1. Introduction

A growing body of research links excessive screen-based media use and externalizing problems in early childhood, although effect sizes of these associations are usually small [

1,

2,

3]. It is commonly agreed, that not only quantity, but also quality of screen time is important in terms of outcomes, be it content or circumstances of screen use [

4]. There is some evidence that screen time may be particularly detrimental when used as a tool to manage children’s behavior or emotions [

5,

6,

7]. Although screens can provide short-term relief for both children and parents, excessive reliance on this strategy may hinder the development of self-regulation and reinforce dysregulated behaviors. The present study aims to explore the complex interplay between child temperament, parental distress, and screen use in contributing to externalizing problems during the preschool years.

Preschool-aged children today are immersed in screen-based activities, with digital devices becoming integral to their daily routines. While age-appropriate screen media has demonstrated some benefits for cognitive development [

8,

9], excessive and unsupervised screen use poses significant risks. Prolonged exposure to screens has been associated with poorer child development [

10,

11] and in particular with delayed language development in preschool age [

12,

13,

14,

15], attentional difficulties [

16], obesity and other health problems [

17,

18]. Also, empirical evidence links longer screen time with increased behavioral challenges [

2], although the direction of these associations is not always clear. Many studies found links between screen time and subsequent externalizing problems [

11,

19], however, the findings become less clear when background problems are considered. A recent longitudinal study found that higher levels of externalizing behaviors at age 3 were associated with moderate increase in screen time two years later, but not vice versa [

20]. This supports the idea that screens are potentially being used as a tool to modulate challenging behaviors or to placate dysregulated children in the early years. These dynamics underscore the need to examine the underlying mechanisms linking screen time and behavioral difficulties, particularly in the context of child temperament and parental stress.

Child temperament, a construct encompassing individual differences in reactivity and regulation, is a key factor in understanding behavioral challenges. Reactivity refers to physiological, emotional, and attentional responses to stimuli, while regulation involves the processes that modulate these responses [

21,

22]. Effortful control, a regulatory mechanism, gradually matures during early childhood, enabling children to manage their emotions and behaviors more effectively over time [

23]. However, this regulatory capacity is not fully developed in preschool-aged children, leaving them more dependent on caregivers for emotional support.

Highly reactive children, who often struggle with self-soothing and regulation, rely even more heavily on caregivers for comfort [

24,

25]. Thus, temperament may act as a key factor for child's behavior, including behavioral challenges, which are further influenced by parental responses to specific behaviors [

26]. Furthermore, temperament characteristics and environmental factors both interact in child developmental outcomes, either increasing or decreasing the risk of various difficulties or disorders. Temperament-based regulation can mitigate risk factors and stressors [

21].

Researchers suggest there is a link between child emotional reactivity and screen time [

27,

28]. As children with low self-regulatory abilities are harder to soothe or regulate their behaviors, this may also elicit parents' higher use of digital media as a regulatory strategy and increase child exposure to screens. While this strategy may provide immediate relief, it can interfere with the development of self-regulation [

29,

30], further exacerbating behavioral difficulties.

Parental stress is another critical factor influencing both children’s screen time and behavioral outcomes. Research suggests that parents who have less personal, social and financial resources and aren’t able to meet their child care needs, are more prone to expose children to screen use [

31]. Greater young children’s exposure to screens has been shown to relate to poorer mother’s relational well-being [

32], parental conflict [

33], socioeconomic issues [

5], and overall parenting stress [

34,

35,

36]. Along these lines, parents, experiencing more stress in any domain of their life, may deviate from their usual rules or limits on screen media use and allow their children more screen time in the short term to reduce their own stress levels and may use screens as a tool for coping with parenting stress and child’s dysregulation [

35].

The association between parental stress and screen use may be particularly pronounced in families raising temperamentally reactive children. Parents of reactive children may experience heightened stress due to child’s difficulty with self-regulation and tendency towards emotional outbursts. These challenges can lead parents to use screens as a tool to soothe their child or to create a temporary reprieve from parenting demands [

37]. To sum up, the relationship between screen time, child temperament, and externalizing problems is complex and bidirectional. While longer screen time has been linked to greater behavioral challenges [

2], it may also reflect parents’ attempts to manage pre-existing difficulties [

37]. For example, parents of children with high emotional reactivity may use screens as a regulatory tool, inadvertently reinforcing dysregulated behaviors and increasing the child’s reliance on screens for emotional management. Moreover, parental stress interacts with child temperament to shape media-related decisions [

5]. Parents who experience high levels of stress may be less consistent in enforcing screen time limits, particularly when managing a reactive child. These dynamic highlights the interplay between individual and environmental factors in contributing to externalizing problems.

Although screen time is by no means the sole contributor to behavioral challenges, it serves as an important contextual factor that interacts with child and parental characteristics. The complexity of interplay of screen time, child’s factors, such as emotional reactivity and gender, and parental factors, such as parental distress and the media-related coping practices, are still under-researched in preschoolers, and therefore is the main aim of the present study.

The research questions of this study were: (1) how are child screen time and parental media-related coping associated with preschoolers’ behavioral problems? (2) what are the relationships among child emotional reactivity, parental distress, and child screen time, and how do these factors interact to predict behavioral problems in preschoolers? (3) do child screen time and parental media-related coping contribute directly or indirectly to the prediction of preschoolers’ behavioral problems, accounting for child emotional reactivity and parental distress?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

The study sample included 754 children (49.1% girls), aged 2 to 5 years old, not having chronic diseases, with 95.5% of children attending pre-school education services (kindergarten). The mean children’s age was 44.6 months (SD = 13.7). Child mothers’ (main caregiver’s) mean age was 32.7 years (SD = 4.9). Of mothers, 65.9% had high university education, 14.2% - high non-university, 12.9% - secondary professional, and 7.1% secondary non-professional or less education. 82.4% of mothers were married and 61.9% were of urban residence. The sociodemographic characteristics of participants correspond to the main tendencies of educational attainment, marital status and place of residence in Lithuania.

This research is a part of an extensive national study “Electronic Media Use and Young Children’s Health” conducted in the year 2017 and funded by the Research Council of Lithuania (agreement no. GER-006/2017). The research was approved by the Regional Biomedical Research Ethics Committee of Vilnius (No. 158200-2017/04). Parents of toddlers and pre-school aged children living in various regions of Lithuania were invited to take part in the research through pre-school education institutions, health care specialists and social media. After signing in the informed consent parents completed paper-pencil or online questionnaires. Those parents, who completed online questionnaires (n = 164, 21.8%) had higher educational level (Mann-Whitney U = 36147.00, p <.001), reported higher parental distress (t(749) = -4.45, p < 0.001), lower child emotional reactivity (t(749) = 2.39, p = .018) and shorter child screen time (t(749) = 2.48, p = .013) than parents, who completed paper-pencil questionnaires (n = 587, 78.2%). There were no differences between these groups in the level of child externalizing problems, child gender and parental media-related coping.

2.2. Instrument and Measures

Child emotional reactivity and externalizing problems were measured using the Lithuanian version of the Child Behavior Checklist [

38,

39,

40]. The CBCL/1½-5 is a 100-item parent-report measure designed to screen for the problem behaviors in preschool-age children, and consists of 7 scales: emotionally reactive, anxious/depressed, somatic complaints, withdrawn, sleep problems, attention problems and aggressive behavior. The first four scales then are combined to the internalizing problems factor, whereas attention problems and aggressive behavior comprise the externalizing problems factor. Each item describes a specific behavior, and parents rate its frequency on a three-point Likert-type scale (0 - not true; 1 - somewhat or sometimes true; 2 - very true or often true) based on the preceding 2 months.

Emotional reactivity scale consists of 9 items and measures a child's propensity for intense and frequent emotional reactions as well as difficulty adapting to changes [

38]. The total score on the scale can range from 0 to 18. A higher score indicates more pronounced emotional reactivity in children. The internal consistency of the scale in this study was appropriate, indicating its good reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.72).

Externalizing problems scale consists of 24 items and measures a child's behavioral problems. The internal consistency of the scale in this study was appropriate, indicating its good reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.87).

Child screen time was measured using a parent-report questionnaire. Parents provided information about the duration of their child’s screen time on weekdays and weekends, for various types of screen-based devices (smartphone, tablet, computer, game console, and TV). They answered separate questions about the usual daily duration for each device, selecting from the following options: “no or almost no usage” (1), “15 minutes to 30 minutes per day” (2), “30 minutes to 1 hour per day” (3), “1 to 2 hours per day” (4), “2 to 3 hours per day” (5), “3 to 4 hours per day” (6), and “more than 4 hours per day” (7). To estimate the average daily screen time, each response was first converted to minutes as follows: (1) – 0 minutes, (2) – 22.5 minutes, (3) – 45 minutes, (4) – 90 minutes, (5) – 150 minutes, (6) – 210 minutes, and (7) – 270 minutes. The average daily screen time was then calculated using the formula: (screen use on weekdays [converted to minutes] x 5 days + screen use on weekends [converted to minutes] x 2 days) / 7 days. A higher score indicates longer screen time.

Parental distress was measured using a six-item scale, where the respondent parent (caregiver) rated each item on a 5-point scale (from 1 – 'almost every day' to 5 – 'rarely or never') based on how often they had experienced the following in the past six months: (1) physical pain or discomfort (e.g., headache, stomach pain, etc.); (2) sadness or depressive mood; (3) irritability or bad mood; (4) nervous tension or anxiety; (5) problems falling asleep; (6) drowsiness or lack of activity. A total distress score was calculated, and for analysis, the variable was transformed so that higher values indicated greater parental distress. The reliability of this scale in the present study was very good (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.83).

Parental media-related coping was measured on a 4-point scale (from 1 – never or almost never, 2 – sometimes, 3 – often, 4 – almost always) on how often respondent parent (caregiver) use screens when a child is upset, frustrated. In the further analysis, this variable was transformed into binary pseudo-variable – if parents use screens to calm down a child (0 – never or almost never use, 1 – at least sometimes use).

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Bivariate Spearman correlations among study variables were calculated. Mean comparisons between two groups were counted using Student t-test for interval variables and non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test for ordinal variables. Correlations, descriptive statistics, distributions and comparisons were run in SPSS 23.0. The Mplus 6.0 software package [

41] was used for structural equation modeling. The following model fit indices were utilized: the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI). A good model fit is indicated by an RMSEA value of < 0.05 and CFI and TLI values > 0.90.

3. Results

According to the results of the study, the average duration of children’s screen time, as indicated by their parents, was 111.86 minutes (SD = 83.94 minutes). Additionally, 35.23% (n = 260) of the respondent parents reported at least sometimes using screens when their child was upset, frustrated, or sad.

First, correlations between child variables (age, emotional reactivity, screen time and externalizing problems) and parental distress were analyzed (see

Table 1). Since the majority of the mothers shared similar sociodemographic characteristics in terms of educational level and family status (80.1% had high education, either university or non-university type, and 82.4% were married), these variables were not controlled in the study assuming that there may not be enough variability to influence the outcomes.

The results indicated that child externalizing problems were associated to emotional reactivity, screen time, and parental distress (see

Table 1). Additionally, child emotional reactivity was positively related to both screen time and parental distress, suggesting that, according to parents, more emotionally reactive children spent more time using screens and exhibited higher levels of externalizing problems. Furthermore, parents of more emotionally reactive children reported experiencing greater distress. The results also revealed a positive correlation between parental distress and child screen time. Finally, child age was positively associated only with screen time, indicating that parents of older children reported higher screen time for their children.

Secondly, we examined whether the study variables differed based on parental media-related coping. The results, presented in

Table 2, indicate that children whose parents used screens as a coping strategy were younger, more emotionally reactive, exhibited more externalizing problems, and spent more time using screens. Additionally, parents who relied on media-related coping reported higher levels of distress.

Thirdly, we examined gender differences in the study variables. The results showed that girls and boys differed only in their levels of externalizing problems, with boys having a higher mean score for externalizing problems than girls (see

Table 3). There were no gender differences in parental media-related coping (χ² = 0.52, p = 0.538)

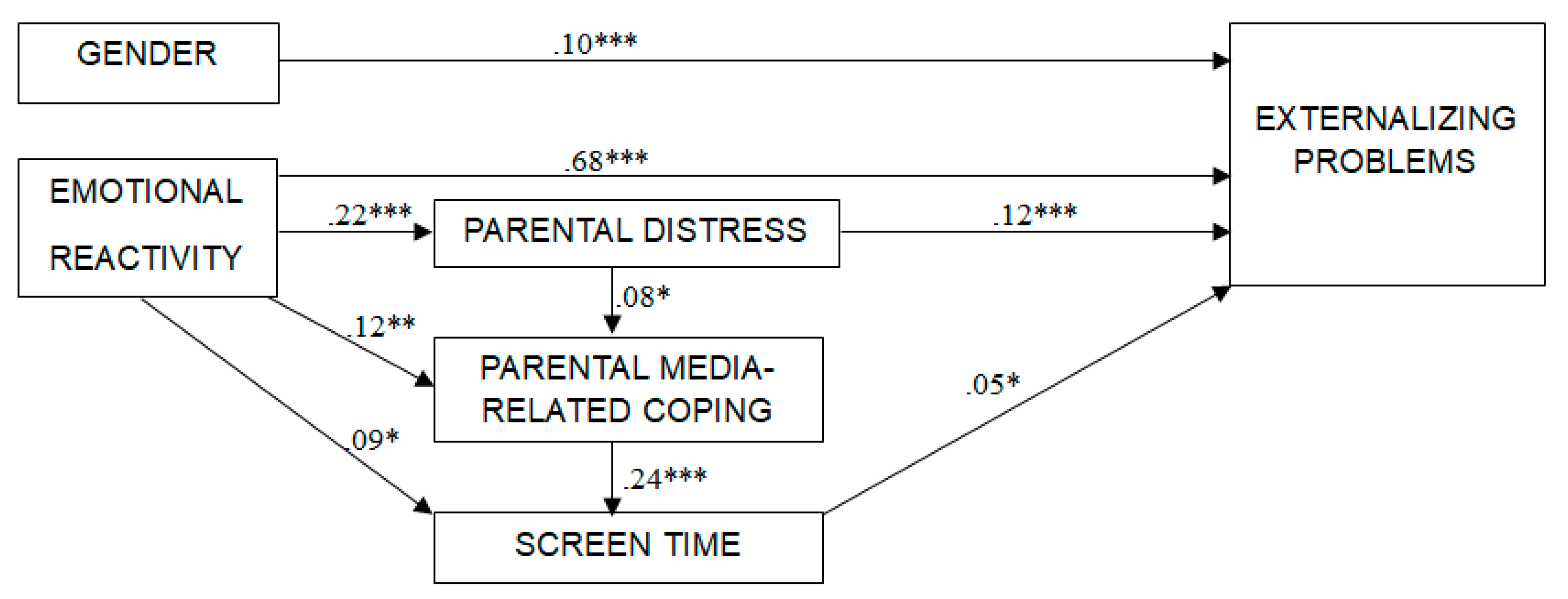

Finally, a model was developed to explore the interrelationships between child externalizing problems, screen time, parental distress, and parental media-related coping. The initial model was constructed based on the correlations and group comparisons presented in

Table 1,

Table 2 and

Table 3. Later, the model was adjusted by removing statistically insignificant relationships and adding new statistically significant relationships. The final model fits perfectly with the data: χ2 (6) = 2.98, p = 0.812, CFI = 1.00, TLI = 1.01, RMSEA = .000. Child age was controlled in the model (see

Figure 1).

The results, as depicted in the model, showed that child externalizing problems were directly predicted by higher emotional reactivity, greater screen time, higher parental distress, and male gender. Child screen time was predicted by child emotional reactivity and parental media-related coping. Additionally, parental media-related coping was predicted by child emotional reactivity and parental distress. Although parental coping did not directly predict child externalizing problems, it had an indirect effect through increased child screen time.

4. Discussion

Although some evidence suggests direct links between screen media use and behavior problems in early childhood, findings across studies remain inconsistent [

2,

34]. This highlights the need to investigate potential mediating factors. The present study aimed to examine the interplay among child temperament, parental distress, and screen use in contributing to externalizing problems during the preschool years.

Firstly, the results of our study revealed that child gender, emotional reactivity, parental distress, and screen time all play roles in predicting child’s externalizing problems, with emotional reactivity having the most significant direct effect. Screen time had a significant but small direct effect on externalizing problems, when accounting for other individual and contextual variables. This suggests that, while screen time contributes to externalizing problems, its effect is weaker compared to other predictors. These findings align with previous studies that report significant but weak associations between screen time and externalizing behavior problems [

2]. Additionally, consistent with prior research, the results support the notion that the relationship between screen time and externalizing problems is influenced by other background variables, such as male gender [

2] and parental stress [

42]. A recent illustration of the interplay between parental mental health, screen practices, and child outcomes can be seen in the natural experiment of the Covid-19 pandemic, during which there was a significant increase in screen time, as well as in parental stress and child externalizing behaviors [

43].

Secondly, while parental media-related coping did not directly predict externalizing problems, its effect was mediated by increased child screen time. Both child emotional reactivity and parental distress contributed to the variance in parental media-related coping. In line with the aforementioned studies, parents of highly reactive children may be more likely to adopt coping strategies that are immediately effective in soothing a child, such as increased screen time. Moreover, child emotional reactivity may be a primary or additional driver of parental distress and distressed parents may struggle to consistently enforce rules or find alternative emotion regulation strategies, leading to more reliance on screens. Over time, excessive screen time may exacerbate emotional reactivity and disrupt self-regulation, contributing to the development of externalizing behaviors [

29,

30].

Thirdly, the results of our study suggest that child emotional reactivity is a central variable, influencing multiple factors such as parental distress, media-related coping, and screen time, and directly and indirectly affecting externalizing problems. Beyond the direct effect of emotional reactivity on behavioral problems, parental distress and screen time may serve as mediators, helping to explain these associations.

To sum up, the results of our study reveal that emotional reactivity, as a potential factor of vulnerability, plays a significant role in behavioral problems. It also contributes to parental distress and to the use of screens as a coping mechanism, which in turn predicts behavioral problems. These findings highlight the importance of emotional reactivity, particularly when other unfavorable factors in the emotional environment of the family are present. Thus, cumulative family emotional risks are crucial in understanding children’s behavioral problems. Given that children's self-regulation abilities are not yet fully developed, their reactivity may predominate [

22,

23]. Therefore, emotional reactivity, as an innate aspect of a child’s temperament, plays a critical role in the regulation and expression of their behavior. Additionally, as toddlers and preschool children have less developed self-control, they are more susceptible to the negative influences of their home environment [

44]. Parents must therefore be mindful of their emotional reactions—managing their own distress—and avoid using screens to calm their children or themselves.

This study analyzed a large, population-based sample of toddlers and preschoolers, using statistical analyses that considered interactions and pathways among variables. However, there are several limitations to acknowledge. First, child emotional reactivity and behavioral problems, screen time, parental distress, and media-related coping were all reported by parents. While parents and caregivers can provide valuable insights into a child's traits and their surrounding environment, their perceptions may be influenced by bias and subjectivity, particularly in relation to the child’s behavioral issues and emotional reactivity. Additionally, parental coping was measured using a single item assessing screen use to calm a child. This measure did not capture the various situations and contexts in which screens are used as a coping strategy, which may limit the reliability of the analysis. We suggest that future research should use more comprehensive measures of screen-based parental coping. Moreover, when reporting on screen-based media use, social desirability bias is a significant factor to consider. Although the study sample aligns well with the demographic profile of the national population, it primarily includes families with low to moderate socioeconomic risks and children without severe health concerns. Finally, it is important to mention the data collection strategy. Most parents of participating children were reached through doctor's offices and educational institutions and completed a paper-and-pencil questionnaire. However, approximately one-fifth of the study sample was reached via social media, and these parents completed an online questionnaire. Some demographic and study variables differed between these two groups, suggesting that the method of participant recruitment and data collection may have influenced the results. While the dual nature of the data collection could be considered a methodological limitation, we believe it helped mitigate sampling bias, which is unavoidable in research relying on convenience sampling.

Furthermore, our study focused solely on one aspect of temperament—reactivity. However, the other dimension, regulation, is also crucial for understanding both behavioral problems and the potential effects of screen-based media use. Future research should adopt multimethod approaches (e.g., passive sensing apps and questionnaires) and longitudinal designs to assess the effects of screen-based media use on child outcomes. Additionally, it is important for future studies to examine the screen time of the entire family and explore the possible cumulative effects of both children’s and parents’ total screen time on child development [

14,

44].

Despite the limitations of our study, we conclude that a child’s emotional reactivity, as one dimension of temperament, along with parental distress, child screen time, and parental media-related coping, collectively contribute to less favorable conditions for the child’s psychosocial development. These findings suggest potential directions for interventions aimed at reducing or managing behavioral problems. While individual predispositions, such as temperament traits, typically cannot be directly altered, managing behavioral issues may be facilitated by establishing appropriate, child-friendly screen media use.

Based on the results of this study, we emphasize the need to educate both parents and professionals working with families about children’s mental health and the responsible use of screen media. It is crucial to provide guidance, support, and training for parents, particularly those raising children with higher emotional reactivity. A key priority is to educate parents on establishing healthy screen time habits for their children. This includes: (1) managing the frequency and duration of screen time based on the child’s age; (2) carefully selecting age-appropriate content—such as games, movies, and videos—and using parental control tools to manage unsuitable content; and (3) ensuring that screen time does not replace essential childhood activities, such as physical activity and free play, which are vital for development [

45].

Author Contributions

Project Administration, R.J.; conceptualization, R.J., R.B., E.B. and L.R.; methodology, R.J., R.B. and L.R.; formal analysis, R.J. and R.B.; writing—original draft preparation, R.J., R.B., L.R.; writing—review and editing, R.J., R.B., E.B. and L.R.; visualization, R.J., R.B., E.B. and L.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is a part of an extensive national study “Electronic Media Use and Young Children’s Health” conducted in the year 2017-2018 and was funded by the Research Council of Lithuania (agreement no. GER-006/2017).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of Vilnius University and approved by the by the Regional Biomedical Research Ethics Committee of Vilnius (No. 158200-2017/04).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to ethical and confidentiality reasons.

Acknowledgments

We thank Rūta Praninskienė, Vaidotas Urbonas, Ilona Laurinaitytė, Edita Babkovskienė, Laura Vitkė, who also collected the data and were the researchers at the study project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Breidokiene, R.; Jusiene, R.; Urbonas, V.; Praninskiene, R.; Girdzijauskiene, S. Sedentary Behavior among 6–14-Year-Old Children during the COVID-19 Lockdown and Its Relation to Physical and Mental Health. Healthcare 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eirich, R.; McArthur, B.A.; Anhorn, C.; McGuinness, C.; Christakis, D.A.; Madigan, S. Association of Screen Time With Internalizing and Externalizing Behavior Problems in Children 12 Years or Younger: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2022, 79, 393–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jusiene, R.; Praninskiene, R.; Petronyte, L.; Breidokiene, R.; Laurinaityte, I.; Rakickiene, L.; Urbonas, V.; Babkovskiene, E.; Vitke, L. Analysis of physical and mental health in early childhood: The importance of screen media use. Visuomenės Sveikata. 2019, 1, 56–67. Available online: https://visuomenessveikata.hi.lt/uploads/pdf/visuomenes%20sveikata/2019.1(84)/Visuomenes%20sveikata%202019%201(84)%20Visas.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Huber, B.; Yeates, M.; Meyer, D.; Fleckhammer, L.; Kaufman, J. The effects of screen media content on young children‘s executive functioning. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 2018, 170, 72–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyne, S.M.; Shawcroft, J.; Gale, M.; Gentile, D.A.; Etherington, J.T.; Holmgren, H.; Stockdale, L. Tantrums, toddlers and technology: Temperament, media emotion regulation, and problematic media use in early childhood. Computers in Human Behavior 2021, 120, 106762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coyne, S.M.; Reschke, P.J.; Stockdale, L.; Gale, M.; Shawcroft, J.; Gentile, D.A.; Brown, M.; Ashby, S.; Siufanua, M.; Ober, M. Silencing screaming with screens: The longitudinal relationship between media emotion regulation processes and children's emotional reactivity, emotional knowledge, and empathy. Emotion 2023, 23, 2194–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radesky, J.S.; Kaciroti, N.; Weeks, H.M.; Schaller, A.; Miller, A.L. Longitudinal associations between use of mobile devices for calming and emotional reactivity and executive functioning in children aged 3 to 5 years. JAMA Pediatrics 2023, 177, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linebarger, D.L.; Vaala, S.E. Screen media and language development in infants and toddlers: An ecological perspective. Developmental Review 2010, 30, 176–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courage, M.L.; Frizzell, L.M.; Walsh, C.S.; Smith, M. Toddlers using tablets: They engage, play, and learn. Front Psychol 2021, 12, 564479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madigan, S.; Browne, D.; Racine, N.; Mori, C.; Tough, S. Association between screen time and children‘s performance on a developmental screening test. JAMA Pediatrics 2019, 173, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNeill, J.; Howard, S.J.; Vella, S.A.; Cliff, D.P. Longitudinal associations of electronic application use of media program viewing with cognitive and psychosocial development in preschoolers. Academic pediatrics 2019, 19, 520–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chonchaiya, W.; Pruksananonda, C. Television viewing associates with delayed language development. Acta Paediatrica 2008, 97, 977–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madigan, S.; McArthur, B.A.; Anhorn, C.; Eirich, R.; Christakis, D.A. Associations between screen use and child language skills: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatrics 2020, 174, 665–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustonen, R.; Torppa, R.; Stolt, S. Screen Time of Preschool-Aged Children and Their Mothers, and Children’s Language Development. Children 2022, 9, 1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tulviste, T.; Tulviste, J. (2024). Weekend screen use of parents and children associates with child language skills. Front. Dev. Psychol. 2024, 2, 1404235. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/developmental-psychology/articles/10.3389/fdpys.2024.1404235/full (accessed on 20 November 2024). [CrossRef]

- Noa Gueron-Sela, N.; Gordon-Hacker, A. Longitudinal links between media use and focused attention through toddlerhood: A cumulative risk approach. Frontiers in Psychology 2020, 11, 569222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priftis, N.; Panagiaotakos, D. Screen Time and Its Health Consequences in Children and Adolescents. Children 2023, 10, 1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Coronel, A.A.; Abdu, W.J.; Alshahrani, S.H.; Treve, M.; Jalil, A.; Alkhayyat, A.S.; Singer, N. Childhood obesity risk increases with increased screen time: a systematic review and dose–response meta-analysis. Journal of Health, Population & Nutrition r 2023, 42, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkes, A.; Sweeting, H.; Wight, D.; Henderson, M. Do television and electronic games predict children's psychosocial adjustment? Longitudinal research using the UK Millennium Cohort Study. Archives of Disease in Childhood 2013, 98, 341–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neville, R.D.; McArthur, B.A.; Eirich, R.; Lakes, K.D.; Madigan, S. Bidirectional associations between screen time and children’s externalizing and internalizing behaviors. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry 2021, 62, 1475–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothbart, M.K.; Ahadi, S.A.; Hershey, K.L.; Fisher, P. Investigations of temperament at three to seven years: the Children's Behavior Questionnaire. Child Development 2001, 72, 1394–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, S.P.; Ellis, L.K.; Rothbart, M.K. The structure of temperament from infancy through adolescence. In Advances in research on temperament; Eliasz, A., Angleitner, A., Eds.; Pabst Science: Germany, 2001; pp. 165–182. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart, M.K.; Sheese, B.E.; Posner, M.I. Temperament and emotion regulation. In Handbook of emotion regulation, 2nd ed.; Gross, J.J., Ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, USA, 2014; pp. 305–320. [Google Scholar]

- Anders, T.F.; Goodlin-Jones, B.L. Sleep disorders. In Handbook of Infant Mental Health, 3rd ed; Charles, H.Z., Jr., Ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, USA, 2009; pp. 271–288. [Google Scholar]

- Troxel, W.M.; Trentacosta, C.J.; Forbes, E.E.; Campbell, S.B. Negative emotionality moderates associations among attachment, toddler sleep, and later problem behaviors. Journal of Family Psychology 2013, 27, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkinson, E.; Vetere, A.; Grayson, K. Sleep disruption in young children: The influence of temperament on the sleep patterns of pre-school children. Child: Care, Health and Development 1995, 21, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baukiene, E.; Jusiene, R.; Praninskiene, R.; Lisauskiene, L. The Role of Emotional Reactivity in a Relation between Sleep Problems and the Use of Screen-Based Media among Toddlers and Pre-Schoolers. Early Child Development and Care 2021, 192, 1402–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarı, B.A.; Taner, H.A.; Kaya, Z.T. Screen media exposure in pre-school children in Turkey: the relation with temperament and the role of parental attitudes. The Turkish Journal of Pediatrics 2021, 63, 818–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon-Hacker, A.; Gueron-Sela, N. Maternal Use of Media to Regulate Child Distress: A Double-Edged Sword? Longitudinal Links to Toddlers' Negative Emotionality. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 2020, 23, 400–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, S.; Wang, Z. The Effect of Household Screen Media Experience on Young Children’s Emotion Regulation: The Mediating Role of Parenting Stress. Open Journal of Social Sciences 2023, 11, 243–259. Available online: https://www.scirp.org/pdf/jss_2023072014474338.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2024). [CrossRef]

- Hartshorne, J.K.; Huang, Y.T.; Paredes, P.M.L.; Oppenheimer, K.; Robbins, P.T.; Velasco, M.D. Screen time as an index of family distress. Current Research in Behavioral Sciences 2021, 2, 100023. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2666518221000103 (accessed on 20 November 2024). [CrossRef]

- Pempek, T.A.; McDaniel, B.T. Young children’s tablet use and associations with maternal wellbeing. Journal of Child and Family Studies 2016, 25, 2636–2647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kw, K.; Yk, K.; Jh, K. Associations between parental factors and children’s screen time during the COVID-19 pandemic in South Korea. Child Psychiatry & Human Development 2023, 54, 1749–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDaniel, B.T.; Radesky, J.S. Longitudinal associations between early childhood externalizing behavior, parenting stress, and child media use. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 2020, 23, 384–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gueron-Sela, N.; Shalev, I.; Gordon-Hacker, A.; Egotubov, A.; Barr, R. Screen media exposure and behavioral adjustment in early childhood during and after COVID-19 home lockdown periods. Computers in Human Behavior 2023, 140, 107572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauchli, V.; Sticca, F.; Edelsbrunner, P.; von Wyl, A.; Lannen, P. Are screen media the new pacifiers? The role of parenting stress and parental attitudes for children's screen time in early childhood. Computers in Human Behavior 2024, 152, 108057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radesky, J.S.; Kistin, C.J.; Zuckerman, B.; Nitzberg, K.; Gross, J.; Kaplan-Sanoff, M.; Augustyn, M.; Silverstein, M. Patterns of mobile device use by caregivers and children during meals in fast food restaurants. Pediatrics 2014, 133, e843–e849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Achenbach, T.M.; Rescorla, L.A. Manual for the ASEBA Preschool Forms & Profiles: An Integrated System of Multi-Informant Assessment; ASEBA: Burlington, VT, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach, T.M.; Rescorla, L.A. Multicultural Supplement to the Manual for the ASEBA Preschool Forms & Profiles; University of Vermont Research Center for Children, Youth and Families: Burlington, VT, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Jusienė, R. Raižienė S.; Barkauskienė, R.; Bieliauskaitė, R.; Dervinytė Bongarzoni, A. Ikimokyklinio amžiaus vaikų emocinių ir elgesio sunkumų rizikos veiksniai. Visuomenės sveikata 2007, 39, 46–54. Available online: https://visuomenessveikata.hi.lt/zurnalas/visuomenes-sveikata-2007-nr-439/ (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B.O. Mplus User's Guide, 6th ed.; Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Niiranen, J.; Kiviruusu, O.; Vornanen, R.; Kylliainen, A.; Saarenpaa-Heikkila, O.; Paavonen, E.J. Children’s screen time and psychosocial symptoms at 5 years of age – the role of parental factors. BMC Pediatrics 2024, 24, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rakickiene, L.; Jusiene, R.; Baukiene, E.; Bredokiene, R. Pre-schoolers’ Behavioural and Emotional Problems During the First Quarantine Due to COVID-19 Pandemic: The Role of Parental Distress and Screen Time. Psichologija 2021, 64, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Luo, W.; He, H. Association of Parental Screen Addiction with Young Children’s Screen Addiction: A Chain-Mediating Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofferth, S.L. Media use vs work and play in middle childhood. Social Indicators Research 2009, 93, 127–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).