Submitted:

04 January 2025

Posted:

08 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. MARMA()-GARCH() Processes

2.1.1. Causal and Invertible Representation

2.1.2. Spectral Representations

2.2. Parameter Estimation and Identification

2.2.1. Estimation and Identification of the MARMA() Process

2.2.2. Spectral Identification Function

2.2.3. Portmanteau-Type i.i.d. Test

2.2.4. Whittle Estimation for the GARCH()

2.2.5. Maximum Likelihood Estimation for the GARCH()

2.3. Detrending Method

2.3.1. Cubic Splines

Fourier Detrending

3. Results

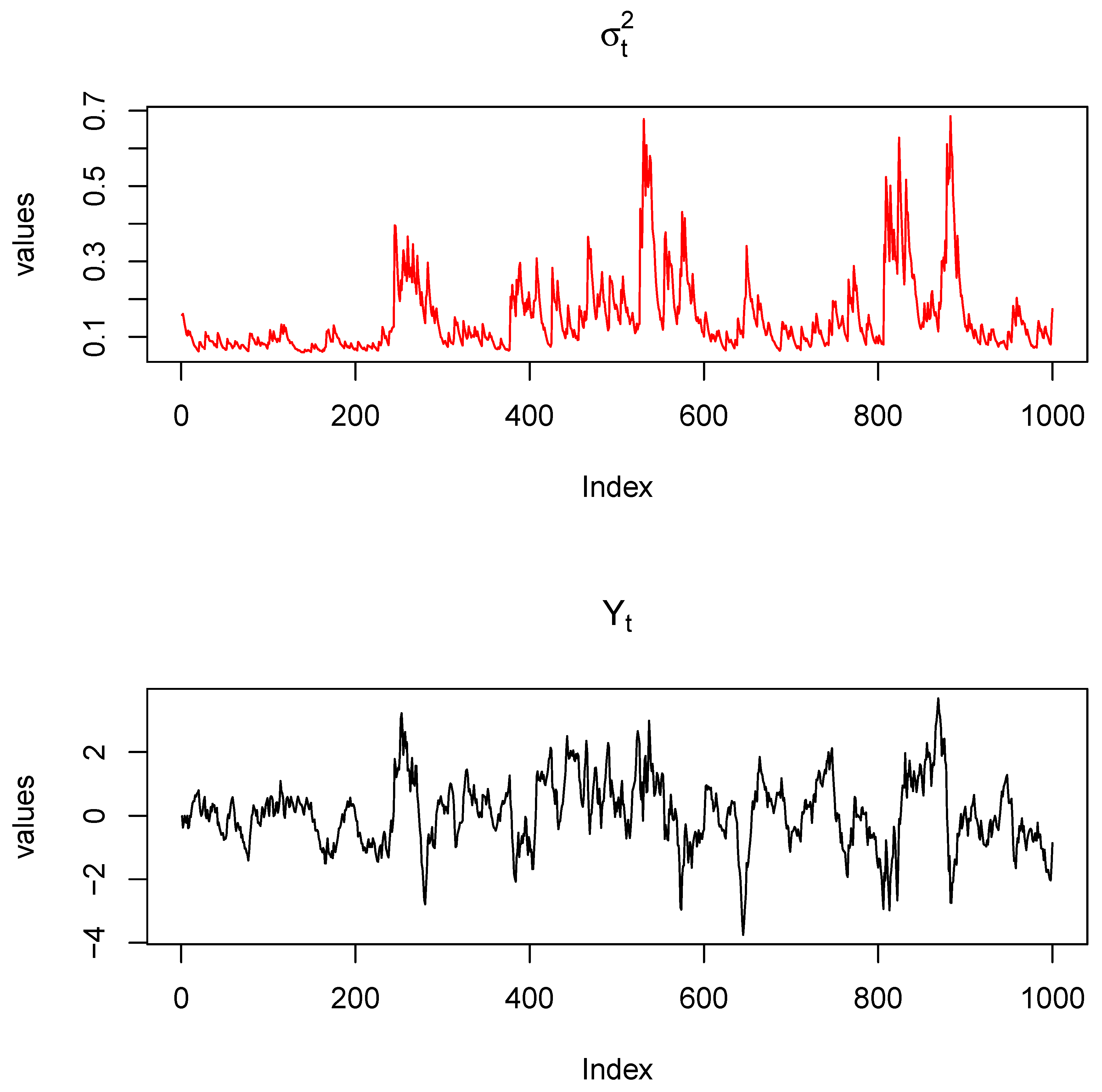

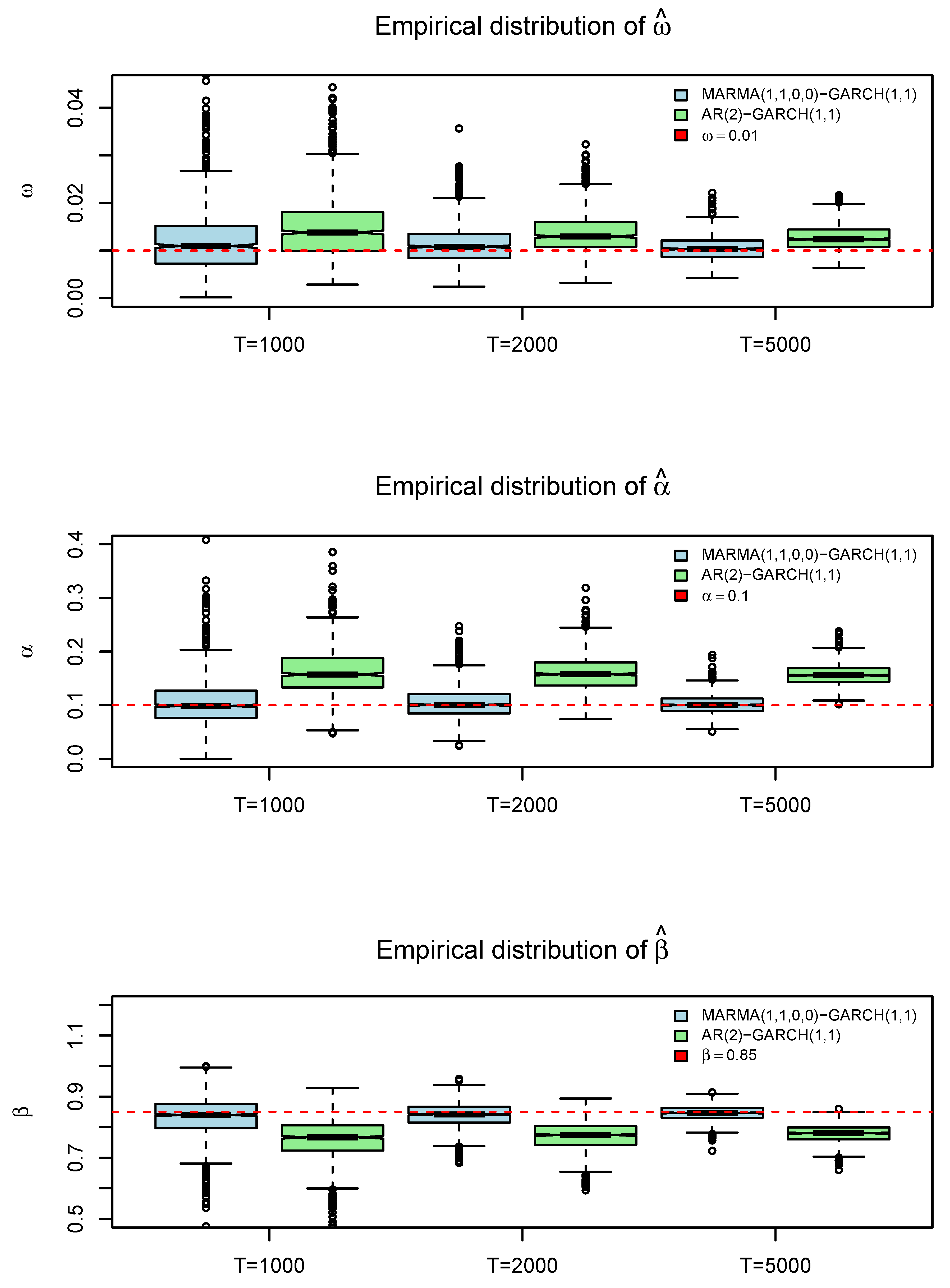

3.1. Simulation Study

- Generate an error sequence: Simulate T realizations of an i.i.d. random error sequence: , where . Here, is a chosen distribution function with parameters . We ensure has zero mean and unit variance.

-

Generate the conditional variance:

- (a)

- Initialize and compute .

- (b)

- Determine for .

- Compute the discrete Fourier transform (DFT): Perform the DFT of : .

- Select MARMA parameters: Choose parameters and orders for the MARMA() process and define the transfer function:

- Compute DFT of :.

- Recover : Obtain as the real part of the inverse Fourier transform of :

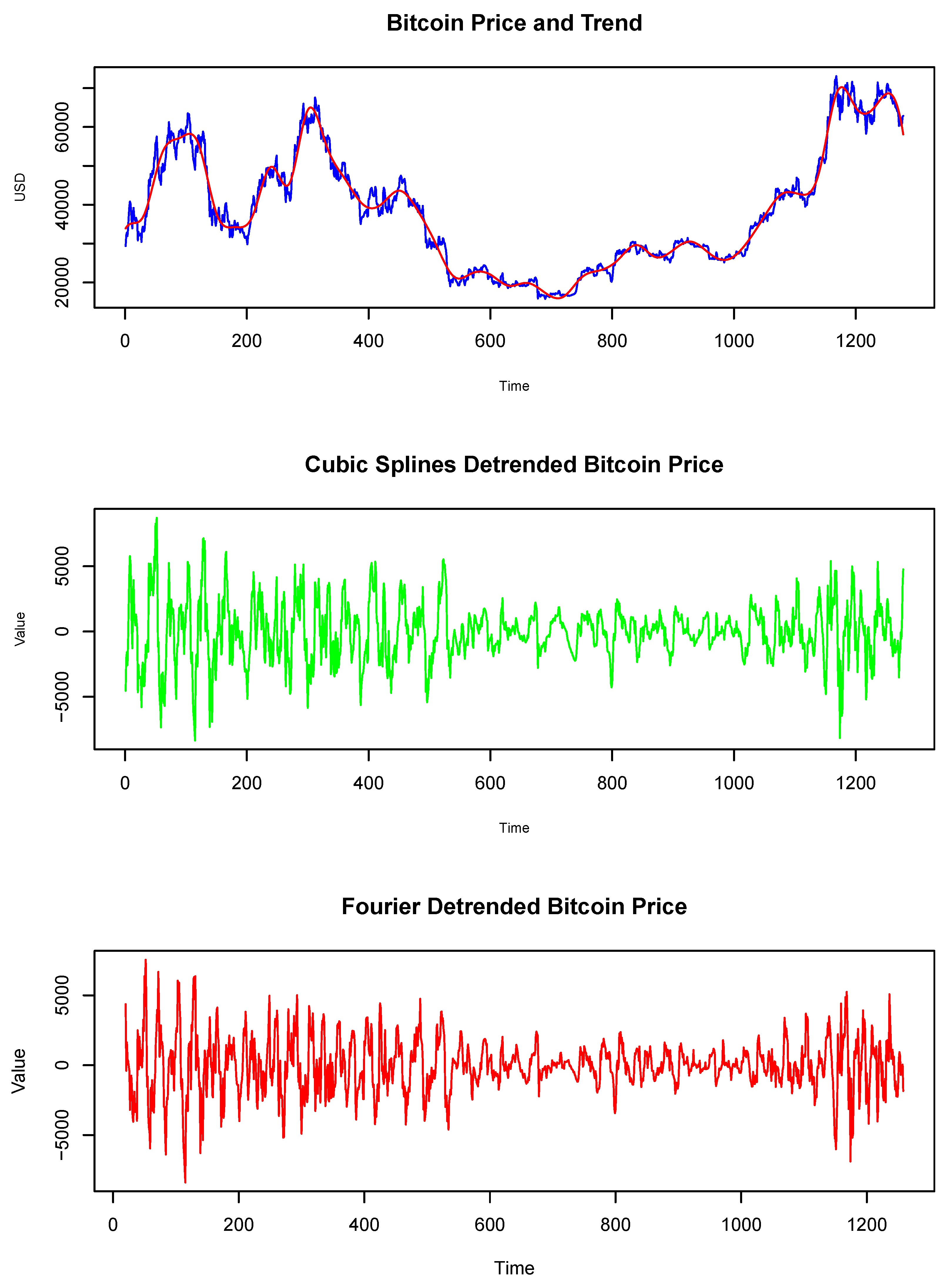

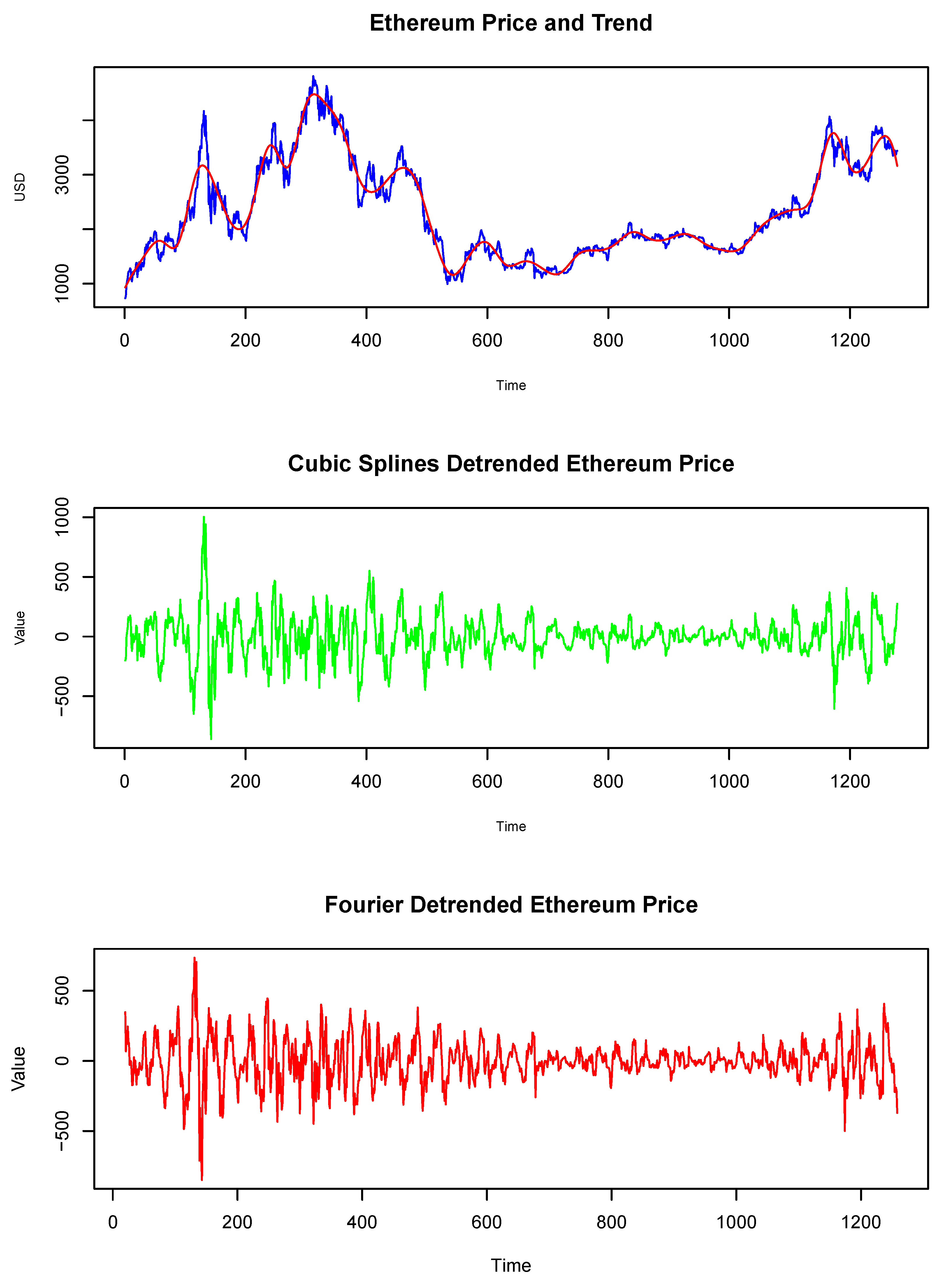

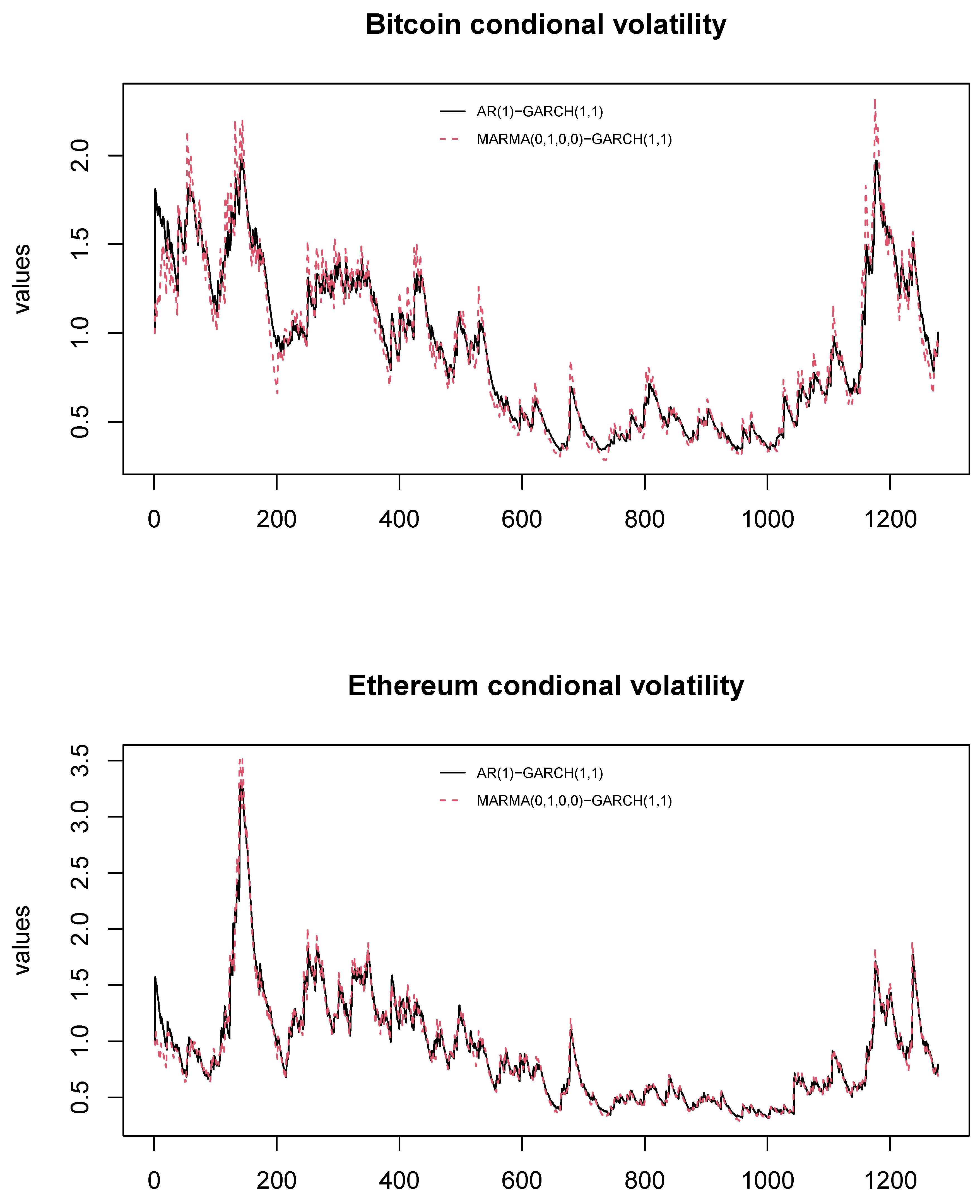

3.2. Empirical Applications in Cryptocurrencies

4. Discussion and Conclusions

| 1 | |

| 2 | We can also call this representation pseudo causal and invertible. |

| 3 | There is another difference with their approach as they consider such a test in the autoregressive representation that allows roots inside and outside the unit circle in the tradition of the GCov estimator. |

References

- Aguirre, A. and Lobato, I. N. (2024). Evidence of non-fundamentalness in oecd capital stocks. Empirical Economics, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Ardia, D. , Bluteau, K., and Rüede, M. (2019). Regime changes in bitcoin garch volatility dynamics. Finance Research Letters, 29, 266–271. [CrossRef]

- Baur, D. G. , Hong, K., and Lee, A. D. (2018). Bitcoin as a hedge or safe haven: Evidence from stock, bond and gold markets. Finance Research Letters, 20, 192–198. [CrossRef]

- Bazán-Palomino, W. (2022). Interdependence, contagion and speculative bubbles in cryptocurrency markets. Finance Research Letters, 49, 3132. [CrossRef]

- Blasques, F. , Koopman, S. J., and Mingoli, G. (2023). Observation-driven filters for time-series with stochastic trends and mixed causal non-causal dynamics. Technical report, Tinbergen Institute Discussion Paper.

- Blasques, F. , Koopman, S. J., Mingoli, G., and Telg, S. (2024). A novel test for the presence of local explosive dynamics. Technical report, Tinbergen Institute Discussion Paper.

- Bloomfield, P. (2004). Fourier analysis of time series: an introduction, John Wiley & Sons.

- Bollerslev, T. (1986). Generalized autoregressive conditional heteroskedasticity. Journal of econometrics, 31(3), 307–327. [CrossRef]

- Bouoiyour, J. and Selmi, R. (2015). What does bitcoin look like?

- Bouoiyour, J. and Selmi, R. (2016). Bitcoin price: Is it really that new round of volatility can be on way? MPRA Paper No. 65586.

- Bouri, E. , Azzi, G., and Dyhrberg, A. H. (2017). On the return-volatility relationship in the bitcoin market around the price crash of 2013. Economics, 61, 45–51. [CrossRef]

- Breidt, F. J. , Davis, R. A., and Trindade, A. A. (2001). Least absolute deviation estimation for all-pass time series models. The Annals of Statistics, 29(4), 919–946. [CrossRef]

- Brillinger, D. R. (2001). Time series: data analysis and theory, SIAM.

- Brockwell, P. J. and Davis, R. A. (1991). Time series: theory and methods, Springer science & business media.

- Cheah, E.-T. and Fry, J. (2015). Speculative bubbles in bitcoin markets? an empirical investigation into the fundamental value of bitcoin. Economics Letters, 130, 32–36. [CrossRef]

- Cont, R. (2001). Empirical properties of asset returns: stylized facts and statistical issues. Quantitative finance, 1, 223. [CrossRef]

- Corbet, S. , Meegan, A., Larkin, C., Lucey, B., and Yarovaya, L. (2017). Exploring the dynamic relationships between cryptocurrencies and other financial assets. Economics Letters, 165, 28–34. [CrossRef]

- Cubadda, G. , Hecq, A., and Telg, S. (2019). Detecting co-movements in non-causal time series. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 81, 697–715. [CrossRef]

- Dalla, V. , Giraitis, L., and Phillips, P. C. (2020). Robust tests for white noise and cross-correlation. Econometric Theory, 1–29. [CrossRef]

- De Boor, C. and De Boor, C. (1978). A practical guide to splines, volume 27; springer: New York.

- Dyhrberg, A. H. (2016). Bitcoin, gold and the dollar–a garch volatility analysis. Finance Research Letters, 16, 85–92. [CrossRef]

- Engle, R. F. (1982). Autoregressive conditional heteroscedasticity with estimates of the variance of united kingdom inflation. Econometrica: Journal of the econometric society, 987. [CrossRef]

- Eubank, R. L. (1999). Nonparametric regression and spline smoothing, CRC press.

- Francq, C. and Zakoian, J.-M. (2019). GARCH models: structure, statistical inference and financial applications, John Wiley & Sons.

- Fries, S. and Zakoïan, J.-M. (2019). Mixed causal-noncausal ar processes and the modelling of explosive bubbles. Econometric Theory, 35, 1234–1270. [CrossRef]

- Giancaterini, F. and Hecq, A. (2022). Inference in mixed causal and noncausal models with generalized student’s t-distributions. Econometrics and Statistics. [CrossRef]

- Giraitis, L. , Robinson, P. M., and Surgailis, D. (2000). A model for long memory conditional heteroscedasticity. Annals of Applied Probability, 1002–1024.

- Glaser, F. , Haferkorn, M., Weber, M. C., and Siering, M. (2014). Bitcoin-asset or currency? revealing users’ hidden intentions. ECIS.

- Gouriéroux, C. and Zakoïan, J.-M. (2017). Local explosion modelling by non-causal process. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Statistical Methodology), 79, 737–756. [CrossRef]

- Green, P. J. and Silverman, B. W. (1993). Nonparametric regression and generalized linear models: a roughness penalty approach, Crc Press.

- Gronwald, M. (2014). The economics of bitcoins–market characteristics and price jumps. CESifo Working Paper Series No. 5121.

- Hafner, C. M. (2018). Hedging properties of bitcoin: A garch-extended analysis. Finance Research Letters, 30, 151–155.

- Hall, M. K. and Jasiak, J. (2024). Modelling common bubbles in cryptocurrency prices. Economic Modelling, 106782. [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, J. D. (2018). Why you should never use the hodrick-prescott filter. Review of Economics and Statistics, 100, 831–843. [CrossRef]

- Hannan, E. J. (1973). The asymptotic theory of linear time-series models. Journal of Applied Probability, 10, 130–145. [CrossRef]

- Hastie, T. , Tibshirani, R., Friedman, J. H., and Friedman, J. H. (2009). The elements of statistical learning: data mining, inference, and prediction, Springer; volume 2.

- Hecq, A. , Telg, S., and Lieb, L. (2017). Do seasonal adjustments induce noncausal dynamics in inflation rates? Econometrics, 5, 48. [CrossRef]

- Hecq, A. and Velasquez-Gaviria, D. (2022). Spectral estimation for mixed causal-noncausal autoregressive models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2211.13830, arXiv:2211.13830.

- Hecq, A. and Velasquez-Gaviria, D. (2024). Non-causal and non-invertible arma models: Identification, estimation and application in equity portfolios. Journal of Time Series Analysis. [CrossRef]

- Hecq, A. and Voisin, E. (2023). Predicting bubble bursts in oil prices during the covid-19 pandemic with mixed causal-noncausal models. in Advances in Econometrics in honor of Joon Y. Park.

- Hencic, A. and Gouriéroux, C. (2015). Noncausal autoregressive model in application to bitcoin/usd exchange rates. In Econometrics of risk, pages 17–40. Springer. [CrossRef]

- Jasiak, J. and Neyazi, A. M. (2023). Gcov-based portmanteau test. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.05373, arXiv:2312.05373.

- Katsiampa, P. (2017). Volatility estimation for bitcoin: A comparison of garch models. Economics Letters, 158, 3–6. [CrossRef]

- Lanne, M. and Saikkonen, P. (2011). Noncausal autoregressions for economic time series. Journal of Time Series Econometrics, 3. [CrossRef]

- Lobato, I. N. and Velasco, C. (2022). Single step estimation of arma roots for nonfundamental nonstationary fractional models. The Econometrics Journal, 25, 455–476. [CrossRef]

- Lof, M. and Nyberg, H. (2017). Noncausality and the commodity currency hypothesis. Energy Economics, 65, 424–433. [CrossRef]

- Meitz, M. and Saikkonen, P. (2013). Maximum likelihood estimation of a noninvertible arma model with autoregressive conditional heteroskedasticity. Journal of Multivariate Analysis, 114, 227–255. [CrossRef]

- Mikosch, T. and Straumann, D. (2002). Whittle estimation in a heavy-tailed garch (1, 1) model. Stochastic processes and their applications, 100, 187–222. [CrossRef]

- Robinson, P. M. (1995). Log-periodogram regression of time series with long range dependence. The annals of Statistics, 1048–1072.

- Velasco, C. and Lobato, I. N. (2018). Frequency domain minimum distance inference for possibly noninvertible and noncausal arma models. The Annals of Statistics, 46, 555–579.

- Xia, Y. , Sang, C., He, L., and Wang, Z. (2023). The role of uncertainty index in forecasting volatility of bitcoin: fresh evidence from garch-midas approach. Finance Research Letters, 52, 103391. [CrossRef]

| Bias | RMSE | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whittle Estimation | Maximum Likelihood | Whittle Estimation | Maximum Likelihood | |||||||||

| T | ||||||||||||

| Distribution: Exp(1) | ||||||||||||

| 1000 | 0.089 | -0.030 | -0.030 | 0.020 | 0.006 | -0.020 | 0.288 | 0.073 | 0.182 | 0.067 | 0.063 | 0.081 |

| 2000 | 0.076 | -0.028 | -0.016 | 0.010 | 0.006 | -0.011 | 0.163 | 0.049 | 0.100 | 0.030 | 0.028 | 0.035 |

| 5000 | 0.073 | -0.024 | -0.016 | 0.002 | 0.000 | -0.002 | 0.115 | 0.032 | 0.075 | 0.010 | 0.011 | 0.013 |

| Distribution: Student’s t (8) | ||||||||||||

| 1000 | 0.055 | -0.018 | -0.015 | 0.014 | -0.001 | -0.009 | 0.136 | 0.039 | 0.092 | 0.034 | 0.026 | 0.036 |

| 2000 | 0.043 | -0.011 | -0.013 | 0.007 | 0.001 | -0.005 | 0.064 | 0.030 | 0.050 | 0.015 | 0.012 | 0.015 |

| 5000 | 0.039 | -0.008 | -0.012 | 0.001 | -0.001 | 0.000 | 0.042 | 0.016 | 0.031 | 0.006 | 0.005 | 0.006 |

| Distribution: Student’s t (4.5) | ||||||||||||

| 1000 | 0.103 | -0.023 | -0.039 | 0.020 | 0.003 | -0.017 | 0.248 | 0.054 | 0.152 | 0.046 | 0.039 | 0.051 |

| 2000 | 0.079 | -0.024 | -0.020 | 0.012 | 0.004 | -0.012 | 0.120 | 0.033 | 0.072 | 0.022 | 0.022 | 0.026 |

| 5000 | 0.054 | -0.024 | -0.008 | 0.003 | 0.000 | -0.003 | 0.063 | 0.019 | 0.045 | 0.007 | 0.008 | 0.009 |

| Distribution: skew-t(4.5,1.5) | ||||||||||||

| 1000 | 0.128 | -0.022 | -0.051 | 0.021 | 0.007 | -0.022 | 0.327 | 0.064 | 0.166 | 0.049 | 0.050 | 0.062 |

| 2000 | 0.107 | -0.021 | -0.033 | 0.008 | 0.007 | -0.011 | 0.197 | 0.034 | 0.095 | 0.021 | 0.024 | 0.027 |

| 5000 | 0.103 | -0.019 | -0.037 | 0.004 | 0.004 | -0.005 | 0.097 | 0.025 | 0.065 | 0.009 | 0.011 | 0.012 |

| DGP: MARMA(1,1,0,0)-GARCH(1,1) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | ||||||||||

| AR(2)-GARCH(1,1) | MARMA(1,1,0,0)-GARCH(1,1) | |||||||||

| T | ||||||||||

| Dist: Exp(1) | ||||||||||

| 1000 | 0.893 | -0.143 | 0.023 | 0.358 | 0.542 | 0.675 | 0.218 | 0.012 | 0.108 | 0.828 |

| 2000 | 0.896 | -0.142 | 0.022 | 0.359 | 0.549 | 0.686 | 0.211 | 0.011 | 0.106 | 0.836 |

| 5000 | 0.899 | -0.141 | 0.021 | 0.359 | 0.558 | 0.695 | 0.204 | 0.011 | 0.104 | 0.843 |

| Dist: Student’s t(8) | ||||||||||

| 1000 | 0.896 | -0.141 | 0.013 | 0.115 | 0.820 | 0.685 | 0.211 | 0.012 | 0.102 | 0.836 |

| 2000 | 0.900 | -0.141 | 0.011 | 0.115 | 0.828 | 0.694 | 0.206 | 0.011 | 0.100 | 0.844 |

| 5000 | 0.899 | -0.140 | 0.011 | 0.115 | 0.830 | 0.698 | 0.201 | 0.010 | 0.101 | 0.846 |

| Dist: Student’s t(4.5) | ||||||||||

| 1000 | 0.897 | -0.140 | 0.016 | 0.180 | 0.736 | 0.685 | 0.212 | 0.013 | 0.111 | 0.825 |

| 2000 | 0.898 | -0.142 | 0.014 | 0.177 | 0.751 | 0.689 | 0.209 | 0.012 | 0.108 | 0.834 |

| 5000 | 0.901 | -0. 142 | 0.013 | 0.175 | 0.756 | 0.695 | 0.205 | 0.011 | 0.104 | 0.842 |

| Dist: Skew-t(4.5, 1.5) | ||||||||||

| 1000 | 0.897 | -0.144 | 0.017 | 0.222 | 0.683 | 0.678 | 0.219 | 0.012 | 0.111 | 0.825 |

| 2000 | 0.897 | -0.143 | 0.016 | 0.217 | 0.699 | 0.684 | 0.213 | 0.012 | 0.109 | 0.832 |

| 5000 | 0.899 | -0.140 | 0.015 | 0.214 | 0.708 | 0.695 | 0.204 | 0.011 | 0.104 | 0.843 |

| Standard Deviation | ||||||||||

| AR(2)-GARCH(1,1) | MARMA(1,1,0,0)-GARCH(1,1) | |||||||||

| T | ||||||||||

| Dist: Exp(1) | ||||||||||

| 1000 | 0.048 | 0.047 | 0.009 | 0.087 | 0.116 | 0.064 | 0.089 | 0.009 | 0.060 | 0.093 |

| 2000 | 0.036 | 0.036 | 0.006 | 0.060 | 0.077 | 0.048 | 0.065 | 0.005 | 0.041 | 0.054 |

| 5000 | 0.025 | 0.024 | 0.004 | 0.040 | 0.049 | 0.030 | 0.041 | 0.003 | 0.028 | 0.033 |

| Dist: Student’s t(8) | ||||||||||

| 1000 | 0.040 | 0.039 | 0.006 | 0.032 | 0.055 | 0.059 | 0.076 | 0.006 | 0.031 | 0.054 |

| 2000 | 0.032 | 0.030 | 0.004 | 0.021 | 0.034 | 0.038 | 0.053 | 0.004 | 0.021 | 0.033 |

| 5000 | 0.020 | 0.019 | 0.002 | 0.013 | 0.021 | 0.024 | 0.033 | 0.002 | 0.013 | 0.020 |

| Dist: Student’s t(4.5) | ||||||||||

| 1000 | 0.047 | 0.047 | 0.009 | 0.050 | 0.088 | 0.066 | 0.089 | 0.008 | 0.053 | 0.078 |

| 2000 | 0.037 | 0.037 | 0.005 | 0.036 | 0.053 | 0.049 | 0.068 | 0.005 | 0.040 | 0.050 |

| 5000 | 0.026 | 0.025 | 0.003 | 0.021 | 0.032 | 0.032 | 0.044 | 0.003 | 0.024 | 0.032 |

| Dist: Skew-t(4.5, 1.5) | ||||||||||

| 1000 | 0.050 | 0.048 | 0.009 | 0.063 | 0.103 | 0.067 | 0.090 | 0.010 | 0.065 | 0.094 |

| 2000 | 0.039 | 0.038 | 0.005 | 0.040 | 0.063 | 0.051 | 0.070 | 0.006 | 0.046 | 0.061 |

| 5000 | 0.028 | 0.027 | 0.003 | 0.025 | 0.037 | 0.036 | 0.049 | 0.003 | 0.028 | 0.036 |

| Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max | Skewness | Kurtosis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bitcoin | ||||||

| Price | 38384.650 | 15015.490 | 15787.280 | 73083.500 | 0.473 | 2.188 |

| Cubic Splines | 0.000 | 2190.830 | -8347.694 | 8712.283 | 0.034 | 4.210 |

| Fourier | 0.000 | 2177.264 | -19449.880 | 12595.560 | -0.874 | 13.362 |

| Ethereum | ||||||

| Price | 2324.600 | 888.746 | 730.368 | 4812.087 | 0.680 | 2.439 |

| Cubic Splines | 0.000 | 172.251 | -858.576 | 1003.885 | 0.193 | 6.543 |

| Fourier | 0.000 | 175.118 | -1433.179 | 1162.614 | -0.434 | 13.595 |

| Bitcoin | Ethereum | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Detrending method | ||||||||

| Cubic splines | Fourier | Cubic splines | Fourier | |||||

| Noncausal model | causal model | Noncausal model | causal model | Noncausal model | causal model | Noncausal model | causal model | |

| Parameters | MARMA(0,1,0,0) -GARCH(1,1) |

AR(1) -GARCH(1,1) |

MARMA(0,1,0,0) -GARCH(1,1) |

AR(1) -GARCH(1,1) |

MARMA(0,1,0,0) -GARCH(1,1) |

AR(1) -GARCH(1,1) |

MARMA(0,1,0,0) -GARCH(1,1) |

AR(1) -GARCH(1,1) |

| , | 0.8115 (0.0197) |

0.8115 (0.0197) |

0.8341 (0.0157) |

0.8341 (0.0157) |

0.8243 (0.1580) |

0.8243 (0.1580) |

0.8395 (0.0154) |

0.8395 (0.0154) |

| 0.0048 (0.0017) |

0.0029 (0.0010) |

0.0035 (0.0016) |

0.0031 (0.0011) |

0.0053 (0.0021) |

0.0056 (0.0017) |

0.0065 (0.0020) |

0.0057 (0.0018) |

|

| 0.0952 (0.0179) |

0.0564 (0.0106) |

0.0717 (0.0215) |

0.0593 (0.0117) |

0.0937 (0.0195) |

0.0828 (0.0147) |

0.1142 (0.0208) |

0.0856 (0.0156) |

|

| 0.9037 (0.0171) |

0.9406 (0.0102) |

0.9274 (0.0210) |

0.9382 (0.0111) |

0.9053 (0.0187) |

0.9137 (0.0141) |

0.8847 (0.0297) |

0.91158 (0.0149) |

|

| Residuals: Ljung Box test p-values | ||||||||

| Lag(1) | 0.7320 | 0.6234 | 0.3571 | 0.6033 | 0.5967 | 0.6533 | 0.4724 | 0.8152 |

| Lag(2) | 0.3611 | 0.2300 | 0.3124 | 0.1920 | 0.3602 | 0.1375 | 0.2636 | 0.1378 |

| Lag(3) | 0.2495 | 0.1177 | 0.1752 | 0.1663 | 0.1543 | 0.1506 | 0.0768 | 0.0861 |

| Lag(4) | 0.1799 | 0.1193 | 0.1608 | 0.1393 | 0.4288 | 0.1074 | 0.2514 | 0.1522 |

| Lag(5) | 0.2680 | 0.1801 | 0.2524 | 0.2210 | 0.1006 | 0.2217 | 0.1296 | 0.2971 |

| Standardized residuals: Mcleod-Li test p-values | ||||||||

| Lag(1) | 0.5715 | 0.4675 | 0.2073 | 0.3690 | 0.7695 | 0.7769 | 0.6491 | 0.9418 |

| Lag(2) | 0.7797 | 0.4635 | 0.4348 | 0.4882 | 0.8757 | 0.8125 | 0.8982 | 0.9142 |

| Lag(3) | 0.3872 | 0.2529 | 0.3059 | 0.3532 | 0.7137 | 0.5604 | 0.5430 | 0.5474 |

| Lag(4) | 0.5366 | 0.3933 | 0.4488 | 0.5099 | 0.8478 | 0.6703 | 0.6943 | 0.6602 |

| Lag(5) | 0.6540 | 0.3478 | 0.5191 | 0.5179 | 0.6248 | 0.4927 | 0.7015 | 0.4562 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).