Submitted:

09 January 2025

Posted:

09 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Thyroid hormones (TH) regulate metabolism in a homeostatic state in an adult organism. During the prenatal period, prior to establishment of homeostatic mechanisms, TH assume additional functions as key regulators of brain development. Here, we focus on reviewing the role of TH in orchestrating cellular dynamics in a developing brain. We provide evidence that developmental roles of the hormones are predominantly mediated by non-genomic mitochondrial effects of TH due to attenuation of genomic effects of TH that antagonise non-genomic impacts. We argue that the key function of TH signalling during brain development is to orchestrate the tempo of self-organisation of neural progenitor cells. Further, evidence is provided that major neurodevelopmental consequences of hypothyroidism stem from an altered tempo of cellular self-organisation.

Keywords:

Introduction

An Overview of the Signalling Landscape of Thyroid Hormones

Thyroid Hormones: A Broad Evolutionary Perspective

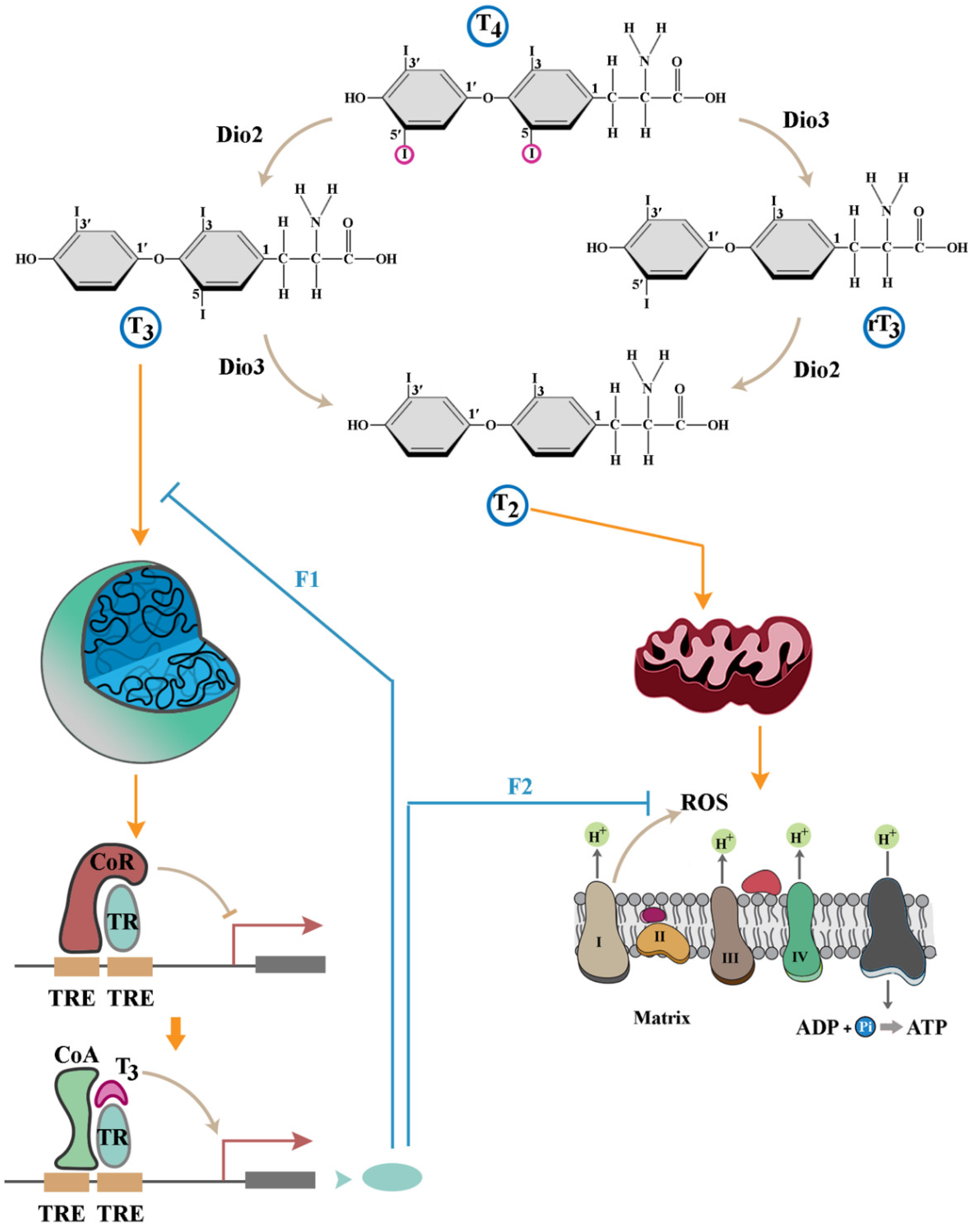

Uncoupling of the Genomic and non-Genomic Impacts of TH During Development

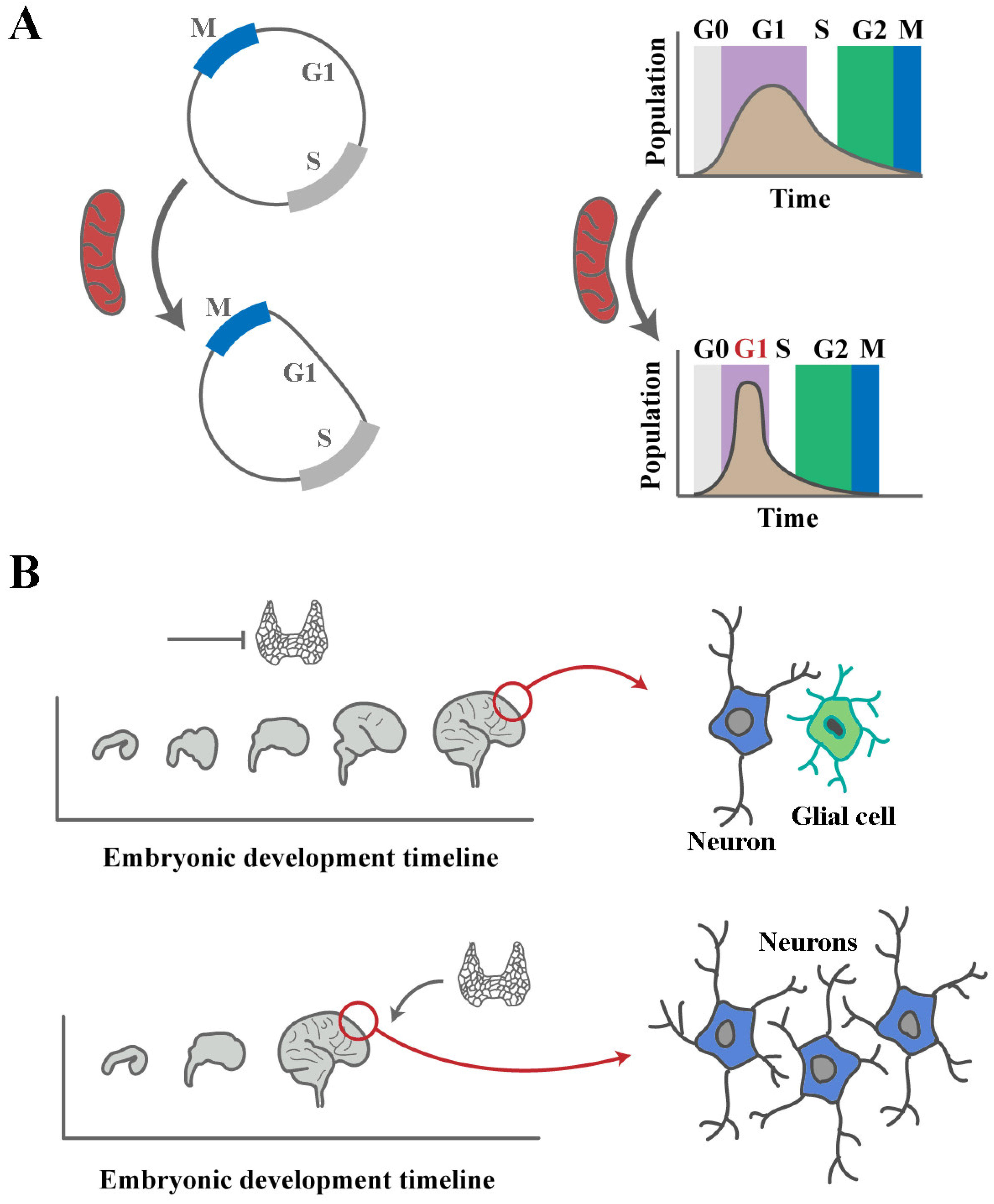

Cellular Self-Organisation and Brain Development: Tempo Informs Function and Spatial Organisation During Organogenesis

Heterochronic Signatures of TH in Brain Development

Conclusion

- TH orchestrate brain development by controlling the balance of competition between receptor-mediated genomic and non-genomic mitochondrial effects.

- A transient suppression of nuclear dynamics facilitates predominance of non-genomic impacts of TH over TR-mediated genomic effects.

- To assume a morphogenic role, TH reprogram mitochondria to produce reactive oxygen species at an amplified rate.

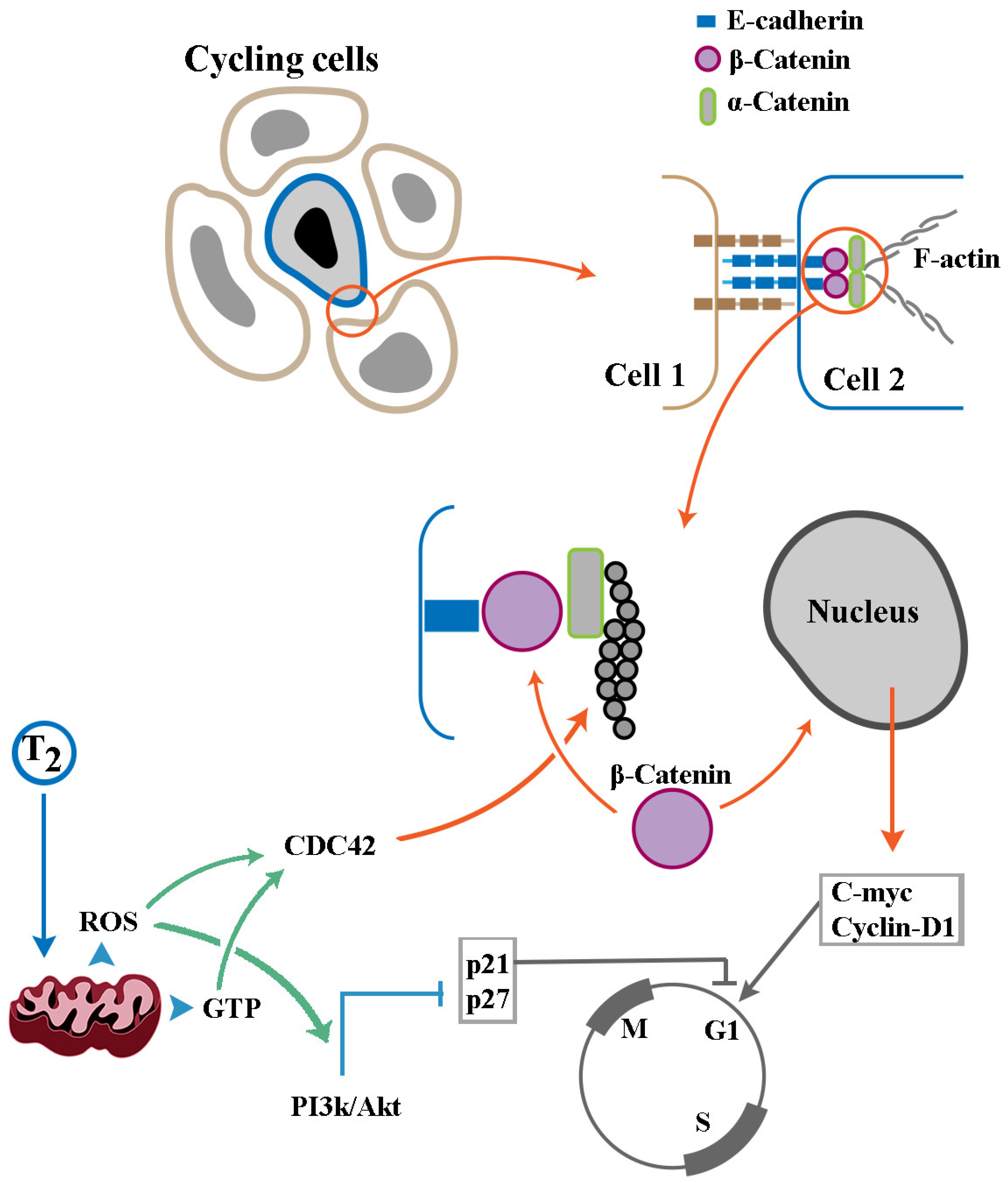

- Transient shift to an oxidising milieu as a result of TH signalling leads to rewiring of certain signalling pathways, an accelerated cell cycle, and enhanced tempo of cellular self-organisation.

- Enhanced tempo of self-organisation in TH signalling is a major determinant of emergence of spatial and functional signatures of cellular self-organisation.

- In hypothyroidism, the reduced tempo of cellular self-organisation underpins key anatomical and functional alterations of a developing brain.

References

- Ahmed, O. M.; El-Gareib, A. W.; El-Bakry, A. M.; Abd El-Tawab, S. M.; Ahmed, R. G. Thyroid hormones states and brain development interactions. Int J Dev Neurosci 2008, 26, 147–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal, J.; Nunez, J. Thyroid hormones and brain development. Eur J Endocrinol 1995, 133, 390–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Angelis, M.; Maity-Kumar, G.; Schriever, S. C.; Kozlova, E. V.; Muller, T. D.; Pfluger, P. T.; Curras-Collazo, M. C.; Schramm, K. W. Development and validation of an LC-MS/MS methodology for the quantification of thyroid hormones in dko MCT8/OATP1C1 mouse brain. J Pharm Biomed Anal 2022, 221, 115038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dussault, J. H.; Ruel, J. Thyroid hormones and brain development. Annu Rev Physiol 1987, 49, 321–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilby, M. D. Thyroid hormones and fetal brain development. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2003, 59, 280–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pemberton, H. N.; Franklyn, J. A.; Kilby, M. D. Thyroid hormones and fetal brain development. Minerva Ginecol 2005, 57, 367–78. [Google Scholar]

- Rovet, J. F. The role of thyroid hormones for brain development and cognitive function. Endocr Dev 2014, 26, 26–43. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gil-Ibanez, P.; Garcia-Garcia, F.; Dopazo, J.; Bernal, J.; Morte, B. Global Transcriptome Analysis of Primary Cerebrocortical Cells: Identification of Genes Regulated by Triiodothyronine in Specific Cell Types. Cereb Cortex 2017, 27, 706–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonard, J. L. Non-genomic actions of thyroid hormone in brain development. Steroids 2008, 73, 1008–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giammanco, M.; Di Liegro, C. M.; Schiera, G.; Di Liegro, I. Genomic and Non-Genomic Mechanisms of Action of Thyroid Hormones and Their Catabolite 3,5-Diiodo-L-Thyronine in Mammals. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zoeller, T. R.; Dowling, A. L.; Herzig, C. T.; Iannacone, E. A.; Gauger, K. J.; Bansal, R. Thyroid hormone, brain development, and the environment. Environ Health Perspect 2002, 110 Suppl 3, 355–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delange, F. Neonatal screening for congenital hypothyroidism: results and perspectives. Horm Res 1997, 48, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, R. , History of congenital hypothyroidism. In Neonatal Thyroid Screening, 1980; pp 51-59.

- Morte, B.; Manzano, J.; Scanlan, T.; Vennstrom, B.; Bernal, J. Deletion of the thyroid hormone receptor alpha 1 prevents the structural alterations of the cerebellum induced by hypothyroidism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2002, 99, 3985–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, M. E.; Seifert, E. L. Thyroid hormone effects on mitochondrial energetics. Thyroid 2008, 18, 145–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soboll, S. Thyroid hormone action on mitochondrial energy transfer. Biochim Biophys Acta 1993, 1144, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwata, R.; Casimir, P.; Vanderhaeghen, P. Mitochondrial dynamics in postmitotic cells regulate neurogenesis. Science 2020, 369, 858–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozsoy, S.; Vujovic, F.; Simonian, M.; Valova, V.; Hunter, N.; Farahani, R. M. Cannibalized erythroblasts accelerate developmental neurogenesis by regulating mitochondrial dynamics. Cell Rep 2021, 35, 108942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckervordersandforth, R.; Ebert, B.; Schaffner, I.; Moss, J.; Fiebig, C.; Shin, J.; Moore, D. L.; Ghosh, L.; Trinchero, M. F.; Stockburger, C.; Friedland, K.; Steib, K.; von Wittgenstein, J.; Keiner, S.; Redecker, C.; Holter, S. M.; Xiang, W.; Wurst, W.; Jagasia, R.; Schinder, A. F.; Ming, G. L.; Toni, N.; Jessberger, S.; Song, H.; Lie, D. C. Role of Mitochondrial Metabolism in the Control of Early Lineage Progression and Aging Phenotypes in Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis. Neuron 2017, 93, 1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khacho, M.; Clark, A.; Svoboda, D. S.; Azzi, J.; MacLaurin, J. G.; Meghaizel, C.; Sesaki, H.; Lagace, D. C.; Germain, M.; Harper, M. E.; Park, D. S.; Slack, R. S. Mitochondrial Dynamics Impacts Stem Cell Identity and Fate Decisions by Regulating a Nuclear Transcriptional Program. Cell Stem Cell 2016, 19, 232–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khacho, M.; Slack, R. S. Mitochondrial dynamics in the regulation of neurogenesis: From development to the adult brain. Dev Dyn 2018, 247, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vujovic, F.; Simonian, M.; Hughes, W. E.; Shepherd, C. E.; Hunter, N.; Farahani, R. M. Mitochondria facilitate neuronal differentiation by metabolising nuclear-encoded RNA. Cell Commun Signal 2024, 22, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vujovic, F.; Hunter, N.; Farahani, R. M. Notch ankyrin domain: evolutionary rise of a thermodynamic sensor. Cell Commun Signal 2022, 20, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chuma, S.; Kiyosue, K.; Akiyama, T.; Kinoshita, M.; Shimazaki, Y.; Uchiyama, S.; Sotoma, S.; Okabe, K.; Harada, Y. Implication of thermal signaling in neuronal differentiation revealed by manipulation and measurement of intracellular temperature. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 3473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belinsky, G. S.; Antic, S. D. Mild hypothermia inhibits differentiation of human embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cells. Biotechniques 2013, 55, 79–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, K. A.; Sandiford, S. D.; Skerjanc, I. S.; Li, S. S. Reactive oxygen species and the neuronal fate. Cell Mol Life Sci 2012, 69, 215–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, K. E.; Koniski, A. D.; Malik, J.; Palis, J. Circulation is established in a stepwise pattern in the mammalian embryo. Blood 2003, 101, 1669–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodenfels, J.; Neugebauer, K. M.; Howard, J. Heat Oscillations Driven by the Embryonic Cell Cycle Reveal the Energetic Costs of Signaling. Dev Cell, 2019; 48, 646–658.e6. [Google Scholar]

- Kashiwagi, A.; Hanada, H.; Yabuki, M.; Kanno, T.; Ishisaka, R.; Sasaki, J.; Inoue, M.; Utsumi, K. Thyroxine enhancement and the role of reactive oxygen species in tadpole tail apoptosis. Free Radic Biol Med 1999, 26, 1001–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S. Y.; Leonard, J. L.; Davis, P. J. Molecular aspects of thyroid hormone actions. Endocr Rev 2010, 31, 139–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Spek, A. H.; Fliers, E.; Boelen, A. The classic pathways of thyroid hormone metabolism. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2017, 458, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y. F.; Koenig, R. J. Gene regulation by thyroid hormone. Trends Endocrin Met 2000, 11, 207–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannocco, G.; Kizys, M. M. L.; Maciel, R. M.; de Souza, J. S. Thyroid hormone, gene expression, and Central Nervous System: Where we are. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2021, 114, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, A.; Das, S.; Sarkar, P. K. Thyroid hormone promotes glutathione synthesis in astrocytes by up regulation of glutamate cysteine ligase through differential stimulation of its catalytic and modulator subunit mRNAs. Free Radic Biol Med 2007, 42, 617–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Averill-Bates, D. A. The antioxidant glutathione. Vitam Horm 2023, 121, 109–141. [Google Scholar]

- Venditti, P.; Di Meo, S. Thyroid hormone-induced oxidative stress. Cell Mol Life Sci 2006, 63, 414–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, S.; Sahoo, D. K.; Roy, A.; Samanta, L.; Chainy, G. B. Thiol redox status critically influences mitochondrial response to thyroid hormone-induced hepatic oxidative injury: A temporal analysis. Cell Biochem Funct 2010, 28, 126–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y. B. Life Without Thyroid Hormone Receptor. Endocrinology 2021, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchholz, D. R.; Shi, Y. B. Dual function model revised by thyroid hormone receptor alpha knockout frogs. Gen Comp Endocrinol 2018, 265, 214–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gothe, S.; Wang, Z.; Ng, L.; Kindblom, J. M.; Barros, A. C.; Ohlsson, C.; Vennstrom, B.; Forrest, D. Mice devoid of all known thyroid hormone receptors are viable but exhibit disorders of the pituitary-thyroid axis, growth, and bone maturation. Genes Dev 1999, 13, 1329–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segal, J.; Ingbar, S. H. An immediate increase in calcium accumulation by rat thymocytes induced by triiodothyronine: its role in the subsequent metabolic responses. Endocrinology 1984, 115, 160–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segal, J.; Ingbar, S. H. Stimulation by triiodothyronine of the in vitro uptake of sugars by rat thymocytes. J Clin Invest 1979, 63, 507–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segal, J.; Ingbar, S. H. Stimulation of 2-deoxy-D-glucose uptake in rat thymocytes in vitro by physiological concentrations of triiodothyronine, insulin, or epinephrine. Endocrinology 1980, 107, 1354–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, J.; Hardiman, J.; Ingbar, S. H. Stimulation of calcium-ATPase activity by 3,5,3′-tri-iodothyronine in rat thymocyte plasma membranes. A possible role in the modulation of cellular calcium concentration. Biochem J 1989, 261, 749–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettit, F. H.; Roche, T. E.; Reed, L. J. Function of calcium ions in pyruvate dehydrogenase phosphatase activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1972, 49, 563–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glancy, B.; Willis, W. T.; Chess, D. J.; Balaban, R. S. Effect of calcium on the oxidative phosphorylation cascade in skeletal muscle mitochondria. Biochemistry 2013, 52, 2793–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilas-Boas, E. A.; Cabral-Costa, J. V.; Ramos, V. M.; Caldeira da Silva, C. C.; Kowaltowski, A. J. Goldilocks calcium concentrations and the regulation of oxidative phosphorylation: Too much, too little, or just right. J Biol Chem 2023, 299, 102904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farwell, A. P.; Dubord-Tomasetti, S. A.; Pietrzykowski, A. Z.; Stachelek, S. J.; Leonard, J. L. Regulation of cerebellar neuronal migration and neurite outgrowth by thyroxine and 3,3′,5′-triiodothyronine. Brain Res Dev Brain Res 2005, 154, 121–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegrist-Kaiser, C. A.; Juge-Aubry, C.; Tranter, M. P.; Ekenbarger, D. M.; Leonard, J. L. Thyroxine-dependent modulation of actin polymerization in cultured astrocytes. A novel, extranuclear action of thyroid hormone. J Biol Chem, 1990; 265, 5296–302. [Google Scholar]

- Farwell, A. P.; Dubord-Tomasetti, S. A.; Pietrzykowski, A. Z.; Leonard, J. L. Dynamic nongenomic actions of thyroid hormone in the developing rat brain. Endocrinology 2006, 147, 2567–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspenstrom, P. The Rho GTPases have multiple effects on the actin cytoskeleton. Exp Cell Res 1999, 246, 20–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Begum, R.; Nur, E. K. M. S.; Zaman, M. A. The role of Rho GTPases in the regulation of the rearrangement of actin cytoskeleton and cell movement. Exp Mol Med 2004, 36, 358–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sit, S. T.; Manser, E. Rho GTPases and their role in organizing the actin cytoskeleton. J Cell Sci 2011, 124, 679–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.; Rohatgi, R.; Kirschner, M. W. The Arp2/3 complex mediates actin polymerization induced by the small GTP-binding protein Cdc42. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1998, 95, 15362–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heo, J.; Campbell, S. L. Mechanism of redox-mediated guanine nucleotide exchange on redox-active Rho GTPases. J Biol Chem 2005, 280, 31003–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, W. E.; Crespo-Armas, A.; Mowbray, J. The influence of nanomolar calcium ions and physiological levels of thyroid hormone on oxidative phosphorylation in rat liver mitochondria. A possible signal amplification control mechanism. Biochem J 1987, 247, 315–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterling, K.; Milch, P. O.; Brenner, M. A.; Lazarus, J. H. Thyroid hormone action: the mitochondrial pathway. Science 1977, 197, 996–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goglia, F.; Lanni, A.; Barth, J.; Kadenbach, B. Interaction of diiodothyronines with isolated cytochrome c oxidase. FEBS Lett 1994, 346, 295–8. [Google Scholar]

- Lanni, A.; Moreno, M.; Horst, C.; Lombardi, A.; Goglia, F. Specific binding sites for 3,3′-diiodo-L-thyronine (3,3′-T2) in rat liver mitochondria. FEBS Lett 1994, 351, 237–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leary, S. C.; Barton, K. N.; Ballantyne, J. S. Direct effects of 3,5,3′-triiodothyronine and 3,5-diiodothyronine on mitochondrial metabolism in the goldfish Carassius auratus. Gen Comp Endocrinol 1996, 104, 61–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnold, S.; Goglia, F.; Kadenbach, B. 3,5-Diiodothyronine binds to subunit Va of cytochrome-c oxidase and abolishes the allosteric inhibition of respiration by ATP. Eur J Biochem 1998, 252, 325–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groen, A. K.; Wanders, R. J. A.; Westerhoff, H. V.; Vandermeer, R.; Tager, J. M. Quantification of the Contribution of Various Steps to the Control of Mitochondrial Respiration. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1982, 257, 2754–2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ludwig, B.; Bender, E.; Arnold, S.; Huttemann, M.; Lee, I.; Kadenbach, B. Cytochrome C oxidase and the regulation of oxidative phosphorylation. Chembiochem 2001, 2, 392–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bender, E.; Kadenbach, B. The allosteric ATP-inhibition of cytochrome c oxidase activity is reversibly switched on by cAMP-dependent phosphorylation. FEBS Lett 2000, 466, 130–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vujovic, F.; Shepherd, C. E.; Witting, P. K.; Hunter, N.; Farahani, R. M. Redox-Mediated Rewiring of Signalling Pathways: The Role of a Cellular Clock in Brain Health and Disease. Antioxidants (Basel) 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmings, B. A.; Restuccia, D. F. The PI3K-PKB/Akt pathway. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2015, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakahata, S.; Ichikawa, T.; Maneesaay, P.; Saito, Y.; Nagai, K.; Tamura, T.; Manachai, N.; Yamakawa, N.; Hamasaki, M.; Kitabayashi, I.; Arai, Y.; Kanai, Y.; Taki, T.; Abe, T.; Kiyonari, H.; Shimoda, K.; Ohshima, K.; Horii, A.; Shima, H.; Taniwaki, M.; Yamaguchi, R.; Morishita, K. Loss of NDRG2 expression activates PI3K-AKT signalling via PTEN phosphorylation in ATLL and other cancers. Nat Commun 2014, 5, 3393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. C.; Piccini, A.; Myers, M. P.; Van Aelst, L.; Tonks, N. K. Functional analysis of the protein phosphatase activity of PTEN. Biochem J 2012, 444, 457–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. R.; Yang, K. S.; Kwon, J.; Lee, C.; Jeong, W.; Rhee, S. G. Reversible inactivation of the tumor suppressor PTEN by H2O2. J Biol Chem 2002, 277, 20336–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eales, J. G. Iodine metabolism and thyroid-related functions in organisms lacking thyroid follicles: Are thyroid hormones also vitamins? P Soc Exp Biol Med 1997, 214, 302–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyland, A.; Moroz, L. L. Cross-kingdom hormonal signaling: an insight from thyroid hormone functions in marine larvae. J Exp Biol 2005, 208, 4355–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyland, A.; Hodin, J.; Reitzel, A. M. Hormone signaling in evolution and development: a non-model system approach. Bioessays 2005, 27, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyland, A.; Hodin, J. Heterochronic developmental shift caused by thyroid hormone in larval sand dollars and its implications for phenotypic plasticity and the evolution of nonfeeding development. Evolution 2004, 58, 524–38. [Google Scholar]

- Zwahlen, J.; Gairin, E.; Vianello, S.; Mercader, M.; Roux, N.; Laudet, V. The ecological function of thyroid hormones. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2024, 379, 20220511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behringer, V.; Deimel, C.; Hohmann, G.; Negrey, J.; Schaebs, F. S.; Deschner, T. Applications for non-invasive thyroid hormone measurements in mammalian ecology, growth, and maintenance. Horm Behav 2018, 105, 66–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchholz, D. R.; Hsia, S. C. V.; Fu, L. Z.; Shi, Y. B. A dominant-negative thyroid hormone receptor blocks amphibian metamorphosis by retaining corepressors at target genes. Mol Cell Biol 2003, 23, 6750–6758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchholz, D. R.; Tomita, A.; Fu, L. Z.; Paul, B. D.; Shi, Y. B. Transgenic analysis reveals that thyroid hormone receptor is sufficient to mediate the thyroid hormone signal in frog metamorphosis. Mol Cell Biol 2004, 24, 9026–9037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, E.; Heyland, A. Evolution of thyroid hormone signaling in animals: Non-genomic and genomic modes of action. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2017, 459, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Y.; Palli, S. R. Mitochondria dysfunction impairs Tribolium castaneum wing development during metamorphosis. Commun Biol 2022, 5, 1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkey, A. B.; Wong, C. K.; Hoshizaki, D. K.; Gibbs, A. G. Energetics of metamorphosis in Drosophila melanogaster. J Insect Physiol 2011, 57, 1437–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odell, J. P. Energetics of metamorphosis in two holometabolous insect species:: (Lepidoptera: Sphingidae) and (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae). J Exp Zool 1998, 280, 344–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamberlin, M. E. Changes in mitochondrial electron transport chain activity during insect metamorphosis. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2007, 292, R1016–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chouchani, E. E.; Pell, V.; Gaude, E.; Aksentijevic, D.; Sundier, S.; Duchen, M.; Shattock, M.; Frezza, C.; Krieg, T.; Murphy, M.; Uk, M. R. C.; Res, C. I. H.; Trust, G. C.; Fdn, B. H. Ischaemic accumulation of succinate controls reperfusion injury through mitochondrial ROS. Eur J Heart Fail 2015, 17, 29–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, C. T.; Moncada, S. Nitric oxide, cytochrome C oxidase, and the cellular response to hypoxia. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2010, 30, 643–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inoue, M.; Sato, E. F.; Nishikawa, M.; Hiramoto, K.; Kashiwagi, A.; Utsumi, K. Free radical theory of apoptosis and metamorphosis. Redox Rep 2004, 9, 237–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanada, H.; Kashiwagi, A.; Takehara, Y.; Kanno, T.; Yabuki, M.; Sasaki, J.; Inoue, M.; Utsumi, K. Do reactive oxygen species underlie the mechanism of apoptosis in the tadpole tail? Free Radical Bio Med 1997, 23, 294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oleynikov, I. P.; Sudakov, R. V.; Azarkina, N. V.; Vygodina, T. V. Direct Interaction of Mitochondrial Cytochrome c Oxidase with Thyroid Hormones: Evidence for Two Binding Sites. Cells 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagami, T.; Madison, L. D.; Nagaya, T.; Jameson, J. L. Nuclear receptor corepressors activate rather than suppress basal transcription of genes that are negatively regulated by thyroid hormone. Mol Cell Biol 1997, 17, 2642–2648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papandreou, M. E.; Tavernarakis, N. Nucleophagy: from homeostasis to disease. Cell Death Differ 2019, 26, 630–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei-Lotfi, S.; Vujovic, F.; Simonian, M.; Hunter, N.; Farahani, R. M. Programmed genomic instability regulates neural transdifferentiation of human brain microvascular pericytes. Genome Biol 2021, 22, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinduro, O.; Sully, K.; Patel, A.; Robinson, D. J.; Chikh, A.; McPhail, G.; Braun, K. M.; Philpott, M. P.; Harwood, C. A.; Byrne, C.; O’Shaughnessy, R. F. L.; Bergamaschi, D. Constitutive Autophagy and Nucleophagy during Epidermal Differentiation. J Invest Dermatol 2016, 136, 1460–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wedlich-Soldner, R.; Betz, T. Self-organization: the fundament of cell biology. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2018, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petridis, A. K.; El-Maarouf, A.; Rutishauser, U. Polysialic acid regulates cell contact-dependent neuronal differentiation of progenitor cells from the subventricular zone. Dev Dyn 2004, 230, 675–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei-Lotfi, S.; Hunter, N.; Farahani, R. M. Coupled cycling programs multicellular self-organization of neural progenitors. Cell Cycle 2019, 18, 2040–2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toda, S.; Blauch, L. R.; Tang, S. K. Y.; Morsut, L.; Lim, W. A. Programming self-organizing multicellular structures with synthetic cell-cell signaling. Science 2018, 361, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, D.; Chen, S. C.; Prasad, M.; He, L.; Wang, X.; Choesmel-Cadamuro, V.; Sawyer, J. K.; Danuser, G.; Montell, D. J. Mechanical feedback through E-cadherin promotes direction sensing during collective cell migration. Cell 2014, 157, 1146–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aberle, H.; Schwartz, H.; Kemler, R. Cadherin-catenin complex: protein interactions and their implications for cadherin function. J Cell Biochem 1996, 61, 514–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shtutman, M.; Zhurinsky, J.; Simcha, I.; Albanese, C.; D’Amico, M.; Pestell, R.; Ben-Ze’ev, A. The cyclin D1 gene is a target of the beta-catenin/LEF-1 pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1999, 96, 5522–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, T. C.; Sparks, A. B.; Rago, C.; Hermeking, H.; Zawel, L.; da Costa, L. T.; Morin, P. J.; Vogelstein, B.; Kinzler, K. W. Identification of c-MYC as a target of the APC pathway. Science 1998, 281, 1509–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Pan, W. GSK3: a multifaceted kinase in Wnt signaling. Trends Biochem Sci 2010, 35, 161–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, K.; Cho, Y. K.; Breinyn, I. B.; Cohen, D. J. E-cadherin biomaterials reprogram collective cell migration and cell cycling by forcing homeostatic conditions. Cell Rep 2024, 43, 113743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, M. V.; Zaidel-Bar, R. Formin-mediated actin polymerization at cell-cell junctions stabilizes E-cadherin and maintains monolayer integrity during wound repair. Mol Biol Cell 2016, 27, 2844–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Quondamatteo, F.; Lefever, T.; Czuchra, A.; Meyer, H.; Chrostek, A.; Paus, R.; Langbein, L.; Brakebusch, C. Cdc42 controls progenitor cell differentiation and beta-catenin turnover in skin. Genes Dev 2006, 20, 571–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etienne-Manneville, S.; Hall, A. Cdc42 regulates GSK-3beta and adenomatous polyposis coli to control cell polarity. Nature 2003, 421, 753–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malin, J.; Rosa-Birriel, C.; Hatini, V. Pten, PI3K, and PtdIns(3,4,5)P(3) dynamics control pulsatile actin branching in Drosophila retina morphogenesis. Dev Cell, 2024; 59, 1593–1608 e6. [Google Scholar]

- Fukumoto, S.; Hsieh, C. M.; Maemura, K.; Layne, M. D.; Yet, S. F.; Lee, K. H.; Matsui, T.; Rosenzweig, A.; Taylor, W. G.; Rubin, J. S.; Perrella, M. A.; Lee, M. E. Akt participation in the Wnt signaling pathway through Dishevelled. J Biol Chem 2001, 276, 17479–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, J. M.; He, X. C.; Sugimura, R.; Grindley, J. C.; Haug, J. S.; Ding, S.; Li, L. Cooperation between both Wnt/beta-catenin and PTEN/PI3K/Akt signaling promotes primitive hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal and expansion. Genes Dev 2011, 25, 1928–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, M. W.; Sacks, D. B. IQGAP1 as signal integrator: Ca2+, calmodulin, Cdc42 and the cytoskeleton. FEBS Lett 2003, 542, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Kim, S. H.; Higgins, J. M.; Brenner, M. B.; Sacks, D. B. IQGAP1 and calmodulin modulate E-cadherin function. J Biol Chem 1999, 274, 37885–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joyal, J. L.; Annan, R. S.; Ho, Y. D.; Huddleston, M. E.; Carr, S. A.; Hart, M. J.; Sacks, D. B. Calmodulin modulates the interaction between IQGAP1 and Cdc42. Identification of IQGAP1 by nanoelectrospray tandem mass spectrometry. J Biol Chem 1997, 272, 15419–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angst, B. D.; Marcozzi, C.; Magee, A. I. The cadherin superfamily: diversity in form and function. J Cell Sci 2001, 114, 629–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Shao, Y. Y.; Ballock, R. T. Thyroid hormone interacts with the Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway in the terminal differentiation of growth plate chondrocytes. J Bone Miner Res 2007, 22, 1988–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funato, Y.; Michiue, T.; Asashima, M.; Miki, H. The thioredoxin-related redox-regulating protein nucleoredoxin inhibits Wnt-beta-catenin signalling through dishevelled. Nat Cell Biol 2006, 8, 501–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Kambe, F.; Moeller, L. C.; Refetoff, S.; Seo, H. Thyroid hormone induces rapid activation of Akt/protein kinase B-mammalian target of rapamycin-p70S6K cascade through phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in human fibroblasts. Mol Endocrinol 2005, 19, 102–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujita, N.; Sato, S.; Katayama, K.; Tsuruo, T. Akt-dependent phosphorylation of p27Kip1 promotes binding to 14-3-3 and cytoplasmic localization. J Biol Chem 2002, 277, 28706–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alisi, A.; Spagnuolo, S.; Napoletano, S.; Spaziani, A.; Leoni, S. Thyroid hormones regulate DNA-synthesis and cell-cycle proteins by activation of PKCalpha and p42/44 MAPK in chick embryo hepatocytes. J Cell Physiol 2004, 201, 259–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y. H.; Huang, Y. H.; Wu, M. H.; Wu, S. M.; Chi, H. C.; Liao, C. J.; Chen, C. Y.; Tseng, Y. H.; Tsai, C. Y.; Tsai, M. M.; Lin, K. H. Thyroid hormone suppresses cell proliferation through endoglin-mediated promotion of p21 stability. Oncogene 2013, 32, 3904–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambros, V. Control of developmental timing in Caenorhabditis elegans. Curr Opin Genet Dev 2000, 10, 428–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambros, V.; Moss, E. G. Heterochronic genes and the temporal control of C. elegans development. Trends Genet 1994, 10, 123–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rombouts, J.; Gelens, L. Dynamic bistable switches enhance robustness and accuracy of cell cycle transitions. PLoS Comput Biol 2021, 17, e1008231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farahani, R.; Rezaei-Lotfi, S.; Simonian, M.; Hunter, N. Bi-modal reprogramming of cell cycle by MiRNA-4673 amplifies human neurogenic capacity. Cell Cycle 2019, 18, 848–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calder, A.; Roth-Albin, I.; Bhatia, S.; Pilquil, C.; Lee, J. H.; Bhatia, M.; Levadoux-Martin, M.; McNicol, J.; Russell, J.; Collins, T.; Draper, J. S. Lengthened G1 phase indicates differentiation status in human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells Dev 2013, 22, 279–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soufi, A.; Dalton, S. Cycling through developmental decisions: how cell cycle dynamics control pluripotency, differentiation and reprogramming. Development 2016, 143, 4301–4311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chantoux, F.; Francon, J. Thyroid hormone regulates the expression of NeuroD/BHF1 during the development of rat cerebellum. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2002, 194, 157–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, T.; Anney, R.; Taylor, P. N.; Teumer, A.; Peeters, R. P.; Medici, M.; Caseras, X.; Rees, D. A. Effects of Thyroid Status on Regional Brain Volumes: A Diagnostic and Genetic Imaging Study in UK Biobank. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2021, 106, 688–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansen, T. A.; Korevaar, T. I. M.; Mulder, T. A.; White, T.; Muetzel, R. L.; Peeters, R. P.; Tiemeier, H. Maternal thyroid function during pregnancy and child brain morphology: a time window-specific analysis of a prospective cohort. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2019, 7, 629–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madeira, M. D.; Paula-Barbosa, M.; Cadete-Leite, A.; Tavares, M. A. Unbiased estimate of hippocampal granule cell numbers in hypothyroid and in sex-age-matched control rats. J Hirnforsch 1988, 29, 643–50. [Google Scholar]

- Madeira, M. D.; Cadete-Leite, A.; Andrade, J. P.; Paula-Barbosa, M. M. Effects of hypothyroidism upon the granular layer of the dentate gyrus in male and female adult rats: a morphometric study. J Comp Neurol 1991, 314, 171–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madeira, M. D.; Pereira, A.; Cadete-Leite, A.; Paula-Barbosa, M. M. Estimates of volumes and pyramidal cell numbers in the prelimbic subarea of the prefrontal cortex in experimental hypothyroid rats. J Anat 1990, 171, 41–56. [Google Scholar]

- Berbel, P.; Navarro, D.; Auso, E.; Varea, E.; Rodriguez, A. E.; Ballesta, J. J.; Salinas, M.; Flores, E.; Faura, C. C.; de Escobar, G. M. Role of late maternal thyroid hormones in cerebral cortex development: an experimental model for human prematurity. Cereb Cortex 2010, 20, 1462–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Dolado, M.; Ruiz, M.; Del Rio, J. A.; Alcantara, S.; Burgaya, F.; Sheldon, M.; Nakajima, K.; Bernal, J.; Howell, B. W.; Curran, T.; Soriano, E.; Munoz, A. Thyroid hormone regulates reelin and dab1 expression during brain development. J Neurosci 1999, 19, 6979–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balazs, R.; Brooksbank, B. W.; Davison, A. N.; Eayrs, J. T.; Wilson, D. A. The effect of neonatal thyroidectomy on myelination in the rat brain. Brain Res 1969, 15, 219–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malone, M. J.; Rosman, N. P.; Szoke, M.; Davis, D. Myelination of brain in experimental hypothyroidism. An electron-microscopic and biochemical study of purified myelin isolates. J Neurol Sci, 1975; 26, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Noguchi, T.; Sugisaki, T. Hypomyelination in the cerebrum of the congenitally hypothyroid mouse (hyt). J Neurochem 1984, 42, 891–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Pena, A.; Ibarrola, N.; Iniguez, M. A.; Munoz, A.; Bernal, J. Neonatal hypothyroidism affects the timely expression of myelin-associated glycoprotein in the rat brain. J Clin Invest 1993, 91, 812–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamo, A. M.; Aloise, P. A.; Soto, E. F.; Pasquini, J. M. Neonatal hyperthyroidism in the rat produces an increase in the activity of microperoxisomal marker enzymes coincident with biochemical signs of accelerated myelination. J Neurosci Res 1990, 25, 353–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Shaughnessy, K. L.; Thomas, S. E.; Spring, S. R.; Ford, J. L.; Ford, R. L.; Gilbert, M. E. A transient window of hypothyroidism alters neural progenitor cells and results in abnormal brain development. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 4662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kooistra, L.; van der Meere, J. J.; Vulsma, T.; Kalverboer, A. F. Sustained attention problems in children with early treated congenital hypothyroidism. Acta Paediatr 1996, 85, 425–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitra, K.; Wunder, C.; Roysam, B.; Lin, G.; Lippincott-Schwartz, J. A hyperfused mitochondrial state achieved at G-S regulates cyclin E buildup and entry into S phase. P Natl Acad Sci USA 2009, 106, 11960–11965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).