Author’s Foreword

The remarkable success of molecular cell biology in recent decades has largely suppressed ideas and findings of evolutionary cancer cell biology. As a result, we still do not truly understand what cancer is or where it comes from. In retrospect, it was unwise to rely solely on the molecular approach—it alone cannot solve the mysteries of cancer.

The author of this work has extensive experience in the experimentally cell biology of protists, particularly parasitic protists that inhabit the same host environments as transformed cancer cells. The author's experimental findings on unicellular cell systems have been published in numerous peer-reviewed studies (

https://ro.wikipedia.org/ wiki/Vladimir_F._Niculescu). These studies reveal that the physiology of hypoxic-hyperoxic cell systems is shaped by the oxygen gradient within host tissue and bloodstream ranging from 0.1 to 13% oxygen content)

It has become evident that the normoxia (physioxia) of both unicellular stemgermlines of cancer and protists is in fact hypoxic, typically below 6.0% O₂. Oxygen levels above 6.0% are detrimental to stemness and stem cell generation. The widespread practice of culturing cancer cells under atmospheric oxygen (21% O₂) has significantly distorted our understanding of cancer cell physiology Research on Entamoeba has shown that varying oxygen concentrations can act as drivers, regulators, effectors, and suppressors of stemness and stemgermline evolution.

This realization prompted a comparative analysis of both parasitic cell systems. Through this lens, many unexplained phenomena in carcinogenesis and tumorigenesis could finally be deciphered. These efforts ultimately led to the development and expansion of Evolutionary Cancer Cell Biology (ECCB)—an emerging field that is now progressively gaining the attention of the scientific community.

The ECCB, founded by the author in recent years, is not just a collection of individual publications, but a comprehensive evolutionary framework for cancer cell biology—and the culmination of the author's life’s work. It focuses on the discovery that cancer arises from the genomic unicellularization of dysfunctional, stress-damaged stemgermline cells in multicellular organisms. The ECCB helps to trace the biological roots of cancer cell system across the past 1.75 billion years of evolution. This paradigm aims to fundamentally reshape our understanding of cancer by conceiving it as an inversion of ancient unicellular programs embedded in the genome of multicellular organisms.

1. Introduction to Evolutionary Cancer Cell Biology (ECCB)

Evolution has endowed multicellular life as finite, in contrast to unicellular life, which continues indefinitely through constant cell division, provided extrinsic living conditions exist.

In other words, non-limited life is a life form characteristic of unicellular organisms that has been successfully eliminated in multicellular evolution. It is rather curious that, over time, this evolutionary concept has not found its way into cancer research, and that unlimited cancer cell proliferation has been incomprehensibly regarded as a deregulated process of multicellularity rather than as a transition to unicellularity and unrestricted unicellular proliferation. One possible reason for this could be the widespread assumption that multicellular organisms, by definition, exclude the possibility of a multicellular-to-unicellular transition (MUT). Additionally, a suitable unicellular model for the cancer cell system – like its deep homologous cell system of Entamoeba - has been lacking for many years. This is the reason why cancer cell research has, to this day, failed to recognize that all processes occurring within cancer cell system—particularly the evolution of stemgermlines —are unicellular in nature and share fundamental characteristics with the parasitic cell system of Entamoeba.

The present work has two main objectives. First, to demonstrate how and when dysfunctional, stress-damaged stemgermline genomes can be repaired in the context of restorative senescence (RS) and unicellularization. Second to explore stemness loss and recovery in tumors.

But first, a brief exposé from the perspective of evolutionary cancer cell biology (ECCB): Recent evolutionary studies of cancer cells have shown that malignancy involves more than just a remodeling process within multicellularity [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Rather, it represents a reversion to a more primitive, unicellular state of organization. The unicellular system observed in cancer today originated over 1000 million years ago (Mya) during the transition to multicellularity, though its fundamental structure is much older—dating back to the era of the common ancestor of amoebozoans, metazoans and fungi (AMF), likely around 2.3 billion years ago. This ancestral cell system, conserved in the genome of metazoans, mammals, humans, and even parasitic amoebae, has persisted due to its remarkable adaptability and resilience.

The deep evolutionary history of the cancer cell system- both before and after the transition to multicellularity, particularly during periods of reduced oxygen availability – helps explain not only the cancer stemgermline cell’s affinity for hypoxic niches, but also its capacity to repair genomic damage caused by excess oxygen and germline hyperoxia.

Both cancer cells and protist parasitizing human and animal hosts take advantage of the host's oxygen gradient, which provides the necessary stimuli to sustain parasitic life cycles and enables survival and progression under challenging environmental conditions. But before we start, a few introductory words about the special characteristics of unicellular cell systems as observed in the cancer and protists.

1.1. Cell Lines, Phenotypes and Function

According to previous cell biological studies [

1,

2,

3,

4], cancer has a primitive cell system that is deeply homologous to the common ancestors of amoebozoans, metazoans and fungi (AMF), and also shows strong parallels to protists such as

Entamoeba. AMF-like cell systems are dual: they consist of an oxygen-sensitive

stemgermline that could differentiate stem cells and an oxygen-resistant

somatic cell line that could not [

1,

2,

3]

. The stemgermline is the driving force behind cancer development.

The unicellular cell system that characterizes cancer, first evolved in the common AMF ancestor during periods of hypoxia. Its Ur-germline served as the blueprint for all modern stemgermlines and stem cells, which inherit the ancestral sensitivity to oxygen and are genomically damaged by oxygen contents above 6.0 % which was uncommon at the time. Oxygen levels ≥6.0% are hyperoxic for protists and cancer germlines

When exposed to hyperoxia, stemgermlines lose their functional integrity and their capacity to generate committed stem cells. This is due to a shift from productive asymmetric cell division (ACD) to dysfunctional symmetric cell

The

ACD phenotype represents the fully functional state of the stemgermline characterized by its ability to produce both self-renewing cells and committed cancer stem cells (sister cells) from a single mother cell. Recently, the ECCB has demonstrated that committed CSCs are not inherently proliferative; they can accumulate only through cyst-like polyploidization-depolyploidization cycles, which enable the accumulation of stemgermline progenitor cells [

3]

.

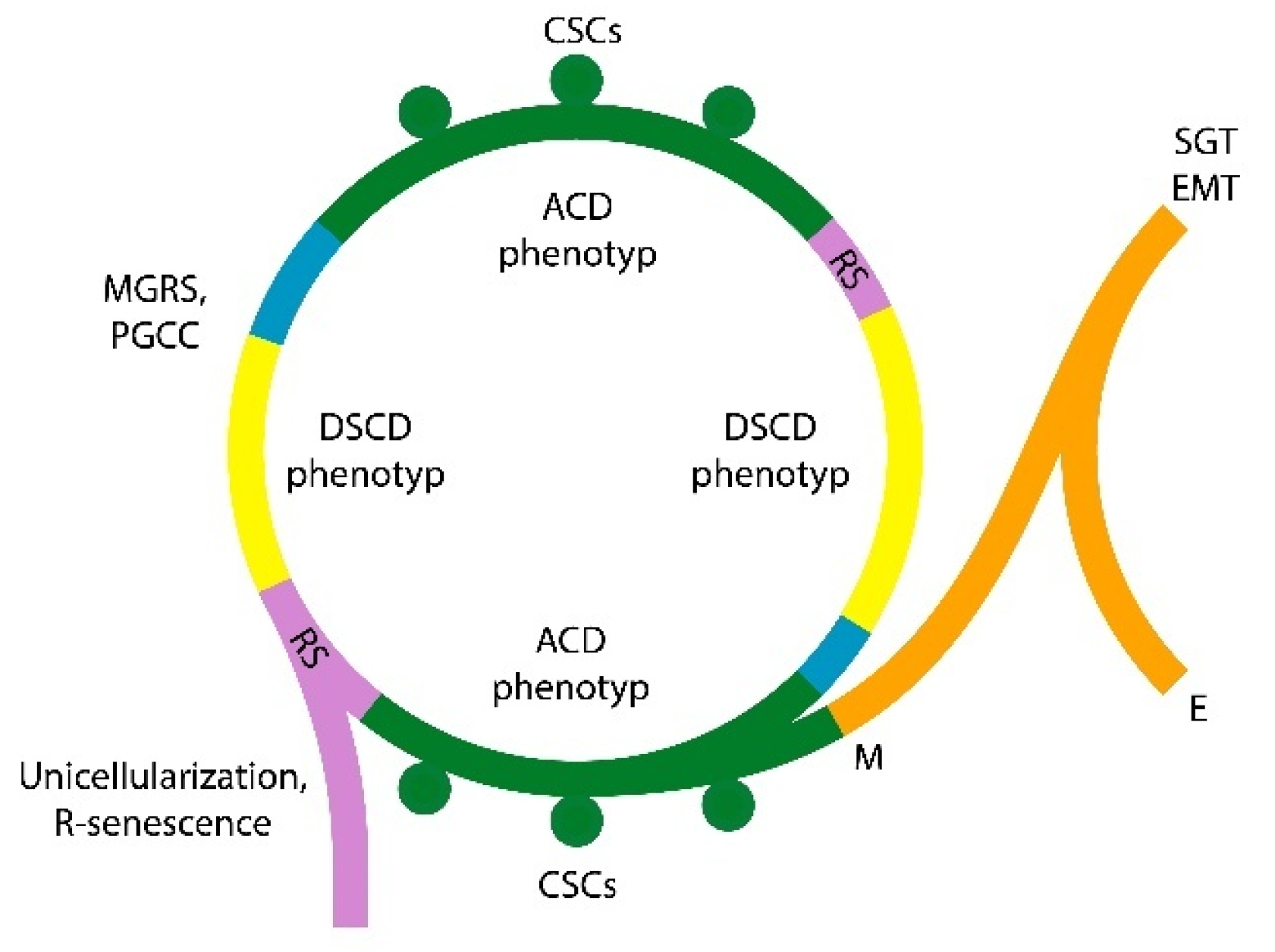

In contrast, the dysfunctional DSCD phenotype results in the production of identical daughter cells that lack stemness potential and are unable to generate CSCs. This dichotomy, with repeated switching between functional and dysfunctional germline states (ACD-DSCD cycles; stemness cycles) is fundamental for understanding the mysteries of cancer.

1.2. Stemgermline’s Vulnerability to Stress and Genomic Damage

In both cancer and parasitic protist cells, hypoxia is essential for stemgermline functionality, while hyperoxia (≥6.0 O2) acts as a stressor that causes irreparable DNA damage, genome dysfunction, and CSC depletion. Hyperoxic stress and prolonged hyperoxia lead to an ACD-DSCD switch in stemgermline cells, but not to apoptosis.

Severe hyperoxia leads to mitotic arrest (senescence) and genomic disorders in cancer stemgermlines as well as in amoebae, which can only be corrected by hyperpolyploidization/depolyploidization cycles.

This is very obvious with the amoebae. Intestinal samples of

Entamoeba transferred from the highly hypoxic host gut to hyperoxic culture media, undergoes a longer-lasting adaptive state of mitotic arrest followed by senescence exit and highly hyperploid DSCD proliferation [

6,

7]

. The same state of mitotic arrest has been observed when stemgermline cells of

Entamoeba enter well-oxygenated host tissue.

On the other hand, the abnormal DSCD proliferation is incapable of repairing hyperoxic damage (e.g. Entamoeba). Genome repair and reconstruction are impaired under hyperoxic culture conditions; instead, they require a hypoxic environment that facilitates the fusion of dysfunctional DSCD cells, enabling the reactivation of regenerative genomic processes.

In the course of metazoan evolution, hyperoxic dangers were gradually avoided. Oxygen-sensitive stemgermlines were no longer exposed to external hyperoxia. They sought out more hypoxic niches within the multicellular formation and avoided direct contact with the hyperoxic external sources. However, when they left the niches and were exposed to the oxygen levels of the bloodstream (stemgermline hyperoxia), they suffered irreparable genomic damage similar to their historical ancestors. In multicellular organisms, repair of the dysfunctional stemgermline genome is rendered impossible by the activation of apoptosis and other programmed cell death (PCD) mechanisms that evolved with multicellularity.

1.3. Genomic Repair Occurs Through Homotypic Cell Fusion and Hyperpolyploidization

Genome repair by hyperpoliploidization is unknown in the cell biology of multicellular organisms, but are known in protists and cancer

In both cell systems, DSCD cells and their progeny can undergo homotypic fusion to form multinucleated giant cell repair syncytia and polyploid giant cancer cells (MGRS and PGCCs). The MGRS/PGCC pathway is a unicellular repair mechanism inherited from the common AMF ancestor and has two distinct phases: first, a cyst-like genome amplification by polyploidization that produces defective daughter nuclei and second, a phase of daughter nuclei fusion and formation of giant nuclei capable for reconstructing the stemgermline genome. Both stages are evolutionary relics from the common AMF ancestor [

1,

2,

3,

4]

.

Unlike stressed multicellular stemgermlines that use of apoptotic programs, the unicellular cell system of cancer and protists adapts and uses ancestral genome repair capabilities to replace dysfunctional stemness-free DSCD phenotypes with functional, stemness- positive ACD sublines and clones. Hyperpolyploid MGRS/PGCC genome repair mechanisms restore stemgermline genomic architecture and function and play a pivotal role throughout tumor progression and metastasis.

1.4. Unicellularization - A Freak of Nature or an Evolutionary Inevitability?

The unicellular MGRS genome repair pathway is mediated by an ancient gene regulatory network (aGRN) derived from the archaic genome compartment of metazoans. This aGRN controls the transition from multicellularity to unicellularity (MUT) and cancer.

Historically, attempts to return to unicellularity began during the transition to multicellularity, as (i) increased free oxygen periods suppressed unicellular MGRS repair genes and (ii) early instable multicellular genomes accumulated irreparable genomic defects. To survive, early genomically unstable metazoan cells had to revert to a more unicellular genome architecture - one that could sustain life and allow evolution into more robust multicellular variants. [

4]

. The guiding principle of this era was: leave nothing untried in order to survive. And once back in the pre-metazoan stage, a new attempt at multicellularization can be tried again.

In modern multicellular organisms, where oxygen gradients are far broader than what archaic stemgermlines could tolerate, modern stem/ germline cells depend on hypoxic niches to function properly and maintain their stemness. Dysfunctional hyperoxically damaged cells relocates to a more favorable niche or benefits from changes in the local niche microenvironment, leading to the activation of ancient senescence-exit phases and senescence-exit genes.

Such escapers proliferate in a dysfunctional DSCD mode. Their progeny possesses the ability to undergo homotypic cell fusion, forming MGRS syncytia, which initiate genome repair through hyperpolyploidization. MGRS progeny give rise to progenitor cells for a new, functional stemgermline—the nascent (primary) cancer stemgermline - and its ACD-phenotype, gives rise to primary pCSCs.

Hyperoxic stimuli of different ranges also occur in tumors and damage the various stemgermlines there. However, as the cancer cell system constantly requires new committed CSCs, there are constant cycles of stemness recovery. They transition from DSCD to ACD phenotypes via homo- or heterotypic MGRS repair processes. These stemness repair cycles have a positive effect on cancer progression and genome evolution and increase resistance to host defences.

|

In summary, unicellularization is a process of genomic repair and cell fate changing, which occurs by genome reduction and inversion to a unicellular genomic state. Both pre-cancerous and intratumoral therapy-induced phases of senescence (TIS) require prolonged periods of restorative senescence, while DNA damage response and genomic repair can occur in untreated tumors and hypoxic cultures, bypassing prolonged senescence. |

2. Senescence, Apotosis and Cancer—An Overview

2.1. Senescence Duality – Current Knowledge

Apoptosis has evolved as a prominent cell death program in metazoans. Unlike protists and unicellular cancer cells, mammalian cells limit their replicative capacity through mechanisms like the "Hayflick limit," leading to cell cycle arrest and senescence when this limit is reached. Severe or prolonged stress causes metazoan cells to die via necrosis or PCD programs (apoptosis or autophagy).

As recently stated by Schmitt et al. [

8]

, senescence is a stable state of inducible mitotic arrest that follows a multi-stage senescence program. It plays context-dependent roles—both beneficial and detrimental—in life development, tissue homeostasis, and cancer. Various senescence programs are associated with enhanced stemness, mediated through both cell-autonomous and non -autonomous mechanisms, thereby contributing to the regeneration of stem cell pools.

According to these researchers, senescence acts as a tumor-suppressive mechanism by arresting the proliferation of pre-neoplastic cells. However, cells that re-enter the cell cycle after senescence are often mutagenized and display aberrant proliferation. Post-senescence proliferation is attributed to altered, reprogrammed cell states.

Accordingly, distinct intrinsic programs can lead to either anti-tumor or tumor-promoting phenotypes. The authors identify unresolved DNA damage responses (DDR), occurring either before or after senescence exit, as a central hallmark of the senescent state and emphasize the role of cellular senescence as a natural barrier to tumorigenesis.

These antagonistic senescence states are referred to by most senescence researchers as

pro-apoptotic senescence (somatic senescence)

, which suppresses tumors, and

pro-carcinogenic senescence (germline senescence

), which promotes tumor progression through functional germline activities [

9,

10,

11]

| Note. The above findings are largely consistent with results from evolutionary cancer cell biology (ECCB). At the time, however, the authors could not anticipate that pro-carcinogenic senescence represents a fundamentally distinct cell state—one that, rather than activating apoptotic programmed cell death (PCD) pathways, overrides the constraints of multicellularity and initiates survival-oriented MUT programs. These programs restore a unicellularized genome capable of enhanced DNA damage response. It was also not yet foreseeable that this process could give rise to new functional carcinogenic or tumorigenic stemgermlines, thereby generating primary and or secondary cancer stem cells (pCSCs, sCSCs). |

Furthermore, Debacq-Chainiaux et al. [

12] highlighted the critical role of oxidative stress in inducing pro-carcinogenic senescence. Oxidative damage triggers a cascade of events, including prolonged senescence, “genomic instability“, and transformation into aggressive cancer phenotype [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. The ECCB disagrees with the concept of genomic instability as it relates to stemgermlines [

1,

2,

3,

4]. This controversy is discussed in detail in the following chapters

Molecular biological studies have confirmed the concept of a single dual state of senescence, which exerts both pro-apoptotic and pro-carcinogenic effects. The BCL-2 protein family has been identified as the key regulator of this antagonistic duality. This family comprises both pro-apoptotic and pro-survival regulators, which governs the balance between cellular life and death, thereby maintaining organismal homeostasis in multicellular organisms and humans in response to developmental cues or cellular stress [

13]

Krampe and Al-Rubei [

14] observed that the first sign to cellular stress is cell cycle prolongation, with up-regulation of the transcription factor NF-ksB and Bcl-2 family proteins and death receptors signaling, which transduces apoptotic signals. Early signs of apoptosis include cell shrinkage, chromatin condensation, mitochondrial depolarization and membrane blebbing. Molecularly, apoptosis involves increased expression of pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family members and activation of caspases via death receptor ligation.

Other studies have demonstrated the existence of two distinct apoptotic pathways: the extrinsic or “death receptor” pathway, initiated by external stimuli, and the intrinsic (mitochondrial) pathway, activated by intracellular stress signals or damage [

15,

16]

. Additional evidence indicates that programmed cell death (PCD) can also occur in cell culture systems [

17]. Under nutrient deprivation, cultured cells exhibit characteristics of both apoptosis and autophagy; however, supplementation with nutrients can often prevent the onset of cell death.

Whether programmed apoptosis represents a purely metazoan novelty absent in unicellular organisms, or if incipient forms exist in protists remains controversial. Apoptosis also raises questions in cancer, such as whether certain cells can escape apoptosis and resume proliferation. These debates have gained attention in recent years.

2.2. Do Apoptosis-like Programs Also Exist in Protists and Parasitic Life?

Unicellular stemgermline cells—such as those of Entamoeba and other protists—as well as unicellularized cancer stemgermline cells, do not engage in true programmed cell death processes. In unicellular cell systems, there is no intrinsic PCD program that halts mitotic cell cycles, as long as environmental conditions remain favorable.

In 2012, Proto et al. [

18] reviewed evidence of regulated cell death pathways in selected parasitic protozoa, concluding that "that cell death in these organisms can be classified into two major types: necrosis and random death“. At the time, molecular mechanisms for regulated cell death could not be conclusively identified.

More recently, experimental studies have described a kind of programmed cell death in protists, including yeast [

19] and protozoa [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]

. Koutsogiannis et al. in 2019 [

26] explored why parasites like

Acanthamoeba express proteins facilitating self-destruction. Using the aminoglycoside G418 to induce PCD, the researchers observed shape changes in

Acanthamoeba, with apoptotic body-like cell fragments appearing after six hours.

Rounding, cell shrinkage, intracellular ion fluctuations, mitochondrial dysfunction, nuclear and chromatin condensation, and finally disintegration with the release of apoptotic body-like particles have already been observed in

Acanthamoeba [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32]

. In contrast, true PCD stages with chromatin restructuring and nuclear vesiculation as observed in

Entamoeba, have not been observed

. Is

Entamoeba closer related to cancer cells than

Acanthamoeba? Most likely

In cultures,

Entamoeba undergoes a proliferation phase lasting approximately 72 hours, followed by a stationary phase [

6,

7,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37]

. Subcultures derived from senescent cells older than seven days exhibit slower growth, with some cells attempting to exit senescence or succumbing to early death. The researchers suspect that controlled cell death helps parasite populations by promoting their long-term survival. [

24,

25]

.

2.3. Is Apoptosis a Cancer Regulator?

In recent years, cancer cell resistance to apoptosis has been widely accepted as a fundamental paradox [

38,

39]

. Recent evidence even suggests that PCD may have a cancer-promoting effect by promoting the survival, proliferation, and growth of tumor cells. Under certain conditions, PCD may even promote tumor expansion and evolutionary adaptation.

This controversy underscores the fundamental dilemma in current cancer research: the failure to distinguish between dysfunctional pre- apoptotic cells, PCD cells, and apoptotic or senescence escapers, which would maintain their viability initiating carcinogenesis. These cell types are fundamentally different in nature and fate, but are often confused, which has led to confusion about how cancer develops [

4]

.

A second paradox concerns the so-called "fractionated tumor apoptosis". It describes a scenario in which apoptosis selectively eliminates immature EMT fractions (EMT-E cells). These cells are more somatic in nature, possess fewer stemgermline traits, and are partially derived from somatic hybrid syncytia containing hijacked multicellularity genes (MGs) [

4] In contrast, the EMT-M fraction represents a more evolved, mesenchymal-like fractions that contains progenitor cells for new unicellular stemgermline clone; the EMT-M fraction has integrated potential MGs in its unicellular genome and are again opposing apoptosis (Figure 2).

[

1,

2,

3,

4] challenges the concept of "fractionated tumor apoptosis." EMT is not a form of partially programmed cell death but rather a soma-to-germ transition process (SGT) triggered by the depletion of cancer stem cells (CSCs) and dysfunction in stemgermline signaling pathways. The loss of CSCs activates dormant hybrid cancer cells—containing both cancer unicellular genes (UGs) and hijacked host multicellular genes (MGs). Successful EMT processes require the integration of hijacked MGs into the unicellular genome of stem/germ lineage. SGT fractions that fail to integrate MGs effectively remain more somatic (SGT/S fractions), are less competitive, and eliminated at an early stage. In contrast, SGT/M fractions, which successfully incorporate host MGs, complete the EMT process and give rise to stemness-positive clones and secondary sCSCs. The evolutionary SGT process—which also occurs in protists—represents a form of genome evolution rather than an apoptotic, programmed cell death (PCD) mechanism.

3. Restorative Senescence (RS) and Cell Fate Change

In the current cancer concept, dysfunctional multicellular stemgermline cells enter a state of apoptotic senescence AS, which inevitably leads to their elimination through cell death. In healthy, aging humans, there are no exceptions to this fundamental evolutionary rule.

However, according to the ECCB, some genomically damaged stemgermline cells - especially those that are hyperoxically damaged - resist the apoptotic pathway and seek alternative survival strategies to repair their genome. They free themselves from the constraints of multicellular life, avoid the state of apoptotic senescence (AS) that would otherwise lead to PCD, and enter a state of restorative senescence (RS) that prepares the cells for the transition to a state of unicellularity capable of genomic repair. During this process, the multicellular genome program is reset and an old unicellular genome module is activated. These unicellularized stemgermline cells pose a high risk to the host organism as they deviate from the regulatory control mechanisms of multicellularity.

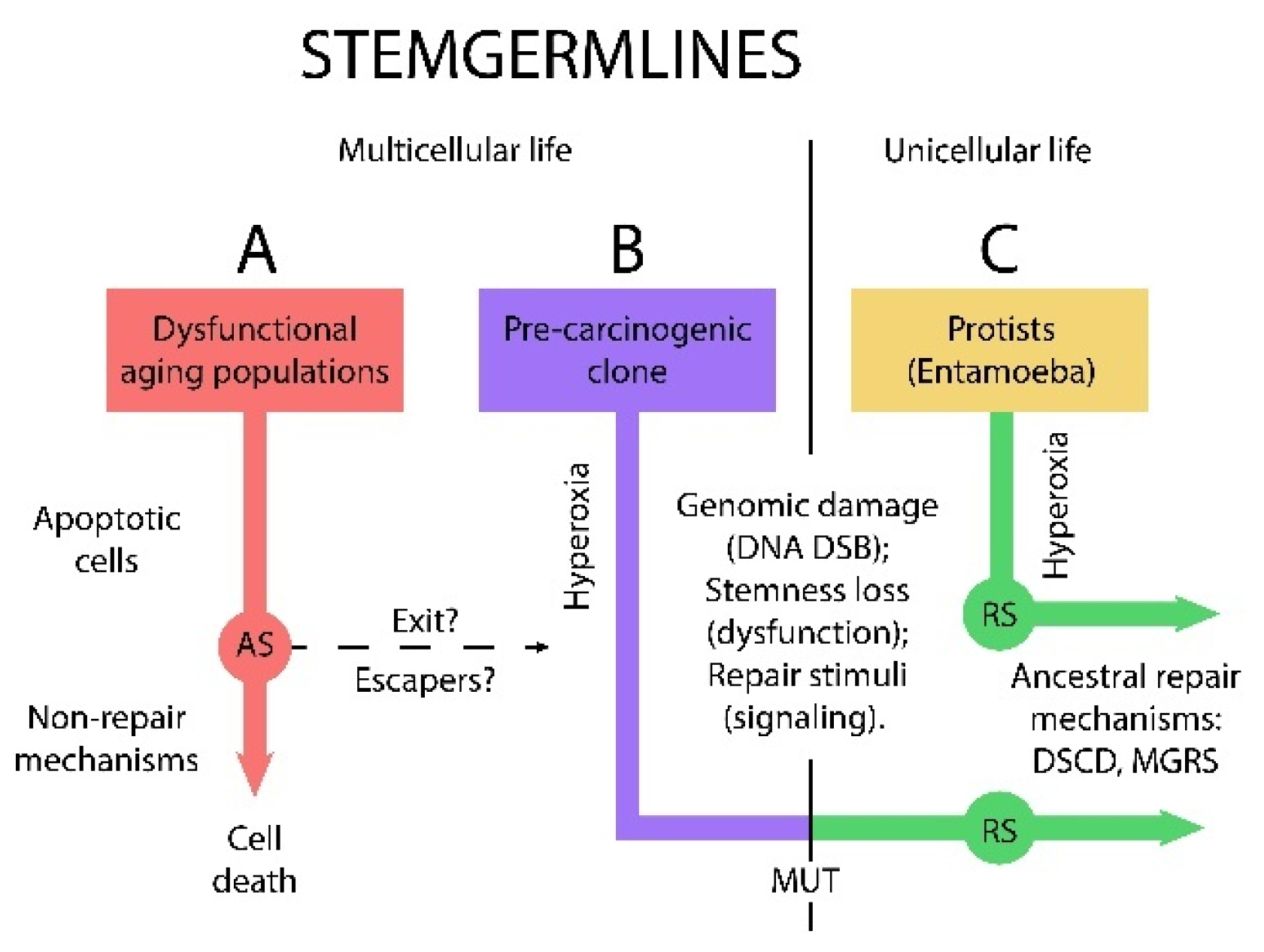

R-senescence (RS) and A-senescence (AS) represent two evolutionarily distinct cell phases (Figure 1). RS is characteristic of unicellular organisms and unicellularized cancer cells, whereas AS and apoptotic cell death are evolutionary outcomes of multicellularity, shaped by its regulatory constraints and barriers. Unicellularized stemgermline cells retain the capacity to repair damaged genomes, while multicellular cells typically respond to genomic dysfunction by triggering programmed cell death. RS reflects a unicellular strategy of genome repair, while AS is a multicellular mechanism leading to cell death. AS cells die as multicellular cells, whereas RS cells follow a unicellularized trajectory aimed at genomic restoration.

It remains uncertain whether intrinsic factors are the primary drivers of RS. Moreover, it is still unknown whether, and under what conditions, a subset of AS cells might overcome multicellular restrictions and transition into RS.

Figure 1.

Apoptotic senescence and programmed cell death vs. restorative senescence and unicellularization: Dysfunctional multicellular stemgermline cells [B] and dysfunctional DSCD protist cells [C], can regain both stemness and ACD potential through activation of ancestral MGRS genome repair pathways. In contrast, dysfunctional DNA-damaged multicellular stemgermline cells are subject to multicellularity restrictions and end apoptotically .

Figure 1.

Apoptotic senescence and programmed cell death vs. restorative senescence and unicellularization: Dysfunctional multicellular stemgermline cells [B] and dysfunctional DSCD protist cells [C], can regain both stemness and ACD potential through activation of ancestral MGRS genome repair pathways. In contrast, dysfunctional DNA-damaged multicellular stemgermline cells are subject to multicellularity restrictions and end apoptotically .

3.1. RS Initiates Specific, Unicellular DDR Circuits

Restorative senescence is a state of mitotic arrest during which damaged, non-cancerous and tumor-associated stemgermline cells - that have lost functionality - are given the opportunity to survive and restore a functional genomic architecture [

4]

. According to ECCB [

1,

2,

3,

4] unicellular stemgermline systems—such as those found in

Entamoeba - and unicellularized cancer cells adopt ancestral genome repair mechanisms. These mechanisms are thought to originate from the Ur-germline of AMF lineages. In contrast, the stemgermline cells of multicellular organisms have lost access to these ancestral repair pathways.

Genomically damaged multicellular cells can only access ancestral DDR circuits after their unicellularization through MUT processes (R-senescence). At the core of the unicellular DDR circuitry lies the DSCD–MGRS/PGCC genome repair pathway, which reconstructs the architecture of oxygen-damaged stemgermline cells during both carcinogenesis and tumorigenesis. This unicellular DDR network involves RS-exit, DSCD proliferation, homotypic cell fusion, and hyperpolyploid genome repair via the MGRS mechanisms [

3,

4] ultimately restoring the ACD phenotype of the stemgermline, its stemness and CSC potential.

Over the course of evolution, cells in multicellular organisms largely relinquished this capacity for genome reconstruction in favor of apoptotic death programs. Aging somatic and stemgermline cells in metazoans are not programmed to regenerate their dysfunctional genomes, as the aging multicellular organism does not require the production of new functional stemgermlines and new stem cells. In contrast, indefinitely proliferating unicellular systems—such as parasitic amoebae and unicellularized cancer cell systems can reactivate the ancestral genome repair program.

3.2. RS in Protists

Dysfunctional protists such as

Entamoeba exhibit transient senescence in response to hyperoxic injury both in vivo and in vitro.

In vitro, prolonged senescence is observed when intestinal amoebae are transferred directly from the hypoxic gut environment into hyperoxic, bacteria-free cultures [

6,

7,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37]. This abrupt hypoxic-to-hyperoxic shift induces DNA double-strand break (DSB), triggering an extended adaptive, long-lasting RS state. Senescent cells that survive this stress re-enter an aberrant DSCD cell cycle and resume proliferation through a defined sequence of ploidy transitions—initially hyperpolyploid, then progressively reducing ploidy to a more stable tetraploid state, and ultimately returning to diploidy.

In vivo,

Entamoeba cells that inadvertently infiltrate hyperoxic tissue experience severe DNA DSB damage, leading to a prolonged period of mitotic arrest [

6,

7]. Under favorable exit conditions, these senescent amoebae are capable of regenerating a new stemgermline, along with functional stem cells.

3.3. RS Alone Cannot Reverse Genomic Damage

Restortive senescence is a relic of a bygone era that cannot resolve the dysfunctional genome reconstruction of the stemgermline and its genomic integrity but can induce it. Even RS escapers cannot perform genomic repair despite DSCD proliferation. Genome reconstruction is only possible in the context of MGRS hyperpolyploidization with or without homotypic cell fusion.

The switch from dysfunctional, stemness negative DSCD-phenotype to fully functional, stemness positive ACD phenotypes and genomic integrity recover (

Figure 2) occurs only via MGRS hyperpolyploidization [

3].

The unusually long duration of senescence phases underscores the complexity and difficulty that genomically damaged RS cells have in preparing for unicellularization. This challenge is observed not only in the cells of multicellular organisms but also in protist parasites such as Entamoeba, whose life cycle is always dependent on their environmental conditions.

4.Cycles of Stemness Loss and Stemness Recovery; Aim and Function

Stemness loss and recovery cycles involve alternating ACD and DSCD phenotypes, accompanied by corresponding periods of cancer stem cell (CSC) generation and CSC cessation [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Each ACD lineage consists of proliferative, self-renewing stemgermline cells and their committed, non-proliferative—but genomically related—CSCs. Tumors harbor a multitude of genomically heterogeneous primary and secondary ACD lineages (pACD and sACD), with most ACD phenotypes arising through fractal EMT processes. All ACD phenotypes are sensitive to oxygen excess; under hyperoxic conditions, they lose stemness and function, transitioning into DSCD cells that proliferate trough aberrant symmetric cell cycles. The alternation between DSCD and ACD cell types (DSCD-ACD cycles), mediated by the MGRS/PGCC genome repair pathway, reconstructs the genomic architecture of dysfunctional stemgermlines. This process represents a cycle of functional recovery, stemness restoration and CSCs replacement. (Figure 2).

4.1. Genomic Stability, Instability and the “Status Quo Ante“

DDR circuits restore stemgermline fitness not only during carcinogenesis but also in established tumors and even in protists. As demonstrated by the ECCB studies [

1,

2,

3,

4], DSCD lineages retain the capacity to initiate genome reconstruction and give rise to productive ACD phenotypes, along with committed CSCs

This ability of the stemgermline genome to revert to the

status quo ante –(regaining previous genomic architecture, functionality, and stability) - was observed in various cancer stages. Since cancer stemgermline cells can continuously transition from a dysfunctional to a fully functional state, it is not appropriate to characterize them by genomic instability or a loss of genomic integrity. De Blander et al. [

40] also reveals that stem/ germlines (CSCs) can escape senescence and generate genomically stable tumors.

The dualistic model of tumor initiation proposed by this researcher in 2021 [

40] describes two tumor-initiating pathways. The first involves primary CSCs, which arise from the nascent (primary) cancer stemgermline. The second involves more differentiated EMT-E fractions that drive genome expansion and contribute to intra-tumoral heterogeneity. The ECCB's investigations agree with this statement [

4] (

Figure 2).

Every stemgermline-derived subline or clone—regardless of the degree of genomic expansion—either maintains genomic stability or, if lost, is capable of restoring it. Secondary tumors and metastases are more heterogenous due to genome expansion (evolution), but they are not genomically instable. Each dysfunctional stemgermline, subline or clone can activate genome repairing mechanisms and return to its functional status quo ante.

Both tumor-initiating pathways proposed by De Blander et al. [

40] have ancestral origin, deeply rooted in the evolutionary mechanisms involving homotypic and heterotypic cell fusion and genomic expansion through the hijacking of extra-systemic genes (e.g. multicellularity genes) [

4].

4.2. The Distinct Roles of Homotypic and Heterotypic Cell Fusion in Genome Stability and Expansion

Soma-to-germline transition (SGT) is an ancient mechanisms of stem cell replacement in unicellular cell populations that have lost the ability to continuously generate new stem cells due to irreparable DNA damage, stemgermline dysfunction, and the loss of stemness potential. SGT can give rise to new primary pCSCs when it originates from homologous somatic cancer cells, and to secondary sCSCs when it arises from hybrid cancer cells formed through the fusion of cancer cells with non-cancerous host cells (heterotypic cell fusion).

In cancer, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) recapitulates ancestral soma-to-germ transitions and contribute to cancer genome expansion and intra-tumoral stemgermline heterogeneity. Distinct fractal EMT fractions follow different trajectories: immature, epithelial EMT-E fractions tend toward apoptosis, whereas mesenchymal EMT-M pools give rise to secondary progenitor cells via ancestral SGT mechanisms and replenish the stem cell pool (Figure 2). This model highlights the dual evolutionary trajectory of cancer genomes—from the genomic homogeneity of primary tumors to the heterogeneity seen in secondary tumors and metastases.

The fate of different EMT fractions during and after therapeutic treatment remains poorly understood. More differentiated, hybrid EMT-E fractions are generally treatment-sensitive and tend to undergo apoptosis or become aneuploid. In contrast, EMT-M fractions are more likely to enter a state of restorative senescence [

40] and continue EMT-driven evolution, leading to the formation of genomically stable secondary stemgermline cells and sCSCs.

Fractal SGT processes, , such as those seen in humans and metazoans, have not been observed in protists. In

Entamoeba, the soma-to-germ transition occurs rapidly and without interruption, typically within 24 hours, when somatic cells grown in hyperoxic cultures are transferred to a hypoxic, nutrient-deprived conditions [

34,

35]. This transition triggers cycles of polyploidization and depolyploidization, resulting in the accumulation of progenitor cells that generate new, functional ACD stemgermline.

In summary, unicellular cell systems employ homotypic cell fusion for genome repair, whether involving primary or secondary stemgermline cells, sublines, or clones; Homotypic cell fusion supports homologous stem cell replacement, while heterotypic cell fusion serves to expand the stemgermline genome. In cancer, heterotypic cell fusion often works in concert with fractal EMT to generate increasingly potent stem cell populations.

Previously, heterotypic cell fusion was believed to destabilize cancer cell genomes, and EMT products were considered highly unstable. However, evolutionary cancer cell biology [

1,

2,

3,

4] demonstrates that all primary and secondary stemgermline lineages, sublines, and clones can regain genomic stability and integrity through ongoing dysfunctional genome reconstruction mediated by the MGRS repair pathway.

5. Previous Statements on Mitotic Arrest and Resumed Proliferation

5.1. Causes of Mitotic Arrest, Factors and Stressors

Cellular senescence is a stress-induced state of proliferation arrest [

8] that occurs in non-cancerous, pre-carcinogenic and cancerous cells following severe DNA DSB damage caused by intrinsic stressors (e.g.aging) or deleterious extrinsic agents (e.g. cancer). There are multiple senescence factors, which can be stimulated by various triggers. Growth-promoting effects have been observed in cultures with cells subjected to oxidative stress [

10,

41].

According to Gorgoulis et al. in 2019 [

42]

, cellular senescence can be defined as a prolonged and essentially irreversible state of cell cycle arrest, triggered by various stressors, physiological signals, macromolecular damage, or metabolic alterations. It also occurs in response to genotoxic substances,

harmful oxygen ranges, and oncogene activation. Advances in experimental tools over the last decade have substantially deepened our understanding of both the causes and the functional consequences of cellular senescence.

However, recent findings suggest that irreversible cell cycle arrest is not always an inevitable outcome of senescence. Under certain conditions, senescent cells can re-enter the cell cycle while retaining key senescent characteristics. These observations align senescence research more closely with ancient evolutionary mechanisms—particularly restorative senescence—as observed in both protists and cancer evolution.

5.2. Senescence Reversibility: Stemness Recovery and Enhanced Tumorigenic Potential

Saleh et al. [

43] hypothesized 2019 that senescence is, “in principle,

a reversible condition, which becomes evident when essential

senescence maintenance genes are no longer expressed". Sabisz et al. [

44] observed that the post senescence growth is associated with the emergence of CSCs and - a decade later - Milanovic et al. [

45] further substantiated this opinion by showing that cells released from treatment-induced senescence re-entered the cell cycle with significantly enhanced clonogenic growth potential compared to control cell populations that after chemotherapy never entered senescence. The formerly senescent cells exhibited stemness recovery [

46]

, and significantly increased tumorigenic potential [

47].

5.3. Bright and Dark Senescence

Nevertheless, previous cancer research has not been able to distinguish between A- and R- senescence. Most researchers still believe that there is a unique state of dual senescence that can have both pro- and anti-carcinogenic effects under the influence of certain regulatory factors [

9,

10,

11,

12,

48]

.

The only exception is the more recent assumption that two different states of senescence could occur, namely a “bright” and a “dark” senescence, which could influence cancer development in different ways. This distinction would better fit the A and R senescence demonstrated by the present work.

According to Ou et al. [

9]

, cellular senescence in cancer strongly depends on the cell type (

germline or somatic) and the context (functional or dysfunctional). In line with this view, senescence can prevent the expansion of premalignant cells by inducing permanent cell cycle arrest (

bright senescence). On the other hand, it can reshape the tumor microenvironment [

49,

50], promoting stemness recovery and tumor progression (

dark senescence) [

47,

51]

.

Recently, Huang et al. [

52] investigated the control mechanisms that determine the balance between pro-tumorigenic dark senescence and anti-tumorigenic bright senescence and proposed that different degrees of oncogene activation lead to different trajectories. They either suppress tumor progression [

53] or drive tumorigenesis.

Most researchers describe bright and dark senescence as an interplay between senescence, repair, and reprogramming, highlighting the paradoxical role of senescence in tumor cell biology—as both a transient tumor suppressor and a potential enhancer of tumorigenesis [

54]. These interpretations align with the core views of Evolutionary Cancer Cell Biology ECCB [

1,

2,

3,

4], which proposes that repeated restorative DNA damage response (DDR) cycles enhance cellular growth potential, aggressiveness, and pathogenicity. However, ECCB offers a more detailed framework, emphasizing the evolutionary origins and mechanistic depth of these processes [

4].

5.4. Senescence and Tumors

Currently, cellular senescence is regarded as a barrier to tumor development but if senescence-mediated suppression mechanisms are "

compromised," cells can escape from senescence and acquire more aggressive, malignant phenotypes. However, the mechanisms that control senescence exit, the factors that induce cells to overcome growth arrest, and the resulting post-senescent phenotypes have not been fully elucidated by current cancer research [

42]

.

Nevertheless, as early as 2001, it was reported that cellular senescence occurs not only during early stages of tumorigenesis but also in advanced tumors in response to DNA damage caused by therapeutic interventions [

41]

, and tumor senescence is a most complex phenomenon as previously thought.

In summary, significant ambiguity and confusion still surround the characterization of both pre-carcinogenic and tumorigenic senescence. However, these processes can now be more coherently explained within the framework of evolutionary cancer cell biology ECCB.

5.5. Sen-Mark+ Cells

Previous studies on senescence exit have shown that it may take several weeks for cells to escape mitotic arrest [

43,

45]. Interestingly, cells that exit senescence retain features characteristic of the senescent state. The proliferating post-senescent phenotype is considered a dissociated state, characterized by a mixture of partially

preserved and partially r

eversed traits.

As cells exit senescence, they express high levels of senescence markers (

Sen-Mark+) and robust proliferative capacity [

55]

. These findings challenged previous understanding and highlights the complex interplay between senescence markers and proliferative behavior. It suggests that

Sen-Mark+ cells, may represent a distinct cell state with latent stem-like or regenerative potential, contributing to tumor progression and aggressiveness.

O'Sullivan et al. [

5][] observed that successive rounds of error-prone replication in precancerous cells result in accumulated DNA damage and heightened genomic instability. Such tumors can form post-senescent proliferative cells with defects in key senescence effector molecules. They express high levels of senescence markers (

Sen-Mark+) while remaining proliferative. This paradox has been largely overlooked.

In the ECCB perspective [

1,

2,

3,

4]

, senescence markers are DSCD markers activated during the state of restorative RS repair.

Remember: all proliferating senescence are DSCD cells, demonstrating that senescence markers are indicative of the DSCD phenotype. Dysfunctional, defective DSCD proliferation occurs not only in unicellular organisms but also in tumors. O'Sullivan et al [

55] referred to the ancestral state of restorative senescence as cancer-related OIS (oncogene-induced senescence). However, this RS/OIS state is merely a consequence of the unicellularization of pre-cancerous, DNA-damaged stemgermline cells. DSCD/OIS cells are not induced by oncogenes, but rather represent a downstream consequence of genomic alterations already experienced by the common AMF ancestor millions of years ago as a result of stress, DNA damage, dysfunction, and loss of stemness.

According to these researchers, “subsequent, successive rounds of error-prone replication in pre-cancerous cells can lead to the accumulation of more DNA damage and increased

genomic instability, thereby allowing further

pro-tumorigenic mutations to take place”. From the perspective of the ECCB [

1,

2,

3,

4]

, DSCD cells and their dysfunctional progeny are not genomically unstabile cells, but only an intermediary step in stemgermline repair and genome reconstruction via ancestral MGRS/PGCC mechanisms that generate precursors for functional ACD stemgermlines and ultimately CSCs. The MGRS/PGCC pathway is part of the DDR circuitry and continuous monitoring to ensure genome stability and genomic integrity.

5.6. Inducers, Mediators, Effectors, and Markers

According to the current view, senescence is a cell state often described as a metastable homeostatic condition triggered by various stressors and effectors. These effectors typically cause irreparable DNA damage leading to the upregulation of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors (CDKi) such as p16-INK4a and p21, which are considered key inhibitors and senescence markers. Such inhibitors initiate and maintain stable cell cycle arrest [

55]. Additionally, senescence-associated SASP factors, such as IL-6 and IL-8, have been implicated in reinforcing this process.

Schmitt et al

. [

8], considered that p21 and p16 (aka G1-checkpoint CDK inhibitors 1A and 2A) can disrupt the formation of CDK-cyclin complexes necessary for cell cycle progression. Hernandez [

56] found that p16 acts specifically at the G1/S transition, while p21 inhibits multiple cyclin-CDK complexes, including CDK4/6-cyclin D

, CDK1-cyclin B1

, and CDK1/2-cyclin complexes.

According to the molecular view, activation of the DDR signaling, which simultaneously induces senescence and latent stem-like reprogramming, can paradoxically compromise tumor suppression by promoting cancer cell survival and proliferation [

45,

57]

.

In contrast, the ECCB has demonstrated that both senescence and apoptosis are direct consequences of stemgermline dysfunction and mitotic arrest. While genome dysfunction induces apoptosis in multicellular systems, it leads to restorative RS senescence and genome reconstruction in unicellular systems of cancer and protists. (

Figure 1)

Proliferating senescence escapers (DSCD cells) lacking stemness cannot regenerate a functional germline genome on their own. Reprogramming to the

status quo ante—the restoration of germline genome integrity along with stemness and ACD (asymmetric cell division) potential—occurs exclusively during restorative MGRS/PGCC processes. Specifically, during the second polyploidization phase [

3], defective nuclei from the first repair phase fuse to form giant hyperpolyploid nuclei. These subsequently undergo depolyploidization, giving rise to progenitor cells capable of forming new functional stemgermline clones and sublines

.

5.7. Therapy-INDUCED SENESCENCE (TIS)

As noted by Schmitt et al

. [

8]

, chemotherapeutic drugs and radiation significantly increase the presence of senescence marker-positive cells [

48,

58]. DNA damage is the most common driver of senescence in both non-malignant somatic cells and malignant stemgermline cells, leading to an accumulation of senescent cells in various tissues [

59,

60]

. It induces senescence not only in tumors but, to a lesser extent and more transiently, in non-malignant tissues, with long-term implications for tissue recovery after the elimination of malignant cell populations.

A large number of active substances act as senescence inducers in preclinical models. These include alkylating agents such as cisplatin, cyclophosphamide, and temozolomide [

61,

62,

63,

64], topoisomerase inhibitors such as doxorubicin, etoposide and γ-irradiation [

6][]

, and, to a lesser extent vinca alkaloids such as vincristine, have also been identified as senescence inducers in preclinical models. All these agents are known to upregulate the senescence marker p16- INK4a. According to Schmitt et al. 2022 [

8] “senescence is an integral effector mechanism induced by most anticancer treatments, especially those that result in DNA damage“.

Therapy-induced senescence (TIS) can result in favorable outcomes if it halts cancer cell proliferation. Additionally, immune surveillance may contribute in eliminating senescent cells through apoptosis [

66]

. For example, radiotherapy, a crucial cancer treatment, effectively induces senescence in several p53-proficient cancer cell types. The cell fate decision between senescence and apoptosis in response to radiation appears to depend, in part, on the presence of the PTEN tumor suppressors. For instance, radiation induces senescence in PTEN-deficient human glioma cells but induces apoptosis in PTEN-proficient cells.

Schmitt et al. [

8] showed that the TIS response in tumors is highly heterogeneous. This variability is less influenced by the tumor's type or origin and more by the characteristics and history of individual cells. However, the authors did not provide a detailed explanation for this phenomenon.

Earlier studies by Sabish and Skladanowski from 2009 [

44]

, and Was et al. from 2017 [

67] identified two distinct cancer cell subpopulations in the context of TIS: (i) a mini-fraction, comprising ≤1.5% of cells, capable of re-entering the cell cycle after prolonged senescence, and (ii) the remaining ≥98% of cells, which remain in a pro-apoptotic senescence state. Despite these valuable observations, the dual structure of cancer cell populations was not fully understood.

In contrast, ECCB studies [

1,

2,

3,

4] have demonstrated that the 1.5% are dysfunctional cancer stem/germ cells (DSCDs) capable of MGRS/PGCC repair. In contrast, the remaining 98% consist of therapy-sensitive somatic cells that could be therapeutically removed. The long-lasting restorative stem/germ cell senescence leads to a delay in tumor growth, if not to tumor regression. This ECCB distinction provides a deeper understanding of the dynamics between germline and non-germline components in response to TIS.

In cancer treatment, therapeutic efficacy hinges on achieving a balance where the rate of tumor cell death exceeds the rate of new cell formation. Understanding the apoptosis paradox is crucial for developing strategies that effectively target cancer cells without inadvertently supporting their survival or adaptive growth.

6. Valid and Less Valid Statements of the Past on Senescent Exit and Tumorigenesis

6.1. “Stem Cells Do Not Senesces“

In his recent review, De Blander et al. [

40] analyzed an impressive number of articles attempting to shed light on the duality of senescence onset and senescence evasion. In the absence of a suitable single-cell cancer model and sufficient evolutionary knowledge, these statements are not always coherently explained

The researchers analyzed the differences between cells that do not senesces and cells that undergo prolonged senescence. Their results suggest that the likelihood of avoiding senescence depends on the degree of differentiation of the cells. "Young adult stem cells do not senesce; they are more committed to differentiation" [

40,

68,

69,

70]

.

This finding is confirmed by the ECCB studies [

1,

2,

3,

4]

. As recently stated [

3]

, the ACD germline phenotype gives rise to two daughter cells: a self-renewing stemgermline cell and committed CSCs, the latter lacking proliferative capacity. Only the self-renewing sister cells can undergo cell cycles, whereas committed CSCs can only accumulate through hyper- polyploidization/ depolyploidization cycles, generating progenitor cells for stemgermline clones and sublines. The fact that committed CSCs do not senesce is a consequence of their commitment. They are no proliferative and have not risk of DNA DSB damage

6.2. “Senescence Escapers Require the Acquisition of Polyploidy and Genomic Instability”

Polyploidy

Cancer research describes several forms of senescence: (i) replicative senescence or telomere-dependent senescence (TDS), characterized in fibroblasts and caused by telomere shortening; (ii) oncogene-induced senescence (OIS), triggered by the activation of oncogenes such as RAS; and (iii) therapy-induced senescence (TIS), which follows cancer treatments like chemotherapy and radiotherapy [

71,

72,

73]. All of them are activated via the p53/p21-WAF1 tumor suppressor pathway and share a reliance on genotoxic stress as the initiating factor. Accordingly, TDS, OIS, and TIS are induced by DNA damage and are associated with endoreplication, polyploidy (tetraploidy), and extensive epigenetic reprogramming [

74,

75,

76,

77,

78,

79,

80]

.

Several researchers believe that tetraploid cells exhibit genomic instability and can become aneuploid, suggesting that this process plays an important role in tumorigenesis regardless of p53 status [

81,

82,

83,

84,

85,

86,

87]

Genomic Instability

From the point of view of the ECCB, senescent escapers are not genomically unstable. After repair through the MGRS/PGCC pathway, they regain full functionality and genomic stability (status quo ante).

During tumorigenesis, the unicellularized cancer stemgermline undergoes repetitive cycles of genomic dysfunction characterized by transient loss of stemness and recovery of stemness. These cycles occur continuously within tumors but do not result in persistent genomic instability. Genomic instability is a hallmark of somatic cell lines, not the germline.

In classical cancer research, genomic instability manifests itself primarily as chromosomal instability (CIN), a state of permanent mitotic dysfunction, karyotypic abnormalities and aneuploidy. CIN, which contributes to intratumoral heterogeneity, is increasingly recognized as a biomarker of poor prognosis in various cancers, and its presence, along with aneuploidy, is associated with multidrug resistance. [

88,

89]

6.3. Depolyploidization and Budding

Senescence escapers are considered capable of driving polyploid cells to depolyploidize and bud [

90]. In the past, polyploid cells were considered fully differentiated cells because they could no longer divide. Unfortunately, the term polyploid does not distinguish between low (tetra-) and high (hyper-) ploidy. The budding of germline progenitor cells originates from hyperpolyploid MGRS/PGCC and not from tetraploid cells.

6.4. “Neosis—An Atypical Cell Division”

Researchers mention, multinucleated polyploid giant cells can restore proliferative capacity by undergoing an “atypical type of cell division known as neosis“ [

85,

91,

92,

93,

94]

. Accordingly, “neosis“would produce daughter cells with reduced cell ploidy (diploidy) and prolonged mitotic life span [

92,

93] and is thus thought to be the "origin of senescence escapers" [

95,

96,

97,

98,

99]

. Unfortunately, this was a botched statement right from the start

First, the term neosis is a misnomer; It was introduced 2004-2006 by Sundarm et al. as a new type of asymmetric cell division, which it is not. Neosis is the formation of multiple spores (buds) from hyperpolyploid MGRS/PGCC genome repair structures [

1,

2,

3] via reductive nuclear division and cellularization, and was descriebed even 1908 in

Entamoeba by Craig [

100]

.

Second, senescence escapers originate from mitotically arrested tetraploid cells that cease ACD cycling due to irreparable DNA DSB damage. These senescent cells enter DDR circuits and transition into DSCD lineages, continuing proliferation in a dysfunctional cell state until they undergo fusion to form MGRS/PGCC repair structures

7. Conclusions and Perspectives

The major novelty of this study is the discovery that pre-carcinogenesis is initiated by a phase of restorative senescence and cell fate changing. To survive, cells originating from dysfunctional stemgermlines – having lost their function, stemness and capacity for asymmetric division— circumvent multicellular constraints, evade apoptotic programs, and initiate a process of unicellularization. This new theory of multicellular genome restriction and unicellularization significantly weakens current theories of cancer biogenesis by genetic and genomic alteration that cannot explain stemgermline evolution or its genomic repair and expansion in cancer.

The present work extends the evolutionary perspective on cancer cell biology and further develops the framework of Evolutionary Cancer Cell Biology (ECCB), which was founded by the present author over the past decade. It analyzes current knowledge on non-genetic mechanisms—specifically the dual role of senescence as both pro-apoptotic and pro-carcinogenic—within the contexts of tumor evolution, through an evolutionary lens. In contrast to current knowledge, this study distinguishes between: (i) a state of apoptotic senescence leading to the death of multicellular cells, and (ii) a state of restorative senescence (RS) that initiates a process of Multicellular-to-Unicellular Transition (MUT), giving rise to a unicellular autonomous cancer cell system.

The present analysis demonstrates that dysfunctional stemgermline cells—severely damaged by hyperoxic stress—retain the capacity to undergo MUT, an ancestral process involving a genomic inversion to a deeply conserved compartment within the metazoan genome [

4]

. Following a prolonged period of mitotic arrest, these unicellularized senescence-escaper cells can repair their dysfunctional genomes and restore functional genomic architecture (Status Quo Ante) via unicellular-specific repair mechanisms. These include aberrant DSCD proliferation, homotypic cell fusion, and the hyperpolyploid MGRS/PGCC genome repair pathway—mechanisms absent from multicellular biology. The resulting multitude of MGRS-derived daughter cells (spores or buds) serves as progenitors of the nascent cancer stemgermline. In carcinogenesis, MGRS reintroduce the ACD phenotype characteristic of functional stemgermlines that are capable of generating primary pCSCs.

Like all stemgermlines derived from the ancestral Ur-germline, the nascent cancer stemgermline is highly sensitive to excess oxygen. Upon contact with the hyperoxic environments of the bloodstream and surrounding tissue, the unicellular stemgermline experiences severe DNA damage that impairs the functionality of the stemgermline genome and erodes its stemness, reverting these cells to a dysfunctional, stemness-free DSCD phenotype. However, stemness and the ACD phenotype can be re-established through the activation of DNA damage response (enlarged unicellular DDR circuits), which facilitate the reconstruction of genomic integrity and function recovery. ECCB demonstrates that there is neither chaos nor inherent genomic instability in the genomes of cancer stemgermlines, their clones, or sublines. Genomic functionality can be preserved or continuously restored through ancestral repair mechanisms

In tumors, intratumoral heterogeneity (ITH) arises primarily from fractal epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) processes rather than from genomic instability of stemgermlineages. Cell signaling triggered by dysfunctional genomes and the exhaustion of CSCs induces the formation of somatic hybrid cells through heterotypic fusion with host multicellular cells. These hybrid cells, generate secondary stemgermline clones via a soma-to-germ transition (also referred to as EMT),. The secondary clones contain both unicellular genes (UGs) and multicellular genes (MGs), thereby expanding the genomic repertoire of the cancer stemgermlineage and giving rise to multiple new phenotypes and clones capable of more invasive sCSCs and metastasis. All secondary stemgermline lineages remain sensitive to excess oxygen, and their genomes can be damaged by hyperoxic exposure. However, these lineages retain the capacity for repair through MGRS/PGCC mechanisms. Within tumors, DSCD–ACD cycles, referred to as stemness cycles, continue to evolve dynamically, sustaining tumor development and heterogeneity.

ECCB resolves many of the unanswered questions that previous cancer cell research has been unable to answer. This evolutionary perspective on carcinogenesis and tumorigenesis offers a novel and integrative foundation for cancer research and therapeutic innovation.

The founder of ECCB and present author envisions future cancer vaccines that may successfully target and inactivate the unicellularization process (MUT), DSCD proliferation, or the genomic repair and functional recovery mechanisms in senescent or Sen-Mark+/ DSCD cells—ultimately directing them toward irreversible cell death.

Abbreviations

ACD, ACD phenotype through asymmetric cell division; AMF, amoebozoans, metazoans, fungi; AS, apoptotic senescence; pCSCs, primary cancer stem cells; sCSCs, secondary cancer stem cells; DDR, DNA damage response; DSB, double strand breaks; DSCD, DSCD phenotype through defective symmetric cell division; ECCB, evolutionary cancer cell biology; EMT, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition ; MUT, multicellular-to-unicellular transition; MGRS, multinucleated genome repair syncytia; MGs, multicellular genes; PCD, programmed cell death; RS, restorative senescence; SGT, soma-to-germ transition; TIS, therapy induced senescence; UGs, unicellular genes.

References

- Niculescu, VF. Understanding cancer from an evolutionary perspective: High-risk reprogramming of genome-damaged stem cells. Acad Med. 2024, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

Niculescu VF, Niculescu ER. The enigma of cancer polyploidy as deciphered by evolutionary cancer cell biology (ECCB). Acad Med 2024, 1.

- Niculescu, VF. Reevaluating cancer stem cells and polyploid giant cancer cells from the evolutionary cancer cell biology perspective. Cancer Plus. [CrossRef]

- Niculescu, VF. Cancer Results from the Disruption of Multicellular Constraints, Genomic Inversion to Unicellularity, and Evolution by Horizontal Gene Transfer. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

Vinogradov AE, Anatskaya OV. Systemic alterations of cancer cells and their boost by polyploidization: Unicellular attractor (UCA) model. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 6196. [CrossRef]

-

Mukherjee C, Clark CG, Lohia A. Entamoeba shows reversible variation in ploidy under different growth conditions and between life cycle phases. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2008, 2, e281.

-

Mukherjee C, Majumder S, Lohia A. Inter-cellular variation in DNA content of3 Entamoeba histolytica originates from temporal and spatial uncoupling of cytokinesis from the nuclear cycle. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2009, 3, e409. [CrossRef]

-

Schmitt CA, Wang B, Demaria M. Senescence and cancer - role and therapeutic opportunities. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2022, 19, 619–636. [CrossRef]

-

Ou HL, et al. Cellular senescence in cancer: from mechanisms to detection. Mol Oncol 2021, 15, 2634–2671. [CrossRef]

-

Chien Y, Scuoppo C, Wang X, Fang X, Balgley B, et al. Control of the senescence-associated secretory phenotype by NF-κB promotes senescence and enhances chemosensitivity. Genes Dev 2011, 25, 2125–2136. [CrossRef]

-

Sebastian T, Malik R, Thomas S, Sage J, Johnson PF. C/EBPβ cooperates with RB:E2F to implement RasV12- induced cellular senescence. EMBO J 2005, 24, 3301–3312. [CrossRef]

-

Debacq-Chainiaux F, Ben Ameur R, Bauwens E, Dumortier E, Toutfaire M, Toussaint O. Stress-induced (premature) senescence. In: Rattan SIS, Hayflick L, editors. Cellular Ageing and Replicative Senescence: Healthy Ageing and Longevity. Cham: Springer; 2016. p. 243–262.

-

Singh R, Letai A, Sarosiek K. Regulation of apoptosis in health and disease: the balancing act of BCL-2 family proteins. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2019, 20, 175–193. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Krampe B, Al-Rubeai M. Cell death in mammalian cell culture: molecular mechanisms and cell line engineering strategies. Cytotechnology 2010, 62, 175–188. [CrossRef]

-

Campbell KJ, Tait SWG. Targeting BCL-2 regulated apoptosis in cancer. Open Biol 2018, 8, 180002.

- Qian S, Wei Z, Yang W, Huang J, Yang Y, Wang J. The role of BCL-2 family proteins in regulating apoptosis and cancer therapy. Front Oncol 2022, 12, 985363.

-

Zustiak M, Pollack JK, Marten MR, Betenbaugh MJ. Feast or famine: autophagy control and engineering in eukaryotic cell culture. Curr Opin Biotechnol 2008, 5, 518–526.

-

Proto WR, Coombs GH, Mottram JC. Cell death in parasitic protozoa: regulated or incidental? Nat Rev Microbiol 2012, 11.

-

Madeo F, Fröhlich E, Ligr M, Grey M, Sigrist SJ et al. Oxygen stress: a regulator of apoptosis in yeast. J Cell Biol 1999, 145, 757–767. [CrossRef]

-

Cornillon S, Foa C, Davoust J, Buonavista N, Gross JD. Programmed cell death in Dictyostelium. J Cell Sci 1994, 107, 2691–2704.

-

Welburn SC, Dale C, Ellis D, Beecroft R, Pearson TW. Apoptosis in procyclic Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense in vitro. Cell Death Differ 1996, 3, 229–236. [Google Scholar]

-

Olie RA, Durrieu F, Cornillon S, Loughran G, Gross J et al. Apparent caspase independence of programmed cell death in Dictyostelium. Curr Biol 1998, 8, 955–958. [Google Scholar]

-

Verdi A, Berman F, Rozenberg T, Hadas O, Kaplan A, Levine A. PCD of the dinoflagellate Peridinium gutanense is mediated by CO2 limitation and oxidative stress. Curr Biol 1999, 9, 1061–1064. [Google Scholar]

-

Al-Olayan EM, Williams GT, Hurd H. Apoptosis in the malaria protozoan, Plasmodium berghei: a possible mechanism for limiting intensity of infection in the mosquito. Int J Parasitol 2002, 32, 1133–1143. [CrossRef]

-

Nguewa PA, Fuertes MA, Valladares B, Alonso C, Pérez JM. Programmed cell death in trypanosomatids: a way to maximize their biological fitness? Trends Parasitol 2004, 20, 375–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Koutsogiannis Z, MacLeod ET, Maciver SK. G418 induces programmed cell death in Acanthamoeba through the elevation of intracellular calcium and cytochrome c translocation. Parasitol Res 2019, 118, 641–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

Martín-Navarro CM, López-Arencibia A, Sifaoui I, Reyes-Batlle M, Valladares B et al. Statins and voriconazole induce programmed cell death in Acanthamoeba castellanii. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015, 59, 2817–2824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

Martín-Navarro CM, López-Arencibia A, Sifaoui I, Reyes-Batlle M, Fouque E et al. Amoebicidal activity of caffeine and maslinic acid by the induction of programmed cell death in Acanthamoeba. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2017, 61, e02660–e02616. [Google Scholar]

-

Baig AM, Lalani S, Khan NA. Apoptosis in Acanthamoeba castellanii belonging to the T4 genotype. J Basic Microbiol 2017, 57.

-

Sifaoui I, López-Arencibia A, Martín-Navarro CM, Reyes-Batlle M, Wagner C et al. Programmed cell death in Acanthamoeba castellanii Neff induced by several molecules present in olive leaf extracts. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0183795. [Google Scholar]

-

Lopez-Arencibia A, Reyes-Batlle M, Freijo MB, McNaughton-Smith G, Martín-Rodríguez P, et al. In vitro activity of 1H-phenalen-1-one derivatives against Acanthamoeba castellanii Neff and their mechanisms of cell death. Exp Parasitol 2017, 183, 218–223. [CrossRef]

-

Moon EK, Choi H-S, Kong H-H, Quan F-S. Polyhexamethylene biguanide and chloroquine induce programmed cell death in Acanthamoeba castellanii. Exp Parasitol 2018, 191, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

Villalba JD, Gomez C, Medel O, Sanchez V, Carrero CJ, Ishiwara PDG. Programmed cell death in Entamoeba histolytica induced by aminoglycoside G148. Microbiology 2007, 153, 3852–3863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niculescu, VF. Growth of Entamoeba invadens in sediments with metabolically repressed bacteria leads to multicellularity and redefinition of the amoebic cell system. Roum Arch Microbiol Immunol 2013, 72, 25–48. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Niculescu, VF. The stem cell biology of the protist pathogen Entamoeba invadens in the context of eukaryotic stem cell evolution. Stem Cell Biol Res 2015. [CrossRef]

-

Krishnan D, Ghosh SK. Cellular events of multinucleated giant cell formation during the encystation of Entamoeba invadens. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2018, 31, 262. [Google Scholar]

-

Hazra S, Kalyan Dinda S, Kumar Mondal N, et al. Giant cells: Multiple cells unite to survive. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2023, 13, 1220589. [CrossRef]

-

Morel A-P, Ginestier C, Pommier RM, Cabaud O, Ruiz E, et al. A stemness-related ZEB1-MSRB3 axis governs cellular pliancy and breast cancer genome stability. Nat Med 2017, 23, 568–578. [CrossRef]

-

Chen X, Pappo A, Dyer MA. Pediatric solid tumor genomics and developmental pliancy. Oncogene 2015, 34, 5207–5215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

De Blander H, Morel A-P, Senaratne AP, Ouzounova M, Puisieux A. Cellular plasticity: a route to senescence exit and tumorigenesis. Cancers 2021, 13, 45.

-

Krtolica A, Parrinello S, Lockett S, Desprez PY, Campisi J. Senescent fibroblasts promote epithelial cell growth and tumorigenesis: a link between cancer and aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2001, 98, 12072–12077. [CrossRef]

-

Gorgoulis V, Adams PD, Alimonti A, Bennett DC, Bischof O, et al. Cellular Senescence: Defining a Path Forward. Cell 2019, 179, 813–827. [CrossRef]

-

Saleh T, Tyutyunyk-Massey L, Gewirtz DA. Tumor cell escape from therapy-induced senescence as a model of disease recurrence after dormancy. Cancer Res 2019, 79, 1044–1046. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabisz, M. , & Skladanowski, A. Cancer stem cells and escape from drug-induced premature senescence in human lung tumor cells: Implications for drug resistance and in vitro drug screening models. Cell Cycle 2009, 8, 3208–3217. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

-

Milanovic M, Fan DNY, Belenki D, Däbritz JHM, et al. Senescence-associated reprogramming promotes cancer stemness. Nature 2018, 553, 96–100. [CrossRef]

-

Yu Y, Schleich K, Yue B, Ji S, Lohneis P et al. Targeting the senescence-overriding cooperative activity of structurally unrelated H3K9 demethylases in melanoma. Cancer Cell 2018, 33, 785. [CrossRef]

-

Faget DV, Ren Q, Stewart SA. Unmasking senescence: context-dependent effects of SASP in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2019, 19, 439–453. [CrossRef]

-

Chang BD, Broude EV, Dokmanovic M, Zhu H, Ruth A, et al. A senescence-like phenotype distinguishes tumor cells that undergo terminal proliferation arrest after exposure to anticancer agents. Cancer Res 1999, 59, 3761–3767.

-

Greten FR, Grivennikov SI. Inflammation and cancer: triggers, mechanisms, and consequences. Immunity 2019, 51, 27–41. [CrossRef]

-

Fane M, Weeraratna AT. How the ageing microenvironment influences tumour progression. Nat Rev Cancer 2020, 20, 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

Calcinotto A, Kohli J, Zagato E, Pellegrini L, Demaria M, Alimonti A. Cellular senescence: aging, cancer, and injury. Physiol Rev 2019, 99, 1047–1078.

-

Huang W, Hickson LJ, Eirin A, Kirkland JL, Lerman LO et al. Cellular senescence: the good, the bad and the unknown. Nat Rev Nephrol 2022, 18.

-

Sarkisian CJ, Keister BA, Stairs DB, Boxer RB, Moody SE, et al. Dose-dependent oncogene-induced senescence in vivo and its evasion during mammary tumorigenesis. Nat Cell Biol 2007, 9, 493–505. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Soto-Gamez A, Quax WJ, Demaria M. Regulation of survival networks in senescent cells: from mechanisms to interventions. J Mol Biol 2019, 431, 2629–2643. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

O’Sullivan EA, Wallis R, Mossa F, et al. The paradox of senescent-marker positive cancer cells: challenges and opportunities. npj Aging 2024, 10, 41. [CrossRef]

-

Hernandez-Segura A, Nehme J, Demaria M. Hallmarks of cellular senescence. Trends Cell Biol 2018, 28, 436–453.

-

57.Takahashi A, Ohtani N, Yamakoshi K, Iida S, Tahara H et al. Mitogenic signaling and the p16INK4a–Rb pathway cooperate to enforce irreversible cellular senescence. Nat Cell Biol 2006, 8, 1291–1297. [CrossRef]

-

Schmitt CA, Fridman JS, Yang M, Lee S, Baranov E, et al. A senescence program controlled by p53 and p16INK4a contributes to the outcome of cancer therapy. Cell 2002, 109, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

te Poele RH, Okorokov AL, Jardine L, Cummings J, Joel SP. DNA damage is able to induce senescence in tumor cells in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Res 2002, 62, 1876–1883. [Google Scholar]

-

Roberson RS, Kussick SJ, Vallieres E, Chen S-YJ, Wu DY. Escape from therapy-induced accelerated cellular senescence in p53-null lung cancer cells and in humans.

-

Han Z, Wei W, Dunaway S, Darnowski JW, Calabresi P et al. Role of p21 in apoptosis and senescence of human colon cancer cells treated with camptothecin. J Biol Chem 2002, 277, 17154–17160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

Peiris-Pagès M, Sotgia F, Lisanti MP. Chemotherapy induces the cancer-associated fibroblast phenotype, activating paracrine Hedgehog-GLI signaling in breast cancer cells. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 10728–10745. [CrossRef]

-

Demaria M, O'Leary MN, Chang J, Shao L, Liu S et al. Cellular senescence promotes adverse effects of chemotherapy and cancer relapse. Cancer Discov 2017, 7, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

Herranz N, Gallage S, Mellone M, Wuestefeld T, Klotz et al. mTOR regulates MAPKAPK2 translation to control the senescence-associated secretory phenotype. Nat Cell Biol 2015, 17, 1205–1217. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Rodier F, Coppé JP, Patil CK, Hoeijmakers WA, Muñoz DP, et al. Persistent DNA damage signaling triggers senescence-associated inflammatory cytokine secretion. Nat Cell Biol 2009, 11, 973–979. [CrossRef]

-

Childs BG, Baker DJ, Kirkland JL, Campisi J, Deursen JM. Senescence and apoptosis: dueling or complementary cell fates? EMBO Rep 2014, 15, 1139–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Was H, Barszcz K, Czarnecka J, Kowalczyk A, Uzarowska E, et al. Bafilomycin A1 triggers proliferative potential of senescent cancer cells in vitro and in NOD/SCID mice. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 9303–22. [CrossRef]

-

Lapasset L, Milhavet O, Prieur A, Besnard E, Babled A, et al. Rejuvenating senescent and centenarian human cells by reprogramming through the pluripotent state. Genes Dev 2011, 25, 2248–2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

Nicaise AM, Wagstaff LJ, Willis CM, Paisie C, Chandok N, et al. Cellular senescence in progenitor cells contributes to diminished remyelination potential in progressive multiple sclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2019, 116, 9030–9039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

Zhu P, Zhang C, Gao Y, Wu F, Zhou Y, Wu WS. The transcription factor Slug represses p16Ink4a and regulates murine muscle stem cell aging. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 2568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen Z, Trotman LC, Shaffer D, Lin HK, Dotan ZA, et al. Crucial role of p53-dependent cellular senescence in suppression of Pten-deficient tumorigenesis. Nature 2005, 436, 725–730. [CrossRef]

- Burd CE, Sorrentino JA, Clark KS, Darr DB, Krishnamurthy J, et al. Monitoring 79.

- Serrano M, Lin AW, McCurrach ME, Beach D, Lowe SW. Oncogenic Ras provokes premature cell senescence associated with accumulation of P53 and P16(INK4a). Cell 1997, 88, 593–602. [CrossRef]

-

Gosselin K, Deruy E, Martien S, Vercamer C, Bouali F, et al. Senescent keratinocytes die by autophagic programmed cell death. Am J Pathol 2009, 174, 423–435. [CrossRef]

-

Shain AH, Yeh I, Kovalyshyn I, Sriharan A, Talevich E, et al. The genetic evolution of melanoma from precursor lesions. N Engl J Med 2015, 373, 1926–1936. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Castro-Vega LJ, Jouravleva K, Liu W-Y, Martinez C, Gestraud P, et al. Telomere crisis in kidney epithelial cells promotes the acquisition of a microRNA signature retrieved in aggressive renal cell carcinomas. Carcinogenesis 2013, 34, 1173–1180. [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsova AY, Seget K, Moeller GK, de Pagter MS, de Roos JADM, et al. Chromosomal instability, tolerance of mitotic errors, and multidrug resistance are promoted by tetraploidization in human cells. Cell Cycle 2015, 14, 2810–2820. [CrossRef]

- Galanos P, Vougas K, Walter D, Polyzos A, Maya-Mendoza A, et al. Chronic p53-independent p21 expression causes genomic instability by deregulating replication licensing. Nat Cell Biol 2016, 18, 777–789. [CrossRef]

- Komseli E-S, Pateras IS, Krejsgaard T, Stawiski K, Rizou SV, et al. A prototypical non-malignant epithelial model to study genome dynamics and concurrently monitor microRNAs and proteins in situ during oncogene-induced senescence. BMC Genomics 2018, 19, 37. [CrossRef]

- Zampetidis C, Galanos P, Angelopoulou A, Zhu Y, Karamitros T, et al. Genomic instability is an early event driving chromatin reorganization and escape from oncogene-induced senescence. bioRxiv 2020.

-