Submitted:

08 January 2025

Posted:

09 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

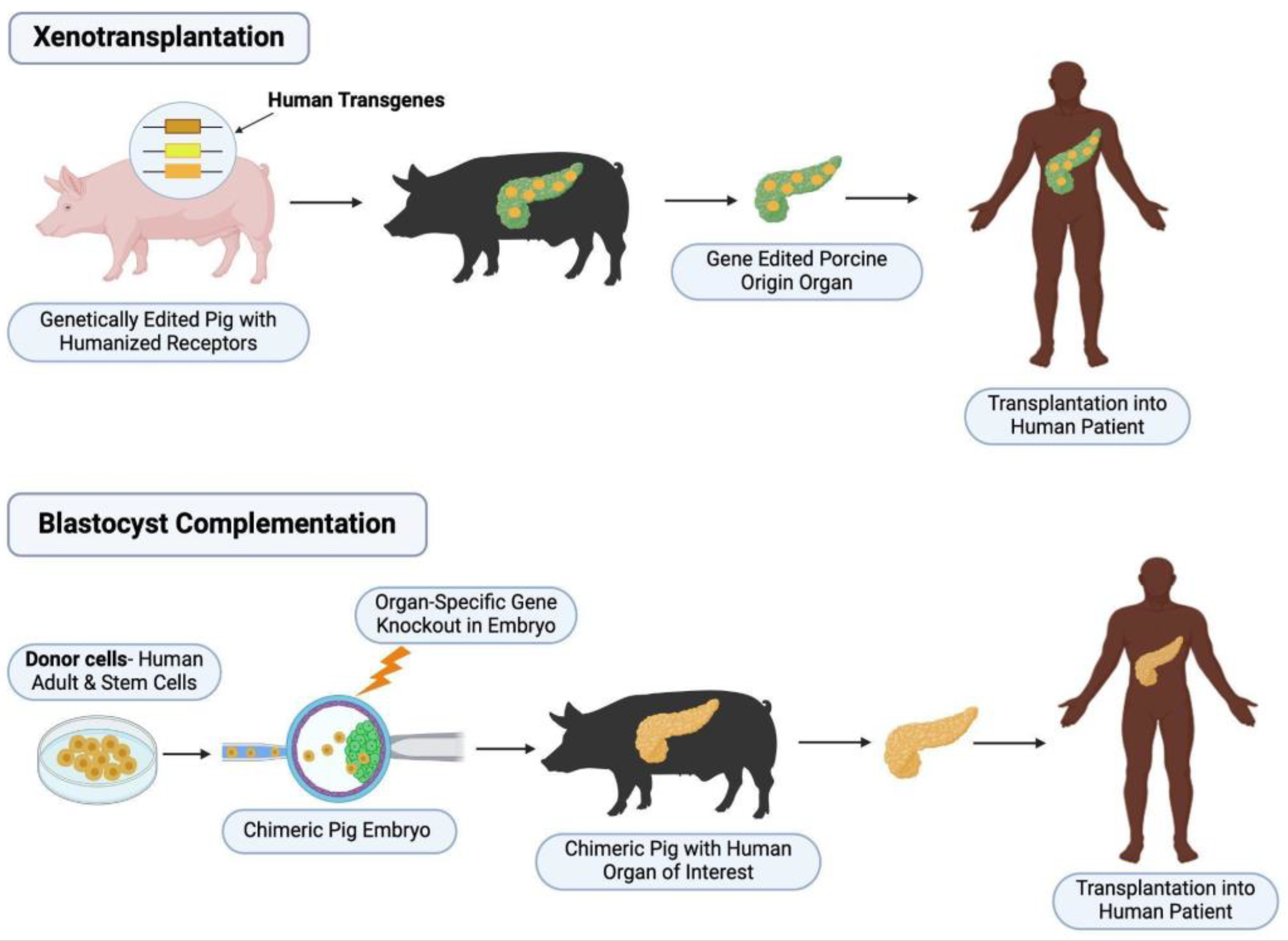

1. Introduction

2. Liver

2.1. Hepatogenesis and Elimination of Hepatic Development

2.2. Application of Blastocyst Complementation

3. Lung

3.1. Lung Development and Its Elimination

3.2. Application of Blastocyst Complementation

4. Kidney

4.1. Nephrogenesis Elimination of Kidney Development

4.2. Application of Blastocyst Complementation

5. Pancreas

5.1. Pancreas Development and Its Elimination

5.2. Application of Blastocyst Complementation

6. Heart

6.1. Cardiogenesis and Elimination of Cardiac Development

6.2. Application of Blastocyst Complementation

7. Thyroid

7.1. Thyroid Embryogenesis and Elimination of Thyroid Development

7.2. Application of Blastocyst Complementation

8. Other: Parathyroid, Thymus

8.1. Development of Thymus and Parathyroid

8.2. Application of Blastocyst Complementation

9. Conclusions and Challenges of Interspecies Chimerism

9.1. Inefficient Chimerism and Survival to Adulthood

9.2. Barriers to Interspecies Chimerism During Development

9.2.1. Single Cell Molecular Approaches to Understand Donor and Host Cell Mechanisms in Chimeric Embryos

9.3. Ethical Considerations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| iPSC | induced pluripotent stem cells |

| ESC | embryonic stem cells |

| KO | knock-out |

References

- Global Observatory on Donation and Transplantation. Data Charts and Tables. Updated 2024. Accessed November 5 2024, November 30, 2024. https://www.transplant-observatory.org/data-charts-and-tables/chart/.

- Health Resources & Services Administration. Organ Donation Statistics. OrganDonor.gov. Updated July 2023. Accessed November 5, 2024. https://www.organdonor.gov/learn/organ-donation-statistics.

- Griffith BP, Goerlich CE, Singh AK, et al. Genetically modified porcine-to-human cardiac xenotransplantation. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(1):35-44. [CrossRef]

- Founta KM, Papanayotou C. In Vivo generation of organs by blastocyst complementation: Advances and challenges. Int J Stem Cells. 2022;15(2):113-121. [CrossRef]

- Chen J, Lansford R, Stewart V, Young F, Alt FW. RAG-2-deficient blastocyst complementation: an assay of gene function in lymphocyte development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90(10):4528-4532. [CrossRef]

- Xiang AP, Mao FF, Li WQ, et al. Extensive contribution of embryonic stem cells to the development of an evolutionarily divergent host. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17(1):27-37. [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Liver Disease. CDC. Updated June 7, 2023. Accessed November 14, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/liver-disease.htm.

- Asgari S, Moslem M, Bagheri-Lankarani K, Pournasr B, Miryounesi M, Baharvand H. Differentiation and transplantation of human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived hepatocyte-like cells. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2013;9(4):493-504. [CrossRef]

- Chen YF, Tseng CY, Wang HW, Kuo HC, Yang VW, Lee OK. Rapid generation of mature hepatocyte-like cells from human induced pluripotent stem cells by an efficient three-step protocol. Hepatology. 2012;55(4):1193-1203. [CrossRef]

- Nagamoto Y, Takayama K, Ohashi K, et al. Transplantation of a human iPSC-derived hepatocyte sheet increases survival in mice with acute liver failure. J Hepatol. 2016;64(5):1068-1075. [CrossRef]

- Zaret KS. From Endoderm to Liver Bud: Paradigms of Cell Type Specification and Tissue Morphogenesis. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2016;117:647-669. [CrossRef]

- Zorn AM. Liver development. 2008 Oct 31. In: StemBook [Internet]. Cambridge (MA): Harvard Stem Cell Institute; 2008-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK27068/. [CrossRef]

- Tachmatzidi EC, Galanopoulou O, Talianidis I. Transcription Control of Liver Development. Cells. 2021;10(8):2026. [CrossRef]

- Zhou W, Nelson ED, Abu Rmilah AA, Amiot BP, Nyberg SL. Stem cell-related studies and stem cell-based therapies in liver diseases. Cell Transplant. 2019;28(9-10):1116-1122. [CrossRef]

- Bort R, Signore M, Tremblay K, Martinez Barbera JP, Zaret KS. Hex homeobox gene controls the transition of the endoderm to a pseudostratified, cell emergent epithelium for liver bud development. Dev Biol. 2006;290(1):44-56. [CrossRef]

- Gauvrit S, Villasenor A, Strilic B, et al. HHEX is a transcriptional regulator of the VEGFC/FLT4/PROX1 signaling axis during vascular development. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):2704. [CrossRef]

- Martinez Barbera JP, Clements M, Thomas P, et al. The homeobox gene Hex is required in definitive endodermal tissues for normal forebrain, liver and thyroid formation. Development. 2000;127(11):2433-2445. [CrossRef]

- Goodings C, Smith E, Mathias E, et al. Hhex is required at multiple stages of adult hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell differentiation. Stem Cells. 2015;33(8):2628-2641. [CrossRef]

- Kubo S, Sun M, Miyahara M, et al. Hepatocyte injury in tyrosinemia type 1 is induced by fumarylacetoacetate and is inhibited by caspase inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(16):9552-9557. [CrossRef]

- Azuma H, Paulk N, Ranade A, et al. Robust expansion of human hepatocytes in Fah-/-/Rag2-/-/Il2rg-/- mice. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25(8):903-910. [CrossRef]

- Matsunari H, Watanabe M, Hasegawa K, et al. Compensation of disabled organogeneses in genetically modified pig fetuses by blastocyst complementation. Stem Cell Reports. 2020;14(1):21-33. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Estevez M, Crane AT, Rodriguez-Villamil P, et al. Liver development is restored by blastocyst complementation of HHEX knockout in mice and pigs. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2021;12(1):292. [CrossRef]

- Simpson SG, Park K-E, Yeddula SGR, et al. Blastocyst complementation generates exogenous donor-derived liver in ahepatic pigs. FASEB J. 2024;38:e70161. [CrossRef]

- Chambers DC, Perch M, Zuckermann A, et al. The International Thoracic Organ Transplant Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Thirty-eighth adult lung transplantation report - 2021; Focus on recipient characteristics. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2021;40(10):1060-1072. [CrossRef]

- Schittny JC. Development of the lung. Cell Tissue Res. 2017;367(3):427-444. [CrossRef]

- Kimura S, Hara Y, Pineau T, et al. The T/ebp null mouse: thyroid-specific enhancer-binding protein is essential for the organogenesis of the thyroid, lung, ventral forebrain, and pituitary. Genes Dev. 1996;10(1):60-69. [CrossRef]

- Mucenski ML, Wert SE, Nation JM, et al. β-Catenin is required for specification of proximal/distal cell fate during lung morphogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(41):40231-40238. [CrossRef]

- Goss AM, Tian Y, Tsukiyama T, et al. Wnt2/2b and beta-catenin signaling are necessary and sufficient to specify lung progenitors in the foregut. Dev Cell. 2009;17(2):290-298. [CrossRef]

- Sekine K, Ohuchi H, Fujiwara M, et al. Fgf10 is essential for limb and lung formation [published correction appears in Nat Genet. 2019;51(5):921. doi: 10.1038/s41588-019-0396-9]. Nat Genet. 1999;21(1):138-141. [CrossRef]

- Bellusci S, Grindley J, Emoto H, Itoh N, Hogan BL. Fibroblast growth factor 10 (FGF10) and branching morphogenesis in the embryonic mouse lung. Development. 1997;124(23):4867-4878. [CrossRef]

- Minoo P, Su G, Drum H, Bringas P, Kimura S. Defects in tracheoesophageal and lung morphogenesis in Nkx2.1(-/-) mouse embryos. Dev Biol. 1999;209(1):60-71. [CrossRef]

- Little DR, Lynch AM, Yan Y, Akiyama H, Kimura S, Chen J. Differential chromatin binding of the lung lineage transcription factor NKX2-1 resolves opposing murine alveolar cell fates in vivo. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):2509. [CrossRef]

- Herriges M, Morrisey EE. Lung development: orchestrating the generation and regeneration of a complex organ. Development. 2014;141(3):502-513. [CrossRef]

- Weaver M, Yingling JM, Dunn NR, Bellusci S, Hogan BL. Bmp signaling regulates proximal-distal differentiation of endoderm in mouse lung development. Development. 1999;126(18):4005-4015. [CrossRef]

- Park KS, Wells JM, Zorn AM, Wert SE, Whitsett JA. Sox17 influences the differentiation of respiratory epithelial cells. Dev Biol. 2006;294(1):192-202. [CrossRef]

- Lange AW, Haitchi HM, LeCras TD, et al. Sox17 is required for normal pulmonary vascular morphogenesis. Dev Biol. 2014;387(1):109-120. [CrossRef]

- Wan H, Kaestner KH, Ang SL, et al. Foxa2 regulates alveolarization and goblet cell hyperplasia. Development. 2004;131(4):953-964. [CrossRef]

- De Moerlooze L, Spencer-Dene B, Revest JM, et al. An important role for the IIIb isoform of fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 (FGFR2) in mesenchymal-epithelial signalling during mouse organogenesis. Development. 2000;127(3):483-492. [CrossRef]

- Mori M, Furuhashi K, Danielsson JA, et al. Generation of functional lungs via conditional blastocyst complementation using pluripotent stem cells. Nat Med. 2019;25(11):1691-1698. [CrossRef]

- Kitahara A, Ran Q, Oda K, et al. Generation of lungs by blastocyst complementation in apneumic Fgf10-deficient mice. Cell Rep. 2020;31(6):107626. [CrossRef]

- Miura A, Sarmah H, Tanaka J, et al. Conditional blastocyst complementation of a defective Foxa2 lineage efficiently promotes the generation of the whole lung. Elife. 2023;12:e86105. [CrossRef]

- Wen B, Li E, Ustiyan V, et al. In vivo generation of lung and thyroid tissues from embryonic stem cells using blastocyst complementation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;203(4):471-483. [CrossRef]

- Wen B, Li E, Wang G, et al. CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing allows generation of the mouse lung in a rat. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2024;210(2):167-177. [CrossRef]

- Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) and Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR). OPTN/SRTR 2022 Annual Data Report. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration; 2024. Accessed 12/4/2024.

- Stark K, Vainio S, Vassileva G, McMahon AP. Epithelial transformation of metanephric mesenchyme in the developing kidney regulated by Wnt-4. Nature. 1994;372(6507):679-683. [CrossRef]

- Reidy KJ, Rosenblum ND. Cell and molecular biology of kidney development. Semin Nephrol. 2009;29(4):321-337. [CrossRef]

- Torres M, Gómez-Pardo E, Dressler GR, Gruss P. Pax-2 controls multiple steps of urogenital development. Development. 1995;121(12):4057-4065. [CrossRef]

- Xu, PX., Adams, J., Peters, H. et al. Eya1-deficient mice lack ears and kidneys and show abnormal apoptosis of organ primordia. Nat Genet. 1999;23,113-117. [CrossRef]

- Nishinakamura R, Matsumoto Y, Nakao K, et al. Murine homolog of SALL1 is essential for ureteric bud invasion in kidney development. Development. 2001;128(16):3105-3115. [CrossRef]

- Kreidberg JA, Sariola H, Loring JM, et al. WT-1 is required for early kidney development. Cell. 1993;74:679-691. [CrossRef]

- Xu PX, Zheng W, Huang L, et al. Six1 is required for the early organogenesis of mammalian kidney. Development. 2003;130(14):3085-3094. [CrossRef]

- Usui J, Kobayashi T, Yamaguchi T, et al. Generation of kidney from pluripotent stem cells via blastocyst complementation. Am J Pathol. 2012;180(6):2417-2426. [CrossRef]

- Goto T, Hara H, Sanbo M, et al. Generation of pluripotent stem cell-derived mouse kidneys in Sall1-targeted anephric rats. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):451. [CrossRef]

- Wang J, Xie W, Li N, et al. Generation of a humanized mesonephros in pigs from induced pluripotent stem cells via embryo complementation. Cell Stem Cell. 2023;30(9):1235-1245.e6. [CrossRef]

- OPTN/SRTR 2021 Annual Data Report: Pancreas,; Kandaswamy, Raja et al., Amer J Transplant. Volume 23, Issue 2, S121-S177.

- Henry BM, Skinningsrud B, Saganiak K, et al. Development of the human pancreas and its vasculature - An integrated review covering anatomical, embryological, histological, and molecular aspects. Ann Anat. 2019;221:115-124. [CrossRef]

- Adda G, Hannoun L, Loygue J. Development of the human pancreas: variations and pathology. A tentative classification. Anat Clin. 1984;5:275-283. [CrossRef]

- Pan FC, Brissova M. Pancreas development in humans. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2014;21(2):77-82. [CrossRef]

- Jennings RE, Berry AA, Strutt JP, Gerrard DT, Hanley NA. Human pancreas development. Development. 2015;142(18):3126-3137. [CrossRef]

- Stoffers DA, Zinkin NT, Stanojevic V, Clarke WL, Habener JF. Pancreatic agenesis attributable to a single nucleotide deletion in the human IPF1 gene coding sequence. Nat Genet. 1997;15(1):106-110. [CrossRef]

- Weedon MN, Cebola I, Patch A-M, et al. Recessive mutations in a distal PTF1A enhancer cause isolated pancreatic agenesis. Nat Genet. 2014;46(1):61-64. [CrossRef]

- Amara D, Hansen KS, Kupiec-Weglinski SA, et al. Pancreas transplantation for type 2 diabetes: A systematic review, critical gaps in the literature, and a path forward. Transplantation. 2022;106(10):1916-1934. [CrossRef]

- Groth CG, Korsgren O, Tibell A, et al. Transplantation of porcine fetal pancreas to diabetic patients. Lancet. 1994;344(8934):1402-1404. [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi T, Yamaguchi T, Hamanaka S, et al. Generation of rat pancreas in mouse by interspecific blastocyst injection of pluripotent stem cells. Cell. 2010;142(5):787-799. [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi T, Sato H, Kato-Itoh M, et al. Interspecies organogenesis generates autologous functional islets. Nature. 2017;542(7640):191-196. [CrossRef]

- Matsunari H, Nagashima H, Watanabe M, et al. Blastocyst complementation generates exogenic pancreas in vivo in apancreatic cloned pigs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(12):4557-4562. [CrossRef]

- OPTN/SRTR 2022 Annual Data Report: Heart. Colvin, Monica M. et al. Amer J Transplant. Volume 24, Issue 2, S305-S393.

- Buijtendijk MFJ, Barnett P, van den Hoff MJB. Development of the human heart. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2020;184(1):7-22. [CrossRef]

- Harris IS, Black BL. Development of the endocardium. Pediatr Cardiol. 2010;31(3):391-399. [CrossRef]

- Puri MC, Partanen J, Rossant J, Bernstein A. Interaction of the TEK and TIE receptor tyrosine kinases during cardiovascular development. Development. 1999;126(20):4569-4580. [CrossRef]

- Wu SM, Fujiwara Y, Cibulsky SM, et al. Developmental origin of a bipotential myocardial and smooth muscle cell precursor in the mammalian heart. Cell. 2006;127(6):1137-1150. [CrossRef]

- Lyons I, Parsons LM, Hartley L, et al. Myogenic and morphogenetic defects in the heart tubes of murine embryos lacking the homeo box gene Nkx2-5. Genes Dev. 1995;9(13):1654-1666.

- Grépin C, Robitaille L, Antakly T, Nemer M. Inhibition of transcription factor GATA-4 expression blocks in vitro cardiac muscle differentiation. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15(8):4095-4102. [CrossRef]

- Charron F, Paradis P, Bronchain O, Nemer G, Nemer M. Cooperative interaction between GATA-4 and GATA-6 regulates myocardial gene expression. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19(6):4355-4365. [CrossRef]

- Saga Y, Miyagawa-Tomita S, Takagi A, Kitajima S, Miyazaki Ji, Inoue T. MesP1 is expressed in the heart precursor cells and required for the formation of a single heart tube. Development. 1999;126(15):3437-3447. [CrossRef]

- Kitajima S, Takagi A, Inoue T, Saga Y. MesP1 and MesP2 are essential for the development of cardiac mesoderm. Development. 2000;127(15):3215-3226. [CrossRef]

- Coppiello G, Barlabé P, Moya-Jódar M, et al. Generation of heart and vascular system in rodents by blastocyst complementation. Dev Cell. 2023;58(24):2881-2895.e7. [CrossRef]

- Das S, Koyano-Nakagawa N, Gafni O, et al. Generation of human endothelium in pig embryos deficient in ETV2. Nat Biotechnol. 2020;38(3):297-302. [CrossRef]

- Wyne KL, Nair L, Schneiderman CP, et al. Hypothyroidism prevalence in the United States: A retrospective study combining national health and nutrition examination survey and claims data, 2009-2019. J Endocr Soc. 2022;7(1):bvac172. [CrossRef]

- Somwaru LL, Arnold AM, Joshi N, Fried LP, Cappola AR. High frequency of and factors associated with thyroid hormone over-replacement and under-replacement in men and women aged 65 and over. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(4):1342-1345. [CrossRef]

- Flynn RW, Bonellie SR, Jung RT, et al. Serum thyroid-stimulating hormone concentration and morbidity from cardiovascular disease and fractures in patients on long-term thyroxine therapy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(1):186-193. [CrossRef]

- Thayakaran R, Adderley NJ, Sainsbury C, et al. Thyroid replacement therapy, thyroid stimulating hormone concentrations, and long term health outcomes in patients with hypothyroidism: longitudinal study. BMJ. 2019;366:l4892. [CrossRef]

- Romitti M, Costagliola S. Progress toward and challenges remaining for thyroid tissue regeneration. Endocrinology. 2023;164(10):bqad136. [CrossRef]

- Rosen RD, Sapra A. Embryology, Thyroid. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; May 1, 2023.

- Policeni BA, Smoker WR, Reede DL. Anatomy and embryology of the thyroid and parathyroid glands. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2012;33(2):104-114. [CrossRef]

- Nilsson M, Williams D. On the origin of cells and derivation of thyroid cancer: C Cell Story Revisited. Eur Thyroid J. 2016;5(2):79-93. [CrossRef]

- Nilsson M, Fagman H. Mechanisms of thyroid development and dysgenesis: an analysis based on developmental stages and concurrent embryonic anatomy. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2013;106:123-170. [CrossRef]

- Antonica, F., Kasprzyk, D., Opitz, R. et al. Generation of functional thyroid from embryonic stem cells. Nature. 2012;491(7422):66-71. [CrossRef]

- Parlato R, Rosica A, Rodriguez-Mallon A, et al. An integrated regulatory network controlling survival and migration in thyroid organogenesis. Dev Biol. 2004;276(2):464-475. [CrossRef]

- Ran Q, Zhou Q, Oda K, et al. Generation of thyroid tissues From embryonic stem cells via blastocyst complementation in vivo. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2020;11:609697. [CrossRef]

- Peissig K, Condie BG, Manley NR. Embryology of the parathyroid glands. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2018;47(4):733-742. [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo M, Zilhão R, Neves H. Thymus inception: Molecular network in the early stages of thymus organogenesis. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(16):5765. [CrossRef]

- Gordon J, Manley NR. Mechanisms of thymus organogenesis and morphogenesis. Development. 2011;138(18):3865-3878. [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki, K., Kubara, K., Ishii, S. et al. In vitro and in vivo functions of T cells produced in complemented thymi of chimeric mice generated by blastocyst complementation. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):3242. [CrossRef]

- Kano M, Mizuno N, Sato H, et al. Functional calcium-responsive parathyroid glands generated using single-step blastocyst complementation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2023;120(28):e2216564120. [CrossRef]

- De Los Angeles A, Pho N, Redmond DE Jr. Generating human organs via interspecies chimera formation: Advances and barriers. Yale J Biol Med. 2018;91(3):333-342.

- Maeng G, Das S, Greising SM, et al. Humanized skeletal muscle in MYF5/MYOD/MYF6-null pig embryos. Nat Biomed Eng. 2021;5(8):805-814. [CrossRef]

- Huang K, Zhu Y, Ma Y, et al. BMI1 enables interspecies chimerism with human pluripotent stem cells. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):4649. [CrossRef]

- Wang X, Li T, Cui T, et al. Human embryonic stem cells contribute to embryonic and extraembryonic lineages in mouse embryos upon inhibition of apoptosis. Cell Res. 2018;28(1):126-129. [CrossRef]

- Zheng C, Hu Y, Sakurai M, et al. Cell competition constitutes a barrier for interspecies chimerism. Nature. 2021;592(7853):272-276. [CrossRef]

- Strell P, Shetty A, Steer CJ, Low WC. Interspecies chimeric barriers for generating exogenic organs and cells for transplantation. Cell Transplant. 2022;31. [CrossRef]

- Cohen MA, Markoulaki S, Jaenisch R. Matched developmental timing of donor cells with the host Is crucial for chimera formation. Stem Cell Reports. 2018;10(5):1445-1452. [CrossRef]

- Cohen MA, Wert JK, Goldman J, et al. Human neural crest cells contribute to coat pigmentation in interspecies chimeras after in utero injection into mouse embryos. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(6):1570-1575. [CrossRef]

- Mascetti, VL, Pedersen RA. Contributions of mammalian chimeras to pluripotent stem cell research. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;19(2):163-175. [CrossRef]

- Mascetti VL, Pedersen RA. Human-mouse chimerism validates human stem cell pluripotency. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;18(1):67-72. [CrossRef]

- Weinberger L, Ayyash M, Novershtern N, Hanna JH. Dynamic stem cell states: naive to primed pluripotency in rodents and humans. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2016;17(3):155-169. [CrossRef]

- Nichols J, Smith A. Naive and primed pluripotent states. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4(6):487-492. [CrossRef]

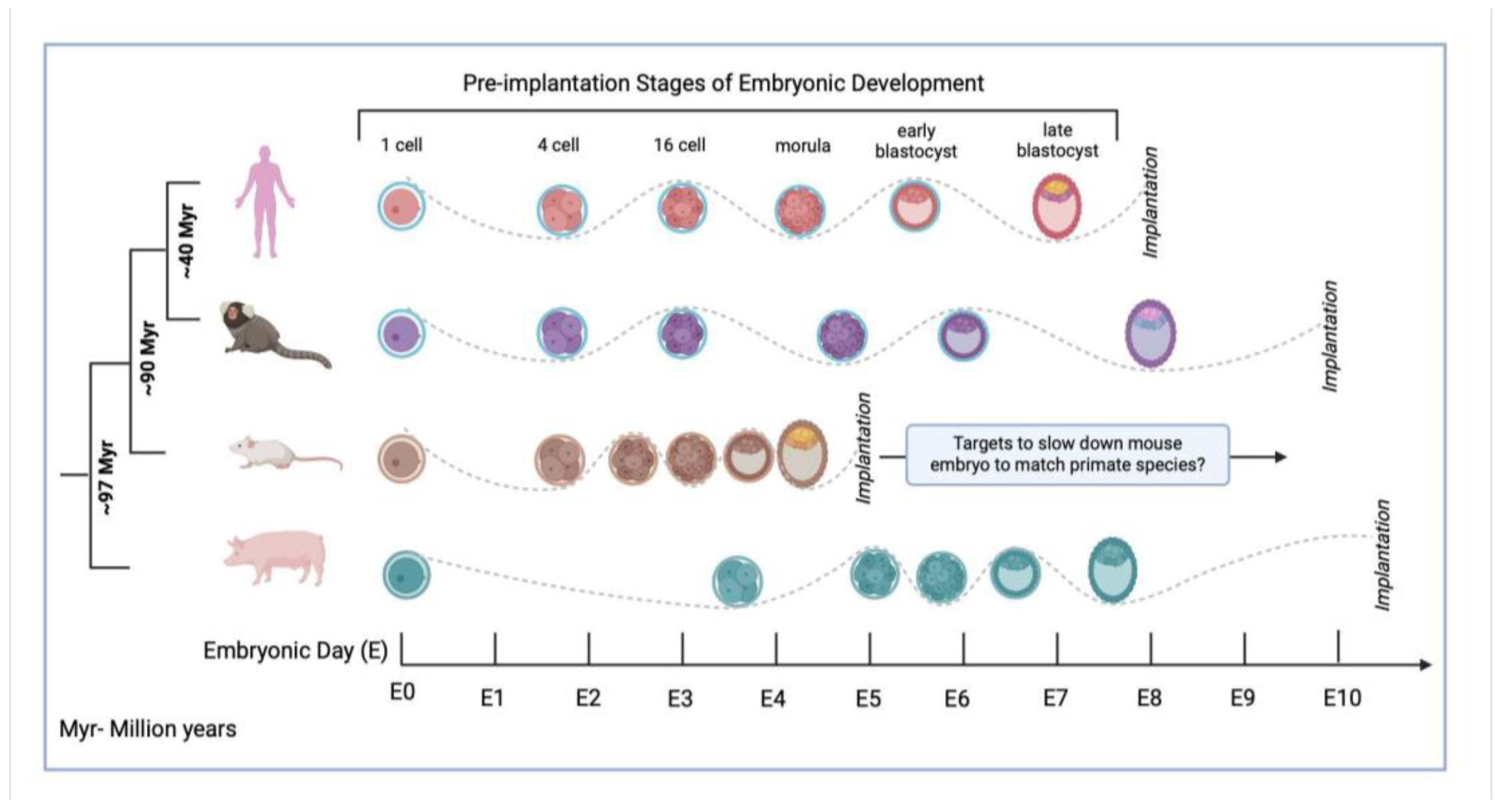

- Shetty A, Lim S, Strell P, et al. In silico stage-matching of human, marmoset, mouse, and pig embryos to enhance organ development through interspecies chimerism. Cell Transplant. 2023;32. [CrossRef]

- Stirparo GG, Boroviak T, Guo G, et al. Erratum: Correction: Integrated analysis of single-cell embryo data yields a unified transcriptome signature for the human pre-implantation epiblast (doi:10.1242/dev.158501) Development. 2018;145(15):dev169672). [CrossRef]

- Xue Z, Huang K, Cai C, et al. Genetic programs in human and mouse early embryos revealed by single-cell RNA sequencing. Nature. 2013;500(7464):593-597. [CrossRef]

- Deng Q, Ramsköld D, Reinius B, Sandberg R. Single-cell RNA-seq reveals dynamic, random monoallelic gene expression in mammalian cells. Science. 2014;343(6167):193-196. [CrossRef]

- Boroviak T, Stirparo GG, Dietmann S, et al. Single cell transcriptome analysis of human, marmoset and mouse embryos reveals common and divergent features of preimplantation development. Development. 2018;145(21):dev167833. [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Ibeas, P, Sang F, Zhu Q, et al. Pluripotency and X chromosome dynamics revealed in pig pre-gastrulating embryos by single cell analysis. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):500. [CrossRef]

- Fu R, Yu D, Ren J, et al. Domesticated cynomolgus monkey embryonic stem cells allow the generation of neonatal interspecies chimeric pigs. Protein Cell. 2020;11(2):97-107. [CrossRef]

- Miura H, Takahashi S, Shibata T, et al. Mapping replication timing domains genome wide in single mammalian cells with single-cell DNA replication sequencing. Nat Protoc. 2020;15(12):4058-4100. [CrossRef]

- Pope BD, Ruba T, Dileep V, et al. Topologically associating domains are stable units of replication-timing regulation. Nature. 2014;515 (7527):402-405. [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Mulia JC, Buckley Q, Sasaki T, et al. Dynamic changes in replication timing and gene expression during lineage specification of human pluripotent stem cells. Genome Res. 2015;25(8):1091-1103. [CrossRef]

- Ma J, Duan Z. Replication timing becomes intertwined with 3D genome organization. Cell. 2019;176(4):681-684. [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi T, Kato-Itoh M, Nakauchi H. Targeted organ generation using Mixl1-inducible mouse pluripotent stem cells in blastocyst complementation. Stem Cells Dev. 2015;24(2):182-189. [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto H, Eto T, Yamamoto M, et al. Development of blastocyst complementation technology without contributions to gametes and the brain. Exp Anim. 2019;68(3):361-370. [CrossRef]

| Organ | Species | Gene target | Function | Survival | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liver | Pig host, pig donor | H-hex KO | Of the 4 chimeric fetuses achieved in the first round of blastocyst complementation, 1 showed normal liver. In the second round, 3 further chimeric fetuses from 95 complemented blastocysts alive at cesarean | Full-term development, alive at time of cesarean | Matsunari et al, 2020 [21] |

| Liver | Pig host, pig donor, Mouse host, mouse donor |

H-hex KO | In mice: increased survival past the embryonically lethal stage in H-hex knockout, with retarded to normal growth when compared to age-matched wild-type embryos. High degrees of chimerism present in complemented embryos. In pigs: restoration of H-hex and AFP liver-protein expression in liver cells, with high donor eGFP+ signaling in liver tissue. |

Mice: E12.5 Pig: E25 |

Ruiz-Estevez et al, 2021 [22] |

| Liver | Pig host, pig donor | Conditional H-hex KO with FOXA3 promoter | Two rounds with each 2/120 healthy fetuses with all hepatocytes of donor origin. | Fetuses collected after 21 days | Simpson et al, 2024 [23] |

| Lung | Mouse host, mouse donor | Ctnnb, Fgfr2 KO | Pulmonary function tests (Resistance, compliance, elastance, methacholine challenge) showed non-significant differences between wild-type and Ctnnb-null and Fgfr2-null. GFP+ signals were very strong in epithelial tissue, but variable in mesenchymal and endothelial cells |

For Fgfr2-null: Day 80 For Ctnnb-null: Day 50 |

Mori et al, 2019 [39] |

| Lung | Mouse host, mouse donor | Fgf10 Ex1mut./ Ex3mut | Histologically and morphologically normal lungs compared to wildtype, cells were a mix of GFP+ve embryonic stem cells and host cells | 4 months | Kitahara et al, 2020 [40] |

| Lung | Mouse host, mouse donor | Foxa2 driven fgfr2 KO | No significant difference in pulmonary function test (airway resistance, frequency, tidal volume, expiratory flow at 50% expired tidal volume). | 4 weeks | Miura et al, 2023 [41] |

| Lung | Mouse host, mouse donor | NKx2-1 KO | Rescued lung and thyroid tissue, with embryonic stem cell-derived cells expressing similar gene expression and differentiation characteristics (such as surfactant production, T1alpha expression). | Death at birth for all Nkx2-1 homogenous knockout mice | Wen et al, 2020 [42] |

| Lung | Mouse host, rat donor | NKx2-1 KO | Rescued lung tissue, with 30% of all Nkx2-1 homozygous knockout mouse-rat chimeras demonstrating 98.5% cell contribution from mouse embryonic stem cells. RNAseq showed normal gene expression profiles and cell signaling pathways in the chimeras. | Embryos harvested at E20.5 | Wen et al, 2024 [43] |

| Kidney | Mouse host, Mouse donor | Sall1 KO | Histologically and morphologically normal kidneys. Both ESC and iPSC-complemented mice showed high contribution in kidney epithelia (except collection tubules). Stromal elements (vessels, nerves) were a mix of host and donor cells. | No survival of Sall1-/- mice to adulthood | Usui et al, 2012 [52] |

| Kidney | Rat host, mouse donor | Sall1 KO | Morphologically rescued kidneys. High mouse contribution in metanephric mesenchymal cells but collecting tubules and blood vessels showed a mix of donor mouse and host rat cells. Successful connection between ureter and bladder. Decreased kidney size compared to control rats, but similar to wildtype mice. Size of glomeruli like control rats, number of glomeruli similar to control mice. | No survival of Sall1-/- mice to adulthood | Goto et al, 2019 [53] |

| Kidney | Pig host, pig donor | Sall1 KO | First attempt did not result in successful kidney development. Second attempt led to 1 chimera from 97 complemented blastocysts with histologically and morphologically normal kidney. | Fetus, Day 43 | Matsunari et al, 2020 [21] |

| Kidney | Pig host, human donor | Six1, Sall1 KO | Histologically similar mesonephros to wildtype embryos, and similar mesonephric tubule density. DsRed-labelled human-derived contribution was around 50-65% for all mesonephric cells, with over 60% in mesonephric tubules, but under 40% in mesenchyme. | Gestation was terminated at E25 or E28 | Wang et al, 2023 [54] |

| Pancreas | Mouse host, mouse donor Mouse host, rat donor |

PDX1 KO | Mouse-Mouse chimeras: Functional, histologically and morphologically normal pancreas. Pancreatic islets, ducts and exocrine tissue entirely derived from mouse donor cells in PDX1 -/- mice. When transplanted in diabetic mice, normal serum glucose and normal response to glucose tolerance test Mouse-rat chimeras: Pancreatic epithelia was fully composed of rat-derived cells. Of the 2 chimeras that reached full maturity, histological and morphological analysis was normal, with normal serum glucose levels and glucose tolerance testing. |

PDx1-/-Mouse-Mouse: 60 days post transplantation of iPSC-derived pancreas into diabetic mice PDX1 -/- Mouse-Rat: 8 weeks (only 2/10 survived to adulthood) |

Kobayashi et al, 2010 [64] |

| Pancreas | Pig host, pig donor | Introduction of Pdx1-Hes1 transgene | Histologically normal pancreas, almost all pancreatic cells derived from donor cells. Normal serum glucose levels, with 1 chimeric pig showing normal oral glucose tolerance test. | Minimum of 12 months | Matsunari et al, 2013 [66] |

| Pancreas | Rat host, mouse donor | Pdx1 KO | Morphologically normal pancreas, homogeneously expressing mouse-derived cells. Supporting tissue did demonstrate host rat-derived cells. Mouse-derived pancreatic islets were then re-transplanted in mice, with normal glycemic levels during follow up. Islet cells showed successful hormone secretion with insulin, glucagon, somatostatin expression. | Normal glycemic levels for up to 370 days following transplantation of pancreas derived from blastocyst complementation | Yamaguchi et al, 2017 [65] |

| Pancreas | Pig host, pig donor | Pdx1 KO | Histologically, morphologically normal pancreas in 2/4 chimeric animals. In pigs with successful pancreatic rescue, high levels of chimerism could be shown. | Full-term fetuses | Matsunari et al, 2020 [21] |

| Heart | Mouse host, mouse donor Mouse host, rat donor |

Nkx2.5-Cre and Tie2-Cre dependent DTA (diptheria toxin A) | Mouse-mouse chimera: Donor-derived endothelial cells and cardiomyocytes, with normal functioning hearts in 8 chimeras. No signs of fibrosis. In 3 chimeras, cardiomyocyte area and vascular density comparable to control. Rat-mouse chimera: Heart complementation with almost complete donor derived cardiomyocytes in Nkx2.5-Cre mice at E10.5. Unsuccessful heart or vascular system complementation in Nkx2.5-Cre;Tie-2Cre mice in later developmental stages (E11.5, E14.5). |

Mouse-mouse chimera: up to adulthood Rat-mouse chimera: E10.5 (Nkx2.5-Cre), E10.5, E11.5, E14.5 (Nkx2.5-Cre;Tie2-Cre) |

Cappiello et al, 2023 [77] |

| Thyroid | Mouse host, mouse donor | Fgf10 Ex1mut./ Ex3mut | Morphologically and histologically normal thyroid in neonatal and adult mice. GFP expression was 86.4% +/- 7.9% in thyroid follicular cells. GFP expression did not dominate in C-cells, vasculature and connective tissue. T3 and T4 levels comparable to wildtype. | adulthood | Ran et al, 2020 [90] |

| Thyroid | Mouse host, mouse donor | NKx2-1 KO | Rescued thyroid tissue in chimeric mice, with efficient donor contribution to thyrocyte progenitor cells. | E17.5 | Wen et al, 2021 [42] |

| Thymus | Mouse host, mouse donor | FOXN1 KO | Rescued thymus in 11 mice. In 2 mice examined, 98 and 96.9% of thymic epithelial cells were donor derived. Compared to normal mice: no significant difference in number of peripheral T cells, or gene-expression profile. In splenic T cells, no significant difference in CD4+ or CD8+ T cell proliferation or production of IFN gamma, IL-2, Granzyme B with anti-CD3 stimulation. Under anti-PDL1 treatment: suppression of MC38 tumor growth and increased IFNgamma production and T cell activation (via decrease in PD1 expression). | Up to 42 weeks | Yamazaki et al, 2022 [94] |

| Thymus | Mouse host, mouse donor | Foxa2 -driven Fgfr2 KO | Rescued thymic phenotype. Chimerism in thymus: average 92.4% (SD 5.1) in thymic epithelium, average 52.9% (SD 20) in thymic mesenchyme. | Up to 4 weeks | Miura et al, 2023 [41] |

| Parathyroid | Mouse host, mouse donor Rat host, mouse donor |

GCM2 KO |

Mouse-mouse: histologically normal parathyroids. GFP donor-derived signal was 94.6% in chief cells, 65,2% in endothelial cells and 45.6% in mesenchymal cells. Function: compared to control mice-similar plasma Calcium levels, basal PTH levels and PTH stimulation response. Gene expression level: Compared to control mice-increased GATA3, GCM2, similar levels of Mafb, Casr, PTH. Rat-mouse: rescued parathyroid phenotype, successful expression of transcription factors necessary for further development and PTH. |

Mouse-mouse: adulthood Rat-mouse: death soon after birth |

Kano et al, 2023 [95] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).