1. Introduction

Malaria is a dangerous disease spread by mosquitoes. On average, the malaria virus is more common worldwide in tropical climates. With over 200 million cases internationally and more than 400,000 fatalities annually, malaria represents a colossal danger to public health. In 2021, the WHO African Region accounted for around 95% of malaria cases and 96% of malaria-related deaths. Over half of malaria deaths globally occurred in four African countries: Nigeria (31.3%), the Democratic Republic of the Congo (12.6%), the United Republic of Tanzania (4.1%), and Niger (3.9%) [

1]. Vulnerable groups include newborns, pregnant women, and visitors. Consequently, information technology may be heavily exploited in areas lacking specialist workers and infrastructure. In addition, as the rate of errors in traditional approaches is higher, the classification analysis implemented may be utilized to reduce human stress and aid in making an accurate diagnosis [

2]. Few techniques are used to detect malaria disease such as rapid diagnostics test (RDT) [

3], clinical diagnosis, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) [

4], and microscopic diagnosis. Conventional diagnosis procedures such as clinical diagnosis and PCR depend on human abilities. Currently, RDT and microscopic diagnosis are the most efficient approaches for reducing malaria [

5]. Implementing modern information technology plays a vital role in the fight against this fatal and widely spread illness. Specifically, deep learning is used due to its high accuracy in classifying huge quantities of data [

6].

Malaria is a dangerous illness that affects millions globally, particularly in impoverished nations. Early identification and treatment are crucial to avoid complications and lower mortality rates. Many studies on the malaria virus have been carried out in the literature using various deep learning models and architectures. Using the transfer learning method, Vijayalakshmi et al. proposed a novel neural network model to identify infectious malaria parasites. They combined the support vector machine with the VGG network to develop a novel neural network model. They claimed that the classification accuracy of their created network was 93.1% [

7]. Pan et al. observed that a deep convolutional network based on LeNet-5 achieves good classification accuracy for automated malaria detection. They investigated the performance impact of the data set by running their algorithm on data sets with varying amounts of images [

8].

Models that were used in a study by Rajaraman et al. included AlexNet, VGG16, Xception, ResNet5, and DenseNet121. They claimed to have identified the layers of the best model through experimenting to extract features from the raw data. They claimed that trained CNNs successfully extracted features, and the results were statistically supported [

9].

Cinar & Yildirim compared the classification performances of 6 different CNN models: ResNet50, AlexNet, GoogleNet, DenseNet201, VGG19, Inceptionv3, SqueezeNet, and InceptionResNetV2. Test results are obtained, and original data is used to train the networks. After preprocessing the data using the same procedures, the pictures are then subjected to median and Gaussian filters. They reported that they had achieved a maximum rate accuracy of 96.6% using the GoogleNet model while identifying malaria data using Gaussian-filtered data [

10]. Dong et al. found that using transfer-based deep learning algorithms resulted in a success rate of over 95% in identifying malaria-infected cells [

11]. Yang et al. generated a data set of 1819 thick smear images from 150 individuals. A malaria detection investigation employing deep learning approaches achieved a maximum accuracy of 94.33% Yang et al. (2019).

Reddy et al. achieved 95.91% accuracy in detecting malaria using the ResNet50 architecture. They worked with a data set of 27558 images [

12]. In another study, researchers used AlexNet, Google Net, ResNet-50, MobileNet-v2, and VGG16 architectures. They claimed that the trained CNNs successfully extracted features. A maximum accuracy rate of 96.53% was obtained with the MobileNet-v2 model using the Adam optimizer [

13].

In this paper, source fusion of original and filtered data is proposed to improve the classification performance of the state-of-the-art Deep learning methods. Two approaches have been proposed, where in the first approach the original data is supported by the Gaussian and median filtered data. In this approach, the training and test data go through Gaussian and median filtering to generate three distinct data sets. The three data sets are combined in a single data set to be used in CNN-based deep learning architectures such as AlexNet, ResNet50, DenseNet201, VGG16, InceptionV3, SqueezeNet, InceptionResNetV2, and GoogleNet. The CNN architectures have been trained and tested with 80% and 20% of the data respectively. The results obtained via the first method indicate that performance is generally increased in most of the classifiers where the increase in AlexNet reaches 7% using accuracy. The second proposed approach involved using original, Gaussian, and median-filtered data sets separately. Each of the eight CNN architectures is trained by original and filtered data sets separately. Fusion of the original and filtered data (3 data sets) improves the performance of the respective CNN models. Finally, the decisions of each of the 8 CNN models are combined using sum-rule decision fusion. The overall performance reaches an outstanding classification performance of 100% in accuracy, specificity, and sensitivity metrics.

The paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 provides the related work,

Section 3 explains the data set utilized in this study,

Section 4 describes the method and the deep learning techniques,

Section 5 describes the research outcomes, and Section 6 ends with conclusion and suggestions for further research.

2. Dataset & Software

Two types of data classes are selected from the Kaggle dataset [

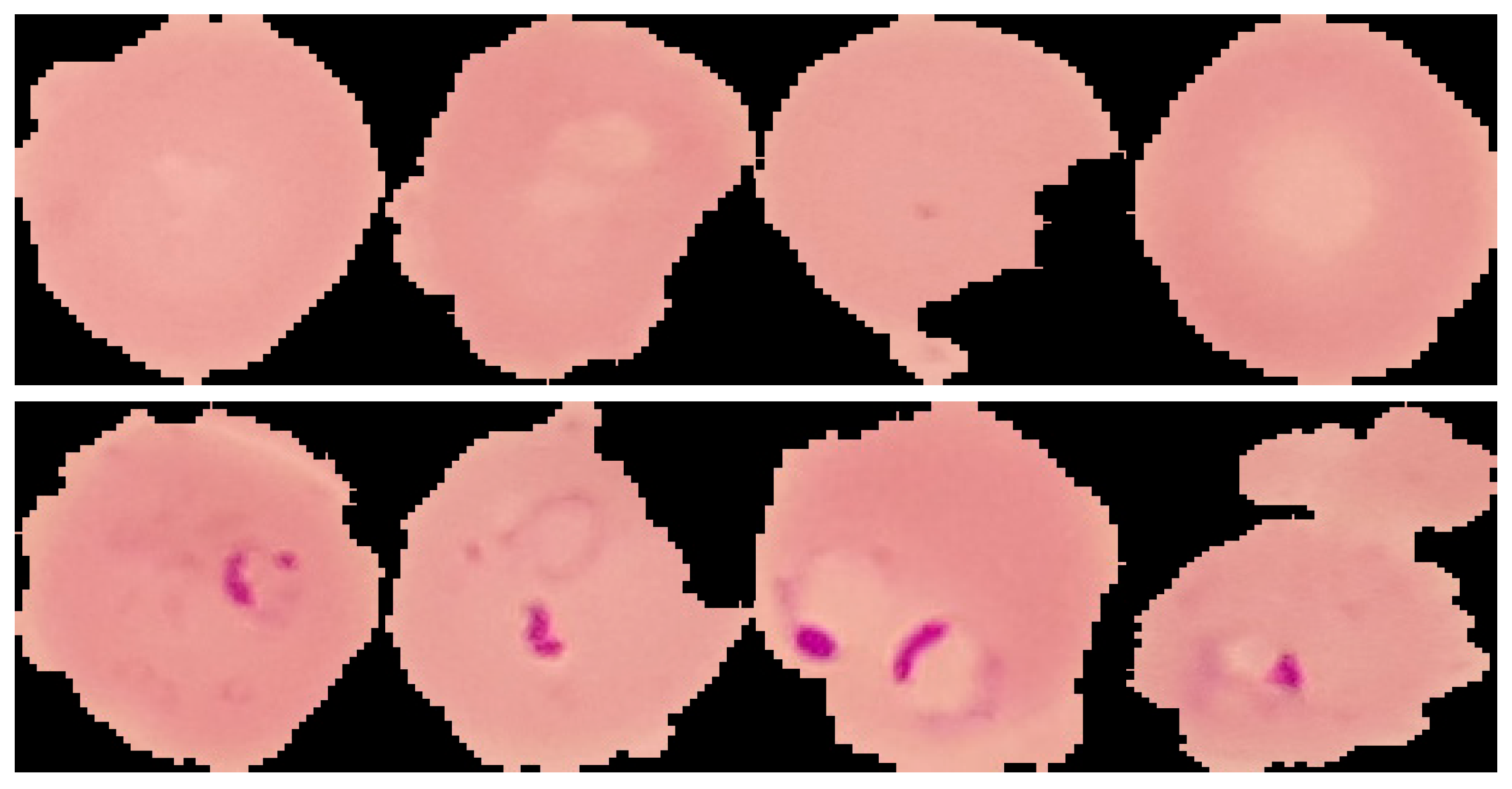

14]. The data of the first class is the healthy data, while the second is the parasitic data. These data consist of 3000 non-parasitic data and 3730 parasitic data. MATLAB R2021a environment used in our study. The data ratio has been distributed as 80% for training and 20% for testing, while 10% of the training is used as validation. The images are colored RGB with various sizes, thus they are resized to 224×224. The learning algorithm used is Adam optimizer, the learning rate is 0.0001, and the number of epochs is 5. Examples of uninfected/healthy (first row) and infected/parasitized (second row) images are shown in

Figure 1. The figure shows that finding parasitized cells can be challenging, even with a close-up view.

Performance metrics that include sensitivity, specificity, precision (positive predictive value), negative predictive value, and accuracy rates are used to evaluate the investigated and developed models. Their formulae are provided below. The confusion matrices are used to calculate these performance metrics. These confusion matrices contain information about the correctly identified positive samples (true positive—TP), the correctly identified negative samples (true negative—TN), the incorrectly classified negative samples (false positive—FP), and the incorrectly classified positive samples negative (false negative—FN). AP and AN represent all positive and all negative samples, respectively.

3. Proposed Fusion Techniques

Deep learning architectures have been effectively used in the processing of medical data in different modalities [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. Computers can process and learn from data with the help of deep learning. The primary feature that makes deep learning models above conventional neural networks is their multilayer structure. Deep learning has recently attracted the attention of researchers for several reasons, including the development of GPUs with faster processing speeds. The rise in interest toward deep learning also grew with the increase in the amount of collected data.

In this study, convolutional neural networks have been used as deep learning architecture. CNNs are one of the most effective deep learning networks for computer vision applications such as image classification. Network data is the main training source for CNN. The network goes through several layers to finish learning after receiving input images. These layers may be categorized as convolution, fully connected, pooling, dropout, normalization, and SoftMax layers [

20].

In this study, 8 different architectures of pre-trained models will be studied and investigated, namely, AlexNet [

21], GoogleNet [

22], DenseNet201 [

23], ResNet50 [

24], Inceptionv3 [

25], VGG16 [

26], InceptionResNet [

27], and SqueezeNet [

28]. The Gaussian and median filtering techniques are used to augment the data set to boost the performance. The study proposes 3 data fusion methods: Source fusion, sum-rule decision fusion for each pre-trained model and sum-rule decision fusion for all eight models.

3.1. Source Fusion

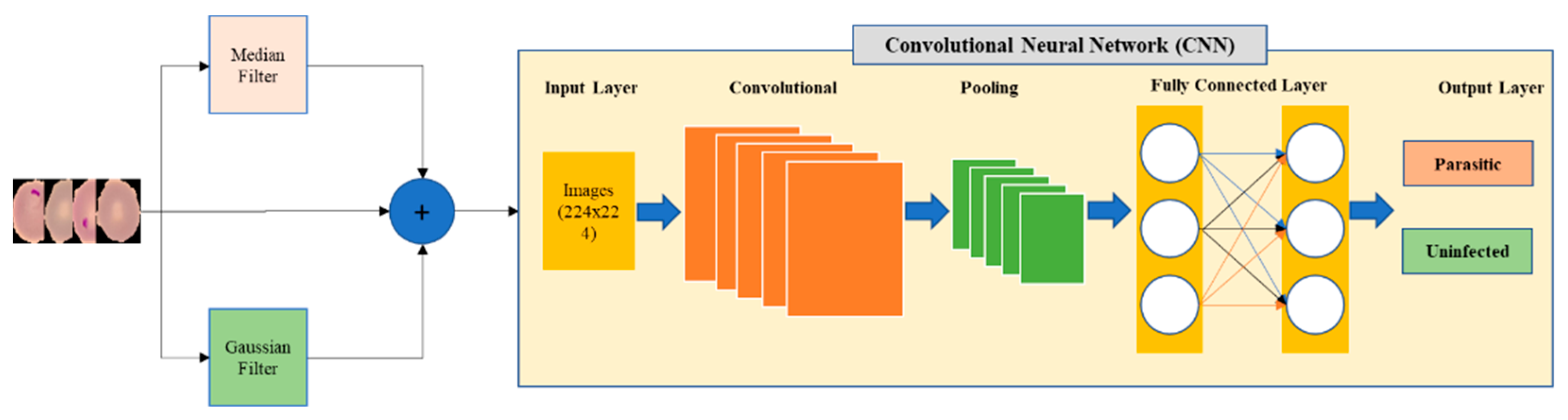

In this method, the original and the filtered data are combined to form one dataset that contains a total of 20190 images. Two types of filters, Gaussian and median filters, are used for generation of the filtered data. The overall samples containing the original and the filtered data are classified by 8 different pre-trained models. Each CNN model consists of layers including input layer, convolutional layers, pooling layers, fully connected layers, and output layer. The structure of the proposed model is illustrated in

Figure 2.

3.2. Sum-Rule Based Decision Fusion

3.2.1. Decision Fusion for Each Pre-Trained Model

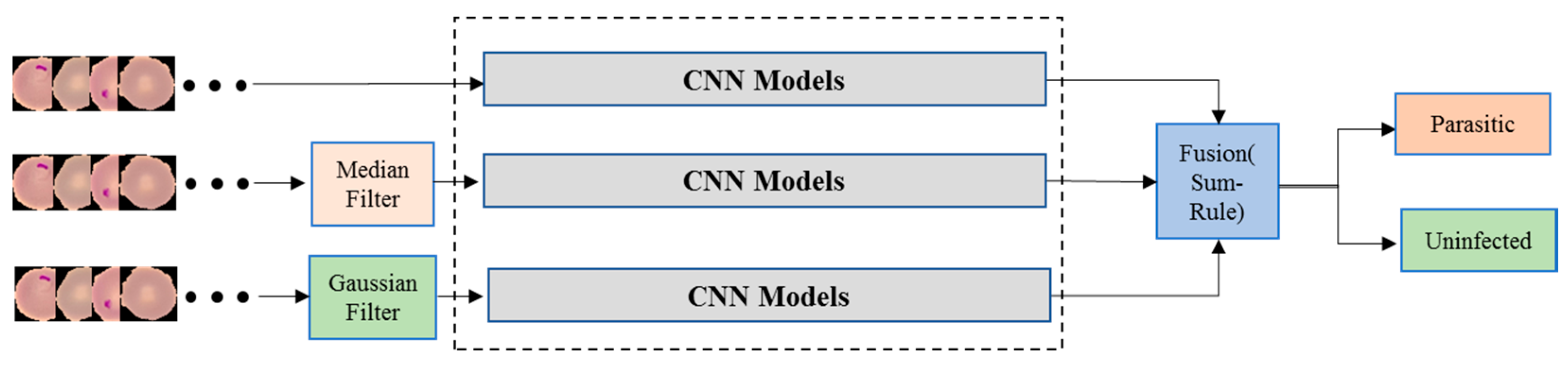

This method utilizes the sum-rule decision fusion by employing it among the original, the Gaussian and the median filtered modalities using each CNN Model. The classification probabilities of each model are fused to generate the decision of the respective CNN model. In this way, 8 distinct classifiers have been formed with dedicated classification performances.

Figure 3 illustrates the proposed sum-rule decision fusion method for each CNN model.

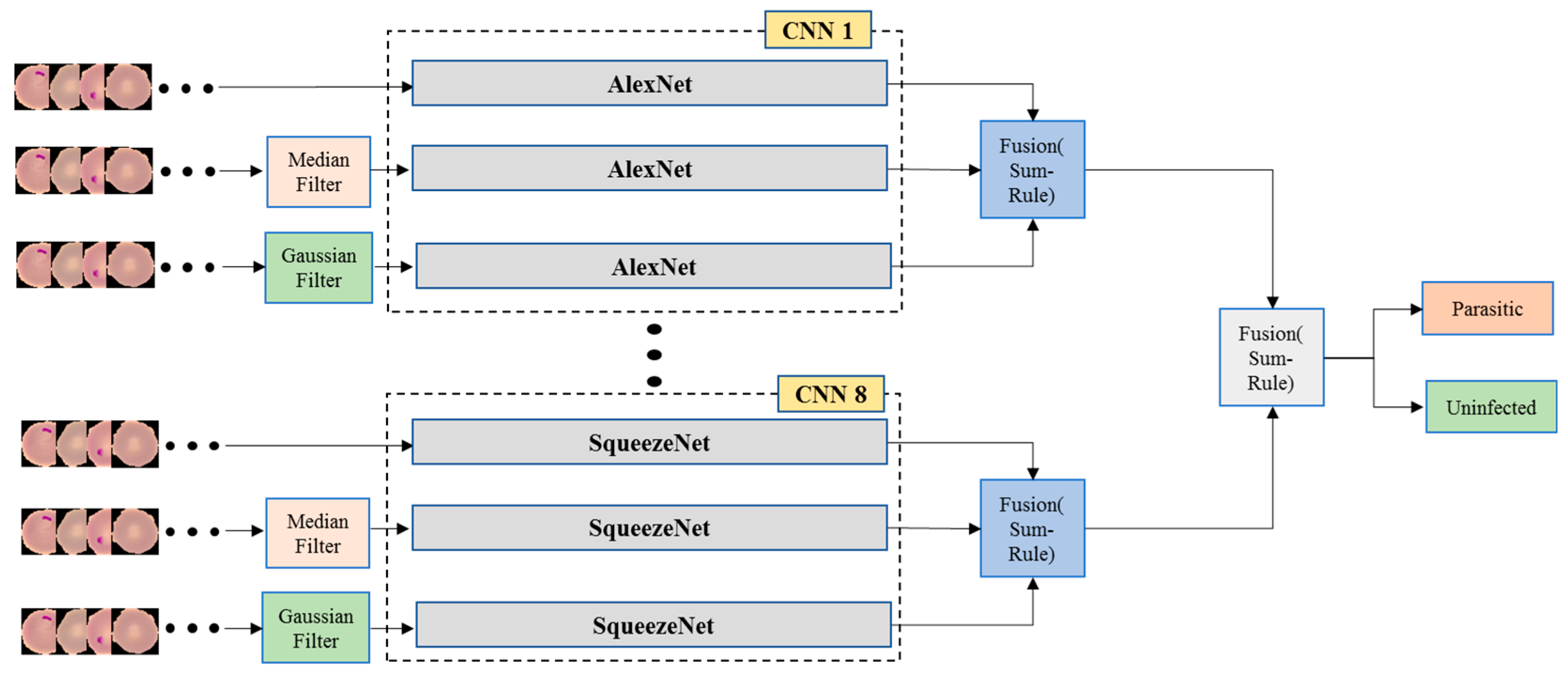

3.2.2. Decision Fusion Among All 8 Pre-Trained Models

Having 8 distinct classifiers using 8 different pre-trained CNN Models, we propose to employ another level of decision fusion where the probabilities generated by the 8 distinct classifiers are fused once more using sum-rule to generate the overall classification performance. The details of the developed framework are illustrated in

Figure 4.

4. Results and Discussions

In this section extensive experiments are conducted on the dataset to evaluate the performance of the proposed 3 methods. The original data obtained from Kaggle had 6730 samples/images. After reshaping the images to 224×224 size and applying the Gaussian and the median filters the dataset increased to a total of 20190 samples/images. In the first method, the original data along with the filtered data are combined to obtain a single data set. This data set is used by 8 distinct classifiers with different pre-trained convolutional neural network (CNN) architectures. The median and Gaussian filters are adopted which can provide two distinct ways of filtering and complementing the original data set. Gaussian filter involves a linear process with a weighted average of nearby pixels to determine the filter response [

29]. The median filter’s objective is to soften and reduce the sharp tone shifts such as impulses in the image [

30].

Figure 2 illustrates the processing blocks of the proposed source fusion method which combines original and filtered data. The original and filtered images are individually processed with AlexNet, DenseNet201, ResNet50, VGG16, InceptionV3, GoogleNet, InceptionResNetv2, and SqueezeNet. The images are then classified as healthy/uninfected or infected/parasitized. Classification performance by means of accuracy and other metrics are provided in

Table 1 and

Table 2, respectively.

The performances of the proposed source fusion method compared with original data are given in

Table 1. The results show that performance is generally increased after applying source fusion methodology. The highest performance increase was in AlexNet with a notable improvement of 7.2%. While marginal decrease was encountered in DenseNet201and InceptionResNetV2 (0.5% and 0.6%, respectively), the rest of the methods showed credible performance increase.

Table 2 compares the performances of the 8 CNN models by the performance metrics listed in

section 2 namely, sensitivity, PPV, NPV, and specificity. VGG16 stands out with the highest values in sensitivity, PPV and specificity. InceptionV3 also performs well, with high sensitivity and NPV, although its specificity and PPV are slightly lower. GoogleNet shows strong results with Sensitivity and PPV while AlexNet has solid performance across all metrics, especially sensitivity and NPV.

The second proposed method is the sum-rule decision fusion where each CNN model is employed in 3 different classification channels using original, median filtered, and Gaussian filtered data respectively.

Figure 3 illustrates the proposed sum-rule decision fusion method for each CNN model. Classification performance by means of accuracy and other metrics of the sum-rule decision fusion are provided in

Table 3 and

Table 4 respectively.

The performance of the proposed sum-rule decision fusion method (method 2) compared with original data, median filtered, and Gaussian filtered for each model are represented in

Table 3. The results show that performance is mostly increased after applying the proposed sum-rule decision fusion method for each CNN model. The highest performance was recorded by AlexNet with a notable improvement of 8.8% compared to the original data channel. GoogleNet achieves the highest accuracy performance (99.9%), while SqueezeNet reveals the lowest performance (97.4%).

Table 4 compares the performance of the sum-rule decision fusion of the 8 different pre-trained CNN models.

The results provided in

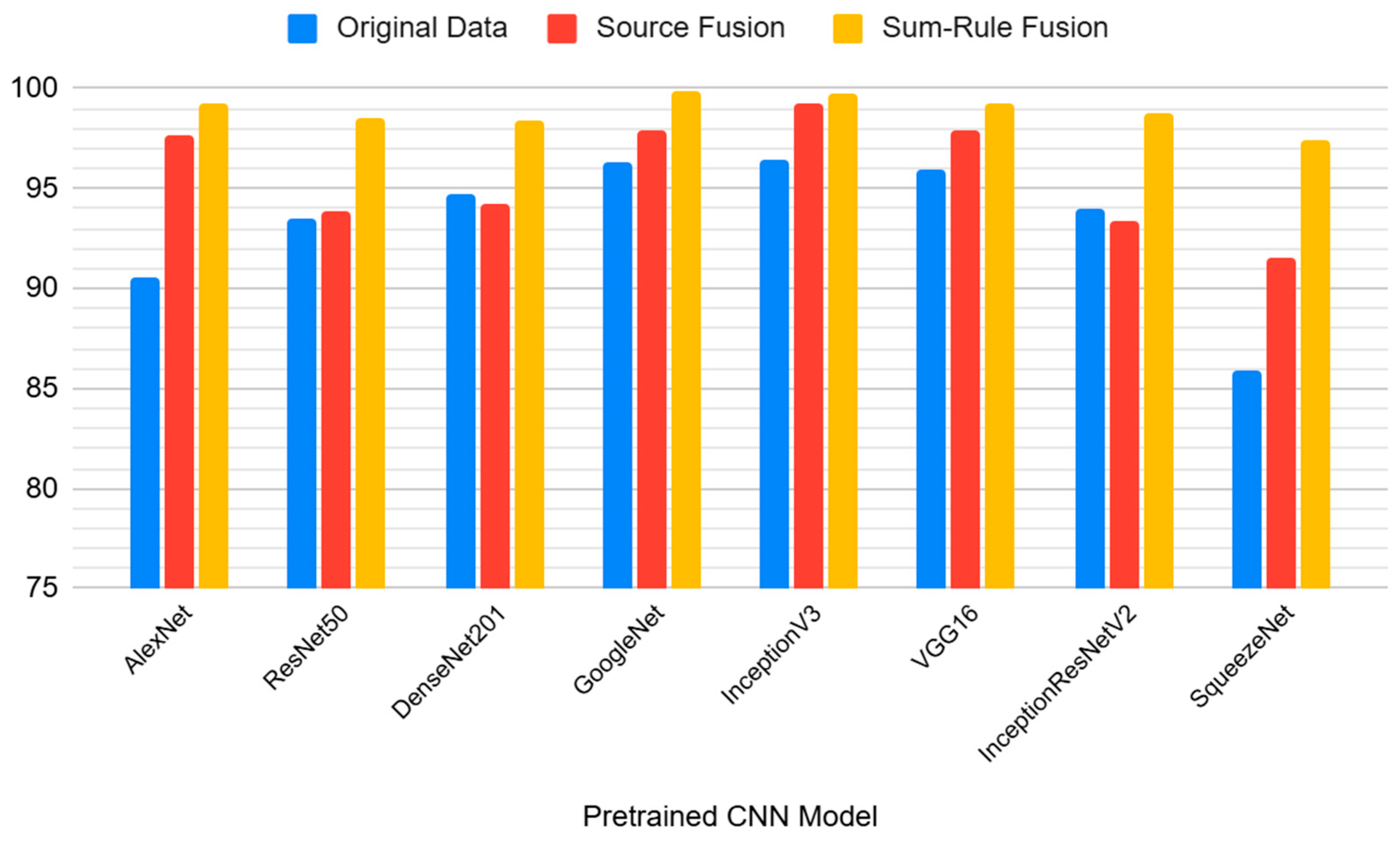

Figure 5 compare the performance of 8 CNN models using the three different data processing techniques: original data, source fusion, and sum-rule fusion. The highest performance on the original dataset without any fusion is achieved by InceptionV3 (96.4%), followed closely by GoogleNet (96.3%). With Source Fusion of the original data and Gaussian and median filtered data, InceptionV3 improves notably, reaching 99.2%, reflecting a strong increase from the original accuracy (96.4%). GoogleNet stands out here with the highest performance of 99.9% using sum-rule fusion, representing a major improvement from the original data and source fusion results. The sum-rule fusion method consistently yields higher accuracy compared to the original data and source fusion approaches across almost all models.

In the third method, we combined the sum-rule decisions generated from each of the 8 pre-trained CNN models to provide a higher level of decision fusion by using a second sum-rule to obtain the overall decision fusion.

Figure 4 displays the overall sum-rule decision fusion for all 8 pre-trained CNN models.

Table 5 shows the performances of the proposed three fusion methods compared to other methods in the literature for binary classification of malaria as parasitic or uninfected using different deep learning techniques or models. The highest accuracy performance was in the study of Pan et al. [

8], in which they achieved an accuracy of 99 % using LeNet-5 architecture with a small dataset (800 images). In this study, InceptionV3 architecture gave an accuracy of 99.2% when the source fusion approach (method 1) was applied. Furthermore, the sum-rule decision fusion method of 3 channels achieved an accuracy of 99.9% using GoogleNet (method 2). Finally, the sum-rule decision fusion method among all 8 pre-trained CNN models (method 3) outperformed all other models by achieving an accuracy of 100%.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, malaria images were binary classified using different pre-trained CNN architectures with and without data fusion at source and decision levels. Three different fusion methods of the original and filtered data to improve the classification performance. The first method combines the original data with Gaussian and median-filtered data at the source level before feeding the fused data into one of the pre-trained CNN architectures. The second method utilizes original, Gaussian-filtered filtered, and median-filtered data to go through separate CNN architectures where the resulting class probabilities are fused at the decision level using the sum-rule. Finally, the third method proposed using the resulting class probabilities generated from method 2 for each of the 8 pre-trained CNN models to go through a second sum-rule fusion stage before making the final decision. In method 1 accuracy reaches 99.2% using the InceptionV3 model. An accuracy value of 99.9% was obtained in the second method by the GoogleNet model. Finally, the third method generated the highest possible accuracy 100%. These results become more meaningful when compared with the CNN-based classification of the original data without any fusion approaches which only generates accuracy between 85.9% (SqueezeNet) and 96.4% (InceptionV3).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A. and H.D.; Methodology, M.A. and H.D.; Software, M.A. and H.D.; Validation, M.A., H.D. and A.E.; Formal analysis, M.A., H.D. and A.E.; Investigation, M.A., H.D. and A.E.; Resources, H.D. and A.E.; Data curation, M.A.; Writing—original draft preparation, M.A., H.D.; Writing—review and editing, M.A., H.D. and A.E.; Visualization, M.A., and A.E.; Supervision, H.D. and A.E.; Project administration, H.D. and A.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. World Malaria Report 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/global-malaria-programme/reports/world-malaria-report-2023 (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Sivaramakrishnan R, Antani S, Jaeger S (2017) Visualizing deep learning activations for improved malaria cell classification. Medical informatics and healthcare pp 40–47.

- Wongsrichanalai C, Barcus MJ, Muth S, et al (2007) Defining and Defeating the Intolerable Burden of Malaria III: Progress and Perspectives: Supplement to American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 77(6).

- Schochetman G, Ou CY, Jones WK (1988) Polymerase Chain Reaction. The Journal of Infectious Diseases, 158, 1154-1157. [CrossRef]

- Azikiwe CC, Ifezulike CC, Siminialayi IM, et al (2012) A comparative laboratory diagnosis of malaria: microscopy versus rapid diagnostic test kits. Asian Pacific journal of tropical biomedicine 2(4):307–310. [CrossRef]

- Shen H, Pan WD, Dong Y, et al (2016) Lossless compression of curated erythrocyte images using deep autoencoders for malaria infection diagnosis. Picture coding symposium (PCS) pp 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Vijayalakshmi, A.; Rajesh Kanna, B. (2020) Deep learning approach to detect malaria from microscopic images. Multimedia. Tools & Applications. 2020, 79, 15297–15317. [CrossRef]

- Pan WD, Dong Y, Wu D (2018) ‘Classification of Malaria-Infected Cells Using Deep Convolutional Neural Networks’, Machine Learning - Advanced Techniques and Emerging Applications. InTech, Sep. 19, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Rajaraman S, Antani SK, Poostchi M, et al (2018) Pre-trained convolutional neural networks as feature extractors toward improved malaria parasite detection in thin blood smear images. PeerJ 6:4568–4568.

- Çinar, A., Yildirim, M. (2020). Classification of malaria cell images with deep learning architectures. Ingénierie des Systèmes d’Information, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 35-39. [CrossRef]

- Dong Y, Jiang Z, Shen H, et al (2017) Evaluations of deep convolutional neural networks for automatic identification of malaria infected cells. 2017 IEEE EMBS international conference on biomedical & health informatics (BHI) pp 101–104. [CrossRef]

- Reddy ASB, Juliet DS (2019) Transfer learning with ResNet-50 for malaria cell- image classification. 2019 International Conference on Communication and Signal Processing (ICCSP) pp 945–0949.

- Soylu E (2022) A Deep Transfer Learning-Based Comparative Study for Detection of Malaria Disease. Sakarya University Journal of Computer and Information Sciences 5(3):427–447. [CrossRef]

- Goldbloom A, Hamner B, Moser J, et al. Kaggle: your machine learning and data science community 2010. Accessed 4 October 2024.

- Mao H, Han S, Pool J, et al (2017) Exploring the Regularity of Sparse Structure in Convolutional Neural Networks, Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops, 2017, pp. 13-20. [CrossRef]

- Eleyan, A.; Alboghbaish, E. Electrocardiogram signals classification using deep-learning-based incorporated convolutional neural network and long short-term memory framework. Computers 2024, 13, 55. [CrossRef]

- Manalı, D.; Demirel, H.; Eleyan, A. Deep Learning Based Breast Cancer Detection Using Decision Fusion. Computers 2024, 13, 294. [CrossRef]

- Bayram, F.; Eleyan, A. (2022) COVID-19 detection on chest radiographs using feature fusion based deep learning. Signal Image Video Process. 2022, 16, 1455–1462. [CrossRef]

- Eleyan, A.; Bayram, F.; Eleyan, G. (2024) Spectrogram-Based Arrhythmia Classification Using Three-Channel Deep Learning Model with Feature Fusion. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9936. [CrossRef]

- Simon M, Rodner E, Denzler J (2016), ImageNet pre-trained models with batch normalization, arXiv: 1612.01452. [CrossRef]

- Krizhevsky A, Sutskever I, Hinton GE (2017) ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Communications of the ACM 60(6):84–90. [CrossRef]

- Szegedy C, Liu W, Jia Y, et al (2015) Going deeper with convolutions. Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition pp 1–9.

- Haupt, J., Kahl, S., Kowerko, D., & Eibl, M. (2018). Large-Scale Plant Classification using Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. CLEF (Working Notes), 3.

- He K, Zhang X, Ren S, et al (2016) Deep residual learning for image recognition. Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition pp 770–778.

- Lin C, Li L, Luo W, et al (2019) Transfer learning-based traffic sign recognition using inception-v3 model. Periodica Polytechnica Transportation Engineering 47(3):242– 250. [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Fernandez F, Hernandez-Diaz K, Rubio JMB, et al (2023) Squeezerfacenet: Reducing a small face recognition CNN even more via filter pruning. In: International Workshop on Artificial Intelligence and Pattern Recognition. Springer Nature Switzerland, pp 349–361. [CrossRef]

- Kumar PMV, Venaik A, Shanmugaraja P, et al (2023) Design of inception ResNet V2 for detecting malarial infection using the cell image captured from microscopic slide. The Imaging Science Journal pp 1–12.

- Yang L, Xu S, Yu XY, et al (2023) A new model based on improved VGG16 for corn weed identification. Frontiers in Plant Science 14. [CrossRef]

- Kwon Y, Kim KI, Tompkin J, et al (2015) Efficient Learning of Image Super-Resolution and Compression Artifact Removal with Semi-Local Gaussian Processes, IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, vol. 37, no. 9, pp. 1792-1805, 1 Sept. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Fan W, Wang K, Cayre F, et al (2015) Median filtered image quality enhancement and anti-forensics via variational deconvolution. IEEE transactions on information forensics and security 10(5):1076–1091. [CrossRef]

- Yang F, Poostchi M, Yu H, et al (2019) Deep learning for smartphone-based malaria parasite detection in thick blood smears. IEEE journal of biomedical and health informatics 24(5):1427–1438. [CrossRef]

- Boit, S.; Patil, R. An Efficient Deep Learning Approach for Malaria Parasite Detection in Microscopic Images. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 2738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibin, D.; Nair, M.S.; Punitha, P. Malaria Parasite Detection from Peripheral Blood Smear Images Using Deep Belief Networks. IEEE Access 2017, 5, 9099–9108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemachran, K.; Nithya, V.; Mahesh, A. Identification of Malaria Parasite Using MobileNetV2 and Deep Learning Techniques. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Technol. 2020, 29, 13077–13086. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).