Submitted:

10 January 2025

Posted:

14 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Respiratory viruses, such as influenza virus, rhinoviruses, coronaviruses, and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), continue to impose a heavy global health burden. Despite existing vaccination programs, these infections remain leading causes of morbidity and mortality, especially among vulnerable populations like children, the elderly, and immunocompromised individuals. However, the current therapeutic options for respiratory viral infections are often limited to supportive care, underscoring the need for novel treatment strategies. Autophagy, particularly macroautophagy, has emerged as a fundamental cellular process in the host response to respiratory viral infections. This process not only supports cellular homeostasis by degrading damaged organelles and pathogens but also enables xenophagy, which selectively targets viral particles for degradation and enhances cellular defense. However, viruses have evolved mechanisms to manipulate the autophagy pathways, using them to evade immune detection and promote viral replication. This review examines the dual role of autophagy in viral manipulation and host defense, focusing on the complex interplay between respiratory viruses and autophagy-related pathways. By elucidating these mechanisms, we aim to highlight the therapeutic potential of targeting autophagy to enhance antiviral responses, offering promising directions for the development of effective treatments against respiratory viral infections.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

| Virus | Family | Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|

| Influenza A virus (IAV) | Orthomyxoviridae | M2 ion channel blocks autophagosome-lysosome fusion [38] |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Coronaviridae | ORF3a blocks autophagosome-lysosome fusion; Nsp6 limits autophagosome expansion [26] |

| Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) | Pneumoviridae | NS1 protein activates autophagy through BECN1 [39] |

| Parainfluenza Virus (PIV) | Paramyxoviridae | Phosphoprotein P activates autophagy [40] |

| Adenovirus | Adenoviridae | E1B-19K protein interacts with BECN1 to suppress autophagy [41] |

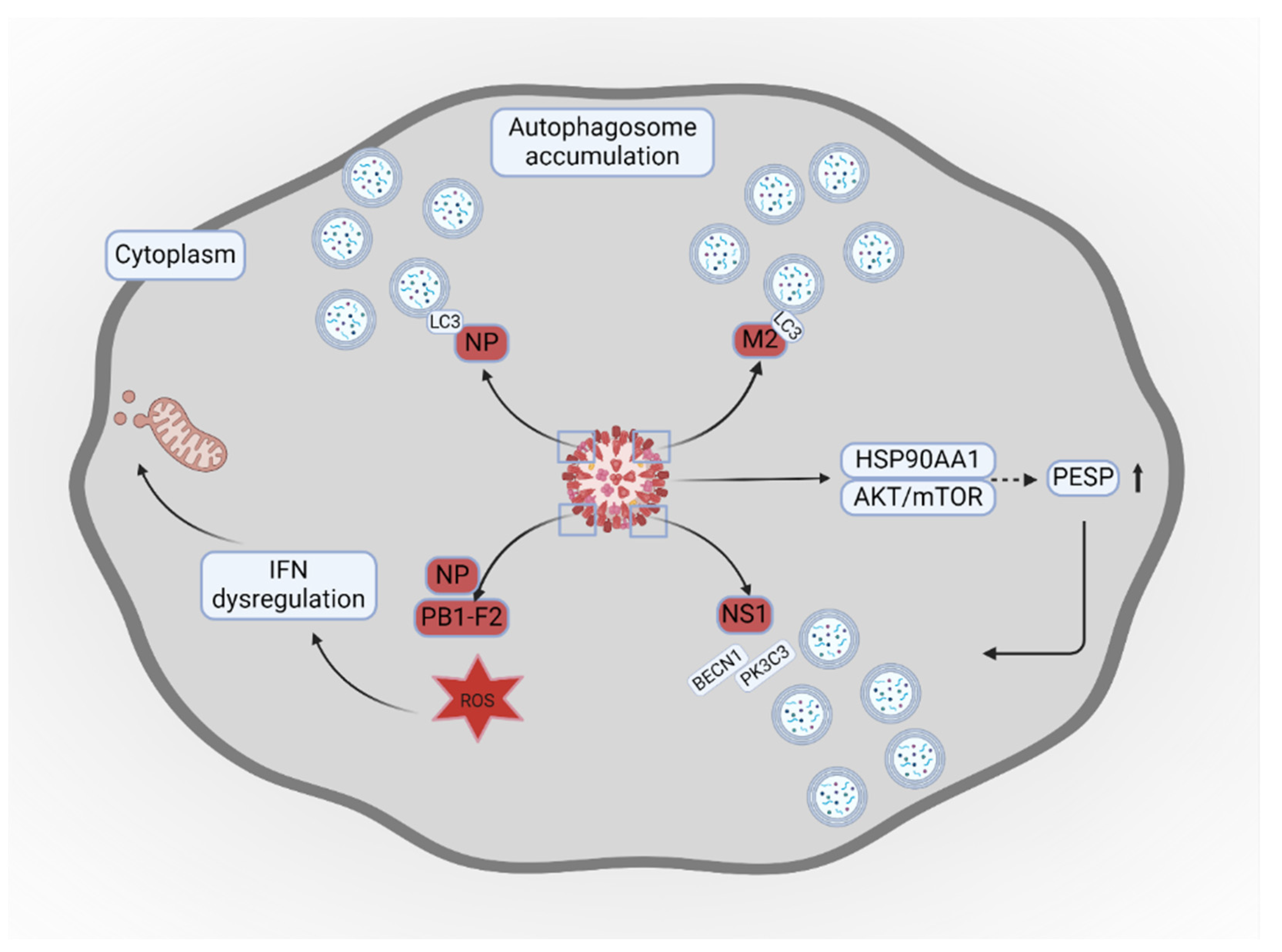

2. Influenza Virus and Autophagy

| Agent | Impact on influenza infection | Impact on autophagy | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gallic acid | Decreases viral load | Reduces accumulation of autophagosomes | [68] |

| Vitamin D3 | Induces cytoprotective effects | Enhances fusion of autophagosome and lysosome, thus decreasing viral replication | [69] |

| Baicalin | Improves viability of infected macrophages | Reduces expression of autophagy marker | [70] |

| Tanreqing | Inhibits influenza replication | Enhances fusion of autophagosome and lysosome | [53] |

| Huanglian-Ganjiang combination | Suppresses inflammatory responses | Enhances fusion of autophagosome and lysosome | [71] |

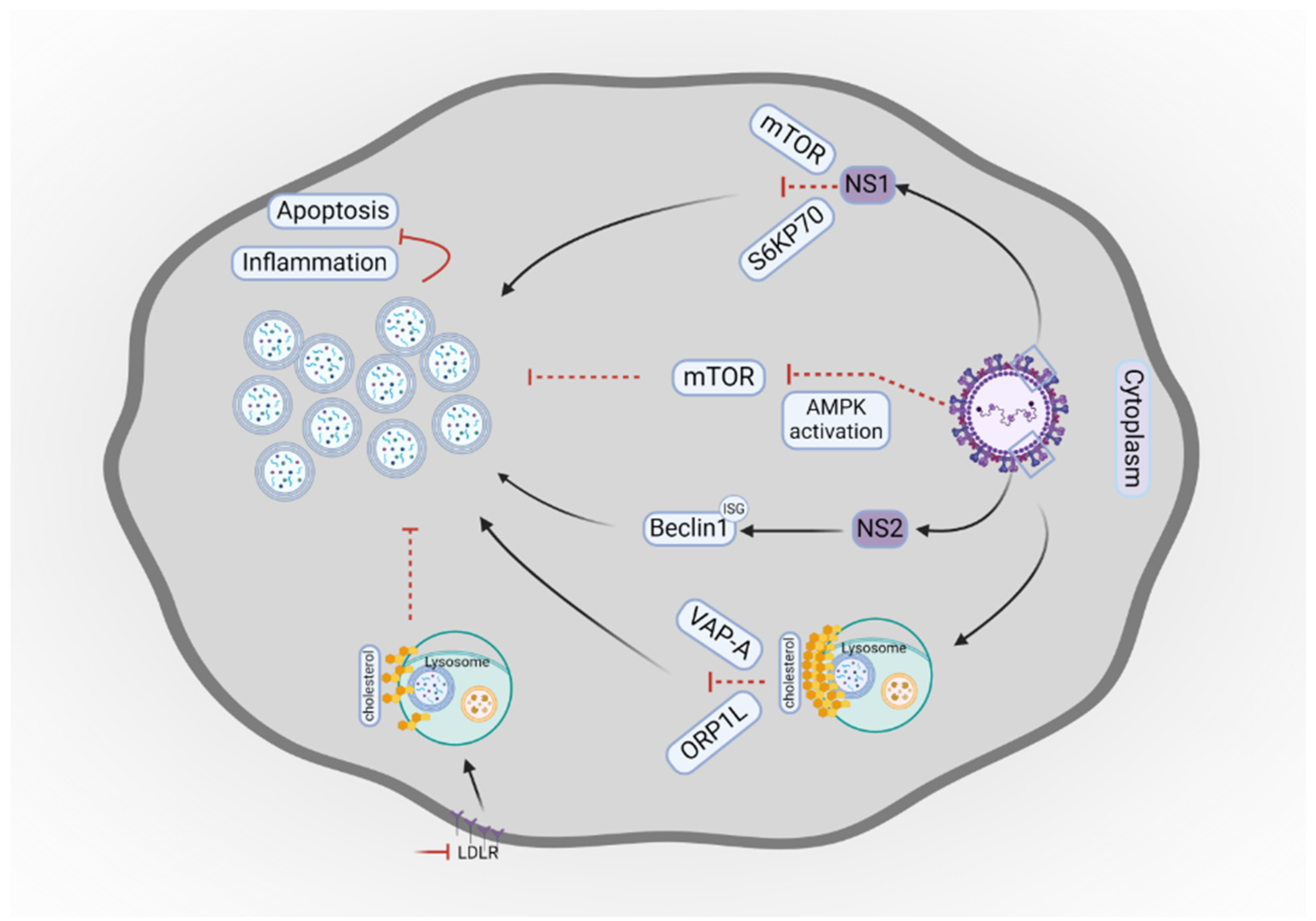

3. Respiratory Syncytial Virus and Autophagy

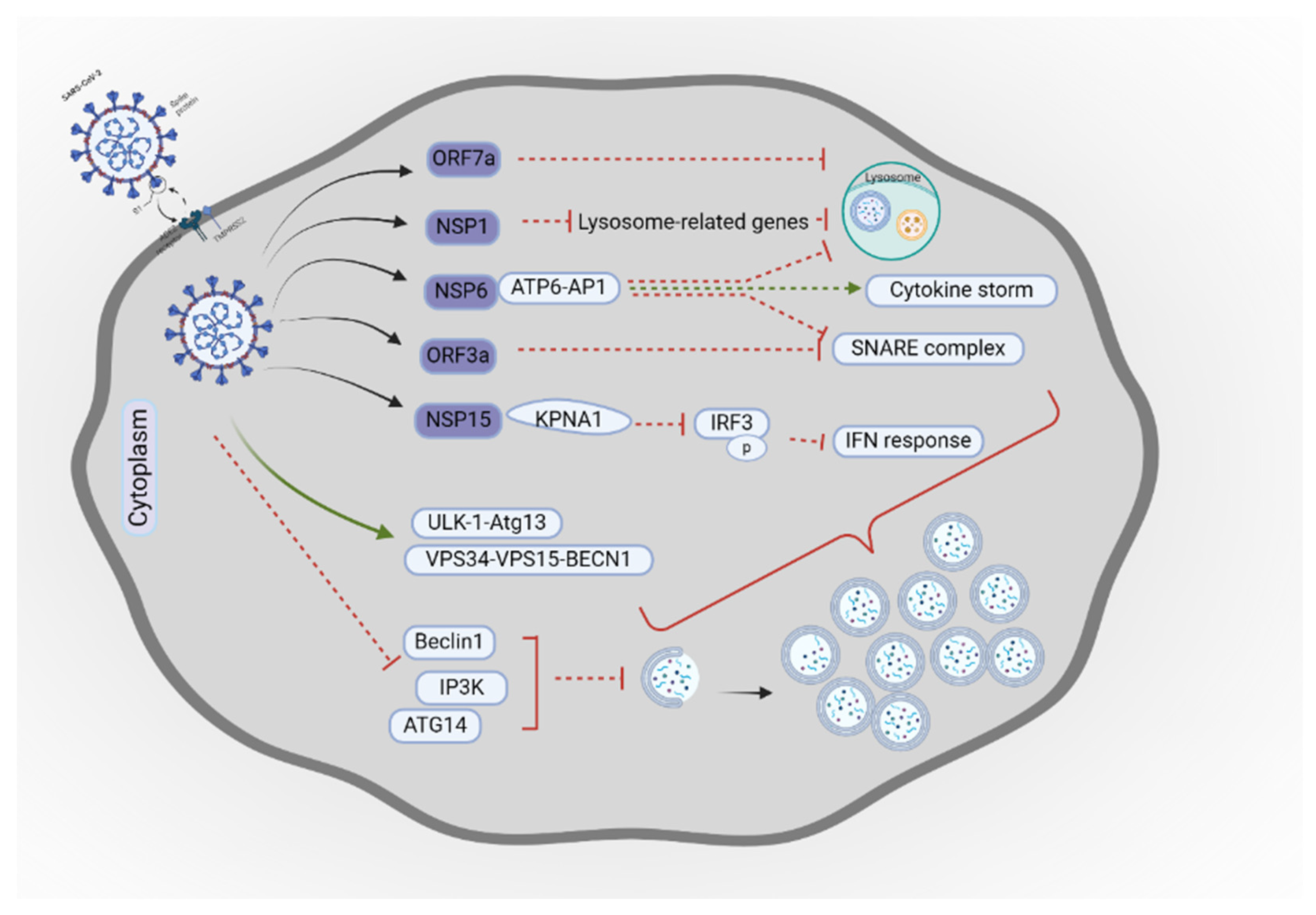

4. Coronaviruses and Autophagy

5. Human Parainfluenza Viruses and Autophagy

6. Adenovirus and Autophagy

7. Potential Therapeutic Approaches Using Autophagy

7.1. Current Clinical Trials Targeting Autophagy in Respiratory Virus Infections

7.2. Future Directions for Therapeutic Strategies

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACEIs | ACE inhibitors |

| AdV | Adenovirus |

| Ang II | angiotensin II |

| ARDS | acute respiratory distress syndrome |

| ATG | autophagy-related gene |

| BAG3 | Bcl-2 associated athanogene 3 |

| CARD | caspase recruitment domain |

| CMA | chaperone-mediated autophagy |

| E1A | early region 1A |

| F | fusion protein |

| Gal-8 | Galectin-8 |

| H | hemagglutinin-neuraminidase protein |

| HAdC-B7 | human adenovirus B7 |

| L | RNA polymerase |

| LC3 | microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 beta |

| LRTI | lower respiratory tract infection |

| M | matrix protein |

| MAVS | mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein |

| MERS-CoV | Middle-East respiratory syndrome coronavirus |

| N | nucleocapsid protein |

| NCOA4 | Nuclear receptor coactivator 4 |

| NSP | non-structural protein |

| P | phosphoprotein |

| PESP | PCBP1-AS1-encoded small protein |

| PVI | protein VI |

| QF | Qingfei |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| RSV | respiratory syncytial virus |

| HPIV | Human parainfluenza virus |

| IAV | influenza A virus |

| IFN | interferon |

| IKK | NF-kB kinase |

| ISG15 | interferon-stimulated gene 15 |

| KPNA1 | karyopherin α1 |

| LDLR | low-density lipoprotein receptor |

| RIG-I | retinoic acid-inducible gene I |

| RLRs | retinoic acid-inducible gene I-like receptors |

| SKP2 | S-phase kinase-associated protein 2 |

| TRAF | TNF receptor-associated factor |

| TUFM | translation elongation factor mitochondrial |

| VAMP8 | vesicle-associated membrane protein 8 |

| VPS34 | Class III phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase |

References

- Bender, R.G.; Sirota, S.B.; Swetschinski, L.R.; Dominguez, R.-M.V.; Novotney, A.; Wool, E.E.; et al. Global, regional, and national incidence and mortality burden of non-COVID-19 lower respiratory infections and aetiologies, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis from the global burden of disease study 2021. Lancet Infect Dis 2024, 24, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Shi, T.; Bont, L.J.; Chu, H.Y.; Zar, H.J.; et al. Global disease burden of and risk factors for acute lower respiratory infections caused by respiratory syncytial virus in preterm infants and young children in 2019: a systematic review and meta-analysis of aggregated and individual participant data. Lancet 2024, 403, 1241–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehrbod, P.; Ande, S.R.; Alizadeh, J.; Rahimizadeh, S.; Shariati, A.; Malek, H.; et al. The roles of apoptosis, autophagy and unfolded protein response in arbovirus, influenza virus, and HIV infections. Virulence 2019, 10, 376–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, T.; Denouel, A.; Tietjen, A.K.; Campbell, I.; Moran, E.; Li, X.; et al. Global disease burden estimates of respiratory syncytial virus–associated acute respiratory infection in older adults in 2015: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect Dis 2020, 222, S577–S583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cilloniz, C.; Luna, C.M.; Hurtado, J.C.; Marcos, M.Á.; Torres, A. Respiratory viruses: their importance and lessons learned from COVID-19. Eur Respir Rev 2022, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoar, S.; Musher, D.M. Etiology of community-acquired pneumonia in adults: a systematic review. Pneumonia 2020, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burk, M.; El-Kersh, K.; Saad, M.; Wiemken, T.; Ramirez, J.; Cavallazzi, R. Viral infection in community-acquired pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir Rev 2016, 25, 178–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.-N.; Zhang, Y.-F.; Xu, Q.; Qiu, Y.; Lu, Q.-B.; Wang, T.; et al. Infection and co-infection patterns of community-acquired pneumonia in patients of different ages in China from 2009 to 2020: a national surveillance study. Lancet Microbe 2023, 4, e330–e339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Doorn, H.R.; Yu, H. Viral Respiratory Infections, in Hunter's tropical medicine and emerging infectious diseases. 2020, Elsevier. p. 284-288.

- Chemaly, R.F.; Rathod, D.B.; Couch, R. Respiratory viruses. Principle Practice Cancer Infect Dis 2011;371-385.

- Chang, C.-C.; You, H.-L.; Huang, S.-T. Catechin inhibiting the H1N1 influenza virus associated with the regulation of autophagy. J Chin Med Assoc 2020, 83, 386–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, M.; Jeong, J.H.; Ju, S.; Lee, S.J.; Jeong, Y.Y.; Lee, J.D.; et al. Comparison of clinical features and outcomes between SARS-CoV-2 and non-SARS-CoV-2 respiratory viruses associated acute respiratory distress syndrome: retrospective analysis. J Clin Med 2022, 11, 2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatterjee, A.; Mavunda, K.; Krilov, L. Current state of respiratory syncytial virus disease and management. J Infect Dis Pharmacother 2021, 10, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, A.; Zhang, W.; Dong, X.; Liu, M.; Chen, H.; Tang, B. The battle for autophagy between host and influenza A virus. Virulence 2022, 13, 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdoli, A.; Alirezaei, M.; Mehrbod, P.; Forouzanfar, F. Autophagy: the multi-purpose bridge in viral infections and host cells. Rev Med Virol 2018, 28, e1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibzadeh, P.; Dastsooz, H.; Eshraghi, M.; Los, M.J.; Klionsky, D.J.; Ghavami, S. Autophagy: The Potential Link between SARS-CoV-2 and Cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shojaei, S.; Suresh, M.; Klionsky, D.J.; Labouta, H.I.; Ghavami, S. Autophagy and SARS-CoV-2 infection: Apossible smart targeting of the autophagy pathway. Virulence 2020, 11, 805–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.; Hu, Z.; Castro-Gonzalez, S. Bidirectional interplay between SARS-CoV-2 and autophagy. Mbio 2023, 14, e01020–01023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iranpour, M.; Moghadam, A.R.; Yazdi, M.; Ande, S.R.; Alizadeh, J.; Wiechec, E.; et al. Apoptosis, autophagy and unfolded protein response pathways in Arbovirus replication and pathogenesis. Expert Rev Mol Med 2016, 18, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Klionsky, D.J. An overview of the molecular mechanism of autophagy. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 2009;1-32.

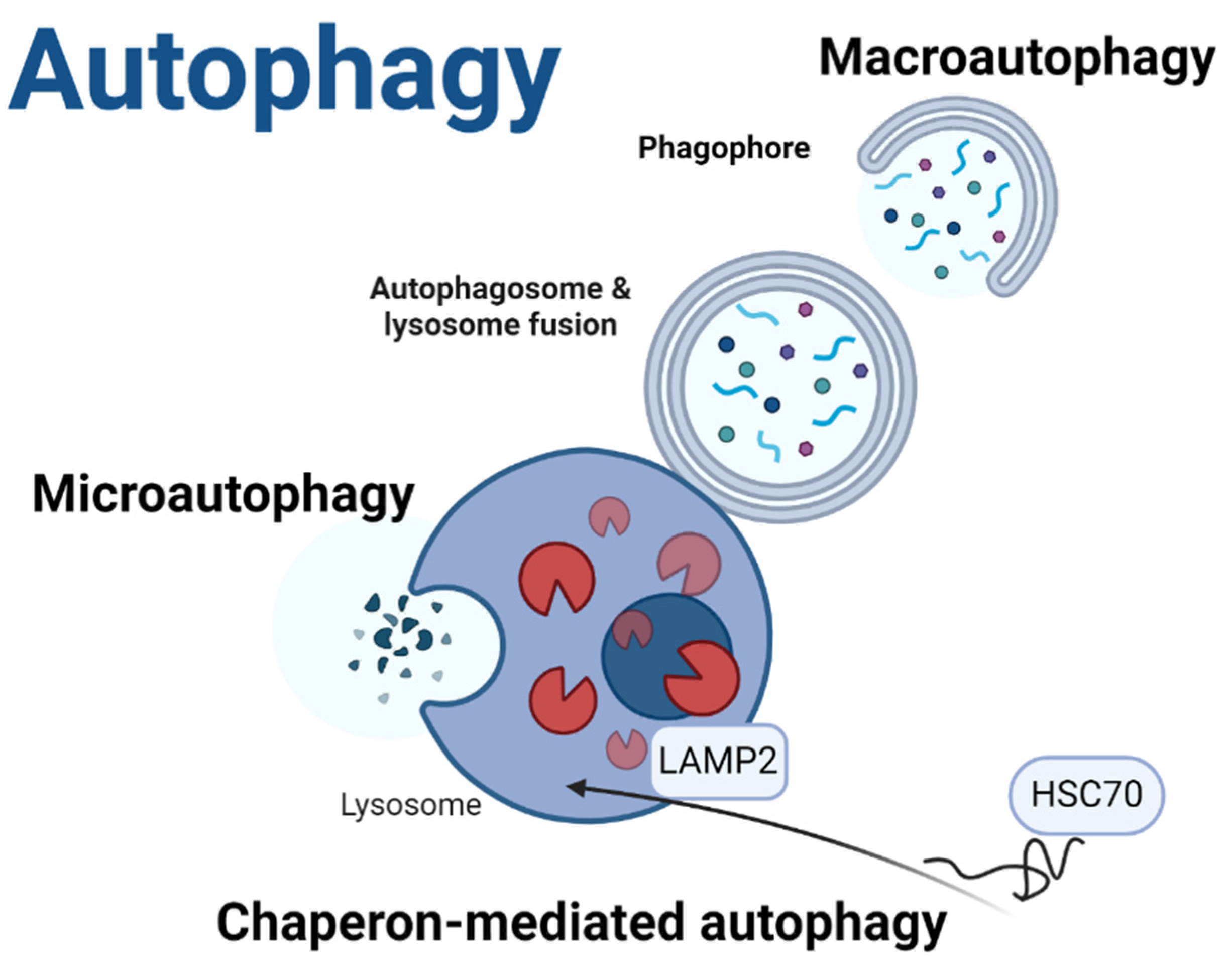

- Yamamoto, H.; Matsui, T. Molecular mechanisms of macroautophagy, microautophagy, and chaperone-mediated autophagy. J Nippon Med School 2024, 91, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behrooz, A.B.; Cordani, M.; Fiore, A.; Donadelli, M.; Gordon, J.W.; Klionsky, D.J.; et al. The obesity-autophagy-cancer axis: Mechanistic insights and therapeutic perspectives. Semin Cancer Biol 2024, 99, 24–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirmoradi, L.; Shojaei, S.; Ghavami, S.; Zarepour, A.; Zarrabi, A. Autophagy and Biomaterials: A Brief Overview of the Impact of Autophagy in Biomaterial Applications. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, J.; da Silva Rosa, S.C.; Weng, X.; Jacobs, J.; Lorzadeh, S.; Ravandi, A.; et al. Ceramides and ceramide synthases in cancer: Focus on apoptosis and autophagy. Eur J Cell Biol 2023, 102, 151337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alizadeh, J.; Kavoosi, M.; Singh, N.; Lorzadeh, S.; Ravandi, A.; Kidane, B.; et al. Regulation of Autophagy via Carbohydrate and Lipid Metabolism in Cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, T.; Hu, J.; Jin, S.; Wu, J.; Guan, X.; et al. Targeting selective autophagy as a therapeutic strategy for viral infectious diseases. Front Microbiol 2022, 13, 889835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajiahmadi, S.; Lorzadeh, S.; Iranpour, R.; Karima, S.; Rajabibazl, M.; Shahsavari, Z.; et al. Temozolomide, Simvastatin and Acetylshikonin Combination Induces Mitochondrial-Dependent Apoptosis in GBM Cells, Which Is Regulated by Autophagy. Biology (Basel) 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayat, M. Overview of autophagy, in Autophagy: Cancer, other pathologies, inflammation, immunity, infection, and aging. 2017, Elsevier. p. 1-122.

- Dalvand, A.; da Silva Rosa, S.C.; Ghavami, S.; Marzban, H. Potential role of TGFBeta and autophagy in early crebellum development. Biochem Biophys Rep 2022, 32, 101358. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y.; Galluzzi, L.; Zitvogel, L.; Kroemer, G. Autophagy and cellular immune responses. J Immunity 2013, 39, 211–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordani, M.; Strippoli, R.; Trionfetti, F.; Barzegar Behrooz, A.; Rumio, C.; Velasco, G.; et al. Immune checkpoints between epithelial-mesenchymal transition and autophagy: A conflicting triangle. Cancer Lett 2024, 585, 216661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, R.A.; Quinsay, M.N.; Orogo, A.M.; Giang, K.; Rikka, S.; Gustafsson, Å.B. Microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 (LC3) interacts with Bnip3 protein to selectively remove endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria via autophagy. J Biol Chem 2012, 287, 19094–19104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shpilka, T.; Weidberg, H.; Pietrokovski, S.; Elazar, Z. Atg8: an autophagy-related ubiquitin-like protein family. Genome Biol 2011, 12, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva Rosa, S.C.; Martens, M.D.; Field, J.T.; Nguyen, L.; Kereliuk, S.M.; Hai, Y.; et al. BNIP3L/Nix-induced mitochondrial fission, mitophagy, and impaired myocyte glucose uptake are abrogated by PRKA/PKA phosphorylation. Autophagy 2021, 17, 2257–2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adlimoghaddam, A.; Fayazbakhsh, F.; Mohammadi, M.; Babaei, Z.; Behrooz, A.B.; Tabasi, F.; et al. Sex and Region-Specific Disruption of Autophagy and Mitophagy in Alzheimer's Disease: Linking Cellular Dysfunction to Cognitive Decline. bioRxiv 2024.

- Reggio, A.; Buonomo, V.; Grumati, P. Eating the unknown: Xenophagy and ER-phagy are cytoprotective defenses against pathogens. Exp Cell Res 2020, 396, 112276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Bari, M.A.A.; Ito, Y.; Ahmed, S.; Radwan, N.; Ahmed, H.S.; Eid, N. Targeting autophagy with natural products as a potential therapeutic approach for cancer. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 9807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gannagé, M.; Dormann, D.; Albrecht, R.; Dengjel, J.; Torossi, T.; Rämer, P.C.; et al. Matrix protein 2 of influenza A virus blocks autophagosome fusion with lysosomes. Cell Host Microbe 2009, 6, 367–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiok, K.; Pokharel, S.M.; Mohanty, I.; Miller, L.G.; Gao, S.-J.; Haas, A.L.; et al. Human respiratory syncytial virus NS2 protein induces autophagy by modulating Beclin1 protein stabilization and ISGylation. MBio 2022, 13, e03528–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, B.; Zhang, G.; Yang, X.; Zhang, S.; Chen, L.; Yan, Q.; et al. Phosphoprotein of human parainfluenza virus type 3 blocks autophagosome-lysosome fusion to increase virus production. Cell Host Microbe 2014, 15, 564–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piya, S.; White, E.J.; Klein, S.R.; Jiang, H.; McDonnell, T.J.; Gomez-Manzano, C.; et al. The E1B19K oncoprotein complexes with Beclin 1 to regulate autophagy in adenovirus-infected cells. PloS one 2011, 6, e29467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delorme-Axford, E.; Klionsky, D.J.J.A. Highlights in the fight against COVID-19: does autophagy play a role in SARS-CoV-2 infection? Taylor & Francis: 2020; p. 2123-2127.

- Siri, M.; Dastghaib, S.; Zamani, M.; Rahmani-Kukia, N.; Geraylow, K.R.; Fakher, S.; et al. Autophagy, Unfolded Protein Response, and Neuropilin-1 Cross-Talk in SARS-CoV-2 Infection: What Can Be Learned from Other Coronaviruses. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeganeh, B.; Rezaei Moghadam, A.; Alizadeh, J.; Wiechec, E.; Alavian, S.M.; Hashemi, M.; et al. Hepatitis B and C virus-induced hepatitis: Apoptosis, autophagy, and unfolded protein response. World J Gastroenterol 2015, 21, 13225–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyeki, T.M.; Hui, D.S.; Zambon, M.; Wentworth, D.E.; Monto, A.S. Influenza. Lancet 2022, 400, 693–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Seasonal influenza 2022−2023. Annual Epidemiological Report for 2023 2023; Available from: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications- data/seasonal-influenza-annual-epidemiological-report-20222023.

- CDC. 2023-2024 U.S. Flu Season: Preliminary in-season burden estimates. 2024 [cited 2024 21 July]; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/burden/preliminary-in-season-estimates.htm.

- Pumarola, T.; Diez-Domingo, J.; Martinon-Torres, F.; Redondo Marguello, E.; de Lejarazu Leonardo, R.O.; Carmo, M.; et al. Excess hospitalizations and mortality associated with seasonal influenza in Spain, 2008-2018. BMC Infect Dis 2023, 23, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javanian, M.; Barary, M.; Ghebrehewet, S.; Koppolu, V.; Vasigala, V.; Ebrahimpour, S. A brief review of influenza virus infection. J Med Virol 2021, 93, 4638–4646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouranos, K.; Vassilopoulos, S.; Vassilopoulos, A.; Shehadeh, F.; Mylonakis, E. Cumulative incidence and mortality rate of cardiovascular complications due to laboratory-confirmed influenza virus infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Med Virol 2024, 34, e2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Zhu, Y.; Zhao, J.; Ren, C.; Li, P.; Chen, H.; et al. Autophagy promotes replication of influenza A Virus in vitro. J Virol 2019, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, C.; Ren, H.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; et al. A/(H1N1) pdm09 NS1 promotes viral replication by enhancing autophagy through hijacking the IAV negative regulatory factor LRPPRC. Autophagy 2023, 19, 1533–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, R.; Liu, H.; Su, R.; Mao, Q.; Zhao, M.; Zhang, H.; et al. Tanreqing injection inhibits influenza virus replication by promoting the fusion of autophagosomes with lysosomes: An integrated pharmacological study. J Ethnopharmacol 2024, 331, 118159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Zheng, T.; Lin, L.; Zhang, Y.; Peng, X.; Yan, Y.; et al. Influenza A virus induces autophagy by its hemagglutinin binding to cell surface heat shock protein 90AA1. Front Microbiol 2020, 11, 566348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi, X.; Huang, G.; Wang, L.; Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; Yin, Z.; et al. A small protein encoded by PCBP1-AS1 is identified as a key regulator of influenza virus replication via enhancing autophagy. PLoS Pathog 2024, 20, e1012461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.H.; Zhang, H.L.; Li, P.Y.; Li, C.H.; Gao, J.P.; Li, J.; et al. Autophagy is involved in the replication of H9N2 influenza virus via the regulation of oxidative stress in alveolar epithelial cells. Virol J 2021, 18, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Juarbe, N.; Riegler, A.N.; Jureka, A.S.; Gilley, R.P.; Brand, J.D.; Trombley, J.E.; et al. Influenza-induced oxidative stress sensitizes lung cells to bacterial-toxin-mediated necroptosis. Cell Rep 2020, 32, 108062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalskov, L.; Gad, H.H.; Hartmann, R. Viral recognition and the antiviral interferon response. EMBO J 2023, 42, e112907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Zhu, Y.; Ren, C.; Yang, S.; Tian, S.; Chen, H.; et al. Influenza A virus protein PB1-F2 impairs innate immunity by inducing mitophagy. Autophagy 2021, 17, 496–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Xu, S.; Liu, M.; Wei, Y.; Wang, Q.; Shen, W.; et al. The nucleoprotein of influenza A virus inhibits the innate immune response by inducing mitophagy. Autophagy 2023, 19, 1916–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, S.; Han, L.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, B.; Wang, Q.; Liu, J.; et al. MicroRNA-200c-targeted contactin 1 facilitates the replication of influenza A virus by accelerating the degradation of MAVS. PLoS Pathog 2022, 18, e1010299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, C.; Xu, W.; Ai, X.; Zhu, Y.; Geng, P.; Niu, Y.; et al. Autophagy and exosome coordinately enhance macrophage M1 polarization and recruitment in influenza A virus infection. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 722053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, S.L.; Dunning, J.; Kok, W.L.; Benam, K.H.; Benlahrech, A.; Repapi, E.; et al. M1-like monocytes are a major immunological determinant of severity in previously healthy adults with life-threatening influenza. JCI Insight 2017, 2, e91868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, S.; Drexler, I. Targeting autophagy in innate immune cells: Angel or demon during infection and vaccination? Front Immunol 2020, 11, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zang, F.; Chen, Y.; Lin, Z.; Cai, Z.; Yu, L.; Xu, F.; et al. Autophagy is involved in regulating the immune response of dendritic cells to influenza A (H1N1) pdm09 infection. Immunology 2016, 148, 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puleston, D.J.; Simon, A.K. Autophagy in the immune system. Immunology 2014, 141, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Mok, B.W.; Deng, S.; Liu, H.; Wang, P.; Song, W.; et al. Mammalian cells use the autophagy process to restrict avian influenza virus replication. Cell Rep 2021, 35, 109213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.C.; You, H.L.; Su, H.J.; Hung, I.L.; Kao, C.W.; Huang, S.T. Anti-influenza A (H1N1) virus effect of gallic acid through inhibition of virulent protein production and association with autophagy. Food Sci Nutr 2024, 12, 1605–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godbole, N.M.; Sinha, R.A.; Tiwari, S.; Pawar, S.D.; Dhole, T.N. Analysis of influenza virus-induced perturbation in autophagic flux and its modulation during Vitamin D3 mediated anti-apoptotic signaling. Virus Res 2020, 282, 197936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Li, J.; Shan, C.; Song, X.; Yang, J.; Xu, H.; et al. Baicalin reduced injury of and autophagy-related gene expression in RAW264. 7 cells infected with H6N6 avian influenza virus. Heliyon 2024, 10, e32645. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Yu, C.L.; Yan, Y.L.; Zhang, F.L.; Chen, J.; Hu, Z.Y.; et al. Inhibitory Effects and Related Molecular Mechanisms of Huanglian-Ganjiang Combination Against H1N1 Influenza Virus. Rev Bras Farmacogn 2023, 33, 514–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Chi, X.; Wang, S.; Qi, B.; Yu, X.; Chen, J.L. The regulation of autophagy by influenza A virus. Biomed Res Int 2014, 2014, 498083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.G.; Lee, H.; Kim, Y.S.; Hwang, Y.H.; Oh, Y.C.; Lee, B.; et al. Aloe vera and its components inhibit influenza A virus-induced autophagy and replication. Am J Chin Med 2019, 47, 1307–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tripathi, S.; Batra, J.; Cao, W.; Sharma, K.; Patel, J.R.; Ranjan, P.; et al. Influenza A virus nucleoprotein induces apoptosis in human airway epithelial cells: implications of a novel interaction between nucleoprotein and host protein Clusterin. Cell Death Dis 2013, 4, e562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazel-Sanchez, B.; Iwaszkiewicz, J.; Bonifacio, J.P.P.; Silva, F.; Niu, C.; Strohmeier, S.; et al. Influenza A viruses balance ER stress with host protein synthesis shutoff. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2021, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeganeh, B.; Ghavami, S.; Rahim, M.N.; Klonisch, T.; Halayko, A.J.; Coombs, K.M. Autophagy activation is required for influenza A virus-induced apoptosis and replication. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res 2018, 1865, 364–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Bowman, J.W.; Jung, J.U. Autophagy during viral infection - a double-edged sword. Nat Rev Microbiol 2018, 16, 341–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bächi, T.; Howe, C. Morphogenesis and ultrastructure of respiratory syncytial virus. J Virol 1973, 12, 1173–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourgeois, C.; Bour, J.B.; Lidholt, K.; Gauthray, C.; Pothier, P. Heparin-like structures on respiratory syncytial virus are involved in its infectivity in vitro. J Virol 1998, 72, 7221–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazur, N.I.; Caballero, M.T.; Nunes, M.C. Severe respiratory syncytial virus infection in children: burden, management, and emerging therapies. Lancet 2024, 404, 1143–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohapatra, S.S.; Boyapalle, S. Epidemiologic, experimental, and clinical links between respiratory syncytial virus infection and asthma. Clin Microbiol Rev 2008, 21, 495–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanken, M.O.; Rovers, M.M.; Molenaar, J.M.; Winkler-Seinstra, P.L.; Meijer, A.; Kimpen, J.L.; et al. Respiratory syncytial virus and recurrent wheeze in healthy preterm infants. N Engl J Med 2013, 368, 1791–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, B.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, M. Inhibition of autophagy promotes human RSV NS1-induced inflammation and apoptosis. Exp Ther Med 2021, 22, 1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Wu, B.; Wang, Y.; He, H.; Lin, Z.; Tan, J.; et al. Particulate matter 2. 5 induces autophagy via inhibition of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin kinase signaling pathway in human bronchial epithelial cells. Mol Med Rep 2015, 12, 1914–1922. [Google Scholar]

- Azman, A.F.; Chia, S.L.; Sekawi, Z.; Yusoff, K.; Ismail, S. Inhibition of autophagy does not affect innate cytokine production in human lung epithelial cells during respiratory syncytial virus infection. Viral Immunol 2021, 34, 421–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Yang, H.; Kong, X.; Mohapatra, S.; San Juan-Vergara, H.; Hellermann, G.; et al. Inhibition of respiratory syncytial virus infection with intranasal siRNA nanoparticles targeting the viral NS1 gene. Nat Med 2005, 11, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiok, K.; Pokharel, S.M.; Mohanty, I.; Miller, L.G.; Gao, S.J.; Haas, A.L.; et al. Human respiratory syncytial virus NS2 protein induces autophagy by modulating beclin1 protein stabilization and ISGylation. MBio 2022, 13, e0352821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, L.; Wang, J.; Zou, Y.; Zeng, H.; Cheng, W.; Jing, X. Qingfei oral liquid inhibited autophagy to alleviate inflammation via mTOR signaling pathway in RSV-infected asthmatic mice. Biomed Pharmacother 2021, 138, 111449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; An, L.; Chen, H.; Feng, L.; Lu, M.; Liu, Y.; et al. Integrated network pharmacology and lipidomics to reveal the inhibitory effect of Qingfei oral liquid on excessive autophagy in RSV-induced lung inflammation. Front Pharmacol 2021, 12, 777689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Zhang, J.; Xu, W.; Chen, J.; Tang, Y.; Xiong, S.; et al. Cholesterol-rich lysosomes induced by respiratory syncytial virus promote viral replication by blocking autophagy flux. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 6311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Lang, W.; Liu, X.; Bai, J.; Jia, Q.; Shi, Q. Procyanidin A1 alleviates DSS-induced ulcerative colitis via regulating AMPK/mTOR/p70S6K-mediated autophagy. J Physiol Biochem 2022, 78, 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, D.; Tao, W.; Zhang, F.; Shen, W.; Tan, J.; Li, L.; et al. Trifolirhizin induces autophagy-dependent apoptosis in colon cancer via AMPK/mTOR signaling. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2020, 5, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Wu, W.; Xiong, Z.; Yu, X.; Ye, Z.; Wu, Z. Targeting autophagy drug discovery: Targets, indications and development trends. Eur J Med Chem 2024, 267, 116117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wildenbeest, J.G.; Lowe, D.M.; Standing, J.F.; Butler, C.C. Respiratory syncytial virus infections in adults: a narrative review. Lancet Respir Med 2024, 12, 822–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, E.; Goswami, J.; Baqui, A.H.; Doreski, P.A.; Perez-Marc, G.; Zaman, K.; et al. Efficacy and safety of an mRNA-based RSV preF vaccine in older adults. N Engl J Med 2023, 389, 2233–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaleh, G.; Panse, I.; Swadling, L.; Zhang, H.; Richter, F.C.; Meyer, A.; et al. Autophagy in T cells from aged donors is maintained by spermidine and correlates with function and vaccine responses. Elife 2020, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Merkley, S.D.; Chock, C.J.; Yang, X.O.; Harris, J.; Castillo, E.F. Modulating T cell responses via autophagy: The intrinsic influence controlling the function of both antigen-presenting cells and T cells. Front Immunol 2018, 9, 2914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faramarzi, A.; Norouzi, S.; Dehdarirad, H.; Aghlmand, S.; Yusefzadeh, H.; Javan-Noughabi, J. The global economic burden of COVID-19 disease: a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst Rev 2024, 13, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grellet, E.; Goulet, A.; Imbert, I. Replication of the coronavirus genome: A paradox among positive-strand RNA viruses. J Biol Chem 2022, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zappulli, V.; Ferro, S.; Bonsembiante, F.; Brocca, G.; Calore, A.; Cavicchioli, L.; et al. Pathology of coronavirus infections: A review of lesions in animals in the one-health perspective. Animals 2020, 10, 2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, X.; Zhou, G.-Z.; Zhang, Y.; Peng, L.-H.; Zou, L.-P.; Yang, Y.-S. Coronaviruses and gastrointestinal diseases. Mil Med Res 2020, 7, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Xu, X.; Chen, Z.; Duan, J.; Hashimoto, K.; Yang, L.; et al. Nervous system involvement after infection with COVID-19 and other coronaviruses. Brain Behav Imun 2020, 87, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clausen, T.M.; Sandoval, D.R.; Spliid, C.B.; Pihl, J.; Perrett, H.R.; Painter, C.D.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection depends on cellular heparan sulfate and ACE2. Cell 2020, 183, 1043–1057 e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourgonje, A.R.; Abdulle, A.E.; Timens, W.; Hillebrands, J.L.; Navis, G.J.; Gordijn, S.J.; et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), SARS-CoV-2 and the pathophysiology of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). J Pathol 2020, 251, 228–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mokhtari, T.; Hassani, F.; Ghaffari, N.; Ebrahimi, B.; Yarahmadi, A.; Hassanzadeh, G. COVID-19 and multiorgan failure: A narrative review on potential mechanisms. J Mol Histol 2020, 51, 613–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Cao, Y.; Zeng, Z.; Liang, M.; Xue, Y.; Xi, C.; et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2/angiotensin-(1–7)/Mas axis prevents lipopolysaccharide–induced apoptosis of pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells by inhibiting JNK/NF–κB pathways. Sci Rep 2015, 5, 8209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, M.; Kleine-Weber, H.; Schroeder, S.; Krüger, N.; Herrler, T.; Erichsen, S.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell 2020, 181, 271–280.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gassen, N.C.; Papies, J.; Bajaj, T.; Emanuel, J.; Dethloff, F.; Chua, R.L.; et al. SARS-CoV-2-mediated dysregulation of metabolism and autophagy uncovers host-targeting antivirals. Nat commun 2021, 12, 3818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghdoust, M.; Aligolighasemabadi, F.; Dehesh, T.; Taefehshokr, N.; Sadeghdoust, A.; Kotfis, K.; et al. The effects of statins on respiratory symptoms and pulmonary fibrosis in COVID-19 patients with diabetes mellitus: a longitudinal multicenter study. Arch Immunol Ther Exp 2023, 71, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, S.; Zhang, Z.-m; Shen, Z.-l; Gao, K.; Chang, L.; Guo, Y.; et al. Atorvastatin activates autophagy and promotes neurological function recovery after spinal cord injury. Neural Regen Res 2016, 11, 977–982. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Han, F.; Xiao, Q.Q.; Peng, S.; Che, X.Y.; Jiang, L.S.; Shao, Q.; et al. Atorvastatin ameliorates LPS-induced inflammatory response by autophagy via AKT/mTOR signaling pathway. J Cell Biochem 2018, 119, 1604–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peymani, P.; Dehesh, T.; Aligolighasemabadi, F.; Sadeghdoust, M.; Kotfis, K.; Ahmadi, M.; et al. Statins in patients with COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study in Iranian COVID-19 patients. Transl Med Commun 2021, 6, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yang, X.; Hu, G.; et al. ORF3a mediated-incomplete autophagy facilitates SARS-CoV-2 replication. bioRxiv 2020;2020.11. 12.380709.

- Hayn, M.; Hirschenberger, M.; Koepke, L.; Nchioua, R.; Straub, J.H.; Klute, S.; et al. Systematic functional analysis of SARS-CoV-2 proteins uncovers viral innate immune antagonists and remaining vulnerabilities. Cell Rep 2021, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, G.; Zhao, H.; Li, Y.; Ji, M.; Chen, Y.; Shi, Y.; et al. ORF3a of the COVID-19 virus SARS-CoV-2 blocks HOPS complex-mediated assembly of the SNARE complex required for autolysosome formation. Dev Cell 2021, 56, 427–442 e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koepke, L.; Hirschenberger, M.; Hayn, M.; Kirchhoff, F.; Sparrer, K.M. Manipulation of autophagy by SARS-CoV-2 proteins. Autophagy 2021, 17, 2659–2661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Liu, Y.; Huang, Z.; Xu, W.; Hu, W.; Yi, L.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 non-structural protein 6 triggers NLRP3-dependent pyroptosis by targeting ATP6AP1. Cell Death Differ 2022, 29, 1240–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottam, E.M.; Whelband, M.C.; Wileman, T. Coronavirus NSP6 restricts autophagosome expansion. Autophagy 2014, 10, 1426–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, C.; Zhuang, X.; Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Lu, J.; et al. Inhibition of autophagy suppresses SARS-CoV-2 replication and ameliorates pneumonia in hACE2 transgenic mice and xenografted human lung tissues. J Virol 2021, 95, 10.1128/jvi. 01537–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Javed, R.; Mudd, M.; Pallikkuth, S.; Lidke, K.A.; Jain, A.; et al. Mammalian hybrid pre-autophagosomal structure HyPAS generates autophagosomes. Cell 2021, 184, 5950–5969 e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Y.; Pan, Z.; Wang, Z.; Lei, Z.; Yang, S.; Zhao, H.; et al. MERS-CoV nsp1 regulates autophagic flux via mTOR signalling and dysfunctional lysosomes. Emerg Microbes Infect 2022, 11, 2529–2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Z.; Lu, K.; Mao, B.; Liu, S.; Trilling, M.; Huang, A.; et al. The interplay between emerging human coronavirus infections and autophagy. Emerg Microbes Infect 2021, 10, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gassen, N.C.; Niemeyer, D.; Muth, D.; Corman, V.M.; Martinelli, S.; Gassen, A.; et al. SKP2 attenuates autophagy through Beclin1-ubiquitination and its inhibition reduces MERS-Coronavirus infection. Nat commun 2019, 10, 5770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Z.; Moten, A.; Peng, D.; Hsu, C.-C.; Pan, B.-S.; Manne, R.; et al. The Skp2 pathway: a critical target for cancer therapy. in Seminars in Cancer Biology. 2020. Elsevier.

- Liu, J.; Peng, Y.; Zhang, J.; Long, J.; Liu, J.; Wei, W. Targeting SCF E3 ligases for cancer therapies. Adv Exp Med Biol 2020;123-146.

- Pereira, G. J. D. S. , Leao, A. H. F. F., Erustes, A. G., Morais, I. B. D. M., Vrechi, T. A. D. M., Zamarioli, L. D. S.; et al. Pharmacological modulators of autophagy as a potential strategy for the treatment of COVID-19. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 4067. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Cao, R.; Xu, M.; Wang, X.; Zhang, H.; Hu, H.; et al. Hydroxychloroquine, a less toxic derivative of chloroquine, is effective in inhibiting SARS-CoV-2 infection in vitro. Cell Discov 2020, 6, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreani, J.; Le Bideau, M.; Duflot, I.; Jardot, P.; Rolland, C.; Boxberger, M.; et al. In vitro testing of combined hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin on SARS-CoV-2 shows synergistic effect. Microb patog 2020, 145, 104228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautret, P.; Lagier, J.-C.; Parola, P.; Meddeb, L.; Mailhe, M.; Doudier, B.; et al. Hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin as a treatment of COVID-19: results of an open-label non-randomized clinical trial. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2020, 56, 105949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, M.; Mösbauer, K.; Hofmann-Winkler, H.; Kaul, A.; Kleine-Weber, H.; Krüger, N.; et al. Chloroquine does not inhibit infection of human lung cells with SARS-CoV-2. Nature 2020, 585, 588–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maity, S.; Saha, A. Therapeutic potential of exploiting autophagy cascade against coronavirus infection. Front Microbiol 2021, 12, 675419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, C.K.; Seong, M.W.; Choi, S.J.; Kim, T.S.; Choe, P.G.; Song, S.H.; et al. In vitro activity of lopinavir/ritonavir and hydroxychloroquine against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 at concentrations achievable by usual doses. Korean J Intern Med 2020, 35, 782–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nutho, B.; Mahalapbutr, P.; Hengphasatporn, K.; Pattaranggoon, N.C.; Simanon, N.; Shigeta, Y.; et al. Why are lopinavir and ritonavir effective against the newly emerged coronavirus 2019? Atomistic insights into the inhibitory mechanisms. Biochemistry 2020, 59, 1769–1779. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Husain, A.; Byrareddy, S.N. Rapamycin as a potential repurpose drug candidate for the treatment of COVID-19. Chem Biol Interact 2020, 331, 109282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kindrachuk, J.; Ork, B.; Mazur, S.; Holbrook, M.R.; Frieman, M.B.; Traynor, D.; et al. Antiviral potential of ERK/MAPK and PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling modulation for Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection as identified by temporal kinome analysis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015, 59, 1088–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shetty, R.M.; Namachivayam, A. Evidence for chloroquine/hydroxychloroquine in the treatment of COVID-19. Indian J Crit Care Med 2021, 25, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coombs, K.; Mann, E.; Edwards, J.; Brown, D.T. Effects of chloroquine and cytochalasin B on the infection of cells by Sindbis virus and vesicular stomatitis virus. J Virol 1981, 37, 1060–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poschet, J.; Perkett, E.; Timmins, G.; Deretic, V. Azithromycin and ciprofloxacin have a chloroquine-like effect on respiratory epithelial cells. bioRxiv 2020. Preprint 2020.

- Cao, R.; Hu, H.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Xu, M.; Liu, J.; et al. Anti-SARS-CoV-2 potential of artemisinins in vitro. ACS Infect Dis 2020, 6, 2524–2531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehailia, M.; Chemat, S. Antimalarial-agent artemisinin and derivatives portray more potent binding to Lys353 and Lys31-binding hotspots of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein than hydroxychloroquine: potential repurposing of artenimol for COVID-19. J Biomol Struct Dyn 2021, 39, 6184–6194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uzun, T.; Toptas, O. Artesunate: could be an alternative drug to chloroquine in COVID-19 treatment? Chin Med 2020, 15, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coleman, C.M.; Sisk, J.M.; Mingo, R.M.; Nelson, E.A.; White, J.M.; Frieman, M.B. Abelson kinase inhibitors are potent inhibitors of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus and middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus fusion. J Virol 2016, 90, 8924–8933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, F.; Pan, T.; Huang, F.; Ying, R.; Liu, J.; Fan, H.; et al. Glycopeptide antibiotic teicoplanin inhibits cell entry of SARS-CoV-2 by suppressing the proteolytic activity of cathepsin L. Front Microbiol 2021, 13, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, S.A.; Devaux, C.; Colson, P.; Raoult, D.; Rolain, J.-M. Teicoplanin: an alternative drug for the treatment of COVID-19? 2020, Elsevier. p. 105944. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossignol, J.-F. Nitazoxanide, a new drug candidate for the treatment of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J Infect Public Heal 2016, 9, 227–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dang, W.; Xu, L.; Ma, B.; Chen, S.; Yin, Y.; Chang, K.-O.; et al. Nitazoxanide inhibits human norovirus replication and synergizes with ribavirin by activation of cellular antiviral response. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2018, 62, 10.1128/aac. 00707–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spriggs, M.K.; Collins, P.L. Human parainfluenza virus type 3: messenger RNAs, polypeptide coding assignments, intergenic sequences, and genetic map. J Virol 1986, 59, 646–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Branche, A.R.; Falsey, A.R. Parainfluenza virus infection. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2016, 37, 538–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farahmand, M.; Shatizadeh Malekshahi, S.; Jabbari, M.R.; Shayestehpour, M. The landscape of extrapulmonary manifestations of human parainfluenza viruses: A systematic narrative review. Microbiol Immunol 2021, 65, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, Y.E.; Park, J.Y.; Lee, M.K.; Lim, I.S. Characteristics of human parainfluenza virus type 4 infection in hospitalized children in Korea. Pediatr Int 2020, 62, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fathima, S.; Simmonds, K.; Invik, J.; Scott, A.N.; Drews, S. Use of laboratory and administrative data to understand the potential impact of human parainfluenza virus 4 on cases of bronchiolitis, croup, and pneumonia in Alberta, Canada. BMC Infect Dis 2016, 16, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abedi, G.R.; Prill, M.M.; Langley, G.E.; Wikswo, M.E.; Weinberg, G.A.; Curns, A.T.; et al. Estimates of parainfluenza virus-associated hospitalizations and cost among children aged less than 5 years in the United States, 1998-2010. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc 2016, 5, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, J.; Zhang, J.; Si, X.; Gao, G.; Mao, I.; McManus, B.M.; et al. Autophagosome supports coxsackievirus B3 replication in host cells. J Virol 2008, 82, 9143–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, B.; Zhang, G.; Yang, X.; Zhang, S.; Chen, L.; Yan, Q.; et al. Phosphoprotein of human parainfluenza virus type 3 blocks autophagosome-lysosome fusion to increase virus production. Cell Host Microbe 2014, 15, 564–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Q.; Gao, P.; Arzberger, T.; Höllerhage, M.; Herms, J.; Höglinger, G.; et al. Alpha-Synuclein defects autophagy by impairing SNAP29-mediated autophagosome-lysosome fusion. Cell Death Dis 2021, 12, 854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itakura, E.; Kishi-Itakura, C.; Mizushima, N. The hairpin-type tail-anchored SNARE syntaxin 17 targets to autophagosomes for fusion with endosomes/lysosomes. Cell 2012, 151, 1256–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrabaud, E.; De Muynck, S.; Asselah, T. Activation of unfolded protein response and autophagy during HCV infection modulates innate immune response. J Hepatol 2011, 55, 1150–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dreux, M.; Gastaminza, P.; Wieland, S.F.; Chisari, F.V. The autophagy machinery is required to initiate hepatitis C virus replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009, 106, 14046–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berryman, S.; Brooks, E.; Burman, A.; Hawes, P.; Roberts, R.; Netherton, C.; et al. Foot-and-mouth disease virus induces autophagosomes during cell entry via a class III phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-independent pathway. J Virol 2012, 86, 12940–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehwinkel, J.; Gack, M.U. RIG-I-like receptors: their regulation and roles in RNA sensing. Nat Rev Immunol 2020, 20, 537–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onomoto, K.; Onoguchi, K.; Yoneyama, M. Regulation of RIG-I-like receptor-mediated signaling: interaction between host and viral factors. Cell Mol Immunol 2021, 18, 539–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwasaki, M.; Takeda, M.; Shirogane, Y.; Nakatsu, Y.; Nakamura, T.; Yanagi, Y. The matrix protein of measles virus regulates viral RNA synthesis and assembly by interacting with the nucleocapsid protein. J Virol 2009, 83, 10374–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, X.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, K.; Lu, N.; He, Y.; Liu, J.; et al. Identification of the functional domain of HPIV3 matrix protein interacting with nucleocapsid protein. Biomed Res Int 2020, 2020, 2616172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, B.; Zhang, L.; Li, Z.; Zhong, Y.; Tang, Q.; Qin, Y.; et al. The matrix protein of human parainfluenza virus type 3 induces mitophagy that suppresses interferon responses. Cell Host Microbe 2017, 21, 538–547e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNab, F.; Mayer-Barber, K.; Sher, A.; Wack, A.; O'Garra, A. Type I interferons in infectious disease. Nat Rev Immunol 2015, 15, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, K.; Li, C.; Liao, S.; Yao, X.; Ouyang, Y.; Liu, Y.; et al. Ferritinophagy, a form of autophagic ferroptosis: New insights into cancer treatment. Front Pharmacol 2022, 13, 1043344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Wu, N.; Peng, M.; Oyang, L.; Jiang, X.; Peng, Q.; et al. Ferritinophagy: research advance and clinical significance in cancers. Cell Death Discov 2023, 9, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancias, J.D.; Wang, X.; Gygi, S.P.; Harper, J.W.; Kimmelman, A.C. Quantitative proteomics identifies NCOA4 as the cargo receptor mediating ferritinophagy. Nature 2014, 509, 105–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochette, L.; Dogon, G.; Rigal, E.; Zeller, M.; Cottin, Y.; Vergely, C. Lipid peroxidation and iron metabolism: Two corner stones in the homeostasis control of ferroptosis. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishio, M.; Tsurudome, M.; Ito, M.; Garcin, D.; Kolakofsky, D.; Ito, Y. Identification of paramyxovirus V protein residues essential for STAT protein degradation and promotion of virus replication. J Virol 2005, 79, 8591–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitagawa, Y.; Yamaguchi, M.; Zhou, M.; Nishio, M.; Itoh, M.; Gotoh, B. Human parainfluenza virus type 2 V protein inhibits TRAF6-mediated ubiquitination of IRF7 to prevent TLR7- and TLR9-dependent interferon induction. J Virol 2013, 87, 7966–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohta, K.; Matsumoto, Y.; Nishio, M. Human parainfluenza virus type 2 V protein inhibits caspase-1. J Gen Virol 2018, 99, 501–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohta, K.; Saka, N.; Nishio, M. Human parainfluenza virus type 2 V protein modulates iron homeostasis. J Virol 2021, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, H.U.; Haj-Yehia, A.; Levi-Schaffer, F. Role of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in apoptosis induction. Apoptosis 2000, 5, 415–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Ghosh, S.; Mandal, A.; Ghosh, N.; Sil, P.C. ROS-associated immune response and metabolism: a mechanistic approach with implication of various diseases. Arch Toxicol 2020, 94, 2293–2317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Choi, E.H.; Lee, H.J. Comprehensive serotyping and epidemiology of human adenovirus isolated from the respiratory tract of Korean children over 17 consecutive years (1991-2007). J Med Virol 2010, 82, 624–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynch, J.P.; Fishbein, M.; Echavarria, M. Adenovirus. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2011, 32, 494–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ison, M.G. Adenovirus infections in transplant recipients. Clin Infect Dis 2006, 43, 331–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnadas, C.; Schmidt, D.J.; Fischer, T.K.; Fonager, J. Molecular epidemiology of human adenovirus infections in Denmark, 2011-2016. J Clin Virol 2018, 104, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shieh, W.J. Human adenovirus infections in pediatric population - An update on clinico-pathologic correlation. Biomed J 2022, 45, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bil-Lula, I.; Ussowicz, M.; Rybka, B.; Wendycz-Domalewska, D.; Ryczan, R.; Gorczyńska, E.; et al. Hematuria due to adenoviral infection in bone marrow transplant recipients. Transplant Proc 2010, 42, 3729–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kojaoghlanian, T.; Flomenberg, P.; Horwitz, M.S. The impact of adenovirus infection on the immunocompromised host. Rev Med Virol 2003, 13, 155–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

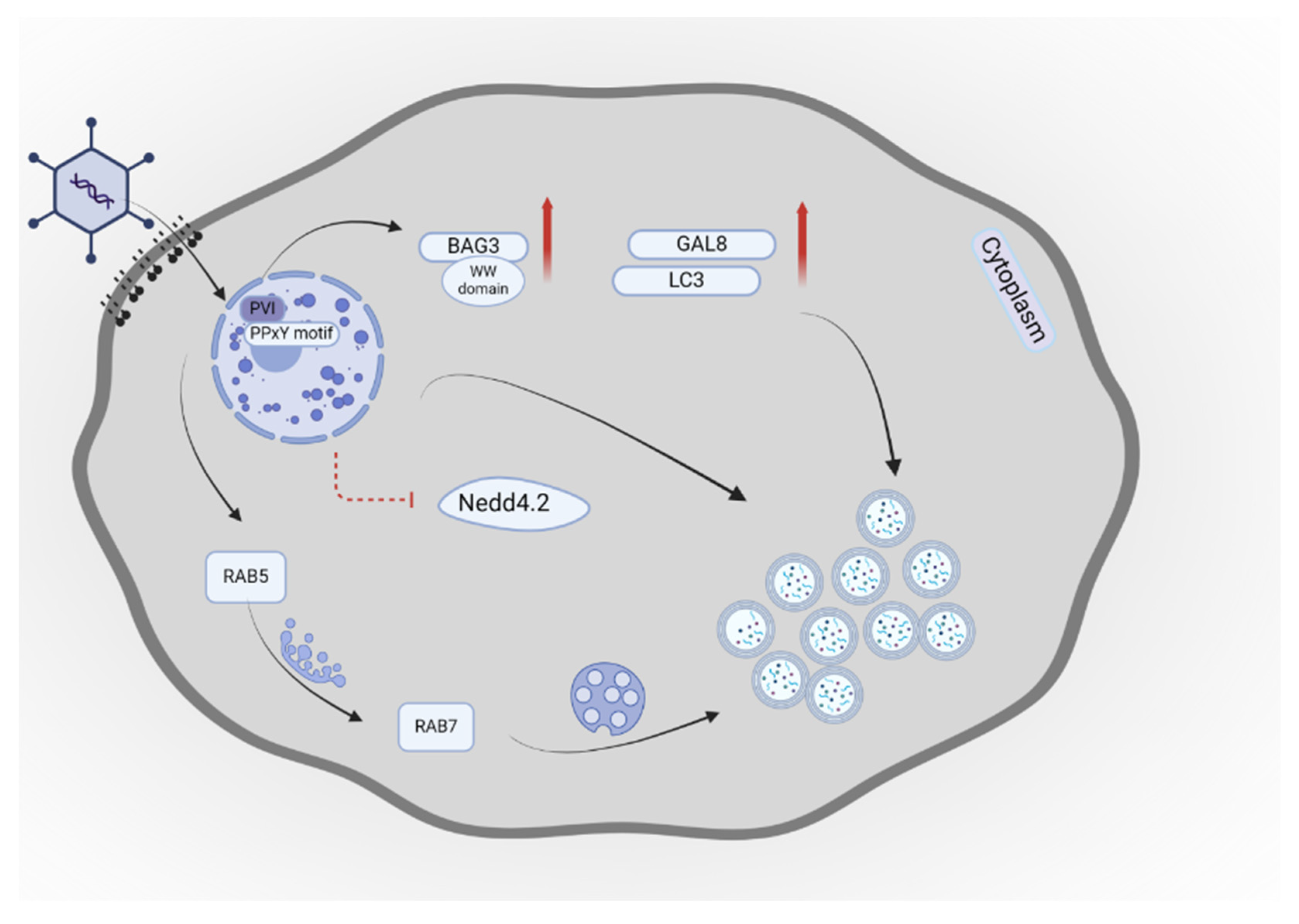

- Montespan, C.; Wiethoff, C.M.; Wodrich, H. A Small viral PPxY peptide motif to control antiviral autophagy. J Virol 2017, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wodrich, H.; Henaff, D.; Jammart, B.; Segura-Morales, C.; Seelmeir, S.; Coux, O.; et al. A capsid-encoded PPxY-motif facilitates adenovirus entry. PLoS Pathog 2010, 6, e1000808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutagalung, A.H.; Novick, P.J. Role of Rab GTPases in membrane traffic and cell physiology. Physiol Rev 2011, 91, 119–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Marlin, M.C. Rab family of GTPases. Methods Mol Biol 2015, 1298, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Girard, E.; Chmiest, D.; Fournier, N.; Johannes, L.; Paul, J.L.; Vedie, B.; et al. Rab7 is functionally required for selective cargo sorting at the early endosome. Traffic 2014, 15, 309–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerra, F.; Bucci, C. Multiple roles of the small GTPase Rab7. Cells 2016, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, X.; Carlin, C.R. Host cell autophagy modulates early stages of adenovirus infections in airway epithelial cells. J Virol 2013, 87, 2307–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Cheng, J.; Shen, L.; Chen, M.; Sun, K.; Li, J.; et al. Rab5c promotes RSV and ADV replication by autophagy in respiratory epithelial cells. Virus Res 2024, 341, 199324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montespan, C.; Marvin, S.A.; Austin, S.; Burrage, A.M.; Roger, B.; Rayne, F.; et al. Multi-layered control of Galectin-8 mediated autophagy during adenovirus cell entry through a conserved PPxY motif in the viral capsid. PLoS Pathog 2017, 13, e1006217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Duan, Y.; Wang, W.; Li, Q.; Tian, J.; Zhu, Y.; et al. Autophagy induced by human adenovirus B7 structural protein VI inhibits viral replication. Virol Sin 2023, 38, 709–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stürner, E.; Behl, C. The role of the multifunctional BAG3 protein in cellular protein quality control and in disease. Front Mol Neurosci 2017, 10, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grand, R.J. The structure and functions of the adenovirus early region 1 proteins. Biochem J 1987, 241, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheitasi, H.; Sabbaghian, M.; Fadaee, M.; Mohammadzadeh, N.; Shekarchi, A.A.; Poortahmasebi, V. The relationship between autophagy and respiratory viruses. Arch Microbiol 2024, 206, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, R.C.M.C.; Ribeiro, J.S. ; da Silva GPD; da Costa, L. J.; Travassos, L.H.; Microbiology, I. Autophagy modulators in coronavirus diseases: a double strike in viral burden and inflammation. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2022, 12, 845368. [Google Scholar]

- Horie, R.; Nakamura, O.; Yamagami, Y.; Mori, M.; Nishimura, H.; Fukuoka, N.; et al. Apoptosis and antitumor effects induced by the combination of an mTOR inhibitor and an autophagy inhibitor in human osteosarcoma MG63 cells. Int J Oncol 2015, 48, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullen, P.J.; Garcia Jr, G.; Purkayastha, A.; Matulionis, N.; Schmid, E.W.; Momcilovic, M.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection rewires host cell metabolism and is potentially susceptible to mTORC1 inhibition. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renna, M.; Schaffner, C.; Brown, K.; Shang, S.; Tamayo, M.H.; Hegyi, K.; et al. Azithromycin blocks autophagy and may predispose cystic fibrosis patients to mycobacterial infection. J Clin investig 2011, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trial, C. ; Azithromycin treatment for respiratory syncytial virus-induced respiratory failure in children. 2021.

- Huang, P.-J.; Chiu, C.-C.; Hsiao, M.-H.; Le Yow, J.; Tzang, B.-S.; Hsu, T.-C. Potential of antiviral drug oseltamivir for the treatment of liver cancer. Int J Oncol 2021, 59, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trial, C. ; Adaptive assessment of treatments for influenza: A phase 2 multi-centre adaptive randomised platform trial to assess antiviral pharmacodynamics in early symptomatic influenza infection (AD ASTRA). 2022.

- Gust, W. The pharmacodynamic functions of low-dose rapamycin as a model for universal influenza protection, in Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College. 2017, University of Mississippi: Honors Theses. p. 76.

- Huang, C.-T.; Hung, C.-Y.; Chen, T.-C.; Lin, C.-Y.; Lin, Y.-C.; Chang, C.-S.; et al. Rapamycin adjuvant and exacerbation of severe influenza in an experimental mouse model. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 4136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trial, C. ; A randomized controlled trial of adjunctive sirolimus and oseltamivir versus oseltamivir alone for treatment of influenza. 2019.

- Molina-Molina, M.; Machahua-Huamani, C.; Vicens-Zygmunt, V.; Llatjós, R.; Escobar, I.; Sala-Llinas, E.; et al. Anti-fibrotic effects of pirfenidone and rapamycin in primary IPF fibroblasts and human alveolar epithelial cells. BMC Pulm Med 2018, 18, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trial, C. ; SECOVID: A multi-center, randomized, dose-ranging parallel-group trial assessing the efficacy of sirolimus in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 pneumonia for the prevention of post-COVID fibrosis. 2021.

- Mondaca-Ruff, D.; Riquelme, J.A.; Quiroga, C.; Norambuena-Soto, I.; Sanhueza-Olivares, F.; Villar-Fincheira, P.; et al. Angiotensin II-regulated autophagy is required for vascular smooth muscle cell hypertrophy. Front Pharmacol 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trial, C. ; Evaluation of influenza vaccination and treatment with ACEI and ARB in the evolution of SARS-CoV2 infection. 2020.

- Brimson, J.M.; Prasanth, M.I.; Malar, D.S.; Brimson, S.; Thitilertdecha, P.; Tencomnao, T. Drugs that offer the potential to reduce hospitalization and mortality from SARS-CoV-2 infection: The possible role of the sigma-1 receptor and autophagy. Expert Opin Ther Targets 2021, 25, 435–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Category | Medications | Mechanism | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lysosomotropic Agents | Chloroquine, Hydroxychloroquine | Increasing the pH within lysosomes/ Block entry mechanisms of virus / does not inhibit infection of human lung cells with SARS-CoV-2. Also blocks some virus’ biosynthetic processes after entry. | [130,136,137] |

| Azithromycin | synergistic effect of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin on the reduction of viral load of SARS-CoV-2 | [138] | |

| Artemisinin | Target the Lys353 and Lys31 binding hotspots on the viral spike protein/ NF-κB inhibition/ Block SARS-CoV-2 infection | [139,140,141] | |

| Imatinib | Inhibiting fusion of the virions at the endosomal membrane | [142] | |

| Protease Inhibitors | Lopinavir/Ritonavir | Inhibiting viral protease/ Reduction in viral load | [132,133] |

| Teicoplanin | Suppressing the proteolytic activity of cathepsin L on Spike/ Prevent the entry of SARS-CoV-2 into the cytoplasm | [143,144] | |

| PI3K/mTOR Regulators | Rapamycin | Inhibits mTORC1/ Inhibits protein synthesis/ Reducing viral replication/ Reducing MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 infection by activating autophagy | [134] |

| Everolimus | Induces autophagy by blocking mTORC1/ Inhibits MERS-CoV infection | [135] | |

| Nitazoxanide | Stimulates autophagy by blocking mTORC1/ Inhibits replication of MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 | [145,146] | |

| Wortmannin | Suppresses autophagy by inhibition of PI3K/ Inhibits MERS-CoV infection | [135] |

| Trial Identifier | Activity | Intervention | Phase | Primary Outcome | Link | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT05060705 | COVID-19 | Efesovir in comparison with the drug Remdesivir | Phase 2 | Reduction of viral load in COVID-19 patients | https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05060705 | |

| NCT05218356 | COVID-19 | Codivir | Phase 2 | Efficacy in reducing the severity of COVID-19 | https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05218356 | |

| NCT06128967 | COVID-19 | Metformin/ Fluvoxamine | Phase 3 | Evaluation of treatment efficacy in long COVID patients | https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06128967 | |

| NCT06147050 | COVID-19 | Metformin | Phase 3 | Assessment of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome in long COVID patients | https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06147050 | |

| NCT04345406 | COVID-19 | ACE inhibitors | Phase 3 | Clinical efficacy in COVID-19 treatment | https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04345406 | |

| NCT04948203 | COVID-19 | Sirolimus | Phase2 Phase 3 |

Prevention of post-COVID fibrosis in hospitalized patients | https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04948203 | |

| NCT06024096 | Influenza | Atorvastatin | Phase 4 | Effect of statins on influenza vaccine response | https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06024096 | |

| NCT05026749 | RSV | Azithromycin | Phase 3 | Efficacy in RSV-induced respiratory failure in children | https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05026749 | |

| NCT03901001 | Influenza | Sirolimus + Oseltamivir vs. Oseltamivir Alone | Phase 3 | Comparison of treatment outcomes for influenza | https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT03901001 |

|

| NCT05648448 | Influenza | Influenza antivirals | Phase 2 | Assessing antiviral efficacy in early symptomatic influenza |

https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05648448 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).