Introduction and Background

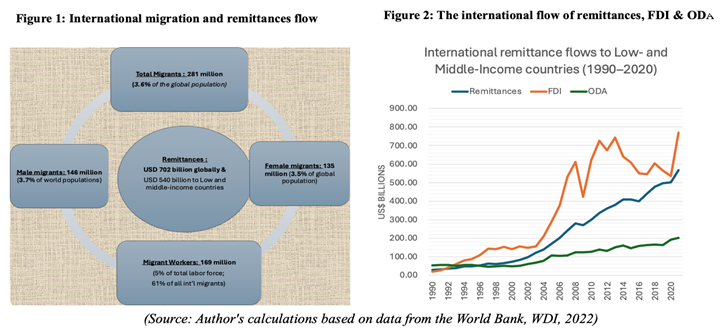

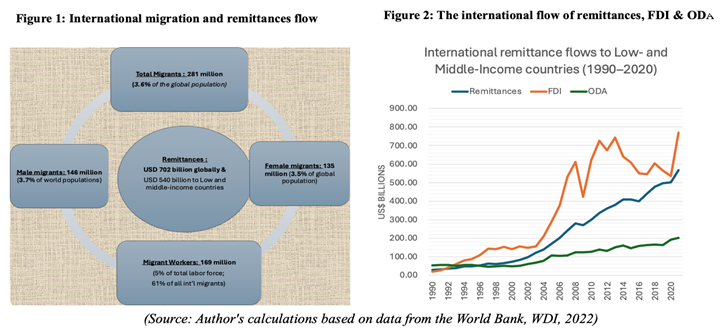

International migration from Low—and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs) has steadily increased for decades, positioning Migration and Development (M&D) as a global, regional, and national priority agenda. The number increased from 93 million in 1960 to 170 million in 2000 to 281 million in 2020, comprising about 3.6% of the global population (IOM, 2022). Notably, almost 75% of these international migrants and 70% of total migrant workers originate from LMICs, making these regions both the primary source of migrants and the leading destination of remittance flows. Aspirations to migrate abroad are increasing at an alarming rate. The Gallup World Poll surveys (2017) revealed that about 750 million people, or 15 percent of the world’s population, would move permanently to another country if given the opportunity.

Departures of migrants have considerable consequences for the communities of origin. As shown in Figure 2 above, the total global remittances flow was USD 702 billion in 2020, of which LMICs received USD 540 billion, which far exceeded Official Development Assistance (ODA) by nearly three times and has approached the value of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). In some countries, remittances exceeded 50% of GDP. These remittances are widely considered to be the most direct and measurable link between migration and development (IOM Report, 2024). They can provide funding for economic development in the form of increased investment in human capital or relaxed credit constraints for further physical capital accumulation (Benhamou & Cassin, 2021). They have also been an important source for improving the quality of life in origin societies.

One might argue that migration and remittances have become double-edged swords, particularly for LMICs. On the one hand, they offer individuals opportunities for better employment, education, and improved living standards at home and abroad. Conversely, under unfavorable circumstances, however, the departure of people can also further undermine prospects for growth and change in the remittance-dependent and migrant-obsessed communities’ (Haas, Castles, & Miller, 2019, p. 5). Once migration becomes strongly associated with success, migrating can give rise to a culture of migration in which migration becomes the norm, and staying home is associated with failure (De Haas, 1998; Massey et al., 1993). The IOM Report (2024) alerts that heavy reliance on remittances may foster a culture of dependency, reduce labor force participation, and slow economic growth. Such trends, pervasive in many LMICs, demand careful analysis and measures to address their underlying causes and implications.

People, their families, and communities weigh the costs and benefits of migration, and based on the results, they decide whether or not to move (Hanlon & Vicino, 2014, p. 153). However, migration decisions are complex and often influenced by myriad factors at the origin. In general, it is expected that the decision to migrate or not should be an individual’s option rather than a necessity. However, the reality is quite the opposite. Migration from developed and affluent countries is primarily voluntary, a willful choice, whereas migration from less developed countries is often driven by necessity. In the meantime, migration is often negatively connotated and deeply affected by misinformation and politicization (IOM Report, 2024). Amidst this milieu, will the socioeconomic development in LMICs contribute to a positive net migration? How can we accurately measure this influence? How can we transform migration from a necessity into a matter of choice for individuals? These questions are crucial for shaping future migration policies in migrant-origin countries. Understanding these dynamics and addressing the associated challenges necessitate a nuanced and comprehensive approach. In this regard, employing the analytical lenses of Migration Transition Theory (De Haas, 2010b; Skeldon, 1997; Zelinsky, 1971) and the Aspirations-Capabilities(A-C) Framework (Carling, 2002; de Haas, 2014; De Haas, 2021) can better understand migration processes in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).

The existing literature on migration transitions and capabilities reveals mixed and sometimes conflicting findings. While there is growing interest in the relationship between migration and development, empirical and comparative studies on the influence of domestic socioeconomic factors—such as GDPpc and the Human Development Index (HDI on migration transition and capability dimension remains inadequate. Most of these studies do not explicitly test the degree to which changes in domestic socioeconomic development influence migration transitions. Such comparison can yield additional insights into the migration and development policies. In addition, most prior studies have used emigration rates and migration stock as dependent variables. However, it can be argued that Net Migration Rates (NMR) could provide a more accurate measure for determining migration transitions and equilibrium. The socioeconomic conditions are proxied by GDP per capita and HDI of the sample countries.

To address these limitations, this study examines how the level of domestic socioeconomic development interacts with the migration transition and aspiration-capability frameworks. Panel data from a cohort of 109 low- and middle-income countries, spanning the period from 2002 to 2018 are utilzed. It employs dynamic panel regression using the two-step system Generalized Method of Moments (GMM), complemented by Quantitative Descriptive Analysis (QDA), to build on previous findings and provide fresh insights into migration and mobility. The research aims to answer five major questions: (1) To what extent and in what ways do domestic socioeconomic development levels shape migration decisions in LMICs? (2) How do these effects vary across different socioeconomic levels? (3) At what level of socioeconomic development do LMICs experience or fail to experience migration equilibrium and transitions when measured by emigration and net migration rates separately? (4) How do the migrants’ socioeconomic capabilities influence their migration decisions in LMICs? (5) What types of migration policies should migrant-sending countries adopt to transform migration from a necessity into a matter of individual choice?

The dynamic panel regression results show that both GDP per capita, with HDI having a significantly greater impact-approximately 10.69 times that of GDP per capita. Coefficients for HDI range from 9.144 to 13.79, while those for GDP per capita range from 0.994 to 1.785. The QDA results also suggest that migration equilibrium is reached at approximately $4,000 GDP per capita, based on emigration rates, and at around $7,000 when measured by net migration rates. Additionally, countries with GDPpc between $2,000 and $4,000 experience sharp negative net migration, indicating a highly mobile population in this income range. Finally, the regression results question the theoretical assumption of non-linearity, revealing almost a linear relationship between development and migration.

Considering the results, migration from low—and middle-income countries will continue for the foreseeable future. So, governments should move beyond restrictive migration policies and instead focus on enhancing socio-economic development domestically. Specifically, improving HDI could be an effective strategy for transforming migration from a necessity into a choice for individuals in LMICs.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 reviews the relevant literature and highlights the significance of the study;

Section 3 outlines the data sources, variable selection, methodology, and estimation strategy;

Section 4 presents the estimation results and provides an in-depth discussion; and, finally,

Section 5 concludes the paper and offers policy recommendations.

2. Review of Literature and the Study Significance

2.1. Theoretical Perspective on Migration and Development

People migrate for various reasons, whether voluntary or involuntary, internally or internationally, across different times and spaces. Scholars have proposed several theories to understand these migration patterns and behavior. Previous studies highlight that no single theory thoroughly explains international migration. Bailey (2001) and De Haas (2021) note that migration studies have remained an under-theorized field of social inquiry, whereas Massey et al. (1993) argues that existing models are outdated and fail to capture migration’s complex and dynamic nature.

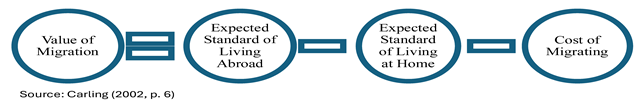

Conventional wisdom holds that income and development differentials mainly drive international migration (De Haas, 2010a). Ravenstein (1885) argued that development and migration are substitutes and that an inversely proportional relationship exists between income and other opportunity differentials and migration rates. This perspective, in which people are expected to move from low-income to high-income areas, has remained dominant in migration studies. Later on, the push-pull framework of migration Lee (1966) viewed income differences between countries as a prime emigration driver. Building on the earlier perspectives, the Neo-classical Migration theory (Harris, J. R. & Todaro, 1970; Todaro, 1969) explained migration as a function of geographical differences in the relative scarcity of labor and capital. Within this perspective, individual migration decisions are made by rational actors guided by comparing the present discounted value of lifetime earnings in alternative geographic locations, with migration occurring when there is a good chance of recouping human capital investments. The fundamental assumption of the neoclassical model can be illustrated below. The model predicts that migration will occur when the value of migration is positive.

Conceptual Framework for the Value of Migration

However, push-pull and neo-classical models are criticized for being too simplistic and unable to describe empirical patterns related to migration (e.g., de Haas, 2021; Clemens, 2022). The New Economics of Labor Migration (NELM) theory argues instead that the household or family unit is the more appropriate level of analysis. People decide collectively not just to maximize total income but to minimize the risk to family income due to market failure, unemployment, or a shortfall in productivity, such as a failed harvest (Kolbe, 2021, p. 26). The Dual Labor Market Theory links migration to the structural demand for foreign labor in industrial economies. The Dependency and World System System theory suggests that capitalist expansion drives migration from the periphery to the core regions. In contrast, the Cumulative Causation Theory and Network Theory of migration emphasize the self-reinforcing nature of migration through social networks and feedback loops. While briefly referencing other theories to provide the study’s background, we primarily focus on two emerging migration theories: the Migration Transition Theory and the Aspirations-Capabilities (A-C) Framework.

2.2.1. Migration Transition Theories

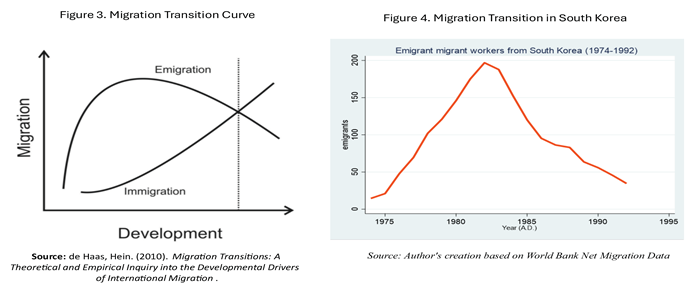

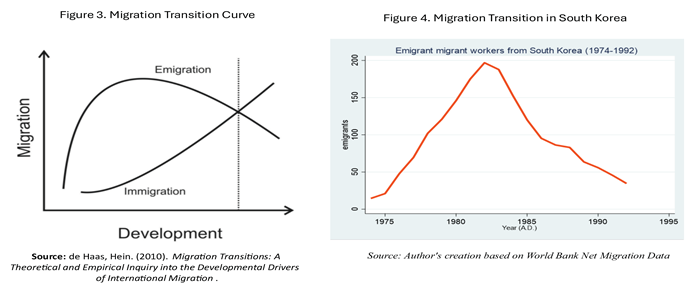

Zelinsky (1971) hypothesized an inverted U-shaped relationship between emigration and development (Figure 3, below), which he termed the mobility transition. De Haas (2010b) further elaborated this concept, arguing that migration is integral to broader development and social transformation linked to modernization and industrialization. Migration transition theory posits that migration levels initially increase as development progresses but later stabilize. The following figures illustrate the dynamics of migration transition.

South Korea’s experience (Figure 4 above) is a model for understanding migration transitions in other developing nations. It illustrates how emigration tends to peak during a critical stage of development before gradually declining as prosperity increases

2.2.2. Migration Aspirations and Capabilities (A-C) Framework

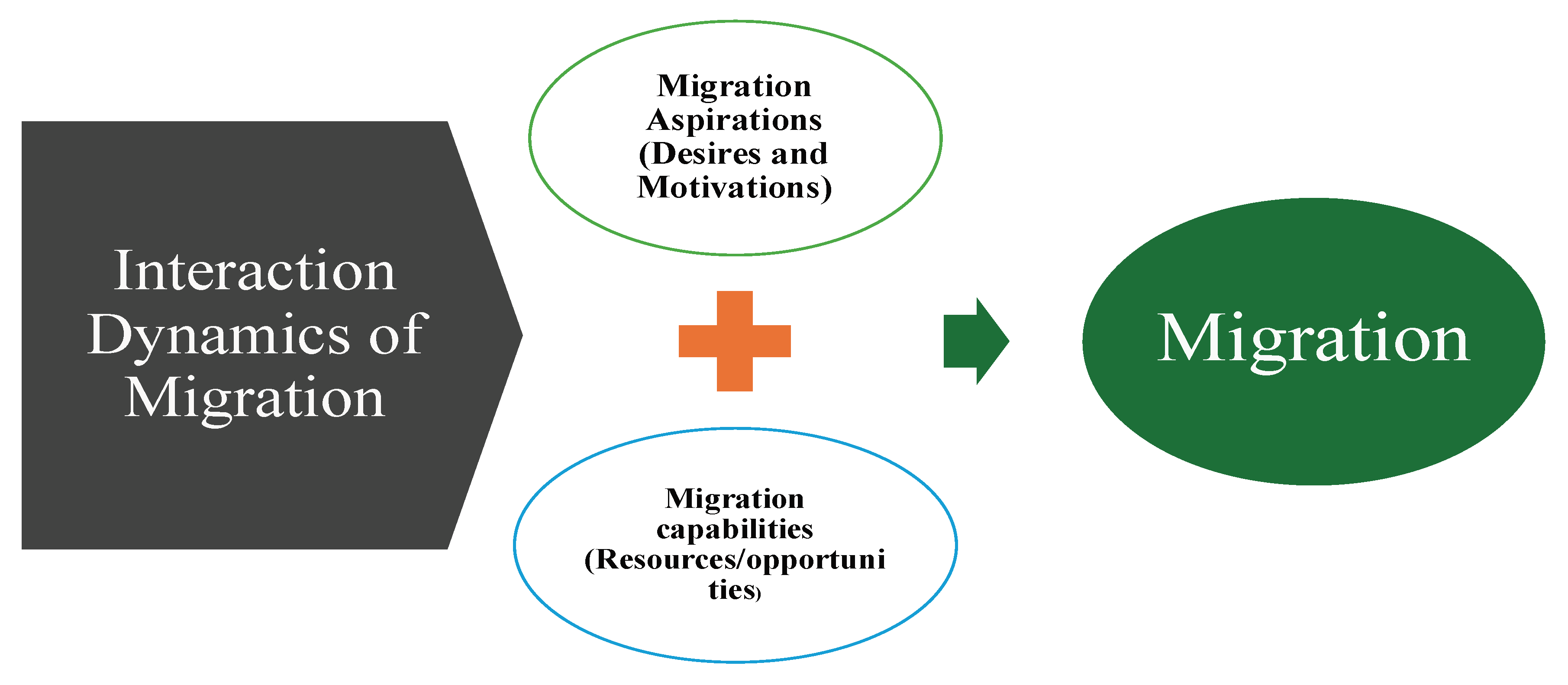

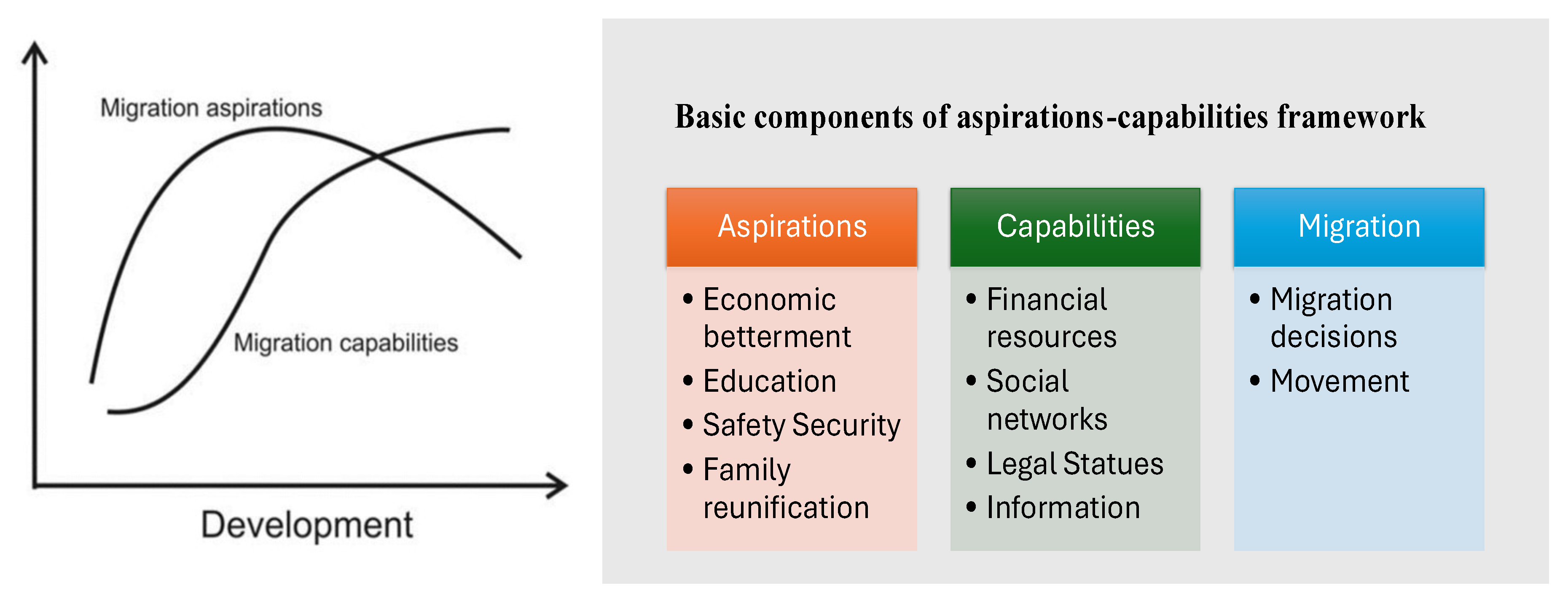

Conventional migration theories, such as push-pull models (Lee, 1966) and Neo-Classical Theories (Harris, J. R. & Todaro, 1970), argue that migration is primarily motivated by income, employment, and regional opportunity disparities. Migration transition theory (as explained above) views migration as integral to broader development and social transformation processes linked to modernization and industrialization. However, a paradox exists: socioeconomic development in impoverished societies often initially spurs migration. Those theories can only partially explain why only 3.6% of the global population migrates, while 96.4% remain in their home countries despite widening geographical disparities. Alongside why people migrate, why people choose not to migrate has also received growing attention in migration studies. Amidst this paradox, Carling (2002) introduced the concept of ‘Involuntary Immobility’- the desire to migrate without means- especially in poor countries. He argued that insights into migration and development can be gained by analyzing aspirations (the desire to migrate) and migration capabilities (the actual ability to do so). This framework helps explain why not all people who aspire to migrate can do so.

Figure 5.

Migration as an Outcome of Aspirations and Capabilities. Source: Created by Author based on (De Haas, 2021).

Figure 5.

Migration as an Outcome of Aspirations and Capabilities. Source: Created by Author based on (De Haas, 2021).

Later on, De Haas (2021) integrated this concept into the Aspirations-Capabilities (A-C) framework and argued that migration decisions are shaped by people’s aspirations to improve their lives and their migration capabilities, which are influenced by broader social, economic, and political factors. For him, migration is not simply driven by poverty but rather by relative deprivation, where individuals with rising aspirations may seek migration to fulfill their potential, provided they have the resources and opportunities to do so. Thus, the Aspirations-Capabilities framework explains migration decisions by considering individuals’ desires and motivations (aspirations) alongside their resources and opportunities (capabilities). As long as aspirations grow faster than local opportunities can offer, it is likely that people’s aspirations to migrate will increase. The framework indicates that migration is the combined result of two factors: (1) the aspiration to migrate and (2) the ability to migrate, which can be shown in the following two figures:

Figure 6.

Hypothetical Effects of Development on Migration Aspirations and Capabilities (Source: de Haas (2010c).

Figure 6.

Hypothetical Effects of Development on Migration Aspirations and Capabilities (Source: de Haas (2010c).

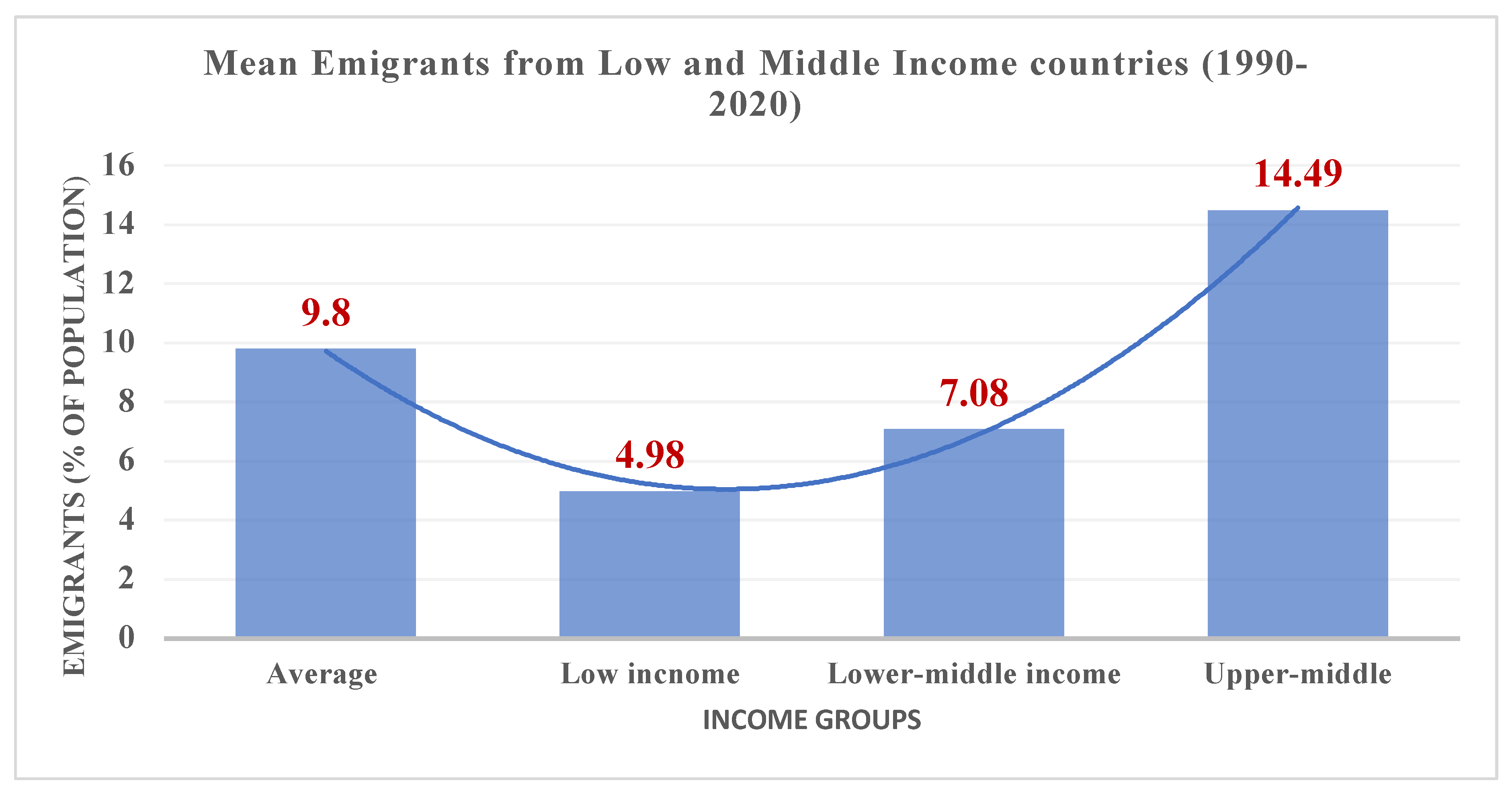

Figure 4. Mean Emigrants from Low and Middle Income countries (1990-2020)

Source: Author’s creation using data from 107 LMICs (1990–2020).

Aligning with the A-C framework,

Figure 7 above illustrates how low income restricts individuals’ capability to migrate internationally. Meanwhile, the average emigration rate across all samples was 9.8%, which decreased to its lowest point of 4.98% in low-income countries. Such a trend indicates the capability constraints of individuals to migrate within the A-C framework. It increases to 7.08% in lower-middle-income countries and 14.49% in upper-middle-income countries.

Figure 7.

Income Level and Migration Capabilities.

Figure 7.

Income Level and Migration Capabilities.

2.2. Literature on Factors Influencing Migration Decisions

Miller (1973) argued that out-migration decreases in regions with high wages, rapid employment growth, and mild winters but increases in areas with high unemployment rates. He highlighted the economic factors, particularly employment growth, as the main determinants of migration, demonstrating an inverse relationship between wages and out-migration rates. However, his study is context-specific, focusing solely on out-migration from the continental United States and the District of Columbia, and lacks a comparative analysis across different settings. Simpson (2022) studied migration’s demographic and economic determinants, including push and pull factors influencing the decision to stay or move, and identified income differentials, migrant networks, and demographic factors as robust predictors of migrant flows.

Schlottmann & Herzog (1982) challenged the notion that out-migration is unaffected by local economic conditions, revealing a significant impact of economic factors on interstate migration. However, this analysis was limited to the U.S. labor force. Similarly, Jennissen (2003) investigated the economic determinants of net international migration in Western Europe from 1960 to 1998 and found a positive correlation between GDPpc and international migration, while employment levels were negatively associated with migration. Jennissen’s research primarily focuses on destination countries within a European context. Likewise, Lucas (2006) concluded that gaps in earnings opportunities and employment probabilities play a significant role in shaping the migration streams.

Migration scholars, such as Borjas (1989) acknowledged that individuals migrate across borders in response to labor demand and supply differences, moving from regions with lower wages and abundant labor to those with scarce labor and higher wages. The scholars including De Haas (2011); Feld (2021); Hagen-Zanker (2008); Harris (2005); Maimbo & Ratha (2005); Douglas S. Massey (1999); Postel-Vinay & Domingues Dos Santos (2003) have primarily focused on the impacts of migration on destination countries, commonly referred to as the ‘receiving-country bias (De Haas, 2021).’ Similarly, studies focusing on origin countries primarily emphasize the impact of migration and remittances on different aspects of socioeconomic development. Scholars such as Maimbo & Ratha (2005), Özden & Schiff (2006); Pan & Sun (2024); Postel-Vinay & Domingues Dos Santos (2003); Harris & Todaro (1970); and Wahba (2021) have assessed the impacts of migration and remittances on various aspects of socioeconomic life in migrant-origin countries. However, these studies primarily focus on the impact of migration on development, while the influence of development on migration trends receives less attention.

In a study of the migration-development nexus in LMICs, de Haas & Rodríguez (2010) argued that migration has always been an intrinsic part of a broader development process, social transformation, and globalization rather than a ‘problem to be solved.’ Similarly, analyzing Morocco’s experience using a ‘transitional’ perspective on migration, De Haas (2007) claimed that migration results from development rather than a lack of it. He further predicted that in the long term, out-migration might decrease, and Morocco could become a destination for migrants from sub-Saharan Africa. Similarly, Haas, Castles, & Miller (2019) argued that migration positively impacts overall growth, innovation, and the vitality of economies and societies. A study by Nikolova (2023) sheds light on how countries’ economic development levels influence the relationship between inequality and potential emigration. The study found that rising inequality is negatively associated with emigration intentions in low—and middle-income countries. Conversely, in affluent nations, heightened inequality stimulates greater desires to emigrate, particularly among high-income and highly educated individuals. In another study, Giang, Nguyen, & Nguyen (2020) found that people tend to move from low-income provinces to high-income ones. However, this study was limited to inter-province migration in Vietnam.

2.3. Literature on Migration Transitions

Despite the extensive theoretical discussion across migration literature, there are few empirical studies on migration transition and equilibrium. In a pioneering study, De Haas (2010a) estimated the impact of development indicators on long-term migration patterns globally. He analyzed the relationship between development variables such as GDP per capita, Literacy, and the HDI with immigration and emigration levels. He showed that higher economic and HDI levels are linked to increased overall migration, with an inverted U-curve effect on emigration. He estimated that emigrant stocks tend to peak at GDPpc levels of approximately $12,000 (2005 levels) and HDI levels of approximately 0.8, after which they decline slowly. Similarly, in a seminal research paper, Clemens (2020) examined the relationship between GDPpc and Net Emigration rates in developing countries. The results show the existence of the emigration cycle, not only across but within typical developing countries. He finds that emigration rises on average as GDPpc initially rises in poor countries, slowing after roughly US $5,000 at PPP value and reversing after roughly $10,000. However, this study also focuses on emigration rates, which may not fully capture the broad spectrum of migration trends and patterns.

Dao, Docquier, Parsons, & Peri (2018) shed light on the role of both microeconomic drivers (i.e., financial incentives and constraints) and macroeconomic drivers, as well as the skill composition of the population. Using the double decomposition model, they further distinguished between migration aspirations and realization rates by education level. Overall, they provide consistent evidence that the role of financial constraints, while relevant for the poorest countries, is limited. Instead, a significant fraction of the increasing segment is explained by the skill composition and macroeconomic drivers (i.e., by factors that do not change in the short run). The latter effect is significant in countries where GDPpc in PPP value is between $1500 and$6000. They argue that migration increases with development because the proportion of college graduates increases, and this group has the highest propensity to emigrate abroad. Their concluding results suggest that a rise in income may increase college graduates’ and average emigration rates in the long run. This paves the way for testing further the influence of human development factors like GDPpc and HDI on migration equilibrium and transition.

Likewise, Bencek & Schneiderheinze (2020) found a negative association between economic growth and emigration flows. They claimed that the highest average emigration rates are observed in countries with incomes between 7000 and 14,000 USD. However, this study focuses solely on emigration to OECD countries, overlooking broader trends as low-income migrants face barriers to OECD migration. Additionally, using fixed-effects methods in this study may pose endogeneity issues.

2.4. Literature on Aspirations-Capabilities Framework

Few empirical studies examine domestic socio-economic factors’ influence on migration aspirations and capabilities. In a seminal article, “Does Development Reduce Migration? Michael A. Clemens (2014) argues that economic development does not necessarily lead to reduced migration; it can generate more migration under certain conditions. Clemens challenges the conventional notion that poverty is the primary driver of migration and explores how economic opportunities, infrastructure development, education, and income inequality shape migration decisions. He further demonstrates that development can create pathways for people to migrate by improving mobility, expanding networks, and increasing individuals’ aspirations and capabilities to move. He emphasizes that migration is not a mere response to poverty but rather a complex outcome influenced by individual choice, structural opportunities, and global inequalities.

Similarly, De Haas (2010b) proposes to incorporate the notions of agency and individual aspirations into transition theory by conceptualizing migration at the microeconomic level as a function of aspirations (as characterized by an inverted U-shaped relationship) and capabilities (that increase monotonically with development). Countering the notion of ‘Development instead of migration policies’ of developed countries as a misguided idea, De Haas (2007) forecasted that in the poorest countries, especially the sub-Saharan African countries, which are the target of much international aid, any take-off development is likely to lead to accelerating take-off emigration for the coming decades, which is the opposite of what ‘development instead of migration’ policies implicitly or explicitly aim to achieve. This idea can also apply to other low-income countries.

In a seminal article, De Haas (2021) presents a comprehensive theoretical approach to understanding migration by integrating individual aspirations and structural capabilities. The article proposes the Aspirations-Capabilities (A-C) framework, emphasizing the interplay between individuals’ migration aspirations (desires to move) and their capabilities (resources and structural conditions enabling movement). Using a comparative analysis, he argues that migration is not merely a response to economic disparities but is shaped by broader factors, including social, political, and cultural contexts. He emphasizes the importance of agency in migration, defining human mobility as the capability to choose where to live, including the option to stay. He concludes that restrictive migration policies and border controls often fail to reduce migration; instead, they reshape it by pushing migrants toward riskier and irregular routes. This framework provides a nuanced perspective, challenging simplistic push-pull models and highlighting the need for policies that consider the complex dynamics of migration aspirations and capabilities. However, this is a theoretical elaboration rather than an empirical study to test migration aspirations and capabilities.

2.5. Literature Gaps and Expected Contribution

Building on the extensive review of previous studies, this section identifies the gaps in the literature and outlines the contributions this research aims to make. Most migration research emphasizes migration’s effects on development, often adopting a “receiving country bias” (De Haas, 2021). Notably, research on the impact of domestic socioeconomic factors on migration transitions and capabilities is insufficient and needs further investigation. This study focuses on the impact of domestic socioeconomic indicators, like GDPpc and HDI, on migration trends. Comparing the influences of variables such as GDPpc and HDI on migration patterns can offer new insights into policy formulation on migration management in LMICs. The existing literature has not adequately addressed this type of comparison.

While the migration-development nexus has been extensively explored in various contexts, empirical studies on migration transitions and capabilities remain limited. The existing literature presents mixed and conflicting findings with diverse perspectives and conclusions. For instance, De Haas (2010b) estimated that emigrant stocks tend to peak at GDPpc levels of approximately $12,000 (2005 levels) and HDI levels of approximately 0.8, after which they decline slowly. Likewise, Clemens (2020) reported slightly different findings, indicating that emigration rises on average as GDPpc initially rises in poor countries, slowing after roughly US $5,000 at purchasing power parity and reversing after roughly $10,000. Similarly, De Haas (2021) presents a comprehensive theoretical approach to understanding migration by integrating individual aspirations and structural capabilities. However, it is limited to theoretical explanations and does not include an empirical analysis.

Most previous scholars used emigration flows and stocks as explanatory variables to measure migration transition and equilibrium. However, emigration flows and stocks alone may not accurately reflect migration equilibrium, as high emigration can coincide with a high return of migrants, too, which might have been overlooked. It can be argued that net migration rates, which capture the balance between emigration and immigration, offer a more accurate measure of migration equilibrium and transitions. Several previous studies have highlighted that the Net Migration Rate (NMR) can accurately depict migration flows, making it an appropriate variable for measuring migration trends. Ravenstein (1885) argued that migration includes both the inflow and outflow of people, so understanding the impact requires considering the net migration. Castles & Miller (2009) emphasized the importance of recognizing not only the stock but also the flow of migrants when examining migration processes. Similarly, Hsing (1996) also chose the net migration rate as the dependent variable, believing bilateral migration can be analyzed simultaneously. Similarly, data on return migration in LMICs is limited, hindering the analysis of its effects on various socioeconomic dimensions. Net migration data can provide insights into return migration.

No significant studies have used the two-step system GMM model to examine how development levels influence migration trends. As highlighted by Arellano & Bover (1995); Blundell & Bond (2000) and; Roodman (2009)GMM addresses endogeneity, heteroscedasticity, omitted variable bias, and measurement errors in dynamic panel data, offering a novel approach for migration studies.

While many previous studies on migration and development are country—or region-specific, this study covers 109 low—and middle-income countries. This broad coverage enhances the generalizability of the results for policy formulation and implementation on migration management.

3. Methodology and Estimation Strategy

3.1. Data and Sources

The study primarily utilizes panel data from a cohort of 109 low- and middle-income countries, covering 2002 to 2018. The list of the countries is provided in Annex C. They were selected based on the World Bank’s income-level classification (2022) and data availability. Some countries with extreme net migration values were excluded to avoid skewed results without prejudice. A dataset covering 33 upper-middle-income countries from 1991 to 2018 (28 years) has also been prepared to examine the migration transition threshold through the QDA method.

According to the IOM (2022), LMICs are the primary sources of international migrants. Almost 75% of international migrants and 70% of total migrant workers originate from LMICs, making these regions both the primary source of migrants and the leading destination of remittance flows. Of the total global remittance flow of USD 702 billion in 2020, LMICs received USD 540 billion. This amount exceeded Official Development Assistance (ODA). It nearly matched these countries’ Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), proving them the largest and most reliable family income sources and foreign capital reserves for those economies. The World Bank (2022) statistics show that they are also the homes to 75% of the world’s population and 62% of the world’s poor.

According to De Haas (2010b), there are three empirical strategies for testing migration transition theory: the longitudinal approach elaborated by Hatton and Williamson (1998), the cross-sectional analysis of the links between levels of human development and migration levels as performed by Lucas (2004), and the global panel data, which is hardly available. However, global data on net migration are available to a certain extent. The panel data analysis investigates the development of variables over time (Mehmetoglu & Jakobsen, 2022, p. 272). This data type differs from time series in that the individual (or firm, organization, etc.) is the unit of analysis rather than the time points (ibid). Adams Jr (2011) argues that panel data, which includes repeated observations on the same household over two or more periods, is a good solution because by taking ‘first differences’ between various variables, it becomes possible to eliminate many of the biases that arise from endogeneity, selection, and omitted variables, including unobservable characteristics.

3.2. Variables and Selection Criteria:

The variables are chosen based on their relevance to understanding migration dynamics and their availability in the dataset. The Net Migration Rate (NMR) and Emigration Rate constitute the primary dependent variables of interest. NMR represents the net migration balance in LMICs of migrant origin. It is calculated as the difference between the number of immigrants and emigrants per 1,000 people(NMR= 1,000). Positive values indicate net immigration, while negative values reflect net emigration. The latter scenario is predominant in most LMICs, requiring the implementation of appropriate measures to address these issues.

Several previous studies highlighted that the NMR can accurately depict migration flows, making it an appropriate variable for measuring migration trends. Ravenstein (1885) argued that migration includes both the inflow and outflow of people, so understanding the impact requires considering the net migration. Castles & Miller (2009) emphasized the importance of recognizing not only the stock but also the flow of migrants when examining migration processes. Similarly, Hsing (1996) also chose the NMR as the dependent variable, believing bilateral migration can be analyzed simultaneously. To estimate the influence of economic determinants on net international migration in Western Europe during the period 1960–1998, Jennissen (2003) used NMR as the dependent variable. Jennissen further argued that the significant advantage of using NMR is the availability of long-time series data for almost all countries. Thus, we believe that net migration data can offer new insights into migration trends and patterns.

GDP per capita and the Human Development Index (HDI) are the primary explanatory variables proxied to a country’s socioeconomic development level. De Haas (2010b) and Jennissen (2003) also used GDPpc as an independent variable in studying migration transition and the economic determinants of net migration. The HDI measures average achievements in health, education, and standard of living, providing a broader measure of well-being and development than income alone. The HDI rankings are defined by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and are categorized into four levels based on the HDI score. The HDI scores are categorized into four distinct ranges based on levels of development. A “Very High” HDI corresponds to scores of 0.800 or above, while a “High” HDI ranges from 0.700 to 0.799. “Medium” HDI scores fall between 0.550 and 0.699, and “Low” HDI includes scores of 0.549 or below (UNDP, 2024).

Several control variables are included in estimation equations to account for factors that could influence the dependent variable, thereby isolating the effect of the primary independent variables of interest. In this context, variables such as GDP Growth (GDPGRO), Unemployment Rates (UNEMP), Gross Capital Formation (GCF), and Inflation (INFLATION) are deemed essential as they capture different dimensions of a country’s economic performance and development. These variables help mitigate biases arising from unobserved heterogeneity by controlling for underlying economic conditions that may confound the results. Additionally, governance and socio-political indicators like Corruption Control (Corrupt Ctrl), Rule of Law (RoL Index), Political Stability and Absence of Violence (Peace_Stab), Government Integrity (GovIntri) Government Effectiveness (Govt_effect), Civil Liberties(Civ_Liberty), Civic Participation (Civic_Part), and Economic Freedom (ECO FREEDOM) reflect the institutional quality and democratic processes that could impact the dependent variable. Other critical controls include technological and infrastructural variables, such as Internet Use (INTERNET), as well as demographic and health-related factors like Life Expectancy (LIFEEXP), Maternal Mortality Ratio (MMR), Fertility Rate (TFR), and Population Growth (POPGRO). By incorporating these controls, the model ensures a more precise estimation of the relationship between the independent and dependent variables, capturing the influence of these broader contextual factors.

The datasets are drawn from various reputable sources, including the World Development Indicators (WDI) published by the World Bank (2022), the Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) published by the World Bank (2022/2023), and the Migration Data Portal maintained by the International Organization for Migration (IOM). Additional sources include the Index of Economic Freedom (Heritage Foundation) and the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Dataset, produced by the V-Dem Institute at the University of Gothenburg. The table of variable descriptions is provided in

Appendix A.

3.3. Methodology and Estimation Strategy:

The study adopts the two-step system GMM (Generalized Method of Moments) model, a dynamic panel data estimator that incorporates the lagged dependent variable as one of the independent variables. As suggested by Arellano & Bover (1995); Blundell & Bond (2000) and; Roodman (2009), the GMM approach is well-suited for addressing potential issues in dynamic panel data models, such as endogeneity, heteroscedasticity, omitted variable bias, and measurement errors. GMM model is specifically designed for situations involving a lagged dependent variable, a small period (T), and a larger number of cross-sections, groups, or individuals (I), where T< I. It is suitable for instrumental variable (IV) estimation when the number of instruments (Z) is equal to or less than the number of individuals (I) and when the independent variables are not strictly exogenous. In GMM estimation, Hansen’s testing of overidentifying restrictions is used to test the null hypotheses of the overall validity of the instruments used. The p-value of Hansen testing should not be too high or too low (Roodman, 2009). The Arellano–Bond test for autocorrelation is employed to test the null hypothesis that the differenced error term is serially correlated in the first and second order, called AR (1) and AR (2), respectively. AR (2) should be insignificant (p-value > 0.05), implying that no second-order serial correlation exists.

The basic model for the analysis is constructed as follows:

Where, NMRit is the dependent variable, representing the Net Migration at time t for entity i. Domestic_Socioeconomic_Level it is a key explanatory variable, capturing the socioeconomic indicators at time t for entity i. Xit is a vector of additional control variables that may influence migration trends. ϵit: is the error term, accounting for unobserved factors at time t for entity i.

In the above context, the basic estimation equation is specified as follows:

Where Yit represents the dependent variables, i.e., NMR of the country i at year t, Yit-1 is one period lag of the dependent variable, Xit represents the explanatory variables such as GDPpc and HDI (used as a proxy for socio-economic development). Zit represents the vector of control variables, dt denotes the year dummy, and εit indicates the error term. The constant term is α, and β1, β2, and β3 are the coefficients of each explanatory variable, which are the parameters of interest. The detailed model specifications are provided in the Appendix.

The Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) measures how much the variance of a regression coefficient is inflated due to multicollinearity with other predictors in the model. A VIF of 1 means no correlation exists between the model’s predictor variable and the other predictor variables. VIF values between 1 and 5 suggest moderate correlation but generally not enough to warrant corrective measures. VIF values above 5 indicate high correlation and are a cause for concern, suggesting the presence of multicollinearity. In our model, the correlation metrics among the variables indicate no high correlation coefficients, suggesting a low risk of multicollinearity issues. In the tests, the VIF 1.57 and 1.2 are much closer to 1 than to 5, which suggests that multicollinearity is not a significant issue in these models.

4. Results and Discussion:

The study examines how domestic socioeconomic development influences individuals’ migration decisions, focusing on the migration transition and the aspirations-capabilities framework. Panel data from 109 low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) from 2000 to 2018 were analyzed, using the Human Development Index (HDI) and GDP per capita (GDPpc) as key explanatory variables. In total, 15 dynamic panel regressions employing a two-step system GMM model were conducted under varying conditions to assess the influence of GDPpc and HDI on net migration. These regression models facilitated comparisons of the respective impacts of GDPpc and HDI on net migration. Four Quantitative Descriptive Analyses (QDA) were initially conducted to highlight the significant migration trends and patterns and provide a foundation for further analysis and inference.

4.1. Insights from Quantitative Descriptive Analysis (QDA).

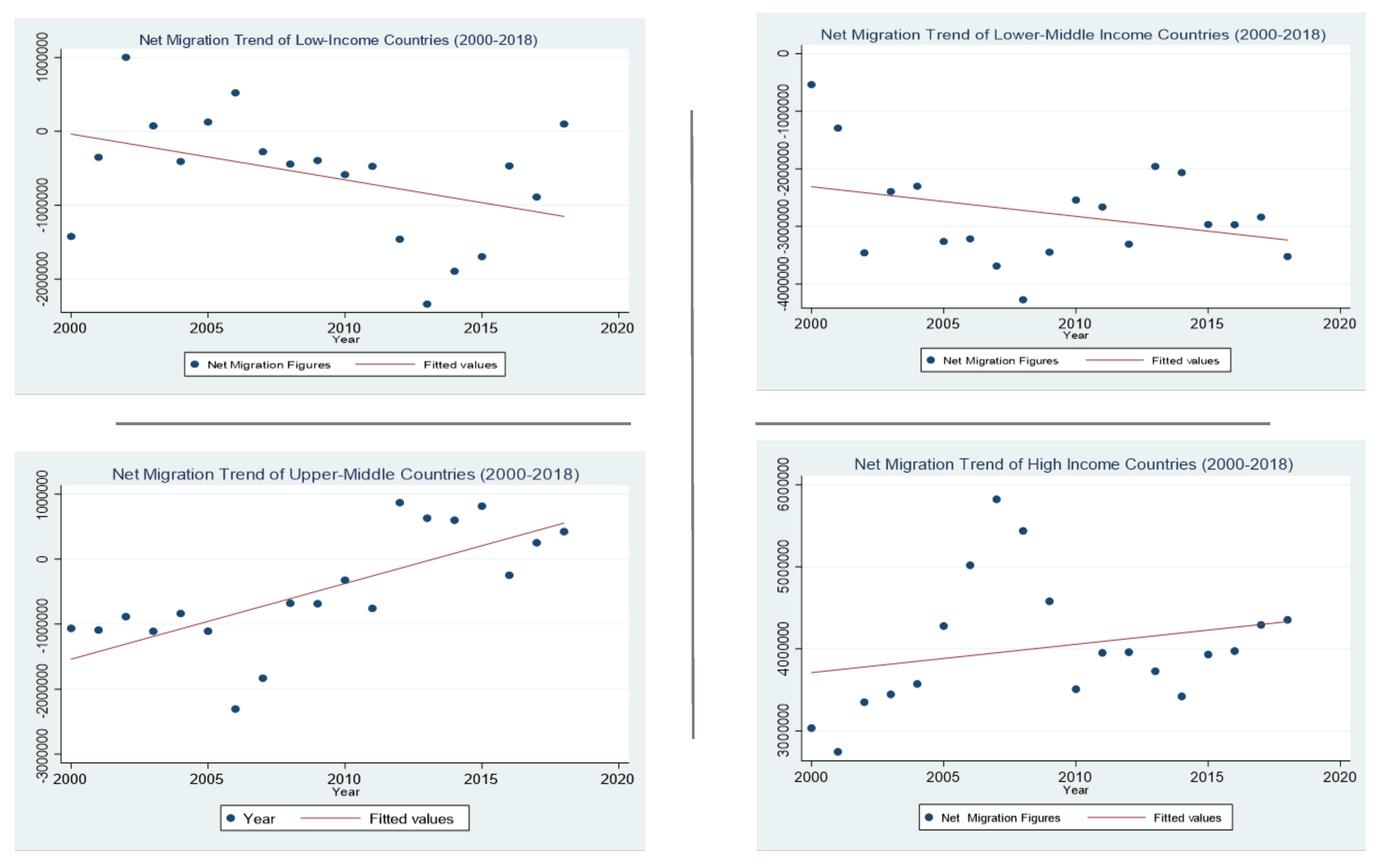

Figure 4 below illustrates the evolution of countries’ NMR across income groups (2000–2018) and highlights the points at which they experience or fail to experience migration equilibrium and transitions.

Figure 8.

Net Migration Trends by Income Groups (2000–2018). Source: Author’s computation.

Figure 8.

Net Migration Trends by Income Groups (2000–2018). Source: Author’s computation.

The graphs above underscore the nexus between development and migration, highlighting how income and developmental disparities significantly shape migration patterns and trends. Persistent out-migration was observed in low- and lower-middle-income countries over the study period, never reaching equilibrium. Even though these trends align with the conventional wisdom that differences in global wealth and human development are the primary drivers of international migration (Harris, J. R. & Todaro, 1970; Lee, 1966; Ravenstein, 1885), they also question the assumption of capability constraints, which suggests that limited resources in less developed countries impede emigration (Carling, 2020; De Haas, 2010b). Furthermore, the migration transition is observed to commence in the early stages of the upper-middle-income category, reaching equilibrium in its later stages and marking a critical shift from net emigration to net immigration. In contrast, high-income countries consistently demonstrate positive and increasing net migration trends throughout the study period. Similar patterns were highlighted in the studies by Clemens (2014) and De Haas (2010b).

In

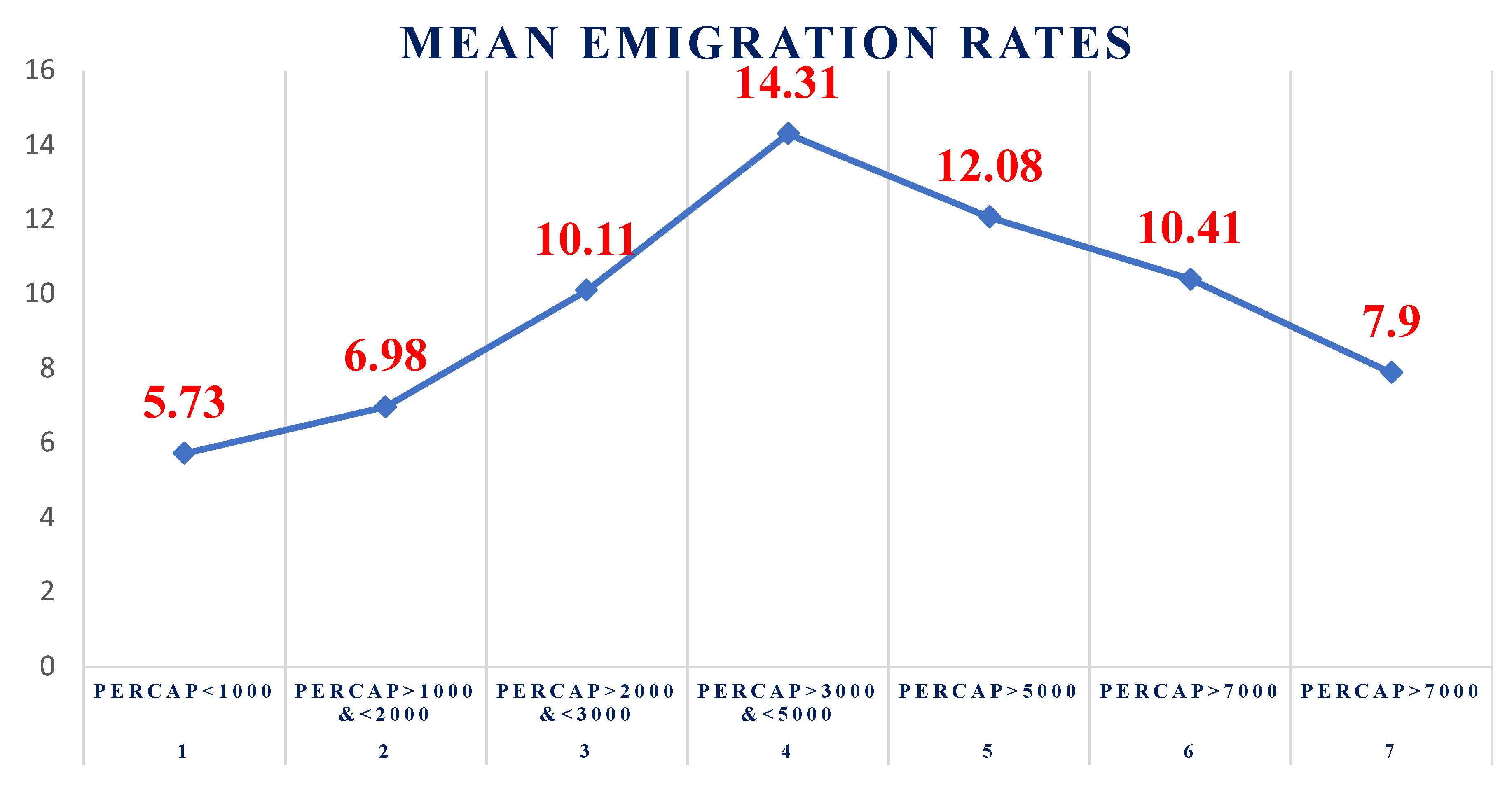

Figure 9 below, we aggregate the emigration data into eleven income categories to examine various migration transitions and capabilities scenarios based on different economic development levels.

Figure 9.

Influence of Income Level on Migration Transitions and Capabilities. Source: Author’s creation using data from 107 LMICs (1990–2020).

Figure 9.

Influence of Income Level on Migration Transitions and Capabilities. Source: Author’s creation using data from 107 LMICs (1990–2020).

The analysis of migration transitions across income brackets based on GDPpc reveals that emigration rates are relatively low (5.73%) in the low-income bracket (PERCAP < 1000). To some extent, this supports the assumption of capacity constraints on emigration (Carling, 2020). As income rises, emigration rates increase significantly, peaking at 14.31% when GDPpc reaches approximately $4000. This suggests that economic development in this state enhances people’s migration capabilities. Emigration rates decline as GDPpc rises, with 12.08% for GDPpc > $5,000 and 7.9% for GDPpc > $7,000. This decline reflects a migration transition because economic development reduces incentives to migrate abroad as domestic opportunities become more attractive. However, the observed peak at GDPpc of around $4,000 differs from earlier studies by Clemens (2014) and (De Haas, 2010b), which estimated the migration equilibrium at a GDPpc of approximately $7,000. While these results support the transition hypothesis that poverty initially impedes emigration, which then gradually rises with development before eventually declining as domestic opportunities improve, they suggest a slightly different equilibrium point at around $4,000, compared to what previous studies have indicated.

Figure 10.

Influence of Income Level on Migration Transitions and Capabilities. Source: Author’s creation using data from 107 LMICs (1990–2020).

Figure 10.

Influence of Income Level on Migration Transitions and Capabilities. Source: Author’s creation using data from 107 LMICs (1990–2020).

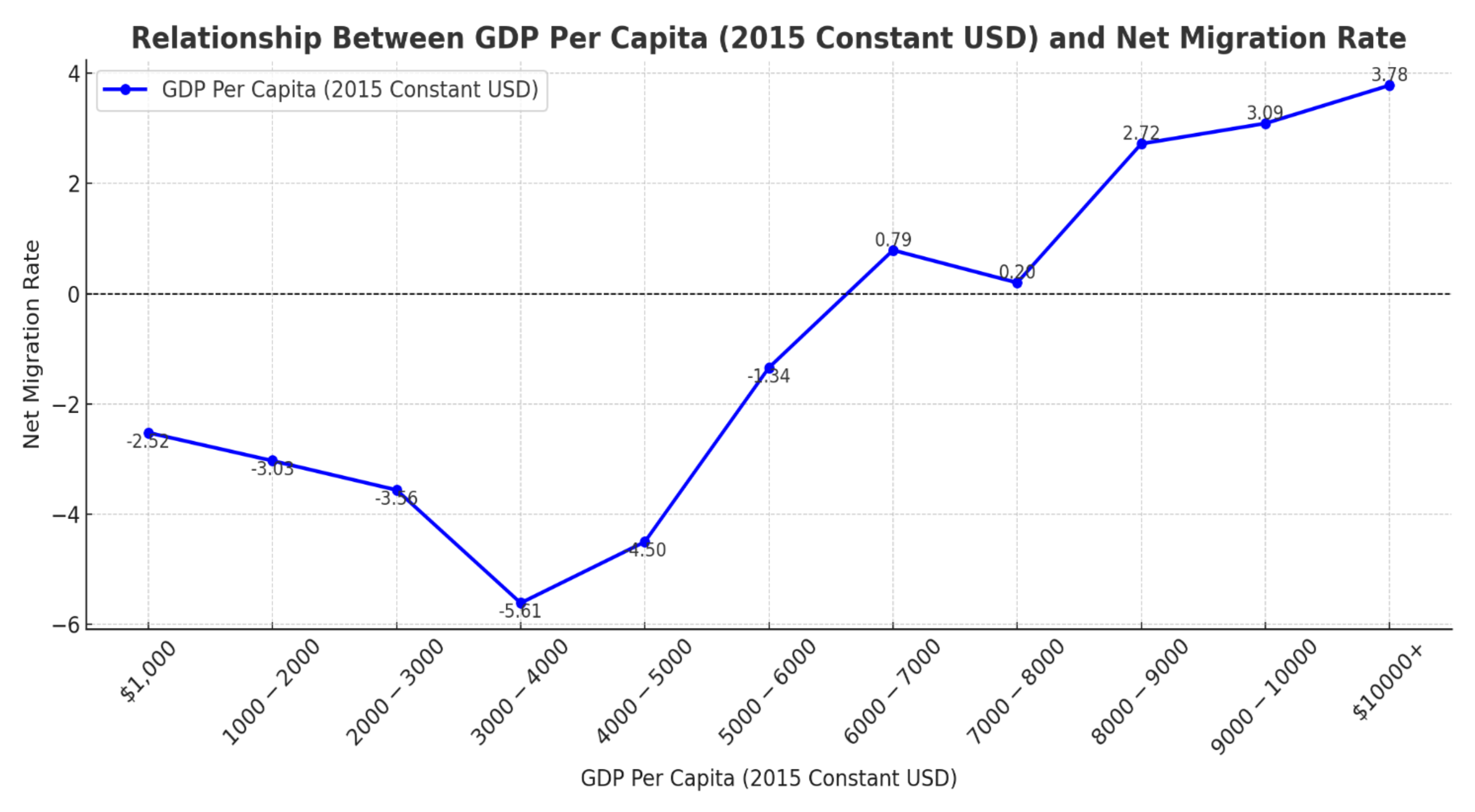

In another analysis (Figure) examining the relationship between GDPpc and the net migration rate (NMR) through the lens of migration transition and capabilities perspective, countries with GDPpc below $2,000 exhibit negative but nearly flat net migration trends. This pattern reflects the early stages of migration, where economic disparities between poor and wealthy countries drive high migration aspirations. However, insufficient resources likely constrain migration capabilities despite a strong desire to migrate (Carling, 2002; De Haas, 2021). In contrast, countries with a GDP per capita between $2,000 and $4,000 experience a sharp decline in net migration, suggesting that populations within this income range exhibit high mobility. Beyond a GDPpc of $4000, the decline in net migration becomes less pronounced, eventually turning positive and reaching an equilibrium at approximately $7000. This finding differs from Figure 4 above, which states that migration equilibrium at GDPpc is around $4000. In this context, a GDPpc of around $4000 may represent a threshold or ‘take-off’ point for the “take-off” in migration transition (De Haas, 2010b; Zelinsky, 1971). Similarly, net migration rates rise significantly in high-income countries with a GDPpc exceeding $8,000, indicating that achieving a GDPpc of at least $4000 is critical for initiating the migration transition.

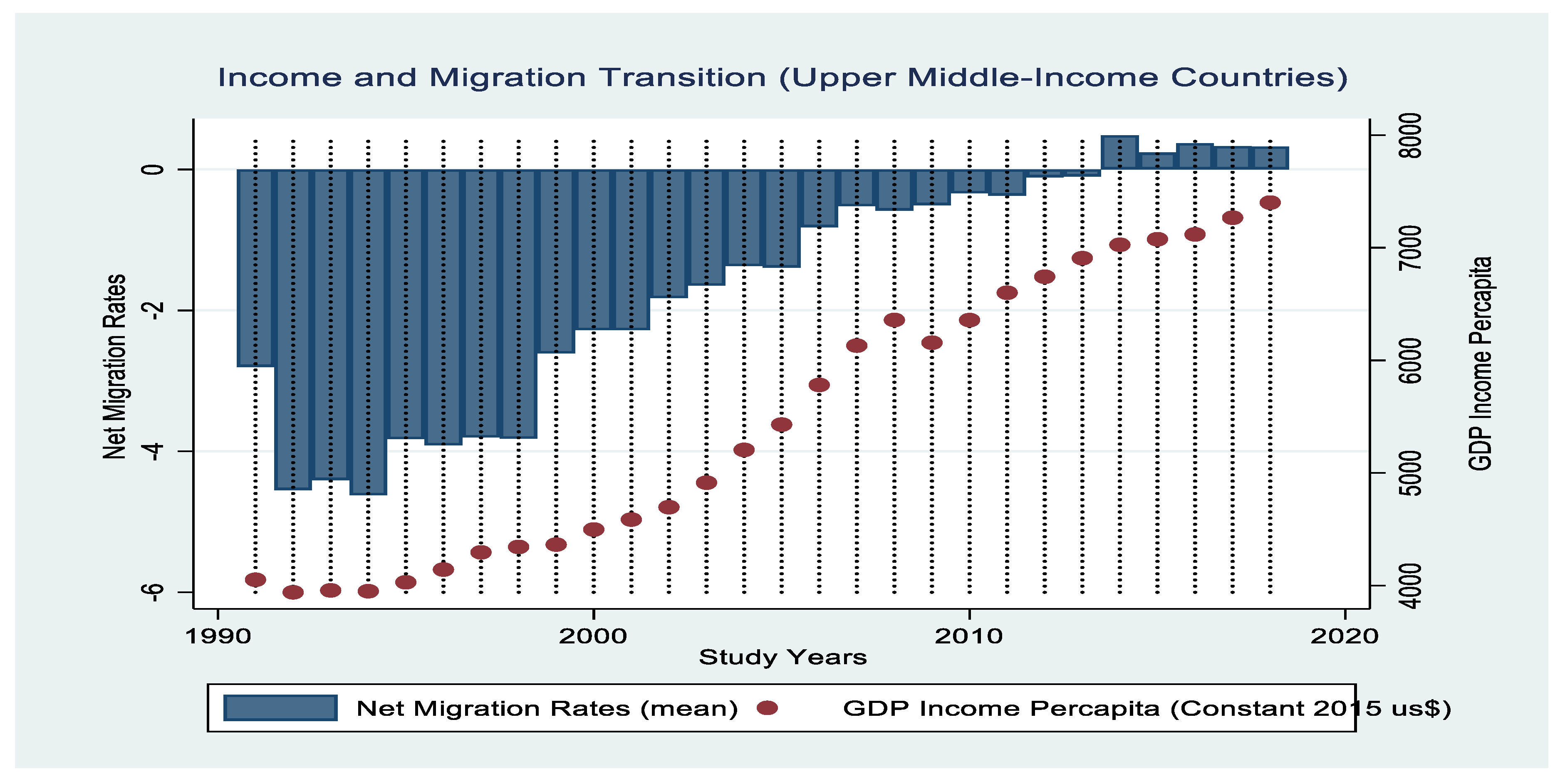

Figure (&) below examines migration transition trends in Upper-Middle-Income Countries (UMICs). The analysis involved a unique calculation method: First, a panel dataset of 33 upper-middle-income countries was compiled over 28 years (1991–2018). Next, mean values for net migration rates, GDP per capita, and HDI were calculated separately for each year. Finally, the mean values of net migration rates (NMR) were analyzed alongside GDPpc and HDI to pinpoint migration threshold shifts from net emigration to net immigration (equilibrium/transition).

Figure 11.

Income-Migration Transition Relationships. Source: Author’s creation using data from 28 upper-middle-income countries.

Figure 11.

Income-Migration Transition Relationships. Source: Author’s creation using data from 28 upper-middle-income countries.

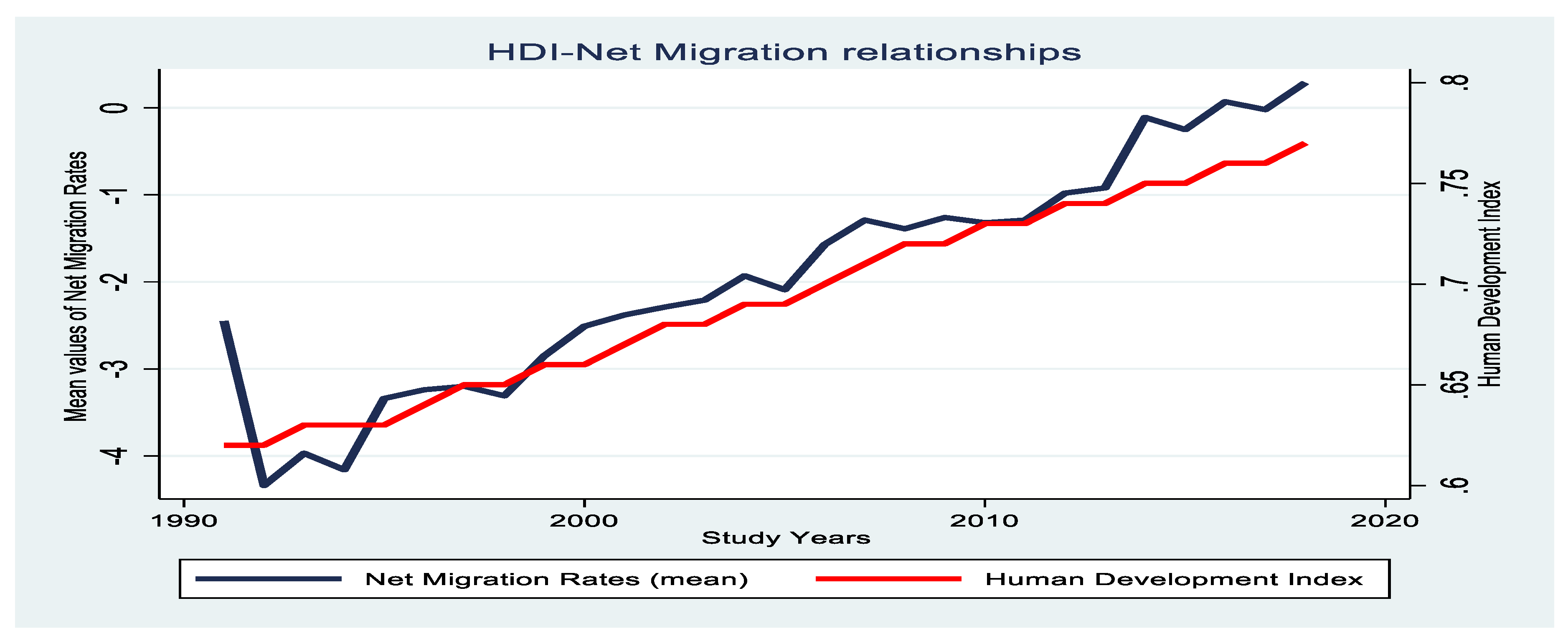

The results show that net migration improves as countries transition to lower-middle-income status at around $4000 and reach equilibrium at approximately $7,500 GDP per capita. Similarly, net migration begins to improve at an HDI of about 0.6 and stabilizes at an equilibrium of around 0.78. These findings suggest that countries need a GDPpc above $75,000 and HDI values exceeding 0.75 to achieve migration equilibrium. However, in this analysis, the net migration-development relationships are linear.

Figure 12.

HDI-Migration Transition Relationships. Source: Author’s creation using data from 28 upper-middle-income countries.

Figure 12.

HDI-Migration Transition Relationships. Source: Author’s creation using data from 28 upper-middle-income countries.

As shown in the four QDAs, these mixed results suggest that migration transition and equilibrium stages can vary depending on whether net migration or emigration rates are analyzed. Human migration’s complexity and dynamic nature make it challenging to pinpoint transition stages precisely.

4.2. Findings from Regression Analysis

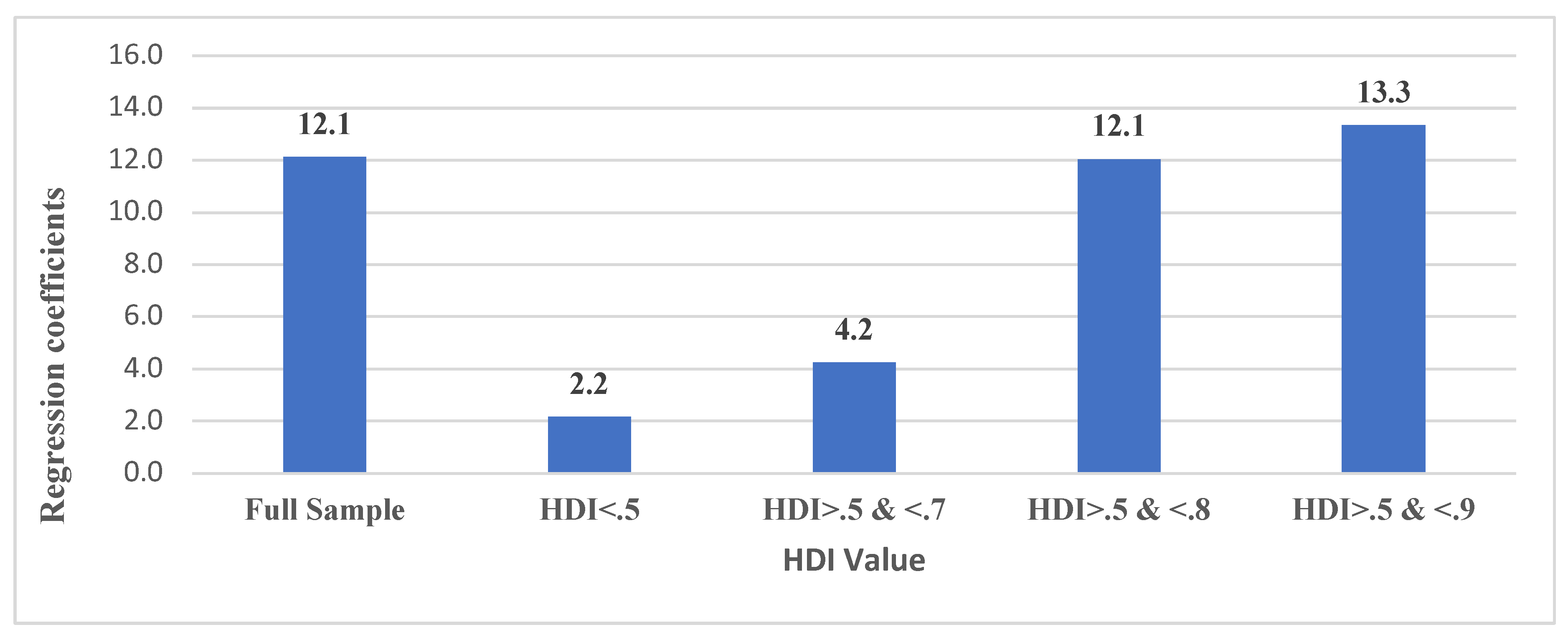

4.2.1. The Influence of Domestic Socioeconomic Factors on Migration Decisions in LMICs: Using HDI as a Proxy for Socioeconomic Development (1)

Models (1-5) (

Table 1) below present several econometric models to analyze how socioeconomic development, measured by the Human Development Index (HDI) as an explanatory variable, affects migration trends, transitions, and capabilities in LMICs. The HDI serves as a proxy for socioeconomic development in countries of migrant origin. Five models are constructed and regressed using a Two-step System GMM approach, with the Net Migration Rate (NMR) as the dependent variable. We aggregate the data into different HDI levels to capture development-level influences. Model 1 (Full Sample) includes all countries in the dataset regardless of HDI level, providing a general overview of the relationship between HDI and NMR. Model 2 (HDI < 0.5) focuses on countries with very low levels of human development, examining migration dynamics in this subset. Model 3 (HDI > 0.5 & < 0.7) analyzes migration trends in countries with low to medium levels of development. Model 4 (HDI > 0.5 & < 0.8) investigates the relationship in countries with moderately higher HDI levels. Finally, Model 5 (HDI > 0.5 & < 0.9) explores migration patterns in countries nearing high development but still classified as middle-income. Each GMM model incorporates the lagged NMR (NMRt−1) value as an explanatory variable to account for persistence in migration trends. Details of the models are provided in the Annex.

The Arellano-Bond AR(2) test checks for second-order autocorrelation, with an insignificant p-value (p > 0.05) confirming valid GMM estimators. The insignificant AR(2) p-value confirms no second-order autocorrelation, validating the instruments in the results above. Likewise, the Hansen test evaluates the validity of the instruments used in our GMM estimation. It tests the null hypothesis that the instruments are valid and uncorrelated with the error term. A p-value greater than 0.05 suggests that the instruments are valid. Most of the Hansen statistics satisfy this criterion. However, two p-values fall below the threshold, possibly due to the smaller number of groups resulting from the HDI cap applied in the regression model. The key highlights of the regression results are illustrated in

Figure 6 below.

Figure 13.

Influence of HDI Level on Migration Decision and Transition. Source: Created by author.

Figure 13.

Influence of HDI Level on Migration Decision and Transition. Source: Created by author.

The above dynamic panel regression reveals that increasing HDI levels significantly contribute to positive net migration in LMICs right from the early stages of development. The coefficients for the lagged NMR look positive and highly significant (p < 0.01) across all models, indicating that past migration trends strongly influence current migration rates. For the HDI > 0.5 & < 0.7 group (Model 3), HDI’s coefficient (4.239) is positive but weakly significant. This indicates a moderate association between HDI and NMR in this subgroup. However, for HDI > 0.5 & < 0.8 and HDI > 0.5 & < 0.9 groups (Models 4 and 5), the coefficients (12.05 and 13.34, respectively) are bigger. This substantial magnitude of the coefficients underscores the significant impact of HDI on fostering positive net migration in origin countries. Additionally, the results indicate that the relationship between net migration and HDI is linear, even at low HDI levels. This contrasts with previous assumptions (Clemens, 2014; De Haas, 2010a, 2021; Zelinsky, 1971), which suggests that migration-development relationships are non-linear.

Based on these results, using net migration as a metric to examine migration transition and equilibrium offers a different and potentially more realistic perspective on migration trends. This approach provides deeper insights into the dynamics of migration patterns, particularly in the context of development. Furthermore, the findings suggest that enhancing HDI significantly contributes to positive net migration, thereby empowering individuals in LMICs to view migration as a voluntary choice rather than a forced necessity.

Regarding other control variables, the coefficients for population growth and total population are positive and statistically significant across all models; this outcome likely reflects the positive influence of demographic factors, such as population growth and total population, on net migration. However, migration constraints prevent individuals from migrating proportionately to population growth and size, leading to positive net migration for sending countries. But, unemployment (UNEMP) rates show weak significance in specific subsamples, indicating a potential localized effect. Other control variables, such as economic freedom (ECO_FREEDOM) and internet usage (INTERNET), do not show statistically significant results across most models, suggesting their limited influence on net migration rates compared to HDI.

4.2.2. Influence of Domestic Socioeconomic Factors on Migration Decisions in LMICs: Using Human Development Index (HDI) as a Proxy for Socioeconomic Development (2).

Models (1-5) in

Table 2 below present an analysis of the influence of HDI, employing different sets of control variables to assess the robustness of the results. In Model 1, the control variables include the unemployment rate (UNEMP), economic freedom (ECO_FREEDOM), population growth (POPGRO), total population (LnPOPTOTAL), and maternal mortality rate (logMMR). Model 2 introduces Internet access (INTERNET) as an additional control variable. Models 3 and 4 exclude logMMR but incorporate civil participation (Civic_Part) as a control variable. Model 4 further includes both logMMR and INTERNET simultaneously. Finally, Model 5 includes all the aforementioned control variables in the regression analysis.

The AR(1) test values, such as 0.024 and 0.026, are low and statistically significant, indicating no evidence of problematic first-order serial correlation in the residuals. Similarly, the AR(2) test values are 0.135 and 0.131, which are not statistically significant, confirming no evidence of second-order serial correlation in the residuals. These findings support the model’s dynamic structure being well-specified and robust. Furthermore, the Hansen statistics, ranging from 0.393 to 0.655, are well above conventional thresholds, indicating that the instruments used in the GMM estimation are valid and appropriately chosen. Together, these results confirm the robustness and validity of the model and its instruments.

The regression results highlight a strong and statistically significant relationship between the Human Development Index (HDI) and the Net Migration Rate (NMR) in 109 low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) over the period 2000–2018. The coefficients for HDI across all models (1 to 5) are positive and significant at the 10% level, ranging from 9.144 to 13.79, indicating that improvements in socioeconomic development, as proxied by HDI, are associated with higher net migration rates. The lagged dependent variable (NMR_lag) also shows significant persistence, with coefficients between 0.515 and 0.556, suggesting that past migration trends strongly influence current rates. Robustness checks, incorporating various control variables, reinforce the consistency of these findings. The control variables show consistent results similar to those in

Table 1 above.

4.2.3. Influence of Domestic Socioeconomic Factors on Migration Decisions in LMICs: Using GDP per capita as a Proxy for Economic Development.

In

Table 3, the influence of GDP per capita on net migration is analyzed using different sets of control variables to evaluate the robustness of the results. In Model 1, the control variables include the unemployment rate (UNEMP), economic freedom (ECO_FREEDOM), population growth (POPGRO), and total population (LnPOPTOTAL). Model 2 introduces Internet access (INTERNET) as an additional control variable. Model 3 builds on Model 2 by incorporating maternal mortality rate (logMMR) while excluding civil participation (Civic_Part). Model 4 includes all the control variables from the previous models, and Model 5 further adds inflation (INFLATION) alongside all other control variables.

The AR(1) p-values (ranging from 0.021 to 0.034) confirm the presence of first-order autocorrelation, which is expected in dynamic panel models. Notably, the AR(2) p-values (ranging from 0.092 to 0.145) are greater than 0.05, indicating no second-order autocorrelation in the first-differenced residuals—a key assumption for the validity of the instruments in the GMM framework. The Hansen statistic p-values (ranging from 0.209 to 0.450) are also well above 0.05, suggesting that the null hypothesis of valid overidentifying restrictions cannot be rejected. Together, these diagnostics confirm that the model is correctly specified, the instruments are appropriate, and there is no significant endogeneity or misspecification.

Specifically, the lagged NMR (NMR_lag) is consistently positive and highly significant across all models, ranging from 0.567 to 0.642. This highlights the persistence of migration trends, indicating that past migration patterns strongly influence current migration flows. The coefficient of logPerCap is positive and statistically significant across most models from 1 to 5. This suggests that increased per capita income is associated with positive net migration rates; however, its influence is lower than HDI. A 1% increase in GDPpc is estimated to increase the net migration rate by approximately 0.99 to 1.79 units, depending on the model specification. This positive relationship indicates that a higher income level in a country encourages individuals to stay rather than migrate. Like the regressions above, the results indicate that the relationship between net migration and GDPpc is linear, even from the low-income status. Again, these results contradict the previous assumptions (Clemens, 2014; De Haas, 2010a, 2021; Zelinsky, 1971), which suggest that migration-development relationships are non-linear.

Table 4.

Comparing the Impact of HDI and GDPpcon Net Migration Rates in LMICs (corresponding to Tables 2&3).

Table 4.

Comparing the Impact of HDI and GDPpcon Net Migration Rates in LMICs (corresponding to Tables 2&3).

| Regression Models |

GDPpc (Regression coefficients) |

HDI (Regression coefficients) |

HDI-GDPpc difference

|

Remarks |

| Model-1 |

0.99 |

9.14 |

8.15 |

While GDPpc plays a role, HDI has a significantly greater influence (10.69 times greater) on increasing net migration. Therefore, enhancing HDI status could serve as an effective strategy for shifting migration from a necessity to a choice for individuals in LMICs |

| Model-2 |

1.17 |

12.13 |

10.96 |

| Model-3 |

1.24 |

12.91 |

11.67 |

| Model-4 |

1.35 |

11.89 |

10.54 |

| Model-5 |

1.79 |

13.79 |

12.11 |

| Average difference: |

10.69 |

|

The above comparisons suggest that HDI and GDP per capita influence on net migration varies significantly. HDI has a more substantial impact on positive net migration, with its effect being, on average, 10.69 times greater than GDPpc. Across the models, the coefficients for HDI range from 9.144 to 13.79, indicating a substantial positive impact on NMR. In contrast, the coefficients for GDPpc range from 0.994 to 1.785, showing a positive but comparatively weaker impact. This suggests that while socioeconomic development as measured by GDPpc influences migration decisions and transitions, broader aspects of human development as represented by HDI—such as health, education, and overall quality of life—play a more significant role in shaping migration decisions, especially in increasing net migration in LMICs.

Table 5.

The key findings from the study are summarized in the table below:.

Table 5.

The key findings from the study are summarized in the table below:.

| S.N. |

Subject of Analysis |

Existence of |

Key Findings |

| Migration Transition and equilibrium |

Capability Constraints |

Capability Enablers |

| 1 |

QDA-1 (Figure 8):

Net Migration Trends by Income Groups (2000–2018).

|

Yes.

The transition begins at the upper end of the lower-middle income and equilibrium at the upper end of the upper-middle income category. |

No evidence.

Persistent negative net migration in low and lower-middle-income countries.

|

Yes.

Increasing GDPpc at the upper end of the lower middle-income category leads to a decline in emigration. |

Differences in global wealth and levels of human development serve as key drivers of international migration. The transition begins at the upper end of the lower-middle income and equilibrium at the upper end of the upper-middle income category. |

| 2 |

QDA-2 (Figure 9):

Migration transitions: based on GDPpc and emigration rates |

Yes.

Emigration reaches equilibrium at an approximate GDP per capita of $4,000. |

Yes.

Emigration rates are relatively low (5.73%) in the low-income bracket (PERCAP < 1000). |

Yes.

Emigration rates increase at 14.31% as income levels approach approximately GDPpc $4,000. |

In countries with low income (PERCAP < 1000, emigration rates are relatively low (5.73%). The migration equilibrium is observed at a GDP per capita of approximately $4,000, which does not align with previous findings, where it was identified as occurring at around $7,000–$8,000. |

| 3 |

QDA-3 (Figure 10):

Migration transitions in LMICs: GDPpc and net migration rates. |

Yes.

Beyond $4,000, out-migration begins to decline, reaching the equilibrium stage at a GDP per capita of approximately $7,000. |

Partially yes.

Countries with a GDP per capita below $2,000 exhibit negative but relatively stable net migration trends. |

Yes.

Countries with a GDPpc between $2,000 and $4,000 experience a sharp decline in net migration, likely due to rising incomes enabling individuals to afford migration costs. |

Countries with a GDP per capita below $2,000 exhibit negative but relatively stable net migration trends. In contrast, countries with a GDP per capita between $2,000 and $4,000 experience a sharp decline in net migration, indicating a highly mobile population within this income range. Beyond $4,000, out-migration continues to decline, reaching an equilibrium stage at approximately $7,000 GDP per capita. |

| 4 |

QDA-4 (Figure 11):

Migration transitions in UMICs (1991-2018): How do GDPpc and HDI interact with net migration trends? |

Yes.

The equilibrium point occurs at approximately a GDP per capita of $7,500 and an HDI of 0.78. |

NA |

Yes.

The equilibrium point occurs at approximately a GDP per capita of $7,500 and an HDI of 0.78. |

The equilibrium point occurs at approximately a GDP per capita of $7,500 and an HDI of 0.78. |

| 5 |

Regression Analysis (Table 1)

Dependent Variable: NMR

Explanatory Variable: HDI

Models: accounting for different HDI thresholds. |

Yes.

However, a linear relationship exists between HDI and NMR. |

Yes

The lowest regression coefficient (2.2) for the subsample HDI < 0.5 indicates the state of capability constraints in low-income countries. |

Yes,

The HDI brackets > 0.5 and < 0.8 and > 0.5 and < 0.9 coefficients are 12.05 and 13.34, respectively. These values indicate that HDI contributes to positive net migration. |

The coefficients for HDI are positive across all models, indicating that higher human development levels influence increased net migration rates and encourage people to stay or migrants to return. A linear relationship exists between HDI and NMR in LMICs, which questions previous claims that the relationship between development and migration is non-linear. |

| 6 |

Regression Analysis (Tables 2&3): Comparing the Impact of HDI and GDP per Capita on NMR

|

Key Findings:

The influence of HDI and GDP per capita on net migration varies significantly. HDI has a more substantial impact on positive net migration, with its effect being, on average, 10.69 times greater than GDPpc. The regression results question the theoretical assumption of non-linearity, revealing almost a linear relationship between development and migration. |

5. Conclusions and Policy Implications and Limitations

This paper aimed to examine the influence of domestic socioeconomic development on migration decisions, focusing on the transition and capabilities framework. The socioeconomic determinants used are GDP per capita and HDI. Panel data from 109 low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) spanning 2000-2018 were analyzed. A total of 15 dynamic panel regressions were conducted using the two-step system GMM model under varying conditions to evaluate the effects of GDPpc and HDI on net migration. Additionally, four Quantitative Descriptive Analyses (QDA) were performed to review the migration trends and patterns and provide a foundation for the subsequent analysis and inference. This study contributes to the migration literature in several ways. While much of the existing research has focused on the effects of migration on development, often adopting a “receiving country bias,” as noted by De Haas (2021), this study shifts the focus to the impact of domestic socioeconomic development on migration dynamics. It offers nuanced insights into the migration-development nexus by investigating how domestic indicators influence migration patterns.

Primarily, the study evaluated the influence of key socioeconomic indicators on migration trends, such as GDP per capita and the HDI. According to the dynamic panel regression results (

Table 1,

Table 2 and

Table 3), the HDI exerts a more substantial effect on positive net migration, with its impact being approximately 10.69 times greater than GDPpc. Across the models, the coefficients for HDI range from 9.144 to 13.79, indicating a strong positive correlation with net migration rates (NMR). In contrast, GDPpc coefficients vary between 0.994 and 1.785, showing a positive but weaker relationship. This comparison, largely overlooked in the literature, underscores that while economic growth (as captured by GDPpc) influences migration decisions, broader dimensions of human development, such as health, education, and quality of life (captured by HDI), are more critical in shaping migration dynamics. In addition, the regression results question the theoretical assumption of non-linearity, revealing almost a linear relationship between development and migration. Such patterns highlight the dynamic and context-specific nature of migration transitions and equilibrium stages, which depend on whether net migration or emigration rates are analyzed. This highlights human migration’s complex and dynamic nature, making it challenging to pinpoint these stages precisely. These results offer new insights into migration management policies, particularly in low—and middle-income countries (LMICs).

The study (

Figure 8,

Figure 9,

Figure 10 and

Figure 11) revisited the migration-development nexus by applying Quantitative Descriptive analysis (QDA). Some results questioned the previously generalized thresholds, showing that migration patterns are more nuanced. QDA in this study indicated that emigration rates rise with income, peaking at 14.31% when GDPpc reaches

$4,000. However, emigration declines to 12.08% for GDPpc above

$5,000 and further to 7.9% for GDPpc exceeding

$7,000. Interestingly, the migration equilibrium is indicated at approximately

$4,000 GDP per capita, based on emigration rates, and around

$7,000 when measured by net migration rates. Additionally, countries with GDPpc between

$2,000 and

$4,000 experience sharp negative net migration, indicating a highly mobile population in this income range.

Additionally, this research adopts net migration data rather than traditional metrics like emigration flows or stocks to examine migration trends and patterns. This approach provides a more comprehensive view of migration dynamics by accounting for inflows and outflows. The use of net migration is also expected to aid in measuring return migration trends, given the lack of data on the latter in many LMICs. Likewise, the study employs a two-step system GMM, an advanced statistical model, to analyze dynamic panel data to address potential biases such as endogeneity, heteroscedasticity, and omitted variable bias in the dynamic panel model. While prior studies often focus on specific countries or regions, this study encompasses 109 LMICs. Such a broad geographical scope allows for a more comprehensive understanding of migration transitions and provides actionable insights for policymakers. Hence, this research contributes a deeper understanding of domestic development-migration interplay. By identifying the relative influence of socioeconomic factors, questioning existing thresholds for migration transitions, and applying advanced statistical methods, the study provides a solid foundation for policy formulation and future research in migration studies.

This study underscores the need for countries to strengthen their domestic socioeconomic foundations to address the root causes of emigration effectively. Policymakers should prioritize sustained economic growth, job creation, and infrastructure development to reduce emigration drivers. Investments in education, healthcare, and social protection systems are equally crucial for enhancing human development and aligning workforce skills with local economic needs. Such efforts can help mitigate push factors, ensuring that migration decisions are driven by choice rather than necessity. Additionally, governments must focus on facilitating return migration through targeted measures like supporting entrepreneurship, recognizing skills acquired abroad, and implementing robust reintegration programs. Addressing structural inequalities and providing equitable access to opportunities is fundamental to reducing migration driven by hardship while acknowledging that migration, when well-managed, can significantly contribute to national development. We further emphasize the argument of de Haas & Rodríguez (2010) to conceptualize migration as an intrinsic part of broader processes of development, social transformation, and globalization rather than a ‘problem to be solved.’

Given migration’s complex and dynamic nature, governments should pursue adaptive and forward-thinking approaches instead of restrictive emigration policies and border controls. Policymakers should internalize migration as a natural and integral development component and work to create a socioeconomic environment that supports livelihoods and economic activities. This perspective shifts the focus from controlling outflows to fostering conditions where migration becomes a matter of choice rather than necessity. The world community will have to learn to live with large-scale migration for the foreseeable future (Haas, Castles, & Miller, 2019, p. 362). Sustainable economic growth, enhanced human development, and balanced migration systems can mitigate brain drain while promoting brain gain. Reforming the domestic investment climate to attract private sector involvement is critical for driving growth, creating jobs, and reducing reliance on remittances. In line with Bencek & Schneiderheinze (2020), this study emphasizes the importance of comprehensive migration management strategies to address the inevitable rise in global emigration during the early stages of economic development, ensuring mutually beneficial outcomes for both origin and destination countries.

Finally, enhancing the Human Development Index (HDI) can shift migration dynamics from being driven by necessity to becoming a matter of choice. This approach would help mitigate the adverse effects of brain drain, foster brain gain, and maximize the developmental potential of migration for origin countries, aligning with the broader goals of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the objectives of the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly, and Regular Migration (GCM).

5.1. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

The primary challenge in migration research is the lack of reliable and comprehensive data. As a complex human behavior, migration presents inherent difficulties in maintaining accurate, updated, and error-free records of population movements. Low-income countries, in particular, often lack the robust datasets necessary for panel data analysis. This study faced significant limitations in applying the System GMM approach based on income groups, mainly due to a limited number of groups and an overabundance of instruments. Additionally, the dataset utilized in this study could not be extended beyond 2018, as the COVID-19 pandemic heavily influenced data from subsequent years. The persistent challenges of collecting reliable cross-country data are compounded by the fact that most countries are more proficient at tracking immigration than emigration and often struggle to measure undocumented migrant flows.

While this study aimed to examine the influence of domestic socioeconomic factors on return migration trends, it could not proceed due to the severe lack of return migration data. Moreover, yearly data on emigration and immigration were also unavailable, further constraining the scope of analysis. Future research should address these gaps by utilizing comprehensive migration datasets to provide deeper insights into the development-migration nexus, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Efforts to collect annual, country-specific data on both emigration and immigration would enable more robust comparative analyses using advanced econometric methods such as System GMM. Such endeavors could significantly advance our understanding of migration behaviors, especially in the post-COVID-19 context, and inform more effective migration policies.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Descriptive Statistics: [Yearly Panel Data from 109 Low- and Middle-Income Countries (2000–2018; N=109, T=19)]

| Variable name |

Variable description |

Obs |

Mean |

Std. Dev. |

Min |

Max |

| NMR |

Net Migration Rate (NMR) of the countries |

-2.47 |

6.22 |

-35.72 |

31.41 |

-2.47 |

| PerCap |

GDPpc(constant 2015 US$) |

3281.87 |

2719.39 |

255.00 |

14223.00 |

3281.87 |

| GDPGRO |

GDP growth (annual %) |

4.41 |

4.53 |

-36.39 |

63.38 |

4.41 |

| UNEMP |

Unemployment rates, total (% of total labor force/modeled ILO estimate) |

8.06 |

6.60 |

0.14 |

37.32 |

8.06 |

| GCF |

Gross capital formation (annual % growth) |

7.36 |

22.36 |

-137.64 |

435.62 |

7.36 |

| INFLATION |

Inflation, consumer prices (annual %) |

7.18 |

12.05 |

-16.86 |

325.00 |

7.18 |

| HDI |

Human Development Index |

0.60 |

0.13 |

0.26 |

0.85 |

0.60 |

| Govt effect |

Reflects perceptions of the quality of public services, the quality of the civil service |

-0.50 |

0.56 |

-2.26 |

1.25 |

-0.50 |

| Civ Liberty |

Civil Liberty Index (Proxy for Human Rights) |

0.65 |

0.22 |

0.06 |

0.97 |

0.65 |

| Civic Part |

Civic Participation Index(a proxy for the level of democracy/ (VDEM) |

0.63 |

0.23 |

0.04 |

0.96 |

0.63 |

| INTERNET |

Internet use (% of population) |

17.71 |

19.30 |

0.00 |

81.20 |

17.71 |

| MOBILE |

Cellular Mobile Subscription (per 100 people) |

56.86 |

46.73 |

0.00 |

205.04 |

56.86 |

| ELECTRICITY |

Access to electricity (% of population) |

68.56 |

31.83 |

1.28 |

100.00 |

68.56 |

| LIFEEXP |

Life expectancy at birth, total (years) |

65.79 |

8.13 |

41.96 |

80.01 |

65.79 |

| REMITpGDP |

Personal remittances received (% of GDP) |

5.93 |

7.44 |

0.01 |

53.83 |

5.93 |

| ECO FREEDOM |

Economic Freedom Index |

55.43 |

7.78 |

21.40 |

76.30 |

55.43 |

| SecEduEnrol |

School enrollment, secondary (% gross) |

66.00 |

27.32 |

6.11 |

134.44 |

66.00 |

| MMR |

Maternal mortality ratio (modeled estimate per 100,000 live births) |

248.32 |

270.43 |

1.00 |

1366.00 |

248.32 |

| TFR |

Fertility rate, total (births per woman) |

3.47 |

1.51 |

1.08 |

7.73 |

3.47 |

| POPGRO |

Annual Population Growth of countries (%) |

1.56 |

1.18 |

-2.17 |

5.63 |

1.56 |

| URBANPOP |

Urban population (% of total population) |

46.86 |

19.05 |

12.98 |

91.87 |

46.86 |

| lnPOPTOTAL |

Natural Logarithms of total Population of countries |

15.81 |

2.06 |

9.17 |

21.06 |

15.81 |

| Source: Author’s computation. |

Appendix B: Matrix of Correlations

Appendix B1: [Corresponding to Table 1 and Table 2: Correlation Matrix (Explanatory variable: HDI, Annual Data, 2000–2018)]

| Variables |

(1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

(5) |

(6) |

(7) |

(8) |

(9) |

(10) |

| (1) NMR_lag |

1.000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| (2) HDI |

0.058 |

1.000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| (3) UNEMP |

-0.062 |

0.145 |

1.000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| (4) ECO_FREEDOM |

-0.059 |

0.245 |

0.158 |

1.000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| (5) POPGRO |

0.509 |

-0.527 |

-0.240 |

-0.178 |

1.000 |

|

|

|

|

|

| (6) lnPOPTOTAL |

0.133 |

0.066 |

-0.267 |

-0.015 |

-0.031 |

1.000 |

|

|

|

|

| (7) INTERNET |

0.090 |

0.660 |

0.128 |

0.291 |

-0.366 |

0.037 |

1.000 |

|

|

|

| (8) logMMR |