Submitted:

09 January 2025

Posted:

10 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background Information and Problem Statement

1.2. Literature Review

1.3. Research Objectives

- To offer a simplified method for collecting community needs and perspectives on public spaces, enabling these insights to be effectively combined with metrics and viewpoints from policymakers and decision-makers. By bridging the gap between community feedback and official evaluations, this approach facilitates more informed, responsive urban planning and fosters better alignment between public expectations and policy initiatives.

- To develop a concise questionnaire for collecting essential data on the quality of public spaces (e.g., squares, parks) as a practical and user-friendly tool for public space evaluation.

- To ensure the questionnaire is brief and accessible, citizens can complete it either through a short on-site interaction during their use of the space or online.

- To provide a foundational structure for the questions, ensuring adaptability to different contexts and needs.

- To establish guidelines for assessing public space quality, focusing on gathering data about the current conditions, identifying vulnerabilities, exploring potential interventions based on user needs, and comparing outcomes before and after any renovations.

- To analyze the collected data through a real case study, extracting useful insights that can inform evidence-based improvements and planning decisions.

1.4. Structure of the Paper

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Questionnaire Development

2.3. Evidence Generation

2.4. Questionnaire Structure

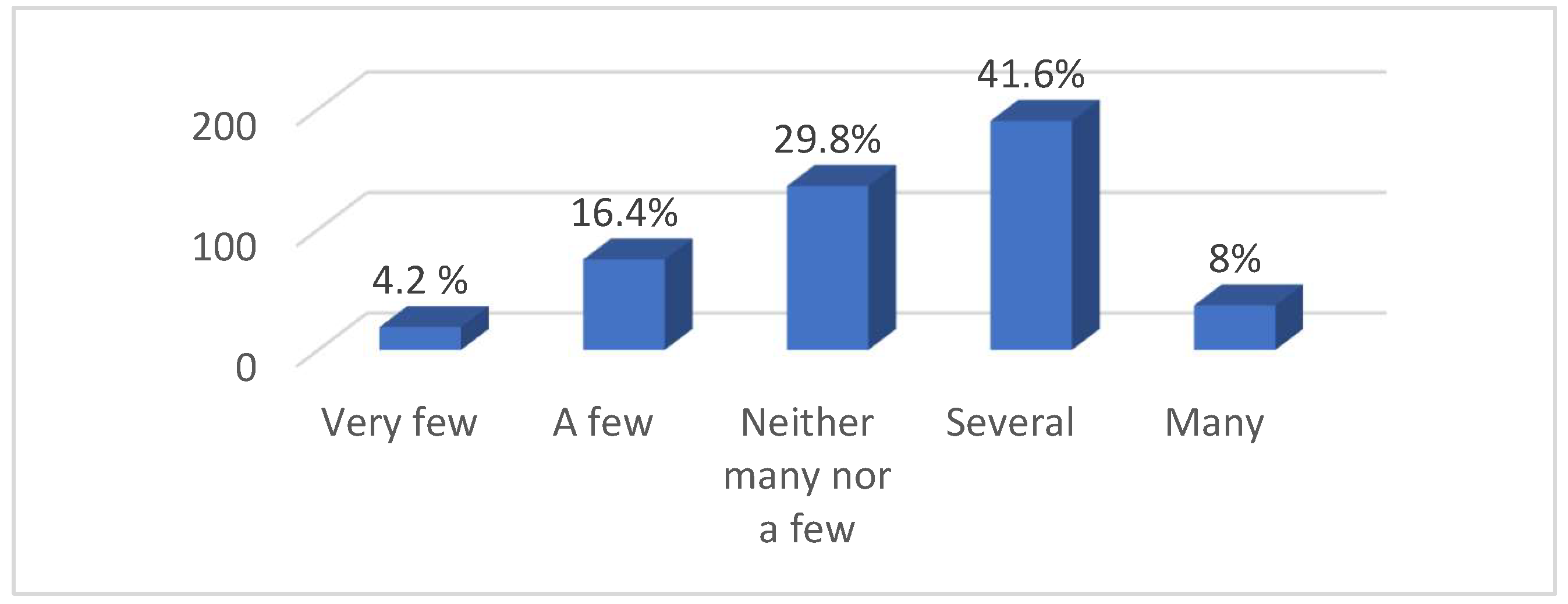

- Sufficiency and quality of public spaces

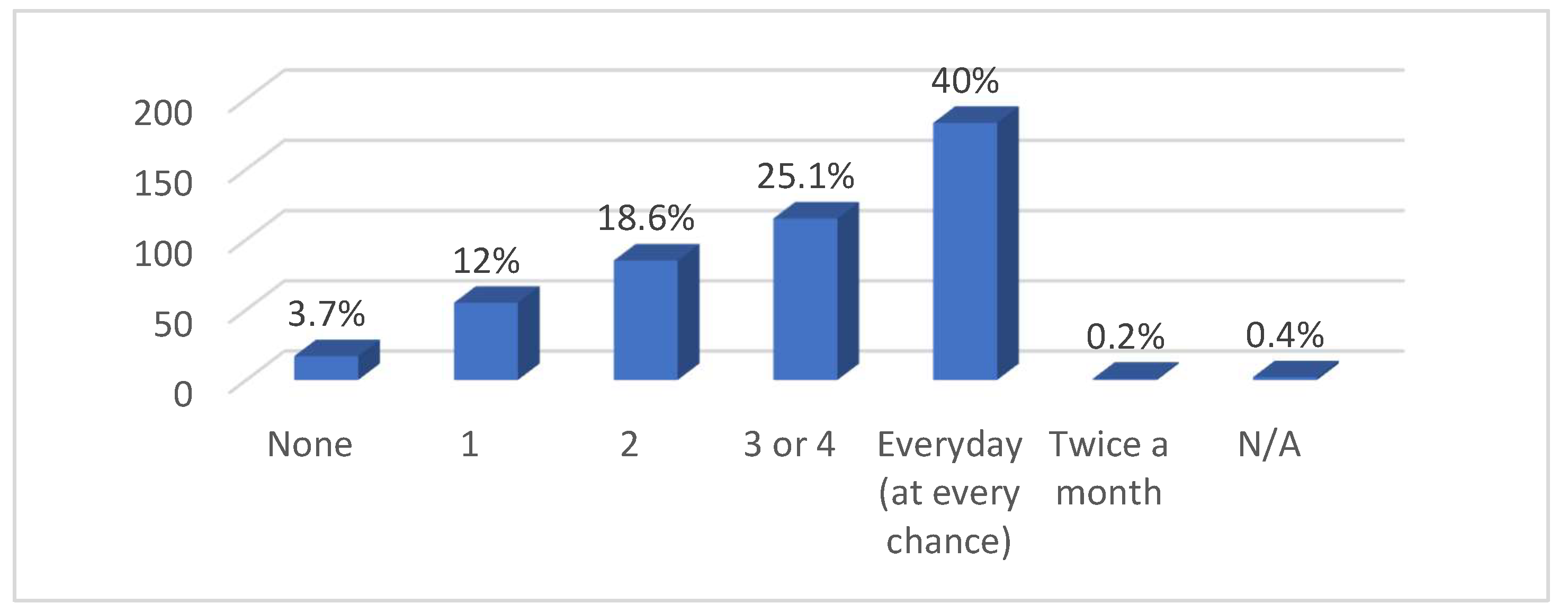

- Frequency of use/visits

- Awareness of upcoming renewals or urban developments

- Receptiveness to planned metro extensions

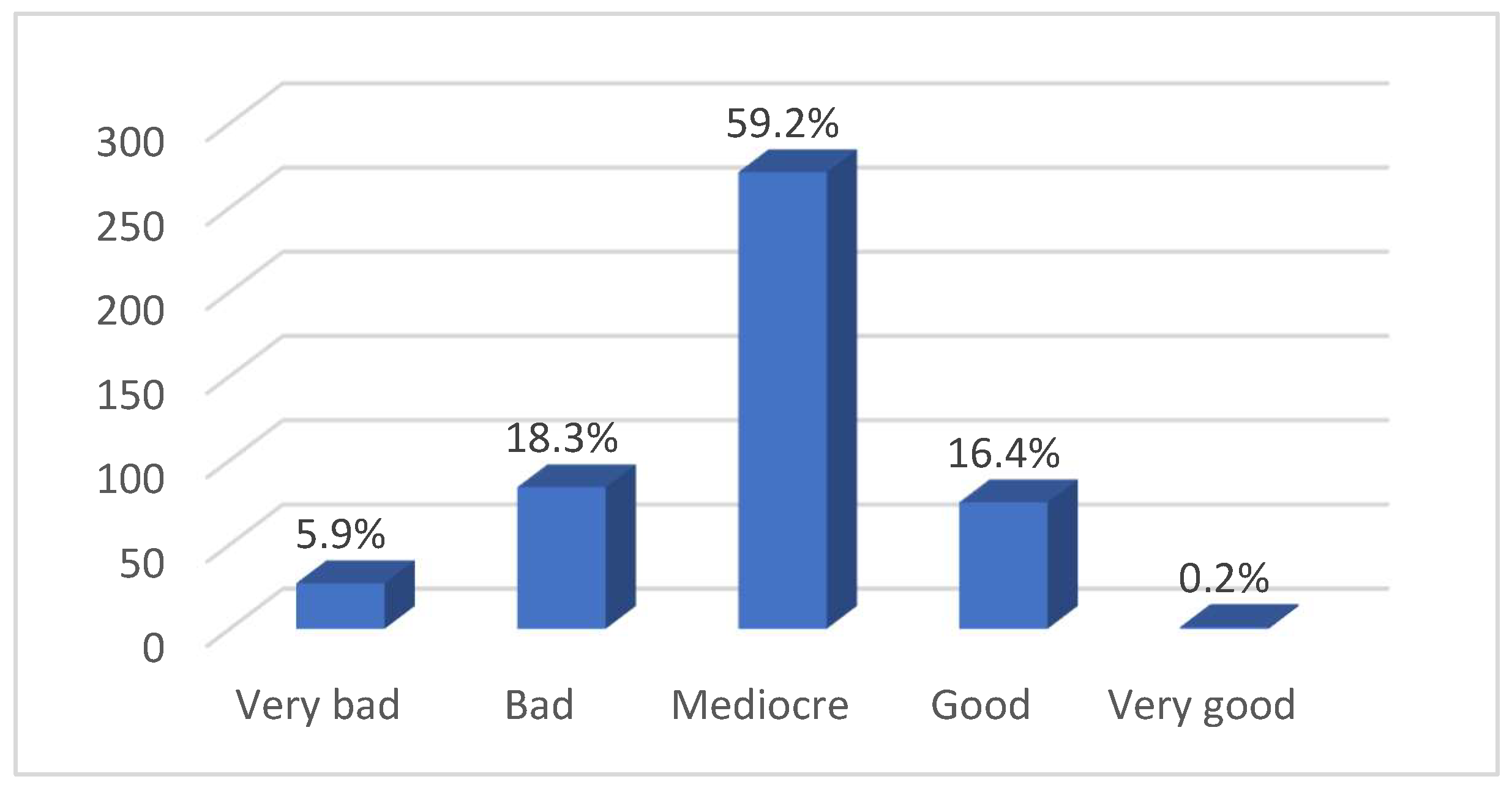

- The overall quality of the space

- Accessibility and walkability

- Safety during both day and night

- Quality of urban equipment (benches, bins, lighting, flooring)

- Quantity and quality of greenery/vegetation

- Open-ended improvement suggestions (“If I could improve something in this space, it would be...”)

- Evaluation of the space’s role in contributing to the identity of the city/neighborhood

- Reporting any negative experiences

- Gender identity

- Age

- Presence of disabilities

- Parental status (whether participants had minor children)

- Educational background

- Relationship with the municipality (whether participants were permanent residents, worked in the area, or frequently visited for other reasons)

2.5. Study Population and Data Collection

2.6. Validation Process

- Reliability Testing: Cronbach’s alpha was used to assess the internal consistency of the questions about the quality of Kaisariani Square, ensuring that the items within each construct were measuring the same underlying concept. This method also helped evaluate the potential impact of any missing questions on the overall reliability of the scale.

- Factor Analysis: Factor analysis was conducted to explore the dimensional structure of the questionnaire, determining which items clustered together to form significant constructs related to public space quality.

- Content Validity: Expert reviews and pretests were carried out to ensure that the questionnaire adequately measured the intended factors related to the quality of urban spaces. This ensured that the content covered all relevant aspects of the study’s objectives.

- Construct Validity: The questionnaire was tested against existing theories and measures of urban space quality to confirm that it accurately reflected the constructs it aimed to measure. This process helped ensure that the instrument was aligned with established research in urban planning and public space analysis.

- Quantitative Variables: Expressed as mean (Standard Deviation) to summarize central tendencies and variability.

- Qualitative Variables: Reported as absolute and relative frequencies to provide an overview of categorical data distributions.

- Spearman Correlation Coefficients: Used to assess the correlation between ordinal variables, such as the relationship between frequency of use and perceived quality of public spaces.

- Kruskal-Wallis Test: This non-parametric test was employed to compare qualitative variables across more than two groups, ensuring robust comparisons across different segments of the population.

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cabe Space. The Value of Public Space. Exch. Organ. Behav. Teach. J. 2013, 19.

- Aram, F.; Solgi, E.; García, E. H.; Mosavi, A.; Várkonyi-Kóczy, A. R. The Cooling Effect of Large-Scale Urban Parks on Surrounding Area Thermal Comfort. Energies 2019, 12 (20), 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Burnett, H.; Olsen, J. R.; Nicholls, N.; Mitchell, R. Change in Time Spent Visiting and Experiences of Green Space Following Restrictions on Movement during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Nationally Representative Cross-Sectional Study of UK Adults. BMJ Open 2021, 11 (3). [CrossRef]

- Giannico, V.; Spano, G.; Elia, M.; D’Este, M.; Sanesi, G.; Lafortezza, R. Green Spaces, Quality of Life, and Citizen Perception in European Cities. Environ. Res. 2021, 196 (December 2020), 110922. [CrossRef]

- Maruani, T.; Amit-Cohen, I. Open Space Planning Models: A Review of Approaches and Methods. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2007, 81 (1–2), 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Dalman, M.; Salleh, E.; Sapian, A. R.; Saadatian, O. Thermal Comfort Investigation in Traditional and Modern Urban Canyons in Bandar Abbas, Iran. Pertanika J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2013, 21 (4), 1491–1515.

- Rossini, F.; Nervino, E. City Branding and Public Space. An Empirical Analysis of Dolce & Gabbana’s Alta Moda Event in Naples. J. Public Sp. 2019, 4 (4), 61–82. [CrossRef]

- Walla A. Yakoub; Mahmoud Fouad Mahmoud; Osama M. Abou Elenien; Ghada Mohammad Elrayies. Ambassadors of Sustainability: An Analytical Study of Global Eco-Friendly Cities. Second Int. Conf. (Tenth Conf. Sustain. Environ. Dev. 16-20 March 2019At Sharm El Sheikh, Egypt 2019, No. March, 16–20.

- Chitrakar, R. M.; Baker, D. C.; Guaralda, M. Emerging Challenges in the Management of Contemporary Public Spaces in Urban Neighbourhoods. Archnet-IJAR 2017, 11 (1), 29–43. [CrossRef]

- Mela, A.; Vryzidis, I.; Varelidis, G.; Tsotsolas, N. Urban Space Quality Evaluation Using Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis-Based Framework. Mult. Criteria Decis. Mak. 2023, Part F1272, 59–84. [CrossRef]

- Ghel, J.; Jvare, B. How To Study Public Life; 2013.

- Mela, A.; Varelidis, G. Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Use and Attitudes Towards Urban Public Spaces. J. Sustain. Archit. Civ. Eng. 2022, 31 (2), 85–95. [CrossRef]

- Ho, R.; Au, W. T. Scale Development for Environmental Perception of Public Space. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11 (November). [CrossRef]

- Gonsalves, K.; Caldwell, G. A.; Foth, M. The Praxis of Radical Placemaking. Front. Comput. Sci. 2023, 5. [CrossRef]

- Ataman, C.; Tuncer, B. Urban Interventions and Participation Tools in Urban Design Processes: A Systematic Review and Thematic Analysis (1995–2021). Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 76 (October). [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities; Vintage, 1961.

- Lynch, K. The Image of The City; 1960.

- İnceoğlu, M.; Aytuğ, A. The Concept of Urban Space Quality. MEGARON 2009, 4 ((3) January), 131–146.

- UN-Habitat. The New Urban Agenda; 2020.

- Ghel, J. Cities for People; ISLANDPRESS: Washington l Covelo l London, 2010; Vol. 21.

- Whyte, W. The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces City : Rediscovering the Center. Washingt. Conserv. Found. D.C. 1980, VIII (1).

- Carr, S.; Francis, M.; Rivlin, L. G.; Stone, A. M. Needs in Public Space. In M. Carmona, & S. Tiesdell (Eds.). Urban Des. Reader, Oxford, UK Archit. Press 1992, 230–240.

- Carmona, M.; Tiesdell, S.; Heath, T.; Oc, T. Public Places Urban Spaces. The Dimensions of Urban Design, New York Londra. Archit. Press 2003, 2.

- Herthogs, P.; Tunçer, B.; Schläpfer, M.; He, P. A Weighted Graph Model to Estimate People’s Presence in Public Space The Visit Potential Model. Proc. Int. Conf. Educ. Res. Comput. Aided Archit. Des. Eur. 2018, 2, 611–620. [CrossRef]

- Hespanhol, L. Making Meaningful Spaces : Strategies for Designing Enduring Digital. Int. Conf. Des. Innov. Creat. 2018, No. July, 108–117.

- Montgomery, J. Making a City: Urbanity, Vitality and Urban Design. J. Urban Des. 1998. [CrossRef]

- Gehl Institute. Twelve Quality Criteria; 2018.

- He, P.; Herthogs, P.; Cinelli, M.; Tomarchio, L.; Tunçer, B. A Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis Based Framework to Evaluate Public Space Quality. Smart Sustain. Cities Build. 2020, No. December, 271–283. [CrossRef]

- Mohajerani, A.; Bakaric, J.; Jeffrey-Bailey, T. The Urban Heat Island Effect, Its Causes, and Mitigation, with Reference to the Thermal Properties of Asphalt Concrete. J. Environ. Manage. 2017, 197, 522–538. [CrossRef]

- Adams, M. D. Wellbeing and the Environment: Wellbeing: A Complete Reference Guide, Volume II. Edited by Rachel Cooper, Elizabeth Burton, and Cary L. Cooper. Wellbeing 2014, II, 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Venot, F.; Sémidor, C. The “Soundwalk” as an Operational Component for Urban Design. PLEA 2006—23rd Int. Conf. Passiv. Low Energy Archit. Conf. Proc. 2006, No. September, 6–8.

- Syarlianti, D. Identifying Great Street in Bandung as Part of Bandung Technopolis Concept: A Perception-Based Approach. IPTEK J. Proc. Ser. 2017, 0 (3). [CrossRef]

- Coleman, A. F.; Ryan, R. L.; Eisenman, T. S.; Locke, D. H.; Harper, R. W. The Influence of Street Trees on Pedestrian Perceptions of Safety: Results from Environmental Justice Areas of Massachusetts, U.S. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 64 (July), 127258. [CrossRef]

- Davies, W. J.; Adams, M. D.; Bruce, N. S.; Cain, R.; Carlyle, A.; Cusack, P.; Hall, D. A.; Hume, K. I.; Irwin, A.; Jennings, P.; Marselle, M.; Plack, C. J.; Poxon, J. Perception of Soundscapes: An Interdisciplinary Approach. Appl. Acoust. 2013, 74 (2), 224–231. [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.; Evans, S. Z.; Morgan, J. D.; Snyder, J. A.; Abderhalden, F. P. Evaluating the Quality of Mid-Sized City Parks: A Replication and Extension of the Public Space Index. J. Urban Des. 2019, 24 (1), 119–136. [CrossRef]

- Mehta, V. Evaluating Public Space. J. Urban Des. 2014, 19 (1), 53–88. [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.; Evans, S. Z.; Morgan, J. D.; Snyder, J. A. Evaluating the Quality of Mid-Sized City Parks : A Replication and Extension of the Public Space Index. J. Urban Des. 2018, 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Allahbakhshi, H. Towards an Inclusive Urban Environment: A Participatory Approach for Collecting Spatial Accessibility Data in Zurich. Leibniz International Proceedings in Informatics, LIPIcs. Schloss Dagstuhl—Leibniz-Zentrum für Informatik, Dagstuhl Publishing, Germany 2023, pp 13:1-13:0. [CrossRef]

- Lopes, M.; Alves, F. Digital Tools to Foster Inclusiveness: Porto’s System of Accessible Itineraries. Sustain. 2021, 13 (11). [CrossRef]

- Dhasmana, P.; Bansal, K.; Kaur, M. Assessing Gender Inclusive User Preferences: A Case of Urban Public Spaces in Chandigarh. 2022 Int. Conf. Innov. Intell. Informatics, Comput. Technol. 3ICT 2022 2022, No. November 2022, 221–226. [CrossRef]

- Selanon, P.; Puggioni, F.; Dejnirattisai, S. An Inclusive Park Design Based on a Research Process: A Case Study of Thammasat Water Sport Center, Pathum Thani, Thailand. Buildings 2024, 14 (6). [CrossRef]

- Ikudayisi, A. E.; Taiwo, A. A. Accessibility and Inclusive Use of Public Spaces within the City-Centre of Ibadan, Nigeria. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2022, 15 (3), 316–335. [CrossRef]

- Mrak, I.; Campisi, T.; Tesoriere, G.; Canale, A.; Cindrić, M. The Role of Urban and Social Factors in the Accessibility of Urban Areas for People with Motor and Visual Disabilities. AIP Conf. Proc. 2019, 2186 (December). [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A. M.; Abdelkarim, S.; Al-Nuaimi, M.; Makhoul, N.; Mathew, L.; Garba, S. Inclusiveness Assessment Tool for Disabled Persons in Higher Education Facilities. J. Facil. Manag. 2024, 22 (2), 210–233. [CrossRef]

- Belaroussi, R.; Sitohang, I.; Diaz Gonzalez, E. M.; Martin-Gutierrez, J. Cross-Cultural Aspects of Streetscape Perception. Vitruvio 2024, 9 (1), 114–129. [CrossRef]

- Rebecchi, A. Cities, Walkability and Health. A Multi-Disciplinary Walking Experience at EPH22 in Berlin Andrea. Andrea 2023, 33.

- Carmona, M. Contemporary Public Space: Critique and Classification, Part One: Critique. J. Urban Des. 2010, 15 (1), 123–148. [CrossRef]

- Kaghouche, M.; Benkechkache, I. Assessment of the Quality of Public Spaces in the New City of Ali Mendjeli in Constantine (Algeria). Bull. Serbian Geogr. Soc. 2023, 103 (2), 161–176. [CrossRef]

- Praliya, S.; Garg, P. Public Space Quality Evaluation : Prerequisite for Public Space Management. 2019, 4, 93–126. [CrossRef]

- Sayad, B.; Alkama, D. Assessment of the Environmental Quality through Users’ Perception in Guelma City, Algeria. 2021, No. May, 182–187. [CrossRef]

- Rad, V. B.; Ngah, I. Bin. Assessment of Quality of Public Urban Spaces. Sci.Int(Lahore) 2014, 26 (1), 335–338.

- Mela, A.; Tousi, E. Safe and Inclusive Urban Public Spaces: A Gendered Perspective. The Case of Attica ’s Public Spaces During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Greece. J. Sustain. Archit. Civ. Eng. 2023, 2 (33), 5–14. [CrossRef]

- Namar, J. M.; Salheen, M. A.; Ismail, A. Investigating Users Changing Needs in Relation to Non-Designed or Unplanned Public Spaces in Cairo. J. Public Sp. 2021, 6 (Vol. 6 n. 1), 47–66. [CrossRef]

- Chęć-Małyszek, A. Criteria of Livable Public Spaces Quality . Case Study Analysis on the Example of Selected Public Spaces Lublin, Poland. Geography 2022.

- Chen, Y.; Ge, Y.; Yang, G.; Wu, Z.; Du, Y.; Mao, F.; Liu, S.; Xu, R.; Qu, Z.; Xu, B.; Chang, J. Inequalities of Urban Green Space Area and Ecosystem Services along Urban Center-Edge Gradients. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2022, 217 (October 2021), 104266. [CrossRef]

- Dillman, D. A.; Smyth, J. D.; Christian, L. M. Internet, Phone, Mail, and Mixed Mode Surveys: The Tailored Design Method (4th Ed.), 4th ed.; John Wiley & Sons Inc, Ed.; 2014.

- Floyd J. Fowler. Survey Research Methods.; Sage publications, 2013.

- Gallagher, P. M.; Fowler, F. J.; Stringfellow, V. L. Notes from the Field: Experiments in Influencing Response Rates from Medicaid Enrollees. Center for Survey Research. 2002, pp 971–976.

- Larsen, M. D.; Rasinski, K. The Psychology of Survey Response. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2002. [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. Long survey lengths lead to bad data—Here are 11 ways to keep your survey short. milieu. https://www.mili.eu/learn/survey-length-11-best-practice-tips-to-keep-surveys-short.

- Municipality of Kaisariani. Municipality of Kaisariani. wikipedia. https://el.wikipedia.org/wiki/Καισαριανή.

- Tousi, E. Urban Socio-Spatial Transformations in Light of the Asia Minor Refugee Issue. The Case of the Urban Agglomeration of Athens –Piraeus, NTUA, 2014. https://www.didaktorika.gr/eadd/handle/10442/42796.

- Mela, A.; Tousi, E.; Melas, E.; Varelidis, G. Spatial Distribution and Quality of Urban Public Spaces in the Attica Region (Greece) during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Survey-Based Analysis. Urban Sci. 2023, 8 (1), 2. [CrossRef]

- Kyriakidis, C.; Bakogiannis, E. An Evaluation of Urban Open Spaces in Larisa, Greece. Eur. J. Form. Sci. Eng. 2018, 1 (1), 17. [CrossRef]

- Karanikola, P.; Panagopoulos, T.; Tampakis, S.; Karipidou-Kanari, A. A Perceptual Study of Users’ Expectations of Urban Green Infrastructure in Kalamaria, Municipality of Greece. Manag. Environ. Qual. An Int. J. 2016, 27 (5), 568–584. [CrossRef]

- Tousi, E.; Mela, A. Supralocal Role of Medium to Large Scale Urban Parks, in Attica Greece. Issues of Meso Car Dependence during the Covid-19 Pandemic. (Pending Publication 2023-2024). J. Sustain. Archit. Civ. Eng. 2024, 2 (35), 201–215. [CrossRef]

- Sturiale, L.; Scuderi, A.; Timpanaro, G. A Multicriteria Decision-Making Approach of “Tree” Meaning in the New Urban Context. Sustain. 2022, 14 (5). [CrossRef]

- Sturiale, L. The Role of Green Infrastructures in Urban Planning for Climate Change Adaptation. 2019.

- Lee, Y.; Gu, N.; An, S. Residents’ Perception and Use of Green Space: Results from a Mixed Method Study in a Deprived Neighbourhood in Korea. Indoor Built Environ. 2017, 26 (6), 855–871. [CrossRef]

- Arvanitidis, P. A.; Papagiannitsis, G. Urban Open Spaces as a Commons: The Credibility Thesis and Common Property in a Self-Governed Park of Athens, Greece. Cities 2020, 97 (July 2019), 102480. [CrossRef]

- Kothencz, G.; Blaschke, T. Urban Parks: Visitors’ Perceptions versus Spatial Indicators. Land use policy 2017, 64, 233–244. [CrossRef]

- Kothencz, G.; Kolcsár, R.; Cabrera-Barona, P.; Szilassi, P. Urban Green Space Perception and Its Contribution to Well-Being. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14 (7). [CrossRef]

- Silva, J. P.; Toland, J.; Jones, W.; Eldridge, J.; Hudson, T.; O’Hara, E.; Thévignot, C.; Salsi, A.; Jussiant, E. Nature LIFE Building up Europe’s Green Infrastructure; 2010. [CrossRef]

- Vukmirovic, M.; Gavrilovic, S.; Stojanovic, D. The Improvement of the Comfort of Public Spaces as a Local Initiative in Coping with Climate Change. Sustain. 2019, 11 (23), 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.; Gao, M.; Luo, D.; Zhou, X. Urban Parks—A Catalyst for Activities! The Effect of the Perceived Characteristics of the Urban Park Environment on Children’s Physical Activity Levels. Forests 2023, 14 (2), 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Lak, A.; Aghamolaei, R.; Baradaran, H. R.; Myint, P. K. Development and Validation of Elder- Friendly Urban Spaces Questionnaire ( EFUSQ ). 2019, 1–14.

- Szczepańska, A.; Pietrzyk, K. Seasons of the Year and Perceptions of Public Spaces. Landsc. J. 2021, 40 (2), 19–35. [CrossRef]

- Czepkiewicz, M.; Jankowski, P.; Młodkowski, M. Geo-Questionnaires in Urban Planning: Recruitment Methods, Participant Engagement, and Data Quality. Cartogr. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2017, 44 (6), 551–567. [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, A.; Alalouch, C.; Bramley, G. Open Space Quality in Deprived Urban Areas: User Perspective and Use Pattern. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 216, 194–205. [CrossRef]

- Quercia, D.; Aiello, L. M.; Schifanella, R.; Davies, A. The Digital Life of Walkable Streets. WWW 2015—Proc. 24th Int. Conf. World Wide Web 2015, No. March, 875–884. [CrossRef]

- Perini, K.; Chokhachian, A.; Dong, S.; Auer, T. Modeling and Simulating Urban Outdoor Comfort: Coupling ENVI-Met and TRNSYS by Grasshopper. Energy Build. 2017, 152, 373–384. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Feng, L. Evaluation and Optimization of Children’s Recreational Center in Urban Green Public Space Based on AHP-TOPSIS. Journal of Applied Sciences. 2013, pp 895–900. [CrossRef]

- Aliyas, Z.; Gharaei, M. Utilization and Physical Features of Public Open Spaces in Bandar Abbas, Iran. IIOAB J. · 2016, 7 (October 2016), 178–183.

- ordin, N. N.; Abd Malek, M. I. Quality and Potential for Public Open Space Typology Underneath the Flyover in the Context of Old Town Kuala Lumpur Case Study: Pasar Seni LRT Area. J. Kejuruter. 2022, 34 (2), 277–298. [CrossRef]

- Rossignolo, C.; Saccomani, S. Evidence and Methods from an Educational Experience about Area- Based Urban Regeneration. In “From control to co-evolution”, AESOP Annual Congress tenutosi a Utrecht nel 9-12 July 2014); 2014.

- Oh, J.; Seo, M. Evaluation of Citizen–Student Cooperative Urban Planning and Design Experience in Higher Education. Sustain. 2022, 14 (4), 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. Y.; Kim, J. H.; Seo, K. W. The Perception of Urban Regeneration by Stakeholders: A Case Study of the Student Village Design Project in Korea. Buildings 2023, 13 (2). [CrossRef]

- Mullenbach, L. E.; Baker, B. L.; Benfield, J.; Hickerson, B.; Mowen, A. J. Assessing the Relationship between Community Engagement and Perceived Ownership of an Urban Park in Philadelphia. J. Leis. Res. 2019, 50 (3), 201–219. [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R. Citizen Participation in Design and Evaluation of a Park. Environ. Behav. 1980.

- Soares, I.; Weitkamp, G.; Yamu, C. Public Spaces as Knowledgescapes: Understanding the Relationship between the Built Environment and Creative Encounters at Dutch University Campuses and Science Parks. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17 (20), 1–30. [CrossRef]

- Sanches, D.; Lessa Ortiz, S. R. The Design of Co-Participation Processes in Public Spaces in São Paulo as University Extension Project: The Revitalization Process of Dom Orione and Major Freire Squares. 2020, 4, 125–136. [CrossRef]

| Socio-demographic characteristics | N (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender identity | ||

| Women | 310 (67.7) | |

| Men | 146 (31.9) | |

| Non-binary/Other | 2 (0.4) | |

| Age (years) | ||

| 18-30 | 49 (10.7) | |

| 31-40 | 75 (16.4) | |

| 41-50 | 118 (25.8) | |

| 51-60 | 106 (23.1) | |

| >60 | 108 (23.6) | |

| Having underaged children | ||

| None | 278 (60.7) | |

| 1 child | 79 (17.2) | |

| 2 children | 78 (17.0) | |

| >3 children | 15 (3.3) | |

| N/A | 1 (0.2) | |

| Educational level | ||

| Primary school | 21 (4.6) | |

| Secondary school | 26 (5.7) | |

| High school | 102 (22.3) | |

| Institute of Vocational Training | 49 (10.7) | |

| University/ Technical University | 168 (36.7) | |

| Master’s degree | 75 (16.4) | |

| PhD | 5 (1.1) | |

| N/A | 1 (0.2) | |

| Contact with Kaisariani | ||

| Living but not working in Kaisariani | 202 (44.1) | |

| Living and working in Kaisariani | 137 (29.9) | |

| Working but not living in Kaisariani | 78 (17.0) | |

| Visiting often Kaisariani for family or business reasons | 39 (8.5) | |

| Business owner in Kaisariani | ||

| Yes | 67 (14.6) | |

| No | 385 (84.1) | |

| No, but I intend to own a business | 2 (0.4) | |

| Difficulty in mobility (in terms of disability) | ||

| Yes | 39 (8.5) | |

| Sometimes | 74 (16.2) | |

| No | 337 (73.6) | |

| Age | Business owner | Having children under 18 | Education level | |

| Amount of free public spaces | -0.105* | 0.003 | 0.071 | 0.091 |

| Quality of free public spaces | -0.022 | 0.045 | -0.116* | 0.021 |

| Times passing per week | -0.018 | 0.156*** | 0.099* | 0.058 |

| Regeneration of Kaisariani | 0.072 | -0.031 | -0.001 | -0.161*** |

| The overall quality of the square | -0.127** | 0.159*** | -0.036 | 0.016 |

| Accessibility in the square | 0.017 | 0.023 | -0.023 | -0.063 |

| Square’s safety by day | 0.027 | 0.021 | -0.105* | 0.060 |

| Square’s safety by night | -0.057 | 0.016 | -0.078 | 0.101* |

| Quality of urban equipment | -0.103* | 0.086 | -0.040 | 0.081 |

| Greennery in the square | -0.030 | 0.042 | -0.099* | -0.128** |

| Square as an “identity element” of Kaisariani | 0.192*** | 0.029 | 0.027 | -0.081 |

| Skopeftirio an “identity element” of Kaisariani | 0.049 | 0.050 | -0.006 | 0.071 |

| Opinion about the metro station in Kaisariani | 0.207*** | 0.071 | 0.000 | -0.007 |

| Women | Men | Non-binary/Other | Total | |

| Ν (%) | Ν (%) | Ν (%) | Ν (%) | |

| Better accessibility/walkability | 118 (38.2) | 62 (42.8) | 1 (50.0) | 181 (39.7) |

| Inspire a greater sense of safety | 115 (37.2) | 49 (33.8) | 0 (0.0) | 164 (36.0) |

| Has better lighting | 170 (55.0) | 77 (53.1) | 1 (50.0) | 248 (54.4) |

| Upgrading and care of the existing greennery | 244 (79.0) | 113 (77.9) | 2 (100) | 359 (78.7) |

| Water element | 118 (38.2) | 51 (35.2) | 1 (50.0) | 170 (37.3) |

| Less noise | 115 (37.2) | 57 (39.3) | 1 (50.0) | 173 (37.9) |

| Greater protection from the weather (e.g., canopy/shade, etc.) | 134 (43.4) | 54 (37.2) | 1 (50.0) | 189 (41.4) |

| More benches and rest areas | 187 (60.5) | 82 (56.6) | 2 (100) | 271 (59.4) |

| More trash cans | 153 (49.5) | 50 (34.5) | 1 (50.0) | 204 (44.7) |

| More pronounced culture and/or art | 184 (59.5) | 72 (49.7) | 2 (100) | 258 (56.6) |

| Access to free wifi | 116 (37.5) | 61 (42.1) | 1 (50.0) | 178 (39.0) |

| Exercise equipment | 43 (13.9) | 13 (9.0) | 1 (50.0) | 57 (12.5) |

| Public WC | 75 (24.3) | 47 (32.4) | 1 (50.0) | 123 (27.0) |

| Special areas for children | 145 (46.9) | 52 (35.9) | 1 (50.0) | 198 (43.4) |

| Other | 18 (5.8) | 7 (4.8) | 1 (50.0) | 26 (5.7) |

| Women | Men | Non-binary/Other | Total | |

| Ν (%) | Ν (%) | Ν (%) | Ν (%) | |

| Difficulty in crossing | 49 (15.8) | 34 (23.6) | 0 (0.0) | 83 (18.1) |

| Car Accident | 8 (2.8) | 1 (0.07) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (2.0) |

| Fall accident | 37 (11.9) | 10 (6.9) | 0 (0.0) | 47 (10.3) |

| Harassment | 11 (3.5) | 2 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | 13 (2.9) |

| Racist attack | 5 (1.6) | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (1.3) |

| Theft | 18 (5.8) | 11 (7.6) | 0 (0.0) | 29 (6.4) |

| Memory of discomfort (e.g., due to heat, cold, loud noise, etc.) | 59 (19.0) | 23 (16.0) | 1 (50.0) | 83 (18.2) |

| Fear due to lack of lighting | 46 (14.8) | 14 (9.7) | 0 (0.0) | 60 (13.2) |

| Lack of care/cleanliness | 149 (48.1) | 62 (43.1) | 1 (50.0) | 212 (46.5) |

| Other | 7 (2.3) | 3 (2.1) | 0 (0.0) | 10 (2.2) |

| No negative experience | 75 (24.2) | 38 (26.4) | 1 (50.0) | 114 (25.0) |

| Women | Men | Non-binary/Other | Total | |

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| Better accessibility/walkability | 86 (27.7) | 43 (29.9) | 1 (50.0) | 130 (28.5) |

| Inspire a greater sense of safety | 237 (76.7) | 105 (72.9) | 1 (50.0) | 343 (75.4) |

| Has better lighting | 226 (72.9) | 98 (68.1) | 2 (100) | 326 (71.5) |

| Upgrading and care of the existing greenery |

221 (71.3) | 106 (73.6) | 2 (100) | 329 (72.1) |

| Water element | 144 (46.5) | 78 (54.2) | 2 (100) | 224 (49.1) |

| Less noise | 51 (16.5) | 21 (14.6) | 0 (0.0) | 72 (15.8) |

| Greater protection from the weather (e.g., canopy/shade, etc.) |

142 (45.8) | 75 (52.1) | 2 (100) | 219 (48.0) |

| More benches and rest areas | 175 (56.5) | 82 (56.9) | 2 (100) | 259 (56.8) |

| More trash cans | 166 (53.5) | 74 (51.4) | 1 (50.0) | 241 (52.9) |

| More culture and/or art | 174 (56.1) | 81 (56.3) | 2 (100) | 257 (56.4) |

| Access to free wifi | 103 (33.2) | 54 (37.5) | 2 (100) | 159 (34.9) |

| Exercise equipment | 86 (27.7) | 47 (32.6) | 1 (50.0) | 134 (29.4) |

| Public WC | 122 (39.4) | 77 (53.5) | 1 (50.0) | 200 (43.9) |

| Special areas for children | 141 (45.5) | 73 (50.7) | 0 (0.0) | 214 (46.9) |

| Other | 33 (10.6) | 15 (10.3) | 1 (50.0) | 49 (10.7) |

| Women | Men | Non-binary/Other | Total | |

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| Difficulty in crossing | 43 (13.9) | 19 (13.2) | 0 (0.0) | 62 (13.6) |

| Car Accident | 4 (1.3) | 2 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (1.3) |

| Fall accident | 22 (7.1) | 9 (6.3) | 0 (0.0) | 31 (6.8) |

| Harassment | 51 (16.5) | 22 (15.3) | 0 (0.0) | 73 (16.0) |

| Racist attack | 12 (3.9) | 7 (4.9) | 1 (50.0) | 20 (4.4) |

| Theft | 84 (27.1) | 33 (22.9) | 1 (50.0) | 118 (25.9) |

| Memory of discomfort (e.g., due to heat, cold, loud noise, etc.) | 41 (13.2) | 20 (13.9) | 0 (0.0) | 61 (13.4) |

| Fear due to lack of lighting | 190 (61.3) | 69 (47.9) | 2 (100) | 261 (57.2) |

| Lack of care/cleanliness | 142 (45.8) | 56 (38.9) | 2 (100) | 200 (43.9) |

| Other | 12 (3.9) | 5 (3.4) | 0 (0.0) | 17 (3.7) |

| No negative experience | 50 (16.2) | 34 (23.6) | 0 (0.0) | 84 (18.5) |

| Gender | P-value Kruskal-Wallis test | ||||||

| Female | Male | Non-binary/Other | |||||

| Mean (SD) | Median | Mean (SD) | Median | Mean (SD) | Median | ||

| Existence of free public spaces | 3.34 (0.97) | 3 | 3.34 (0.99) | 4 | 3.5 (0.71) | 3.5 | 0.974 |

| Quality of free public spaces | 2.89 (0.75) | 3 | 2.84 (0.74) | 3 | 3.5 (0.71) | 3.5 | 0.273 |

| Times passing per week | 3.95 (1.18) | 4 | 3.78 (1.19) | 4 | 4 (0.00) | 4 | 0.241 |

| Regeneration of Kaisariani | 2.95 (1.25) | 3 | 3.02 (1.34) | 3 | 3 (1.41) | 3 | 0.889 |

| Quality of the square | 2.65 (0.83) | 3 | 2.57 (0.73) | 3 | 4 (0.00) | 4 | 0.025 |

| Accessibility in the square | 3 (0.89) | 3 | 3.04 (0.84) | 3 | 3 (1.41) | 3 | 0.998 |

| Square safety by day | 3.7 (0.77) | 4 | 3.74 (0.77) | 4 | 4.5 (0.71) | 4.5 | 0.253 |

| Square safety by night | 3 (0.9) | 3 | 3.1 (0.9) | 3 | 4.5 (0.71) | 4.5 | 0.063 |

| Quality of urban equipment | 2.52 (0.82) | 3 | 2.57 (0.83) | 3 | 3.5 (0.71) | 3.5 | 0.236 |

| Green in the square | 2.45 (0.9) | 2 | 2.4 (0.84) | 2 | 3 (0.00) | 3 | 0.371 |

| Square as an identity of Kaisariani | 3.83 (1.21) | 4 | 3.89 (1.21) | 4 | 4.5 (0.71) | 4.5 | 0.664 |

| Skopeftirio as an identity of Kaisariani | 4.63 (0.78) | 5 | 4.71 (0.68) | 5 | 5 (0.00) | 5 | 0.369 |

| Opinion about the metro station in Kaisariani | 4.7 (1.31) | 5 | 4.99 (1.14) | 5 | 4 (0.00) | 4 | 0.029 |

| Minimum | Maximum | Mean (SD) | Median | Cronbach’s if item deleted | Cronbach’s a | |

| Quality of free public spaces | 1 | 5 | 2.87 (0.76) | 3 | 0.776 | |

| Quality | 1 | 5 | 2.62 (0.81) | 3 | 0.745 | |

| Accessibility | 1 | 5 | 3.00 (0.88) | 3 | 0.756 | |

| Safety by day | 1 | 5 | 3.71 (0.77) | 4 | 0.766 | |

| Safety by night | 1 | 5 | 3.04 (0.91) | 3 | 0.769 | |

| Quality of urban equipment | 1 | 5 | 2.54 (0.83) | 3 | 0.755 | |

| Greennery | 1 | 5 | 2.44 (0.88) | 2 | 0.780 | |

| 0.791 | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).