Submitted:

07 January 2025

Posted:

08 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

2.2. Cell Viability Assay

2.3. Apoptosis Assay

2.4. Western Blotting

2.5. Bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) Incorporation Assay

2.6. Quantitative RT-PCR

2.7. Rescue Experiments Using miRNA Inhibitor

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

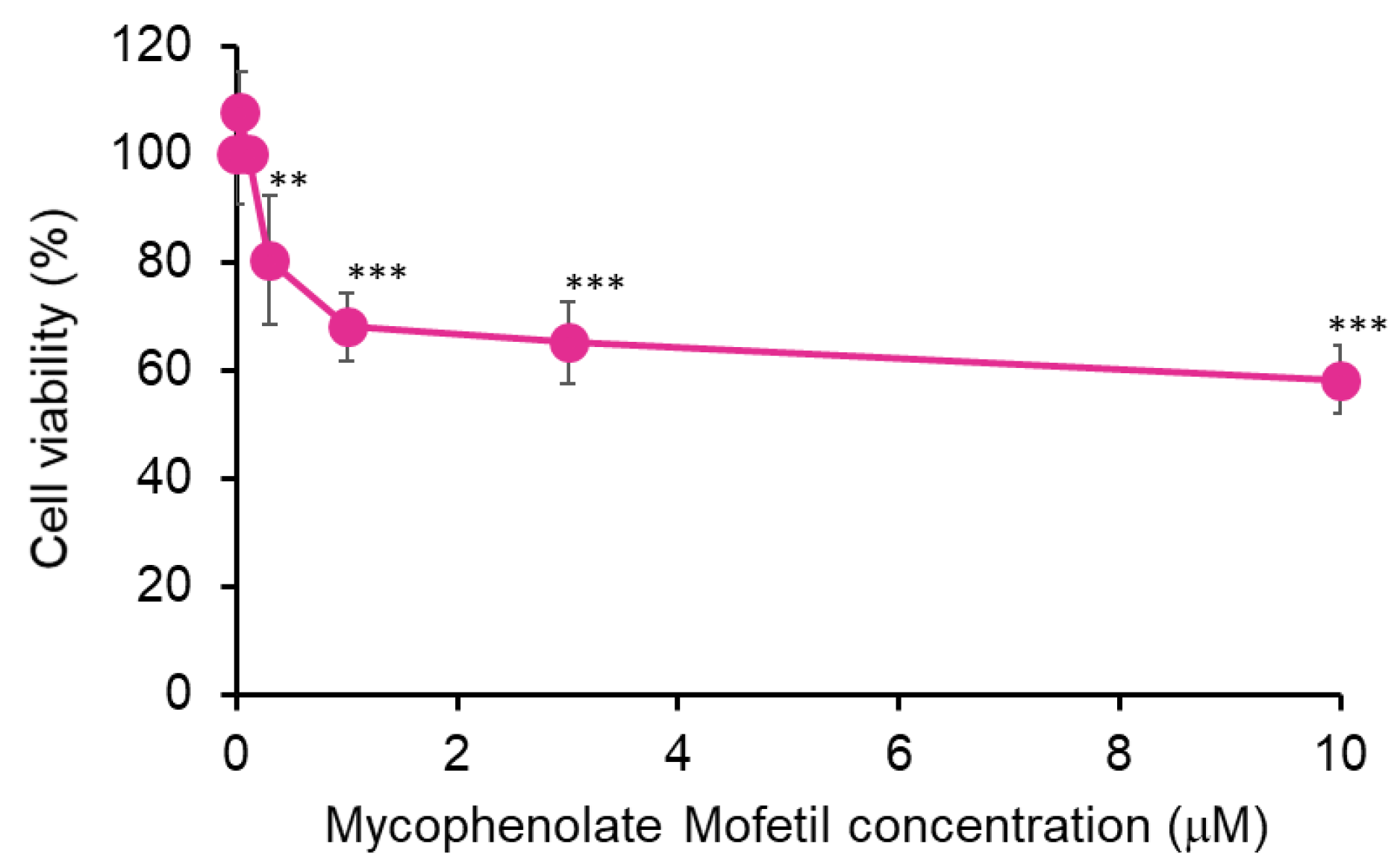

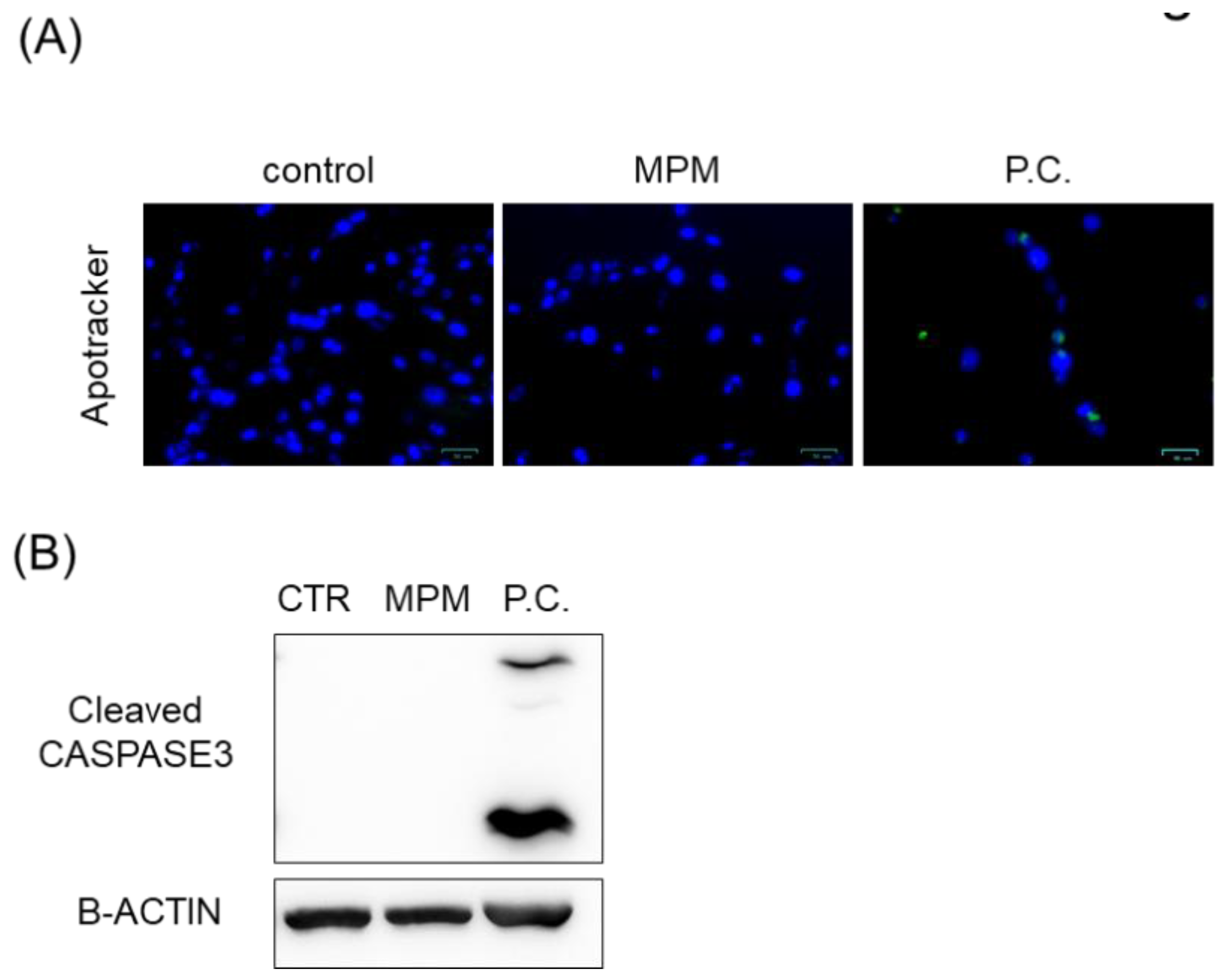

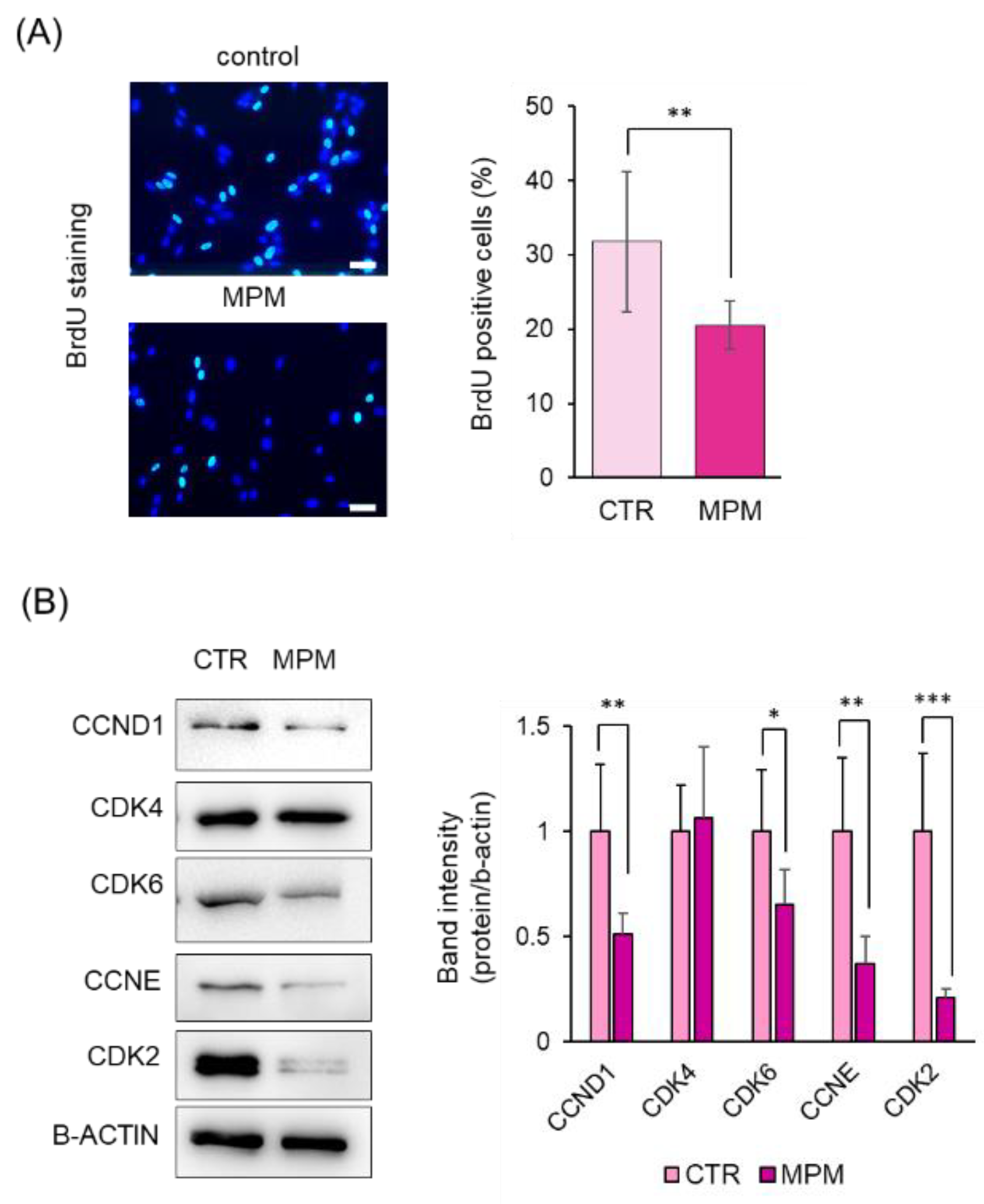

3.1. MPM Inhibits Cell Proliferation via G1 Arrest in HEPM Cells

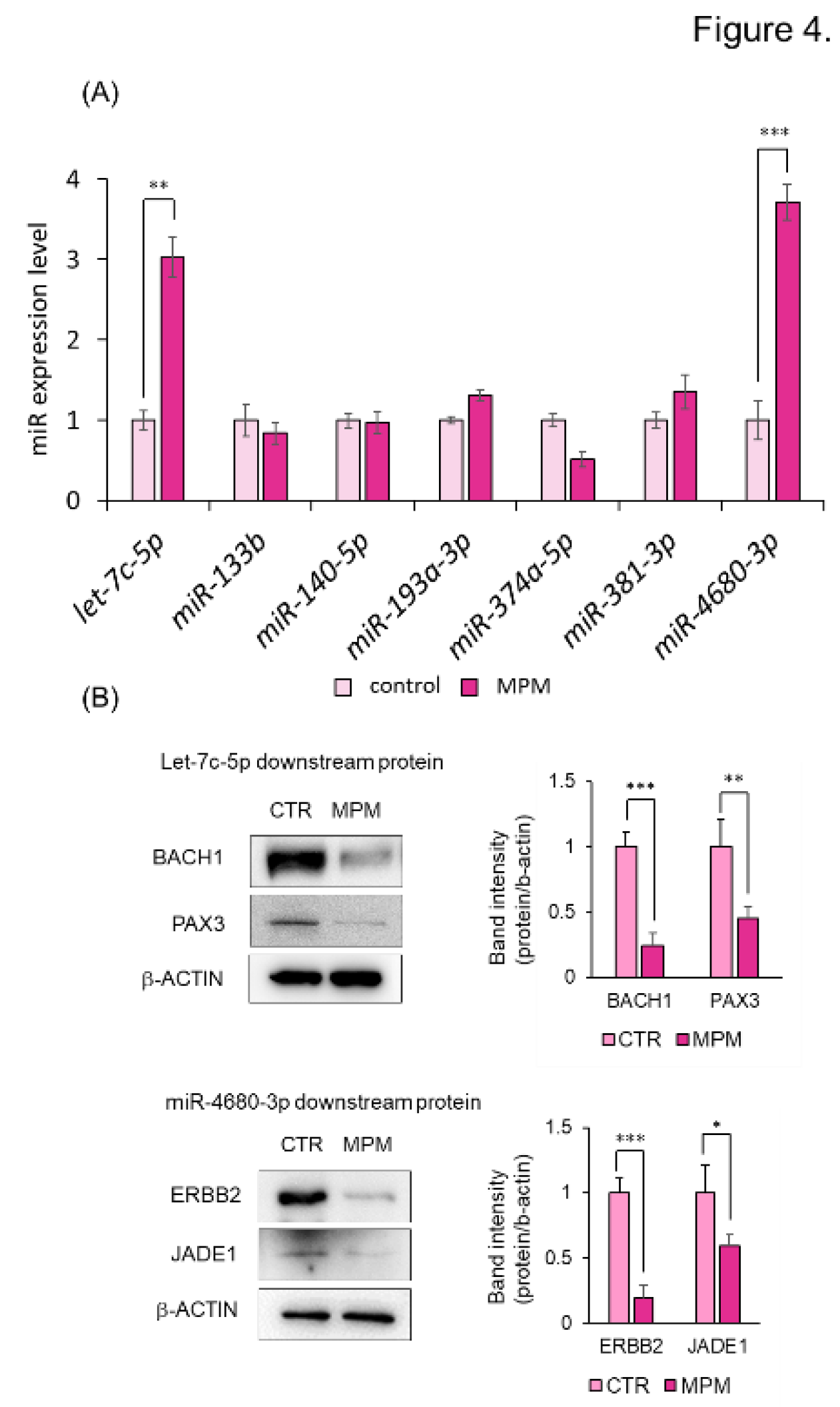

3.2. MPM Modulates let-7c-5p/miR-4680-3p and Its Downstream Genes in HEPM Cells.

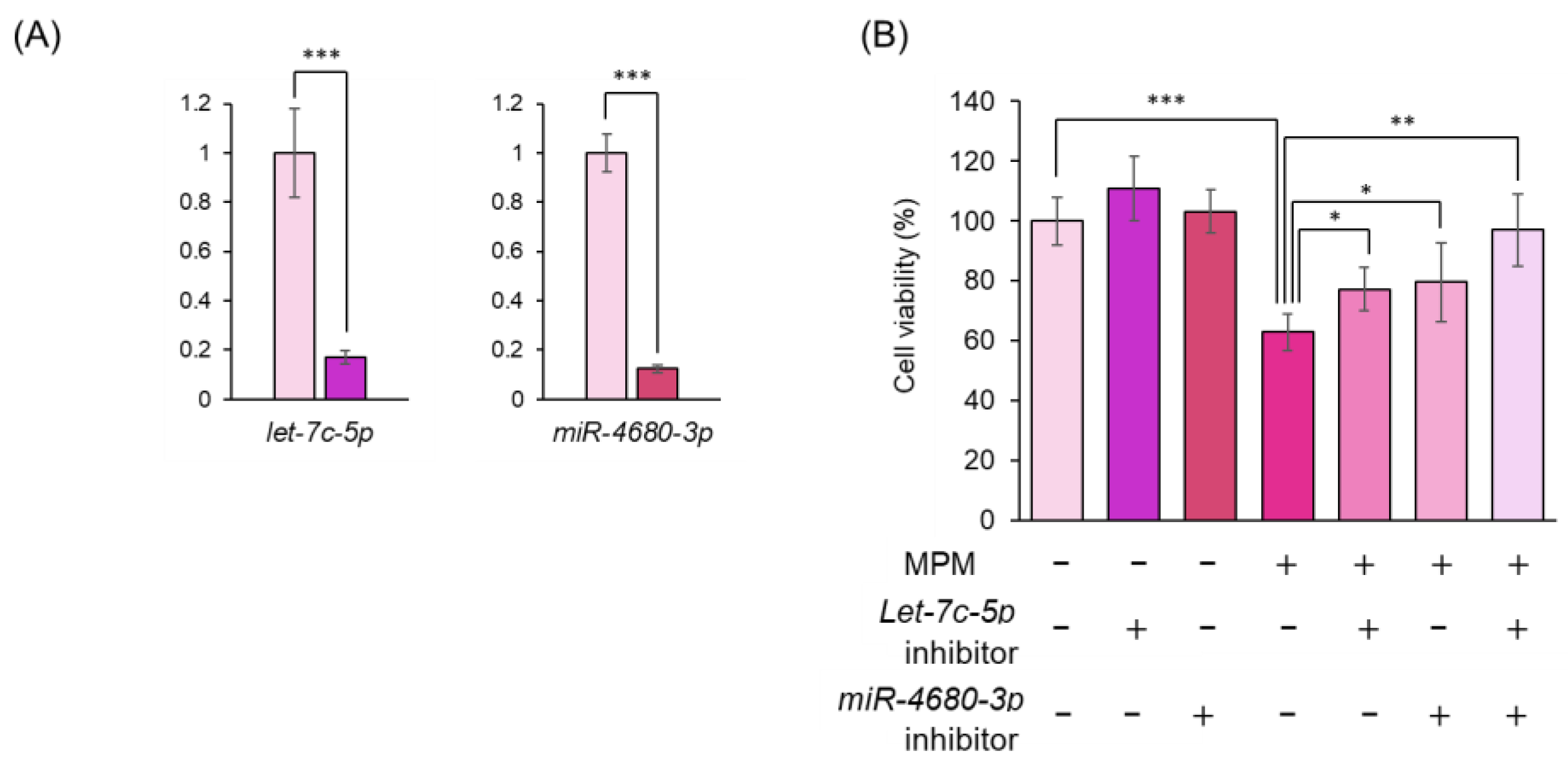

3.3. Inhibition of let-7c-5p and/or miR-4680-3p Alleviated MPM-Induced Cell Proliferation Activity in HEPM Cells.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Babai, A.; Irving, M., Orofacial Clefts: Genetics of Cleft Lip and Palate. Genes (Basel) 2023, 14, (8). [CrossRef]

- Gonseth, S.; Shaw, G. M.; Roy, R.; Segal, M. R.; Asrani, K.; Rine, J.; Wiemels, J.; Marini, N. J., Epigenomic profiling of newborns with isolated orofacial clefts reveals widespread DNA methylation changes and implicates metastable epiallele regions in disease risk. Epigenetics 2019, 14, (2), 198-213. [CrossRef]

- Martinelli, M.; Palmieri, A.; Carinci, F.; Scapoli, L., Non-syndromic Cleft Palate: An Overview on Human Genetic and Environmental Risk Factors. Front Cell Dev Biol 2020, 8, 592271. [CrossRef]

- Yoshioka, H.; Tsukiboshi, Y.; Horita, H.; Kurita, H.; Ogata, A.; Ogata, K.; Horiguchi, H., Sasa veitchii extract alleviates phenobarbital-induced cell proliferation inhibition by upregulating transforming growth factor-beta 1. Tradit Kampo Med 2024, 11 (3), 192-199. [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Bian, Z.; Torensma, R.; Von den Hoff, J. W., Biological mechanisms in palatogenesis and cleft palate. J Dent Res 2009, 88, (1), 22-33. [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Jia, P.; Mallik, S.; Fei, R.; Yoshioka, H.; Suzuki, A.; Iwata, J.; Zhao, Z., Critical microRNAs and regulatory motifs in cleft palate identified by a conserved miRNA-TF-gene network approach in humans and mice. Brief Bioinform 2020, 21, (4), 1465-1478.

- Vieira, A. R., Genetic and environmental factors in human cleft lip and palate. Front Oral Biol 2012, 16, 19-31.

- Ulschmid, C. M.; Sun, M. R.; Jabbarpour, C. R.; Steward, A. C.; Rivera-Gonzalez, K. S.; Cao, J.; Martin, A. A.; Barnes, M.; Wicklund, L.; Madrid, A.; Papale, L. A.; Joseph, D. B.; Vezina, C. M.; Alisch, R. S.; Lipinski, R. J., Disruption of DNA methylation-mediated cranial neural crest proliferation and differentiation causes orofacial clefts in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2024, 121, (3), e2317668121. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Gilboa, S. M.; Herdt, M. L.; Lupo, P. J.; Flanders, W. D.; Liu, Y.; Shin, M.; Canfield, M. A.; Kirby, R. S., Maternal exposure to ozone and PM(2.5) and the prevalence of orofacial clefts in four U.S. states. Environ Res 2017, 153, 35-40.

- Bartel, D. P., MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell 2009, 136, (2), 215-33. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Chen, X.; Li, C.; Zhao, R.; Zhang, J.; Qin, H.; Wang, M.; Su, Y.; Tang, M.; Han, L.; Sun, N., The single nucleotide polymorphism rs1814521 in long non-coding RNA ADGRG3 associates with the susceptibility to silicosis: a multi-stage study. Environ Health Prev Med 2022, 27, 5. [CrossRef]

- Schoen, C.; Aschrafi, A.; Thonissen, M.; Poelmans, G.; Von den Hoff, J. W.; Carels, C. E. L., MicroRNAs in Palatogenesis and Cleft Palate. Front Physiol 2017, 8, 165. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Sun, C.; Meng, Y.; Zhang, B.; Wang, X.; Su, Y.; Shi, L.; Zhao, E., A pilot study: Screening target miRNAs in tissue of nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate. Exp Ther Med 2017, 13, (5), 2570-2576. [CrossRef]

- Yoshioka, H.; Suzuki, A.; Iwaya, C.; Iwata, J., Suppression of microRNA 124-3p and microRNA 340-5p ameliorates retinoic acid-induced cleft palate in mice. Development 2022, 149, (9), dex200476. [CrossRef]

- Fu, C.; Lou, S.; Zhu, G.; Fan, L.; Yu, X.; Zhu, W.; Ma, L.; Wang, L.; Pan, Y., Identification of New miRNA-mRNA Networks in the Development of Non-syndromic Cleft Lip With or Without Cleft Palate. Front Cell Dev Biol 2021, 9, 631057.

- Yoshioka, H.; Jun, G.; Suzuki, A.; Iwata, J., Dexamethasone Suppresses Palatal Cell Proliferation through miR-130a-3p. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, (22) 12453. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Shen, Z.; Xing, Y.; Zhao, H.; Liang, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhong, X.; Shi, L.; Wan, X.; Zhou, J.; Tang, S., MiR-106a-5p modulates apoptosis and metabonomics changes by TGF-beta/Smad signaling pathway in cleft palate. Exp Cell Res 2020, 386, (2), 111734.

- Yoshioka, H.; Ramakrishnan, S. S.; Suzuki, A.; Iwata, J., Phenytoin Inhibits Cell Proliferation through microRNA-196a-5p in Mouse Lip Mesenchymal Cells. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, (4) 1746. [CrossRef]

- Tsukiboshi, Y.; Horita, H.; Mikami, Y.; Noguchi, A.; Yokota, S.; Ogata, K.; Yoshioka, H., Involvement of microRNA-4680-3p against phenytoin-induced cell proliferation inhibition in human palate cells. J Toxicol Sci 2024, 49, (1), 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Appel, G. B.; Radhakrishnan, J.; Ginzler, E. M., Use of mycophenolate mofetil in autoimmune and renal diseases. Transplantation 2005, 80, (2 Suppl), S265-71. [CrossRef]

- Perez-Aytes, A.; Marin-Reina, P.; Boso, V.; Ledo, A.; Carey, J. C.; Vento, M., Mycophenolate mofetil embryopathy: A newly recognized teratogenic syndrome. Eur J Med Genet 2017, 60, (1), 16-21. [CrossRef]

- Coscia, L. A.; Armenti, D. P.; King, R. W.; Sifontis, N. M.; Constantinescu, S.; Moritz, M. J., Update on the Teratogenicity of Maternal Mycophenolate Mofetil. J Pediatr Genet 2015, 4, (2), 42-55. [CrossRef]

- Tjeertes, I. F.; Bastiaans, D. E.; van Ganzewinkel, C. J.; Zegers, S. H., Neonatal anemia and hydrops fetalis after maternal mycophenolate mofetil use. J Perinatol 2007, 27, (1), 62-4. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Song, T.; Ronde, E. M.; Ma, G.; Cui, H.; Xu, M., The important role of MDM2, RPL5, and TP53 in mycophenolic acid-induced cleft lip and palate. Medicine (Baltimore) 2021, 100, (21), e26101. [CrossRef]

- Tominaga, S.; Yoshioka, H.; Yokota, S.; Tsukiboshi, Y.; Suzui, M.; Nagai, M.; Hara, H.; Maeda, T.; Miura, N., Copper-induced diurnal hepatic toxicity is associated with Cry2 and Per1 in mice. Environ Health Prev Med 2023, 28, 78. [CrossRef]

- Yoshioka, H.; Tominaga, S.; Suzui, M.; Shinohara, Y.; Maeda, T.; Miura, N., Involvement of Npas2 and Per2 modifications in zinc-induced acute diurnal toxicity in mice. J Toxicol Sci 2022, 47, (12), 547-553. [CrossRef]

- Yoshioka, H.; Tominaga, S.; Amano, F.; Wu, S.; Torimoto, S.; Moriishi, T.; Tsukiboshi, Y.; Yokota, S.; Miura, N.; Inagaki, N.; Matsushita, Y.; Maeda, T., Juzentaihoto alleviates cisplatin-induced renal injury in mice. Tradit Kampo Med 2024, 11, (2), 147-155. [CrossRef]

- Yoshioka, H.; Wu, S.; Moriishi, T.; Tsukiboshi, Y.; Yokota, S.; Miura, N.; Yoshikawa, M.; Inagaki, N.; Matsushita, Y.; Nakao, M., Sasa veitchii extract alleviates nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in methionine–choline deficient diet-induced mice by regulating peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha. Tradit Kampo Mede 2023, 10, (3), 259-268. [CrossRef]

- Yoshioka, H.; Yokota, S.; Tominaga, S.; Tsukiboshi, Y.; Suzui, M.; Shinohara, Y.; Yoshikawa, M.; Sasaki, H.; Sasaki, N.; Maeda, T.; Miura, N., Involvement of Bmal1 and Clock in Bromobenzene Metabolite-Induced Diurnal Renal Toxicity. Biol Pharm Bull 2023, 46, (6), 824-829. [CrossRef]

- Tsukiboshi, Y.; Noguchi, A.; Horita, H.; Mikami, Y.; Yokota, S.; Ogata, K.; Yoshioka, H., Let-7c-5p associate with inhibition of phenobarbital-induced cell proliferation in human palate cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2024, 696, 149516. [CrossRef]

- Dhulipala, V. C.; Welshons, W. V.; Reddy, C. S., Cell cycle proteins in normal and chemically induced abnormal secondary palate development: a review. Hum Exp Toxicol 2006, 25, (11), 675-82. [CrossRef]

- Smane, L.; Pilmane, M.; Akota, I., Apoptosis and MMP-2, TIMP-2 expression in cleft lip and palate. Stomatologija 2013, 15, (4), 129-34.

- Suzuki, A.; Li, A.; Gajera, M.; Abdallah, N.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, Z.; Iwata, J., MicroRNA-374a, -4680, and -133b suppress cell proliferation through the regulation of genes associated with human cleft palate in cultured human palate cells. BMC Med Genomics 2019, 12, (1), 93. [CrossRef]

- Yoshioka, H.; Ramakrishnan, S. S.; Shim, J.; Suzuki, A.; Iwata, J., Excessive All-Trans Retinoic Acid Inhibits Cell Proliferation Through Upregulated MicroRNA-4680-3p in Cultured Human Palate Cells. Front Cell Dev Biol 2021, 9, 618876. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, F.; Eckardt, K.; Shakibaei, M.; Glander, P.; Stahlmann, R., Effects of mycophenolic acid alone and in combination with its metabolite mycophenolic acid glucuronide on rat embryos in vitro. Arch Toxicol 2013, 87, (2), 361-70. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L. L.; Liu, M. H.; Li, J. Y.; He, Z. H.; Li, H.; Shen, N.; Wei, P.; He, M. F., Mycophenolic Acid-Induced Developmental Defects in Zebrafish Embryos. Int J Toxicol 2016, 35, (6), 712-718. [CrossRef]

- Sherr, C. J.; Roberts, J. M., Living with or without cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases. Genes Dev 2004, 18, (22), 2699-711. [CrossRef]

- Fassl, A.; Geng, Y.; Sicinski, P., CDK4 and CDK6 kinases: From basic science to cancer therapy. Science 2022, 375, (6577), eabc1495. [CrossRef]

- Ettl, T.; Schulz, D.; Bauer, R. J., The Renaissance of Cyclin Dependent Kinase Inhibitors. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14, (2). [CrossRef]

- Lukasik, P.; Zaluski, M.; Gutowska, I., Cyclin-Dependent Kinases (CDK) and Their Role in Diseases Development-Review. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, (6), 2935. [CrossRef]

- Ohtsubo, M.; Theodoras, A. M.; Schumacher, J.; Roberts, J. M.; Pagano, M., Human cyclin E, a nuclear protein essential for the G1-to-S phase transition. Mol Cell Biol 1995, 15, (5), 2612-24. [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y. M.; Sicinski, P., Targeting cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases in cancer: lessons from mice, hopes for therapeutic applications in human. Cell Cycle 2006, 5, (18), 2110-4.

- Huang, J.; Zheng, L.; Sun, Z.; Li, J., CDK4/6 inhibitor resistance mechanisms and treatment strategies (Review). Int J Mol Med 2022, 50, (4), 128.

- Garland, M. A.; Sun, B.; Zhang, S.; Reynolds, K.; Ji, Y.; Zhou, C. J., Role of epigenetics and miRNAs in orofacial clefts. Birth Defects Res 2020, 112, (19), 1635-1659. [CrossRef]

- Iwata, J., Gene-Environment Interplay and MicroRNAs in Cleft Lip and Cleft Palate. Oral Sci Int 2021, 18, (1), 3-13. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Bai, Y.; Li, H.; Greene, S. B.; Klysik, E.; Yu, W.; Schwartz, R. J.; Williams, T. J.; Martin, J. F., MicroRNA-17-92, a direct Ap-2alpha transcriptional target, modulates T-box factor activity in orofacial clefting. PLoS Genet 2013, 9, (9), e1003785.

- Li, L.; Meng, T.; Jia, Z.; Zhu, G.; Shi, B., Single nucleotide polymorphism associated with nonsyndromic cleft palate influences the processing of miR-140. Am J Med Genet A 2010, 152A, (4), 856-62. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, D.; Yu, X.; Zhu, W.; Fu, C.; Lou, S.; Fan, L.; Ma, L.; Wang, L.; Pan, Y., Variants in miRNA regulome and their association with the risk of nonsyndromic orofacial clefts. Epigenomics 2020, 12, (13), 1109-1121. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C. D.; Esquela-Kerscher, A.; Stefani, G.; Byrom, M.; Kelnar, K.; Ovcharenko, D.; Wilson, M.; Wang, X.; Shelton, J.; Shingara, J.; Chin, L.; Brown, D.; Slack, F. J., The let-7 microRNA represses cell proliferation pathways in human cells. Cancer Res 2007, 67, (16), 7713-22.

- Fu, X.; Mao, X.; Wang, Y.; Ding, X.; Li, Y., Let-7c-5p inhibits cell proliferation and induces cell apoptosis by targeting ERCC6 in breast cancer. Oncol Rep 2017, 38, (3), 1851-1856. [CrossRef]

- Luo, K.; Qin, Y.; Ouyang, T.; Wang, X.; Zhang, A.; Luo, P.; Pan, X., Let-7c-5p Regulates CyclinD1 in Fluoride-Mediated Osteoblast Proliferation and Activation. Toxicol Sci 2021, 182, (2), 275-287. [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Chen, H.; Guo, Z.; Zhou, X., Circular RNA circ0007360 Attenuates Gastric Cancer Progression by Altering the miR-762/IRF7 Axis. Front Cell Dev Biol 2022, 10, 789073.

- Valinezhad Orang, A.; Safaralizadeh, R.; Kazemzadeh-Bavili, M., Mechanisms of miRNA-Mediated Gene Regulation from Common Downregulation to mRNA-Specific Upregulation. Int J Genomics 2014, 2014, 970607.

- Zhang, X.; Guo, J.; Wei, X.; Niu, C.; Jia, M.; Li, Q.; Meng, D., Bach1: Function, Regulation, and Involvement in Disease. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2018, 2018, 1347969.

- Liu, C.; Yu, J.; Liu, B.; Liu, M.; Song, G.; Zhu, L.; Peng, B., BACH1 regulates the proliferation and odontoblastic differentiation of human dental pulp stem cells. BMC Oral Health 2022, 22, (1), 536. [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Li, J.; Engleka, K. A.; Zhou, B.; Lu, M. M.; Plotkin, J. B.; Epstein, J. A., Persistent expression of Pax3 in the neural crest causes cleft palate and defective osteogenesis in mice. J Clin Invest 2008, 118, (6), 2076-87. [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.; Huang, W.; Sun, B.; Zhong, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, Z.; Lin, J.; Chen, F., A Novel PAX3 Variant in a Chinese Pedigree with Nonsyndromic Cleft Lip With or Without Palate. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers 2021, 25, (12), 749-756. [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Yu, D., Molecular mechanisms of erbB2-mediated breast cancer chemoresistance. Adv Exp Med Biol 2007, 608, 119-29.

- Kirouac, D. C.; Du, J.; Lahdenranta, J.; Onsum, M. D.; Nielsen, U. B.; Schoeberl, B.; McDonagh, C. F., HER2+ Cancer Cell Dependence on PI3K vs. MAPK Signaling Axes Is Determined by Expression of EGFR, ERBB3 and CDKN1B. PLoS Comput Biol 2016, 12, (4), e1004827.

- Havasi, A.; Haegele, J. A.; Gall, J. M.; Blackmon, S.; Ichimura, T.; Bonegio, R. G.; Panchenko, M. V., Histone acetyl transferase (HAT) HBO1 and JADE1 in epithelial cell regeneration. Am J Pathol 2013, 182, (1), 152-62. [CrossRef]

- Borgal, L.; Habbig, S.; Hatzold, J.; Liebau, M. C.; Dafinger, C.; Sacarea, I.; Hammerschmidt, M.; Benzing, T.; Schermer, B., The ciliary protein nephrocystin-4 translocates the canonical Wnt regulator Jade-1 to the nucleus to negatively regulate beta-catenin signaling. J Biol Chem 2012, 287, (30), 25370-80.

- Lu, T. X.; Rothenberg, M. E., MicroRNA. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2018, 141, (4), 1202-1207.

| Antibody name |

Vendor | Catalog number |

Concentration |

|---|---|---|---|

| -ACTIN | Medical & Biological Laboratories | M177-3 | 1:3000 |

| BAX | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | sc-20067 | 1:1000 |

| Cleaved CASPASE-3 | Cell Signaling Technology | 9661 | 1:3000 |

| CCND1 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | sc-8396 | 1:500 |

| CCNE | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | sc-377100 | 1:1000 |

| CDK2 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | sc-6248 | 1:1000 |

| CDK4 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | sc-56277 | 1:1000 |

| CDK6 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | sc-53638 | 1:500 |

| BACH1 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | sc-271211 | 1:500 |

| PAX3 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | sc-376204 | 1:500 |

| ERBB2 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | sc-393712 | 1:1000 |

| JADE1 | Proteintech Japan | 28472-1-AP | 1:2000 |

| Rabbit IgG HRP | Cell Signaling Technology | 7074 | 1:10000 |

| Mouse IgG HRP | Cell Signaling Technology | 7976 | 1:10000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).