Submitted:

10 January 2025

Posted:

13 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

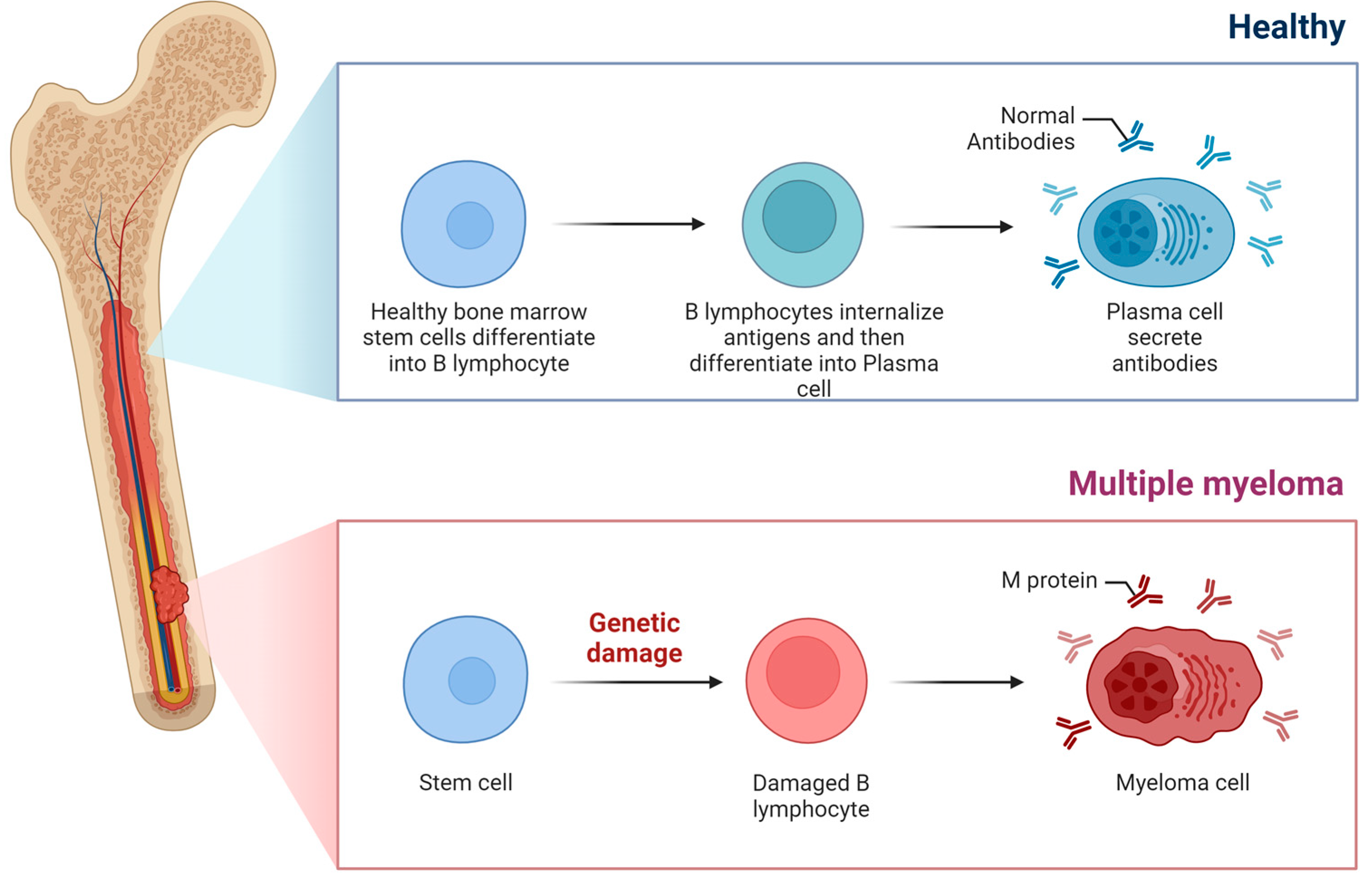

1. Introduction

2. Frailty: Definition, Categorization and Impact on Disease Outcomes

3. Choice of Treatment Regimen in Older MM Patients Ineligible to Receive Transplantation

4. CAR T-Cell Therapy in Older Patients

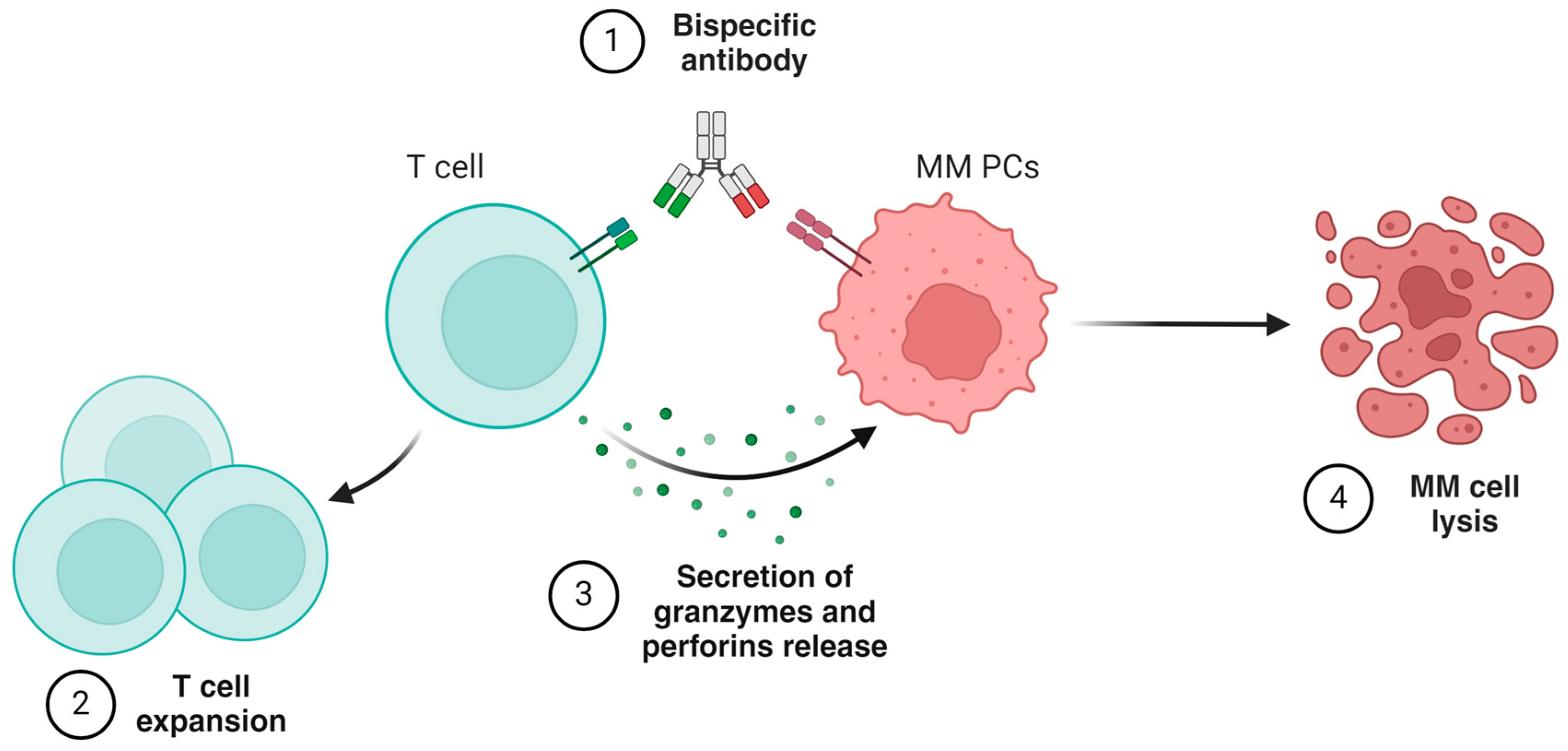

5. Bispecific Antibodies

6. Treatment of Complications and Adverse Events

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kyle, R.A.; Greipp, P.R. Smoldering Multiple Myeloma. N. Engl. J. Med. 1980, 302, 1347–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landgren, O.; Kyle, R.A.; Pfeiffer, R.M.; Katzmann, J.A.; Caporaso, N.E.; Hayes, R.B.; Dispenzieri, A.; Kumar, S.; Clark, R.J.; Baris, D.; et al. Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) consistently precedes multiple myeloma: a prospective study. Blood 2009, 113, 5412–5417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, G.J.; Walker, B.A.; Davies, F.E. The genetic architecture of multiple myeloma. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2012 125 2012, 12, 335–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricot, G. New insights into role of microenvironment in multiple myeloma. Lancet 2000, 355, 248–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antoine-Pepeljugoski, C.; Braunstein, M.J. Management of Newly Diagnosed Elderly Multiple Myeloma Patients. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2019, 21, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolli, N.; Martinelli, G.; Cerchione, C. The Molecular Pathogenesis of Multiple Myeloma. Hematol. Reports 2020, 12, 9054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyle, R.A.; Therneau, T.M.; Rajkumar, S.V.; Offord, J.R.; Larson, D.R.; Plevak, M.F.; Melton, L.J. A Long-Term Study of Prognosis in Monoclonal Gammopathy of Undetermined Significance. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 346, 564–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyle, R.A.; Buadi, F.; Vincent Rajkumar, S. Management of Monoclonal Gammopathy of Undetermined Significance (MGUS) and Smoldering Multiple Myeloma (SMM). Oncology (Williston Park). 2011, 25, 578. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- da Vià, M.C.; Ziccheddu, B.; Maeda, A.; Bagnoli, F.; Perrone, G.; Bolli, N. A Journey Through Myeloma Evolution: From the Normal Plasma Cell to Disease Complexity. HemaSphere 2020, 4, e502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajkumar, S.V.; Dimopoulos, M.A.; Palumbo, A.; Blade, J.; Merlini, G.; Mateos, M.V.; Kumar, S.; Hillengass, J.; Kastritis, E.; Richardson, P.; et al. International Myeloma Working Group updated criteria for the diagnosis of multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol. 2014, 15, e538–e548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolli, N.; Maura, F.; Minvielle, S.; Gloznik, D.; Szalat, R.; Fullam, A.; Martincorena, I.; Dawson, K.J.; Samur, M.K.; Zamora, J.; et al. Genomic patterns of progression in smoldering multiple myeloma. Nat. Commun. 2018 91 2018, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajkumar, S.V.; Kumar, S. Multiple Myeloma: Diagnosis and Treatment. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2016, 91, 101–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajkumar, S.V. Multiple myeloma: 2022 update on diagnosis, risk stratification, and management. Am. J. Hematol. 2022, 97, 1086–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solly, S. Remarks on the pathology of mollities ossium; with cases. Med. Chir. Trans. 1844, 27, 435–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccomi, G.; Fornaciari, G.; Giuffra, V. Multiple myeloma in paleopathology: A critical review. Int. J. Paleopathol. 2019, 24, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaweme, N.M.; Changwe, G.J.; Zhou, F. Approaches and Challenges in the Management of Multiple Myeloma in the Very Old: Future Treatment Prospects. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 612696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimopoulos, M.A.; Moreau, P.; Terpos, E.; Mateos, M. V.; Zweegman, S.; Cook, G.; Delforge, M.; Hájek, R.; Schjesvold, F.; Cavo, M.; et al. Multiple myeloma: EHA-ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up†. Ann. Oncol. Off. J. Eur. Soc. Med. Oncol. 2021, 32, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mina, R.; Bringhen, S.; Wildes, T.M.; Zweegman, S.; Rosko, A.E. Approach to the Older Adult With Multiple Myeloma. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. B. 2019, 500–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facon, T.; Leleu, X.; Manier, S. How I treat multiple myeloma in geriatric patients. Blood 2024, 143, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palumbo, A.; Bringhen, S.; Mateos, M.V.; Larocca, A.; Facon, T.; Kumar, S.K.; Offidani, M.; McCarthy, P.; Evangelista, A.; Lonial, S.; et al. Geriatric assessment predicts survival and toxicities in elderly myeloma patients: an International Myeloma Working Group report. Blood 2015, 125, 2068–2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleber, M.; Ihorst, G.; Terhorst, M.; Koch, B.; Deschler, B.; Wäsch, R.; Engelhardt, M. Comorbidity as a prognostic variable in multiple myeloma: comparative evaluation of common comorbidity scores and use of a novel MM–comorbidity score. Blood Cancer J. 2011 19 2011, 1, e35–e35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engelhardt, M.; Domm, A.S.; Dold, S.M.; Ihorst, G.; Reinhardt, H.; Zober, A.; Hieke, S.; Baayen, C.; Müller, S.J.; Einsele, H.; et al. A concise revised Myeloma Comorbidity Index as a valid prognostic instrument in a large cohort of 801 multiple myeloma patients. Haematologica 2017, 102, 910–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelhardt, M.; Dold, S.M.; Ihorst, G.; Zober, A.; Möller, M.; Reinhardt, H.; Hieke, S.; Schumacher, M.; Wäsch, R. Geriatric assessment in multiple myeloma patients: validation of the International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG) score and comparison with other common comorbidity scores. Haematologica 2016, 101, 1110–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonanad, S.; De la Rubia, J.; Gironella, M.; Pérez Persona, E.; González, B.; Fernández Lago, C.; Arnan, M.; Zudaire, M.; Hernández Rivas, J.A.; Soler, A.; et al. Development and psychometric validation of a brief comprehensive health status assessment scale in older patients with hematological malignancies: The GAH Scale. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2015, 6, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mian, H.S.; Wildes, T.M.; Fiala, M.A. Development of a Medicare Health Outcomes Survey Deficit-Accumulation Frailty Index and Its Application to Older Patients With Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma. JCO Clin. Cancer Informatics 2018, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wildes, T.M.; Tuchman, S.A.; Klepin, H.D.; Mikhael, J.; Trinkaus, K.; Stockerl-Goldstein, K.; Vij, R.; Colditz, G. Geriatric Assessment in Older Adults with Multiple Myeloma. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2019, 67, 987–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosko, A.E.; Huang, Y.; Benson, D.M.; Efebera, Y.A.; Hofmeister, C.; Jaglowski, S.; Devine, S.; Bhatt, G.; Wildes, T.M.; Dyko, A.; et al. Use of a comprehensive frailty assessment to predict morbidity in patients with multiple myeloma undergoing transplant. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2019, 10, 479–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ludwig, H.; Delforge, M.; Facon, T.; Einsele, H.; Gay, F.; Moreau, P.; Avet-Loiseau, H.; Boccadoro, M.; Hajek, R.; Mohty, M.; et al. Prevention and management of adverse events of novel agents in multiple myeloma: a consensus of the European Myeloma Network. Leuk. 2018 327 2018, 32, 1542–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larocca, A.; Bonello, F.; Gaidano, G.; D’Agostino, M.; Offidani, M.; Cascavilla, N.; Capra, A.; Benevolo, G.; Tosi, P.; Galli, M.; et al. Dose/schedule-adjusted Rd-R vs continuous Rd for elderly, intermediate-fit patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Blood 2021, 137, 3027–3036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manier, S.; Corre, J.; Hulin, C.; Laribi, K.; Araujo, C.; Pica, G.-M.; Touzeau, C.; Godmer, P.; Slama, B.; Karlin, L.; et al. A Dexamethasone Sparing-Regimen with Daratumumab and Lenalidomide in Frail Patients with Newly-Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma: Efficacy and Safety Analysis of the Phase 3 IFM2017-03 Trial. Blood 2022, 140, 1369–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larocca, A.; Cani, L.; Bertuglia, G.; Bruno, B.; Bringhen, S. New Strategies for the Treatment of Older Myeloma Patients. Cancers 2023, 15, 2693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hulin, C.; Facon, T.; Rodon, P.; Pegourie, B.; Benboubker, L.; Doyen, C.; Dib, M.; Guillerm, G.; Salles, B.; Eschard, J.P.; et al. Efficacy of melphalan and prednisone plus thalidomide in patients older than 75 years with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: IFM 01/01 trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 3664–3670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durie, B.G.M.; Hoering, A.; Abidi, M.H.; Rajkumar, S.V.; Epstein, J.; Kahanic, S.P.; Thakuri, M.; Reu, F.; Reynolds, C.M.; Sexton, R.; et al. Bortezomib with lenalidomide and dexamethasone versus lenalidomide and dexamethasone alone in patients with newly diagnosed myeloma without intent for immediate autologous stem-cell transplant (SWOG S0777): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2017, 389, 519–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durie, B.G.M.; Hoering, A.; Sexton, R.; Abidi, M.H.; Epstein, J.; Rajkumar, S.V.; Dispenzieri, A.; Kahanic, S.P.; Thakuri, M.C.; Reu, F.J.; et al. Longer term follow-up of the randomized phase III trial SWOG S0777: bortezomib, lenalidomide and dexamethasone vs. lenalidomide and dexamethasone in patients (Pts) with previously untreated multiple myeloma without an intent for immediate autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT). Blood Cancer J. 2020 105 2020, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, E.K.; Laubach, J.P.; Yee, A.J.; Chen, T.; Huff, C.A.; Basile, F.G.; Wade, P.M.; Paba-Prada, C.E.; Ghobrial, I.M.; Schlossman, R.L.; et al. A phase 2 study of modified lenalidomide, bortezomib and dexamethasone in transplant-ineligible multiple myeloma. Br. J. Haematol. 2018, 182, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Donnell, E.K.; Laubach, J.P.; Yee, A.J.; Redd, R.; Huff, C.A.; Basile, F.; Wade, P.M.; Paba-Prada, C.E.; Ghobrial, I.M.; Schlossman, R.L.; et al. Updated Results of a Phase 2 Study of Modified Lenalidomide, Bortezomib, and Dexamethasone (RVd-lite) in Transplant-Ineligible Multiple Myeloma. Blood 2019, 134, 3178–3178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facon, T.; Dimopoulos, M.-A.; Leleu, X.P.; Beksac, M.; Pour, L.; Hájek, R.; Liu, Z.; Minarik, J.; Moreau, P.; Romejko-Jarosinska, J.; et al. Isatuximab, Bortezomib, Lenalidomide, and Dexamethasone for Multiple Myeloma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facon, T.; Kumar, S.K.; Plesner, T.; Orlowski, R.Z.; Moreau, P.; Bahlis, N.; Basu, S.; Nahi, H.; Hulin, C.; Quach, H.; et al. Daratumumab, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone versus lenalidomide and dexamethasone alone in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (MAIA): overall survival results from a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, 1582–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Facon, T.; Cook, G.; Usmani, S.Z.; Hulin, C.; Kumar, S.; Plesner, T.; Touzeau, C.; Bahlis, N.J.; Basu, S.; Nahi, H.; et al. Daratumumab plus lenalidomide and dexamethasone in transplant-ineligible newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: frailty subgroup analysis of MAIA. Leuk. 2021 364 2022, 36, 1066–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durie, B.G.M.; Kumar, S.K.; Usmani, S.Z.; Nonyane, B.A.S.; Ammann, E.M.; Lam, A.; Kobos, R.; Maiese, E.M.; Facon, T. Daratumumab-lenalidomide-dexamethasone vs standard-of-care regimens: Efficacy in transplant-ineligible untreated myeloma. Am. J. Hematol. 2020, 95, 1486–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mateos, M.V.; Nahi, H.; Legiec, W.; Grosicki, S.; Vorobyev, V.; Spicka, I.; Hungria, V.; Korenkova, S.; Bahlis, N.; Flogegard, M.; et al. Subcutaneous versus intravenous daratumumab in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (COLUMBA): a multicentre, open-label, non-inferiority, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2020, 7, e370–e380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, K.C.; Landgren, O.; Arend, R.C.; Chou, J.; Jacobs, I.A. Humanistic and economic impact of subcutaneous versus intravenous administration of oncology biologics. Futur. Oncol. 2019, 15, 3267–3281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonseca, R.; Facon, T.; Hashim, M.; Nair, S.; He, J.; Ammann, E.; Lam, A.; Wildgust, M.; Kumar, S. Impact of Treatment Sequencing on Overall Survival in Patients with Transplant-Ineligible Newly Diagnosed Myeloma. Oncologist 2023, 28, e263–e269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mateos, M.-V.; Dimopoulos, M.A.; Cavo, M.; Suzuki, K.; Jakubowiak, A.; Knop, S.; Doyen, C.; Lucio, P.; Nagy, Z.; Kaplan, P.; et al. Daratumumab plus Bortezomib, Melphalan, and Prednisone for Untreated Myeloma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 518–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mateos, M.V.; Dimopoulos, M.A.; Cavo, M.; Suzuki, K.; Knop, S.; Doyen, C.; Lucio, P.; Nagy, Z.; Pour, L.; Grosicki, S.; et al. Daratumumab Plus Bortezomib, Melphalan, and Prednisone Versus Bortezomib, Melphalan, and Prednisone in Transplant-Ineligible Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma: Frailty Subgroup Analysis of ALCYONE. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2021, 21, 785–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- San-Miguel, J.; Avet-Loiseau, H.; Paiva, B.; Kumar, S.; Dimopoulos, M.A.; Facon, T.; Mateos, M.V.; Touzeau, C.; Jakubowiak, A.; Usmani, S.Z.; et al. Sustained minimal residual disease negativity in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma and the impact of daratumumab in MAIA and ALCYONE. Blood 2022, 139, 492–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateos, M.V.; Cavo, M.; Blade, J.; Dimopoulos, M.A.; Suzuki, K.; Jakubowiak, A.; Knop, S.; Doyen, C.; Lucio, P.; Nagy, Z.; et al. Overall survival with daratumumab, bortezomib, melphalan, and prednisone in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (ALCYONE): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2020, 395, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlogie, B.; Smith, L.; Alexanian, R. Effective Treatment of Advanced Multiple Myeloma Refractory to Alkylating Agents. N. Engl. J. Med. 1984, 310, 1353–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajkumar, S.V.; Blood, E.; Vesole, D.; Fonseca, R.; Greipp, P.R. Phase III Clinical Trial of Thalidomide Plus Dexamethasone Compared With Dexamethasone Alone in Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma: A Clinical Trial Coordinated by the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006, 24, 431–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facon, T.; Mary, J.Y.; Pégourie, B.; Attal, M.; Renaud, M.; Sadoun, A.; Voillat, L.; Dorvaux, V.; Hulin, C.; Lepeu, G.; et al. Dexamethasone-based regimens versus melphalan-prednisone for elderly multiple myeloma patients ineligible for high-dose therapy. Blood 2006, 107, 1292–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stege, C.A.M.; Nasserinejad, K.; van der Spek, E.; Bilgin, Y.M.; Kentos, A.; Sohne, M.; van Kampen, R.J.W.; Ludwig, I.; Thielen, N.; Durdu-Rayman, N.; et al. Ixazomib, Daratumumab, and Low-Dose Dexamethasone in Frail Patients With Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma: The Hovon 143 Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 2758–2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chim, C.S.; Kumar, S.K.; Orlowski, R.Z.; Cook, G.; Richardson, P.G.; Gertz, M.A.; Giralt, S.; Mateos, M. V.; Leleu, X.; Anderson, K.C. Management of relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma: novel agents, antibodies, immunotherapies and beyond. Leuk. 2018 322 2017, 32, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonneveld, P. Management of multiple myeloma in the relapsed/refractory patient. Hematology 2017, 2017, 508–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quach, H.; Nooka, A.; Samoylova, O.; Venner, C.P.; Kim, K.; Facon, T.; Spencer, A.; Usmani, S.Z.; Grosicki, S.; Suzuki, K.; et al. Carfilzomib, dexamethasone and daratumumab in relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma: results of the phase III study CANDOR by prior lines of therapy. Br. J. Haematol. 2021, 194, 784–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yong, K.; Delforge, M.; Driessen, C.; Fink, L.; Flinois, A.; Gonzalez-McQuire, S.; Safaei, R.; Karlin, L.; Mateos, M.V.; Raab, M.S.; et al. Multiple myeloma: patient outcomes in real-world practice. Br. J. Haematol. 2016, 175, 252–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.; Qiu, L.; Usmani, S.; et al. Consensus guidelines and recommendations for the management and response assessment of chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy in clinical practice for relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma: a report from the International Myeloma Working Group Immunotherapy Committee. Lancet Oncol. Erratum in: Lancet Oncol. 2024, 25, e336. 10.1016/S1470-2045(24)00337-1. 2024, 25, e374–e387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Otero, P.; San Miguel, J.F. Post-CAR-T Cell Therapy (Consolidation and Relapse): Multiple Myeloma. EBMT/EHA CAR-T Cell Handb. 2022, 173–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.A.; Dima, D.; Ahmed, N.; DeJarnette, S.; McGuirk, J.; Jia, X.; Raza, S.; Khouri, J.; Valent, J.; Anwer, F.; et al. Impact of Frailty on Outcomes after Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cell Therapy for Patients with Relapsed/Refractory Multiple Myeloma. Transplant. Cell. Ther. 2024, 30, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajeeve, S.; Usmani, S.Z. How Old is Too Old for CAR-T Cell Therapies in Multiple Myeloma? Transplant. Cell. Ther. 2023, 29, 343–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munshi, N.C.; Anderson, L.D.; Shah, N.; Madduri, D.; Berdeja, J.; Lonial, S.; Raje, N.; Lin, Y.; Siegel, D.; Oriol, A.; et al. Idecabtagene Vicleucel in Relapsed and Refractory Multiple Myeloma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 705–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdeja, J.G.; Madduri, D.; Usmani, S.Z.; Jakubowiak, A.; Agha, M.; Cohen, A.D.; Stewart, A.K.; Hari, P.; Htut, M.; Lesokhin, A.; et al. Ciltacabtagene autoleucel, a B-cell maturation antigen-directed chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (CARTITUDE-1): a phase 1b/2 open-label study. Lancet 2021, 398, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhtar, O.S.; Sheeba, B.A.; Azad, F.; Alessi, L.; Hansen, D.; Alsina, M.; Baz, R.; Shain, K.; Grajales Cruz, A.; Castaneda Puglianini, O.; et al. Safety and efficacy of anti-BCMA CAR-T cell therapy in older adults with multiple myeloma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reyes, K.R.; Huang, C.Y.; Lo, M.; Arora, S.; Chung, A.; Wong, S.W.; Wolf, J.; Olin, R.L.; Martin, T.; Shah, N.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of BCMA CAR-T Cell Therapy in Older Patients With Multiple Myeloma. Transplant. Cell. Ther. 2023, 29, 350–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neelapu, S.S.; Jacobson, C.A.; Oluwole, O.O.; Munoz, J.; Deol, A.; Miklos, D.B.; Bartlett, N.L.; Braunschweig, I.; Jiang, Y.; Kim, J.J.; et al. Outcomes of older patients in ZUMA-1, a pivotal study of axicabtagene ciloleucel in refractory large B-cell lymphoma. Blood 2020, 135, 2106–2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yates, S.J.; Cursio, J.F.; Artz, A.; Kordas, K.; Bishop, M.R.; Derman, B.A.; Kosuri, S.; Riedell, P.A.; Kline, J.; Jakubowiak, A.; et al. Optimization of older adults by a geriatric assessment–guided multidisciplinary clinic before CAR T-cell therapy. Blood Adv. 2024, 8, 3785–3797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Otero P, Usmani S, Cohen AD, International Myeloma Working Group immunotherapy committee consensus guidelines and recommendations for optimal use of T-cell-engaging bispecific antibodies in multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol. Erratum in Lancet Oncol. 2024, 25, e284. 10.1016/S1470-2045(24)00288-2. 2024, 25, e205–e216. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellerman, D. Bispecific T-cell engagers: Towards understanding variables influencing the in vitro potency and tumor selectivity and their modulation to enhance their efficacy and safety. Methods 2019, 154, 102–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tacchetti, P.; Barbato, S.; Mancuso, K.; Zamagni, E.; Cavo, M. Bispecific Antibodies for the Management of Relapsed/Refractory Multiple Myeloma. Cancers 2024, 16, 2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieterle, M.P.; Mostufi-Zadeh-Haghighi, G.; Kus, J.W.; Wippel, C.; Brugger, Z.; Miething, C.; Wäsch, R.; Engelhardt, M. Safe and successful teclistamab treatment in very elderly multiple myeloma (MM) patients: a case report and experience from a total of three octogenarians. Ann Hematol 2023, 102, 3639–3641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jourdes, A.; Cellerin, E.; Touzeau, C.; et al. Characteristics and incidence of infections in patients with multiple myeloma treated by bispecific antibodies: a national retrospective study. Clin Microbiol Infect 2024, 30, 764–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terpos, E.; Mikhael, J.; Hajek, R.; et al. (2021) Management of patients with multiple myeloma beyond the clinical-trial setting: understanding the balance between efficacy, safety and tolerability, and quality of life. Blood Cancer J 2021, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohty, B.; El-Cheikh, J.; Yakoub-Agha, I.; Moreau, P.; Harousseau, J.L.; Mohty, M. Peripheral neuropathy and new treatments for multiple myeloma: background and practical recommendations. Haematologica 2010, 95, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.S.; Yen, C.H.; Hsu, C.M.; Hsiao, H.H. (2021) Management of Myeloma Bone Lesions. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 3389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mach, S.; Javed, S.; Chen, G.H.; Huh, B.K. Peripheral Nerve Stimulation for Back Pain in Patients With Multiple Myeloma as Bridge Therapy to Radiation Treatment: A Case Series. Neuromodulation 2023, 26, 694–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mian, H.S.; Wildes, T.; Vij, R.; Major, A.; Fiala, M.A. Need for Dynamic Frailty Risk Assessment Among Older Adults with Multiple Myeloma: A Population-Based Cohort Study. Blood 2022, 140, 423–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, G.; Pawlyn, C.; Royle, K.-L.; et al. Dynamic Frailty Assessment in Transplant Non-Eligible Newly Diagnosed Myeloma Patients: Initial Data from UK Myeloma Research Alliance (UK-MRA) Myeloma XIV (FiTNEss): A Frailty-Adjusted Therapy Study. Blood 2023, 142, 4748–4748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau, P.; Garfall, A.L.; van de Donk, N.W.C.J.; et al. Teclistamab in Relapsed or Refractory Multiple Myeloma. N Engl J Med 2022, 387, 495–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usmani, S.Z.; Garfall, A.L.; van de Donk, N.W.C.J.; et al. Teclistamab, a B-cell maturation antigen × CD3 bispecific antibody, in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (MajesTEC-1): a multicentre, open-label, single-arm, phase 1 study. Lancet 2021, 398, 665–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raje, N.S.; Leleu, X.P.; Lesokhin, A.M.; Mohty, M.; Nooka, A.K.; Leip, E.; Conte, U.; Viqueira, A.; Manier, S. Efficacy and safety of elranatamab by age and frailty in patients (pts) with relapsed/refractory multiple (RRMM): A subgroup analysis from MagnetisMM-3. J Clin Oncol 2023, 41, 8040–8040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesokhin, A.M.; Tomasson, M.H.; Arnulf, B.; et al. Elranatamab in relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma: phase 2 MagnetisMM-3 trial results. Nat Med 2023 299 2023, 29, 2259–2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.C.; Bumma, N.; Richter, J.R.; et al. LINKER-MM1 study: Linvoseltamab (REGN5458) in patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol 2023, 41, 8006–8006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagannath, S.; Richter, J.; Dhodapkar, M.V.; et al. Patterns of Response to 200 Mg Linvoseltamab in Patients with Relapsed/Refractory Multiple Myeloma: Longer Follow-Up of the Linker-MM1 Study. Blood 2023, 142, 4746–4746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar, N.; Mateos, M.V.; Ribas, P.; et al. Alnuctamab (ALNUC; BMS-986349; CC-93269), a 2+1 B-Cell Maturation Antigen (BCMA) × CD3 T-Cell Engager (TCE), Administered Subcutaneously (SC) in Patients (Pts) with Relapsed/Refractory Multiple Myeloma (RRMM): Updated Results from a Phase 1 First-in-Human Clinical Study. Blood 2023, 142, 2011–2011. [Google Scholar]

- D’souza, A.; Shah, N.; Rodriguez, C.; et al. A Phase I First-in-Human Study of ABBV-383, a B-Cell Maturation Antigen × CD3 Bispecific T-Cell Redirecting Antibody, in Patients With Relapsed/Refractory Multiple Myeloma. J Clin Oncol 2022, 40, 3576–3586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voorhees, P.M.; D’Souza, A.; Weisel, K.; et al. A Phase 1 First-in-Human Study of Abbv-383, a BCMA × CD3 Bispecific T-Cell-Redirecting Antibody, As Monotherapy in Patients with Relapsed/Refractory Multiple Myeloma. Blood 2022, 140, 4401–4404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suvannasankha, A.; Kapoor, P.; Pianko, M.J.; et al. Abstract CT013: Safety and efficacy from the phase 1/2 first-in-human study of REGN5459, a BCMA×CD3 bispecific antibody with low CD3 affinity, in patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma. Cancer Res 2023, 83, CT013–CT013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasche, L.; Schinke, C.; Touzeau, C.; et al. Long-Term Efficacy and Safety Results From the Phase 1/2 MonumenTAL-1 Study of Talquetamab, a GPRC5D×CD3 Bispecific Antibody, in Patients With Relapsed/Refractory Multiple Myeloma (RRMM). Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk 2024, 24, S240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlo-Stella, C.; Mazza, R.; Manier, S.; et al. RG6234, a GPRC5DxCD3 T-Cell Engaging Bispecific Antibody, Is Highly Active in Patients (pts) with Relapsed/Refractory Multiple Myeloma (RRMM): Updated Intravenous (IV) and First Subcutaneous (SC) Results from a Phase I Dose-Escalation Study. Blood 2022, 140, 397–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trudel, S.; Cohen, A.D.; Krishnan, A.Y.; et al. Cevostamab Monotherapy Continues to Show Clinically Meaningful Activity and Manageable Safety in Patients with Heavily Pre-Treated Relapsed/Refractory Multiple Myeloma (RRMM): Updated Results from an Ongoing Phase I Study. Blood 2021, 138, 157–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.K.; Jacobus, S.J.; Cohen, A.D.; et al. Carfilzomib or bortezomib in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone for patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma without intention for immediate autologous stem-cell transplantation (ENDURANCE): a multicentre, open-label, phase 3, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2020, 21, 1317–1330. [Google Scholar]

- Facon, T.; Lee, J.H.; Moreau, P.; et al. Carfilzomib or bortezomib with melphalan-prednisone for transplant-ineligible patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Blood 2019, 133, 1953–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usmani, S.Z.; Nahi, H.; Legiec, W.; et al. Final analysis of the phase III non-inferiority COLUMBA study of subcutaneous versus intravenous daratumumab in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. Haematologica 2022, 107, 2408–2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, P.G.; Kumar, S.K.; Masszi, T.; et al. Final Overall Survival Analysis of the TOURMALINE-MM1 Phase III Trial of Ixazomib, Lenalidomide, and Dexamethasone in Patients With Relapsed or Refractory Multiple Myeloma. J Clin Oncol 2021, 39, 2430–2442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facon, T.; Niesvizky, R.; Mateos, M.V.; et al. Efficacy and safety of carfilzomib-based regimens in frail patients with relapsed and/or refractory multiple myeloma. Blood Adv 2020, 4, 5449–5459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berdeja, J.G.; Raje, N.S.; Siegel, D.S.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Idecabtagene Vicleucel (ide-cel, bb2121) in Elderly Patients with Relapsed and Refractory Multiple Myeloma: KarMMa Subgroup Analysis. Blood 2020, 136, 16–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, H.; Terpos, E.; van de Donk, N.; et al. Prevention and management of adverse events during treatment with bispecific antibodies and CAR T cells in multiple myeloma: a consensus report of the European Myeloma Network. Lancet Oncol. 2023, 24, e255–e269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, G.; Pawlyn, C.; Cairns, D.A.; Jackson, G.H. Defining FiTNEss for treatment for multiple myeloma. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2022, 3, e729–e730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Targets | BsAbs | Study | Patients number | Dosing schedule/efficacy (ref.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BCMA | Teclistamab (JNJ-64007957) | Phase 1/2 MajesTEC-1 trial (NCT04557098); (NCT03145181) | 165 Patients≥75 yr: 24 (14.5%). |

subcutaneous injection0.06mg-0.3mg-1.5mg/Kg once weekly.Deep and durable response [77,78]. |

| Elranatab (PF-06863135) | Phase 2 MagnetisMM-3 trial (NCT04649359cohort A) | 123 Patients≥75 yr: 24 (19.5%). |

subcutaneous injection12-32-76 mg once weekly.Good efficacy and safety [79,80] | |

| Linvoseltamab (REGN5458) | Phase 1/2 LINKER-MM1 trial (NCT03761108) | 200 mg.: 117 Patients≥75 yr: 31 (26.4%). |

intravenous injection 5-25-200 mg once weekly.Consistent efficacy across high-risk subgroups and induced responses in pts who progressed on 50 ng[81,82]. | |

| Alnuctamab (CC-93269) | Phase 1 trial (NCT03486067) | 73 Patients≥75 yr: n.a. |

target dose:subcutaneous injection 30 mg one weekly (cycle 1 to 3); every other week (cycle 4 to 6); every 4 weeks from cycle 7. Favorable safety profile[83]. | |

| ABBV-383 (TNB-383B) | Phase 1 trial (NCT03933735) | 124 Patients≥75 yr: n.a. |

intravenous injection 60 mg every three weeks. Good tolerance and durable response [84,85]. | |

| REGN-5459 | Phase 1/2 trial (NCT04083534) | 43 Patients≥75 yr: n.a. |

target dose: intravenous injection 480 mg once weekly. Acceptable safety/tolerability[86]. | |

| GPRC5D | Talquetamab | Phase 1/2 MonumenTAL-1 trial. (NCT03399799); (NCT04634552) | 375 Patients≥75 yr: n.a. |

subcutaneous injection 0.4 mg/kg once weekly or 0.8 mg/kg every other week, with step-up doses. The safety profile was consistent with previous results[87]. |

| Forimtamig (RG6234) | Phase 1 trial (NCT04557150) | 108 Patients≥75 yr: n.a. |

intravenous injection dose range: 6-10000µg (51 pts) subcutaneous injection dose range: 30-7200µg (57 pts).high response rate across all tested doses for both IV and SC dosing[88]. | |

| FcRH5 | Cevostamab | Phase 1 trial (NCT03275103) | 160 Patients≥75 yr: n.a. |

intravenous infusion in 21-day cycles. In the single step-up cohorts, the step dose (0.05-3.6mg) is given on C1 Day (D) 1 and the target dose (0.15-198mg) on C1D8. In the double step-up cohorts, the step doses are given on C1D1 (0.3-1.2mg) and C1D8 (3.6mg), and the target dose (60-160mg) on C1D15. In both regimens, the target dose is given on D1 of subsequent cycles. Cevostamab is continued for a total of 17 cycles, unless progressive disease or unacceptable toxicity occurs. Clinically meaningful activity and no increase in CRS rate[89]. |

| Newly diagnosed patients | |

|---|---|

| MAIA study [38]. | n= 737 pts (D-Rd, n = 368; Rd, n = 369) 396 non-frail pts (D-Rd, 196 ; Rd, 200 ) 341 frail pts(D-Rd, 172 ; Rd, 169 ) Clinical benefit irrespective of frailty in newly diagnosed, transplant-ineligible patients |

| ALCYONE[47]. | n=706 pts (D-VMP, n = 350; VMP, n = 356) 391 non frail pts (D-VMP, 187; VMP, 204) 315 frail pts (D-VMP, 163; VMP,152) Clinical benefit of D-VMP irrespective of frailty in newly diagnosed transplant-ineligible patients enrolled in ALCYONE, regardless of frailty status. |

| SWOG S0777[33,34] | n=460 pts (VRd, n = 235; Rd, n = 225) 91/235 pts in the VRd arm were aged >65 years Addition of bortezomib to standard lenalidomide/dexamethasone clinically advantageous irrespective of age in previously untreated patients. |

| ENDURANCE[90] | n= 1087 pts (VRd, n = 542; KRd, n = 545) VRd lite in older pts [35,36] Addition of Carfilzomib to VRd in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma patients not more effective and characterized by higher toxicity. A modified VRd treatment effective in >65 years old, newly diagnosed, transplant-ineligible patients |

| CLARION [91] | n=955 pts (KMP, n = 478; VMP, n = 477). KMP not more effective than VMP in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma patients ineligible for transplant, irrespective of age. |

| HOVON 143 [51] | n= 65 frail newly diagnosed multiple myeloma pts, treated with Ixa-Dara-Dex. High response rate but toxicity and early mortality. |

| Treatment options at relapse | |

| COLUMBA [92] | n=522 pts (DARA SC, n=263; DARA IV, n=259) Similar effectiveness of daratumumab upon subcutaneous or intravenous administration in relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. |

| TOURMALINE[93] | n= 722 (IRd, n = 360; Rd, n = 362) Improved PFS upon treatment with IRd than with Rd in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. |

| ASPIRE-ENDEAVOR-ARROW [94] | ASPIRE n=792 pts (KRd27, n= 396 vs Rd n= 396) ENDEAVOR n=929 pts (Kd56, n= 464vs Vd, n= 465) ARROW (once-weekly) n=478 pts (Kd70, n=240 vs Kd27, n=238) Efficacy and safety were consistent across frailty subgroups with KRd27, Kd56, and weekly Kd70 in relapsed and/or refractory MM. |

| KarMMa study[95] | CAR T-Therapy (n=128; n=45 ≥65 years; n=20 ≥70 years) Durable responses and manageable safety profile in patients with relapsed/recurrent multiple myeloma aged ≥65 years and ≥70 years. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).