Submitted:

03 January 2025

Posted:

06 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

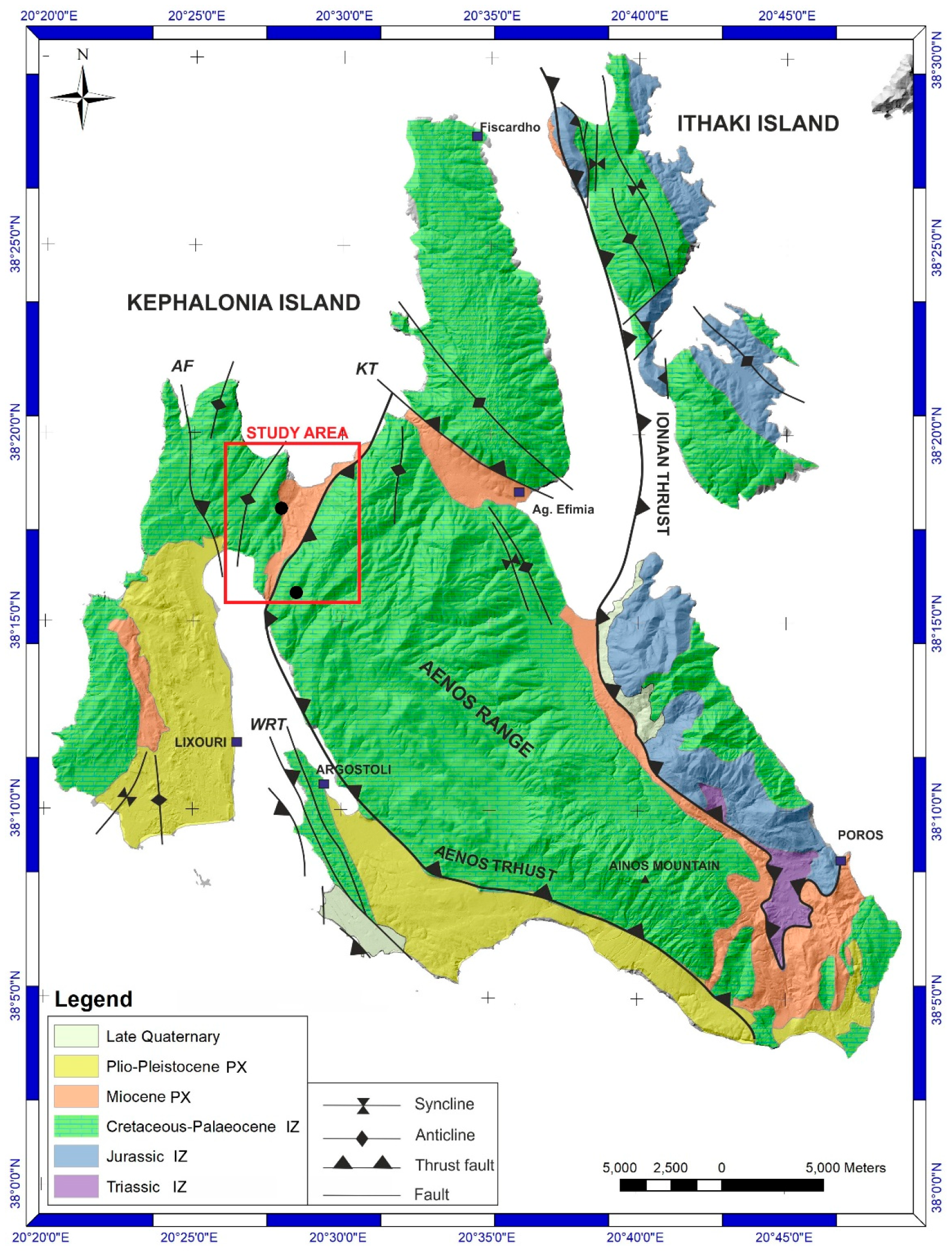

2. Geological Setting and Samples

3. Methodology

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McKenzie, D. P. 1978. Active tectonics of the Alpine-Himalayan belt: the Aegean Sea and surrounding regions, Geophys. J. R. astr. Soc., 55, 217-254.

- Le Pichon, X. , Lyberis. N., Angelier, J., Renards, V. 1982. Tectonophysics, 243-274.

- Underhill, J. R. 1989. Late Cenozoic Deformation of the Hellenic Foreland, Western Greece. Geological Society of America Bulletin, 101, 613-634.

- Royden, L.H. 1993. The tectonic expression slab pull at continental convergent boundaries. Tectonics, 12, 303-325.

- Louvari, E. , Kiratzi, A.A., Papazachos, B.C. 1999. The Cephalonia transform fault and its extension to western Lefkada Island (Greece). Tectonophysics, 308, 223–236.

- Özbakir, A.D. , Govers, R., Fichtner, A. 2020. The Kefalonia Transform Fault: A STEP fault in the making. Tectonophysics, 787, 228471.

- Baker, C. , Hatzfeld, D., Lyon-Caen, H., Papadimitriou, E., Rigo, A. 1997. Earthquake mechanisms of the Adriatic Sea and Western Greece: Implications for the oceanic subduction-continental collision transition. Geophysical Journal International, 131, 559-594.

- Papadimitriou, E.E. 2002. Mode of strong earthquake recurrence in the central Ionian Islands (Greece): Possible triggering due to Coulomb stress changes generated by the occurrence of previous strong shocks. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 92, 3293-3308.

- Papazachos, C.B. , Kiratzi, A.A. 1996. A detailed study of the active crustal deformation in the Aegean and surrounding area. Tectonophysics,253, 129-153.

- Kahle, H.G. , Müller, M.V., Geiger, A., Danuser, G., Mueller, S., Veis, G., Billiris, H., Paradissis, D. 1995. The strain field in northwestern Greece and the Ionian Islands: Results inferred from GPS measurements. Tectonophysics, 249, 41–52.

- Cocard, M. , Kahle, H.G., Peter, Y., Geiger, A., Veis, G., Felekis, S., Paradissis, D., Billiris, H. 1999. New constraints on the rapid crustal motion of the Aegean region: Recent results inferred from GPS measurements (1993–1998) across the West Hellenic Arc, Greece. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett., 172, 39–47.

- Kourouklas, C. , Papadimitriou, E., Karakostas, V. 2023. Long-Term Recurrence Pattern and Stress Transfer along the Kefalonia Transform Fault Zone (KTFZ), Greece: Implications in Seismic Hazard Evaluation. Geosciences, 13, 295.

- Scordilis, E. , Karakaisis, G.F., Karakostas, V., Panagiotopoulos, D.G., Comninakis, P.E., Papazachos, B.C. 1985. Evidence for Transform Faulting in the Ionian Sea: The Cephalonia Island earthquake sequence of 1983. Pure Appl. Geophys., 123, 388–397.

- Kiratzi, A. , Langston, C. 1991. Moment tensor inversion of the 1983 January 17 Kefallinia event of Ionian Island (Greece). Geophys. J. Int., 105, 529–538.

- Papadimitriou, E. 1993. Focal mechanisms along the convex side of the Hellenic Arc. Boll. Geof. Teor. Appl., 140, 401–426.

- Triantafyllou, I. , Papadopoulos, G.A. 2023. Earthquakes in the Ionian Sea, Greece, Documented from Little-Known Historical Sources: AD 1513–1900. Geosciences, 13, 285.

- Pirazzoli, P. , Stiros, S., Laborel, J., Laborel-Deguen, F., Arnold, M., Papageorgiou, S., Morhangel, C. 1994. Late-Holocene shoreline changes related to palaeoseismic events in the Ionian Islands, Greece. Holocene, 4, 397–405.

- Stiros, S. , Pirazzoli, P.A., Laborel, J., Laborel-Doguen, F. 1994. The 1953 earthquake in Cephalonia (Western Hellenic Arc): Coastal uplift and halotectonic faulting. Geophys. J. Int., 117, 834–849.

- Rondoyianni, T., Sakellariou, M., Baskoutas, J., Christodoulou, N. 2012. Evaluation of active faulting and earthquake secondary effects in Lefkada Island, Ionian Sea, Greece: an overview, Natural Hazards, 61, 843-850.

- Papadopoulos, G.A., Karastathis, V.K., Koukouvelas, I., Sachpazi, M., Baskoutas, G., Agalos, A., Daskalaki, E., Minadakis. G., Moshou, A., Mouzakiotis, A., Orfanogiannaki, K., Papageorgiou, A., Spanos, D., Triantafyllou, I. 2014. The Cephalonia, Ionian Sea (Greece), sequence of strong earthquakes of January– February 2014: a first report. Res Geophys. [CrossRef]

- Lekkas, E.L. , Mavroulis, S.D. 2014. Earthquake environmental effects and ESI 2007 seismic intensities of the early 2014 Cephalonia (Ionian Sea, Western Greece) earthquakes (January 26 and February 3, Mw 6.0). Nat. Hazards, 78, 1517–1544.

- Valkaniotis, S. , Ganas, A., Papathanasiou, G., Papanikolaou, M. 2014. Field observations of geological effects triggered by the January–February 2014 Cephalonia (Ionian Sea, Greece) earthquakes. Tectonophysics, 630, 150 -157.

- Mavroulis, S., Lekkas, E. 2021. Revisiting the Most Destructive Earthquake Sequence in the Recent History of Greece: Environmental Effects Induced by the 9, 11 and 12 August 1953 Ionian Sea Earthquakes. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 8429. [CrossRef]

- Mavroulis, S. , Diakakis, M., Kranis, H., Vassilakis, E., Kapetanidis, V., Spingos, I., Kaviris, G., Skourtsos, E., Voulgaris, N., Lekkas, E. 2022. Inventory of Historical and Recent Earthquake-Triggered Landslides and Assessment of Related Susceptibility by GIS-Based Analytic Hierarchy Process: The Case of Cephalonia (Ionian Islands,Western Greece). Appl. Sci., 12, 2895.

- Jenkins, D. A. L. 1972. Structural development of Western Greece. AAPG Bulletin, 56, 128–149.

- Underhill, J.R. 1988. Triassic Evaporites and Plio-Quaternary Diapirism in Western Greece. Journal of the Geological Society of London, 145, 209-282.

- Le Pichon, X. and Angelier, J. 1979. The hellenic arc and trench system: A key to the neotectonic evolution of the eastern mediterranean area. Tectonophysics, 60, 1-42.

- Karakostas, V.G. , Papadimitriou, E.E. and Papazachos, C.B. 2004. Properties of the 2003 Lefkada, Ionian Islands, Greece, earthquake seismic sequence and seismicity triggering, Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am., 94, 1976–1981.

- Ganas, A. , Elias, P., Bozionelos, G., Papathanassiou, G., Avallone, A., Papastergios, A., Valkaniotis, S., Parcharidis, I., Briole, P. Coseismic deformation, field observations and seismic fault of the 17 November 2015 M = 6.5, Lefkada Island, Greece earthquake. Tectonophysics, 687, 210-222.

- Saltogianni, V. , Moschas, F., Stiros, S. 2018. The 2014 Cephalonia Earthquakes: Finite Fault Modeling, Fault Segmentation, Shear and Thrusting at the NW Aegean Arc (Greece). Pure Appl. Geophys., 175, 4145-4164.

- Svigkas, N. , Atzori, S., Kiratzi, A., Tolomei, C., Antonioli, A., Papoutsis, I., Salvi, S., Kontoes, C. 2019. On the Segmentation of the Cephalonia–Lefkada Transform Fault Zone (Greece) from an InSAR Multi-Mode Dataset of the Lefkada 2015 Sequence. Remote Sens., 11, 1848.

- Royden, L.H. and Papanikolaou, D.J. 2011. Slab segmentation and late Cenozoic disruption of the Hellenic arc. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems, 12, Q03010.

- Hermanns, R. L. , Niedermann, S., Villanueva Garcia, A., Sosa Gomez, J. and Strecker, M. R. 2001. Neotectonics and catastrophic failure of mountain fronts in the southern intra-Andean Puna Plateau, Argentina. Geology, 29, 619–623.

- Hermanns, R. L. and Strecker, M. R. 1999. Structural and lithological controls on large Quaternary rock avalanches (sturzstroms) in arid northwestern Argentina. Geological Society of America Bulletin, 111, 934–948.

- Strecker, M. R. and Marrett, R. 1999. Kinematic evolution of fault ramps and its role in development of landslides and lakes in the northwestern Argentine Andes. Geology, 27, 307–310.

- Jackson, L. E., Jr. 2002. Landslides and landscape evolution in the Rocky Mountains and adjacent foothills area, southwestern Alberta, Canada. In Catastrophic Landslides, ed. S. G. Evans and J. V. DeGraff. Geological Society of America, Reviews in Engineering Geology 15, 325–344.

- Agliardi, F. , Zanchi, A. and Crosta, G. B. 2009a. Tectonic vs. gravitational morphostructures in the central Eastern Alps (Italy): Constraints on the recent evolution of the mountain range. Tectonophysics, 474, 250–270.

- Agliardi, F. , Crosta, G. B., Zanchi, A. and Ravazzi, C. 2009b. Onset and timing of deep-seated gravitational slope deformations in the eastern Alps, Italy. Geomorphology, 103, 113–129.

- Penna, I. , Hermanns, R. L., Folguera, A. and Niedermann, S. 2011.Multiple slope failures associated with neotectonic activity in the southern central Andes (37°–37°30′S). Patagonia, Argentina. Geological Society of America Bulletin, 123, 1880–1895.

- Underhill, J.R. 2006. Quest for Ithaca. Geoscientist 16, 9, 4-29.

- Underhill, J. 2009. Relocating Odysseus’ Homeland. Nature Geoscience, 2, 455-458.

- Oldrich, H., Leroueil, S., Picarelli, L. 2014. The Varnes classification of landslide types, an update. Landslides, 11, 167-194.

- Pérouse, E., Sébrier, M., Braucher, R., Chamot-Rooke, N., Bourles, D., Briole, P., Sorel. D., Dimitrov, D., Arsenikos, S. 2017. Transition from collision to subduction in Western Greece: the Katouna–Stamna active fault system and regional kinematics. International Journal of Earth Sciences, 2017, 106, 967–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechernich, S. , Schneiderwind, S., Mason, J., Papanikolaou, I. D., Deligiannakis, G., Pallikarakis, A., Binnie, A.S., Dunai, T.J., Reicherter, K. 2018. The Seismic History of the Pisia Fault (Eastern Corinth Rift, Greece) from Fault Plane Weathering Features and Cosmogenic 36Cl Dating. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth, 123, 4266–4284.

- Iezzi, F. , Roberts, G., Faure Walker, J., Papanikolaou, I., Ganas, A., Deligiannakis, G., Beck, J., Wolfers, S., Gheorghiu, D. 2021. Temporal and spatial earthquake clustering revealed through comparison of millennial strain-rates from 36Cl cosmogenic exposure dating and decadal GPS strain-rate. Sci Rep 11, 23320.

- Mechernich, S. , Reicherter, K., Deligiannakis, G., Papanikolaou, I. 2023. Tectonic geomorphology of active faults in Eastern Crete (Greece) with slip rates and earthquake history from cosmogenic 36Cl dating of the Lastros and Orno faults. Quaternary International, 30, 77-91.

- Zreda, M.G., and Noller, F.M. 1998. Ages of prehistoric earthquakes revealed by cosmogenic chlorine-36 in a bedrock fault scarp at Hebgen Lake: Science, 282, 1097–1099.

- Schlagenhauf, A. , Gaudemer, Y., Benedetti, L., Manighetti, I., Palumbo, L., Schimmelpfennig, I., Finkel, R., Pou, K., 2010. Using in situ chlorine-36 cosmonuclide to recover past earthquake histories on limestone normal fault scarps: a reappraisal of methodology and interpretations. Geophys. J. Int. 182, 36-72.

- Mouslopoulou, V. , Moraetis, D., Benedetti, L., Guillou, V., Bellier, O., Hristopulos, D. 2014. Normal faulting in the forearc of the Hellenic subduction margin: Paleoearthquake history and kinematics of the Spili Fault, Crete, Greece. Journal of Structural Geology, 66, 298-308.

- Benedetti, L. , Finkel, R., King, G., Armijo, R., Papanastasiou, D., Ryerson, F.J., Flerit, F., Farber, D., Stavrakakis, G. 2001. Motion on the Kaparelli fault (Greece) prior to the 1981 earthquake sequence determined from 36Cl cosmogenic dating. Terra Nova, 15, 118-124.

- Benedetti, L. , Finkel, R., Papanastasiou, D., King, G., Armijo, R., Ryerson, F.J., Farber, D., Flerit, F. 2002. Post-glacial slip history of the Sparta fault (Greece) determined by 36Cl cosmogenic dating: Evidence for non-periodic earthquakes. Geophysical Research Letters, 29, 1246.

- Benavente, C. , Zerathe, S., Audin, L., Hall, S.R., Robert, X., Delgado, F., Carcaillet, J., ASTER Team. 2017. Active transpressional tectonics in the Andean forearc of southern Peru quantified by 10Be surface exposure dating of an active fault scarp. Tectonics, 36, 1662-1678.

- Bierman, P.R. , Gillespie, A.R., and Caffee, M.W. 1995. Cosmogenic ages for earthquake recurrence intervals and debris flow fan deposition, Owens Valley, Science, 270, 447–450.

- Ballantyne, C.K., Stone, J.O., and Fifi eld, L.K. 1998. Cosmogenic Cl-36 dating of post-glacial landsliding at The Storr, Isle of Skye, Scotland: The Holocene, 8, 347–351.

- Sewell, R.J. , Barrows, T.T., Campbell, S.D., Fifield, L.K. 2006. Exposure dating (10Be, 26Al) of natural terrain landslides in Hong Kong, China. Geological Society of America Special Paper 415, 131 – 146.

- Le Roux, O. , Schwartz, S., Gamond, J.F., Jongmans, D., Bourles, D., Braucher, R., Mahaney, W., Carcaillet, J., Leanni, L. 2009. CRE dating on the head scarp of a major landslide (Séchilienne, French Alps), age constraints on Holocene kinematics. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 280, 236-245.

- Merchel, S. , Braucher, R., Alfimov, V., Bichler, M., Bourles, D.L., Reitner, J. 2013. The potential of historic rock avalanches and man-made structures as chlorine-36 production rate calibration sites. Quaternary Geochronology, 18, 54-62.

- Zerathe, S. , Braucher, R., Lebourg, T., Bourlès, D., Manetti, M., Leanni, L. 2013. Dating chert (diagenetic silica) using in-situ produced 10Be: possible complications revealed through the comparison with 36Cl applied on coexisting limestone. Quat. Geochronol. 17, 81–93.

- Pánek, T. 2015. Recent progress in landslide dating: A global overview. Progress in Physical Geography, 39, 168–198.

- Athanassas, C.D. , Bourlès, D.L., Bracucher, R., Druitt, T.H., Nomikou, P., Leanni, L. 2016. Evidence from cosmic ray exposure (CRE) dating for the existence of a pre-Minoan caldera on Santorini, Greece. Bulletin of Volcanology, 78: 35.

- Schwartz, S. , Zerathe, S., Jongmans, D., Baillet, L., Carcailet, J., Audin, L., Dumont, T., Bourlès, D., Braucher, R., Lebrouc, V. 2017. Cosmic ray exposure dating on the large landslide of Séchilienne (Western Alps): A synthesis to constrain slope evolution. Geomorphology, 278, 329-344.

- Hilger, P. , Hermanns, R.L., Gosse, J.C., Jacobs, B., Etzelmüller, B., Krautblatter, M. 2018. Multiple rock-slope failures from Mannen in Romsdal Valley, western Norway, revealed from Quaternary geological mapping and 10Be exposure dating. Holocene, 28, 1841–1854.

- Lekkas, E. and Mavroulis, S. 2016. Fault zones ruptured during the early 2014 Cephalonia Island (Ionian Sea, Western Greece) earthquakes (January 26 and February 23, Mw 6.0) based on the associated co-seismic surface ruptures. Journal of Seismology, 20, 63-78.

- British Petroleum Company (1971) The Geological Results of Petroleum Exploration in Western Greece: Institute of Geology Subsurface Research, Athens, 10, 73.

- Gosgrove, J.W. 2015. The association of folds and fractures and the link between folding, fracturing and fluid flow during the evolution of a fold–thrust belt: a brief review. In: Richards, F. L., Richardson, N. J., Rippington, S. J., Wilson, R.W. & Bond, C. E. (eds) Industrial Structural Geology: Principles, Techniques and Integration. Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 421.

- Lal, D. , 1991. Cosmic ray labeling of erosion surfaces: in situ nuclide production rates and erosion models. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 104, 424-439.

- Stone, J.O.H. , Evans, J.M., Fifield, L.K., Allan, G.L., Cresswell B, R.G. 1998. Cosmogenic Chlorine-36 Production in Calcite by Muons. Geochimica and Cosmochimica Acta, 62, 433-454.

- Stone, J.O. 2000. Air pressure and cosmogenic isotope production. J Geophys Res 105, 23753–23759.

- Phillips, W.M. , Hall, A.M., Mottram, R., Fifield, K.L., Sugden, D.E. 2001. Cosmogenic 10Be and 26Al exposure ages of tors and erratics, Cairngorm Mountains, Scotland: Timescales for the development of a classic landscape of selective linear glacial erosion. Geomorphology, 73-222-245.

- Zerathe, S. , Lebourg, T., Braucher, R., Bourlès, D. 2014. Mid-Holocene cluster of large-scale landslides revealed in the Southwestern Alps by 36Cl dating. Insight on an Alpine-scale landslide activity. Quaternary Science Reviews, 90, 106-127.

- Arnold, M. , Merchel, S., Bourlès, D. L., Braucher, R., Benedetti, L., Finkel, R. C., Aumaître, G., Gottdang, A. and Klein M. 2010. The French accelerator mass spectrometry facility ASTER: Improved performance and developments. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research B, 268, 1954– 1959.

- Schimmelpfennig, I. , Benedetti, L, Finkel, R., Pik, R., Blard, P.H., Bourlès, D., Burnard, .P, Williams A. 2009. Sources of in situ 36Cl in basaltic rocks. Implications for calibration of production rates. Quat Geochronol. 4, 441–461.

- Braucher, R. , Merchel, S., Borgomano, J., Bourlès, D.L. 2011. Production of cosmogenic radionuclides at great depth: a multi element approach. Earth Planet Sci Lett, 309, 1–9.

- Ying-kui, L. 2018. Determining topographic shielding from digital elevation models for cosmogenic nuclide analysis: a GIS model for discrete sample sites. Journal of Mountain Science, 15, 939-947.

- Cardinal, T. , Audin, l., Rolland, y., Schwartz, S., Petit, C. Zerathe, S., Borgniet, L., Braucher, R., Nomade, J., Dumont, T., Guillou, V., ASTER Team. 2021. Interplay of fluvial incision and rockfalls in shaping periglacial mountain gorges. Geomorphology, 381: 107665.

- Cardinal, T. , Rolland, Y., Petit, C., Audin, L., Zerathe, S., Schwartz, S., and the ASTER Team: Fluvial bedrock gorges as markers for Late-Quaternary tectonic and climatic forcing in the French Southwestern Alps. Geomorphology, 418: 108476.

- Lenart, J. , Kašing, M., Pánek, T., Braucher, R., Kuda, F. 2023. Rare, slow but impressive: > 43 ka of rockslide in river canyon incising crystalline rocks of the eastern Bohemian Massif. Landslides, 20, 1705-1718.

| Sample | Lat. | Long. | Elev. | 36Cl | 35Cl | %Ca | Topo | Min age (no denudation) | Max. denud. | Denudation of ref sample | Exposure age |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (m a.s.l.) | (at/g) | (ppm) | Shielding | (ka) | (m/Ma) | (ka) | |||||

| SK01 | 38.25776969 | 20.47303338 | 404 | 735717 ± 33685 | 2 | 39.359 | 0.9956 | 25.32 ± 1.16 | 42.83 ± 1.96 | 40.00 | 236.42 ± 10.82 |

| SK02 | 38.25797481 | 20.47255184 | 389 | 715670 ± 32515 | 10 | 40.090 | 0.9898 | 21.26 ± 0.97 | 49.59 ± 2.25 | 40.00 | 105.37 ± 4.79 |

| SK03 | 38.25796523 | 20.47242618 | 386 | 549114 ± 25545 | 8 | 40.139 | 0.9888 | 16.53 ± 0.77 | 65.66 ± 3.05 | 40.00 | 39.23 ± 1.83 |

| SK04 | 38.2578831 | 20.47219818 | 378 | 741515 ± 81627 | 44 | 40.784 | 0.9880 | 24.95 ± 2.75 | 46.58 ± 5.13 | 40.00 | 151.68 ± 16.7 |

| SK05 | 38.2577646 | 20.47190186 | 371 | 738992 ± 33517 | 29 | 40.022 | 0.9885 | 22.87 ± 1.04 | 47.72 ± 2.16 | 40.00 | 128.44 ± 5.83 |

| SK06 | 38.25780925 | 20.47181009 | 367 | 576172 ± 26005 | 42 | 39.722 | 0.9887 | 20.21 ± 0.91 | 59.19 ± 2.67 | 40.00 | 60.77 ± 2.74 |

| SK07 | 38.25786209 | 20.47153539 | 358 | 513814 ± 22757 | 22 | 39.825 | 0.9893 | 18.67 ± 0.82 | 63.78 ± 2.82 | 40.00 | 49.35 ± 2.19 |

| SK08 | 38.25771697 | 20.47133071 | 351 | 658402 ± 29933 | 20 | 40.013 | 0.9881 | 22.93 ± 1.04 | 49.45 ± 2.25 | 40.00 | 116.9 ± 5.31 |

| FK01 | 38.25771697 | 20.47133071 | 366 | 306710 ± 18086 | 103 | 25.111 | 0.9813 | 13.61 ± 0.80 | 95.59 ± 5.64 | 95.59 | 5.23 ± 0.31 |

| FK02 | 38.25409336 | 20.47319708 | 366 | 295629 ± 16159 | 89 | 26.075 | 0.9813 | 12.86 ± 0.70 | 99.51 ± 5.44 | 95.59 | 4.89 ± 0.27 |

| FK03 | 38.25409336 | 20.47319708 | 366 | 265267 ± 15606 | 94 | 24.765 | 0.9813 | 12.18 ± 0.72 | 107.67 ± 6.33 | 95.59 | 4.28. ± 0.25 |

| FK04 | 38.25409336 | 20.47319708 | 366 | 268455 ± 16396 | 94 | 25.808 | 0.9813 | 11.50 ± 0.70 | 111.76 ± 6.83 | 95.59 | 4.39 ± 0.27 |

| FK05 | 38.25409336 | 20.47319708 | 366 | 262391 ± 14733 | 92 | 25.833 | 0.9813 | 11.22 ± 0.63 | 114.86 ± 6.45 | 95.59 | 4.77 ± 0.27 |

| FK06 | 38.25409336 | 20.47319708 | 366 | 260559 ± 18793 | 101 | 25.257 | 0.9813 | 11.06 ± 0.80 | 117.36 ± 8.46 | 95.59 | 5.05 ± 0.36 |

| FK07 | 38.25409336 | 20.47319708 | 366 | 222756 ± 14504 | 81 | 26.201 | 0.9813 | 9.07 ± 0.59 | 137.30 ± 8.94 | 95.59 | 3.11 ± 0.20 |

| FK08 | 38.25409336 | 20.47319708 | 366 | 238940 ± 13327 | 77 | 27.776 | 0.9813 | 9.21 ± 0.51 | 133.18 ± 7.43 | 95.59 | 4.09 ± 0.23 |

| Z01 | 38.30197617 | 20.46523406 | 216 | 363183 ± 16172 | 11 | 39.757 | 0.9683 | 12.38 ± 0.55 | 91.75 ± 4.09 | 50.00 | 25.64 ± 1.14 |

| Z01A | 38.30197617 | 20.46523406 | 224 | 160642 ± 8258 | 17 | 39.809 | 0.9673 | 5.43 ± 0.28 | 219.29 ± 11.27 | *5.43 ± 0.28 | |

| Z01B | 38.30197617 | 20.46523406 | 224 | 156448 ± 7919 | 17 | 39.717 | 0.9673 | 6.41 ± 0.33 | 202.96 ± 10.27 | *6.41 ± 0.33 | |

| Z02 | 38.30195767 | 20.46513126 | 218 | 355935 ± 16680 | 32 | 39.818 | 0.9703 | 14.16 ± 0.66 | 88.68 ± 4.16 | 50.00 | 31.94 ± 1.50 |

| Z02B | 38.30195767 | 20.46513126 | 230 | 135209 ± 9677 | 21 | 39.784 | 0.9657 | 8.72 ± 0.62 | 194.58 ± 13.93 | 50.00 | 11.79 ± 0.84 |

| Z02B2 | 38.30195767 | 20.46513126 | 230 | 109344 ± 6505 | 21 | 39.800 | 0.9657 | 4.16 ± 0.25 | 307.60 ± 18.30 | *4.16 ± 0.25 | |

| Z03 | 38.30197528 | 20.46503964 | 233 | 293212 ± 13239 | 14 | 39.934 | 0.9622 | 10.99 ± 0.50 | 110.13 ± 4.97 | 50.00 | 19.28 ± 0.87 |

| Z04 | 38.3020292 | 20.46500493 | 237 | 630575 ± 28345 | 28 | 39.774 | 0.9616 | 21.61 ± 0.97 | 51.65 ± 2.32 | 50.00 | 265.26 ± 11.92 |

| Z05 | 38.30205592 | 20.46493612 | 238 | 341582 ± 15298 | 24 | 39.791 | 0.9608 | 13.61 ± 0.61 | 91.90 ± 4.12 | 50.00 | 29.49 ± 1.32 |

| Z06 | 38.3020915 | 20.46483292 | 244 | 628376 ± 28353 | 27 | 39.911 | 0.9580 | 23.51 ± 1.06 | 49.16 ± 2.22 | 50.00 | Steady state |

| Z07 | 38.30225304 | 20.46468306 | 252 | 522870 ± 23515 | 26 | 39.034 | 0.9567 | 23.86 ± 1.07 | 52.63 ± 2.37 | 50.00 | 237.16 ± 10.67 |

| Z08 | 38.30208123 | 20.46455852 | 255 | 535861 ± 25708 | 15 | 39.508 | 0.9614 | 24.38 ± 1.17 | 50.70 ± 2.43 | 50.00 | 359.11 ± 17.23 |

| Z09A | 38.30207029 | 20.46413543 | 282 | 775022 ± 35348 | 27 | 39.855 | 0.9591 | 34.18 ± 1.56 | 34.83 ± 1.59 | 34.83 | Steady state |

| Z09B | 38.30192604 | 20.46412506 | 281 | 428512 ± 19142 | 13 | 40.040 | 0.5000 | 32.23 ± 1.44 | 51.37 ± 2.29 | 34.83 | 1.43 ± 0.64 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).