Submitted:

13 January 2025

Posted:

14 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

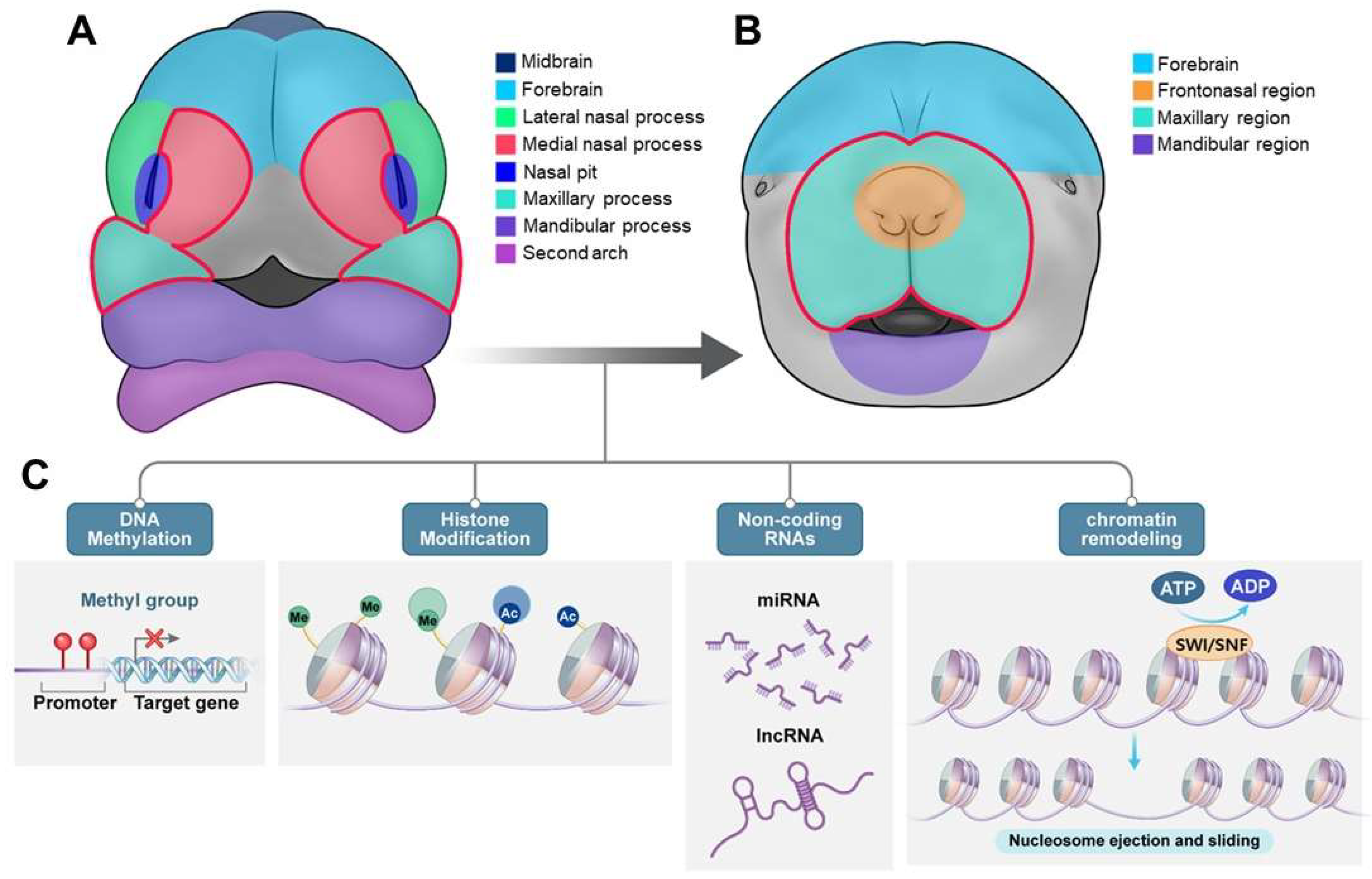

2. Craniofacial Development: Molecular and Genetic Basis

2.1. Anatomical Development and Classification of Cleft Lip and/or Palate (CL/P)

2.1.1. Anatomical Overview of Palate Formation

2.1.2. Classification of Human Cleft Lip and/or Palate

- -

- Incomplete cleft lip (smaller gap)

- -

- Complete cleft lip (full width of upper lip)

- -

- Median cleft lip (rarely middle upper lip)

- -

- Complete cleft palate involves both hard and soft palates.

- -

- An incomplete cleft palate encompasses both hard and soft palates.

- -

- Submucous cleft palate: involves a small opening in the soft palate, with the mucous membrane remaining intact [1].

3. The Pathogenesis of Orofacial Clefts in Humans Involves Genetic and Environmental Factors

3.1. Overview of Syndromic/Non-Syndromic Associated with Cleft Lip and/or Palate

3.2. The Genetic and Epigenetic Basis of Craniofacial Abnormalities: Non-Syndromic and Syndromic Forms

3.2.1. Non-Syndromic Craniofacial Anomalies

3.2.2. Syndromic Craniofacial Anomalies

DiGeorge Syndrome

Van der Woude Syndrome

Stickler Syndrome

Pierre-Robin Syndrome (PRS)

Kabuki Syndrome

Wolf-Hirschhorn Syndrome

CHARGE Syndrome

Apert Syndrome

Tatton-Brown-Rahman Syndrome

Arboleda-Tham Syndrome

3.3. Key Genes Involved in Craniofacial Development

3.3.1. Morphological and Molecular Control of Palatal Shelf Growth and Patterning

3.3.2. Molecular Regulation and Regional Patterning Along the Anterior-Posterior Axis of Palatal Development

3.3.3. Regulatory Networks and Patterning Along the Mediolateral Axis

3.3.4. Genetic Network Controlling Palatal Shelf Adhesion and Fusion

3.4. Epigenetic Mechanisms Landscape in Palatogenesis: Molecular Dynamics and Developmental Regulation

3.4.1. Overall Epigenetic Modifications in Development

3.4.2. DNA Methylation Dynamics in Palatogenesis and Craniofacial Development

3.4.3. Epigenome-Wide Association Studies (EWAS) in Orofacial Clefts (OFCs)

3.4.4. Impacts of Histone Modifications in Craniofacial Development

Histone H3K27me3 Demethylase KDM6A, KDM6B

Histone H3 Lysine 4 Methyltransferase KMT2D

Histone-Lysine Demethylase PHF8

Histone-Lysine N-Methyltransferase MECOM (PRDM3)

Histone-Lysine N-Methyltransferase PRDM16

Arginine Methyltransferase PRMT1

Histone Methyltransferase WHSC1

Histone Deacetylases HDAC3 and HDAC4

Histone Acetyltransferase KAT6A

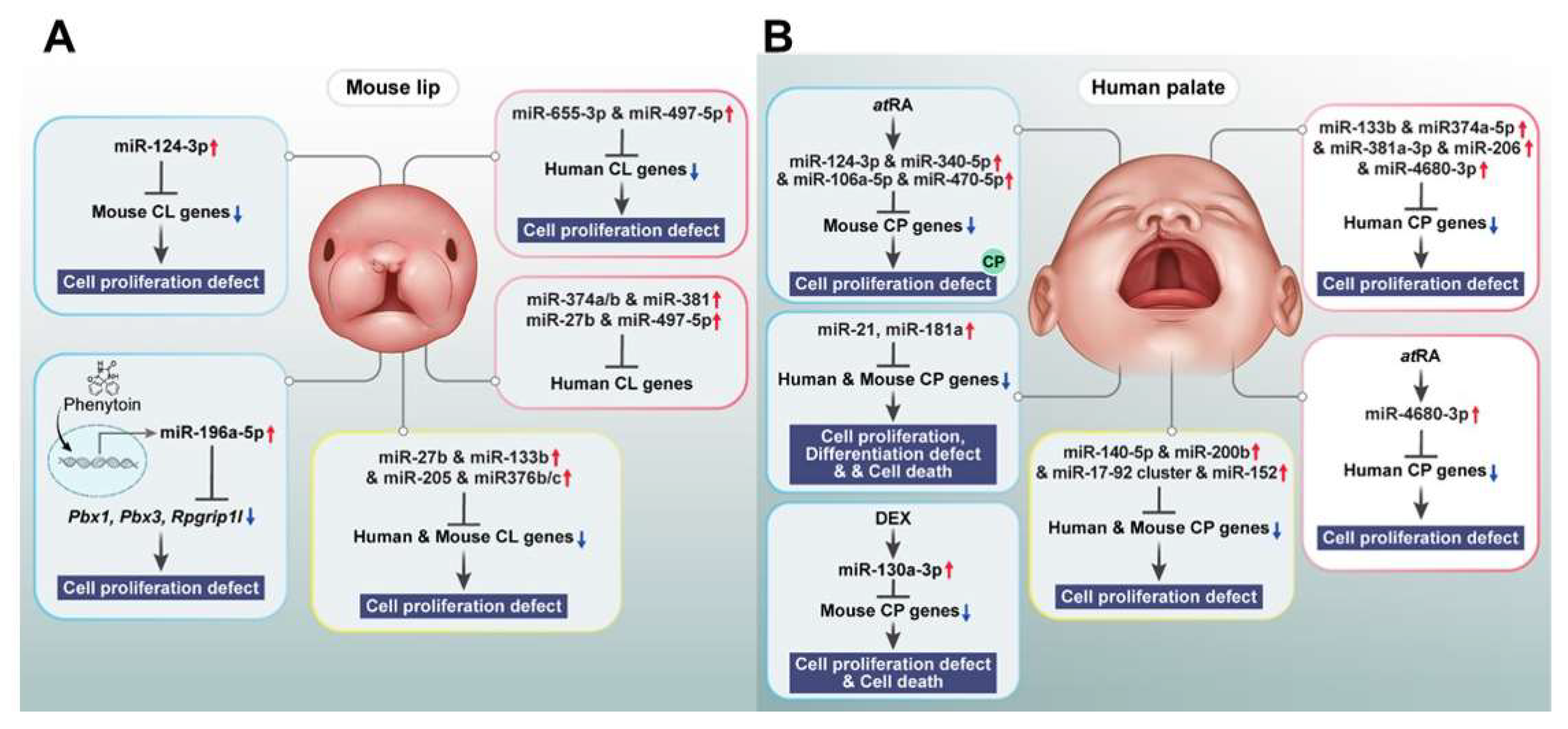

3.4.5. Non-Coding RNAs in Craniofacial Development and Orofacial Clefts

3.4.6. Epigenetic Regulation in Chromatin Organization and Craniofacial Development

3.4.7. Environmental Influences on Epigenetics and Craniofacial Development

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Declaration of Competing Interest

References

- Won, H.-J.; Kim, J.-W.; Won, H.-S.; Shin, J.-O., Gene regulatory networks and signaling pathways in palatogenesis and cleft palate: a comprehensive review. Cells 2023, 12, (15), 1954. [CrossRef]

- Bush, J. O.; Jiang, R., Palatogenesis: morphogenetic and molecular mechanisms of secondary palate development. Development 2012, 139, (2), 231-243. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, R.; Bush, J. O.; Lidral, A. C., Development of the upper lip: morphogenetic and molecular mechanisms. Developmental dynamics: an official publication of the American Association of Anatomists 2006, 235, (5), 1152-1166.

- Yuzuriha, S.; Oh, A. K.; Mulliken, J. B., Asymmetrical bilateral cleft lip: Complete or incomplete and contralateral lesser defect (minor-form, microform, or mini-microform). Plastic and reconstructive surgery 2008, 122, (5), 1494-1504. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasreddine, G.; El Hajj, J.; Ghassibe-Sabbagh, M., Orofacial clefts embryology, classification, epidemiology, and genetics. Mutation Research/Reviews in Mutation Research 2021, 787, 108373.

- Rahimov, F.; Jugessur, A.; Murray, J. C., Genetics of nonsyndromic orofacial clefts. The Cleft palate-craniofacial journal 2012, 49, (1), 73-91.

- Yılmaz, H. N.; Özbilen, E. Ö.; Üstün, T., The prevalence of cleft lip and palate patients: a single-center experience for 17 years. Turkish journal of orthodontics 2019, 32, (3), 139. [CrossRef]

- Garland, M. A.; Sun, B.; Zhang, S.; Reynolds, K.; Ji, Y.; Zhou, C. J., Role of epigenetics and miRNAs in orofacial clefts. Birth Defects Res 2020, 112, (19), 1635-1659. [CrossRef]

- Alade, A.; Awotoye, W.; Butali, A., Genetic and epigenetic studies in non-syndromic oral clefts. Oral Dis 2022, 28, (5), 1339-1350. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mani, P.; Jarrell, A.; Myers, J.; Atit, R., Visualizing canonical Wnt signaling during mouse craniofacial development. Developmental dynamics: an official publication of the American Association of Anatomists 2010, 239, (1), 354-363.

- Sharp, G.; Ho, K.; Davies, A.; Stergiakouli, E.; Humphries, K.; McArdle, W.; Relton, C., Distinct DNA methylation profiles in subtypes of orofacial cleft. Clinical Epigenetics, 9, 63. In 2017.

- Alade, A.; Mossey, P.; Awotoye, W.; Busch, T.; Oladayo, A. M.; Aladenika, E.; Olujitan, M.; Wentworth, E.; Anand, D.; Naicker, T.; Gowans, L. J. J.; Eshete, M. A.; Adeyemo, W. L.; Zeng, E.; Van Otterloo, E.; O’Rorke, M.; Adeyemo, A.; Murray, J. C.; Cotney, J.; Lachke, S. A.; Romitti, P.; Butali, A., Rare variants analyses suggest novel cleft genes in the African population. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, (1), 14279. [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, K.; Zhang, S.; Sun, B.; Garland, M. A.; Ji, Y.; Zhou, C. J., Genetics and signaling mechanisms of orofacial clefts. Birth Defects Research 2020, 112, (19), 1588-1634. [CrossRef]

- McDonald-McGinn, D. M.; Sullivan, K. E.; Marino, B.; Philip, N.; Swillen, A.; Vorstman, J. A.; Zackai, E. H.; Emanuel, B. S.; Vermeesch, J. R.; Morrow, B. E.; Scambler, P. J.; Bassett, A. S., 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2015, 1, 15071. [CrossRef]

- Seelan, R. S.; Pisano, M. M.; Greene, R. M., MicroRNAs as epigenetic regulators of orofacial development. Differentiation 2022, 124, 1-16. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, S.; Moreno, M.; Eliason, S.; Cao, H.; Li, X.; Yu, W.; Bidlack, F. B.; Margolis, H. C.; Baldini, A.; Amendt, B. A., TBX1 protein interactions and microRNA-96-5p regulation controls cell proliferation during craniofacial and dental development: implications for 22q11. 2 deletion syndrome. Human molecular genetics 2015, 24, (8), 2330-2348. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumari, P.; Singh, S. K.; Raman, R., A novel non-coding RNA within an intron of CDH2 and association of its SNP with non-syndromic cleft lip and palate. Gene 2018, 658, 123-128. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snead, M.; McNinch, A.; Poulson, A.; Bearcroft, P.; Silverman, B.; Gomersall, P.; Parfect, V.; Richards, A., Stickler syndrome, ocular-only variants and a key diagnostic role for the ophthalmologist. Eye 2011, 25, (11), 1389-1400. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzahrani, F.; Al Hazzaa, S. A.; Tayeb, H.; Alkuraya, F. S., LOXL3, encoding lysyl oxidase-like 3, is mutated in a family with autosomal recessive Stickler syndrome. Human genetics 2015, 134, 451-453. [CrossRef]

- Schrauwen, I.; Sommen, M.; Claes, C.; Pinner, J.; Flaherty, M.; Collins, F.; Van Camp, G., Broadening the phenotype of LRP2 mutations: a new mutation in LRP2 causes a predominantly ocular phenotype suggestive of Stickler syndrome. Clinical Genetics 2014, 86, (3), 282-286. [CrossRef]

- Giudice, A.; Barone, S.; Belhous, K.; Morice, A.; Soupre, V.; Bennardo, F.; Boddaert, N.; Vazquez, M.-P.; Abadie, V.; Picard, A., Pierre Robin sequence: A comprehensive narrative review of the literature over time. Journal of stomatology, oral and maxillofacial surgery 2018, 119, (5), 419-428.

- Gordon, C. T.; Attanasio, C.; Bhatia, S.; Benko, S.; Ansari, M.; Tan, T. Y.; Munnich, A.; Pennacchio, L. A.; Abadie, V.; Temple, I. K., Identification of novel craniofacial regulatory domains located far upstream of sox 9 and disrupted in pierre robin sequence. Human mutation 2014, 35, (8), 1011-1020. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yuan, J.; Yao, X.; Zhang, R.; Yang, H.; Zhao, R.; Guo, J.; Jin, K.; Mei, H.; Luo, Y., BMPR1B mutation causes Pierre Robin sequence. Oncotarget 2017, 8, (16), 25864. [CrossRef]

- Murakami, H.; Tsurusaki, Y.; Enomoto, K.; Kuroda, Y.; Yokoi, T.; Furuya, N.; Yoshihashi, H.; Minatogawa, M.; Abe-Hatano, C.; Ohashi, I., Update of the genotype and phenotype of KMT2D and KDM6A by genetic screening of 100 patients with clinically suspected Kabuki syndrome. American journal of medical genetics Part A 2020, 182, (10), 2333-2344. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barry, K. K.; Tsaparlis, M.; Hoffman, D.; Hartman, D.; Adam, M. P.; Hung, C.; Bodamer, O. A., From Genotype to Phenotype-A Review of Kabuki Syndrome. Genes (Basel) 2022, 13, (10).

- Lederer, D.; Grisart, B.; Digilio, M. C.; Benoit, V.; Crespin, M.; Ghariani, S. C.; Maystadt, I.; Dallapiccola, B.; Verellen-Dumoulin, C., Deletion of KDM6A, a histone demethylase interacting with MLL2, in three patients with Kabuki syndrome. The American Journal of Human Genetics 2012, 90, (1), 119-124. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gavril, E. C.; Luca, A. C.; Curpan, A. S.; Popescu, R.; Resmerita, I.; Panzaru, M. C.; Butnariu, L. I.; Gorduza, E. V.; Gramescu, M.; Rusu, C., Wolf-Hirschhorn Syndrome: Clinical and Genetic Study of 7 New Cases, and Mini Review. Children (Basel) 2021, 8, (9).

- Nevado, J.; Ho, K. S.; Zollino, M.; Blanco, R.; Cobaleda, C.; Golzio, C.; Beaudry-Bellefeuille, I.; Berrocoso, S.; Limeres, J.; Barrúz, P., International meeting on Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome: Update on the nosology and new insights on the pathogenic mechanisms for seizures and growth delay. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A 2020, 182, (1), 257-267. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sperry, E. D.; Hurd, E. A.; Durham, M. A.; Reamer, E. N.; Stein, A. B.; Martin, D. M., The chromatin remodeling protein CHD7, mutated in CHARGE syndrome, is necessary for proper craniofacial and tracheal development. Developmental Dynamics 2014, 243, (9), 1055-1066. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giancotti, A.; D’Ambrosio, V.; De Filippis, A.; Aliberti, C.; Pasquali, G.; Bernardo, S.; Manganaro, L.; Group, P. S., Comparison of ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging in the prenatal diagnosis of Apert syndrome: report of a case. Child's Nervous System 2014, 30, 1445-1448.

- Kakutani, H.; Sato, Y.; Tsukamoto-Takakusagi, Y.; Saito, F.; Oyama, A.; Iida, J., Evaluation of the maxillofacial morphological characteristics of Apert syndrome infants. Congenital Anomalies 2017, 57, (1), 15-23. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Letra, A.; de Almeida, A. L.; Kaizer, R.; Esper, L. A.; Sgarbosa, S.; Granjeiro, J. M., Intraoral features of Apert's syndrome. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2007, 103, (5), e38-41. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Cui, Y.; Luan, J.; Zhou, X.; Han, J., The molecular and cellular basis of Apert syndrome. Intractable & Rare Diseases Research 2013, 2, (4), 115-122.

- Yeh, E.; Atique, R.; Fanganiello, R. D.; Sunaga, D. Y.; Ishiy, F. A. A.; Passos-Bueno, M. R., Cell type-dependent nonspecific fibroblast growth factor signaling in Apert syndrome. Stem Cells and Development 2016, 25, (16), 1249-1260. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Ma, D.; Sun, Y.; Meng, L.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, T., Apert Syndrome With FGFR2 758 C > G Mutation: A Chinese Case Report. Front Genet 2018, 9, 181. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yokoi, T.; Enomoto, Y.; Naruto, T.; Kurosawa, K.; Higurashi, N., Tatton-Brown-Rahman syndrome with a novel DNMT3A mutation presented severe intellectual disability and autism spectrum disorder. Human genome variation 2020, 7, (1), 15. [CrossRef]

- Smith, A. M.; LaValle, T. A.; Shinawi, M.; Ramakrishnan, S. M.; Abel, H. J.; Hill, C. A.; Kirkland, N. M.; Rettig, M. P.; Helton, N. M.; Heath, S. E., Functional and epigenetic phenotypes of humans and mice with DNMT3A Overgrowth Syndrome. Nature communications 2021, 12, (1), 4549. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nimura, K.; Ura, K.; Shiratori, H.; Ikawa, M.; Okabe, M.; Schwartz, R. J.; Kaneda, Y., A histone H3 lysine 36 trimethyltransferase links Nkx2-5 to Wolf–Hirschhorn syndrome. Nature 2009, 460, (7252), 287-291. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mariotti, M.; Manganini, M.; Maier, J., Modulation of WHSC2 expression in human endothelial cells. FEBS letters 2000, 487, (2), 166-170. [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C. A.; Rasband, W. S.; Eliceiri, K. W., NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nature methods 2012, 9, (7), 671-675. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gergely, F.; Karlsson, C.; Still, I.; Cowell, J.; Kilmartin, J.; Raff, J. W., The TACC domain identifies a family of centrosomal proteins that can interact with microtubules. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2000, 97, (26), 14352-14357. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, J.; Goudie, D.; Blair, E.; Chandler, K.; Joss, S.; McKay, V.; Green, A.; Armstrong, R.; Lees, M.; Kamien, B.; Hopper, B.; Tan, T. Y.; Yap, P.; Stark, Z.; Okamoto, N.; Miyake, N.; Matsumoto, N.; Macnamara, E.; Murphy, J. L.; McCormick, E.; Hakonarson, H.; Falk, M. J.; Li, D.; Blackburn, P.; Klee, E.; Babovic-Vuksanovic, D.; Schelley, S.; Hudgins, L.; Kant, S.; Isidor, B.; Cogne, B.; Bradbury, K.; Williams, M.; Patel, C.; Heussler, H.; Duff-Farrier, C.; Lakeman, P.; Scurr, I.; Kini, U.; Elting, M.; Reijnders, M.; Schuurs-Hoeijmakers, J.; Wafik, M.; Blomhoff, A.; Ruivenkamp, C. A. L.; Nibbeling, E.; Dingemans, A. J. M.; Douine, E. D.; Nelson, S. F.; Hempel, M.; Bierhals, T.; Lessel, D.; Johannsen, J.; Arboleda, V. A.; Newbury-Ecob, R., KAT6A Syndrome: genotype–phenotype correlation in 76 patients with pathogenic KAT6A variants. Genetics in Medicine 2019, 21, (4), 850-860. [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Spendlove, S. J.; Wei, A.; Bondhus, L. M.; Nava, A. A.; de, L. V. F. N.; Amano, S.; Lee, J.; Echeverria, G.; Gomez, D.; Garcia, B. A.; Arboleda, V. A., KAT6A mutations in Arboleda-Tham syndrome drive epigenetic regulation of posterior HOXC cluster. Hum Genet 2023, 142, (12), 1705-1720. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, S. A.; Oram, K. F.; Gridley, T., Multiple functions of Snail family genes during palate development in mice. 2007.

- Thomas, T.; Voss, A. K., The diverse biological roles of MYST histone acetyltransferase family proteins. Cell Cycle 2007, 6, (6), 696-704. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, K.; Rousseau, J.; Machol, K.; Cross, L. A.; Agre, K. E.; Gibson, C. F.; Goverde, A.; Engleman, K. L.; Verdin, H.; De Baere, E.; Potocki, L.; Zhou, D.; Cadieux-Dion, M.; Bellus, G. A.; Wagner, M. D.; Hale, R. J.; Esber, N.; Riley, A. F.; Solomon, B. D.; Cho, M. T.; McWalter, K.; Eyal, R.; Hainlen, M. K.; Mendelsohn, B. A.; Porter, H. M.; Lanpher, B. C.; Lewis, A. M.; Savatt, J.; Thiffault, I.; Callewaert, B.; Campeau, P. M.; Yang, X. J., Deficient histone H3 propionylation by BRPF1-KAT6 complexes in neurodevelopmental disorders and cancer. Sci Adv 2020, 6, (4), eaax0021. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casey, L. M.; Lan, Y.; Cho, E. S.; Maltby, K. M.; Gridley, T.; Jiang, R., Jag2-Notch1 signaling regulates oral epithelial differentiation and palate development. Developmental dynamics: an official publication of the American Association of Anatomists 2006, 235, (7), 1830-1844.

- Ito, Y.; Yeo, J. Y.; Chytil, A.; Han, J.; Bringas Jr, P.; Nakajima, A.; Shuler, C. F.; Moses, H. L.; Chai, Y., Conditional inactivation of Tgfbr2 in cranial neural crest causes cleft palate and calvaria defects. 2003.

- Lan, Y.; Jiang, R., Mouse models in palate development and orofacial cleft research: Understanding the crucial role and regulation of epithelial integrity in facial and palate morphogenesis. In Current topics in developmental biology, Elsevier: 2022; Vol. 148, pp 13-50.

- Hammond, N. L.; Dixon, M. J., Revisiting the embryogenesis of lip and palate development. Oral Diseases 2022, 28, (5), 1306-1326. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Liu, H.; Lan, Y.; Aronow, B. J.; Kalinichenko, V. V.; Jiang, R., A Shh-Foxf-Fgf18-Shh molecular circuit regulating palate development. PLoS genetics 2016, 12, (1), e1005769. [CrossRef]

- Charoenchaikorn, K.; Yokomizo, T.; Rice, D. P.; Honjo, T.; Matsuzaki, K.; Shintaku, Y.; Imai, Y.; Wakamatsu, A.; Takahashi, S.; Ito, Y., Runx1 is involved in the fusion of the primary and the secondary palatal shelves. Developmental biology 2009, 326, (2), 392-402. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurosaka, H.; Iulianella, A.; Williams, T.; Trainor, P. A., Disrupting hedgehog and WNT signaling interactions promotes cleft lip pathogenesis. The Journal of clinical investigation 2014, 124, (4), 1660-1671. [CrossRef]

- Goetz, S. C.; Anderson, K. V., The primary cilium: a signalling centre during vertebrate development. Nature Reviews Genetics 2010, 11, (5), 331-344. [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.-O.; Song, J.; Choi, H. S.; Lee, J.; Lee, K.; Ko, H. W.; Bok, J., Activation of sonic hedgehog signaling by a Smoothened agonist restores congenital defects in mouse models of endocrine-cerebro-osteodysplasia syndrome. EBioMedicine 2019, 49, 305-317. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rice, R.; Spencer-Dene, B.; Connor, E. C.; Gritli-Linde, A.; McMahon, A. P.; Dickson, C.; Thesleff, I.; Rice, D. P., Disruption of Fgf10/Fgfr2b-coordinated epithelial-mesenchymal interactions causes cleft palate. The Journal of clinical investigation 2004, 113, (12), 1692-1700. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosokawa, R.; Deng, X.; Takamori, K.; Xu, X.; Urata, M.; Bringas Jr, P.; Chai, Y., Epithelial-specific requirement of FGFR2 signaling during tooth and palate development. Journal of Experimental Zoology Part B: Molecular and Developmental Evolution 2009, 312, (4), 343-350.

- Lan, Y.; Jiang, R., Sonic hedgehog signaling regulates reciprocal epithelial-mesenchymal interactions controlling palatal outgrowth. 2009.

- Han, J.; Mayo, J.; Xu, X.; Li, J.; Bringas Jr, P.; Maas, R. L.; Rubenstein, J. L.; Chai, Y., Indirect modulation of Shh signaling by Dlx5 affects the oral-nasal patterning of palate and rescues cleft palate in Msx1-null mice. Development 2009, 136, (24), 4225-4233. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwata, J.-i.; Tung, L.; Urata, M.; Hacia, J. G.; Pelikan, R.; Suzuki, A.; Ramenzoni, L.; Chaudhry, O.; Parada, C.; Sanchez-Lara, P. A., Fibroblast growth factor 9 (FGF9)-pituitary homeobox 2 (PITX2) pathway mediates transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) signaling to regulate cell proliferation in palatal mesenchyme during mouse palatogenesis. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2012, 287, (4), 2353-2363. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Sun, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zheng, M.; Shan, Y.; Ying, X.; Weng, M.; Chen, Z., The fibroblast growth factor 9 (Fgf9) participates in palatogenesis by promoting palatal growth and elevation. Frontiers in Physiology 2021, 12, 653040. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.; Liu, S.; Ruan, N.; Chen, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J., Cleft Palate Induced by Augmented Fibroblast Growth Factor-9 Signaling in Cranial Neural Crest Cells in Mice. Stem Cells and Development 2024, 33, (19-20), 562-573.

- Cesario, J. M.; Landin Malt, A.; Deacon, L. J.; Sandberg, M.; Vogt, D.; Tang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Brown, S.; Rubenstein, J. L.; Jeong, J., Lhx6 and Lhx8 promote palate development through negative regulation of a cell cycle inhibitor gene, p57Kip2. Human molecular genetics 2015, 24, (17), 5024-5039. [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Ieong, H. C.; Li, R.; Huang, D.; Chen, D.; Chen, X.; Guo, Y.; Qing, Y.; Guo, B.; Li, R.; Teng, Y.; Li, W.; Cao, Y.; Zhou, C.; Wang, W., Lhx6 deficiency causes human embryonic palatal mesenchymal cell mitophagy dysfunction in cleft palate. Mol Med 2024, 30, (1), 183. [CrossRef]

- Iwata, J.-i.; Suzuki, A.; Yokota, T.; Ho, T.-V.; Pelikan, R.; Urata, M.; Sanchez-Lara, P. A.; Chai, Y., TGFβ regulates epithelial-mesenchymal interactions through WNT signaling activity to control muscle development in the soft palate. Development 2014, 141, (4), 909-917. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Sun, X.; Braut, A.; Mishina, Y.; Behringer, R. R.; Mina, M.; Martin, J. F., Distinct functions for Bmp signaling in lip and palate fusion in mice. 2005.

- Ueharu, H.; Mishina, Y., BMP signaling during craniofacial development: new insights into pathological mechanisms leading to craniofacial anomalies. Frontiers in Physiology 2023, 14, 1170511. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammond, N. L.; Brookes, K. J.; Dixon, M. J., Ectopic hedgehog signaling causes cleft palate and defective osteogenesis. Journal of dental research 2018, 97, (13), 1485-1493. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Song, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, X.; Fermin, C.; Chen, Y., Rescue of cleft palate in Msx1-deficient mice by transgenic Bmp4 reveals a network of BMP and Shh signaling in the regulation of mammalian palatogenesis. 2002.

- Saket, M.; Saliminejad, K.; Kamali, K.; Moghadam, F. A.; Anvar, N. E.; Khorshid, H. R. K., BMP2 and BMP4 variations and risk of non-syndromic cleft lip and palate. Archives of Oral Biology 2016, 72, 134-137. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, W.; He, F.; Morikawa, Y.; Yu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Lan, Y.; Jiang, R.; Cserjesi, P.; Chen, Y., Hand2 is required in the epithelium for palatogenesis in mice. Developmental biology 2009, 330, (1), 131-141. [CrossRef]

- Parada, C.; Chai, Y., Roles of BMP signaling pathway in lip and palate development. Cleft Lip and Palate 2012, 16, 60-70.

- Andl, T.; Ahn, K.; Kairo, A.; Chu, E. Y.; Wine-Lee, L.; Reddy, S. T.; Croft, N. J.; Cebra-Thomas, J. A.; Metzger, D.; Chambon, P., Epithelial Bmpr1a regulates differentiation and proliferation in postnatal hair follicles and is essential for tooth development. 2004.

- Li, L.; Lin, M.; Wang, Y.; Cserjesi, P.; Chen, Z.; Chen, Y., BmprIa is required in mesenchymal tissue and has limited redundant function with BmprIb in tooth and palate development. Developmental biology 2011, 349, (2), 451-461. [CrossRef]

- Baek, J.-A.; Lan, Y.; Liu, H.; Maltby, K. M.; Mishina, Y.; Jiang, R., Bmpr1a signaling plays critical roles in palatal shelf growth and palatal bone formation. Developmental biology 2011, 350, (2), 520-531. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, F.; Xiong, W.; Wang, Y.; Matsui, M.; Yu, X.; Chai, Y.; Klingensmith, J.; Chen, Y., Modulation of BMP signaling by Noggin is required for the maintenance of palatal epithelial integrity during palatogenesis. Developmental biology 2010, 347, (1), 109-121. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Lan, Y.; Krumlauf, R.; Jiang, R., Modulating Wnt signaling rescues palate morphogenesis in Pax9 mutant mice. Journal of dental research 2017, 96, (11), 1273-1281. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, S.; Zhou, J.; Fanelli, C.; Wee, Y.; Bonds, J.; Schneider, P.; Mues, G.; D'Souza, R. N., Small-molecule Wnt agonists correct cleft palates in Pax9 mutant mice in utero. Development 2017, 144, (20), 3819-3828. [CrossRef]

- Jia, S.; Zhou, J.; Wee, Y.; Mikkola, M.; Schneider, P.; D’souza, R., Anti-EDAR agonist antibody therapy resolves palate defects in Pax9-/-mice. Journal of dental research 2017, 96, (11), 1282-1289. [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, K.; Kumari, P.; Sepulveda Rincon, L.; Gu, R.; Ji, Y.; Kumar, S.; Zhou, C. J., Wnt signaling in orofacial clefts: crosstalk, pathogenesis and models. Disease models & mechanisms 2019, 12, (2), dmm037051.

- Yao, T.; Yang, L.; Li, P.-q.; Wu, H.; Xie, H.-b.; Shen, X.; Xie, X.-d., Association of Wnt3A gene variants with non-syndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate in Chinese population. Archives of Oral Biology 2011, 56, (1), 73-78. [CrossRef]

- Zhan, T.; Rindtorff, N.; Boutros, M., Wnt signaling in cancer. Oncogene 2017, 36, (11), 1461-1473. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huybrechts, Y.; Mortier, G.; Boudin, E.; Van Hul, W., WNT signaling and bone: lessons from skeletal dysplasias and disorders. Frontiers in Endocrinology 2020, 11, 165. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilliard, S. A.; Yu, L.; Gu, S.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, Y. P., Regional regulation of palatal growth and patterning along the anterior–posterior axis in mice. Journal of anatomy 2005, 207, (5), 655-667. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Lan, Y.; Pauws, E.; Meester-Smoor, M. A.; Stanier, P.; Zwarthoff, E. C.; Jiang, R., The Mn1 transcription factor acts upstream of Tbx22 and preferentially regulates posterior palate growth in mice. 2008.

- Yu, L.; Gu, S.; Alappat, S.; Song, Y.; Yan, M.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, G.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y., Shox2-deficient mice exhibit a rare type of incomplete clefting of the secondary palate. 2005.

- Nishihara, H.; Kobayashi, N.; Kimura-Yoshida, C.; Yan, K.; Bormuth, O.; Ding, Q.; Nakanishi, A.; Sasaki, T.; Hirakawa, M.; Sumiyama, K., Coordinately co-opted multiple transposable elements constitute an enhancer for wnt5a expression in the mammalian secondary palate. PLoS genetics 2016, 12, (10), e1006380. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almaidhan, A.; Cesario, J.; Landin Malt, A.; Zhao, Y.; Sharma, N.; Choi, V.; Jeong, J., Neural crest-specific deletion of Ldb1 leads to cleft secondary palate with impaired palatal shelf elevation. BMC Developmental Biology 2014, 14, 1-10. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Gao, Y.; Lan, Y.; Jia, S.; Jiang, R., Pax9 regulates a molecular network involving Bmp4, Fgf10, Shh signaling and the Osr2 transcription factor to control palate morphogenesis. Development 2013, 140, (23), 4709-4718. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Lan, Y.; Ovitt, C. E.; Jiang, R., Functional equivalence of the zinc finger transcription factors Osr1 and Osr2 in mouse development. Developmental biology 2009, 328, (2), 200-209. [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Xu, J.; Chaturvedi, P.; Liu, H.; Jiang, R.; Lan, Y., Identification of Osr2 transcriptional target genes in palate development. Journal of dental research 2017, 96, (12), 1451-1458. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, R. J.; Dixon, J.; Malhotra, S.; Hardman, M. J.; Knowles, L.; Boot-Handford, R. P.; Shore, P.; Whitmarsh, A.; Dixon, M. J., Irf6 is a key determinant of the keratinocyte proliferation-differentiation switch. Nature genetics 2006, 38, (11), 1329-1334. [CrossRef]

- Richardson, R. J.; Dixon, J.; Jiang, R.; Dixon, M. J., Integration of IRF6 and Jagged2 signalling is essential for controlling palatal adhesion and fusion competence. Human molecular genetics 2009, 18, (14), 2632-2642. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomason, H. A.; Zhou, H.; Kouwenhoven, E. N.; Dotto, G.-P.; Restivo, G.; Nguyen, B.-C.; Little, H.; Dixon, M. J.; Van Bokhoven, H.; Dixon, J., Cooperation between the transcription factors p63 and IRF6 is essential to prevent cleft palate in mice. The Journal of clinical investigation 2010, 120, (5), 1561-1569. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Candi, E.; Rufini, A.; Terrinoni, A.; Giamboi-Miraglia, A.; Lena, A. M.; Mantovani, R.; Knight, R.; Melino, G., ΔNp63 regulates thymic development through enhanced expression of FgfR2 and Jag2. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2007, 104, (29), 11999-12004. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, R. J.; Hammond, N. L.; Coulombe, P. A.; Saloranta, C.; Nousiainen, H. O.; Salonen, R.; Berry, A.; Hanley, N.; Headon, D.; Karikoski, R., Periderm prevents pathological epithelial adhesions during embryogenesis. The Journal of clinical investigation 2014, 124, (9), 3891-3900. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sani, F. V.; Hallberg, K.; Harfe, B. D.; McMahon, A. P.; Linde, A.; Gritli-Linde, A., Fate-mapping of the epithelial seam during palatal fusion rules out epithelial–mesenchymal transformation. Developmental biology 2005, 285, (2), 490-495. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Han, J.; Ito, Y.; Bringas Jr, P.; Urata, M. M.; Chai, Y., Cell autonomous requirement for Tgfbr2 in the disappearance of medial edge epithelium during palatal fusion. Developmental biology 2006, 297, (1), 238-248. [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.-Z.; Ding, J., Analysis of cell migration, transdifferentiation and apoptosis during mouse secondary palate fusion. 2006.

- Lee, S.; Sears, M. J.; Zhang, Z.; Li, H.; Salhab, I.; Krebs, P.; Xing, Y.; Nah, H. D.; Williams, T.; Carstens, R. P., Cleft lip and cleft palate in Esrp1 knockout mice is associated with alterations in epithelial-mesenchymal crosstalk. Development 2020, 147, (21).

- Caetano da Silva, C.; Macias Trevino, C.; Mitchell, J.; Murali, H.; Tsimbal, C.; Dalessandro, E.; Carroll, S. H.; Kochhar, S.; Curtis, S. W.; Cheng, C. H. E.; Wang, F.; Kutschera, E.; Carstens, R. P.; Xing, Y.; Wang, K.; Leslie, E. J.; Liao, E. C., Functional analysis of ESRP1/2 gene variants and CTNND1 isoforms in orofacial cleft pathogenesis. Communications Biology 2024, 7, (1), 1040. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cecconi, F.; Alvarez-Bolado, G.; Meyer, B. I.; Roth, K. A.; Gruss, P., Apaf1 (CED-4 homolog) regulates programmed cell death in mammalian development. Cell 1998, 94, (6), 727-737. [CrossRef]

- Jin, J. Z.; Ding, J., Analysis of Meox-2 mutant mice reveals a novel postfusion-based cleft palate. Developmental dynamics: an official publication of the American Association of Anatomists 2006, 235, (2), 539-546.

- Shiomi, N.; Cui, X. M.; Yamamoto, T.; Saito, T.; Shuler, C. F., Inhibition of SMAD2 expression prevents murine palatal fusion. Developmental Dynamics: An Official Publication of the American Association of Anatomists 2006, 235, (7), 1785-1793.

- Iwata, J.-i.; Suzuki, A.; Pelikan, R. C.; Ho, T.-V.; Sanchez-Lara, P. A.; Urata, M.; Dixon, M. J.; Chai, Y., Smad4-Irf6 genetic interaction and TGFβ-mediated IRF6 signaling cascade are crucial for palatal fusion in mice. Development 2013, 140, (6), 1220-1230. [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.-O.; Lee, J.-M.; Bok, J.; Jung, H.-S., Inhibition of the Zeb family prevents murine palatogenesis through regulation of apoptosis and the cell cycle. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 2018, 506, (1), 223-230. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, J. Z.; Warner, D. R.; Lu, Q.; Pisano, M. M.; Greene, R. M.; Ding, J., Deciphering TGF-β3 function in medial edge epithelium specification and fusion during mouse secondary palate development. Developmental Dynamics 2014, 243, (12), 1536-1543. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, F.; Xiong, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, L.; Liu, C.; Yamagami, T.; Taketo, M. M.; Zhou, C.; Chen, Y., Epithelial Wnt/β-catenin signaling regulates palatal shelf fusion through regulation of Tgfβ3 expression. Developmental biology 2011, 350, (2), 511-519. [CrossRef]

- Ke, C.-Y.; Xiao, W.-L.; Chen, C.-M.; Lo, L.-J.; Wong, F.-H., IRF6 is the mediator of TGFβ3 during regulation of the epithelial mesenchymal transition and palatal fusion. Scientific reports 2015, 5, (1), 12791. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serrano, M. J.; Liu, J.; Svoboda, K. K.; Nawshad, A.; Benson, M. D., Ephrin reverse signaling mediates palatal fusion and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition independently of Tgfss3. Journal of cellular physiology 2015, 230, (12), 2961-2972. [CrossRef]

- Mima, J.; Koshino, A.; Oka, K.; Uchida, H.; Hieda, Y.; Nohara, K.; Kogo, M.; Chai, Y.; Sakai, T., Regulation of the epithelial adhesion molecule CEACAM1 is important for palate formation. PloS one 2013, 8, (4), e61653. [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, A.; F. Shuler, C.; Gulka, A. O.; Hanai, J.-i., TGF-β signaling and the epithelial-mesenchymal transition during palatal fusion. International journal of molecular sciences 2018, 19, (11), 3638. [CrossRef]

- Iwata, J.-i.; Parada, C.; Chai, Y., The mechanism of TGF-β signaling during palate development. Oral diseases 2011, 17, (8), 733-744. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seaberg, A.; Awotoye, W.; Qian, F.; Machado-Paula, L. A.; Dunlay, L.; Butali, A.; Murray, J.; Moreno-Uribe, L.; Petrin, A. L., DNA Methylation Effects on Van der Woude Syndrome Phenotypic Variability. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 2024, 10556656241269495. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shull, L. C.; Artinger, K. B., Epigenetic regulation of craniofacial development and disease. Birth Defects Research 2024, 116, (1), e2271. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allis, C. D.; Jenuwein, T., The molecular hallmarks of epigenetic control. Nature Reviews Genetics 2016, 17, (8), 487-500. [CrossRef]

- Bannister, A. J.; Kouzarides, T., Regulation of chromatin by histone modifications. Cell research 2011, 21, (3), 381-395. [CrossRef]

- Godini, R.; Lafta, H. Y.; Fallahi, H., Epigenetic modifications in the embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cells. Gene Expression Patterns 2018, 29, 1-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horvath, S., DNA methylation age of human tissues and cell types. Genome biology 2013, 14, 1-20. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jambhekar, A.; Dhall, A.; Shi, Y., Roles and regulation of histone methylation in animal development. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology 2019, 20, (10), 625-641. [CrossRef]

- Seelan, R. S.; Pisano, M.; Greene, R. M., Nucleic acid methylation and orofacial morphogenesis. Birth Defects Research 2019, 111, (20), 1593-1610. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Blumenthal, R. M., Mediating and maintaining methylation while minimizing mutation: Recent advances on mammalian DNA methyltransferases. Current opinion in structural biology 2022, 75, 102433. [CrossRef]

- Moore, L. D.; Le, T.; Fan, G., DNA methylation and its basic function. Neuropsychopharmacology 2013, 38, (1), 23-38. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, Q.; Luu, P.-L.; Stirzaker, C.; Clark, S. J., Methyl-CpG-binding domain proteins: readers of the epigenome. Epigenomics 2015, 7, (6), 1051-1073. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, P. A., Functions of DNA methylation: islands, start sites, gene bodies and beyond. Nature reviews genetics 2012, 13, (7), 484-492. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whalen, S.; Truty, R. M.; Pollard, K. S., Enhancer–promoter interactions are encoded by complex genomic signatures on looping chromatin. Nature genetics 2016, 48, (5), 488-496. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ong, C. T.; Corces, V. G., Enhancers: emerging roles in cell fate specification. EMBO reports 2012, 13, (5), 423-430. [CrossRef]

- Blattler, A.; Yao, L.; Witt, H.; Guo, Y.; Nicolet, C. M.; Berman, B. P.; Farnham, P. J., Global loss of DNA methylation uncovers intronic enhancers in genes showing expression changes. Genome Biology 2014, 15, (9), 469. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geula, S.; Moshitch-Moshkovitz, S.; Dominissini, D.; Mansour, A. A.; Kol, N.; Salmon-Divon, M.; Hershkovitz, V.; Peer, E.; Mor, N.; Manor, Y. S., m6A mRNA methylation facilitates resolution of naïve pluripotency toward differentiation. Science 2015, 347, (6225), 1002-1006. [CrossRef]

- Khan, M. F. J.; Little, J.; Aleotti, V.; Mossey, P. A.; Steegers-Theunissen, R. P.; Autelitano, L.; Meazzini, M. C.; Ravaei, A.; Rubini, M., LINE-1 methylation in cleft lip tissues: Influence of infant MTHFR c. 677C> T genotype. Oral Diseases 2019, 25, (6), 1668-1671.

- Douvlataniotis, K.; Bensberg, M.; Lentini, A.; Gylemo, B.; Nestor, C. E., No evidence for DNA N 6-methyladenine in mammals. Science advances 2020, 6, (12), eaay3335. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musheev, M. U.; Baumgärtner, A.; Krebs, L.; Niehrs, C., The origin of genomic N 6-methyl-deoxyadenosine in mammalian cells. Nature chemical biology 2020, 16, (6), 630-634. [CrossRef]

- Altun, G.; Loring, J. F.; Laurent, L. C., DNA methylation in embryonic stem cells. Journal of cellular biochemistry 2010, 109, (1), 1-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, N.; Strobl-Mazzulla, P.; Sauka-Spengler, T.; Bronner, M. E., DNA methyltransferase3A as a molecular switch mediating the neural tube-to-neural crest fate transition. Genes & development 2012, 26, (21), 2380-2385.

- Rai, K.; Jafri, I. F.; Chidester, S.; James, S. R.; Karpf, A. R.; Cairns, B. R.; Jones, D. A., Dnmt3 and G9a Cooperate for Tissue-specific Development in Zebrafish 2. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2010, 285, (6), 4110-4121. [CrossRef]

- Martins-Taylor, K.; Schroeder, D. I.; LaSalle, J. M.; Lalande, M.; Xu, R.-H., Role of DNMT3B in the regulation of early neural and neural crest specifiers. Epigenetics 2012, 7, (1), 71-82. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacques-Fricke, B. T.; Roffers-Agarwal, J.; Gammill, L. S., DNA methyltransferase 3b is dispensable for mouse neural crest development. 2012.

- Nowialis, P.; Lopusna, K.; Opavska, J.; Haney, S. L.; Abraham, A.; Sheng, P.; Riva, A.; Natarajan, A.; Guryanova, O.; Simpson, M., Catalytically inactive Dnmt3b rescues mouse embryonic development by accessory and repressive functions. Nature communications 2019, 10, (1), 4374. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seelan, R. S.; Appana, S. N.; Mukhopadhyay, P.; Warner, D. R.; Brock, G. N.; Pisano, M. M.; Greene, R. M., Developmental profiles of the murine palatal methylome. Birth Defects Research Part A: Clinical and Molecular Teratology 2013, 97, (4), 171-186.

- Juriloff, D. M.; Harris, M. J.; Mager, D. L.; Gagnier, L., Epigenetic mechanism causes Wnt9b deficiency and nonsyndromic cleft lip and palate in the A/WySn mouse strain. Birth Defects Research Part A: Clinical and Molecular Teratology 2014, 100, (10), 772-788.

- Alvizi, L.; Ke, X.; Brito, L. A.; Seselgyte, R.; Moore, G. E.; Stanier, P.; Passos-Bueno, M. R., Differential methylation is associated with non-syndromic cleft lip and palate and contributes to penetrance effects. Scientific reports 2017, 7, (1), 2441. [CrossRef]

- Cáceres-Rojas, G.; Salamanca, C.; Krause, B. J.; Recabarren, A. S.; Recabarren, P. A.; Pantoja, R.; Leiva, N.; Pardo, R.; Santos, J. L.; Suazo, J., Nonsyndromic orofacial clefts in Chile: LINE-1 methylation and MTHFR variants. Epigenomics 2020, 12, (20), 1783-1791. [CrossRef]

- Joubert, B. R.; Felix, J. F.; Yousefi, P.; Bakulski, K. M.; Just, A. C.; Breton, C.; Reese, S. E.; Markunas, C. A.; Richmond, R. C.; Xu, C.-J., DNA methylation in newborns and maternal smoking in pregnancy: genome-wide consortium meta-analysis. The American Journal of Human Genetics 2016, 98, (4), 680-696. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinheiro, I.; Margueron, R.; Shukeir, N.; Eisold, M.; Fritzsch, C.; Richter, F. M.; Mittler, G.; Genoud, C.; Goyama, S.; Kurokawa, M., Prdm3 and Prdm16 are H3K9me1 methyltransferases required for mammalian heterochromatin integrity. Cell 2012, 150, (5), 948-960. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, N.; Strobl-Mazzulla, P. H.; Bronner, M. E., Epigenetic regulation in neural crest development. Developmental biology 2014, 396, (2), 159-168. [CrossRef]

- Arboleda, V. A.; Lee, H.; Dorrani, N.; Zadeh, N.; Willis, M.; Macmurdo, C. F.; Manning, M. A.; Kwan, A.; Hudgins, L.; Barthelemy, F., De novo nonsense mutations in KAT6A, a lysine acetyl-transferase gene, cause a syndrome including microcephaly and global developmental delay. The American Journal of Human Genetics 2015, 96, (3), 498-506. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milstone, Z. J.; Lawson, G.; Trivedi, C. M., Histone deacetylase 1 and 2 are essential for murine neural crest proliferation, pharyngeal arch development, and craniofacial morphogenesis. Developmental Dynamics 2017, 246, (12), 1015-1026. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rada-Iglesias, A.; Bajpai, R.; Prescott, S.; Brugmann, S. A.; Swigut, T.; Wysocka, J., Epigenomic annotation of enhancers predicts transcriptional regulators of human neural crest. Cell stem cell 2012, 11, (5), 633-648. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuiping, L.; Xingang, Y.; Yuexian, F.; Lin, Q.; Xiaofei, T.; Yan, L.; Guanghui, W., The role of histone H3 acetylation on cleft palate in mice induced by 2, 3, 7, 8-tetrachlorodibenzopdioxin. Zhonghua Zheng Xing wai ke za zhi= Zhonghua Zhengxing Waike Zazhi= Chinese Journal of Plastic Surgery 2014, 30, (5), 369-372.

- Lindgren, A. M.; Hoyos, T.; Talkowski, M. E.; Hanscom, C.; Blumenthal, I.; Chiang, C.; Ernst, C.; Pereira, S.; Ordulu, Z.; Clericuzio, C., Haploinsufficiency of KDM6A is associated with severe psychomotor retardation, global growth restriction, seizures and cleft palate. Human genetics 2013, 132, 537-552. [CrossRef]

- Van Laarhoven, P. M.; Neitzel, L. R.; Quintana, A. M.; Geiger, E. A.; Zackai, E. H.; Clouthier, D. E.; Artinger, K. B.; Ming, J. E.; Shaikh, T. H., Kabuki syndrome genes KMT2D and KDM6A: functional analyses demonstrate critical roles in craniofacial, heart and brain development. Human molecular genetics 2015, 24, (15), 4443-4453. [CrossRef]

- Shpargel, K. B.; Starmer, J.; Wang, C.; Ge, K.; Magnuson, T., UTX-guided neural crest function underlies craniofacial features of Kabuki syndrome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2017, 114, (43), E9046-E9055. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, T.; Han, X.; He, J.; Feng, J.; Jing, J.; Janečková, E.; Lei, J.; Ho, T. V.; Xu, J.; Chai, Y., KDM6B interacts with TFDP1 to activate P53 signaling in regulating mouse palatogenesis. Elife 2022, 11. [CrossRef]

- Schwenty-Lara, J.; Nehl, D.; Borchers, A., The histone methyltransferase KMT2D, mutated in Kabuki syndrome patients, is required for neural crest cell formation and migration. Human Molecular Genetics 2020, 29, (2), 305-319. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. M.; Jung, H.; de Paula Machado Pasqua, B.; Park, Y.; Jeon, S.; Lee, S. K.; Lee, J. W.; Kwon, H. E., Mll4 regulates postnatal palate growth and midpalatal suture development. bioRxiv 2024. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bögershausen, N.; Tsai, I.-C.; Pohl, E.; Kiper, P. Ö. S.; Beleggia, F.; Percin, E. F.; Keupp, K.; Matchan, A.; Milz, E.; Alanay, Y., RAP1-mediated MEK/ERK pathway defects in Kabuki syndrome. The Journal of clinical investigation 2015, 125, (9), 3585-3599. [CrossRef]

- Tsai, I.-C.; McKnight, K.; McKinstry, S. U.; Maynard, A. T.; Tan, P. L.; Golzio, C.; White, C. T.; Price, D. J.; Davis, E. E.; Amrine-Madsen, H., Small molecule inhibition of RAS/MAPK signaling ameliorates developmental pathologies of Kabuki Syndrome. Scientific reports 2018, 8, (1), 10779. [CrossRef]

- Fortschegger, K.; de Graaf, P.; Outchkourov, N. S.; van Schaik, F. M.; Timmers, H. M.; Shiekhattar, R., PHF8 targets histone methylation and RNA polymerase II to activate transcription. Molecular and cellular biology 2010. [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Yonezawa, M.; Ye, J.; Jenuwein, T.; Grummt, I., PHF8 activates transcription of rRNA genes through H3K4me3 binding and H3K9me1/2 demethylation. Nature structural & molecular biology 2010, 17, (4), 445-450.

- Qi, H. H.; Sarkissian, M.; Hu, G.-Q.; Wang, Z.; Bhattacharjee, A.; Gordon, D. B.; Gonzales, M.; Lan, F.; Ongusaha, P. P.; Huarte, M., Histone H4K20/H3K9 demethylase PHF8 regulates zebrafish brain and craniofacial development. Nature 2010, 466, (7305), 503-507. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loenarz, C.; Ge, W.; Coleman, M. L.; Rose, N. R.; Cooper, C. D.; Klose, R. J.; Ratcliffe, P. J.; Schofield, C. J., PHF8, a gene associated with cleft lip/palate and mental retardation, encodes for an N ε-dimethyl lysine demethylase. Human molecular genetics 2010, 19, (2), 217-222. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Q.; Yang, P.; Wu, Y.; Meng, S.; Sui, L.; Zhang, L.; Yu, L.; Tang, Y.; Jiang, H.; Xuan, D., Epigenetically modified bone marrow stromal cells in silk scaffolds promote craniofacial bone repair and wound healing. Tissue engineering Part A 2015, 21, (15-16), 2156-2165.

- Ding, H. L.; Clouthier, D. E.; Artinger, K. B., Redundant roles of PRDM family members in zebrafish craniofacial development. Developmental Dynamics 2013, 242, (1), 67-79. [CrossRef]

- Shull, L. C.; Sen, R.; Menzel, J.; Goyama, S.; Kurokawa, M.; Artinger, K. B., The conserved and divergent roles of Prdm3 and Prdm16 in zebrafish and mouse craniofacial development. Developmental biology 2020, 461, (2), 132-144. [CrossRef]

- Strassman, A.; Schnütgen, F.; Dai, Q.; Jones, J. C.; Gomez, A. C.; Pitstick, L.; Holton, N. E.; Moskal, R.; Leslie, E. R.; von Melchner, H., Generation of a multipurpose Prdm16 mouse allele by targeted gene trapping. Disease models & mechanisms 2017, 10, (7), 909-922.

- Warner, D. R.; Mukhopadhyay, P.; Webb, C. L.; Greene, R. M.; Pisano, M. M., Chromatin immunoprecipitation-promoter microarray identification of genes regulated by PRDM16 in murine embryonic palate mesenchymal cells. Experimental Biology and Medicine 2012, 237, (4), 387-394. [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Wang, A. H.; Oses-Prieto, J.; Makhijani, K.; Katsuno, Y.; Pei, M.; Yan, L.; Zheng, Y. G.; Burlingame, A.; Brückner, K., Arginine methylation initiates BMP-induced Smad signaling. Molecular cell 2013, 51, (1), 5-19. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gou, Y.; Li, J.; Wu, J.; Gupta, R.; Cho, I.; Ho, T. V.; Chai, Y.; Merrill, A.; Wang, J.; Xu, J., Prmt1 regulates craniofacial bone formation upstream of Msx1. Mech Dev 2018, 152, 13-20. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gou, Y.; Li, J.; Jackson-Weaver, O.; Wu, J.; Zhang, T.; Gupta, R.; Cho, I.; Ho, T. V.; Chen, Y.; Li, M.; Richard, S.; Wang, J.; Chai, Y.; Xu, J., Protein Arginine Methyltransferase PRMT1 Is Essential for Palatogenesis. J Dent Res 2018, 97, (13), 1510-1518. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Higashihori, N.; Yahiro, K.; Moriyama, K., Retinoic acid inhibits histone methyltransferase Whsc1 during palatogenesis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2015, 458, (3), 525-530. [CrossRef]

- Mills, A.; Bearce, E.; Cella, R.; Kim, S. W.; Selig, M.; Lee, S.; Lowery, L. A., Wolf-Hirschhorn Syndrome-Associated Genes Are Enriched in Motile Neural Crest Cells and Affect Craniofacial Development in Xenopus laevis. Front Physiol 2019, 10, 431. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, N.; Gupta, M.; Trivedi, C. M.; Singh, M. K.; Li, L.; Epstein, J. A., Murine craniofacial development requires Hdac3-mediated repression of Msx gene expression. Dev Biol 2013, 377, (2), 333-44. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeLaurier, A.; Nakamura, Y.; Braasch, I.; Khanna, V.; Kato, H.; Wakitani, S.; Postlethwait, J. H.; Kimmel, C. B., Histone deacetylase-4 is required during early cranial neural crest development for generation of the zebrafish palatal skeleton. BMC Dev Biol 2012, 12, 16. [CrossRef]

- Voss, A. K.; Vanyai, H. K.; Collin, C.; Dixon, M. P.; McLennan, T. J.; Sheikh, B. N.; Scambler, P.; Thomas, T., MOZ regulates the Tbx1 locus, and Moz mutation partially phenocopies DiGeorge syndrome. Dev Cell 2012, 23, (3), 652-63. [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay, P.; Brock, G.; Pihur, V.; Webb, C.; Pisano, M. M.; Greene, R. M., Developmental microRNA expression profiling of murine embryonic orofacial tissue. Birth Defects Research Part A: Clinical and Molecular Teratology 2010, 88, (7), 511-534.

- Nie, X.; Wang, Q.; Jiao, K., Dicer activity in neural crest cells is essential for craniofacial organogenesis and pharyngeal arch artery morphogenesis. Mechanisms of development 2011, 128, (3-4), 200-207.

- Huang, Z.-P.; Chen, J.-F.; Regan, J. N.; Maguire, C. T.; Tang, R.-H.; Dong, X. R.; Majesky, M. W.; Wang, D.-Z., Loss of microRNAs in neural crest leads to cardiovascular syndromes resembling human congenital heart defects. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology 2010, 30, (12), 2575-2586.

- Sheehy, N. T.; Cordes, K. R.; White, M. P.; Ivey, K. N.; Srivastava, D., The neural crest-enriched microRNA miR-452 regulates epithelial-mesenchymal signaling in the first pharyngeal arch. Development 2010, 137, (24), 4307-4316. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stüssel, L. G.; Hollstein, R.; Laugsch, M.; Hochfeld, L. M.; Welzenbach, J.; Schröder, J.; Thieme, F.; Ishorst, N.; Romero, R. O.; Weinhold, L.; Hess, T.; Gehlen, J.; Mostowska, A.; Heilmann-Heimbach, S.; Mangold, E.; Rada-Iglesias, A.; Knapp, M.; Schaaf, C. P.; Ludwig, K. U., MiRNA-149 as a Candidate for Facial Clefting and Neural Crest Cell Migration. Journal of Dental Research 2022, 101, (3), 323-330. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, A.; Li, A.; Gajera, M.; Abdallah, N.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, Z.; Iwata, J., MicroRNA-374a,-4680, and-133b suppress cell proliferation through the regulation of genes associated with human cleft palate in cultured human palate cells. BMC medical genomics 2019, 12, 1-13. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, A.; Yoshioka, H.; Summakia, D.; Desai, N. G.; Jun, G.; Jia, P.; Loose, D. S.; Ogata, K.; Gajera, M. V.; Zhao, Z., MicroRNA-124-3p suppresses mouse lip mesenchymal cell proliferation through the regulation of genes associated with cleft lip in the mouse. Bmc Genomics 2019, 20, 1-17. [CrossRef]

- Gajera, M.; Desai, N.; Suzuki, A.; Li, A.; Zhang, M.; Jun, G.; Jia, P.; Zhao, Z.; Iwata, J., MicroRNA-655-3p and microRNA-497-5p inhibit cell proliferation in cultured human lip cells through the regulation of genes related to human cleft lip. BMC medical genomics 2019, 12, 1-18. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshioka, H.; Li, A.; Suzuki, A.; Ramakrishnan, S. S.; Zhao, Z.; Iwata, J., Identification of microRNAs and gene regulatory networks in cleft lip common in humans and mice. Human Molecular Genetics 2021, 30, (19), 1881-1893. [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Jia, P.; Mallik, S.; Fei, R.; Yoshioka, H.; Suzuki, A.; Iwata, J.; Zhao, Z., Critical microRNAs and regulatory motifs in cleft palate identified by a conserved miRNA–TF–gene network approach in humans and mice. Briefings in bioinformatics 2020, 21, (4), 1465-1478. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, C.; Lou, S.; Zhu, G.; Fan, L.; Yu, X.; Zhu, W.; Ma, L.; Wang, L.; Pan, Y., Identification of new miRNA-mRNA networks in the development of non-syndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate. Frontiers in cell and developmental biology 2021, 9, 631057. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Bai, Y.; Li, H.; Greene, S. B.; Klysik, E.; Yu, W.; Schwartz, R. J.; Williams, T. J.; Martin, J. F., MicroRNA-17-92, a Direct Ap-2α Transcriptional Target, Modulates T-Box Factor Activity in Orofacial Clefting. PLOS Genetics 2013, 9, (9), e1003785.

- Li, Y.-H.; Yang, J.; Zhang, J.-L.; Liu, J.-Q.; Zheng, Z.; Hu, D.-H., BMP4 rs17563 polymorphism and nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate: A meta-analysis. Medicine 2017, 96, (31), e7676. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.; Lewis, A. E.; Singh, V.; Ma, X.; Adelstein, R.; Bush, J. O., Convergence and extrusion are required for normal fusion of the mammalian secondary palate. PLoS biology 2015, 13, (4), e1002122. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukhopadhyay, P.; Smolenkova, I.; Seelan, R. S.; Pisano, M. M.; Greene, R. M., Spatiotemporal Expression and Functional Analysis of miRNA-22 in the Developing Secondary Palate. The Cleft Palate Craniofacial Journal 2023, 60, (1), 27-38. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpinelli, M. R.; De Vries, M. E.; Auden, A.; Butt, T.; Deng, Z.; Partridge, D. D.; Miles, L. B.; Georgy, S. R.; Haigh, J. J.; Darido, C., Inactivation of Zeb1 in GRHL2-deficient mouse embryos rescues mid-gestation viability and secondary palate closure. Disease models & mechanisms 2020, 13, (3), dmm042218.

- Shin, J.-O.; Lee, J.-M.; Cho, K.-W.; Kwak, S.; Kwon, H.-J.; Lee, M.-J.; Cho, S.-W.; Kim, K.-S.; Jung, H.-S., MiR-200b is involved in Tgf-β signaling to regulate mammalian palate development. Histochemistry and Cell Biology 2012, 137, (1), 67-78. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukhopadhyay, P.; Smolenkova, I.; Warner, D.; Pisano, M. M.; Greene, R. M., Spatio-temporal expression and functional analysis of miR-206 in developing orofacial tissue. MicroRNA 2019, 8, (1), 43-60. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Meng, T.; Jia, Z.; Zhu, G.; Shi, B., Single nucleotide polymorphism associated with nonsyndromic cleft palate influences the processing of miR-140. Am J Med Genet A 2010, 152a, (4), 856-62. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cesana, M.; Cacchiarelli, D.; Legnini, I.; Santini, T.; Sthandier, O.; Chinappi, M.; Tramontano, A.; Bozzoni, I., A long noncoding RNA controls muscle differentiation by functioning as a competing endogenous RNA. Cell 2011, 147, (2), 358-369. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, B.; Wang, S.; Wu, W.; Shan, P.; Chen, Y.; Meng, J.; Xing, L.; Yun, J.; Hao, L.; Wang, X.; Li, S.; Guo, Y., Mechanisms of circRNA/lncRNA-miRNA interactions and applications in disease and drug research. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2023, 162, 114672.

- Wu, C.; Liu, H.; Zhan, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, M.; You, J.; Ma, J., Unveiling dysregulated lncRNAs and networks in non-syndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate pathogenesis. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, (1), 1047. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geisler, S.; Coller, J., RNA in unexpected places: long non-coding RNA functions in diverse cellular contexts. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology 2013, 14, (11), 699-712. [CrossRef]

- Yun, L.; Ma, L.; Wang, M.; Yang, F.; Kan, S.; Zhang, C.; Xu, M.; Li, D.; Du, Y.; Zhang, W., Rs2262251 in lncRNA RP11-462G12. 2 is associated with nonsyndromic cleft lip with/without cleft palate. Human Mutation 2019, 40, (11), 2057-2067.

- Shu, X.; Dong, Z.; Zhang, M.; Shu, S., Integrated analysis identifying long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) for competing endogenous RNAs (ceRNAs) network-regulated palatal shelf fusion in the development of mouse cleft palate. Annals of translational medicine 2019, 7, (23).

- Ito, Y.; Yeo, J. Y.; Chytil, A.; Han, J.; Bringas, P., Jr; Nakajima, A.; Shuler, C. F.; Moses, H. L.; Chai, Y., Conditional inactivation of Tgfbr2 in cranial neural crest causes cleft palate and calvaria defects. Development 2003, 130, (21), 5269-5280. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zang, Q.; Song, H.; Fu, S.; Sun, W.; Zhang, W.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Jiao, X., Comprehensive analysis of differentially expressed profiles of non-coding RNAs in peripheral blood and ceRNA regulatory networks in non-syndromic orofacial clefts. Molecular medicine reports 2019, 20, (1), 513-528. [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.; Guo, Y.; Gao, S.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, B.; Dissanayaka, W. L.; Zheng, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Zhai, J.; Gao, Z., Long non-coding RNAs MALAT1 and NEAT1 in non-syndromic orofacial clefts. Oral Diseases 2023, 29, (4), 1668-1679. [CrossRef]

- Piunti, A.; Shilatifard, A., Author Correction: The roles of Polycomb repressive complexes in mammalian development and cancer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2022, 23, (6), 444. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Langohr, I. M.; Faisal, M.; McNulty, M.; Thorn, C.; Kim, J., Ablation of Ezh2 in neural crest cells leads to aberrant enteric nervous system development in mice. PLoS One 2018, 13, (8), e0203391. [CrossRef]

- Lui, J. C.; Barnes, K. M.; Dong, L.; Yue, S.; Graber, E.; Rapaport, R.; Dauber, A.; Nilsson, O.; Baron, J., Ezh2 Mutations Found in the Weaver Overgrowth Syndrome Cause a Partial Loss of H3K27 Histone Methyltransferase Activity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2018, 103, (4), 1470-1478. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Velden, Y. U.; Wang, L.; Querol Cano, L.; Haramis, A.-P. G., The polycomb group protein ring1b/rnf2 is specifically required for craniofacial development. PloS one 2013, 8, (9), e73997. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marc, S.; Mizeranschi, A. E.; Paul, C.; Otavă, G.; Savici, J.; Sicoe, B.; Torda, I.; Huțu, I.; Mircu, C.; Ilie, D. E., Simultaneous occurrence of hypospadias and bilateral cleft lip and jaw in a crossbred calf: Clinical, computer tomographic, and genomic characterization. Animals 2023, 13, (10), 1709. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lichtig, H.; Artamonov, A.; Polevoy, H.; Reid, C. D.; Bielas, S. L.; Frank, D., Modeling Bainbridge-Ropers syndrome in Xenopus laevis embryos. Frontiers in physiology 2020, 11, 75. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagliaroli, L.; Porazzi, P.; Curtis, A. T.; Scopa, C.; Mikkers, H. M.; Freund, C.; Daxinger, L.; Deliard, S.; Welsh, S. A.; Offley, S., Inability to switch from ARID1A-BAF to ARID1B-BAF impairs exit from pluripotency and commitment towards neural crest formation in ARID1B-related neurodevelopmental disorders. Nature communications 2021, 12, (1), 6469. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyake, N.; Tsurusaki, Y.; Matsumoto, N. In Numerous BAF complex genes are mutated in Coffin–Siris syndrome, American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C: Seminars in Medical Genetics, 2014; Wiley Online Library: 2014; pp 257-261.

- Bi-Lin, K. W.; Seshachalam, P. V.; Tuoc, T.; Stoykova, A.; Ghosh, S.; Singh, M. K., Critical role of the BAF chromatin remodeling complex during murine neural crest development. PLoS genetics 2021, 17, (3), e1009446. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diets, I. J.; Prescott, T.; Champaigne, N. L.; Mancini, G. M.; Krossnes, B.; Frič, R.; Kocsis, K.; Jongmans, M. C.; Kleefstra, T., A recurrent de novo missense pathogenic variant in SMARCB1 causes severe intellectual disability and choroid plexus hyperplasia with resultant hydrocephalus. Genetics in Medicine 2019, 21, (3), 572-579. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Chen, Q.; Luo, W.; Pakvasa, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, L.; Li, S.; Yang, Z.; Zeng, H.; Liang, F., SATB2: A versatile transcriptional regulator of craniofacial and skeleton development, neurogenesis and tumorigenesis, and its applications in regenerative medicine. Genes & Diseases 2022, 9, (1), 95-107.

- Garland, M. A.; Reynolds, K.; Zhou, C. J., Environmental mechanisms of orofacial clefts. Birth Defects Research 2020, 112, (19), 1660-1698. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiani, A.; Sharafi, K.; Omer, A. K.; Kiani, A.; Matin, B. K.; Heydari, M. B.; Massahi, T., A Systematic Literature Review on the Association Between Toxic and Essential Trace Elements and the Risk of Orofacial Clefts in Infants. Biol Trace Elem Res 2024, 202, (8), 3504-3516. [CrossRef]

- Heydari, M.-H.; Sadeghian, A.; Khadivi, G.; Mustafa, H. J.; Javinani, A.; Nadjmi, N.; Khojasteh, A., Prevalence, trend, and associated risk factors for cleft lip with/without cleft palate: a national study on live births from 2016 to 2021. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, (1), 36. [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, T. J.; Duester, G., Mechanisms of retinoic acid signalling and its roles in organ and limb development. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2015, 16, (2), 110-23. [CrossRef]

- Kawaguchi, R.; Yu, J.; Honda, J.; Hu, J.; Whitelegge, J.; Ping, P.; Wiita, P.; Bok, D.; Sun, H., A membrane receptor for retinol binding protein mediates cellular uptake of vitamin A. Science 2007, 315, (5813), 820-825. [CrossRef]

- Niederreither, K.; Dollé, P., Retinoic acid in development: towards an integrated view. Nature Reviews Genetics 2008, 9, (7), 541-553. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dupé, V.; Matt, N.; Garnier, J.-M.; Chambon, P.; Mark, M.; Ghyselinck, N. B., A newborn lethal defect due to inactivation of retinaldehyde dehydrogenase type 3 is prevented by maternal retinoic acid treatment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2003, 100, (24), 14036-14041. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Funato, N.; Nakamura, M.; Richardson, J. A.; Srivastava, D.; Yanagisawa, H., Tbx1 regulates oral epithelial adhesion and palatal development. Hum Mol Genet 2012, 21, (11), 2524-37. [CrossRef]

- Roberts, C.; Ivins, S.; Cook, A. C.; Baldini, A.; Scambler, P. J., Cyp26 genes a1, b1 and c1 are down-regulated in Tbx1 null mice and inhibition of Cyp26 enzyme function produces a phenocopy of DiGeorge Syndrome in the chick. Human molecular genetics 2006, 15, (23), 3394-3410. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okano, J.; Kimura, W.; Papaionnou, V. E.; Miura, N.; Yamada, G.; Shiota, K.; Sakai, Y., The regulation of endogenous retinoic acid level through CYP26B1 is required for elevation of palatal shelves. Developmental Dynamics 2012, 241, (11), 1744-1756. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, H.; Gao, L.; Yin, Y.; Pan, X.; Li, Z.; Li, N.; Li, H.; Yu, Z., Negative Interplay of Retinoic Acid and TGF-β Signaling Mediated by TG-Interacting Factor to Modulate Mouse Embryonic Palate Mesenchymal–Cell Proliferation. Birth Defects Research Part B: Developmental and Reproductive Toxicology 2014, 101, (6), 403-409.

- Zhang, Y.; Dong, S.; Wang, J.; Wang, M.; Chen, M.; Huang, H., Involvement of Notch2 in all-trans retinoic acid-induced inhibition of mouse embryonic palate mesenchymal cell proliferation. Molecular Medicine Reports 2017, 16, (3), 2538-2546. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimomura, T.; Kawakami, M.; Okuda, H.; Tatsumi, K.; Morita, S.; Nochioka, K.; Kirita, T.; Wanaka, A., Retinoic acid regulates Lhx8 expression via FGF-8b to the upper jaw development of chick embryo. Journal of bioscience and bioengineering 2015, 119, (3), 260-266. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Xiao, Q.; Xiao, J.; Niu, C.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, Z.; Shu, G.; Yin, G., Wnt/β-catenin signalling: function, biological mechanisms, and therapeutic opportunities. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2022, 7, (1), 3. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Dong, S.; Wang, W.; Wang, J.; Wang, M.; Chen, M.; Hou, J.; Huang, H., Activation of Notch1 inhibits medial edge epithelium apoptosis in all-trans retinoic acid-induced cleft palate in mice. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 2016, 477, (3), 322-328. [CrossRef]

- Shu, X.; Dong, Z.; Shu, S., AMBRA1-mediated autophagy and apoptosis associated with an epithelial-mesenchymal transition in the development of cleft palate induced by all-trans retinoic acid. Annals of translational medicine 2019, 7, (7).

- Zhang, W.; Shen, Z.; Xing, Y.; Zhao, H.; Liang, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhong, X.; Shi, L.; Wan, X.; Zhou, J., MiR-106a-5p modulates apoptosis and metabonomics changes by TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway in cleft palate. Experimental cell research 2020, 386, (2), 111734. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhou, J.; Ji, Y.; Shu, S.; Zhang, M.; Liang, Y., LncRNA-NONMMUT100923.1 regulates mouse embryonic palatal shelf adhesion by sponging miR-200a-3p to modulate medial epithelial cell desmosome junction during palatogenesis. Heliyon 2023, 9, (5), e16329.

- Zhou, J.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, M.; Tan, M.; Ji, Y.; Shu, S.; Liang, Y., MiRNA-470-5p suppresses epithelial-mesenchymal transition of embryonic palatal shelf epithelial cells by targeting Fgfr1 during palatogenesis. Experimental Biology and Medicine 2023, 248, (13), 1124-1133. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, E. J.; Chung, G. E.; Yoo, J. J.; Cho, Y.; Shin, D. W.; Kim, Y. J.; Yoon, J. H.; Han, K.; Yu, S. J., The association between alcohol consumption and the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma according to glycemic status in Korea: A nationwide population-based study. PLoS Med 2023, 20, (6), e1004244. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maranhão, S. C.; Sá, J.; Cangussú, M. C. T.; Coletta, R. D.; Reis, S. R.; Medrado, A. R., Nonsyndromic oral clefts and associated risk factors in the state of Bahia, Brazil. European Archives of Paediatric Dentistry 2021, 22, 121-127. [CrossRef]

- Deitrich, R.; Zimatkin, S.; Pronko, S., Oxidation of ethanol in the brain and its consequences. Alcohol Res Health 2006, 29, (4), 266-73.

- Shabtai, Y.; Bendelac, L.; Jubran, H.; Hirschberg, J.; Fainsod, A., Acetaldehyde inhibits retinoic acid biosynthesis to mediate alcohol teratogenicity. Sci Rep 2018, 8, (1), 347. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarthy, N.; Wetherill, L.; Lovely, C. B.; Swartz, M. E.; Foroud, T. M.; Eberhart, J. K., Pdgfra protects against ethanol-induced craniofacial defects in a zebrafish model of FASD. Development 2013, 140, (15), 3254-3265. [CrossRef]

- Hicks, S. D.; Middleton, F. A.; Miller, M. W., Ethanol-induced methylation of cell cycle genes in neural stem cells. Journal of neurochemistry 2010, 114, (6), 1767-1780. [CrossRef]

- Jin, M.; Ande, A.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, S., Regulation of cytochrome P450 2e1 expression by ethanol: role of oxidative stress-mediated pkc/jnk/sp1 pathway. Cell death & disease 2013, 4, (3), e554-e554.

- Serio, R. N.; Laursen, K. B.; Urvalek, A. M.; Gross, S. S.; Gudas, L. J., Ethanol promotes differentiation of embryonic stem cells through retinoic acid receptor-γ. J Biol Chem 2019, 294, (14), 5536-5548. [CrossRef]

- Serio, R. N.; Gudas, L. J., Modification of stem cell states by alcohol and acetaldehyde. Chem Biol Interact 2020, 316, 108919. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahn, M. E.; Karchner, S. I.; Merson, R. R., Diversity as opportunity: insights from 600 million years of AHR evolution. Current opinion in toxicology 2017, 2, 58-71. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujiwara, K.; Yamada, T.; Mishima, K.; Imura, H.; Sugahara, T., Morphological and immunohistochemical studies on cleft palates induced by 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin in mice. Congenit Anom (Kyoto) 2008, 48, (2), 68-73. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takagi, T. N.; Matsui, K. A.; Yamashita, K.; Ohmori, H.; Yasuda, M., Pathogenesis of cleft palate in mouse embryos exposed to 2, 3, 7, 8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD). Teratogenesis, carcinogenesis, and mutagenesis 2000, 20, (2), 73-86.

- Yuan, X.; Qiu, L.; Pu, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhang, X.; Wang, C.; Pu, W.; Fu, Y., Histone acetylation is involved in TCDD-induced cleft palate formation in fetal mice. Molecular medicine reports 2016, 14, (2), 1139-1145. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Li, X.; Tao, Y.; Li, N.; Ji, M.; Zhang, X.; Chen, Y.; He, Z.; Yu, K.; Yu, Z., TCDD inhibited the osteogenic differentiation of human fetal palatal mesenchymal cells through AhR and BMP-2/TGF-β/Smad signaling. Toxicology 2020, 431, 152353. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Z.; Bu, Y.; Zhang, G.; Liu, X.; Wang, X.; Ding, S.; Wang, E.; Shi, R.; Li, Q.; Fu, J., Effect of TCDD on the fate of epithelial cells isolated from human fetal palatal shelves (hFPECs). Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology 2016, 305, 186-193. [CrossRef]

- Thomae, T. L.; Stevens, E. A.; Bradfield, C. A., Transforming growth factor-β3 restores fusion in palatal shelves exposed to 2, 3, 7, 8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2005, 280, (13), 12742-12746. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, G.; Song, S.; Su, H.; Duan, W.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X., Identification of competing endogenous RNA networks associated with circRNA and lncRNA in TCDD-induced cleft palate development. Toxicol Lett 2024, 401, 71-81. [CrossRef]

- Yoshioka, H.; Jun, G.; Suzuki, A.; Iwata, J., Dexamethasone Suppresses Palatal Cell Proliferation through miR-130a-3p. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, (22).

- Yang, W.; Carmichael, S. L.; Shaw, G. M., Folic acid fortification and prevalences of neural tube defects, orofacial clefts, and gastroschisis in California, 1989 to 2010. Birth Defects Research Part A: Clinical and Molecular Teratology 2016, 106, (12), 1032-1041.

- Jahanbin, A.; Shadkam, E.; Miri, H. H.; Shirazi, A. S.; Abtahi, M., Maternal folic acid supplementation and the risk of oral clefts in offspring. Journal of Craniofacial Surgery 2018, 29, (6), e534-e541. [CrossRef]

- Salamanca, C.; González-Hormazábal, P.; Recabarren, A. S.; Recabarren, P. A.; Pantoja, R.; Leiva, N.; Pardo, R.; Suazo, J., A SHMT1 variant decreases the risk of nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate in Chile. Oral Diseases 2020, 26, (1), 159-165. [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Chau, C.; Blanco, R.; Colombo, A.; Pardo, R.; Suazo, J., MTHFR c. 677C> T is a risk factor for non-syndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate in Chile. Oral Diseases 2016, 22, (7), 703-708. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padmanabhan, N.; Jia, D.; Geary-Joo, C.; Wu, X.; Ferguson-Smith, A. C.; Fung, E.; Bieda, M. C.; Snyder, F. F.; Gravel, R. A.; Cross, J. C., Mutation in folate metabolism causes epigenetic instability and transgenerational effects on development. Cell 2013, 155, (1), 81-93. [CrossRef]

- Wahl, S. E.; Kennedy, A. E.; Wyatt, B. H.; Moore, A. D.; Pridgen, D. E.; Cherry, A. M.; Mavila, C. B.; Dickinson, A. J., The role of folate metabolism in orofacial development and clefting. Developmental biology 2015, 405, (1), 108-122. [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, N.; Sedoris, K. C.; Steed, M.; Ovechkin, A. V.; Moshal, K. S.; Tyagi, S. C., Mechanisms of homocysteine-induced oxidative stress. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology 2005, 289, (6), H2649-H2656.

- Ritchie, H. E.; Oakes, D.; Farrell, E.; Ababneh, D.; Howe, A., Fetal hypoxia and hyperglycemia in the formation of phenytoin-induced cleft lip and maxillary hypoplasia. Epilepsia Open 2019, 4, (3), 443-451. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Little, J.; Cardy, A.; Munger, R. G., Tobacco smoking and oral clefts: a meta-analysis. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 2004, 82, (3), 213-218.

- Honein, M. A.; Devine, O.; Grosse, S. D.; Reefhuis, J., Prevention of orofacial clefts caused by smoking: implications of the Surgeon General's report. Birth Defects Research Part A: Clinical and Molecular Teratology 2014, 100, (11), 822-825.

- Lammer, E. J.; Shaw, G. M.; Iovannisci, D. M.; Van Waes, J.; Finnell, R. H., Maternal smoking and the risk of orofacial clefts: Susceptibility with NAT1 and NAT2 polymorphisms. Epidemiology 2004, 15, (2), 150-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Junaid, M.; Narayanan, M. A.; Jayanthi, D.; Kumar, S. R.; Selvamary, A. L., Association between maternal exposure to tobacco, presence of TGFA gene, and the occurrence of oral clefts. A case control study. Clinical Oral Investigations 2018, 22, 217-223. [CrossRef]

- Ebadifar, A.; Hamedi, R.; KhorramKhorshid, H. R.; Kamali, K.; Moghadam, F. A., Parental cigarette smoking, transforming growth factor-alpha gene variant and the risk of orofacial cleft in Iranian infants. Iran J Basic Med Sci 2016, 19, (4), 366-73.

- Lin, J.-y.; Luan, R.-s.; Guo, Z.-q.; Lin, X.-q.; Tang, H.-y.; Chen, Y.-p., [The correlation analysis between environmental factors, bone morphogenetic protein-4 and transforming growth factor beta-3 polymorphisms in nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate]. Zhonghua Kou Qiang Yi Xue Za Zhi 2010, 45, (10), 596-600.

- Izzotti, A.; Balansky, R. M.; Cartiglia, C.; Camoirano, A.; Longobardi, M.; De Flora, S., Genomic and transcriptional alterations in mouse fetus liver after transplacental exposure to cigarette smoke. The FASEB journal 2003, 17, (9), 1127-1129. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukhopadhyay, P.; Greene, R. M.; Pisano, M. M., Cigarette smoke induces proteasomal-mediated degradation of DNA methyltransferases and methyl CpG-/CpG domain-binding proteins in embryonic orofacial cells. Reproductive Toxicology 2015, 58, 140-148. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, D.; Huang, X.; Yang, S.; Zhang, L., Direct effects of nicotine on contractility of the uterine artery in pregnancy. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 2007, 322, (1), 180-185. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carroquino, M. J.; Posada, M.; Landrigan, P. J., Environmental Toxicology: Children at Risk. Environmental Toxicology. 2012 Dec 4:239-91. [CrossRef]

- Ni, W.; Yang, W.; Yu, J.; Li, Z.; Jin, L.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.; Ren, A., Umbilical cord concentrations of selected heavy metals and risk for orofacial clefts. Environmental science & technology 2018, 52, (18), 10787-10795.

| Feature | Description | Associated Genes/Regions/Pathways | Reference |

| Prevalence | ~70% of all clefts; ~1 in 700 live births globally | N/A | [70] |

| Subtypes | 45% cleft palate alone; 85% nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without palate |

N/A | [105] |

| Genetic Factors | SNPs, single gene mutations, microRNA patterns | WNT pathway (AXIN1, WNT9B), Fgf10/Fgfr2/Shh pathway (FGFR1, FGF2), COL11A1, IRF6, EGF, MSX1, PTCH, TGFB1, ROR2, FOXE1, TGFB3, RARA, APOC2, BCL3, PVRL2 | [105], [182] |

| Chromosomal Regions | Linkage to >20 regions | chr 1p, 1q21, 1q32-42.3, 6p, 2p, 4q, 17q | [105] |

| Epigenetic Factors | DNA methylation | EWAS studies identify differentially methylated regions | [102] |

| Rare Variants | Mutations in specific genes | ABCB1, ALKBH8, CENPF, CSAD, EXPH5, PDZD8, SLC16A9, TTC28 (ABCB1, TTC28, and PDZD8 show significant mutation constraint) | [183] |

| Syndrome |

Key Features (Including OFCs) |

Associated Genes /Chromosomal Regions |

Reference |

| DiGeorge Syndrome (DGS) | Cleft palate (most frequent), cardiac defects, immune deficiency, characteristic facial features | TBX1 (within the 22q11.2 deletion), miR-96-5p | [139], [184], [185] |

| Van der Woude Syndrome (VWS) | Cleft lip, cleft palate, hypodontia, paramedian lower lip pits | IRF6 (most common), GRHL3, CDH2 (SNP rs539075), NOL4 | [113], [139], [186] |

| Stickler Syndrome (STL) | Cleft palate/uvula, myopia, retinal detachment, joint problems, hearing loss | COL2A1 (STL1), COL11A1 (STL2), COL11A2 (STL3), COL9A1, COL9A2, COL9A3, LRP2, LOXL3 | [187], [188], [189] |

| Pierre-Robin Sequence (PRS) | Micrognathia, glossoptosis (posterior displacement of the tongue), cleft palate, airway obstruction | SOX9, BMPR1B, deletions on 2q and 4p, duplications on 3p, 3q, 7q, 8q, 10p, 14q, 16p, and 22q | [113], [190], [191], [192] |

| Kabuki Syndrome | Distinct facial features (midfacial hypoplasia, broad nasal tip, elongated palpebral fissures, large ears), cleft palate/high-arched palate, growth retardation, intellectual disability, congenital heart defects | KMT2D (most common), KDM6A |

[193], [194], [195] |

| Wolf-Hirschhorn Syndrome (WHS) | Intellectual disability, growth delays, heart and skeletal defects, seizures, cleft palate, facial asymmetry | WHSC1, WHSC2, LETM1, TACC3 | [113,196,197] |

| CHARGE Syndrome | Coloboma, Heart defects, Atresia of the choanae, Retarded growth/development, Genital abnormalities, Ear abnormalities/hearing loss, cleft palate | CHD7 | [113,178] |

| Apert Syndrome (AS) | Craniosynostosis, midface hypoplasia, cleft palate (more commonly soft palate), syndactyly of hands and feet | FGFR2 (p.Ser252Trp, p.Pro253Arg) |

[198,199,200,201,202,203] |

| Tatton-Brown-Rahman Syndrome (TBRS) | Overgrowth, macrocephaly, facial dysmorphism, intellectual disability, autism | DNMT3A | [204,205] |

| Arboleda-Tham Syndrome (ARTHS) | Intellectual disability, developmental/speech delays, hypotonia, congenital heart defects | KAT6A | [210,211,212,213] |

| Molecule Type | Specific Molecule | Target /Function | Effect on Orofacial Cleft Development | Reference |

| miRNA | miR-21, miR-181a | Sprouty2 (MAPK/ERK pathway) | cell proliferation, differentiation, and survival of neural crest cells | [177] |

| miR-452 | Wnt5a | EMT and neural crest cells patterning | [178], [139] | |

| miR-149 | hNCC migration | neural crest cells | [179] | |

| miR-133b, miR-374a-5p, miR-4680-3p | GCH1, PAX7, FGFR2, ERBB2 | cell proliferation | [15], [180] | |

| miR-497-5p | mTOR | cell proliferation | [181] | |

| miR-655-3p | TGF-β, Wnt | cell proliferation | [181] | |

| miR-124-3p | Bmpr1a, Cdc42, Tgfbr1 | proliferation in embryonic lip mesenchymal cells | [182], [183] | |

| miR-27b | PAX9, RARA | cell proliferation of lip mesenchymal cells | [185] | |

| miR-133b | FGFR1, PAX7, SUMO1 | cell proliferation of lip mesenchymal cells | [186], [8] | |

| miR-205 | PAX9, RARA | cell proliferation of lip mesenchymal cells | [189] | |

| hsa-let-7c-5p,hsa-miR-193a-3p | HEPM cells | cell proliferation | [190], [191], [15] | |

| miR-17, miR-18a, miR-19a, miR-19b-1, miR-20a, miR-92a-1 (mir-17-92 cluster) | Tbx1, Tbx3, Fgf10, TGFBR2, SMAD2, SMAD4 | midfacial development | [192], [15] | |

| miR-22-3p | Myh9, Myh10 | MES dissolution and palatal fusion | [193], [184] | |

| miR-200b | Smad2, Snail, Zeb1, Zeb2 (mediators of TGFβ signaling) | MES | [198],[15] | |

| miR-206 | TGFβ, Wnt/β-catenin | palatal fusion | [198], [15] | |

| miR-140 | SNP rs7205289, TGF-β | cell migration | [196] | |

| miR-744-5p | lncRNA RP11-462G12.2 (C-allele) | cell apoptosis, proliferation | [199] | |

| lncRNA | RP11-462G12.2(C-allele) | miR-744-5p, IQSEC2 | C-allele binds miR-744-5p | [202], [196] |

| NONMMUT100923.1 | miR-200a-3p | medial edge epithelial cell adhesion | [196], [195] | |

| NONMMUT004850.2/NONMMUT024276.2 | miR-741-3p,miR-465b-5p | palatal fusion | [199] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).