Submitted:

11 January 2025

Posted:

14 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

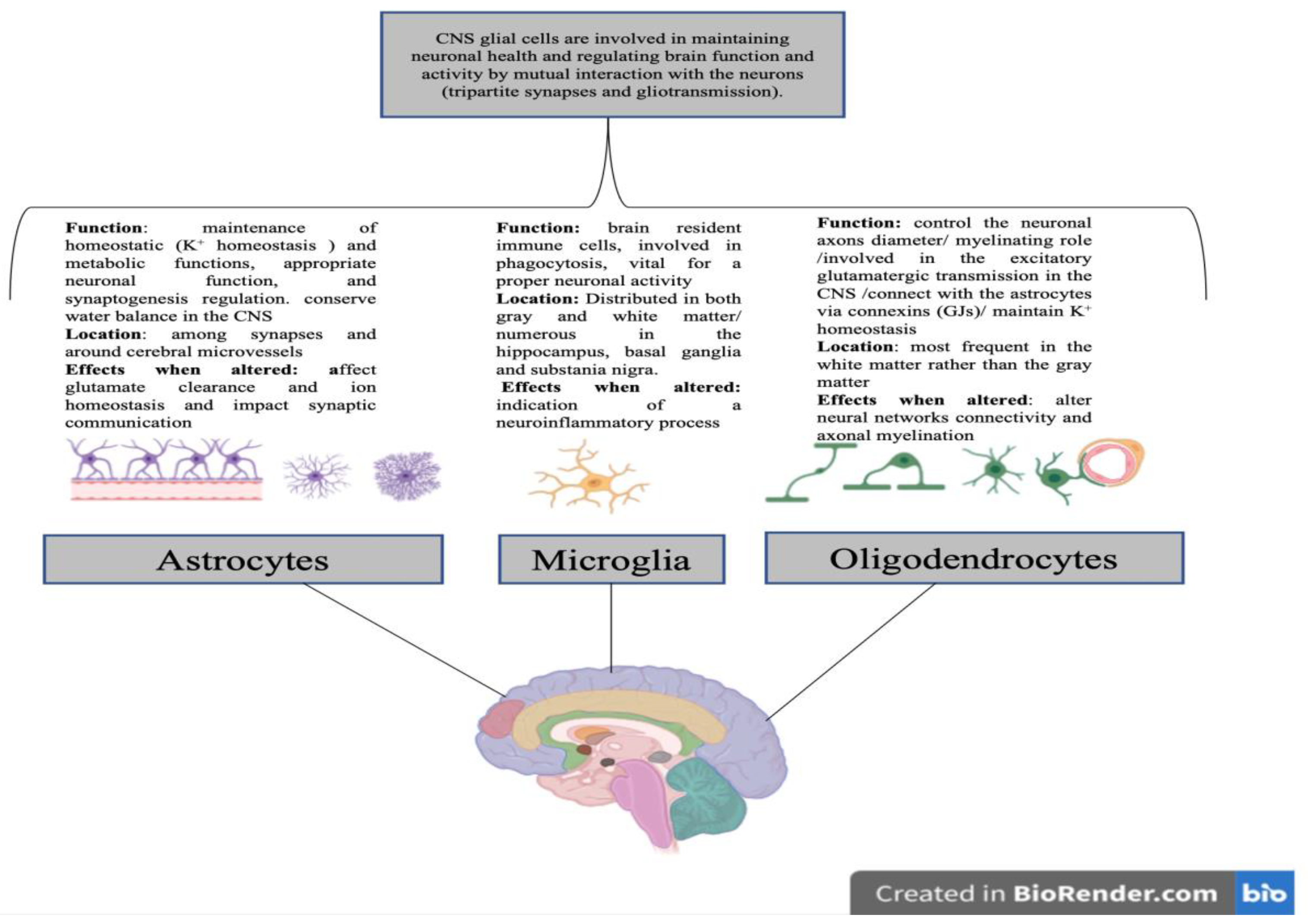

Glial cells have shown to possess vital and surprising roles in the brain rather than just being silent supportive cells to neurons. Different glial populations of the central nervous system in involved brain regions play various functions, express different proteins and result in fluctuating effects when altered. Glial cells pathologies were detected in most mental disorders including suicidal behavior. Suicidal behavior represents a health problem of high importance worldwide where protective measures are required to be taken at many levels. Studies on patients with mental disorders that represent risk factors for suicidal behavior, revealed multiple changes in the glia at diverse levels including variations regarding the expressed glial markers. This review summarizes the role of glia in some psychiatric disorders and highlights the crosslink between changes at the level of glial cells and development of suicidal behavior in patients with an underlying psychiatric condition; In addition, the interplay and interconnection between suicidal behavior and other mental diseases will spot the light on the routes of personalized therapy involving glial-related drugs.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Glial Cells

2.1. Glial Cells Functions

2.2. Glio-Pathologies: Markers Involved

| Glial Cells | Markers Expressed | Brain Region | Brain/Mental Disorders | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Astrocytes |

|

|

|

[4], [23], [32], [33] |

| Microglia |

|

|

|

[4], [32] |

| Oligodendrocytes |

|

|

|

[4], [32] |

| Ependymal Cells |

|

|

|

[5] |

3. Glial Cells and SB

4. Suicidal Behavior and Mental Disorders

4.1. SB and Major Depressive Disorder (MDD)

4.2. SB and Schizophrenia

4.3. SB and Bipolar Disorder (BD)

4.4. SB and Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD)

4.5. SB and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

4.6. SB and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

4.7. SB and Anxiety Disorders

4.8. SB and Substance Use Disorders (SUDs)

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- S. Jäkel and L. Dimou, “Glial Cells and Their Function in the Adult Brain: A Journey through the History of Their Ablation,” Front Cell Neurosci, vol. 11, p. 24, 2017. [CrossRef]

- D. Andreeva, L. Murashova, N. Burzak, and V. Dyachuk, “Satellite Glial Cells: Morphology, functional heterogeneity, and role in pain,” Front Cell Neurosci, vol. 16, p. 1019449, 2022. [CrossRef]

- P. Gazerani, “Satellite Glial Cells in Pain Research: A Targeted Viewpoint of Potential and Future Directions,” Front Pain Res (Lausanne), vol. 2, p. 646068, 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. Huang, W. He, T. Tang, and M. Qiu, “Immunological Markers for Central Nervous System Glia,” Neurosci Bull, vol. 39, no. 3, Art. no. 3, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. N. Rasband, “Glial Contributions to Neural Function and Disease,” Mol Cell Proteomics, vol. 15, no. 2, Art. no. 2, Feb. 2016. [CrossRef]

- D. Kato, K. Eto, J. Nabekura, and H. Wake, “Activity-dependent functions of non-electrical glial cells,” J Biochem, vol. 163, no. 6, Art. no. 6, Jun. 2018. [CrossRef]

- J. W. Um, “Roles of Glial Cells in Sculpting Inhibitory Synapses and Neural Circuits,” Front Mol Neurosci, vol. 10, p. 381, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Y.-J. Jung and W.-S. Chung, “Phagocytic Roles of Glial Cells in Healthy and Diseased Brains,” Biomol Ther (Seoul), vol. 26, no. 4, Art. no. 4, Jul. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Y. J. Lee and Y.-K. Kim, “Neuron-to-microglia Crosstalk in Psychiatric Disorders,” Current Neuropharmacology, vol. 18, no. 2, Art. no. 2, Feb. 2020. [CrossRef]

- E. Kong et al., “Glycometabolism Reprogramming of Glial Cells in Central Nervous System: Novel Target for Neuropathic Pain,” Front Immunol, vol. 13, p. 861290, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Hyung, J.-H. Park, and K. Jung, “Application of optogenetic glial cells to neuron-glial communication,” Front Cell Neurosci, vol. 17, p. 1249043, 2023. [CrossRef]

- G. Magni, B. Riboldi, and S. Ceruti, “Human Glial Cells as Innovative Targets for the Therapy of Central Nervous System Pathologies,” Cells, vol. 13, no. 7, Art. no. 7, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- G. Rajkowska and J. J. Miguel-Hidalgo, “Gliogenesis and Glial Pathology in Depression,” CNS & neurological disorders drug targets, vol. 6, no. 3, Art. no. 3, Jun. 2007. [CrossRef]

- W. Shen, J. B. Pristov, P. Nobili, and L. Nikolić, “Can glial cells save neurons in epilepsy?,” Neural Regen Res, vol. 18, no. 7, Art. no. 7, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. S. Kim, J. Choi, and B.-E. Yoon, “Neuron-Glia Interactions in Neurodevelopmental Disorders,” Cells, vol. 9, no. 10, Art. no. 10, Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. N. Abou Chahla, M. I. Khalil, S. Comai, L. Brundin, S. Erhardt, and G. J. Guillemin, “Biological Factors Underpinning Suicidal Behaviour: An Update,” Brain Sciences, vol. 13, no. 3, p. 505, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. Baharikhoob and N. J. Kolla, “Microglial Dysregulation and Suicidality: A Stress-Diathesis Perspective,” Front Psychiatry, vol. 11, p. 781, Aug. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Aydin, Y. Hacimusalar, and Ç. Hocaoğlu, “İntihar Davranışının Nörobiyolojisi,” Psikiyatride Güncel Yaklaşımlar, vol. 11, no. 1, Art. no. 1, Mar. 2019. [CrossRef]

- C. A. Pereira, G. Reis-de-Oliveira, B. C. Pierone, D. Martins-de-Souza, and M. P. Kaster, “Depicting the molecular features of suicidal behavior: a review from an ‘omics’ perspective,” Psychiatry Res, vol. 332, p. 115682, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Yamamoto, M. Sakai, Z. Yu, M. Nakanishi, and H. Yoshii, “Glial Markers of Suicidal Behavior in the Human Brain-A Systematic Review of Postmortem Studies,” Int J Mol Sci, vol. 25, no. 11, Art. no. 11, May 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Ramsey, E. C. Martin, O. M. Purcell, K. M. Lee, and A. G. MacLean, “Self-injurious behaviours in rhesus macaques: Potential glial mechanisms,” J Intellect Disabil Res, vol. 62, no. 12, Art. no. 12, Dec. 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. B. Mayegowda and C. Thomas, “Glial pathology in neuropsychiatric disorders: a brief review,” Journal of Basic and Clinical Physiology and Pharmacology, vol. 30, no. 4, Art. no. 4, Jul. 2019. [CrossRef]

- G. A. Garden and B. M. Campbell, “Glial Biomarkers in Human Central Nervous System Disease,” Glia, vol. 64, no. 10, Art. no. 10, Oct. 2016. [CrossRef]

- N. Ochocka and B. Kaminska, “Microglia Diversity in Healthy and Diseased Brain: Insights from Single-Cell Omics,” Int J Mol Sci, vol. 22, no. 6, Art. no. 6, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Zlomuzica, L. Plank, I. Kodzaga, and E. Dere, “A fatal alliance: Glial connexins, myelin pathology and mental disorders,” Journal of Psychiatric Research, vol. 159, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Wang and Q. R. Lu, “Convergent epigenetic regulation of glial plasticity in myelin repair and brain tumorigenesis: A focus on histone modifying enzymes,” Neurobiology of Disease, vol. 144, p. 105040, Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- G. Poggi, M. Wennström, M. B. Müller, and G. Treccani, “NG2-glia: rising stars in stress-related mental disorders?,” Mol Psychiatry, vol. 28, no. 2, Art. no. 2, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- B. Czéh and S. A. Nagy, “Clinical Findings Documenting Cellular and Molecular Abnormalities of Glia in Depressive Disorders,” Front. Mol. Neurosci., vol. 11, Feb. 2018. [CrossRef]

- R. Wang, H. Ren, Y. Gao, and G. Wang, “Editorial: Role of Glial Cells of the Central and Peripheral Nervous System in the Pathogenesis of Neurodegenerative Disorders,” Front Aging Neurosci, vol. 14, p. 920861, May 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. Melzer, T. M. Freiman, and A. Derouiche, “Rab6A as a Pan-Astrocytic Marker in Mouse and Human Brain, and Comparison with Other Glial Markers (GFAP, GS, Aldh1L1, SOX9),” Cells, vol. 10, no. 1, Art. no. 1, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. You, X. Su, J. Ying, S. Li, Y. Qu, and D. Mu, “Research Progress on the Role of RNA m6A Modification in Glial Cells in the Regulation of Neurological Diseases,” Biomolecules, vol. 12, no. 8, Art. no. 8, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- “Neural and Glial Markers,” Cell Signaling Technology. Accessed: Dec. 03, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.cellsignal.com/science-resources/neural-and-glial-markers.

- “Radial glia markers | Abcam.” Accessed: Dec. 09, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.abcam.com/en-us/technical-resources/research-areas/marker-guides/radial-glia-cell-markers?srsltid=AfmBOopj_FF1TsMlan6FGhQzAERKHDV7Zj74OoMGolBEfmmqiq4VLfjZ.

- D. Laricchiuta et al., “The role of glial cells in mental illness: a systematic review on astroglia and microglia as potential players in schizophrenia and its cognitive and emotional aspects,” Front. Cell. Neurosci., vol. 18, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- L. Zhang, P. J. Lucassen, E. Salta, P. D. E. M. Verhaert, and D. F. Swaab, “Hippocampal neuropathology in suicide: Gaps in our knowledge and opportunities for a breakthrough,” Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, vol. 132, pp. 542–552, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- G. Turecki et al., “Suicide and suicide risk,” Nature Reviews Disease Primers, vol. 5, no. 74 (2019), Art. no. 74 (2019), Oct. 2019. [CrossRef]

- G. Turecki and D. A. Brent, “Suicide and suicidal behaviour,” Lancet, vol. 387, no. 10024, Art. no. 10024, Mar. 2016. [CrossRef]

- R. Brisch et al., “The role of microglia in neuropsychiatric disorders and suicide,” Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci, vol. 272, no. 6, Art. no. 6, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. J. Baldessarini, L. Tondo, M. Pinna, N. Nuñez, and G. H. Vázquez, “Suicidal risk factors in major affective disorders,” Br J Psychiatry, pp. 1–6, Jul. 2019. [CrossRef]

- B. Cabrera-Mendoza et al., “Brain Gene Expression Profiling of Individuals With Dual Diagnosis Who Died by Suicide,” J Dual Diagn, vol. 16, no. 2, Art. no. 2, 2020. [CrossRef]

- P. G. C. Almeida, J. V. Nani, J. P. Oses, E. Brietzke, and M. A. F. Hayashi, “Neuroinflammation and glial cell activation in mental disorders,” Brain, Behavior, & Immunity - Health, vol. 2, p. 100034, Feb. 2020. [CrossRef]

- R. P. Rajkumar, “Do enteric glial cells play a role in the pathophysiology of major depression?,” Explor Neurosci., vol. 3, no. 2, Art. no. 2, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Evrensel and N. Tarhan, “The Role of Glial Pathology in Pathophysiology and Treatment of Major Depression: Clinical and Preclinical Evidence,” in Translational Research Methods for Major Depressive Disorder, Y.-K. Kim and M. Amidfar, Eds., New York, NY: Springer US, 2022, pp. 21–34. [CrossRef]

- L. Zhang, R. W. H. Verwer, J. Zhao, I. Huitinga, P. J. Lucassen, and D. F. Swaab, “Changes in glial gene expression in the prefrontal cortex in relation to major depressive disorder, suicide and psychotic features,” J Affect Disord, vol. 295, pp. 893–903, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. A. Cobb et al., “Density of GFAP-immunoreactive astrocytes is decreased in left hippocampi in major depressive disorder,” Neuroscience, vol. 316, pp. 209–220, Mar. 2016. [CrossRef]

- X.-R. Qi, W. Kamphuis, and L. Shan, “Astrocyte Changes in the Prefrontal Cortex From Aged Non-suicidal Depressed Patients,” Front Cell Neurosci, vol. 13, p. 503, 2019. [CrossRef]

- T. Nagatsu, “Progress in Monoamine Oxidase (MAO) Research in Relation to Genetic Engineering,” NeuroToxicology, vol. 25, no. 1, Art. no. 1, Jan. 2004. [CrossRef]

- C. G. Toledo-Lozano et al., “Individual and Combined Effect of MAO-A/MAO-B Gene Variants and Adverse Childhood Experiences on the Severity of Major Depressive Disorder,” Behavioral Sciences, vol. 13, no. 10, Art. no. 10, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Jaisa-aad, T. Connors, B. Hyman, and A. Serrano-Pozo, “Characterization of the Monoamine Oxidase-B (MAO-B) Expression in Postmortem Normal and Alzheimer’s Disease Brains (S39.006),” Neurology, vol. 100, no. 17_supplement_2, Art. no. 17_supplement_2, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Jaisa-Aad, C. Muñoz-Castro, M. A. Healey, B. T. Hyman, and A. Serrano-Pozo, “Characterization of monoamine oxidase-B (MAO-B) as a biomarker of reactive astrogliosis in Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias,” Acta Neuropathol, vol. 147, no. 1, Art. no. 1, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Ekblom, S. S. Jossan, M. Bergström, L. Oreland, E. Walum, and S. M. Aquilonius, “Monoamine oxidase-B in astrocytes,” Glia, vol. 8, no. 2, Art. no. 2, Jun. 1993. [CrossRef]

- J. Tong et al., “Brain monoamine oxidase B and A in human parkinsonian dopamine deficiency disorders,” Brain, vol. 140, no. 9, Art. no. 9, Sep. 2017. [CrossRef]

- İ. Çetin, Ö. F. Demirel, T. Sağlam, N. Yıldız, and A. Duran, “Decreased serum levels of glial markers and their relation with clinical parameters in patients with schizophrenia,” J Clin Psy, vol. 26, no. 3, Art. no. 3, 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. C. Watkins, A. Sawa, and M. G. Pomper, “Glia and immune cell signaling in bipolar disorder: insights from neuropharmacology and molecular imaging to clinical application,” Transl Psychiatry, vol. 4, no. 1, Art. no. 1, Jan. 2014. [CrossRef]

- L. Naggan, E. Robinson, E. Dinur, H. Goldenberg, E. Kozela, and R. Yirmiya, “Suicide in bipolar disorder patients is associated with hippocampal microglia activation and reduction of lymphocytes-activation gene 3 (LAG3) microglial checkpoint expression,” Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, vol. 110, pp. 185–194, May 2023. [CrossRef]

- G. Serra et al., “Suicidal behavior in juvenile bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder patients: Systematic review and meta-analysis,” J Affect Disord, vol. 311, pp. 572–581, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. Sher, “Testosterone and Suicidal Behavior in Bipolar Disorder,” Int J Environ Res Public Health, vol. 20, no. 3, Art. no. 3, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- F. Leichsenring, N. Heim, F. Leweke, C. Spitzer, C. Steinert, and O. F. Kernberg, “Borderline Personality Disorder: A Review,” JAMA, vol. 329, no. 8, Art. no. 8, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- E. R. Isaeva, D. M. Ryzhova, A. V. Stepanova, and I. N. Mitrev, “Assessment of Suicide Risk in Patients with Depressive Episodes Due to Affective Disorders and Borderline Personality Disorder: A Pilot Comparative Study,” Brain Sci, vol. 14, no. 5, Art. no. 5, May 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Paris, “Suicidality in Borderline Personality Disorder,” Medicina (Kaunas), vol. 55, no. 6, p. 223, May 2019. [CrossRef]

- Shahnovsky, A. Apter, and S. Barzilay, “The Association between Hyperactivity and Suicidal Behavior and Attempts among Children Referred from Emergency Departments,” European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, vol. 14, no. 10, Art. no. 10, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- P. Olsson, S. Wiktorsson, L. M. J. Strömsten, E. Salander Renberg, B. Runeson, and M. Waern, “Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults who present with self-harm: a comparative 6-month follow-up study,” BMC Psychiatry, vol. 22, no. 1, Art. no. 1, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. R. Taylor, J. M. Boden, and J. J. Rucklidge, “The relationship between ADHD symptomatology and self-harm, suicidal ideation, and suicidal behaviours in adults: a pilot study,” Atten Defic Hyperact Disord, vol. 6, no. 4, Art. no. 4, Dec. 2014. [CrossRef]

- B. S. da Silva, E. H. Grevet, L. C. F. Silva, J. K. N. Ramos, D. L. Rovaris, and C. H. D. Bau, “An overview on neurobiology and therapeutics of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder,” Discov Ment Health, vol. 3, no. 1, Art. no. 1, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. Fitzgerald, S. Dalsgaard, M. Nordentoft, and A. Erlangsen, “Suicidal behaviour among persons with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder,” Br J Psychiatry, pp. 1–6, Jun. 2019. [CrossRef]

- G. Di Salvo, C. Perotti, L. Filippo, C. Garrone, G. Rosso, and G. Maina, “Assessing suicidality in adult ADHD patients: prevalence and related factors,” Ann Gen Psychiatry, vol. 23, no. 1, Art. no. 1, Nov. 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. D. Oades, M. R. Dauvermann, B. G. Schimmelmann, M. J. Schwarz, and A.-M. Myint, “Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and glial integrity: S100B, cytokines and kynurenine metabolism - effects of medication,” Behav Brain Funct, vol. 6, p. 29, May 2010. [CrossRef]

- G. Natale et al., “Glial suppression and post-traumatic stress disorder: A cross-sectional study of 1,520 world trade center responders,” Brain Behav Immun Health, vol. 30, p. 100631, May 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. A. Gidzgier et al., “Improving care for SUD patients with complex trauma-relationships between childhood trauma, dissociation, and suicidal behavior in female patients with PTSD and SUD,” Front Psychiatry, vol. 13, p. 1047274, 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. McRae, L. Stoppelbein, S. O’Kelley, S. Smith, and P. Fite, “Pathways to Suicidal Behavior in Children and Adolescents: Examination of Child Maltreatment and Post-Traumatic Symptoms,” J Child Adolesc Trauma, vol. 15, no. 3, Art. no. 3, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Bansal, S. A. Codeluppi, and M. Banasr, “Astroglial Dysfunctions in Mood Disorders and Rodent Stress Models: Consequences on Behavior and Potential as Treatment Target,” International Journal of Molecular Sciences, vol. 25, no. 12, Art. no. 12, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Valenza et al., “Molecular signatures of astrocytes and microglia maladaptive responses to acute stress are rescued by a single administration of ketamine in a rodent model of PTSD,” Transl Psychiatry, vol. 14, no. 1, Art. no. 1, May 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. S. Kopacz, J. M. Currier, K. D. Drescher, and W. R. Pigeon, “Suicidal behavior and spiritual functioning in a sample of Veterans diagnosed with PTSD,” J Inj Violence Res, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 6–14, Jan. 2016. [CrossRef]

- D.-H. Lee et al., “Neuroinflammation in Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder,” Biomedicines, vol. 10, no. 5, p. 953, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. R. Dickerson, S. F. Murphy, M. J. Urban, Z. White, and P. J. VandeVord, “Chronic Anxiety- and Depression-Like Behaviors Are Associated With Glial-Driven Pathology Following Repeated Blast Induced Neurotrauma,” Front. Behav. Neurosci., vol. 15, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y. Tizabi, B. Getachew, S. R. Hauser, V. Tsytsarev, A. C. Manhães, and V. D. A. da Silva, “Role of Glial Cells in Neuronal Function, Mood Disorders, and Drug Addiction,” Brain Sciences, vol. 14, no. 6, Art. no. 6, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. C. Edwards et al., “Shared genetic and environmental etiology between substance use disorders and suicidal behavior,” Psychol Med, vol. 53, no. 6, Art. no. 6, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- B. Cabrera-Mendoza et al., “Candidate pharmacological treatments for substance use disorder and suicide identified by gene co-expression network-based drug repositioning,” Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet, vol. 186, no. 3, pp. 193–206, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- K. I. Martínez Martínez, Y. L. Ojeda Aguilar, J. Hernández Villafuerte, and M. E. Contreras-Peréz, “Depression and Suicidal Behavior Comorbidity in Patients Admitted to Substance-Use Residential Treatment in Aguascalientes, Mexico,” J Evid Based Soc Work (2019), vol. 20, no. 4, pp. 508–519, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- G. Gobbi et al., “Association of Cannabis Use in Adolescence and Risk of Depression, Anxiety, and Suicidality in Young Adulthood: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis,” JAMA Psychiatry, vol. 76, no. 4, Art. no. 4, Apr. 2019. [CrossRef]

- R. M. Moret, S. Sanz-Gómez, S. Gascón-Santos, and A. Alacreu-Crespo, “Exploring the Impact of Recreational Drugs on Suicidal Behavior: A Narrative Review,” Psychoactives, vol. 3, no. 3, Art. no. 3, Sep. 2024. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).