Pterometrics and Phylogenetic Hypotheses

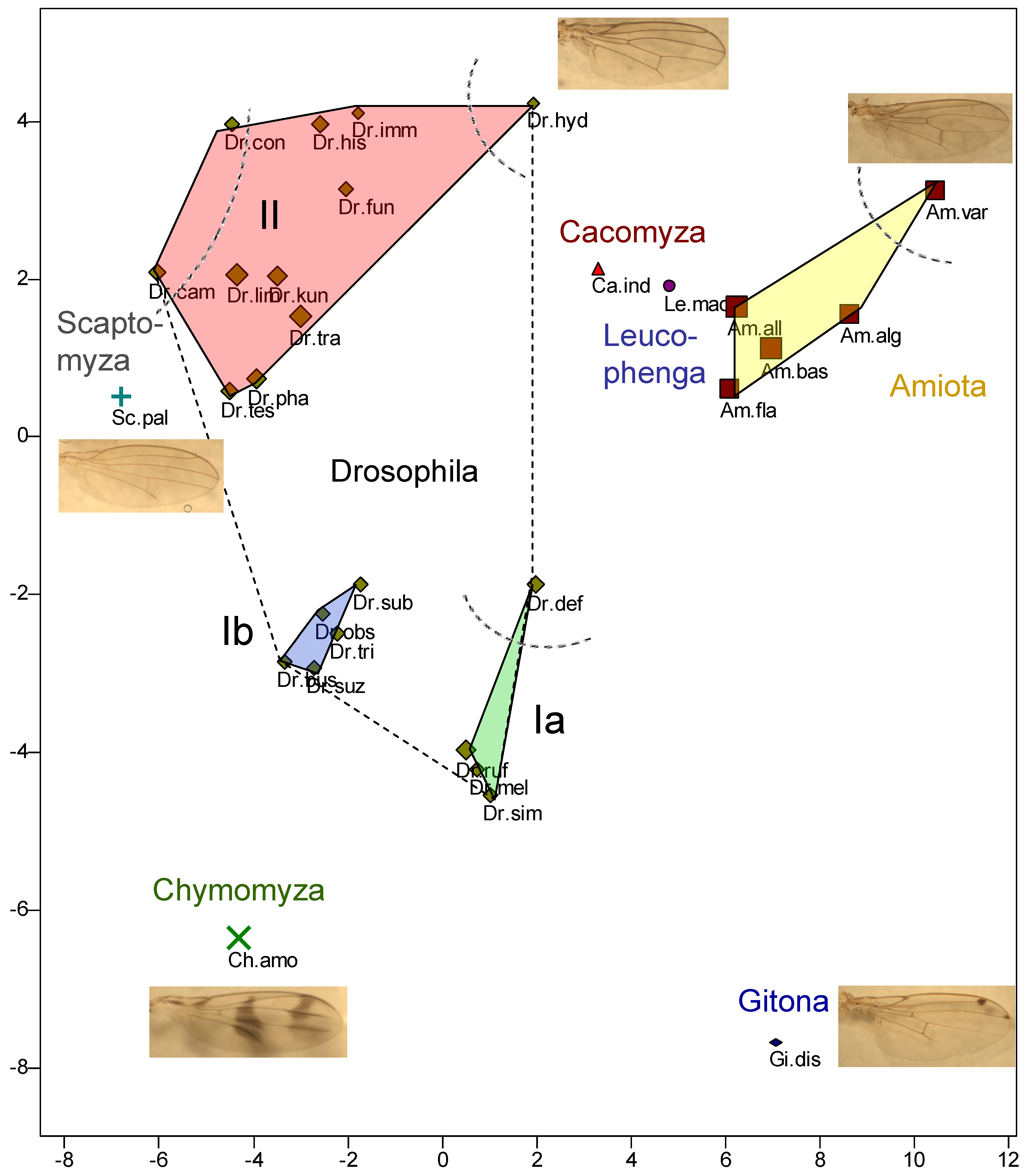

In order to be able to compare the diversity of wing proportions, a principal component analysis (PCA) was carried out for the 130 wings and a PCA for the 30 species, and the first two principal components (PCs) were presented graphically (Appendix 1 and

Figure 2). The basis for the analysis are the 54 distances calculated from the survey data, which mainly connect vein branches or one such branch with a vein edge position, as well as the wing length as an additional feature.

For the PCA of the 130 wings (Appendix 1), it is possible to specify the explanatory value of the principal components, i.e., the proportion of the observed variance that is explained by the respective principal component. For PC1 this is 33.3%, for PC2 17.21%, cumulatively for both 50.5%. All other principal components each explain less than 9% of the variance. Based on the two figures, a clustering of the species was carried out, whereby, in order to avoid bias, this was done by the author who was not yet informed about the phylogenetic theories of the family Drososphilidae at that time.

The pterometric analysis divides the genus

Drosophila into three clusters, Ia, Ib and II (

Figure 3). Ia consists of the species

D. melanogaster and

D. simulans, which belong to the subgenus Sophophora, as well as

D. (Scaptodrosophila) rufifrons and

D. (Sd.) deflexa, whereby the distance of

D. deflexa in

Figure 2 to the second cluster (Ib) appears to be as large as that to Ia. However, it should be noted that the two principal components shown are not equivalent. In addition, it can be seen in Appendix 1 that two of the wings, namely those of the female of this species, show a much greater similarity to group Ia, so that the assignment to Ia seems justified. But there is no doubt that

D. deflexa is somewhat separated within Ia.

Ib contains all species of the subgenus Sophophora not yet listed, namely

D. obscura,

D. subobscura,

D. tristis and

D. suzukii, whereby the latter is assigned to a different species group of Sophophora, namely ‘melanogaster’, in

Table 1 than the other species of Ib (species group ‘obscura’) and could therefore have been expected to cluster with Ia. It is interesting to recognise that

D. busckii also belongs to Ib, which according to

Table 1 is a species of the subgenus Dorsilopha. In Appendix 1, the symbols representing the wings of a species are connected by lines. It can be seen that there is no overlap between Ia and Ib, which justifies the separation of the two groups.

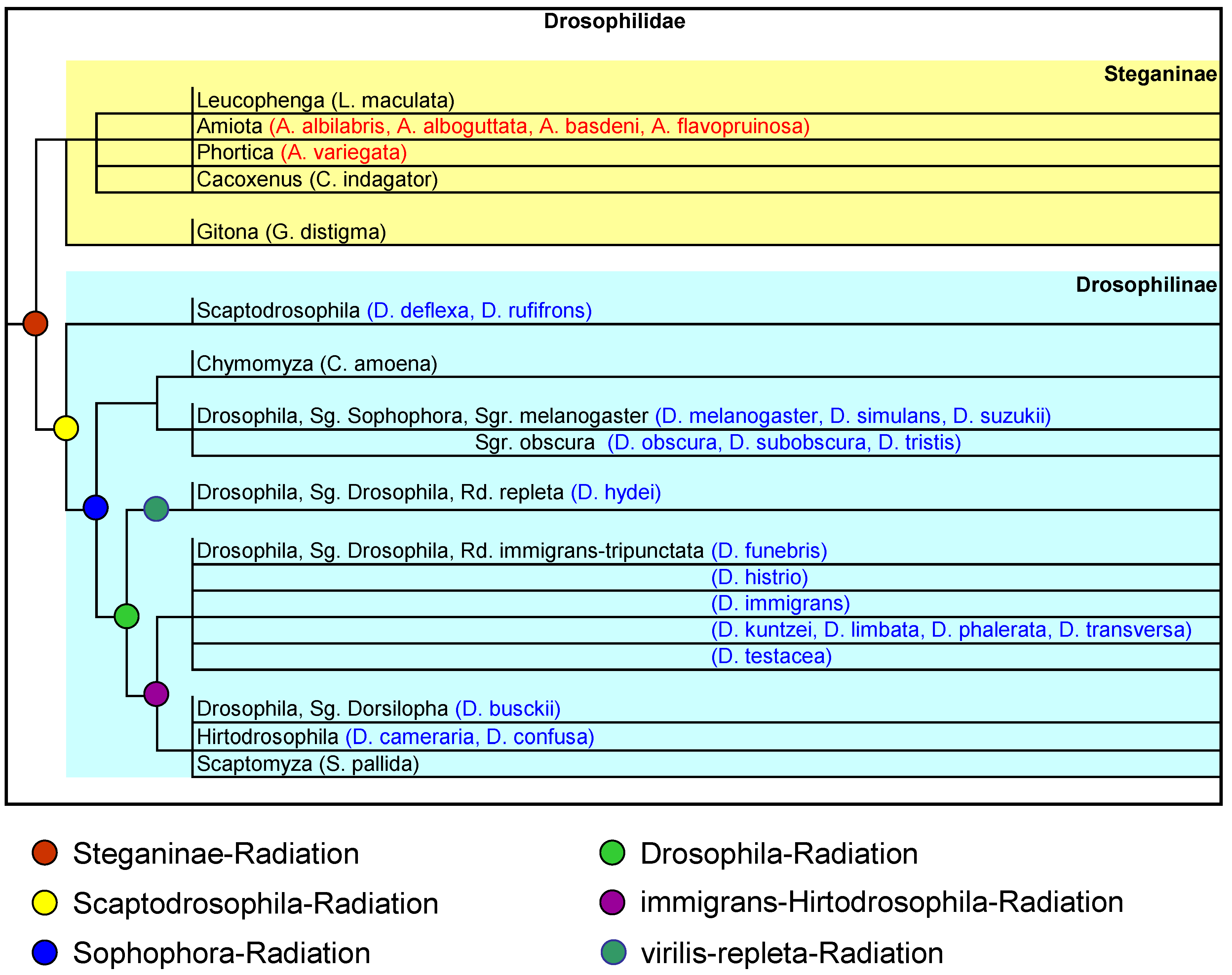

Comparing this result with Throckmorton 1975 and Yassin 2013 (

Figure 1), Ia and Ib contain, with one exception, only species of the early

Scaptodrosophila and Sophophora radiations (excluding the

Drosophila radiation). However,

Chymomyza also belongs to the latter, which actually shows the greatest similarity in wing proportions to Ia and Ib, but is also clearly separated. Since the Sophophora radiation occurred early, this does not contradict the phylogeny of Throckmorton 1975. On the other hand, there is a clear lack of agreement with the phylogeny of Russo et al. 2013, who assume

Chymomyza and

Leucophenga to be closely related. According to Throckmorton, Dorsilopha, i.e.,

D. busckii (cluster Ib), belongs to the very late ‘Old World Hirtodrosophila Radiation’, which is not consistent with the wing similarity. Yassin and Russo et al. (both 2013) see a much earlier branching of Dorsilopha, namely immediately after that of the Sophophora radiation, which can only partially explain the similarity of the wings, as the assumed time of the split is relatively far back.

Cluster II of the genus Drosophila contains species of the subgenus Drosophila (D. funebris, D. histrio, D. immigrans, D. kuntzei, D. limbata, D. phalerata, D. testacea, D. transversa, D. hydei) on the one hand, and the genus Hirtodrosophila (D. (H.) cameraria and D. (H.) confusa) on the other. D. kuntzei, D. limbata, D. phalerata, and D. transversa are assigned to the quinaria species group (which in turn is part of the immigrans-tripunctata radiation), which is close to D. testacea as far as the similarity of the wings is concerned according to

Figure 3. D. hydei belongs to the virilis-repleta radiation or repleta species group. There is no agreement as to whether D. funebris also belongs to the virilis-repleta group or to the immigrans-tripunctata radiation (which is part of the immigrans-Hirtodrosophila radiation). D. funebris is the type species of Drosophila and thus receives a lot of attention, but the ‘funebris species group’ (

Table 1) seems to have developed quite independently.

Figure 3 shows that its wings have less similarity to the virilis-repleta radiation and the quinaria species group within the immigrans-Hirtodrosophila radiation than to its remaining representatives D. immigrans and D. histrio.

Figure 3.

Principal component analysis of the 30 species analysed based on wing venation (54 distances between vein branches and vein edge positions) and length. PC1: x-axis; PC2: y-axis. Assignment of species to genera according to Bächli & Burla 1985 (Am.: Amiota, Ca: Cacomyza, Ch.: Chymomyza, Dr.: Drosophila, Gi.: Gitona, Le.: Leucophenga, Sc. Scaptomyza). See

Table 1 &

Table 2 for the abbreviation of the species names).

Figure 3.

Principal component analysis of the 30 species analysed based on wing venation (54 distances between vein branches and vein edge positions) and length. PC1: x-axis; PC2: y-axis. Assignment of species to genera according to Bächli & Burla 1985 (Am.: Amiota, Ca: Cacomyza, Ch.: Chymomyza, Dr.: Drosophila, Gi.: Gitona, Le.: Leucophenga, Sc. Scaptomyza). See

Table 1 &

Table 2 for the abbreviation of the species names).

In cluster II, the areas surrounding the wing symbols of a species overlap much less than is the case with Ia or Ib (see Appendix 1). It could therefore be further subdivided. For example, the two Hirtodrosophila species on the left edge of the cluster (D. (H.) cameraria and D. (H.) confusa), which show little similarity to each other, and also D. hydei, on the right edge of cluster II, are not overlapping. The separation here is made by PC1. The overlap (see Appendix 1) of cluster II (especially of D. testacea) with Scaptomyza (S. pallida, a species in which the wings of males and females differ relatively strongly) is striking.

If we compare Cluster II with the phylogenetic assumptions of Throckmorton 1975 (

Figure 1), we find that they reflect these quite well. A rather late ‘Drosophila radiation’ is assumed, which further splits into a ‘virilis-repleta radiation’ and an ‘immigrans-Hirtodrosophila radiation’, whereby the latter diverges even further and a ‘Hirtodrosophila radiation’ takes place. The latter includes

Hirtodrosophila,

Scaptomyza and Dorsilopha. The species

S. pallida,

D. (H.) cameraria and

D. (H.) confusa lie on the left edge of cluster II or close to it (as already mentioned, however,

D. busckii (Dorsilopha) is part of cluster Ib). All other species of the ‘immigrans-Hirtodrosophila radiation’ follow to the right in cluster II and

D. hydei, the only species of the ‘virilis-repleta radiation’ represented here, which is said to have split off first as part of the ‘Drosophila radiation’, is found on the far right.

The genera not yet discussed all belong to the subfamily Steganinae and can be found to the right of the centre in

Figure 3, i.e., they are separated from the Drosophilinae by PC1. PC2 splits the Steganinae into the genus

Gitona (‘bottom’ in

Figure 3) on the one hand and

Amiota,

Leucophenga and

Cacomyza on the other. Within

Amiota,

A. (Phortica) variegata is clearly separated from the other species of the genus by PC1 and PC2. According to Yassin,

Phortica is more closely related to

Cacoxenus than to

Amiota. However, this is not reflected in

Figure 3, but rather the idea of Throckmorton 1975, who assumes a closer relationship between the two genera

Amiota and

Phortica.

Amiota,

Leucophenga and

Cacomyza are only separated by PC1 and are close to each other.

In the phylogeny of Throckmorton 1975, the most ancestral radiation within the Drosophilidae is the one that separates Steganinae from the Drosophilinae, which fits well with

Figure 3, PC1. Yassin 2013 sees a closer relationship between

Amiota,

Gitona and

Cacoxenus compared to

Leucophenga. However, the wing proportions do not show this because of the clearer separation of

Gitona by the second principal component.

In the following, we will analyse which changes in the wing proportions have taken place in the course of evolution.

Proportional Shifts in the Drosophilidae Wing

PCA is a linear method for dimension reduction. It is not possible to place the objects (the wings) in the original feature space, simply because this would have 55 dimensions in our case. We therefore try to explain the data variance as well as possible with as few orthogonal principal components or dimensions (axes) as possible. While the characters can correlate with each other, this does not apply to the PCs. In the present case, eleven dimensions would be almost as good as 55, but two to a maximum of three dimensions must suffice for a clear presentation, which means, however, that we only capture slightly more than 50% of the variance with the two-dimensional presentation (Appendix 1; strictly speaking, the presentation in Appendix 1 is three-dimensional, whereby the third dimension can be surmised from the size of the symbols. Chymomyza, for example, is in the foreground, whereas Gitona is far behind and both are therefore less similar than one might think at first glance. The first three PCs together explain about 60% of the variance).

In addition to the graphical result (Appendix 1), PCA provides a linear equation for each principal component: For each object, the position along the axis (PC) is the sum (across all features) of the products of the feature value and a constant assigned to the feature. The greater the absolute value of this constant, the more important the characteristic is for positioning along the PC. The sign indicates whether the characteristic shifts the object to higher or lower values of the principal component.

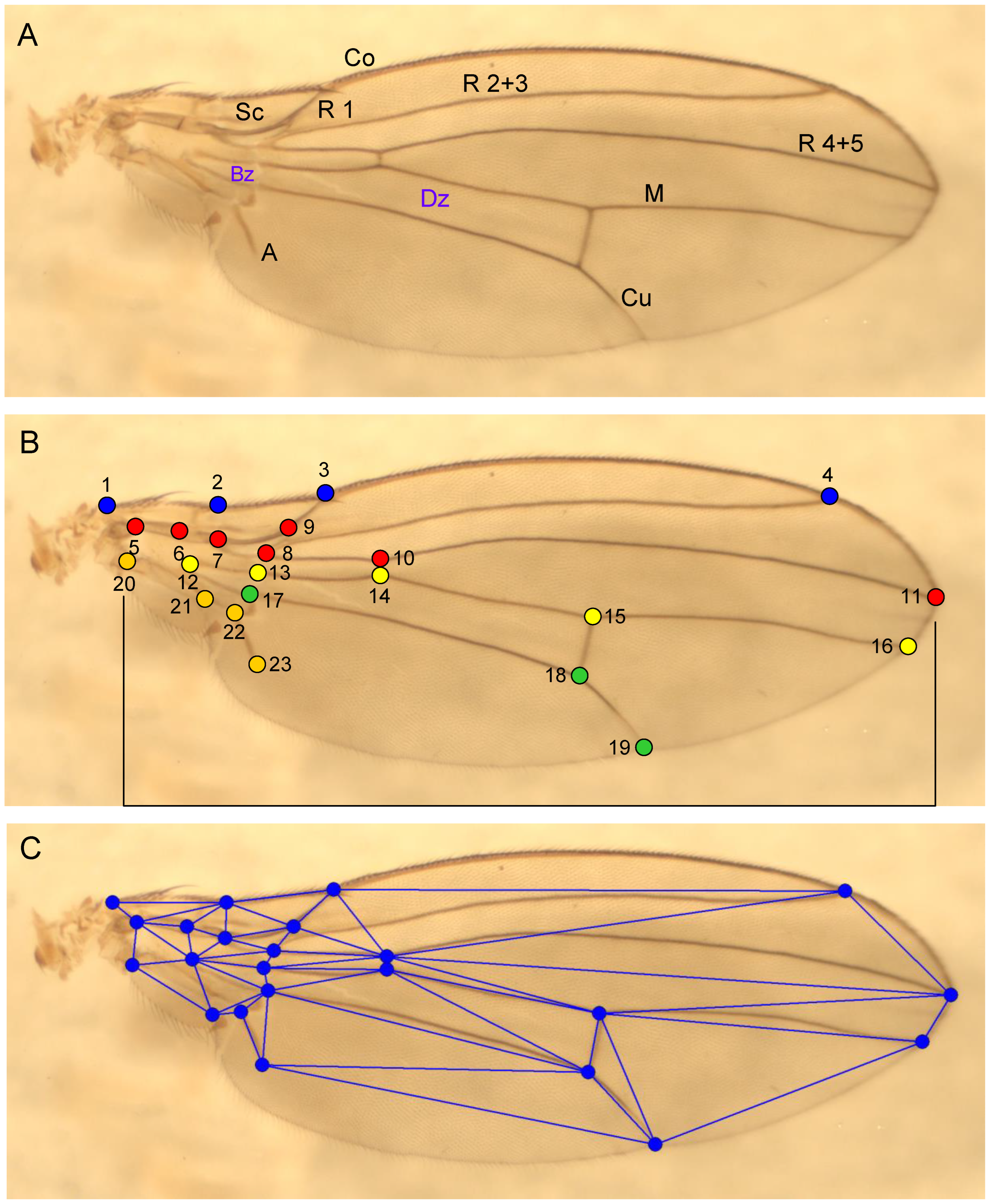

In

Figure 4a, all features for PC1 whose constant reaches an absolute value greater than 0.1 are drawn as a line, yellow if the value is positive, blue if it is negative (the threshold value is chosen freely). Particularly important are the lines that frame the basal cell that lies between radius 4+5 and media, with values greater than 0.2, as well as the line that connects nodes 4 and 10 (

Figure 2). In this illustration, the wing is divided into two areas, one proximal (basal) and one mediodistal. The border between the two runs from the distal end of the second costal segment to the distal area of the wing cell located between the radius 4+5 and the media and further to the distal end of the analis (

Figure 4). With increasing PC1 values, the proportions shift, with the proximal area becoming longer and wider and the mediodistal area shorter. This is shown in

Figure 4b & 4c by comparing two species that assume extremely different positions along PC1:

A. (P.) variegata (PC1 ≈ 10) and

S. pallida (PC1 ≈ -7). As

Figure 3 and Appendix 1 show, the representatives of the subfamily Steganinae generally have positive PC1 values, i.e., a comparatively broad and long wing base at the expense of the peripheral wing area. The Ia Drosophila cluster and

D. hydei are in the middle range near PC1 ≈ 0, while all other Drosophilinae have negative PC1 values, which are particularly negative for

Scaptomyza,

Hirtodrosophila and

Chymomyza. The evolution of the family Drosophilidae therefore probably began with a pronounced wing base and then, in some groups, proceeded to varying degrees in the direction of a proportional reduction of this part of the wing.

If the same procedure is applied to PC2, two wing sections are obtained, too; the boundary between them is diagonal to the longitudinal axis of the wing. It runs from the edge of radius 2+3 to the distal border of the discoid cell (

Figure 2) and further to the edge of the cubitus. This divides the wing into a medial and a distal section, as the wing base is hardly involved. The medial wing section ends towards the joint at the break from the second to the third costal segment, continues to the distal area of the basal cell and from there to the distal end of the analis (

Figure 5a). The proximal wing area is very little involved in the wing variability described by PC2, only through a small basal area between the media and cubitus. The boundary between proximal and medial does not correspond exactly to that defined by PC1.

With increasing values of PC2, the medial wing section becomes longer, especially in the posterior region (the localisation refers to the spread wing). As a result, the distal section becomes smaller and narrower posteriorly, which also applies to a small quadrangle in the wing base (comparison of

Figure 5b and 5c). This proportion shift is exemplified in

D. hydei, with an extremely positive PC2 value (PC2 > 4) and in

G. distigma (PC2 < -7), with a very low value. The proportion shift has apparently arisen several times independently and in parallel and, apart from

Gitona, is also very large in

Chymomyza, although these two genera are probably not closely related (and very different concerning PC3).

It is known from D. hydei that at least the pupa shows adaptations to strong wind conditions (Monier et al. 2024). A relatively small, distal wing section may be an advantage here. Within Drosophila, the subgenera Sophophora and Dorsilopha differ from the other species by lower PC2 values and therefore a reduced medial wing section compared to the distal one. This also applies to Scaptodrosophila.

The wing length has an influence on the position along PC2 as well. On average, it increases with larger values of the second principal component (exception: Gitona).

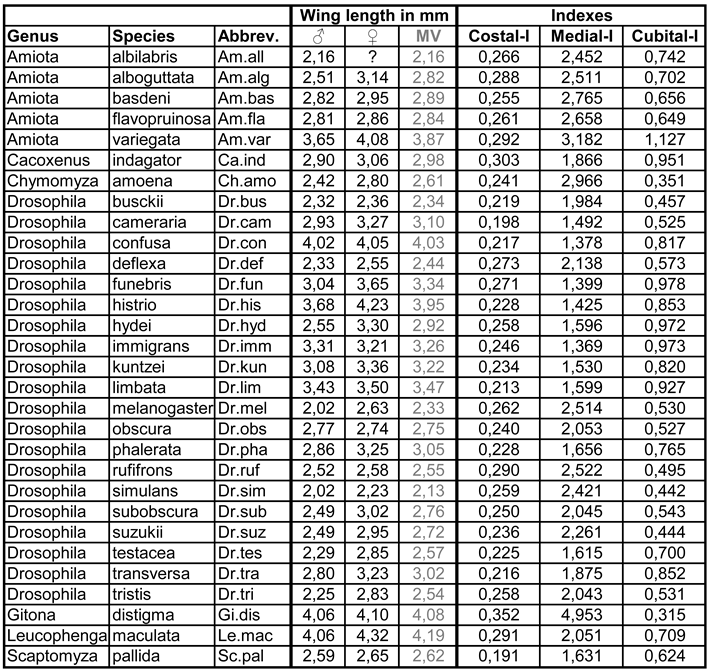

Wing Length

The wing length is also important for the arrangement of the species along PC2 in

Figure 3. For this reason, it is listed separately for the species by sex in

Table 2 (the table also shows the wing indices) and sorted in ascending order according to the mean value in Appendix 2. Accordingly,

D. simulans,

D. melanogaster (only slightly over 2 mm) and

D. busckii have the shortest wings, while

A. (P.) variegata,

D. histrio,

D. (H.) confusa,

G. distigma and

L. maculata have the longest. In the last three species mentioned, the wings are almost twice as long as in

D. simulans. Whether the wings of the females of

D. melanogaster are actually significantly longer than those of

D. simulans must first be analysed in a larger sample. The greatest difference between the sexes was found in

D. hydei, but this too may be a coincidence, as the wing size also changes seasonally and the time of collection was not taken into account when selecting the wings.

Table 2.

Wing length in mm (MV = mean value) and wing indices. For a table sorted by wing length in ascending order, see Appendix 2.

Table 2.

Wing length in mm (MV = mean value) and wing indices. For a table sorted by wing length in ascending order, see Appendix 2.

To summarise, the similarity of wing proportions among the species reflects surprisingly well most of the assumptions on the phylogeny of the Drosophilidae made by Throgmorton in 1975. All species of the subfamily Steganinae have positive PC1 values, which distinguishes them from the Drosophilinae, and apart from the genus Gitona, all Steganinae are similar in terms of wing proportions. The genus Drosophila breaks down into clusters corresponding to the assumed radiations and its species show similarities to species of other genera, such as

Hirtodrosophila, Scaptomyza and

Chymomyza, which match Throgmorton’s phylogenetic tree:

Hirtodrosophila clusters with

Scaptomyza and the immigrans-tripunctata radiation, while

Chymomyza shows similarities to the obscura and melanogaster species groups of the Sophophora radiation. For

D. busckii as part of the obscura cluster (Ib in

Figure 3), however, the cladogram of Yassin 2013 is more consistent. Yassin also mentions homologisation difficulties with the genital armatures that are important for the reconstruction of the phylogeny, so that perhaps even the positioning of

D. suzukii in Ib (

Figure 3) could correspond to evolutionary reality.

In any case, the principal components of this pterometric analysis differ from the mostly nominal or ordinal morphological characters often used today to reconstruct phylogeny in that they are not correlated with each other, whereas this is very often the case with qualitative morphological characters to an unknown extent. It can be assumed that this coherence can certainly be a major source of error in the construction of cladograms. On the other hand,

Figure 3 contains no indication of the time axis, i.e., the origin of the radiation, and thus metric wing characters alone are certainly not sufficient for a reconstruction of the phylogeny of the Drosophildae.