1. Introduction

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is responsible for the most common sexually transmitted infection (STI) worldwide. Cervical cancer (CC) is the fourth most common cause of malignancy in women worldwide (representing 6.6% of all female cancers) and the seventh in general, with some differences between countries [

1]. Mortality rates due to cervical cancer in the European Union are as high as 34,000 new cases yearly. Estimates of the rate per 100,000 women vary from 1.2 in Malta to 9.8 in Lithuania [

2]. In Spain, it is estimated that, every year, 1,972 new cases are detected, and 673 deaths occur; that is, approximately, 2 women per day [

3].

Worldwide current estimates indicate that 662,301 women are diagnosed yearly with cervical cancer and 348,874 die from the disease. This accounts for 7.7% of all cancer deaths, representing a high global mortality rate (age-standardized rate: 13.3/100,000). The CC is the fourth most common cause of cancer death in women and the second most common cause of cancer death (12.4%) in women under 65 years of age [

4]. Approximately 90% of deaths from CC occurred in low-income and middle-income countries, with the mortality rate 18 times higher than in high-income countries, highlighting the disparity in healthcare access and prevention strategies [

5]. The high mortality rate from cervical cancer globally could be reduced through a comprehensive approach that includes prevention, early diagnosis, effective screening and treatment programs [

6].

In the last decades, enough scientific evidence has been collected to confirm that infection with the HPV is the key for the appearance of CC, having detected this virus in practically all the CC cases and, in most premalignant lesions (70-90%) [

7]. However, not all HPV infections lead to CC, most of them are transitory with the virus being eliminated in less than two years. The necessary condition for the development of CC is the persistence of HPV DNA in the infected cell. It is important to not only know whether a woman is infected but also which type of HPV is present. For the time being, it is fully confirmed that types 16 and 18 have a predominant role in premalignant lesions and cervical cancer. In a population-based study, Khan et al. [

8] found an incidence at 12 years of follow-up of up to 20% for type 16, 15% for 18 and 2% for other types. Other data coincides in this regard. In a study of 1918 women with a cytological diagnosis of ASC-US (atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance) types 16 and 18 were found in 61% of those with premalignant lesions. Wright et al. [

9] showed that 1 out of 10 women with normal cytology and HPV positive with the genotypes 16 and/or 18 had 35% greater risk of having a premalignant lesion than HPV negative women.

There are also different proposals and protocols for cervical cancer screening using the HPV test as a single and primary test. In many of these, genotyping is considered to be a triage test that is performed selectively in certain cases.

The use of partial genotyping (individualized identification of HPV-16 and HPV-18) and cytology as triage for women infected with the other 12 high risk-HPV (HR-HPV) genotypes in a population-based screening protocol is considered to fulfil the criteria in order to achieve a reasonable balance of disease detection with number of tests and colposcopies. All efforts must be directed towards primary prevention of these genotypes (vaccines) and its detection using selective or partial genotyping in population screening of CC. The aim of this article is to review some virologic aspects of HPV and its relationship with CC screening.

2. Human Papillomavirus (HPV) and Oncogenes

HPVs belong to the

Papillomaviridae family and generally infect skin and mucosae. They have been classified in high (HR-HPV) or low (LR-HPV) risk genotypes depending on their oncogenic capacity [

10,

11]. LR-HPV causes genital warts and other benign skin and mucosae pathologies, and its association with CC is rare. Therefore, from a clinical point of view, only HR-HPV should be detected during screening.

The HR-HPV group includes genotypes 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58 and 59 (

Table 1). Genotypes 68 and 66 are considered of “probable” and “possible”oncogenic risk, respectively; for this reason, they are included in many commercial tests used for the detection of HPV DNA (HPV test) commonly used in clinical practice.

HPV types 16 and 18 caused approximately three quarters of cervical cancer cases across all global regions. HPV types 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58 contributed an additional 15–20% of cases. The remaining 10 causal genotypes caused only about 5% of cases worldwide, with some notable regional variations, including a higher proportion (~4%) for HPV 35 in Africa than in other regions [

12].

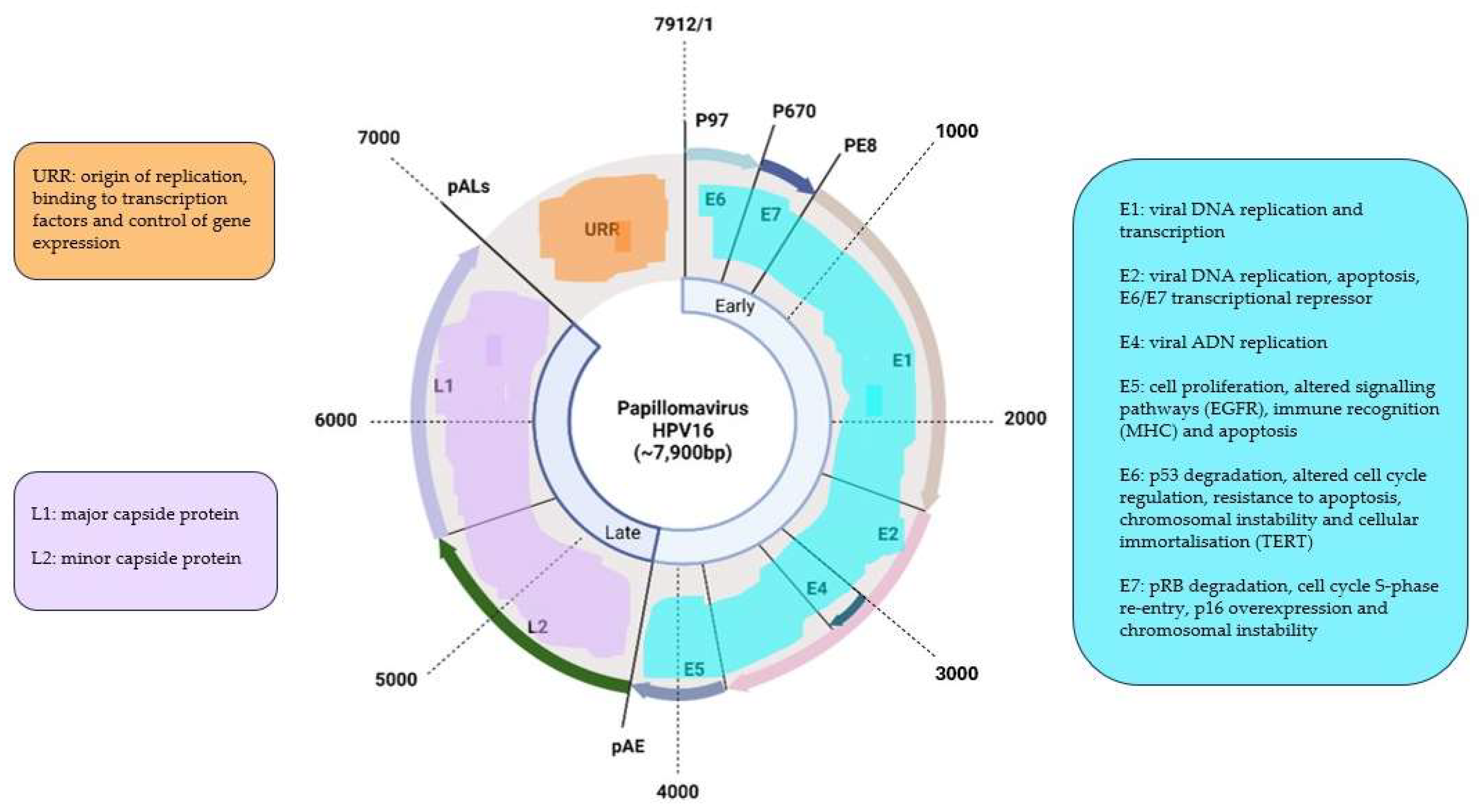

HPVs are small viruses, approximately 50-55nm in diameter, without envelope and with an icosahedral capsid formed by 72 capsomers. Its genome is made up of circular, double stranded, covalently closed DNA of 7500-8000pb in size. This DNA is divided in three regions: 1) E region, of early expression that codifies six structural proteins (E1-E7); 2) L region, of late expression that codifies for two capsid proteins (L1 and L2); and 3) a non-coding regulating region, that has been alternatively named the URR (Upstream Regulatory Region), the LCR (Long Control Region) or the NCR (Non-coding region) and it is situated in the 5’ direction. The early region represents 50% of the genome, the late region 40% and the URR 10% (

Figure 1).

The E1 and E2 proteinsare involved in viral replication, forming a complex that acts as a transcriptional activator of the viral genome [

13]. It also contributes to the maintenance of the virus’ episomic shape and can be absent when viral DNA remains integrated [

14].

The E5 protein is bonded to the membrane and participates in the malign transformation of the cell [

15]. However, its participation is not essential seeing as the E5 gene is frequently deleted in CC cells. It participates in the tumorigenic process by interacting with cell growth factor receptors, including the receptor for the epidermic cell growth factor (ECGF) and, in the case of HPV-6, also with erbB2 and the platelet cell growth factor receptor, interfering with the endocytosis process and inactivating these receptors. E5 also bonds to a porine that participates in the endosomic proton pump, increasing the half-life of the EGF receptor and, therefore, favoring the functional action of EGF in activating the oncogenes

c-fos and

c-jun [

15].

The E6 and E7 proteins play a central role in the malign transformation. Both bond to cellular factors with different affinity depending on the viral genotype, which allows the differentiation between high oncogenic capacity proteins (HR-HPV) and others with little or no transforming ability (LR-HPV).

E6 is a protein that attaches itself to double-stranded DNA. In combination with an associated protein (E6-AP) it bonds to p53, a protein with a key role in the regulation of the cell cycle that is accumulated in the nucleus during the G1 phase of the cell cycle. This protein detects damaged DNA and activates a series of genes that inhibit the progress of the cell cycle or stimulate apoptosis. The p53 protein is degraded by the E6-AP complex using a mechanism linked to ubiquitin. In summary, it consists in a chain reaction in which, after the activation of ubiquitin by the E1 enzyme, the p53 protein bonds to the target protein with the help of a conjugant enzyme (E2 or UBC), which is then bonded to the ubiquitin-protein ligase (E3) and this complex is recognized by the proteasome leading to proteolysis. The E6-AP linked to both, the E6 HPV oncoprotein and p53, acts as an E3 enzyme and leads to degradation of the target protein, p53 in this case, by the proteasome. Protein p53 contributes to the interruption of the cell cycle in phase G1, transactivating the gene WAF1/CIP1, whose p21 protein interacts directly with the cycline/kinase complex depending on cyclines (CDK)/proliferative cells nuclear antigen (PCNA), responsible for the phosphorylation and inactivation of the retinoblastoma protein (pRB) [

16].

The inactivation of p53 is not the only carcinogenesis mechanism induced by E6. It has been observed that the presence of E6 decreases the union capacity of p53 to DNA through mechanisms similar to those used by other oncogenic viral proteins, such as the E1A of adenovirus or the T antigen of the SV40 virus [

16].

Cell cultures have shown the ability of E6 to induce genomic instability, including aneuploidy and amplification [

17]. Telomerase activation by means of E6 on cervical carcinoma cells and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) grade 3 or higher (CIN3+) [

18] has also been proven. This enzyme restores telomeres, contributing to the immortalization of the cell. The existence of a protein that, similarly to what happens with p53, suppresses telomerase activity and is degraded by E6 has been suggested [

19].

The E6 protein can also bond to a calcium-linked protein (E6-BP) associated to apoptosis and cellular differentiation processes. E6 can also behave as a transcription regulator, cooperating along the activated oncogene in the transformation of primary rodent cells [

20]. The transformation of cell cultures infected with viral mutants incapable of degrading p53 has proven the existence of alternative mechanisms capable of making the cell malignant, through the activation of various cellular transcription factors (paxicilline, AP-1, hDLG, IRF-3, Myc, hMCM7, Bak and E6TP-1) and the activation of telomerase [

21].

The protein E7 alters the functionality of pRB, a product of the tumor-suppressing gene Rb-1, that, by bonding to the transcription factor EF-2 and its associated protein DP-1, it slows down the cell cycle in the G1 phase. The E7-pRB bond modifies and inactivates its cell cycle-controlling function. E7 can also bond to the proteins p107 and p130, with similar functions to pRB, and, therefore, inducing the same action. Similarly to E6, E7 regulates the transcription of the ras oncogene in cell cultures and transgenic animals [

22].

The detection of episomic forms of HPV causing CC has stimulated the study of other factors that do not involve the implication of the virus within the cellular chromosome. Thereby, it has been proven that mutations in the fixing locus of the transcription factor YY of the URR segment led to CC progression [

23].

3. HPV Detection Methods: HPV Tests

The most important aspect to consider when deciding the most adequate method for diagnosing and screening CC is that the technique for HPV-DNA detection is widely evaluated and complies with the conditions required in terms of clinical sensitivity. In other words, that it detects as many premalignant lesions, grade 2 or higher cervical malignancies (CIN2+), according to Bethesda classification, as possible [

24]. However, a very high sensitivity generally implies an increase of its non-specifity with important inconveniences for women, such as over-diagnosis, an increase in the number of colposcopies and unnecessary treatments [

25].

Despite the fact that there currently are many commercially available methods for the detection of HPV in cervical samples and most of them fulfill guideline criteria [

26,

27], the only tests approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the detection of HPV-DNA for the screening of CC [

28,

29] are Hybrid Capture 2 HPV DNA test by Qiagen (Hilden, Germany, 2001), Cervista HPV HR test by Hologic (Marlborough, Massachusetts, 2009), Cobas 4800 HPV test by Roche (Basel, Switzerland, 2011), the Aptima HPV assay by Gen Probe (San Diego, California, 2011, purchased by Hologic in 2012), BD Onclarity HPV assay by Becton Dickinson (Franklin Lakes, New Jersey, 2018) and Cobas 6800/8800 HPV test by Roche (Basel, Switzerland, 2020) [

30] (

Table 2).

3.1. Hybrid Capture 2 (HC2)

It was the first to be approved by the FDA (2001) for the detection of carcinogenic genotypes of HPV. The capture of hybrids is the most evaluated method in bibliography. It is a technique based on signal amplification that uses a group of high risk probes, which in the latest version include 13 types of HPV (16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59 and 68) and another group for the low risk HPV including genotypes 6, 11, 42, 43, and 44, thereby detecting any one of these genotypes in only two reactions, bearing in mind that, for CC screening, only HR-HPV should be detected. It does not discriminate the genotype detected. It has some limitations such as the cross-reactivity with many LR-HPV genotypes, leading to false positive results [

31]. Other limitations of this technique include: low levels of HPV infection can result in false-negative results, DNAPap/HC Cervical sampler should not be used for pregnant women, high concentrations of anti-fungal cream, contraceptive jelly, or douche may cause false-negative results if DNA levels are near the assay cutoff, cross-reactivity with the bacterial plasmid pBR322 may give false positive results, if no pellet is observed after centrifugation, the amount of cellular material may not be sufficient, possibly resulting in a false-negative result and PreservCyt Solution specimens containing less than 4 mL after the ThinPrep slides are prepared are considered inadequate [

31]

3.2. Cervista HPV HR

In 2009, the FDA approved the tests Cervista HPV HR and Cervista HPV-16/18 for CC screening. It is a signal amplification technique with Invader technology. It consists of two isothermal reactions, the first one takes places in the DNA sequence of HPV and the second one originates a fluorescent signal. It includes an internal control, the human histone 2 gene. A positive result indicates the presence of one of the 14 HR-HPV genotypes, but it does not specify the genotype present. Cervista® 16/18 identifies HPV-16 and HPV-18 individually. Crossed reactions with LR-HPV are less frequent than in the hybrid capture method mentioned earlier, only exhibits cross-reactivity to 2 HPV types of unknown risk (HPV types 67 and 70) [

32]. The limitations of this technique are: its performance has not been adequately established for HPV-vaccinated individuals, the interference was observed in cervical specimens contaminated with high levels (2%) of contraceptive jelly and/or anti-fungal creams, false-negative results may be obtained under these circumstances, PreservCyt Solution specimens containing volumes less than 2 mL after the ThinPrep Pap test slides are prepared are considered inadequate and high levels of human DNA may create non-specific signal resulting in false-positive results [

33,

34].

3.3. Cobas 4800 HPV test

The Cobas 4800 system (Roche Diagnostics, Manheim, Germany) is completely automatized. It consists of the Cobas X, the Cobas Z thermocycler and the software necessary to carry out a real time PCR with primers of the L1 region of the HPV-DNA. It can process rounds of 22 up to 94 samples and it can carry out 1,344 tests in 24 hours. The primary vial is used, that is, the same as for the liquid cytology test (reflex). Results appear differentiated in four channels: HPV-16, HPV-18, other HR-HPV no-16, 18 (31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 68, 66) and ß-globin, that is used as an internal control in each sample. It has a high clinical sensitivity and it has been evaluated in numerous studies with a high concordance with the results obtained using other techniques of reference. It is important to highlight that no crossed reactions with LR-HPV have been observed in positive results [

35,

36,

37]. The main limitations of this technique are: the performance of the test has not been adequately established in HPV-vaccinated women, the effects of other potential variables including vaginal discharge, use of tampons, or douching have not been evaluated, it has not been validated for specimens that have been previously treated with glacial acetic acid and the concentrations of whole blood in the vial exceeding 1.5% in ThinPrep PreservCyt or 2% in SurePath Preservative fluid (dark red or brown in color) may cause a false-negative result [

38].

3.4. Aptima HPV Assay

The Aptima HPV Assay was approved by FDA in 2011. It is a test that identifies the presence of 14 genotypes of HR-HPV using the viral messenger RNA (mRNA) of oncogenes E6 and E7 in liquid medium cytology. It does not discriminate within the present genotypes. It consists of three steps, capture, amplification using the TMA system, and detection of the products amplified by hybridization. This test also includes an internal control in each step. It can be carried out in Panther, an automatized platform. The studies published show that this test has a similar sensitivity to tests that detect HPV-DNA but a higher specificity, which means it has less false positives. By targeting messenger RNA rather than DNA, the test aims to identify only transcriptionally active virus. This means that positive results are more likely to reflect the presence of squamous intraepithelial lesions because inactive viral DNA incorporated into cells but not driving viral replication will not be detected. The Danish study examined Aptima in addition to HC2 and Roche cobas [

39]. For Aptima, cross-reactivity was seen to types 26, 61, 62, 67, 70, 82, and 83. Twenty-one percent of the cases that did not show CIN2+ on follow-up were attributed to this cross-reactivity. Cross-reactivity to types 26, 67, 70, and 82 was also seen in testing of the assay performed during development. The limitations of this technique are: non-cervical specimen types have not been evaluated, performance has not been evaluated for HPV-vaccinated individuals, personal lubricants that contain polyquaternium 15 may interfere with the performance of the assay when present at concentrations greater than 0.025% (v/v or w/v) of a test sample, Anti-fungal medications that contain tioconazole may interfere with the performance of the assay when present at concentrations greater than 0.075% (w/v) of a test sample and the effects of other potential variables such as vaginal discharge, use of tampons, douching, and so on, and specimen collection variables have not been evaluated [

39].

3.6. BD Onclarity HPVAssay

The BD Onclarity HPV Assay was FDA approved in early 2018. BD Onclarity HPV is a fully automated real-time PCR DNA amplification technique. It uses a desktop device (Viper LT) based on Strand Displacement Amplification (SDA) technology with real-time PCR. It is novel in three aspects: it amplifies the E6/E7 region, which could theoretically avoid false negatives due to cleavage of the L1 region during genome integration. Furthermore, it reports the genotypes requested by the user for each sample avoiding unnecessary information and expense: it can report 6 genotypes individually and can also give results for 3 combinations of other genotypes. Finally, the reagents do not require refrigeration and come ready to use. Unlike most of the other FDA-approved assays, this test has been evaluated for HPV-vaccinated individuals. The sensitivity is lower (80%) and the specificity is higher (52.1%) in vaccinated women compared with unvaccinated women (100% and 46%, respectively) [

40]. The limitations of this assay are: non-cervical specimen types have not been evaluated, performance has not been evaluated in women with prior ablative or excisional therapy or who are pregnant, false negative results may occur for specimens containing >8% (v/v) mucin, > 7% (w/v) acyclovir cream, or >8% (w/v) clindamycin vaginal cream and

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2213294519300985?via=ihubeffects of other variables such as vaginal discharge, tampon use, douching, and so forth, and specimen collection variables have not been evaluated [

40].

3.5. Cobas 6800/8800 HPV Assay

The cobas 6800/8800 HPV Assay was most recently FDA approved in early 2020. Cobas HPV for use on the cobas 6800/8800 Systems is an automated qualitative in vitro test for the detection of HPV DNA in patient specimens. The test utilizes amplification of target DNA by the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and nucleic acid hybridization for the detection of 14 HR-HPV types in a single analysis. The test specifically identifies HPV16 and HPV18 while concurrently detecting the other high risk types (31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 66, and 68) at clinically relevant infection levels. Specimens are limited to cervical specimens obtained by endocervical brush/spatula or cervical brush and preserved in ThinPrep Pap Test PreservCyt solution. Limitactions of this technique include: the performance of the assay has not been validated for use with other collection media and/or specimen types. Use of other collection media and/or specimen types may cause false positives, false negatives or invalid results. Products containing carbomers, including vaginal lubricants, creams and gels, may interfere with the test and should not be used before or during the collection of cervical specimens. The use of commercially available products such as Replens, RepHresh vaginal gel and the RepHresh Clean Balance kit has been associated with false negative results. And finally, the use of metronidazole vaginal gel has been associated with false negative results [

41].

4. Population-Based Screening of CC: Cytology versus HPV Test

At this moment, there is a unanimous agreement that CC screening should be organized and population-based instead of an opportunistic screening as it is being done in some countries and in some regions. Most experts conclude that opportunistic screening, which only acts as a solution for the individual woman that demands it, is “ineffective, inefficient and non-equitable” [

3] and that it should be substituted for organized screenings in every country. As for the initial test, it is recognized that cervical cytology has been very effective over the years, reducing in 70-80% the incidence and mortality of CC as long as the adequate coverage is achieved [

42]. Nonetheless, bearing in mind the scientific evidence, it is widely accepted by experts without any doubt, that the test for HPV should take the place of the cytology as the initial test in CC screening, seeing as it is more sensible, more easily reproducible, less subjective and, according to published data, it is estimated that it prevents a larger number of cases of CC, approximately 32%, providing 60-70% more protection against CC than the cytology [43-45].

Other studies such as that by Cuzick et al. [

46] endorse this change seeing as they confirm that cytology has a very low sensibility in detecting precancerous lesions when compared to HPV tests (53.0% versus 96.3%) although it is less specific (96.3% versus 90.7%). Moreover, other authors also confirm that cytology lacks reproducibility, that is to say, it is considerably subjective [

47].

The most important aspect that has been taken into account for the recommendation of substituting cytology for the HPV test is that it has been proven that the latter has a high positive predictive value (PPV) for detecting CIN2+ lesions, but specially, it has a very high negative predictive value (NPV), close to 100%. This means that if the test has a negative result, this woman has almost null possibility of developing precancerous lesions in a period of, at least, 5 years [

48]. Katki et al. [

49] also confirmed these results. They found that after a negative HPV result the risk of CIN2+ is sufficiently low to return to 5-year routine screening. Other authors found that a negative HPV test allows the screening interval to be increase to 5-6 years [

50]. As a triage test, cytology in HPV positive women is the currently recommended method following the Health Technology Report by Ronco et al. [

51] and the Health Council of the Netherlands recommendations [

52]. The US-American guidelines [

53] recommend HPV test plus cytology every 5 years based on some evidence that the addition of the HPV test to cytology increase the detection of CIN3. However, co-testing (HPV test plus cytology) is not recommended anymore in the European guidelines. These emphasize that a screening policy and a well-organized program are essential in addition to the HPV test for a population-based screening.

In 2014, Australia was the first country to transition from cytology to HPV test as the initial test in its CC population-screening campaign. The Netherlands also implemented it recently, with Health Authorities having chosen the automatic system Cobas 4800 (Roche Diagnostics) using the same vial for liquid cytology. In addition to these countries, the Spanish Society of Gynecology and Obstetrics suggests [

3] in its Consensus Document of 2023, that HPV test should be used as a first line test in CC screening.

5. Why Should We Change the Approach for CC Screening?

Firstly, because the handling of screened women must be carried out according to the risk of finding premalignant lesions or the existence of a high probability of developing them in the following years, before the next screening round. The main aim of a correct screening is to identify all those healthy women with CIN2+ lesions that will progress to cancer and not those that will regress. As mentioned before, cytology has been very effective in reducing notably CC incidence, but it lacks the sensitivity necessary to detect some precancerous lesions and, especially, adenocarcinomas whose incidence has increased in the last few years [

54].

Secondly, we must consider that the HPV test has all the conditions necessary to be used as a first line in population screening. On top of being objective, easy to perform and completely automatized, it has a sensitivity higher than that of the cytology in detecting present CIN2+ lesions and a NPV close to 100% (See section

Population-based screening of CC: cytology versus HPV test). With this, screening rounds would be limited to 5-7 [

49,

50], depending on the starting age or the protocols adopted by different countries. The influence in cost is also important, according to existing studies.

Finally, the weakness of the HPV test should also be considered: its specificity is lower than that of the cytology. This low specificity raises concerns about the excess of colposcopies and over-treatment [

53] but it also depends on the evaluation strategies and screening algorithms. As a result of the loss of specificity when using a HPV test as a first line test, a triage test is necessary in order to prevent women from going through colposcopies and unnecessary treatments. Dalla Palma et al. [

25] clearly demonstrated that the probability of unnecessary treatment increases with the decrease of positive predictive value of colposcopy referral. The triage test suggested in the guide by the Spanish Society of Gynecology and Obstetrics [

3] is the cytology, which has also been used in The Netherlands and in the countries with the most experience and efficacy in population screening [

55]. However, several studies evaluate other options with positive results, such as partial genotyping (separate detection of genotypes 16 and 18) or dual staining, albeit the latter still requires more studies to endorse the positive results [

56].

Having chosen partial genotyping of HPV-16 and HPV-18 is a consequence of the importance of the persistence of genotypes HPV-16 and HPV-18 in the development of premalignant lesions. One of the first studies, by Khan et al. [

8], proved that the accumulated incidence of CIN3+ after 12 years of monitoring is of 20% when HPV-16 is detected, 15% when HPV-18 is detected and only 2% if the result is positive for genotypes HR-HPV no16, 18. Another recent study with similar conclusions is the ATHENA [

57], whose major result was the approval of the Cobas 4800 system by the FDA for use in CC population screening. This study conducted in the US included 42,209 women and its conclusions clearly confirmed the importance of detecting the presence of genotypes 16 and 18 in cervical scrapings and, furthermore, the clinical implications of differentiating them from other HR-HPV no16, 18. The most concluding results were that women with negative cytology but positive results to HPV-16 or HPV-18 have an absolute estimated risk of developing CIN3+ in the next 3 years of 9.8%. On the other hand, if the genotype present is HR-HPV no16, 18, the risk decreases to 2.4% (

Table 3). Similar data have been obtained in studies carried out by European authors [

58].

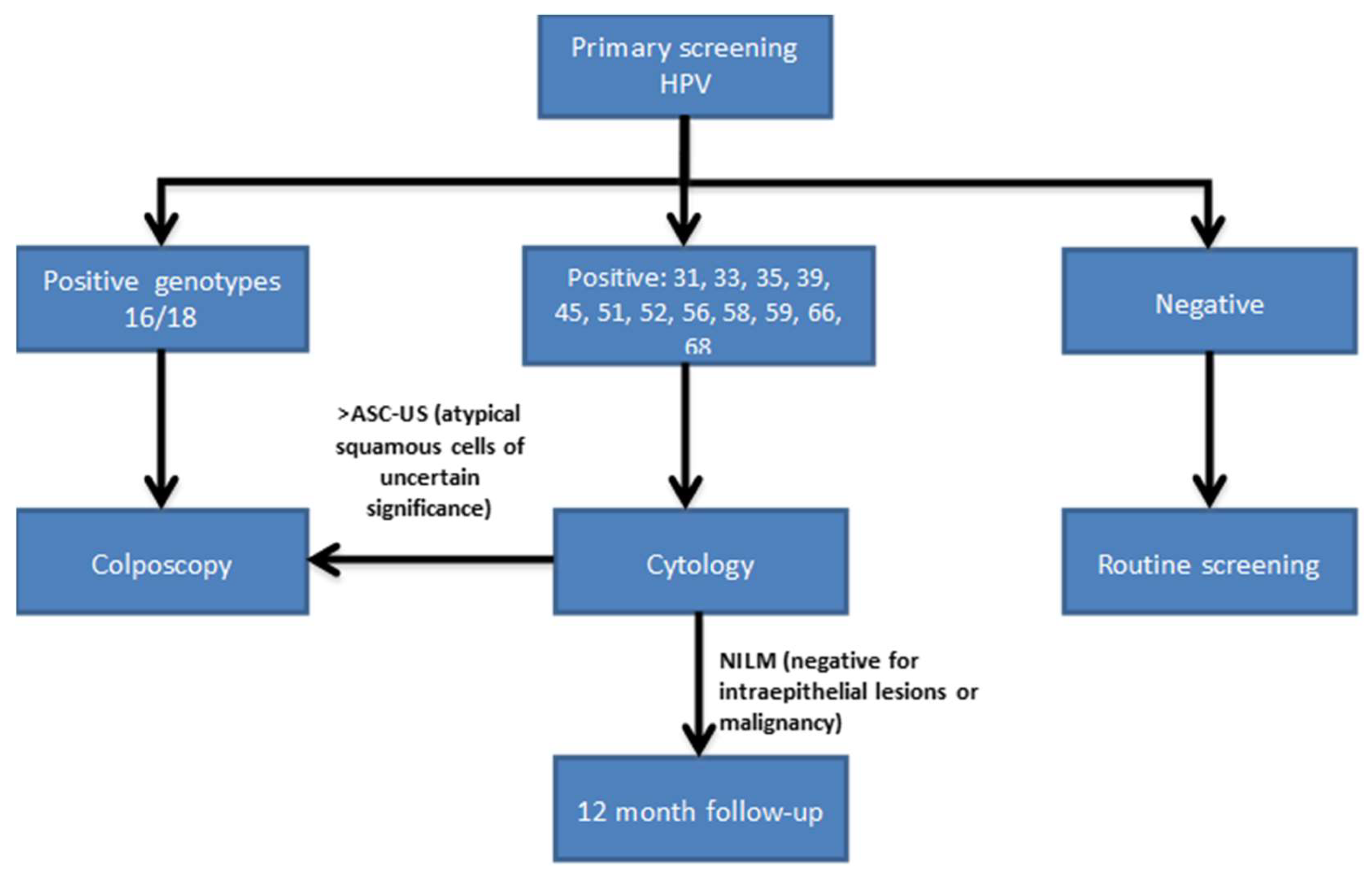

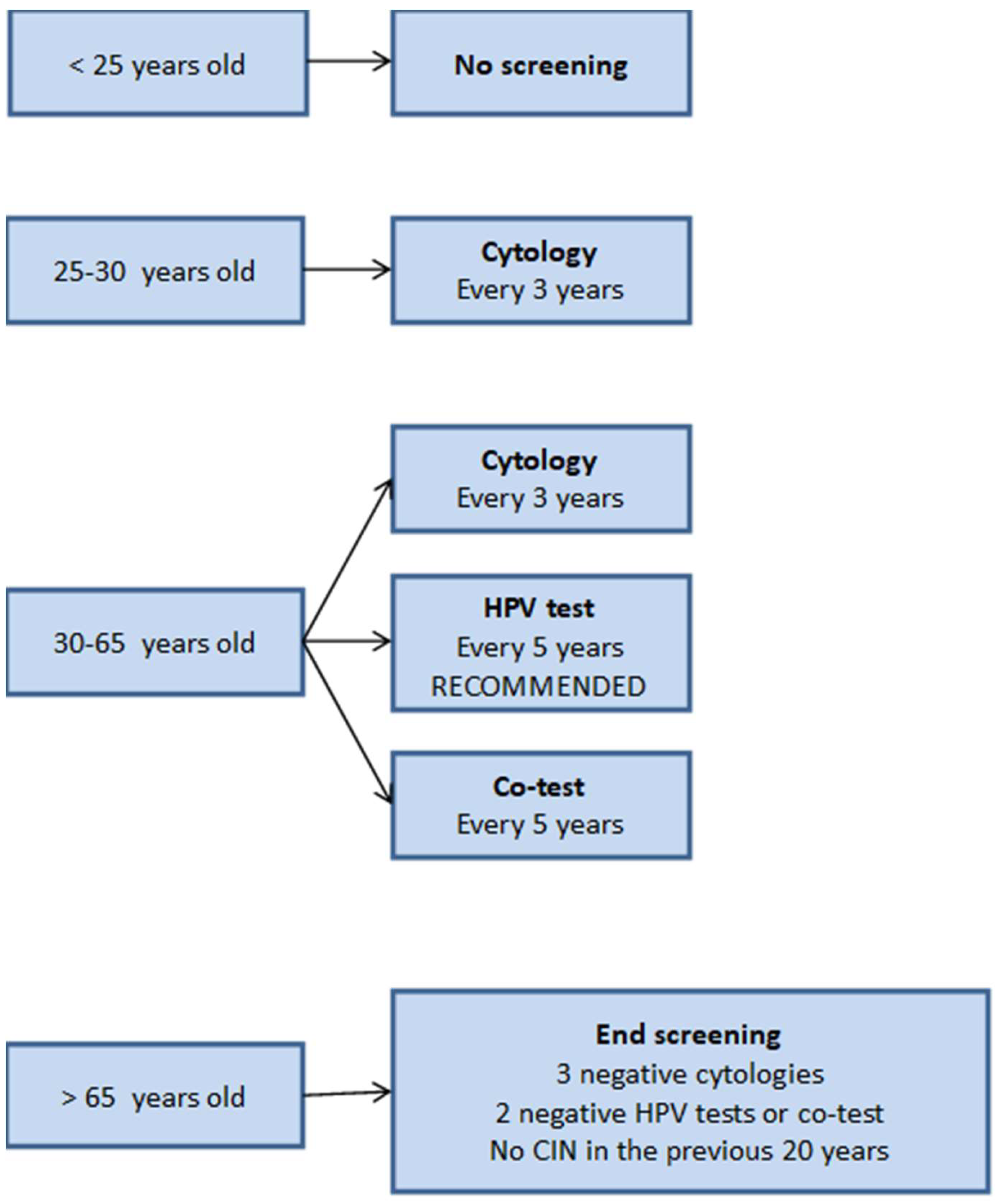

6. Proposed Algorithm for Population Screening of CC

The algorithm for population screening of CC followed by our country at the moment is the one proposed by the Spanish Society of Gynecology and Obstetrics [

59] (

Figure 2). The most notable aspects are that screening should not be started until women are 25 years old, that the cytology is recommended as the initial test in women between 25 and 30 years of age due to the increased prevalence of HPV infection in this age group and, that, for women older than 30, the HPV test is the preferred option as primary test although the 3 options are acceptable. In case of a positive result in this test, it is recommended to perform a

reflex cytology, that is, in the same cervical scraping sample. For cases in which cytology results show atypical squamous cells of unknown significance or more severe lesions (>ASC-US), a colposcopy is indicated. Co-testing (cytology and HR-HPV) every 5 years and cytology every 3 years are also acceptable options. This algorithm is also followed in other European countries although European guidelines make a recommendation against co-testing.

Bearing in mind the large volume of scientific evidence about the importance of knowing whether HPV-16 and HPV-18 are present in the cervix, Huh et al. [

60] has reached an agreement for a screening algorithm for CC based on the HPV test with partial genotyping as the primary test. Women with positive results for HPV-16 or HPV-18 will be directly studied with colposcopy and the cytology will be used as a triage test in cases where HR-HPV results are positive to other HR-HPV no16, 18 (

Figure 3). If cytology is negative for intraepithelial lesion or malignancy the patient will be followed up in 12 months and retested with HPV test. The use of HPV16 and HPV18 to triage colposcopy referral has been proposed also by other authors, suggesting the need of using cytology at the first screening round [

48]. This algorithm appears to comply with the requirements of being “acceptable, effective, efficient and based in recent scientific evidence”, as Australian Health Authorities suggest that a CC screening should be. Australia, always pioneer, will take a step forward, and has decided that, starting in 2017, it will also initiate this protocol based on partial genotyping [

61]. Certainly, other countries will follow their steps in the following years.

Interestingly, a small proportion of invasive cases resulted negative using various HPV assays. Most of these HPV negative cases could not be distinguished from endometrial carcinomas on the histology [

62]. But it is important to consider that false negative HPV test results cannot be ruled no matter the assay used.

Now, whichever is the screening strategy selected, we must bear in mind that 50% of women suffering CC have never participated in screenings and 10% have only participated in periods of over 5 years [

63]. Thus, whether it is with cytology, HPV test or partial genotyping, the first goal we must pursue is that screening becomes organized, population-based, that it covers all the women within the affected age groups (women between 30 and 60 years old) [

59], that it is easily accessed, and that it has extended coverage. With these measures, along with the implementation of the vaccine, we will achieve the disappearance of this completely preventable ever disease.

7. Conclusions

The global strategy to eliminate CC as a public health problem, adopted by the World Health Assembly in 2020, recommends a comprehensive approach to CC prevention and control. The primary goal of screening is to reduce the incidence of and mortality from CC by identifying women with precursor lesions at increased risk of progression to invasive cancer. In recent years, primary screening with an HPV test has been shown to be more sensitive than cytology in detecting premalignant lesions and to perform better in preventing CC. These tests are a very sensitive and early marker of the risk of cancer or precursor lesions, especially in women over 30 years of age. They also have the advantage of substantially increasing the detection of cervical adenocarcinoma and its precancerous lesions compared to cytology. In younger women, under 30 years of age, they would not be indicated given the high prevalence of transient HPV infections, which would imply a significant risk of overdiagnosis and overtreatment. Cervical cytology would be limited to women between 25 and 30-35 years in screening programs. The five-year disease-free rate after a negative HPV test is equivalent to the three-year disease-free rate after a negative cytology. Therefore, the use of the HPV test allows for extended screening intervals with a consequent reduction in costs. Primary screening with HPV testing offers a higher sensitivity than cytology for the diagnosis of premalignant lesions but has a lower specificity. Therefore, a triage test is needed to stratify the risk of premalignant lesions. Otherwise, performing colposcopy on all HPV-positive women without screening would carry a high risk of overdiagnosis, overtreatment and cost overruns. Due to its high specificity cervical cytology has been considered an appropriate triage test. Screening will continue to play a key role, constantly evolving to remain useful as a clinical and public health activity. The strategy of screening combined with vaccination can provide the greatest protection against CC, achieving the greatest cost-effectiveness.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and direction, M.T.P.-G.; methodology, M.T.P.-G, A.T.-P., S.F.-A, C.M.-C; B.S.-G.; writing—original draft preparation, M.T.P.-G.; writing—review and editing, M.T.P.-G, A.T.-P., S.F.-A, C.M.-C; B.S.-G.; visualization, M.T.P.-G, A.T.-P., S.F.-A, C.M.-C; B.S.-G.; supervision, M.T.P.-G project administration, M.T.P.-G; funding acquisition, M.T.P.-G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by University CEU Cardenal Herrera (GIR24/45 and INDI24/55).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- de Martel, C. , Georges, D., Bray, F., Ferlay, J., Clifford, G. M. Global burden of cancer attributable to infections in 2018: a worldwide incidence analysis. The Lancet. Global health, 8. [CrossRef]

- Hillemanns, P.; Soergel, P.; Hertel, H.; Jentschke, M. Epidemiology and Early Detection of Cervical Cancer. Oncol Res Treat. 2016, 39, 501–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grupo de trabajo de Cribado de Cáncer de Cérvix de la Ponencia de Cribado Poblacional de la Comisión de Salud Pública. Documento de consenso sobre la modificación del Programa de Cribado de Cáncer de Cérvix. Adaptación de la edad de inicio del cribado primario con prueba VPH y de la del cribado en cohortes vacunadas. Ministerio de Sanidad, 2023. Available online: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/areas/promocionPrevencion/cribado/cribadoCancer/cancerCervix/docs/DocumentoconsensomodificacionCervix.pdf (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- International Agency for Research on Cancer. Available online: https://www.iarc.who.int/cancer-type/cervical-cancer/ (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- Hull, R.; Mbele, M.; Makhafola, T.; Hicks, C.; Wang, S.; Reis, R.M.; Dlamini, Z. Cervical cancer in low and middle-income countries (Review). Oncol Lett 2020, 20, 2058–2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/human-papilloma-virus-and-cancer (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- Arbyn, M.; Roelens, J.; Simoens, C.; Buntinx, F.; Paraskevaidis, E.; Martin-Hirsch, P.P.; Prendiville, W.J. Human papillomavirus teting vesus repeat cytology for triage of minor cytological cervical lesions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013, 28, CD008054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.J.; Castle, P.E.; Lorincz, A.T.; Wacholder, S.; Sherman, M.; Scott, D.R.; Rush, B.B.; Glass, A.G.; Schiffman, M. The elevated 10-year risk of cervical precancer and cancer in women with human papillomavirus (HPV) type 16 or 18 and the possible utility of type-specific HPV testing in clinical practice. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005, 97, 1072–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, T. C. , Jr, Stoler, M. H., Sharma, A., Zhang, G., Behrens, C., Wright, T. L., ATHENA (Addressing THE Need for Advanced HPV Diagnostics) Study Group. Evaluation of HPV-16 and HPV-18 Genotyping for the Triage of Women With High-Risk HPV+ Cytology-Negative Results. Am J Clin Pathol. [CrossRef]

- Bouvard, V. , Baan, R., Straif, K., Grosse, Y., Secretan, B., El Ghissassi, F., Benbrahim-Tallaa, L., Guha, N., Freeman, C., Galichet, L., Cogliano, V., & WHO International Agency for Research on Cancer Monograph Working Group. A review of human carcinogens--Part B: biological agents. Lancet Oncol. [CrossRef]

- Mlynarczyk-Bonikowska, B. , Rudnicka, L. HPV Infections—Classification, Pathogenesis, and Potential New Therapies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, F.; Georges, D.; Man, I.; Baussano, I.; Clifford, G.M. Causal attribution of human papillomavirus genotypes to invasive cervical cancer worldwide: a systematic analysis of the global literature. Lancet. 2024, 404, 435–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sankovski, E.; Mannik, A.; Geimanen, J.; Ustav, E.; Ustav, M. Mapping of betapapillomavirus human papillomavirus 5 transcription and characterization of viral-genome replication function. J Virol. 2014, 88, 961–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turek, L.P. The structure, function, and regulation of papillomaviral genes in infection and cervical cancer. Adv Virus Res. 1994, 44, 305–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedroza-Saavedra, A.; Lam, E.W.; Esquivel-Guadarrama, F.; Gutierrez-Xicotencatl, L. The human papillomavirus type 16 E5 oncoprotein synergizes with EGF-receptor signaling to enhance cell cycle progression and the down-regulation of p27(Kip1). Virology. 2010, 400, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- zur Hausen, H. Papillomaviruses and cancer: from basic studies to clinical application. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002, 2, 342–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melsheimer, P. , Vinokurova, S., Wentzensen, N., Bastert, G., von Knebel Doeberitz, M. DNA aneuploidy and integration of human papillomavirus type 16 e6/e7 oncogenes in intraepithelial neoplasia and invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix uteri. Clin Cancer Res, 3059; 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branca, M.; Giorgi, C.; Ciotti, M.; Santini, D.; Di Bonito, L.; Costa, S.; Benedetto, A.; Bonifacio, D.; Di Bonito, P.; Paba, P.; Accardi, L.; Mariani, L.; Ruutu, M.; Syrjänen, S.; Favalli, C.; Syrjänen, K. Upregulation of telomerase (hTERT) is related to the grade of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, but is not an independent predictor of high-risk human papillomavirus, virus persistence, or disease outcome in cervical cancer. Diagn Cytopathol. 2006, 34, 739–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klingelutz, C.; Foster, S.A.; McDougall, J.K. Telomerase activation by the oncogene product of human papillomavirus type 16. Nature. 1996, 380, 79–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Ghai, J.; Ostrow, R.S.; McGlennen, R.C.; Faras, A.J. The E6 gene of human papillomavirus type 16 is sufficient for transformation of baby rat kidney cells in cotransfection with activated Ha-ras. Virology 1994, 238, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndisdang, D.; Morris, P.J.; Chapman, C.; Ho, L.; Singer, A.; Latchman, D.S. The VPH-activating cellular transcription factor Brn-3a is overexpressed in CIN3 cervical lesions. J Clin Invest. 1998, 101, 1687–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Songock, W.K.; Kim, S.M.; Bodily, J.M. The human papillomavirus E7 oncoprotein as a regulator of transcription. Virus Res. 2017, 231, 56–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicholson, S.; Whitehouse, H.; Naidoo, K.; Byers, R.J. Yin Yang 1 in human cancer. Crit Rev Oncog, 2011;16(3-4):245-260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon D, Davey D, Kurman R, et al. The 2001 Bethesda System: terminology for reporting results of cervical cytology. JAMA, 2002; 287, 2114–2119. [CrossRef]

- Dalla Palma P, Giorgi Rossi P, Collina G, et al. The risk of false-positive histology according to the reason for colposcopy referral in cervical cancer screening: a blind revision of all histologic lesions found in the NTCC trial. Am J Clin Pathol, 2008, 129, 75-80. [CrossRef]

- Meijer, C.J.; Berkhof, J.; Castle, P.E.; Hesselink, A.T.; Franco, E.L.; Ronco, G.; Arbyn, M.; Bosch, F.X.; Cuzick, J.; Dillner, J.; Heideman, D.A.; Snijders, P.J. Guidelines for human papillomavirus DNA test requirements for primary cervical cancer screening in women 30 years and older. Int J Cancer. 2009, 124, 516–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbyn, M.; Snijders, P.J.; Meijer, C.J.; Berkhof, J.; Cuschieri, K.; Kocjan, B.J.; Poljak, M. Which high-risk HPV assays fulfil criteria for use in primary cervical cancer screening? Clin Microbiol Infect. 2015, 21, 817–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erickson, B.K.; Alvarez, R.D.; Huh, W.K. Human papillomavirus: what every provider should know. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013, 208, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mateos-Lindemann, M.L.; Pérez-Castro, S.; Pérez-Gracia, M.T.; Rodriguez-Iglesias, M. Diagnóstico microbiológico de la infección por el virus del papiloma humano. 57. Mateos-Lindemann ML (coordinador). Procedimientos en Microbiología Clínica. Cercenado Mansilla E, Cantón Moreno R (editores). Sociedad Española de Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiología Clínica (SEIMC). 2016.

- Salazar, K.L.; Duhon, D.J.; Olsen, R.; Thrall, M. A review of the FDA-approved molecular testing platforms for human papillomavirus. Journal of the American Society of Cytopathology 2019, 8, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castle, P.E.; Solomon, D.; Wheeler, C.M.; Gravitt, P.E.; Wacholder, S.; Schiffman, M. Human papillomavirus genotype specificity of hybrid capture 2. J Clin Microbiol. 2008, 46, 2595–2604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Day, S.P. , Hudson, A., Mast, A., et al. Analytical performance of the Investigational Use Only Cervista HPV HR test as determined by a multi-center study. J Clin Virol, 45. [CrossRef]

- Fokom Domgue, J.; Schiffman, M.; Wentzensen, N.H.; Gage, J.C.; Castle, P.E.; Raine-Bennett, T.R.; Fetterman, B.; Lorey, T.; Poitras, N.E.; Befano, B.; Xie, Y.; Miachon, L.S.; Dean, M. Assessment of a New Lower-Cost Real-Time PCR Assay for Detection of High-Risk Human Papillomavirus: Useful for Cervical Screening in Limited-Resource Settings? J Clin Microbiol. 2017, 55, 2348–2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nolte, F.S.; Ribeiro-Nesbitt, D.G. Comparison of the Aptima and Cervista tests for detection of high-risk human papillomavirus in cervical cytology specimens. Am J Clin Pathol. 2014, 142, 561–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindemann, M.L.; Dominguez, M.J.; de Antonio, J.C.; Sandri, M.T.; Tricca, A.; Sideri, M.; Khiri, H.; Ravet, S.; Boyle, S.; Aldrich, C.; Halfon, P. Analytical comparison of the cobas HPV Test with Hybrid Capture 2 for the detection of high-risk HPV genotypes. J Mol Diagn. 2012, 14, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateos, M.L.; Chacón de Antonio, J.; Rodríguez-Domínguez, M.; Sanz, I.; Rubio, M.D. Evaluation of a prototype real-time PCR assay for the separate detection of human papilloma virus genotypes 16 and 18 and other high risk human papillomavirus in cervical cancer screening]. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2011, 29, 411–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heideman, D.A.; Hesselink, A.T.; Berkhof, J.; van Kemenade, F.; Melchers, W.J.; Daalmeijer, N.F.; Verkuijten, M.; Meijer, C.J.; Snijders, P.J. Clinical validation of the cobas 4800 HPV test for cervical screening purposes. J Clin Microbiol. 2011, 49, 3983–3985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nogueira Dias Genta, M.L.; Martins, T.R.; Mendoza Lopez, R.V.; Sadalla, J.C.; de Carvalho JP, M.; Baracat, E.C.; Levi, J.E.; Carvalho, J.P. Multiple HPV genotype infection impact on invasive cervical cancer presentation and survival. PLoS One. 2017, 12, e0182854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preisler, S.; Rebolj, M.; Ejegod, D.M.; Lynge, E.; Rygaard, C.; Bonde, J. Cross-reactivity profiles of hybrid capture II, cobas, and APTIMA human papillomavirus assays: split-sample study. BMC Cancer. 2016, 16, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobas, H.P.V. Available online:. Available online: https://elabdoc-prod.roche.com/eLD/api/downloads/da337b1a-da0e-ef11-2491-005056a772fd?countryIsoCode=gb (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- Wright, T. C. , Jr, Stoler, M. H., Agreda, P. M., Beitman, G. H., Gutierrez, E. C., Harris, J. M., Koch, K. R., Kuebler, M., LaViers, W. D., Legendre, B. L., Jr, Leitch, S. V., Maus, C. E., McMillian, R. A., Nussbaumer, W. A., Palmer, M. L., Porter, M. J., Richart, G. A., Schwab, R. J., Vaughan, L. M. Clinical performance of the BD Onclarity HPV assay using an adjudicated cohort of BD SurePath liquid-based cytology specimens. Am J Clin Pathol. [CrossRef]

- Internacional Agency for Research on Cancer. Cervical cancer screening. Lyon: Internacional Agency for Research on Cancer Press. 2022.

- Ronco, G. , Giorgi-Rossi, P., Carozzi, F., Confortini, M., Dalla Palma, P., Del Mistro, A., Ghiringhello, B., Girlando, S., Gillio-Tos, A., De Marco, L., Naldoni, C., Pierotti, P., Rizzolo, R., Schincaglia, P., Zorzi, M., Zappa, M., Segnan, N., Cuzick, J., New Technologies for Cervical Cancer screening (NTCC) Working Group. Efficacy of human papillomavirus testing for the detection of invasive cervical cancers and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol, 2010; 11, 249-257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castanon, A.; Landy, R.; Sasieni, P. How much could primary human papillomavirus testing reduce cervical cancer incidence and morbidity? J Med Screen. 2013, 20, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronco, G. , Dillner, J., Elfström, K. M., Tunesi, S., Snijders, P. J., Arbyn, M., Kitchener, H., Segnan, N., Gilham, C., Giorgi-Rossi, P., Berkhof, J., Peto, J., Meijer, C. J., International HPV screening working group (2014). Efficacy of HPV-based screening for prevention of invasive cervical cancer: follow-up of four European randomised controlled trials. Lancet. [CrossRef]

- Cuzick, J.; Clavel, C.; Petry, K.U.; Meijer, C.J.; Hoyer, H.; Ratnam, S.; Szarewski, A.; Birembaut, P.; Kulasingam, S.; Sasieni, P.; Iftner, T. Overview of the European and North American studies on HPV testing in primary cervical cancer screening. Int J Cancer. 2006, 119, 1095–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoler, M.H.; Schiffman, M. Atypical Squamous Cells of Undetermined Significance-Low-grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesion Triage Study (ALTS) Group. Interobserver reproducibility of cervical cytologic and histologic interpretations: realistic estimates from the ASCUS-LSIL Triage Study. JAMA, 1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchener, H.C.; Denton, K.; Soldan, K.; Crosbie, E.J. Developing role of HPV in cervical cancer prevention. BMJ. 2013, 7, f4781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katki, H.A.; Schiffman, M.; Castle, P.E.; Fetterman, B.; Poitras, N.E.; Lorey, T.; Cheung, L.C.; Raine-Bennett, T.; Gage, J.C.; Kinney, W.K. Five year risk of recurrence after treatment of CIN2, CIN3, or AIS: performance of HPV and Pap cotesting in posttreatment Management. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2013, 17, S78–S84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubie, H.A.; Cuschieri, K. Understanding HPV tests and their appropriate applications. Cytopathology. 2013, 24, 289–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronco, G.; Biggeri, A.; Confortini, M.; Naldoni, C.; Segnan, N.; Sideri, M.; Zappa, M.; Zorzi, M.; Calvia, M.; Accetta, G.; Giordano, L.; Cogo, C.; Carozzi, F.; Gillio Tos, A.; Arbyn, M.; Mejier, C.J.; Snijders, P.J.; Cuzick, J.; Giorgi Rossi, P. Health Technology Asessment report: HPV DNA based primary screening for cervical cancer precursors. Epidemiol Prev. 2012, 36, 31–71. [Google Scholar]

- Health Council of the Netherlands. 2011. Available online: http://www.gezondheidsraad.nl/sites /default/files/summaryBHMK.pdf (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- Saslow, D. , Solomon, D., Lawson, H. W., Killackey, M., Kulasingam, S. L., Cain, J., Garcia, F. A., Moriarty, A. T., Waxman, A. G., Wilbur, D. C., Wentzensen, N., Downs, L. S., Jr, Spitzer, M., Moscicki, A. B., Franco, E. L., Stoler, M. H., Schiffman, M., Castle, P. E., Myers, E. R. American Cancer Society, American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and American Society for Clinical Pathology screening guidelines for the prevention and early detection of cervical cancer. Am J Clin Pathol. [CrossRef]

- Bray, F.; Loos, A.H.; McCarron, P.; Weiderpass, E.; Arbyn, M.; Møller, H.; Hakama, M.; Parkin, D.M. Trends in cervical squamous cell carcinoma incidence in 13 European countries: changing risk and the effects of screening. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005, 14, 677–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wentzensen, N.; Schiffman, M.; Palmer, T.; Arbyn, M. Triage of HPV positive women in cervical cancer screening. J Clin Virol. 2016, 76, S49–S55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carozzi, F. , Confortini, M., Dalla Palma, P., Del Mistro, A., Gillio-Tos, A., De Marco, L., Giorgi-Rossi, P., Pontenani, G., Rosso, S., Sani, C., Sintoni, C., Segnan, N., Zorzi, M., Cuzick, J., Rizzolo, R., Ronco, G., & New Technologies for Cervival Cancer Screening (NTCC) Working GroupUse of p16-INK4A overexpression to increase the specificity of human papillomavirus testing: a nested substudy of the NTCC randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2008, 9, 937–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, T.C. Jr. , Stoler, M.H., Behrens, C.M., Apple, R., Derion, T., Wright, T.L. The ATHENA human papillomavirus study: design, methods, and baseline results. Am J Obstet Gynecol. [CrossRef]

- Rijkaart, D. C. , Berkhof, J., van Kemenade, F. J., Coupe, V. M., Rozendaal, L., Heideman, D. A., Verheijen, R. H., Bulk, S., Verweij, W., Snijders, P. J., Meijer, C. J. HPV DNA testing in population-based cervical screening (VUSA-Screen study): results and implications. Br J Cancer. [CrossRef]

- Oncoguía SEGO: Prevencion del cáncer de cuello de útero. Guías de práctica clínica en cáncer ginecológico y mamario. Publicaciones SEGO, Octubre 2014. Available online: https://oncosego.sego.es/uploads/app/1283/elements/file/file1666793375.pdf (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- Huh, W.K.; Ault, K.A.; Chelmow, D.; Davey, D.D.; Goulart, R.A.; Garcia FA, R.; Kinney, W.K.; Massad, L.S.; Mayeaux, E.J.; Saslow, D.; Schiffman, M.; Wentzensen, N.; Lawson, H.W.; Einstein, M.H. Use of primary high-risk human papillomavirus testing for cervical cancer screening: Interim clinical guidance. Gynecol Oncol. 2015, 136, 136,178–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canfell, K.; Caruana, M.; Gebski, V.; Darlington-Brown, J.; Heley, S.; Brotherton, J.; Gertig, D.; Jennett, C.J.; Farnsworth, A.; Tan, J.; Wrede, C.D.; Castle, P.E.; Saville, M. Cervical screening with primary HPV testing or cytology in a population of women in which those aged 33 years or younger had previously been offered HPV vaccination: Results of the Compass pilot randomised trial. PLoS Med. 2017, 14, e1002388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopenhayn, C.; Christian, A.; Christian, W.J.; Watson, M.; Unger, E.R.; Lynch, C.F.; Peters, E.S.; Wilkinson, E.J.; Huang, Y.; Copeland, G.; Cozen, W.; Saber, M.S.; Goodman, M.T.; Hernandez, B.Y.; Steinau, M.; Lyu, C.; Tucker, T.T.; Saraiya, M. Prevalence of human papillomavirus types in invasive cervical cancers from 7 UC cancer registries before vaccine introcuctin. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2014, 18, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, H.P.; Chu, K.C. Determinants of cancer disparities: barriers to cancer screening, diagnosis, and treatment. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2005, 14, 655–v. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).