Submitted:

08 January 2025

Posted:

09 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

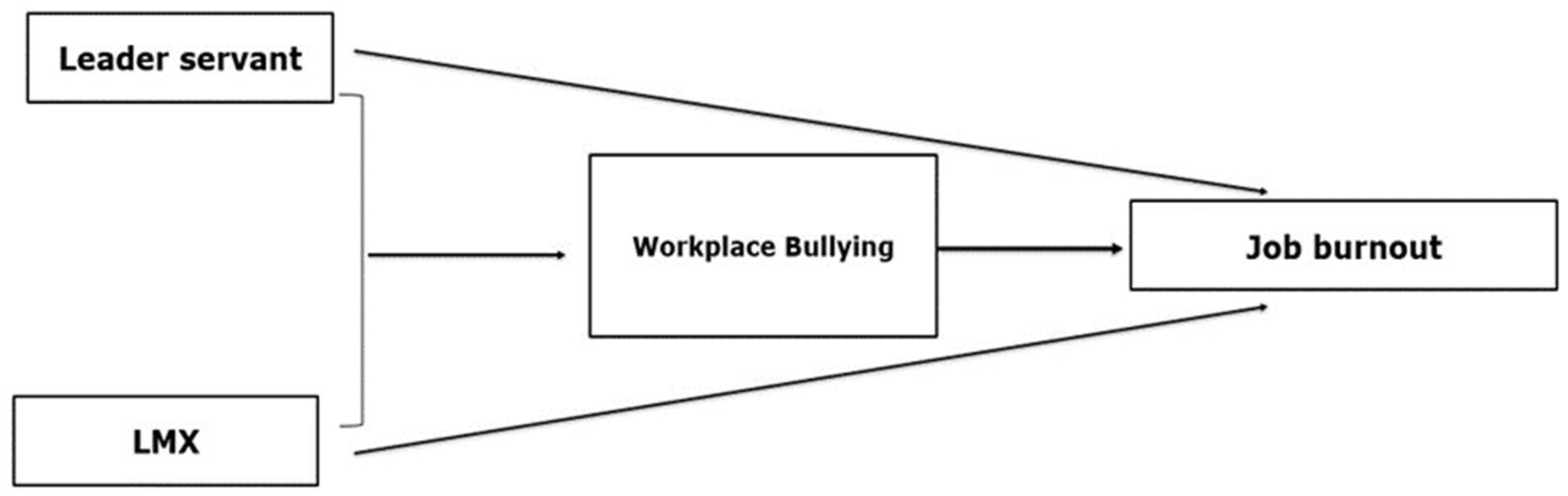

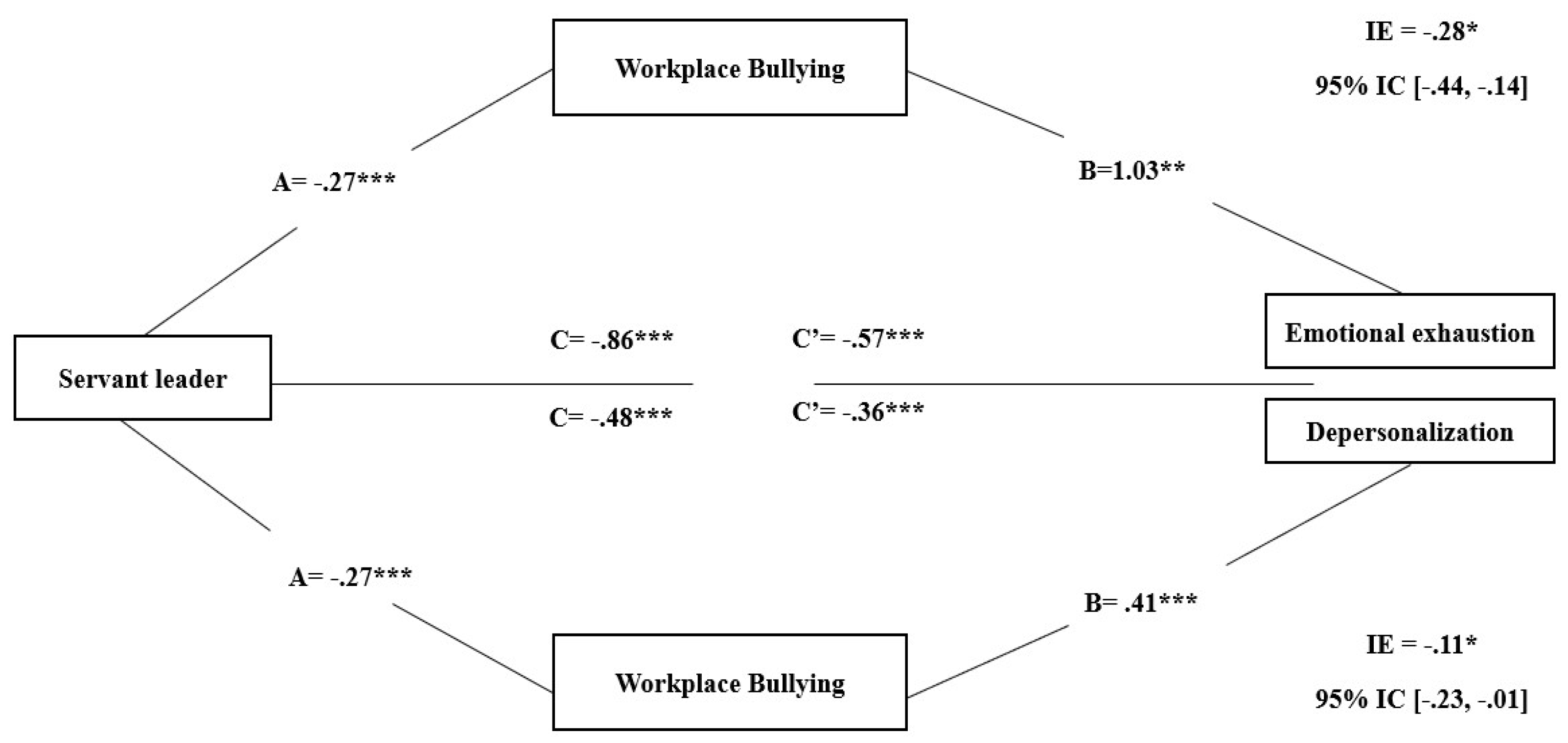

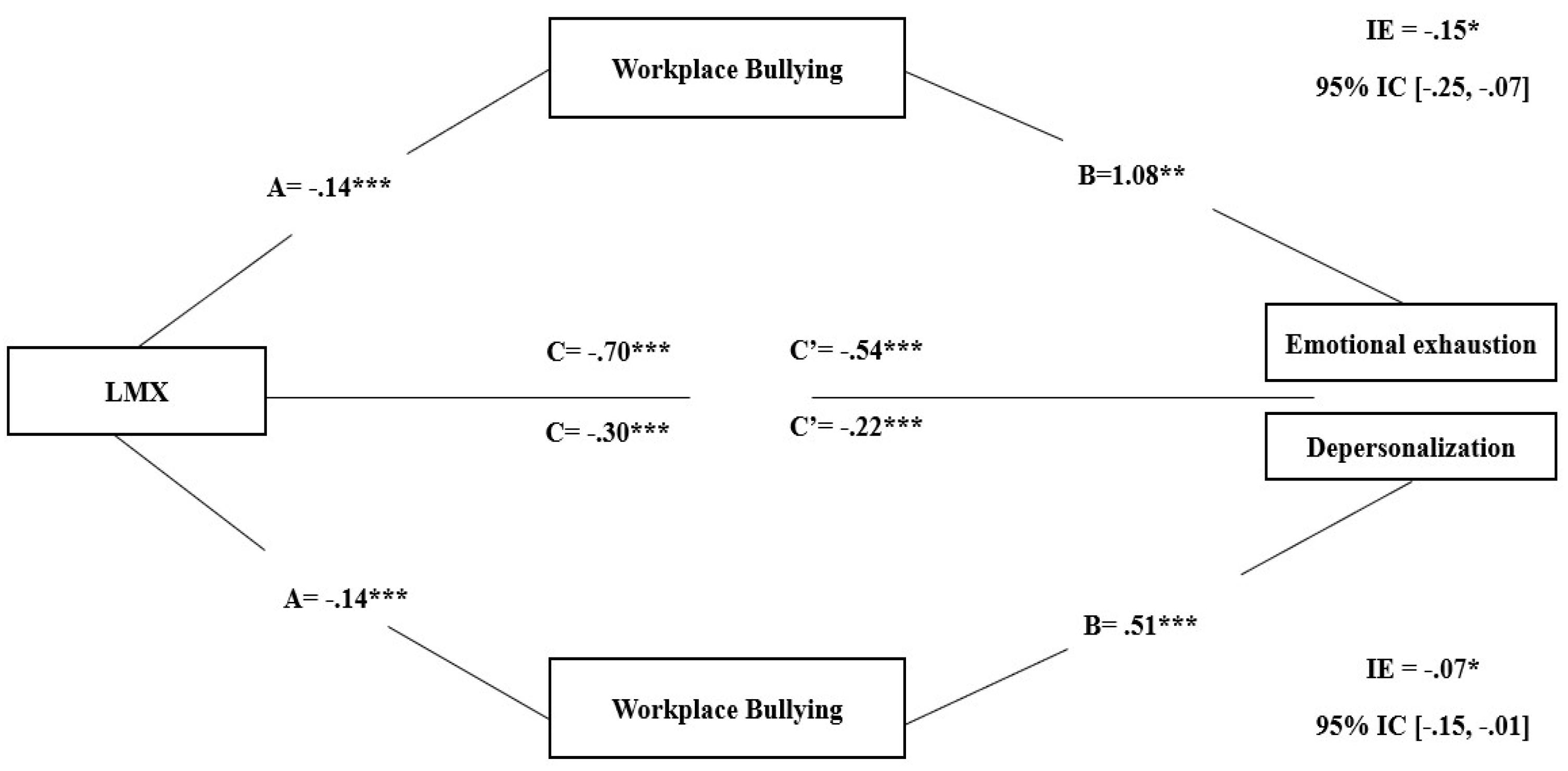

The aim of this study was to examine the relationships between servant leadership, leader-member exchange (LMX) and burnout in the business and finance sectors. More specifically, we explored the indirect effects of workplace bullying in the relationship between these two kinds of leadership and burnout. A self-reported online employee questionnaire in Hauts de France was filled out by 228 employees from two business sectors. The results showed that servant leadership and LMX were negatively related to emotional exhaustion and depersonalization. Mediation analyses using the Hayes and Preacher (2014) method showed that bullying played a mediating role in the relationship between servant leadership, LMX, and emotional exhaustion. The servant and LMX types of leadership had a significant impact on the prevention of burnout and mobbing, insofar they helped to establish positive relationships and reduce the risk of ill-being.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Servant Leadership and Burnout

1.2. Leader-Member Exchange and Burnout

1.3. The Mediating Role of Bullying in Burnout

2. Methods

2.1. Procedure

2.2. Participants

2.3. Measures

3. Results

3.1. Correlationnal Analyses

3.2. Mediations Analyses

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations and Avenues for Future Research

4.2. Practical Implications

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E. Burnout in organizational settings. Appl. Soc. Psychol. Ann. 1984, 5, 133–153. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach, C.; M. Leiter, M. Understanding the burnout experience: Recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry: Offic. J. World Psychiat. Assoc. (WPA) 2016, 15, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bianchi, R.; Laurent, E.; Schonfeld, I.S.; Bietti, L.M.; Mayor, E. Memory bias toward emotional information in burnout and depression. J. Health Psychol. 2020, 25, 1567–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Meng, Y. How leader–member exchange relates to subjective well-being in grassroots officials: The mediating roles of job insecurity and job burnout. Public Perf. Manag. Rev. 2023, 46, 1180–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Leiter, M.P.; Maslach, C. Burnout: 35 years of research and practice. Career Dev. Int. 2009, 14, 204–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavella, G.; Hadzi-Pavlovic, D.; Parker, G. (2021). Burnout: Redefining its key symptoms. Psychiat. Res. 2021, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntsame Sima, M. Pour un modèle explicatif de l’épuisement professionnel et du bien-être psychologique au travail: Vers une validation prévisionnelle et transculturelle (Doctoral dissertation, Lille 3), 2012.

- Malola, P.; Desrumaux, P. L’épuisement émotionnel dans la fonction publique hospitalière: Effets du harcèlement moral, de la justice organisationnelle et de l’engagement affectif via le soutien social [Emotional exhaustion in the hospital civil service: Effects of moral bullying, organizational justice and affective commitment via social support]. Annales Médico-Psychol., 2020, 178, 852–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Leiter, M. Early predictors of job burnout and engagement. The J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 498–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, F.S.; Angelico (2018). Burnout Syndrome in bank employees: A literature review. Temas em Psicologia 2018, 26, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, C.H.; Lankau, M. Preventing burnout: The effects of LMX and mentoring on socialization, role stress, and burnout. Hum. Resource Manag. 2009, 48, 417–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahon, D. Can using a servant-leadership model of supervision mitigate against burnout and secondary trauma in the health and social care sector? Leadership in Health Services 2021, 34, 198–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chughtai, A.A. Servant leadership and follower outcomes: Mediating effects of organizational identification and psychological safety. J. Psychol. 2016, 150, 866–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Dierendonck, D. Servant leadership: A review and synthesis. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 1228–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Liden, R.C.; Liao, C.; Wayne, S.J. Does manager servant leadership lead to follower serving behaviors? It depends on follower self-interest. J. of Appl. Psychol. 2021, 106, 152–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, D.; Liu, S.-M.; Xin, H. Servant leadership behavior: Effects on leaders’ work-family relationship. Soc. Behav. Pers.: An Int. J. 2020, 48, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trépanier, S.G.; Peterson, C.; Fernet, C.; Austin, S. How tyrannical leadership relates to workplace bullying and turnover intention over time: The role of coworker support. Scand. J. Psychol. 2023, 65, 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudrias, V.; Trépanier, S.-G.; Salin, D. A systematic review of research on the longitudinal consequences of workplace bullying and the mechanisms involved. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2021, 56, 101508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M.B.; Einarsen, S. Outcomes of exposure to workplace bullying: A meta-analytic review. Work Stress 2012, 26, 309–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgi, G.; Arcangeli, G.; Perminiene, M.; Lorini, C.; Ariza-Montes, A.; Fiz-Perez, J.; Di Fabio, A.; Mucci, N. Work-related stress in the banking sector: A review of incidence, correlated factors, and major consequences. Frontiers Psychol. 2017, 8, 2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coetzer, M.F.; Bussin, M.H.R.; Geldenhuys, M. Servant leadership and work-related well-being in a construction company. SA J. Indus. Psychol. 2017, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, N.; Aydın, S.; Ongun, G. The impacts of servant leadership and organizational politics on burnout: A research among mid-level managers. Int. J. Bus. Admin. 2016, 7, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Faraz, N.A.; Ahmed, F.; Iqbal, M.K.; Saeed, U.; Mughal, M.F.; Raza, A. Curbing nurses’ burnout during COVID-19: The roles of servant leadership and psychological safety. J. Nursing Manag. 2021, 29, 2383–2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Guan, C.; Cui, T.; Cai, S.; Liu, D. Servant leadership, team reflexivity, coworker support climate, and employee creativity: A multilevel perspective. J. Leadersh. Org. Stud. 2021, 28, 465–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saint-Michel, S. & Wielhorski, N. (2011). Style de leadership, LMX et engagement organisationnel des salariés : Le genre du leader a-t-il un impact ?. [Leadership style, LMX and organizational commitment of employees: Does the gender of the leader have an impact?]. @GRH 2011, 1, 13–38. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, L.N.; Witteloostuijn, A. Leader-member exchange, communication frequency and burnout. Discussion Paper Series /Tjalling C. Koopmans Res. Institute 2010, 10-08, 1–41. [Google Scholar]

- Schermuly, C.C.; Meyer, B. Good relationships at work: The effects of leader–member exchange and team–member exchange on psychological empowerment, emotional exhaustion, and depression. J. Organ. Behav. 2016, 37, 673–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terpstra-Tong, J.; Ralston, D.A.; Treviño, L.J.; Naoumova, I.; de la Garza Carranza, M.T.; Furrer, O.; Li, Y.; Darder, F.L. The quality of leader-member exchange (LMX): A multilevel analysis of individual-level, organizational-level and societal-level antecedents. J. Int. Manag. 2020, 26, 100760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebron, M.J.; Tabak, F.; Shkoler, O.; Rabenu, E. Counterproductive work behaviors toward organization and leader-member exchange: The mediating roles of emotional exhaustion and work engagement. Organ. Manag. J. 2018, 15, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, S.; Vidyarthi, P.; Rolnicki, S. Leader-member exchange and organizational citizenship behaviors: Contextual effects of leader power distance and group task interdependence. Leadersh. Quart. 2018, 29, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desrumaux, P. Le harcèlement moral au travail : Réponses psychosociales, organisationnelles et cliniques [Bullying at work: Psychosocial, organizational and clinical approaches]. Presses Universitaires Rennes 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Einarsen, S.; Hoel, H.; Zapf, D.; Cooper, C.L. The concept of bullying and harassment at work: The European tradition. In S. Einarsen, H. Hoel, D. Zapf, & C. L. Cooper (Eds.), Bullying and harassment in the workplace: Developments in theory, research, and practice (3rd., pp. 3–54). CRC Press.

- Leymann, H. The content and development of mobbing at work. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 1996, 5, 165–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desrumaux, P.; Hellemans, C.; Malola, P.; Jeoffrion, C. How do cyber- and traditional workplace bullying, organizational justice and social support, affect psychological distress among civil servants? Human Work/ Trav. Hum. 2021, 84, 233–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini, K.; Miyanaji, H.; Din Mohamadi, M. Bullying and burnout in critical care nurses: A cross-sectional descriptive study. Nursing in Critical Care 2023, 28, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’cruz, P.; Noronha, E. Navigating the extended reach: Target experiences of cyberbullying at work. Inform. Organ. 2013, 23, 324–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, S.T.; Kim, S. Meta-regression analyses of relationships between burnout and depression with sampling and measurement methodological moderators. J. Occ. Health Psychol. 2022, 27, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desrumaux, P.; Gillet, N.; Nicolas, C. Direct and indirect effects of beliefs in a just world and supervisor support on burnout via bullying. International Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manzano-Garcia, G.; Desrumaux, P.; Ayala Calvo, J.C.; Bouterfas, N. The impact of social support on emotional exhaustion and workplace bullying in social workers. Eur. J. Social Work 2022, 25, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseer, S.; Raja, U. Why does workplace bullying affect victims’ job strain? Perceived organization support and emotional dissonance as resource depletion mechanisms. Curr Psychol 2021, 40, 4311–4323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emilisa, N.; Kusumaditra, R. Servant leadership’s dimensions and deviant workplace behavior: Perspective at five-star hotels in Jakarta Indonesia. J. Manag. Info. 2024, 8, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapointe, É.; Vandenberghe, C. Examination of the relationships between servant leadership, organizational commitment, and voice and antisocial behaviors. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 148, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeel, A.; Batool, S.; Daisy, K.M.H.; Madni, Z.A.; Khan, M.K. Leader-member exchange and creative idea validation: The role of helping and bullying. Asian Acad. Manag. J. 2022, 27, 107–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Islam, T.; D’Cruz, P.; Noronha, E. Caring for those in your charge: The role of servant leadership and compassion in managing bullying in the workplace. Int. J. Confl. Manag. 2023, 34, 125–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.; Sung, S.Y.; Choi, J.N. How does servant leadership reduce employee burnout? The mediating role of employee thriving and moderating role of servant leadership dimensions. J. Bus. Psychol. 2018, 33, 737–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, T.H.; Day, N.; Meglich, P. City of discontent? The influence of perceived organizational culture, LMX, and newcomer status on reported bullying in a municipal workplace. Employee Respons. Rights J. 2018, 30, 119–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tharwat Saad Kamar, A.; Abd El-monem, O.M.; Fawzy Abuzid, H. (2023). The impact of workplace bullying on the relationship between leader-member exchange relationship (LMX) quality and organizational cynicism. 2023. https://bjhs.journals.ekb.eg.

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, N.P. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. An. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, A.F.; Preacher, K.J. Statistical mediation analysis with a multicategorical independent variable. British J. of Math. Stat. Psychol. 2014, 67, 451–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E. Maslach Burnout Inventory. Research Edition. Consulting Psychologists Press, 1981.

- Bocéréan, C.; Dupret, E.; Feltrin, M. Maslach Burnout Inventory – General Survey: French validation in a representative sample of employees, SCIREA. J. of Health 2019, 3, 24–61. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrhart, M.G. Leadership and procedural justice climate as antecedents of unit-level organizational citizenship behavior. Person. Psychol. 2004, 57, 61–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graen, G.B.; Novak, M.; Sommerkamp, P. The effects of leader-member exchange and job design on productivity and satisfaction: Testing a dual attachment model. Organ. Beh. Hum. Perf. 1982, 30, 109–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scandura, T.A.; Graen, G.B. Moderating effects of initial leader-member exchange status on the effects of a leadership intervention. J. Appl. Psychol. 1984, 69, 428–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scandura, T.; Schriesheim, C.A. Leader-member exchange and supervisor career mentoring as complementary constructs in leadership research. Acad. Manag. J. 1994, 37, 1588–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saint-Michel, S.; Wielhorski, N. Style de leadership, LMX et engagement organisationnel des salariés : Le genre du leader a-t-il un impact ? [Leadership style, LMX and employee organizational commitment: Does the gender of the leader have an impact?]. @GRH. 2011, 1, 13–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einarsen, S.; Hoel, H.; Notelaers, G. Measuring exposure to bullying and harassment at work: Validity, factor structure and psychometric properties of the negative acts questionnaire-revised. Work Stress 2009, 23, 24–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis (3rd Ed.). The Guilford Press, 2022.

- Karasek, R.; Brisson, C.; Kawakami, N.; Houtman, I.; Bongers, P.; Amick, B. The job content questionnaire (JCQ): An instrument for internationally comparative assessment of psychological job characteristics. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 1998, 3, 322–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halbesleben, J.R.B. Sources of social support and burnout: A meta-analytic test of the conservation of resources model. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 1134–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skakon, J.; Nielsen, K.; Borg, V.; Guzman, J. Are leaders’ well-being, behaviours and style associated with the affective wellbeing of their employees? A systematic review of three decades of research. Work Stress 2010, 24, 107–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.Y.; Chow, C.W.; Loi, R. The interactive effect of LMX and LMX differentiation on followers’ job burnout: Evidence from tourism industry in Hong Kong. Int. J. of Human Resource Manag. 2018, 29, 1972–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, S.; Kim, D.Y.; Kim, M. How perceived interpersonal justice relates to job burnout and intention to leave: The role of leader–member exchange and cognition-based trust in leaders. Asian J. of Social Psycho. 2014, 17, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T.A.; Bono, J.; Locke, E. Personality and job satisfaction: The mediating role of job characteristics. J. Appl. Psychol. 2000, 85, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conway, J. M.; Lance, C.E. What reviewers should expect from authors regarding common method bias in organizational research. J. of Bus. Psychol. 2010, 25, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindell, M.K.; Whitney, D.J. Accounting for common method variance in cross-sectional research designs. J. of Applied Psychology 2001, 86, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genty V, Fantoni-Quinton, S.F. La prévention des risques psychosociaux en entreprise : Les rôles et les responsabilités de l’employeur et du médecin du travail. [Preventing psychosocial risks in the workplace: The roles and responsibilities of the employer and the occupational physician] Arch. Mal. Prof. Env. 2018, 79:745–51.

- Newman, A.; Schwarz, G.; Cooper, B.; Sendjaya, S. How servant leadership influences organizational citizenship behavior : The roles of LMX, empowerment, and proactive personality. J. of Bus. Ethics 2017, 145, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Classification | n | % |

| Age | 18-30 31-40 41-50 51- + |

103 49 34 42 |

45.17 21.49 14.91 18.42 |

| Gender | Male Female |

73 155 |

32.89 67.98 |

| Marital statut | Single without children Single with child Couple without children Couple with child |

65 74 17 72 |

28.51 32.46 7.46 31.57 |

| Education background | Bachelor degree or above Junior college or below |

111 117 |

48.68 51.32 |

| Employment status | CDI CDD |

196 32 |

85.96 14.04 |

| Business sector | Public Private |

41 187 |

17.98 82.02 |

| Professionnal | Business Finance |

174 54 |

76.32 23.68 |

| variables | M/7 | ET | |||||

| Leadership servant | 2.94 | .45 | .86 | ||||

| Leader-member exchange | 2;84 | .60 | .79** | .87 | |||

| Workplace bullying | 1.58 | .30 | -.41** | -.28** | .82 | ||

| Emotional exhaustion | 2.01 | 1.07 | -.36** | -.39** | .39** | .89 | |

| Depersonalization | 1.05 | .76 | -.28** | -.23** | .25** | .33** | .61 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).