1. Introduction

Horticulture is one of the sectors that has been chosen by the Government of Botswana as a priority for agricultural diversification and employment creation. The sector has also been chosen for value chain development as a means of supporting private sector development through which more value could be unlocked [

1]. Horticultural products are an important part of a healthy diet [Amao, 2018 [

2,

3], with [

4] estimating that insufficient consumption of fruit and vegetables cuase 14% of global deaths. As a result, government has instituted several support programmes towards the development of the sector. Despite government efforts to develop the horticulture sector, the sector is still at an infant stage and undeveloped. However, there are opportunities within the value chain which when siezed could develop the horticultural value chain.

Government has over the years instituted several programmes to promote horticultural production in the country. At production level some of these programmes include Special Integrated Support Programme for Arable Agriculture Development (ISPAAD) [

5] and the current Impact Accelerator Subsidy (IAS) [

6]which became operational in 2021 as a response to Covid 19 pandemic. Government also instituted programmes at the market level, such as the construction of fresh produce markets (FPMs) and the Botswana Horticultural Market (BHM) to address farmers’ challenges of lack of market access. Additionally, the government instituted regulations at the border with the view of protecting the local horticultural industry from stiff competition imposed by foreign products, especially from South Africa. These regulations include the import controls through the Control of Goods, Prices, and Other Charges Act [

7]. In January 2022, an import ban was imposed on 16 selected vegetable crops and was scheduled to run for 2 years up to December 2023. In July 2023 the ban was extended to December 2025 and additional crops introduced to include 32 vegetables. Moreover, government has instituted the Economic Inclusion Act No. 26 of 2021 [

8] whose objectives are to increase citizen participation in the economy as part of implementation of the Citizen Economic Empowerment Policy (CEEP). In horticulture the Act provides market access to horticulture producers through public procurement as producers can enter into contracts to supply government institutions such as schools, hospitals and others [

8]. Government has also developed a National Horticulture Strategy with technical assistance from the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) of the United Nations (UN). The main objective of this strategy is to guide the development of the horticulture sub-sector [

9].

Government efforts to develop the non-traditional sub-sectors such as the horticulture are starting to bear fruits, with production level for horticultural products rising from 47,539.38 metric tonnes in 2015/16 to 75,448.92 metric tonnes (58%) in 2020/21. The number of farms has also increased from 880 to 1,292 (47%) and area planted increased from 2,653 to 3,360.88 (26%) hectares during the same period [

8]). According to the Department of Crop Production (Horticulture Production Trends), although there was a negative growth between 2009 and 2012, horticulture production has shown a steady growth when measured year-on-year basis. This increase is attributed to improved technology uptake, increased market opportunities, and increased production under protected environment [

10].

Despite this increase in local production, the country still imports substantial amounts of horticultural products. For example, between 2012 and 2021, horticultural import bill rose from BWP (BWP – Botswana Pula, the currency of Botswana which was equivalent to 13,75 USD at the time of writing) 475 million to BWP 1.2 billion (51%), while the quantities imported increased by 35% from 70,170 metric tonnes to 94,954 metric tonnes over the same period [

11]. However, the import bill fell by 50% from BWP1.2 billion to BWP817 million between 2021 and 2022, while the imported quantities fell by 60% from 105,053 tonnes to 43,759 tonnes mainly as a result of the import ban imposed on selected horticultural crops [

11].

While there has been notable improvements in the horticulture sector, the horticultural value chain in Botswana, similar to other developing countries is faced with several constraints which impedes its growth. These constraints hinder chain actors to take opportunities presented by the market as a result of urbanisation and supermarket revolution leading to increased demand for vegetables [

12].

One of the key constraints faced by horticulture farmers in developing countries is lack market access [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. The market access issue is made worse by stringent super requirements which smallholder farmers are unable to meet [

21]. Lack of production contracts between farmers and buyers also worsne the market access problem [

19]. Constraints related to climatic conditions include increased incidence and severity of extreme weather events like droughts, floods, fires, frost etc [

20,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. Additional constraints inlcude lack of technical skills leading to improper agronomic practices such as poor post-harvest handling techniques, unscientific application of fertilisers and ineffective control of pests and diseases [

13,

17,

20,

21,

25,

27]. Lack of technical skills results from inadequate provision of extension services, especially in marketing and financial management [

28].

Horticultural farmers in developing countries also have to contend with inadequate infrastructure such as marketing, cold storage and processing facilities [

13,

14,

15,

17,

19]). Access to credit is another constriant which limits farmers’ ability to adopt modern technologies such as production under protected environment (net shade, greenhouse gas, hydroponics, tunnels) [

29,

30,

31,

32]. The constraints related to soils include degradation, poor soil fertility and moisture [

12]. In some countries land is a constraint [

13]), while in others water is a big constraint [

18,

33]. Additionally, [

14,

19] identified inadequate support services as a major constraint to horticultural production.

Additional challenges include post-harvest losses which are very high due to lack of suitable post-harvest techniques and processing, cold chain technologies and infrastructure which remain largely non-existent [

2,

34]. For instance, [

34,

35,

36]) found that productivity gap could be in excess of 50% even in areas that could be considered endowed biophysically and institutionally. Unregulated and ineffective seed sector for horticulture compared to staple crops is another constraint facing the horticulture value chain leading to low productivity [

12,

19].

Food safety is of high concern in horticulture as supermarkets are starting to pay attention to maximum residue limits and traceability. In Southern Africa there are a few standards such as those related to maximum residues limits and if standards are present, they are mostly implemented or adhered for overseas exports [

12]. Quality standards and certifcation have emerged to ensure food safety [

2].

These multitudes of constraints limits productivity growth and the development of the horticultural value chains. Despite the many challenges facing the horticultural value chain there are several of opportunities along the value chain which include new channels for horticultural produce Urbanisation and supermarket revolution has led to increased demand for fresh vegetables and processed products as consumption patterns change due to increased income [

21].

Similar to other developing countries, the horticulture sector in Botswana faces several constraints which impedes its growth. These constraints are more pronounced especially at primary production, and processing stages. Several studies [

37,

38,

39,

40] have identified constraints to the development of the horticulture sector with emphasis on primary production, at the expense of other value chain activities. Thus, none of these studies took a holistic view of the constraints and opportunities along the value chain. Additionally, the studies were conducted some time back with last one being conducted in 2015. Since then, several changes have taken place such as introduction of the import ban and the collapse of the FPMs and central market. These changes are expected to have introduced new constraints and opportunities in the horticulture value chain. Therefore, the main objective of this study was to identify constraints as well as opportunities along the Botswana horticultural value chain. The study uses the SWOT analysis to determine the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats with the view of identifying constraints and opportunities along the horticulturtal value chain in Botswana using data collected in 2023. As a priority sector for economic diversfication and employment creation it is important that the performance of the horticultural sector is enhanced and this can only be possible if constrinats beldveling the sector are indentified and dealt with, while opportunities are taken up.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Study Area

The study was carried out in the nine (9) out of ten (10) administrative districts of Botswana: Central; Chobe; Gantsi; Kgatleng; Kweneng; South East; Southern; Ngamiland and North East. The Kalahari district was excluded in the sample because there was no vegetable production due to its climatic conditions and poor soils. The study is part of a larger one on “Botswana Horticulture Value Chain Mapping and Analysis”.

2.2. Data and Data Collection Methods

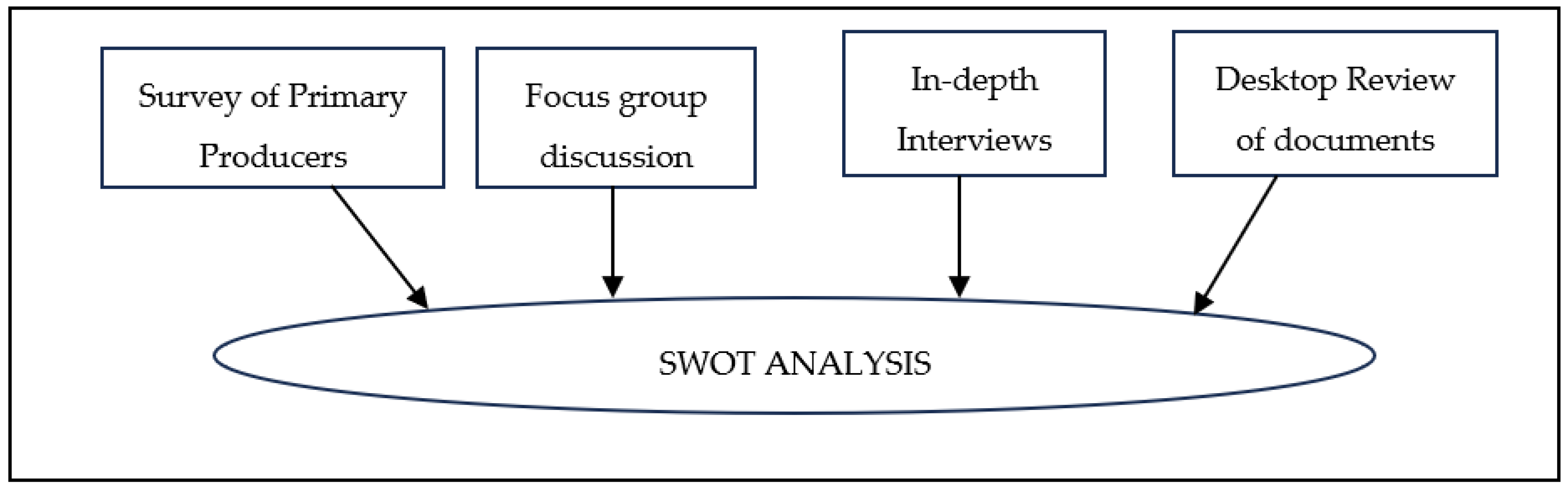

The data collection for the study was carried out between June and August in 2023 from both the primary and secondary sources using mixed method approaches. The main use of this data was to construct the SWOT analysis of the horticultural value chain as outlined in

Figure 1.

2.2.1. Survey

Primary data was collected through survey of farmers who planted the top five vegetables (cabbage, tomatoes, potatoes, onions, and rape). A total of 900 (70%) out of 1,292 farmers planted the top five vegetables in 2021/22 across the country. Out of 900 farmers who planted the top five vegetables, 102 farmers were randomly selected in the nine (9) districts mentioned above. The selection of the 102 farmers was based on the number of farmers in each district and ensuring that in each district at least 10 percent of the farmers are selected.

A questionnaire was administered to selected farmers in each sampled district and it sought to characterise primary producers in terms of their farm size, technology employed, and markets. Additionally, data collected included their strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats (SWOT) to determine leverage points which could be exploited to enhance the efficiency of the chain as well as weak points which need to be improved for better chain performance.

2.2.2. In-Depth Interviews

In-depth interviews were held with value chain actors across the horticulture value chain, starting from input suppliers to retailers as well as support institutions (

Table 1). At input level, interviews were held with nine (8) input suppliers and the interviews sought to find out the sources of inputs as well as the challenges they encounter in supplying the inputs. At the wholesale level the data collected was on where they source their products and any value addition they perform as well as the constraints they face and opportunities available. At processing level in-depth interviews were conducted with the National Agro Processing (NAPRO) as well as street vendors, retailers and wholesalers who did some processing. In-depth interviews were also held with twelve (12) retailers (supermarkets), eighteen (18) street vendors and five (5) wholesalers with the main aim of gathering information on their relationship with other chain actors, especially producers as well as the challenges they experience. The main objective of conducting in-depth interviews at different stages of the value chain was to identify activities each actor performs as well as the constraints they face.

In-depth interviews were also conducted with financial and business advisory support services with institutions such as the Local Enterprise Authority (LEA), Citizen Entrepreneurial Development Agency (CEDA), and National Development Bank (NDB). Consultations were also held with the training, education, research and capacity building institutions such as LEA, Botswana University of Agriculture and Natural Resources (BUAN), National Agricultural Research and Development Institute (NARDI), Botswana Bureau of Standards (BQA) and the extension services of MoA.

Lastly, in-depths interviews were held with key stakeholders offering institutional and regulatory support to the horticultural sector. These included government ministries and departments: Ministry of Agriculture (Department of Crop Production, and Department of Plant Health), Ministry of Entrepreneurship (Department of Cluster Development (representing the former Department Agribusiness Promotions in the Ministry of Agriculture, Ministry of Trade and Industry (Department of International Trade) and Ministry of Land Management, Water and Sanitation Services (Department of Water Affairs and Department of Lands) and Ministry of Health (Department of Public Health – Nutrition and Food Control Division).

2.2.3. Focus Group Discussions

At support level two main data collection methods were used: focussed group discussions (FGDs) and in-depth interviews. FGDs were held with key stakeholders in the horticultural value chain including the national and district farmer-based organisations. The FDGs were held with three (3) farmers’ associations at the district level and the national level – Botswana Horticultural Council (BOHOCO). The main purpose of the FGDs with farmers associations were to find out the role they perform as well as their strengths, and weaknesses they face in the performance of their mandate. Additionally, the FDGs were also aimed at finding the opportunities and threats they faced.

2.2.4. Desktop Reviews

In addition, data was also collected through desktop review of documents on the horticultural sector, especially previous value chain studies undertaken on Botswana horticultural sector. Desktop reviews of horticultural value chain studies undertaken elsewhere as well as secondary data on horticultural production and trade from MoA and Statistics Botswana were undertaken to augment primary data.

2.3. Data Analysis

2.3.1. Analysis of Survey Data

Data collected through the survey was mainly analysed using descriptive measures such as frequency tables to characterise the farmers in terms of farm size, level of technology used,technical skills etc. Some of the questions from the survey were analysed using rankings as the respondents were required to rank their responses. The different items in each question were given weights and their influence on a particular issue being investigated was determined by reporting the total score (computed by multiplying the weights * frequency counts). All the analyses were performed using Microsoft excel.

2.3.2. SWOT Analysis

A SWOT analysis for the horticulture sector is a tool that can be used to determine what the sector does well (strengths) and what it does not do well (weaknesses). The strengths are the positive attributes of the value chain, while the weaknesses are the negative attributes, and these are internal to the horticulture sector. The SWOT analysis also identifies the opportunities and threats that can shape the current and future operations and develop strategic interventions. The opportunities and threats are external to the chain and hence chain actors have no control over them. Opportunities are the positive attributes that can enhance the value chain performance, while the threats are negative factors that could inhibit the efficient working of the chain. (

Table 2)

3. Results

This section presents the results of the study. The section starts with the characterization of producers followed by a SWOT analysis of the horticultural value chain. The section is concluded by a discussion of the main constraints and opportunities at each stage of the value chain.

3.1. Characterisation of Producers

The characterisation of primary producers is shown in

Table 3. The majority (71%) of primary producers are male. In terms of educational attainment an overwhelming majority (99%) had attained some kind of formal education, with 58% and 36% having attained secondary and tertiary education respectively. However, only 57 (56%) of the primary producers had received training on horticultural production. This training was mainly received through short courses 38(67%) with only 19(33%)having attained formal training at certificate, diploma and degree levels.

The sampled farmers planted a total of 289 hectares in 2022 planting season. Out of these hectares 246(85%) were planted under open field, followed by 35(12%), 7(2.4%) and 1 (0.34%) who planted under shade net, tunnel and greenhouse respectively, with no hectare being planted under hydroponics. Thus, despite the challenges brought by climate change such as increased frequency and severity of extreme weather events, most of vegetable production is undertaken under open field cultivation.

When farmers were asked as to whether they belonged to any farmer-based organisation 69(68%) indicated that they belonged to one form of organisation, with 35(51%) indicating that the belonged to an association, 19(28%) indicating that they belonged to clusters, 4(6%) belonged to cooperatives and the remaining 11(16%) belong to a combination of associations, clusters, and cooperatives. Age

In terms of sources of water most of the sampled farmers used river water, with 93 (x%)using seasonal and x (y%) using perineal river, followed by 56 (x%) who used boreholes. The mostly used irrigation technology is drip which was used by 83 (81%) of sampled farmers, followed by sprinkler 32(31%), hose pipe 23(23%), watering can 16(16%), with the least being farrow 3(3%) and others 5 (5%).

3.2. SWOT Analysis

A SWOT analysis of the Botswana horticulture value chain is presented in

Table 4. The analysis was undertaken to identify key strengths which the chain can rely on and opportunities which could be exploited to improve chain performance. The SWOT also identified key weaknesses which need to be addressed to upgrade the workings of the value chain. Lastly the analysis identified threats that could pose a problem to the chain and hence need to be considered when developing interventions to improve the workings of the chain. The SWOT analysis identified three (3) key strengths, twelve (12) weaknesses, five (5) opportunities and eleven (11) threats.

3.2.1. Strengths

As indicated earlier the strengths are internal to chain actors and are positive attributes of the chain that could be leveraged upon to improve chain performance.

Supportive Government Programmes

One of the key strengths of the horticulture sector is that it receives support from government as it is seen as one avenue through which the agriculture sector could be diversified as well as employment creation. Support has been concentrated at primary production and include the Impact Accelerator Subsidy (IAS) which offers grants of 50% for horticultural farmers up to a maximum limit of BWP300,000.00 [

6]. Additionally, through the Control of Goods, Prices and Other Charges Act the government has been imposing import restrictions and in 2022 an import ban on sixteen (16) selected vegetables was imposed with the view of improving smallholder farmers access to market. The ban was initially for two years and has been extended by a further two years and the list of banned products expanded to 32 products. Other support was through the construction of fresh produce market and central market with the view of improving market access. These however were not successful and collapsed and there is a desire to reopen them with the central market just starting operation at one location with plans to expand to other regions.

Availability of Land

Availability of land is one the greatest strengths for horticultural production as the sector does not need too much land. This is corroborated by the fact that most farmers have idle land as shown by farm survey results which indicate that only 78% of available land was under cultivation.

Availability of Cheap Labour

Farmers have indicated that labour for horticultural production is readily available at cheaper rates. This labour is mainly sourced from locals (66%)and foreign nationals (34%), mostly Zimbabweans (30%). The farm survey results show that most foreign horticultural workers do not have both work and residence permits. The main reason for this is that farmers feel that the costs of obtaining residence and work permits are prohibitive, especially smallholder farmers.

3.2.2. Weaknesses

Weaknesses are also internal to the chain and are negative attributes of the chain that need to be addressed to improve chain perfoamnce.

Food Safety Issues

One of the main weaknesses of the horticulture sector in Botswana is concerns regarding food safety. Horticultural products are produced using agrochemicals whose residues can be harmful to human health if they exceed certain levels. To ensure that fresh produce is safe there is need to test and certify the minimum residue levels. However, there are no testing services to determine residues on fresh produce for products destined for retailing which poses serious risks to human health. Products enter the retail sector straight from the farm without any testing and inspection and this poses serious problems to human health. This occurs despite the fact that the Food Control Act was enancted in 1993 whose main objective is to ensure the provision of clean, safe and wholesome food to consumers [

41] suggesting poor implementation of the Act.

Lack Mandatory Standards

Although BOBS has 33 standards on horticulture these are not mandatory and hence not regulated. Lack of mandatory standards also mean that fresh produce from farmers is not graded, hence poor and good produce receive the same price. This acts as a disincentive for farmers who want to improve quality of their produce. Lack of mandatory standards does not only disadvantage producers who produce better quality products but can also act as hindrance if the country wants to access global markets at a later stage. Export markets are particularly important for country like Botswana which has a small population, hence market. As production increases beyond the local demand there will be need for export. This could only be achieved if the country meets the standards set by importing countries. Therefore, there is need to strive to meet the Global Good Agricultural Practices (GAP) standards. To achieve this the country needs to develop a mandatory local GAP which can be developed into a Global GAP in order to access global markets when the need arises. The GAP is the minimum standard that exporters require and there are other standards that Botswana will have to meet depending on the export destination.

Inadequate Laws Covering Biosecurity

Currently there are no laws on biosecurity posing threat of imported pests and diseases. In fact, it has been reported that (interview with Department of Plant Health) in the last five years or so, about 6 new diseases and pests have been imported into the country. The current Plant Protection Act of 2009 [

42] appears to be ineffective. Lack of biosecurity laws leads to a situation where seeds enter the country without checks on their safety posing serious risks of importing diseases. In addition, interviews with input suppliers revealed that there are several unregistered seed suppliers who do not only pose a threat of importing diseases, but also unfairly compete with the registered suppliers as they do not pay tax.

Poor Extension Services

One of the weaknesses of the horticulture sector is poor extension services. Farmers decry that extension services offered to them by DCP Horticulture Section are insufficient, with many arguing that officers from the section are preoccupied with collection of data from their farms and do-little extension. This has resulted in farmers relying on social media for extension services some of which may not be credible. An analysis of the farmer survey revealed that only 40% of farmers had received extension support from government, 10% from the private sector, 9% from non-governmental organisation and 5% from other providers.

Poor Technical and Farm Business Skills

Related to poor extension services is the poor technical and business skills on the part of primary producers leading to low productivity partly due to poor crop husbandry and management of pests and disease. In addition, to poor technical skills, is lack of farm business management skills. This results in farmers not keeping proper record for measuring financial performance of their enterprises, and hence make it difficult for farmers to identify causes of poor financial performance and hence measures to improve it. Thus, lack of proper records incapacitates the farmers to know and control their costs, sales and profitability margins, which are ideal for any business enterprise.

Lack of Market Access and Corrupt Marketing System

Despite government efforts to improve market access through interventions such as the import restrictions and bans there is still problem of market access, especially for smallholder farmers. The problem of market access is made worse by the fact that there is no operating central market, nor collection centres through which farmers can sell their produce. This makes it difficult for both the producers and buyers as the logistics of finding a market are strenuous as well as the difficulties of the buyers to source produce from one place. For instance, farm survey results indicate that lack of market access has been ranked as the top 4 challenges faced by farmers out of the 14 challenges identified (

Table 5).

The problem of market access is also exacerbated by the fact that farmers decry that the marketing system is corrupt in that traders prefer to buy from certain suppliers not because of good quality, but because of friendship or other considerations. Instances where farmers are required to give out favours to buyers has been reported across the marketing system. Moreover, farmers decry lack marketing infrastructure for fresh produce such as cold rooms which leads to high post-harvest losses as products deteriorate before they are marketed. For instance, farm survey results indicate that only 33(32%) of farmers surveyed owned some kind of storage facility, with only 1 out of these owing a cold room.

Limited Market Intelligence

One of the prerequisites of an efficient marketing system is that they should be free flow of information. This information should include prices, and quantities as well as location. This information is lacking in the horticultural industry. The Department of Agribusiness Promotions attempted to improve this by developing an online platform (AGRIMA) through which farmers and traders could find out the quantities of the produce sold as well as the prices. At the time of writing this platform was not operational. An interview with the Department of Agribusiness Promotions revealed that the new parent ministry, the Ministry of Entrepreneurship intends to expand the platform to cover all agricultural products. It is not clear how accessible the platform was to both traders and farmers, especially smallholders. However, these updates do not cover the majority of farmers and hence will not accurately indicate the product availability.

Uncoordinated Production

Production is poorly coordinated with farmers planting the same vegetables at the same time leading to excess supply in some instances and shortages in other periods. This persists even though attempts have been made by district farmers associations and at the national level. The Botswana Horticultural Council (BOHOCO) does not have the capacity to develop and enforce cropping plans because of lack of funds. At the time of the study, the association did not have a secretariat making it difficult for it to develop national cropping plans. Thus, farmers tend to plant in season vegetables, and this leads to a glut in the market which causes prices to fall to even below production costs leading to losses for farmers. On the other hand, shortages lead to increases in prices leading to reduced affordability on the part of consumers, especially low-income households. The problem of uncoordinated production is associated with unorganised farmers which in turn result in them being price takers as individually they do not have strong bargaining power against retailers or traders. For instance, farm survey results reveal that 69(68%) of farmers belong to a farmer based organisation, with the majority (52%) of the 69 belonging to a an association (

Table 3). However, the farm survey results indicated that the main madate of these associations was advocacy with limited role in marketing of both inputs and outputs.

Unskilled Labour

Although farmers have indicated that one of the strengths of the horticultural industry is that cheap labour is readily available, they felt that it is unskilled and highly unreliable. The use of unskilled labour affects crop husbandry and management leading to high in-field losses. The result is low productivity and profitability affecting sustainability and survival of such enterprises. As indicated in

Table 6, the main causes of in-field losses are diseases and pests which require some kind of technical skills for proper control.

Uncoordinated Support Services

Several institutions, public, public-private-partnerships and private are involved in support to the horticultural sector. In most cases these institutions work separately without any coordination of their interventions leading to fragmentation, ineffective and inefficient support to the sector.

Poor Infrastructure

Horticultural production needs specialised infrastructure. For example, due to the perishable nature of fresh produce, products need to be stored and transported in refrigerated storage and vehicles. The farm survey results indicate that only 1 out of 102 farmers surveyed used refrigerated trucks to transport their vegetables. This is one of the main reasons for high post-harvest losses (

Table 6). Farm survey results also indicate that despite the increased frequency and severity of extreme weather events, an overwhelming area under cultivation 246 hectares (85%) of the 289 hectares have been planted in open field exposing crops to risks of damage to extreme weather events. In addition, irrigation equipment and protected environment infrastructure is very expensive, and most farmers do not have these facilities as indicated by the farm survey results. At the market level there is insufficient marketing infrastructure such as collection centres and central market as well as processing facilities making it difficult for farmers to sell their produce.

Low Access to Credit

Most farmers use their own sources of funds to start and expand their horticulture projects. There is limited credit to their horticulture sector, and this inhibits growth of the sector as the sector is capital intensive. Additionally, poor access to credit also inhibits productivity growth as farmers are unable to adopt technologies such as production under protected environment in the face of harsh climate. For instance, farm survey results indicate that 76(75%) of farmers used their own funds to start their horticultural projects. The main source of finance apart from own sources is the Citizen Entrepreneurial Development Agency (CEDA) which funded 7(7%) of surveyed farmers, followed by National Development Bank (NDB). Both of these are development finance institutions and the level of funding from commercial banks is very low with only one farmer indicating that he/she received start up finance from commercial banks. In-deth interview with CEDA has revealed that the majority of horticultural projects they have funded have performed poorly and hence limited financing to horticultural projects.

3.2.3. Opportunities

Opportunities are external to the chain and are positive attributes that can enhance chain performance if they are taken up.

Increased Interest on Horticulture

There is growing interest in horticultural production as new farmers are entering the sector. This will surely increase production and substitute imports which will save the much-needed foreign exchange spent on the imported vegetables. The extra produce can also be used as an raw materials in the processing sector and hence reduce the import bill on processed vegetable products.

Public Procurement

Through the Citizen Economic Empowerment Policy (CEEP) and Economic Inclusion Act government facilitates market access including for citizen horticultural farmers. Government institutions such as schools, hospitals and the discliplined forces (the army, police and prisions services are required to prioritise procurement from citizen farmers thereby increasing their market access. The farm survey results show that 53(52%) of the survey farmers sold to public institutions, with schools dominating at 90%, followed by hospitals and a combination of schools, hospitals and prisons.

Sufficient Demand for Vegetables

Local production of vegetables falls short of demand which presents an opportunity for farmers to increase production. However, in 2021 before the imposition of the import ban local conusmption estimated by local prduction and net imports amounted to 120,687.53 tonnnes, while in 2022 local demand stood at 64,340.21 tonnes [

43,

44] due to the imposition of an import ban on selected vegetables. This shortfall in consumption gives an opportunity for increased production locally.

Processing Potential

Most processed products from vegetables are imported and this opens up an opportunity for local processors to meet the local demand for processed products and eventually exports. In 2021 and 2022, the imporst of processed vegetable products amounted to BWP254 million and BWP348 million respectively, while exports were valued at BWP19 million and BWP6 million over the same period. This creates an opportunity for increased processing.

3.2.4. Threats

Threats are negative factors that could prevent efficient working of the chain and hence need to be addressed for improved chain performance.

Support Programmes Focused on Primary Production Only

Government policies are only geared to primary production at the expense of other stages of the value chain such as processing. This limits value chain development as poor performance at some stages of the chain affect the performance of the whole chain. For instance, limited processing potential leads to high post-harvest losses during period of high supply. The import ban on selected vegetables did not cover processed products which limits the development of the processing sector.

Limited Water Resources

Horticultural production is water intensive and due to limited surface water resources; farmers must rely on underground water resources. In some places it is difficult to get sufficient water for irrigation. In other places the drilling and equipping costs are prohibitive especially to smallholder farmers because of deep water tables, and in some cases the quality of the water is not suitable for irrigation. Limited water resources was ranked nineth out of fourteen major weaknesses of the horticultural sector by surveyed farmers (

Table 5).

Lack of Interest by the Youth in the Sector

Although one of the opportunities in the horticulture sector is growing interest, there is limited youth participation in the agriculture sector in general and horticulture in particular. Most farmers are elderly and comprise mainly of retirees who may not have enough energy and zeal possessed by the youth to move the sector forward. The farm survey results shiw that only 7(7%) of farm owners were less than 30 years old and 36(35%) were below were below 40 years, while the remider (57%) were above 50 years (

Table 3).

Removal of the Import Ban

One of the biggest threats at primary production level is the removal of the import ban on selected vegetables as it has the potential of raising trade disputes. In fact South African farmers have raised the issue with their government. The removal of the import ban will further exercabate the problems of market access for local smallholder famers as supermarkets have in the past shown preference to source their supplies from imports as they can buy a variety of products in bulk from one source and hence reducing the losgistcal requiremnts of buying small quantities from several smallholder farmers locally [

45].

Stiff Competition from Imports

Local farmers face high production costs due to relatively small farms and inexperienced local farmers compared to relatively large and experienced counterparts in neighbouring countries, particularly South Africa. For instance, cost of electricity, seeds, fertilisers, insecticides and pesticides are higher compared to South Africa making it difficult for farmers to compete with imported products form that country.

Smuggling of Banned Products

Smuggling of banned products by some traders contravenes government efforts to promote horticultural production as it limits market access of local products. In addition, the smuggled products can also pose threats of introducing diseases and pests as they have not been issued with imports permits and hence have not been certified safe.

Low Technology Adoption in the Face of Climate Change

Lack of technology adoption, for example protected environment as costs are prohibitive to farmers, especially smallholders. This leads to high in-field losses and poor-quality products due to extreme heat waves, frost and other extreme weather events. This coupled with climate change which leads to increased frequency of extreme weather events leads to high in-field losses. The farm survey results have shown that only a handful of farmers have adopted protected production under protected environment despite the increased frequency of and severity of extreme weather events as a result of climate change.

Vertical Integration Into Primary Production by Retailers

Retail stores are vertically integrating into production as they have opened and are operating horticulture farms and sell the products in their retail stores. This will surely reduce the amount of fresh produce the retailers source from the farmers and hence reduce their market access. On the other hand, such a move might possibly lead to anti-competitive behaviour in the industry. However, the current competition law allows for vertical integration and only prohibits it if it is achieved through mergers and acquisitions.

Poor Control of Diseases and Pests Outbreaks

Diseases and pests outbreaks are a major concern at primary production and these leads to heavy in-field losses. Some farmers neither do not have the financial nor the technical capacity to control diseases and pests leading to heavy losses. This is corroborated by the fact that there is a huge difference between actual productivity and efficient productivity. For example for the top five vegetables the gap between efficient production and actual production was as high as 53% for cabbage, 47% for rape, 39% for onion, 37% for tomato and 16% for potatoes as shown by the farm survey results.

Criminal Activities

Stakeholders, especially farmers have indicated that there is increased incidence of criminal activities in the farms. This is so because their farms are located in rural areas and are susceptible to break-ins and stealing valuables especially equipment such as solar panels, borehole pumps and other equipment. This disrupts production and impart heavy losses to the farmers.

4. Challenges at Each Stage of the Value Chain

One of the objectives of the study is to identify constraints along the horticultural value chain. The SWOT analysis presented above has identified several weaknesses which inhibit the development of the horticultural value chain. This section presents the main constraints at different stages of the value chain from input supply through to end markets. The identification of constraints is critical because it is only when they have been identified that proper interventions could be instituted to address them and hence enhnce the working of the value chain.

4.1. Input Supply

The major challenge at input supply level as stated by stakeholders is that there is lack of seed policy, and this puts the country at risk of importing diseases through infected seeds. In addition, there are unlicensed seed suppliers in the market, and these do not only pose a threat of bringing diseases into the country or supplying farmers with poor seeds, but also, they unfairly compete with licensed seed suppliers as they do not pay tax (income and value added taxes). For agrochemicals, Botswana does not have regulations for their registration and relies on third country regulations. Reliance on third country’s poses some risks of corrupt practices in the country where certification is made and difficulties in detecting this.

4.1.1. Primary Production

Primary producers face several constraints, chief among them being pests and diseases (

Table 5). Producers are not able to control pests and diseases mainly due to lack of technical knowledge and in ability to afford appropriate agrochemicals. This leads to high crop losses and huge divergence between actual and efficient output. Another constraint is that most of the inputs supplied are imported, and hence expensive. Seeds, fertilisers, agrochemicals, machinery and equipment are mostly imported especially from South Africa. This makes them expensive compared to South Africa and hence it is difficult for local producers to compete with South African imported products.

The increase in the severity and frequency of weather conditions is another major challenge at primary production which is mainly brought be climate change. Related to this is lack of capital due to limited access to credit. Lack of capital leads to farmers being unable to adopt to modern farming technologies to mininise the effects of extreme weather events. The failure to adopt modern farming technologies such as production under protected environment (net shades, green houses, tunnels, hydroponics) leads to poor productivity. Low access to credit is particularly a constraint to smallholder farmers who constitute the majority of horticutural farmers. The main source of funding is government programmes such as IAS and Youth Development Fund for the youth. However, for the IAS farmers are required to contribute 50% of the costs and for some raising the required contribution has proven to be difficult, hence low uptake of the scheme.

At primary production further constraints include crop losses, both in-field and post-harvest (

Table 6). The main causes of post-harvest losses are lack of market, poor harvesting and handling techniques, poor storage and transportation. As argued by [

12] post-harvest losses in Southern Africa are very high especially for horticulture due to lack of suitable post-harvest and processing techniques. Additionally, insufficient or no cold chain technologies and infrastructure exacerbate post-harvest losses experienced by smallholder farmers. While there are technologies available, lack of finance is a major impediment to adoption. The greatest causes of in-field losses as reported earlier are pests and diseases, followed by weather conditions such as frosts and high temperatures/heatwaves (

Table 6).

4.1.2. Processing Level

There is limited processing of horticultural/vegetables products in Botswana partly due to inconsistent supply which results in factory grade produce being traded as fresh produce. In response to this, the Government of Botswana through the National Agricultural Research and Development Institute (NARDI) set up a National Processing Plant (NAPRO) to promote the processing of horticultural products in the country. NAPRO was set-up as a prototype to be tested for commercial use. The plan was for NAPRO to test the prototype and once successful pass the model to commercial undertakers who could start processing of various products from fresh produce. The plant and equipment were based in a model imported from India. Since its commissioning the plant has faced operational problems and has never operated at full capacity.

The key challenges faced by NAPRO include limited and inconsistent supply of raw materials from farmers, limited acceptance by consumers of the new products and limited shelflife of products compared to established brands, especially for tomato sauce. The location of the plant also means it is only able to access produce from within the locality as there is no incentive for farmers from other regions to bring their produce to the processing plant; infrastructure and transport costs are some of the key constraints especially for small farmers.

Another challenge in processing of tomatoes into sauce at NAPRO is that the local varieties produced are not suitable for processing, especially into tomato sauce. The parent organisation is aware of this and is planning to characterise tomato varieties into those suitable for table use and processing. This is work will involve the characterisation of varieties of several crops produced locally. Lack of processing results in produce being lost especially during periods of excess supply as the market can not absorb all the produce.

4.1.3. End Markets

The main market outlets for producers are retailers (supermarkets) followed by hawkers and individuals (

Table 7). These are also the highest paying markets. The main constraint at end markets is that farmers decry low prices received for their produce as they are price takers and negotiate from a weak position. This is so because farmers are unorganised when it comes to marketing their produce leaving them to the mercy of buyers. Farm gate prices as highly volatile, with prices of certain products fluctuating by a margin as high as 60%. These fluctuations imply that farmers are unable to recoup their production costs during the period of excess supply, rendering their enterprises unprofitable.

Additionally, interviews with key stakeholders and farmers indicated that the marketing system is corrupt with some buyers preferring to procure from certain suppliers not because of quality, but because friendships and other considerations. Farmers indicated that they are required to bribe the buyers for them to purchase their products.

4.2. Opportunities

Identification of oportunities in the value chain is critcal as leveraging on these could develop the value chain. This section identifies opportunities along the value chain which actors could sieeze and hence develop the chain.

4.2.1. Input Supply

There areopportunities at input supply as most inputs are imported, except for irrigation accessories such as pipes, driplines and plastic reservoirs which are manufactured locally. This creates an opportunity for local manufacturers to produce inputs such as net shades, fertilizers and others. In fact, during in-depth interviews, it was revealed that local manufacturers have started producing some inputs needed for horticulture production. One local manufacturer had started producing net shades, while others have started producing organic fertilisers and packaging materials.

4.2.2. Primary Production

At primary production there are several opportunities emanating from the fact that there is unmet local demand for horticulture products as well as low productivity and high in-field and post-harvest losses. Thus, farmers have the opportunity to increase productivity usng alsmost the same amount of inputs by adopting good agronomic practices. To improve productivity, there is need to improve extension services to impart both the technical and business management skills on farmers. This will also reduce in-field and post-harvest losses as farmers will become more knowledgeable on disease and pest control as well as proper post-harvest handling techniques.

4.2.3. Processing

Most of the processed horticultural products in Botswana are imported, presenting an opportunity for local processors. One of the key constraints at processing level has been poor and inconsistent supply of raw materials, as well as inappropriate varieties supplied.

4.2.4. End Markets

As stated earlier end markets in the horticulture value chain inlcude: street vendors, retailers (super markets) and public institutions. While there are issues in terms of accessing the supermakerts especially by smallholders, there are opportunities that could be exploited through public procurement. This could be supported through the Citizen Economic Empowerment Policy (CEEP) and inforced by Citizen Economic Empowerment Act.

5. Conclusions

Horticultural production in Botswana is at an infant stage, however the sector has shown considerable growth over the years with both the number of farms and output having increased. This was spearheaded by several supportive policies. However, the sector faces several challenges mentioned above. The development of the value chain requires that the challenges be adressed so that the value chain actors are able to grab opportunities presented to them.

The study has found that there is low productivity at primary production as actual output is far below efficient output. The main reason for this is the use of inappropriate agronomic practices due to lack of technical skills on the part of the farmers as a result of inadequate extension services. Other challenges at primary production are inappropriate control of pests and diseases, and post-harvest handling techniques leading both high in-field and post-harvest crop losses. These problems are made more worse by the fact that although there are several institutions supporting the horticultural value chain, such support is ineffective as these are uncordinated. To solve this problem, there is need to improve extension services as well as form an institution which could cordinate the support given to famers.

The challenge of market access still persists even when several measures including import restrictions and bans have been imposed. Thus, smallholder farmers meet difficulties when selling their produce, especially during periods of excess supply. Farmers end up selling their produce below the costs of production or even worse fail to sell it leading to huge losses.

The market access issue can be addressed by setting up cold storage collection centres and central market through which retailers and other end market actors could purchase products from. This will solve the problem where farmers have to negotiate prices with supermarkets as well as reduction in post-harvest losses which occur because their produce has not been able to find the market. Additionally, the central market will make it easier for certification of products to ensure that there are safe for human consumption unlike what is currently happening where farmers take their products directly to supermarkets without any checks. The central market can be constructed together with processing facilities to ensure that products that do not go to fresh produce market enter processing facilities to avoid unnecessary losses.

Market access could also be addressed by collective action. For example, farmers could form cooperatives through which they could sell their products and buy inputs. By selling products as a collective the farmers will have bargaining power as opposed to selling individually, while buying inputs will ensure that they buy in bulk and hence more likely to receive discounts. This is will partly solve the problem of expensive inputs. In addition, farmers and buyers could enter into supplier development programmes through which the buyers provide training to farmers so that they produce the desired quality and quantities required. The buyers could also supply farmers with the necessary inputs to ensure quality and consistent production. as well as market access through the use of contracts.

Lack of credit was identified as one of the key constraint to technology adoption in the face of climate change leading to low yields as hence profitability. While there are development finance institutions such as CEDA and National Development Bank credit to horticulture has been low. The main reason for this as cited by these institutions is that the non-perfomance of loan portfolio to horticulture. As a result commercial bank credit to horticulture is almost non-existent. The key to unlocking credit is to improve financial perfomance of horticulture enterprises through training in both the technical and business management. This will go a long way towards improving technology adoption, hence improvement productivity.

At processing level there is very limited processing undertaken and the country relies on imported processed products to meet local demand. Part of the reason for this is the poor quality of raw materials supplied and the processed products. There is need to conduct research on the varieties suitable for processing as well as the processing undertaken to improve the quality of the processed products in terms of shelf life and acceptability.

Despite the above challenges there are several opportunities in the horticulture industry starting from iput supply to end markets. At input supply there are opportunities for supplying some inputs such as packaging materials, irrigation equipment, net shades as well as organic fertillsers. At primary production unmet local demand for horticulture products presents opportunities for increased production. The country relies on imports to meet its demand for processed horticulture products which gives an opportunity for at processing level. Filling the productivity gap will go a long way in improving profitability of enterprises and increasing supply of horticuture products to meet local demand and possibly for exports.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Patrick Malope.; methodology, Onkabetse V. Mabikwa; Validation, Mogapi, E Madisa., and Dyna Solani; Formal analysis, Patrick Malope; Investigation, Mogapi E. Madisa; Resources, Dynah Solani.; Data curation, Onkabetse V. Mabikwa; Writing—original draft preparation, Patrick Malope.; Writing—review and editing, Onkabetse V. Mabikwa, and Dynah Solani.; Visualization, Mogapi, E Madisa; Supervision, Patrick Malope.; Project administration,; funding acquisition, Dynah Solani. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Local Enterprise Authority (LEA) Botswana, as part of a larger Study on Horticulture Value Chain Mapping and Analysis.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Verbal and written informed consent were taken from study respondents during field work

Data availability: Data is available upon request

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Government of Botswana Second Transitional National Development Plan, April 2023-March 2025. Towards a High-Income Economy: Transformation, now, prosperity tomorrow. 2023. National Planning Commission. Office of the President, Government Printer, Gaborone, Botswana.

- Amao, I. Health benefits of fruits and vegetables: review from Sub-Sahara Africa, doi.org/10.5772/intechopen,72272. In Vegetables-Importance of quality vegetables to human health. Eds. Asaduzzaman, M.D.; Assao, T. InTech. 2018, pp.33-53.

- FAO. International Year of Fruits and Vegetables 2021, Fruits and vegetables – your dietary requirements, Background paper, 2020, 63 pages, FAO, Rome. doi.org/10.4060/cb2395en.

- Afshin, A. , Sur, P.J., Fay, K.A., Cornaby, L., Ferrara, G., Salama, J.S., Mullany, E.C; . Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. The Lancet 393(10184): 195872, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Botswana. Guidelines for Integrated Support Programme for Arable Agriculture Development Programme (ISPAAD).Revised Version, 2013. Government Printer, Gaborone, Botswana.

- Government of Botswana. Guidelines for ISPAAD Horticulture Impact Accelerator Subsidy (IAS), 2020, Ministry of Agriculture Development and Food Security, Government Printer, Gaborone, Botswana.

- Government of Botswana. Control of Goods and Other Charges Act, Chapter 43:08. 1973 Government Printer, Gaborone, Botswana.

- Government of Botswana Economic Inclusion Act. Act No. 26 of 2021. Chapter 28.05, 2021, Government Printer, Gaborone, Botswana.

- Government of Botswana. National Horticulture Strategy (2022-2030) Revised Final, 2022. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- Ministry of Agriculture. Horticulture Production Trends,2021. Department of Crop Production, Horticulture Unit. Gaborone, Botswana.

- Statistics Botswana International Merchandise Trade Statistics (2021), Gaborone, Botswana.

- Dubios, T, Nordey, T; Opara,L. Unleashing the power of vegetables and fruits in Southern Africa. 2020. In. Transforming Agriculture in Southern Africa: constraints, technologies and Process. eds. Sikora, RA, Terry, ER, Vlek, PLG and Chitja, J. Routledge, New York.

- Obi, A.; Maphahama, L. Obstacles to the profitable production and marketing of horticultural products: an offset-constrained modelling of famers’ perceptions, 2010. In Institutional constraints to smallholder development in South Africa. Ed. Obi, A. Wageningen Academic Publishers. The Netherlands. 2010, pp. [CrossRef]

- Fink, M. Constraints and opportunities for horticultural smallholders in Nacala Corridor in Northern Mozambique, 2014. Essay on Development Policy. NABEL MAS Cyle, 2012-2014.

- International Labour Organization. Improving market access for smallholder farmers: what works in out-grower schemes-evidence from Timor-Leste. 2017, Issue Brief No.1 www.ilo.org/thelab.

- Magala,N.M.; Bamanyisa, J.M. Assessment of market options for smallholder horticultural growers and traders in Tanzania, European Journal of Research in Social Sciences. 2018. Vol. 6(1): 27-42.

- Hassan, B. Bhattacharjee, M.; Wani, S. Value-chain analysis of horticultural crops-regional analysis in Indian horticultural scenario. IJAR 2020. 6(12):367-373. [CrossRef]

- Mapanga, A. A value chain governance framework for economic growth in developing countries. (2021)Academy of Strategic Management Journal. https://www.researchgate.net/publications/359115541.

- Namibian Agronomic Board. Agronomy and Horticulture Market Division, Research and Policy Subdivision. An analysis of market access by small-scale horticulture producers in Namibia, 2021. www.nab.com.na.

- Mathinya, V.N. , Frankie, A.C., Va De Ven, G.W.J.; Giller, K.E. Productivity and constraints of small-scale crop farming in the summer rainfall region of South Africa. Outlook on Agriculture. 2022, Vol 51(2): 139-154. [CrossRef]

- Barrientos, S and Visser, Southern African Horticulture: Opportunities and Challenges for economic and social upgrading in value chains, SSRN Electronic Journal. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Baliyan, S.P. Improving sustainable vegetable production and income through net shading: A case study of Botswana. Journal of Agriculture and Sustainability, 2014,5(1),70-103.

- Malhotra, S.K. Horticultural crops and climate change: a review. Indian Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 2012. 87(1):12-22. [CrossRef]

- Thakre, A. K and Bisen, A. challenges of climate change on horticultural crops and mitigation strategies through adoption of extension based smart horticultural practices. The Pharma Journal. 2023.

- Tejashree, S.G.; Shivalingaiah, Y.N.; Raghuprasad, K.P.S.; Rujar, S.S. ; Constraints and suggestions given by horticulture crop growers in adoption of precision farming technologies. International Journal of Advanced Biochemistry Research, 2024.8(9):793-800. [CrossRef]

- Manzoor MA, Xu Y, Iv Z, Xu J, Shah IH, Sabir A, Wang Y, Sun W, Liu X, Wang L, Liu R, Jiu S and Zhang, C. Horticulture crop under pressure: unravelling the impact of climate change on nutrition and fruit cracking. Journal of Environmental Management. 2024. https://www.doi.org.10.1016/j.jenvman.2024.120759.

- Wondim, D. Value Chain analysis of vegetables (onions, tomato, potato) in Ethiopia: a review, 2021. International Journal of Agricultural Science and Food Technology. https://www.peertechpublications.com.

- Madisa, M. E, Asefa, Y. and Obopile, M. Assessment of production constraints, crop and pest management in peri-urban vegetable farms in Botswana, Egypt, Acad. J. bilog Sci, H. Botany (2010a), 1():1-11.

- Mohamed, K.S.; Temu, A.E. Access to credit and its effect on the adoption of agricultural technologies: The case of Zanzibar. Savings and Development,2008, 32:45-89.

- Dimo, J. C, Maina, S.W.; Ndiema, A. Access to credit and its relationship with information and communication technology tools’ adoption in agricultural extension among peasants in Rangwe sub-county, Kenya. Asian Journal of Agricultural Extension, Economics and Sociology, 2022, 40(10):97-105. [CrossRef]

- Masca, U. , Mirriam, K.N.; Bor, E.K; Does access to credit influence adoption of good agricultural practices? The case of smallholder potato farmers in Molo sub-county, Kenya. Journal of Agricultural Extension and Rural Development, 2022. 14(1):24-32. [CrossRef]

- Valdes, R. , Gomez-Castilo, D,; Barrantes, L. Enhancing agricultural value chains through technology adoption: a case study in the horticultural sector of a developing country. Agriculture & Food Security 2023, 12:45. [CrossRef]

- Dube, E. , Tsilo, T.J, Sosibo, N.Z.; Fanadzo, M. Irrigation Wheat Production Constraints and opportunities in South Africa. S Afr J. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asian Development Bank (ADB). Sustainable Development and Climate Change Department. Dysfunctional horticulture value chains and the need for modern marketing infrastructure: The case of Bangladesh, 2020. https://www.adb.org/terms-use#openaccess. Accessed 29.12.2024.

- Kibinge, D. , Singh, A.S.; Rugube, L. Small-scale irrigation and production efficiency among vegetable farmers in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa: The DEA Approach. Journal of Agricultural Studies, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sikora, A. R, Tery, E.R, Vlek, P.L.G.; Chitja, J. Overview of Southern African Agriculture, 2020. In Transforming Agriculture in Southern Africa: constraints, technologies and Process. eds. Sikora, RA, Terry, ER, Vlek, PLG and Chitja, J. Routledge, New York.

- LEA, Horticulture Study on Fresh Fruit and Vegetables in Botswana, 2008, Local Enterprise Authority, Gaborone, Botswana.

- Madisa, M. E, Assefa, Y.; d Obopile, M. Crop diversity, extension services and marketing outlets of vegetables in Botswana,. Egypt. Acad. J. biology.sci., 2010b 1(1):13-22.

- Baliyan, S.P. Constraints in the growth of horticulture sector in Botswana. 1: Journal of Social and Economic Policy 2012, 9(1), 2012. [Google Scholar]

- ITC. Horticulture Sector Value Chain Analysis and Action Plan, 2015, Private Sector Development Programme (PSDP), Ministry of Agriculture and Centre for Enterprise Development.

- Government of Botswana. Food Control Act: Chapter 65:05. Government Printer, 1993. Gaborone, Botswana.

- Government of Botswana, Plant Protection Act: Chapter 35:02 Government Printer, 2009. Gaborone, Botswana.

- Ministry of Agriculture, Horticulture Production Report, Horticulture Unit 2022/23, 2023. Gaborone, Botswana.

- Statistics Botswana, International Merchandise Statistics, 2023, Gaborone, Botswana.

- Seleka, T.B.; Malope, P.; Madisa, M.E. Baseline study on tomato production, marketing and post-harvest activities in Botswana. Consultancy Report. 2002. Initiative for Development and Equity in African Agriculture (IDEAA).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).