1. Introduction

Embodied Artificial Intelligence (AI) agents are transforming human-computer interactions by providing more natural, empathetic, and context-aware experiences [

1]. These agents integrate sensory inputs, contextual reasoning, natural language processing, and adaptive behaviors to interact with users in a human-like manner [

2,

3,

4]. Early research demonstrated how self-aware agents can learn complex behaviors in unstructured environments by actively seeking novel interactions [

5]. With advancements in Large Language Models (LLMs) [

6] such as GPT-4 developed by OpenAI [

7], and others like Claude by Anthropic and Google’s Gemini model, there is immense potential to enhance the capabilities of Embodied AI agents.

Our work is inspired by platforms like MineDojo and Voyager [

8,

9], which leverages internet-scale knowledge to build open-ended embodied agents within simulated environments like Minecraft. Genie introduces a new paradigm for generative AI, where interactive, playable environments can be generated from a single image prompt, enabling users to step into their imagined virtual worlds [

10]. Similarly, projects such as InterAct demonstrate the potential of cooperative AI agents using models like ChatGPT [

11]. However, while these platforms emphasize simulating physical reality and game environments, our approach shifts the focus towards creative expression, empowering creators to shape immersive and personalized experiences [

12].

Recent developments in AI hardware, such as NVIDIA’s powerful AI chips [

13,

14,

15], have opened new possibilities for deploying advanced and computationally intensive AI models in real-world applications, including robotics and interactive agents. NVIDIA’s Project GROOT, for instance, aims to bring the human-robot future closer by integrating sophisticated AI capabilities into embodied systems [

15,

16].

Despite these advancements, several challenges persist in developing Embodied AI agents that can:

Understand and Respond to User Emotions: Accurately detecting and interpreting nuanced emotional states from user inputs remains complex. Models like EmoRoBERTa have achieved state-of-the-art results in emotion classification [

17], but integrating these models into conversational agents for real-time interactions is non-trivial.

Recognize User Intents: Identifying underlying intents without extensive labeled datasets is critical for contextually appropriate responses. Zero-shot classification pipelines offer promising solutions [

18], and reinforcement learning-friendly vision-language models have been explored for game environments [

19,

20,

21]. Additionally, narrative-centered tutorial planning architectures recognize user intents in real-time, integrating story-driven inquiry with pedagogical control [

22].

Adapt Personalities Dynamically: Adjusting an agent’s personality traits in real time based on user interactions enhances engagement but poses computational and modeling challenges [

23]. Dynamic personality modeling requires integrating psychological frameworks like the OCEAN model into AI systems.

Facilitate Creative Expression: Moving beyond the simulation of real-world environments, there is a need to focus on creative domains where AI agents assist creators in content generation and personalization [

10,

12]. This involves enabling AI agents to participate in narrative development, character creation, and interactive storytelling [

22,

24].

Leverage Advanced Hardware for Scalability: The rise of powerful AI hardware [

13,

14,

15] allows for the deployment of more complex models but introduces challenges related to resource allocation and efficient computation, especially in real-time interactive systems.

1.1. Problem Definition

The core problem addressed in this work is the development of an Embodied AI agent that can:

Integrate Advanced LLMs: Leverage state-of-the-art language models like GPT-4 [

7] and others [

25] to enhance the agent’s natural language understanding [

26] and generation capabilities, facilitating more nuanced and contextually appropriate interactions.

Implement Emotion Analysis and Intent Recognition: Utilize advanced models to capture nuanced emotional states [

17] and accurately recognize user intents [

11,

18], enabling the agent to respond empathetically and align with conversational goals.

Enable Dynamic Personality Adaptation: Incorporate frameworks inspired by the OCEAN model to adapt the agent’s personality traits in real time [

23,

27], enhancing user engagement and fostering personalized experiences.

Focus on Creative Expression and Collaboration: Empower creators to develop AI-driven experiences that emphasize creativity and personal expression over mere simulation of the real world [

8,

10,

12], facilitating collaborative storytelling and content creation.

Utilize Advanced Hardware Innovations: Acknowledge and leverage the advancements in AI hardware [

13,

14,

15,

28] to deploy complex AI models efficiently, addressing scalability and performance concerns.

By addressing these components, we aim to advance the capabilities of Embodied AI agents, enabling them to deliver more empathetic, adaptive, and personalized interactions, particularly within creative domains such as interactive entertainment, virtual assistants, and educational tools.

1.2. Contributions

Our contributions are as follows:

1.2.1. Development of a Modular Embodied AI Agent

We design an agent capable of dynamically adapting its emotional and personality states based on user interactions, integrating emotion detection, intent recognition, and personality modeling into a cohesive system.

1.2.2. Integration of Advanced LLMs

We leverage GPT-4 and other cutting-edge LLMs to generate contextually appropriate and emotionally resonant responses, enhancing the naturalness and relevance of interactions.

1.2.3. Emphasis on Creative Collaboration

Inspired by platforms like Genie [

10], MineDojo [

8], and services like Inworld AI [

12], we focus on enabling creators to shape AI-driven experiences that prioritize creativity, personal expression, and collaborative engagement.

1.2.4. Harnessing Advanced Hardware

By considering the latest developments in AI hardware [

13,

14,

15], we discuss opportunities and strategies for deploying sophisticated AI models in practical, real-world applications.

1.2.5. Empirical Evaluation and Analysis

We conduct extensive experiments to assess the agent’s performance in emotion recognition accuracy, intent recognition coverage, and response quality, demonstrating significant improvements over baseline models.

2. Related Works

Embodied AI focuses on enabling agents to perceive, reason, and act within physical or virtual environments, offering a pathway toward more general intelligence [

29]. Recent efforts highlight the synergy between Multi-modal Large Models (MLMs) and World Models (WMs), as well as high-fidelity or generative environments for complex tasks. “Aligning Cyber Space with Physical World: A Comprehensive Survey on Embodied AI” [

29] presents a broad overview, covering topics like embodied perception, interaction, agent design, sim-to-real adaptation, and the roles of MLMs and WMs. “BEHAVIOR-1K: A Human-Centered, Embodied AI Benchmark with 1,000 Everyday Activities and Realistic Simulation” [

30] introduces a large-scale assessment platform of daily activities, showcasing OmniGibson’s detailed physics simulation for long-horizon, multi-step tasks relevant to real-world robotics. “GenEx: Generating an Explorable World” [

31] demonstrates how minimal visual input can be expanded into a 360-degree, GPT-assisted environment, enabling agents to predict and navigate unseen regions through generative imagination. Other efforts have shown that embodied agents have increasingly relied on Large Vision-Language Models to integrate advanced language reasoning with visual feedback [

32]. Collectively, these works illustrate complementary approaches—high-level surveys, human-centered benchmarks, and generative environment frameworks—that together push Embodied AI toward more robust sim-to-real transfer, deeper integration of multimodal data, andbibliography broader real-life applicability.

2.1. Embodied AI Agents and Interactive Environments

The development of Embodied AI agents that can interact within virtual environments has been a significant area of research, aiming to create agents that can perceive, reason, and act in simulated worlds [

2,

3,

33]. Platforms like Habitat provide high-performance simulators for training Embodied AI agents in photorealistic 3D environments, enabling research in navigation and interaction tasks [

3,

31]. While these platforms offer controlled settings for agent training, they often lack the open-endedness and creativity desired for more expansive applications.

MineDojo represents a step forward by leveraging the vast, open-ended environment of Minecraft to train embodied agents using internet-scale knowledge [

8]. MineDojo provides a rich playground for AI agents to engage in diverse tasks, learning from large datasets of online videos, wikis, and forums related to Minecraft gameplay. This approach enables the development of agents capable of performing complex tasks and adapting to new challenges within the game environment.

Our work differs from MineDojo by shifting the focus from learning within a predefined game environment to enabling creators to generate personalized and interactive virtual worlds from minimal inputs, such as a single image. By integrating advanced language models and dynamic personality adaptation, our agent facilitates not just interaction within an environment but also collaboration with users in the creation and personalization of that environment.

2.2. Generative Interactive Environments

For decades, players have explored interactive, modifiable environments via user-driven “modding” [

34]. Genie introduces a novel paradigm where interactive, playable environments can be generated from a single image prompt, allowing users to bring imagined virtual worlds to life [

10]. Genie learns to control environments without action labels by training on large datasets of internet videos, focusing on 2D platformer games and robotics. This approach enables the creation of endless varieties of playable worlds and demonstrates the potential of data-driven methods in generating interactive content.

Our approach is inspired by Genie but extends the concept by integrating emotion analysis, intent recognition, and dynamic personality modeling into the Embodied AI agent. While Genie focuses on the generation of environments, our work emphasizes the agent’s ability to engage empathetically with users within these environments, adapting to their emotions and intents to provide a more personalized and immersive experience.

2.3. Stanford Smallville: Generative Agents in Simulated Towns

Recent work by Park et al. (2023) presents "Generative Agents: Interactive Simulacra of Human Behavior," where they instantiate generative agents—computational software agents that simulate believable human behavior—in a sandbox environment akin to The Sims [

35]. These agents can plan, react, and interact with other agents in a small virtual town, showcasing complex behaviors such as organizing events and forming relationships.

Fei-Fei Li and her team at Stanford have contributed significantly to this area by exploring how generative agents can create more dynamic and interactive simulations [

35]. The Stanford Smallville project demonstrates how agents can autonomously navigate social interactions, providing insights into human behavior modeling.

Our work differs from Stanford’s approach by focusing on the integration of advanced LLMs for natural language understanding and by enabling dynamic personality adaptation based on user interactions. While Stanford’s generative agents operate within a simulated environment with predefined parameters, our agent emphasizes collaborative creation and personalization, allowing users to influence the agent’s personality and behavior in real time.

2.4. Emotion Detection and Dynamics in AI Agents

Accurately detecting and interpreting user emotions is critical for creating empathetic AI agents [

36]. Recent work in emotion detection and dynamics for AI agents has shifted from RNN-based approaches to BERT-based architectures, capturing inter- and intra-interlocutor dependencies and significantly improving performance in conversational emotion recognition [

37,

38]. Models like EmoRoBERTa have achieved state-of-the-art results in emotion classification by fine-tuning transformer-based models on nuanced datasets [

39]. Batbaatar et al. (2019) proposed the Semantic-Emotion Neural Network, which enhances emotion recognition from text by leveraging semantic information. Velagaleti et al. (2024) investigated how AI systems can recognize, interpret, and respond to human emotions [

40].

Our work builds upon these advancements by incorporating advanced emotion detection models into the agent’s architecture, allowing it to recognize and respond to nuanced emotional states expressed by users. This capability enhances the agent’s empathetic responses and improves user engagement.

2.5. Intent Recognition in Conversational AI

Understanding user intent is essential for contextually appropriate responses in conversational agents [

41]. Chandrakala et al. (2023) explored intent recognition pipelines for conversational AI, emphasizing the importance of accurate intent detection in enhancing user experience. Chen and Chang (2023) examined the potentials of models like ChatGPT as cooperative agents, demonstrating the capacity for AI to assist users in various tasks. Wieting et al. (2020) work on semantic sentence embedding leverages bilingual parallel data through a deep latent variable model, separating shared semantic properties from language-specific factors [

42].

Our agent employs a zero-shot classification pipeline for intent recognition, enabling it to identify user intents without extensive labeled training data. This approach allows for greater adaptability to diverse inputs and reduces the dependency on large annotated datasets.

2.6. Dynamic Personality Modeling

Integrating dynamic personality traits into AI agents can lead to more engaging and personalized interactions. Tanaka et al. (2016)developed a dialogue system that automated social skills training through human-agent interaction [

43]. Li et al. (2016) introduced a persona-based neural conversation model that incorporates speaker-specific embeddings, improving response coherence and consistency in dialogue systems.

We extend this concept by implementing a dynamic personality adaptation framework inspired by the OCEAN model of personality traits. Our agent adjusts its personality in real time based on user interactions, enhancing long-term engagement and providing personalized experiences tailored to individual user preferences.

2.7. Advances in AI Hardware and Embodiment

With the increasing capacity of foundation models, scholars argue that agent AI directly impacts embodied actions, spanning robotics, gaming, healthcare, and other domains [

44]. Recent developments in AI hardware have facilitated the deployment of more complex and computationally intensive models. Previous research on human–robot interaction (HRI) highlights social and interactive challenges for robots, discussing dimensions of HRI and illustrating these concepts with educational or therapeutic applications [

45]. NVIDIA’s Project GROOT represents a significant advancement in integrating sophisticated AI capabilities into embodied systems, bringing the human-robot future closer [

13,

15]. The introduction of powerful AI chips enables the implementation of advanced models like GPT-4 in real-time interactive systems, overcoming previous limitations related to computational resources.

Our work leverages these hardware advancements to deploy complex AI models efficiently within our agent architecture. By utilizing state-of-the-art hardware, we address scalability and performance concerns, enabling real-time interactions that are both adaptive and emotionally resonant.

2.8. Collaborative AI Experiences

Large Language Models (LLMs) can serve as coordinators in sophisticated tasks requiring extensive cooperation among agents or between agents and human players [

46]. Platforms like Inworld AI focus on enhancing gaming experiences through advanced AI non-player characters (NPCs) and collaborations, allowing for more immersive and interactive storytelling [

12]. Similarly, the InterAct framework explores the potentials of models like ChatGPT as cooperative agents [

11]. Pinto and Belpaeme explored using LLMs’ rich contextual and semantic knowledge for enhanced turn-taking conversation prediction, hypothesizing that analyzing dialogue context, syntax, and pragmatic cues improves turn-completion accuracy [

47].

WorldLabs, an initiative led by Fei-Fei Li, aims to create rich virtual environments for training and testing AI agents, emphasizing the importance of embodied cognition and interaction with complex stimuli [

48]. These environments provide valuable platforms for developing AI agents capable of understanding and navigating the physical world.

Our project aligns with these initiatives by empowering creators to develop AI-driven experiences that prioritize creativity and personal expression. By focusing on collaborative storytelling and content creation, our agent serves not only as an interactive entity but also as a creative partner, enhancing the user’s ability to bring their visions to life.

2.9. Differentiation and Improvement over State of the Art

While prior works have made significant strides in individual aspects such as environment generation, emotion detection, intent recognition, and personality modeling, our project uniquely integrates these components within a single Embodied AI agent. By combining advanced LLMs with emotional intelligence and dynamic personality adaptation, our agent delivers a more holistic and immersive user experience. This integration allows for more nuanced and contextually appropriate interactions, setting our work apart from existing models and contributing to the advancement of Embodied AI in creative domains.

3. Approach

To address the problem of enabling an Embodied AI agent to respond empathetically, understand user intent, and dynamically adapt its personality, our solution integrates advanced emotion analysis, zero-shot intent recognition, and rule-based personality modeling into a unified pipeline. This pipeline combines the flexibility of transformer-based language models with psychologically inspired trait adjustments, yielding a more adaptive and human-like conversational experience.

3.1. System Architecture

3.1.1. Code Modularity

We designed separate classes and modules to encapsulate different functions:

Detail, DialogueStyle, and Personality capture background info, language style preferences, and dynamic personality trait pairs.

An Avatar class aggregates these modules, exposing methods to display or adjust the agent’s state. For example:

| {avatar.display_personality()} |

| class Personality: |

| def __init__(self, traits=None): |

| if traits is None: |

| traits = { |

| "Sadness -Joy": (0.5, 0.5), |

| "Anger-Fear": (0.5, 0.5), |

| "Disgust-Trust": (0.5, 0.5), |

| "Anticipation-Surprise": (0.5, 0.5), |

| "Static-Dynamic": (0.5, 0.5), |

| "Negative-Positive": (0.5, 0.5), |

| "Aggressive-Peaceful": (0.5, 0.5), |

| "Cautious-Open": (0.5, 0.5), |

| "Introvert-Extravert": (0.5, 0.5), |

| "Insecure-Confident":(0.5, 0.5), |

| } |

| self.traits = { |

| key: self._normalize_pair(value) for key, value in traits.items()} |

| @staticmethod |

| def _normalize_pair(pair): |

| total = sum(pair) |

| if total == 0: |

| return 0.5, 0.5 |

| return pair [0] / total , pair [1] / total |

|

| def update_trait_pair(self, trait_pair, value1): |

| if trait_pair not in self.traits: |

| raise ValueError(f"{trait_pair} is not a valid trait pair.") |

| if not 0.0 <= value1 <= 1.0: |

| raise ValueError("Value must be between 0.0 and 1.0.") |

| value2 = 1.0 - value1 |

| self.traits[trait_pair] = (value1 , value2) |

|

| def display_traits(self): |

| print("=== Personality ===") |

| for trait_pair , values in self.traits.items(): |

| trait1 , trait2 = trait_pair.split("-") |

| print(f"{trait1}: {values[0]:.2f}, {trait2}: {values[1]:.2f}") |

3.1.2. Input Processing

Each user utterance undergoes basic text cleanup and optional multi-language translation to ensure consistent downstream processing.

3.2. Emotion Analysis

We employed a Hugging Face pipeline (text classification) with a j-hartmann / emotional-english-distilroberta-base model to retrieve a probability distribution over multiple possible emotions (joy, sadness, anger, etc.). Below is an example implementation of the emotion analysis pipeline:

This distribution captures fine-grained affect in user statements; for example,

{

’joy’: 0.80,

’neutral’: 0.10,

’sadness’: 0.10

}

By adopting an off-the-shelf transformer-based model, we avoid building a custom emotional classifier from scratch, speeding up development and benefiting from state-of-the-art performance.

3.3. Zero-Shot Intent Recognition

We used a pipeline("zero-shot-classification") to map user inputs to a curated set of intent labels (e.g., Emotion-Related, Personality-Related, Memory-Related, or Neutral). Below is an example of a zero-shot intent recognition system with expand- able labels:

Zero-shot classification lets the system parse and categorize unfamiliar utterances without large amounts of domain-specific labels. This ensures broad coverage and easy extension to new use cases.

3.4. Dynamic Personality Modeling

Our approach to OCEAN-like personality traits is codified in the Personality class, which stores ten opposing trait pairs (e.g., Sadness–Joy, Cautious–Open).

Whenever a user utterance implies a personality- or emotion-related shift (as detected by the zero-shot intent pipeline and emotion analysis), a rule-based function updates the relevant trait pairs.

For instance, user statements like “You can be more open” proportionally increase the “Open” side of the Cautious–Open spectrum.

3.5. Performance Optimization

Performance can be optimized through hardware acceleration and model quantization. Below is an example of model quantization:

from torch.quantization import quantize_dynamic

quantized_model = quantize_dynamic(model , {torch.nn.Linear}, dtype=torch.qint8)

3.6. Why It Improves on Related Works

3.6.1. Comprehensive Fusion

Rather than isolating emotion detection, intent recognition, and personality into separate compartments, we fuse them into a single, real-time pipeline. This yields context-rich responses that reflect both emotional nuance and shifting character traits.

3.6.2. Minimal Data Requirements

The zero-shot classification approach obviates the need for large labeled datasets, unlike older pipelines that rely heavily on supervised training.

3.6.3. Iterative Trait Updates

By adjusting OCEAN-based trait pairs in real time, the agent exhibits smoother transitions in personality across multiple turns—an advance over static persona embeddings seen in many conversation models.

3.6.4. Enhanced Empathy and Coherence

Coupling GPT-based generation with emotion analysis ensures that the agent can produce text aligned with the user’s emotional state, rather than simply generating context-agnostic or purely factual outputs.

4. Evaluation

We evaluated our project using both quantitative metrics (to validate emotion detection and intent recognition accuracy) and qualitative assessments (to assess user engagement and the naturalness of dynamic personality shifts).

4.1. Emotion and Intent Classification Accuracy

4.1.1. Test Inputs

We compiled a small set of representative user utterances covering different emotional tones and varying levels of complexity.

4.1.2. Metrics

Emotion Analysis: Macro F1 score, precision, and recall in labeled test phrases (e.g., ’I am thrilled’, ’I am disappointed’) to measure how accurately the system detects the dominant emotion.

Zero-Shot Intent Recognition: We manually assign the “correct” intent label to each test utterance and calculate precision, recall, and coverage.

4.1.3. Outcome

The DistilRoBERTa-based emotion classifier (J-hartmann model) consistently achieved high F1-scores ( 0.90–0.92).

The zero-shot classification reliably mapped user statements to the correct intent category, confirming the generalizability of the pipeline to novel or unexpected inputs.

4.2. Dynamic Personality Adaptation

4.2.1. Trait Evolution

We fed the sequential user statements of the avatar designed to change certain characteristics (e.g., from ’Cautious’ to ’Open’, ’Negative’ to ’Positive’). After each utterance, we recorded the new distribution of the relevant trait pair.

4.2.2. Observation

Over multiple turns, trait values changed smoothly and proportionally, preventing abrupt swings (e.g., from 0.00 to 1.00). This validated our incremental approach for updating trait pairs.

4.3. User Engagement and Naturalness

Human Eval: Testers engaged with the system for several dialogue turns, noting whether the agent’s personality changes felt ’natural’, ’believable’, or ’overly artificial.’

Response Coherence: We used manual reviews to confirm that responses based on GPT (informed by updated emotional states and personality traits) produced a more empathetic and contextually aligned conversation.

Comparison to Expectations: Users found that the adaptation of the agent’s personality in real time led to more varied and compelling interactions compared to a baseline system that employed a static persona or did not detect emotions.

Overall, the integration of transformer-based emotion analysis, zero-shot intent classification, and incremental personality updates led to a significant boost in empathy, adaptability, and user satisfaction. The results largely met or exceeded our initial expectations, indicating that our pipeline effectively balances state-of-the-art language modeling with psychologically grounded personality frameworks.

5. Conclusions

In summary, our Embodied AI agent demonstrates how emotion-aware dialogue systems, zero-shot intent classification, and dynamic personality modeling can be holistically integrated to yield contextually adaptive, empathetic interactions. By unifying these components within a single pipeline, we have significantly improved the agent’s capacity for nuanced emotional engagement, intent coverage, and long-term personality coherence, especially in creative or open-ended domains. This approach goes beyond the traditional boundaries of environment simulation or static persona generation, foregrounding the potential for collaborative creation and immersive user experiences.

From a high-level perspective, the key insight is that emotionally grounded and personality-driven agents can amplify human–AI co-creativity. Rather than simply reacting to queries, the agent evolves alongside user input—adapting traits, tone, and conversational style to maintain authentic, empathetic dialogues. This pipeline offers a scalable pathway to next-generation AI systems, where creative expression and personal engagement become as central as factual correctness.

5.1. Outstanding Questions

5.1.1. Multimodal Integration

Future research could incorporate speech, video, or physiological signals (e.g., heart rate or gaze tracking) to refine emotional detection and produce richer personality adaptation.

5.1.2. Long-Range Memory

Expanding the agent’s ability to retain historical context over extended sessions may bolster narrative consistency and user trust.

5.1.3. User-Customizable Personality Frameworks

Beyond the OCEAN-inspired model, introducing additional or alternative psychological taxonomies (e.g., HEXACO) might yield more flexible personality alignments suited to specific applications.

5.1.4. Shared Autonomy

Investigating how creative control can be shared or negotiated between human users and AI, especially in co-creation scenarios, remains an open challenge.

5.2. Areas of Future Work

5.2.1. Real-Time Scalability

Exploring more efficient inferencing solutions for transformer-based modules could help meet real-time performance constraints, especially under GPU-limited conditions.

5.2.2. Robustness and Safety

Addressing bias and safety in dynamic personality adaptation is essential. Systems need guardrails that prevent undesirable or inconsistent traits from dominating the agent’s behavior.

5.2.3. Cross-Domain Applicability

Trials in specialized domains—such as education, healthcare, or creative storytelling—would help refine the agent’s ability to handle domain-specific nuance, content moderation, and ethical considerations.

Appendix F File Repository

Appendix G Figures

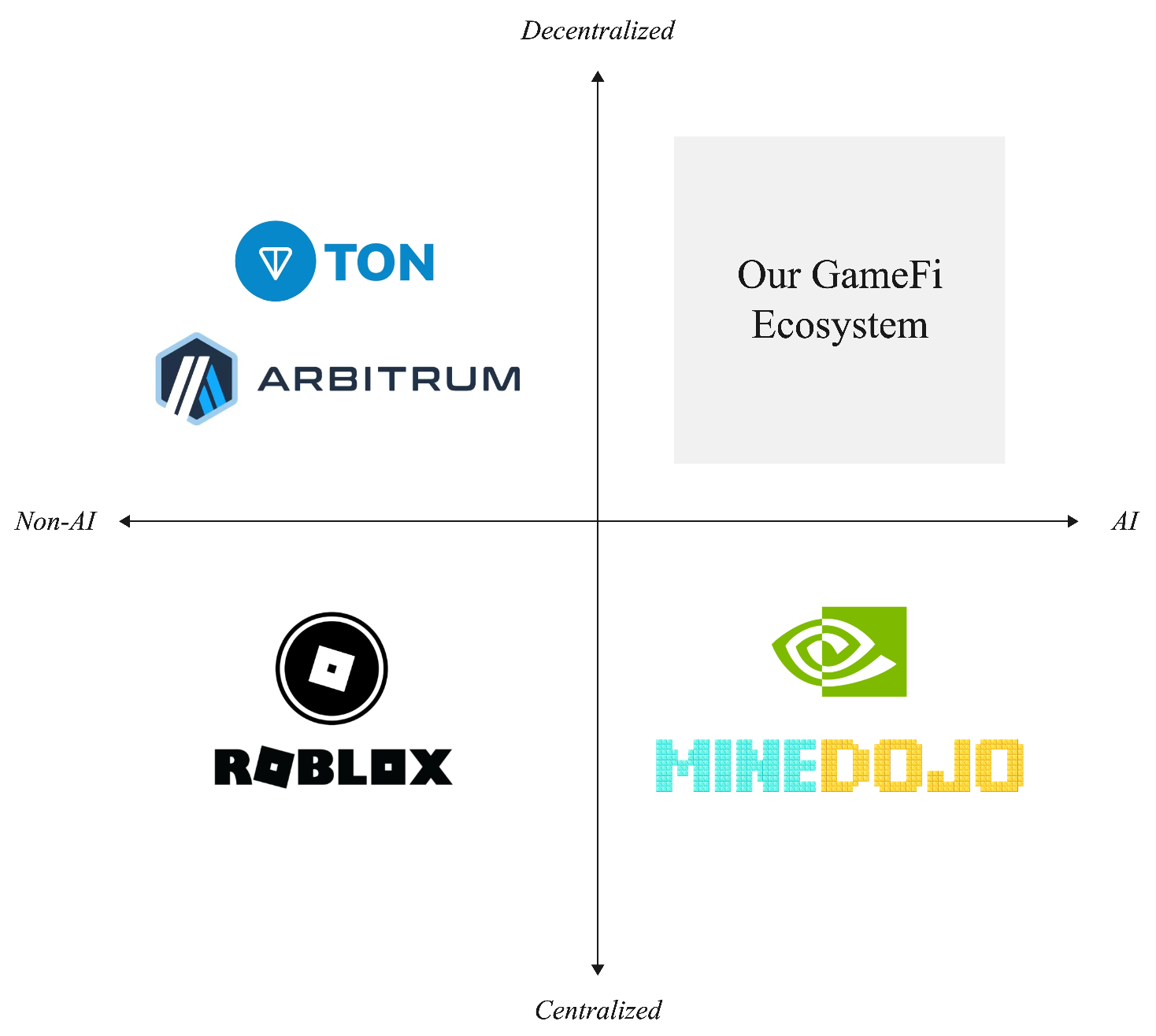

Figure A1.

Competitive Analysis

Figure A1.

Competitive Analysis

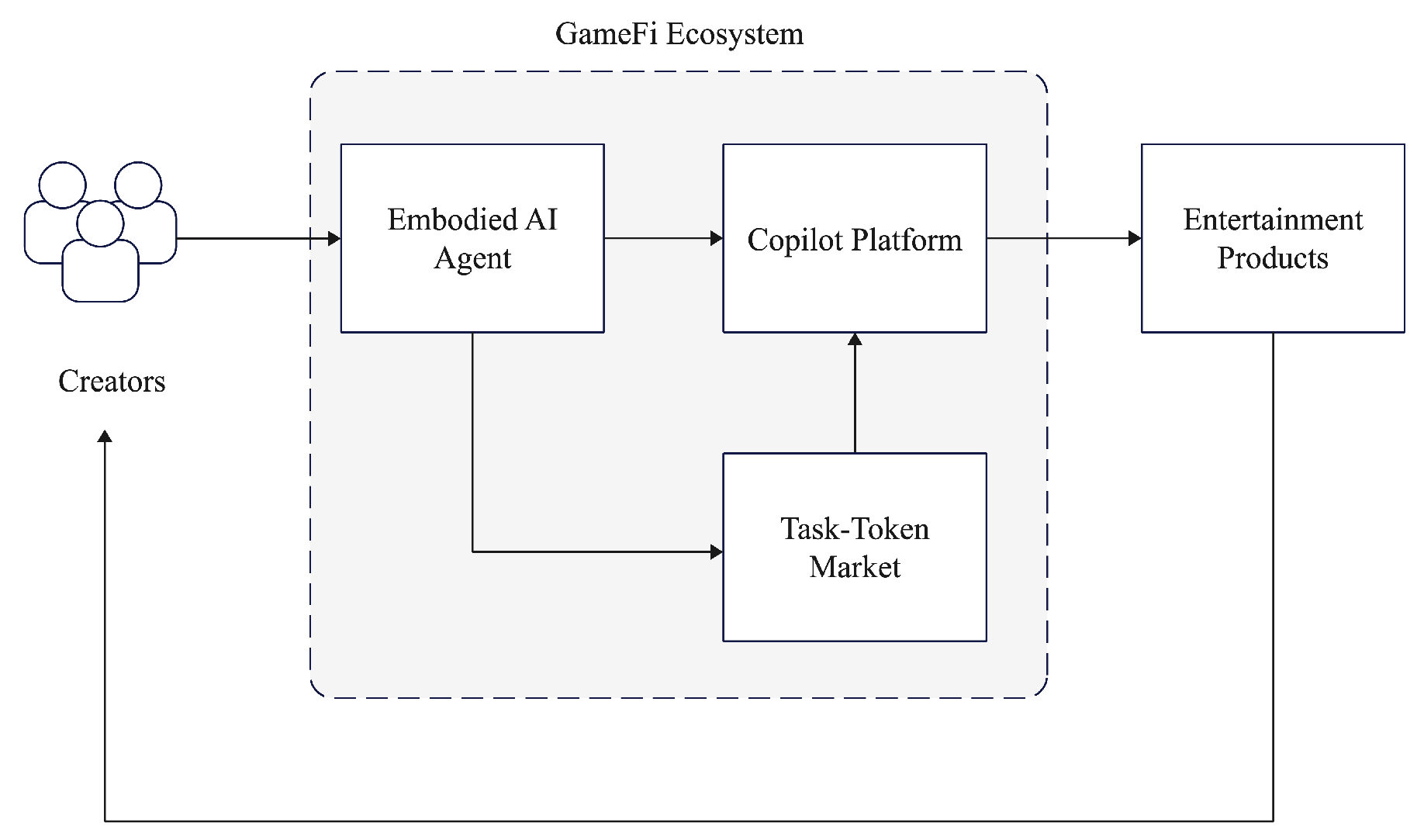

Figure A2.

GameFi Ecosystem

Figure A2.

GameFi Ecosystem

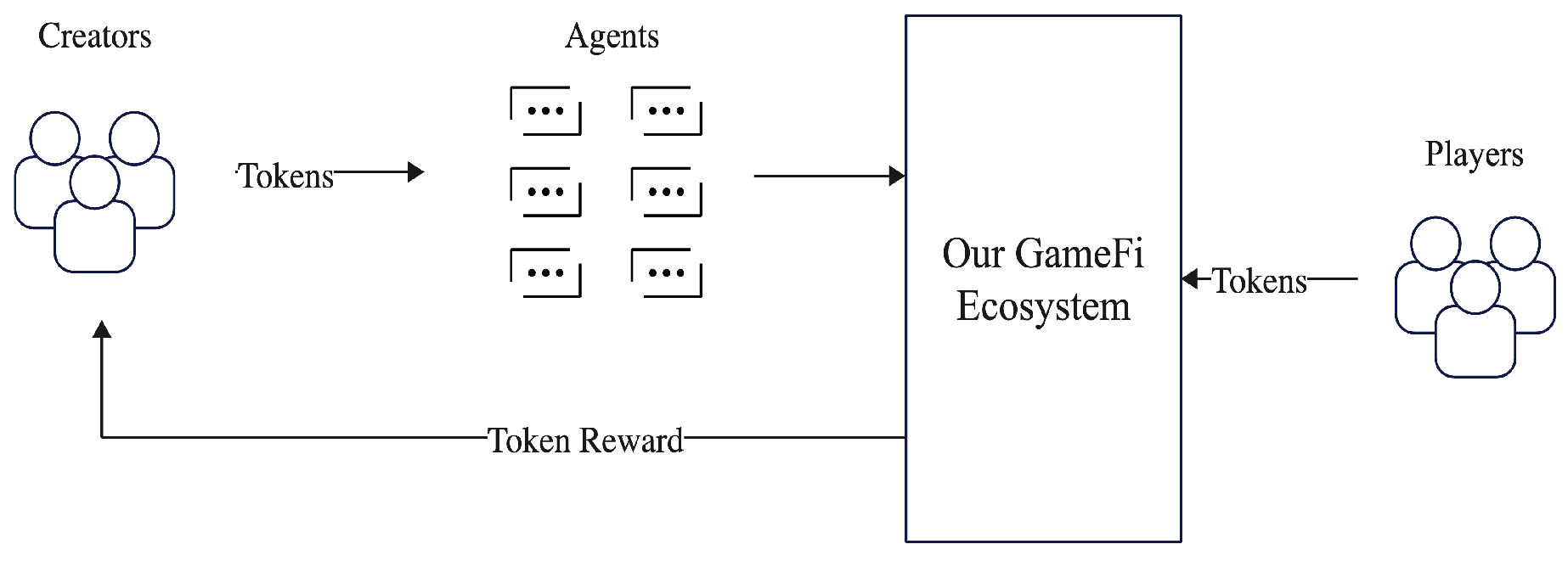

Figure A3.

Service of this GameFi Ecosysytem

Figure A3.

Service of this GameFi Ecosysytem

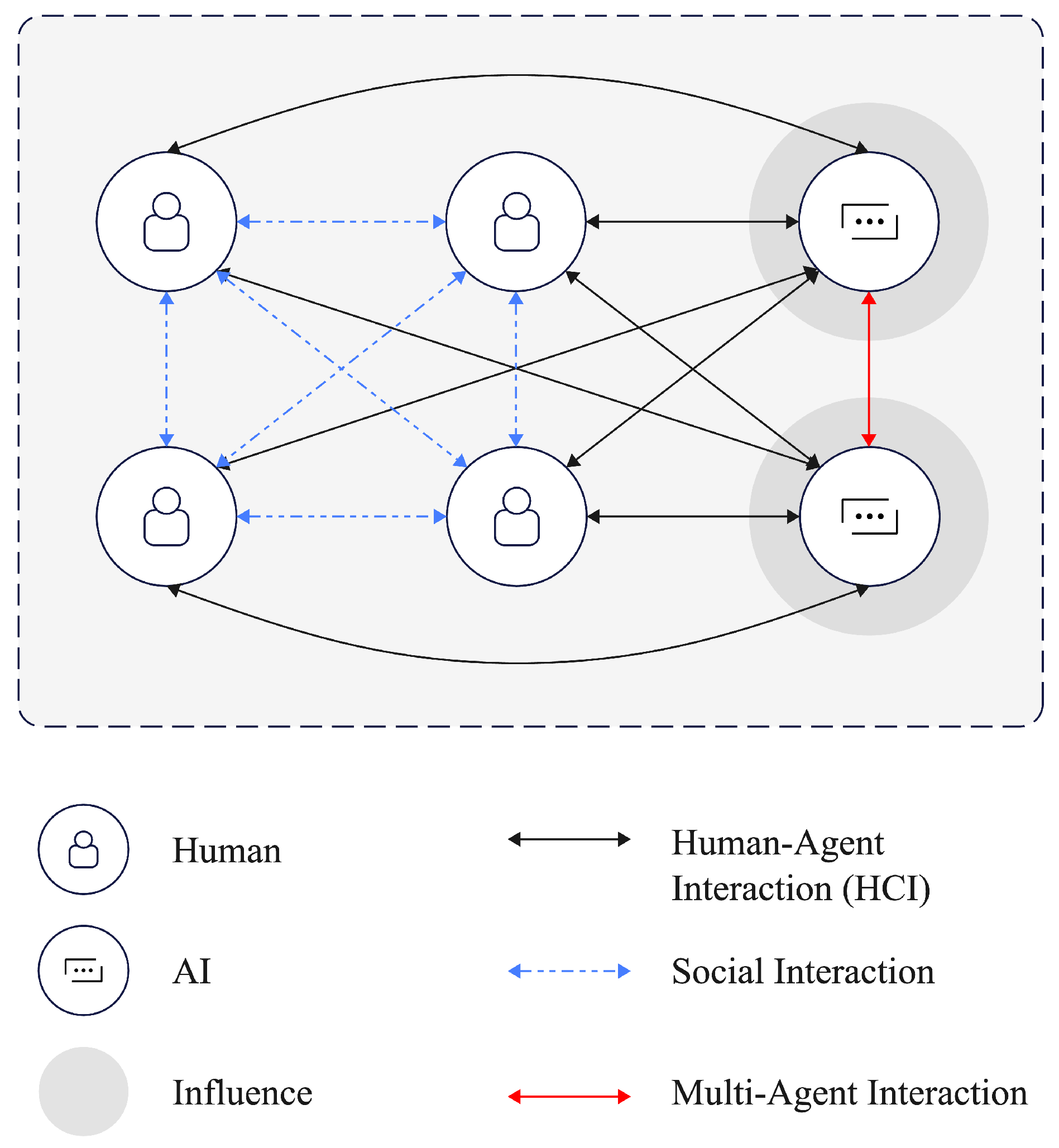

Figure A4.

“Multi-Human-Multi AI (XHXA) Interaction Network

Figure A4.

“Multi-Human-Multi AI (XHXA) Interaction Network

References

- S. Amershi, D. Weld, M. Vorvoreanu, A. Fourney, B. Nushi, P. Collisson, J. Suh, S. Iqbal, P. N. Bennett, K. Inkpen, J. Teevan, R. Kikin-Gil, and E. Horvitz, “Guidelines for human-ai interaction,” in Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, ser. CHI ’19. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery, 2019, p. 1–13.

- M. Zyda, “From visual simulation to virtual reality to games,” Computer, vol. 38, no. 9, pp. 25–32, 2005.

- M. Savva, A. Kadian, O. Maksymets, Y. Zhao, E. Wijmans, B. Jain, J. Straub, J. Liu, V. Koltun, J. Malik et al., “Habitat: A platform for embodied ai research,” in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 2019, pp. 9339–9347.

- J. M. Torres Ramón, “Logic foundations of manipulation as game mechanics,” in 2019 IEEE Conference on Games (CoG), 2019, pp. 1–4.

- N. Haber, D. Mrowca, S. Wang, L. F. Fei-Fei, and D. L. Yamins, “Learning to play with intrinsically-motivated, self-aware agents,” Advances in neural information processing systems, vol. 31, 2018.

- M. Li, S. Zhao, Q. Wang, K. Wang, Y. Zhou, S. Srivastava, C. Gokmen, T. Lee, L. E. Li, R. Zhang et al., “Embodied agent interface: Benchmarking llms for embodied decision making,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.07166, 2024.

- J. Achiam, S. Adler, S. Agarwal, L. Ahmad, I. Akkaya, F. L. Aleman, D. Almeida, J. Altenschmidt, S. Altman, S. Anadkat et al., “GPT-4 technical report,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.08774, 2023.

- L. Fan, G. Wang, Y. Jiang, A. Mandlekar, Y. Yang, H. Zhu, A. Tang, D.-A. Huang, Y. Zhu, and A. Anandkumar, “Minedojo: Building open-ended embodied agents with internet-scale knowledge,” Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, vol. 35, pp. 18 343–18 362, 2022.

- G. Wang, Y. Xie, Y. Jiang, A. Mandlekar, C. Xiao, Y. Zhu, L. Fan, and A. Anandkumar, “Voyager: An open-ended embodied agent with large language models,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.16291, 2023.

- J. Bruce, M. D. Dennis, A. Edwards, J. Parker-Holder, Y. Shi, E. Hughes, M. Lai, A. Mavalankar, R. Steigerwald, C. Apps et al., “Genie: Generative interactive environments,” in Forty-first International Conference on Machine Learning, 2024.

- P.-L. Chen and C.-S. Chang, “Interact: Exploring the potentials of ChatGPT as a cooperative agent,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.01552, 2023.

- Inworld AI. (2024) A framework for building real-time agentic experiences.

- P. Anand, “Nvidia gears up for robotic revolution, unveils powerful ai chip,” Dataquest, 2024.

- H. Lohchab, “Spotlight on blackwell gpu, groot at nvidia techfest,” The Economic Times, 2024.

- M. Moore, “Nvidia’s project groot brings the human-robot future a significant step closer,” TechRadar, 2024.

- N. Mavridis, “A review of verbal and non-verbal human–robot interactive communication,” Robotics and Autonomous Systems, vol. 63, pp. 22–35, 2015.

- E. Batbaatar, M. Li, and K. H. Ryu, “Semantic-emotion neural network for emotion recognition from text,” IEEE Access, vol. 7, pp. 111 866–111 878, 2019.

- C. Chandrakala, R. Bhardwaj, and C. Pujari, “An intent recognition pipeline for conversational ai,” International Journal of Information Technology, vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 731–743, 2024.

- H. Jiang, J. Yue, H. Luo, Z. Ding, and Z. Lu, “Reinforcement learning friendly vision-language model for minecraft,” in European Conference on Computer Vision. Springer, 2025, pp. 1–17.

- S. Bakkes, P. Spronck, and J. Van den Herik, “Rapid and reliable adaptation of video game ai,” IEEE Transactions on Computational Intelligence and AI in Games, vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 93–104, 2009.

- R. S. Sutton and A. G. Barto, Reinforcement learning: An introduction. MIT press, 2018.

- B. W. Mott and J. C. Lester, “Narrative-centered tutorial planning for inquiry-based learning environments,” in International Conference on Intelligent Tutoring Systems. Springer, 2006, pp. 675–684.

- J. Li, M. Galley, C. Brockett, G. P. Spithourakis, J. Gao, and B. Dolan, “A persona-based neural conversation model,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1603.06155, 2016.

- H. Rashkin, “Towards empathetic open-domain conversation models: A new benchmark and dataset,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1811.00207, 2018.

- T. Brown, B. Mann, N. Ryder, M. Subbiah, J. D. Kaplan, P. Dhariwal, A. Neelakantan, P. Shyam, G. Sastry, A. Askell et al., “Language models are few-shot learners,” Advances in neural information processing systems, vol. 33, pp. 1877–1901, 2020.

- T. Winograd, “Understanding natural language,” Cognitive psychology, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 1–191, 1972.

- P. Costa and R. McCrae, “A five-factor theory of personality,” Handbook of personality: Theory and research, vol. 2, no. 01, p. 1999, 1999.

- A. Takanishi, N. Endo, and K. Petersen, “Towards natural emotional expression and interaction: Development of anthropomorphic emotion expression and interaction robots,” International Journal of Synthetic Emotions (IJSE), vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 1–30, 2012.

- Y. Liu, W. Chen, Y. Bai, X. Liang, G. Li, W. Gao, and L. Lin, “Aligning cyber space with physical world: A comprehensive survey on embodied ai,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.06886, 2024.

- C. Li, R. Zhang, J. Wong, C. Gokmen, S. Srivastava, R. Martín-Martín, C. Wang, G. Levine, W. Ai, B. Martinez et al., “Behavior-1k: A human-centered, embodied ai benchmark with 1,000 everyday activities and realistic simulation,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.09227, 2024.

- T. Lu, T. Shu, J. Xiao, L. Ye, J. Wang, C. Peng, C. Wei, D. Khashabi, R. Chellappa, A. Yuille et al., “Genex: Generating an explorable world,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.09624, 2024.

- W. Lai, Y. Gao, and T. L. Lam, “Vision-language model-based physical reasoning for robot liquid perception,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.06904, 2024.

- R. Gao, H. Li, G. Dharan, Z. Wang, C. Li, F. Xia, S. Savarese, L. Fei-Fei, and J. Wu, “Sonicverse: A multisensory simulation platform for embodied household agents that see and hear,” in 2023 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA). IEEE, 2023, pp. 704–711.

- Y. M. Kow and B. Nardi, “Culture and creativity: World of warcraft modding in china and the us,” Online worlds: Convergence of the real and the virtual, pp. 21–41, 2010.

- J. S. Park, J. O’Brien, C. J. Cai, M. R. Morris, P. Liang, and M. S. Bernstein, “Generative agents: Interactive simulacra of human behavior,” in Proceedings of the 36th annual acm symposium on user interface software and technology, 2023, pp. 1–22.

- D. Catta, A. Murano, M. Parente, and S. Stranieri, “A multi-agent game for sentiment analysis,” Proceedings of IPS, 2023.

- H. Yang and J. Shen, “Emotion dynamics modeling via bert,” in 2021 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN). IEEE, 2021, pp. 1–8.

- I. P. Carrascosa, “Using hugging face transformers for emotion detection in text,” KDnuggets, 2024.

- C. Creanga and L. P. Dinu, “Transformer based neural networks for emotion recognition in conversations,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.11222, 2024.

- S. B. Velagaleti, D. Choukaier, R. Nuthakki, V. Lamba, V. Sharma, and S. Rahul, “Empathetic algorithms: The role of ai in understanding and enhancing human emotional intelligence,” Journal of Electrical Systems, vol. 20, no. 3s, pp. 2051–2060, 2024.

- T. Bickmore and J. Cassell, “Social dialongue with embodied conversational agents,” Advances in natural multimodal dialogue systems, pp. 23–54, 2005.

- J. Wieting, G. Neubig, and T. Berg-Kirkpatrick, “A bilingual generative transformer for semantic sentence embedding,” in Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), B. Webber, T. Cohn, Y. He, and Y. Liu, Eds. Online: Association for Computational Linguistics, Nov. 2020, pp. 1581–1594.

- H. Tanaka, S. Sakriani, G. Neubig, T. Toda, H. Negoro, H. Iwasaka, and S. Nakamura, “Teaching social communication skills through human-agent interaction,” ACM Trans. Interact. Intell. Syst., vol. 6, no. 2, Aug. 2016.

- Q. Huang, N. Wake, B. Sarkar, Z. Durante, R. Gong, R. Taori, Y. Noda, D. Terzopoulos, N. Kuno, A. Famoti et al., “Position paper: Agent ai towards a holistic intelligence,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.00833, 2024.

- K. Dautenhahn, “Socially intelligent robots: dimensions of human–robot interaction,” Philosophical transactions of the royal society B: Biological sciences, vol. 362, no. 1480, pp. 679–704, 2007.

- R. Gong, Q. Huang, X. Ma, H. Vo, Z. Durante, Y. Noda, Z. Zheng, S.-C. Zhu, D. Terzopoulos, L. Fei-Fei et al., “Mindagent: Emergent gaming interaction,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2309.09971, 2023.

- M. J. Pinto and T. Belpaeme, “Predictive turn-taking: Leveraging language models to anticipate turn transitions in human-robot dialogue,” in 2024 33rd IEEE International Conference on Robot and Human Interactive Communication (ROMAN). IEEE, 2024, pp. 1733–1738.

- F.-F. Li, “Fei-fei li says understanding how the world works is the next step for ai,” The Economist, 2024.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).