1. Introduction

Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM), classified as WHO grade 4 gliomas, constitutes a considerable proportion of adult brain tumors, and is known for aggressiveness, brain invasion, rapid growth, necrosis, and short survival times [

1,

2]. Median age at diagnosis is 64 years, and the 5-year relative survival rate is about 5% [

3,

4,

5,

6]. Standard treatment after maximal surgical resection is radiotherapy combined with concurrent and concomitant temozolomide [

7]. Heterogeneity and hypoxia combined with patterns of brain invasion and angiogenesis are responsible for the feature of GBM on pathological examination and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)–necrosis, rapidly dividing cells, and brain invasion [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14].

The current guidelines recommend that patients with GBM undergo an early post-operative MRI (EPMRI) within 48 to 72 hours after surgery to assess the extent of resection [

15]. Subsequent surveillance MRIs should be done every 3 to 6 months to monitor for disease progression [

16]. The Response Assessment in Neuro-Oncology (RANO) criteria have now become the standard for evaluating GBM response in clinical trials. Based on RANO criteria, true progression is defined as a ≥25% increase in the sum of the products of perpendicular diameters of enhancing lesions, the appearance of new lesions, or clinical deterioration [

17]. Stable disease indicates the absence of significant change in tumor size or appearance of new lesions [

17]. The short-term effects of current standard-of-care treatments necessitate regular monitoring through longitudinal MRI to detect any signs of progression [

18]. In current clinical workflows, tumor progression is traditionally assessed through visual inspection by radiologists and neuro-oncologists, a method that has long been regarded as the clinical gold standard. However, visual inspection is inherently subjective and prone to inter-observer variability, especially because of the inability to accurately quantify and assess tumor volumes [

19].

Pseudoprogression (PsPD) is considered a transient radiologic change mimicking progression, typically occurring within 3 months post-chemoradiotherapy [

17]. PsPD is significantly correlated with MGMT methylated status [

20,

21]. Differentiating true progression from PsPD is challenging, necessitating careful interpretation of imaging findings in conjunction with clinical assessment [

22]. There is an overlap between the imaging presentations of the radiation-induced PsPD and true disease progression on conventional MRI [

23]; advanced imaging modalities, like perfusion are also with limitations in distinguishing true progression from PSPD [

24,

25]. Improvement in the early recognition of PsPD is crucial to accurate diagnosis and to reducing biases in evaluating the results of clinical trials [

26].

Radiologists typically do not include GBM volume measurement in their workflow due to the time-consuming nature of traditional manual contouring platforms and the significant inter-user variability they introduce. Recent advances in artificial intelligence combined with the FDA approval of the MRIMath platform bring timely and accurate volumetric measurements within reach [

27,

28]. The MRIMath platform includes a T1c AI with 95% accuracy and a time-efficient Smart manual contouring platform with < 5% inter-user variability to review and revise, when needed [

27,

28].

Here, we evaluate the efficacy of volumetric analysis using the MRIMath platform in detecting GBM progression as compared to current standard clinical evaluation. We hypothesize that volumetric analysis is more efficient than visual inspection at detecting GBM progression. Previous studies have shown the benefits of volumetric analysis combined with the online change-of-point statistical method in detecting low-grade-glioma (LGG) tumor growth significantly earlier than visual inspection [

19,

29]; Fathallah-Shaykh et al. applied the computationally intensive method of non-negative matrix factorization to segment LGG [

30]. Here, we use an accurate and efficient AI that generates segmentations in seconds, followed by human review.

For volumetric assessment, we apply the change-of-point method to determine the first point of statistically significant growth. The change-of-point method applies the same rigorous statistical standard to all patients and studies and determines if a current measurement is significantly different from all the measurements of the same patient [

19,

29]

.

2. Materials and Methods

Ethical Approval

The Institutional Review Board of the University of Alabama at Birmingham approved the research; waiver of informed consent was granted because the research involved no greater than minimal risk and no procedures for which written consent is normally required outside the research context.

Study Design and Patient Selection

Fifty-eight patients diagnosed with GBM were seen at the neuro-oncology clinics of the University of Alabama at Birmingham. The inclusion criteria are: 1) older than 18 years of age, 2) pathological diagnosis of GBM, 3) standard radiation therapy post-operatively, 4) baseline MRI brain, with and without contrast, done 3-8 weeks post-radiation, 5) at least 2 stable MRIs of the brain, with and without contrast, are performed after the completion of radiation therapy, and 4) at least 4 longitudinal MRIs, with and without contrast, starting from the baseline MRI are available for review. The exclusion criteria are: 1) Intracranial bleeding, 2) new stroke, 3) missing slices in the T1C and FLAIR series in any of the longitudinal MRIs, 4) neurosurgical intervention for any reason after radiation and before tumor growth, 5) treatment with Bevacizumab, 6) placement of intracranial wafers. A total of 15 of 58 cases met the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Time to Growth Detected by Standard Clinical Care

Clinical growth time is defined as the time when the treating neuro-oncologist informs the patient/family of a significant change in tumor status and makes a new treatment decision or makes a diagnosis of PsPD. The results of the independent evaluations of the longitudinal MRIs by the radiologists and the treating neuro-oncologists were extracted from the clinical records.

Tumor Segmentation, Volume Calculation, and Physician Review

MRI scans were uploaded to the MRIMath platform, resized to 256x256, and segmented by the MRIMath GBM T1c AI. AI segmentation results were reviewed by a Board-certified neuro-oncologist using the MRIMath Smart contouring platform to view and modify the contours.

Tumor volumes were calculated by applying the following equation:

Where x, y, and z correspond to x-spacing, y-spacing, and spacing between slices, respectively.

Online Change-of-Point Detection

To exclude changes due to the evolution of post-surgical changes, the baseline volume in the longitudinal series was the first minimum after surgical resection. To identify an abrupt change of volume, we applied a change in the root-mean-square level at a minimum threshold of 500/(volume at baseline) and a minimum of 2 samples between change points. The number 500 corresponds to 5% of the rounded median of the baseline volume.

Statistical Methods

Descriptive statistics are calculated using Matlab (Natick, MA).

3. Results

Patient Characteristics

Fifteen patients met the inclusion criteria; 7 females and 8 males, ages ranging from 51-86 years (median 65 years). Molecular testing revealed IDH1 wild type in 8 cases; IDH1 status was unknown in the remaining 7. The MGMT promoter was methylated in 4 cases and unmethylated in 4 cases. The status of the MGMT promoter was unknown in 7 cases. Patients were treated with the standard radiation with concurrent and concomitant Temozolomide (n=13) or radiation and nivolumab (n=2).

Growth Detection

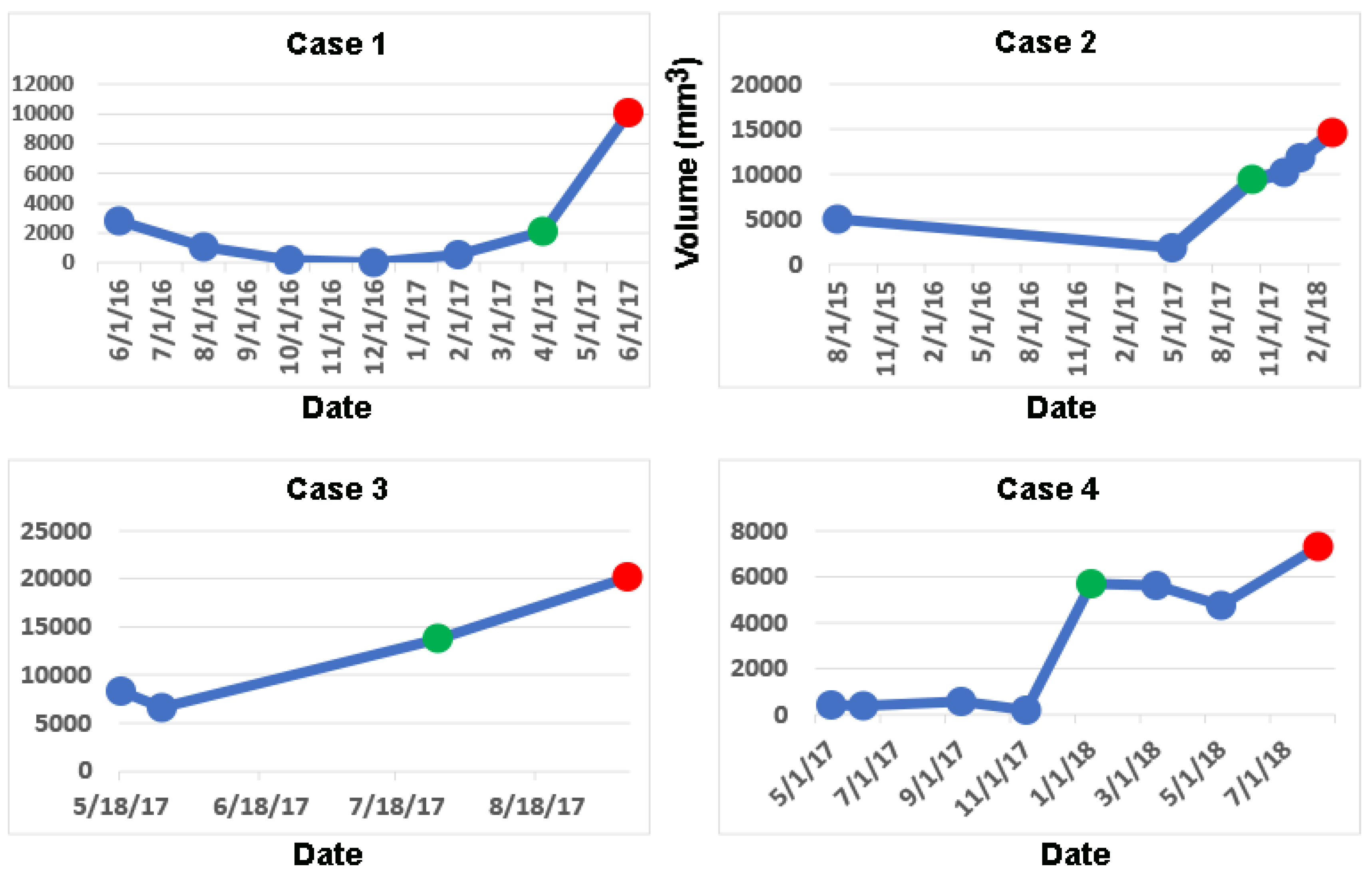

Computing longitudinal volumes and applying the online change-of-point method detects a significant change in volume earlier than clinical notes in 4/15 GBM cases, median = 105 days, mean = 56 days (

Table 1). The longitudinal volumetric plots of these 4 cases are shown in

Figure 1 (green dots). Their percent change in volume from baseline and the clinical evaluations of the MRI at the times of detection of tumor growth by the change-of-point method are shown in

Table 2.

In case 1, an increase of volume of 86% was interpreted as stable independently by both the radiologist and the neuro-oncologist (

Table 2 and

Figure 1). In case 2, an increase in volume of 295% was interpreted as treatment effect by the radiologist and slight change by the neuro-oncologist (see

Table 2 and

Figure 1); the latter did not initiate any new clinical actions. In case 3, an increase in volume by 107% was interpreted as mild progression by both the radiologist and neuro-oncologist (

Table 2 and

Figure 1); the latter did not modify the clinical management. In case 4, an increase in volume of 2,843% was interpreted as stable by the neuro-oncologist; a radiological report was not available (

Table 2 and

Figure 1). In these 4 cases, the treating neuro-oncologists informed the patients and their families of progression and started new clinical actions at the dates corresponding to the red dots in

Figure 1 at a median delay of 116 days (

Table 1).

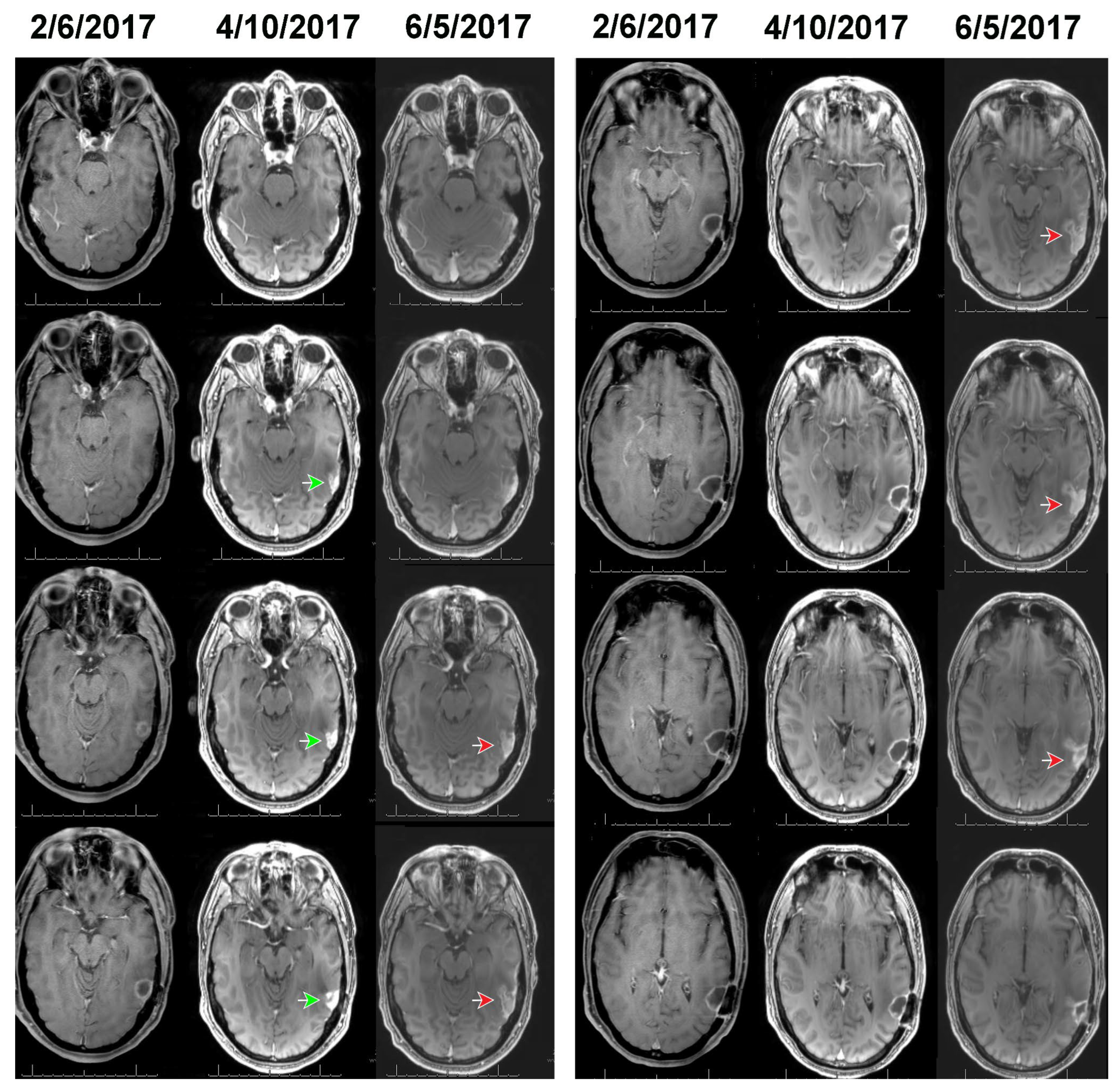

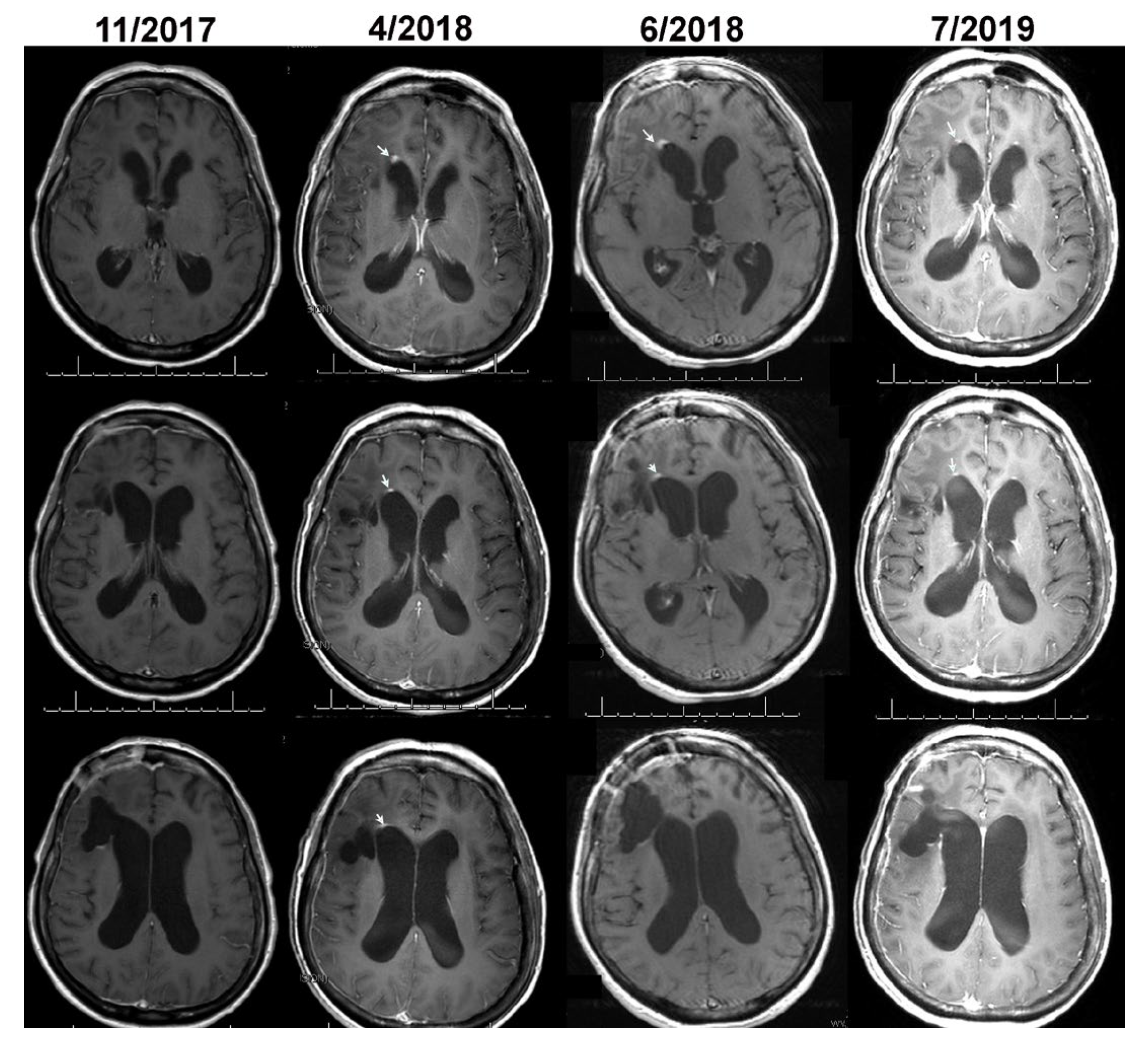

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 show, respectively, the images of cases 1 and 2, before, at the time, and after detection of growth by volumetric analysis using the change-of-point method. The MRI of case 1 on 2/6/2017 reveals a surgical bed with linear enhancement along its margins (

Figure 2). The MRI on 4/10/2017 reveals new nodular enhancement at the time of detection of tumor progression by volumetric analysis (

Figure 2, green arrows). The neuro-oncologist diagnosed progression on 6/5/2017 (

Figure 2 red arrows).

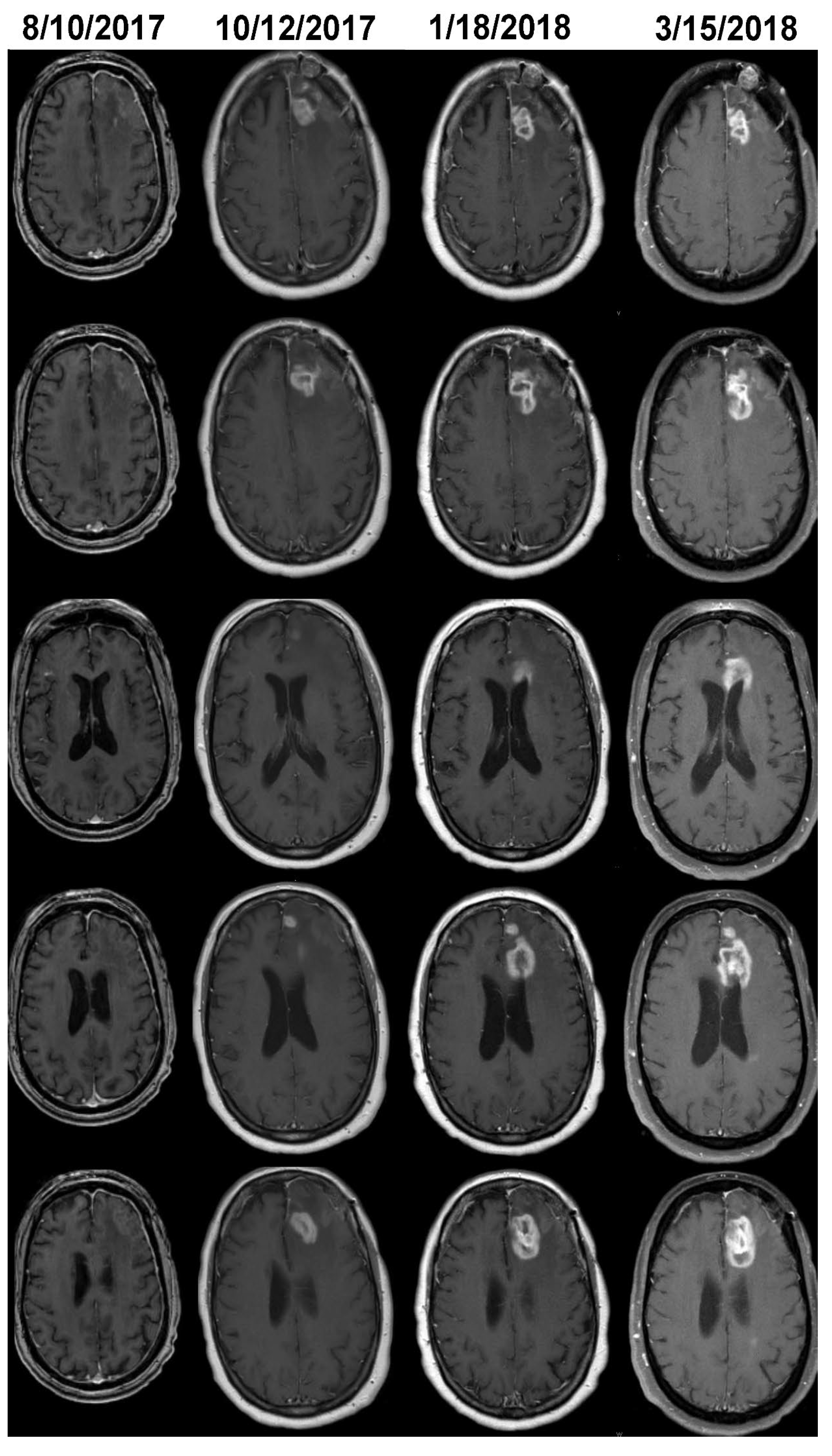

The MRI of case 2 on 8/10/2017 reveals a surgical bed with linear enhancement along its margin (

Figure 3). The neuro-oncologist diagnosed progression on 3/15/2017 (

Figure 3). Volumetric analysis detected growth on 10/12/2017 (

Figure 3); additional GBM growth can be seen on 1/18/2018; the treating neuro-oncologist did not change the clinical management until 3/15/2018. In case 4, tumor volume was stable for 6 months after the initial growth detected by the change-of-point method; this appears to be secondary to either an initial period of PsPD followed by real growth or nonlinear growth (

Figure 1).

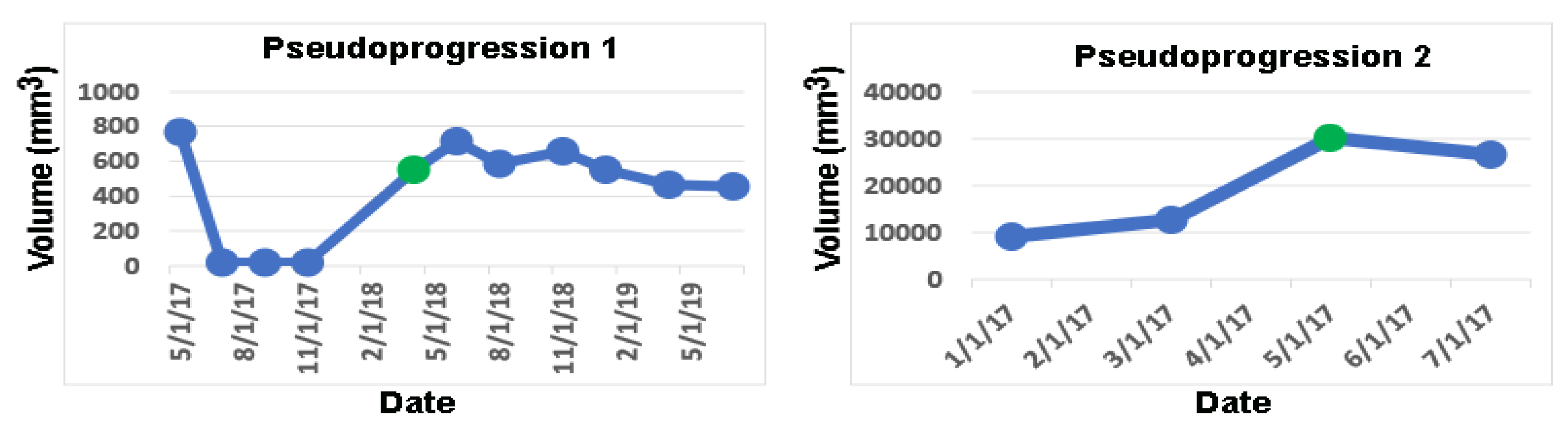

In the 11 remaining cases, the change-of-point method detects tumor progression on the same dates as the dates of tumor progression or PsPD diagnosed by the neuro-oncologists. In 2/11 cases, the neuro-oncologists diagnosed PsPD, which is validated by volumetric analysis as the volumes remain stable after the initial increase (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5).

4. Discussion

Our results support the hypothesis that longitudinal volumetric analysis is superior to visual inspection in detecting GBM progression. A delay of 2-3 months in diagnosing growth of GBM may lead to shortened survival times and diminished quality of life because of rapid growth rates. By examining the clinical notes and radiological reports, we find that even though a tumor change was detected in some cases, clinicians were hampered because of the inability to accurately quantify the changes in tumor volumes by visual inspection. Statements like “slight change” were common when tumor volumes increased more than 50% (see

Table 1). Because of the ambiguity of the radiological evaluations, in this study, the dates of progression are chosen to be the dates that the neuro-oncologists informed the patients and families and initiated new clinical actions or diagnosed PsPD. The uncertainty that arises from the inability to accurately quantify tumor volumes leads to inappropriately extending the observational period causing additional tumor growth, and brain invasion (

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3).

The RANO criteria are the standard for detecting GBM progression in clinical trial settings. However, notable RANO criteria limitations persist. A significant challenge is the reliance on two-dimensional measurements of contrast-enhancing tumor regions, which may not accurately represent the complex three-dimensional tumor architecture, potentially leading to inconsistent assessments and inter-observer variation [

31]. Three-dimensional (3D) volumetric measurements offer several advantages over traditional two-dimensional 2D RANO criteria, in monitoring GBM. Unlike 2D methods, which may not accurately capture the complex, irregular shapes of GBM tumors, 3D volumetric analysis provides a more precise representation of tumor size and morphology [

29]. Another significant limitation is that the measurements depend on the operator’s discretion in determining the perpendicular diameter of the largest tumor cross-section. Similarly, volumetric analysis was shown to be superior to other established tumor classification criteria, such as the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) and modified RECIST [

32]. Specifically, these established criteria underestimate tumor response due to their tendency to oversimplify a multidimensional and heterogeneous tumor, particularly one with necrosis [

33]. Poor performance of the RANO and RECIST criteria compared to both visual and volumetric ground truths suggests that alternative methods of evaluating tumor progression and response should be considered for both research and clinical use. The volumetric statistical change-of-point method has been previously validated and is considered more accurate than both visual assessment and the RANO criteria for diagnosing progression of low-grade gliomas [

19,

29]. Instead of relying on a speculative percentage threshold, the change-of-point method employs rigorous statistical criteria to identify a significant change in volume.

Few published studies have compared standard 2D measurements of glioma status, radiologists’ interpretations, and volumetric measurements. Fathallah-Shaykh et al. and Fabio et al. have shown that volumetric measurements, when combined with the change-of-point method, detect growth in low-grade gliomas significantly earlier than both radiologists’ interpretations and traditional 2D measurements [

19,

29]. In an abstract, Khalili et al. report that in 3 out of 6 pediatric gliomas, volumetric measurements detected tumor progression significantly earlier than both the current standard 2D measurements and radiologists’ interpretations. [

34]

. In another study on pediatric low-grade gliomas, volumetric analysis of solid tumors proved significantly more effective than 2D measurements in diagnosing tumor progression, as determined by the Brain Tumor Reporting and Data System (BT-RADS) criteria [

35]

. An analysis of the Phase I trial of ivosidenib for low-grade glioma demonstrated that 3D volumetric measurements outperform 2D measurements in response assessment. This is due to their more stable tumor growth rate measures, higher inter-reader agreement, and lower rates of reader discordance [

36]

. Dempsey et al. tested 1D, 2D, and 3D measurements of recurrent gliomas and found that only the volumetric measurement of tumor size was predictive of survival in recurrent malignant glioma [

37]

. To our knowledge, our study is one of the few demonstrating the superiority of 3D AI-assisted volumetric measurements of adult GBM compared to radiologists’ interpretations. Further research is needed to compare AI-assisted 3D volumetric measurements with the standard 2D RANO criteria. With the advancement of efficient AI-assisted devices and a reliable human review platform, we believe that 3D volumetric measurements will significantly enhance glioma management, leading to improved morbidity, longer survival times, and more accurate clinical trial outcomes.

Distinguishing true progression from remains challenging for both radiologists and neuro-oncologists. Conventional MRI has limited value for distinguishing true progression from PsPD of GBM [

38]. Overall interpretation of MR scans using perfusion weighted images in GBM is hampered by poor interobserver agreement on quantitative cerebral blood flow measurements and on interpretability of perfusion images [

24]. Furthermore, visual inspection of cerebral blood volume maps has limited value in differentiating PsPD from true progression in GBM [

24]. Additional imaging modalities that have been investigated with mixed results include diffusion weighted images, magnetic resonance spectroscopy, and radiomics [

25]. Volumetric analysis is an important tool that validates the diagnosis of PsPD by confirming volume stability in subsequent short-interval scans (

Figure 4).

As compared to the other methods for automated segmentation of GBM, the MRIMath FLAR AI is noted for being fully automated by not including preprocessing steps that require human supervision, like deboning, interpolation, and registration [

39,

40,

41]. This automation significantly simplifies the preprocessing pipeline. Furthermore, while MRIMath© processes images in 2D and treats the FLAIR and T1C modalities independently, other methods employ a 3D approach and integrate the four modalities, T1, T1c, T2, and FLAIR [

27,

39,

42]. The MRIMath© AI contrasts with the subcomponent segmentations used by the other platforms.

In this study, we used MRIMath© Smart contouring platform to review, revise and approve the AI-powered segmentations. This platform is associated with a low inter-user variability of less than 5% for T1c images [

27] while the manual delineation of the gross tumor volume of GBM is associated with moderate inter-user variability [

38,

43]. The variability of the reviewing software is important because a high variability in volume measurements could lead to delayed or inaccurate diagnosis of tumor progression.

Accurate volumetric measurements of GBM play are essential for translating mathematical models into clinical practice [

8,

9,

10]. These multiscale models mirror the pathological, radiological, and clinical features of GBM. They can also be applied to perform computational (in silico) trials. By analyzing the volume data of a patient, model parameters can be calculated, allowing for the individualized prediction of future outcomes.

5. Conclusions

Our results support the hypothesis that volumetric analysis allows physicians to detect GBM progression earlier than visual inspection. Furthermore, the findings suggest that volumetric analysis may be applied to validate the diagnosis of PsPD by demonstrating stability in short-interval imaging. Earlier diagnosis of GBM true progression and PsPD is expected to lower morbidity, prolong survival times and improve the accuracy of clinical trials data analysis. This study emphasizes the enhanced diagnostic accuracy achieved by incorporating volumetric data analysis into clinical decision-making. This can be accomplished by integrating efficient AI-powered segmentation and a streamlined human review system into the clinical workflow.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.M.F.S., H.S.; and N.B., methodology, Y.B., N.B., H.S., and H.M.F.S.; software, Y.B.; validation, M.B., A.W., J.K., F.E.M., F.R., L.B.N., J.B.P., B.K.T., J.H.T., V.V.R., and H.M.F.S.; formal analysis, H.M.F.S, H.S., L.B.N. M.B., and N.B.; investigation, H.M.F.S, H.S., L.B.N., M.B., and N.B.; resources, Y.B., H.M.F.S., N.B., H.S.; data curation, Y.B., H.M.F.S., N.B., H.S., J.B.P, B.K.T., J.H.T., V.V.R.; writing—original draft preparation, H.M.F.S., H.S., and N.B.; writing—review and editing, Y.B., H.S., M.B., A.W., J.K., F.E.M., F.R., N.B., L.B.N., J.B.P, B.K.T., J.H.T., V.V.R., H.M.F.S., visualization, Y.B., H.S., M.B., A.W., J.K., F.E.M., F.R., N.B., L.B.N., J.B.P, B.K.T., J.H.T., V.V.R., H.M.F.S.; supervision, H.S., N.B., and H.M.F.S.; project administration, H.S., N.B. and H.M.F.S.; funding acquisition, H.M.F.S and N.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Cancer Institute, Phase II SBIR contract number 75N91022C00051.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The institutional Review Board of the University of Alabama at Birmingham approved the research (IRB-150618007);

Informed Consent Statement

Waiver of informed consent was granted because the research involved no greater than minimal risk and no procedures for which written consent is normally required outside the research context.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the corresponding author on request.

Acknowledgments

In this section, you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments).

Conflicts of Interest

Y.B. is employed by MRIMath. H.M.F.S. and N.B. are co-founders of MRIMath.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GBM |

Glioblastomas |

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| PsPD |

Pseudoprogression |

| LGG |

Low-grade-glioma |

| MRI |

Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

References

- Omuro, A.; DeAngelis, L.M. Glioblastoma and other malignant gliomas: a clinical review. JAMA 2013, 310, 1842-1850, doi:10.1001/jama.2013.280319. [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, Q.T.; Gittleman, H.; Stetson, L.; Virk, S.; Barnholtz-Sloan, J.S. Epidemiology of Intracranial Gliomas. Prog Neurol Surg 2018, 30, 1-11, doi:10.1159/000464374. [CrossRef]

- Grochans, S.; Cybulska, A.M.; Siminska, D.; Korbecki, J.; Kojder, K.; Chlubek, D.; Baranowska-Bosiacka, I. Epidemiology of Glioblastoma Multiforme-Literature Review. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14, doi:10.3390/cancers14102412. [CrossRef]

- Baldi, I.; Huchet, A.; Bauchet, L.; Loiseau, H. [Epidemiology of glioblastoma]. Neurochirurgie 2010, 56, 433-440, doi:10.1016/j.neuchi.2010.07.011. [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, Q.T.; Bauchet, L.; Davis, F.G.; Deltour, I.; Fisher, J.L.; Langer, C.E.; Pekmezci, M.; Schwartzbaum, J.A.; Turner, M.C.; Walsh, K.M.; et al. The epidemiology of glioma in adults: a “state of the science” review. Neuro Oncol 2014, 16, 896-913, doi:10.1093/neuonc/nou087. [CrossRef]

- Tamimi, A.F.; Juweid, M. Epidemiology and Outcome of Glioblastoma. In Glioblastoma, De Vleeschouwer, S., Ed.; Brisbane (AU), 2017.

- Stupp, R.; Mason, W.P.; van den Bent, M.J.; Weller, M.; Fisher, B.; Taphoorn, M.J.; Belanger, K.; Brandes, A.A.; Marosi, C.; Bogdahn, U.; et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med 2005, 352, 987-996, doi:10.1056/NEJMoa043330. [CrossRef]

- Scribner, E.; Saut, O.; Province, P.; Bag, A.; Colin, T.; Fathallah-Shaykh, H.M. Effects of anti-angiogenesis on glioblastoma growth and migration: model to clinical predictions. PLoS One 2014, 9, e115018, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0115018. [CrossRef]

- Scribner, E.; Hackney, J.R.; Machemehl, H.C.; Afiouni, R.; Patel, K.R.; Fathallah-Shaykh, H.M. Key rates for the grades and transformation ability of glioma: model simulations and clinical cases. J Neurooncol 2017, 133, 377-388, doi:10.1007/s11060-017-2444-6. [CrossRef]

- Raman, F.; Scribner, E.; Saut, O.; Wenger, C.; Colin, T.; Fathallah-Shaykh, H.M. Computational Trials: Unraveling Motility Phenotypes, Progression Patterns, and Treatment Options for Glioblastoma Multiforme. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0146617, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0146617. [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Araysi, L.M.; Fathallah-Shaykh, H.M. c-Src and neural Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein (N-WASP) promote low oxygen-induced accelerated brain invasion by gliomas. PLoS One 2013, 8, e75436, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0075436. [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Zhang, W.; Yang, X.; Wheeler, C.G.; Langford, C.P.; Wu, L.; Filippova, N.; Friedman, G.K.; Ding, Q.; Fathallah-Shaykh, H.M.; et al. The role of Src family kinases in growth and migration of glioma stem cells. Int J Oncol 2014, 45, 302-310, doi:10.3892/ijo.2014.2432. [CrossRef]

- Torrisi, F.; Vicario, N.; Spitale, F.M.; Cammarata, F.P.; Minafra, L.; Salvatorelli, L.; Russo, G.; Cuttone, G.; Valable, S.; Gulino, R.; et al. The Role of Hypoxia and SRC Tyrosine Kinase in Glioblastoma Invasiveness and Radioresistance. Cancers (Basel) 2020, 12, doi:10.3390/cancers12102860. [CrossRef]

- Scribner, E.; Fathallah-Shaykh, H.M. Single Cell Mathematical Model Successfully Replicates Key Features of GBM: Go-Or-Grow Is Not Necessary. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0169434, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0169434. [CrossRef]

- Booth, T.C.; Luis, A.; Brazil, L.; Thompson, G.; Daniel, R.A.; Shuaib, H.; Ashkan, K.; Pandey, A. Glioblastoma post-operative imaging in neuro-oncology: current UK practice (GIN CUP study). Eur Radiol 2021, 31, 2933-2943, doi:10.1007/s00330-020-07387-3. [CrossRef]

- Collaborative, I.-G.; Neurology; Neurosurgery Interest, G.; British Neurosurgical Trainee Research, C. Imaging timing after surgery for glioblastoma: an evaluation of practice in Great Britain and Ireland (INTERVAL-GB)- a multi-centre, cohort study. J Neurooncol 2024, 169, 517-529, doi:10.1007/s11060-024-04705-3. [CrossRef]

- Leao, D.J.; Craig, P.G.; Godoy, L.F.; Leite, C.C.; Policeni, B. Response Assessment in Neuro-Oncology Criteria for Gliomas: Practical Approach Using Conventional and Advanced Techniques. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2020, 41, 10-20, doi:10.3174/ajnr.A6358. [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, C.S.; Bligh, E.R.; Poon, M.T.C.; Solomou, G.; Islim, A.I.; Mustafa, M.A.; Rominiyi, O.; Williams, S.T.; Kalra, N.; Mathew, R.K.; et al. Imaging timing after glioblastoma surgery (INTERVAL-GB): protocol for a UK and Ireland, multicentre retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e063043, doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2022-063043. [CrossRef]

- Fathallah-Shaykh, H.M.; DeAtkine, A.; Coffee, E.; Khayat, E.; Bag, A.K.; Han, X.; Warren, P.P.; Bredel, M.; Fiveash, J.; Markert, J.; et al. Diagnosing growth in low-grade gliomas with and without longitudinal volume measurements: A retrospective observational study. PLoS Med 2019, 16, e1002810, doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1002810. [CrossRef]

- Chamberlain, M.C. Pseudoprogression in glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol 2008, 26, 4359; author reply 4359-4360, doi:10.1200/JCO.2008.18.4440. [CrossRef]

- Brandes, A.A.; Franceschi, E.; Tosoni, A.; Blatt, V.; Pession, A.; Tallini, G.; Bertorelle, R.; Bartolini, S.; Calbucci, F.; Andreoli, A.; et al. MGMT promoter methylation status can predict the incidence and outcome of pseudoprogression after concomitant radiochemotherapy in newly diagnosed glioblastoma patients. J Clin Oncol 2008, 26, 2192-2197, doi:10.1200/JCO.2007.14.8163. [CrossRef]

- Le Fevre, C.; Lhermitte, B.; Ahle, G.; Chambrelant, I.; Cebula, H.; Antoni, D.; Keller, A.; Schott, R.; Thiery, A.; Constans, J.M.; et al. Pseudoprogression versus true progression in glioblastoma patients: A multiapproach literature review: Part 1 - Molecular, morphological and clinical features. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2021, 157, 103188, doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2020.103188. [CrossRef]

- Brandsma, D.; Stalpers, L.; Taal, W.; Sminia, P.; van den Bent, M.J. Clinical features, mechanisms, and management of pseudoprogression in malignant gliomas. Lancet Oncol 2008, 9, 453-461, doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70125-6. [CrossRef]

- Kerkhof, M.; Tans, P.L.; Hagenbeek, R.E.; Lycklama, A.N.G.J.; Holla, F.K.; Postma, T.J.; Straathof, C.S.; Dirven, L.; Taphoorn, M.J.; Vos, M.J. Visual inspection of MR relative cerebral blood volume maps has limited value for distinguishing progression from pseudoprogression in glioblastoma multiforme patients. CNS Oncol 2017, 6, 297-306, doi:10.2217/cns-2017-0013. [CrossRef]

- Sidibe, I.; Tensaouti, F.; Roques, M.; Cohen-Jonathan-Moyal, E.; Laprie, A. Pseudoprogression in Glioblastoma: Role of Metabolic and Functional MRI-Systematic Review. Biomedicines 2022, 10, doi:10.3390/biomedicines10020285. [CrossRef]

- Strauss, S.B.; Meng, A.; Ebani, E.J.; Chiang, G.C. Imaging Glioblastoma Posttreatment: Progression, Pseudoprogression, Pseudoresponse, Radiation Necrosis. Neuroimaging Clin N Am 2021, 31, 103-120, doi:10.1016/j.nic.2020.09.010. [CrossRef]

- Barhoumi, Y.; Fattah, A.H.; Bouaynaya, N.; Moron, F.; Kim, J.; Fathallah-Shaykh, H.M.; Chahine, R.A.; Sotoudeh, H. Robust AI-Driven Segmentation of Glioblastoma T1c and FLAIR MRI Series and the Low Variability of the MRIMath(c) Smart Manual Contouring Platform. Diagnostics (Basel) 2024, 14, doi:10.3390/diagnostics14111066. [CrossRef]

- Ce, M.; Irmici, G.; Foschini, C.; Danesini, G.M.; Falsitta, L.V.; Serio, M.L.; Fontana, A.; Martinenghi, C.; Oliva, G.; Cellina, M. Artificial Intelligence in Brain Tumor Imaging: A Step toward Personalized Medicine. Curr Oncol 2023, 30, 2673-2701, doi:10.3390/curroncol30030203. [CrossRef]

- Raman, F.; Mullen, A.; Byrd, M.; Bae, S.; Kim, J.; Sotoudeh, H.; Moron, F.E.; Fathallah-Shaykh, H.M. Evaluation of RANO Criteria for the Assessment of Tumor Progression for Lower-Grade Gliomas. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15, doi:10.3390/cancers15133274. [CrossRef]

- Dera, D.a.R., Fabio and Bouaynaya, Nidhal and Fathallah-Shaykh, Hassan M. Interactive Semi-automated Method Using Non-negative Matrix Factorization and Level Set Segmentation for the BRATS Challenge. In Brainlesion: Glioma, Multiple Sclerosis, Stroke and Traumatic Brain Injuries, Crimi, A.a.M., Bjoern and Maier, Oskar and Reyes, Mauricio and Winzeck, Stefan and Handels, Heinz, Ed.; Springer International Publishing: 2016; pp. 195-205.

- Ramakrishnan, D.; von Reppert, M.; Krycia, M.; Sala, M.; Mueller, S.; Aneja, S.; Nabavizadeh, A.; Galldiks, N.; Lohmann, P.; Raji, C.; et al. Evolution and implementation of radiographic response criteria in neuro-oncology. Neurooncol Adv 2023, 5, vdad118, doi:10.1093/noajnl/vdad118. [CrossRef]

- Hajkova, M.; Andrasina, T.; Ovesna, P.; Rohan, T.; Dostal, M.; Valek, V.; Ostrizkova, L.; Tucek, S.; Sedo, J.; Kiss, I. Volumetric Analysis of Hepatocellular Carcinoma After Transarterial Chemoembolization and its Impact on Overall Survival. In Vivo 2022, 36, 2332-2341, doi:10.21873/invivo.12964. [CrossRef]

- Eisenhauer, E.A.; Therasse, P.; Bogaerts, J.; Schwartz, L.H.; Sargent, D.; Ford, R.; Dancey, J.; Arbuck, S.; Gwyther, S.; Mooney, M.; et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer 2009, 45, 228-247, doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [CrossRef]

- Khalili, N.K., A.F.; Bagheri, S.; Familiar, A.; Viswanathan, K.; Anderson, H.; Haldar, D.; Ware, J.B.; Vossough, A.; Ali Nabavizadeh, A. Volumetric measurment of tumor size outperforms standard two-dimensional method in early prediction of tumor progression in pediatric glioma. Neuro-Oncology 2023, 25, i48.

- von Reppert, M.; Ramakrishnan, D.; Bruningk, S.C.; Memon, F.; Abi Fadel, S.; Maleki, N.; Bahar, R.; Avesta, A.E.; Jekel, L.; Sala, M.; et al. Comparison of volumetric and 2D-based response methods in the PNOC-001 pediatric low-grade glioma clinical trial. Neurooncol Adv 2024, 6, vdad172, doi:10.1093/noajnl/vdad172. [CrossRef]

- Ellingson, B.M.; Kim, G.H.J.; Brown, M.; Lee, J.; Salamon, N.; Steelman, L.; Hassan, I.; Pandya, S.S.; Chun, S.; Linetsky, M.; et al. Volumetric measurements are preferred in the evaluation of mutant IDH inhibition in non-enhancing diffuse gliomas: Evidence from a phase I trial of ivosidenib. Neuro Oncol 2022, 24, 770-778, doi:10.1093/neuonc/noab256. [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, M.F.; Condon, B.R.; Hadley, D.M. Measurement of tumor “size” in recurrent malignant glioma: 1D, 2D, or 3D? AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2005, 26, 770-776.

- Vos, M.J.; Uitdehaag, B.M.; Barkhof, F.; Heimans, J.J.; Baayen, H.C.; Boogerd, W.; Castelijns, J.A.; Elkhuizen, P.H.; Postma, T.J. Interobserver variability in the radiological assessment of response to chemotherapy in glioma. Neurology 2003, 60, 826-830, doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000049467.54667.92. [CrossRef]

- Abayazeed, A.H.; Abbassy, A.; Mueller, M.; Hill, M.; Qayati, M.; Mohamed, S.; Mekhaimar, M.; Raymond, C.; Dubey, P.; Nael, K.; et al. NS-HGlio: A generalizable and repeatable HGG segmentation and volumetric measurement AI algorithm for the longitudinal MRI assessment to inform RANO in trials and clinics. Neurooncol Adv 2023, 5, vdac184, doi:10.1093/noajnl/vdac184. [CrossRef]

- Menze, B.H.; Jakab, A.; Bauer, S.; Kalpathy-Cramer, J.; Farahani, K.; Kirby, J.; Burren, Y.; Porz, N.; Slotboom, J.; Wiest, R.; et al. The Multimodal Brain Tumor Image Segmentation Benchmark (BRATS). IEEE Trans Med Imaging 2015, 34, 1993-2024, doi:10.1109/TMI.2014.2377694. [CrossRef]

- Hatamizadeh, A.; Nath, V.; Tang, Y.; Yang, D.; Roth, H.R.; Xu, D. Swin UNETR: Swin Transformers for Semantic Segmentation of Brain Tumors in MRI Images. ArXiv 2022, abs/2201.01266.

- Jia, Z.; Zhu, H.; Zhu, J.; Ma, P. Two-Branch network for brain tumor segmentation using attention mechanism and super-resolution reconstruction. Comput Biol Med 2023, 157, 106751, doi:10.1016/j.compbiomed.2023.106751. [CrossRef]

- Wee, C.W.; Sung, W.; Kang, H.C.; Cho, K.H.; Han, T.J.; Jeong, B.K.; Jeong, J.U.; Kim, H.; Kim, I.A.; Kim, J.H.; et al. Evaluation of variability in target volume delineation for newly diagnosed glioblastoma: a multi-institutional study from the Korean Radiation Oncology Group. Radiat Oncol 2015, 10, 137, doi:10.1186/s13014-015-0439-z. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).