1. Introduction

Low-grade gliomas (LGG) represent a significant challenge due to their subtle growth patterns and the difficulty of early and accurate detection of tumor progression. LGG account for approximately 15% of all gliomas, with an incidence rate of about 1 in 100,000. These tumors are most observed in adults in their 30s and 40s [

1]. LGG, classified as WHO grade 2 gliomas, constitute a considerable proportion of adult brain tumors and are known for their brain invasion and potential for malignant transformation with life expectancy of about 5–15 years [

1]. The predominant majority of LGG carry mutations in the IDH gene, which would make them susceptible to clinically proven IDH inhibitors [

2]. The incidence of LGGs transforming into higher-grade tumors has been reported to be as high as 72% [

3]. The prognosis of grade 2 IDH-mutant astrocytomas is only slightly better than grade 3, with median survival of 11 years compared to 9 years [

3,

4].

The current standard of care for treating LGG includes a multidisciplinary approach tailored to individual patient factors, such as tumor location, genetic markers, and patient age. Surgical resection is typically the initial treatment, with the goal of maximal safe removal of the tumor to alleviate symptoms and obtain tissue for histopathological and molecular analysis [

5]. Postoperative management protocols are guided by molecular markers such as IDH mutation and 1p/19q codeletion status, which have prognostic significance. For high-risk patients (e.g. age over 40, subtotal resection, or unfavorable molecular profile) adjuvant therapies are considered. Post-radiation chemotherapy is often recommended to improve progression-free and overall survival [

6]. Regardless of the treatment protocol and molecular profile, the clinical management of LGGs typically relies on regular monitoring by longitudinal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to detect progression. Traditionally, visual inspection by radiologists has been the clinical gold standard for assessing tumor growth over time. However, this method is inherently subjective and prone to inter-observer variability, often resulting in delayed detection of growth, which can impact patient outcomes [

7].

Traditionally, longitudinal studies of LGGs have been evaluated using visual inspection or 2D diameter measurements, which have been the standard technique for assessment according to the RANO criteria for many years [

8]. So far, volumetric measurements have not been widely used because traditional manual contouring methods are time-consuming and prone to high inter-user variability. Recent advances in artificial intelligence bring timely and accurate volumetric measurements within reach [

7,

9]. Recently, there has been a gradual, though slow, shift from 2D measurements to 3D/volumetric assessments of LGGs. Additionally, the most recent version of the RANO criteria, RANO 2.0 (introduced in 2023), now incorporates 2D, 3D, and volumetric measurements. It also allows for AI-based segmentation, with human supervision during the process [

10].

Here, we evaluate the efficacy of volumetric analysis using the MRIMath platform, including a FLAIR AI and human supervision using the Smart contouring system, in detecting tumor growth in LGG patients as compared to standard visual inspection. We study AI alone and AI combined with human review and approval. Previous studies have shown the benefits of volumetric analysis combined with the online change-of-point statistical method in detecting tumor growth significantly earlier than visual inspection [

11]. Fathallah-Shaykh et al. applied the computationally intensive method of non-negative matrix factorization to segment LGG [

7,

12]; here use an accurate and efficient AI that generates segmentations in seconds. We also evaluate the role of physician review in enhancing AI prediction accuracy. We hypothesize that AI with volumetric assessment allows for earlier detection of tumor growth than current clinical standard of radiological assessment.

For volumetric assessment, we apply the statistical change-of-point method to determine the first point of growth. The change-of-point method applies the same rigorous statistical standard to all patients and studies and determines if a current measurement is significantly different from all the measurements of the same patient [

7,

9].

2. Materials and Methods

Ethical Approval

The Institutional Review Board of the University of Alabama at Birmingham approved the research (IRB-150618007); waiver of informed consent was granted because the research involved no greater than minimal risk and no procedures for which written consent is normally required outside the research context.

Study Design and Patient Selection

The patients were seen at the neuro-oncology clinics of the University of Alabama at Birmingham between July 1, 2017, and May 14, 2018. The inclusion criteria were (1) pathological diagnosis of grade 2 oligodendroglioma (oligo), grade 2 astrocytoma (astro), or grade 2 mixed glioma in the brain excluding the pineal gland and (2) at least 4 MRI scans available for review either after the initial diagnosis or after the completion of chemotherapy with temozolomide (if applicable). The exclusion criteria were (1) treatment with radiation therapy after the initial diagnosis or (2) radiological reports indicating development of new enhancement without an increase in FLAIR signal. Patients treated by radiation therapy were excluded because radiation may confound the results by causing an independent increase in FLAIR signal. We excluded patients whose radiological reports described new enhancing nodules without an increase in FLAIR signal because they are easily detected by visual examination.

A total of 56 gliomas met the inclusion criteria, including 19 oligodendrogliomas, 26 astrocytomas and 11 mixed gliomas; only 2 patients received temozolomide. All of the oligos had the 1p/19q co-deletions except for 1 with a single deletion of 19q. At the time of retrospective review, 34/56 patients had been diagnosed with clinical progression (i.e. clinical progression group) while the remaining 22/56 were diagnosed as being clinically stable (clinically stable group) by visual comparison of the most recent MRI performed at the last clinic visit. We reviewed the records of 8 patients followed for an imaging abnormality without pathological diagnosis; 1 patient was excluded because of lack of follow-up information. All 7 imaging abnormality patients were considered clinically stable at the time of review of this study.

A total of 56 patients, including 19 oligodendrogliomas, 26 astrocytomas, and 11 mixed gliomas, met the inclusion criteria. The selection criteria required at least four MRI scans, excluding those who received radiation therapy post-diagnosis, to ensure consistency in the study population. The final dataset included 57 patients divided into three groups: clinical progression, clinically stable, and imaging abnormality (negative control group).

Time to Growth Detected by Standard Clinical Care

Different board-certified neuro-radiologists at the University of Alabama at Birmingham Hospital generated the radiological reports after evaluating each longitudinal MRI scan. We retrospectively calculated the time to growth detection from the impressions of the radiological reports of these patients.

Tumor Segmentation, Volume Calculation, and Physician Review

A total of 627 MRI scans were uploaded to the MRIMath platform, resized to 256x256 and segmented by the MRIMath Flair AI. Tumor volumes were calculated by applying the following equation:

where x, y, and z correspond to x-spacing, y-spacing, and spacing between slices, respectively.

AI segmentation results were reviewed by physicians Board-certified in radiology, neuro-oncology, radiation oncology, or neurosurgery by using the MRIMath Smart contouring platform to view and modify the contours as needed. Physician reviews served as the gold standard for evaluating the accuracy of both AI-generated manual segmentations.

Online Change-of-Point Detection

To detect a the first significant change in a series of longitudinal volumes, we apply the online change-of-point method to the AI-generated measurements with or without human review. To exclude FLAIR changes due to the evolution of post-surgical changes, the baseline volume in the longitudinal series was the first minimum after surgical resection. To identify an abrupt change of volume, we applied a change in the root-mean-square level at a minimum threshold of 500/(volume at baseline) and a minimum of 2 samples between change points. The number 500 corresponds to 5% of the rounded median of the baseline volume.

The change-of-point is a statistical technique used to identify points in a time series where the data’s properties, such as mean, variance, or distribution, change significantly [

13,

14]. These points, known as change points, indicate shifts in the underlying process generating the data. Detecting such changes is crucial in patient follow up and can help the physician to detect subtle changes of MR images. There are two primary approaches to change point detection

: the online method detects changes in points in real-time as new data becomes available, making it essential for applications requiring immediate detection and response. The offline method analyzes a complete dataset to identify any change points that have occurred. It’s often used in post hoc analyses where the entire data sequence is available [

15]. Here, we use the algorithms developed by Rebecca Killick and apply the online method, as it replicates clinical scenarios where the volumetric series includes only measurements taken before a specific date [

16].

3. Results

Reviewers and Time

The median time spent reviewing, revising and approving the AI segmentations was 1.18 minutes (lower quartile of 1.18 minutes and an upper quartile of 3.31), mean = 2.93 minutes, 95% CI: (2.32, 3.54).

Clinical Progression Group

In the clinical progression group, including the LGG patients whose last MRIs were interpreted as showing progression by the radiological reports, the results demonstrate that volumetric analysis that combines AI segmentation, human review, and the change-of-point method detects tumor growth significantly earlier than traditional visual inspection by radiologists (median of 21 months,

Table 1). Conversely, AI without human review also detects tumor growth earlier than visual inspection (median of 21 months), but with false negative and positive results (

Table 1) missed 3 out of 35 cases, and these misses were primarily associated with smaller tumors that were more challenging to detect and segment.

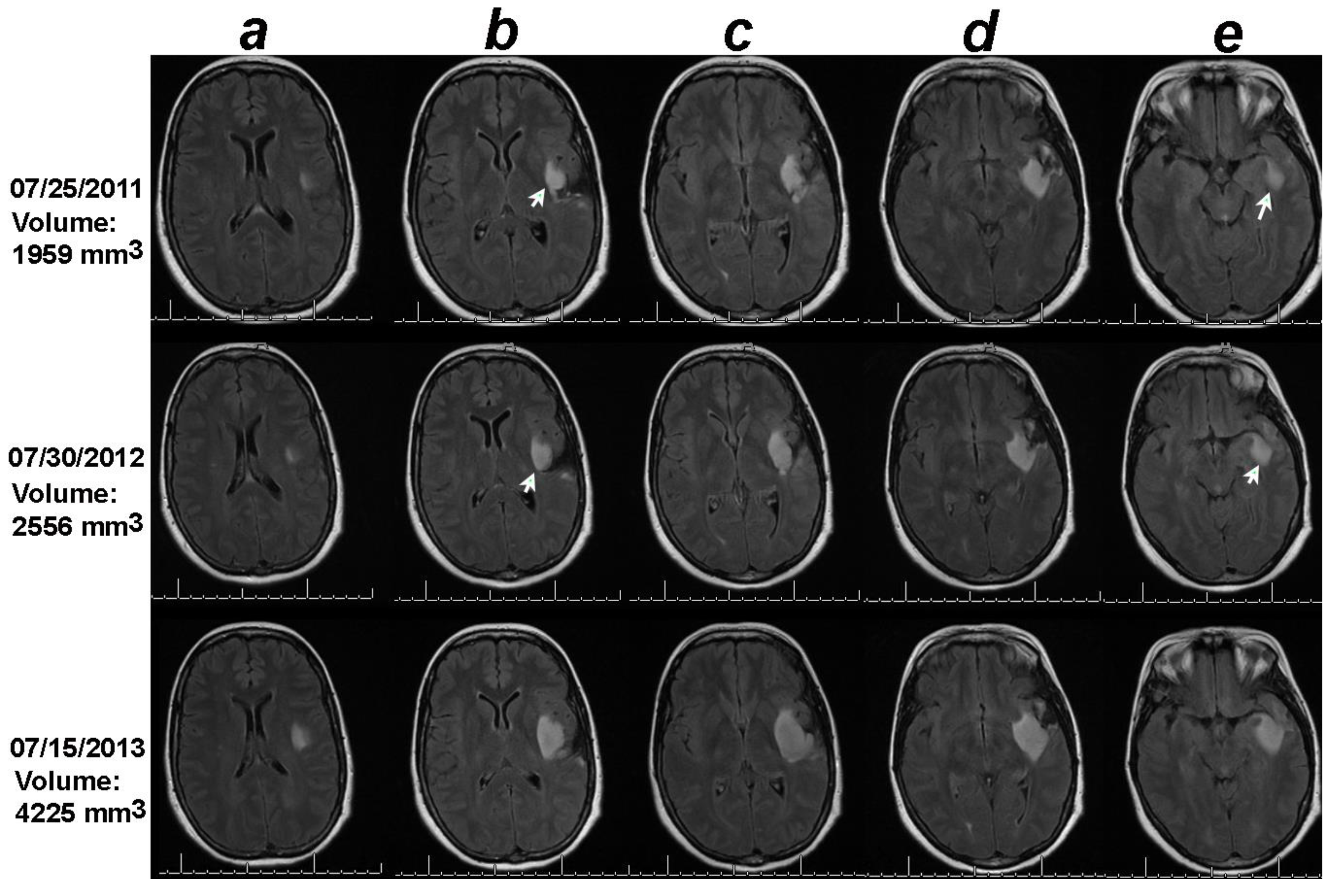

Figure 1.

Volumetric analysis combined with the online change-of-point statistical method detects progression on 07/30/2012, one year earlier than the date of progression documented in the clinical notes (07/15/2013). Notice that though the tumor in the 2D sections containing the largest tumors under columns c and d did not change between the baseline (07/25/2011) and 07/30/2012, the 2D sections in columns b and e increased in size between the baseline MRI of 07/25/2011 and date of progression detected by the change-of-point method, 07/30/3012 (white arrows). .

Figure 1.

Volumetric analysis combined with the online change-of-point statistical method detects progression on 07/30/2012, one year earlier than the date of progression documented in the clinical notes (07/15/2013). Notice that though the tumor in the 2D sections containing the largest tumors under columns c and d did not change between the baseline (07/25/2011) and 07/30/2012, the 2D sections in columns b and e increased in size between the baseline MRI of 07/25/2011 and date of progression detected by the change-of-point method, 07/30/3012 (white arrows). .

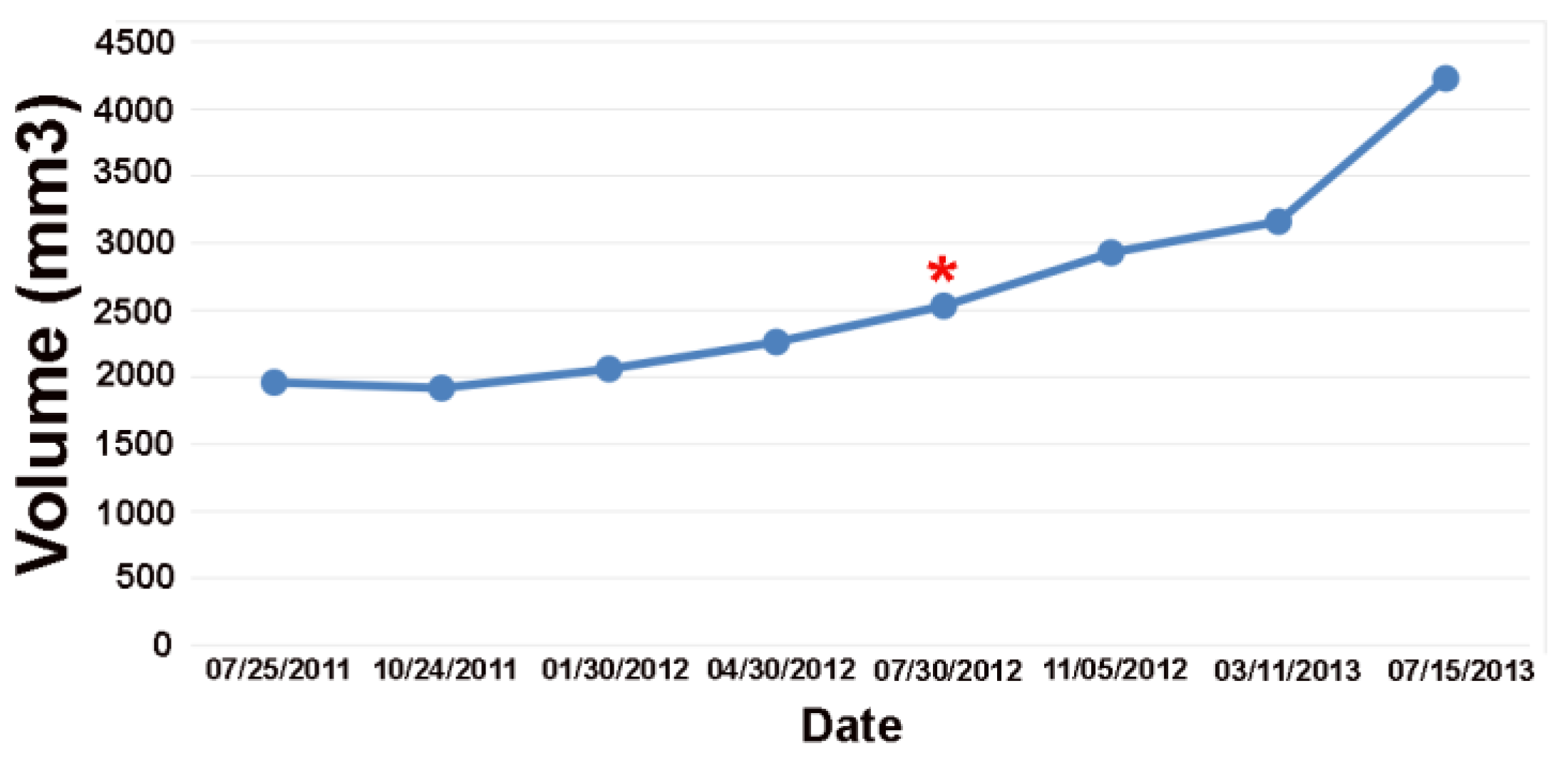

Figure 2.

Volume plot of the low-grade tumor shown in

Figure 1. The online change-of-point analysis detects progression at the red Asterix. The clinical notes detected progression one year later.

Figure 2.

Volume plot of the low-grade tumor shown in

Figure 1. The online change-of-point analysis detects progression at the red Asterix. The clinical notes detected progression one year later.

Clinically Stable Group

In the clinically stable group, including patients whose last MRI was interpreted as stable, where tumors were deemed stable by visual inspection, the MRIMath AI with physician review detected tumor growth in 13 out of 22 cases (

Table 2). Remarkably, this detection occurred at a median of 23 months earlier than the most recent MRI scan. In comparison, AI without human review detected growth at a median of 26 months earlier but missed 1 out of the 13 cases. Moreover, while AI with human review accurately flagged the remaining 9 cases as stable, AI without review incorrectly detected tumor growth in 1 of those 9 cases.

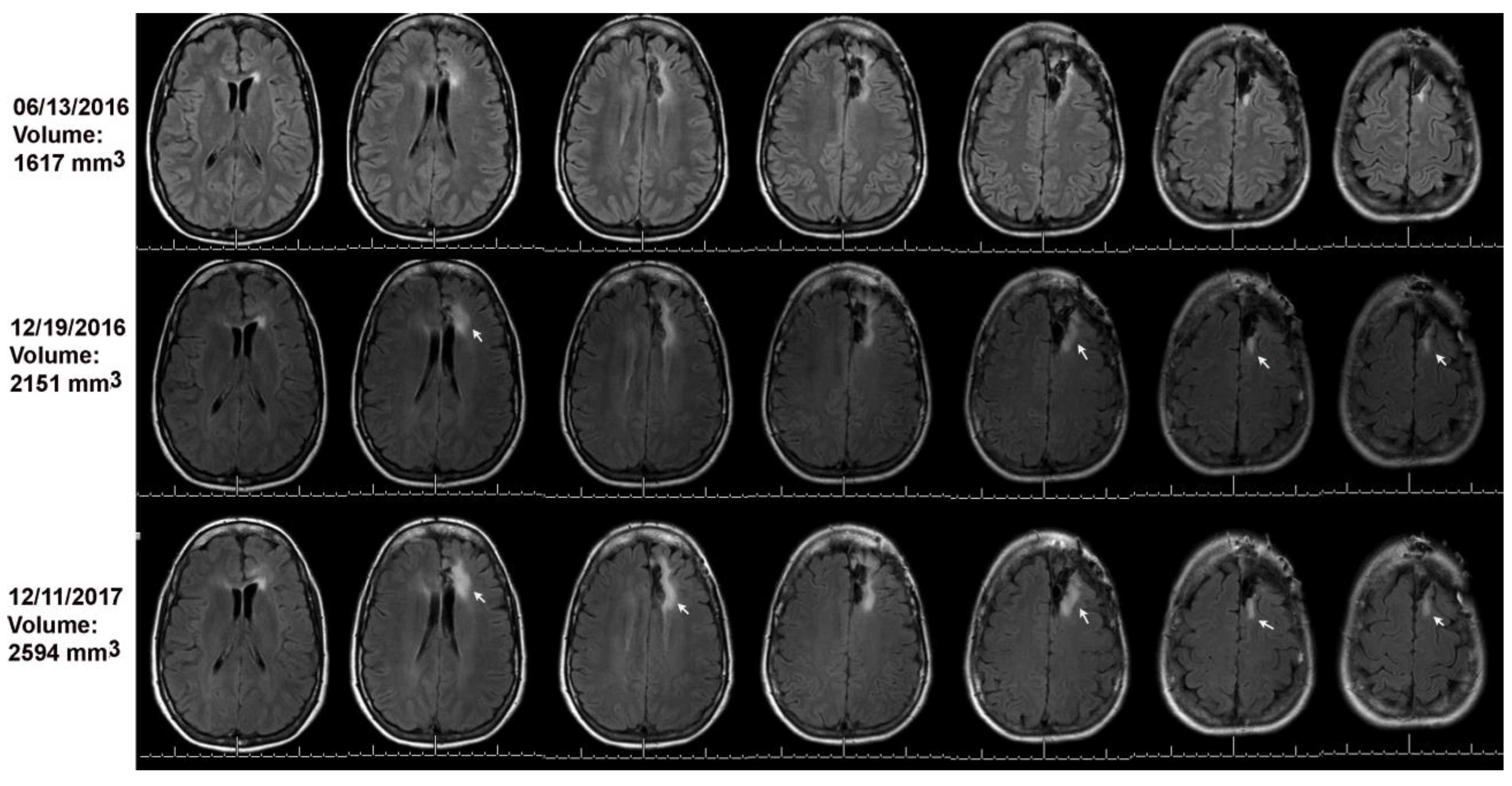

Figure 3.

Volumetric analysis combined with the online change-of-point method detected progression on 12/19/2016 (see arrows) as compared to baseline on 06/13/2016. The MRI on 12/11/2017 was read as stable; arrows point to tumor growth as compared to the MRI of 12/19/2016.

Figure 3.

Volumetric analysis combined with the online change-of-point method detected progression on 12/19/2016 (see arrows) as compared to baseline on 06/13/2016. The MRI on 12/11/2017 was read as stable; arrows point to tumor growth as compared to the MRI of 12/19/2016.

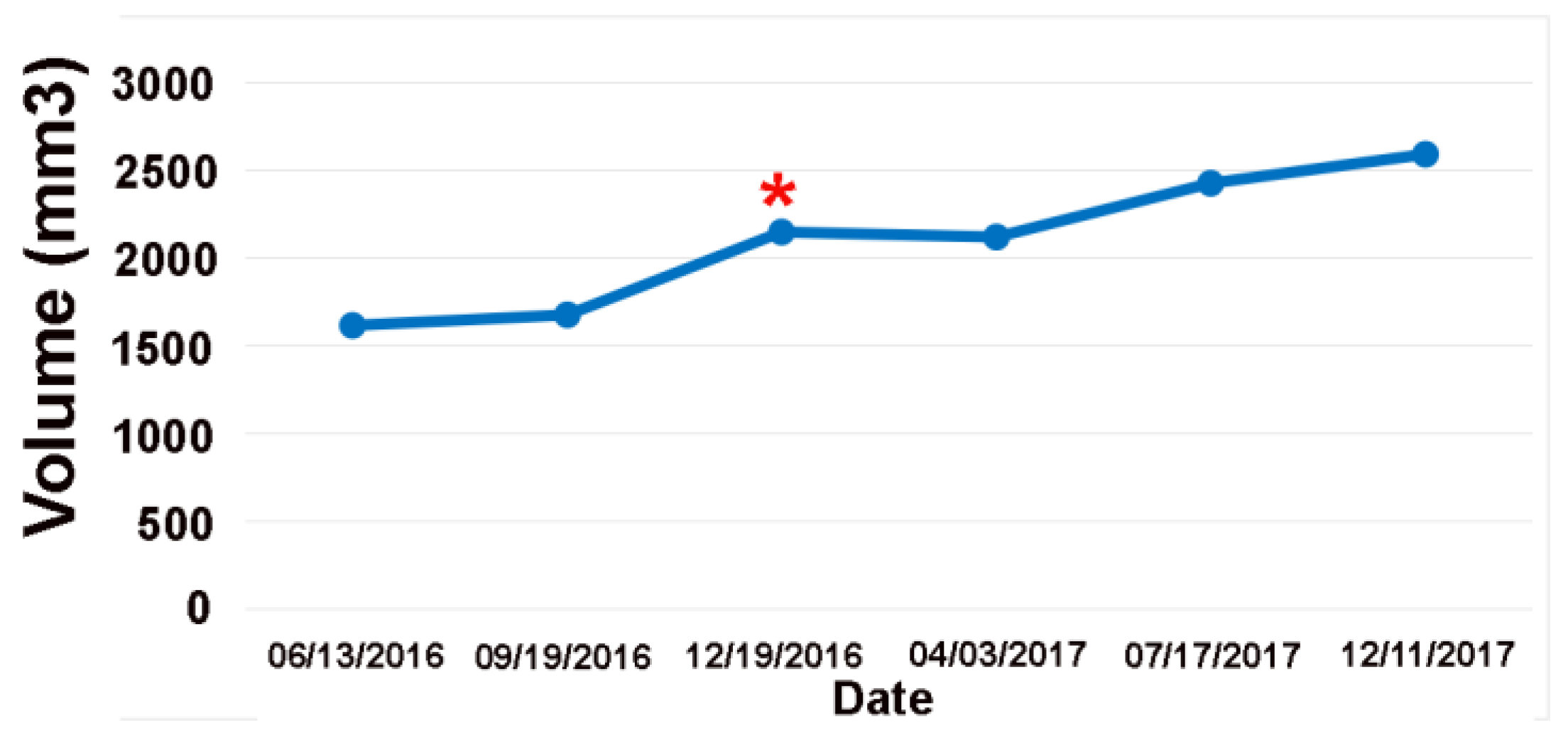

Figure 4.

Volume plot of the low-grade tumor shown in

Figure 2. The online change-of-point analysis detects progression at the red Asterix. The clinical notes considered all these MRIs as stable.

Figure 4.

Volume plot of the low-grade tumor shown in

Figure 2. The online change-of-point analysis detects progression at the red Asterix. The clinical notes considered all these MRIs as stable.

Negative Control Group

For the negative control group, where no tumor was seen on MRI visually and where radiological impressions indicated stable disease, the performance of the AI system varied significantly based on the presence of human review. The AI with physician review correctly identified all 7 cases as stable, demonstrating perfect specificity. In contrast, the AI without human review incorrectly diagnosed tumor growth in 3 out of 7 cases.

False Negative and False Positive Rates

False Negative Rates

By combining the 35 cases from the clinical progression group and the 13 cases from the clinically stable group that showed progression after computer-assisted diagnosis, the sensitivity The AI without human review missed 4 of these 48 cases (8.33%, Table 4).

False Positive Rates

By combining the 7 cases from the negative control group and 9 stable cases from the clinically stable group, we find that the AI without human review incorrectly flagged a total of 4/16 cases as tumor growth (

Table 3).

4. Discussion

We find that human-supervised, AI-supported measurements of longitudinal LGG volumes detect tumor growth significantly earlier than radiologists’ interpretations based solely on visual inspection. Furthermore, AI-generated segmentations—without human review—also identify progression dates earlier than visual inspection, although this comes at the cost of false positives and negatives, underscoring the importance of physician oversight. We segment the LGG using the MRIMath© FLAIR AI, which is FDA-approved for glioblastoma multiforme [

17,

18]; The “golden truth” is established by Board-certified physicians who review the AI-generated segmentations using the FDA-approved MRIMath© Smart Contouring platform. Our design, involving multiple reviewers from different subspecialties, mirrors real-world clinical scenarios. For volumetric assessment, we employed the statistical online change-of-point method to determine the first point of growth [

7]. The change-of-point method applies a consistent and rigorous statistical standard across all patients and studies. Unlike the conventional RANO product rule, which uses a universal approach based on the product of diameters, the change-of-point method assesses whether a current measurement significantly deviates from all previous measurements for the same patient.

Most clinical radiologists use visual inspection to evaluate longitudinal studies, while the RANO criteria remain the current standard for detecting progression in clinical trial settings [

19]. Significant limitations of the RANO criteria include large inter-user variability in determining the perpendicular diameters of the largest tumor cross-section and the reliance on two-dimensional measurements which may not accurately represent the complex three-dimensional tumor architecture [

11,

20]. Volumetric analysis was also shown to be superior to other established tumor classification criteria, such as the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) and modified RECIST [

21], due to their tendency to oversimplify a multidimensional and heterogeneous tumor [

22].

Volumetric measurement remains the gold standard for assessing the growth of low-grade gliomas (LGGs) and detecting progression. In particular, tumor volumes and growth rates serve as key prognostic factors [

23]. Several studies have reported improved diagnostic accuracy of volumetric analysis as compared to the RANO criteria and radiologists’ interpretations of longitudinal LGG imaging. From a series of 67 patients, Fathallah-Shaykh et al. and Fabio et al. report that volumetric measurements, when combined with the change-of-point method, detect progression at significantly earlier time points [

7,

11].

A recent analysis of the Phase I trial of ivosidenib for low-grade glioma also confirmed that 3D volumetric measurements outperform 2D measurements in response assessment with higher inter-reader agreement and lower rates of reader discordance [

24]

. The findings of two studies on pediatric gliomas support the conclusion that volumetric analysis is more effective than 2D measurements in diagnosing tumor progression at significantly earlier time points [

25,

26]

. In a study of 6 patients with pediatric glioma, Khalili et al. reported that volumetric analysis detected progression earlier than radiologists’ interpretations [

26]

. Similarly, in a study of recurrent gliomas, Dempsey et al. found that only volumetric measurements of tumor size were predictive of survival, unlike 1D, 2D, and 3D measurements [

27]

. One study compared one-dimensional (1D), two-dimensional (2D), and three-dimensional (3D) linear measurements with manual volume measurements in the follow-up of LGG. The authors concluded that 3D “linear” measurement of LGGs is superior to 1D and 2D methods, aligning well with tumor volume calculations, although it is not without limitations [

28]

.

The primary purpose of developing the linear methods—1D, 2D, and 3D—was to address the bottleneck created by the time and effort required to segment LGGs.

The MRIMath platform overcomes this bottleneck by using AI-generated segmentations, paired with the low-variability Smart contouring platform, to provide physician-reviewed volume measurements in under 3 minutes, making this technology easily accessible for clinical use [

9]

. The FDA has also approved teamspaces, allowing technicians, residents, and attendings to collaborate within permissions set by the owner, as well as the use of plots [

17,

18]

.

To our knowledge, our study is one of the few demonstrating the superiority of AI-assisted physician-reviewed longitudinal volume measurements of LGG compared to radiologists’ interpretations. Further research will compare AI-assisted 3D volumetric measurements with the standard 2D RANO criteria. With the advancement of efficient AI-assisted devices and reliable human review platforms, we believe that 3D volumetric measurements will greatly enhance glioma management, resulting in improved morbidity outcomes, longer survival times, and more accurate results.

Several methods are available for automatically assessing the volumes of gliomas. Compared to these methods, the MRIMath FLAIR AI stands out for being fully automated, as it does not require preprocessing steps that involve human supervision, such as deboning, interpolation, or registration. Additionally, while MRIMath© processes images in 2D and treats the FLAIR modality independently, other methods use a 3D approach and integrate the four modalities: T1, T1c, T2, and FLAIR [

14,

29]. MRIMath© has developed a FLAIR series AI, which differs from the subcomponent segmentations employed by other platforms.

The physicians used the MRIMath© Smart contouring platform to review, revise and approve the segmentations. This platform is associated with a low inter-user variability of 10% for FLAIR images [

9]. In a recent report, the mean dice score (DSC) of the gross tumor volume (GTV) of the FLAIR signal of low-grade gliomas was reported at 77% (substantial disagreement) [

30,

31]; in contrast, the mean DSC of the manual contouring of FLAIR images using the MRIMath smart platform was 92% [

9]. The variability of the reviewing software is important because a high variability in volume measurements could lead to inaccurate diagnosis of tumor progression.

Limitations of our study include a retrospective design, a small dataset from a single institution, using multiple reviewing physicians from different specialties, primarily using FLAIR sequences, and a comparison to visual inspection. Our goal is to evaluate the importance of AI volumetric analysis in real world scenarios where multiple physicians evaluate longitudinal LGG images.

The Response Assessment in Neuro-Oncology (RANO) criteria for lower-grade gliomas (LGGs) define tumor progression as ≥25% change in the T2/FLAIR signal area based on an operator’s discretion of the perpendicular diameter of the largest tumor cross-section. A recent study found that RANO-based assessment of LGGs has moderate reproducibility and poor accuracy when compared to either visual or volumetric ground truths. The median time delay at diagnosis by the RANO assessment for false negative cases was 2.05 years compared to the previous scan and 1.08 years for baseline scans [

11]

.

5. Conclusions

Our study highlights the effectiveness of AI-assisted volumetric analysis using the MRIMath FLAIR AI platform for detecting tumor growth in low-grade gliomas. By integrating AI with physician review, we were able to detect tumor progression at significantly earlier time points compared to traditional visual inspection methods. This study underscores the potential of AI in clinical oncology, particularly in enhancing the early detection of tumor growth, while also emphasizing the importance of human review in conjunction with a low-variability platform. Additionally, it highlights the potential use of accurate volume measurements in advancing clinical research [

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.M.F.S., H.S.; and N.B., methodology, Y.B., N.B., H.Y., H.S., and H.M.F.S.; software, Y.B.; validation, M.B., A.W., J.K., F.E.M., F.R., H.Y., and H.M.F.S.; formal analysis, H.M.F.S, H.S., M.B., and N.B.; investigation, H.M.F.S, H.S., M.B., and N.B.; resources, Y.B., H.Y., H.M.F.S., N.B., H.S.; data curation, Y.B., H.M.F.S., N.B., H.S.; writing—original draft preparation, H.M.F.S., H.S., and N.B.; writing—review and editing, Y.B., H.S., M.B., A.W., H.Y., J.K., F.E.M., F.R., N.B., and H.M.F.S., visualization, Y.B., H.S., M.B., A.W., J.K., F.E.M., F.R., N.B., and H.M.F.S.; supervision, H.S., N.B., and H.M.F.S.; project administration, H.S., N.B. and H.M.F.S.; funding acquisition, H.M.F.S and N.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Cancer Institute, Phase II SBIR contract number 75N91022C00051.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The institutional Review Board of the University of Alabama at Birmingham approved the research (IRB-150618007); waiver of informed consent was granted because the research involved no greater than minimal risk and no procedures for which written consent is normally required outside the research context.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the corresponding author on request.

Conflicts of Interest

Y.B. and H.Y. are employed by MRIMath. H.M.F.S. and N.B. are co-founders of MRIMath.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| LGG |

Low-grade-glioma |

| MRI |

Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

References

- Rimmer, B.; Bolnykh, I.; Dutton, L.; Lewis, J.; Burns, R.; Gallagher, P.; Williams, S.; Araujo-Soares, V.; Menger, F.; Sharp, L. Health-related quality of life in adults with low-grade gliomas: a systematic review. Qual Life Res 2023, 32, 625–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mellinghoff, I.K.; van den Bent, M.J.; Blumenthal, D.T.; Touat, M.; Peters, K.B.; Clarke, J.; Mendez, J.; Yust-Katz, S.; Welsh, L.; Mason, W.P.; et al. Vorasidenib in IDH1- or IDH2-Mutant Low-Grade Glioma. N Engl J Med 2023, 389, 589–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yogendran, L.; Rudolf, M.; Yeannakis, D.; Fuchs, K.; Schiff, D. Navigating disability insurance in the American healthcare system for the low-grade glioma patient. Neurooncol Pract 2023, 10, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuss, D.E.; Mamatjan, Y.; Schrimpf, D.; Capper, D.; Hovestadt, V.; Kratz, A.; Sahm, F.; Koelsche, C.; Korshunov, A.; Olar, A.; et al. IDH mutant diffuse and anaplastic astrocytomas have similar age at presentation and little difference in survival: a grading problem for WHO. Acta Neuropathol 2015, 129, 867–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Recht, L.D. Patient education: Low-grade glioma in adults (Beyond the Basics). UpToDate. Retrieved January 4, 2024 from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/low-grade-glioma-in-adults-beyond-the-basics 2024. 4 January.

- Nabors, L.B.; Portnow, J.; Ahluwalia, M.; Baehring, J.; Brem, H.; Brem, S.; Butowski, N.; Campian, J.L.; Clark, S.W.; Fabiano, A.J.; et al. Central Nervous System Cancers, Version 3.2020, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2020, 18, 1537–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathallah-Shaykh, H.M.; DeAtkine, A.; Coffee, E.; Khayat, E.; Bag, A.K.; Han, X.; Warren, P.P.; Bredel, M.; Fiveash, J.; Markert, J.; et al. Diagnosing growth in low-grade gliomas with and without longitudinal volume measurements: A retrospective observational study. PLoS Med 2019, 16, e1002810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Bent, M.J.; Wefel, J.S.; Schiff, D.; Taphoorn, M.J.; Jaeckle, K.; Junck, L.; Armstrong, T.; Choucair, A.; Waldman, A.D.; Gorlia, T.; et al. Response assessment in neuro-oncology (a report of the RANO group): assessment of outcome in trials of diffuse low-grade gliomas. Lancet Oncol 2011, 12, 583–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barhoumi, Y.; Fattah, A.H.; Bouaynaya, N.; Moron, F.; Kim, J.; Fathallah-Shaykh, H.M.; Chahine, R.A.; Sotoudeh, H. Robust AI-Driven Segmentation of Glioblastoma T1c and FLAIR MRI Series and the Low Variability of the MRIMath(c) Smart Manual Contouring Platform. Diagnostics (Basel) 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellingson, B.M.; Sanvito, F.; Cloughesy, T.F.; Huang, R.Y.; Villanueva-Meyer, J.E.; Pope, W.B.; Barboriak, D.P.; Shankar, L.K.; Smits, M.; Kaufmann, T.J.; et al. A Neuroradiologist’s Guide to Operationalizing the Response Assessment in Neuro-Oncology (RANO) Criteria Version 2.0 for Gliomas in Adults. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2024, 45, 1846–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raman, F.; Mullen, A.; Byrd, M.; Bae, S.; Kim, J.; Sotoudeh, H.; Moron, F.E.; Fathallah-Shaykh, H.M. Evaluation of RANO Criteria for the Assessment of Tumor Progression for Lower-Grade Gliomas. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dera, D.; Bouaynaya, N.; Fathallah-Shaykh, H.M. Automated Robust Image Segmentation: Level Set Method Using Nonnegative Matrix Factorization with Application to Brain MRI. Bull Math Biol 2016, 78, 1450–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminikhanghahi, S.; Cook, D.J. A Survey of Methods for Time Series Change Point Detection. Knowl Inf Syst 2017, 51, 339–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abayazeed, A.H.; Abbassy, A.; Mueller, M.; Hill, M.; Qayati, M.; Mohamed, S.; Mekhaimar, M.; Raymond, C.; Dubey, P.; Nael, K.; et al. NS-HGlio: A generalizable and repeatable HGG segmentation and volumetric measurement AI algorithm for the longitudinal MRI assessment to inform RANO in trials and clinics. Neurooncol Adv 2023, 5, vdac184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, C.O., L; Vayatis, N. Selective review of offline change point detection methods. Signal Processing 2020, 167, 107299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killick, R. Methods for Changepoint Detection. 2024, https://github.com/rkillick/changepoint/.

- i2Contour. U.S. Food and Drug Administration https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf23/K233822.pdf 2024.

- MRIMath LLC, a Medical AI Company, Announces FDA 510(k) Clearance for its Cyber Device and AI Solution for Glioblastoma. Businesswire https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20240820135568/en/MRIMath-LLC-a-Medical-AI-Company-Announces-FDA-510-k-Clearance-for-its-Cyber-Device-and-AI-Solution-for-Glioblastoma 2024.

- Jakola, A.S.; Reinertsen, I. Radiological evaluation of low-grade glioma: time to embrace quantitative data? Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2019, 161, 577–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramakrishnan, D.; von Reppert, M.; Krycia, M.; Sala, M.; Mueller, S.; Aneja, S.; Nabavizadeh, A.; Galldiks, N.; Lohmann, P.; Raji, C.; et al. Evolution and implementation of radiographic response criteria in neuro-oncology. Neurooncol Adv 2023, 5, vdad118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajkova, M.; Andrasina, T.; Ovesna, P.; Rohan, T.; Dostal, M.; Valek, V.; Ostrizkova, L.; Tucek, S.; Sedo, J.; Kiss, I. Volumetric Analysis of Hepatocellular Carcinoma After Transarterial Chemoembolization and its Impact on Overall Survival. In Vivo 2022, 36, 2332–2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhauer, E.A.; Therasse, P.; Bogaerts, J.; Schwartz, L.H.; Sargent, D.; Ford, R.; Dancey, J.; Arbuck, S.; Gwyther, S.; Mooney, M.; et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer 2009, 45, 228–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, C.; Lau, J.C.; Kosteniuk, S.E.; Lee, D.H.; Megyesi, J.F. Radiology reporting of low-grade glioma growth underestimates tumor expansion. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2019, 161, 569–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellingson, B.M.; Kim, G.H.J.; Brown, M.; Lee, J.; Salamon, N.; Steelman, L.; Hassan, I.; Pandya, S.S.; Chun, S.; Linetsky, M.; et al. Volumetric measurements are preferred in the evaluation of mutant IDH inhibition in non-enhancing diffuse gliomas: Evidence from a phase I trial of ivosidenib. Neuro Oncol 2022, 24, 770–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Reppert, M.; Ramakrishnan, D.; Bruningk, S.C.; Memon, F.; Abi Fadel, S.; Maleki, N.; Bahar, R.; Avesta, A.E.; Jekel, L.; Sala, M.; et al. Comparison of volumetric and 2D-based response methods in the PNOC-001 pediatric low-grade glioma clinical trial. Neurooncol Adv 2024, 6, vdad172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalili, N.K., A. F.; Bagheri, S.; Familiar, A.; Viswanathan, K.; Anderson, H.; Haldar, D.; Ware, J.B.; Vossough, A.; Ali Nabavizadeh, A. Volumetric measurment of tumor size outperforms standard two-dimensional method in early prediction of tumor progression in pediatric glioma. Neuro-Oncology 2023, 25, i48. [Google Scholar]

- Dempsey, M.F.; Condon, B.R.; Hadley, D.M. Measurement of tumor “size” in recurrent malignant glioma: 1D, 2D, or 3D? AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2005, 26, 770–776. [Google Scholar]

- Dos Santos, T.; Deverdun, J.; Chaptal, T.; Darlix, A.; Duffau, H.; Van Dokkum, L.E.H.; Coget, A.; Carriere, M.; Denis, E.; Verdier, M.; et al. Diffuse low-grade glioma: What is the optimal linear measure to assess tumor growth? Neurooncol Adv 2024, 6, vdae044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhong, P.; Jie, D.; Wu, J.; Zeng, S.; Chu, J.; Liu, Y.; Wu, E.X.; Tang, X. Brain Tumor Segmentation From Multi-Modal MR Images via Ensembling UNets. Front Radiol 2021, 1, 704888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wee, C.W.; Sung, W.; Kang, H.C.; Cho, K.H.; Han, T.J.; Jeong, B.K.; Jeong, J.U.; Kim, H.; Kim, I.A.; Kim, J.H.; et al. Evaluation of variability in target volume delineation for newly diagnosed glioblastoma: a multi-institutional study from the Korean Radiation Oncology Group. Radiat Oncol 2015, 10, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boer, A.H.; van der Weide, H.L.; Bongers, E.M.; Coremans, I.E.; Eekers, D.B.; de Groot, C.; van der Heide, H.; Niël, C.; van de Sande, M.A.; Smeenk, R.; et al. Inter-Observer Variation In Tumor Volume Delineation Of Low Grade Gliomas, A Multi-Institutional Contouring Study. Int J Radiat Oncol 2020, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.Y.; Young, R.J.; Ellingson, B.M.; Veeraraghavan, H.; Wang, W.; Tixier, F.; Um, H.; Nawaz, R.; Luks, T.; Kim, J.; et al. Volumetric analysis of IDH-mutant lower-grade glioma: a natural history study of tumor growth rates before and after treatment. Neuro Oncol 2020, 22, 1822–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ius, T.; Isola, M.; Budai, R.; Pauletto, G.; Tomasino, B.; Fadiga, L.; Skrap, M. Low-grade glioma surgery in eloquent areas: volumetric analysis of extent of resection and its impact on overall survival. A single-institution experience in 190 patients: clinical article. J Neurosurg 2012, 117, 1039–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, A.; Moreno, R.; Reiner, A.S.; Nandakumar, S.; Walch, H.S.; Thomas, T.M.; Nicklin, P.J.; Choi, Y.; Skakodub, A.; Malani, R.; et al. Tumor Volume Growth Rates and Doubling Times during Active Surveillance of IDH-mutant Low-Grade Glioma. Clin Cancer Res 2024, 30, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasil Caseiras, G.; Ciccarelli, O.; Altmann, D.R.; Benton, C.E.; Tozer, D.J.; Tofts, P.S.; Yousry, T.A.; Rees, J.; Waldman, A.D.; Jager, H.R. Low-grade gliomas: six-month tumor growth predicts patient outcome better than admission tumor volume, relative cerebral blood volume, and apparent diffusion coefficient. Radiology 2009, 253, 505–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakola, A.S.; Sagberg, L.M.; Gulati, S.; Solheim, O. Advancements in predicting outcomes in patients with glioma: a surgical perspective. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 2020, 20, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blomstergren, A.; Rydelius, A.; Abul-Kasim, K.; Latt, J.; Sundgren, P.C.; Bengzon, J. Evaluation of reproducibility in MRI quantitative volumetric assessment and its role in the prediction of overall survival and progression-free survival in glioblastoma. Acta Radiol 2019, 60, 516–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).