Submitted:

11 January 2025

Posted:

14 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

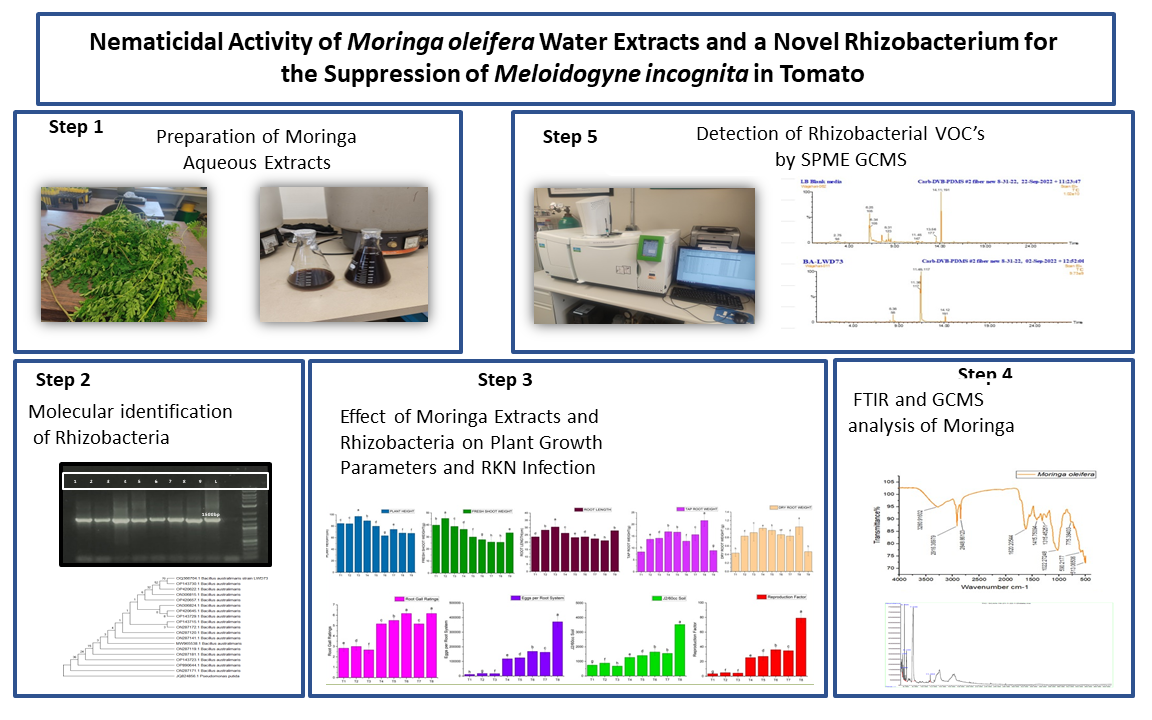

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

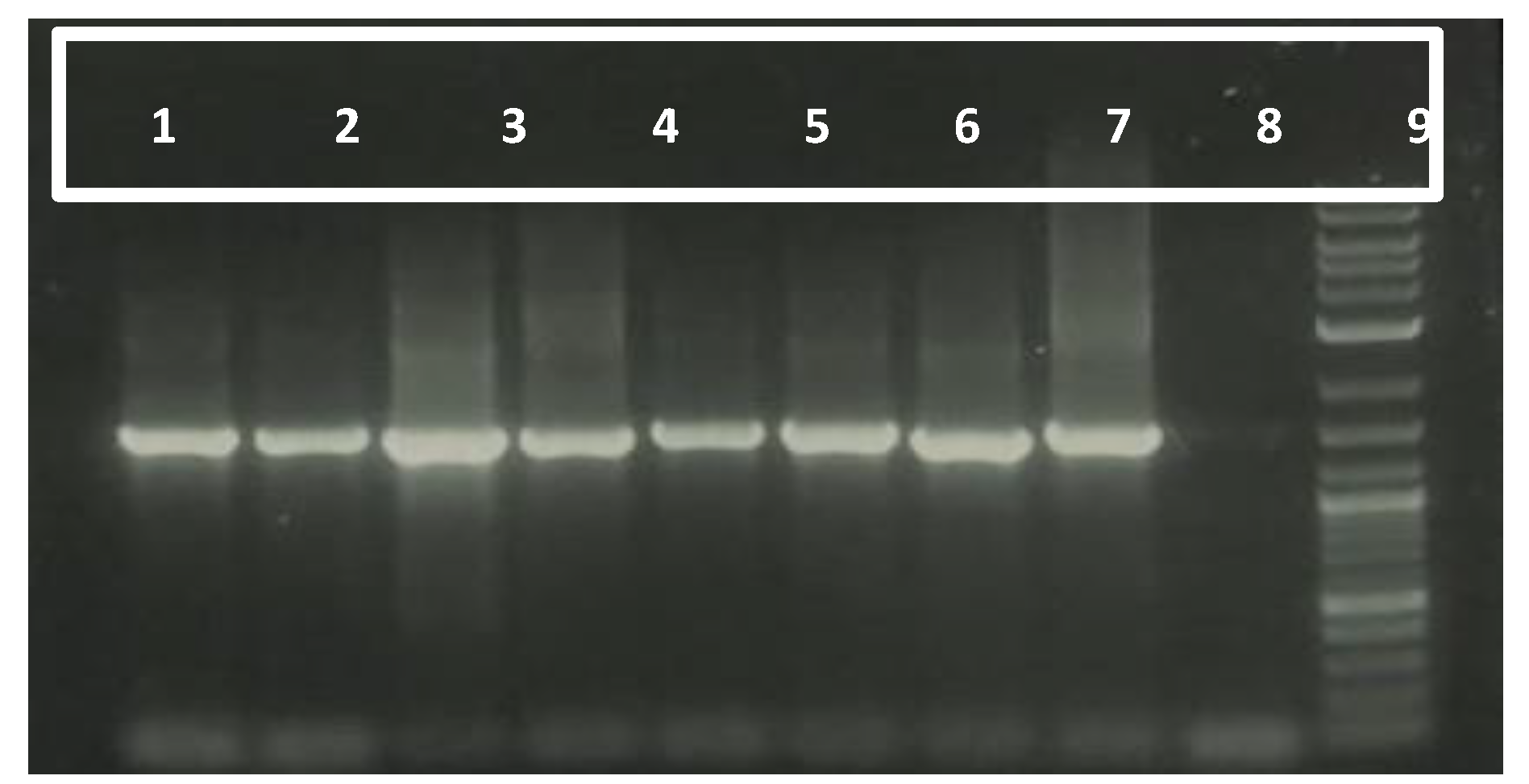

2.1. Molecular Characterization of Rhizobacteria

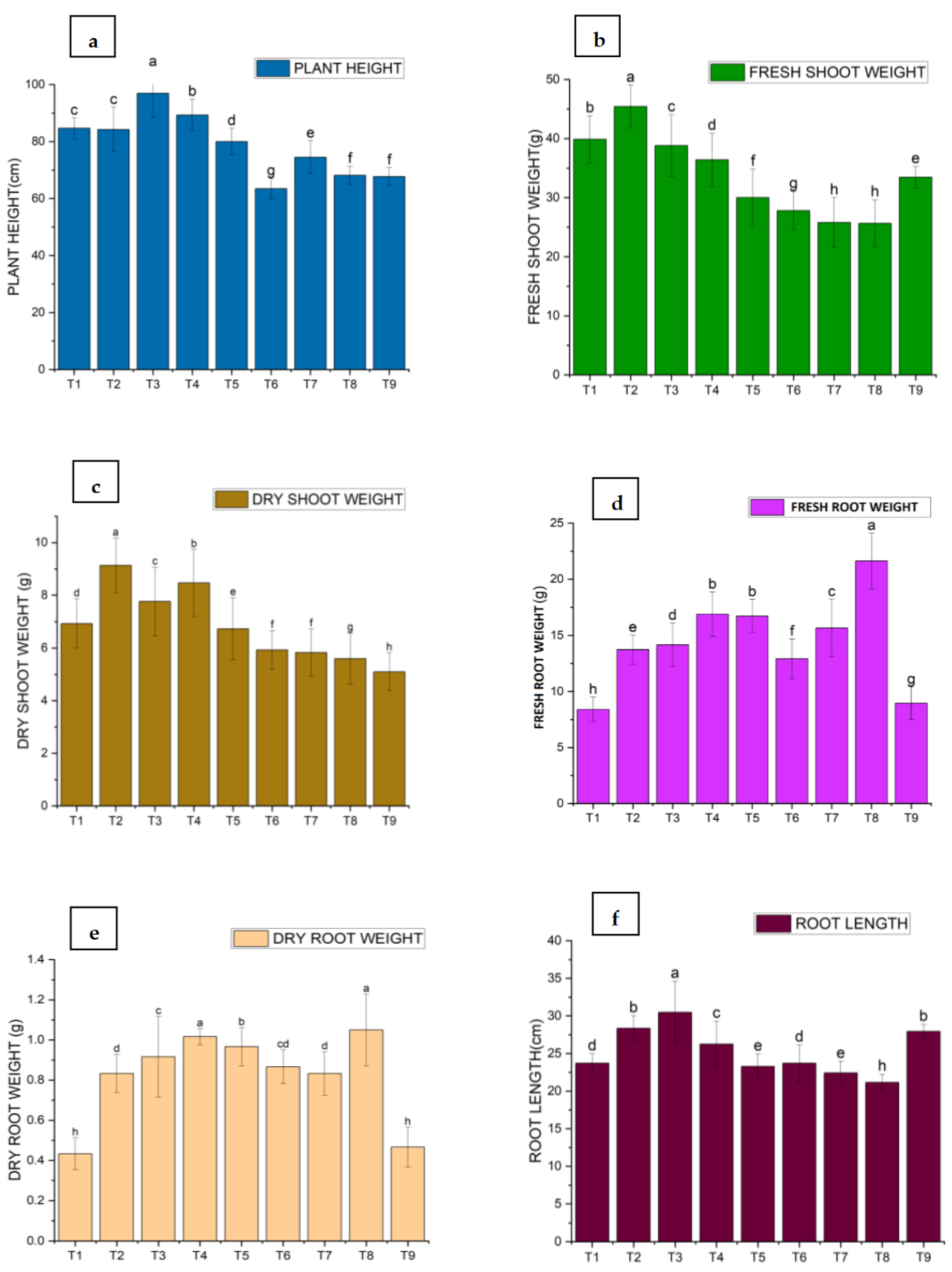

2.2. Effect of Rhizobacteria and Plant Extracts on Plant Growth of Tomato

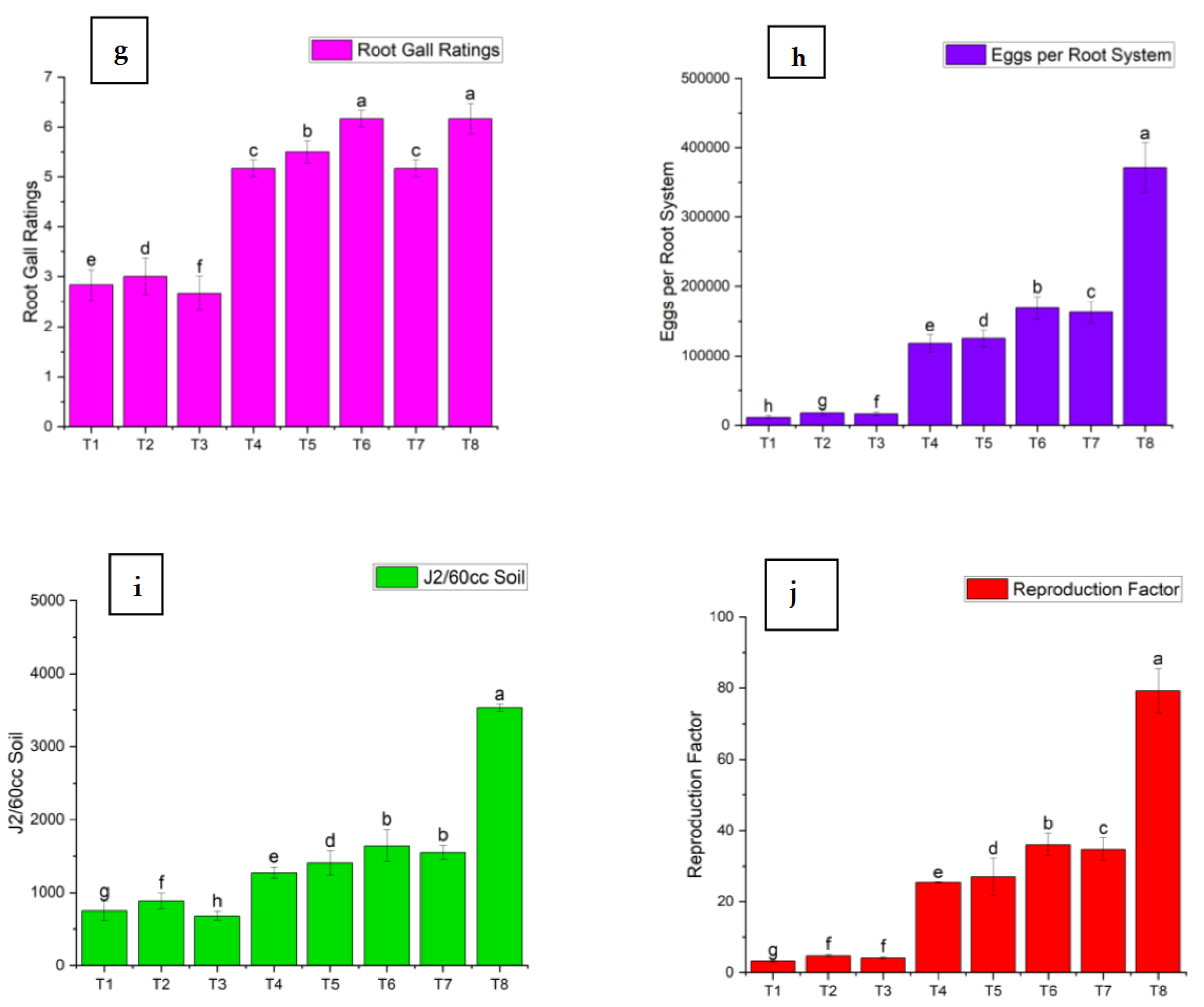

2.3. Effect of Rhizobacteria and Plant Extracts on M. incognita Infection

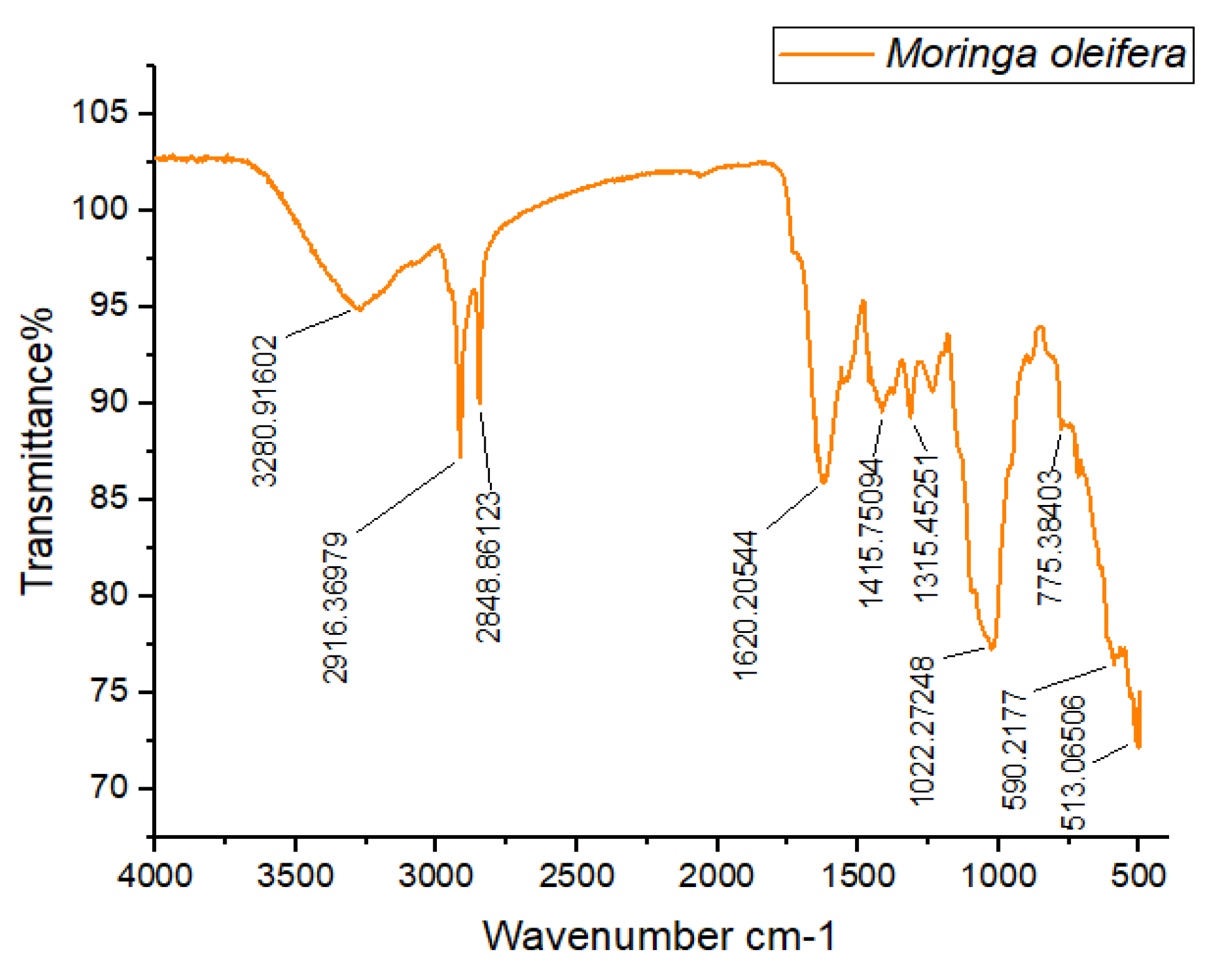

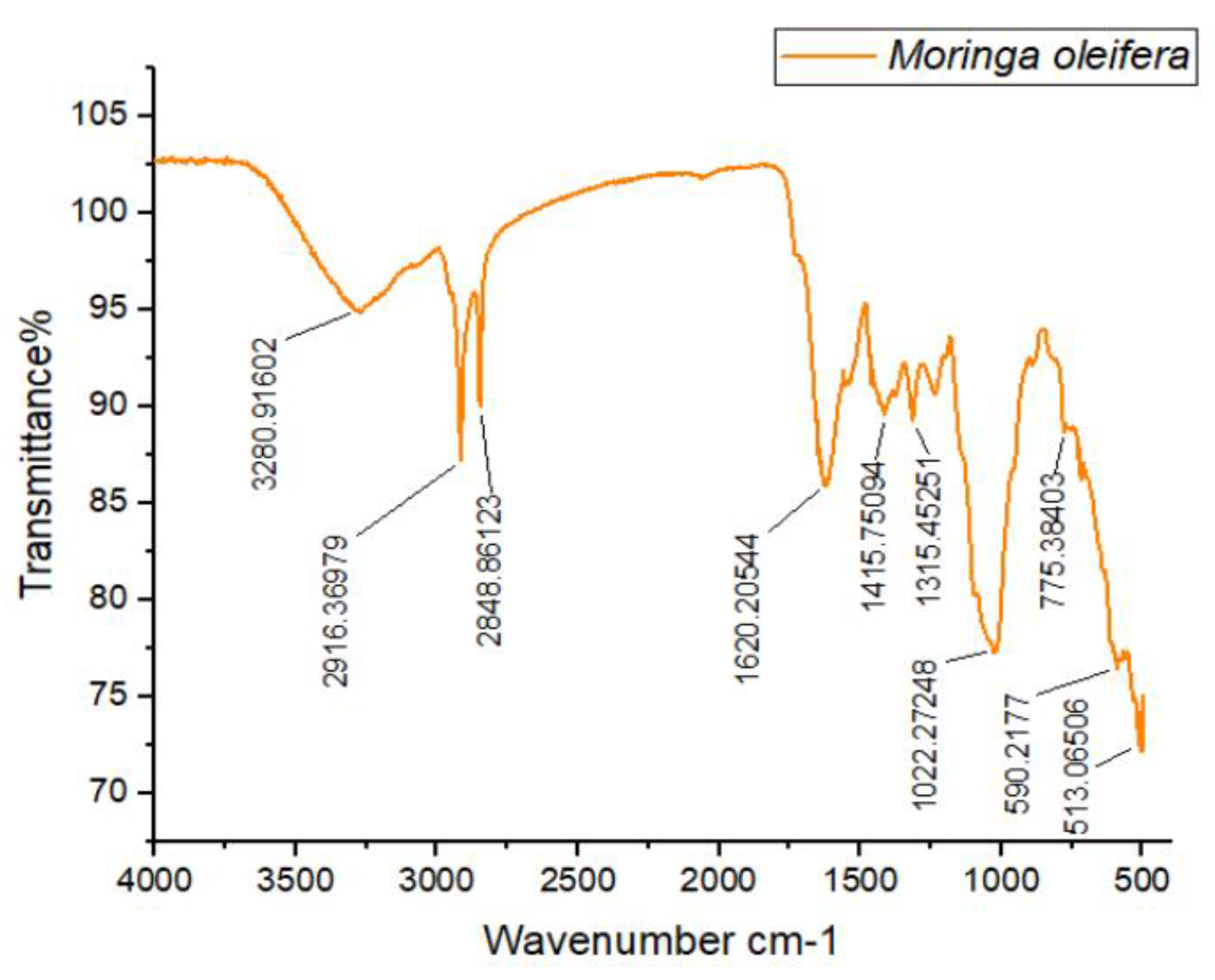

2.4. FTIR and GC-MS Analysis of Aqueous Extracts of M. oleifera

2.5. Detection of VOCs Using SPME-GCMS

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Inoculum Preparation of Nematode

4.2. Preparation of Aqueous Extracts of M. oleifera

4.3. Isolation and Purification of Rhizobacteria

4.4. Molecular Characterization of Rhizobacteria Isolates

4.5. Sub-Culturing and Preparation of Rhizobacteria Suspensions

4.6. Effect of Rhizobacteria and Plant Extracts on Plant Growth and M. incognita Infection

4.7. Detection of Volatile Organic Compounds from Rhizobacteria

4.8. Compound Identification from Plant Extracts

4.9. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Khairy, D. , Refaei, A, and Mostafa, F.: ‘Management of Meloidogyne incognita infecting eggplant using moringa extracts, vermicompost, and two commercial bio-products’. Egyptian J. Agronema., 2021, 20, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Saeed, M. , Mukhtar, T. Root-knot nematodes (Meloidogyne spp.) infecting peach (Prunus persica L.) in the Pothwar region of Pakistan. Journal of Agricultural Science and Technology 2024, 26, 897–908. [Google Scholar]

- Yaseen, I. and Mukhtar, TImpact of sequential and concurrent inoculations of Meloidogyne incognita and Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. vasinfectum on the growth performance of diverse okra cultivars. Plant Protection 2024, 8, 303–313. [Google Scholar]

- Yaseen, I. , Mukhtar, T, Kim, H.-T. and Arshad, B. Interactive effects of Meloidogyne incognita and Fusarium oxysporum f.sp. vasinfectum on okra cultivars. Bragantia 2024, 83, e20230266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, A. and Mukhtar, TRevolutionizing nematode management to achieve global food security goals-An overview. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayub, H.M. , Akram, M, Mehak, A., Ajmal, M., Ilyas, I., Seerat, W., Tatar, M., Ali, A., Sarwar, R., Abbasi, M. and Rahman, A. A preliminary study on the interaction between Meloidogyne incognita and some strains of Pseudomonas son growth performance of tomato under greenhouse conditions. Plant Protection, 2024, 8, 341–350. [Google Scholar]

- Shahid, M. , Gowen, SR., Burhan, M., Niaz, M.Z., Anwar-ul-Haq, M. and Mehmood, K. Differential responses of Meloidogyne sto Pasteuria isolates over crop cycles. Plant Protection 2024, 8, 257–267. [Google Scholar]

- Aslam, N. , Atiq, M, Rajput, N.A., Akram, A., Arif, A.M., Kachelo, G.A., Nawaz, A., Jahangir, M.M., Jabbar, A. and Ijaz, A. Explicating Botanical Bactericides as an Intervention Tool towards Citrus Canker. Plant Protection, 2024, 8, 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Atiq, M. , Malik, L, Rajput, N.A., Shabbir, M., Ashiq, M., Matloob, M.J., Waseem, A., Jabbar, A., Ullah, A., Zawar, R., Majeed, A. Evaluating the efficacy of plant-mediated copper-silver nanoparticles for controlling Cercospora leaf spot in mung beans. Plant Protection 2024, 8, 661–670. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, A. , Abbas, H, Abbasi, W.M., u Rahman, M.S., Akram, W., Rafiq, F. and Murad, M.T. Evaluation of rhizospheric Pseudomonas sfor the management of Fusarium wilt of tomato in Cholistan, Pakistan. Plant Protection 2024, 8, 433–445. [Google Scholar]

- Manzoor, F. , Atiq, M, Aleem, M., Naveed, K., Khan, N.A., Kachelo, G.A., Ali, M.U., Ali, F., Haris, M. and Rajput, N.A. Appraisal of antifungal potential of chemicals and plant extracts against brown leaf spot of soybean caused by Septoria glycine. Plant Protection 2024, 8, 447–455. [Google Scholar]

- Taha, Z.R. , Altaai, AF., Mohammad, T.H., Khajeek, T.R. Efficacy of silver nanoparticles from Fusarium solani and mycorrhizal inoculation for biological control of Fusarium wilt in tomato. Plant Protection 2024, 8, 635–648. [Google Scholar]

- Saeed, M. , Mukhtar, T., and Khan, M.A. Assessment of nematicidal potential of Cannabis sativa and Azadirachta indica in the management of root-knot nematode (Meloidogyne javanica) on peach’, Pak. J. Agric. Sci. 2021, 58. [Google Scholar]

- Azeem, W.; Mukhtar, T.; Hamid, T. Evaluation of Trichoderma harzianum and Azadirachta indica in the management of Meloidogyne incognita in Tomato’. Pak. J. Zoo. 2021, 53, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandagale, P. , Kansara, S, Padsala, J., and Patel, P.: ‘Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria for Sustainable Production of Sugarcane and Rice’, Int. J. Plant Sci., 2024, 36, 298–305. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.-N. , Jiang, C-H., Si, F., Song, N., Yang, W., Zhu, Y., Luo, Y., and Guo, J.-H.: ‘Long-term field application of a plant growth-promoting rhizobacterial consortium suppressed root-knot disease by shaping the rhizosphere microbiota’, Plant Dis., 2024, 108, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbas, M. , Saadedin, S, Suleiman, A. Cloning and overexpression of Zea mays cystatin 2 (ccii) gene in Bacillus subtilis to reduce root-knot nematode infection in cucumber plants in Iraq. Plant Protection, 2024, 8, 621–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.-N. , Jiang, C-H., Si, F., Song, N., Yang, W., Zhu, Y., Luo, Y., and Guo, J.-H.: ‘Long-term field application of a plant growth-promoting rhizobacterial consortium suppressed root-knot disease by shaping the rhizosphere microbiota’, Plant Dis., 2024, 108, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S. , Ramanjini Gowda, P, Saikia, B., Debbarma, J., Velmurugan, N., and Chikkaputtaiah, C.: ‘Screening of tomato genotypes against bacterial wilt (Ralstonia solanacearum) and validation of resistance linked DNA markers’, Australasian Plant Pathology, 2018, 47, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaseen, A. , and Hájos, MT.: ‘Study on moringa tree (Moringa oleifera Lam.) leaf extract in organic vegetable production: A review’, Research on Crops, 2020, 21, 402–414. [Google Scholar]

- Mukhtar, T. , Kayani, MZ., and Hussain, M.A.: ‘Nematicidal activities of Cannabis sativa L. and Zanthoxylum alatum Roxb. against Meloidogyne incognita’, Ind. Crops Prod., 2013, 42, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, A.A. , Shakeel, A, Waqar, S., Handoo, Z.A., and Khan, A.A.: ‘Microbes vs. nematodes: Insights into biocontrol through antagonistic organisms to control root-knot nematodes’, Plants, 2023, 12, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groover, W. , Held, D, Lawrence, K., and Carson, K.: ‘Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria: a novel management strategy for Meloidogyne incognita on turfgrass’. Pest Manag. Sci., 2020, 76, 3127–3138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agisha, V.N. , Kumar, A, Eapen, S.J., Sheoran, N., and Suseelabhai, R.: ‘Broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity of volatile organic compounds from endophytic Pseudomonas putida BP25 against diverse plant pathogens’. Biocontrol Sci. Technol., 2019, 29, 1069–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, D. , Garladinne, M, and Lee, Y.H.: ‘Volatile indole produced by rhizobacterium Proteus vulgaris JBLS202 stimulates growth of Arabidopsis thaliana through auxin, cytokinin, and brassinosteroid pathways’, J. Plant Growth Regul., 2015, 34, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, E.A. , and Nuby, AS.E.: ‘Phytochemical and nematicidal screening on some extracts of different plant parts of egyptian Moringa oleifera L.’, Pak. J. Phytopath., 2022, 34, 293–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anekwe, I.I. , Ifenyinwa, CC., Amadi, E.S., Ursulla, N.N., and Chukwuebuka, I.F.: ‘Characterization of Aqueous Extract of Moringa oleifera Leaves using GC-MS Analysis’. J. Adv. Microbiol., 2023, 23, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W. , Yang, J, Nie, Q., Huang, D., Yu, C., Zheng, L., Cai, M., Thomashow, L.S., Weller, D.M., and Yu, Z.: ‘Volatile organic compounds from Paenibacillus polymyxa KM2501-1 control Meloidogyne incognita by multiple strategies’. Sci. Rep., 2017, 7, 16213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y. , Xu, C, Ma, L., Zhang, K., Duan, C., and Mo, M.: ‘Characterisation of volatiles produced from Bacillus megaterium YFM3. 25 and their nematicidal activity against Meloidogyne incognita’. Eur. J. Plant Pathol., 2010, 126, 417–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybakova, D. , Rack-Wetzlinger, U, Cernava, T., Schaefer, A., Schmuck, M., and Berg, G.: ‘Aerial warfare: a volatile dialogue between the plant pathogen Verticillium longisporum and its antagonist Paenibacillus polymyxa’. Front. Plant Sci., 2017, 8, 278579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R. , Li, G, Zhang, J., Yang, L., Che, H., Jiang, D., and Huang, H.: ‘Control of postharvest Botrytis fruit rot of strawberry by volatile organic compounds of Candida intermedia’, Phytopathology, 2011, 101, 859–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bommarius, B. , Anyanful, A, Izrayelit, Y., Bhatt, S., Cartwright, E., Wang, W., Swimm, A.I., Benian, G.M., Schroeder, F.C., and Kalman, D.: ‘A family of indoles regulate virulence and Shiga toxin production in pathogenic E. coli’, PLoS One, 2013, 8, e54456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.H. , Kim, YG., Kim, M., Kim, E., Choi, H., Kim, Y., and Lee, J.: ‘Indole-associated predator–prey interactions between the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans and bacteria’, Environ. Microbiol., 2017, 19, 1776–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elzey, B. , Pollard, D , and Fakayode, S.O.: ‘Determination of adulterated neem and flaxseed oil compositions by FTIR spectroscopy and multivariate regression analysis’. Food Control, 2016, 68, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, D.; Shahab, S.; Ahmad, M.; Pathak, N. Mahua Oilseed Cake: Chemical Compounds and Nematicidal Potential’: ‘Oilseed Cake for Nematode Management’ (CRC Press, 2024), 81-88.

- Wollum, A. ‘Cultural methods for soil microorganisms’, Methods of soil analysis: part 2 chemical and microbiological properties. 1982, 9, 781–802. [Google Scholar]

- Nikoo, F.S. , Sahebani, N., Aminian, H., Mokhtarnejad, L., and Ghaderi, R.: ‘Induction of systemic resistance and defense-related enzymes in tomato plants using Pseudomonas fluorescens CHAO and salicylic acid against root-knot nematode Meloidogyne javanica’, J. Plant Prot. Res. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, D.P.; Netscher, C. ‘An improved technique for preparing perineal patterns of Meloidogyne spp’, Nematologica 1974, 20, 268–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikoo, F.S.; Sahebani, N., Aminian; Ghaderi, R. Induction of systemic resistance and defense-related enzymes in tomato plants using Pseudomonas fluorescens CHAO and salicylic acid against root-knot nematode Meloidogyne javanica. J. Plant Prot. Res 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tait, E.; Perry, J.D., Stanforth. Identification of volatile organic compounds produced by bacteria using HS-SPME-GC–MS. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 2014, 52, 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Ramanjini Gowda, P.; Saikia, B., Debbarma; Chikkaputtaiah, C. Screening of tomato genotypes against bacterial wilt (Ralstonia solanacearum) and validation of resistance linked DNA markers. Australasian Plant Pathology 2018, 47, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sr. No. | Isolate | Rhizobacteria Identified as | Accesion No. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | W2 | Bacillus australimaris strain LWD73 | OQ366704 |

| 2 | W13 | B. cereus strain HR001 | OQ372951 |

| 3 | W44 | B. thuringiensis strain WAG41 | OQ370579 |

| Peak No. | Compound Name | Molecular Formula | Molecular Weight (g/mol) | Retention Time (Min) | Peak Area (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4(1H)-Pyrimidinone, 2,6-dimethyl | C24H30N2O | 362.5 | 5.310 | 3.02 |

| 2 | Acetic acid, [(aminocarbonyl)amino]oxo | C3H4N2O4 | 132.08 | 5.561 | 3.01 |

| 3 | Maltol | C6H6O3 | 126.11 | 5.705 | 9.58 |

| 4 | 4H-Pyran-4-one, 2,3-dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy-6-methyl | C6H8O4 | 144.12 | 6.155 | 10.30 |

| 5 | 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural | C6H6O3 | 126.11 | 7.636 | 71.76 |

| 6 | 4(1H)-Pyrimidinone, 2-(methylthio)- | C5H6N2OS | 142.18 | 11.364 | 2.32 |

| No. | Compound | Molecular Formula | Retention Time (min) | Molecular Weight (g/mol) |

Peak Area | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2-Nonanone | C9H18O | 8.35 | 142.24 | 215618130 | 6.54 |

| 2 | 1H-Indole | C8H7N | 11.50 | 117.15 | 2882910162 | 87.46 |

| 3 | Tetradecanol | C14H30O | 13.73 | 214.38 | 32564023 | 0.99 |

| 4 | 9-Hexadecenoic acid | C₁₆H₃₂O₂ | 19.00 | 256.42 | 165322864 | 5.02 |

| T1 | M. oleifera + M. incognita |

| T2 | Bacillus aurtralimaris LWD73 + M. incognita |

| T3 | B. aurtralimaris LWD73 + M. oleifera + M. incognita |

| T4 | Bacillus cereus HR001+ M. incognita |

| T5 | B. cereus HR001 + M. oleifera + M. incognita |

| T6 | Bacillus thuringiensis WAG41 + M. incognita |

| T7 | B. thuringiensis WAG41 + M. oleifera + M. incognita |

| T8 | M. incognita only |

| T9 | Healthy Control |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).