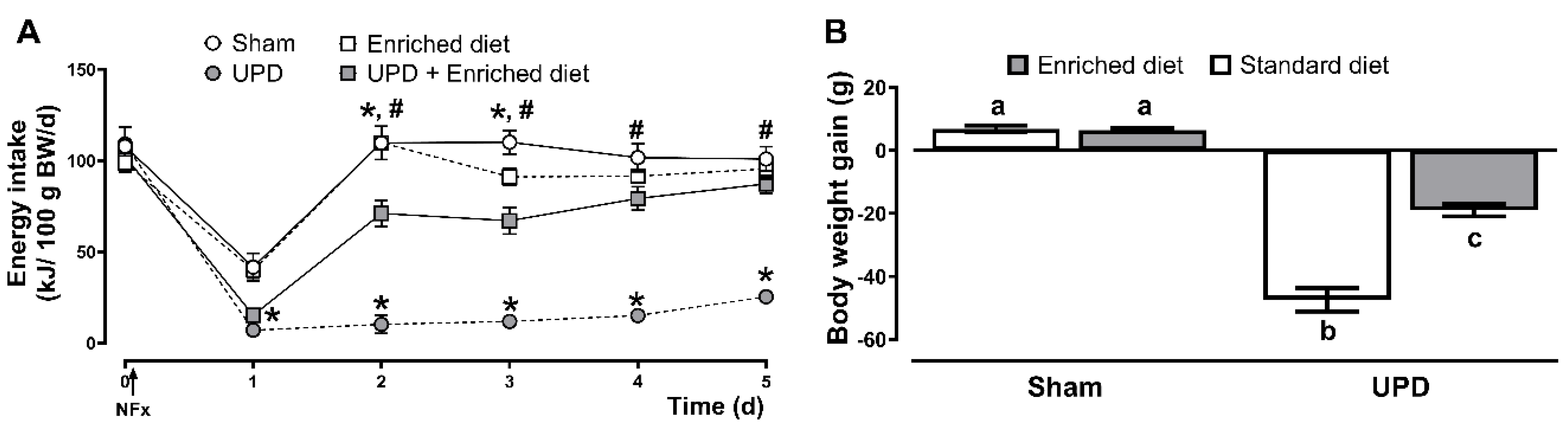

Protein-Energy Wasting Evaluation

The effects of the A. maxima-enriched diet on energy intake and body weight in UPD rats are presented in Figure 4. All groups experienced a reduction in energy intake the day following surgery with a decrease of ~60-62% for Sham groups, while the UPD groups exhibited a larger reduction of ~82-86%. In the following days, sham and enriched diet groups fully restored their energy intake, while the UPD group (receiving the standard diet) did not. However, providing the enriched diet to the UPD group resulted in a gradual recovery, reaching near baseline levels by day three. In terms of body weight, the UPD group showed a ~17% weight loss, while UPD + enriched diet experienced a moderate loss of ~6%, both respected to Sham group.

Figure 4. Effect of A. maxima-enriched diet on (A) energy intake, and (B) body weight on uremic peritoneal dialysis. The values represent mean ± SEM. (A) was evaluated by RM Two-Way ANOVA and Tukey post hoc test. (*) P< 0.05 vs Sham at same time; (#) P< 0.05 vs UPD at same time. (B) was evaluated by Two-Way ANOVA and Tukey post hoc test. Different letters indicate significant differences (a ≠ b ≠ c) P<0.05. UPD: uremic peritoneal dialysis.

Figure 4.

Effect of A. maxima-enriched diet on (A) energy intake, and (B) body weight on uremic peritoneal dialysis. The values represent mean ± SEM. (A) was evaluated by RM Two-Way ANOVA and Tukey post hoc test. (*) P< 0.05 vs Sham at same time; (#) P< 0.05 vs UPD at same time. (B) was evaluated by Two-Way ANOVA and Tukey post hoc test. Different letters indicate significant differences (a ≠ b ≠ c) P<0.05. UPD: uremic peritoneal dialysis.

Figure 4.

Effect of A. maxima-enriched diet on (A) energy intake, and (B) body weight on uremic peritoneal dialysis. The values represent mean ± SEM. (A) was evaluated by RM Two-Way ANOVA and Tukey post hoc test. (*) P< 0.05 vs Sham at same time; (#) P< 0.05 vs UPD at same time. (B) was evaluated by Two-Way ANOVA and Tukey post hoc test. Different letters indicate significant differences (a ≠ b ≠ c) P<0.05. UPD: uremic peritoneal dialysis.

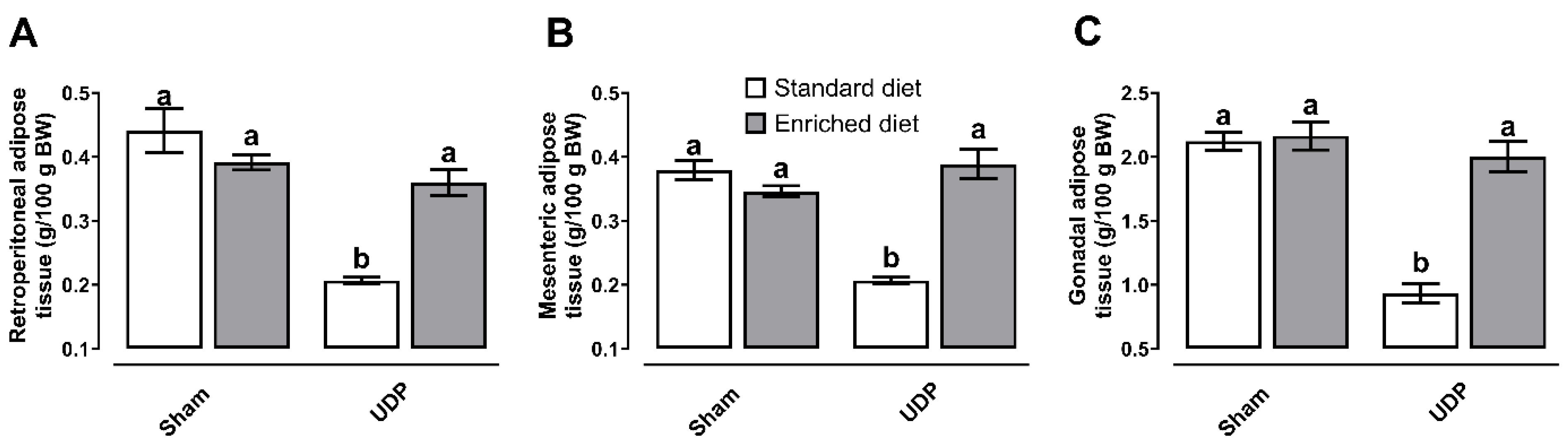

As it is deployed in Figure 5, the UPD group exhibited reductions in retroperitoneal (~45%), mesenteric (~66%), and gonadal (~46%) adipose tissues while in contrast, adipose tissue deposits were protected in the UPD + Enriched diet group, both compared to Sham group.

Figure 5. Effect of A. maxima-enriched diet on (A) retroperitoneal, (B) mesenteric, and (C) gonadal adipose tissue deposits on uremic peritoneal dialysis. The values represent mean ± SEM. Two-Way ANOVA and Tukey post hoc test. Different letters indicate significant differences (a ≠ b) P<0.05. UPD: uremic peritoneal dialysis.

Figure 5.

Effect of A. maxima-enriched diet on (A) retroperitoneal, (B) mesenteric, and (C) gonadal adipose tissue deposits on uremic peritoneal dialysis. The values represent mean ± SEM. Two-Way ANOVA and Tukey post hoc test. Different letters indicate significant differences (a ≠ b) P<0.05. UPD: uremic peritoneal dialysis.

Figure 5.

Effect of A. maxima-enriched diet on (A) retroperitoneal, (B) mesenteric, and (C) gonadal adipose tissue deposits on uremic peritoneal dialysis. The values represent mean ± SEM. Two-Way ANOVA and Tukey post hoc test. Different letters indicate significant differences (a ≠ b) P<0.05. UPD: uremic peritoneal dialysis.

The biochemical serum markers of protein-energy wasting are shown in Table 3. The UPD group showed decreased albumin (~25%), total proteins (~20%), triglycerides (~22%), and cholesterol (~35%) concentrations, compared to Sham group. In the other hand, the UPD + enriched diet group exhibited a lesser reduction in albumin (~9%), and total proteins (~16%) concentration, while maintained levels of triglycerides and cholesterol, respect to Sham group.

Table 3.

Effect of A. maxima-enriched diet on metabolic parameters.

Table 3.

Effect of A. maxima-enriched diet on metabolic parameters.

| Parameter |

Sham |

Enriched diet |

UPD |

UPD +Enriched diet |

| Albumin (g/dL) |

3.20 ± 0.09 |

3.40 ± 0.1 |

2.58 ± 0.21* |

3.1 ± 0.12#

|

| Total proteins (g/dL) |

6.42 ± 0.18 |

6.46 ± 0.24 |

5.24 ± 0.15* |

6.22 ± 0.1#

|

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) |

73.91 ± 1.68 |

74.70 ± 2.64 |

58.63 ± 2.18* |

69.42 ± 2.35*,#

|

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) |

68.05 ± 2.97 |

68.73 ± 2.67 |

44.82 ± 3.48* |

61.67 ± 2.79*,#

|

Discussion

Previous research shew that A. maxima possess nephroprotective effects against acute kidney injury and chronic kidney disease (Memije-Lazaro et al., 2018; Rojas-Franco et al., 2022), primarily through its antioxidant, anti-inflammatory effects (Acharya et al., 2023). Our study demonstrates that A. maxima may modulate key pathophysiological processes in a UPD-induced peritoneal remodeling and protein-energy wasting, highlighting its potential as therapeutic intervention in renal failure management.

Bilateral nephrectomy leads to an accumulation of serum nitrogen compounds as model of renal failure (Fujii et al., 2009). Following PD sessions, nitrogenous compound levels normalized, confirming model’s efficacy. Furthermore, neither natremia nor kalemia were disturbed through the study, despite the inherent risk of hypokalemia associated with potassium-free dialysis solutions(Borrelli et al., 2020; Mirmiran et al., 2018). These findings indicate that the implemented UPD model not only reduces uremic state effectively but also prevented hydroelectrolytic impairments, highlighting its potential as a platform to the study of short-term uremic peritoneal complications.

To evaluate the beneficial effects of A. maxima as functional food in UPD, it was provided in a 20% A. maxima-enriched diet to assess its effect in peritoneal remodeling. Peritoneal inflammation is the principal contributor to peritoneal dialysis complications development (Zareie et al., 2005). Our results show that A. maxima prevents UPD-induced fibrosis and PEW. These effects may be attributed to its principal bioactive compound, CPC (Jayanti et al., 2021; Rojas-Franco et al., 2022). After ingestion, it is released from A. maxima (Blas-Valdivia et al., 2022), and undergoes digestion of both gastric and intestinal phases, leads to the breakdown of CPC into bioactive peptides and phycocyanobilin (PCB), which is proposed to be the principal mediator of CPC's biological activity (Gligorijević et al., 2021; Pentón-Rol et al., 2018). In agreement with this hypothesis, PCB prevents peritoneal fibrosis by downregulating type III α-collagen, an integral component of the fibrotic collagen matrix, potentially via inhibition of the TGF-β/Smad3 signaling pathway (Q. Li et al., 2021). Moreover, the expression of eNOS, which is correlated with the degree of angiogenesis (Zhang et al., 2017), was reduced due to A. maxima, may interfering with the VEGF-A/ VEGFR-2 axis (Jayanti et al., 2021). In parallel, iNOS, which is typically associated with acute inflammation (Pérez & Rius-Pérez, 2022), was also downregulated indicating that A. maxima modulates UPD-induced peritoneal inflammation and it’s supported by the reduction in basophils, eosinophils, neutrophils, and lymphocytes levels in peritoneum. These reductions are endorsed mediated through the inhibition of proinflammatory cytokines, like IL-1, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-8, IL-5, limiting the migration of leukocyte to the peritoneum and selectively suppressing the acute inflammatory response (Y. Li, 2022; Liu et al., 2022). Furthermore, our data supports that CPC might influence macrophage reprograming, favoring a transition towards a pro-resolving M2 phenotype (Mundo-Franco et al., 2024).This shift in macrophage polarization is consistent with a reduction in inflammatory activity and may contribute to a more favorable microenvironment for resolving inflammation and reducing fibrosis (Balzer, 2020).

Protein-energy wasting (PEW) is characterized by the decrease in body stores of energy reserves (Dukkipati & Kopple, 2009). PEW development is a complex multifactorial process involving inflammation, decreased food intake, dialysate nutrient losses, metabolic acidosis, hormonal disorders, and diminished antioxidant levels, among other factors (Carrero et al., 2013). With an estimated prevalence of 75%, PEW is a key factor which increases mortality in PD patients’ principle due to the loss of the adipose tissue reserves (Yamada et al., 2020). In renal failure, uremia-caused anorexia is a higher contributor to PEW, and it is exacerbated by alteration in production of orexigenic and anorexigenic hormones (Bonanni et al., 2011).

Previous studies have highlighted the efficacy of A. maxima in nutritional recovery as nutritional supplementation due to its high protein source (Sinha et al., 2018). Elevated cortisol level and uremic toxins are highly correlated with inflammation process and exacerbate protein and lipid catabolism, contributing anorexia (Haque et al., 2013). By reducing cortisol levels, A. maxima may play a crucial role in improving appetite recovery, as evidenced by increased energy intakes in UPD when A. maxima is provided (Mishra et al., 2023). This effect may be also mediated through the decrease in leptin and glucagon-like peptide-1, and increase in agouti-related protein and ghrelin, which are critical regulators of appetite and energy balance (Abadjieva et al., 2018; Korczynska et al., 2021). In this context, the current results show that A. maxima prevents the reduction of serum protein and lipids. Additionally, A. maxima mitigates the reduction of adipose tissue deposits, which leads to the release of accumulated uremic toxins, contributing to systemic toxicity and exacerbating PEW by increasing catabolism and inducing anorexia (Bonanni et al., 2011; Dukkipati & Kopple, 2009).

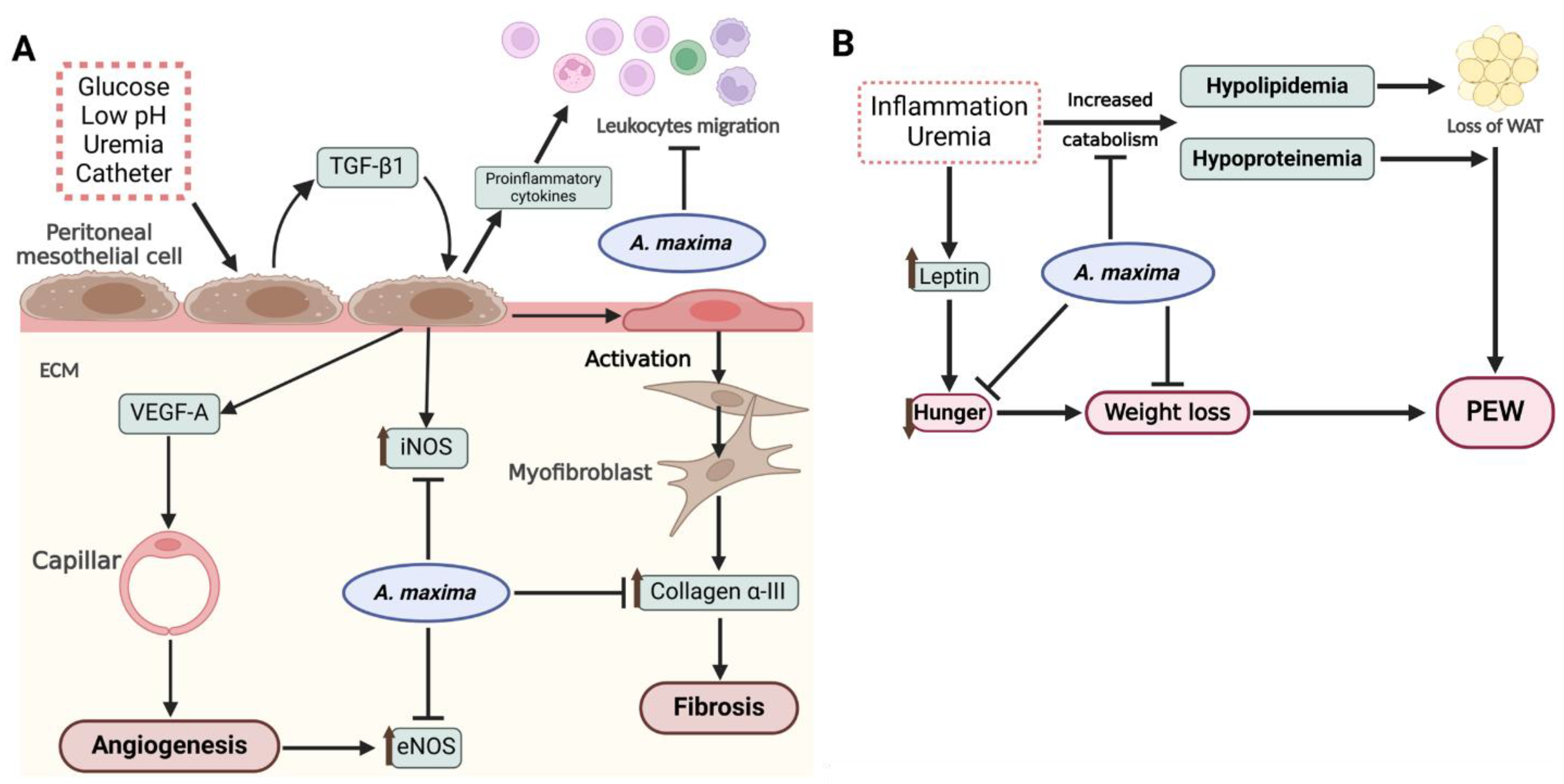

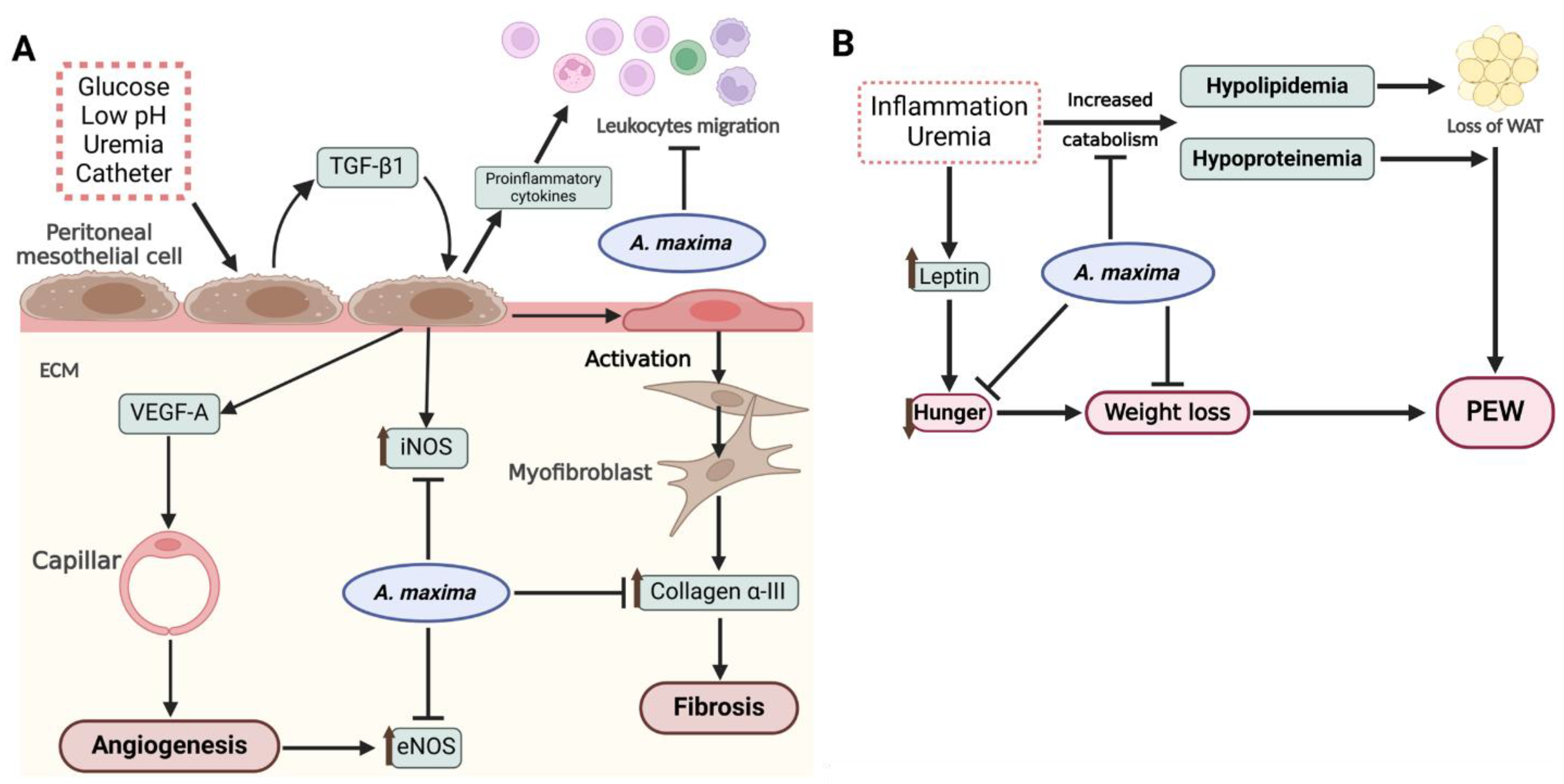

In summary, Figure 6 shows the potential mechanisms of A. maxima in inflammatory and metabolic complications in the uremic peritoneal dialysis.

Figure 6. (A) In the peritoneum, the high glucose concentrations and low pH of dialysis solution, uremia, and the catheter itself trigger the release of TGF-β1 and other proinflammatory cytokines. The autocrine action of TGF-β1 induces the expression of iNOS, VEGF-A, and subsequent angiogenesis, which is evidenced by the upregulation of eNOS. Additionally, TGF-β1 mediates the activation of mesothelial cells to myofibroblasts through MMT thereby initiating fibrosis within the ECM. Concurrently, proinflammatory cytokines promote leukocyte migration, further enhancing peritoneal inflammation. A. maxima, through its bioactive compounds released upon digestion, attenuates the angiogenic and fibrotic processes in the ECM, while also modules leukocyte migration to an anti-inflammatory process. (B) Renal failure and inflammation contribute to the development of PEW by increasing the catabolism of proteins and lipids, leading to hypoproteinemia and hypolipidemia resulting in the depletion of WAT. An elevation in leptin and other anorexigenic hormones suppress appetite and facilitate weight loss. A. maxima showed to prevent the onset of PEW by mitigating the disturbances in lipidemia and proteinemia, while also promoting appetite and preventing weight loss. Created with Biorender.com. ECM: extracellular matrix; MMT: mesothelial-to-mesenchymal transition, PEW: protein-energy wasting; WAT: white adipose tissue.

Figure 6.

(A) In the peritoneum, the high glucose concentrations and low pH of dialysis solution, uremia, and the catheter itself trigger the release of TGF-β1 and other proinflammatory cytokines. The autocrine action of TGF-β1 induces the expression of iNOS, VEGF-A, and subsequent angiogenesis, which is evidenced by the upregulation of eNOS. Additionally, TGF-β1 mediates the activation of mesothelial cells to myofibroblasts through MMT thereby initiating fibrosis within the ECM. Concurrently, proinflammatory cytokines promote leukocyte migration, further enhancing peritoneal inflammation. A. maxima, through its bioactive compounds released upon digestion, attenuates the angiogenic and fibrotic processes in the ECM, while also modules leukocyte migration to an anti-inflammatory process. (B) Renal failure and inflammation contribute to the development of PEW by increasing the catabolism of proteins and lipids, leading to hypoproteinemia and hypolipidemia resulting in the depletion of WAT. An elevation in leptin and other anorexigenic hormones suppress appetite and facilitate weight loss. A. maxima showed to prevent the onset of PEW by mitigating the disturbances in lipidemia and proteinemia, while also promoting appetite and preventing weight loss. Created with Biorender.com. ECM: extracellular matrix; MMT: mesothelial-to-mesenchymal transition, PEW: protein-energy wasting; WAT: white adipose tissue.

Figure 6.

(A) In the peritoneum, the high glucose concentrations and low pH of dialysis solution, uremia, and the catheter itself trigger the release of TGF-β1 and other proinflammatory cytokines. The autocrine action of TGF-β1 induces the expression of iNOS, VEGF-A, and subsequent angiogenesis, which is evidenced by the upregulation of eNOS. Additionally, TGF-β1 mediates the activation of mesothelial cells to myofibroblasts through MMT thereby initiating fibrosis within the ECM. Concurrently, proinflammatory cytokines promote leukocyte migration, further enhancing peritoneal inflammation. A. maxima, through its bioactive compounds released upon digestion, attenuates the angiogenic and fibrotic processes in the ECM, while also modules leukocyte migration to an anti-inflammatory process. (B) Renal failure and inflammation contribute to the development of PEW by increasing the catabolism of proteins and lipids, leading to hypoproteinemia and hypolipidemia resulting in the depletion of WAT. An elevation in leptin and other anorexigenic hormones suppress appetite and facilitate weight loss. A. maxima showed to prevent the onset of PEW by mitigating the disturbances in lipidemia and proteinemia, while also promoting appetite and preventing weight loss. Created with Biorender.com. ECM: extracellular matrix; MMT: mesothelial-to-mesenchymal transition, PEW: protein-energy wasting; WAT: white adipose tissue.

Conclusions

Our findings provide evidence that dietary supplementation with 20% A. maxima effectively modulates peritoneal dialysis-induced peritoneal inflammation and protein-energy wasting. By targeting inflammatory pathways. A. maxima demonstrates its potential not only to reduce complications associated with peritoneal dialysis but also to prevent anorexia, minimize weight loss, and preserve adipose tissue. These results highlight A. maxima as a promising therapeutic strategy for improving the nutritional status of patients undergoing peritoneal dialysis. Future research should further explore its molecular mechanisms and long-term clinical applications to optimize its use in combating systemic complications of renal failure.

Funding

This study was supported by SIP-IPN y SECIHTI, grant numbers: SIP 20251106 (M.F.-C.) y SIPCD0012025 (E.C.-E.).

Author contributions

Conceptualization (E.C.-E., O.I.F.-S.); Formal analysis (O.I.F.-S.); Research (O.I.F.-S., P.R.-F.); Methodology (O.I.F.-S., R.A.G.-E.); Resources (E.C.-E., P.R.-F., M.F.-C.); Software (O.I.F.-S.); Writing the original draft (O.I.F.-S.); Writing, review and editing (E.C.-E., M.F.-C., Z.M.-F.); Acquisition of funds (P.R.-F., E.C.-E., M.F.-C.).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethical Considerations

The protocol for this study was approved by the Institutional Animal Ethical Committee (CEI-ENCB), ZOO-003-2024.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors declare no conflicts of interest in this work.

Author contributions

Conceptualization (E.C.-E., O.I.F.-S.); Formal analysis (O.I.F.-S.); Research (O.I.F.-S., P.R.-F.); Methodology (O.I.F.-S., R.A.G.-E.); Resources (E.C.-E., P.R.-F., M.F.-C.); Software (O.I.F.-S.); Writing the original draft (O.I.F.-S.); Writing, review and editing (E.C.-E., M.F.-C., Z.M.-F.); Acquisition of funds (P.R.-F., E.C.-E., M.F.-C.).

References

- Abadjieva, D. , Nedeva, R., Marchev, Y., Jordanova, G., Chervenkov, M., Dineva, J., Shimkus, A., Shimkiene, A., Teerds, K., & Kistanova, E. (2018). Arthrospira (Spirulina) platensis supplementation affects folliculogenesis, progesterone and ghrelin levels in fattening pre-pubertal gilts. Journal of Applied Phycology, 30, 1, 445–452. [CrossRef]

- Acharya, B. , Swami Narsingh, Bhasker Joshi, & Rajesh Kumar Mishra. (2023). Spirulina: A Miraculous alga with Pharmaco-nutraceutical Potential as Future Food. International Journal of Food, Nutrition and Dietetics, 11, 3, 127–136.

- Balzer, M. S. (2020). Molecular pathways in peritoneal fibrosis. Cellular Signalling, 75, 109778. [CrossRef]

- Bello, A. K. , Okpechi, I. G., Osman, M. A., Cho, Y., Cullis, B., Htay, H., Jha, V., Makusidi, M. A., McCulloch, M., Shah, N., Wainstein, M., & Johnson, D. W. (2022). Epidemiology of peritoneal dialysis outcomes. Nature Reviews Nephrology 18(12), 779–793. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blas-Valdivia, V. , Moran-Dorantes, D., Rojas Franco, P., Franco-Colin, M., Mirhosseini, N., Davarnejad, R., Halajisani, A., Tavakoli, O., & Cano-Europa, E. (2022). C-Phycocyanin prevents acute myocardial infarction-induced oxidative stress, inflammation and cardiac damage. Pharmaceutical Biology, 60, 755–763. [CrossRef]

- Bonanni, A. , Mannucci, I., Verzola, D., Sofia, A., Saffioti, S., Gianetta, E., & Garibotto, G. (2011). Protein-Energy Wasting and Mortality in Chronic Kidney Disease. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 8, 1631–1654. [CrossRef]

- Borrelli, S. , De Nicola, L., Minutolo, R., Perna, A., Provenzano, M., Argentino, G., Cabiddu, G., Russo, R., La Milia, V., De Stefano, T., Conte, G., & Garofalo, C. (2020). Sodium toxicity in peritoneal dialysis: Mechanisms and “solutions”. Journal of Nephrology, 33, 1, 59–68. [CrossRef]

- Carrero, J. J. , Stenvinkel, P., Cuppari, L., Ikizler, T. A., Kalantar-Zadeh, K., Kaysen, G., Mitch, W. E., Price, S. R., Wanner, C., Wang, A. Y. M., ter Wee, P., & Franch, H. A. (2013). Etiology of the Protein-Energy Wasting Syndrome in Chronic Kidney Disease: A Consensus Statement From the International Society of Renal Nutrition and Metabolism (ISRNM). Journal of Renal Nutrition, 23, 2, 77–90. [CrossRef]

- DiNicolantonio, J. J. , McCarty, M. F., Barroso-Aranda, J., Assanga, S., Lujan, L. M. L., & O’Keefe, J. H. (2021). A nutraceutical strategy for downregulating TGFβ signalling: Prospects for prevention of fibrotic disorders, including post-COVID-19 pulmonary fibrosis. Open Heart, 8, 1, e001663. [CrossRef]

- DOF. (1999). NOM-062-ZOO-1999: Especificaciones técnicas para la producción, cuidado y uso de los animales de laboratorio.

- Dukkipati, R. , & Kopple, J. D. (2009). Causes and Prevention of Protein-Energy Wasting in Chronic Kidney Failure. Seminars in Nephrology, 29, 1, 39–49. [CrossRef]

- Fujii, Y. , Yamauchi, K., Kokuba, Y., & Kikuchi, T. (2009). New Peritoneal Dialysis Model in Rats with Bilateral Nephrectomy. Renal Failure 31(5), 365–371. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gligorijević, N. , Minić, S., Radibratović, M., Papadimitriou, V., Nedić, O., Sotiroudis, T. G., & Nikolić, M. R. (2021). Nutraceutical phycocyanobilin binding to catalase protects the pigment from oxidation without affecting catalytic activity. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy, 251, 119483. [CrossRef]

- Haque, Z. , Akbar, N., Yasmin, F., Haleem, M. A., & Haleem, D. J. (2013). Inhibition of immobilization stress-induced anorexia, behavioral deficits, and plasma corticosterone secretion by injected leptin in rats. Stress, 16, 3, 353–362. [CrossRef]

- Hekking, L. H. P. , Zareie, M., Driesprong, B. A. J., Faict, D., Welten, A. G. A., de Greeuw, I., Schadee-Eestermans, I. L., Havenith, C. E. G., van den Born, J., Ter Wee, P. M., & Beelen, R. H. J. (2001). Better Preservation of Peritoneal Morphologic Features and Defense in Rats after Long-Term Exposure to a Bicarbonate/Lactate-Buffered Solution. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, 12, 12, 2775–2786. [CrossRef]

- Jayanti, D. A. P. I. S. , Abimanyu, I. G. A., & Azzamudin, H. (2021). Spirulina platensis’s phycocyanobilin as an antiangiogenesis by inhibiting VEGFR2-VEGFA pathway in breast cancer: In silico study. JSMARTech, 2, 3, 87–91. [CrossRef]

- Korczynska, J. , Czumaj, A., Chmielewski, M., Swierczynski, J., & Sledzinski, T. (2021). The Causes and Potential Injurious Effects of Elevated Serum Leptin Levels in Chronic Kidney Disease Patients. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22, 9, 4685. [CrossRef]

- Lafarga, T. , Fernández-Sevilla, J. M., González-López, C., & Acién-Fernández, F. G. (2020). Spirulina for the food and functional food industries. Food Research International, 137, 109356. [CrossRef]

- Li, C. , Yu, Y., Li, W., Liu, B., Jiao, X., Song, X., Lv, C., & Qin, S. (2017). Phycocyanin attenuates pulmonary fibrosis via the TLR2-MyD88-NF-κB signaling pathway. Scientific Reports, 7, 1, 5843. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q. , Peng, W., Zhang, Z., Pei, X., Sun, Z., & Ou, Y. (2021). A phycocyanin derived eicosapeptide attenuates lung fibrosis development. European Journal of Pharmacology 908, 174356. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y. (2022). The Bioactivities of Phycocyanobilin from Spirulina. Journal of Immunology Research, 2022, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Liu, R. , Qin, S., & Li, W. (2022). Phycocyanin: Anti-inflammatory effect and mechanism. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy, 153, 113362. [CrossRef]

- Memije-Lazaro, I. N. , Blas-Valdivia, V., Franco-Colín, M., & Cano-Europa, E. (2018). Arthrospira maxima (Spirulina) and C-phycocyanin prevent the progression of chronic kidney disease and its cardiovascular complications. Journal of Functional Foods, 43, 37–43. [CrossRef]

- Mirmiran, P. , Nazeri, P., Bahadoran, Z., Khalili-Moghadam, S., & Azizi, F. (2018). Dietary Sodium to Potassium Ratio and the Incidence of Chronic Kidney Disease in Adults: A Longitudinal Follow-Up Study. Preventive Nutrition and Food Science, 23, 2, 87–93. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P. , Kumar, S., & Malik, J. K. (2023). Molecular Mechanistic Insight Spirulina as Anti-stress Agent. Middle East Research Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, 3, 02, 25–30. [CrossRef]

- Mundo-Franco, Z. , Luna-Herrera, J., Castañeda-Sánchez, J. I., Serrano-Contreras, J. I., Rojas-Franco, P., Blas-Valdivia, V., Franco-Colín, M., & Cano-Europa, E. (2024). C-Phycocyanin Prevents Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Lung Remodeling in an Ovalbumin-Induced Rat Asthma Model. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 25, 13, 7031. [CrossRef]

- Pentón-Rol, G. , Marín-Prida, J., & Falcón-Cama, V. (2018). C-Phycocyanin and Phycocyanobilin as Remyelination Therapies for Enhancing Recovery in Multiple Sclerosis and Ischemic Stroke: A Preclinical Perspective. Behavioral Sciences, 8, 1, 15. [CrossRef]

- Pérez, S. , & Rius-Pérez, S. (2022). Macrophage Polarization and Reprogramming in Acute Inflammation: A Redox Perspective. Antioxidants, 11, 7, 1394. [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Franco, P. , Franco-Colín, M., Blas-Valdivia, V., Melendez-Camargo, M. E., & Cano-Europa, E. (2021). Arthrospira maxima (Spirulina) prevents endoplasmic reticulum stress in the kidney through its C-phycocyanin. Journal of Zhejiang University-SCIENCE B, 22, 7, 603–608. [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Franco, P. , Garcia-Pliego, E., Vite-Aquino, A. G., Franco-Colin, M., Serrano-Contreras, J. I., Paniagua-Castro, N., Gallardo-Casas, C. A., Blas-Valdivia, V., & Cano-Europa, E. (2022). The Nutraceutical Antihypertensive Action of C-Phycocyanin in Chronic Kidney Disease Is Related to the Prevention of Endothelial Dysfunction. Nutrients, 14, 7, 1464. [CrossRef]

- Roumeliotis, S. , Dounousi, E., Salmas, M., Eleftheriadis, T., & Liakopoulos, V. (2020). Unfavorable Effects of Peritoneal Dialysis Solutions on the Peritoneal Membrane: The Role of Oxidative Stress. Biomolecules, 10, 5, 768. [CrossRef]

- Sinha, S. , Patro, N., & Patro, I. K. (2018). Maternal Protein Malnutrition: Current and Future Perspectives of Spirulina Supplementation in Neuroprotection. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 12. [CrossRef]

- Uiterwijk, H. , Franssen, C. F. M., Kuipers, J., Westerhuis, R., & Nauta, F. L. (2020). Glucose Exposure in Peritoneal Dialysis Is a Significant Factor Predicting Peritonitis. American Journal of Nephrology 51(3), 237–243. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasquez-Jimenez, E. , & Madero, M. (2020). Global Dialysis Perspective: Mexico. Kidney360, 1, 6, 534–537. [CrossRef]

- Yamada, S. , Nakano, T., Tsuneyoshi, S., Arase, H., Shimamoto, S., Taniguchi, M., Tokumoto, M., Hirakata, H., Ooboshi, H., Tsuruya, K., & Kitazono, T. (2020). Association between modified simple protein-energy wasting (PEW) score and all-cause mortality in patients receiving maintenance hemodialysis. Renal Replacement Therapy, 6, 1, 39. [CrossRef]

- Zareie, M. , De Vriese, A. S., Hekking, L. H. P., ter Wee, P. M., Schalkwijk, C. G., Driesprong, B. A. J., Schadee-Eestermans, I. L., Beelen, R. H. J., Lameire, N., & van den Born, J. (2005). Immunopathological changes in a uraemic rat model for peritoneal dialysis. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation, 20, 7, 1350–1361. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. , Jiang, N., & Ni, Z. (2017). Strategies for preventing peritoneal fibrosis in peritoneal dialysis patients: New insights based on peritoneal inflammation and angiogenesis. Frontiers of Medicine, 11, 3, 349–358. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).