Submitted:

13 January 2025

Posted:

14 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

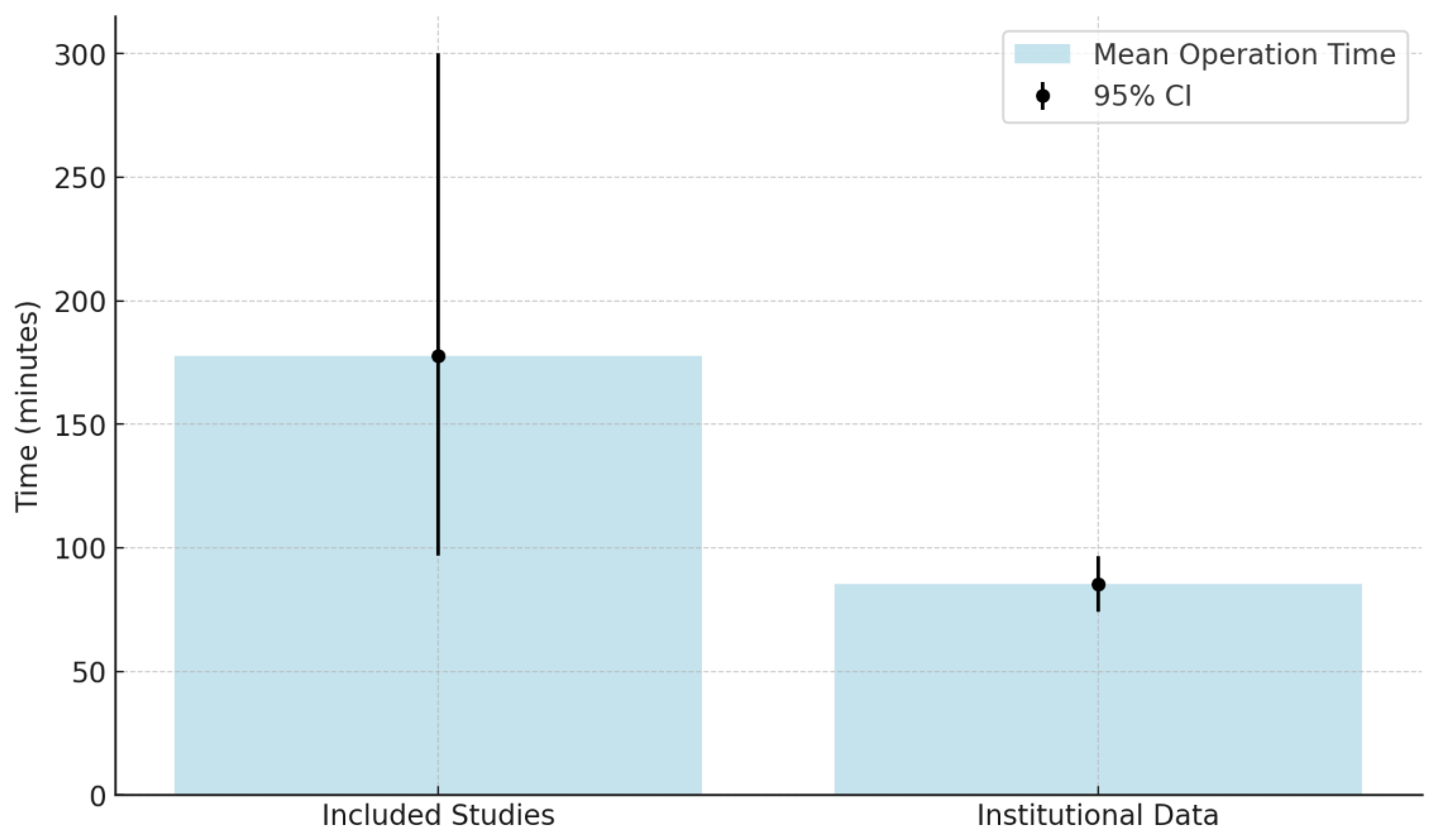

Abstract

Background: Ura-chal pathologies, while rare, pose a malignant transformation risk. RAUEPC is a mini-mally invasive technique with potential benefits, yet evidence remains limited. Methods: A systematic review was conducted in PubMed, Scopus, the Cochrane Library, and Sci-enceDirect (last search: 1 November 2024). Inclusion criteria: studies on RAUEPC for ura-chal pathologies. Exclusion criteria: non-robotic approaches or incomplete data. Risk of bias was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for cohort studies and the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for case reports. Descriptive statistics summarized continuous data (means, medians, 95% CIs), and chi-square tests analyzed associations between categori-cal variables. Heterogeneity analysis was infeasible, necessitating narrative synthesis. In-stitutional data (3 cases, 2021–2024) were included for comparison. Results: Forty-four studies (n = 145) met inclusion criteria. Benign lesions constituted 66.2% (95% CI: 59.1–73.3%) and malignant lesions 33.8% (95% CI: 26.7–40.9%). Mean operative time was 177.8 min (95% CI: 96.8–300), blood loss 83.3 mL (95% CI: 50–171), and hospital stay 3.9 days (95% CI: 1–10.9). Complications occurred in 33.3%. Institutional results showed a mean operative time of 85.3 min, blood loss of 216.7 mL, and no recurrences at 10.7 months’ fol-low-up. Discussion: RAUEPC appears to be a feasible and safe approach, showing prom-ising short-term outcomes. Associations between symptoms and diagnostic methods sug-gest its utility. Limitations include small sample sizes and retrospective designs. Registra-tion: PROSPERO: CRD42024597785. Funding: No external funding.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Epidemiology of Urachal Pathology and Clinical Manifestation

1.2. Embryogenesis of the Urachus and Risk of Malignant Transformation

1.3. Staging of Urachal Cancer

1.4. Diagnostic Imaging

1.5. Treatment Modalities, Current Approaches, and Challenges in Management

1.6. Novelty and Contribution of This Study

2. Aim

3. Material and Methods

3.1. Search Strategy

- (“robotic” OR “robot-assisted” OR “robot-assisted laparoscopic”) AND (“urachal” OR “urachus” OR “urachal anomalies” OR “urachal cyst” OR “urachal diverticulum” OR “urachal adenoma” OR “urachal adenocarcinoma”) AND (“removal” OR “excision” OR “partial cystectomy”)

- (“robotic” OR “robot-assisted” OR “robot-assisted laparoscopic”) AND (“urachal” OR “urachus”) AND (“removal” OR “excision” OR “partial cystectomy”)

- (“robotic” OR “robot-assisted” OR “robot-assisted laparoscopic”) AND (“urachal anomalies” OR “urachal cyst”) AND (“removal” OR “excision” OR “partial cystectomy”)

- (“robotic” OR “robot-assisted” OR “robot-assisted laparoscopic”) AND (“urachal diverticulum” OR “urachal adenoma” OR “urachal adenocarcinoma”) AND (“removal” OR “excision” OR “partial cystectomy”)

3.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- Reason for Surgery

- Symptoms

- Imaging Method

- Cystoscopy and/or preoperative TURBT results

- Staging

- Umbilicus Removal

- Lymphadenectomy

- Complications

- Hospital Stay

- Histopathological Findings

- Robotic System

- Total Operation and Console Time

- Blood Loss

- Patient Characteristics

- Follow-Up

- Adjuvant Therapy

3.3. Screening Process and Data Extraction

3.4. Quality Assessment and Risk of Bias (RoB)

3.5. Heterogeneity Tests

3.6. Statistical Analysis and Data Synthesis

3.7. Ethical Considerations

4. Results

4.1. Search Results

4.2. Risk of Bias Assessment and Quality Evaluation

4.3. Overview

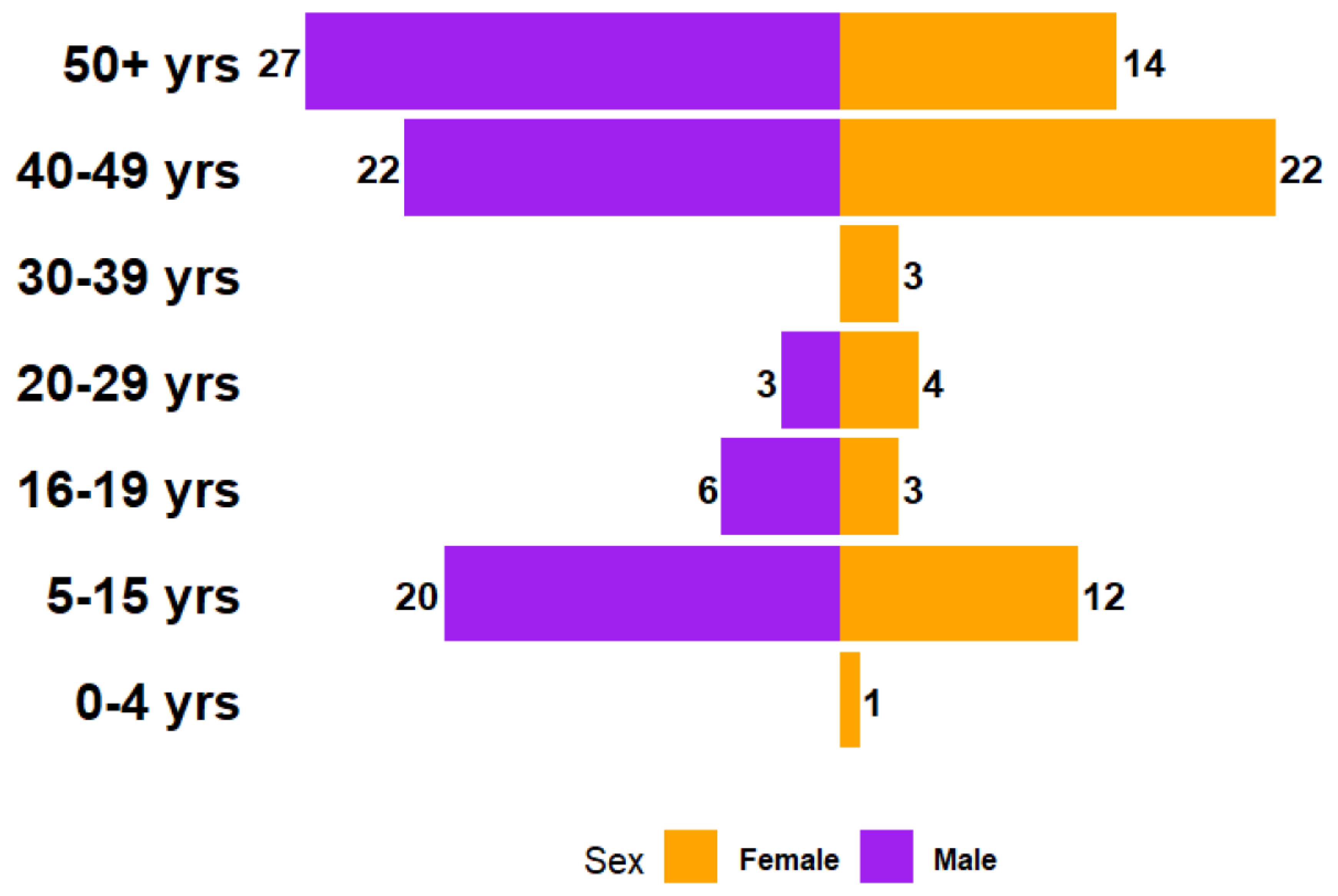

4.3.1. Sex and Age Distribution

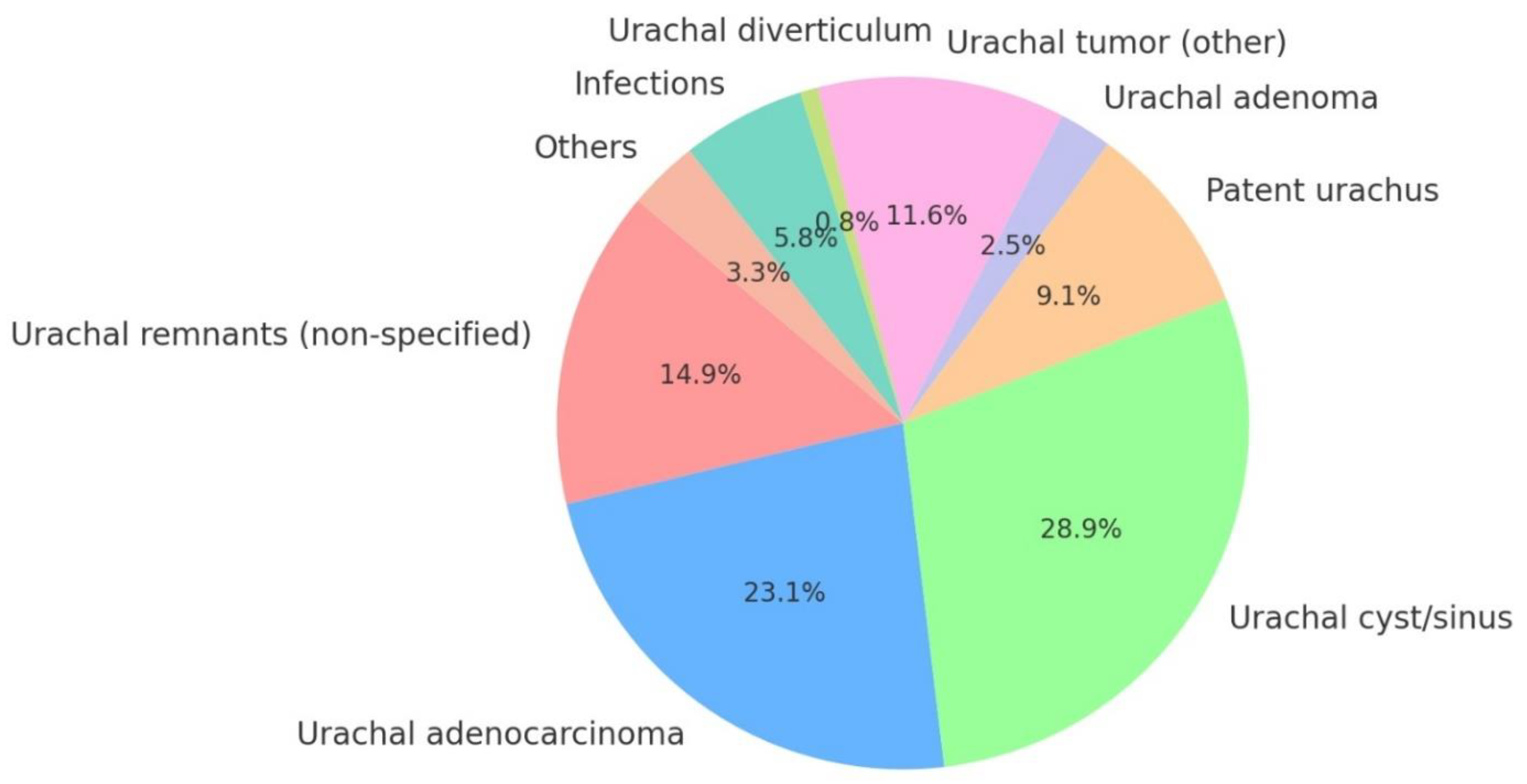

4.3.2. Reasons for Surgery

4.3.3. Symptoms

4.3.4. Imaging Methods

4.3.5. Cystoscopy Results

4.4. Evidence Synthesis

4.4.1. Feasibility

4.4.2. Efficacy

4.4.3. Safety

4.4.4. Short-Term Clinical Outcomes

4.4.5. Long-Term Follow-Up Outcomes

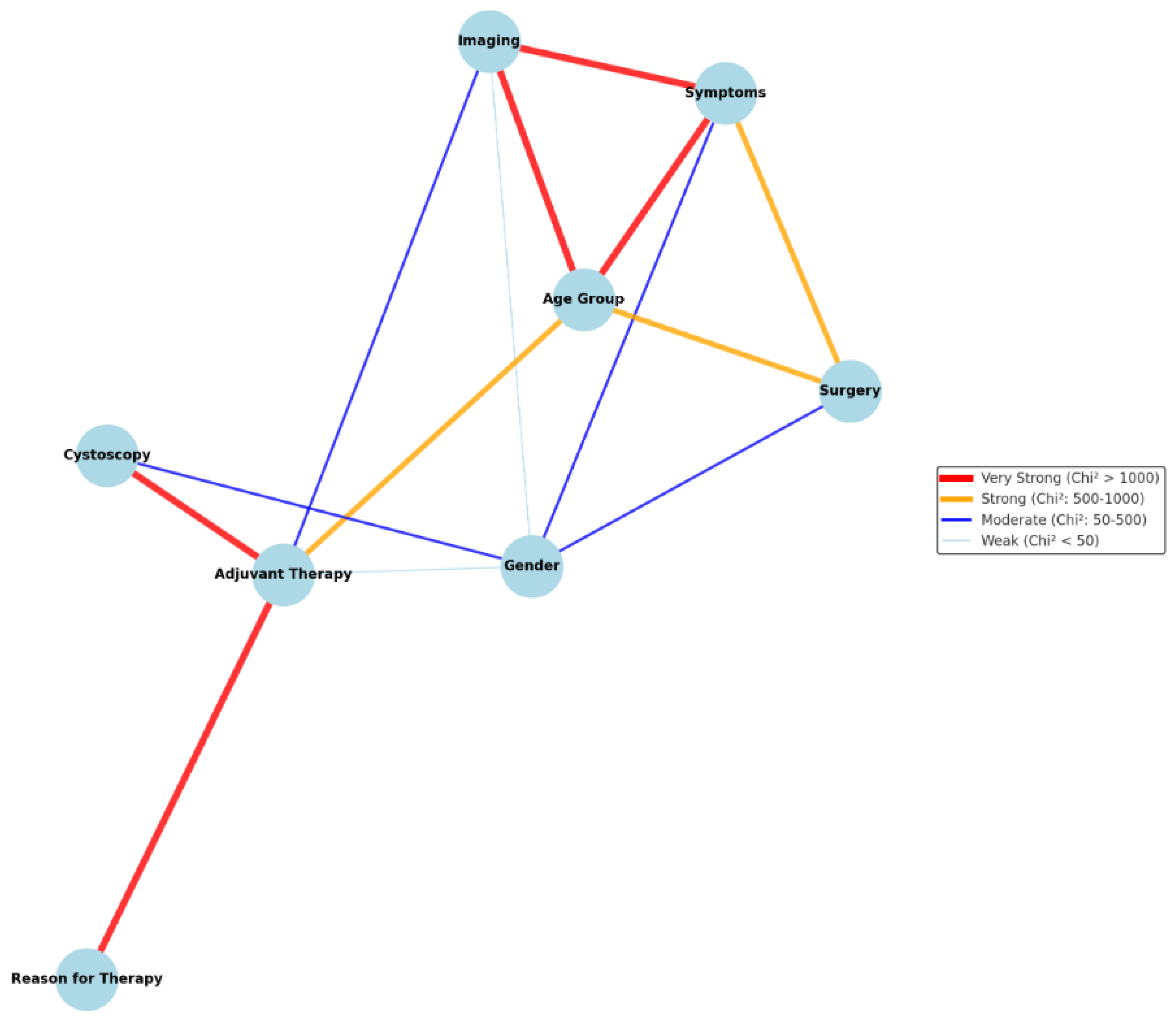

4.4.6. Factors Influencing Diagnostic Accuracy, Surgical Success and Patient Outcomes

5. Discussion

5.1. Precision and Control

5.2. Blood Loss

5.3. Hospitalization Periods

5.4. Complication Rates

5.5. Clinical and Oncological Outcomes

5.6. Efficacy and Safety

5.7. Recovery and Quality of Life

5.8. Limitations of the Study

5.9. Future Research Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Consent to Participate

Consent to Publish

References

- Stillings, S.; Merrill, M. Post TURBT Discovery of Urachal Remnant in a 62-Year-Old Man. Urology 2018, 122, 13–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mccollum, M.O.; Macneily, A.E.; Blair, G.K. Surgical implications of urachal remnants: Presentation and management. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2003, 38, 798–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stopak, J.K.; Azarow, K.S.; Abdessalam, S.F.; Raynor, S.C.; Perry, D.A.; Cusick, R.A. Trends in surgical management of urachal anomalies. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2015, 50, 1334–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iuchtman, M.; Rahav, S.; Zer, M.; Mogilner, J.; Siplovich, L. Management of urachal anomalies in children and adults. Urology 1993, 42, 426–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siefker-Radtke, A. Urachal adenocarcinoma: A clinician’s guide for treatment. Semin. Oncol. 2012, 39, 619–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schubert, G.E.; Pavkovic, M.B.; Bethke-Bedürftig, B.A. Tubular urachal remnants in adult bladders. J. Urol. 1982, 127, 40–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilday, P.S.; Finley, D.S. Robot-Assisted Excision of a Urachal Cyst Causing Dyspareunia and Dysorgasmia: Report of a Case. J. Endourol. Case Rep. 2016, 2, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naiem, M.E.A.; Mohammed, N.I.M.; Mohammed, R. Infected urachal sinus with de novo stone and peritonism in a young athlete adult: A case report. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2022, 101, 107784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, S.; Koshy, J.; Sidlow, R.; Leader, H.; Horowitz, M. To excise or not to excise infected urachal cysts: A case report and review of the literature. J. Pediatr. Surg. Case Rep. 2017, 22, 35–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.Y.; Kang, C.; Jackson, S.; Jeffery, N.; Winter, M.; Le, K.; Mansberg, R. A rare case of urachal mucinous adenocarcinoma detected by 18F-FDG PET/CT and MRI. Radiol. Case Rep. 2022, 17, 1231–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, D.; Neeman, B.; Kocherov, S.; Jaber, G.; Armon, Y.; Zilber, S.; Chertin, B. Current management of the urachal anomalies (UA). Lessons learned from the clinical practice. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2022, 38, 1619–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, J.P.; Vargas, H.A.; Lee, A.; Hutchinson, B.; O'Connor, E.; Kok, H.K.; Torreggiani, W.; Murphy, J.; Roche, C.; Bruzzi, J.; et al. The urachus revisited: Multimodal imaging of benign & malignant urachal pathology. Br. J. Radiol. 2020, 93, 20190118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orsini, A.; Bignante, G.; Lasorsa, F.; Bologna, E.; Mossack, S.M.; Pacini, M.; Marchioni, M.; Porpiglia, F.; Lucarelli, G.; Schips, L.; et al. Urachal Carcinoma: Insights From a National Database. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer 2024, 22, 102175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheldon, C.A.; Clayman, R.V.; Gonzalez, R.; Williams, R.D.; Fraley, E.E. Malignant urachal lesions. J. Urol. 1984, 131, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loizzo, D.; Pandolfo, S.D.; Crocerossa, F.; Guruli, G.; Ferro, M.; Paul, A.K.; Imbimbo, C.; Lucarelli, G.; Ditonno, P.; Autorino, R. Current Management of Urachal Carcinoma: An Evidence-based Guide for Clinical Practice. Eur. Urol. Open Sci. 2022, 39, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, P.; Ashjaee, B.; Zamani, F.; Sharifi, P. Infected urchus cyst in a teenage girl. Urol. Case Rep. 2022, 41, 101988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dababneh, H.; Gandaglia, G.; De Groote, R.; Geurts, N.; Schatteman, P.; D'Hondt, F.; De Naeyer, G.; Zazzara, M.; Novara, G.; Schiavina, R.; et al. V32 Robot-assisted partial cystectomy for the treatment of urachus acinar adenocarcinoma. Eur. Urol. Suppl. 2016, 15, eV32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedelini, P.; Chiancone, F.; Fedelini, M.; Fabiano, M.; Meccariello, C. Robot-assisted laparoscopic partial cystectomy, urachal resection and pelvic lymphadenectomy for urachal adenocarcinoma. Eur. Urol. Suppl. 2018, 17, e2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, J.; Law, Z.W.; Chen, K.; Sim, S.P.A.; Lee, L.S.; Yuen, S.P.J. Robotic-assisted Laparoscopic Partial Cystectomies (RAPC) for Urachal Diseases—The Ideal Choice. Eur. Urol. Suppl. 2018, 17, 2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaabouni, A.; Samet, A.; Mseddi, M.A.; Rebai, N.; Harbi, H.; Hadjslimene, M. Urachal mucinous cystadenoma: An exceptional entity. Urol. Case Rep. 2021, 39, 101782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; Mckenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wells, G.A.; Shea, B.; O’connell, D.; Peterson, J.; Welch, V.; Losos, M.; Tugwell, P.; The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomized Studies in Meta-Analyses. Ottawa Hospital Research Institute. 2011. Available online: https://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Moola, S.; Munn, Z.; Tufanaru, C.; Aromataris, E.; Sears, K.; Sfetcu, R.; Currie, M.; Lisy, K.; Qureshi, R.; Mattis, P.; et al.; Chapter 7: Systematic reviews of etiology and risk In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E., Munn, Z., Eds.; 2020. Available online: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global (accessed on 13 January 2025). [CrossRef]

- Madeb, R.; Knopf, J.K.; Nicholson, C.; Donahue, L.A.; Adcock, B.; Dever, D.; Tan, B.J.; Valvo, J.R.; Eichel, L. The use of robotically assisted surgery for treating urachal anomalies. BJU Int. 2006, 98, 838–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nayyar, R.; Anand, A.; Gupta, N. VID-06.07: Robotic Partial Cystectomy for Urachal Adenocarcinoma: Results with Technique of Cystoscopically Optimized Surgical Margins. Urology 2009, 74, S166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa, J.J.; Hakky, T.S.; Spiess, P.E.; Chuang, T.; Sexton, W.J. Robotic-assisted partial cystectomy with en bloc excision of the urachus and the umbilicus for urachal adenocarcinoma. J. Robot. Surg. 2010, 3, 235–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.K.; Lee, J.W.; Park, S.Y.; Kim, Y.T.; Park, H.Y.; Lee, T.Y. Initial experience with robotic-assisted laparoscopic partial cystectomy in urachal diseases. Korean J. Urol. 2010, 51, 318–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.E.; Jeong, C.W.; Ku, J.H. Robot-assisted laparoscopic management of urachal cysts in adults. J. Robot. Surg. 2010, 4, 133–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadtayev, S.; Bishop, C.V.; Adshead, J.M. Robotic assisted partial cystectomy for urachal neoplasms: Experience at a regional uro-oncological centre. Eur. Urol. Suppl. 2011, 10, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raynor, M.; Langston, J.; Selph, P.; Smith, A.; Nielsen, M.; Wallen, E.; Pruthi, R. V1881 Initial Experience with Robotic-Assisted Approaches to Partial Cystectomy. J. Urol. 2011, 185, e753–e754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, M.; Granberg, C.F.; Tollefson, M.K. Robotic-assisted laparoscopic surgery of urachal anomalies: A single-center experience. J. Laparoendosc. Adv. Surg. Tech. A 2015, 25, 291–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, K.; Vasdev, N.; Mohan, S.G.; Lane, T.; Adshead, J.M. Robotic Partial Cystectomy for Primary Urachal Adenocarcinoma of the Urinary Bladder. Curr. Urol. 2015, 8, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fode, M.; Pedersen, G.L.; Azawi, N. Symptomatic urachal remnants: Case series with results of a robot-assisted laparoscopic approach with primary umbilicoplasty. Scand. J. Urol. 2016, 50, 463–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, H.; Howe, A.S.; Dyer, L.L.; Fine, R.G.; Gitlin, J.S.; Schlussel, R.N.; Zelkovic, P.F.; Palmer, L.S. Robot-assisted Laparoscopic Urachal Excision in Children. Urology 2017, 106, 103–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yong, J.; Law, Z.W.; Yang, X.Y.; Ng, T.K.; Yuen, J.S.P. Robotic-assisted laparoscopic partial cystectomies (RAPC) for urachal diseases: Intuitive surgery for total umbilical tract excision and umbilectomy. Urol. Video J. 2020, 7, 100039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osumah, T.S.; Granberg, C.F.; Butaney, M.; Gearman, D.J.; Ahmed, M.; Gargollo, P.C. Robot-Assisted Laparoscopic Urachal Excision Using Hidden Incision Endoscopic Surgery Technique in Pediatric Patients. J. Endourol. 2021, 35, 937–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokkel, L.E.; van de Kamp, M.W.; Schaake, E.E.; Boellaard, T.N.; Hendricksen, K.; van Rhijn, B.W.; Mertens, L.S. Robot-Assisted Partial Cystectomy versus Open Partial Cystectomy for Patients with Urachal Cancer. Urol. Int. 2022, 106, 840–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamzon, J.; Kokorowski, P.; De Filippo, R.E.; Chang, A.Y.; Hardy, B.E.; Koh, C.J. Pediatric robot-assisted laparoscopic excision of urachal cyst and bladder cuff. J. Endourol. 2008, 22, 2385–2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spiess, P.E.; Correa, J.J. Robotic assisted laparoscopic partial cystectomy and urachal resection for urachal adenocarcinoma. Int. Braz. J. Urol. 2009, 35, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allaparthi, S.; Ramanathan, R.; Balaji, K.C. Robotic partial cystectomy for bladder cancer: A single-institutional pilot study. J. Endourol. 2010, 24, 223–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosanovic, R.; Romero, R.J.; Arad, J.K.; Gallas, M.; Seetharamaiah, R.; Gonzalez, A.M. Rare use of robotic surgery for removal of large urachal carcinoma. J. Robot. Surg. 2014, 8, 177–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoun, F.; Peltier, A.; van Velthoven, R. Bladder sparing robot-assisted laparoscopic en bloc resection of urachus and umbilicus for urachal adenocarcinoma. J. Robot. Surg. 2015, 9, 167–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, C.R.; Chavda, K. En Bloc Robot-assisted Laparoscopic Partial Cystectomy, Urachal Resection, and Pelvic Lymphadenectomy for Urachal Adenocarcinoma. Rev. Urol. 2015, 17, 46–49. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shepler, R.; Zuckerman, J.M.; Troyer, D.; Malcolm, J.B. Robotic-assisted laparoscopic partial cystectomy for symptomatic urachal hamartoma. Turk. J. Urol. 2016, 42, 44–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, A.; Chong, J.; Si, Q.; Haines, K.; Mehrazin, R. Robotic approach to resection of villous adenoma of the urachus: A case report and literature review. J. Robot. Surg. 2018, 12, 567–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proskura, A.; Shpot, E. Robot-assisted laparoscopic en-bloc partial cystectomy, urachal resection, umbilectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy with intracorporeal ultrasonography for urachal adenocarcinoma: A case report. Eur. Urol. Suppl. 2018, 17, e1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, R.; Swerdloff, D.; Akgul, M.; Nazeer, T.; Mian, B.M. A rare case of urachal inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor. Urol. Case Rep. 2021, 36, 101575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, J.; Zheng, Y.; Stark, A.; Smith, T.; Grubb, R.L. Umbilical sparing robotic partial cystectomy for localized urachal adenocarcinoma: A case report. Urol. Case Rep. 2021, 38, 101682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lough, C.P.; Rosen, G.H.; Murray, K.S. Robotic excision of a calcified urachal cyst: A video case report. Urol. Video J. 2021, 10, 100085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahr, R.A.; Colinet, V.; Mattlet, A.; Jabbour, T.; Diamand, R. Robotic Partial Cystectomy for Urachal Carcinoma: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Case Rep. Urol. 2021, 2021, 6743515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arena, S.; Rossanese, M.; Di Fabrizio, D.; Romeo, C.; Ficarra, V.; Impellizzeri, P. Robot-assisted excision of urachal cyst: Case report in a child. Ann. Pediatr. Surg. 2021, 17, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.B.; Park, H.S.; Kim, J.H.; Park, J. A rare case of eosinophilic cystitis involving the inside and outside of the urinary bladder associated with an infected urachal cyst. BMC Urol. 2021, 21, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.J.; Bin Kim, W.; Lee, K.W.; Kim, J.M.; Kim, Y.H.; Kim, J.H.; Moon, A.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, S.W. Robot-assisted laparoscopic intracorporeal urachal mass resection and partial cystectomy for a huge urachal adenocarcinoma: A case report and review of literature. J. Men’s Health 2021, 17, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochvar, A.P.; Bednar, G.; Albani, J.M. Low-Grade Urachal Cystadenoma With Abundant Calcification Removed Using Robot-Assisted Laparoscopy: A Case Report. Cureus 2023, 15, e47209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogaerts, Q.; Vanthoor, J.; Goethuys, H.; Raskin, Y. Cystoscopic and robotic-assisted laparoscopic excision of a rare urachus neoplasm by partial cystectomy. Urol. Video J. 2023, 17, 100209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunitsky, K.D.; Almajedi, M.; Snajdar, E.; Adams, P.; Nelson, R. Single-Port Robotic-Assisted Excision of the Urachal Remnant in an Adult Female: A Case Report. Cureus 2024, 16, e53235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemal, S.; Sobhani, S.; Hakimi, K.; Rosenberg, S.; Gill, I. Single-Port Robot assisted partial cystectomy for urachal adenocarcinoma. Int. Braz. J. Urol. 2024, 50, 659–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamasaki, S.; Kaneko, G.; Yabuno, A.; Miyama, Y.; Hiruta, S.; Hagiwara, M.; Shirotake, S.; Yasuda, M.; Oyama, M. Robot-Assisted Partial Cystectomy Using the “Double Bipolar Method”. Cureus 2024, 16, e61610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsheikh, M.; Oxley, J.; Qureshi, F.; Thornton, M. A Rare Case of Urinary Bladder Leiomyoma Invading Urachal Remnant Managed With Robotic Partial Cystectomy. Cureus 2024, 16, e64222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiesfeldt, D.L.; Seth, A.; Ellsworth, P. A large urachal cyst presenting with lower urinary tract symptoms and a falsely elevated post-void residual on bladder scan. Urol. Case Rep. 2024, 53, 102655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rich, J.M.; Gonzalez, A.N.; Murray, K.S. Robotic urachal cyst removal: Video case report and tutorial for robotic surgical trainees. Urol. Video J. 2024, 21, 100265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Checcucci, E.; Amparore, D.; Fiori, C.; Manfredi, M.; Ivano, M.; Di Dio, M.; Niculescu, G.; Piramide, F.; Cattaneo, G.; Piazzolla, P.; et al. 3D imaging applications for robotic urologic surgery: An ESUT YAUWP review. World J. Urol. 2020, 38, 869–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallagher, A.G.; De Groote, R.; Paciotti, M.; Mottrie, A. Proficiency-based Progression Training: A Scientific Approach to Learning Surgical Skills. Eur. Urol. 2022, 81, 394–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dell’oglio, P.; Turri, F.; Larcher, A.; D’hondt, F.; Sanchez-Salas, R.; Bochner, B.; Palou, J.; Weston, R.; Hosseini, A.; Canda, A.E.; et al. Definition of a Structured Training Curriculum for Robot-assisted Radical Cystectomy with Intracorporeal Ileal Conduit in Male Patients: A Delphi Consensus Study Led by the ERUS Educational Board. Eur. Urol. Focus 2022, 8, 160–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamand, R.; D'Hondt, F.; Mjaess, G.; Jabbour, T.; Dell'Oglio, P.; Larcher, A.; Moschini, M.; Quackels, T.; Peltier, A.; Assenmacher, G.; et al. Teaching robotic cystectomy: Prospective pilot clinical validation of the ERUS training curriculum. BJU Int. 2023, 132, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larcher, A.; De Naeyer, G.; Turri, F.; Dell’oglio, P.; Capitanio, U.; Collins, J.W.; Wiklund, P.; Van Der Poel, H.; Montorsi, F.; Mottrie, A. The ERUS Curriculum for Robot-assisted Partial Nephrectomy: Structure Definition and Pilot Clinical Validation. Eur. Urol. 2019, 75, 1023–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pecoraro, A.; Territo, A.; Boissier, R.; Hevia, V.; Prudhomme, T.; Piana, A.; Marco, B.B.; Gallagher, A.G.; Serni, S.; Decaestecker, K.; et al. Proposal of a standardized training curriculum for open and robot-assisted kidney transplantation. Minerva Urol. Nephrol. 2024, 76, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mottrie, A.; Novara, G.; van der Poel, H.; Dasgupta, P.; Montorsi, F.; Gandaglia, G. The European Association of Urology Robotic Training Curriculum: An Update. Eur. Urol. Focus 2016, 2, 105–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornblade, L.W.; Fong, Y. Simulation-Based Training in Robotic Surgery: Contemporary and Future Methods. J. Laparoendosc. Adv. Surg. Tech. A 2021, 31, 556–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergholz, M.; Ferle, M.; Weber, B.M. The benefits of haptic feedback in robot assisted surgery and their moderators: A meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 19215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez, A.; Herrera, L.; Teixeira, A.; Cheatham, M.; Gibson, D.; Lam, V.; Guevara, O. Improving efficiency and reducing costs in robotic surgery: A Lean Six Sigma approach to optimize turnover time. J. Robot. Surg. 2023, 17, 2059–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nayeemuddin, M.; Daley, S.C.; Ellsworth, P. Modifiable factors to decrease the cost of robotic-assisted procedures. AORN J. 2013, 98, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basile, G.; Gallioli, A.; Diana, P.; Gallagher, A.; Larcher, A.; Graefen, M.; Harke, N.; Traxer, O.; Tilki, D.; Van Der Poel, H.; et al. Current Standards for Training in Robot-assisted Surgery and Endourology: A Systematic Review. Eur. Urol. 2024, 86, 130–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etta, P.; Chien, M.; Wang, Y.; Patel, A. Robotic partial nephrectomy: Indications, patient selection, and setup for success. Urol. Oncol. 2024, in press. [CrossRef]

- Balbay, M.D.; Koc, E.; Canda, A.E. Robot-assisted radical cystectomy: Patient selection and special considerations. Robot. Surg. 2017, 4, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palagonia, E.; Mazzone, E.; De Naeyer, G.; D’hondt, F.; Collins, J.; Wisz, P.; Van Leeuwen, F.W.B.; Van Der Poel, H.; Schatteman, P.; Mottrie, A.; et al. The safety of urologic robotic surgery depends on the skills of the surgeon. World J. Urol. 2020, 38, 1373–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leddy, L.; Lendvay, T.; Satava, R. Robotic surgery: Applications and cost effectiveness. Open Access Surg. 2010, 3, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maccraith, E.; Forde, J.C.; Davis, N.F. Robotic simulation training for urological trainees: A comprehensive review on cost, merits and challenges. J. Robot. Surg. 2019, 13, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knudsen, J.E.; Ghaffar, U.; Ma, R.; Hung, A.J. Clinical applications of artificial intelligence in robotic surgery. J. Robot. Surg. 2024, 18, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guni, A.; Varma, P.; Zhang, J.; Fehervari, M.; Ashrafian, H. Artificial Intelligence in Surgery: The Future is Now. Eur. Surg. Res. 2024, 65, 22–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iftikhar, M.; Saqib, M.; Zareen, M.; Mumtaz, H. Artificial intelligence: Revolutionizing robotic surgery: Review. Ann. Med. Surg. 2024, 86, 5401–5409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Stage I: Tumor confined to the urachus. |

| Stage II: Tumor invading the bladder. |

| Stage III: Local extension beyond the bladder. |

| IIIA: Tumor invasion into the abdominal wall. IIIB: Tumor invasion into the peritoneum. IIIC: Tumor invasion into other local structures. |

| Stage IV: Metastatic disease. |

| IVA: Regional lymph node metastasis. IVB: Distant metastasis. |

| NCT Number | Study Title | Study Status | Intervention |

|---|---|---|---|

| NCT00082706 | Fluorouracil, Leucovorin, Gemcitabine, and Cisplatin in Treating Patients With Metastatic or Unresectable Adenocarcinoma | Active, Not Recruiting | 5-FU, Leucovorin, Cisplatin, Gemcitabine |

| NCT05756569 | Enfortumab Vedotin Plus Pembrolizumab for the Treatment of Locally Advanced or Metastatic Bladder Cancer of Variant Histology | Recruiting | Enfortumab Vedotin, Pembrolizumab |

| NCT04923178 | A Multicenter Natural History of Urothelial Cancer and Rare Genitourinary Tract Malignancies | Recruiting | None (Observational) |

| NCT03866382 | Testing the Effectiveness of Two Immunotherapy Drugs (Nivolumab and Ipilimumab) With One Anti-cancer Targeted Drug (Cabozantinib) for Rare Genitourinary Tumors | Recruiting | Cabozantinib, Ipilimumab, Nivolumab |

| NCT06638931 | Agnostic Therapy in Rare Solid Tumors | Recruiting | Nivolumab |

| Study | Selection | Comparability | Outcome | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Madeb R. (2006) [24] | 3 | 1 | 2 | 6 |

| Nayyar R. (2009) [25] | 3 | 1 | 2 | 6 |

| Correa J.J. (2009) [26] | 3 | 1 | 2 | 6 |

| Kim D.K. (2010) [27] | 3 | 1 | 2 | 6 |

| Lee H.E. (2010) [28] | 3 | 1 | 2 | 6 |

| Tadtayev S. (2011) [29] | 3 | 1 | 2 | 6 |

| Raynor M. (2011) [30] | 3 | 1 | 2 | 6 |

| Rivera M. (2015) [31] | 3 | 1 | 3 | 7 |

| James K. (2015) [32] | 3 | 1 | 3 | 7 |

| Fode M. (2016) [33] | 3 | 1 | 3 | 7 |

| Ahmed H. (2017) [34] | 3 | 1 | 3 | 7 |

| Yong J. (2020) [35] | 3 | 1 | 2 | 6 |

| Osumah T.S. (2021) [36] | 3 | 1 | 2 | 6 |

| Perez D. (2022) [11] | 3 | 1 | 2 | 6 |

| Stokkel L.E. (2022) [37] | 3 | 1 | 3 | 7 |

| Author (Year) | Institution (Country) | Volume (Number of Cases) | Reason for Surgery (Number of Cases) |

Symptoms | Imaging Method | Cystoscopy Result | Preoperative TURBT | Lymph Node Involvement | Metastases | Umbilicus Removal | Lymphadenectomy | Complications | Hospital Stay (Days) | Histopathological Findings (Number of Results) | Robotic System | Operation Time (min.) | Console Time (min.) | Blood Loss (mL) | Patient Sex (M—Male, F—Female) |

Patient Age | Follow-Up Duration (Months) | Follow-Up Cystoscopy | Follow-Up Cystoscopy Result | Follow-Up CT | Follow-Up CT Result | Adjuvant Therapy | Adjuvant Therapy Details |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Madeb R. (2006) [24] |

Rochester General Hospital (USA) | 5 | Urachal anomalies (remnants) (2), urachal adenocarcinoma (3) | Hematuria, irritative LUTS, dysuria | US, CT, MRI | Urachal submucosal mass, bladder dome tumor | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Small bowel perforation, postoperative repair | 2 (3 patients), 14 (1 patient), 6 (1 patient) | Benign diverticulum (1), adenocarcinoma (3), leiomyoma (1) |

da Vinci | 120–480 | N/A | 25–300 | 3 M 2 F |

22–68 | 8 | Yes | Normal | Yes | No recurrence | No | N/A |

| Yamzon J. (2008) [38] |

University of Southern California (USA) | 1 | Urachal cyst | Midline abdominal pain | CT | N/A | No | No | No | Yes | No | None | N/A | Benign urachal cyst with acute and chronic inflammation | da Vinci | N/A | N/A | N/A | F | 4 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | No | N/A |

| Spiess P.E. (2009) [39] |

H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center (USA) |

1 | Urachal adenocarcinoma | Hematuria, mucosuria | CT | Bladder dome tumor | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | None | 4 | pT2N0Mx adenocarcinoma with negative margins | N/A | 300 | N/A | 150 | M | 55 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | No | N/A |

| Nayyar R. (2009) [25] |

All India Institute of Medical Sciences (India) | 3 | Urachal adenocarcinoma | Hematuria | US, CT | Bladder dome tumor, margins marked | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | None | 3 | Urachal adenocarcinoma, margins free (3) | da Vinci S | 182 | N/A | <100 | Mixed (non-specified) | N/A | 8 | Yes | Normal | N/A | N/A | No | N/A |

| Correa J.J. (2009) [26] |

H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center (USA) |

2 | Urachal adenocarcinoma | Hematuria, mucosuria, pain | CT | Bladder dome tumor | Yes | Yes (1 patient) |

No | Yes | Yes | None | 4 (1 patient), 7 (1 patient) | pT2NxMx adenocarcinoma, pT3N1Mx adenocarcinoma | N/A | 300–354 | N/A | 100–150 | M | 53–55 | <3 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | Cisplatin, 5-fluorouracil (1 patient) |

| Allaparthi S. (2010) [40] |

University of Massachusetts Medical School (USA) |

1 | Urachal adenocarcinoma | Hematuria | CT, MRI | Bladder dome tumor | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Bowel obstruction requiring resection (readmission) | 2 | Invasive adenocarcinoma, margins free | da Vinci | 165 | N/A | 20 | M | 24 | 6 | Yes | Normal | Yes | No recurrence | No | N/A |

| Kim D.K. (2010) [27] |

Hanyang University (Korea) | 4 | Urachal cyst (2), patent urachus (1), urachal cystadenoma (1) | Hematuria, dysuria, mucosuria | CT | Bladder dome mass | No | No | No | Yes | No | None | 4–7 | Urachal cyst (2), patent urachus (1), urachal cystadenoma (1) | da Vinci S | 130–260 | 70–150 | 20–250 | 2 M 2 F |

45–65 | 1 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | No | N/A |

| Lee H.E. (2010) [28] |

Seoul National University Hospital (Korea) | 2 | Urachal cyst | Gross hematuria, lower abdominal pain | CT | Urachal cyst with inflammation | No | No | No | Yes | No | None | 1 | Urachal cyst with non-specific inflammation | N/A | 220–225 | N/A | Minimal | 1 M 1 F |

43–47 | N/A | No | N/A | No | N/A | No | N/A |

| Tadtayev S. (2011) [29] |

Lister Hospital (UK) |

4 | Urachal adenocarcinoma | N/A | N/A | Bladder dome tumor | Yes | Yes (3 patients) |

Yes (1 patient) |

Yes | Yes | None | 4 | pT2-pT3 adenocarcinoma, villous adenoma | N/A | 150–240 | 70–170 | 20–250 | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | Normal (all 3 cases with curative intent) | Yes | No recurrence (all 3 cases with curative intent) | No | N/A |

| Raynor M. (2011) [30] |

University of North Carolina (USA) | 12 | Urachal adenocarcinoma (4), symptomatic urachal cyst/sinus (8) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | N/A | None | 1–3 | N/A | N/A | 79–200 | N/A | 25–75 | 7 M 5 F |

42.1 (mean) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | No | N/A |

| Kosanovic R. (2014) [41] |

Baptist Health South Florida (USA) | 1 | Urachal adenocarcinoma | Recurrent UTIs | US, MRI | Normal | No | No | No | Yes | No | None | 3 | Well-differentiated mucinous adenocarcinoma, muscularis propria involvement | da Vinci | N/A | N/A | N/A | F | 53 | N/A | Yes | Normal | N/A | N/A | No | N/A |

| Rivera M. (2015) [31] |

Mayo Clinic (USA) | 11 | urachal cyst (5), urachal remnant (3), fibrovascular necrotizing granuloma (1), urachal cyst with colonic metaplasia (1), urachal cyst with fibrosis (1) | Umbilical drainage, abdominal pain, infection | CT, MRI | N/A | No | No | No | No | No | UTI requiring antibiotics | 1–2 | urachal cyst (5), urachal remnant (3), fibrovascular necrotizing granulomatous tissue (1), urachal cyst with colonic metaplasia (1), urachal cyst with fibrosis (1) | N/A | 51–224 | N/A | 5–400 | 7 M 4 F |

12–72 | 1–18 15.5 (mean |

N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | No | N/A |

| Aoun F. (2015) [42] |

Jules Bordet Institute (Belgium) | 1 | Urachal adenocarcinoma | Gross hematuria | US, MRI | Bladder dome mass (small) | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | None | 4 | Moderately differentiated mucinous colloid adenocarcinoma, pT2b stage | da Vinci SI | N/A | N/A | N/A | F | 47 | 3 | Yes | Normal | Yes | No recurrence | No | N/A |

| James K. (2015) [32] |

Lister Hospital (UK) | 8 | Urachal adenocarcinoma | Hematuria, dysuria | CT, MRI | Bladder dome mass | Yes | Yes | Yes (1 patient) |

Yes | Yes | None | 4 | Primary urachal adenocarcinoma of bladder, no positive margins | da Vinci S | 130–240 | 70–170 | 50 | 5 M 3 F |

49–63 | 32 | Yes | Normal (8/8 patients) |

Yes | No recurrence (7/8 patients) |

Yes | Oxaliplatin and Capecitabine (1 patient) |

| Williams C.R. (2015) [43] |

University of Florida (USA) |

1 | Urachal adenocarcinoma | Abdominal pain, hematuria | CT, PET scan | N/A | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | None | 1 | Urachal mucinous adenocarcinoma, negative surgical margin, no lymph node involvement | da Vinci | 300 | N/A | 5 | F | 20 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | No | N/A |

| Fode M. (2016) [33] |

Zealand University Hospital (Denmark) | 9 | Urachal Remnants | Hematuria, umbilical secretion, UTI | CT | Urachal remnant mass (1 case), urachal remnant ducts (5 cases) |

No | No | No | Yes | No | Fascia rupture (3), bleeding spleen (1) |

1–2 | well-differentiated adenocarcinoma (1), benign lesions (8) | N/A | 90–120 | N/A | N/A | 5 M 4 F |

15–73 | 36 | Yes | Normal | Yes | No recurrence | No | N/A |

| Dababneh H. (2016) [17] |

Sant’Orsola Malpighi, Bologna (Italy) |

1 | Urachal acinar adenocarcinoma | Hematuria | US, CT | Bladder dome tumor | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | None | 3 | pT3b acinar adenocarcinoma with negative surgical margins | N/A | 300 | 250 | <50 | M | 55 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | No | N/A |

| Kilday P.S. (2016) [7] |

Kaiser Permanente Los Angeles (USA) | 1 | Urachal cyst | Dyspareunia, dysorgasmia, abdominal pain | CT, MRI | Normal | No | No | No | Yes | No | None | 1 | No malignancy | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | F | 29 | 12 | No | N/A | No | N/A | No | N/A |

| Shepler R. (2016) [44] |

Eastern Virginia Medical School (USA) |

1 | Urachal hamartoma | Dysuria, urinary frequency, nocturia | CT | Bladder dome mass | Yes | No | No | No | No | None | 1 | Urachal hamartoma, benign | N/A | 150 | N/A | 100 | F | 30 | 3 | No | N/A | No | N/A | No | N/A |

| Ahmed H. (2017) [34] |

Cohen Children’s Medical Center (USA) | 16 | Umbilical drainage (5), infections (7), umbilical drainage and infection (2), incidental findings (3) | Umbilical drainage, infection | US | Normal | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Bladder leakage (1) | 1–2 | Chronic inflammation, no malignancy | N/A | 107 (mean) | N/A | N/A | 10 M 6 F |

0.8–16.5 | 9–21 | N/A | N/A l | N/A | N/A | No | N/A |

| Chen A. (2017) [45] |

Albany Medical College (USA) |

1 | Urachal villous adenoma | Mucoid discharge, dysuria, hematuria | CT, cystogram | Urachal mass, mucous discharge | No | No | No | Yes | No | None | 1 | Villous adenoma with papillary fronds and fibrovascular cores, no malignancy | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | F | 47 | N/A | Yes | Normal | N/A | N/A | No | N/A |

| Fedelini P. (2018) [18] |

A.Cardarelli Hospital, Dept. of Urology (Italy) | 1 | Mucinous urachal adenocarcinoma | Gross hematuria, dysuria | MRI | Bladder dome solid mass | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | None | 4 | Poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, 2/17 lymph nodes positive for metastases | N/A | 120 | N/A | Minimal | M | 40 | 6 | Yes | Normal | Yes | No recurrence | Yes | Enrolled in strict follow-up protocol |

| Stillings S. (2018) [1] |

Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center (USA) |

1 | Urachal remnant | Dysuria, perineal pain, hematuria | CT urogram | Bladder dome tumor (large) | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | None | 3 | Chronic inflammation, negative for malignancy | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | M | 62 | N/A | No | N/A | No | N/A | No | N/A |

| Proskura A. (2018) [46] |

Sechenov University (Russia) | 1 | Mucinous urachal adenocarcinoma | Gross hematuria | MRI | Bladder dome mass (1 cm) |

No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | None | N/A | Mucinous adenocarcinoma invading submucosa, 1/23 lymph nodes positive | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | F | 34 | 6 | No | N/A | Yes | No recurrence | Yes | 6 courses of 5-fluorouracil and cisplatin |

| Yong J. (2020) [35] |

Singapore General Hospital (Singapore) | 9 | Urachal adenocarcinoma (3), benign urachal nodules (6) | Gross hematuria | CT | Solid urachal lesion | No | No | No | Yes (4 patients) | No | Urosepsis (1), acute urinary retention (1) | 2 | Urachal adenocarcinoma (3), benign nodules (6) | da Vinci Xi | 190 (mean) | N/A | 50 | 8 M 1 F |

44–64 | 6 | No | N/A | No | N/A | No | N/A |

| George R. (2021) [47] |

Albany Medical Center (USA) |

1 | Urachal inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor | Abdominal pain, dysuria | US, CT | Mixed solid/cystic mass | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | None | 2 | Urachal inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor with ALK gene rearrangement | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | F | 27 | 5 | No | N/A | No | N/A | No | N/A |

| Connor J. (2021) [48] |

Medical University of South Carolina (USA) | 1 | Mucinous cystadenocarcinoma of urachus | Frequency, urgency | CT, MRI | Bladder wall thickening | No | No | No | No | No | None | 1 | Mucinous cystadenocarcinoma, no invasion | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | M | 67 | 12 | No | N/A | Yes | No recurrence | No | N/A |

| Lough C.P. (2021) [49] |

University of Missouri School of Medicine (USA) | 1 | Calcified urachal cyst | Gross hematuria | CT urogram | Normal | No | No | No | No | No | None | 1 | Calcified urachal cyst, no malignancy | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | F | 50 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Abou Zahr R. (2021) [50] |

Jules Bordet Institute, Brussels (Belgium) | 1 | Mucinous urachal adenocarcinoma | Gross hematuria | CT, MRI | Mucinous lesion at bladder dome | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | None | 5 | Mucinous adenocarcinoma, pT3bNx | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | F | 49 | 12 | No | N/A | Yes | No recurrence | No | N/A |

| Arena S. (2021) [51] |

University of Messina (Italy) | 1 | Urachal cyst | Suprapubic abdominal pain | MRI | Supra-vesical cyst | No | No | No | Yes | No | None | 7 | Benign urachal cyst, no malignancy | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | F | 15 | 3 | No | N/A | No | N/A | No | N/A |

| Osumah T.S. (2021) [36] |

Mayo Clinic (USA) | 14 | Urachal remnant (9), cyst (3), patent urachus (2) | Abdominal pain, fever, UTI, umbilical drainage | US, CT | Normal | No | No | No | Yes (some cases) | No | UTI (1), persistent abdominal pain (1) | 1 | Benign findings, no malignancy | da Vinci Xi | 133 (median) | N/A | Minimal | 9 M 5 F |

2–16 | 0.25 | No | N/A | No | N/A | No | N/A |

| Shin H.B. (2021) [52] |

Eulji University Hospital (Korea) | 1 | Eosinophilic cystitis with infected urachal cyst | Gross hematuria, fever, dysuria, suprapubic pain | CT | Raspberry-like mass at bladder dome | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | None | 7 | Eosinophilic cystitis with heavy eosinophilic infiltration and infected urachal cyst | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | M | 59 | 23 | Yes | Normal | Yes | No recurrence | No | N/A |

| Park J.J. (2021) [53] |

Soonchunhyang University Hospital (Korea) | 1 | Large urachal adenocarcinoma | No symptoms | CT | Lobulated mass at bladder dome | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | None | 14 | Well-differentiated mucinous adenocarcinoma, negative margins | da Vinci Xi | 150 | N/A | 50 | M | 71 | 3 | No | N/A | Yes | No recurrence | No | N/A |

| Jiang J.Y. (2022) [10] |

Nepean Hospital, Dept. of Nuclear Medicine (Australia) | 1 | Mucinous urachal adenocarcinoma | Dysuria, urgency, macrohematuria | PET/CT, MRI | Mixed solid/cystic mass with calcification | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | None | 7 | Mucinous adenocarcinoma, invasion through bladder wall | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | F | 24 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Perez D. (2022) [11] |

Shaare Zedek Medical Center, Jerusalem (Israel) | 9 | Urachal cyst (5), sinus (2), diverticulum (1), patent urachus (1) | Umbilical discharge, abdominal pain, hematuria, recurrent UTI | US, CT, MRI, VCUG | Urachal mass | No | No | No | Yes (5 patients) | No | Grade IIIA (1) infected hematoma, Grade IIIB (1) abscess reoperation | 1–7 | 6 cases with urothelium, including 2 with necrotizing granuloma; 3 cases without epithelium | N/A | 52–140 | N/A | N/A | 6 M 3 F |

0–37 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | No | N/A |

| Stokkel L.E. (2022) [37] |

Netherlands Cancer Institute (Netherlands) | 8 | Urachal adenocarcinoma | Gross hematuria, abdominal pain | CT, MRI | Mass at bladder dome | No | Yes (3 patients) | No | Yes | Yes (3 patients) | Grade V (1) arterial occlusion, Grade III (1) urinary leakage |

2–8 | Adenocarcinoma, stages pT2–pT4, 3 cases with positive lymph nodes | N/A | 90–180 | N/A | N/A | 5 M 3 F |

42–79, 60 (mean) |

25–56 31 (mean) |

Yes | 7 patients normal 1 patient local recurrence |

Yes | 2 patients port-site recurrence |

Yes | 1 patient external radiotherapy and brachytherapy 1 patient palliative chemotherapy (not specified) |

| Kochvar A.P. (2023) [54] |

Kansas City Urology Care, Kansas City (USA) | 1 | Low-grade urachal cystadenoma with calcification | Left lower quadrant pain | US, MRI | Extrinsic bladder compression | No | No | No | No | No | None | 1 | Low-grade mucinous cystadenoma with calcified mucin | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | F | 57 | N/A | Yes | Normal | Yes | No recurrence | No | N/A |

| Bogaerts Q. (2023) [55] |

Ziekenhuis Oost-Limburg, Genk (Belgium) | 1 | Mucinous cystic tumor of low malignant potential | No symptoms | PET-CT | Mass at bladder dome | No | No | No | Yes | No | None | 1 | Mucinous cystic tumor with low malignant potential | da Vinci Xi | 75 | N/A | Minimal | F | 59 | 6 | No | N/A | Yes | No recurrence | No | N/A |

| Kunitsky K.S. (2024) [56] |

Kansas City Urology Care, Kansas City (USA) | 1 | Symptomatic urachal remnant | Dysuria, urinary frequency, intermittent hematuria, right flank pain | CT | Bladder wall thickening | No | No | No | Yes | No | None | 1 | Urachal remnant, benign (no malignancy) | da Vinci SP | 135 | N/A | 10 | F | 34 | 1 | No | N/A | No | N/A | No | N/A |

| Hemal S. (2024) [57] |

University of Southern California (USA) | 1 | Urachal adenocarcinoma | Hematuria, mucosuria | CT, MRI | Solitary tumor at bladder dome | Yes | Yes (bilateral) | No | Yes | Yes | None | 1 | Muscle-invasive adenocarcinoma, pT2b, negative margins | da Vinci SP | 100 | N/A | 20 | M | 41 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | No | N/A |

| Hamasaki S. (2024) [58] |

Saitama Medical University (Japan) | 1 | Urachal remnant | No symptoms | MRI | Protruding lesion with normal mucosa | No | No | No | Yes | No | None | 6 | Urachal remnant with normal urothelium | da Vinci Xi | N/A | N/A | Minimal | F | 55 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | No | N/A |

| Elsheikh M. (2024) [59] |

Royal Bournemouth Hospital, Bournemouth (UK) | 1 | Transmural bladder leiomyoma invading urachal remnant | Gross hematuria, dysuria | CT, MRI | 4 cm mass at bladder dome | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | None | 2 | Infarcted bladder leiomyoma, no malignancy | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | M | 29 | N/A | No | N/A | No | N/A | No | N/A |

| Thiesfeldt D.L. (2024) [60] |

University of Central Florida College of Medicine, Nemours Children’s Hospital (USA) | 1 | Large urachal cyst | Lower urinary tract symptoms, falsely elevated post-void residual | US, MRI | Normal | No | No | No | No | No | None | 1 | Urachal cyst with no malignancy | N/A | N/A | N/A | Minimal | M | 11 | N/A | No | N/A | No | N/A | No | N/A |

| Rich J.M. (2024) [61] |

NYU Langone Health, NYU School of Medicine (USA) | 1 | Recurrent urachal cyst | Umbilical pain, umbilical drainage | CT, MRI | Cyst with rim-enhancing fluid collection | No | No | No | Yes | No | None | 1 | Urachal cyst, no malignancy | N/A | N/A | N/A | Minimal | M | 24 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | No | N/A |

| Our work | Multidisciplinary Hospital in Warsaw-Miedzylesie (Poland) | 3 | Suspected urachal tumor (2), urachal tumor (1) | Suprapubic pain, hematuria | CT | Tumor at the bladder dome (2 cases), normal (1 case) | No | No | No | No | No | Gade II: red blood cell concentrates transfusion (1) | 6.33 (mean) 2.66 postoperatively (mean) |

Benign findings, no malignancy (2), mucinous cystadenocarcinoma (1) | da Vinci X | 85.33 (mean) | 57.66 (mean) | 216.66 (mean) | 3 M | 52.66 (mean) | 10.66 (mean) | Yes (1 patient) | Normal (cT0) | Yes (2 patients) | No recurrence | No | N/A |

| Surgeon (Date) | Institution (Country) | Pre- and Postoperative Hemoglobin (mmol/L) | Reason for Surgery | Symptoms | Imaging Method | Cystoscopy Result | Preoperative TURBT | Lymph Node Involvement | Metastasis | Umbilicus Removal | Lymphadenectomy | Complications | Hospital Stay (Days) | Histopathological Findings | Robotic System | Operation Time (Min.) | Console Time (Min.) | Blood Loss (mL) | Patient Sex | Patient Age | Follow-Up Duration (Months) | Follow-Up Cystoscopy | Follow-Up Cystoscopy Result | Follow-Up CT | Follow-Up CT Result | Adjuvant Therapy | Adjuvant Therapy Details |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drobot RB 15 December 2022 |

Multidisciplinary Hospital in Warsaw-Miedzylesie (Poland) | 9.9 -> 8.4 | Suspected urachal tumor on CT (contrast-enhanced tissue mass) | Chronic suprapubic pain | CT | Normal | No | No | No | No | No | II Clavien Dindo: red blood cell concentrate transfusion | 7 (3 postoperatively) | Tissue fragment measuring 13×5 cm, consisting of adipose tissue, and an adjacent cohesive element measuring 3×2×5 cm. The obfuscated material is not very legible. Urachus without tumor. | da Vinci X | 90 | 55 | 450 | Male | 44 | 20 | No | N/A | Yes | No evidence of pathology | No | N/A |

| Drobot RB 19 October 2023 |

Multidisciplinary Hospital in Warsaw-Miedzylesie (Poland) | 9.5 -> 8.4 | Urachal tumor Shelodon IIIA stage | Suprapubic pain, hematuria | CT | Tumor at the dome of the bladder | No | No | No | No | No | None | 5 (2 postoperatively) | Cystadenocarcinoma mucinosum lesion excised completely (R0). | da Vinci X | 85 | 50 | 150 | Male | 66 | 10 | Yes | Normal (cT0) | Yes | No evidence of recurrence (N0, M0) | No | N/A |

| Drobot RB 12 September 2024 |

Multidisciplinary Hospital in Warsaw-Miedzylesie (Poland) | 9.4 -> 9.1 |

Suspected urachal tumor on CT | Microscopic hematuria | CT | Tumor at the dome of the bladder | No | No | No | No | No | None | 7 (3 postoperatively) | The examined material includes samples of the patent urachus with focal, moderately abundant chronic inflammatory infiltrates; no neoplastic tissue is observed | da Vinci X | 81 | 68 | 50 | Male | 48 | 2 | No | N/A | No | N/A | No | N/A |

| Symptoms | Count (Number) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Hematuria | 26 | 29.89 |

| Abdominal pain | 16 | 18.39 |

| Dysuria | 12 | 13.79 |

| UTI | 8 | 9.20 |

| Irritative LUTS | 8 | 9.20 |

| Umbilical drainage/discharge | 6 | 6.90 |

| Mucosuria | 5 | 5.75 |

| No symptoms | 3 | 3.45 |

| Dyspareunia/dysorgasmia | 2 | 2.30 |

| Obstructive LUTS | 1 | 1.15 |

| Cystoscopy Results | Count (Number) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Bladder dome mass/finding | 20 | 40.38 |

| Normal | 6 | 11.54 |

| Urachal remnant ducts | 5 | 9.62 |

| Bladder wall thickening | 2 | 3.85 |

| Urachal mass | 2 | 3.85 |

| Extrinsic bladder compression | 1 | 1.92 |

| Mixed solid/cystic mass | 1 | 1.92 |

| Mixed solid/cystic mass with calcification | 1 | 1.92 |

| Protruding lesion with normal mucosa | 1 | 1.92 |

| Solid urachal lesion | 1 | 1.92 |

| Supra-vesical cyst | 1 | 1.92 |

| Urachal cyst with inflammation | 1 | 1.92 |

| Cyst with rim-enhancing fluid collection | 1 | 1.92 |

| Urachal remnant mass | 1 | 1.92 |

| Urachal submucosal mass | 1 | 1.92 |

| Margins marked | 1 | 1.92 |

| Mucous discharge | 1 | 1.92 |

| Category | Count (Number) | Percentage (%) | Details (Number) | Detail Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Complications | 34 | 66.67 | ||

| Grade I | 2 | 3.92 | Acute urinary retention (1) Persistent abdominal pain (1) |

1.96 1.96 |

| Grade II | 2 | 3.92 | UTI (1) UTI requiring antibiotics (1) |

1.96 1.96 |

| Grade IIIA | 2 | 3.92 | Bladder leakage (1) Infected hematoma (1) |

1.96 1.96 |

| Grade IIIB | 6 | 11.76 | Fascia rupture (3) Bowel obstruction (1) Abscess reoperation (1) Small bowel perforation (1) |

5.88 1.96 1.96 1.96 |

| Grade IVa | 1 | 1.96 | Urosepsis (1) | 1.96 |

| Grade V | 1 | 1.96 | Arterial occlusion (death) (1) | 1.96 |

| Key Finding | Statistical Significance | Level of Evidence GRADE Approach |

Recommendation Strength | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Imaging method choice is significantly influenced by symptoms. Gross hematuria leads to CT/MRI use, while non-specific symptoms often result in ultrasound. | χ2 = 1761 p < 2.2 × 10−16 |

Low Retrospective cohort studies; low risk of bias but limited by imprecision and study design limitations. |

Strong | Advanced imaging modalities (CT/MRI) should be prioritized for patients with gross hematuria. |

| Imaging method varies depending on adjuvant therapy. CT was more common in patients receiving therapy. | χ2 = 38.51 p = 2.42 × 10−6 |

Low Small retrospective studies and case reports; indirect evidence with inconsistent reporting. |

Weak | CT should be performed before initiating adjuvant therapy for accurate staging. |

| Imaging preferences differ by age. Younger patients (<30 years) favor ultrasound, older patients (>50 years) favor CT/MRI. | χ2 = 1088.7 p < 2.2 × 10−16 |

Low Retrospective data; consistent findings but lacking prospective validation. |

Weak | Imaging modalities should consider the patient’s age, with CT/MRI recommended for older patients due to the higher likelihood of malignant pathologies. |

| Symptom presentation differs by sex: males are more likely to present with gross hematuria, females with non-specific symptoms | χ2 = 74.9 p < 0.05 |

Low Case series and small observational studies; evidence consistent but imprecise |

Weak | Consider advanced imaging for males with gross hematuria to exclude malignancy. |

| Males undergo CT more frequently, while females favor ultrasound evaluations. | χ2 = 33.6 p < 0.05 |

Low Retrospective studies; limited subgroup sizes and lack of prospective validation. |

Weak | The choice of imaging modality should be guided by clinical indications and symptoms, without being influenced solely by the patient’s sex. |

| Cystoscopy findings are more suggestive of malignancy in males compared to females. | χ2 = 65.6 p < 0.05 |

Low Observational studies and case series; statistically significant but constrained by study quality. |

Strong | Male patients with suspicious or undetermined findings on cystoscopy should be prioritized for advanced diagnostic work-up to exclude malignancy. |

| Adjuvant therapy administration is influenced by sex, with males more likely to receive therapy. | χ2 = 7.2 p < 0.05 |

Low Retrospective observational studies; indirect evidence with small sample sizes. |

Weak | Evaluate patient characteristics thoroughly when considering adjuvant therapy. |

| Symptom presentation varies significantly across age groups. Younger patients (<30 years) present non-specific symptoms, while older patients (>50 years) exhibit gross hematuria. | χ2 = 6727 p < 0.05 |

Low Retrospective study design with limited precision and absence of prospective comparative studies. |

Weak | Consider age-related symptom variability when planning diagnostic evaluations. |

| Younger patients undergo surgery for benign conditions; older patients for malignancies. | χ2 = 6700 p < 0.05 |

Low Case series and retrospective cohort studies; limited by study design and data precision. |

Weak | Surgical decisions should consider age-related pathology trends, ensuring malignancies in older patients are appropriately prioritized when clinically indicated. |

| Positive cystoscopy findings are strongly associated with adjuvant therapy administration, and the reason for adjuvant therapy is strongly linked to cystoscopy results. | χ2 = 208.7 p < 2.2e × 10−16 χ2 = 1117 p < 2.2 × 10−16 |

Low Retrospective data; statistically robust but constrained by limited data. |

Strong | Cystoscopy outcomes should guide decisions regarding adjuvant therapy, with positive findings prompting further diagnostic and therapeutic considerations. |

| Adjuvant therapy administration differs by age, with middle-aged patients (50–65 years) most likely to receive it. | χ2 = 793.62 p < 0.05 |

Low Retrospective observational studies; indirect evidence with imprecision due to small sample sizes. |

Weak | Adjuvant therapy decisions in malignant cases should be based on staging and pathology, while acknowledging that middle-aged patients (50–65 years) are more likely to require it due to disease characteristics. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).