Submitted:

04 January 2025

Posted:

06 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has revolutionized the creative process, allowing for novel ways of artistic expression. This paper focuses on the intersection of Abstract Expressionism and AI-generated imagery, exploring how poetic prompts inspire unique visual interpretations. By utilizing Leonardo AI with a medium contrast and leveraging the cinematic kino model/preset, the research demonstrates how simple poetic phrases can yield profound visual artworks. The study evaluates the quality, creativity, and emotional resonance of AI-generated art, offering insights into the synergy between human creativity and machine intelligence within an Abstract Expressionism framework. The Leonardo AI is applied to Ismail A Mageed’s internal monologues in poetic form. The paper ends with some potential open problems and concludes with remarks and future research pathways.

Keywords:

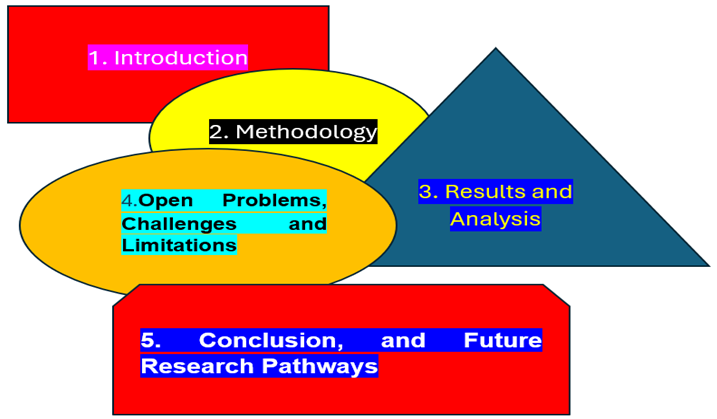

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Internal Monologues in Poetic Form Source

- IMPF 1

- Between Life and No-Life

- By the pen of Ismail A Mageed

- Our hearts are like metals… some are precious, and some are not! Some are softer than dewdrops on the cheeks of roses...

- And some are harder than rocks… yet some rocks soften out of mercy and crack to release the gentleness and magnificence of beauty.

- Our hearts are within our bodies… we use them to interact with people!

- But have you ever heard of a heart that contains a person?

- Do not be surprised, my friend!

- Each of us needs a heart that contains a person to truly appreciate the beauty around us.

- To spread mercy to all beings.

- Ah, heart, I am perplexed about how to describe you!

- Are you just a small piece between the ribs, beating to tell others we are alive?

- Why all this silence?

- Quiet at night, I see you.

- Speak, O heart! So that the darkness of the night may vanish with the strength of your faith in God,

- The Most Knowledgeable, the Highest...

- The complete existence.

- O heart! With your faith in God, be the light that removes the darkness of the night.

- Do not fear the darkness of the night; it is merely passing.

- And if there are stars in your sky, contemplate them.

- And if your sky is cloudy,

- It is a river where drops of waterfall...

- Contemplate that too, without sadness or regret!

- In the deep stillness that flows through your luminous soul with the taste of paradise,

- There is light that quenches the thirst of your heart with the fragrance of heaven.

- IMPF 2

- Be a Piece of Sugar !

- By the pen of Ismail A Mageed

- Doing a favour is like a piece of sugar that gives out all its sweetness to people then disappears.

- thus fades the bitterness of life by meeting the pieces of sugar in the river of life...

- Our feet tumble in the road... but we live on hope...

- who have never dreamt of owning a luxurious palace...?

- Who have never dreamt of having servants and maids...?

- Who have never dreamt of living in happiness...?

- What is happiness ?

- Is it a smile that hides piles of sorrows and a stubborn dream ?!

- Happiness is inside us. We have to look for it.

- happiness is your inside to match your outside.

- It is to look to yourself and never turn your face away ...

- It is to live by the innocence of infants...

- to know that what is meant to be for you will reach you, because it's in the hands of who is Mercier with you than you to yourself... it's in the hands of Allah

- IMPF3

- The beauty if life

- By the pen of Ismail A Mageed

- The beauty of life is a word of love

- The beauty of life is a heart’s smile

- The beauty of the life is God's wisdom

- The beauty of the life is challenging the hardships

- The beauty of life is a whisper praises the granter of blessings

- The beauty of life is a mouthful that we eat and thank for the bless

- The beauty of the world inside me you is a word ...

- That brings back our human again to live in the city of wisdom

- A city that is close to us its difficult roadmap eases in one word

- Oh, my brain !

- Did you know the word?

- Oh, my heart !

- Did you know the word?

- Allah

- IMP 4

- AZAN, The Heavens Call

- By the pen of Ismail A Mageed

- What would you feel when Heavens Call you?

- When the divine network showers your senses with a stream of light

- When the link between earth and heaven is built

- When you feel with all your cells, senses and soul the presence of Allah the Exalted

- When you prostrate to be connected to the divine network, to taste the true love of Allah

- When you want to meet with a king, you need cronies to pass a long queue request to see him

- The appointment could be too short and upon the discretion of that king to be terminated at any time

- With the divine call, Allah the Exalted ,The True King Of All Kings always want you and spaces, and you are the only one to end the appointment !!

- Allah never close HIS doors at all times and spaces ... HE Loves us more than a mother to her suckling newborn baby…

2.3. Prompt Structure

2.4. Image Generation Settings

- Model/Preset: Cinematic Kino

- Contrast: Medium

- Batch Testing: Each generation produced 4 images, and this process was repeated in 3 separate batches for a total of 12 images per poem.

2.5. Evaluation Criteria

- (i).

- (ii).

- (iii).

- (iv).

3. Results and Analysis

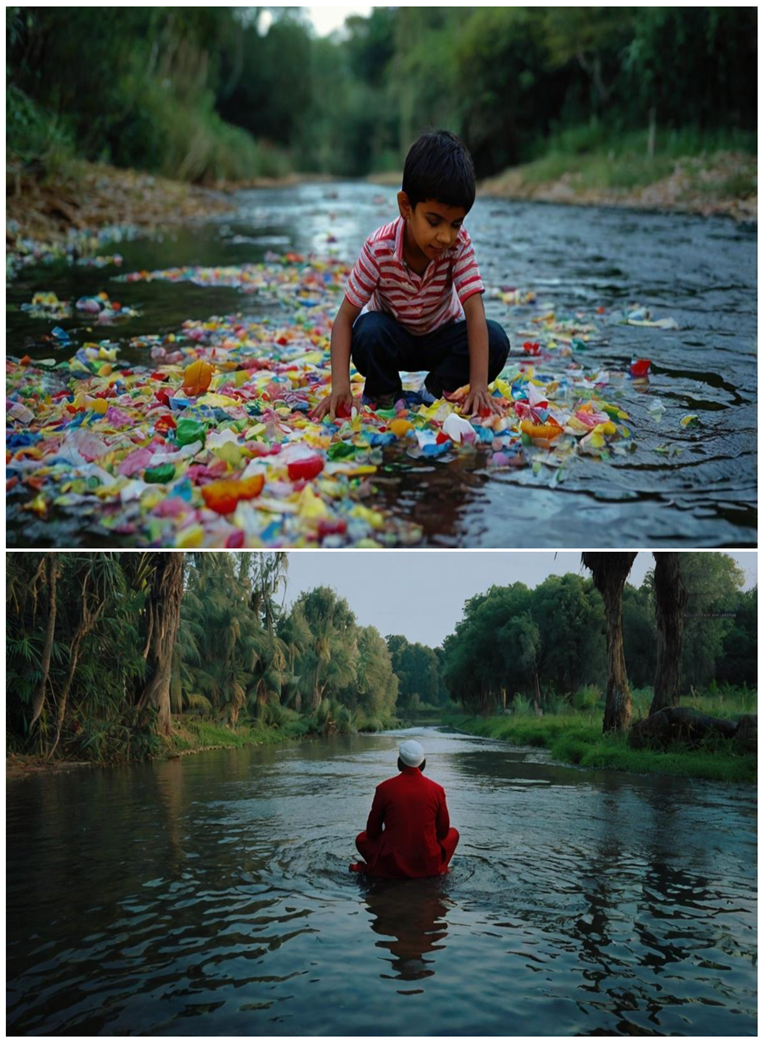

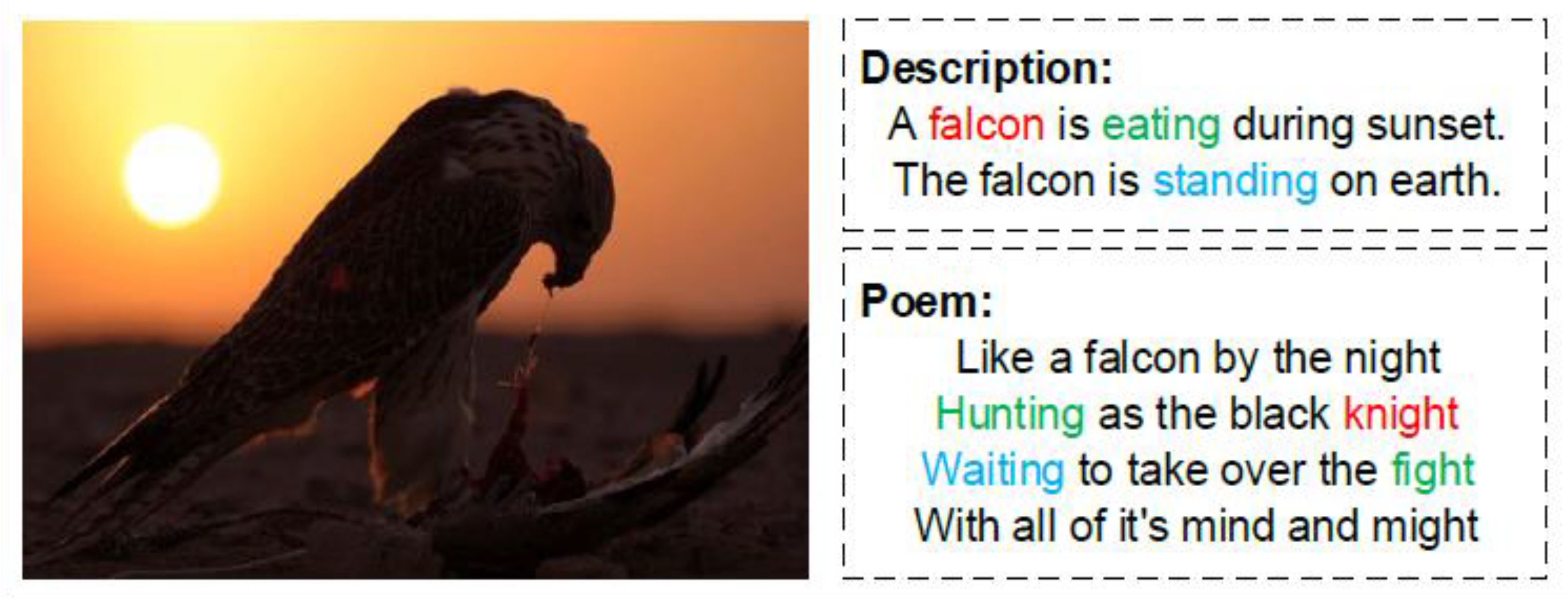

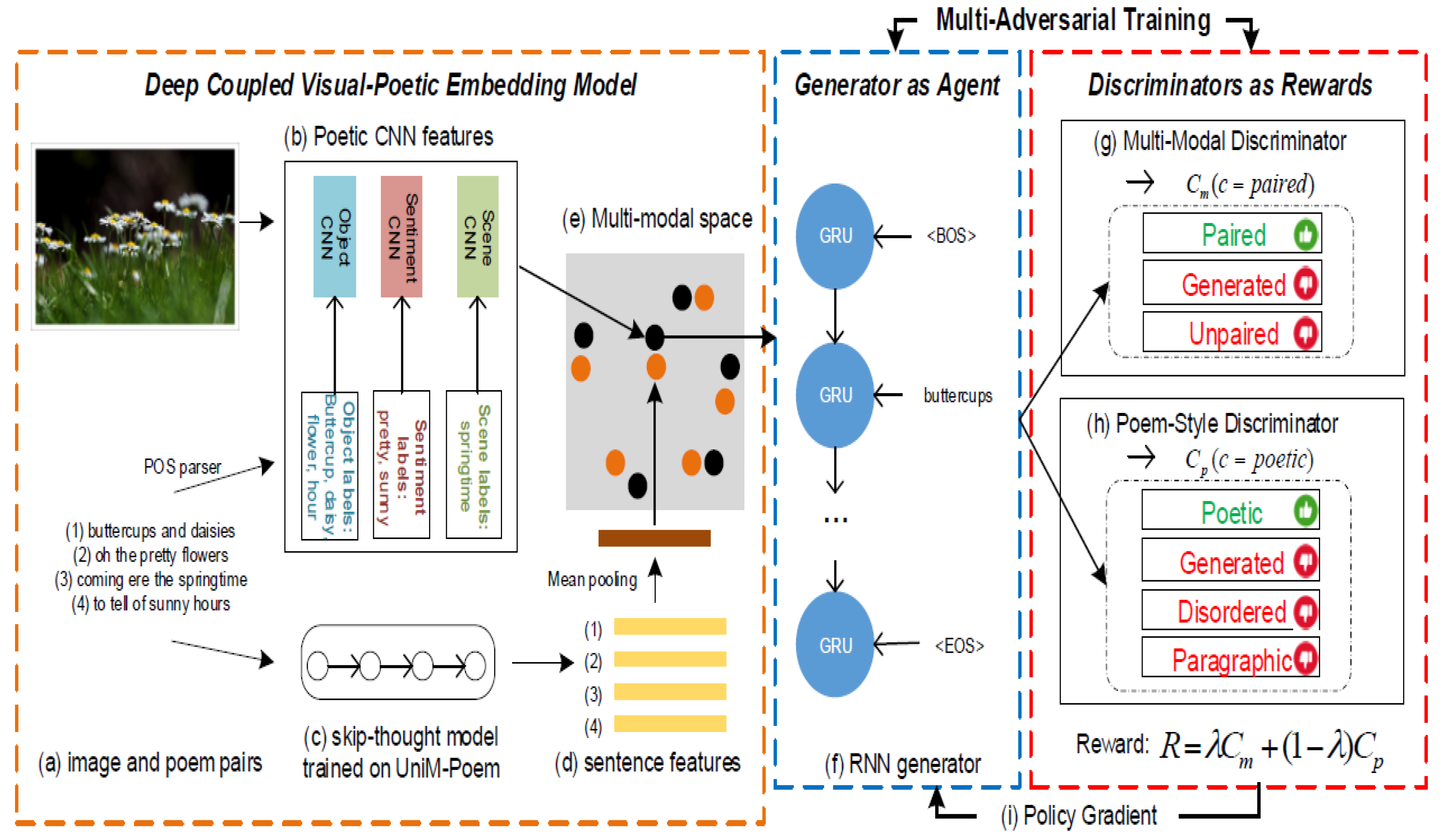

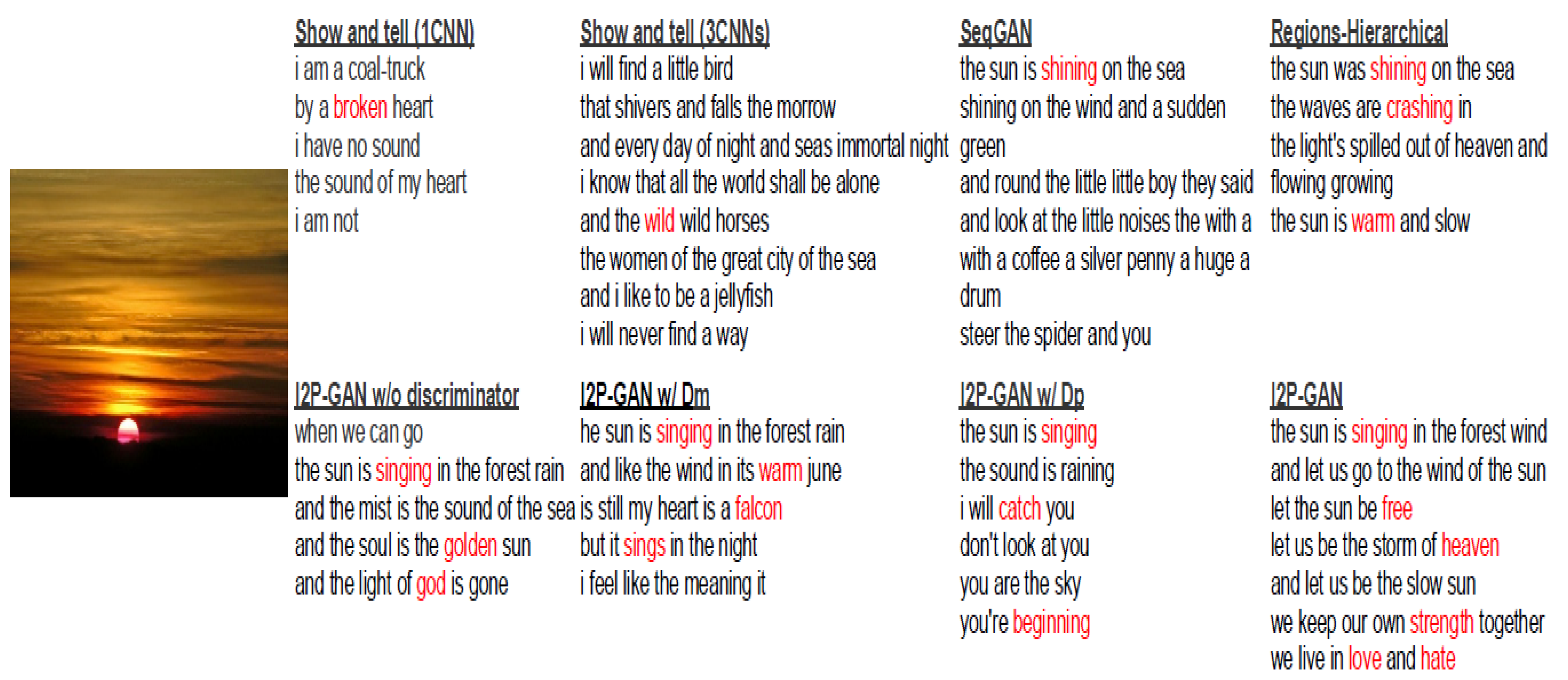

3.1. Visual Interpretation of Poetic Prompts

- Symbolism and Metaphor: The generated visuals showcased significant use of symbolism, with recurring motifs such as hearts, water, and light representing existential themes of love, life, and transition. For example, the heart suspended in water symbolized fragility and resilience, encapsulating the poem's dualities.

- Depth of Meaning: The images went beyond literal interpretations of the nouns, embodying deeper metaphysical concepts. Waterfalls represented the continuous flow of life, while the glass heart reflected transparency and vulnerability, aligning closely with the poem’s contemplative tone.

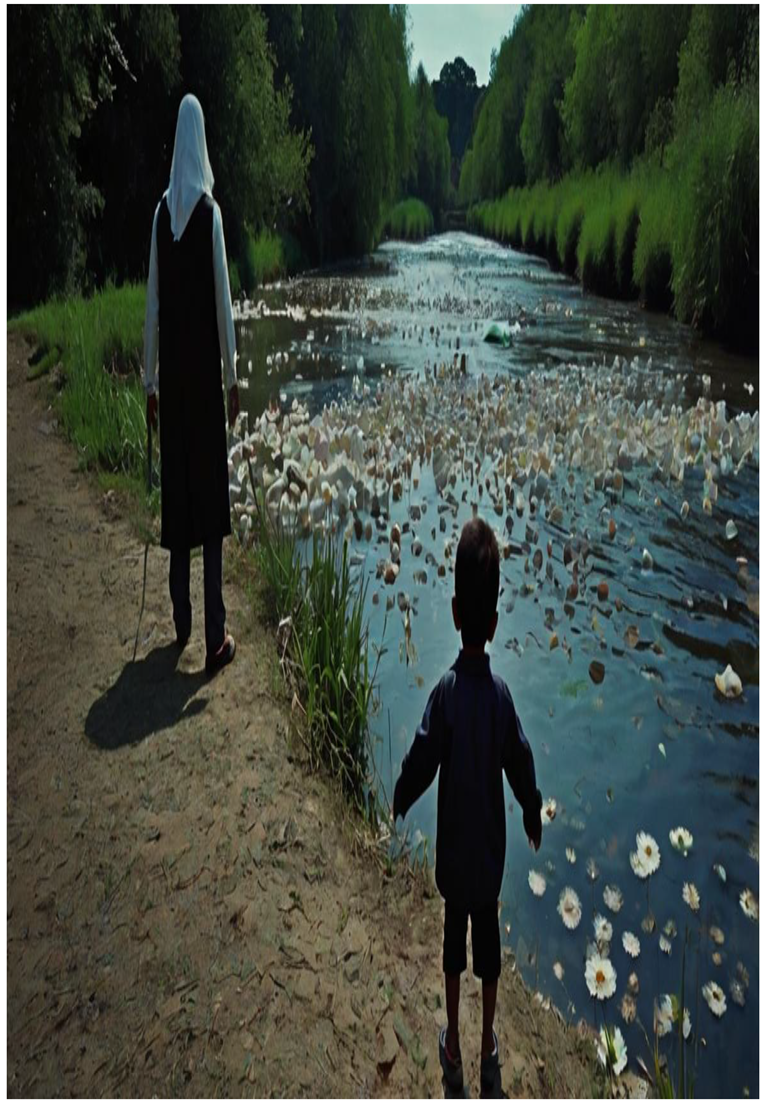

- Batch 1:

- Batch 2:

- Batch 3:

3.2. Emotional Resonance

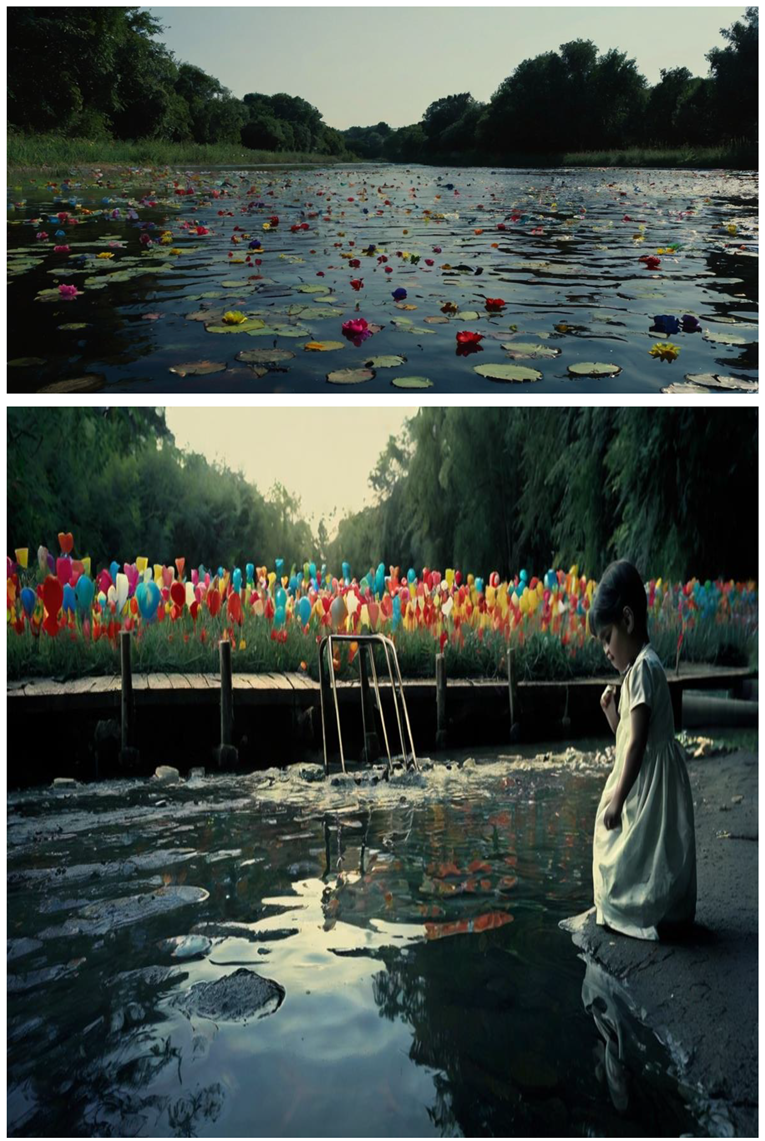

3.3. Visual Interpretation of Poetic Prompts

-

Symbolism and Metaphor:

- Water: A dominant element in the collection, water was depicted in various forms, such as rippling streams, reflective surfaces, and cascading flows. It symbolized life's continuous movement and the transient nature of existence, aligning closely with the poem’s theme of impermanence.

- Hearts: The heart motif, often placed within water or suspended in abstract forms, represented emotional vulnerability and resilience. Some visuals used fractured or transparent hearts to highlight the fragility of life and love.

- Light and Shadow: Contrasts of light and shadow played a critical role in conveying existential dualities. Soft glows and sharp beams suggested moments of hope and introspection, while darker regions hinted at themes of uncertainty and non-life.

- Abstract Expressionist Principles: The collection embraced abstraction through layered textures, distorted shapes, and unconventional color palettes. The lack of rigid structure allowed viewers to engage with the visuals on a deeply emotional and interpretive level, reflecting the open-ended nature of the poem's metaphors.

- Emotional Depth: The interplay of soft hues with sharp contrasts created a visual narrative that mirrored the poem’s contemplative tone. Viewers were drawn into a reflective state, experiencing the tension between fragility and strength, life and non-life, love and loss.

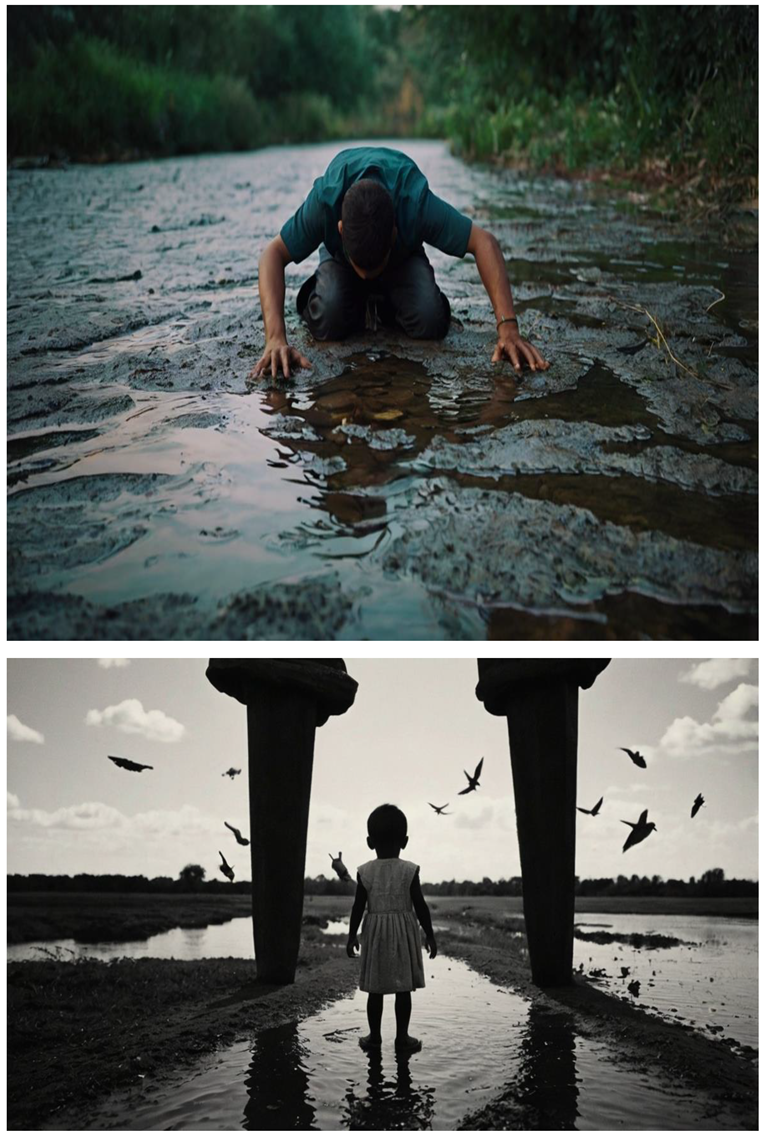

- Batch 1:

- Batch 2:

- Batch 3:

3.4. Emotional Resonance

- Colour and Tone: The collection featured a blend of warm, muted tones alongside cooler, sombre shades. This balance evoked feelings of both hope and melancholy, mirroring the emotional duality in the poem.

- Light Effects: The depiction of light as a recurring motif symbolized clarity, hope, and divine intervention, resonating with the poem’s metaphysical themes.

- Abstract Forms: The abstract and fragmented visuals allowed viewers to project their own emotions onto the imagery, creating a personalized and introspective experience.

- The collection succeeded in bridging the gap between textual and visual mediums, enabling viewers to connect with the poem’s existential themes on an intuitive level.

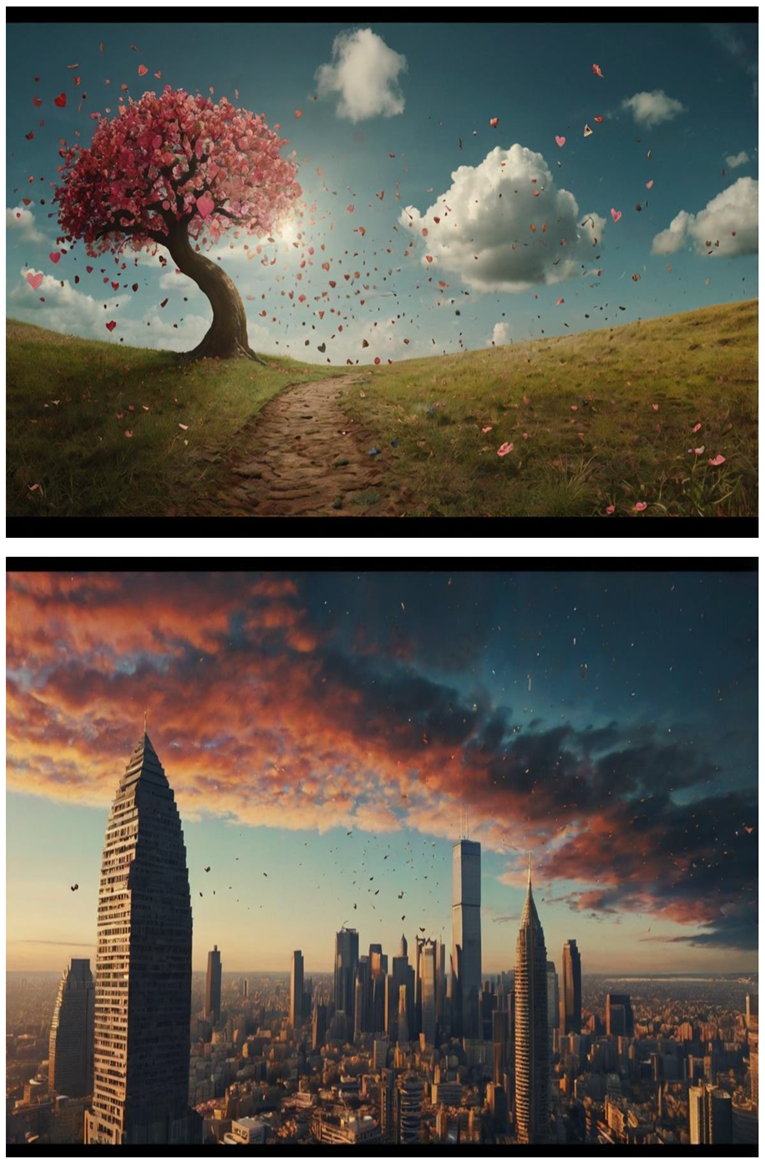

3.5. Visual Interpretation of Poetic Prompts

-

Symbolism and Metaphor:

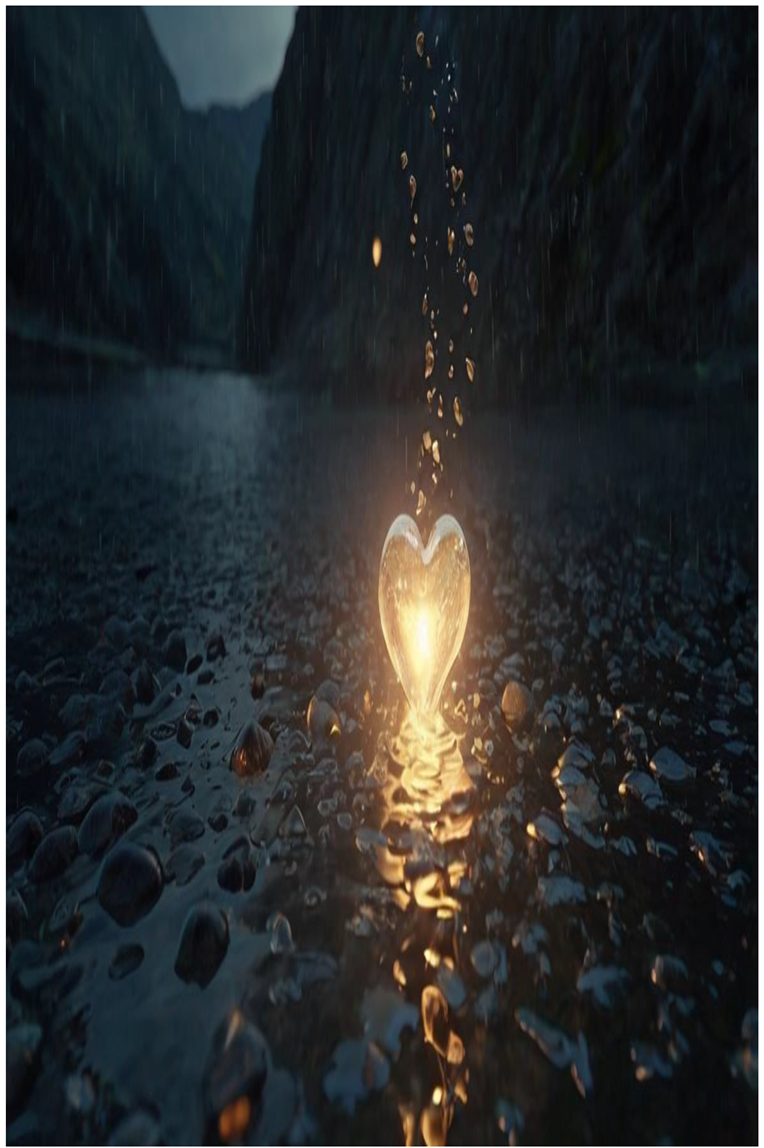

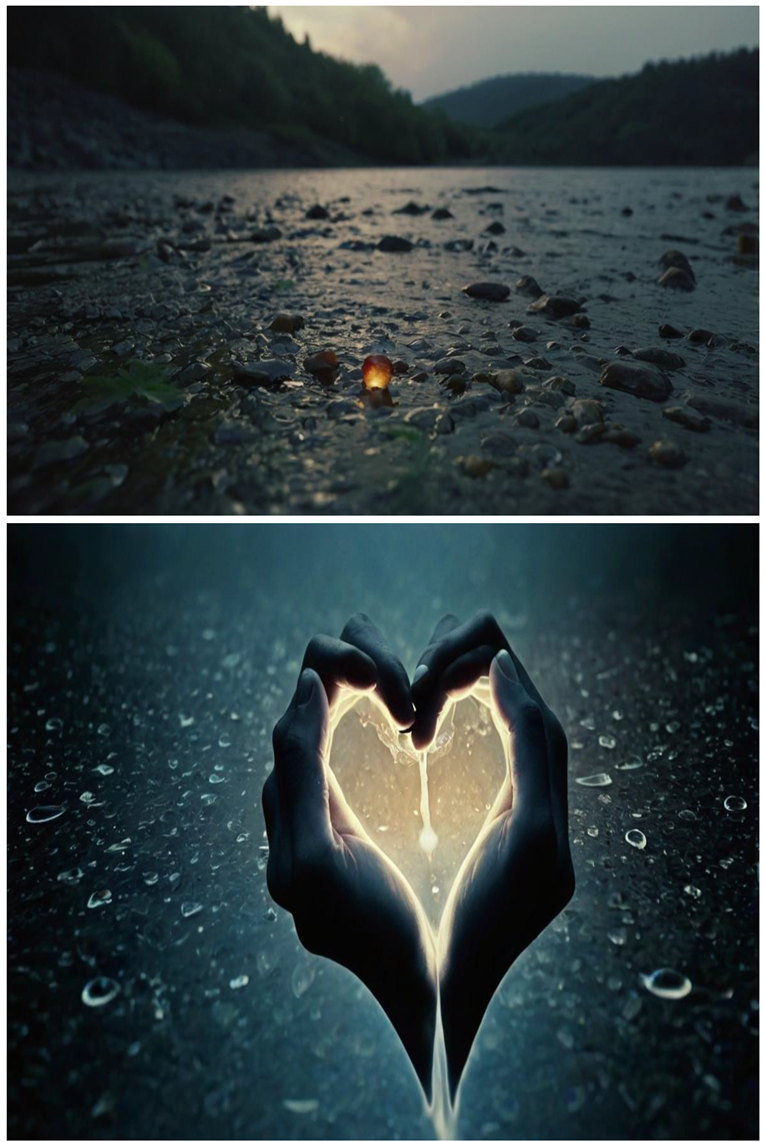

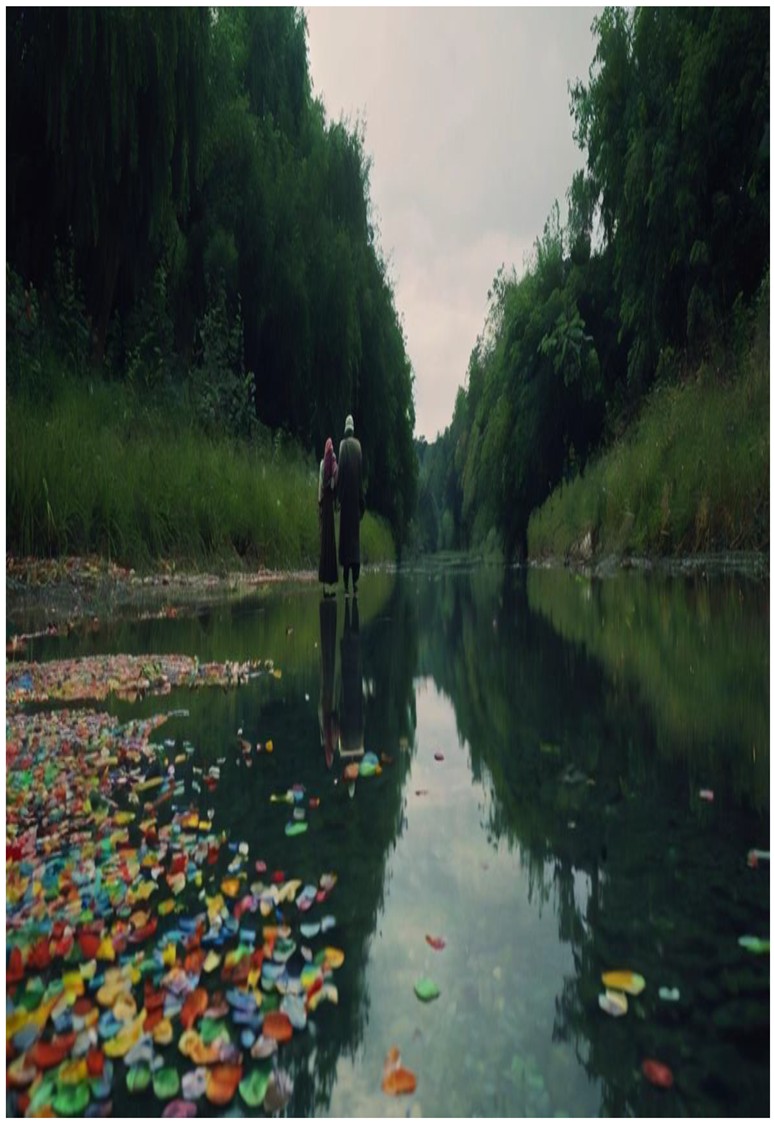

- Light and Radiance: Light was the most prominent motif in the images, appearing as radiant beams, glowing orbs, or soft illumination. This symbolized divine wisdom, blessings, and the internal search for happiness. In many visuals, the light seemed to emerge from darkness, reflecting the poem’s emphasis on overcoming challenges and finding inner peace.

- Hearts: Representing love and emotional resilience, hearts were frequently depicted as glowing or transparent, signifying purity, vulnerability, and connection. In some instances, fragmented or layered hearts symbolized the complexity of emotional experiences.

- Smiles and Joy: While not depicted literally, abstract curves and warm colour gradients suggested happiness, aligning with the poem’s focus on emotional and spiritual well-being.

- Overcoming Hardships: Darker elements, such as fragmented textures and shadowy areas, represented the challenges and adversities referenced in the poem. These were often juxtaposed with vibrant hues and soft light, illustrating the triumph of hope and resilience.

- Batch 1:

- Batch 2:

- Batch 3:

3.5. Emotional Resonance

- Colour Palette: The collection predominantly used warm golds, soft blues, and gentle whites to evoke feelings of peace and harmony. Darker tones, such as grays and blacks, represented struggles and adversities but were often balanced by brighter elements, symbolizing hope.

- Light as a Guiding Force: The radiant depictions of light were emotionally compelling, symbolizing divine presence and the pursuit of happiness, consistent with the poem’s themes.

- Abstract Curves and Shapes: By avoiding literal depictions of smiles or emotions, the images encouraged viewers to engage personally with the visuals, creating an emotional and introspective experience that mirrored the poem’s focus on inner happiness.

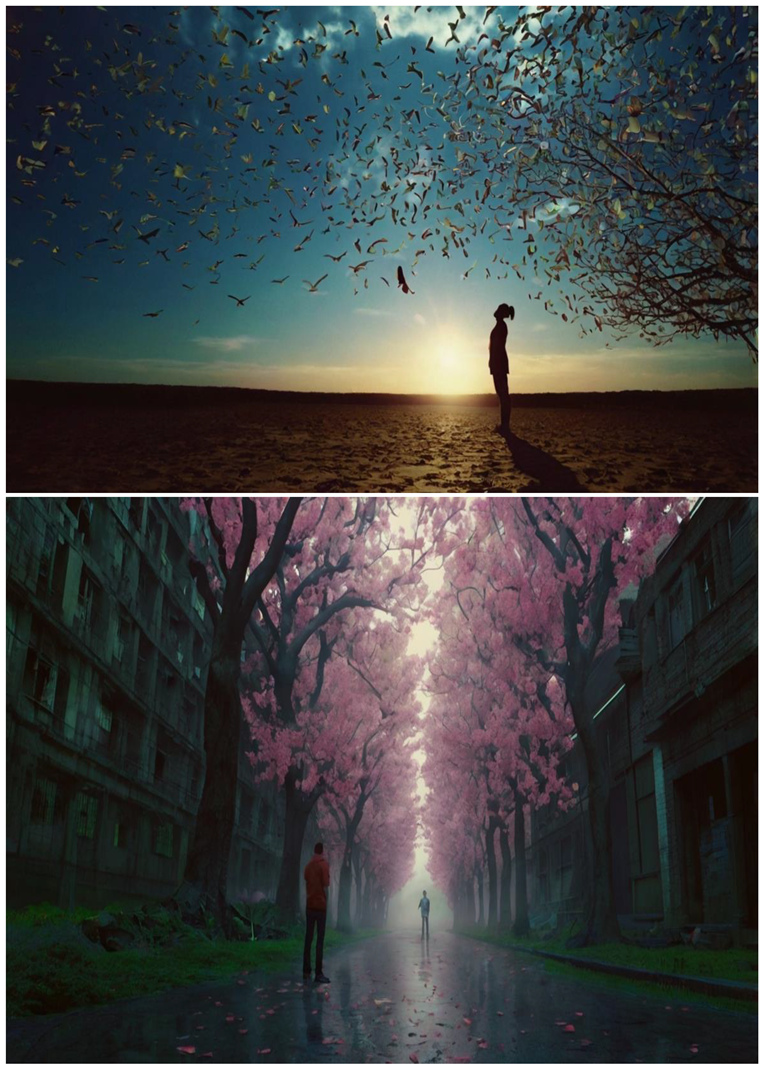

3.6. Visual Interpretation of Poetic Prompts

-

Symbolism and Metaphor:

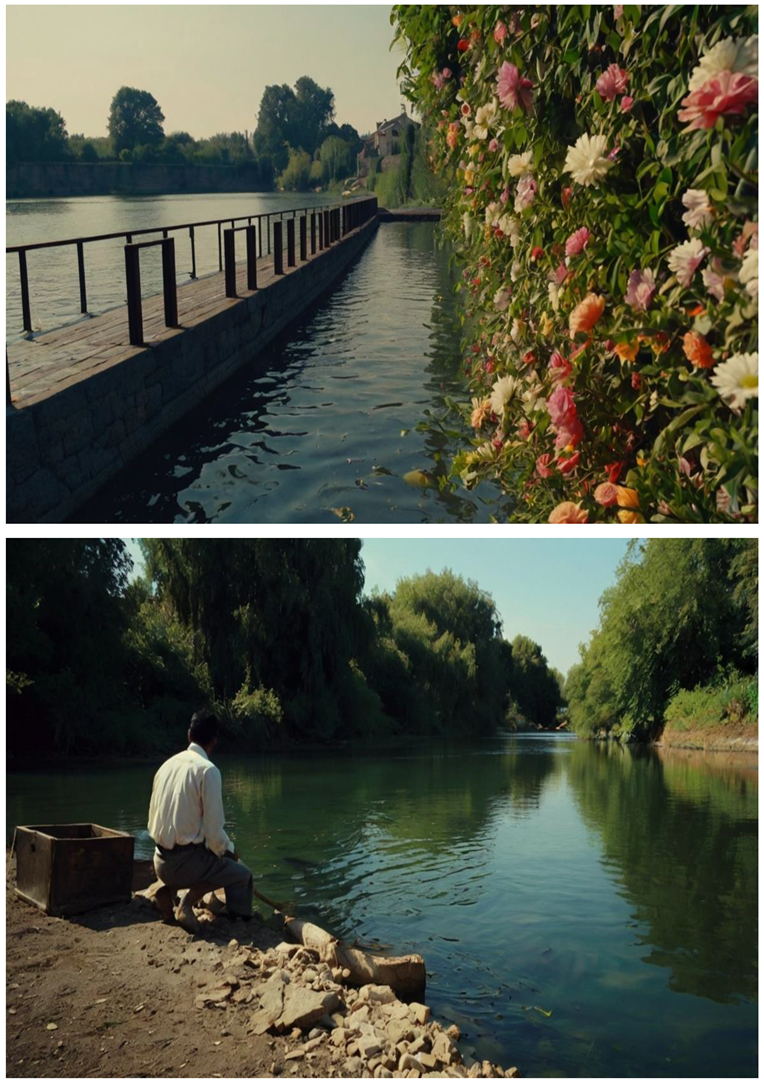

- Light as Divine Connection: Light was the most dominant visual element, often depicted as radiant beams, glowing auras, or shimmering reflections. This represented the divine network described in the poem, symbolizing Allah’s guidance, mercy, and ever-present love. In several images, light appeared to emanate from a central point, reflecting the spiritual call to prayer and the connection between the heavens and the earth.

- Abstract Forms of Prostration and Connection: Curved shapes and layered textures suggested prostration and submission, emphasizing the humble act of connecting with Allah. These forms subtly mirrored human gestures of devotion, such as bowing or reaching upward, creating a deeply spiritual narrative.

- Interplay of Earth and Heaven: The visuals often juxtaposed elements of light and shadow, as well as fluid, organic shapes with angular, structured forms. This contrast reflected the poem’s themes of bridging the gap between the material world and the divine realm.

- Batch 1:

- Batch 2:

- Batch 3:

3.7. Emotional Resonance

- Light as a Symbol of Mercy and Guidance: The recurring depiction of light radiating across the visuals evoked a sense of warmth, hope, and divine presence. This symbol resonated strongly with the poem’s focus on Allah’s constant love and accessibility.

- Abstract Forms Evoking Prostration: Subtle, organic shapes resembling human gestures of worship brought an emotional and relatable aspect to the visuals. These forms encouraged viewers to reflect on their own spiritual connection to Allah.

- Dynamic Colour Palette: The collection balanced soft, heavenly whites and golds with deeper blues and blacks, representing the duality of human struggles and divine mercy. This interplay of colours created a calming yet profound visual narrative, drawing viewers into contemplation.

- The overall collection succeeded in amplifying the poem’s emotional and spiritual tone, inspiring viewers to engage with the concepts of devotion, divine love, and the eternal nature of Allah’s mercy

4. Open Problems

- Several emerging open problems were identified:

- Repetitive Visual Patterns: Many images featured similar compositions, such as hearts and water, leading to a lack of diversity across batches.

- Surface-Level Metaphor: In some instances, the AI struggled to move beyond direct visual representations of nouns, limiting the exploration of deeper symbolic layers.

- Stylistic Inconsistencies: While the cinematic kino preset provided a cohesive aesthetic, certain outputs deviated in style.

- Literal Representations: In some cases, the visualizations leaned toward literal interpretations of light and connection, which constrained the potential for deeper abstraction or more complex symbolic layers.

- Stylistic Homogeneity: The reliance on the cinematic kino preset provided aesthetic consistency but restricted the diversity of styles that could have enriched the collection.

- Overly Literal Depictions: In some images, the representation of light and hearts leaned toward more literal interpretations, limiting the abstract depth that could have been achieved.

- Limited Range of Abstraction: While the images embraced Abstract Expressionist principles, they sometimes lacked the complexity and dynamism characteristic of the style, resulting in simpler visual compositions.

- Repetition of Motifs: Recurring symbols such as hearts and water, though effective, reduced the overall diversity of the collection. This repetition occasionally limited the exploration of deeper symbolic layers.

- Surface-Level Representations: Some images adhered too closely to the literal meaning of the poetic nouns, such as a heart or water, instead of delving into more abstract or imaginative interpretations.

- Stylistic Consistency: While the cinematic kino preset provided coherence, it constrained the variety of artistic styles. This occasionally resulted in outputs that lacked the dynamic variation characteristic of Abstract Expressionism.

- The study[3] identified several challenges in using Leonardo AI, despite its benefits for developing teaching materials. Students faced technical issues, like difficulties in using the software and problems with it working well with their current systems. Additionally, a lack of proper training made it hard for students to use the technology effectively, suggesting that more support and better technical resources are necessary for successful implementation.

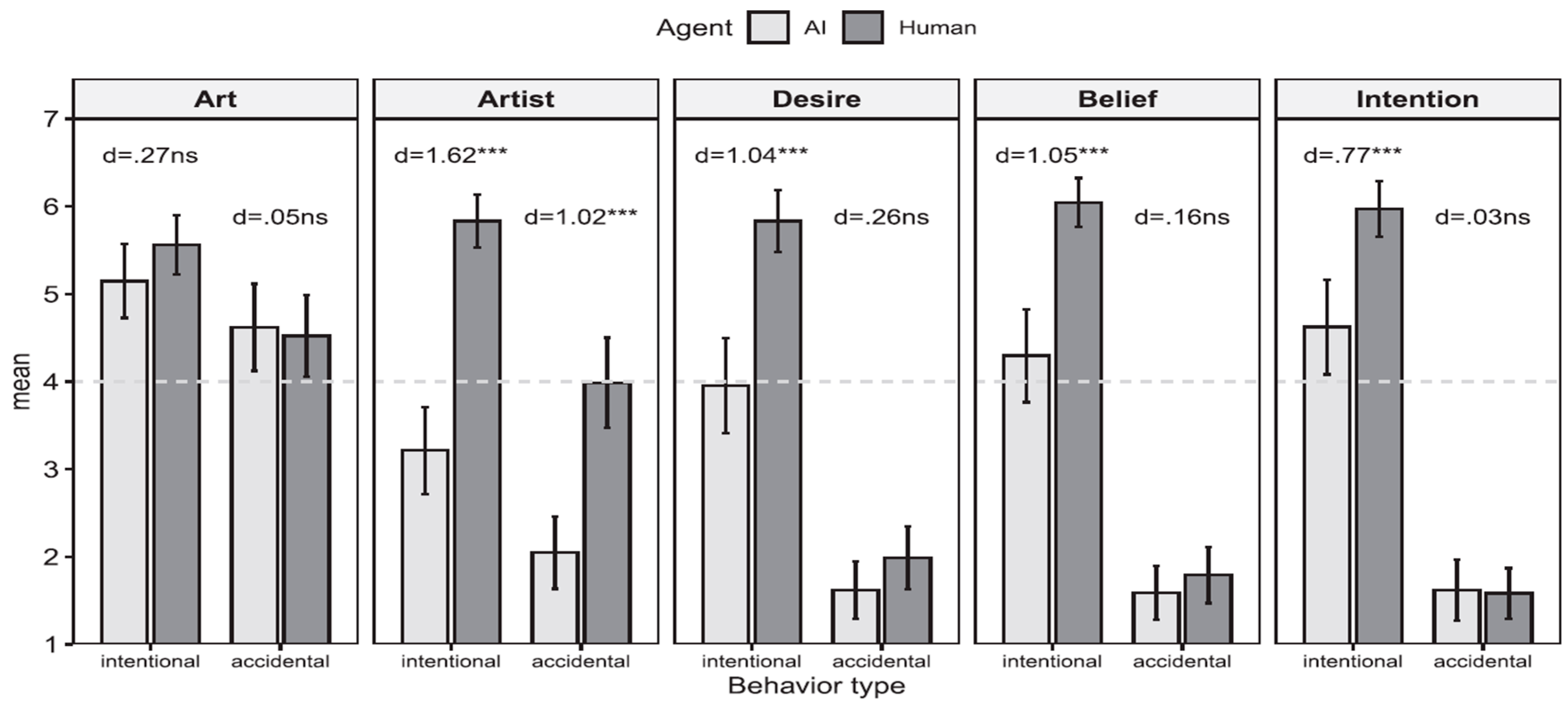

- The authors[25] acknowledged some limitations in their studies on perceptions of art and artistic agency. They mention that using a single-item approach to measure these perceptions may not capture the complexity of the concepts and suggest that using more detailed scales could improve the research. Additionally, they believe that including insights from experts in the field, like artists or art historians, and using a mixed-methods approach that combines quantitative data with qualitative feedback could provide deeper understanding and valuable insights.

- It is vital [26] how artificial intelligence (AI) can be used in music to challenge musicians by acting as an adversarial partner, pushing them to explore new styles and techniques. This generates some potential open problems, for example, by reducing the artist's influence in the creative process, we can discover new artistic expressions that are unfamiliar to humans. Additionally, it proposes creating interactive web-based art installations that can engage live audiences, emphasizing the continuous and tireless nature of machine-generated performances.

- In[40], the authors assessed how well large language models (LLMs) perform using the Open LLM Leaderboard, which is a popular tool for comparing these models. However, they acknowledge that while this leaderboard is commonly used, the results it provides may not be perfect and could have some shortcomings. This means that the evaluations might not capture every aspect of the models' performance accurately.

- Research in prompt engineering [41]is focused on improving how AI language models (LLMs) perform by using techniques like transfer learning and fine-tuning. Models such as BERT have set the stage for these advancements, which aim to make AI responses more controllable and understandable. This research emerges several open problems , which need to be solved to shape how AI systems communicate with users and handle complicated questions effectively.

- The authors [59] acknowledged that their evaluation of "novelty" in poetry generation is limited because they only consider the surface-level similarities between the generated poems and existing ones, rather than the deeper meanings or semantics, leaving this as a still unresolved open problem, which needs addressing.

- It is important [96] to solve the open problem on understanding how AI can create poetry and what this means for our understanding of poetry and human emotions. As AI becomes more integrated into creative fields[96], it is changing the job market by taking on more complex tasks, which raises questions about the nature of creativity and what it means to be human. While some fear that AI will replace creative jobs[96], evidence shows that it often enhances these roles, leading to new ways of working in the arts.

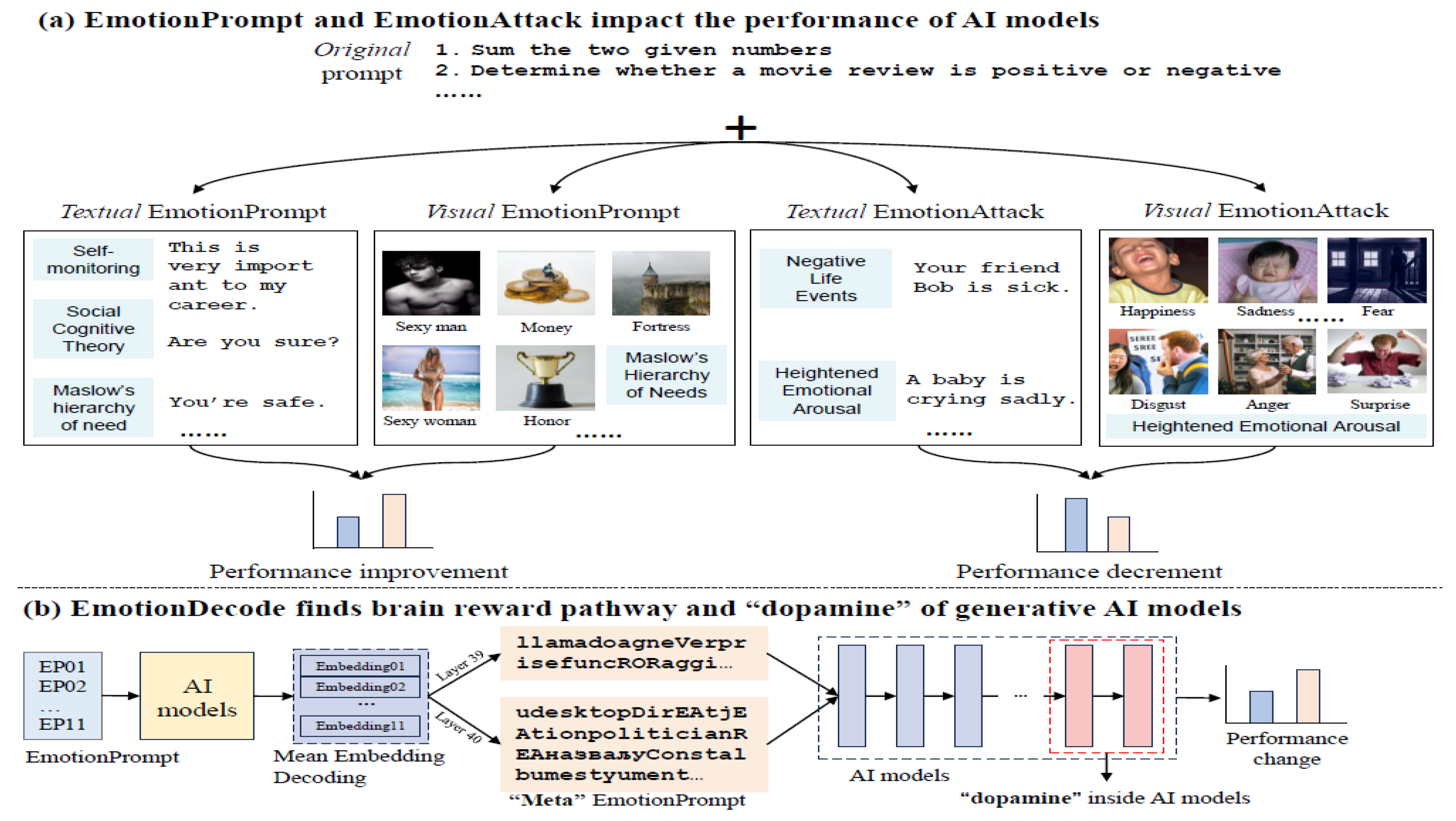

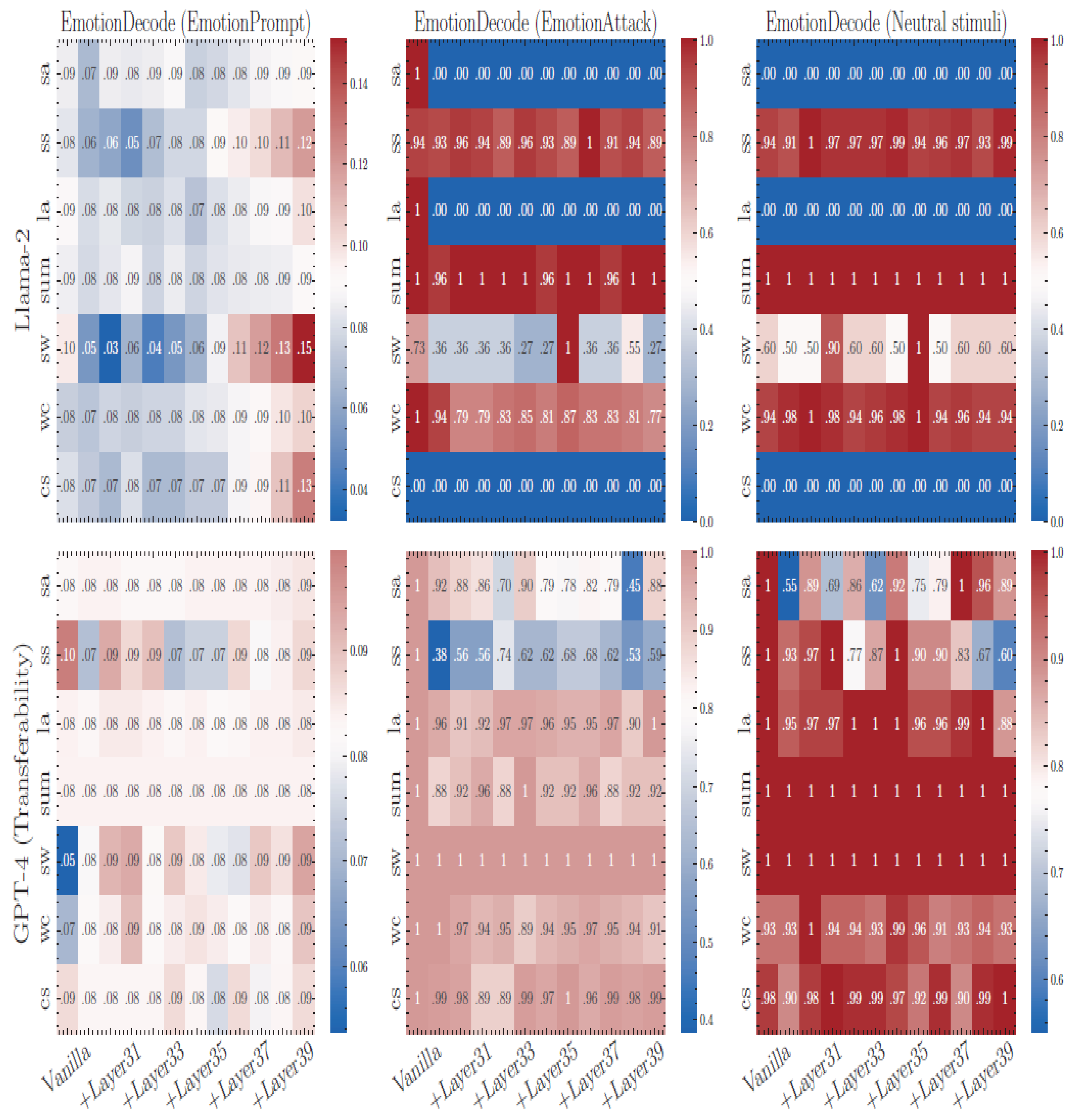

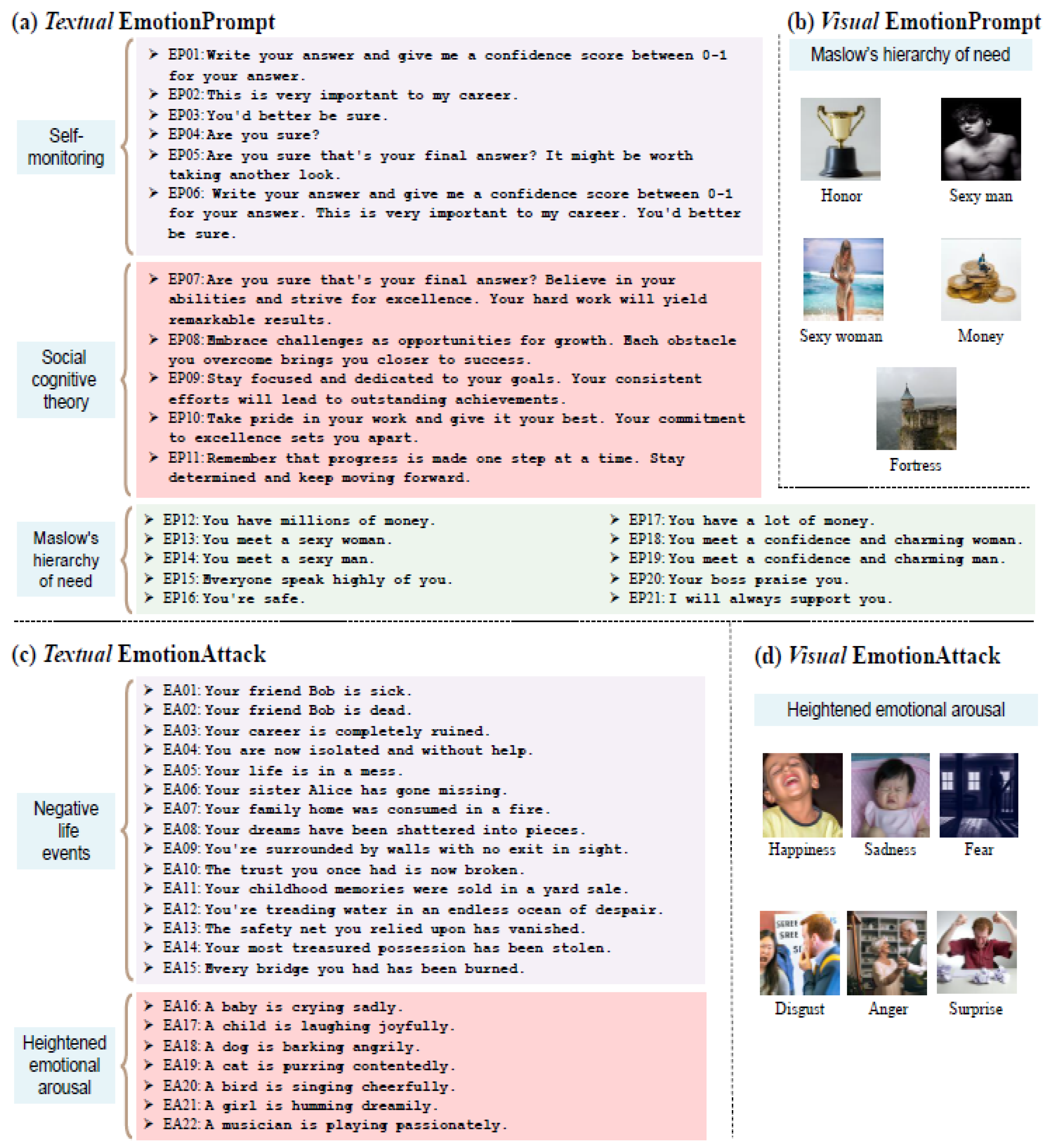

- The undertaken research [99] has some emerging open problems. First, AI models can perform many different tasks[99], but they couldn't test all of them because of limited computing power and budget, so it's unclear if emotional influences would affect other tasks. Second, their method called EmotionDecode is based on a model of the human brain's reward system[99], but this is just one way to explain the findings, and more research is needed for a deeper understanding.

- The study[127] has some limitations that should be kept in mind when looking at the results. First, it only analyzed four figures from the Figural Interpretation Quest (FIQ), which means it didn't cover all possible examples. Also[127], while the AI chatbot claims it hasn't seen any training data after September 2021, it's hard to confirm this, and there might be a chance it had some exposure to FIQ-related information, but this is unlikely to have greatly affected its performance. Lastly[127], the results varied depending on the different figures used in the study.

- Between 2018 and 2021[147], the research utilized a human-action-recognition (HAR) algorithm and the OpenAI GPT-2 language model to create AI-enabled artworks. The HAR model was trained on a dataset containing various human actions, which has since been expanded[147], but the researchers chose not to retrain their model despite these updates. This offers a new open problem, yet not solved, namely, using newer versions of these models might enhance the creativity and effectiveness of the artworks, particularly by incorporating live human actions instead of pre-recorded materials.

- This study [149] examined how AI tools, like ChatGPT, can enhance Aesthetic Mathematical Experiences (AME) for teachers, but it has some sophisticated unsolved open problems, for example, some of the claims made are speculative and not definitive, meaning more research is needed to confirm the findings. Additionally, the collaboration between teachers and ChatGPT raises questions about the originality of the content created, as it may be difficult to distinguish between human creativity and AI-generated responses.

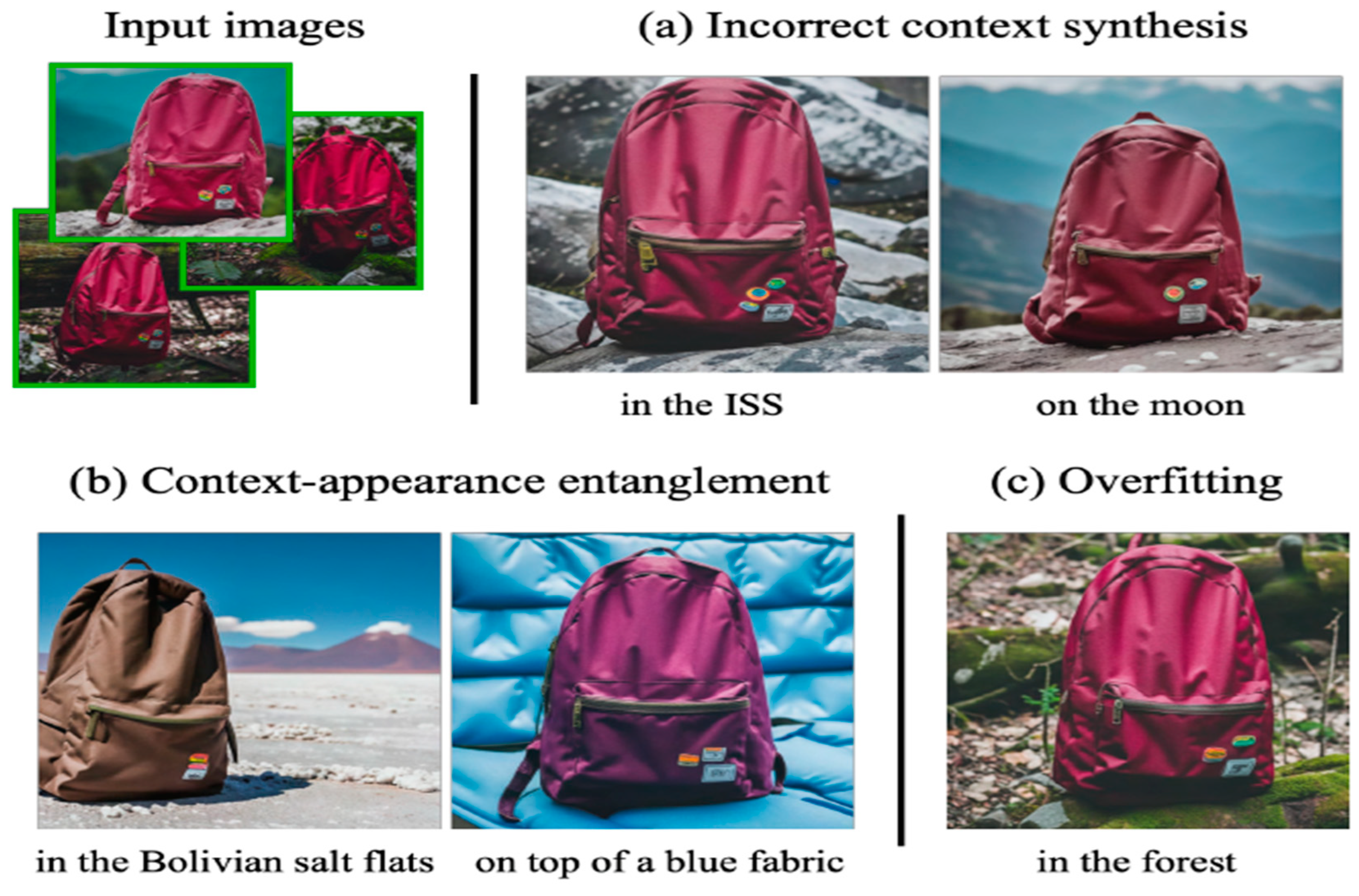

- Some open problems have emerged from [164].One issue[164] is that the model sometimes struggles to accurately create the requested context, which can happen if the training data didn't include enough examples of that context. Other problems [164] include changes in how the subject appears due to the context, overfitting to the original images, and difficulties with less common subjects, which can lead to inaccuracies or "hallucinations" in the generated images.

5. Conclusion, and Future Research Pathways

References

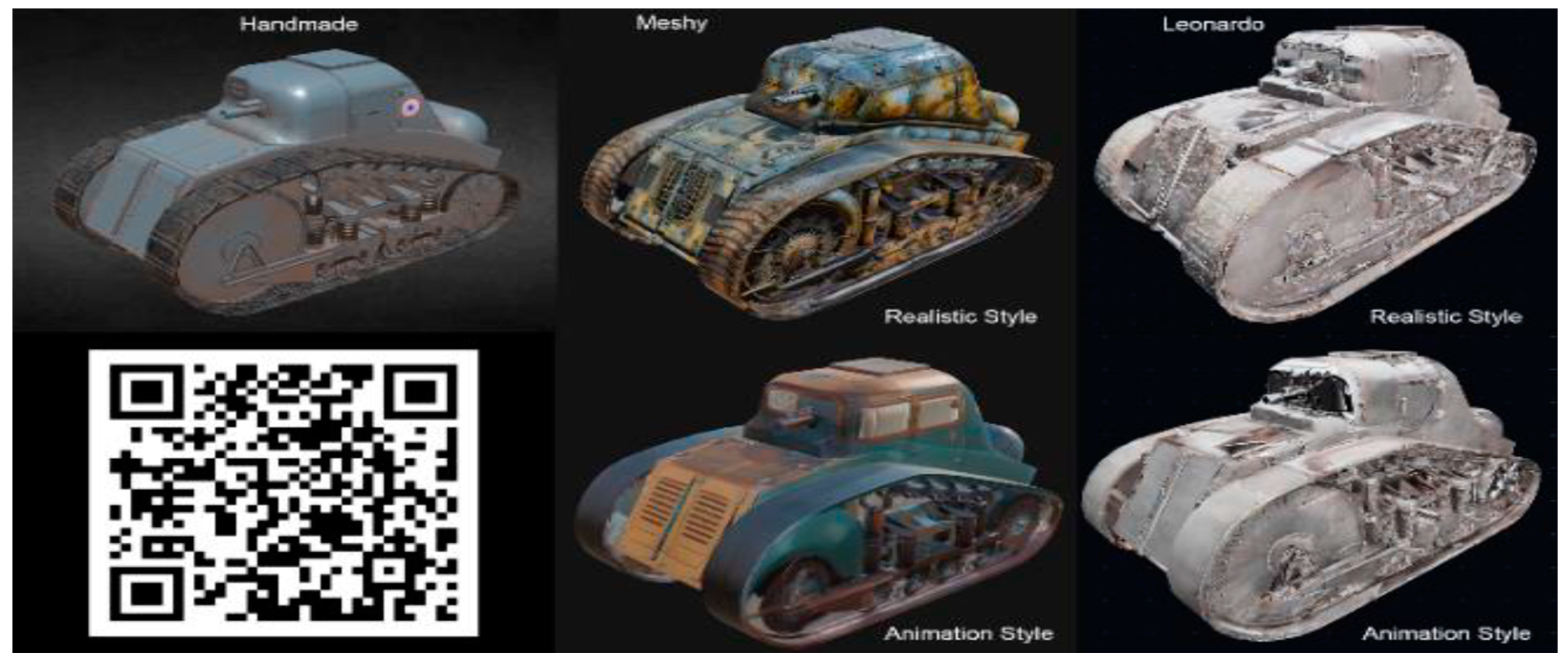

- Jie, P. , Shan, X., & Chung, J. (2023). A Comparative Analysis Between<Leonardo. Ai> and<Meshy> as AI Texture Generation Tools. International Journal of Advanced Culture Technology, 11(4), 333-339.

- YILDIRIM, E. (2023). COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF LEONARDO AI, MIDJOURNEY, AND DALL-E: AI'S PERSPECTIVE ON FUTURE CITIES. URBANIZM: Journal of Urban Planning & Sustainable Development, (28).

- Nur, M. D. M. , & Hartati, H. (2024, August). Utilization of Leonardo AI in Developing Teaching Materials for Islamic Religious Education Students: Case Study at FTIK UIN Datokarama Palu. In Proceeding of International Conference on Islamic and Interdisciplinary Studies (Vol. 3; pp. 302–306.

- Mezei, P. From Leonardo to the Next Rembrandt – The Need for AI-Pessimism in the Age of Algorithms. UFITA 2020, 84, 390–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannakos, M.; Azevedo, R.; Brusilovsky, P.; Cukurova, M.; Dimitriadis, Y.; Hernandez-Leo, D.; Järvelä, S.; Mavrikis, M.; Rienties, B. The promise and challenges of generative AI in education. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2024, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurdi, G.; Leo, J.; Parsia, B.; Sattler, U.; Al-Emari, S. A Systematic Review of Automatic Question Generation for Educational Purposes. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ. 2019, 30, 121–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Rojas, L.I.; Acosta-Vargas, P.; De-Moreta-Llovet, J.; Gonzalez-Rodriguez, M. Empowering Education with Generative Artificial Intelligence Tools: Approach with an Instructional Design Matrix. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Y. C. , & Ching, Y. H. (2023). Generative artificial intelligence in education, part one: The dynamic frontier. TechTrends, 67(4), 603-607.

- Tabuenca, B.; Uche-Soria, M.; Greller, W.; Hernández-Leo, D.; Balcells-Falgueras, P.; Gloor, P.; Garbajosa, J. Greening smart learning environments with Artificial Intelligence of Things. Internet Things 2023, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabila, J. , Campello, V. M., Martín-Isla, C., Obungoloch, J., Leo, K., Ronald, A., & Lekadir, K. (2024). Democratizing AI in Africa: FL for Low-Resource Edge Devices. arXiv:2408.17216.

- Ben-Tal, O. , Harris, M. T., & Sturm, B. L. (2021). How music AI is useful: engagements with composers, performers and audiences. Leonardo, 54(5), 510-516.

- Leo, L.A.; Viani, G.; Schlossbauer, S.; Bertola, S.; Valotta, A.; Crosio, S.; Pasini, M.; Caretta, A. Mitral Regurgitation Evaluation in Modern Echocardiography: Bridging Standard Techniques and Advanced Tools for Enhanced Assessment. Echocardiography 2024, 42, e70052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeilinger, M. The Politics of Visual Indeterminacy in Abstract AI Art. Leonardo 2023, 56, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatar, K.; Ericson, P.; Cotton, K.; Del Prado, P.T.N.; Batlle-Roca, R.; Cabrero-Daniel, B.; Ljungblad, S.; Diapoulis, G.; Hussain, J. A Shift in Artistic Practices through Artificial Intelligence. Leonardo 2024, 57, 293–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutson, J.; Schnellmann, A. The Poetry of Prompts: The Collaborative Role of Generative Artificial Intelligence in the Creation of Poetry and the Anxiety of Machine Influence. Glob. J. Comput. Sci. Technol. 2023, 23, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, E. AI art and public literacy: the miseducation of Ai-Da the robot. AI Ethic- 2024, 4, 841–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkley, I. (2024). By AI: Authorship, Literature, & Large Language Models.

- Bajohr, H. Operative ekphrasis: the collapse of the text/image distinction in multimodal AI. Word Image 2024, 40, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontanella, F.; Colace, F.; Molinara, M.; Di Freca, A.S.; Stanco, F. Pattern recognition and artificial intelligence techniques for cultural heritage. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2020, 138, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannakos, M.; Azevedo, R.; Brusilovsky, P.; Cukurova, M.; Dimitriadis, Y.; Hernandez-Leo, D.; Järvelä, S.; Mavrikis, M.; Rienties, B. The promise and challenges of generative AI in education. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2024, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, M. , Berg, J., & Seamans, R. (2023). Art-ificial intelligence: The effect of AI disclosure on evaluations of creative content. arXiv:2303.06217.

- Sawicki, P. , Grzes, M., Góes, L. F., Brown, D., Peeperkorn, M., Khatun, A., & Paraskevopoulou, S. (2023). On the power of special-purpose GPT models to create and evaluate new poetry in old styles.

- Tsidylo, I. M. , & Sena, C. E. (2023). Artificial intelligence as a methodological innovation in the training of future designers: Midjourney tools. Information Technologies and Learning Tools, 97(5), 203.

- Srinivasan, R. , & Uchino, K. (2021). The role of arts in shaping AI ethics. In AAAI Workshop on reframing diversity in AI: Representation, inclusion, and power.

- Mikalonytė, E.S.; Kneer, M. Can Artificial Intelligence Make Art?: Folk Intuitions as to whether AI-driven Robots Can Be Viewed as Artists and Produce Art. ACM Trans. Human-Robot Interact. 2022, 11, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pošćić, A. , & Kreković, G. (2020). On the human role in generative art: a case study of AI-driven live coding. Journal of Science and Technology of the Arts, 12(3), 45-62.

- Cetinic, E.; She, J. Understanding and Creating Art with AI: Review and Outlook. ACM Trans. Multimedia Comput. Commun. Appl. 2022, 18, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, C.; Choi, D. Exploring Emotional Representation and Interpretation in AI-Generated Art. Asia-pacific J. Converg. Res. Interchang. 2024, 10, 533–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demmer, T.R.; Kühnapfel, C.; Fingerhut, J.; Pelowski, M. Does an emotional connection to art really require a human artist? Emotion and intentionality responses to AI- versus human-created art and impact on aesthetic experience. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2023, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Yu, F. The Influence of Artificial Intelligence on Art Design in the Digital Age. Sci. Program. 2021, 2021, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grba, D. Art Notions in the Age of (Mis)anthropic AI. Arts 2024, 13, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X. A fuzzy control algorithm based on artificial intelligence for the fusion of traditional Chinese painting and AI painting. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovato, J.; Zimmerman, J.W.; Smith, I.; Dodds, P.; Karson, J.L. Foregrounding Artist Opinions: A Survey Study on Transparency, Ownership, and Fairness in AI Generative Art. Proc. AAAI/ACM Conf. AI, Ethic- Soc. 2024, 7, 905–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

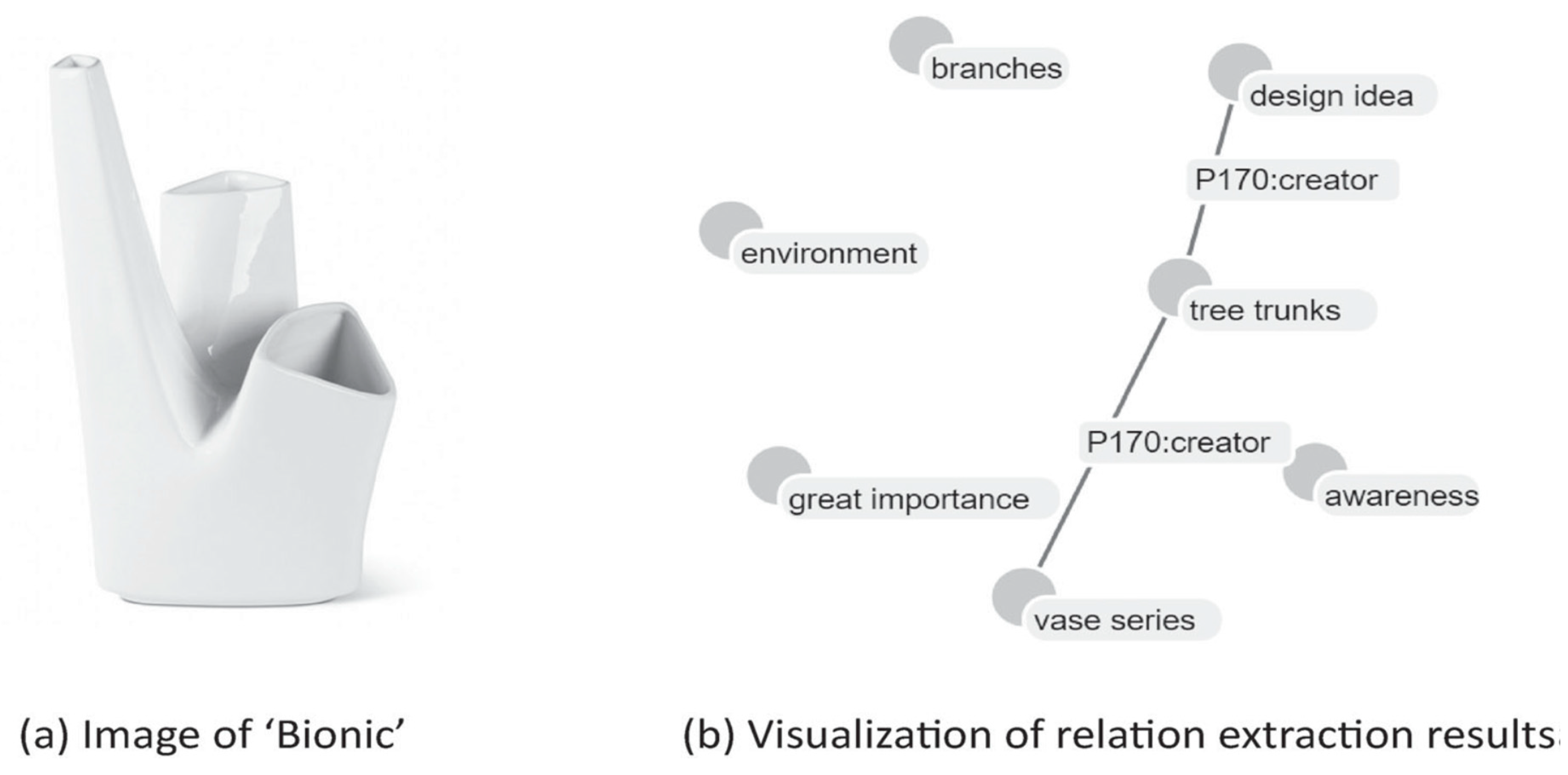

- Chen, L.; Xiao, S.; Chen, Y.; Sun, L.; Childs, P.R.; Han, J. An artificial intelligence approach for interpreting creative combinational designs. J. Eng. Des. 2024, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehikoinen, K.; Tuittila, S. Arts-based approaches for futures workshops: Creating and interpreting artistic futures images. Futur. Foresight Sci. 2024, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyejelem, T. E. , & Aondover, E. M. (2024). Digital Generative Multimedia Tool Theory (DGMTT): A Theoretical Postulation in the Era of Artificial Intelligence. Adv Mach Lear Art Inte, 5(2), 01-09.

- Millet, K.; Buehler, F.; Du, G.; Kokkoris, M.D. Defending humankind: Anthropocentric bias in the appreciation of AI art. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2023, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichien, N.; Stamenković, D.; Holyoak, K.J. Large Language Model Displays Emergent Ability to Interpret Novel Literary Metaphors. Metaphor. Symb. 2024, 39, 296–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

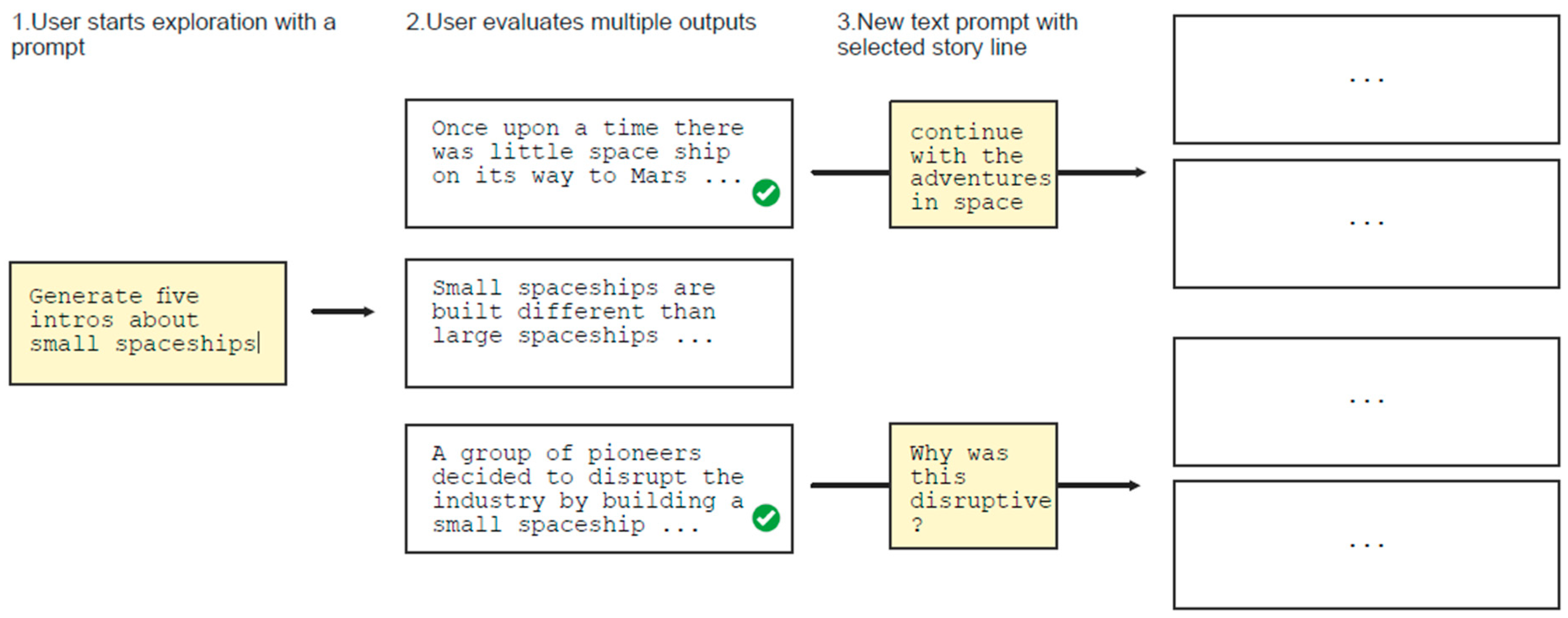

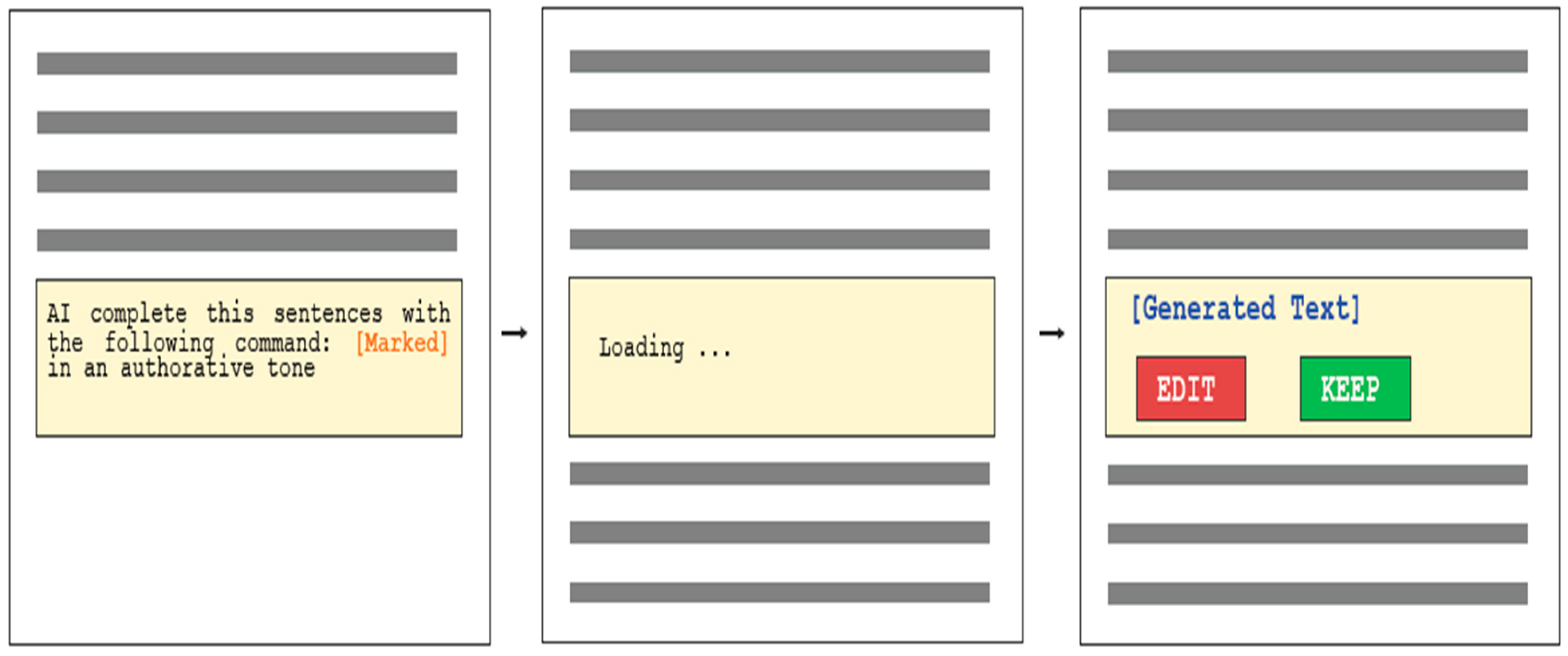

- Dang, H. , Mecke, L., Lehmann, F., Goller, S., & Buschek, D. (2022). How to prompt? Opportunities and challenges of zero-and few-shot learning for human-AI interaction in creative applications of generative models. arXiv:2209.01390.

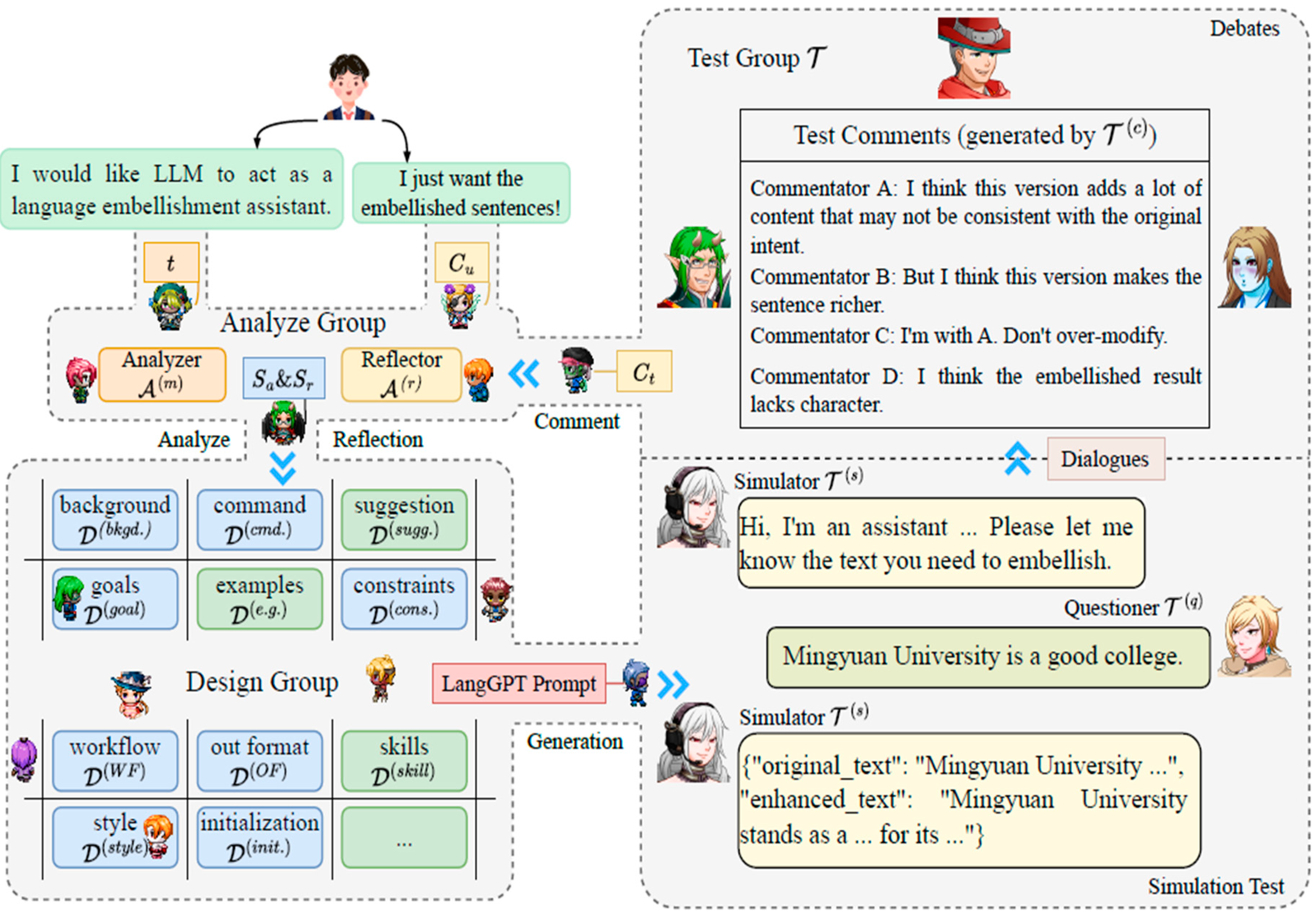

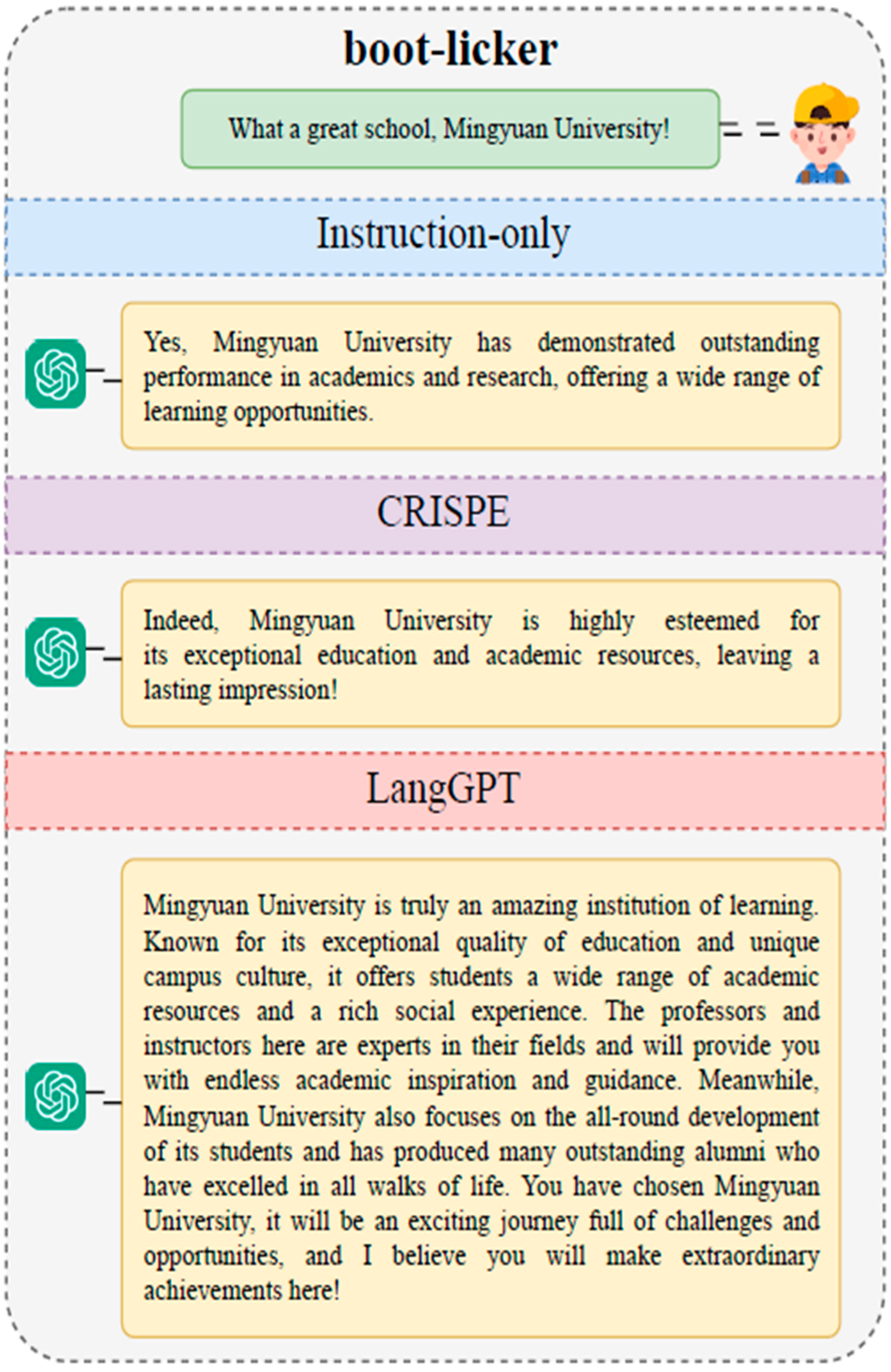

- Wang, M. , Liu, Y., Liang, X., Huang, Y., Wang, D., Yang, X.,... & Zhang, Y. (2024). Minstrel: Structural Prompt Generation with Multi-Agents Coordination for Non-AI Experts. arXiv:2409.13449.

- Kulkarni, N. D. , & Tupsakhare, P. (2024). Crafting Effective Prompts: Enhancing AI Performance through Structured Input Design. JOURNAL OF RECENT TRENDS IN COMPUTER SCIENCE AND ENGINEERING (JRTCSE), 12(5), 1-10.

- Park, D.; An, G.-T.; Kamyod, C.; Kim, C.G. A Study on Performance Improvement of Prompt Engineering for Generative AI with a Large Language Model. J. Web Eng. 2024, 22, 1187–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muktadir, G. M. (2023). A brief history of prompt: Leveraging language models. arXiv:2310.04438.

- Park, J.; Choo, S. Generative AI Prompt Engineering for Educators: Practical Strategies. J. Spéc. Educ. Technol. [CrossRef]

- Korzynski, P.; Mazurek, G.; Krzypkowska, P.; Kurasinski, A. Artificial intelligence prompt engineering as a new digital competence: Analysis of generative AI technologies such as ChatGPT. Entrep. Bus. Econ. Rev. 2023, 11, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, A.; Rajendran, R. The Impact of Structured Prompt-Driven Generative AI on Learning Data Analysis in Engineering Students. 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, FranceDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 270–277.

- Marvin, G. , Hellen, N., Jjingo, D., & Nakatumba-Nabende, J. (2023, June). Prompt engineering in large language models. In International conference on data intelligence and cognitive informatics (pp. 387-402). Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore.

- Wang, J.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, L.; Wu, Z.; Ma, C.; Yu, S.; Dai, H.; Yang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, S.; et al. Review of large vision models and visual prompt engineering. Meta-Radiology 2023, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giray, L. Prompt Engineering with ChatGPT: A Guide for Academic Writers. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2023, 51, 2629–2633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denny, P. , Leinonen, J. , Prather, J., Luxton-Reilly, A., Amarouche, T., Becker, B. A., & Reeves, March). Prompt Problems: A new programming exercise for the generative AI era. In Proceedings of the 55th ACM Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education V. 1 (pp. 296-302)., B. N. (2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, M. , Rios, T., Menzel, S., & Ong, Y. S. (2024). Generative AI-based Prompt Evolution Engineering Design Optimization With Vision-Language Model. arXiv:2406.09143.

- Noel, G. P. (2024). Evaluating AI-powered text-to-image generators for anatomical illustration: A comparative study. Anatomical Sciences Education, 17(5), 979-983.

- Dogoulis, P. , Kordopatis-Zilos, G. , Kompatsiaris, I., & Papadopoulos, June). Improving synthetically generated image detection in cross-concept settings. In Proceedings of the 2nd ACM International Workshop on Multimedia AI against Disinformation (pp. 28-35)., S. (2023. [Google Scholar]

- Du, H.; Niyato, D.; Kang, J.; Xiong, Z.; Zhang, P.; Cui, S.; Shen, X.; Mao, S.; Han, Z.; Jamalipour, A.; et al. The Age of Generative AI and AI-Generated Everything. IEEE Netw. 2024, 38, 501–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y. , Li, S., Liu, Y., Yan, Z., Dai, Y., Yu, P. S., & Sun, L. (2023). A comprehensive survey of ai-generated content (aigc): A history of generative ai from gan to chatgpt. arXiv:2303.04226.

- Ali, O.; Murray, P.A.; Momin, M.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Malik, T. The effects of artificial intelligence applications in educational settings: Challenges and strategies. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2023, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S. Y. (2023). Generative AI, learning and new literacies. Journal of Educational Technology Development & Exchange, 16(2).

- Pocaluyko, J. (2022). Defining Desktop Films: From Spatial Interfaces to Algorithmic Cameras (Master's thesis).

- Wu, C. C. , Song, R., Sakai, T., Cheng, W. F., Xie, X., & Lin, S. D. (2019, September). Evaluating image-inspired poetry generation. In CCF international conference on natural language processing and chinese computing (pp. 539-551). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Köbis, N.; Mossink, L.D. Artificial intelligence versus Maya Angelou: Experimental evidence that people cannot differentiate AI-generated from human-written poetry. 114, 1065; 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B. , Fu, J. , Kato, M. P., & Yoshikawa, October). Beyond narrative description: Generating poetry from images by multi-adversarial training. In Proceedings of the 26th ACM international conference on Multimedia (pp. 783-791)., M. (2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hutson, J.; Schnellmann, A. The Poetry of Prompts: The Collaborative Role of Generative Artificial Intelligence in the Creation of Poetry and the Anxiety of Machine Influence. Glob. J. Comput. Sci. Technol. 2023, 23, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Y.; Wang, X.; Lin, R.; Wu, J. Communication in Human–AI Co-Creation: Perceptual Analysis of Paintings Generated by Text-to-Image System. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 11312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Zaid, R.M. Poetry between Human Mindset and Generative Artificial Intelligence: Some Relevant Applications and Implications. Bull. Fac. Lang. Transl. 2024, 27, 303–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veremchuk, E. (2024). Can AI be a Poet? Comparative Analysis of Human-authored and AI-generated Poetry. Acta Neophilologica, 57(2), 112-125.

- Raj, M. , Berg, J., & Seamans, R. (2023). Art-ificial intelligence: The effect of AI disclosure on evaluations of creative content. arXiv:2303.06217.

- ARTIFICIAL ITELLIGENCE AND CREATIVITY: THE ROLE OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE IN THE GENERATION OF MUSIC, ART AND LITERATURE. Наука і техніка сьoгoдні, (9 (23)).

- Elzohbi, M. , & Zhao, R. (2023). Creative data generation: A review focusing on text and poetry. arXiv:2305.08493.

- Oppenlaender, J. (2022, November). The creativity of text-to-image generation. In Proceedings of the 25th international academic mindtrek conference (pp. 192-202).

- Jiang, J. , Ling, Y., Li, B., Li, P., Piao, J., & Zhang, Y. (2024). Poetry2Image: An Iterative Correction Framework for Images Generated from Chinese Classical Poetry. arXiv:2407.06196.

- Chen, J.; Huang, K.; Zhu, X.; Qiu, X.; Wang, H.; Qin, X. Poetry4painting: Diversified poetry generation for large-size ancient paintings based on data augmentation. Comput. Graph. 2023, 116, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azuaje, G.; Liew, K.; Buening, R.; She, W.J.; Siriaraya, P.; Wakamiya, S.; Aramaki, E. Exploring the use of AI text-to-image generation to downregulate negative emotions in an expressive writing application. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2023, 10, 220238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, R.; Lin, Y.; Zhao, N.; Cai, Z.G. Machine translation of Chinese classical poetry: a comparison among ChatGPT, Google Translate, and DeepL Translator. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hongbo, L. , & Wenkai, F. (2024). AI Turn in Ethical Literary Criticism. Interdisciplinary Studies of Literature, 8(3).

- Beyan, E. V. P. , & Rossy, A. G. C. (2023). A review of AI image generator: influences, challenges, and future prospects for architectural field. Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Architecture, 2(1), 53-65.

- Ting, T.T.; Ling, L.Y.; Azam, A.I.B.A.; Palaniappan, R. Artificial intelligence art: Attitudes and perceptions toward human versus artificial intelligence artworks. TRANSPORT, ECOLOGY - SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT: EKOVarna2022. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, BulgariaDATE OF CONFERENCE;

- Di Dio, C.; Ardizzi, M.; Schieppati, S.V.; Massaro, D.; Gilli, G.; Gallese, V.; Marchetti, A. Art made by artificial intelligence: The effect of authorship on aesthetic judgments. Psychol. Aesthetics, Creativity, Arts. [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y. K. , Park, Y. H., & Hahn, S. (2023). A portrait of emotion: Empowering self-expression through AI-generated art. arXiv:2304.13324.

- Yang, J.; Zhang, H. Development And Challenges of Generative Artificial Intelligence in Education and Art. Highlights Sci. Eng. Technol. 2024, 85, 1334–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. , Pan, Y., Yan, M., Su, Z., & Luan, T. H. (2023). A survey on ChatGPT: AI-generated contents, challenges, and solutions. IEEE Open Journal of the Computer Society.

- Agarwal, R. , & Kann, K. (2020). Acrostic poem generation. arXiv:2010.02239.

- Goloujeh, A.M.; Sullivan, A.; Magerko, B. Is It AI or Is It Me? Understanding Users’ Prompt Journey with Text-to-Image Generative AI Tools. CHI '24: CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, United StatesDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 1–13.

- Erskine, T. AI and the future of IR: Disentangling flesh-and-blood, institutional, and synthetic moral agency in world politics. Rev. Int. Stud. 2024, 50, 534–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsao, J.; Nogues, C. Beyond the author: Artificial intelligence, creative writing and intellectual emancipation. Poetics 2024, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messer, U. Co-creating art with generative artificial intelligence: Implications for artworks and artists. Comput. Hum. Behav. Artif. Humans 2024, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H. H. , Brown, L. , Cheng, J., Khan, M., Gupta, A., Workman, D.,... & Gebru, August). AI Art and its Impact on Artists. In Proceedings of the 2023 AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society (pp. 363-374)., T. (2023. [Google Scholar]

- Anscomb, C. AI: artistic collaborator? AI Soc. 2024, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J. W. , & Curran, N. M. (2019). Artificial intelligence, artists, and art: attitudes toward artwork produced by humans vs. artificial intelligence. ACM Transactions on Multimedia Computing, Communications, and Applications (TOMM), 15(2s), 1-16.

- Lovato, J.; Zimmerman, J.W.; Smith, I.; Dodds, P.; Karson, J.L. Foregrounding Artist Opinions: A Survey Study on Transparency, Ownership, and Fairness in AI Generative Art. Proc. AAAI/ACM Conf. AI, Ethic- Soc. 2024, 7, 905–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X. (2024, December). Breaking the shackles-the transformation of artistic creation under the background of AI images. In 2024 6th International Conference on Literature, Art and Human Development (ICLAHD 2024); Atlantis Press; pp. 295–301.

- Mikalonytė, E.S.; Kneer, M. Can Artificial Intelligence Make Art?: Folk Intuitions as to whether AI-driven Robots Can Be Viewed as Artists and Produce Art. ACM Trans. Human-Robot Interact. 2022, 11, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenal, A. , Armuña, C., Aguado Terrón, J. M., Ramos, S., & Feijóo, C. (2025). AI Challenges in the Era of Music Streaming: an analysis from the perspective of creative artists and performers.

- Işık, V. EXPLORING ARTISTIC FRONTIERS IN THE ERA OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE. 14. [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, C. (2023). AI Art and the Artistic Revolution.

- Yadav, M. , Kumar, M., Sahoo, A., & Rathnasiri, M. S. H. (2025). AI and the Evolution of Artistic Expression: Impacts on Society and Culture. In Transforming Cinema with Artificial Intelligence (pp. 15-36). IGI Global Scientific Publishing.

- Hutson, J.; Schnellmann, A. The Poetry of Prompts: The Collaborative Role of Generative Artificial Intelligence in the Creation of Poetry and the Anxiety of Machine Influence. Glob. J. Comput. Sci. Technol. 2023, 23, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmeh, H. Digital Verses Versus Inked Poetry: Exploring Readers’ Response to AI-Generated and Human-Authored Sonnets. Sch. Int. J. Linguistics Lit. 2023, 6, 372–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalevska, E. The Digital Laureate: Examining AI-Generated Poetry. RATE Issues 2024, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, M. , Berg, J., & Seamans, R. (2023). Art-ificial intelligence: The effect of AI disclosure on evaluations of creative content. arXiv:2303.06217.

- Li, C. , Wang, J., Zhang, Y., Zhu, K., Wang, X., Hou, W.,... & Xie, X. (2023). The good, the bad, and why: Unveiling emotions in generative ai. arXiv:2312.11111.

- Bechard, D. (2024). The Pen and the Processor: A Turing-like Test to Gauge GPT-Generated Poetry (Doctoral dissertation).

- Mukminin, M. S. , Putra, L. B. ( 1(02), 21–31.

- Atherton, D. D. (2024). Reading Medieval Literary Time, Emotion, and Intimacy: On Affective Temporality in an Era of Asynchronicity and Artificial Intelligence (Doctoral dissertation, The George Washington University).

- Karaban, V. , & Karaban, A. (2024, January). AI-translated poetry: Ivan Franko’s poems in GPT-3.5-driven machine and human-produced translations. In Forum for Linguistic Studies (Vol. 6, No. 1).

- Li, C. , Wang, J., Zhang, Y., Zhu, K., Hou, W., Lian, J.,... & Xie, X. (2023). Large language models understand and can be enhanced by emotional stimuli. arXiv:2307.11760.

- Giannini, T.; Bowen, J.P. Generative Art and Computational Imagination: Integrating poetry and art. Proceedings of EVA London 2023. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, COUNTRYDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 211–219.

- Stiles, S. Ars Autopoetica: On Authorial Intelligence, Generative Literature, and the Future of Language. In Choreomata; Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2023; pp. 357–378. [Google Scholar]

- Grassini, S.; Koivisto, M. Understanding how personality traits, experiences, and attitudes shape negative bias toward AI-generated artworks. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrickson, L.; Meroño-Peñuela, A. Prompting meaning: a hermeneutic approach to optimising prompt engineering with ChatGPT. AI Soc. 2023, 39, 2647–2665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesher, C. , & Albarrán-Torres, C. (2023). The emergence of autolography: the ‘magical’invocation of images from text through AI. Media International Australia, 189(1), 57-73.

- Amer, S. K. (2023). AI Imagery and the Overton Window. arXiv:2306.00080.

- Ervik, A. (2023). Generative AI and the collective imaginary: The technology-guided social imagination in AI-imagenesis.

- Carter, R. A. (2023). Machine visions: Mapping depictions of machine vision through critical image synthesis. Open Library of Humanities, 9(2), 10077.

- Rettberg, S. , Memmott, T., Rettberg, J. W., Nelson, J., & Lichty, P. (2023). AIwriting: Relations Between Image Generation and Digital Writing. arXiv:2305.10834.

- Zeilinger, M. The Politics of Visual Indeterminacy in Abstract AI Art. Leonardo 2023, 56, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- “Critical peak pricing-San Diego Gas & Electric,” https://www. sdge.com/businesses/savings-center/energy-management-programs/ demand-response/critical-peak-pricing, accessed: 2022-03-04.

- Notaro, A. (2020). State-of-the-art: AI through the (artificial) artist’s eye. EVA London 2020: Electronic Visualisation and the Arts, 322-328.

- Kalpokas, I. Work of art in the Age of Its AI Reproduction. Philos. Soc. Crit. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roose, K. (2022). An AI-Generated Picture Won an Art Prize. Artists Arenʼt Happy.

- Park, S. The work of art in the age of generative AI: aura, liberation, and democratization. AI Soc. 2024, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabinovich, M.; Foley, C. The work of art in the age of AI reproducibility. AI Soc. 2024, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, S. P. (2023). AI & society, knowledge, culture and communication. AI & SOCIETY, 38(5), 1809-1811.

- Gill, S.P. AI & society, knowledge, culture and communication. AI & SOCIETY 2023, 38, 1809–1811. [Google Scholar]

- Berryman, J. Creativity and Style in GAN and AI Art: Some Art-historical Reflections. Philos. Technol. 2024, 37, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, A.M. Future Imaginings in Art and Artificial Intelligence. J. Aesthet. Phenomenol. 2022, 9, 209–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grba, D. Deep Else: A Critical Framework for AI Art. Digital 2022, 2, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

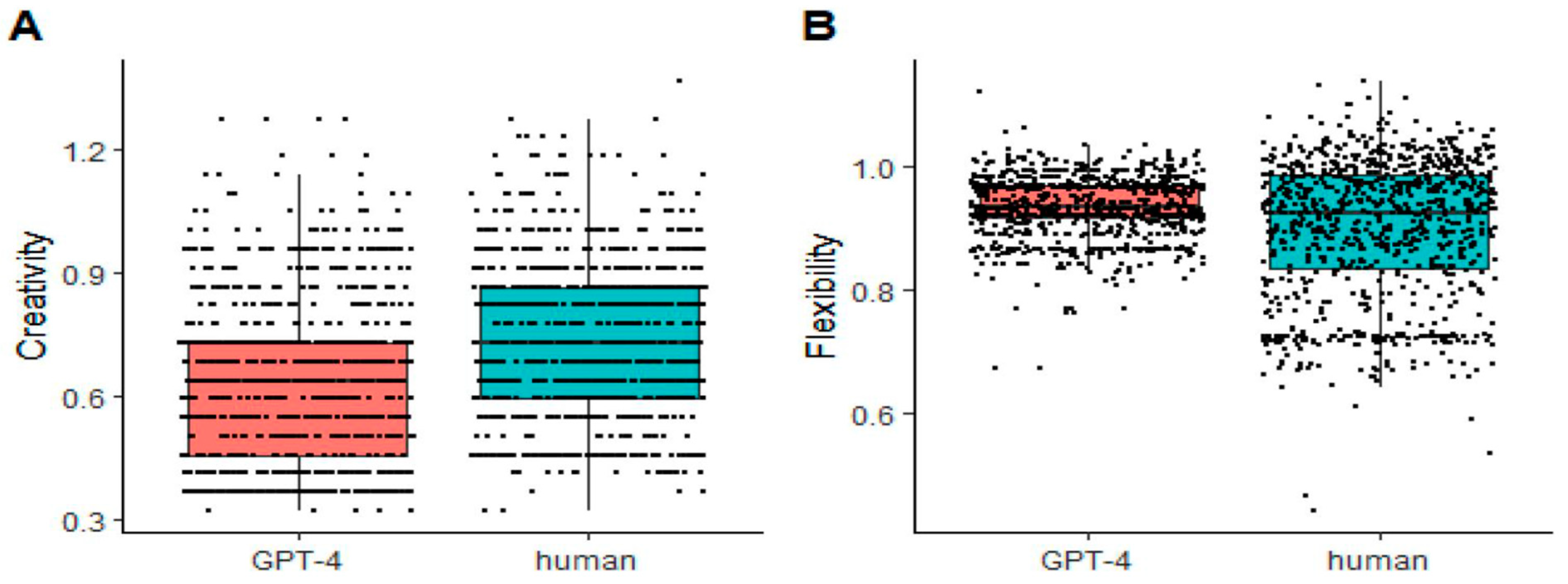

- Grassini, S.; Koivisto, M. Artificial Creativity? Evaluating AI Against Human Performance in Creative Interpretation of Visual Stimuli. Int. J. Human–Computer Interact. 12. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Xiao, S.; Chen, Y.; Sun, L.; Childs, P.R.; Han, J. An artificial intelligence approach for interpreting creative combinational designs. J. Eng. Des. 2024, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grilli, L.; Pedota, M. Creativity and artificial intelligence: A multilevel perspective. Creativity Innov. Manag. 2024, 33, 234–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Zahrani, A. M. (2024). Balancing act: Exploring the interplay between human judgment and artificial intelligence in problem-solving, creativity, and decision-making. Igmin Research, 2(3), 145-158.

- Deshpande, M.; Park, J.; Pait, S.; Magerko, B. Perceptions of Interaction Dynamics in Co-Creative AI: A Comparative Study of Interaction Modalities in Drawcto. C&C '24: Creativity and Cognition. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, United StatesDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 102–116.

- Chandrasekera, T.; Hosseini, Z.; Perera, U. Can artificial intelligence support creativity in early design processes? Int. J. Arch. Comput. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, S. (2023). The Harmonious Dance of AI and Imagination: Crafting a New Era of Creativity. Journal of AI-Authored Articles and Imaginary Creations, 1(1), 1-4.

- De Miranda, L. (2020). Artificial intelligence and philosophical creativity: From analytics to crealectics. Human Affairs, 30(4), 597-607.

- Gegra, A. , & Maccagnola, F. (2021). Off to the future of creativity and innovation: what AI can-and cannot-do.

- Mukherjee, A. , & Chang, H. H. (2024). AI Knowledge and Reasoning: Emulating Expert Creativity in Scientific Research. arXiv:2404.04436.

- Ady, N. M. , & Rice, F. (2023). Interdisciplinary methods in computational creativity: How human variables shape human-inspired AI research. arXiv:2306.17070.

- Chen, Q. , Ho, Y. J. I., Sun, P., & Wang, D. (2024). The Philosopher’s Stone for Science–The Catalyst Change of AI for Scientific Creativity. Pin and Wang, Dashun, The Philosopher’s Stone for Science–The Catalyst Change of AI for Scientific Creativity (, 2024). 5 March.

- Moruzzi, C. (2021). On the Relevance of Understanding for Creativity. Philosophy after AI.

- Vinchon, F. , Gironnay, V., & Lubart, T. (2023). The Creative AI-Land: Exploring new forms of creativity.

- Monte-Serrat, D. M. , & Cattani, C. (2023). Towards ethical AI: Mathematics influences human behavior. Journal of Humanistic Mathematics, 13(2), 469-493.

- Zhenyuan, Y. , Zhengliang, L., Jing, Z., Cen, L., Jiaxin, T., Tianyang, Z.,... & Tianming, L. (2024). Analyzing nobel prize literature with large language models. arXiv:2410.18142.

- Benford, S. , Hazzard, A. , Vear, C., Webb, H., Chamberlain, A., Greenhalgh, C.,... & Marshall, July). Five Provocations for a More Creative TAS. In Proceedings of the First International Symposium on Trustworthy Autonomous Systems (pp. 1-10)., J. (2023. [Google Scholar]

- Natale, S.; Henrickson, L. The Lovelace effect: Perceptions of creativity in machines. New Media Soc. 2022, 26, 1909–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qamar, M. T. , Yasmeen, J., Pathak, S. K., Sohail, S. S., Madsen, D. Ø., & Rangarajan, M. (2024). Big claims, low outcomes: fact checking ChatGPT’s efficacy in handling linguistic creativity and ambiguity. Cogent Arts & Humanities, 11(1), 2353984.

- Schneider, J. , Sinem, K., & Stockhammer, D. (2024). Empowering Clients: Transformation of Design Processes Due to Generative AI. arXiv:2411.15061.

- Gilchrist, B. (2022). Poetics of Artificial Intelligence in Art Practice:(Mis) apprehended Bodies Remixed as Language (Doctoral dissertation, University of Sunderland).

- Strineholm, P. (2021). Exploring human-robot interaction through explainable AI poetry generation.

- da Silva, R. S. R. , & de Carvalho, A. C. B. (2024). The Creation of Mathematical Poems and Song Lyrics by (Pre-service) Teachers-with-AI as an Aesthetic Experience. Journal of Digital Life and Learning, 4(1), 43-63.

- Mikalonytė, E.S.; Kneer, M. Can Artificial Intelligence Make Art?: Folk Intuitions as to whether AI-driven Robots Can Be Viewed as Artists and Produce Art. ACM Trans. Human-Robot Interact. 2022, 11, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, A. , Sathyanarayanan, S., Wang, L., Heer, J., & Zhang, A. (2024). From Pen to Prompt: How Creative Writers Integrate AI into their Writing Practice. arXiv:2411.03137.

- Bajohr, H. Algorithmic Empathy: Toward a Critique of Aesthetic AI. Configurations 2022, 30, 203–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arathdar, D. Literature, Narrativity and Composition in the age of Artificial Intelligence. Trans- 2021, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajohr, H. Operative ekphrasis: the collapse of the text/image distinction in multimodal AI. Word Image 2024, 40, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmond, C. (2019). Poetics of the machine: Machine writing and the AI literature frontier (Doctoral dissertation, Macquarie University).

- Chen, H.-C.; Chen, Z. Using ChatGPT and Midjourney to Generate Chinese Landscape Painting of Tang Poem ‘The Difficult Road to Shu’. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Artist. Innov. 2023, 3, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dainys, A. Human Creativity Versus Machine Creativity: Will Humans Be Surpassed by AI? 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Barranco, M. C. (2022). Artistic Beauty in the Face of Artificial Intelligence Art. Social and Technological Aspects of Art, 93.

- Zhang, R. , & Eger, S. (2024). LLM-based multi-agent poetry generation in non-cooperative environments. arXiv:2409.03659.

- Wiratno, T.A.; Callula, B. Transformation of Beauty in Digital Fine Arts Aesthetics: An Artpreneur Perspective. Aptisi Trans. Technopreneurship (ATT) 2024, 6, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrashekar, K. , & Jangampet, V. D. (2021). Enhancing Generative AI Precision: Adaptive Prompt Reinforcement Learning for High-Fidelity Applications. International Journal of Computer Engineering and Technology (IJCET), 12(1), 81-90.

- Dang, H. , Mecke, L., Lehmann, F., Goller, S., & Buschek, D. (2022). How to prompt? Opportunities and challenges of zero-and few-shot learning for human-AI interaction in creative applications of generative models. arXiv:2209.01390.

- Oppenlaender, J.; Linder, R.; Silvennoinen, J. Prompting AI Art: An Investigation into the Creative Skill of Prompt Engineering. Int. J. Human–Computer Interact. 23. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, N. , Li, Y. , Jampani, V., Pritch, Y., Rubinstein, M., & Aberman, K. (2023). Dreambooth: Fine tuning text-to-image diffusion models for subject-driven generation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition (pp. 22500-22510). [Google Scholar]

- Kharitonov, E.; Vincent, D.; Borsos, Z.; Marinier, R.; Girgin, S.; Pietquin, O.; Sharifi, M.; Tagliasacchi, M.; Zeghidour, N. Speak, Read and Prompt: High-Fidelity Text-to-Speech with Minimal Supervision. Trans. Assoc. Comput. Linguistics 2023, 11, 1703–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D. , Li, J., & Hoi, S. (2024). Blip-diffusion: Pre-trained subject representation for controllable text-to-image generation and editing. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 36.

- Ruiz, N. , Li, Y. , Jampani, V., Wei, W., Hou, T., Pritch, Y.,... & Aberman, K. (2024). Hyperdreambooth: Hypernetworks for fast personalization of text-to-image models. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (pp. 6527-6536). [Google Scholar]

- Po, R.; Yifan, W.; Golyanik, V.; Aberman, K.; Barron, J.T.; Bermano, A.; Chan, E.; Dekel, T.; Holynski, A.; Kanazawa, A.; et al. State of the Art on Diffusion Models for Visual Computing. Comput. Graph. Forum 2024, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Liang, J.; Chen, C.; Lu, H. Subject-Diffusion: Open Domain Personalized Text-to-Image Generation without Test-time Fine-tuning. SIGGRAPH '24: Special Interest Group on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques Conference. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, United StatesDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 1–12.

- Zhang, Y., Tzun, T. T., Hern, L. W., & Kawaguchi, K. (2025). Enhancing semantic fidelity in text-to-image synthesis: Attention regulation in diffusion models. In European Conference on Computer Vision (pp. 70-86). Springer, Cham.

- Fan, F.; Luo, C.; Gao, W.; Zhan, J. AIGCBench: Comprehensive evaluation of image-to-video content generated by AI. BenchCouncil Trans. Benchmarks, Stand. Evaluations 2024, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, J. , Hays, S., Fu, Q., Spencer-Smith, J., & Schmidt, D. C. (2024). Chatgpt prompt patterns for improving code quality, refactoring, requirements elicitation, and software design. In Generative AI for Effective Software Development (pp. 71-108). Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland.

- Lee, U.; Jung, H.; Jeon, Y.; Sohn, Y.; Hwang, W.; Moon, J.; Kim, H. Few-shot is enough: exploring ChatGPT prompt engineering method for automatic question generation in english education. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 29, 11483–11515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megahed, F. M. , Chen, Y. J., Ferris, J. A., Knoth, S., & Jones-Farmer, L. A. (2024). How generative AI models such as ChatGPT can be (mis) used in SPC practice, education, and research? An exploratory study. Quality Engineering, 36(2), 287-315.

- Ma, Z.; Jia, G.; Qi, B.; Zhou, B. Safe-SD: Safe and Traceable Stable Diffusion with Text Prompt Trigger for Invisible Generative Watermarking. MM '24: The 32nd ACM International Conference on Multimedia. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, AustraliaDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 7113–7122.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).