1. Introduction

Despite the progressive increase in the number of physicians in Brazil in relation to the general population, there is still a greater concentration of professionals in more populated regions with a high human development index. The inequality becomes even greater when we evaluate the rates related to the distribution of specialist physicians. Of the 5,565 Brazilian municipalities, only 504 (9.1%) have dermatologists [

1]. Dermatology is among the specialties most referred by general practitioners in Brazil, and the waiting time for referral is longer than in many countries [

2].

Skin cancer is highly prevalent and is the most common type of cancer worldwide [

3]. In the 2023-2025 triennium, 220,490 new cases of non-melanoma skin cancer were estimated in Brazil [

4]. Skin cancer is one of the most referred and urgent dermatological diseases, especially melanoma, which represents only 3% of cases but has a high mortality rate [

5]. Additionally, it is important to highlight that most of the Brazilian territory has a tropical climate, and the increasing rate of global warming may contribute to greater and more prolonged exposure to sunlight, with a potential risk of increased incidence of skin cancer in the coming decades.

On the other hand, patients with non-malignant lesions that do not require immediate consultation with dermatologists could be treated by a general practitioner, reducing waiting lists for evaluation by a specialist. However, patients do not know the type of lesion they have, and when they seek care from specialists, they overload the health system, delaying the treatment of priority cases. In this context, it would be desirable to use tools to support the evaluation of skin lesions to help general practitioners in the triage of their patients, especially those with suspicious lesions that require urgent care.

In the practice of dermatology, it is common to capture images of the skin to record the current condition and follow up on the lesions. These images can be systematically stored, creating a fundamental database for the development of telemedicine and artificial intelligence (AI) tools [

6]. Currently, several initiatives are combining technology for the evaluation of skin lesions [

7,

8,

9].

The objective of this study is to evaluate the contribution of an application with an AI algorithm in the early diagnosis of potentially malignant skin lesions and its impact on the agility of treatment in a population served by the public health system of a municipality in Brazil.

2. Methods

This cross-sectional observational study evaluated the diagnosis of skin lesions in patients treated at the dermatology outpatient clinic of the Jundiaí School of Medicine (FMJ), SP, Brazil, between July 2022 to March 2023. The study was approved by the FMJ Ethics Committee [CAAE: 55197422.0.0000.5412; Feb. 2022]. All participants included signed the Free and Informed Consent Form before their data was collected. Participants' data were coded to avoid inadvertent exposure, thus ensuring the anonymization and absolute confidentiality of the information obtained, in accordance with the Brazilian General Data Protection Law.

Patients were included if they were (i) between 18 and 100 years old, (ii) referred by primary care services, (iii) had an appointment scheduled within the period stipulated for data collection at the dermatology outpatient clinic of FMJ, and (iv) had at least one eligible skin lesion in the day of the consultation. Patients who (i) missed their appointment, (ii) did not have eligible lesions, or (iii) did not accept the terms of the study were excluded.

The tool used in this study is an AI model integrated into an application, available on smartphones. Clinical images of skin lesions were recorded using iPhone, Motorola and Samsung smartphones. Image capture was standardized, with the device positioned at a 30-degree angle to the skin, at 5 cm from the lesion, to avoid shadows and loss of focus. After image acquisition, each photo was submitted to an AI-based application, which classified the image into one of the following groups: 1: Pigmentation disorders and superficial infections; 2: Inflammatory conditions and eczema; 3: Atypical or malignant lesions or 4: Benign lesions, cysts, scars and calluses.

The final model has four supervised AI categories, based on deep neural network algorithms. The models were previously trained on a dataset containing 5,267 images of skin lesions, achieving a diagnostic accuracy of 79%.

The types of skin lesions diagnosed, and the demographic data of the participants were described to characterize the population included in the study. The results obtained by the evaluators (algorithm and dermatologists) were compared using the Kappa index score. For analysis purposes, the gold standard diagnosis for suspicious malignant lesions was defined by the biopsy result. For benign lesions, where dermatologists deemed a biopsy unnecessary, the clinical diagnosis was used as the reference standard.

The sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, positive predictive value and negative predictive value were calculated based on the agreement of the AI model with the biopsy result. The software used for statistical analyzes was the SPSS 22.0, and a value of p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Data on the interval between the primary care consultation and the evaluation by the specialist, as well as the time between the specialist's diagnosis and the biopsy of lesions suspected of malignancy were also collected.

3. Results

During the study period, 2,928 patients were scheduled, and 492 participants were eligible. Of these, 59.1% were over 60 years, 53.9% were female, 33.9% had 0 to 4 years of education, and 83.1% self-identified as white (

Table 1).

Of the 492 participants, a total of 1,615 images of skin lesions were collected (approximately 3 different lesions per patient). After excluding blurry images or images that were difficult to read by the application, 1,349 images were eligible, distributed as follows, according to the gold standard diagnosis: Group 1: Pigmentation disorders and superficial infections: 82 (6.1%); Group 2: Inflammatory conditions and eczema: 97 (7.2%); Group 3: Atypical or malignant lesions: 342 (25.4%); Group 4: Benign lesions, cysts, scars and calluses: 828 (61.4%).

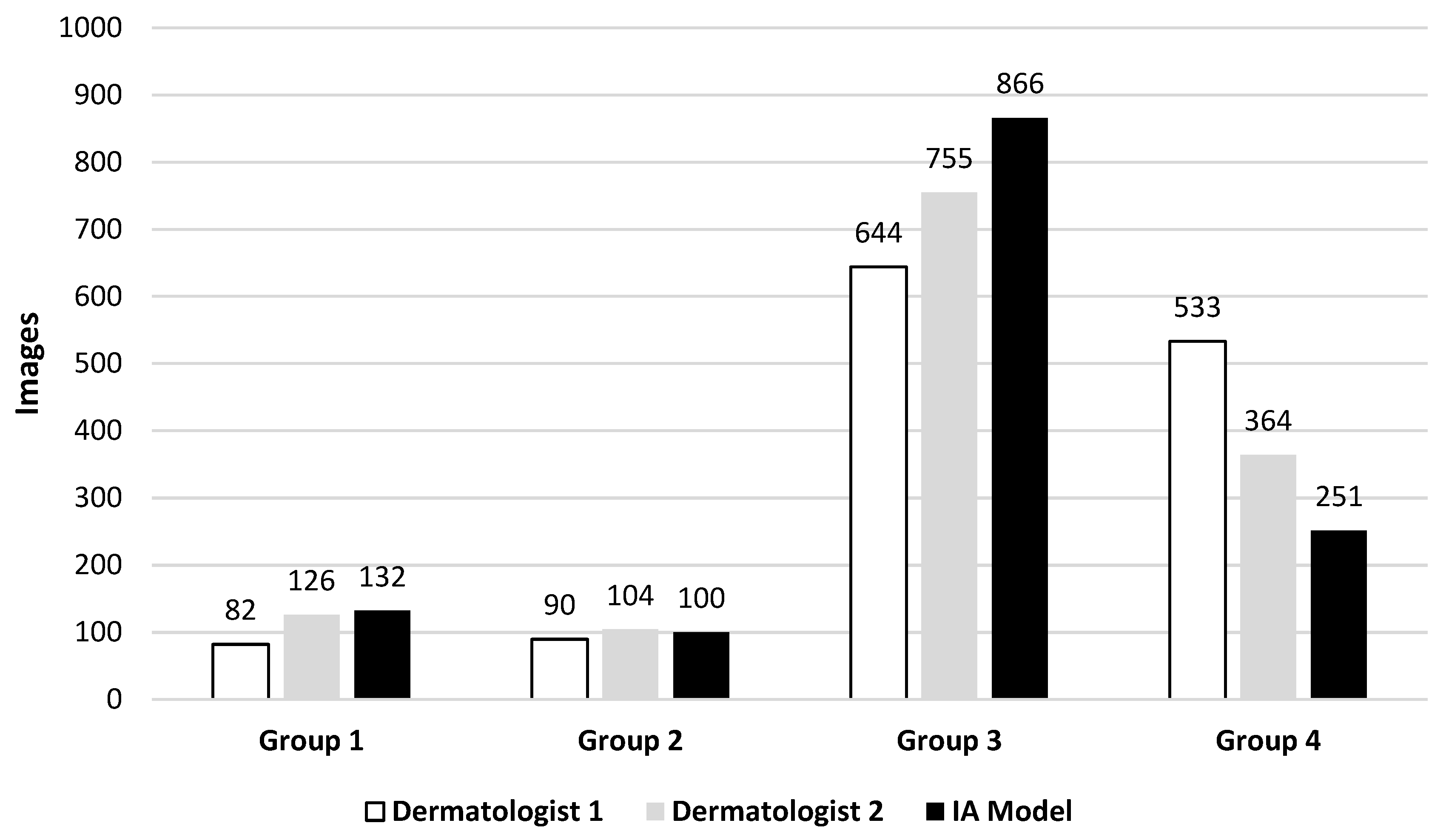

All images were submitted for evaluation by two dermatologists in blinded analysis. Dermatologist 1 classified 82 images as group 1, 90 as group 2, 644 as group 3, and 533 as group 4. Dermatologist 2 classified 126, 104, 755, and 364 for these groups respectively. AI Model classified 132, 100, 866, and 251 images for these groups respectively (

Figure 1).

For analysis, groups 1, 2, and 4 were grouped as “Benign". Dermatologist 1 classified 705 images as Benign and 644 as Atypical/Malignant, Dermatologist 2 classified 594 as Benign and 755 as Atypical/Malignant, while AI model classified 483 as Benign and 866 as Atypical/Malignant.

The statistical analysis, based on the calculation of Cohen's Kappa, showed reasonable but significant agreement between AI model vs. Dermatologist 1 (K1= 0.304; p< 0.001) and AI model vs. Dermatologist 2 (K2= 0.271; p< 0.001), in contrast to the substantial agreement between Dermatologist 1 vs. Dermatologist 2 (K= 0.598; p< 0.001).

Overall, 320 lesions were submitted to biopsy, of which 259 (80.9%) were confirmed as atypical/malignant and 61 (19.1%) classified as benign. For the final diagnosis of atypical/malignant lesion confirmed by biopsy, the AI model presented a diagnostic sensitivity of 89.2%, specificity of 34.4%, accuracy of 78.8%, positive predictive value of 85.2% and negative predictive value of 42.9% (

Table 2).

The mean time between primary care consultation and specialist evaluation was 188 ± 96 days, and the mean time between specialist diagnosis and biopsy of suspected atypical/malignant lesions was 25 ± 10 days.

4. Discussion

Skin cancer is the most prevalent tumor in the world and is one of the most frequently referred diseases with the greatest diagnostic and therapeutic urgency [

3,

4,

5]. In dermatology, artificial intelligence has assumed an important role in supporting the diagnosis of skin neoplasms [

10,

11]. Some studies have even demonstrated the superiority of AI in the diagnosis of skin lesions compared to evaluation by dermatologists [

12,

13,

14]. Eapen, Han, Shrivastav and Shen also highlight the use of AI in several areas of dermatology, such as in the diagnosis of acne vulgaris and in the identification of onychomycosis [

15,

16,

17,

18].

Freeman et al. [

10] conducted a comprehensive systematic review, analyzing nine studies that investigated six applications designed for the evaluation of skin lesions. The studies addressed a diverse range of lesions, with sample sizes ranging from 15 to 199 lesions. Predominantly focused on suspicious lesions, these studies revealed a disparity in results, highlighting variations in both the sensitivity and specificity of the algorithms evaluated. The findings indicate that, in general, the performance of these algorithms did not meet expectations, highlighting the need for advances and improvements in the application of these tools.

In our study, the classification of images, performed by both the artificial intelligence algorithm and the dermatologists, revealed reasonable agreement by the Kappa index score. In contrast, the agreement between the experts was considered substantial. Our results of evaluating AI in the diagnosis of atypical/malignant lesions (sensitivity: 86.5%; specificity: 43.5%; accuracy: 54.6%) are in line with other studies that highlight the high sensitivity of the algorithms [

19,

20].

Our study also found that the estimated mean time between a primary care consultation in our city's health system and the evaluation by a specialist dermatologist was 188 ± 96 days, a time considered long. This is certainly due to the high demand for dermatology consultations in the public health system of most Brazilian cities. However, the time between the specialist's diagnosis and the biopsy of atypical/malignant lesions was 25 ± 10 days, which is considered optimal. In this sense, it is reasonable to speculate that an AI algorithm that assists non-specialist primary care physicians, when suspecting potentially malignant lesions, could expedite the referral of patients to a dermatologist, thus reducing the time between diagnosis and treatment of lesions suspected of being malignant.

Some limitations in our study should be considered, such as the potential selection bias due to the sample being composed mainly of individuals over 60 years old, female, with low education levels, and self-declared white. Future work recommends expanding the scope of the data source, considering the diversity of phototypes and assessing the quality of images in different contexts. Overcoming these limitations requires collaborative efforts and a significant expansion of the database, aiming to incorporate a broader spectrum of clinical cases.

Developing an artificial intelligence model capable of covering all clinical conditions is challenging, requiring the choice of focusing on specific groups of diseases. This approach becomes even more complex due to the need to ensure representativeness, both in terms of the diversity of International Classifications of Diseases and in considering skin variability in different geographic and ethnic contexts.

In Brazil, the commercialization of artificial intelligence algorithms is still in the regulatory process. Conducting robust clinical studies, with a particular emphasis on prospective research, is essential to validate the effectiveness of these applications in real-world scenarios. In the process of validating algorithms, dermatologists play an active role, and despite the increasing ease of image identification, challenges persist, such as the lack of standardization in the capture, processing, transmission and storage of dermatological images. The absence of a uniform standard for position, illumination and resolution results in the exclusion of many images due to low quality. In this sense, the continuous need to expand databases, promote collaboration between dermatology specialists and data scientists, and improve existing algorithms is highlighted.

As we advance in technological frontiers, we envision a future in which skin lesion screening applications will play a more prominent role in the early detection of potentially malignant lesions, becoming fully integrated into clinical routine. Training healthcare professionals in artificial intelligence is a crucial step in helping them understand both the advantages and limitations of these technologies, which in turn will enable the education of the population about this innovative diagnostic tool.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, the AI application used in this study achieved high sensitivity, with the potential to screen skin lesions of different etiologies. However, new studies with a larger population should be encouraged to improve this tool. Considering our project, AI-powered decision support tools could empower primary care physicians to deliver faster and more precise diagnoses, expedite referrals for suspected malignant skin lesions, and reduce delays in treatment.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Author Contributions

MTS, JASLBF and EM contributed to data collection. MJB, LEPB, KLO and EM contributed to the conception, design, analysis and writing. LOC, IC and ANOM contributed to the data analysis and review of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Jundiaí School of Medicine Ethics Committee [CAAE: 55197422.0.0000.5412].

Informed Consent Statement

All participants included signed the Free and Informed Consent Form before their data was collected.

Data Availability Statement

All data are incorporated into the article and its online supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the Scientific Committee and the staff of the Jundiaí School of Medicine for their support in carrying out this work.

References

- Schmidt, S.M.; Miot, H.A.; Luz, F.B.; Sousa, M.A.J.; Palma, S.L.L.; Sanches Junior, J.A. Demographics and spatial distribution of the Brazilian dermatologists. An Bras Dermatol. 2018, 93, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebolho, R.C.; Neto, P.P.; Pedebôs, L.A.; Garcia, L.P.; Vidor, A.C. Do family doctors refer less? Impact of FCM training on the rate of PHC referrals. Ciencia e Saude Coletiva. 2021, 26, 1265–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, F.M.; Carmo, J.A.; do Cunha, L.D.; Martins, I.M.L.; Gon A dos, S.; Caldeira, A.P. Development and validation of an instrument to assess the knowledge of general practitioners and pediatricians about photoprotection and solar radiation. An Bras Dermatol. 2019, 94, 532–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health. 2020 Estimate. Incidence of Cancer in Brazil. Available online: https://www.inca.gov.br/sites/ufu.sti.inca.local/files/media/document/estimativa-2020-incidencia-de-cancer-no-brasil.pdf.

- Brown, R.V.S.; Hillesheim, D.; Tomasi, Y.T.; Nunes, D.H. Mortality from malignant skin melanoma in elderly Brazilians: 2001 to 2016. An Bras Dermatol. 2021, 96, 34–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okita, A.L.; Molina Tinoco, L.J.; Patatas, O.H.G.; Guerreiro, A.; Criado, P.R.; Gabbi, T.V.B.; et al. Use of Smartphones in Telemedicine: Comparative Study between Standard and Teledermatological Evaluation of High-Complex Care Hospital Inpatients. Telemedicine and e-Health 2016, 22, 755–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hogarty, D.T.; Su, J.C.; Phan, K.; Attia, M.; Hossny, M.; Nahavandi, S.; et al. Artificial Intelligence in Dermatology - Where We Are and the Way to the Future: A Review. Am J of Clin Dermatol. 2020, 21, 41–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, F.M.; Pannebakker, M.M.; Barclay, M.E.; Mills, K.; Saunders, C.L.; Murchie, P.; et al. Effect of a Skin Self-monitoring Smartphone Application on Time to Physician Consultation among Patients with Possible Melanoma: A Phase 2 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2020, 3, e200001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marek, A.J.; Chu, E.Y.; Ming, M.E.; Khan, Z.A.; Kovarik, C.L. Impact of a smartphone application on skin self-examination rates in patients who are new to total body photography: A randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018, 79, 564–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman K, Dinnes J, Chuchu N, Takwoingi Y, Bayliss SE, Matin RN, et al. Algorithm based smartphone apps to assess risk of skin cancer in adults: systematic review of diagnostic accuracy studies. BMJ. 2020, 368, m127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martorell, A.; Martin-Gorgojo, A.; Ríos-Viñuela, E.; Rueda-Carnero, J.M.; Alfageme, F.; Taberner, R. Artificial Intelligence in Dermatology: A Threat or an Opportunity? Actas Dermosifiliograf. 2022, 113, 30–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.X.; Shen, C.B.; Xue, K.; Shen, X.; Jing, Y.; Wang, Z.Y.; et al. Artificial intelligence in dermatology: Past, present, and future. Chin Med J (Engl). 2019, 132, 2017–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esteva, A.; Kuprel, B.; Novoa, R.A.; Ko, J.; Swetter, S.M.; Blau, H.M.; et al. Dermatologist-level classification of skin cancer with deep neural networks. Nature. 2017, 542, 115–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujisawa, Y.; Otomo, Y.; Ogata, Y.; Nakamura, Y.; Fujita, R.; Ishitsuka, Y.; et al. Deep learning -based, computer -aided classifier developed with a small dataset of clinical images surpasses board -certified dermatologists in skin tumor diagnosis. Br J Dermatol. 2019, 180, 373–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eapen, B. Artificial intelligence in dermatology: A practical introduction to a paradigm shift. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2020, 11, 881–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.S.; Kim, M.S.; Lim, W.; Park, G.H.; Park, I.; Chang, S.E. Classification of the Clinical Images for Benign and Malignant Cutaneous Tumors Using a Deep Learning Algorithm. J Invest Dermatol. 2018, 138, 1529–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrivastava, V.K.; Londhe, N.D.; Sonawane, R.S.; Suri, J.S. A novel and robust Bayesian approach for segmentation of psoriasis lesions and its risk stratification. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2017, 150, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Zhang, J.; Yan, C.; Zhou, H. An Automatic Diagnosis Method of Facial Acne Vulgaris Based on Convolutional Neural Network. Sci Rep. 2018, 8, 5839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Udrea, A.; Mitra, G.D.; Costea, D.; Noels, E.C.; Wakkee, M.; Siegel, D.M.; et al. Accuracy of a smartphone application for triage of skin lesions based on machine learning algorithms. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020, 34, 648–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A.T.; Xiong, M.; Pfau, J.; Keiser, M.J.; Wei, M.L. Artificial Intelligence in Dermatology: A Primer. J Invest Dermatol. 2020, 140, 1504–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).