Submitted:

13 January 2025

Posted:

14 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Chimeric antigen receptor-T (CAR-T) cell therapy has demonstrated impressive efficacy in the treatment of blood cancers; however, its effectiveness in solid tumors has been significantly limited. The differences arise from a range of difficulties linked to solid tumors, including an unfriendly tumor microenvironment, variability within the tumors, and barriers to CAR-T cell infiltration and longevity at the tumor location. Research shows that the reasons for the decreased effectiveness of CAR-T cells in treating solid tumors are not well understood, highlighting the ongoing need for strategies to address these challenges. Current strategies frequently incorporate combinatorial therapies designed to boost CAR-T cell functionality and enhance their capacity to effectively target solid tumors. Nonetheless, these strategies remain in the testing phase and necessitate additional validation to assess their potential benefits. CAR-NK (Natural Killer), CAR-iNKT (invariant Natural Killer T), and CAR-M (Macrophage) are emerging as promising strategies for treating solid tumors. Recent studies highlight the construction and optimization of CAR-NK cells, emphasizing their potential to overcome the unique challenges posed by the solid tumor microenvironment, such as hypoxia and metabolic barriers. This review focuses on CAR cell therapy in the treatment of solid tumors.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

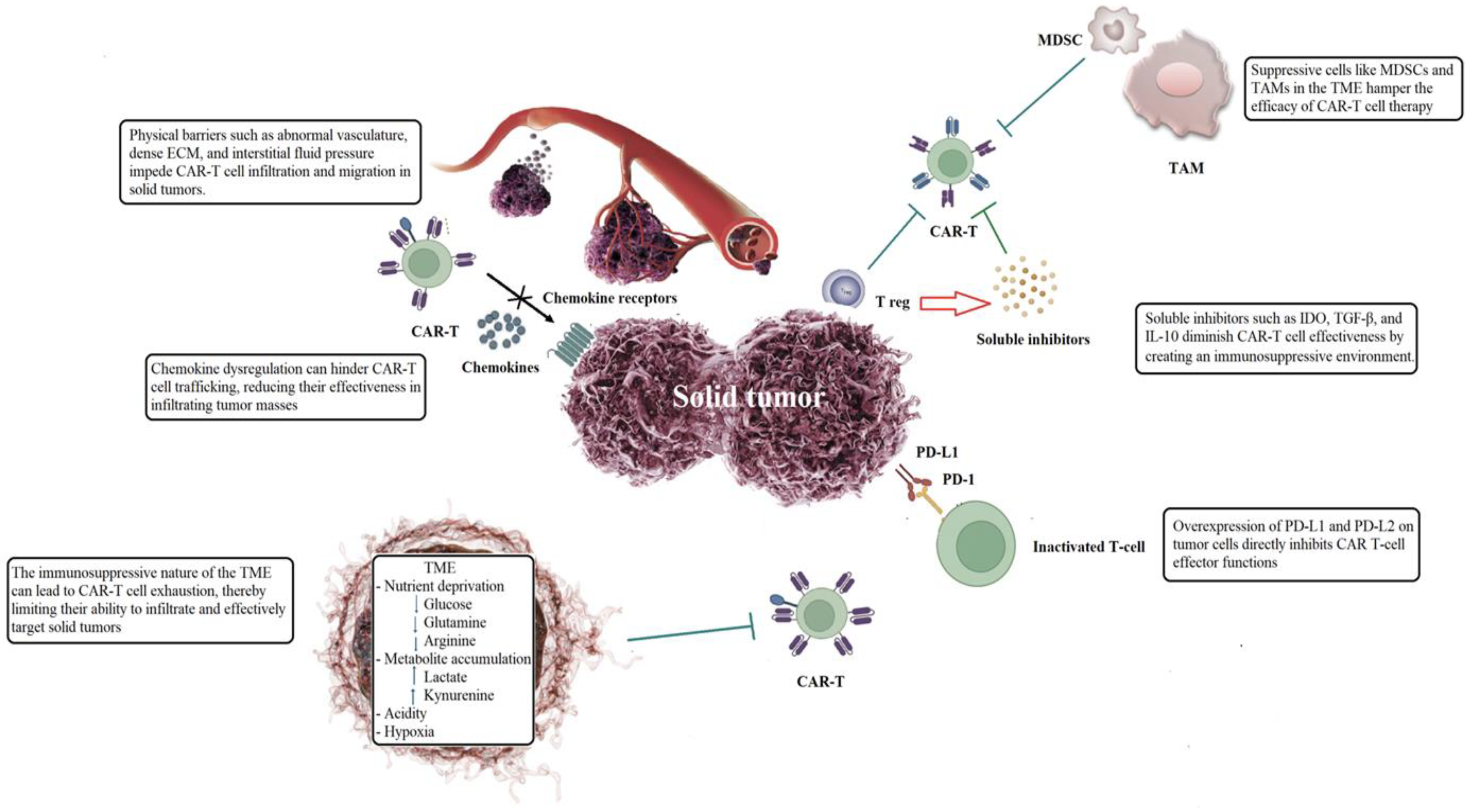

2. What Can Go Wrong with CAR-T Cell Therapy for Solid Tumors?

2.1. Physical Barriers Within Tumor Microenvironment

2.2. Trafficking and Penetration into Neoplastic Tissue

2.3. Immunosuppressive Tumor Microenvironment

2.4. Tumor-Infiltrating Immune Cells Reversed the Hostile Tumor Immune Environment

2.5. Soluble Inhibitors Impair the Functionality of CAR-T Cells

2.6. Immune Checkpoint Overexpression Hinders the Effector Functions of CAR-T Cells

3. Overview of CAR-T Cell Therapy Application in Solid Tumors

3.1. Clinical Insights on CAR-T Cell Applications for Solid and Brain Tumors

3.2. Challenges of CAR-T Cell Immunotherapy for Solid Tumors

4. If CAR-T Therapy Is Unsuccessful, Should We Consider an Alternative Approach?

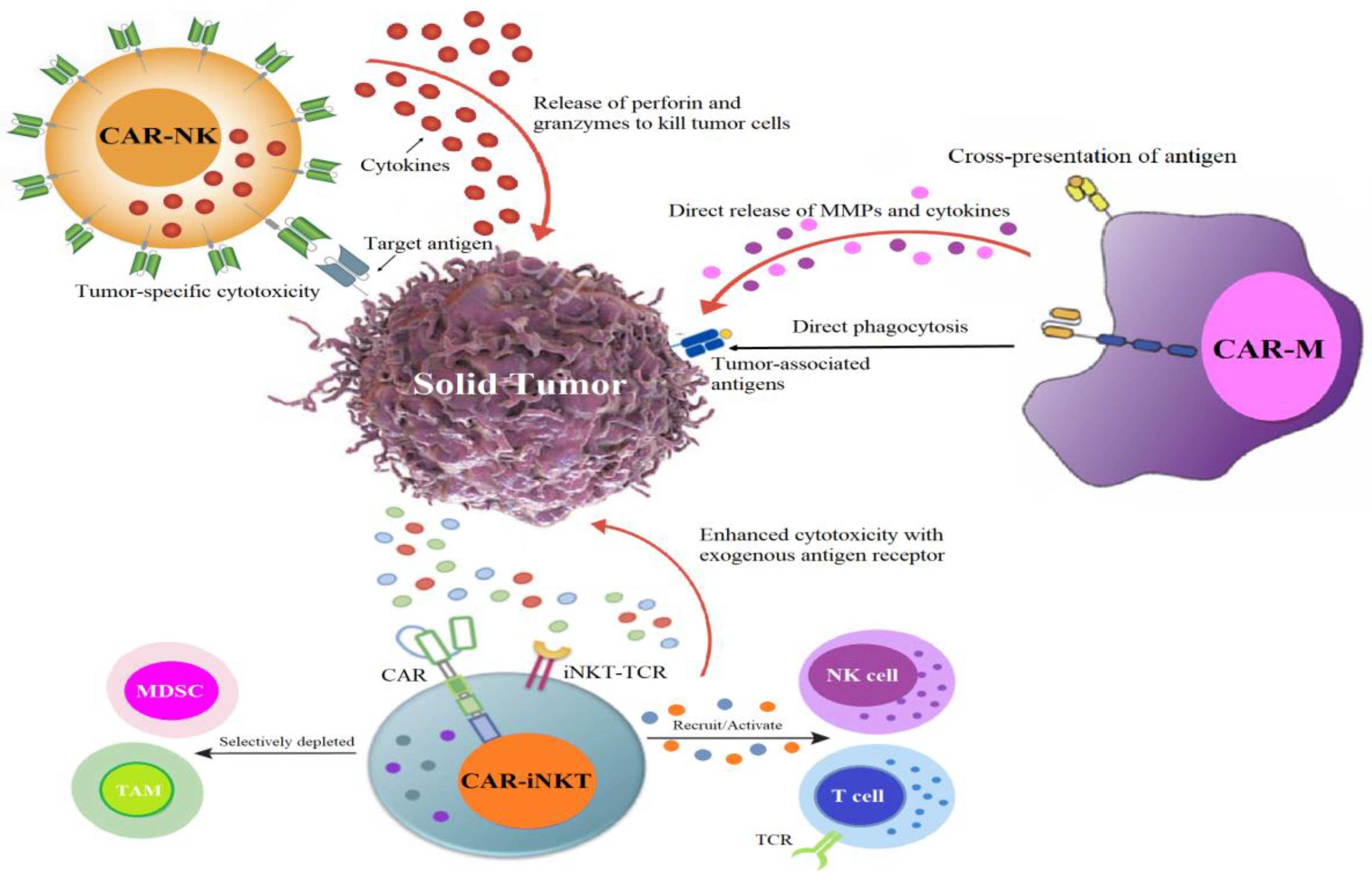

4.1. CAR Race Towards Cancer Immunotherapy: Exploring CAR-NK, CAR-iNKT, and CAR-M Therapies

4.2. CAR-NK: An Encouraging Substitute for CAR-T Therapy

4.3. CAR-iNKT Immunotherapy: A Novel Path for CAR-Based Cancer Immunotherapy

4.3.1. Development of iNKT Cells

4.3.2. Antitumoral Role of iNKT Cells

4.3.3. iNKT Protects from GVHD

4.3.4. Essential Cytokines Enhance CAR-iNKT Activity

4.4. CAR-Macrophage: Pioneering Advancements in Cellular Immunotherapy

4.4.1. Structure and Functioning of CAR-Ms

4.4.2. Cell Source of CAR-Ms

4.4.3. Preclinical and Clinical Studies of CAR-Ms

4.4.4. The Advantages, Obstacles, and Prospective Trajectory of CAR-M

4.4.5. The Future Direction of CAR-M Therapy

4.4.6. CAR-M Therapy Alongside Additional Immunotherapeutic Approaches

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Copyright Disclaimer

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, X.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, H.; Chen, S.; Xiao, Y. CAR-T Cell Therapy in Hematological Malignancies: Current Opportunities and Challenges. Front. Immunol. 2022; 13:927153. [CrossRef]

- Chohan, K.L.; Siegler, E.L.; Kenderian, S.S. CAR-T Cell Therapy: the Efficacy and Toxicity Balance. Curr. Hematol. Malig. Rep. 2023; 18:9-18. [CrossRef]

- Choudhery, M.S.; Arif, T.; Mahmood, R.; Harris, D.T. CAR-T-Cell-Based Cancer Immunotherapies: Potentials, Limitations, and Future Prospects. J. Clin. Med. 2024; 13:3202. [CrossRef]

- Kankeu Fonkoua, L.A.; Sirpilla, O.; Sakemura, R.; Siegler, E.L.; Kenderian, S.S. CAR T cell therapy and the tumor microenvironment: Current challenges and opportunities. Mol. Ther. Oncolytics. 2022; 25:69-77. [CrossRef]

- Elahi, R.; Heidary, A.H.; Hadiloo, K.; Esmaeilzadeh, A. Chimeric Antigen Receptor-Engineered Natural Killer (CAR NK) Cells in Cancer Treatment; Recent Advances and Future Prospects. Stem. Cell. Rev. Rep. 2021; 17:2081-2106. [CrossRef]

- Moscarelli, J,; Zahavi, D.; Maynard, R.; Weiner, LM. The Next Generation of Cellular Immunotherapy: Chimeric Antigen Receptor-Natural Killer Cells. Transplant. Cell. Ther. 2022; 28:650-656. [CrossRef]

- Marofi, F.; Abdul-Rasheed, O.F.; Rahman, H.S.; Budi, H.S.; Jalil, A.T; Yumashev, A.V.; Hassanzadeh, A.; Yazdanifar, M.; Motavalli, R.; Chartrand, M.S.; et al. CAR-NK cell in cancer immunotherapy; A promising frontier. Cancer. Sci. 2021; 112:3427-3436. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Zhou, W., Yang, J.; Yang, J.; Wang, W. Chimeric antigen receptor engineered natural killer cells for cancer therapy. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 2023; 12:70. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Wang, Y.; Dou, Z.; Delfanti, G.; Tsahouridis, O.; Pellegry, C.M.; Zingarelli, M.; Atassi, G.; Woodcock, M.G.; Casorati, G.; et al. CAR-redirected natural killer T cells demonstrate superior antitumor activity to CAR-T cells through multimodal CD1d-dependent mechanisms. Nat. Cancer. 2024; 5:1607-1621. [CrossRef]

- Moraes Ribeiro, E.; Secker, K.A.; Nitulescu, A.M.; Schairer, R.; Keppeler, H.; Wesle, A.; Schmid, H.; Schmitt, A.; Neuber, B.; Chmiest, D.; et al. PD-1 checkpoint inhibition enhances the antilymphoma activity of CD19-CAR-iNKT cells that retain their ability to prevent alloreactivity. J. Immunother. Cancer. 2024; 12:e007829.

- Lu, J.; Ma, Y.; Li, Q.; Xu, Y.; Xue, Y.; Xu, S. CAR Macrophages: a promising novel immunotherapy for solid tumors and beyond. Biomark. Res. 2024; 12:86. [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Lei, A.; Wang, X.; Lu, H.; Wang, S.; Yang, Y.; Li, N.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J. Induced CAR-Macrophages as a Novel Therapeutic Cell Type for Cancer Immune Cell Therapies. Cells. 2022; 11:1652. [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Wang, Y.; Jia, J.; Fang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Yuan, W.; Hu, J. Advances in Engineered Macrophages: A New Frontier in Cancer Immunotherapy. Cell. Death. Dis. 2024; 15:238. [CrossRef]

- Donnadieu, E.; Dupré, L.; Pinho, L.G.; Cotta-de-Almeida, V. Surmounting the obstacles that impede effective CAR T cell trafficking to solid tumors. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2020; 108:1067-1079. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wang, X.; Dou, H.; Yu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, S.; Xiao, M. Extracellular matrix remodeling in tumor progression and immune escape: from mechanisms to treatments. Mol. Cancer. 2023; 22:48. [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Quintero, J.; Díaz, M.P.; Palmar, J.; Galan-Freyle, N.J.; Morillo, V.; Escalona, D.; González-Torres, H.J.; Torres, W.; Navarro-Quiroz, E.; Rivera-Porras, D.; et al. Car T Cells in Solid Tumors: Overcoming Obstacles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024; 25:4170. [CrossRef]

- de Visser, K.E.; Joyce, J.A. The evolving tumor microenvironment: From cancer initiation to metastatic outgrowth. Cancer. Cell. 2023; 41:374-403.

- Liu, Z.L.; Chen, H.H.; Zheng, L.L.; Sun, L.P.; Shi, L. Angiogenic signaling pathways and anti-angiogenic therapy for cancer. Signal. Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023; 8:198. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Chen, H.; Li, F.; Huang, S.; Chen, F.; Li, Y. Bright future or blind alley? CAR-T cell therapy for solid tumors. Front. Immunol. 2023; 14:1045024. [CrossRef]

- Daei Sorkhabi, A.; Mohamed Khosroshahi, L.; Sarkesh, A.; Mardi, A.; Aghebati-Maleki, A.; Aghebati-Maleki, L.; Baradaran, B. The current landscape of CAR T-cell therapy for solid tumors: Mechanisms, research progress, challenges, and counterstrategies. Front. Immunol. 2023; 14:1113882. [CrossRef]

- Guzman, G.; Pellot, K.; Reed, M.R.; Rodriguez, A. CAR T-cells to treat brain tumors. Brain. Res. Bull. 2023; 196:76-98. [CrossRef]

- Marofi, F.; Motavalli, R.; Safonov, V.A.; Thangavelu, L.; Yumashev, A.V.; Alexander, M.; Shomali, N.; Chartrand, M.S.; Pathak, Y.; Jarahian, M.; et al. CAR T cells in solid tumors: challenges and opportunities. Stem. Cell. Res. Ther. 2021; 12:81. [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.; Riddell, S.R. Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cell Therapy: Challenges to Bench-to-Bedside Efficacy. J. Immunol. 2018; 200:459-468. [CrossRef]

- Foeng, J.; Comerford, I.; McColl, S.R. Harnessing the chemokine system to home CAR-T cells into solid tumors. Cell. Rep. Med. 2022; 3:100543. [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Li, Y.; Shao, Y.; Zhang, Y. Gene modification strategies for next-generation CAR T cells against solid cancers. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2020; 13:54. [CrossRef]

- Charrot, S.; Hallam, S. CAR-T Cells: Future Perspectives. Hemasphere. 2019; 3:e188.

- Liu, J.; Bai, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Luo, K. Reprogramming the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment through nanomedicine: an immunometabolism perspective. EBioMedicine. 2024; 107:105301. [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Yang, Z.; Lu, Q.; Liu, Z.; Wang, L.; Du, J.; Li, Y.; Yang, D.H.; Wu, S. Reshaping the tumor immune microenvironment to improve CAR-T cell-based cancer immunotherapy. Mol. Cancer. 2024; 23:175. [CrossRef]

- Cortellino, S.; Longo, V.D. Metabolites and Immune Response in Tumor Microenvironments. Cancers (Basel). 2023; 15:3898. [CrossRef]

- Shi, R.; Tang, Y.Q.; Miao, H. Metabolism in tumor microenvironment: Implications for cancer immunotherapy. MedComm. 2020; 1:47-68. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Xu, R.; Chen, X.; Lu, Y.; Zheng, J.; Lin, Y.; Lin, P.; Zhao, X.; Cui, L. Metabolic gatekeepers: harnessing tumor-derived metabolites to optimize T cell-based immunotherapy efficacy in the tumor microenvironment. Cell. Death. Dis. 2024; 15:775. [CrossRef]

- Poorebrahim, M.; Melief, J.; Pico de Coaña, Y.; L Wickström, S.; Cid-Arregui, A.; Kiessling, R. Counteracting CAR T cell dysfunction. Oncogene. 2021; 40:421-435.

- Zhang, H.; Li, S.; Wang, D.; Liu, S.; Xiao, T.; Gu, W.; Yang, H.; Wang, H.; Yang, M.; Chen, P. Metabolic reprogramming and immune evasion: the interplay in the tumor microenvironment. Biomark. Res. 2024; 12:96.

- Shi, H.; Li, K.; Ni, Y.; Liang, X.; Zhao, X. Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells: Implications in the Resistance of Malignant Tumors to T Cell-Based Immunotherapy. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 2021; 9:707198. [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Luo, Y.; Rao, D.; Wang, T.; Lei, Z.; Chen. X.; Zhang, B.; Li, Y.; Liu, B.; Xia, L.; et al. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in cancer: therapeutic targets to overcome tumor immune evasion. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 2024; 13:39. [CrossRef]

- Dysthe, M.; Parihar, R. Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells in the Tumor Microenvironment. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2020; 1224:117-140.

- Li, K.; Shi, H.; Zhang, B.; Ou, X.; Ma, Q.; Chen, Y.; Shu, P.; Li, D.; Wang, Y. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as immunosuppressive regulators and therapeutic targets in cancer. Signal. Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021; 6:362. [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Kang, T.; Chen, S. The role of tumor-associated macrophages in tumor immune evasion. J. Cancer. Res. Clin. Oncol. 2024; 150:238. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Song, Y.; Du, W.; Gong, L.; Chang, H.; Zou, Z. Tumor-associated macrophages: an accomplice in solid tumor progression. J. Biomed. Sci. 2019; 26:78. [CrossRef]

- Xiang, X.; Wang, J.; Lu, D.; Xu, X. Targeting tumor-associated macrophages to synergize tumor immunotherapy. Signal. Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021; 6:75. [CrossRef]

- Sterner, R.C.; Sterner, R.M.; CAR-T cell therapy: current limitations and potential strategies. Blood. Cancer. J. 2021; 11:69.

- Maalej, K.M.; Merhi, M.; Inchakalody, V.P.; Mestiri, S.; Alam, M.; Maccalli, C.; Cherif, H.; Uddin, S.; Steinhoff, M.; Marincola, F.M.; et al. CAR-cell therapy in the era of solid tumor treatment: current challenges and emerging therapeutic advances. Mol. Cancer. 2023; 22:20. [CrossRef]

- Tai, Y.T.; Anderson, K.C. B cell maturation antigen (BCMA)-based immunotherapy for multiple myeloma. Expert. Opin. Biol. Ther. 2019; 19:1143-1156. [CrossRef]

- Akbari, P.; Katsarou, A.; Daghighian, R.; van Mil, L.W.H.G.; Huijbers, E.J.M.; Griffioen, A.W.; van Beijnum, J.R. Directing CAR T cells towards the tumor vasculature for the treatment of solid tumors. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. Rev. Cancer. 2022; 1877:188701. [CrossRef]

- Boccalatte, F.; Mina, R.; Aroldi, A.; Leone, S.; Suryadevara, C.M.; Placantonakis, D.G.; Bruno, B. Advances and Hurdles in CAR T Cell Immune Therapy for Solid Tumors. Cancers (Basel). 2022; 14:5108. [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, H.R.; Rodriguez, A.; Shepphird, J.; Brown, C.E.; Badie, B. Chimeric Antigen Receptors T Cell Therapy in Solid Tumor: Challenges and Clinical Applications. Front. Immunol. 2017; 8:1850. [CrossRef]

- Grosser, R.; Cherkassky, L.; Chintala, N.; Adusumilli, P.S. Combination Immunotherapy with CAR T Cells and Checkpoint Blockade for the Treatment of Solid Tumors. Cancer. Cell. 2019; 36:471-482. [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Kang, K.; Chen, P.; Zeng, Z.; Li, G.; Xiong, W.; Yi, M.; Xiang, B. Regulatory mechanisms of PD-1/PD-L1 in cancers. Mol. Cancer. 2024; 23:108.

- Lv, Y.; Luo, X.; Xie, Z.; Qiu, J.; Yang, J.; Deng, Y.; Long, R.; Tang, G.; Zhang, C.; Zuo, J. Prospects and challenges of CAR-T cell therapy combined with ICIs. Front. Oncol. 2024; 14:1368732. [CrossRef]

- Najafi, S.; Mortezaee, K. Modifying CAR-T cells with anti-checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy: A focus on anti PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies. Life. Sci. 2024; 338:122387.

- Tang, L.; Pan, S.; Wei, X.; Xu, X.; Wei, Q. Arming CAR-T cells with cytokines and more: Innovations in the fourth-generation CAR-T development. Mol. Ther. 2023; 31:3146-3162. [CrossRef]

- Whilding, L.M.; Maher, J. CAR T-cell immunotherapy: The path from the by-road to the freeway? Mol. Oncol. 2015; 9:1994-2018.

- Louis, C.U.; Savoldo, B.; Dotti, G.; Pule, M.; Yvon, E.; Myers, G.D.; Rossig, C.; Russell, H.V.; Diouf, O.; Liu, E.; Liu, H. et al. Antitumor activity and long-term fate of chimeric antigen receptor-positive T cells in patients with neuroblastoma. Blood. 2011; 118:6050-6056. [CrossRef]

- Wagner, J.; Wickman, E.; DeRenzo, C.; Gottschalk, S. CAR T Cell Therapy for Solid Tumors: Bright Future or Dark Reality? Mol. Ther. 2020; 28:2320-2339.

- Hou, B.; Tang, Y.; Li, W.; Zeng, Q.; Chang, D. Efficiency of CAR-T Therapy for Treatment of Solid Tumor in Clinical Trials: A Meta-Analysis. Dis. Markers. 2019; 2019:3425291. [CrossRef]

- Hazini, A.; Fisher, K.; Seymour, L. Deregulation of HLA-I in cancer and its central importance for immunotherapy. J. Immunother. Cancer. 2021; 9:e002899. [CrossRef]

- Jayaraman, J.; Mellody, M.P.; Hou, A.J.; Desai, R.P. Fung, A.W.; Pham, A.H.T.; Chen, Y.Y.; Zhao, W. CAR-T design: Elements and their synergistic function. EBioMedicine. 2020; 58:102931.

- De Marco, R.C.; Monzo, H.J.; Ojala, P.M. CAR T Cell Therapy: A Versatile Living Drug. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023; 24:6300. [CrossRef]

- Oldham, K.A.; Parsonage, G.; Bhatt, R.I.; Wallace, D.M.; Deshmukh, N.; Chaudhri, S.; Adams, D.H.; Lee, S.P. T lymphocyte recruitment into renal cell carcinoma tissue: a role for chemokine receptors CXCR3, CXCR6, CCR5, and CCR6. Eur. Urol. 2012; 61:385-394. [CrossRef]

- O’Cathail, S.M.; Pokrovska, T.D.; Maughan, T.S.; Fisher, K.D.; Seymour, L.W.; Hawkins, M.A. Combining Oncolytic Adenovirus with Radiation-A Paradigm for the Future of Radiosensitization. Front. Oncol. 2017; 7:153. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Chen, J.; Li, W.; Xu, Y.; Shan, J.; Hong, J.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, H.; Ma, J.; Shen, J.; Qian, C. Hypoxia-Responsive CAR-T Cells Exhibit Reduced Exhaustion and Enhanced Efficacy in Solid Tumors. Cancer. Res. 2024; 84:84-100. [CrossRef]

- Stampone, E.; Bencivenga, D.; Capellupo, M.C.; Roberti, D.; Tartaglione, I.; Perrotta, S.; Della Ragione, F.; Borriello, A. Genome editing and cancer therapy: handling the hypoxia-responsive pathway as a promising strategy. Cell. Mol. Life. Sci. 2023; 80:220. [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Zou, Y.; Li, L.; Lu, F.; Xu, H.; Ren, P.; Bai, F.; Niedermann, G.; Zhu, X. BAY 60-6583 Enhances the Antitumor Function of Chimeric Antigen Receptor-Modified T Cells Independent of the Adenosine A2b Receptor. Front. Pharmacol. 2021; 12:619800. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.Z.; Wang, T.; Wang, X.F.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Song, S.X.; Ma, C.Q. Improving the ability of CAR-T cells to hit solid tumors: Challenges and strategies. Pharmacol. Res. 2022; 175:106036. [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Deng, J.; Gao, L.; Zhou, J. Innovative strategies to advance CAR T cell therapy for solid tumors. Am. J. Cancer. Res. 2020; 10:1979-1992.

- Huang, Y.; Shao, M.; Teng, X.; Si, X.; Wu, L.; Jiang, P.; Liu, L.; Cai, B.; Wang, X.; Han, Y.; Feng, Y.; et al. Inhibition of CD38 enzymatic activity enhances CAR-T cell immune-therapeutic efficacy by repressing glycolytic metabolism. Cell. Rep. Med. 2024; 5:101400. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, D.; Yu, H.; Sun, Z.J. Unlocking T cell exhaustion: Insights and implications for CAR-T cell therapy. Acta. Pharm. Sin. B. 2024; 14:3416-3431. [CrossRef]

- Rafiq, S.; Yeku, O.O.; Jackson, H.J.; Purdon, T.J.; van Leeuwen, D.G.; Drakes, D.J.; Song, M.; Miele, M.M.; Li, Z.; Wang, P.; Yan, S.; et al. Targeted delivery of a PD-1-blocking scFv by CAR-T cells enhances anti-tumor efficacy in vivo. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018; 36:847-856. [CrossRef]

- de Campos, N.S.P.; de Oliveira Beserra, A.; Pereira, P.H.B.; Chaves, A.S.; Fonseca, F.L.A.; da Silva Medina, T.; Dos Santos, T.G.; Wang, Y.; Marasco, W.A.; Suarez, E.R. Immune Checkpoint Blockade via PD-L1 Potentiates More CD28-Based than 4-1BB-Based Anti-Carbonic Anhydrase IX Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022; 23:5448. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.; Townsend, M.; O’Neill, K. Tumor Microenvironment Immunosuppression: A Roadblock to CAR T-Cell Advancement in Solid Tumors. Cells. 2022; 11:3626. [CrossRef]

- Gatto, L.; Ricciotti, I.; Tosoni, A.; Di Nunno, V.; Bartolini, S.; Ranieri, L.; Franceschi, E. CAR-T cells neurotoxicity from consolidated practice in hematological malignancies to fledgling experience in CNS tumors: fill the gap. Front. Oncol. 2023; 13:1206983. [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wu, L.; Huang, C.; Liu, R.; Li, Z.; Liu, L.; Shan, B. Challenges and strategies of clinical application of CAR-T therapy in the treatment of tumors-a narrative review. Ann. Transl. Med. 2020; 8:1093. [CrossRef]

- Shah, N.N.; Fry, T.J. Mechanisms of resistance to CAR T cell therapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2019; 16:372-385. [CrossRef]

- Dagar, G.; Gupta, A.; Masoodi, T.; Nisar, S.; Merhi, M.; Hashem, S.; Chauhan, R.; Dagar, M.; Mirza, S.; Bagga, P.; et al. Harnessing the potential of CAR-T cell therapy: progress, challenges, and future directions in hematological and solid tumor treatments. J. Transl. Med. 2023; 21:449.

- Garg, P.; Pareek, S.; Kulkarni, P.; Horne, D.; Salgia, R.; Singhal, S.S. Next-Generation Immunotherapy: Advancing Clinical Applications in Cancer Treatment. J. Clin. Med. 2024; 13:6537. [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Yang, Q.; Wang, W.; Huang, J. CAR products from novel sources: a new avenue for the breakthrough in cancer immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2024; 15:1378739. [CrossRef]

- Pan, K.; Farrukh, H.; Chittepu, V.C.S.R.; Xu, H.; Pan, C.X.; Zhu, Z. CAR race to cancer immunotherapy: from CAR T, CAR NK to CAR macrophage therapy. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer. Res. 2022; 41:119. [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Sferruzza, G.; Yang, L.; Zhou, L.; Chen, S. CAR-T and CAR-NK as cellular cancer immunotherapy for solid tumors. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2024; 21:1089-1108. [CrossRef]

- Xie, G.; Dong, H.; Liang, Y.; Ham, J.D.; Rizwan, R.; Chen, J. CAR-NK cells: A promising cellular immunotherapy for cancer. EBioMedicine. 2020; 59:102975. [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Aziz, A.U.R.; Wang, D. CAR-NK Cell Therapy: A Transformative Approach to Overcoming Oncological Challenges. Biomolecules. 2024; 14:1035. [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Wu, Y.; Li, H.; Zhao, A.; Niu, T. Harmonizing efficacy and safety: the potentials of CAR-NK in effectively addressing severe toxicities of CAR-T therapy in mantle cell lymphoma. Int. J. Surg. 2024; 110:5871-5872. [CrossRef]

- Strizova, Z.; Benesova, I.; Bartolini, R.; Novysedlak, R.; Cecrdlova, E.; Foley, L.K.; Striz, I. M1/M2 macrophages and their overlaps - myth or reality? Clin Sci (Lond). 2023; 137:1067-1093.

- Heipertz, E.L.; Zynda, E.R.; Stav-Noraas, T.E.; Hungler, A.D.; Boucher, S.E.; Kaur, N.; Vemuri, M.C. Current Perspectives on “Off-The-Shelf” Allogeneic NK and CAR-NK Cell Therapies. Front. Immunol. 2021; 12:732135.

- Berrien-Elliott, M.M.; Jacobs, M.T.; Fehniger, T.A. Allogeneic natural killer cell therapy. Blood. 2023; 141:856-868. [CrossRef]

- Maia, A.; Tarannum, M.; Romee, R. Genetic Manipulation Approaches to Enhance the Clinical Application of NK Cell-Based Immunotherapy. Stem. Cells. Transl. Med. 2024; 13:230-242. [CrossRef]

- Robbins, G.M.; Wang, M.; Pomeroy, E.J.; Moriarity, B.S. Nonviral genome engineering of natural killer cells. Stem. Cell. Res. Ther. 2021;12:350. [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Kantor, B. Lentiviral Vectors for Delivery of Gene-Editing Systems Based on CRISPR/Cas: Current State and Perspectives. Viruses. 2021; 13:1288. [CrossRef]

- Chong, Z.X.; Yeap, S.K.; Ho, W.Y. Transfection types, methods and strategies: a technical review. PeerJ. 2021; 9:e11165. [CrossRef]

- Ucha, M.; Štach, M.; Kaštánková, I.; Rychlá, J.; Vydra, J.; Lesný, P.; Otáhal, P. Good manufacturing practice-grade generation of CD19 and CD123-specific CAR-T cells using piggyBac transposon and allogeneic feeder cells in patients diagnosed with B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma and acute myeloid leukemia. Front. Immunol. 2024; 15:1415328. [CrossRef]

- Wrona, E.; Borowiec, M.; Potemski, P. CAR-NK Cells in the Treatment of Solid Tumors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021; 22:5899. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y. The Function of NK Cells in Tumor Metastasis and NK Cell-Based Immunotherapy. Cancers (Basel). 2023; 15:2323. [CrossRef]

- Khawar, M.B.; Sun, H. CAR-NK Cells: From Natural Basis to Design for Kill. Front. Immunol. 2021; 12:707542. [CrossRef]

- Teng, R.; Wang, Y.; Lv, N.; Zhang, D.; Williamson, R.A.; Lei, L.; Chen, P.; Lei, L.; Wang, B.; Fu, J.; et al. Hypoxia Impairs NK Cell Cytotoxicity through SHP-1-Mediated Attenuation of STAT3 and ERK Signaling Pathways. J. Immunol. Res. 2020; 2020:4598476. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Han, F.; Du, Y.; Shi, H.; Zhou, W. Hypoxic microenvironment in cancer: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic interventions. Signal. Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023; 8:70. [CrossRef]

- Riggan, L.; Shah, S.; O’Sullivan, T.E. Arrested development: suppression of NK cell function in the tumor microenvironment. Clin. Transl. Immunology. 2021; 10:e1238. [CrossRef]

- Tian, T.; Li, X.; Zhang, J. mTOR Signaling in Cancer and mTOR Inhibitors in Solid Tumor Targeting Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019; 20:755. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, G.; Chai, D.; Dang, Y.; Zheng, J.; Li, H. iNKT: A new avenue for CAR-based cancer immunotherapy. Transl. Oncol. 2022; 17:101342. [CrossRef]

- Hadiloo, K.; Tahmasebi, S.; Esmaeilzadeh, A. CAR-NKT cell therapy: a new promising paradigm of cancer immunotherapy. Cancer. Cell. Int. 2023; 23:86. [CrossRef]

- Carreño, L.J.; Saavedra-Ávila, N.A.; Porcelli, S.A. Synthetic glycolipid activators of natural killer T cells as immunotherapeutic agents. Clin. Transl. Immunology. 2016; 5:e69. [CrossRef]

- Kitayama, S.; Zhang, R.; Liu, T.Y.; Ueda, N.; Iriguchi, S.; Yasui, Y.; Kawai, Y.; Tatsumi, M.; Hirai, N.; Mizoro, Y.; et al. Cellular Adjuvant Properties, Direct Cytotoxicity of Re-differentiated Vα24 Invariant NKT-like Cells from Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. Stem. Cell. Reports. 2016; 6:213-227.

- Kim, S.; Lalani, S.; Parekh, V.V.; Wu, L.; Van Kaer, L. Glycolipid ligands of invariant natural killer T cells as vaccine adjuvants. Expert. Rev. Vaccines. 2008; 7:1519-1532. [CrossRef]

- Hung, J.T.; Huang, J.R.; Yu, A.L. Tailored design of NKT-stimulatory glycolipids for polarization of immune responses. J. Biomed. Sci. 2017; 24:22. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Dang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Liu, L.; Cai, W.; Li, L.; Fang, L.; Wang, M.; Xu, S.; Wang, G.; et al. IL-21-armored B7H3 CAR-iNKT cells exert potent antitumor effects. iScience. 2023; 27:108597.

- Maas-Bauer, K.; Lohmeyer, J.K.; Hirai, T.; Ramos, T.L.; Fazal, F.M.; Litzenburger, U.M.; Yost, K.E.; Ribado, J.V.; Kambham, N.; Wenokur, A.S.; et al. Invariant natural killer T-cell subsets have diverse graft-versus-host-disease-preventing and antitumor effects. Blood. 2021; 138:858-870. [CrossRef]

- Matsuda, J.L.; Mallevaey, T.; Scott-Browne, J.; Gapin, L.; CD1d-restricted iNKT cells, the ’Swiss-Army knife’ of the immune system. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2008; 20:358-368.

- Li, Y.R.; Zeng, S.; Dunn, Z.S.; Zhou, Y.; Li, Z.; Yu, J.; Wang, Y.C.; Ku, J.; Cook, N.; Kramer, A.; Yang, L. Off-the-shelf third-party HSC-engineered iNKT cells for ameliorating GvHD while preserving GvL effect in the treatment of blood cancers. iScience. 2022; 25:104859. [CrossRef]

- Sim, G.C.; Radvanyi, L. The IL-2 cytokine family in cancer immunotherapy. Cytokine. Growth. Factor. Rev. 2014; 25:377-390. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Lundqvist, A. Immunomodulatory Effects of IL-2 and IL-15; Implications for Cancer Immunotherapy. Cancers (Basel). 2020; 12:3586. [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Bei, C.; Hu, Z.; Li, Y. CAR-macrophage: Breaking new ground in cellular immunotherapy. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 2024; 12:1464218. [CrossRef]

- Meng, S.; Hara, T.; Miura, Y.; Ishii, H. Fibroblast activation protein constitutes a novel target of chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy in solid tumors. Cancer. Sci. 2024; 115:3532-3542. [CrossRef]

- Feng, F.; Shen, J.; Qi, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Ni, S. Empowering brain tumor management: chimeric antigen receptor macrophage therapy. Theranostics. 2024; 14:5725-5742. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Saeed, A.F.U.H.; Liu, Q.; Jiang, Q.; Xu, H.; Xiao, G.G.; Rao, L.; Duo, Y. Macrophages in immunoregulation and therapeutics. Signal. Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023; 8:207. [CrossRef]

- Herb, M.; Schatz, V.; Hadrian, K.; Hos, D.; Holoborodko, B.; Jantsch, J.; Brigo, N. Macrophage variants in laboratory research: most are well done, but some are RAW. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024; 14:1457323. [CrossRef]

- Moroni, F.; Dwyer, B.J.; Graham, C.; Pass, C.; Bailey, L.; Ritchie, L.; Mitchell, D.; Glover, A.; Laurie, A.; Doig, S.; et al. Safety profile of autologous macrophage therapy for liver cirrhosis. Nat. Med. 2019; 25:1560-1565. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, L.; Dunmall, L.C.; Wang, Y.Y.; Fan, Z.; Cheng, Z.; Wang, Y. The dilemmas and possible solutions for CAR-T cell therapy application in solid tumors. Cancer. Lett. 2024; 591:216871. [CrossRef]

- Hadiloo, K.; Taremi, S.; Heidari, M.; Esmaeilzadeh, A. The CAR macrophage cells, a novel generation of chimeric antigen-based approach against solid tumors. Biomark. Res. 2023; 11:103. [CrossRef]

- Giorgioni, L.; Ambrosone, A.; Cometa, M.F.; Salvati, A.L.; Nisticò, R.; Magrelli, A. Revolutionizing CAR T-Cell Therapies: Innovations in Genetic Engineering and Manufacturing to Enhance Efficacy and Accessibility. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024; 25:10365. [CrossRef]

- Amiri, M.; Moaveni, A.K.; Majidi Zolbin, M.; Shademan, B.; Nourazarian, A. Optimizing cancer treatment: the synergistic potential of CAR-T cell therapy and CRISPR/Cas9. Front. Immunol. 2024; 15:1462697. [CrossRef]

| Current Challenges | Strategies |

|

Engineering methods for CAR T-cell recruitment • Chemokine receptors employed to direct T cell movement into solid tumors and particular anatomical niches encompass CXCR1, CXCR2, CXCR4, CXCR6, CCR2, CCR4, CCR8, and CX3CR1 [59] • Non-tumor specificity of chemokines can induce toxicity and diminished activity • Radiation and oncolytic virus intra-tumoral administration were studied [60] • Neuroblastoma combination treatment is promising • Enhancing tumor receptivity and overcoming physical limitations are sought |

|

CAR T-cells in hypoxic TMEs [61] • Over-proliferation and microvasculature in tumor cells challenge CAR-T cells • Hypoxic conditions activate hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) proteins, enhancing immune checkpoint expression and Treg recruitment • HIF1 stabilization increases glycolytic enzyme production, decreases oxidative phosphorylation, and enhances VEGF expression • Interventions to enhance HIF include HIF-CAR, HiCAR, and HypoxiCAR, which are hypoxic sensitive [62] |

|

Enhanced anti-tumor effects of hypoxic tumor mesenchymal stem cells • RIAD-CAR and BAY 60-6583 are used for enhanced anti-tumor effects [63] • Lactate dehydrogenase blockade explored alongside CAR T-cell immunotherapy [64] • Optimizing CAR T-cell metabolism, including PD-1/PD-L1 axis blockade, GLUT-1 inhibitors, and CRISPR/Cas9 technology, crucial for tumor metastasis treatment [65] |

|

CD19-specific CAR-T cells and hematologic malignancies • CD19-specific CAR-T cells show better outcomes in hematologic malignancies • CD38 inhibition improves memory differentiation and counteracts CAR-T cell exhaustion [66] • Exhausted CAR T-cells in TME upregulated PD-1, TOX, NR4A, CBL-B, and TGF-β [67] • The combination of PD-1 blockade and scFv engineering demonstrates promising outcomes [68,69] |

|

Innovative engineering strategies to enhance CAR T-cell effectiveness in solid tumors • Targeting multiple tumor-associated antigens • Co-expressing and secreting BiTEs using CAR-T cells • Applying CARs targeting adapter molecules • BiTE-secreting CAR T-cells successfully overcome antigen heterogeneity • Universal CARs use adaptor elements as ligands • Vaccines, including viruses or dendritic cells, activate CAR-T cells in vivo, with nanoparticles or oncolytic viruses modified to carry drugs, genes, or stimulatory cytokines [65] |

|

CAR-T cell therapy resistance to TME-induced immunosuppression [70] • Disrupts the function of immunosuppressive cytokines and their associated signaling pathways. • Enhances the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines • Depletes immune suppressor cells in tumor microenvironment. • Strategies include blocking inhibitory pathways, releasing mAbs, and targeting CD-47 • The risk of grade 3 neurotoxicity and cytokine release syndrome in CAR-T cell therapy for solid tumors varies across studies, with severe neurotoxicity occurring in 21.7% of patients |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).