Submitted:

09 January 2025

Posted:

09 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Overview

2. Clinical Features

3. Surveillance from the Diagnosis of FAP to Surgery

4. Factors Determining the Timing of Surgery

5. Surgical Treatment

5.1. Selection of Surgical Procedure

5.2. Surgical Treatment for FAP with Advanced Colorectal Cancer

5.3. Surgical Techniques for Mesenteric Lengthening in IPAA

5.4. Surgical Approach

5.5. Disadvantages of Undergoing Surgery

| Postoperative infectious complications | |

| Anastomotic leakage | |

| Pelvic abscess | |

| Fistula | |

| Pouch-related complications | |

| Pouch dysfunction (frequent bowel movements, fecal incontinence, difficulty in defecation due to stenosis) | |

| Pouchitis | |

| Others | |

| Deterioration of the body image and self-esteem | |

| Decreasing fertility and the sexual function |

6. Surveillance After Surgical Treatments

| Examination | Comment |

| Colonoscopy | |

| After IRA | Typically annual, but biannual is acceptable depending on polyp burden |

| After IPAA | For small amount of rectal mucosa, AZT mucosa, and ileal pouch |

| Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy | Gastric polyps and duodenal polyps/cancer |

| Abdominal CT | Desmoid tumors |

| Thyroid ultrasound | Thyroid cancer |

| Brain CT | Brain tumor |

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tomita N, Ishida H, Tanakaya K, Yamaguchi T, Kumamoto K, Tanaka T, Hinoi T, Miyakura Y, Hasegawa H, Takayama T, Ishikawa H, Nakajima T, Chino A, Shimodaira H, Hirasawa A, Nakayama Y, Sekine S, Tamura K, Akagi K, Kawasaki Y, Kobayashi H, Arai M, Itabashi M, Hashiguchi Y, Sugihara K; Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon, Rectum. Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum (JSCCR) guidelines 2020 for the Clinical Practice of Hereditary Colorectal Cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. 2021 Aug;26(8):1353-1419. PMID: 34185173. [CrossRef]

- Bussey HJR, Morson BC: Familial Polyposis Coli. In: Lipkin M, Good RA 8eds): Gastrointestinal Tract Cancer. Sloan-Kettering Institute Cancer Series. Springer, Boston, MA, 1978.

- Iwama T, Tamura K, Morita T, Hirai T, Hasegawa H, Koizumi K, Shirouzu K, Sugihara K, Yamamura T, Muto T, Utsunomiya J; Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum. A clinical overview of familial adenomatous polyposis derived from the database of the Polyposis Registry of Japan. Int J Clin Oncol. 2004 Aug;9(4):308-16. PMID: 15375708. [CrossRef]

- Nielsen M, Hes FJ, Nagengast FM et al (2007) Germline mutations in APC and MUTYH are responsible for the majority of families with attenuated familial adenomatous polyposis. Clin Genet 71:427–433.

- Burt RW, Leppert MF, Slattery ML, Samowitz WS, Spirio LN, Kerber RA, Kuwada SK, Neklason DW, Disario JA, Lyon E, Hughes JP, Chey WY, White RL. Genetic testing and phenotype in a large kindred with attenuated familial adenomatous polyposis. Gastroenterology. 2004 Aug;127(2):444-51. PMID: 15300576. [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi H, Ishida H, Ueno H, Hinoi T, Inoue Y, Ishida F, Kanemitsu Y, Konishi T, Yamaguchi T, Tomita N, Matsubara N, Watanabe T, Sugihara K. Association between the age and the development of colorectal cancer in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis: a multi-institutional study. Surg Today. 2017 Apr;47(4):470-475. Epub 2016 Aug 9.PMID: 27506752. [CrossRef]

- Jasperson KW, Patel SG, Ahnen DJ (1993–2020) APC-associated polyposis conditions. 1998 Dec 18 [updated 2017 Feb 2 In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, et al., editors. GeneReviews® [Internet]. University of Washington, Seattle. Available via http:// www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1245/.

- Vasen HF, Möslein G, Alonso A, Aretz S, Bernstein I, Bertario L, Blanco I, Bülow S, Burn J, Capella G, Colas C, Engel C, Frayling I, Friedl W, Hes FJ, Hodgson S, Järvinen H, Mecklin JP, Møller P, Myrhøi T, Nagengast FM, Parc Y, Phillips R, Clark SK, de Leon MP, Renkonen-Sinisalo L, Sampson JR, Stormorken A, Tejpar S, Thomas HJ, Wijnen J. Guidelines for the clinical management of familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP). Gut. 2008 May;57(5):704-13. Epub 2008 Jan 14.PMID: 18194984. [CrossRef]

- Lynch PM, Morris JS, Wen S, Advani SM, Ross W, Chang GJ, Rodriguez-Bigas M, Raju GS, Ricciardiello L, Iwama T, Rossi BM, Pellise M, Stoffel E, Wise PE, Bertario L, Saunders B, Burt R, Belluzzi A, Ahnen D, Matsubara N, Bülow S, Jespersen N, Clark SK, Erdman SH, Markowitz AJ, Bernstein I, De Haas N, Syngal S, Moeslein G. A proposed staging system and stage-specific interventions for familial adenomatous polyposis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016 Jul;84(1):115-125.e4. Epub 2016 Jan 6.PMID: 26769407. [CrossRef]

- Septer S, Lawson CE, Anant S, Attard T. Familial adenomatous polyposis in pediatrics: natural history, emerging surveillance and management protocols, chemopreventive strategies, and areas of ongoing debate. Fam Cancer. 2016 Jul;15(3):477-85. PMID: 27056662. [CrossRef]

- Rozen P, Macrae F. Familial adenomatous polyposis: The practical applications of clinical and molecular screening. Fam Cancer. 2006;5(3):227-35. PMID: 16998668. [CrossRef]

- Mori Y, Ishida H, Chika N, Ito T, Amano K, Chikatani K, Takeuchi Y, Kono M, Shichijo S, Chino A, Nagasaki T, Takao A, Takao M, Nakamori S, Sasaki K, Akagi K, Yamaguchi T, Tanakaya K, Naohiro T, Ajioka Y. Usefulness of genotyping APC gene for individualizing management of patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Int J Clin Oncol. 2023 Dec;28(12):1641-1650. Epub 2023 Oct 18.PMID: 37853284. [CrossRef]

- Sturt NJ, Gallagher MC, Bassett P, Philp CR, Neale KF, Tomlinson IP, Silver AR, Phillips RK. Evidence for genetic predisposition to desmoid tumours in familial adenomatous polyposis independent of the germline APC mutation. Gut. 2004 Dec;53(12):1832-6. PMID: 15542524. [CrossRef]

- Crabtree MD, Tomlinson IP, Talbot IC, Phillips RK. Variability in the severity of colonic disease in familial adenomatous polyposis results from differences in tumour initiation rather than progression and depends relatively little on patient age. Gut. 2001 Oct;49(4):540-3. PMID: 11559652. [CrossRef]

- Olsen KØ, Juul S, Bülow S, Järvinen HJ, Bakka A, Björk J, Oresland T, Laurberg S. Female fecundity before and after operation for familial adenomatous polyposis. Br J Surg. 2003 Feb;90(2):227-31. PMID: 12555301. [CrossRef]

- Rozen P, Samuel Z, Rabau M, Goldman G, Shomrat R, Legum C, Orr-Urtreger A. Familial adenomatous polyposis at the Tel Aviv Medical Center: demographic and clinical features. Fam Cancer. 2001;1(2):75-82. PMID: 14574001. [CrossRef]

- Eccles DM, Lunt PW, Wallis Y, Griffiths M, Sandhu B, McKay S, Morton D, Shea-Simonds J, Macdonald F. An unusually severe phenotype for familial adenomatous polyposis. Arch Dis Child. 1997 Nov;77(5):431-5. PMID: 9487968. [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa H, Mutoh M, Iwama T, Suzuki S, Abe T, Takeuchi Y, Nakamura T, Ezoe Y, Fujii G, Wakabayashi K, Nakajima T, Sakai T. Endoscopic management of familial adenomatous polyposis in patients refusing colectomy. Endoscopy. 2016 Jan;48(1):51-5. Epub 2015 Sep 9. PMID: 26352809. [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa H, Yamada M, Sato Y, Tanaka S, Akiko C, Tajika M, Doyama H, Takayama T, Ohda Y, Horimatsu T, Sano Y, Tanakaya K, Ikematsu H, Saida Y, Ishida H, Takeuchi Y, Kashida H, Kiriyama S, Hori S, Lee K, Tashiro J, Kobayashi N, Nakajima T, Suzuki S, Mutoh M; J-FAPP Study III Group. Intensive endoscopic resection for downstaging of polyp burden in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis (J-FAPP Study III): A multicenter prospective interventional study. Endoscopy. 2023 Apr;55(4):344-352. PMID: 36216266. [CrossRef]

- Aziz O, Athanasiou T, Fazio VW, Nicholls RJ, Darzi AW, Church J, Phillips RK, Tekkis PP. Meta-analysis of observational studies of ileorectal versus ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for familial adenomatous polyposis. Br J Surg. 2006 Apr;93(4):407-17. PMID: 16511903. [CrossRef]

- Ten YV, Tillyashakhov M, Islamov H, Ziyaev Y. The risk of malignization incidence in patients with polyps and polyposis of the colon and rectum. Ann Oncol. 2019;30:ix37.

- Ardoino I, Signoroni S, Malvicini E, Ricci MT, Biganzoli EM, Bertario L, Occhionorelli S, Vitellaro M. Long-term survival between total colectomy versus proctocolectomy in patients with FAP: a registry-based, observational cohort study. Tumori. 2020 Apr; 106(2): 139-148. [CrossRef]

- Poylin VY, Shaffer VO, Felder SI, Goldstein LE, Goldberg JE, Kalady MF, Lightner AL, Feingold DL, Paquette IM; Clinical Practice Guidelines Committee of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons. The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Inherited Adenomatous Polyposis Syndromes. Dis Colon Rectum. 2024 Feb 1;67(2):213-227. PMID: 37682806. [CrossRef]

- Church J, Burke C, McGannon E, Pastean O, Clark B. Predicting polyposis severity by proctoscopy: how reliable is it? Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:1249–1254.

- Nieuwenhuis MH, Bülow S, Björk J, Järvinen HJ, Bülow C, Bisgaard ML, Vasen HF. Genotype predicting phenotype in familial adenomatous polyposis: a practical application to the choice of surgery. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009 Jul;52(7):1259-63. PMID: 19571702. [CrossRef]

- Aelvoet AS, Struik D, Bastiaansen BAJ, Bemelman WA, Hompes R, Bossuyt PMM, Dekker E. Colectomy and desmoid tumours in familial adenomatous polyposis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fam Cancer. 2022 Oct;21(4):429-439. PMID: 35022961. [CrossRef]

- von Roon AC, Will OC, Man RF, et al. Mucosectomy with handsewn anastomosis reduces the risk of adenoma formation in the anorectal segment after restorative proctocolectomy for familial adenomatous polyposis. Ann Surg. 2011;253:314–317.

- Tatsuta K, Sakata M, Iwaizumi M, Okamoto K, Yoshii S, Mori M, Asaba Y, Harada T, Shimizu M, Kurachi K, Takeuchi H. Long-term prognosis after stapled and hand-sewn ileal pouch-anal anastomoses for familial adenomatous polyposis: a multicenter retrospective study. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2024 Mar 2;39(1):32. PMID: 38431759. [CrossRef]

- Rottoli M, Tanzanu M, Lanci AL, Gentilini L, Boschi L, Poggioli G. Mesenteric lengthening during pouch surgery: technique and outcomes in a tertiary centre. Updates Surg. 2021 Apr;73(2):581-586. PMID: 33492620. [CrossRef]

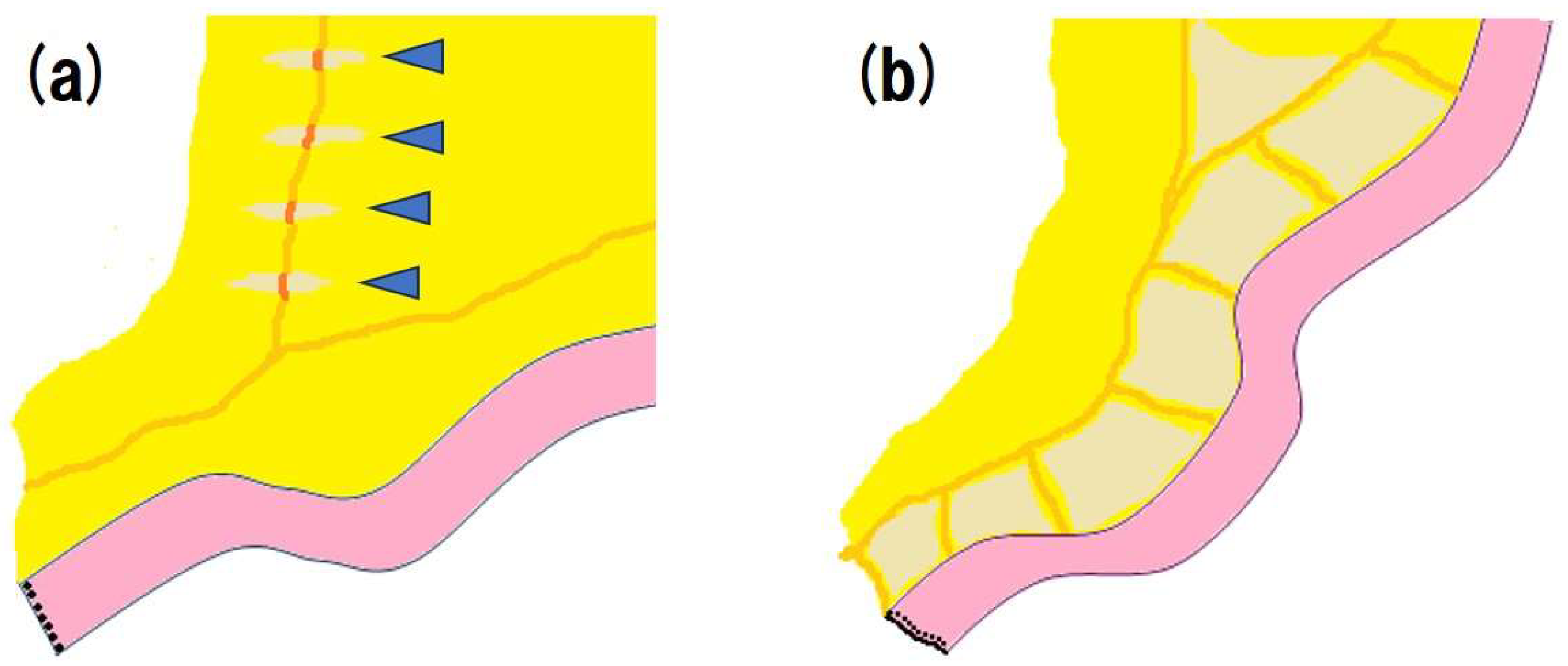

- Baig MK, Weiss EG, Nogueras JJ, Wexner SD. Lengthening of small bowel mesentery: stepladder incision technique. Am J Surg. 2006 May;191(5):715-7. PMID: 16647367. [CrossRef]

- Smith L, Friend WG, Medwell SJ. The superior mesenteric artery. The critical factor in the pouch pull-through procedure. Dis Colon Rectum. 1984 Nov;27(11):741-4. PMID: 6499610. [CrossRef]

- Martel P, Majery N, Savigny B, Sezeur A, Gallot D, Malafosse M. Mesenteric lengthening in ileoanal pouch anastomosis for ulcerative colitis: Is high division of the superior mesenteric pedicle a safe procedure? Dis Colon Rectum. 1998 Jul;41(7):862-6; discussion 866-7. PMID: 9678371. [CrossRef]

- Cherqui D, Valleur P, Perniceni T, Hautefeuille P. Inferior reach of ileal reservoir in ileoanal anastomosis. Experimental anatomic and angiographic study. Dis Colon Rectum. 1987 May;30(5):365-71. PMID: 3568927. [CrossRef]

- Martel P, Blanc P, Bothereau H, Malafosse M, Gallot D. Comparative anatomical study of division of the ileocolic pedicle or the superior mesenteric pedicle for mesenteric lengthening. Br J Surg. 2002 Jun;89(6):775-8. PMID: 12027990. [CrossRef]

- Ueno H, Kobayashi H, Konishi T, Ishida F, Yamaguchi T, Hinoi T, Kanemitsu Y, Inoue Y, Tomita N, Matsubara N, Komori K, Ozawa H, Nagasaka T, Hasegawa H, Koyama M, Akagi Y, Yatsuoka T, Kumamoto K, Kurachi K, Tanakaya K, Yoshimatsu K, Watanabe T, Sugihara K, Ishida H. Prevalence of laparoscopic surgical treatment and its clinical outcomes in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis in Japan. Int J Clin Oncol. 2016 Aug;21(4):713-722. PMID: 26820718. [CrossRef]

- Konishi T, Ishida H, Ueno H, Kobayashi H, Hinoi T, Inoue Y, Ishida F, Kanemitsu Y, Yamaguchi T, Tomita N, Matsubara N, Watanabe T, Sugihara K. Feasibility of laparoscopic total proctocolectomy with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis and total colectomy with ileorectal anastomosis for familial adenomatous polyposis: results of a nationwide multicenter study. Int J Clin Oncol. 2016 Oct;21(5):953-961. PMID: 27095110. [CrossRef]

- Campos FG. Surgical treatment of familial adenomatous polyposis: dilemmas and current recommendations. World J Gastroenterol. 2014 Nov 28;20(44):16620-9. PMID: 25469031. [CrossRef]

- Kjaer MD, Laursen SB, Qvist N, Kjeldsen J, Poornoroozy PH. Sexual function and body image are similar after laparoscopy-assisted and open ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. World J Surg. 2014 Sep;38(9):2460-5. PMID: 24711157. [CrossRef]

- Fajardo AD, Dharmarajan S, George V, Hunt SR, Birnbaum EH, Fleshman JW, Mutch MG. Laparoscopic versus open 2-stage ileal pouch: laparoscopic approach allows for faster restoration of intestinal continuity. J Am Coll Surg. 2010 Sep;211(3):377-83. PMID: 20800195. [CrossRef]

- Heuthorst L, Wasmann KATGM, Reijntjes MA, Hompes R, Buskens CJ, Bemelman WA. Ileal Pouch-anal Anastomosis Complications and Pouch Failure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg Open. 2021 Jun 21;2(2):e074. eCollection 2021 Jun. PMID: 37636549. [CrossRef]

- Okita Y, Araki T, Kawamura M, Kondo S, Inoue M, Kobayashi M, Toiyama Y, Ohi M, Tanaka K, Inoue Y, Uchida K, Mohri Y, Kusunoki M. Clinical features and management of afferent limb syndrome after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for ulcerative colitis. Surg Today. 2016 Oct;46(10):1159-65. Epub 2016 Jan 22. PMID: 26801343. [CrossRef]

- Kjaer MD, Laursen SB, Qvist N, Kjeldsen J, Poornoroozy PH. Sexual function and body image are similar after laparoscopy-assisted and open ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. World J Surg. 2014 Sep;38(9):2460-5. PMID: 24711157. [CrossRef]

- Oresland T, Palmblad S, Ellström M, Berndtsson I, Crona N, Hultén L. Gynaecological and sexual function related to anatomical changes in the female pelvis after restorative proctocolectomy. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1994 May;9(2):77-81. PMID: 8064194. [CrossRef]

- Koskenvuo L, Renkonen-Sinisalo L, Järvinen HJ, Lepistö A. Risk of cancer and secondary proctectomy after colectomy and ileorectal anastomosis in familial adenomatous polyposis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2014 Feb;29(2):225-30. Epub 2013 Nov 30. PMID: 24292488. [CrossRef]

- Campos FG, Perez RO, Imperiale AR, Seid VE, Nahas SC, Cecconello I. Surgical treatment of familial adenomatous polyposis: ileorectal anastomosis or restorative proctolectomy? Arq Gastroenterol. 2009 Oct-Dec;46(4):294-9. PMID: 20232009. [CrossRef]

- Sriranganathan D, Kilic Y, Nabil Quraishi M, Segal JP. Prevalence of pouchitis in both ulcerative colitis and familial adenomatous polyposis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Colorectal Dis. 2022;24:27–39.

| Classical FAP | |||

| severe FAP | sparse FAP | attenuated FAP | |

| The number of adenomas | more than 1000 | 100-1000 | 10-100 |

| Endoscopic features | A normal mucosa cannot be observed | A normal mucosa is visualized | |

| The median age at which half of the cancers develop (years) | 41 | 48 | 59 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).