1. Introduction

Regenerative dental medicine is rapidly evolving as an interdisciplinary field that merges principles of bioengineering with pharmacological science to restore damaged or diseased oral tissues [

1]. Unlike conventional treatments that aim to manage disease progression, regenerative strategies strive to rebuild tissues at a cellular and molecular level [

2]. These approaches aim to overcome limitations related to donor site morbidity, infection risk, and incomplete healing, all of which are frequently encountered with traditional interventions [

3,

4]. By addressing these limitations, regenerative dentistry has the potential to deliver long-lasting solutions that not only restore form and function but also improve overall oral health and patient quality of life.

One of the key advancements in this field involves the use of autologous and allogeneic stem cells, such as dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs) and periodontal ligament stem cells (PDLSCs), which possess the ability to differentiate into various cell types and promote tissue regeneration [

5]. These stem cells can modulate inflammation, stimulate angiogenesis, and participate in the regeneration of periodontal and endodontic tissues. Their regenerative potential is significantly enhanced when used in combination with biomaterials and bioactive molecules such as growth factors [

6].The combined use of cells, scaffolds, and signaling molecules allows for the development of customized regenerative strategies tailored to specific defects or conditions. This integrated approach has already demonstrated promising results in both laboratory and clinical studies.

Pharmacological agents, including anti-inflammatory drugs, antibiotics, and growth factor enhancers, play a critical role in optimizing the regenerative microenvironment [

7]. These compounds support cell viability, reduce post-surgical complications, and enhance tissue integration. Integrating pharmacology into regenerative dentistry also opens new avenues for personalized treatments, wherein the biochemical needs of each patient can be addressed more precisely [

7]. This synergy between pharmacological modulation and tissue engineering ensures that regeneration is not only structurally successful but also functionally sustainable. Such advances could lead to therapies that are less invasive, more predictable, and better tolerated by patients.

Moreover, recent innovations such as nanotechnology, 3D bioprinting, and bioinspired scaffolds are facilitating more accurate and patient-specific therapies [8-12].These technologies allow for the precise delivery of cells and therapeutic agents, improving the outcomes of regeneration in complex oral environments. As these methods gain traction in both research and clinical settings, they represent a significant step toward the future of personalized and minimally invasive dental care [

13]. This review aims to comprehensively explore these emerging regenerative modalities by synthesizing data from recent experimental and clinical studies. It focuses on the synergistic role of stem cells, pharmacological agents, and advanced biomaterials in dental regeneration, while also addressing current challenges, limitations, and potential future directions in the field.

2. Growth Factors in Dental Regeneration

Growth factors are essential biological mediators that orchestrate various cellular processes including proliferation, differentiation, migration, and matrix synthesis [

14]. In the context of dental regeneration, these signalling proteins are crucial for guiding the behaviour of stem cells and resident tissue cells during healing and tissue remodelling [

15]. Their localized delivery has become a core component of regenerative strategies in both periodontal and endodontic applications [

16]. Among the most widely studied growth factors in dentistry are bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs), fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2), and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF). These molecules function by binding to specific cell surface receptors, initiating signaling cascades that regulate gene expression and cellular behavior [

17]. Their roles span from stimulating angiogenesis to promoting odontoblastic and osteoblastic differentiation, making them invaluable in tissue engineering constructs [

18]. Separating the discussion of these growth factors allows for clearer presentation of their distinct biological roles and clinical applications.

Bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs), particularly BMP2, BMP4, BMP7, and BMP11, are crucial for mineralized tissue formation due to their capacity to induce odontogenic and osteogenic differentiation [

18]. When incorporated into scaffolds, they promote the differentiation of dental pulp stem cells into odontoblast-like cells, facilitating reparative dentinogenesis. BMP2 encourages dental pulp cells to differentiate into odontoblasts, increasing the expression of dentin sialophosphoproteins (DSPPs) at the mRNA level and enhancing alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity, though without affecting cell proliferation [

3]. This differentiation likely occurs via activation of nuclear transcription factor Y signaling. When incorporated into pulp capping materials or collagen matrices, recombinant BMP2 or BMP4 promotes dentin and osteodentin formation in canine models, while BMP7 (osteogenic protein-1) induces dentinogenesis in macaque dental pulp [

18,

19]. BMPs have also been utilized in clinical endodontics for pulp capping and root repair, offering enhanced regenerative outcomes compared to conventional materials [

20]. These findings establish BMPs as central drivers of hard tissue regeneration in dental practice.

Fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2) has demonstrated notable potential in periodontal and pulp tissue regeneration. FGF-2 plays a central role in soft tissue regeneration and angiogenesis [

21]. It promotes early wound healing by targeting specific cellular pathways that accelerate cell proliferation and angiogenesis. In vitro, FGF-2 enhances the migration and proliferation of dental pulp cells without inducing differentiation. However, when combined with transforming growth factor-beta 1 (TGFβ1), FGF-2 induces odontoblastic differentiation and amplifies TGFβ1's effects [

22]. Application of FGF-2 to exposed rat molar pulp accelerates vascular invasion and reparative dentin formation, further supporting its use in vital pulp therapy and tissue engineering scaffolds [

18,

23,

24]. The ability of FGF-2 to synergize with other growth factors underlines its value in combination-based regenerative approaches.

Platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), secreted by activated platelets during injury, plays a key role in angiogenesis, immune cell recruitment, and mesenchymal stem cell proliferation. [

25]. PDGF isoforms (AA, BB, AB, CC, DD) act via PDGFRα and PDGFRβ receptors, facilitating chemotaxis and granulation tissue formation. In dental pulp, PDGF-AB and PDGF-BB increase DSP expression and promote matrix protein synthesis, although they exhibit limited effects on dentin-like nodule formation and may inhibit ALP activity. Despite these limitations, PDGF is instrumental in soft tissue repair and early wound healing, particularly through its effects on cell proliferation and vascular development [

18]. While its impact on hard tissue formation is limited compared to BMPs, PDGF remains a critical component of early healing phases, supporting the vascular and cellular framework necessary for subsequent regeneration [

18].

Together, BMPs, FGF-2, and PDGF represent a powerful toolkit for orchestrating biological responses necessary for dental regeneration. Their integration into scaffolds and delivery systems enhances periodontal regeneration, pulp-dentin complex healing, and bone tissue engineering. While each factor has distinct biological functions, their combined or sequential use may offer synergistic effects, maximizing therapeutic outcomes in regenerative dental procedures. Ongoing research is focused on optimizing their delivery, dosage, and combination strategies to harness their full regenerative potential in clinical practice.

3. Platelet-Rich Plasma in Regenerative Dentistry

3.1. Periodontal Tissue Regeneration with PRP: Defect Geometry, PRP Phenotype, and Activation Chemistry

Regeneration in periodontitis succeeds when early molecular cues are matched to the right defect anatomy and to a preparation of PRP that actually delivers those cues in vivo. The field now has enough signal to connect these layers. On the biologic side, PRP and PRF variants release a tightly choreographed burst of growth factors in the first 72 hours, followed by sustained signals that carry healing forward. On the anatomic side, deeper, narrower, and more contained defects are associated with greater hard-tissue fill and attachment gain by 12 months after regenerative surgery. The bridge between the two is the phenotype of the concentrate and the chemistry used to activate it. Putting these pieces together clarifies when PRP helps, which PRP helps, and why some defects benefit more than others do [26-28].

The earliest hours matter. Across platforms, PDGF and TGF-β1 appear rapidly, with VEGF emerging over days, but the exact tempo depends on how the concentrate is built. In a head-to-head in vitro comparison, leukocyte- and platelet-rich fibrin (L-PRF) released more TGF-β1 than did leukocyte- and platelet-rich plasma (L-PRP) and sustained the release of multiple factors beyond Day 1, while also driving stronger migration of mesenchymal stromal and endothelial cells, a proximate engine for stromal ingress and angiogenesis in periodontal wounds [

27].

Independent devices tracking TGF-β1 and PDGF-AB at 0, 24, 48, 72, and 96 hours confirmed time-dependent release patterns and showed that platelet counts do not linearly predict cytokine levels at each time point, underscoring why the dose, not just the concentration, must be read in terms of kinetics [

26]. Activation chemistry layers on top of this structure. Compared with calcium with low-dose thrombin, calcium alone reshaped the multiplex profile. With standardized bead-based panels for PDGF, TGF, VEGF, IL-1, and MMP-9 at 1, 24, 72 hours and 7 days, single-spin and double-spin preparations exhibited distinct trajectories, and adding thrombin generally increased overall cytokine release over seven days while shortening some signals, such as those of TGF [

28].

Table 1 shows the trial level PRP preparation details that underpin these protocol dependant differences.

Mechanistically, these early cytokine milieus track the clinical prerequisites of periodontal regeneration, including chemotaxis and proliferation of periodontal progenitors, proangiogenic remodeling, and controlled inflammation [

37,

38]. Notably, the leukocyte fraction is not inert. Leukocyte-rich preparations can produce IL-1β and other mediators that shape the inflammatory phase [

27], and liquid PRF lysates have shown the capacity to dampen macrophage IL-6 and COX-2 responses and blunt osteoclastogenesis in vitro, aligning with a more pro-regenerative, less catabolic microenvironment in the early window [

39].

When these molecular programs are deployed into periodontal defects, the geometry becomes the force multiplier. A systematic review and meta-analysis of regenerative surgery stratified by morphology revealed that initial defect depth predicted 12-month radiographic hard-tissue gain and that narrower angles and a greater number of residual walls favoured both radiographic fill and clinical attachment level (CAL) gain. In other words, three-wall intrabony defects outperform two-wall defects, all else being equal [

40].

Table 2 represents 12-month morphology-outcome summary. This morphology provides a contained space that may retain a fibrin scaffold and early PDGF, TGF-β1, and VEGF signals from PRP variants, facilitating cellular recruitment and neovascularization; this is a working mechanistic interpretation that is consistent with the in vitro kinetics and the morphology–outcome association, although it has not been demonstrated as a clinical cause–and-effect pathway [26-28,40]. Calibrated radiographic assessments at 6 to 12 months underpin these morphology-stratified outcomes [

40]. Spiral CT has also been used to quantify periodontal changes in PRP studies of furcation defects at 6 months, albeit in a different defect class [

41].

Effect sizes mirror this coupling of biology and geometry. As a monotherapy against open-flap debridement in intrabony defects, autologous platelet concentrates improved key outcomes, but not all concentrates were equal. A comparative meta-analysis reported that PRF produced the largest pooled gains in CAL and probing depth reduction relative to open-flap debridement, whereas PRP showed the greatest pooled reduction in defect depth, likely reflecting differences in fibrin architecture and growth factor kinetics across phenotypes [

42]. When PRP was used as an adjunct in intrabony surgery, a separate meta-analysis revealed clinically significant advantages for CAL gain and probing depth reduction overall, although the benefit was attenuated when guided tissue regeneration was also used, emphasizing that scaffold-rich approaches can partly substitute for, or mask, the contribution of platelet-derived signals [

30]. These pooled effects are modest at the millimeter scale; however, they are compatible with, and may be explained by, an early chemotactic and proangiogenic milieu generated by PRP and PRF in the first days, with clinical benefits observed at 6--12 months [26-28,30].

The Defect class further refines expectations. In mandibular Grade II furcations, autologous PRP added to open-flap debridement improved clinical and radiographic parameters at six months compared with open-flap debridement alone, yet none of the treated sites converted out of Grade II, highlighting the biological ceiling imposed by furcation anatomy even when growth factor cargo is favorable [

41]. This stands in contrast to three-wall intrabony defects, where containment and wall number consistently track with superior CAL gain and radiographic fill at one year, independent of the specific biomaterials used in the flap procedure [

40]. Together, these data suggest a morphology-aware strategy. Larger, more reliable effect sizes from PRP or PRF for deep, narrow, three-wall defects are expected. In addition, there are often clinically meaningful but limited gains in multiroot furcations unless additional scaffolding or space-making measures are introduced [

40,

41].

Translating bench phenotypes into chairside protocols requires naming the concentrate precisely and choosing activation chemistry intentionally. The widely adopted systems distinguish leukocyte-poor, plasma-based PRP from leukocyte-rich, buffy-coat PRP and from fibrin-rich PRF. Classification frameworks that specify platelet counts, activation methods, and white-cell content make published outcomes comparable and help clinicians reproduce effective regimens in the right defects [

43,

44]. From early signal evidence, two practical inferences surface. First, if the aim is sustained TGF-β1 with strong stromal and endothelial cell recruitment in the first week, L-PRF or PRF-like fibrin constructs are attractive on the basis of in vitro release and migration data [

27]. Second, if a broader early cytokine surge is desired, calcium plus low-dose thrombin activation of PRP, mindful of single- versus double-spin differences, can be leveraged while monitoring the inflammatory profile at more delicate sites [

28]. Both approaches converge on similar clinical endpoints, but their kinetic fingerprints suggest different best fits across defect classes and patient contexts.

periodontal regeneration with PRP is not binary, yes or no. It is a choreography. Early PDGF, TGF-β1, and VEGF pulses over 0 to 72 hours set the stage. The leukocyte content and activation chemistry tune the inflammatory and angiogenic scores. Defect geometry determines how well that score is heard in the wound. In this way, the literature’s mixed findings resolve into a coherent narrative that privileges phenotype-specific PRP in contained intrabony defects for CAL gain, probing depth reduction, and radiographic fill at 12 months, while acknowledging the stubborn anatomy of furcations and the need for precise nomenclature and activation protocols to reproduce success [26-28,30,40-44].

3.2. Alveolar Ridge Preservation and Bone Augmentation with PRP: Angiogenic Indices, Mineralization Kinetics, and Implant Readiness

Ridge preservation is largely set in motion during the early postextraction interval, when the clot architecture, capillary ingrowth, and matrix organization determine how fast the socket transitions toward a mechanically competent scaffold. In this context, platelet concentrates can be read as angiogenic accelerators rather than bulk osteogenic substitutes because their fibrin architecture and cellular cargo govern whether growth factors elute in a burst or a sustained profile, with consequences for endothelial recruitment and granulation quality [

43,

44]. Situating PRP and PRF in this kinetic frame helps explain why some protocols appear to advance “readiness” without altering longer-term plateaus in terms of bone quantity or implant outcomes: they accelerate the vascular phase, which occurs when a site tolerates implant placement and early loading [

28,

45].

Mechanistic data support this kinetic reading. Leukocyte- and platelet-rich fibrin releases more TGF-β1 and does so over a longer interval than does L-PRP or a natural blood clot but more strongly induces the migration of mesenchymal and endothelial cells in vitro, a functional correlate of stromal recruitment and angiogenic potential [

27]. Time-resolved analyses have shown that TGF-β1 and PDGF release from PRP unfolds over hours to days and that release magnitudes are not reliably proportional to platelet counts, indicating that “more platelets always means faster healing” heuristic [

26]. Activation choices are pivotal: calcium-only activation in double-spin, leukocyte-rich PRP sustains VEGF, FGF, and IL-1, whereas adding low-dose thrombin sustains PDGF and VEGF but shortens TGF-β and FGF release in the first week [

28]. These kinetic signatures fit with classification frameworks that distinguish plasma-based, leukocyte-poor outputs from buffy coat–based, leukocyte-rich outputs, each producing different growth factor payloads within distinct fibrin networks likely to influence early granulation and vessel ingrowth [

43].

In this context, the anti-inflammatory and antiosteoclastogenic behavior of liquid PRF provides a mechanistic rationale for the clinically “quiet” soft-tissue appearance that often accompanies sockets augmented with PRF [

39].The translational dividend appears early. In a preclinical delayed-placement model, PRP and even PPP increased 3D bone-to-implant contact at one month, an effect that subsided by three to six months, exactly the trajectory expected from an angiogenesis-first modality that accelerates early osteoid turnover without shifting the ultimate ceiling [

45]. Clinically, alveolar ridge preservation using platelet concentrates yields more new vital bone on histomorphometry than spontaneous healing beyond ten weeks, with no meaningful differences between the PRP and PRF families, in keeping with a shared proangiogenic mechanism expressed through different fibrin architectures [

46]. This favors time-based personalization of implant scheduling: use kinetics knowledge to anticipate earlier radiographic consolidation and then verify site readiness at clinically standard checkpoints, such as micro-CT or radiograph-based assessments near 1–3–6 months in preclinical paradigms coupled with stability checks at placement and loading in clinical protocols [

26,

28,

45].

The benefit is also most visible when the local anatomy is unforgiving. Horizontal and vertical loss is greatest where labial plates are thin or where socket walls are missing, conditions that disrupt scaffold continuity and delay vessel entry. Here, PRF used as a biologically active matrix, with or without a graft, can help preserve contour and improve soft-tissue quality, whereas xenografts and alloplasts alone typically require six to eight months to integrate sufficiently for implant placement [

47]. Although infrabony periodontal defects are not extraction sockets, quantitative synthesis from periodontology reinforces a principle that clinicians already apply: morphology predicts outcomes, with deeper and narrower defects supporting greater hard-tissue fill, reminding us that socket wall integrity conditions how well platelet concentrates can express their angiogenic advantage [

40]. When walls are intact, platelet matrices tend to shift the healing curve earlier; when walls are missing, they can help build a more vascular, granulation-dense bridge that stabilizes grafts until woven bone arrives [

27,

47].

The same pattern appears in the sinus. Systematic reviews of lateral window elevation have reported high short-term implant survival across graft materials without clear differences according to material class, implying that graft choice is rarely the dominant driver of success [

48].Within that constraint, adding APCs to xenografts or alloplasts has been reported to increase early vascularization, reduce inflammation and postoperative pain, and decrease reliance on autogenous bone, which is consistent with an angiogenesis-first mode of action [

49].Contemporary evidence-based reviews emphasize that outcomes reflect surgical technique, residual bone height, and execution of more than a single graft type, which leaves a biologic niche for PRP to accelerate maturation without tying surgeons to a specific scaffold class [

48]. In practice, platelet concentrates appear to shorten the interval to “implantable” rather than redefine the ceiling of how much bone can ultimately form.

Operationally, the platelet phenotype and activation protocol match the defect and scaffold: deploy leukocyte-rich, fibrin-dense matrices when sustained TGF-β1 and cell trafficking are desired; favor calcium-only activation when prolonged VEGF is advantageous in the first days; and expect the clinical gains to present early as better granulation quality, faster radiographic consolidation, greater early bone-to-implant contact, and earlier implant readiness, not necessarily superior long-term survival beyond a year [

27,

28,

43,

45,

46,

48,

49].

3.3. Oral Surgery and Implantology with PRP: Mucosal Barrier Restoration, Nociceptive Modulation, and Early Stability

The most reproducible clinical signal for platelet-rich plasma in oral surgery emerges within the first two postoperative weeks: faster soft-tissue restoration with less pain and swelling, whereas effects on hard-tissue endpoints are smaller and often transient. Positioning PRP as a short-horizon, soft-tissue–focused adjunct helps reconcile mixed findings across the literature. After extraction and periodontal procedures, reviews consistently describe improved early soft-tissue healing, whereas durable gains in bone regeneration and long-term implant outcomes are inconsistent and context dependent; in parallel, early implant stability benefits are most clearly detected when analyses pool platelet concentrates and sample the first month of healing [

50].

This early profile is mechanistically coherent. PRP delivers epithelial-active and prorepair cargos, including EGF together with PDGF, TGF-β, and VEGF, which support re-epithelialization and granulation; broader reviews further note KGF and HGF within platelet derivatives, along with dense-granule mediators that shape the wound milieu [

50,

51], Platelet derivatives also tune innate immunity by steering macrophages toward a proresolving phenotype, a shift linked to lower IL-1β and TNF-α signaling and more orderly inflammatory resolution [

52]. The nociceptive domain is also biologically plausible since platelet mediators such as serotonin and the wider platelet secretome described in molecular reviews provide a rationale for reduced pain trajectories after PRP-augmented procedures [

53]. A complementary pathway is fluid clearance: hemostasis couples to lymphangiogenesis through platelet release and proteolytic activation of VEGF-C, a mechanism that supports lymphatic vessel growth after injury and offers a route for clearing postoperative exudate [

54].

Consistent with this axis, PRP-derived exosomes enhance lymphatic endothelial proliferation and tube formation in vivo and in vitro, and PRP itself shows lymphangiogenic activity in cell systems, providing a mechanistic bridge to clinical observations of reduced swelling early after surgery [

55]. When outcomes are captured with adequate temporal resolution, the clinical readouts align with these mechanisms. In third-molar surgery, randomized and controlled studies reported lower pain and improved mouth opening with PRP by day 7, and trials that tracked swelling documented reductions over the same early window [

56]. At free-gingival graft donor sites, early wound-healing indices and time to epithelial closure improve with PRP, again within the 1–2-week interval, which reflects mucosal migration rather than late bone turnover [

57]. For edema quantification itself, three-dimensional facial scanning provides validated linear and volumetric measures that can standardize swelling endpoints; adopting an area-underthe-curve framework over days 0–7 would complement pain AUC and “days to complete re-epithelialization,” strengthening study comparability without presupposing a treatment effect [

57,

58].

Implantology follows the same early–late distinction. A meta-analysis across platelet concentrates revealed greater implant stability at 1 and 4 weeks and reduced marginal bone loss at 3 months, with effects attenuated by 12 weeks; notably, PRP-only subgroups often yield smaller or nonsignificant early gains, underscoring the protocol sensitivity of these products [

59]. In immediate implants, a randomized trial in which fixtures were pretreated with PRP did not demonstrate greater ISQ at 2 or 4 weeks; group differences emerged later, from 2 months through 12 months, without early esthetic or marginal bone advantages, indicating that any stability benefit in this setting was not present at two weeks [

60]. Similarly, long-term follow-up after maxillary augmentation revealed no sustained clinical or radiographic advantages for PRP, suggesting that the strength of PRP lies in short-term soft-tissue and comfort domains rather than durable osseointegration outcomes [

61]. Earlier reviews converge on the same interpretation: improvements are most evident for early soft-tissue healing and patient-centered recovery, whereas hard-tissue and long-term implant endpoints remain heterogeneous and preparation-dependent [

50],.

Taken together, the most defensible clinical translation of PRP in oral surgery and implantology is to target the first 14 days explicitly. Trials should standardize pain scores and rescue-analgesic use, quantify edema with three-dimensional facial scanning workflows, record days to mucosal closure, and include an early implant stability time point of approximately two weeks to capture short-horizon changes that meta-analyses have detected for platelet concentrates [

59]. In this design space, PRP operates as a mucosal barrier and edema-resolution adjunct with a selective influence on early mechanical stability, whereas the longer-term trajectory of osseointegration and marginal bone remains largely a function of bone biology, loading, and case selection [

59].

4. Platelet-Rich Fibrin in Dentistry

PRF-Guided Oral Tissue Regeneration: Fibrin Architecture, Release Kinetics, and Cross-Indication Outcomes

Platelet-rich fibrin is best understood as a living fibrin scaffold that consolidates the early clot, preserves space, and choresographs the first wave of cellular and vascular ingress. Three converging lines of evidence support that view. First, three-dimensional imaging reveals a continuous fibrin meshwork with graded porosity that entraps platelets and leukocytes in a spatially organized fashion that resembles the extracellular matrix and can host cytokines across the depth of the membrane [

62]. Second, kinetic studies have demonstrated that L-PRF releases growth factors and cytokines over several days rather than minutes, matching the tempo of early wound repair rather than a short burst [

63]. Third, modifying the centrifugation profile to create A-PRF shifts leukocyte and platelet localization toward the distal portion of the clot and increases the presence of neutrophils, which is hypothesized to tune macrophage differentiation within the scaffold during the first healing week [

64]. Together, these data frame PRF not as an inert plug but as a biologically active matrix that couples architecture to a staged, days-long biochemical dialog with the wound milieu [

65].

Because the structure and kinetics are interdependent, the preparation must be standardized and transparently reported. Misreporting revolutions per minute without specifying the rotor radius has long confounded reproducibility, since the relative centrifugal force varies by device geometry and dictates cell partitioning and fibrin densification [

66]. Technical notes now emphasize the exact RCF, spin time, rotor radius and angle, vibrations, and chemistry of blood tubes, with the latter point being more than academic: silica shed from coated plastic tubes can contaminate matrices and shows acute cytotoxicity to periosteal cells in vitro [

67,

68]. Thermal modulation and horizontal centrifugation have emerged as additional levers. Gentle warming of horizontal PRF membranes altered both biological and mechanical behavior in vitro, underscoring how temperature histories should be stated alongside spin parameters [

69]. Equally, timing matters. When RCFs are matched across devices, changing the delay between blood draw, spin, and membrane preparation can modify the morphology, and lowering the g-force may reduce the membrane tensile strength despite similar growth factor release, which cautions against the assumption that “slower is always better” [

70]. Independent mechanical testing confirmed that different protocols yield distinct fiber organizations and viscoelastic behavior; for example, A-PRF+ membranes presented greater porosity with higher traction resistance than L-PRF did, aligning microstructures with functions and making a case for routine tensile characterization in reports [

71]. Taken together, a minimum dataset for PRF studies should include RCF at the clot, spin time, rotor radius and angulation, tube composition, explicit thermal handling, and quality metrics such as membrane mechanics and growth factor release curves [

63,

66,

67,

71].

In periodontology, this “architecture-meets-kinetics” logic translates to measurable clinical gains when protocols are controlled. A network meta-analysis of intrabony defects revealed that PRF was among the top adjuncts for clinical attachment level gain at 6-12 months compared with open-flap debridement and collagen alone, although heterogeneity and risk of bias require cautious interpretation [

72]. For gingival recession, a 12-month split-mouth randomized trial revealed that CAF plus L-PRF achieved root coverage and complete coverage comparable to that of CAF plus connective tissue graft, whereas CTG retained advantages in terms of keratinized tissue width and gingival thickness, outcomes that matter for marginal stability [

73]. A broader meta-analysis focused on A-PRF revealed that the results are promising but uneven, reinforcing the need for standardized preparation and consistent endpoint definitions such as CAL gain and keratinized tissue width at fixed time points [

74]. Importantly, microscopy links back to biology: SEM and confocal work show that membranes with thinner, more oriented fibers and preserved cellularity present larger interfibrous spaces, a configuration plausibly favorable for early cell ingress and vascular sprouting in recession coverage and defect filling [

62,

71].

Oral surgery and implantology provide further tests for translation. In extraction sockets, a randomized controlled trial of solid PRF used as a bioadhesive seal accelerated the healing time course, with earlier epithelial closure and reduced bleeding compared with standard management, which is consistent with a membrane that stabilizes the clot while slowly releasing mediators through the first postoperative week [

64]. For ridge preservation, a three-arm randomized trial reported that titanium-prepared PRF outperformed L-PRF and spontaneous healing at four months in terms of ridge dimensions, bone density, pain reduction, and keratinized tissue width, suggesting that tube chemistry and fibrin cross-linking can alter clinical trajectories as well as laboratory metrics [

75]. In sinus augmentation, a recent systematic review revealed that adding PRF improved the implant stability quotient without clear gains in bone height, a pattern that again matches a scaffold optimizing soft-tissue and early interfacial events more than bulk osteogenesis does [

76].

Regeneration beyond the periodontium tracks the same cadence. In regenerative endodontics for immature necrotic teeth, a network meta-analysis suggested that PRP or PRF scaffolds yield the highest rates of clinical and radiographic success within 12 months, with PRP showing the greatest degree of root lengthening at 6-12 months and overall certainty of evidence being low, which argues for protocol clarity and standardized imaging endpoints such as apical closure, root length, and canal wall thickening [

77]. In oral mucosal disease, randomized trials in oral lichen planus indicate that PRP and i-PRF relieve pain and reduce lesion severity, broadly comparable to corticosteroids, highlighting patient-reported outcomes and recurrence tracking as appropriate metrics for epithelial disorders treated with platelet concentrates [

78].

Across these indications, the throughline is simple and actionable. Fibrin architecture governs transport and cell ingress, release kinetics during early biology, and preparation details determine both processes. When clinical reports pair indication-specific outcomes with explicit, reproducible PRF manufacturing data, the field can finally map the scaffold microstructure and 7- to 10-day mediator release to the milestones that clinicians care about: stable attachment, keratinized tissue, faster socket closure, reliable implant stability, and regenerating pulp‒dentin complexes [

62,

75,

77,

79].

5. Stem Cell-Based Therapies in Dental Regeneration

Stem cells (SCs) are undifferentiated cells that possess an extraordinary ability to proliferate, produce, and differentiate into various somatic cells, both in vitro and in vivo. Within the adult body, different populations of SCs play essential roles in maturation and tissue repair. Their remarkable capacity to generate functionally important physiological cells has led to the investigation of alternative strategies, such as recombinant or primed cells, as potential substitutes [

80,

81].

Stem cell-based therapies have emerged as a cornerstone of regenerative dentistry, offering transformative potential for the restoration of damaged dental tissues. Stem cells possess the unique capabilities of self-renewal and multilineage differentiation, making them ideal for regenerating complex dental structures such as dentin, pulp, periodontal ligament, and alveolar bone [

82]. Tooth loss resulting from periodontal disease, dental caries, or trauma is frequently associated with progressive alveolar bone resorption, particularly in the edentulous regions of the jaw [

83,

84]. Following extraction, the absence of mechanical stimulation leads to atrophy of the alveolar ridge, with the mandible being especially susceptible due to its dense cortical structure and lower vascularity. This resorptive process can significantly compromise the anatomical foundation required for dental implant placement, reducing the volume and quality of available bone [

85].

As a result, there is an increasing clinical demand for advanced regenerative approaches to restore alveolar bone and periodontal structures. Stem cell-based tissue engineering strategies have emerged as a promising solution to address these critical-size defects by promoting osteogenesis and periodontal regeneration. These therapies aim not only to reconstruct lost hard and soft tissues but also to re-establish the functional and esthetic integrity necessary for successful prosthetic rehabilitation [

86].

5.1. Type of Dental Stem Cell and Their Clinical Application in Dentistry

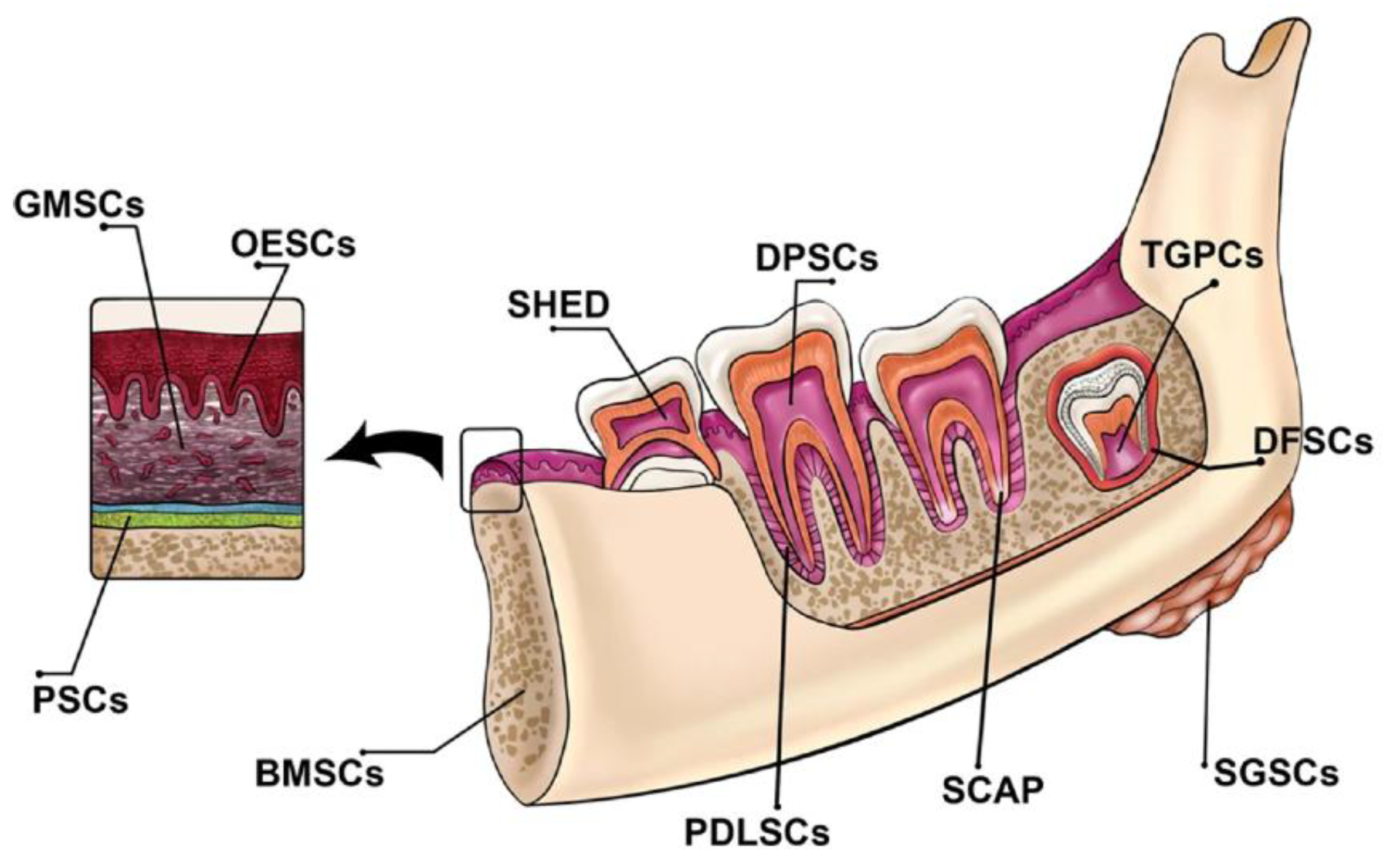

Dental tissues harbor two main types of mature stem cells: Oral Epithelial Stem Cells (OESCs) and Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs), both of which are crucial for tooth tissue regeneration. The dental pulp and periodontal tissues provide favorable environments that encourage the formation of reparative dentin after dental interventions, facilitating the regeneration process. These tissues serve as valuable sources from which MSCs or other stem cells can be harvested.

Dental-derived stem cells encompass Dental Pulp Stem Cells (DPSCs), Dental Follicle Progenitor Cells (DFPCs), Stem Cells from Exfoliated Deciduous Teeth (SHED), Stem Cells from Apical Papilla (SCAP), Tooth Germ Stem Cells (TGSCs), Periodontal Ligament Stem Cells (PDLSCs), Tooth Germ Progenitor Cells (TGPCs), and gingival mesenchymal stem/progenitor cells (GMSCs) (

Figure 1) [

87].

Figure 1 illustrates the various dental tissues that serve as sources for stem cells [

87]

5.1.1. Dental Pulp Stem Cells (DPSCs)

Dental Pulp Stem Cells (DPSCs) are characterized by the positive expression of markers such as CD9, CD10, CD13, CD29, CD44, CD49d, CD59, CD73, CD90, CD105, CD106, CD146, and CD166. These cells can differentiate into various cell types, including osteoblasts, odontoblasts, adipocytes, chondrocytes, neural cells, muscle cells, melanoma cells, and hepatocytes [

87]. DPSCs have great potential for regenerating pulp-dentin tissue, making them useful in treating conditions like pulpitis and dentin defects. Their ability to generate dentin/pulp-like structures in vivo makes them a promising option for dental tissue engineering, offering an innovative alternative to traditional dental treatments. DPSCs could revolutionize regenerative dentistry by addressing challenges in oral and maxillofacial tissue repair [

81].

5.1.2. Dental Follicle Progenitor Cells (DFPCs)

Dental Follicle Progenitor Cells (DFPCs) express markers like CD10, CD13, CD29, CD44, CD59, CD73, and CD105. They have the capacity to differentiate into various cell types such as osteoblasts, adipocytes, chondrocytes, neural cells, cementoblasts, periodontal ligament fibroblasts, and hepatocyte-like cells. DFPCs show promise in enhancing bone strength and regenerating periodontal tissues [

81].

DFPCs have demonstrated potential in bioengineering periodontal tissue on dental implants, suggesting their role in periodontal regeneration. Their ability to differentiate into cementoblasts and osteoblasts further supports their application in tissue engineering. DFPCs are a valuable resource for regenerating tooth roots and addressing clinical challenges in oral and maxillofacial regeneration [

81].

5.1.3. Stem Cells from Human Exfoliated Deciduous Teeth (SHEDs)

Stem Cells from Human Exfoliated Deciduous Teeth (SHEDs) are marked by the positive expression of CD13, CD29, CD44, CD73, CD90, CD105, CD146, CD150, and CD166. These cells can differentiate into osteoblasts, odontoblasts, neural cells, adipocytes, hepatocytes, and endothelial cells, and they show potential in bone and dental tissue regeneration [

87].

SHEDs have exhibited versatility in regenerating various tissues, showing promise in treating conditions like myocardial infarction, muscular dystrophy, cerebral ischemia, and corneal injury. Their capacity to promote neurogenesis and vasculogenesis indicates potential in stroke treatment. Additionally, SHEDs have been effective in repairing large calvarial and mandibular defects, making them a valuable cell source for orofacial tissue reconstruction and regenerative medicine [

81].

5.1.4. Stem Cells from Apical Papilla (SCAP)

Stem Cells from Apical Papilla (SCAP) express markers such as CD24, CD44, CD49d, CD51/61, CD56, CD73, CD90, CD105, CD106, CD146, and CD166. These cells have shown potential in dentin regeneration and pulp tissue repair [

87]. SCAP have proven useful in root development and regeneration, making them an important cell source for addressing oral and maxillofacial clinical challenges. Their ability to differentiate into odontoblast-like cells and form dentin-like tissue both in vitro and in vivo supports their application in dental tissue engineering. Additionally, SCAP have shown promise in neural tissue regeneration, with potential applications in treating neurodegenerative diseases [

81].

5.1.5. Tooth Germ Progenitor Cells (TGPCs)

Tooth Germ Progenitor Cells (TGPCs) are undifferentiated cells found in human third molars, possessing high proliferative capacity and the potential to differentiate into various cell types such as chondrocytes, adipocytes, osteoblasts, odontoblasts, and neurons [

87].

TGPCs have been applied in regenerative medicine, particularly for liver diseases and bone regeneration, making them a valuable resource for tissue engineering and regenerative therapies [

87].

5.1.6. Periodontal Ligament Stem Cells (PDLSCs)

Periodontal Ligament Stem Cells (PDLSCs) express markers such as STRO-1, CD29, CD44, CD73, CD90, CD105, and CD146. They possess the ability to differentiate into bone, cartilage, adipose, neuronal cells, and cementoblasts, which is crucial for periodontal regeneration and tissue engineering [

87]. PDLSCs have shown promise in periodontal regeneration, with studies highlighting their effectiveness in repairing periodontal defects in both animal models and human clinical trials. PDLSCs are also being explored for use in dental implant treatments, offering a potential alternative to traditional osseointegrated implants [

81].

5.1.7. Gingival Mesenchymal Stem Cells (GMSCs)

Gingival Mesenchymal Stem Cells (GMSCs) express markers including CD29, CD44, CD73, CD90, CD105, and CD146. They demonstrate strong potential in periodontal regeneration and wound healing [

87].GMSCs have shown promise in medical applications such as wound healing, tissue regeneration, and bone formation. Their immunomodulatory properties make them effective in treating inflammatory conditions like colitis, contact hypersensitivity, and arthritis in animal models. Additionally, GMSCs have been explored for generating connective tissue-like structures [

87].

5.1.8. Oral Mucosa-Derived Stem Cells (OMSCs)

Oral Mucosa-Derived Stem Cells (OMSCs) are adult stem cells found in the oral mucosa, including gingiva lamina propria and oral epithelial stem cells/progenitors. These cells exhibit self-renewal, clonogenicity, and multipotent differentiation abilities, similar to bone marrow-derived MSCs [

87].OMSCs have been utilized in regenerative medicine for the repair of various oral and maxillofacial tissues, including periodontal, bone, and nerve regeneration [

87].

5.2. The potential of stem cell-based therapies for tissue regeneration in dentistry.

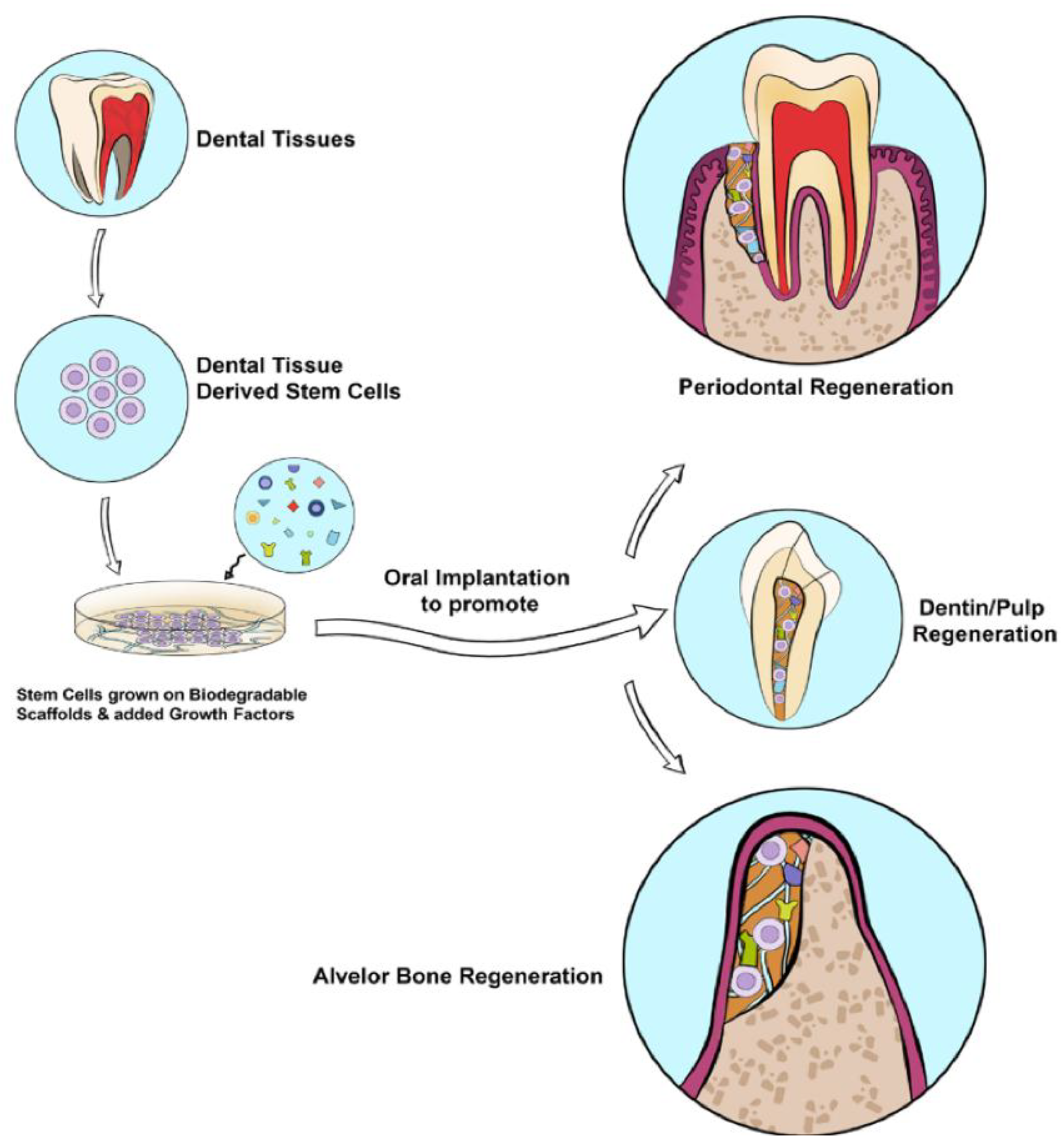

The integration of stem cell biology, growth factor signaling, and scaffold technology has revolutionized the field of regenerative dentistry. Stem cell-based therapies offer a promising approach for restoring damaged or lost dental tissues by harnessing the inherent regenerative potential of stem cells in combination with bioactive molecules and biocompatible scaffolds. These triad components work synergistically to mimic the natural microenvironment, promote cellular differentiation, and guide tissue-specific regeneration.

Among the key components of this strategy, growth factors (GFs) play a pivotal role in modulating cellular behavior. They regulate crucial biological processes such as cell proliferation, chemotaxis, angiogenesis, differentiation, and matrix synthesis. When incorporated into stem cell-based scaffolding systems, GFs significantly enhance the therapeutic outcomes of regenerative dental procedures.

5.2.1. Regeneration of the Dentin-Pulp Complex

In regenerative endodontics, growth factors such as stromal cell-derived factor-1 (SDF-1), granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), transforming growth factor-beta 1 (TGF-β1), and fibroblast growth factor-1 (FGF-1) have demonstrated considerable potential. These growth factors support essential regenerative processes including stem cell recruitment, dentinogenesis, angiogenesis, and neural regeneration. When delivered via biodegradable scaffolds within the root canal system, they facilitate the restoration of the dentin–pulp complex, making them central to next-generation endodontic therapies

(Figure 2) [

87].

A recent comprehensive review evaluated a broad range of in vitro, semiorthotopic, and orthotopic models used to investigate dental pulp regeneration [

88]. The study emphasized the methodological variability across experimental platforms and highlighted how variations in scaffold materials, stem cell types (e.g., DPSCs, SCAP), and growth factor combinations significantly impact outcomes such as pulp-like tissue formation, dentin deposition, vascularization, and neural ingrowth. The review further underlined the importance of model standardization in preclinical research to ensure successful translation of laboratory findings into clinical application [

88].

emerging strategies such as the integration of chitosan–collagen biomembranes embedded with bioactive compounds have shown promise in enhancing the dentinogenic differentiation of dental pulp stem cells. These novel biomaterial systems aim to overcome current limitations in tissue restoration, offering new avenues to improve the efficacy and predictability of regenerative endodontic therapies [

89].

Advanced technologies are further expanding the horizon of dental tissue engineering. 3D bioprinting enables the fabrication of complex, patient-specific tissue constructs with precise spatial control of cells and biomaterials, offering great promise for personalized dental implants and regenerative scaffolds. In parallel, stem cell engineering, including the use of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) and genome-editing tools, is paving the way for scalable and customizable therapies tailored to individual patient profiles [

90].

5.2.2. Periodontal and Alveolar Bone Regeneration

The application of bone morphogenetic proteins (BMP-2 and BMP-7) and enamel matrix derivative (EMD) has led to significant advancements in periodontal tissue engineering. These growth factors support the differentiation of periodontal ligament stem cells (PDLSCs) and dental follicle progenitor cells into osteoblasts and cementoblasts, thereby contributing to alveolar bone regeneration and the reconstruction of periodontal architecture. Combined with appropriate scaffolds, they enhance stability and integration in critical-sized defects (

Figure 2) [

87].

5.2.3. Nerve Regeneration in the Oral Cavity

Regeneration of neural components within oral tissues is essential for restoring sensory function, especially in complex trauma or surgical cases. Growth factors such as nerve growth factor (NGF), brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF), and VEGF have demonstrated neuroprotective and neuroregenerative effects. When embedded in neuro-supportive scaffolds, these factors can stimulate the regeneration and reconnection of oral nerve tissues, paving the way for improved outcomes in dental nerve repair [

87].

Despite the potential shown by techniques utilizing dental pulp stem cells, they often encounter obstacles in achieving complete tissue regeneration [

91]. This limitation can impede the effectiveness of regenerative therapies, leaving gaps in the restoration process and compromising overall treatment outcomes. Moreover, age-related changes in dental tissues may hinder the success of pulp regeneration therapy in older patients.

6. Challenges and Future Directions

Clinical translation of next-generation dental regeneration is slowed by product heterogeneity, geometry-biology mismatch, weak links between bench potency and patient benefit, and uneven trial endpoints, so progress will come from aligning mechanisms, manufacturing, and measurement in one workflow A consolidated overview of the main regenerative approaches, their key components, target tissues, current status, and primary bottlenecks is provided in (

Table 3).

First, standardize platelet and fibrin products with a minimum reporting set that includes relative centrifugal force at the clot, spin time, rotor radius and angle, tube chemistry, activation method and dose, processing delays, temperature history, platelet and leukocyte counts, membrane tensile properties, and 7 to 10 day release curves for PDGF, TGF-β, and VEGF; for example, studies should predefine how calcium-only activation versus calcium plus low-dose thrombin is expected to shape early VEGF or TGF-β kinetics and then verify that profile in vitro. Second, pair every product with mechanism-linked potency assays that prospectively predict clinical benefit, such as endothelial tubulogenesis and macrophage polarization for PRP or PRF, or angiogenic secretome panels for DPSCs, and require prespecified correlations with early human readouts like edema area-under-the-curve, days to mucosal closure, or 2-week implant stability.

Third, design morphology-aware trials that stratify by defect containment and wall number, since deep three-wall intrabony defects are biologically primed for scaffold retention, while furcations often require added space maintenance; sample size and interaction terms should be powered to detect treatment-by-morphology effects. Finally, report scaffold–signal coupling with quantitative targets for stiffness, porosity, degradation, and factor half-times, pursue banked allogeneic cell lines with release criteria tied to those potency assays, and embed adaptive platform trials with 24-month safety surveillance and cost-effectiveness analyses. Together, these steps convert heterogeneous case series into comparable, mechanism-anchored evidence that can scale.

7. Conclusion

Regenerative dentistry stands at the intersection of tissue engineering, cellular therapy, and biomaterials science, offering transformative potential for restoring oral structures lost to disease or trauma. The integration of autologous blood-derived products like PRP and PRF, in combination with targeted growth factors and dental stem cells, has demonstrated promising outcomes in both soft and hard tissue regeneration. Advances in scaffold design, 3D bioprinting, and stem cell engineering, including iPSC technology and gene editing, further enhance the precision and scalability of these therapeutic approaches. However, clinical translation remains challenged by variability in protocols, limited standardization, and regulatory complexities. Future research should focus on optimizing delivery systems, refining biomaterials, and conducting well-structured clinical trials. Through collaborative, interdisciplinary innovation, next-generation therapies can move from experimental frameworks to personalized, evidence-based care in everyday dental practice.

8. Unresolved Questions

Key uncertainties now sit at the interface of kinetics, immunity, and personalization. Can we build bedside assays that read a patient’s early wound chemistry and adjust growth factor delivery in real time, for example a chairside microfluidic that measures PDGF, TGF beta, and VEGF at 24 and 72 hours and recommends an additional membrane or a switch in activation chemistry. What is the minimal synthetic architecture that reproduces PRF like release without donor variability, and can a shelf stable fibrin mimic be tuned to deliver leukocyte derived immunoregulators without provoking fibrosis. Can mechanobiology be harnessed to couple scaffold stiffness and pore topology to macrophage education, so that M1 to M2 transitions are programmed by architecture rather than drugs. How do aging, diabetes, and smoking reshape the early cytokine landscape, and can epigenetic or metabolic preconditioning of DPSCs, PDLSCs, or GMSCs restore youthful secretomes for older patients. Could adaptive platform trials link in vitro potency metrics to early human endpoints with enough fidelity that regulators accept potency as a surrogate for some indications. Can digital twins that integrate defect morphology, patient comorbidities, and secretome profiles predict who benefits from PRF, who requires PRP with calcium only activation, and who needs scaffold reinforcement, and can those models update continuously with postoperative sensor data. Is it possible to print vascularized, innervated pulp dentin constructs that preserve immune surveillance, not only bulk tissue, and to validate function with standardized neurovascular readouts. Finally, what constitutes a universal morphology index for periodontal and alveolar defects that predicts signal retention and space maintenance across centers, and how do we align that index with reimbursement so that smarter case selection is rewarded. These questions are deliberately practical and disruptive, and answering them would raise both the ceiling and the floor of clinical performance.

Authors' contributions

A.Ayad and S.A made the greatest contributions to this narrative review. A.Ayad and S.A defined the review scope and narrative framework, curated and synthesized the literature, and drafted the initial manuscript. Ali.A, S.A.H., Y.H.A., N.A.R.M., S.K.A., and Z.M. contributed to literature curation, content development, and critical commentary during drafting. D.E. provided extensive rewriting and critical revision, improving clarity, coherence, and consistency. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the literature, reviewed and edited the manuscript, approved the final version, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Financial declaration

No external funding was received for this review research paper.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of Data and Material

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation |

Full Name |

| PRP |

Platelet-Rich Plasma |

| PRF |

Platelet-Rich Fibrin |

| BMPs |

Bone Morphogenetic Proteins |

| FGF-2 |

Fibroblast Growth Factor-2 |

| PDGF |

Platelet-Derived Growth Factor |

| VEGF |

Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor |

| TGF-β |

Transforming Growth Factor-beta |

| MSCs |

Mesenchymal Stem Cells |

| DPSCs |

Dental Pulp Stem Cells |

| SCAP |

Stem Cells from Apical Papilla |

| SHED |

Stem Cells from Human Exfoliated Deciduous Teeth |

| PDLSCs |

Periodontal Ligament Stem Cells |

| GMSCs |

Gingival Mesenchymal Stem Cells |

| OMSCs |

Oral Mucosa-Derived Stem Cells |

| NGF |

Nerve Growth Factor |

| BDNF |

Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor |

| G-CSF |

Granulocyte Colony-Stimulating Factor |

| EMD |

Enamel Matrix Derivative |

| BRONJ |

Bisphosphonate-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw |

| MTA |

Mineral Trioxide Aggregate |

References

- Morita, K.; Wang, J.; Okamoto, K.; Iwata, T. The next generation of regenerative dentistry: From tooth development biology to periodontal tissue, dental pulp, and whole tooth reconstruction in the clinical setting. Regen Ther 2025, 28, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, A.M. Guided Tissue and Bone Regeneration Membranes: A Review of Biomaterials and Techniques for Periodontal Treatments. Polymers (Basel) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.D.; Kim, K.H.; Lee, Y.M.; Ku, Y.; Seol, Y.J. Periodontal Wound Healing and Tissue Regeneration: A Narrative Review. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhachko, N.I.; Nespriadko-Monborgne, T.S.; Skrypnyk, I.L.; Zhachko, M.S. IMPROVING DENTAL HEALTH - IS IMPROVING QUALITY OF LIFE. Wiad Lek 2021, 74, 722–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatullo, M.; Zavan, B.; Piattelli, A. Critical Overview on Regenerative Medicine: New Insights into the Role of Stem Cells and Innovative Biomaterials. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawzy El-Sayed, K.M.; El Moshy, S.; Radwan, I.A.; Rady, D.; El-Rashidy, A.A.; Abbass, M.M.S.; Dörfer, C.E. Stem Cells From Dental Pulp, Periodontal Tissues, and Other Oral Sources: Biological Concepts and Regenerative Potential. J Periodontal Res 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okpala, O.E.; Rondevaldova, J.; Kokoska, L. Anti-inflammatory drugs as potential antimicrobial agents: a review. Front Pharmacol 2025, 16, 1557333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunsberger, J.G.; Pandya, P.; Mulligan, M.K.; Marotta, D.; Moroni, L.; Shusteff, M.; Brogan, G.; Brovold, M.; Yoo, J.; Koffler, J.; et al. Review of Disruptive Technologies in 3D Bioprinting. Current Stem Cell Reports 2025, 11, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsuraifi, A.; Mouzan, M.M.; Ali, A.A.A.; Algzaare, A.; Aqeel, Z.; Ezzat, D.; Ayad, A. Revolutionizing Tooth Regeneration: Innovations from Stem Cells to Tissue Engineering. Regenerative Engineering and Translational Medicine 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezzat, D.; Azab, A.; Kamel, I.S.; Abdelmonem, M.; Ibrahim, M.A.; Ayad, A.; Soomro, R.; Wagdy, M.; Eldebawy, M. Phytomedicine and green nanotechnology: enhancing glass ionomer cements for sustainable dental restorations: a comprehensive review. Beni-Suef University Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences 2025, 14, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezzat, D.; Sheta, M.S.; Kenawy, E.-R.; Eid, M.A.; Elkafrawy, H. Synthesis, characterization and evaluation of experimental dental composite resin modified by grapefruit seed extract-mediated TiO₂ nanoparticles: green approach. Odontology 2025, 113, 1148–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsuraifi, A.; Sulaiman, Z.M.; Mohammed, N.A.R.; Mohammed, J.; Ali, S.K.; Abdualihamaid, Y.H.; Husam, F.; Ayad, A. Explore the most recent developments and upcoming outlooks in the field of dental nanomaterials. Beni-Suef University Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences.

- Muskan; Gupta, D. ; Negi, N.P. 3D bioprinting: Printing the future and recent advances. Bioprinting 2022, 27, e00211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belugali Nataraj, N.; Yarden, Y. Growth Factors. 2021.

- Wei, X.; Yang, M.; Yue, L.; Huang, D.; Zhou, X.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Qiu, L.; Huang, Z.; Wang, H.; et al. Expert consensus on regenerative endodontic procedures. Int J Oral Sci 2022, 14, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; De Deus, G.; Kristoffersen, I.M.; Wiig, E.; Reseland, J.E.; Johnsen, G.F.; Silva, E.J.N.L.; Haugen, H.J. Regenerative Endodontics by Cell Homing: A Review of Recent Clinical trials. Journal of Endodontics 2023, 49, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldring, M.B.; Goldring, S.R. Cytokines and cell growth control. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr 1991, 1, 301–326. [Google Scholar]

- Cicciù, M. Growth Factor Applied to Oral and Regenerative Surgery. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Goldman, G.; MacDougall, M.; Chen, S. BMP Signaling Pathway in Dentin Development and Diseases. Cells 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lissenberg-Thunnissen, S.N.; de Gorter, D.J.; Sier, C.F.; Schipper, I.B. Use and efficacy of bone morphogenetic proteins in fracture healing. Int Orthop 2011, 35, 1271–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurogoushi, R.; Hasegawa, T.; Akazawa, Y.; Iwata, K.; Sugimoto, A.; Yamaguchi-Ueda, K.; Miyazaki, A.; Narwidina, A.; Kawarabayashi, K.; Kitamura, T.; et al. Fibroblast growth factor 2 suppresses the expression of C-C motif chemokine 11 through the c-Jun N-terminal kinase pathway in human dental pulp-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Exp Ther Med 2021, 22, 1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.; Khan, A.W.; Kim, M.S.; Choi, S. The Role of Fibroblast Growth Factor (FGF) Signaling in Tissue Repair and Regeneration. Cells 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novais, A.; Chatzopoulou, E.; Chaussain, C.; Gorin, C. The Potential of FGF-2 in Craniofacial Bone Tissue Engineering: A Review. Cells 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimabukuro, Y.; Ueda, M.; Ozasa, M.; Anzai, J.; Takedachi, M.; Yanagita, M.; Ito, M.; Hashikawa, T.; Yamada, S.; Murakami, S. Fibroblast growth factor-2 regulates the cell function of human dental pulp cells. J Endod 2009, 35, 1529–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrae, J.; Gallini, R.; Betsholtz, C. Role of platelet-derived growth factors in physiology and medicine. Genes Dev 2008, 22, 1276–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.-H.; Chen, P.; Chen, A.C.-Y.; Chan, Y.-S.; Hsu, K.-Y.; Lei, K.F. Time-Dependent Cytokine-Release of Platelet-Rich Plasma in 3-Chamber Co-Culture Device and Conventional Culture Well. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 6947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schär, M.O.; Diaz-Romero, J.; Kohl, S.; Zumstein, M.A.; Nesic, D. Platelet-rich concentrates differentially release growth factors and induce cell migration in vitro. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2015, 473, 1635–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, Y.H.; Kim, W.; Park, K.U.; Oh, J.H. Cytokine-release kinetics of platelet-rich plasma according to various activation protocols. Bone Joint Res 2016, 5, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okuda, K.; Tai, H.; Tanabe, K.; Suzuki, H.; Sato, T.; Kawase, T.; Saito, Y.; Wolff, L.F.; Yoshiex, H. Platelet-rich plasma combined with a porous hydroxyapatite graft for the treatment of intrabony periodontal defects in humans: a comparative controlled clinical study. J Periodontol 2005, 76, 890–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Yuan, J.; Aisaiti, A.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, J. The effect of platelet-rich plasma on clinical outcomes of the surgical treatment of periodontal intrabony defects: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Oral Health 2016, 16, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, X.Y.; Qiao, J. Effect of platelet-rich plasma in the treatment of periodontal intrabony defects in humans. Chin Med J (Engl) 2006, 119, 1511–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Döri, F.; Huszár, T.; Nikolidakis, D.; Arweiler, N.B.; Gera, I.; Sculean, A. Effect of platelet-rich plasma on the healing of intrabony defects treated with an anorganic bovine bone mineral and expanded polytetrafluoroethylene membranes. J Periodontol 2007, 78, 983–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christgau, M.; Moder, D.; Wagner, J.; Glässl, M.; Hiller, K.A.; Wenzel, A.; Schmalz, G. Influence of autologous platelet concentrate on healing in intra-bony defects following guided tissue regeneration therapy: a randomized prospective clinical split-mouth study. J Clin Periodontol 2006, 33, 908–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, B.; Sengün, D.; Berberoğlu, A. Clinical evaluation of platelet-rich plasma and bioactive glass in the treatment of intra-bony defects. J Clin Periodontol 2007, 34, 709–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, B.; Okte, E. Treatment of intrabony defects with beta-tricalciumphosphate alone and in combination with platelet-rich plasma. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater 2012, 100, 976–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushick, B.T.; Jayakumar, N.D.; Padmalatha, O.; Varghese, S. Treatment of human periodontal infrabony defects with hydroxyapatite + β tricalcium phosphate bone graft alone and in combination with platelet rich plasma: a randomized clinical trial. Indian J Dent Res 2011, 22, 505–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, G.; Yang, S. Application of platelet-rich plasma with stem cells in bone and periodontal tissue engineering. Bone Res 2016, 4, 16036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacevich, B.M.; Smith, R.D.J.; Reihl, A.M.; Mazzocca, A.D.; Hutchinson, I.D. Advances with Platelet-Rich Plasma for Bone Healing. Biologics 2024, 18, 29–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kargarpour, Z.; Nasirzade, J.; Panahipour, L.; Miron, R.J.; Gruber, R. Liquid PRF Reduces the Inflammatory Response and Osteoclastogenesis in Murine Macrophages. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 636427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nibali, L.; Sultan, D.; Arena, C.; Pelekos, G.; Lin, G.H.; Tonetti, M. Periodontal infrabony defects: Systematic review of healing by defect morphology following regenerative surgery. J Clin Periodontol 2021, 48, 100–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradeep, A.R.; Pai, S.; Garg, G.; Devi, P.; Shetty, S.K. A randomized clinical trial of autologous platelet-rich plasma in the treatment of mandibular degree II furcation defects. J Clin Periodontol 2009, 36, 581–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varshney, S.; Dwivedi, A.; Dwivedi, V. Comparing efficacies of autologous platelet concentrate preparations as mono-therapeutic agents in intra-bony defects through systematic review and meta-analysis. J Oral Biol Craniofac Res 2023, 13, 671–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dohan Ehrenfest, D.M.; Andia, I.; Zumstein, M.A.; Zhang, C.Q.; Pinto, N.R.; Bielecki, T. Classification of platelet concentrates (Platelet-Rich Plasma-PRP, Platelet-Rich Fibrin-PRF) for topical and infiltrative use in orthopedic and sports medicine: current consensus, clinical implications and perspectives. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J 2014, 4, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLong, J.M.; Russell, R.P.; Mazzocca, A.D. Platelet-rich plasma: the PAW classification system. Arthroscopy 2012, 28, 998–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D.; Shujaat, S.; Huang, Y.; Van Dessel, J.; Politis, C.; Lambrichts, I.; Jacobs, R. Effect of platelet-rich and platelet-poor plasma on 3D bone-to-implant contact: a preclinical micro-CT study. Int J Implant Dent 2021, 7, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caponio, V.C.A.; Baca-González, L.; González-Serrano, J.; Torres, J.; López-Pintor, R.M. Effect of the use of platelet concentrates on new bone formation in alveolar ridge preservation: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and trial sequential analysis. Clin Oral Investig 2023, 27, 4131–4146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ucer, C.; Khan, R.S. Extraction Socket Augmentation with Autologous Platelet-Rich Fibrin (PRF): The Rationale for Socket Augmentation. Dent J (Basel) 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Fabbro, M.; Taschieri, S.; Corbella, S. Efficacy of Different Materials for Maxillary Sinus Floor Augmentation With Lateral Approach. A Systematic Review. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res 2025, 27, e70053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malcangi, G.; Patano, A.; Palmieri, G.; Di Pede, C.; Latini, G.; Inchingolo, A.D.; Hazballa, D.; de Ruvo, E.; Garofoli, G.; Inchingolo, F.; et al. Maxillary Sinus Augmentation Using Autologous Platelet Concentrates (Platelet-Rich Plasma, Platelet-Rich Fibrin, and Concentrated Growth Factor) Combined with Bone Graft: A Systematic Review. Cells 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albanese, A.; Licata, M.E.; Polizzi, B.; Campisi, G. Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) in dental and oral surgery: from the wound healing to bone regeneration. Immun Ageing 2013, 10, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, C.; Luo, F.; Hong, G.; Wan, Q. Effects of platelet concentrates on implant stability and marginal bone loss: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Oral Health 2021, 21, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stähli, A.; Strauss, F.J.; Gruber, R. The use of platelet-rich plasma to enhance the outcomes of implant therapy: A systematic review. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2018, 29, 20–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, H.; Pundkar, A.; Shrivastava, S.; Chandanwale, R.; Jaiswal, A.M. A Comprehensive Review on Platelet-Rich Plasma Activation: A Key Player in Accelerating Skin Wound Healing. Cureus 2023, 15, e48943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineda-Cortel, M.R.B.; Suarez, C.G.; Cabrera, J.-T.; Daya, M.; Bonifacio, R.B.L.; Vergara, R.C.; et al. Complexity of Platelet-Rich Plasma: Mechanism of Action, Growth Factor Utilization and Variation in Preparation. Plasmatology 2024, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anitua, E.; Troya, M.; Alkhraisat, M.H. Immunoregulatory role of platelet derivatives in the macrophage-mediated immune response. Front Immunol 2024, 15, 1399130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everts, P.; Onishi, K.; Jayaram, P.; Lana, J.F.; Mautner, K. Platelet-Rich Plasma: New Performance Understandings and Therapeutic Considerations in 2020. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, L.; Bui, H.; Farrelly, O.; Yang, J.; Li, L.; Enis, D.; Ma, W.; Chen, M.; Oliver, G.; Welsh, J.D.; et al. Hemostasis stimulates lymphangiogenesis through release and activation of VEGFC. Blood 2019, 134, 1764–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, B.; Tian, Y.; Guan, M.; Han, W.; Yi, W.; Li, K.; Yang, X.; Niu, Y.; Zhang, B.; Teng, P.; et al. Exosomes derived from platelet-rich plasma alleviate synovial inflammation by enhancing synovial lymphatic function. Journal of Nanobiotechnology 2025, 23, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Cong, X.; Alageel, S.; Dornseifer, U.; Schilling, A.F.; Hadjipanayi, E.; et al. In Vitro Comparison of Lymphangiogenic Potential of Hypoxia Preconditioned Serum (HPS) and Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP). International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, S.R.; Passi, D.; Singh, P.; Sharma, S.; Singh, M.; Srivastava, D. A randomized comparative prospective study of platelet-rich plasma, platelet-rich fibrin, and hydroxyapatite as a graft material for mandibular third molar extraction socket healing. Natl J Maxillofac Surg 2016, 7, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albanese, A.; Licata, M.E.; Polizzi, B.; Campisi, G. Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) in dental and oral surgery: from the wound healing to bone regeneration. Immunity & Ageing 2013, 10, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanif, M.; Sheikh, M.A. Efficacy of platelet rich plasma (PRP) on mouth opening and pain after surgical extraction of mandibular third molars. Journal of Oral Medicine and Oral Surgery 2020, 7, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samani, M.K.; Saberi, B.V.; Ali Tabatabaei, S.M.; Moghadam, M.G. The clinical evaluation of platelet-rich plasma on free gingival graft's donor site wound healing. Eur J Dent 2017, 11, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barone, S.; Zaffino, P.; Salviati, M.; Destito, M.; Antonelli, A.; Bennardo, F.; Cevidanes, L.; Spadea, M.F.; Giudice, A. Automated pipeline for linear and volumetric assessment of facial swelling after third molar surgery. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.A.; Singh, B.P.; Rao, J.; Kumar, L.; Singh, M.; Singh, P.K. Biological and esthetic outcome of immediate dental implant with the adjunct pretreatment of immediate implants with platelet-rich plasma or photofunctionalization: A randomized controlled trial. J Indian Prosthodont Soc 2021, 21, 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attia, S.; Narberhaus, C.; Schaaf, H.; Streckbein, P.; Pons-Kühnemann, J.; Schmitt, C.; Neukam, F.W.; Howaldt, H.P.; Böttger, S. Long-Term Influence of Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP) on Dental Implants after Maxillary Augmentation: Retrospective Clinical and Radiological Outcomes of a Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. J Clin Med 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barone, S.; Bennardo, F.; Salviati, M.; Antonelli, A.; Giudice, A. Evaluation of the usefulness of platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) in mandibular third molar surgery with 3D facial swelling analysis: a split-mouth randomized clinical trial. Head & Face Medicine 2025, 21, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, M.Y.; Wang, C.W.; Wang, J.Y.; Lin, M.F.; Chan, W.P. Three-dimensional structure and cytokine distribution of platelet-rich fibrin. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2017, 72, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Fok, M.R.; Pelekos, G.; Jin, L.; Tonetti, M.S. In Vitro and Ex Vivo Kinetic Release Profile of Growth Factors and Cytokines from Leucocyte- and Platelet-Rich Fibrin (L-PRF) Preparations. Cells 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanaati, S.; Booms, P.; Orlowska, A.; Kubesch, A.; Lorenz, J.; Rutkowski, J.; Landes, C.; Sader, R.; Kirkpatrick, C.; Choukroun, J. Advanced platelet-rich fibrin: a new concept for cell-based tissue engineering by means of inflammatory cells. J Oral Implantol 2014, 40, 679–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohan Ehrenfest, D.M.; Bielecki, T.; Jimbo, R.; Barbé, G.; Del Corso, M.; Inchingolo, F.; Sammartino, G. Do the fibrin architecture and leukocyte content influence the growth factor release of platelet concentrates? An evidence-based answer comparing a pure platelet-rich plasma (P-PRP) gel and a leukocyte- and platelet-rich fibrin (L-PRF). Curr Pharm Biotechnol 2012, 13, 1145–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, K.; You, J.; Zhu, Y.; Li, M.; Chen, S.; Ren, S.; et al. Platelet-rich fibrin as an autologous biomaterial for bone regeneration: mechanisms, applications, optimization. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2024, 12, 1286035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miron, R.J.; Fujioka-Kobayashi, M.; Sculean, A.; Zhang, Y. Optimization of platelet-rich fibrin. Periodontol 2000 2024, 94, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bains, V.K.; Mahendra, J.; Mittal, M.; Bedi, M.; Mahendra, L. Technical considerations in obtaining platelet rich fibrin for clinical and periodontal research. J Oral Biol Craniofac Res 2023, 13, 714–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuki, H.; Isobe, K.; Kawabata, H.; Tsujino, T.; Yamaguchi, S.; Watanabe, T.; Sato, A.; Aizawa, H.; Mourão, C.F.; Kawase, T. Acute cytotoxic effects of silica microparticles used for coating of plastic blood-collection tubes on human periosteal cells. Odontology 2020, 108, 545–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Yu, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X. Effect of thermal manipulation on the biological and mechanical characteristics of horizontal platelet rich fibrin membranes. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, A.B.; Andrade, C.; Li, X.; Pinto, N.; Teughels, W.; Quirynen, M. Impact of g force and timing on the characteristics of platelet-rich fibrin matrices. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 6038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simões-Pedro, M.; Tróia, P.; Dos Santos, N.B.M.; Completo, A.M.G.; Castilho, R.M.; de Oliveira Fernandes, G.V. Tensile Strength Essay Comparing Three Different Platelet-Rich Fibrin Membranes (L-PRF, A-PRF, and A-PRF+): A Mechanical and Structural In Vitro Evaluation. Polymers (Basel) 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, F.; Chauca-Bajaña, L.; Caponio, V.C.A.; Cueva, K.A.S.; Velasquez-Ron, B.; Padín-Iruegas, M.E.; Almeida, L.L.; Lorenzo-Pouso, A.I.; Suárez-Peñaranda, J.M.; Pérez-Sayáns, M. Regeneration of periodontal intrabony defects using platelet-rich fibrin (PRF): a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Odontology 2024, 112, 1047–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavuz, A.; Güngörmek, H.S.; Kuru, L.; Doğan, B. Treatment of multiple adjacent gingival recessions using leucocyte- and platelet-rich fibrin with coronally advanced flap: a 12-month split-mouth controlled randomized clinical trial. Clin Oral Investig 2024, 28, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, M.H.A.; Sabri, H.; Di Pietro, N.; Comuzzi, L.; Geurs, N.C.; Bou Semaan, L.; Piattelli, A. Clinical Indications and Outcomes of Sinus Floor Augmentation With Bone Substitutes: An Evidence-Based Review. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res 2025, 27, e13400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, W.; Abdelhaleem, M.; Elmeadawy, S. Assessing the effectiveness of advanced platelet rich fibrin in treating gingival recession: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanaati, S.; Śmieszek-Wilczewska, J.; Al-Maawi, S.; Neff, P.; Zadeh, H.H.; Sader, R.; et al. Solid PRF Serves as Basis for Guided Open Wound Healing of the Ridge after Tooth Extraction by Accelerating the Wound Healing Time Course-A Prospective Parallel Arm Randomized Controlled Single Blind Trial. Bioengineering (Basel) 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldommari, E.A.; Omair, A.; Qasem, T. Titanium-prepared platelet-rich fibrin enhances alveolar ridge preservation: a randomized controlled clinical and radiographic study. Scientific Reports 2025, 15, 24065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babich, O.; Lugassy, E.; Babich, M.; Abayov, P.; Haimov, E.; Juodzbalys, G. The Use of Platelet-Rich Fibrin in Sinus Floor Augmentation Surgery: a Systematic Review. J Oral Maxillofac Res 2024, 15, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabeti, M.; Ghobrial, D.; Zanjir, M.; da Costa, B.R.; Young, Y.; Azarpazhooh, A. Treatment outcomes of regenerative endodontic therapy in immature permanent teeth with pulpal necrosis: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Int Endod J 2024, 57, 238–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemczyk, W.; Janik, K.; Niemczyk, S.; Żurek, J.; Lynch, E.; Parker, S.; Cronshaw, M.; Skaba, D.; Wiench, R. Use of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) and injectable platelet-rich fibrin (i-PRF) in oral lichen planus treatment: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. BMC Oral Health 2025, 25, 832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]