Submitted:

11 January 2025

Posted:

13 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

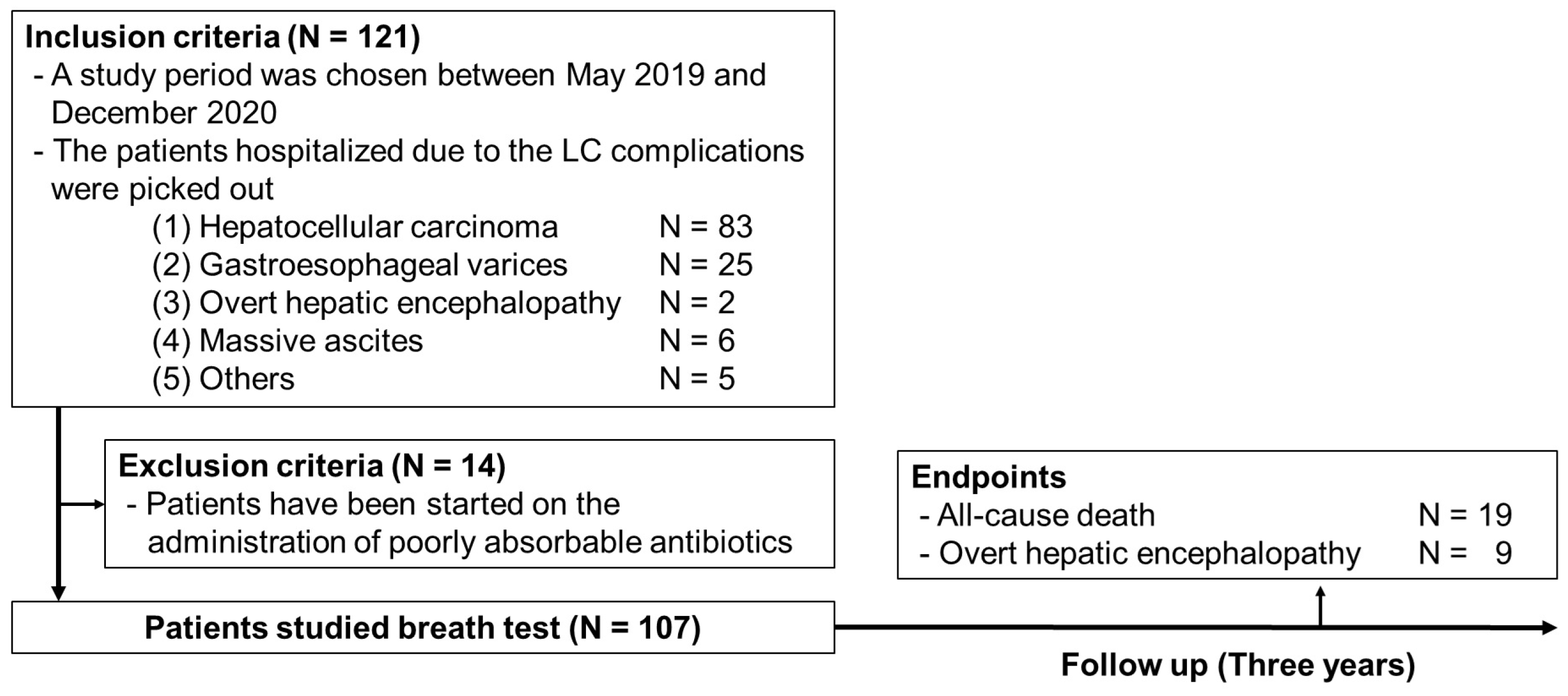

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Protocol

2.2. Breath Test

2.3. Neuro-Psychological Tests

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LC | Liver cirrhosis |

| SIBO | Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth |

| HE | Hepatic encephalopathy |

| H-SIBO | Hydrogen producing SIBO |

| M-SIBO | Methane producing SIBO |

| NCT | Number connection test |

| HCC | Hepatocellular carcinoma |

| UICC | Union for International Cancer Control |

| BCLC | Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer |

| HR | Hazard ratio |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| T-bil | Total bilirubin |

| AST | Aspartate aminotransferase |

| BUN | Blood urea nitrogen |

| WBC | White blood cell |

References

- Schuppan, D.; Afdhal, N.H. Liver cirrhosis. Lancet 2008, 371, 838-851.

- Marshall, A.D.; Willing, A.R.; Kairouz, A.; Cunningham, E.B.; Wheeler, A.; O’Brien, N.; Perera, V.; Ward, J.W.; Hiebert, L.; Degenhardt, L.; et al. Direct-acting antiviral therapies for hepatitis c infection: Global registration, reimbursement, and restrictions. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024, 9, 366-382.

- Enomoto, H.; Akuta, N.; Hikita, H.; Suda, G.; Inoue, J.; Tamaki, N.; Ito, K.; Akahane, T.; Kawaoka, T.; Morishita, A.; et al. Etiological changes of liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma-complicated liver cir-rhosis in japan: Updated nationwide survey from 2018 to 2021. Hepatol Res. 2024, 54, 763-772.

- Maslennikov, R.; Pavlov, C.; Ivashkin, V. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in cirrhosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatol. Int. 2018, 12, 567–576. [CrossRef]

- Nicoletti, A.; Ponziani, F.R.; Biolato, M.; Valenza, V.; Marrone, G.; Sganga, G.; Gasbarrini, A.; Miele, L.; Grieco, A. Intestinal permeability in the pathogenesis of liver damage: From non-alcoholic fatty liver disease to liver transplantation. World J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 25, 4814–4834. [CrossRef]

- Bernsmeier, C.; van der Merwe, S.; Périanin, A. Innate immune cells in cirrhosis. J. Hepatol. 2020, 73, 186–201. [CrossRef]

- Wiest, R.; Lawson, M.; Geuking, M. Pathological bacterial translocation in liver cirrhosis. J. Hepatol. 2014, 60, 197–209. [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, M.; Uemura, M.; Matsuyama, T.; Matsumoto, M.; Ishizashi, H.; Kato, S.; Morioka, C.; Fujimoto, M.; Kojima, H.; Yoshiji, H.; et al. Potential Role of Enhanced Cytokinemia and Plasma Inhibitor on the Decreased Activity of Plasma ADAMTS13 in Patients with Alcoholic Hepatitis: Relationship to Endotoxemia. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2010, 34, S25–S33. [CrossRef]

- Creely, S.J.; McTernan, P.G.; Kusminski, C.M.; Fisher f, M.; Da Silva, N.F.; Khanolkar, M.; Evans, M.; Harte, A.L.; Kumar, S. Lipopolysaccharide activates an innate immune system response in human adipose tissue in obesity and type 2 diabetes. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2007, 292, E740-747.

- Yokoyama, K.; Sakamaki, A.; Takahashi, K.; Naruse, T.; Sato, C.; Kawata, Y.; Tominaga, K.; Abe, H.; Sato, H.; Tsuchiya, A.; et al. Hydrogen-producing small intestinal bacterial overgrowth is associated with hepatic en-cephalopathy and liver function. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0264459.

- Patidar, K.R.; Thacker, L.R.; Wade, J.B.; Sterling, R.K.; Sanyal, A.J.; Siddiqui, M.S.; Matherly, S.C.; Stravitz, R.T.; Puri, P.; Luketic, V.A.; et al. Covert hepatic encephalopathy is independently associated with poor sur-vival and increased risk of hospitalization. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 109, 1757-1763.

- Vierling, J.M.; Mokhtarani, M.; Brown, R.S.; Jr., Mantry, P.; Rockey, D.C.; Ghabril, M.; Rowell, R.; Jurek, M.; Coakley, D.F.; Scharschmidt, B.F. Fasting blood ammonia predicts risk and frequency of hepatic encephalopathy episodes in patients with cirrhosis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 14, 903-906.

- Quigley, E.M.; Abu-Shanab, A. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2010, 24, 943-959.

- Suri, J.; Kataria, R.; Malik, Z.; Parkman, H.P.; Schey, R. Elevated methane levels in small intestinal bacterial overgrowth suggests delayed small bowel and colonic transit. Medicine 2018, 97, e10554. [CrossRef]

- Kato, A.; Tanaka, H.; Kawaguchi, T.; Kanazawa, H.; Iwasa, M.; Sakaida, I.; Moriwaki, H.; Murawaki, Y.; Suzuki, K.; Okita, K. Nutritional management contributes to improvement in minimal hepatic encephalopathy and quality of life in patients with liver cirrhosis: A preliminary, prospective, open-label study. Hepatol. Res. 2012, 43, 452–458. [CrossRef]

- Kawaguchi, T.; Konishi, M.; Kato, A.; Kato, M.; Kooka, Y.; Sawara, K.; Endo, R.; Torimura, T.; Suzuki, K.; Takikawa, Y. Updating the neuropsychological test system in Japan for the elderly and in a modern touch screen tablet society by resetting the cut-off values. Hepatol. Res. 2017, 47, 1335–1339. [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, M.; Lin, H.C.; Enayati, P.; Burg, B.v.D.; Lee, H.-R.; Chen, J.H.; Park, S.; Kong, Y.; Conklin, J. Methane, a gas produced by enteric bacteria, slows intestinal transit and augments small intestinal contractile activity. Am. J. Physiol. Liver Physiol. 2006, 290, G1089–G1095. [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Park, S.; Low, K.; Kong, Y.; Pimentel, M. The Degree of Breath Methane Production in IBS Correlates with the Severity of Constipation. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2007, 102, 837–841. [CrossRef]

- Kunkel, D.; Basseri, R.J.; Makhani, M.D.; Chong, K.; Chang, C.; Pimentel, M. Methane on Breath Testing Is Associated with Constipation: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2011, 56, 1612–1618. [CrossRef]

- Pantham, G.; Post, A.; Venkat, D.; Einstadter, D.; Mullen, K.D. A New Look at Precipitants of Overt Hepatic Encephalopathy in Cirrhosis. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2017, 62, 2166–2173. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Sharma, B.C.; Puri, V.; Sarin, S.K. An open-label randomized controlled trial of lactulose and probiotics in the treatment of minimal hepatic encephalopathy. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2008, 20, 506–511. [CrossRef]

- Malaguarnera, M.; Gargante, M.P.; Malaguarnera, G.; Salmeri, M.; Mastrojeni, S.; Rampello, L.; Pennisi, G.; Volti, G.L.; Galvano, F. Bifidobacterium combined with fructo-oligosaccharide versus lactulose in the treatment of patients with hepatic encephalopathy. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2010, 22, 199–206. [CrossRef]

- Gluud, L.L.; Vilstrup, H.; Morgan, M.Y. Nonabsorbable disaccharides for hepatic encephalopathy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatology 2016, 64, 908–922. [CrossRef]

- Easl clinical practice guidelines on the management of hepatic encephalopathy. J. Hepatol. 2022, 77, 807-824.

- Vilstrup, H.; Amodio, P.; Bajaj, J.; Cordoba, J.; Ferenci, P.; Mullen, K.D.; Weissenborn, K.; Wong, P. Hepatic encephalopathy in chronic liver disease: 2014 Practice Guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the European Association for the Study of the Liver. Hepatology 2014, 60, 715–735. [CrossRef]

- Yoshiji, H.; Nagoshi, S.; Akahane, T.; Asaoka, Y.; Ueno, Y.; Ogawa, K.; Kawaguchi, T.; Kurosaki, M.; Sakaida, I.; Shimizu, M.; et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for Liver Cirrhosis 2020. J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 56, 593–619. [CrossRef]

- Sama, C.; Morselli-Labate, A.M.; Pianta, P.; Lambertini, L.; Berardi, S.; Martini, G. Clinical effects of rifaximin in patientswith hepatic encephalopathy intolerant or nonresponsive to previous lactulose treatment: An open-label, pilot study. Curr. Ther. Res. 2004, 65, 413–422. [CrossRef]

- Kwok, R.; Tse, Y.K.; Wong, G.L.; Ha, Y.; Lee, A.U.; Ngu, M.C.; Wong, V.S. Systematic review with meta-analysis: non-invasive assessment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease—The role of transient elastography and plasma cytokeratin-18 fragments. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2014;39, 254–269.

- Gatta, L.; Scarpignato, C. Systematic review with meta-analysis: rifaximin is effective and safe for the treatment of small intestine bacterial overgrowth. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017, 45, 604–616. [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, M.; Chang, C.; Chua, K.S.; Mirocha, J.; DiBaise, J.; Rao, S.; Amichai, M. Antibiotic Treatment of Constipation-Predominant Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2014, 59, 1278–1285. [CrossRef]

- Rezaie, A.; Pimentel, M.; Rao, S.S. How to test and treat small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: An evidence-based approach. Curr. Gastroenterol Rep. 2016, 18, 8.

- Low, K.; Hwang, L.; Hua, J.; Zhu, A.; Morales, W.; Pimentel, M. A Combination of Rifaximin and Neomycin Is Most Effective in Treating Irritable Bowel Syndrome Patients With Methane on Lactulose Breath Test. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2010, 44, 547–550. [CrossRef]

| median (min – max) | median (min – max) | ||

| or n (%) | N = 107 | or n (%) | N = 107 |

| Age, years | 70 (40 - 86) | Cholinesterase, U/L | 210 (47 – 484) |

| Gender | Albumin, g/dL | 3.8 (2.1 – 5.0) | |

| Males | 81 (75.7) | Total bilirubin, mg/dL | 0.9 (0.3 – 14.2) |

| Females | 26 (24.3) | Prothrombin time, % | 92 (25 - 131) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 24.8 (12.6 - 47.7) | Ammonia, μg/dL | 64 (28 - 242) |

| The etiology of liver cirrhosis | Creatinine, mg/dL | 0.81 (0.45 – 3.31) | |

| Hepatitis B virus | 20 (18.7) | Blood urea nitrogen, mg/dL | 16 (5 – 61) |

| Hepatitis C virus | 23 (21.5) | White blood cell count, x103/µL | 4.3 (1.3 – 14.8) |

| Alcoholic liver disease | 31 (29.0) | Platelet count, x104/µL | 10.9 (2.6 – 26.3) |

| Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis | 23 (21.5) | Child-Pugh score | 5 (5 – 12) |

| Others | 10 ( 9.3) | Child Pugh grade (A/B/C) | 85 / 17 / 5 |

| PPI administration | 63 (58.9) | ALBI score | -2.45 (-0.47 – -3.32) |

| HCC complication | 77 (72.0) | mALBI grade (1/2a/2b/3) | 38 / 29 / 31 / 9 |

| UICC stage of HCC (I/II/III/IV) | 18 / 29 / 17 / 13 | Covert HE | 30 (28.0) |

| BCLC stage of HCC (I/II/III/IV) | 30 / 31 / 14 / 2 | SIBO | 31 (29.0) |

| Aspartate aminotransferase, U/L | 36 (12 – 209) | Hydrogen producing SIBO | 16 (15.0) |

| Alanine aminotransferase, U/L | 29 (10 – 217) | Methane producing SIBO | 19 (17.8) |

| Alkaline Phosphatase, U/L | 281 (64 – 3147) | Observation period, m | 29.4 (0.9 – 36.0) |

| Gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase, U/L | 68 (13 – 691) | ||

| PPI, proton pump inhibitor; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; UICC, Union for International Cancer Control; BCLC, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer; ALBI, Albumin-Bilirubin; mALBI, modified ALBI; HE, hepatic encephalopathy; SIBO, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. | |||

| univariate analysis | multivariate analysis | |||

| p value | hazard ratio | p value | hazard ratio | |

| Age, years | 0.948 | 1.002 (0.956 – 1.049) | ||

| Gender | 0.210 | 0.392 (0.090 – 1.696) | ||

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 0.431 | 1.031 (0.955 – 1.114) | ||

| The etiology of liver cirrhosis | ||||

| Hepatitis B virus | ||||

| Hepatitis C virus | ||||

| Alcoholic liver disease | ||||

| Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis | ||||

| Others | ||||

| PPI administration | 0.109 | 0.474 (0.191 – 1.181) | ||

| HCC complication | 0.102 | 3.399 (0.785 – 14.721) | ||

| UICC stage of HCC (0/I/II/III/IV) | < 0.001* | 2.323 (1.540 – 3.503) | < 0.001* | 2.767 (1.780 – 4.302) |

| BCLC stage of HCC (0/I/II/III/IV) | < 0.001* | 2.259 (1.480 – 3.446) | ||

| Aspartate aminotransferase, U/L | 0.037* | 1.013 (1.001 – 1.025) | 0.074 | |

| Alanine aminotransferase, U/L | 0.146 | 1.013 (0.996 – 1.030) | ||

| Alkaline Phosphatase, U/L | ||||

| Gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase, U/L | ||||

| Cholinesterase, U/L | ||||

| Albumin, g/dL | 0.424 | 0.712 (0.309 – 1.639) | ||

| Total bilirubin, mg/dL | 0.025* | 1.247 (1.028 – 1.513) | ||

| Prothrombin time, % | 0.768 | 1.004 (0.979 – 1.030) | ||

| Ammonia, μg/dL | 0.348 | 1.006 (0.993 – 1.020) | ||

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 0.316 | 1.587 (0.643 – 3.914) | ||

| Blood urea nitrogen, mg/dL | 0.009* | 1.047 (1.011 – 1.084) | 0.001* | 1.076 (1.030 – 1.123) |

| White blood cell count, x103/µL | 0.021* | 1.193 (1.027 – 1.385) | 0.626 | |

| Platelet count, x104/µL | 0.173 | 1.052 (0.978 – 1.131) | ||

| Child-Pugh score | 0.471 | 1.117 (0.827 – 1.508) | ||

| Child Pugh grade (A/B/C) | 0.193 | 1.701 (0.764 – 3.790) | 0.001* | 3.733 (1.592 – 8.754) |

| ALBI score | 0.392 | 1.448 (0.620 – 3.381) | ||

| mALBI grade (1/2a/2b/3) | 0.732 | 1.086 (0.676 – 1.747) | ||

| Covert HE | 0.479 | 1.418 (0.539 – 3.733) | ||

| SIBO | 0.483 | 1.414 (0.537 – 3.721) | ||

| Hydrogen producing SIBO | 0.130 | 2.348 (0.777 – 7.096) | ||

| Methane producing SIBO | 0.983 | 1.013 (0.295 – 3.479) | ||

| PPI, proton pump inhibitor; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; UICC, Union for International Cancer Control; BCLC, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer; ALBI, Albumin-Bilirubin; mALBI, modified ALBI; HE, hepatic encephalopathy; SIBO, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. *: P value < 0.05. | ||||

| univariate analysis | multivariate analysis | |||

| p value | hazard ratio | p value | hazard ratio | |

| Age, years | 0.631 | 0.982 (0.914 – 1.056) | ||

| Gender | 0.218 | 2.562 (0.573 – 11.458) | ||

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 0.159 | 1.079 (0.971 – 1.199) | ||

| The etiology of liver cirrhosis | ||||

| Hepatitis B virus | ||||

| Hepatitis C virus | ||||

| Alcoholic liver disease | ||||

| Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis | ||||

| Others | ||||

| PPI administration | 0.310 | 0.460 (0.102 – 2.062) | ||

| HCC complication | 0.406 | 2.455 (0.295 – 20.423) | ||

| UICC stage of HCC (0/I/II/III/IV) | 0.029* | 2.046 (1.076 – 3.889) | 0.065 | |

| BCLC stage of HCC (0/I/II/III/IV) | 0.088 | 1.804 (0.917 – 3.551) | ||

| Aspartate aminotransferase, U/L | 0.065 | 1.017 (0.999 – 1.035) | ||

| Alanine aminotransferase, U/L | 0.587 | 1.009 (0.977 – 1.041) | ||

| Alkaline Phosphatase, U/L | ||||

| Gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase, U/L | ||||

| Cholinesterase, U/L | ||||

| Albumin, g/dL | 0.178 | 0.443 (0.135 – 1.449) | ||

| Total bilirubin, mg/dL | 0.189 | 1.202 (0.913 – 1.581) | ||

| Prothrombin time, % | 0.406 | 0.985 (0.949 – 1.021) | ||

| Ammonia, μg/dL | 0.079 | 1.016 (0.998 – 1.035) | 0.145 | |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 0.476 | 1.719 (0.387 – 7.632) | ||

| Blood urea nitrogen, mg/dL | 0.338 | 1.036 (0.964 – 1.114) | ||

| White blood cell count, x103/µL | 0.391 | 0.804 (0.488 – 1.324) | ||

| Platelet count, x104/µL | 0.443 | 0.940 (0.803 – 1.100) | ||

| Child-Pugh score | 0.148 | 1.328 (0.904 – 1.952) | ||

| Child Pugh grade (A/B/C) | 0.165 | 2.270 (0.714 – 7.221) | ||

| ALBI score | 0.109 | 2.625 (0.806 – 8.551) | ||

| mALBI grade (1/2a/2b/3) | 0.129 | 1.826 (0.840 – 3.970) | ||

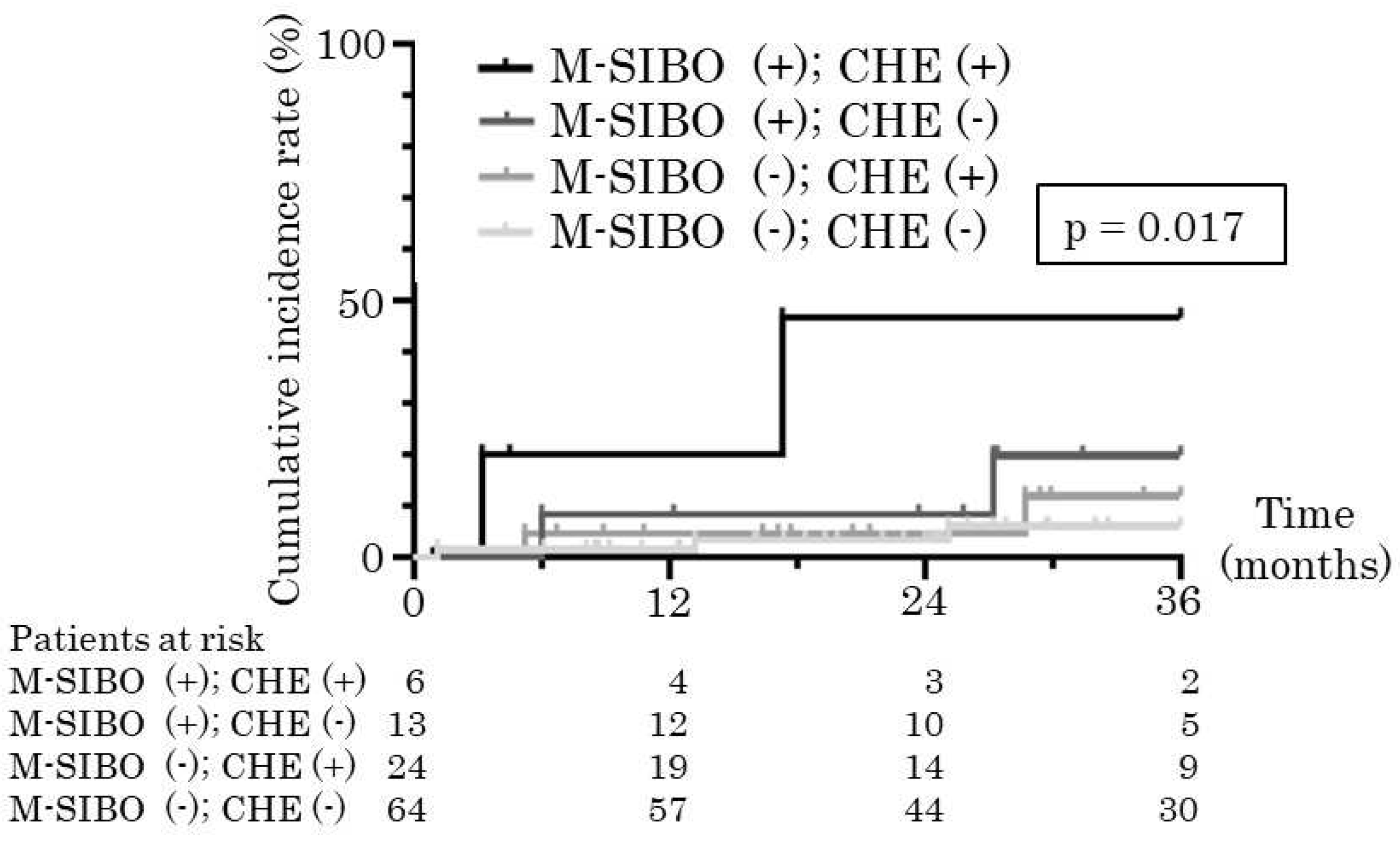

| Covert HE | 0.067 | 4.058 (0.908 – 18.142) | 0.038* | 5.008 (1.096 – 22.892) |

| SIBO | 0.015* | 7.610 (1.475 – 39.625) | ||

| Hydrogen producing SIBO | 0.131 | 3.553 (0.685 – 18.415) | ||

| Methane producing SIBO | 0.010* | 7.228 (1.614 – 32.361) | 0.006* | 8.597 (1.881 – 39.291) |

| HE, hepatic encephalopathy; PPI, proton pump inhibitor; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; UICC, Union for International Cancer Control; BCLC, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer; ALBI, Albumin-Bilirubin; mALBI, modified ALBI; HE, hepatic encephalopathy; SIBO, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. *: P value < 0.05. | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).