Introduction

This paper explores aspects of mountain entrepreneurship in European countries that report data on mountain regions to Eurostat: Austria, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czechia, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, and Sweden. The statistical analysis focuses on 2021, forming the basis for other related analyses.

Mountain entrepreneurship, spanning all economic sectors—primary, secondary, and tertiary—is especially critical within today’s shifting geopolitical and socio-economic landscape. Mountain regions globally face an increasing demand for economic resources, with development predominantly supported by small and medium enterprises (SMEs). In this context, entrepreneurs serve as key agents of change within mountain communities. Given the relatively high rate of business dissolution reported by Eurostat in these areas, mountain entrepreneurs are particularly attuned to innovations and new opportunities within their communities. Development strategies should aim to create a supportive environment that enhances entrepreneurs’ ability to operate effectively in mountain regions (Mayer and Meili 2016).

Amid intense territorial competition to attract investment, mountain regions are compelled to identify new, often external, resources to diversify their economies and ensure sustainable development. Some researchers view mountain regions as less attractive due to their accessibility challenges, while others argue that geographic factors (e.g., alpine areas bordering multiple countries) and governmental roles can enhance investment appeal. For instance, the attractiveness of the six Alpine provinces can be attributed to four main factors: the role of local government, proximity to developed neighboring countries, nearness to Italy’s industrialized Padana region, and strong market potential. Musolino and Silvetti (2020) suggest that although peripherality and limited accessibility influence perceptions, these factors do not significantly detract from the overall appeal of these regions. Strengthening connectivity and cooperation with neighboring areas, alongside targeted territorial marketing strategies that emphasize shared cultural and linguistic identities, are vital for the sustainable development of mountain areas (Musolino and Silvetti 2020).

In contrast to other European mountain regions, the European Alps have experienced a reversal in out-migration. The arrival of “new highlanders” from urban and peri-urban areas to settle and work in mountain regions has revitalized these communities. Entrepreneurship plays a crucial role for these new residents, with all economic sectors, including the quaternary, well represented among Alpine mountain dwellers (Mayer and Meili 2016).

The Balkans present a different model of mountain development, predominantly focused on limited types of tourism activities. Lukić et al. (2013) argue that while tourism revenue is valuable, sustainable mountain development must also prioritize nature conservation, local products, and community welfare. In this context, entrepreneurial initiatives are highly encouraged, provided they align with sustainable development principles (Lukić et al. 2013).

The Carpathians offer another unique perspective. According to Dej and Micek (2013), companies in the Carpathians hold substantial influence within local labor markets but vary significantly in terms of local impact and development levels. Similar to other European mountain ranges, small and medium enterprises (SMEs) play a critical role in fostering sustainability within Carpathian communities (Dej and Micek 2013).

In Romania, mountain areas face ongoing challenges related to depopulation, youth migration, declining livestock, low incomes, and reduced living standards. Addressing these issues requires a renewed vision and strategy to ensure sustainable mountain development. Strengthening the mountain economy can stabilize rural populations, enhance quality of life, maximize natural and human resources, preserve cultural heritage, and protect biodiversity and the environment (Popescu et al. 2022).

A key aspect of mountain regions lies in the “mountain product.” Achieving sustainability in agriculture requires collaboration across economic sectors, making the mountain product a concrete element of local, regional, and European development. Against a backdrop of societal concerns in Romania and across the EU, EU initiatives focused on mountain products, along with national legislative and organizational efforts, have complemented the proactive outlook of some mountain farmers and entrepreneurs. These efforts aim to sustain a critical economic activity that provides healthy food for millions (Rey 2020).

Materials and Research Method

This study focuses on the key aspects of entrepreneurial development within European mountain regions, underscoring the importance of proactive interventions to mitigate territorial and socio-economic challenges.

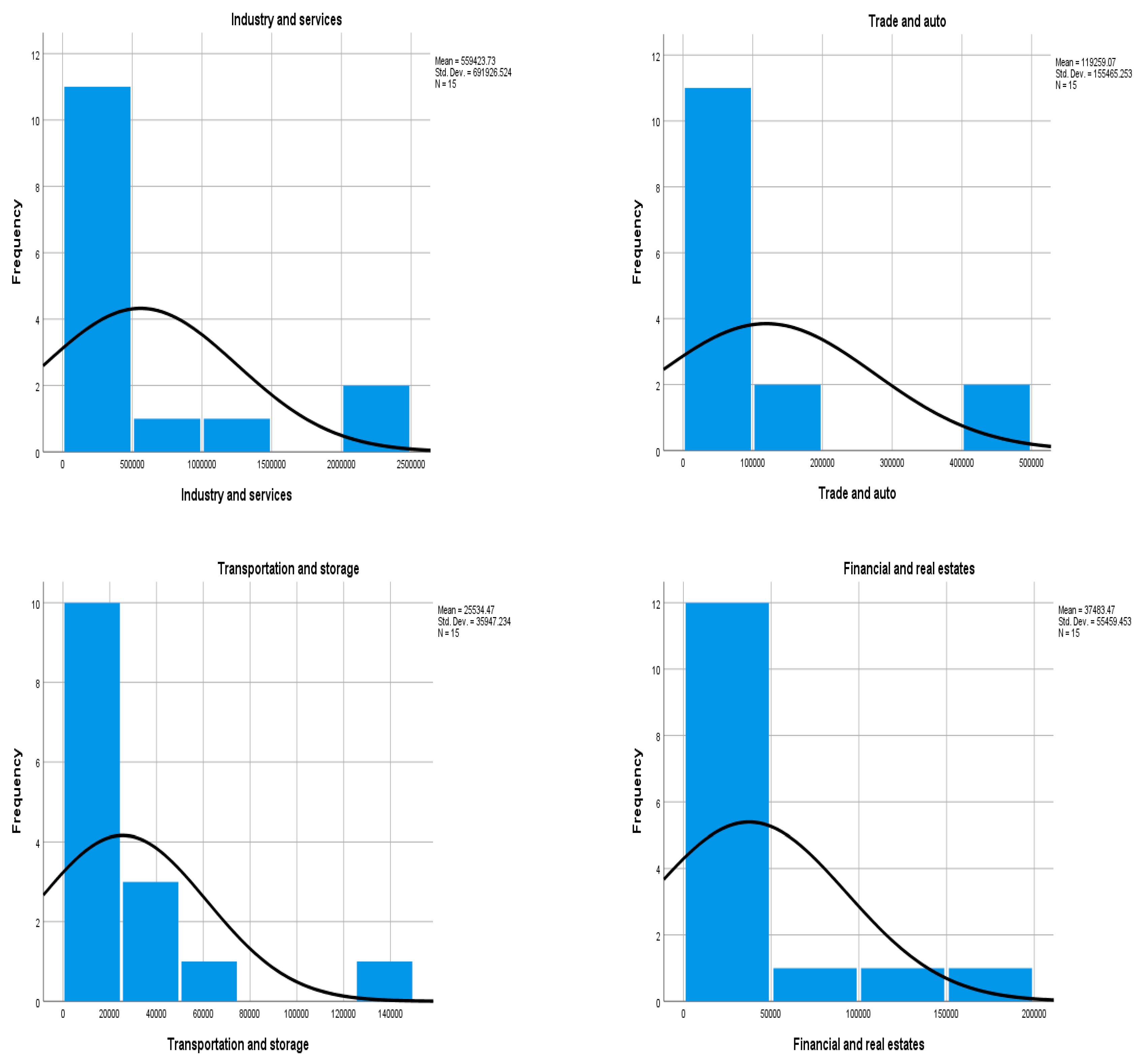

Research across the analyzed countries centers on active companies within specified sectors, with a primary focus on frequency statistics and neural network analysis. All data used in this paper were simulated based on information from the Eurostat database. Histograms were generated based on mean values, standard deviation, and ordinal ranking, representing each country within its respective support sector. Frequency statistics provided insights into the establishment of new businesses in mountain areas, with particular emphasis on the critical role of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in economic growth.

The frequency analysis yielded varying values across sectors, specifically for Industry and Services, Trade and Automotive, Transportation and Warehousing, and Finance and Real Estate Development. Key statistics for these sectors are as follows (in sector order):

- -

Mean: 559,423.73; 119,259.07; 25,534.47; 37,483.47

- -

Standard Error of Mean: 178,654.660; 40,140.956; 9,281.536; 14,319.569

- -

Median: 299,930; 56,801; 10,289; 14,653

- -

Skewness: 1.918; 2.034; 2.847; 1.943

- -

Standard Error of Skewness: 0.580 (uniform across all sectors)

- -

Kurtosis: 2.619; 3.161; 9.108; 2.648

- -

Standard Error of Kurtosis: 1.121 (uniform across all sectors)

- -

Range: 2,186,225; 495,931; 143,011; 177,518

- -

Minimum: 14,518; 1,718; 548; 1,208

- -

Maximum: 2,200,743; 497,649; 143,559; 178,726

- -

Sum: 8,391,356; 1,788,886; 383,017; 562,252

- -

50th Percentile: 299,930; 56,801; 10,289; 14,653

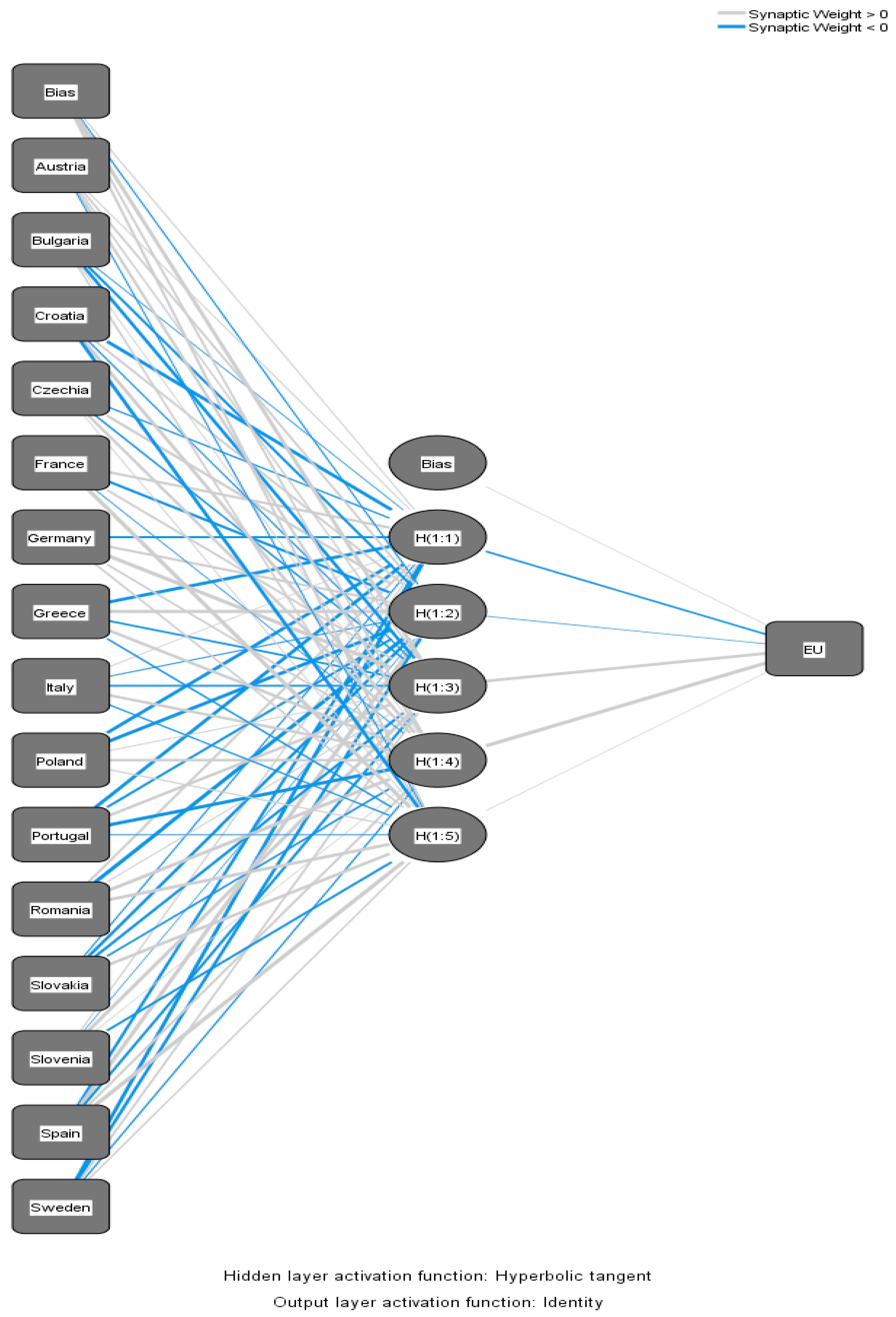

For the neural network analysis, the multilayer perceptron (MLP) method was employed to address the data’s inherent entropy and non-linearity (Cybenko, 1989). The analysis used a triadic model with the following dependent variables: countries (H(1:1)), economic sectors (Industry and Services) (H(1:2)), and support sectors (Commerce and Automotive (H(1:3)), Transport and Storage (H(1:4)), and Finance and Real Estate Development (H(1:5)).

Fractal representations specific to each analyzed country were developed to capture general trends within each national mountain region. These fractal simulations, generated using an AI image tool (

www.deepai.org), provide visual insights into the unique characteristics and trends of mountain entrepreneurship across different European countries.

Results and Discussion

a. Mountain Entrepreneurship in European Countries: Frequency Statistics

Mountain entrepreneurship within the European industry and services sectors exhibits a non-linear trend, with notable growth in recent years (see

Figure 1). When examining the secondary and tertiary economic sectors across the EU, several countries show relatively low contributions (below 5%) to the overall EU mountain entrepreneurship sector, including Austria (3.72%), Bulgaria (2.93%), Croatia (0.70%), Czechia (3.57%), Germany (3.22%), Poland (1.98%), Portugal (3.41%), Romania (3.65%), Slovakia (3.93%), and Slovenia (1.85%).

Conversely, other countries demonstrate higher percentages at the EU level, with France at 12.48%, Greece at 7.02%, Italy at 25.14%, and Spain at 26.23%.

In the support sectors, a similar pattern emerges, though there are notable variations among some emerging economies. For example, in the Trade and Automotive industry, Bulgaria contributes 4.50% and Romania 4.81%. In the Transport and Storage sector, Romania stands out with 8.09%.

Countries with a strong tradition of mountain entrepreneurship in Industry and Services also exhibit high values in support sectors. For example:

- -

Trade and Automotive industry: France (8.72%), Greece (8.88%), Italy (27.82%), and Spain (26.47%)

- -

Transport and Storage: France (9.19%), Greece (10.92%), Italy (13.12%), and Spain (37.48%)

- -

Financial and Real Estate sector: France (16.56%), Italy (25.93%), and Spain (31.79%)

As can be seen in the presented histograms, the asymptotes are oriented to the left, understanding that the economic sectors Industry and services support the development of the mountain areas of the EU, mountain entrepreneurship being predominant in ensuring sustainability. The asymptotes with unit values of frequency above 4, noted in the histograms Industry and services and Financial sector and real estate development, present these sectors as being of high importance for EU countries. The rise of these sectors was achieved on the basis of the technological infusion from the financial sector, before 2021 it presented deficiencies in development and spread in the mountain areas. The lack of adequate financial services for mountain entrepreneurs has led to the non-linearity of the general development of all economic sectors. This support sector still requires the development of financial instruments specific to mountain areas, which is why the authors believe that many of the EU mountain countries should ensure special attention to this sector.

b. Mountain Entrepreneurship in European Countries: Neural Network Analysis

The need for a deeper understanding of mountain entrepreneurship in the secondary and tertiary sectors has led to the application of neural network analysis. Eurostat data highlights the significant role of support sectors, which constitute a substantial portion of the Industry and Services sectors overall. Specifically, these support sectors represent approximately one-third of the total secondary and tertiary sectors across the EU, with percentages as follows: EU average - 32.58%, Austria - 24.49%, Bulgaria - 46.08%, Croatia - 26.08%, Czechia - 27.57%, France - 27.14%, Germany - 29.01%, Greece - 36.50%, Italy - 32.89%, Poland - 30.94%, Portugal - 27.37%, Romania - 41.94%, Slovakia - 25.31%, Slovenia - 22.02%, Spain - 36.16%, and Sweden - 23.93%.

The neural network model (see

Figure 2) illustrates a range of connections between these sectors. Strong interconnections are marked in gray (synaptic weight>0), while blue marks indicate very weak or non-existent links (synaptic weight<0). Key connections are observed in specific sectors:

- -

Commerce and Automotive Industry (H(1:3)): Strong connections appear in the mountain entrepreneurship of Germany, Portugal, Slovenia, and Sweden.

- -

Transport and Storage (H(1:4)): This sector shows heightened connections within the mountain regions of Austria, Croatia, Czechia, Greece, Italy, Poland, and Romania.

- -

Financial and Real Estate Development (H(1:5)): Stability and high interconnectivity are evident in the mountainous areas of Bulgaria, France, Slovakia, and Spain.

This neural network analysis aligns with frequency statistics, reinforcing the prominent roles of Greece and Italy in the Transport and Storage sector and of France and Spain in the Financial and Real Estate sector. The analysis validates existing trends within these countries, highlighting the need to adapt entrepreneurial policies in Industry and Services to better suit the unique needs of each mountain region.

b. European Mountain Entrepreneurship in Industry and Services: Fractal Analysis

The fractal analysis within this study provides a unique perspective on European mountain entrepreneurship, highlighting strengths and weaknesses across various EU countries. The analysis incorporates a comprehensive set of fractal images (see Figure 3 stored in the Zenodo database DOI:

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14026183), and draws on visual data from the early days of the Internet to the present.

Austria: This Alpine nation has developed a robust mountain infrastructure over the past 30 years, excelling in luxury winter tourism and setting a high standard for mountain entrepreneurship.

Part of the Balkan mountain region, Bulgaria’s focus on religious tourism has bolstered sustainability. However, underdeveloped infrastructure continues to challenge long-term growth.

As a bridge between northern and southern Europe, Croatia has seen significant investments in mountain infrastructure, becoming an increasingly popular mountain destination.

An emerging destination, the Czech Republic is known not only for its historical landmarks but also for balanced economic development in mountain plateau regions.

With a dense population in mountain areas and a rich tradition in mountain entrepreneurship, France remains a luxury mountain destination and serves as a model for other countries with both low- and high-altitude regions.

High mountain-area living costs and a strong industrial presence make Germany an example of maximum mountain sector development within the EU.

Known for its exotic character and synergy between mountain and maritime tourism, Greece ranks high for religious tourism with continually expanding infrastructure.

Like Austria, France, and Spain, Italy’s mountain entrepreneurship thrives at higher altitudes, with continuous infrastructure investment due to the challenging terrain. Italy remains a cornerstone of European tourism, with an emphasis on promoting mountain-specific products.

Following a model similar to the Czech Republic, Poland sustains low-altitude mountain entrepreneurship without a heavy focus on infrastructure development.

Experiencing rapid growth in mountain tourism linked to luxury coastal tourism, Portugal still requires substantial infrastructure investment.

Romania’s potential in high-altitude tourism remains hindered by limited infrastructure, impacting accessibility to scenic destinations.

Primarily visited by transit travelers, Slovakia’s infrastructure remains underdeveloped, which limits access to its picturesque mountain destinations.

Positioned between east and west Europe, Slovenia sees high transit traffic but has yet to fully develop its infrastructure. Nevertheless, its mountain sectors span a wide range of economic activities.

Popular with international tourists, Spain’s mountain tourism sector is densely developed and continues to grow, though infrastructure investment remains necessary, especially in medium- to high-altitude areas.

Primarily focused on winter tourism, Sweden’s mountain entrepreneurship is supported by expanding infrastructure, appealing to cold-weather enthusiasts year-round.

This fractal analysis highlights the varied trajectories and infrastructure needs of mountain entrepreneurship across Europe, offering insights for enhancing sustainable development in mountain regions.

Conclusion

The article underscores the significant role of mountain entrepreneurship within the secondary and tertiary sectors across EU countries that report data to Eurostat, revealing a positive, upward trend in these sectors.

The frequency analysis highlights the Financial and Real Estate Development sector as the most substantial contributor to sustainability among the secondary and tertiary sectors. These findings are reinforced by the neural network analysis, which categorizes each country into specific support sector development groups based on its unique strengths.

Fractal simulations further support these conclusions, illustrating key aspects of mountain entrepreneurship in each country studied. Together, these analyses reveal the diverse and valuable contributions of European nations to the broader landscape of global mountain entrepreneurship.

The study recommends each country as a model for specific dimensions of mountain entrepreneurship, with infrastructure investment identified as a continuous necessity to foster sustainable growth in mountain regions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.C. and M.C.; Data verification, B.C. and M.C.; Formal analysis, B.C. and M.C.; Research, B.C. and M.C.; Methodology, B.C.; Resources, B.C. and M.C.; Software, B.C. and M.C.; Validation, B.C. and M.C.; Visualization, B.C. and M.C.; Roles/Writing - original draft, B.C.; and Writing - review and editing, B.C. and M.C.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability

Data supporting fractal analysis conclusions from this study are available in Zenodo at

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14026183, reference number 14026183. These data were derived from the authors’ AI image generator processing :

www.deepai.org. Data supporting the results of this study are available in the article and its supplementary materials.

Conflict Of Interest Statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Use of AI in the Scientific Writing

During the development of this article, the authors used the AI image generator tool (

www.deepai.org) in order to obtain fractal images related to the mountain entrepreneurship of the analyzed countries. After using this service, the authors have reviewed and edited the content as necessary and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

References

- Cybenko, G. Approximation by superpositions of a sigmoidal function. Mathematics of Control, Signals, and Systems 1989, 2, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dej M, Micek G. 2013. Large Dominant Enterprises Versus Development of Rural Mountainous Areas: The Case of the Polish Carpathian Communes. In: Kozak J, Ostapowicz K, Bytnerowicz A, Wyżga B, editors. The Carpathians: Integrating Nature and Society Towards Sustainability. Heidelberg, Germany: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 513-529.

- Lukić T, Ćurčić N, Jovan R, Tatjana P, Armenski T. 2013. The Region of the Tara Mountain–Entrepreneurial Initiatives. European Researcher (5-4):1512-1524.

- Mayer H, Meili R. New highland entrepreneurs in the Swiss Alps. Mountain Research and Development 2016, 36, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musolino D, Silvetti A. Are mountain areas attractive for investments? The case of the Alpine provinces in Italy. European Countryside 2020, 12, 469–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu A, Dinu TA, Stoian E, Şerban V, Ciocan HN. 2022. Romania’s mountain areas-present and future in their way to a sustainable development. Scientific Papers Series Management, Economic Engineering in Agriculture and Rural Development 22(4).

- Rey, R. 2020. A vision of sustainable-mountain-development focused on the valorization of quality “mountain products”. The increasing importance of mountain areas in the post-covid-19 conjecture. Studia Universitatis Babeș-Bolyai Geographia 107-154.

- Eurostat. 2024. Business demography and high growth enterprises by NACE Rev. 2 activity and other typologies [urt_bd_hgn__custom_13540880].

-

https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/urt_bd_hgn__custom_13540880/default/table?lang=en.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).