1. Introduction

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is introducing expanded capabilities to support decision-making in a variety of different contexts. Besides additional capabilities, AI can proactively alter the decision space and act on information. However, in the moment AI informational outputs may not be well understood [

1] and therefore can change the nature of human decision-making. Informational outputs from AI are also different than traditional sources of information due to the opaque underpinnings of these technologies [

2,

3,

4]. Additionally, humans anthropomorphizing AI system capabilities such as adhering to social norms when interacting with these technologies [

5] can produce unwarranted interactions with machines. For these reasons, researchers must understand how AI technologies can potentially and inadvertently affect decision-making processes.

Understanding how AI technologies impact human decision-making processes is not without warrant. Establishments like the military are undergoing significant transformations in technology and organization due to the development of AI [

6]. Several well-known accidents involving advanced technologies have demonstrated potential harmful side-effects of similar automated systems when combined with human response mechanisms. For example, tragic accidents such as the Patriot battery fratricide in Iraq [

7], the USS Vincennes incident [

8,

9,

10] the accidental killing of civilians in Afghanistan [

11], and the downing of two U.S. (United States) Army Blackhawk helicopters [

12] demonstrate the potential consequences of misconstruing information from complex automated systems. A common thread through these tragic accidents is how automated technology influenced human decision-making. In the aforementioned cases, information from automated technology was misconstrued or misinterpreted, and thus, over trusted by humans which contributed to incorrect decision-making [

13]. Moreover, there is increasing concern that humans are being beholden to decisions at machine speeds instead of systems in support of human decision-making processes [

14]. Therefore, understanding how AI impacts human decision-making processes is necessary for improving human-machine interaction research.

The structure of the paper is as follows. First, we begin by defining AI, its limitations, and how it is taking over additional decision space. Then, we review human-in-the-loop decision making. Next, we introduce quantum probability theory (QPT) for cognition and how it can improve outcomes by better modeling uncertainty and order effects within a human-AI decision-making. Lastly, we conclude by outlining future research.

2. What is AI?

There are numerous definitions of AI throughout the literature. In this plethora of definitions, AI and algorithms are used interchangeably throughout the research. In its simplest description, an algorithm is a recipe or a set of instructions to accomplish a sequence of tasks or achieve a particular result [

15]. Algorithms are often subcomponents of any AI system but may not be considered intelligent on their own. AI on the other hand is qualitatively different. In his seminal work that first coined the phrase in 1955, “artificial intelligence,” John McCarthy [

16] defines AI as “the science and engineering of making intelligent machines, especially intelligent computer programs” (p. 1). In Russell and Norvig’s [

17] treatment on the matter, they define AI as “machines that can compute how to act effectively and safely in a wide variety of novel situations” (p. 19). [

18] state, “AI is defined as the ability of a computer system to sense, reason, and respond to the environment” (p. 61). While these definitions provide a diverse characterization of AI, contemporary advances have pushed for additional divisions.

More recently, some researchers suggest that AI is characterized by the ability to imitate human information processing while also alleviating cognitive workloads for humans [

19,

20]. Moreover, AI can also be portrayed as weak AI or strong AI [

21]. Weak AI is characterized by programs that mimic human intelligence such as classification or that use natural language processing techniques, while strong AI is described as having a cognitive system that can reason and have goals similar to a human mind [

22]. In this paper, we define AI as a computer program that automates one of several aspects of human intelligence (e.g., categorization, classification, natural language processing, decision-making). This definition allows us to consider AI as an augmentation to a human decision-making process. We also recognize that such a narrow definition may not capture all aspects of what AI can currently be designed to perform, which is beyond the scope of this paper.

AI systems are created to accomplish a particular task commensurate with its design. However, most AI systems today are considered “brittle” [

23]. This brittleness stems from the fact that AI systems are designed for tasks or are trained on data sets that are limited in some respect. For instance, an AI designed for a classification task may not necessarily perform accurately at natural language processing. Yet, some AI programs today employ new techniques as seen in Google’s Gato program which are starting to break down this narrow barrier [

24]. Notwithstanding a few instances of more versatile AI, most AI today remains limited.

2.1. Limitations of AI

Advanced technologies such as AI can have several limitations and can promote unwarranted interactions. For instance, early research has shown that humans often anthropomorphize such intelligent agent-based systems by adhering to social norms when interacting with these technologies [

5]. Automation errors on tasks that appear “easy” to a human operator can also severely degrade trust and reliance in automation [

25]. Yet, AI has been characterized as ignorant and suffers from what some researchers identify as a Dunning–Kruger effect [

26]. Similarly, these failures can be summarized in Moravec’s Paradox. Moravec’s Paradox states that high-level intelligence tasks, such as chess and theorem proving are easy, but simple tasks such as stacking colored blocks or simple context dependent social interactions are extremely difficult for such machines [

27]. Other research suggests that external AI traits (e.g., human-like appearance, human-like responses) can influence a human user’s mental models in unhelpful ways [

28]. Advances to make AI decisions explainable have had mixed results. For instance, recent research has suggested that explainable AI does not necessarily improve user acceptance of AI advice [

29]. For these reasons, it has become increasingly important for researchers and practitioners to understand how AI technologies are taking over additional decision space.

2.2. AI Aspirations: Taking Over Addition Decision Space

AI is becoming more integrated into decision-making processes. This places humans in a position of responsibility and oversight for such AI advice. However, humans are increasingly disconnected spatially and temporally from what goes into algorithmic decision-making [

30], which makes it difficult to comprehend AI logics. This comprehension is essential in decision-making situations which involve rationalization of two more decision-making entities. Despite this, algorithms are gradually taking on traditional roles of management such as assigning tasks to workers, worker compensation, and evaluation of workers with little to no human oversight due to the sheer volume and scale of decisions [

31]. While automated decision-making may reduce human workload, it may also increase uncertainty and predictability of outcomes. This is because the essence of decision-making entails the choice amongst differing options [

32]. More specifically, uncertainty can be characterized as strategic uncertainty. [

33] define strategic uncertainty as “uncertainty about the actions of others in interactive situations” (p. 369). Actions of other agents (e.g., AI) may be difficult to understand or may unintentionally constrain decision options. For instance, if humans sense no degrees of freedom in choosing amongst AI choice alternatives, then choice may be an illusion. In such cases, humans may begin to sense a degree of arbitrariness or sense randomness in decision-making [

34]. To understand these complexities, this next section embarks on explicating human-in-the-loop constructs.

3. Human-in-the-Loop Decision-Making

AI is already supporting human decision-making in many ways. From Netflix recommendations to Uber drivers being managed by sophisticated algorithms, AI is taking over more decision space traditionally performed by humans [

35]. However, AI advancements are outpacing the conceptual coverage of human-computer decision-making [

36]. In some instances, AI is required due to the sheer scale or immediacy of the service, making human oversight in the decision process impractical [

31]. Yet, many decisions still require human oversight and keeping a human-in-the-loop (HITL) is important [

37]. For the immediate future, AI and humans will make contributions to automated decision-making processes [

38]. Still, understanding the distinct roles humans can have within a HITL construct can provide additional insights into decision-making with AI.

Humans can fulfill a variety of distinct roles when it comes to HITL constructs. [

23] define a HITL as “an individual who is involved in a single, particular decision made in conjunction with an algorithm” (p.12). In

Table 1, [

23] identified nine distinct roles a human may fulfill for a HITL system. These roles are not mutually exclusive and offer several improvements for HITL decision-making processes. While such roles can provide supervision to algorithmic decision-making, lack of comprehensible understanding in the dynamics of AI can affect the overall system and individual performance, and inadvertently influence subsequent judgements and decision outcomes. Thus, systemic improvement to HITL decision-making processes with predictable methods require the adoption of newer approaches to model human decision-making that can capture and model decision uncertainty.

4. Quantum Probability Theory for Decision-Making

The application of the mathematical axioms of quantum mechanics in decision modeling is breaking new ground in decision science. Despite the non-intuitive nature of applying the mathematical axioms of quantum mechanics to macro-level processes, the application of quantum formalisms to model human cognitive behaviors is gaining ascendency and broadening its application to new areas outside its original purpose [

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47]. For example, the concept of measurement/observation shares similarities to social anthropology by recognizing that observation in both fields changes the system [

49]. In spite of these reasons, the application of quantum formalisms can still require additional explanation to understand its benefits for modeling human behaviors.

Applying quantum mathematical axioms to human decision-making does not assume any ‘quantumness’ about the system of interest or that the human brain exhibits a quantum process. As [

50] state, “Quantum probability theory, as employed by behavioral scientists, simply concerns the basic probability rules of quantum theory without any of the physics” (p. 3). In terms of uncertainty, modeling decision-making with quantum mathematical axioms operationalizes a crucial dynamic, that is, judgment

creates rather than records what existed right before the judgement [emphasis added] [

41]. From the uncertainty point of view, one advantage for operationalizing this dynamic means that decision models include an ontic type of uncertainty. Ontic uncertainty can emerge when humans attempt rationalizing from a state of superposition (e.g., thinking about combinations of all potential perspectives) [

51]. Put another way, ontic uncertainty describes the cognitive indeterminacy represented by a combination of all possible outcomes [

41]. The crux of including this type of uncertainty in a decision model is that it is internal to the decision maker. Conventional modeling of human decision-making under uncertainty has fallen short in capturing the ontic type of uncertainty because of the limitation of the classical probability theory (CPT) [

52]. Therefore, the adoption of QPT principles can ameliorate human-AI decision making for the following CPT related limitations.

4.1. Ordering Effects That Affect Decision-Making

Daniel Kahneman’s work around cognitive biases is a good example to elucidate the modeling differences between CPT and QPT. His experiments and follow-on studies have demonstrated repeatedly the phenomenon of ordering effects of information, similarly referred to as an anchoring effect [

53,

54]. However, the developed explanations for order effects either lack a rigorous mathematical formulation or rely on set theoretical construct based on CPT (e.g., Markov evidence accumulation models). Hence, a Markov model’s lack of generalization limits the use of theories to ad-hoc descriptive explanations. The line of decision modeling research based on QPT has shown more tractable explanations for these effects than CPT. For instance, [

41] analyzed a Gallup poll from 1997 that asked 1002 respondents, “Do you generally think Bill Clinton is honest and trustworthy?” and then asked the same question about Al Gore. Half of those respondents were instead asked the same question in the opposite order. The results demonstrated a 15-point percentage difference between the two conditions which is not negligible. More importantly, QPT-based models can capture this difference, while CPT-based models fail to capture this difference. Similar effects can emerge in AI/ML supported decision-making situations when influenced by the trust in AI as an information provider. Therefore, building and engineering decision support systems can significantly benefit from QPT-based models [

45,

55].

Due to the limitation of CPT, thus far determined CPT violations are categorized fallacies, such as conjunction and disjunction fallacies [

41,

53], Allais paradox [

56], and Ellsberg paradox [

57]. Previous studies have also shown the relevance of this concept to HITL-AI systems decision-making environment [

58,

59]. For these reasons, addressing the order effects and the decision fallacies is critical for HITL-AI systems for decision-making for several reasons. First, it is argued that taking a measurement or interacting with a system “creates rather than records a property of a system” (Busemeyer & Bruza, 2014, p. 3). For instance, [

60] demonstrated how categorization by a computer versus human categorization can give rise to violations of total probability. Other studies have also shown how events might become incompatible because of how related information is processed sequentially with the first piece of information setting a context for the second event (e.g.,

) [

47,

50,

55,

61]. Second, the incompatibility of events makes it impossible for a human to form a joint probability across decisions, which signals contextuality [

38]. The inability to form a joint probability across decisions induces an ontic type of uncertainty. For these reasons, order effects of information within HITL-AI systems are an important consideration in decision-making.

4.2. Categorization-Decision

Another decision dynamic that poses challenges in AI supported decision-making is the categorization-decision paradigm. Categorization-Decision lines of research demonstrated that when a decision maker is asked to categorize and then decide vs. no explicit categorization and making decision directly, participants consistently made violations of total probability. For instance, in a study conducted by [

50,

62] participants who first categorized a face (e.g., labeled them bad or good), had a higher probability of commensurate follow-on action (e.g., bad, then attack vs. good, then withdraw). However, when the categorization step was removed, participants reversed their behaviors, thus, total probability of the two-event outcome was violated [

50]. Moreover, [

60] demonstrated that computer provided categorization-decision vs. direct decision results in total probability violation as it has been observed in various categorization research. This total probability violation alludes to the interference effects when there is no categorization. In an online experiment conducted by [

47], similar violations in total probability were observed in a categorization-decision task for an imagery analysis task supported by an AI assistant. For these reasons, AI supported decision-making highlights the need for more comprehensive modeling techniques to account for these human behaviors.

4.3. Interference Effects

Quantum models of cognition assume that evidence for decision-making results from a cumulative process over time and can result in interference effects when multiple system measurements are taken [

63]. For instance, [

44] demonstrated interference effects when human choice behavior early in the process strongly affected outcomes exhibited in the mean preference ratings later in time over a no-choice condition. The critical finding of this line of research is that when a participant is given the categorization (e.g., given by a computer), the total probability difference between the given categorization and direct decision conditions is still observed; interference effects, negative or positive, are captured via the total probability difference [

59,

60]. The examples cited challenge much of the conventional cognitive psychological research on human behavior that still capitalizes on the axioms on CPT to model human-AI decision-making without a truly satisfying answer that accounts for empirical violations of rational behavior.

Developing and designing tomorrow’s decision support systems (DSS) augmented with AI must, however, account for quirks of the human mind that give rise to dynamics and subsequent interference effects in human decision-making. The application of QPT to AI DSS will benefit from having a framework that can account for the cognitive consequences of processing incompatible information [

55]. The application of QPT to HITL-AI systems can open the door for not only better modeling of these systems, but to potentially engineer environments that improve decision-making.

5. How Quantum Cognition Can Improve Human-in-the-AI-Loop Decision-Making

QPT can help improve HITL-AI decision-making models by introducing the incompatibility condition that gives rise to interference effects. Interference effects can result in volatility in the outcome probabilities; hence, interference effects can give rise to erroneous understanding or oversight of the emergent behaviors in complex situation [

64]. Therefore, conditions that can give rise to incompatibility of different states must be accounted for in the models [

65].

Improving the design of the HITL-AI systems with QPT-based models provides at least two additional benefits over a CPT-based approaches: (1) a more comprehensive modeling of uncertainty, and (2) facility to investigate and determine the conditions that can give rise to incompatibility between decision variables. First, QPT can capture uncertainty more comprehensively (e.g., over evidence accumulation models) because it assumes that the cognitive system is not in an indefinite state [

47]. In QPT, one’s cognitive state can be characterized as oscillating between possible states also known as a superposition of states. However, once an interaction takes place, such as answering a question, the system, transiently, is put into a definite state. Using CPT-based models assumes that a cognitive system is at a definite state at any given time. Therefore, according to such classical models, a measurement records what existed before it takes place. As a result, CPT based models fail to capture the cognitive vacillation that occurs in the mind of a subject [

41] which is the internal uncertainty of the decision maker. Therefore, uncertainty cannot be accounted for in the decision model using CPT based models. For example, uncertainty is synonymous with experiencing ambiguity (an indefinite state), which is self-evidently true; otherwise, if one knew what state they were in, they could easily inform themselves of this state [

66]. In this case, existence of the second perspective sets an implicit context that may give rise to interference effects. Modeling decision making with QPT allows modelers to investigate and determine compatibility relation among perspectives and associated pairs of variables. Second, QPT can model both epistemic and ontic types of uncertainty. Epistemic uncertainty is characterized by an observer’s lack of knowledge about the state of a system at a particular time, which can be resolved through acquiring additional knowledge [

42,

52]. Ontic uncertainty describes a person’s internal uncertainty regarding a specific response, such as a decision amongst different options [

41,

44,

52]. The distinction between epistemic and ontic uncertainty is not recognized in cognitive models that use CPT-based models but should be considered in the design process of next the generation HITL-AI systems for improved decisions.

HITL-AI Example

Today’s search engines are powered by AI to leverage pattern detection and optimization to boost particular content [

67]. AI technologies such as large language models (i.e., ChatGPT, Google Search Labs) are now embedded in search engines as well [

68]. In the case of search, a human directs a search engine to explore specific terms of interest and receives a ranked the output. To illustrate the possible contributions of QPT based models, a general search engine story from

The Cyber Effect [

69] is discussed with a QPT-based model perspective.

Lisa went hiking with her friend during tick season; while hiking, she and her friend talked on assorted topics including ticks and Lyme disease. Upon returning home, she became worried about ticks. After examining her body, she finds a tick and removes it with the help of the information she obtained via online search. After removing the tick, she began searching about Lyme disease and its symptoms. She clicked from one search result to another, and after visiting various web pages, her anxiety increased. She continued reading more about Lyme disease. Click after click she tumbled into medical webpages, only increasing her anxiety. Lisa lost track of time, often missing relevant information during her searches that might have been calming. Based on her frenetic searches, Lisa started to think that she had Lyme disease and ended up visiting an urgent care in the morning. The doctor confirmed Lisa did not have Lyme disease but incurred costs for the unnecessary visit and contracted a virus from another patient who was visiting the same doctor’s office. [

69]

The similarity between categorization and decision for Lisa’s example is as follows. To decide Lyme positive, there are symptoms (e.g., having red eyes) that need to be categorized (explicitly). While searching online medical information about Lyme disease, Lisa could not make any categorization for the symptoms; for example, during her internet searches, Lisa observed her eyes had become red, the red eyes could be due to extended screen time she had while searching in the dark. Despite this context, red eyes were instead interpreted as a symptom of Lyme disease. Moreover, every new piece of AI-provided information introduces a new perspective for each introduced category and possibility. If perspectives are not categorized, consequently, they can continue to influence subsequent decision-making.

One can argue that using more interactive advanced search engines may obviate this problem. However, as [

70] articulates, language is indeterminate, and every phenomenon comes with presuppositions that are contextual and enunciation of those presuppositions cannot guarantee a compatible perspective to process information. For instance,

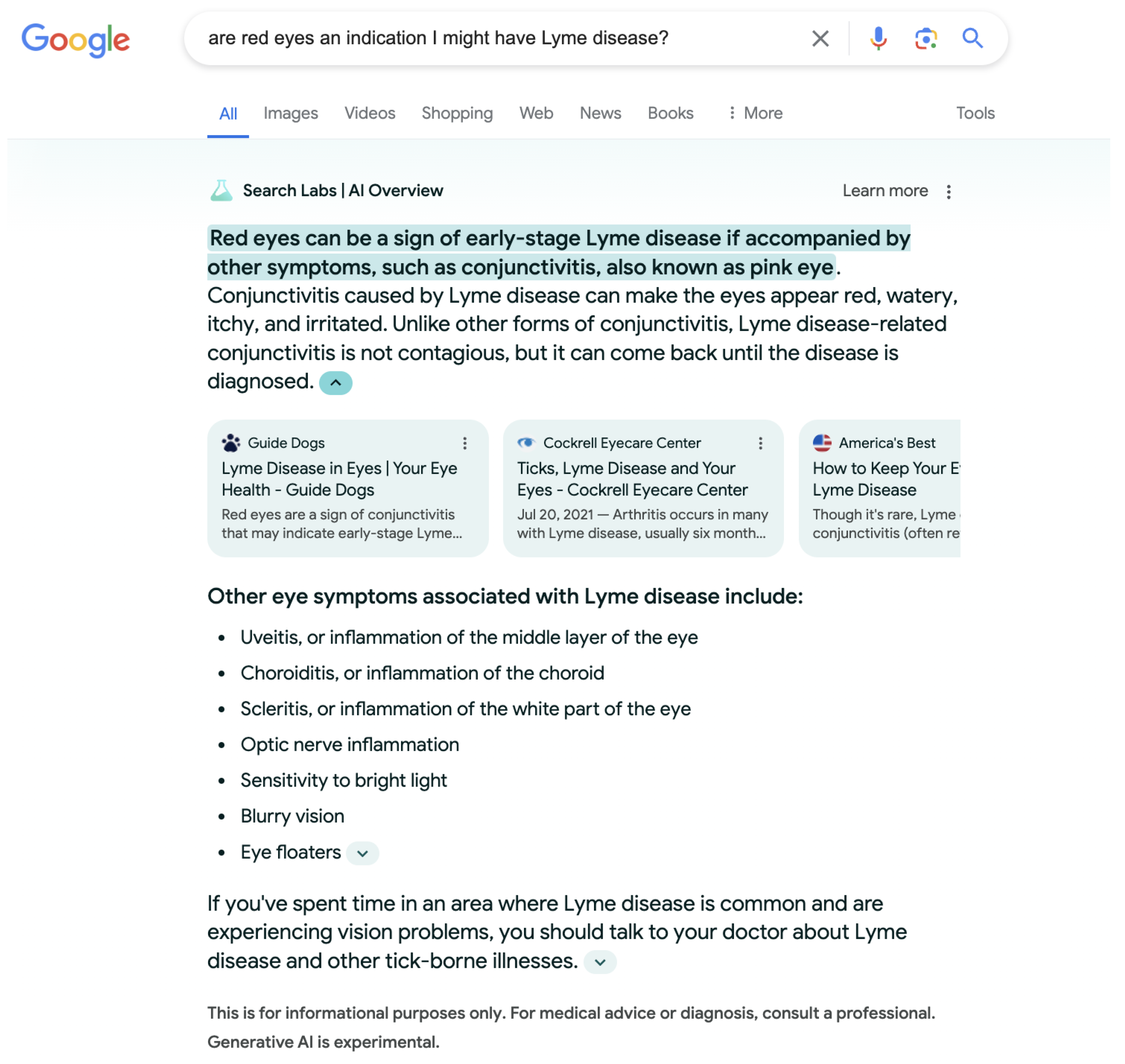

Figure 1 shows how a Google Generative AI experiment for search, an advanced large language model (LLM) AI, can provide helpful advice, but can result in vacillation because users may not be familiar with provided medical information. As a result, new perspectives becomes incompatible and begin influencing (forming context for) each other(e.g., other enumerated symptoms). Hence, the mental indecisiveness concerning the symptom categories can bolster positive Lyme disease belief. Since Lisa did not make any categorization while searching online, every new information introduced new states to the cognitive system. If these new states do not match with perspectives of the information processing individual, they begin influencing each other that results in vacillation.

After visiting a doctor, Lisa would establish the definite category choices for the symptoms from a professional with supported test results. Thereafter, Lisa would resolve her indecisiveness concerning the symptoms and would have a negative belief about having Lyme disease (because symptoms are not related to Lyme disease). Lisa’s negative belief about her condition would therefore not be influenced by any mental indecisiveness concerning potential intermediate symptoms. Hence, her Lyme disease probabilistic outcomes would not have volatility. To consider potential indecisiveness in design of HITL-AI systems through the lens of a similar interaction with an AI search engine, an AI can (1) push the human to a specific decision [

71]; (2) generate uncertainty concerning the decision outcomes and bolster one of them. To demonstrate the second situation following the discussion in [

72] that is based on quantum decision theory (QDT) and Kullback-Leibler relative information gain approach [

73,

74], a simulation for a two-decision outcome result was run with the following scenario. Suppose based on the regional tick bite and Lyme diagnoses data, a search engine assumes that 52 percent of the people with tick bites contracted Lyme diseases. Due to this data, the search engine optimizes its results in response to Lisa’s search entries in such a way that anyone reading the suggested pages would think that probability of having Lyme diseases is 0.52. As shown in

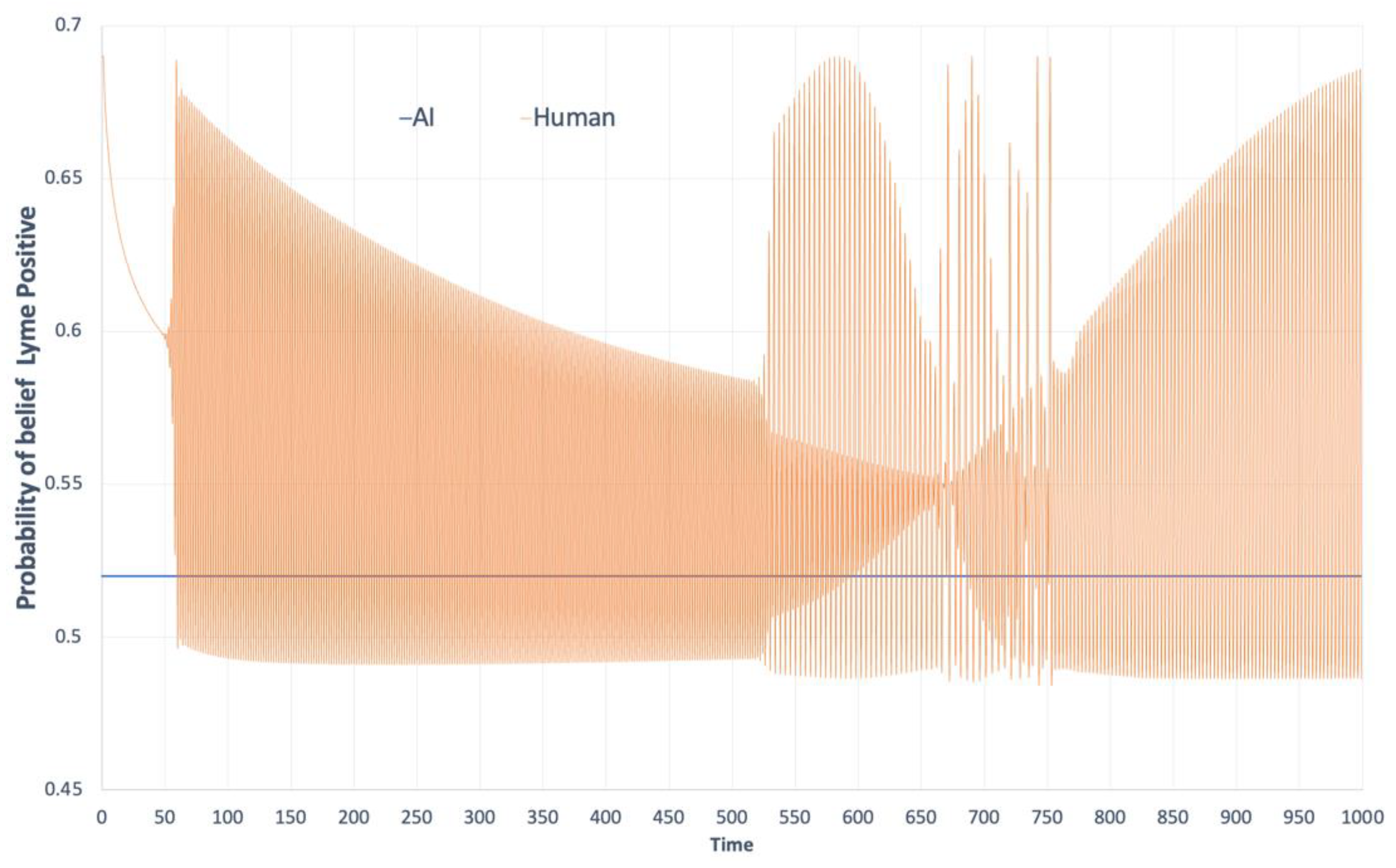

Figure 2, a probability of positive Lyme disease belief for Lisa can oscillate in the case of continuous inquiry from a search engine. The oscillation shown in

Figure 2 represents the ontic type of uncertainty that can bolster a specific decision outcome. We consider this oscillation as ontic type of uncertainty because it is internal to the human; it is not directly accessible to an observer unless the human elicits her/his decision at any given time. This oscillatory behavior may converge later in time or diverge depending on Lisa’s cognitive schema.. Therefore, capturing this type of uncertainty is important for properly modeling HITL-AI interactions in the design of decision support systems.

6. Discussion

Design considerations that capitalize on QPT-based decision models to improve human and machine interactions are still in their infancy. Some research has suggested that formalisms of QPT may be applied by machines for helping cognitively impaired humans (e.g., dementia or Alzheimer’s) achieve specific goals (e.g., washing hands, taking medications) [

71]. Yet, the same considerations can also apply to HITL-AI systems. Knowing the shortcomings of human reasoning and information processing, machines can better model human cognitive processes with QPT to account for how (1) humans are influenced by the order of information (e.g., humans should decide before AI reveals its own perspective, knowing when and whether to solicit for AI advice would lead to different decision outcomes [

75]); (2) new pieces of information can result in incompatible perspectives and higher ontic uncertainty. Considerations for these design parameters could improve engineering AI systems for decision-making through better predictability of human-machine interactions. Consequently, HITL-AI systems may be engineered to move human decision-making towards a more Bayesian optimal choice [

71]. With these design aspects in mind, much work still needs to be performed.

7. Future Research

It is clear humans and AI systems will increasingly engage in shared decision-making. What decisions are ceded to AI is still a work in progress. Decision speed will also be an area of great concern for some areas of decision-making (e.g., military, stock trading). How work practices are managed with the integration of human and machine technologies requires future research [

76]. For instance, increasing pressure to continually shorten decision cycles is a reality in most militaries today, especially at the military tactical level for finding and engaging targets [

6]. HITL-AI systems may accelerate such decision cycles. Future research will need to address how speed affects HITL-AI decision-making in high-tempo and ethically significant operations and what can be done to improve outcomes. Order effects have also been seen in human trust towards algorithms. For instance, Fenneman et al. (2021) found the humans exposed to algorithmic managers first exhibited lower thresholds for trust and higher thresholds for trust when they were introduced to human fund-managers first. Therefore, future research should address different interaction dynamics under multi-agent decision-making (i.e., human and AI) that may improve trust interactions in HITL-AI systems.

HITL-AI systems are anticipated to have second and third order effects on decision-making processes. It is projected that humans will continue to cede decision-making space to AI potentially without their awareness [

75]. This can lead to several suboptimal outcomes and unanticipated effects. First, humans could become de-skilled in their own decision-making abilities. Such warnings of de-skilling have been raised in areas ranging from neurosurgery [

78] and moral reasoning [

79] to decision-making itself [

80], and lowering workers’ collective negotiating powers [

81]. This zero-sum view is, however, not without warrant as AI systems encompass additional decision space. These outcomes may also lead to difficulties in justifying additional human training as a back-up to AI systems due to being viewed as duplicative costs. As a result, future research should address these HITL-AI shortcomings for it may de-skill workers and what may be done instead to correct such outcomes.

The proliferation of AI systems also complexifies human oversight. For instance, it is anticipated that workers, such as radiologists, may become “orchestrators” of a plethora of AI-based systems and their concomitant workflows [

75]. Research by [

82] suggests that algorithmic prescriptions may be overly complex, resulting in suboptimal decisions from users’ inhibition to trust such systems. In other instances, humans providing oversight to AI systems may become “algorithmic brokers” to translate machine outputs to others [

1]. Moreover, some scholars warn how “autonomous computer leaders” may make significant decisions without sufficient human oversight in the near future [

36]. Researchers will also have to consider how to align experts and non-experts with AI systems. Research suggests that experts and novices can perceive AI outputs differently, which can result in different judgments and decision outcomes [

75,

83,

84]. Future research should therefore address both levels of expertise and leadership for HITL-AI systems.

8. Summary

In one of Simon and Newell’s [

85] seminal papers,

Heuristic Problem Solving: The Next Advance in Operations Research, they stated, “In dealing with the ill-structured problems of management we have not had the mathematical tools we have needed—we have not had ‘judgment mechanics’ to match quantum mechanics” (p. 6). This, however, is no longer the case. Application of QPT to decision-making and similar efforts to formulate a concept of quantum models of decision [

41] and QDT [

73,

74,

86], have provided novel results that can better model uncertainty and human decision-making behaviors. Applying QPT to human and machine decision-making is still at a nascent stage of development at the human-machine dyad level. Still, researchers must begin coming to grips with how AI can subtlety begin taking over this decision space and how researchers may help address this new phenomenon.

Developing or employing AI systems will always involve human decision-making processes. Adopting AI in any form will yield some element of human decision-making, but researchers and practitioners will need to have a clear-eyed view of which elements are appropriate to delegate to machine intelligence [

87]. Yet, it is still clear that machines such as AI cannot provide new affordances outside what it was trained to perform [

88] or anticipate counterfactual outcomes [

89]. These shortcomings should, however, not necessarily deter practitioners from adopting AI for improving decision-making. Rather, such choices will affect how people may conceive HITL-AI as a complex sociotechnical system that requires an approach for joint optimization (e.g., structurally rational decision-making, joint cognitive systems). Therefore, human response mechanisms to fulfilling roles within HITL-AI systems will likely evolve in diverse ways. To address these challenges, conceptual coverage must stay apace of AI advancements and should be closely monitored to ensure decision-making is structurally rational and beneficial for all stakeholders.

Author Contributions

Research, S.H.; Writing—original draft, S.H.; Writing—review & editing, M.C., M.D.; Supervision, M.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is supported by the Military Sealift Command Award N0003323WX00531.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers who provided valuable feedback and recommendations which improved this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The views expressed in this document are those of the authors and do not reflect any official policy or position of the U.S. Department of Defense or the U.S. Government.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| CPT |

Classical Probability Theory |

| DSS |

Decision Support System |

| HITL |

Human-in-the-Loop |

| LLM |

Large Language Model |

| QDT |

Quantum Decision Theory |

| QPT |

Quantum Probability Theory |

References

- L. Waardenburg, M. Huysman, and A. V. Sergeeva, “In the land of the blind, the one-eyed man is king: knowledge brokerage in the age of learning algorithms,” Organ. Sci., vol. 33, no. 1, pp. 59–82, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Gelles, D. McElfresh, and A. Mittu, “Project report: perceptions of AI in hiring,” College Park, MD, Oct. 2018. [Online]. Available: https://anjali.mittudev.com/content/Fairness_in_AI.pdf.

- D. Kaur, S. Uslu, K. J. Rittichier, and A. Durresi, “Trustworthy artificial intelligence: a review,” ACM Comput. Surv., vol. 55, no. 2, pp. 1–38, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Zuboff, In the age of the smart machine: the future of work and power, Reprint edition. New York: Basic Books, 1989.

- B. Reeves and C. Nass, The media equation: how people treat computers, television, and new media like real people and places. Stanford, Calif: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- M. Wrzosek, “Challenges of contemporary command and future military operations | Scienti,” Sci. J. Mil. Univ. Land Forces, vol. 54, no. 1, pp. 35–51, 2022.

- J. K. Hawley and A. L. Mares, “Human performance challenges for the future force: lessons from patriot after the second gulf war,” in Designing Soldier Systems, CRC Press, 2012.

- A. Bisantz, J. Llinas, Y. Seong, R. Finger, and J.-Y. Jian, “Empirical investigations of trust-related systems vulnerabilities in aided, adversarial decision making,” State Univ of New York at Buffalo center of multisource information fusion, Mar. 2000. Accessed: Apr. 30, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/citations/ADA389378.

- D. R. Hestad, “A discretionary-mandatory model as applied to network centric warfare and information operations,” NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL MONTEREY CA, Mar. 2001. Accessed: Apr. 30, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/citations/ADA387764.

- S. Marsh and M. R. Dibben, “The role of trust in information science and technology,” Annu. Rev. Inf. Sci. Technol., vol. 37, no. 1, pp. 465–498, 2003. [CrossRef]

- P. J. Denning and J. Arquilla, “The context problem in artificial intelligence,” Commun. ACM, vol. 65, no. 12, pp. 18–21, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. A. Snook, Friendly fire: the accidental shootdown of u.s. black hawks over northern iraq. Princeton University Press, 2011. [CrossRef]

- S. Humr, M. Canan, and M. Demir, “A Quantum Decision Approach for Human-AI Decision-Making,” in EPiC Series in Computing, EasyChair, Jul. 2024, pp. 111–125. [CrossRef]

- D. Blair, J. O. Chapa, S. Cuomo, and J. Hurst, “Humans and hardware: an exploration of blended tactical workflows using john boyd’s ooda loop,” in The Conduct of War in the 21st Century, Routledge, 2021.

- E. Finn, What algorithms want: imagination in the age of computing, 1st ed. Boston, MA: MIT Press, 2018. Accessed: Nov. 11, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://mitpress.mit.edu/9780262536042/what-algorithms-want/.

- J. McCarthy, “What is artificial intelligence?,” Nov. 12, 2007. [Online]. Available: URL: http://www-formal.stanford.edu/jmc/whatisai.html.

- S. Russell and P. Norvig, Artificial intelligence: a modern approach, 3rd edition. Upper Saddle River: Pearson, 2009.

- C. Hughes, L. Robert, K. Frady, and A. Arroyos, “Artificial intelligence, employee engagement, fairness, and job outcomes,” in Managing Technology and Middle- and Low-skilled Employees, in The Changing Context of Managing People. , Emerald Publishing Limited, 2019, pp. 61–68. [CrossRef]

- G. Matthews, A. R. Panganiban, J. Lin, M. Long, and M. Schwing, “Chapter 3 - Super-machines or sub-humans: Mental models and trust in intelligent autonomous systems,” in Trust in Human-Robot Interaction, C. S. Nam and J. B. Lyons, Eds., Academic Press, 2021, pp. 59–82. [CrossRef]

- K. Scott, “I do not think it means what you think it means: artificial intelligence, cognitive work & scale,” Daedalus, vol. 151, no. 2, pp. 75–84, May 2022. [CrossRef]

- C. Collins, D. Dennehy, K. Conboy, and P. Mikalef, “Artificial intelligence in information systems research: a systematic literature review and research agenda,” Int. J. Inf. Manag., vol. 60, p. 102383, Oct. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Carter, Minds and computers: an introduction to the philosophy of artificial intelligence. Edinburgh University Press, 2007.

- R. Crootof, M. E. Kaminski, and W. N. Price II, “Humans in the loop,” Mar. 25, 2022, Rochester, NY: 4066781. [CrossRef]

- S. Reed et al., “A generalist agent,” May 19, 2022, arXiv: arXiv:2205.06175. [CrossRef]

- P. Madhavan, D. A. Wiegmann, and F. C. Lacson, “Automation failures on tasks easily performed by operators undermine trust in automated aids,” Hum. Factors, vol. 48, no. 2, pp. 241–256, Jun. 2006. [CrossRef]

- G. J. Cancro, S. Pan, and J. Foulds, “Tell me something that will help me trust you: a survey of trust calibration in human-agent interaction,” May 05, 2022, arXiv: arXiv:2205.02987. Accessed: May 31, 2022. [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/2205.02987.

- H. Moravec, “When will computer hardware match the human brain?,” J. Evol. Technol., vol. 1, 1998, [Online]. Available: https://jetpress.org/volume1/moravec.pdf.

- B. P. Knijnenburg and M. C. Willemsen, “Inferring capabilities of intelligent agents from their external traits,” ACM Trans. Interact. Intell. Syst., vol. 6, no. 4, p. 28:1-28:25, Nov. 2016. [CrossRef]

- C. Ebermann, M. Selisky, and S. Weibelzahl, “Explainable AI: The Effect of Contradictory Decisions and Explanations on Users’ Acceptance of AI Systems,” Int. J. Human–Computer Interact., vol. 0, no. 0, pp. 1–20, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- V. Bader and S. Kaiser, “Algorithmic decision-making? The user interface and its role for human involvement in decisions supported by artificial intelligence,” Organization, vol. 26, no. 5, pp. 655–672, Sep. 2019. [CrossRef]

- P. D. Harms and G. Han, “Algorithmic leadership: the future is now,” J. Leadersh. Stud., vol. 12, no. 4, pp. 74–75, Feb. 2019. [CrossRef]

- N. Luhmann, Organization and decision. Cambridge, United Kingdom ; New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

- R. Hertwig, T. J. Pleskac, and T. Pachur, Taming uncertainty, 1st ed. MIT Press, 2019. Accessed: Dec. 04, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://mitpress.mit.edu/9780262039871/taming-uncertainty/.

- K. Brunsson and N. Brunsson, Decisions: the complexities of individual and organizational decision-making. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Pub, 2017.

- M. Frank, P. Roehrig, and B. Pring, What to do when machines do everything: how to get ahead in a world of ai, algorithms, bots, and big data. John Wiley & Sons, 2017.

- J. S. Wesche and A. Sonderegger, “When computers take the lead: The automation of leadership,” Comput. Hum. Behav., vol. 101, pp. 197–209, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- T. Saßmannshausen, P. Burggräf, J. Wagner, M. Hassenzahl, T. Heupel, and F. Steinberg, “Trust in artificial intelligence within production management – an exploration of antecedents,” Ergonomics, pp. 1–18, May 2021. [CrossRef]

- P. D. Bruza and E. C. Hoenkamp, “Reinforcing trust in autonomous systems: a quantum cognitive approach,” in Foundations of Trusted Autonomy, H. A. Abbass, J. Scholz, and D. J. Reid, Eds., in Studies in Systems, Decision and Control. , Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2018, pp. 215–224. [CrossRef]

- D. Aerts, “Quantum structure in cognition,” J. Math. Psychol., vol. 53, no. 5, pp. 314–348, Oct. 2009. [CrossRef]

- P. M. Agrawal and R. Sharda, “Quantum mechanics and human decision making,” Aug. 05, 2010, Rochester, NY: 1653911. [CrossRef]

- J. R. Busemeyer and P. D. Bruza, Quantum models of cognition and decision, Reissue edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

- J. Jiang and X. Liu, “A quantum cognition based group decision making model considering interference effects in consensus reaching process,” Comput. Ind. Eng., vol. 173, p. 108705, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Khrennikov, “Social laser model for the bandwagon effect: generation of coherent information waves,” Entropy, vol. 22, no. 5, Art. no. 5, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- P. D. Kvam, J. R. Busemeyer, and T. J. Pleskac, “Temporal oscillations in preference strength provide evidence for an open system model of constructed preference,” Sci. Rep., vol. 11, no. 1, Art. no. 1, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. Roeder et al., “A Quantum Model of Trust Calibration in Human–AI Interactions,” Entropy, vol. 25, no. 9, Art. no. 9, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. S. Trueblood and J. R. Busemeyer, “A comparison of the belief-adjustment model and the quantum inference model as explanations of order effects in human inference,” Proc. Annu. Meet. Cogn. Sci. Soc., vol. 32, no. 32, p. 7, 2010.

- S. Humr and M. Canan, “Intermediate Judgments and Trust in Artificial Intelligence-Supported Decision-Making,” Entropy, vol. 26, no. 6, Art. no. 6, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Stenholm and K.-A. Suominen, Quantum approach to informatics, 1st edition. Hoboken, N.J: Wiley-Interscience, 2005.

- L. Floridi, The philosophy of information. OUP Oxford, 2013.

- E. M. Pothos, O. J. Waddup, P. Kouassi, and J. M. Yearsley, “What is rational and irrational in human decision making,” Quantum Rep., vol. 3, no. 1, Art. no. 1, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- E. M. Pothos and J. R. Busemeyer, “Quantum cognition,” Annu. Rev. Psychol., vol. 73, pp. 749–778, 2022.

- J. R. Busemeyer, P. D. Kvam, and T. J. Pleskac, “Comparison of Markov versus quantum dynamical models of human decision making,” WIREs Cogn. Sci., vol. 11, no. 4, p. e1526, 2020. [CrossRef]

- D. Kahneman, Thinking, Fast and Slow, 1st edition. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2013.

- D. Kahneman, S. P. Slovic, and A. Tversky, Judgment Under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases. Cambridge University Press, 1982.

- M. Canan, “Non-commutativity, incompatibility, emergent behavior and decision support systems,” Procedia Comput. Sci., vol. 140, pp. 13–20, 2018. [CrossRef]

- R. Blutner and P. beim Graben, “Quantum cognition and bounded rationality,” Synthese, vol. 193, no. 10, pp. 3239–3291, Oct. 2016. [CrossRef]

- F. Vaio, “The quantum-like approach to modeling classical rationality violations: an introduction,” Mind Soc., vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 105–123, Jun. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Z. Wang and J. R. Busemeyer, “Interference effects of categorization on decision making,” Cognition, vol. 150, pp. 133–149, May 2016. [CrossRef]

- R. Zheng, J. R. Busemeyer, and R. M. Nosofsky, “Integrating categorization and decision-making,” Cogn. Sci., vol. 47, no. 1, p. e13235, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Z. Wang and J. Busemeyer, “Order effects in sequential judgments and decisions,” in Reproducibility, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2016, pp. 391–405. [CrossRef]

- M. Ashtiani and M. A. Azgomi, “A formulation of computational trust based on quantum decision theory,” Inf. Syst. Front., vol. 18, no. 4, pp. 735–764, Aug. 2016. [CrossRef]

- J. T. Townsend, K. M. Silva, J. Spencer-Smith, and M. J. Wenger, “Exploring the relations between categorization and decision making with regard to realistic face stimuli,” Pragmat. Cogn., vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 83–105, Jan. 2000. [CrossRef]

- P. D. Kvam, T. J. Pleskac, S. Yu, and J. R. Busemeyer, “Interference effects of choice on confidence: Quantum characteristics of evidence accumulation,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., vol. 112, no. 34, pp. 10645–10650, Aug. 2015. [CrossRef]

- M. Canan and A. Sousa-Poza, “Pragmatic idealism: towards a probabilistic framework of shared awareness in complex situations,” in 2019 IEEE Conference on Cognitive and Computational Aspects of Situation Management (CogSIMA), Apr. 2019, pp. 114–121. [CrossRef]

- T. Darr, R. Mayer, R. D. Jones, T. Ramey, and R. Smith, “Quantum probability models for decision making,” presented at the 24th International Command and Control Research & Technology Symposium, ICCRTS, 2019, p. 20.[Online]. Available: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/53bad224e4b013a11d687e40/t/5dc42d54e8437d748186b031/1573137749772/24th_ICCRTS_paper_8.pdf.

- J. M. Yearsley, “Advanced tools and concepts for quantum cognition: A tutorial,” J. Math. Psychol., vol. 78, pp. 24–39, Jun. 2017. [CrossRef]

- E. Nick, “How Artificial Intelligence Is Powering Search Engines - DataScienceCentral.com,” Data Science Central. Accessed: May 22, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.datasciencecentral.com/how-artificial-intelligence-is-powering-search-engines/.

- R. Zhao, X. Li, Y. K. Chia, B. Ding, and L. Bing, “Can ChatGPT-like Generative Models Guarantee Factual Accuracy? On the Mistakes of New Generation Search Engines,” Mar. 02, 2023, arXiv: arXiv:2304.11076. Accessed: May 22, 2023. [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/2304.11076.

- M. Aiken, The Cyber Effect: An Expert in Cyberpsychology Explains How Technology Is Shaping Our Children, Our Behavior, and Our Values--and What We Can Do About It, Reprint edition. Random House, 2017.

- A. N. Whitehead, Process and Reality, 2nd edition. New York: Free Press, 1979.

- L. Snow, S. Jain, and V. Krishnamurthy, “Lyapunov based stochastic stability of human-machine interaction: a quantum decision system approach,” Mar. 31, 2022, arXiv: arXiv:2204.00059. [CrossRef]

- M. Canan, M. Demir, and S. Kovacic, “A Probabilistic Perspective of Human-Machine Interaction,” Jan. 2022. Accessed: Jul. 26, 2022. [Online]. Available: http://hdl.handle.net/10125/80256.

- V. I. Yukalov, “Evolutionary Processes in Quantum Decision Theory,” Entropy, vol. 22, no. 6, Art. no. 6, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- V. I. Yukalov, E. P. Yukalova, and D. Sornette, “Information processing by networks of quantum decision makers,” Phys. Stat. Mech. Its Appl., vol. 492, pp. 747–766, Feb. 2018. [CrossRef]

- E. Jussupow, K. Spohrer, A. Heinzl, and J. Gawlitza, “Augmenting medical diagnosis decisions? An investigation into physicians’ decision-making process with artificial intelligence,” Inf. Syst. Res., vol. 32, no. 3, pp. 713–735, Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. H. Jarrahi, G. Newlands, M. K. Lee, C. T. Wolf, E. Kinder, and W. Sutherland, “Algorithmic management in a work context,” Big Data Soc., vol. 8, no. 2, p. 20539517211020332, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Fenneman, J. Sickmann, T. Pitz, and A. G. Sanfey, “Two distinct and separable processes underlie individual differences in algorithm adherence: Differences in predictions and differences in trust thresholds,” PLOS ONE, vol. 16, no. 2, p. e0247084, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. S. Panesar, M. Kliot, R. Parrish, J. Fernandez-Miranda, Y. Cagle, and G. W. Britz, “Promises and Perils of Artificial Intelligence in Neurosurgery,” Neurosurgery, vol. 87, no. 1, pp. 33–44, Jul. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Vallor, “Moral deskilling and upskilling in a new machine age: reflections on the ambiguous future of character,” Philos. Technol., vol. 28, no. 1, pp. 107–124, Mar. 2015. [CrossRef]

- B. P. Green, “Artificial Intelligence, Decision-Making, and Moral Deskilling,” Santa Clara University. Accessed: Nov. 27, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.scu.edu/ethics/focus-areas/technology-ethics/resources/artificial-intelligence-decision-making-and-moral-deskilling/.

- M. H. Jarrahi, “In the age of the smart artificial intelligence: AI’s dual capacities for automating and informating work,” Bus. Inf. Rev., vol. 36, no. 4, pp. 178–187, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. Sun, D. J. Zhang, H. Hu, and J. A. Van Mieghem, “Predicting Human Discretion to Adjust Algorithmic Prescription: A Large-Scale Field Experiment in Warehouse Operations,” Manag. Sci., vol. 68, no. 2, pp. 846–865, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- V. Arnold, P. A. Collier, S. A. Leech, and S. G. Sutton, “Impact of intelligent decision aids on expert and novice decision-makers’ judgments,” Account. Finance, vol. 44, no. 1, pp. 1–26, 2004. [CrossRef]

- S. Gaube et al., “Do as AI say: susceptibility in deployment of clinical decision-aids,” Npj Digit. Med., vol. 4, no. 1, Art. no. 1, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. A. Simon and A. Newell, “Heuristic problem solving: the next advance in operations research,” Oper. Res., vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 1–10, Feb. 1958. [CrossRef]

- M. Favre, A. Wittwer, H. R. Heinimann, V. I. Yukalov, and D. Sornette, “Quantum decision theory in simple risky choices,” PLOS ONE, vol. 11, no. 12, p. e0168045, Dec. 2016. [CrossRef]

- L. Floridi and J. Cowls, “A unified framework of five principles for AI in society,” Harv. Data Sci. Rev., vol. 1, no. 1, Jul. 2019, Accessed: Nov. 26, 2022. [Online]. Available. [CrossRef]

- S. A. Kauffman and A. Roli, “What is consciousness? Artificial intelligence, real intelligence, quantum mind, and qualia,” Jun. 29, 2022, arXiv: arXiv:2106.15515. [CrossRef]

- J. Pearl and D. Mackenzie, The book of why: the new science of cause and effect. New York, NY: Basic Books, 2018.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).