Submitted:

13 January 2025

Posted:

14 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Characteristics of the Sample at Baseline

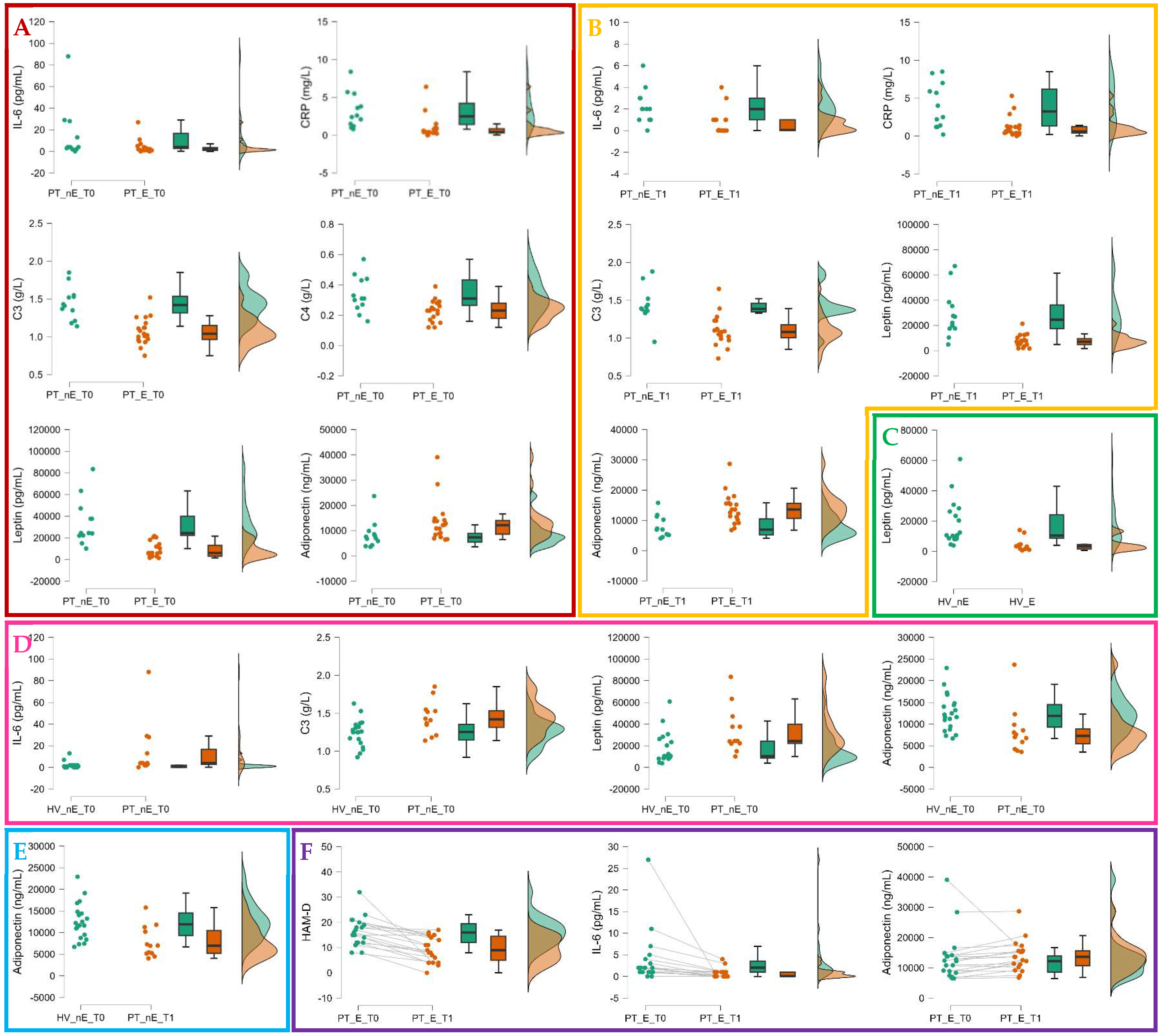

2.2. Group Comparisons at Baseline and Follow-Up

2.3. Paired Sample Comparisons Within Exposed and Nonexposed Patients’ Groups

2.4. The Impact of Green Exposure on Depressive Symptoms and IL-6 and Adiponectin Plasmatic Levels

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Participants and Study Design

4.2. Exposure to Green, Clinical, and Biological Markers Assessment

4.3. Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mokhtari, A.; Porte, B.; Belzeaux, R.; Etain, B.; Ibrahim, E.C.; Marie-Claire, C.; Lutz, P.-E.; Delahaye-Duriez, A. The Molecular Pathophysiology of Mood Disorders: From the Analysis of Single Molecular Layers to Multi-Omic Integration. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2022, 116, 110520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Organization, W.H. Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders: Global Health Estimates; World Health Organization, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Global Burden of Disease Study 2021 (GBD 2021) Burden and Strength of Evidence by Risk Factor 1990-2021 | GHDx. Available online: https://ghdx.healthdata.org/record/ihme-data/gbd-2021-burden-by-risk-1990-2021 (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- Kessler, R.C.; Berglund, P.; Demler, O.; Jin, R.; Koretz, D.; Merikangas, K.R.; Rush, A.J.; Walters, E.E.; Wang, P.S. National Comorbidity Survey Replication The Epidemiology of Major Depressive Disorder: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). JAMA 2003, 289, 3095–3105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- P, C.; H, N.; E, K.; Ch, V.; A, C.; Ta, F. A Network Meta-Analysis of the Effects of Psychotherapies, Pharmacotherapies and Their Combination in the Treatment of Adult Depression. World Psychiatry Off. J. World Psychiatr. Assoc. WPA 2020, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, L. da S.; Alencar, Á.P.; Nascimento Neto, P.J.; dos Santos, M. do S.V.; da Silva, C.G.L.; Pinheiro, S. de F.L.; Silveira, R.T.; Bianco, B.A.V.; Pinheiro, R.F.F.; de Lima, M.A.P.; et al. Risk Factors for Suicide in Bipolar Disorder: A Systematic Review. J. Affect. Disord. 2015, 170, 237–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- E, V.; M, B.; Tg, S.; Af, C.; T, S.; Jr, C.; K, G.; Kw, M.; I, G. Bipolar Disorders. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primer 2018, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.N.; Black, D.W. Bipolar Disorder and Suicide: A Review. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2020, 22, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, R.; Chen, Y.; Li, L.; Chen, J.; Guo, Y.; Bian, Z.; Lv, J.; Yu, C.; Xie, X.; Huang, D.; et al. Factors Associated with Suicide Risk among Chinese Adults: A Prospective Cohort Study of 0.5 Million Individuals. PLoS Med. 2021, 18, e1003545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crisafulli, C.; Fabbri, C.; Porcelli, S.; Drago, A.; Spina, E.; De Ronchi, D.; Serretti, A. Pharmacogenetics of Antidepressants. Front. Pharmacol. 2011, 2, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rj, B.; Gh, V.; L, T. Bipolar Depression: A Major Unsolved Challenge. Int. J. Bipolar Disord. 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, M.H.; Rush, A.J.; Wisniewski, S.R.; Nierenberg, A.A.; Warden, D.; Ritz, L.; Norquist, G.; Howland, R.H.; Lebowitz, B.; McGrath, P.J.; et al. Evaluation of Outcomes with Citalopram for Depression Using Measurement-Based Care in STAR*D: Implications for Clinical Practice. Am. J. Psychiatry 2006, 163, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Targum, S.D.; Schappi, J.; Koutsouris, A.; Bhaumik, R.; Rapaport, M.H.; Rasgon, N.; Rasenick, M.M. A Novel Peripheral Biomarker for Depression and Antidepressant Response. Mol. Psychiatry 2022, 27, 1640–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malhi, G.S.; Mann, J.J. Depression. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2018, 392, 2299–2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsolini, L.; Pompili, S.; Tempia Valenta, S.; Salvi, V.; Volpe, U. C-Reactive Protein as a Biomarker for Major Depressive Disorder? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maes, M.; Yirmyia, R.; Noraberg, J.; Brene, S.; Hibbeln, J.; Perini, G.; Kubera, M.; Bob, P.; Lerer, B.; Maj, M. The Inflammatory & Neurodegenerative (I&ND) Hypothesis of Depression: Leads for Future Research and New Drug Developments in Depression. Metab. Brain Dis. 2009, 24, 27–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller, J.; Gomez, R.; Williams, G.; Lembke, A.; Lazzeroni, L.; Murphy, G.M.; Schatzberg, A.F. HPA Axis in Major Depression: Cortisol, Clinical Symptomatology and Genetic Variation Predict Cognition. Mol. Psychiatry 2017, 22, 527–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czarny, P.; Wigner, P.; Galecki, P.; Sliwinski, T. The Interplay between Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, DNA Damage, DNA Repair and Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Depression. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2018, 80, 309–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gałecki, P.; Talarowska, M. Neurodevelopmental Theory of Depression. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2018, 80, 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uchida, S.; Yamagata, H.; Seki, T.; Watanabe, Y. Epigenetic Mechanisms of Major Depression: Targeting Neuronal Plasticity. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2018, 72, 212–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gałecki, P.; Talarowska, M. Inflammatory Theory of Depression. Psychiatr. Pol. 2018, 52, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldsmith, D.R.; Rapaport, M.H.; Miller, B.J. A Meta-Analysis of Blood Cytokine Network Alterations in Psychiatric Patients: Comparisons between Schizophrenia, Bipolar Disorder and Depression. Mol. Psychiatry 2016, 21, 1696–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nobis, A.; Zalewski, D.; Waszkiewicz, N. Peripheral Markers of Depression. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osimo, E.F.; Pillinger, T.; Rodriguez, I.M.; Khandaker, G.M.; Pariante, C.M.; Howes, O.D. Inflammatory Markers in Depression: A Meta-Analysis of Mean Differences and Variability in 5,166 Patients and 5,083 Controls. Brain. Behav. Immun. 2020, 87, 901–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiksdal, A.; Hanlin, L.; Kuras, Y.; Gianferante, D.; Chen, X.; Thoma, M.V.; Rohleder, N. Associations Between Symptoms of Depression and Anxiety and Cortisol Responses to and Recovery from Acute Stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2019, 102, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beurel, E.; Toups, M.; Nemeroff, C.B. The Bidirectional Relationship of Depression and Inflammation: Double Trouble. Neuron 2020, 107, 234–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnadas, R.; Cavanagh, J. Depression: An Inflammatory Illness? J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2012, 83, 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McEwen, B.S. Mood Disorders and Allostatic Load. Biol. Psychiatry 2003, 54, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Protection and Damage from Acute and Chronic Stress: Allostasis and Allostatic Overload and Relevance to the Pathophysiology of Psychiatric Disorders - PubMed. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15677391/ (accessed on 6 August 2024).

- Sapolsky, R.M.; Romero, L.M.; Munck, A.U. How Do Glucocorticoids Influence Stress Responses? Integrating Permissive, Suppressive, Stimulatory, and Preparative Actions. Endocr. Rev. 2000, 21, 55–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du Clos, T.W. Function of C-Reactive Protein. Ann. Med. 2000, 32, 274–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zipfel, P.F.; Skerka, C. Complement Regulators and Inhibitory Proteins. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2009, 9, 729–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Fang, Z.; Lin, L.; Xu, H.; Huang, Q.; Zhang, H. Plasma Complement C3 and C3a Are Increased in Major Depressive Disorder Independent of Childhood Trauma. BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillai, A.; Bruno, D.; Nierenberg, J.; Pandya, C.; Feng, T.; Reichert, C.; Ramos-Cejudo, J.; Osorio, R.; Zetterberg, H.; Blennow, K.; et al. Complement Component 3 Levels in the Cerebrospinal Fluid of Cognitively Intact Elderly Individuals with Major Depressive Disorder. Biomark. Neuropsychiatry 2019, 1, 100007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, C.; Dinan, T.; Leonard, B.E. Changes in Immunoglobulin, Complement and Acute Phase Protein Levels in the Depressed Patients and Normal Controls. J. Affect. Disord. 1994, 30, 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shatri, H.; Purnamandala; Hidayat, R.; Sinto, R.; Widhani, A.; Putranto, R.; Purnamasari, R.D.; Ginanjar, E.; Jasirwan, C.O.M. The Correlation of Anxiety and Depression with C3 and C4 Levels and Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Activity. BMC Psychiatry 2023, 23, 785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, L.; Yang, X.; Ni, P.; Wang, Y.; Li, T.; Ma, X. Plasma Complement Component 4 Increases in Patients with Major Depressive Disorder. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2017, 14, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, J.J. Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB) and the Complement Landscape. Mol. Immunol. 2018, 102, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose-John, S. Interleukin-6 Signalling in Health and Disease. F1000Research 2020, 9, F1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, S.; Bansal, Y.; Kumar, R.; Bansal, G. A Panoramic Review of IL-6: Structure, Pathophysiological Roles and Inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2020, 28, 115327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ting, E.Y.-C.; Yang, A.C.; Tsai, S.-J. Role of Interleukin-6 in Depressive Disorder. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solmi, M.; Suresh Sharma, M.; Osimo, E.F.; Fornaro, M.; Bortolato, B.; Croatto, G.; Miola, A.; Vieta, E.; Pariante, C.M.; Smith, L.; et al. Peripheral Levels of C-Reactive Protein, Tumor Necrosis Factor-α, Interleukin-6, and Interleukin-1β across the Mood Spectrum in Bipolar Disorder: A Meta-Analysis of Mean Differences and Variability. Brain. Behav. Immun. 2021, 97, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuong, E.; Nothling, J.; Lombard, C.; Jewkes, R.; Peer, N.; Abrahams, N.; Seedat, S. Peripheral Adiponectin Levels in Anxiety, Mood, Trauma- and Stressor-Related Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 260, 372–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scotece, M.; Conde, J.; López, V.; Lago, F.; Pino, J.; Gómez-Reino, J.J.; Gualillo, O. Adiponectin and Leptin: New Targets in Inflammation. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2014, 114, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz-Filho, G.; Mastronardi, C.; Franco, C.B.; Wang, K.B.; Wong, M.-L.; Licinio, J. Leptin: Molecular Mechanisms, Systemic pro-Inflammatory Effects, and Clinical Implications. Arq. Bras. Endocrinol. Metabol. 2012, 56, 597–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Pérez, A.; Sánchez-Jiménez, F.; Vilariño-García, T.; Sánchez-Margalet, V. Role of Leptin in Inflammation and Vice Versa. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouchi, N.; Walsh, K. Adiponectin as an Anti-Inflammatory Factor. Clin. Chim. Acta Int. J. Clin. Chem. 2007, 380, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.M.; Doss, H.M.; Kim, K.S. Multifaceted Physiological Roles of Adiponectin in Inflammation and Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, K.; Prins, J.; Venkatesh, B. Clinical Review: Adiponectin Biology and Its Role in Inflammation and Critical Illness. Crit. Care 2011, 15, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leal, G.; Bramham, C.R.; Duarte, C.B. BDNF and Hippocampal Synaptic Plasticity. Vitam. Horm. 2017, 104, 153–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowiański, P.; Lietzau, G.; Czuba, E.; Waśkow, M.; Steliga, A.; Moryś, J. BDNF: A Key Factor with Multipotent Impact on Brain Signaling and Synaptic Plasticity. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2018, 38, 579–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, G.A.; O’Connor, J.C. Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor and Inflammation in Depression: Pathogenic Partners in Crime? World J. Psychiatry 2022, 12, 77–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Nie, Z.; Shu, H.; Kuang, Y.; Chen, X.; Cheng, J.; Yu, S.; Liu, H. The Role of BDNF on Neural Plasticity in Depression. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correia, A.S.; Cardoso, A.; Vale, N. BDNF Unveiled: Exploring Its Role in Major Depression Disorder Serotonergic Imbalance and Associated Stress Conditions. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calabrese, F.; Rossetti, A.C.; Racagni, G.; Gass, P.; Riva, M.A.; Molteni, R. Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor: A Bridge between Inflammation and Neuroplasticity. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banwell, N.; Michel, S.; Senn, N. Greenspaces and Health: Scoping Review of Studies in Europe. Public Health Rev. 2024, 45, 1606863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratman, G.N.; Anderson, C.B.; Berman, M.G.; Cochran, B.; de Vries, S.; Flanders, J.; Folke, C.; Frumkin, H.; Gross, J.J.; Hartig, T.; et al. Nature and Mental Health: An Ecosystem Service Perspective. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaax0903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reklaitiene, R.; Grazuleviciene, R.; Dedele, A.; Virviciute, D.; Vensloviene, J.; Tamosiunas, A.; Baceviciene, M.; Luksiene, D.; Sapranaviciute-Zabazlajeva, L.; Radisauskas, R.; et al. The Relationship of Green Space, Depressive Symptoms and Perceived General Health in Urban Population. Scand. J. Public Health 2014, 42, 669–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, T.; Song, B.; Cho, K.S.; Lee, I.-S. Therapeutic Potential of Volatile Terpenes and Terpenoids from Forests for Inflammatory Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzales-Inca, C.; Pentti, J.; Stenholm, S.; Suominen, S.; Vahtera, J.; Käyhkö, N. Residential Greenness and Risks of Depression: Longitudinal Associations with Different Greenness Indicators and Spatial Scales in a Finnish Population Cohort. Health Place 2022, 74, 102760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, I.; Reece, R.; Sinnett, D.; Martin, F.; Hayward, R. Exploring the Role of Exposure to Green and Blue Spaces in Preventing Anxiety and Depression among Young People Aged 14-24 Years Living in Urban Settings: A Systematic Review and Conceptual Framework. Environ. Res. 2022, 214, 114081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beil, K.; Hanes, D. The Influence of Urban Natural and Built Environments on Physiological and Psychological Measures of Stress--a Pilot Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2013, 10, 1250–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, M.; Martinez, J.H.; Young, D.; Chelminski, I.; Dalrymple, K. Severity Classification on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. J. Affect. Disord. 2013, 150, 384–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jimenez, M.P.; DeVille, N.V.; Elliott, E.G.; Schiff, J.E.; Wilt, G.E.; Hart, J.E.; James, P. Associations between Nature Exposure and Health: A Review of the Evidence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 4790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kellert, S.R.; Wilson, E.O. The Biophilia Hypothesis; Island Press, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Lederbogen, F.; Kirsch, P.; Haddad, L.; Streit, F.; Tost, H.; Schuch, P.; Wüst, S.; Pruessner, J.C.; Rietschel, M.; Deuschle, M.; et al. City Living and Urban Upbringing Affect Neural Social Stress Processing in Humans. Nature 2011, 474, 498–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Miao, L.; Turner, D.; DeRubeis, R. Urbanicity and Depression: A Global Meta-Analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 340, 299–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Liu, N.; Polemiti, E.; Garcia-Mondragon, L.; Tang, J.; Liu, X.; Lett, T.; Yu, L.; Nöthen, M.M.; Feng, J.; et al. Effects of Urban Living Environments on Mental Health in Adults. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 1456–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, K. Urbanization and Mental Health. Ind. Psychiatry J. 2009, 18, 75–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecic-Tosevski, D. Is Urban Living Good for Mental Health? Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2019, 32, 204–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Chen, X.; Cui, H.; Ma, Y.; Gao, N.; Li, X.; Meng, X.; Lin, H.; Abudou, H.; Guo, L.; et al. Green Space Exposure on Depression and Anxiety Outcomes: A Meta-Analysis. Environ. Res. 2023, 231, 116303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, M.M.; Jones, R.; Tocchini, K. Shinrin-Yoku (Forest Bathing) and Nature Therapy: A State-of-the-Art Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2017, 14, 851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.Q. Shinrin-Yoku: The Art and Science of Forest Bathing. Penguin UK, 2018; ISBN 978-0-241-34696-9. [Google Scholar]

- Forest Medicine – Nova Science Publishers.

- Bj, P.; Y, T.; T, K.; T, K.; Y, M. The Physiological Effects of Shinrin-Yoku (Taking in the Forest Atmosphere or Forest Bathing): Evidence from Field Experiments in 24 Forests across Japan. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2010, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.-H.; Jeong, G.-W.; Baek, H.-S.; Kim, G.-W.; Sundaram, T.; Kang, H.-K.; Lee, S.-W.; Kim, H.-J.; Song, J.-K. Human Brain Activation in Response to Visual Stimulation with Rural and Urban Scenery Pictures: A Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Study. Sci. Total Environ. 2010, 408, 2600–2607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.-W.; Jeong, G.-W.; Kim, T.-H.; Baek, H.-S.; Oh, S.-K.; Kang, H.-K.; Lee, S.-G.; Kim, Y.S.; Song, J.-K. Functional Neuroanatomy Associated with Natural and Urban Scenic Views in the Human Brain: 3.0T Functional MR Imaging. Korean J. Radiol. 2010, 11, 507–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, H.; Song, C.; Miyazaki, Y. Physiological Benefits of Viewing Nature: A Systematic Review of Indoor Experiments. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2019, 16, 4739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikei, H.; Komatsu, M.; Song, C.; Himoro, E.; Miyazaki, Y. The Physiological and Psychological Relaxing Effects of Viewing Rose Flowers in Office Workers. J. Physiol. Anthropol. 2014, 33, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levandovski, R.; Pfaffenseller, B.; Carissimi, A.; Gama, C.S.; Hidalgo, M.P.L. The Effect of Sunlight Exposure on Interleukin-6 Levels in Depressive and Non-Depressive Subjects. BMC Psychiatry 2013, 13, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penckofer, S.; Kouba, J.; Byrn, M.; Ferrans, C.E. Vitamin D and Depression: Where Is All the Sunshine? Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2010, 31, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedblom, M.; Gunnarsson, B.; Iravani, B.; Knez, I.; Schaefer, M.; Thorsson, P.; Lundström, J.N. Reduction of Physiological Stress by Urban Green Space in a Multisensory Virtual Experiment. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 10113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, K.S.; Lim, Y.-R.; Lee, K.; Lee, J.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, I.-S. Terpenes from Forests and Human Health. Toxicol. Res. 2017, 33, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soudry, Y.; Lemogne, C.; Malinvaud, D.; Consoli, S.-M.; Bonfils, P. Olfactory System and Emotion: Common Substrates. Eur. Ann. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Dis. 2011, 128, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemke, H.; Probst, S.; Warneke, A.; Waltemate, L.; Winter, A.; Thiel, K.; Meinert, S.; Enneking, V.; Breuer, F.; Klug, M.; et al. The Course of Disease in Major Depressive Disorder Is Associated With Altered Activity of the Limbic System During Negative Emotion Processing. Biol. Psychiatry Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging 2022, 7, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, É.R.Q.; Maia, J.G.S.; Fontes-Júnior, E.A.; Maia, C. do S.F. Linalool as a Therapeutic and Medicinal Tool in Depression Treatment: A Review. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2022, 20, 1073–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, H.; Kashiwadani, H.; Kanmura, Y.; Kuwaki, T. Linalool Odor-Induced Anxiolytic Effects in Mice. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milanos, S.; Elsharif, S.A.; Janzen, D.; Buettner, A.; Villmann, C. Metabolic Products of Linalool and Modulation of GABAA Receptors. Front. Chem. 2017, 5, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machado, K. da C.; Islam, M.T.; Ali, E.S.; Rouf, R.; Uddin, S.J.; Dev, S.; Shilpi, J.A.; Shill, M.C.; Reza, H.M.; Das, A.K.; et al. A Systematic Review on the Neuroprotective Perspectives of Beta-Caryophyllene. Phytother. Res. PTR 2018, 32, 2376–2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scandiffio, R.; Geddo, F.; Cottone, E.; Querio, G.; Antoniotti, S.; Gallo, M.P.; Maffei, M.E.; Bovolin, P. Protective Effects of (E)-β-Caryophyllene (BCP) in Chronic Inflammation. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, J.; Fan, M.; An, C.; Ni, F.; Huang, W.; Luo, J. A Narrative Review of Molecular Mechanism and Therapeutic Effect of Cannabidiol (CBD). Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2022, 130, 439–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohrer, J.; Lupo, N.; Bernkop-Schnürch, A. Advanced Formulations for Intranasal Delivery of Biologics. Int. J. Pharm. 2018, 553, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller, L.-A.; Merkel, O.; Popp, A. Intranasal Drug Delivery: Opportunities and Toxicologic Challenges during Drug Development. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2022, 12, 735–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felger, J.C.; Lotrich, F.E. Inflammatory Cytokines in Depression: Neurobiological Mechanisms and Therapeutic Implications. Neuroscience 2013, 246, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, S.W.; Kim, Y.K. Neuroinflammation and Cytokine Abnormality in Major Depression: Cause or Consequence in That Illness? World J. Psychiatry 2016, 6, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamers, F.; Milaneschi, Y.; Smit, J.H.; Schoevers, R.A.; Wittenberg, G.; Penninx, B.W.J.H. Longitudinal Association Between Depression and Inflammatory Markers: Results From the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety. Biol. Psychiatry 2019, 85, 829–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamers, F.; Milaneschi, Y.; de Jonge, P.; Giltay, E.J.; Penninx, B.W.J.H. Metabolic and Inflammatory Markers: Associations with Individual Depressive Symptoms. Psychol. Med. 2018, 48, 1102–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ting, E.Y.-C.; Yang, A.C.; Tsai, S.-J. Role of Interleukin-6 in Depressive Disorder. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erta, M.; Quintana, A.; Hidalgo, J. Interleukin-6, a Major Cytokine in the Central Nervous System. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2012, 8, 1254–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kummer, K.K.; Zeidler, M.; Kalpachidou, T.; Kress, M. Role of IL-6 in the Regulation of Neuronal Development, Survival and Function. Cytokine 2021, 144, 155582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ting, E.Y.-C.; Yang, A.C.; Tsai, S.-J. Role of Interleukin-6 in Depressive Disorder. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daray, F.M.; Grendas, L.N.; Arena, Á.R.; Tifner, V.; Álvarez Casiani, R.I.; Olaviaga, A.; Chiapella, L.C.; Vázquez, G.; Penna, M.B.; Hunter, F.; et al. Decoding the Inflammatory Signature of the Major Depressive Episode: Insights from Peripheral Immunophenotyping in Active and Remitted Condition, a Case–Control Study. Transl. Psychiatry 2024, 14, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Prado-Audelo, M.L.; Cortés, H.; Caballero-Florán, I.H.; González-Torres, M.; Escutia-Guadarrama, L.; Bernal-Chávez, S.A.; Giraldo-Gomez, D.M.; Magaña, J.J.; Leyva-Gómez, G. Therapeutic Applications of Terpenes on Inflammatory Diseases. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 704197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araruna, M.E.; Serafim, C.; Alves Júnior, E.; Hiruma-Lima, C.; Diniz, M.; Batista, L. Intestinal Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Terpenes in Experimental Models (2010-2020): A Review. Mol. Basel Switz. 2020, 25, 5430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de las Heras, B.; Hortelano, S. Molecular Basis of the Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Terpenoids. Inflamm. Allergy Drug Targets 2009, 8, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruani, J.; Geoffroy, P.A. Multi-Level Processes and Retina-Brain Pathways of Photic Regulation of Mood. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Guo, M.; Zhang, D.; Cheng, S.-Y.; Liu, M.; Ding, J.; Scherer, P.E.; Liu, F.; Lu, X.-Y. Adiponectin Is Critical in Determining Susceptibility to Depressive Behaviors and Has Antidepressant-like Activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 12248–12253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herder, C.; Schmitt, A.; Budden, F.; Reimer, A.; Kulzer, B.; Roden, M.; Haak, T.; Hermanns, N. Longitudinal Associations between Biomarkers of Inflammation and Changes in Depressive Symptoms in Patients with Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2018, 91, 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolas, S.; Veyssière, J.; Gandin, C.; Zsürger, N.; Pietri, M.; Heurteaux, C.; Glaichenhaus, N.; Petit-Paitel, A.; Chabry, J. Neurogenesis-Independent Antidepressant-like Effects of Enriched Environment Is Dependent on Adiponectin. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2015, 57, 72–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, M. A Rating Scale for Depression. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1960, 23, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benjamini, Y.; Hochberg, Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Methodol. 1995, 57, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total sample of patients at t0 (n=53) |

Completers patients at t0 (n=31) | Drop-out patients (n=22) | Completers vs drop-out patients at t0 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| p-FDR | ||||

| Sociodemographic variables | ||||

| Age, years | 48.0 [31.0; 56.0] | 47.0 [35.0; 59.5] | 49.5 [30.3; 55.0] | .848 |

| Sex, female | 36 (68%) | 22 (71%) | 14 (64%) | .464 |

| Education, years | 13.0 [13.0; 17.0] | 13.0 [13.0; 16.0] | 13.0 [11.5; 16.0] | .424 |

| Clinical variables | ||||

| Duration of illness, years | 6 [2; 14] | 5 [2; 13] | 8 [3; 14] | .718 |

| Numbers of hospitalization | 1 [1; 3] | 1 [1; 2] | 1 [1; 3] | .411 |

| HAM-D | 18 [13; 20] | 17 [12; 20] | 18 [16; 21] | .424 |

| Biological markers | ||||

| IL-6, pg/mL | 2.0 [1.0; 4.0] | 2.0 [1.0; 4.5] | 2.0 [1.0; 2.0] | .411 |

| CRP, mg/L | 0.9 [0.4; 2.1] | 0.9 [0.4; 2.5] | 0.8 [0.4; 1.6] | .810 |

| C3, g/L | 1.18 [1.02; 1.41] | 1.18 [1.02; 1.39] | 1.19 [1.04; 1.41] | .898 |

| C4, g/L | 0.29 [0.23; 0.35] | 0.26 [0.21; 0.31] | 0.32 [0.28; 0.41] | .150 |

| Cortisol, mcg/L | 109 [79; 153] | 105 [79; 127] | 136 [92; 158] | .424 |

| Leptin, pg/L | 10,423 [5,751; 24,111] | 14,202 [5,641; 23,196] | 9,349 [7,124; 22,372] | .999 |

| Adiponectin, ng/L | 8,575 [6,568; 12,303] | 9,087 [6,969; 13,283] | 7,367 [5,999; 11,246] | .411 |

| BDNF, pg/mL | 461.7 [305.5; 823.9] | 402.5 [273.2; 755.5] | 635.4 [427.4; 912.1] | .411 |

| PT_E_t0 (n=19) |

PT_nE_t0 (n=12) |

PT_E_t1 (n=19) |

PT_nE_t1 (n=12) |

HV_E (n=10) |

HV_nE (n=21) |

PT_E_t0 vs PT_nE_t0 |

PT_E_t1 vs PT_nE_t1 |

HV_E vs HV_nE |

HV_E vs PT_E_t0 |

HV_E vs PT_E_t1 |

HV_nE vs PT_nE_t0 |

HV_nE vs PT_nE_t1 |

PT_E t0 vs t1 |

PT_nE t0 vs t1 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p-FDR | p-FDR | p-FDR | p-FDR | p-FDR | p-FDR | p-FDR | p-FDR | p-FDR | |||||||

| Sociodemographic variables | |||||||||||||||

| Age, years | 46.0 [28.0; 50.0] | 54.5 [38.0; 60.5] | - | - | 31.0 [25.0; 33.0] | 40.5 [31.0; 57.0] | .324 | - | .215 | .243 | - | .072 | - | - | - |

| Sex, female | 14 (74%) | 8 (67%) | - | - | 6 (60%) | 15 (71%) | .839 | - | .832 | .966 | - | .812 | - | - | - |

| Education, years | 13.0 [13.0; 17.0] | 13.0 [11.7; 13.7] | - | - | 18.0 [13.0; 18.0] | 13.0 [13.0; 18.0] | .324 | - | .577 | .628 | - | .048 | - | - | - |

| Biological markers | |||||||||||||||

| IL-6, pg/mL | 2.00 [1.00; 3.5] | 4.00 [2.75; 16.75] | 0.05 [0.01; 1.00] | 2.00 [1.00; 3.00] | 0.60 [0.01; 1.60] |

1.00 [0.01; 1.75] | .048 | .005 | .577 | .243 | .966 | .004 | .177 | .002 | .081 |

| CRP, mg/L | 0.4 [0.3; 0.8] | 2.5 [1.4; 4.2] | 0.6 [0.4; 1.2] | 3.2 [1.3; 6.2] | 0.5 [0.3; 1.8] | 0.9 [0.8; 1.5] | .002 | .005 | .324 | .656 | 1.00 | .065 | .094 | .542 | .906 |

| C3, g/L | 1.04 [0.96; 1.15] | 1.42 [1.31; 1.53] | 1.08 [1.00; 1.17] | 1.38 [1.35; 1.39] |

1.09 [1.02; 1.11] |

1.28 [1.16; 1.36] |

.002 | .002 | .075 | .735 | 1.00 | .048 | .052 | .542 | .906 |

| C4, g/L | 0.23 [0.18; 0.28] |

0.31 [0.26; 0.43] |

0.23 [0.18; 0.27] |

0.32 [0.22; 0.36] |

0.20 [0.18; 0.24] |

0.27 [0.22; 0.33] |

.021 | .095 | .215 | .735 | 1.00 | .228 | .431 | .777 | .290 |

| Cortisol, mcg/L | 105 [79; 129] |

110 [71; 125] |

136 [96; 168] |

97 [92; 133] |

125 [112; 144] |

100 [93; 112] |

.855 | .070 | .710 | .628 | .966 | .530 | .356 | .121 | .906 |

| Leptin, pg/L | 6,095 [3,112; 13,061] |

24,444 [22,211; 40,018] |

7,099 [4,871; 9,505] |

24,506 [17,572; 36,166] |

3,192 [1,525; 4,462] |

9,925 [8,554; 26,281] |

.002 | .002 | .004 | .243 | .248 | .017 | .094 | .551 | .290 |

| Adiponectin, ng/L | 12,182 [8,599; 13,960] |

7,309 [5,470; 13,503] |

13,599 [10,650; 15,642] |

6,968 [5,216; 10,479] |

13,141 [10,216; 17,288] |

11,626 [9,314; 14,832] |

.026 | .003 | .722 | .628 | 1.00 | .017 | .016 | .018 | .853 |

| BDNF, pg/mL | 396.7 [268.3; 591.2] |

416.8 [327.3; 1,032.4] |

535.0 [278.9; 1,058.7] |

772.6 [516.7; 1,026.4] |

429.1 [227.4; 712.0] |

234.8 [192.5; 561.7] |

.750 | .372 | .950 | .735 | .966 | .567 | .177 | .110 | .367 |

| Depressive symptoms | |||||||||||||||

| HAM-D, total score | 16.0 [12.0; 19.5] |

18.5 [11.5; 20.0] |

9.0 [5.0; 14.5] |

13.5 [8.7; 16.5] |

- | - | .855 | .188 | - | - | - | - | - | .002 | .855 |

| Regressor | B | 95%CI of B | p | Outcomes at follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposure to green environments between baseline and follow-up | -3.850 | -7.627; -.028 | .048 | Depressive symptoms (HAMD, total score) |

| -1.420 | -2.503; -.338 | .012 | IL-6, pg/mL | |

| 3,795 | 1,022; 6,567 | .009 | Adiponectin, ng/L |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).