1. Introduction

Computational methods not only thread across to the arts but serve as a force of transformation, a revolutionary moment defining AI generative methods for new tools and aesthetics in how we see and make art and define cultural heritage [

1]. The shift in progress increasingly creates tension around heritage narratives, the self, human identity gender and new ways of seeing, as computational art, generative arts, and 3D methods advance. The split between museums as spaces of traditional environments struggle with computer arts while culture and immersive experiences are using new AI devices for seeing and experiencing. Standing on the sidelines of change, museums and galleries are apprehensive about opening their galleries to computer arts in computational frameworks. Added to this, the volatility of urban cities where museums and galleries mostly reside, presents the need for higher levels of security as artworks, especially ones of high value are under attack by groups using them to gain attention for high-profile causes as climate change. Having entered a period of war and destruction over the past few years, cultural heritage is in the process of being destroyed on a large scale, highlighting the need for preemptive digital conservation and preservation, and this ties to the increasing looting and theft of heritage.

The physicality of art in this new reality poses enormous challenges to cultural heritage, at a time when human life and living shifts to a computational existence over global platforms and neural networks, where the virtual world of doing and seeing predominates human existence reinforced by social media and yes, Hollywood films, and television streaming.

AI has brought new aesthetics and tools for making art and creating AI artworks, which is not only changing the way artists create but also how they see art in a new light, including aesthetics, function, frameworks, and interactivity across global locations and space. Emanating from a physical computer, AI art projects travel across the Technosphere, and the global ecosystem extending to outer space – and exist in both physical and ethereal states – all at once. The existence of art from mind and imagination in dynamic states of being real and virtual, has major implications for the role of the arts and artists as the age of AI seems increasingly omnipresent. With each iteration of AI technology, AI becomes more deeply entwined with the nature of life, reflecting how we see ourselves, the arts, and beyond – there is no escape. The 2024 Nobel Prize in Physics highlights the importance of “computational methods” in the development of neural networks [

5]:

“The pace of development in AI approaches is highlighted by this year’s Nobel prize in physics, which was awarded for the development of neural networks. The twin methods of computational protein design and computational protein structure prediction are now real tools, used by millions of scientists worldwide. Proteins to counter pandemic viruses can now be designed in a matter of weeks. It therefore wouldn’t be surprising if we see many other Nobels in the future being awarded for breakthroughs that use the power of artificial intelligence.”

A 2024 report by Dealroom gives statistics on investment in the creative industries and recommends that growth finance should be reimagined to boost the creative economy and support the UK government’s growth mission. However, this report reveals that since 2013–2023, 85% of investment has gone to IT, while investment in the creative industries was only 2.5% [

6]:

“The Growth Finance for Creative Industries report, published today, used data platform Dealroom to analyse 4,540 venture capital and angel investor deals in creative businesses. It found 85% of investments in the creative industries since 2013 were made in IT, software and computer services, compared with 3% of investments each in design, advertising and marketing, and film, TV, video and radio. The figure for music, performing and visual arts is 2%. Dealroom data also revealed that the overall share of investment in creative industries firms outside of non-IT, software and computer services, as a share of investments made across all UK sectors, fell from 7% in 2013 to 2.5% in 2023.”

Creative industries seem to cover a plethora of diverse areas of creative production, services and activities. The Dealroom report focusing on the UK, shows that venture capital has almost exclusively supported IT, software and computer services, with 51% going to London and 12% to southeast England; significantly, there is no mention of the arts community’s relationship with creative industries. A 2024 Policy and Evidence Centre report states [

7]:

“there is little venture capital investment in the creative industries outside IT, software and computer services, and what little there is, is predominantly in creative businesses based in London and the South East.”

Artnet’s report on the art market in 2023 [

8] aims to define the state of the creative industries, but surprisingly it omits digital and computer art, and seems unaware of the global audience for Hollywood films and streaming, despite the fact that it has grown exponentially, taking in billions of dollars. Remarkably, the report makes no mention of computer/computational art.

2. Research Methodology in a New Research Landscape

Following on from the approach in previous papers [

2,

3,

4], we introduce a research methodology that reflects new developments and convergences in the arts, computing, and technology using AI tools and ways of collecting information and data, applied to the subject matter of looking at human identity in the context of female and male gender and aesthetics. We navigate through time and space, looking forward and backward simultaneously, in ways that reveal patterns, influences, and change, broadly seen through the process of cultural transmission, a process comparable to a database developed to make AI generative art, where a large array of diverse sources and media, from sculpture and painting to film and video are increasingly enmeshed in AI creativity [

9]. For example, ChatGPT, Google search, and a range of digital media resources and experiences come together in support of new ways of seeing and thinking about Hollywood and Heritage that bring to bear both new questions and perspectives.

Inevitably this methodology, which more reflects on constructing a database of resources specialized to the subject at hand, is positioned to permeate boundaries of disciplines, while data and information are being shared across a range of fields as they transform and adapt to a global network framework. Considering heritage and Hollywood, we juxtapose not only the present and past but examine the present day from both an historical and contemporary lens.

Gathering information and data from diverse media sources, we include AI generative tools, personal experience, digital image capture and curation, observation, onsite experiences, real and virtual discussion, and person-to-person human interaction with artists, Hollywood film industry creatives, and how Hollywood increasingly interacts with cultural heritage and conflict, all part of our path of discovery. We apply methods to enhance user experience and interaction from an inside-out perspective, so that read-time varies with the level of engagement. Addressing the current trend of decline in reading while ways of learning and experiencing across media, real and virtual are expanding rapidly as is the number of participants. Further, we pursue an interdisciplinary approach making connections between the arts, technology, and global interaction [

10].

3. Makers of Female Identity

In this section, we consider various background issues involving both popular culture and artistic heritage that has led to the way females are perceived by society and by themselves in today’s digital world.

Identity Revolution – Andy Warhol, 1960 to 1980s

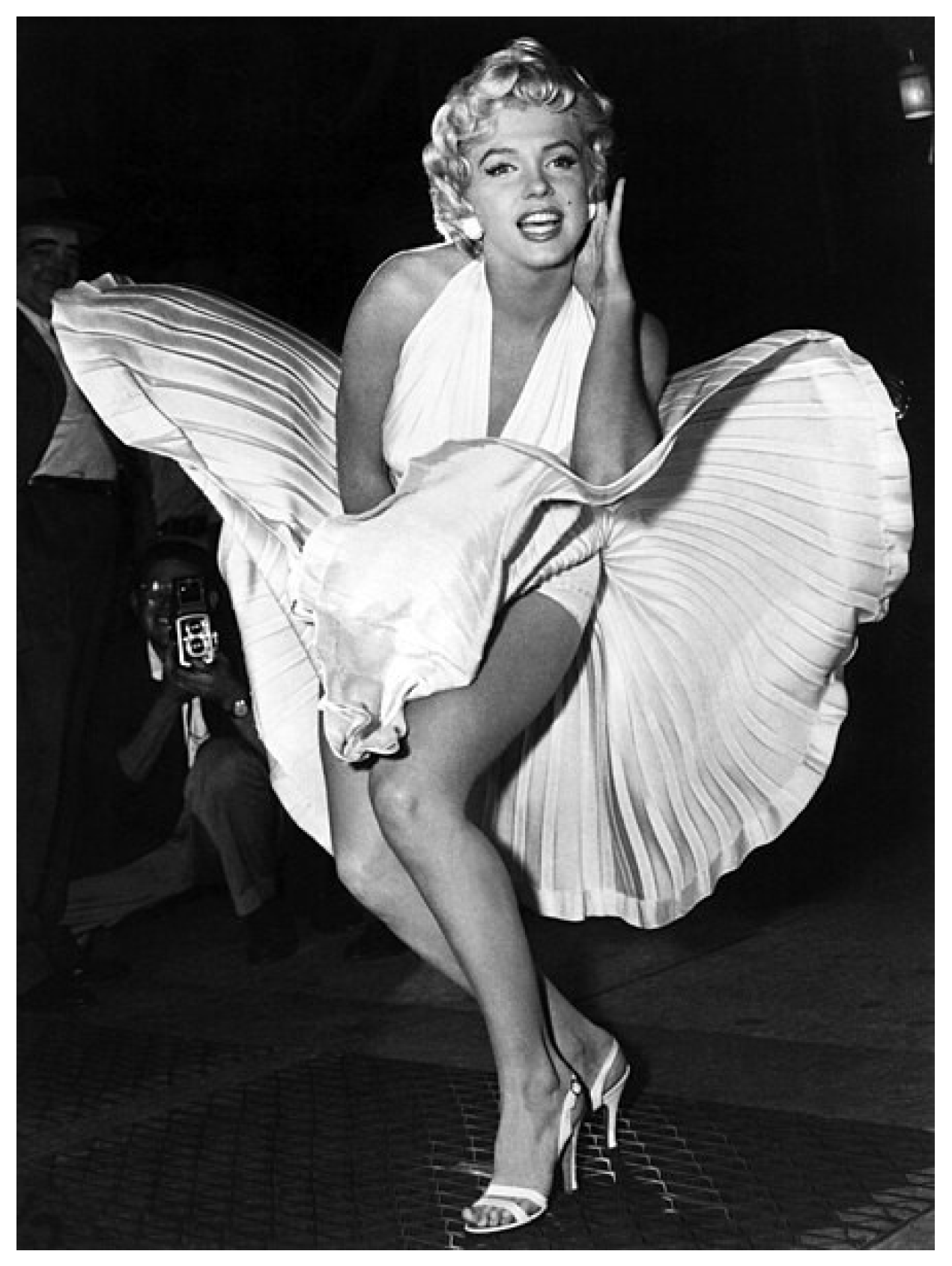

Andy Warhol loved Hollywood culture, namely, the omnipresent public persona of Hollywood stars rooted in popular media, which inspired his iconic portraits from Marilyn Monroe [

11] and Elizabeth Taylor to Mao Zedong and Che Guevara. This continues to influence how we see art and ourselves, and broadly expresses human aesthetics and sexuality à la Hollywood, a vision imprinted on our minds and psyche. We live in a visual culture being defined by visual media as television, film, immersive digital environments, smartphone photography as selfies, and trending 3D AR and VR devices. Warhol captured his thoughts on art and technology, saying in 1962, “The reason I’m painting this way is that I want to be a machine” [

12]. His dream would be further realized in the 1980s when his star power electrified the public debut of the Commodore Amiga home computer at Avery Fisher Hall, Lincoln Center, New York City – and it was love at first try creating computer art [

13].

Warhol’s far-reaching vision encompasses the 1960s, when he elevated pop art to a status on par with fine art, thus opening up the art world to include the general population, an equalizing moment moving past art elitism, and then in the 1980s with his embrace computer art. Building on these historic milestones, we examine human identity from the perspective of gender roles and their representation in Eastern and Western arts, from the first Millenium to the present remains at the heart of our sexual and aesthetic sense of self, and central to Hollywood culture which now, more than ever is relevant to everyday life as it streams across global networks, a dominant force in how we see ourselves in a brave new world of art, technology, and cultural heritage under the aegis of AI and computational culture [

1], as we are engulfed in war, human identity, and gender crisis [

4]. We consider Hollywood further in the next subsection and return to Andy Warhol’s influence in more detail later in this section.

Disneyland – Fairytales and Hollywood Dreams

The famous Hollywood billboard (see

Figure 1), on display in Griffith Park, Los Angeles, was constructed in 1923 as “Hollywoodland” until 1949. Rebuilt in 1978 and repainted in 2023, it stands at 45 feet tall and is now an internationally well-recognized symbol of Hollywood as place. It conveys a powerful heritage message at the heart of the LA identity narrative – where the stars live, and where the big studios were built, such as the Burbank Studios. Fast forward to the present, and Hollywood, the geographic place, has evolved through computational culture to reflect a state of the mind of populations around the globe occupying their conscious and unconscious states of mind in real and virtual life, a symbol of human imagination and dreams of human existence.

Disney stories and characters in film and video, have become an integral part of Hollywood culture playing a key role in serving up art and entertainment for children, featuring fairytales on the silver screen as Snow White, Sleeping Beauty, Cinderella, and Alice in Wonderland. These Disney “classics” now considered part of American cultural heritage, move into the future with new forms of expression through film and animation streamed to global audiences. Disneyland, a physical place (see

Figure 2), a virtual space, and an iconic symbol of human imagination, creates a “fantasyland” and a dreamscape ingrained at an early age in human consciousness and gender identity. As of late, billions of people are increasingly living a Disneyland life, made ever more real with a growing metaverse using new devices offering AR and VR providing a new menu of options for computational life.

Disney fairytales, such as Sleeping Beauty, find inspiration in the 17th-century fairy tales of Charles Perrault, a member of the French Academy. Perrault’s book of fairy tales, in turn, was influenced by 14th-century folk tales credited for establishing a new genre of storytelling that continues to present. Disney characters, especially for babies and children, who are visual and sound learners, have a deep and lasting impact on their sense of identity, gender, and sexuality, areas now at the heart of a global cultural and gender revolution becoming increasingly contentious and even violent.

Global Diffusion of Hollywood’s Cultural Mystique – From Monroe to Barbie and Cinderella

This iconic image of Marilyn Monroe continues to exert a powerful influence on female identity in contemporary culture, as we see comparing Monroe’s persona in

Figure 3 to the image of Disney’s Cinderella (see

Figure 4) from the 2015 Fandom film,

Cinderella.

The debut of the Barbie Doll in 1959 (see

Figure 5) reinforces the Monroe/Barbie archetype of female identity à la Hollywood, featured in the 2023 Academy award-winning film, Barbie staring Margo Robbie as Barbie, with female Director Greta Gerwig, a first of sorts for Hollywood accolades.

Barbie’s blonde hair, prominent breasts, eye makeup, high heels, tiny waist and long legs reflect mainstream Hollywood as could be seen in the 2024 Emmy Awards show, which was live broadcast at the Peacock Theater in Los Angeles. This was broadcast by ABC, projecting the event across the global stage lighting up powerful social networks and communication platforms. A barometer of television and media, the Emmys take center stage in their transmission of global cultural perspectives on human identity, gender and more broadly cultural conflict.

From the Red Sea to the Red Carpet, the Arts and Cultural Heritage Transmit Enduring Personas Defining Masculinity and Femininity

The Red Sea sits at the cradle of human civilization connecting East – Egypt, Israel, Iraq, and Iran to West – Greece and Rome, steeped in the Hebrew scriptures of the Old Testament linking to the New Testament of the Christians, with the birth of Christ, marking some 2,500 years of history. Fast forward to the Renaissance, this most fecund period defined by its great artists, such as Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Rafael, and Caravaggio, were inspired by stories from the bible to express the soul, spirit, and beauty of human life. Da Vinci’s voluminous notebooks are a testament to the birth of humanism, but also to an ingrained view of female identity, women in society, that still holds sway, from extremely oppressive states of being, for example, Afghanistan to Iran, where women are hidden under robes and scarfs, to Hollywood, promulgator of gender identity, and where women are defined by sexual prowess and beauty, trapped in male expectation [

14]. (See

Figure 6 and

Figure 7.)

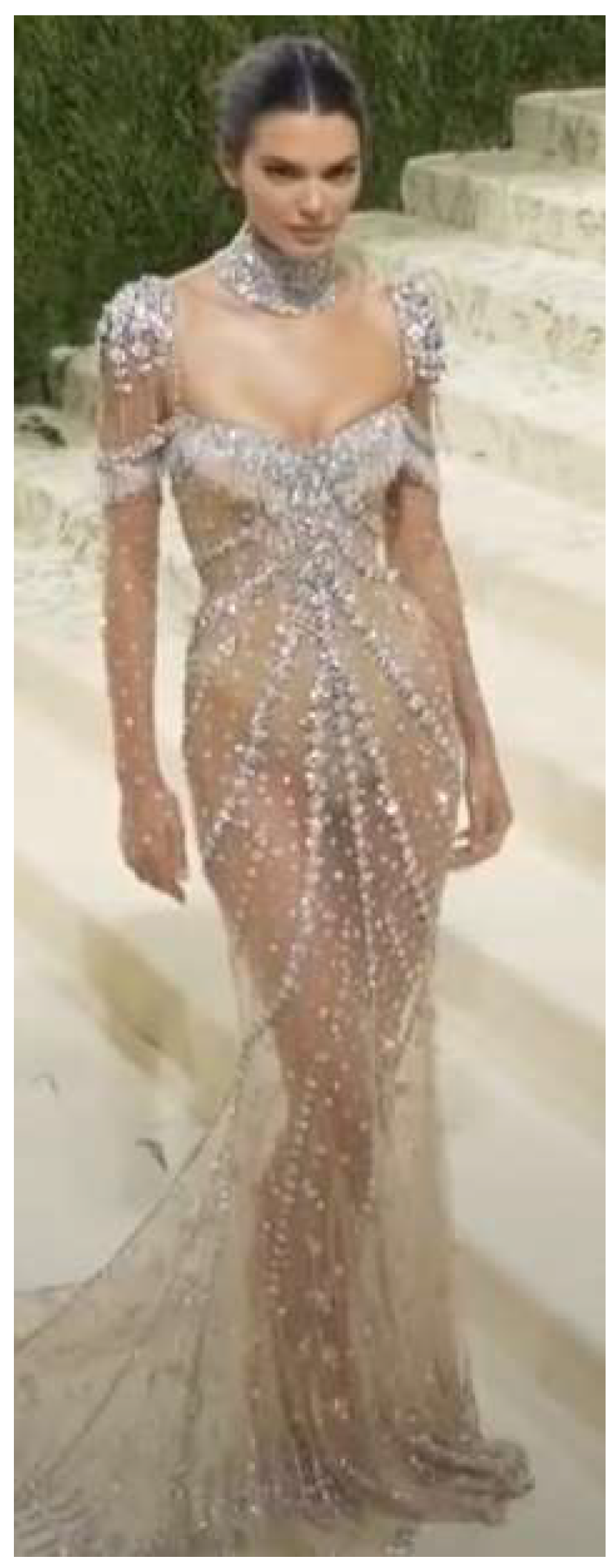

Comparing the persona and dress of Kendall Jenner, 2021,

Figure 6 above, and that of the early 12th-century sculpture of a Cambodian woman,

Figure 7, also above, we see a strong commonality in the way each symbolizes the female body and dress. The juxtaposition of these two images centuries apart, West and East, powerfully conveys female identity, present to past and back again – quite astonishing!

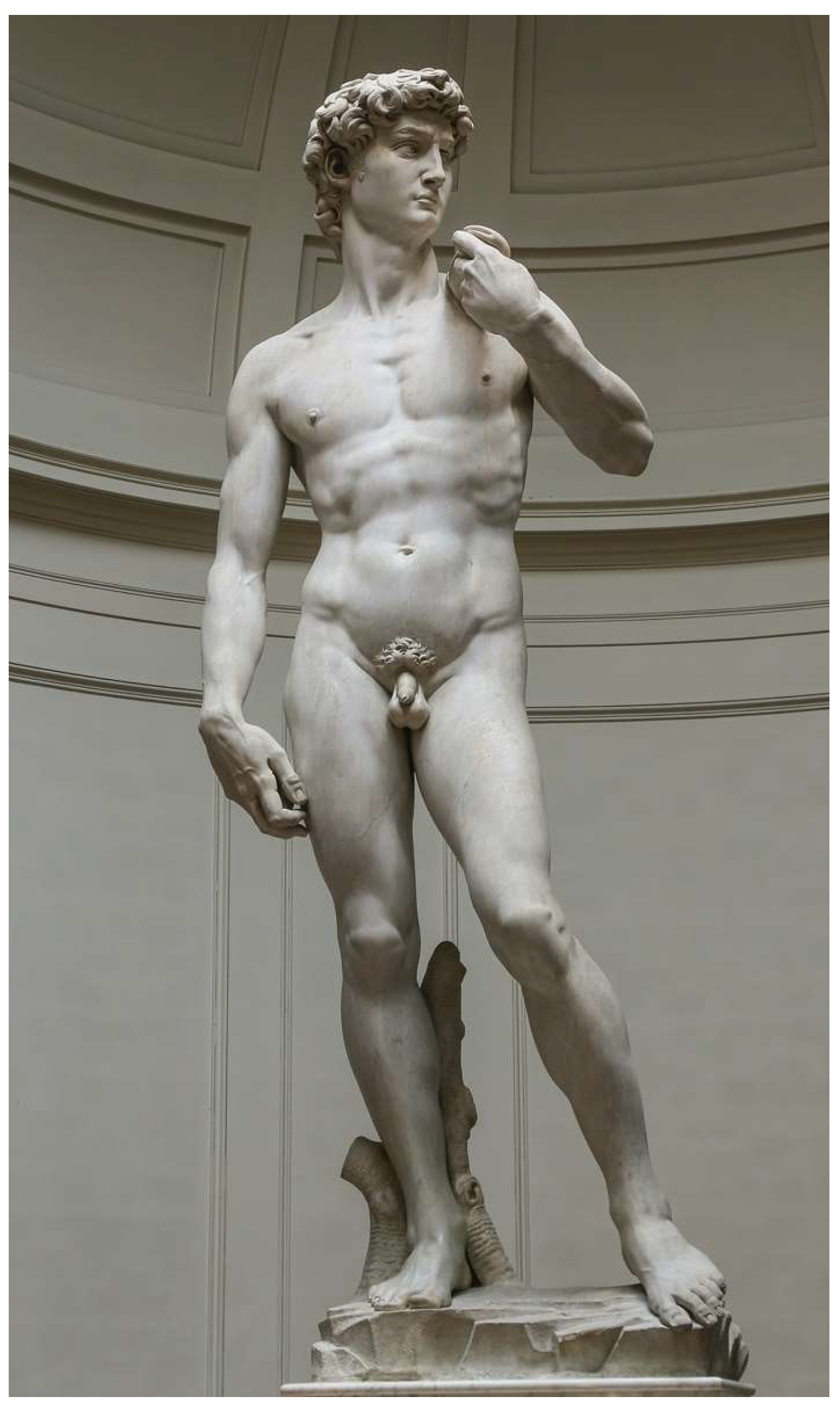

The Art of Michelangelo Defines the Physical and Spiritual Essence of the Male Persona from Antiquity to the Renaissance

In many respects Michelangelo’s conception of the male figure as one of strength, power, and aesthetics of the physical perfection of masculinity, continues to symbolize the ideal male in the 21st century (see

Figure 8) – the very one on view in sports, and halls of power and influence, mostly dressed up in the two-piece suit, blue or black, with a shirt and tie, the vogue du jour; but not so for women, who walk the red carpet at Hollywood-style events, and wear for the most part their Barbie-like dresses, a place in the public square where gender difference is played out.

David and Goliath, a biblical story symbolizing male strength and courage, is the subject of numerous Hollywood films. The 2016 film,

David and Goliath, directed by Wallace Brothers, is placed by the IMDb database as follows [

15]:

“At the crossroads of two great ancient empires, a simple shepherd named David transforms into a powerful warrior and takes on a terrifying giant. One of history’s most legendary battles is retold in a stylistic, bloody tale of courage and faith.”

The ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican, famous for Michelangelo’s masterpiece completed in 1512, captures the male physical being with his nude figures at the heart of human identity and picturing the moment the hand of God and the hand of Adam are about to touch. We feel the energy of that moment – described as the birth of Adam. Thus, Michelangelo’s Renaissance art and Humanism portray a Biblical moment (Genesis 2.7) defining male identity, its physical and spiritual states that continue to portray the ideal male physique and states of being.

Cultural Symbols of Female Identity – Transcendent Images

Botticelli’s Venus makes her debut floating to shore on a seashell, her eyes focused on an assumed audience, nigh astonished by her nude body, while Hollywood stars, emulate symbols of female identity codified in the Renaissance as seen in Botticelli’s Venus – see her popup breasts, small waist, long legs and blonde hair, a Barbie-like mermaid, like the Hollywood stars making their entrance on the magic red carpet of award ceremonies (see

Figure 9). Botticelli’s Renaissance Venus makes strong connections with the marble Venus de’ Medici also in the Uffizi, a Hellenistic marble sculpture of the Greek Goddess of love, Aphrodite from the 1st-century BCE, looks to her right, while we see the full face of Botticelli’s goddess staring out with a dreamy otherworldliness – that in many ways defines the new Renaissance women (see

Figure 10). Although it references Greek classicism in art, it brings a fresh Renaissance vision of female beauty capturing in the first instance the viewer’s emotions reacting to Venus’ sensuality and physical beauty that overwhelms the reality of her calm beauty [

16].

We see that the

Venus de’Medici (

Figure 10) has the same arm and hand positions as Botticelli’s Venus, while the female form in both, her hour-glass figure symbolizing female beauty, has not changed in more than a thousand years – and the one worshipped by Hollywood in its films and other productions – view, Kardashian and Beyoncé, causing women to take radical means to meet this ideal of beauty and sexuality of being female, that often leads to plastic surgery, drugs, makeup, Barbie-like fashion, and more.

Human female identity, seared into our consciousness, is symbolized by a range of manifestations through art, both East and West over some 5,000 years. This relentlessly defines the essence of femininity to present, the good, the bad, and the ugly, in symbolizing a goddess, saint, mother and child, Madonna, motherhood, Medea, Medusa, saint and diva. Importantly, in the process of cultural transmission, art reigns supreme as the key force influencing human gender identity in the mind and spirit, both conscious and subconscious, dreams and nightmares.

Fast Forward to the 1960s and 1970s: Blurring the Lines of Gender Identity

In the Metaverse, we shift from seeing to being, as TikTok users turn themselves into screen identities with millions who are not only watching but also interacting online. As people across the world are more consciously creating their identity and making aesthetic choices, fashion is playing a key role in dressing up the self – hail to the selfie – a computerized creation of self, using mechanical process – thank you Andy Warhol – it seems your Amiga paint selfies were the first.

Andy Warhol, Pioneer of Pop Art, Gender Identity and Computer Art (1960s to 1980s): This Trifecta of Warhol, the Ultimate Influencer of the 21st Century

Andy Warhol made the early Commodore Amiga computer a creative and artistic force (see

Figure 11) and became a pioneer of digital computer art [

13]. He created a portrait of Debbie Harry while on stage testing the Amiga in 1985. 39 years later in August 2024, that digital artwork was sold by one of the engineers who worked with Warhol for US

$26 million [

17]. The sale included the diskette signed by Warhol containing ten images that the pop artist created on the Amiga computer.

Warhol filmed portraits of celebrities. Christie’s and the Andy Warhol Museum have staged a pop-up show of the artist’s “Screen Tests” during Frieze Los Angeles in 2024 [

18].

“Christie’s last made headlines with Warhol in 2022, when the artist’s Shot Sage Blue Marilyn (1964) sold to dealer Larry Gagosian for $195m (including fees) at its New York salesroom. The result set a new record for the most expensive 20th-century work ever sold at auction.”

In 2019, an exhibition of Warhol’s artistic efforts with the Amiga computer was held [

19]:

“In the early 1980s, home computers were a competitive market and technology companies were vying for marketing and branding opportunities. Commodore and Apple were two companies that lead the race. Although Warhol signed with Commodore first, he met Steve Jobs, the founder of Apple, Inc., a year earlier at a birthday party for Sean Lennon, the son of musician John Lennon and artist Yoko Ono.”

Warhol recorded his first encounter with Steve Jobs which was captured in his diaries. On Tuesday, October 9, 1984, Warhol wrote [

20]:

... there was a kid there setting up the Apple computer that Sean had gotten as a present, the Macintosh model. I said that once some man had been calling me a lot wanting to give me one, but that I’d never called him back or something, and then the kid looked up and said, ‘Yeah, that was me. I’m Steve Jobs.’ And then he gave me a lesson on drawing with it…I felt so old and out of it with this young whiz guy right there who’d helped invent it.”

Warhol is also recognized as the originator of selfies for his early use of a Polaroid camera to create self-portraits [

21]. He used a form of Instagram to record his life before Instagram existed.

Warhol and Mechanically Generated Art

A fundamental change that we attribute to Warhol is the shift to pop art and media tech on a global scale influencing audiences and artists worldwide. Warhol “generated” art from photography and mechanical processes to home computer art, anticipating contemporary regenerative art and aesthetics [

18].

“Hollywood was everything to Andy from the time he was a boy in smoky, gritty Pittsburgh and would escape to the cinema and the land of make believe,” says Patrick Moore, the director of the Pittsburgh-based Andy Warhol Museum”.

Warhol’s portraits, especially his Monroe portraits in film from the 1960s show his influence on art, technology, and Hollywood, and his focus on public persona, and human identity. His portraits of film and pop music stars sell at auction at prices associated with great master paintings [

22]:

“Marilyn stands in line with the Mona Lisa, Boticcelli’s Birth of Venus and Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon,” says Alex Rotter, Christie’s chairman of 20th- and 21st-century art, at a press conference unveiling the work at Christie’s. He adds that a painting like the Marilyn could fundamentally change “not only Warhol’s market, but the market itself.” The last time one of the five 40in by 40in Marilyns sold at auction, in 1998, the estimated price was between $2m to $3m. It sold for $17m.”

Warhol redefined the art world with his pop art opening the floodgates to artists of all stripes and colors – and we have not tuned back – we have Warhol to thank for diversity – and he laid the groundwork for moving from exclusivity to inclusion – and then Lennon and Ono with “imagine all the people”.

Television Miniseries on the Warhol Diaries

The Andy Warhol Diaries has been produced as a 2022 television mini-series [

23]. The diaries began after Warhol was shot in 1968, when Warhol began documenting his life and feelings. The diaries bring great insight into hidden aspects of his identity.

The Andy Warhol Diaries was first published at a book in May 1989, after Warhol’s death in February 1987 [

20]. The book’s 807 pages were edited by Pat Hackett, a friend of Warhol, who transcribed his daily dictations from 1976 until Warhol’s death. Many consider this an important part of our cultural heritage, and a portrait of Warhol during the 1970s and 1980s.

4. Symbols of Female Identity

As discussed in the previous section, Andy Warhol used a photograph of Marilyn Monroe from 1953 characterizing Monroe as “the blonde bombshell”, which seems to combine symbols of female identity – Medea and Ophelia. In this section we consider further cultural examples that provide symbolic representations of female identity. Nowadays, females can present themselves digitally on a level playing field online [

24].

Gustave Courbet’s Female Nude and Philosopher Jacques Lacan: To See or Not to See

The work of French philosopher, Jacques Lacan (1901–1981) was strongly influenced by Sigmund Freud, Jacques Derrida, and Michel Foucault. In 1955, he bought the highly provocative painting by Gustave Courbet,

l’Origine du Monde, painted in 1866, that recently inspired the first ever Lacan exhibition,

The Arts through the lens of Psychoanalysis, which took place at the Pompidou Centre in Metz during December 2023 to May 2024 [

25]. Courbet’s painting, from its first viewing to the present, has instigated protests and sit-ins. Now in the permanent collections of the Musée d’Orsay, Paris, it continues to attract the attention of activists. Courbet’s painting pushes the outer limits of the female nude, through the eyes of 19th-century French society. Was female identity being reduced to sex and reproduction?

Despite the shock and awe of the critics on first view, Courbet’s paintings of the female nude are now highly prized and considered masterworks of art loved by audiences worldwide (see

Figure 12). When the painting to the right was first shown in the Paris Salon of 1866, critics censured Courbet’s lack of taste as well as the model’s awkward pose and unruly hair. Clearly, Courbet’s

Woman with Parrot was perceived as provocative. The picture, however, was admired by contemporary artists. Paul Cézanne seems to have carried a small photograph of it in his wallet, and in 1866 Édouard Manet began his own version of the subject.

Courbet’s painting

Origin of the World is still the focus of protest demonstrations. A recent article in

Le Monde newspaper ties the protestor Deborah de Robertis to symbols of Medea – she is scandalized by her love in a “me-too” moment that brings together Courbet, Lacan, and interpretation wars of cultural transmission [

26]. De Robertis’ protest performance on May 6, 2024, involved sitting on the floor in front of Courbet’s Origin of the World in a pose that mimicked that of the painting. Chaos ensued and she was arrested. Reactions to de Robertis’ performance question the value and impact of live nudity in performance art, and broadly on nudity in today’s hypersexualized environment.

Delacroix’s painting,

Liberty Leading the People (see

Figure 13), symbolizing the July Revolution of 1830, is tied to the slogan,

Liberté, Fraternité, Egalité. In May 2024, this iconic work was beautifully restored using the latest conservation techniques including AI image technology. Following almost immediately, Delacroix’s painting was attacked by activists.

On May 4, 2024, the climate activist group, Riposte Alimentaire, attacked

Liberty Leading the People at the Louvre, Paris. Delacroix’s persona of

Liberty combines strength and courage with the physical beauty of the female body, that speaks to the desires of an emerging female identity [

27]. In recent years, it has sadly become common for activists to attack iconic art to support their political message.

Saints, Martyrs, and Female Identity

The Martyrdom of Saint Ursula by Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1571–1610) is illustrated in

Figure 14. This was Caravaggio’s last painting, completed in May 1610 [

28]. For her refusal to marry the leader of the Huns (left), kills Saint Ursula with his bow and arrow hitting her where we see her looking with her hands together. Behind her, we see Caravaggio holding her. Ursula became an early Christian martyr who is said to have led a group of 11,000 virgins and became a martyr after she was killed.

The Female Symbol of Medea from the Greek Tragedy by Euripides: Female Rage and Male Betrayal Reinvented Across Time

Medea (Ancient Greek: Μήδεια, Mēdeia), a tragedy by the ancient Greek playwright Euripides was first performed in 431 BC as part of a trilogy. His other plays have not survived. Luigi Cherubini (1760–1842), a leading Italian composer of opera and sacred music, introduced his most successful opera in 1797 based on Medea by Euripides which to present is performed, most notably by the Metropolitan Opera in New York City to enthusiastic audiences. Maria Callas (1923–1977), considered the greatest opera diva of recording history (Diva, another symbol of female identity), is associated with Cherubini’s Medea, which she famously performed at La Scala in Milan, 1953–1961.

The Metropolitan Opera’s 2022 season presented Cherubini’s

Medea which was live streamed across the globe. Below we see Delacroix’s painting of Medea (See

Figure 15), the enduring symbol of the fury of a woman betrayed, seeking revenge by killing her own children, taking us back in time to Medea, 431 BC. A magnificent painting with a horrifying image of Medea killing her children – and yes, such gender wars have continued to be transmitted over the centuries to the present.

Medea, Symbol of Jealousy and Rage: Euripides to Callas to Angelina Jolie

Callas’ performance of Cherubini’s opera

Medea at La Scala in 1953, conducted by Tullio Serafin, and later that year at La Scala with Leonard Bernstein, the first American to conduct at La Scala. Her 1962 performance of Medea signaled her final appearance at Milan’s great opera house. Callas’ dramatic musical moments conducted by Sarafin in 1957 were recorded and are available online. She performs with her leading tenor, Mitro Picchi (see

Figure 16), bringing their unique and powerful interpretation to the world stage [

29].

Cherubini’s Médée (Medea) is based on Pierre Corneille’s 1635 tragedy with homage to Euripides. The Libretto by François-Benoît Hoffman’ was based on Euripides’ tragedy and Pierre Corneille’s play Médée - its original French version was performed in Paris in 1797. The opera is set in the ancient Greek city of Corinth. An Italian translation was first performed in Milan in 1909.

Maria Callas – Symbol of the Opera Diva

The 100

-year anniversary of the birth of Maris Callas in 2023 marked a moment of celebration, admiration and even worship of the greatest operatic voice in recording history [

30]. Callas was born in 1923 and died in 1977.

Fresh Air on Interlochen Public Radio marked the occasion [

31]. Both her live and studio performances of

Medea are part of a 135-disc boxset,

La Divina: Maria Callas In All Her Roles, released for her 100th birthday. The 2022 book

, Cast a Diva: The Hidden Life of Maria Callas, takes a deep dive with key documentary evidence into the symbol of the female opera diva, recognized as the “Diva” of recording history, including the onstage persona and her experiences of heartbreak and loneliness [

32]. To celebrate Maria Callas’s centenary, Greece opened the Maria Callas Museum in Athens, dedicated to her artistic and cultural achievement, housed in a three-story neoclassical building in the center of the city [

33].

Fast forward to 2024, with a new Hollywood film, Callas is front and center in the biographical film, Maria, featuring Hollywood star Angelina Jolie playing Maria Callas. Jolie seems positioned to win an Academy award for her performance. She notes her close personal identification with Callas’ struggles of being an artist and a woman.

Symbols of Female Identity, Motherhood, Madonna and Mother and Child

Struggles around women and identity are being challenged by transgender identity, including one of the most pervasive symbols of female identity – mother and child, motherhood, and pregnancy which ties to

Madonna of the Pink by Raphael and a photograph showing Dr. Kitty Victoria holding her baby, Veena (see

Figure 17). Myths and symbols around female identity are at the core of human heritage and most powerfully depicted in the arts, visual memories, conscious and subconscious, traveling across time and place being reinterpreted and imagined. More recently, the battle between male and female identities has reached a fever pitch. Myths of ancient texts translated across centuries of cultural heritage remain dominant in our 21st-century visual mindscape where digital media conveyed across global platforms supersedes text-based knowing and culture. Buoyed by AI and machine learning, computational culture dominates the means of cultural transmission, while global battles rage over the message.

In 2024, OXH Gallery opened

Receptacle, an exhibition exploring motherhood in which women artists from around the globe consider the complexities of maternity and the body, in Tampa, Florida [

34]:

“The aim of Receptacle is to shift the focus of the research on artist-mothers away from mere work-life balance to a deeper exploration of their experiences. Through themes of social isolation, mental health, and the historical context of art, the show hopes to illuminate how art serves as documentation and self-invention, blurring the lines between privacy and visibility.”

Museum Issues on Cultural Transmission – What’s in, What’s out

The growing crisis in museum fund-raising – so-called patronage – the museum’s old school fundraising rife with upper-class arrogance, has little appeal to the upcoming generation of potential donors – they want to build their own temples to the rising global culture and hardly identify with the ruling class of the “old school” [

35]. Ironically, museums seem unaware of their massive expenditures in areas that concern ways of doing – the entire army of guards could be, for the most part, replaced with an AI security system that for example employs facial recognition and other such technologies. Similarly, collection inventory should move to using AI-empowered apps – general admission should be free, while perhaps charging for new exhibitions. It is now possible to remove the old and tired gallery labels and have these a click away on visitor smartphones. We can organize events that build in a way to enable museumgoers to be participants who can interact and discuss. Perhaps museums can offer visitor labels with names and areas of interest. Just realize that if van Gogh or Salvador Dali were living in New York City, they most likely would not be invited to the donor event for being socially unacceptable. Maybe there are high-end donors out there who would want to sponsor new-style events. It is unclear if museums have addressed these issues. The gap between museum boards and the cultural community is vast, creating additional problems.

Hollywood Is Streaming, AI Tech Culture Beaming

Two powerful forces of our lived experience in the arts, invading our states of consciousness ping-ponging across local to global ecosystems, intertwining real and virtual experiences, is where we live, love and play – the visual soundscape that shapes cultural connections, impacting our interpretations of heritage and its value to contemporary culture.

Further contextualized by the forces of nature are fire, floods, volcanoes, and hurricanes, as our minds and bodies continue to evolve – and humans turn to their spiritual roots most powerfully from the Renaissance, thinking about the human spirit for which the arts, science and technology of Florence, Milan and Rome, are conveyed most powerfully in the work of Leonardo da Vinci – that broadly establishes the revolution of humanism – where the image of God is visualized in the human-like face of Christ, and the mother and child – placing the question of human identity at the forefront of the conscious and subconscious mind, human dreams, imagination and creativity, we see in the context of the Renaissance, where da Vinci’s art stands supreme with the Last supper, the Mona Lisa and Sainte Anne.

Building on the art and science of the Renaissance, and Leonardo’s blending of art, science and technology, with Turing’s work on morphogenesis underscores the central role of nature. We fast-forward to the next revolution of the human spirit made real by the cry for Liberté, Fraternité, and Egalité, ushering in the new republicanism of the French Revolution and the new artistic vision of 19th-century romanticism, as played out in the life of the young genius mathematician Evariste Galois, whose mathematics featured elegance and simplicity, passion and abstract thinking. Alan Turing, the father of computer science and machine intelligence in the 20th century, humanized mathematics by writing on the last page of his 1950 manuscript on Machine Intelligence, “Intelligence as an emotional concept”. This was followed by computer scientists Vint Cerf and Tim Berners-Lee with their innovative work creating the Internet and later the web, leading to the emergence of the digital age of art and science. Meanwhile, luminaries such as Nam June Paik and Andy Warhol, the visionaries who forged the global digital path to the age of AI, ushered in the inclusiveness of pop culture [

36].

The pace of artificial intelligence (AI) and art from 2018 accelerated beyond what humans could have imagined [

9], while introducing the realm of AI big tech taking a dominant position, being further advanced by the Covid pandemic [

2], altering our way of doing, knowing, and being, which now seems irreversible while setting our daily lives in a global ecosystem of real and virtual life merging, and becoming inseparable and where computational arts are permeating all aspects of life while transforming our world of real and virtual human identity.

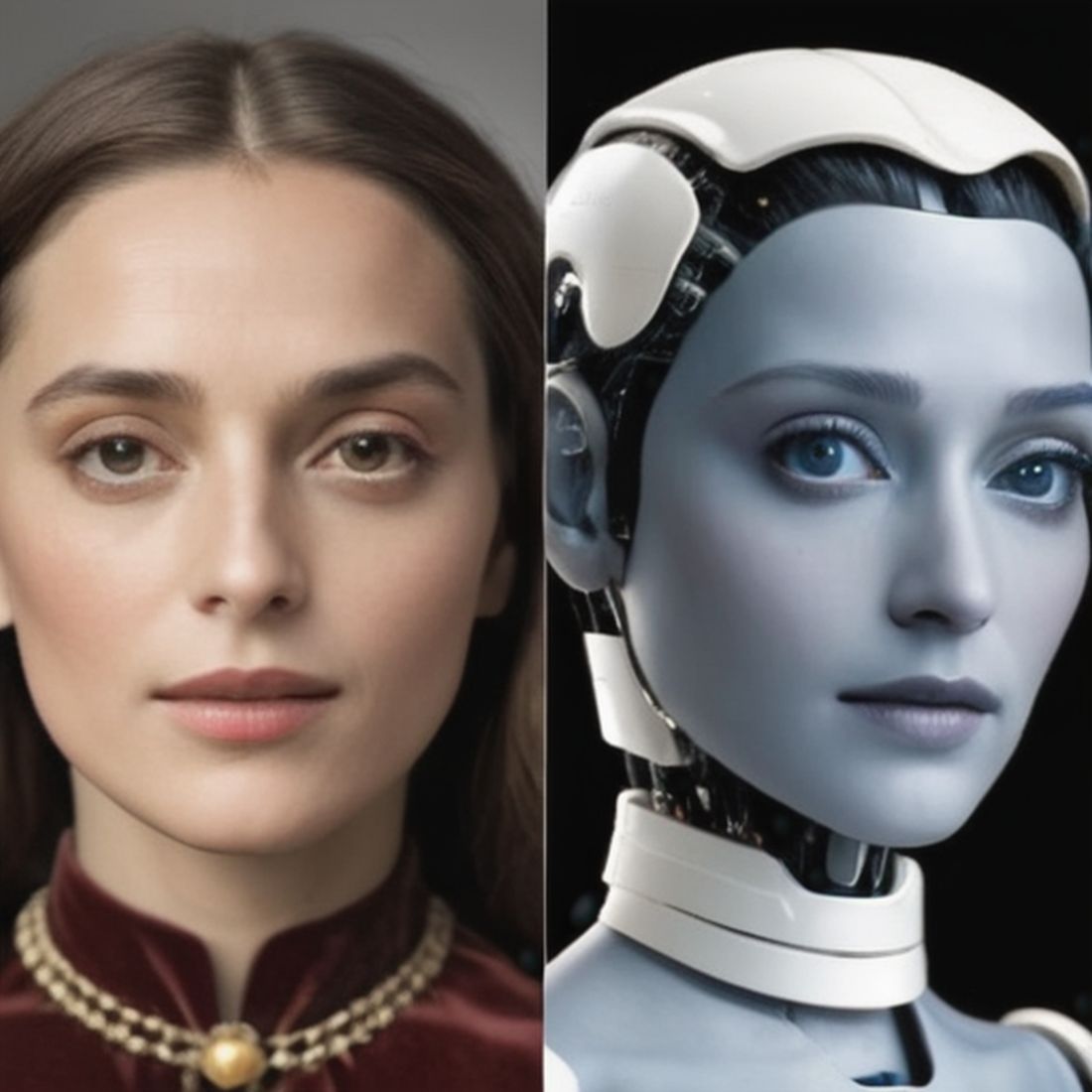

Looking to the future, it is challenging to see how AI will share life with humans. It is as if two species were developing together in a contest about which does what better, each attempting to be more than human but from opposite sides. Humans partner with AI while AI moves toward states of being that are beyond human understanding. It becomes more difficult to distinguish the two and tease out the differences, while we live increasingly in a world at war, which too ties to the struggle between robots, artificial minds, and the human spirit.

Taylor Swift, Singer, and Poet takes the Global Stage by Storm

Taylor Swift’s 2024 album

The Tortured Poets Department looks back in time. According to

People Magazine, based on ancestry records, she is related to the 19th-century American poet, Emily Dickenson (1830–1886), born in Amherst, MA (see

Figure 18).

Swift’s song,

Majorie, the one she performed in Minneapolis, Minnesota during her Eras Tour at a 2023 concert refers to Marjorie Moehlenkamp Finlay (1928–2003), who was an American opera singer and television personality. (See a sample of the lyrics of

Marjorie below). A coloratura soprano, Finlay performed concert and opera singing. After winning a talent contest in 1950, she toured on the ABC radio network show

Music With the Girls. She is the maternal grandmother of singer-songwriter Taylor Swift, who dedicated her songs “Marjorie” and “Timeless” to her [

37]. Although Swift uses her half-naked appearance to win over her audience, her talents in composing, singing, dancing, and poetry shine through.

You’re alive, so alive

And if I didn’t know better

I’d think you were singing to me now

If I didn’t know better

I’d think you were still around

I know better

But I still feel you all around

I know better

But you’re still around

It has also been shown that Taylor Swift and the legendary American poet Emily Dickinson (1830–1886) are related. Swift and Dickinson are sixth cousins, three times removed according to the

Ancestry website [

39].

5. Threading Past to Present

People forget, rewrite, and re-narrate the past – memories of heritage history and meaning fade. Consider heritage in the context of politics, genocides of “the past” and the destruction of heritage that captured human identity over centuries. What does it mean, and what does it look like to be English, French, Hebrew, etc., as we contemplate cultural identity, a powerful force in human relationships and emotions. The melting pot, a type of universal identity, is fading under the weight of cultural identity wars in an overwhelmingly global environment. The critical importance of history becomes more a question of whose history is being considered.

Figure 19 shows Maggi Hambling’s

A Sculpture for Mary Wollstonecraft, unveiled in 2020 on Newington Green, north London, as the world’s first memorial to the British feminist pioneer, writer, and philosopher, Mary Wollstonecraft (1759–1797). Social media exploded with debate around this long-awaited statue of the feminist trailblazer [

40]. The sculpture was the result of a decade-long campaign to honor the 18th-century women’s rights advocate.

Technology and Heritage Transmission

From Andy Warhol to Maria Callas, new technology has played a key role in heritage transmission over time, marking significant moments of new conceptualizations. Its story and history that threads iconic personas of human identity across time tend to reinvent them. Here we note Warhol, Lennon, Ono, Bernstein, and new music of the 1970s, while Callas, the renowned opera diva of that period, transmits the musical heritage of opera of the 19th and 20th centuries via digital recordings. These convey human history over centuries from Greek tragedy to Shakespeare’s leading women who ended their lives in tragic deaths – for example, Ophelia in Hamlet, and Juliet in Romeo and Juliet.

Cultural Translation Across Time and Technology: Poetry, Art and Music

The Geneva-based artist RVig was awarded the ABS prize for a digital artwork inspired by the 19th-century French poet Charles Baudelaire, pointing to Baudelaire’s poetry in

Les Fleur du Mal as his inspiration [

41]. In this sense, the artist RVig has a relationship with Baudelaire (see

Figure 20). Each of Baudelaire’s 126 poems is transcribed on a ribbon, the course and color of which evolves depending on the content of the text.

Symbolism, as defined by Baudelaire’s Les Fleurs du Mal (“The Flowers of Evil”), and later, Arthur Rimbaud’s La Saison en Enfer (“A Season in Hell”), who prophetically wrote: Un soir, j’ai assis la Beauté sur mes genoux – Et je l’ai trouvée amère. – Et je l’ai injuriée. (Translation: One evening, I sat Beauty on my knees – and I found her bitter – and I insulted her), has been inspirational to later cultural icons. For example, Rimbaud similarly inspired artists like Jim Morrison and Bob Dylan.

In the firmament of influencing hearts and minds, are not the “influencers” associated with the arts – those whose work emerges as omnipresent and sustained, and yet transforming over time? Warhol is such an artist in the way he almost singlehandedly establishes pop art, himself being influenced by the American culture of the 1960s, swayed by the emergence of Hollywood films and then television, while fine artists did not see these media as cultural artifacts of their time – but rather commercial entertainment. With the culture of Hollywood superstars as Marilyn Monroe, connecting to international audiences; they became icons of female beauty and sexuality.

Heritage sites evoke memories and interpretations of the past that particularly since 2020 are often under attack, while new narratives are assigned that cast negative representations especially of public sculpture encouraging removal and or destruction and replacement, bringing focus to the symbolic nature of the arts. On the other hand, artists referential to and influenced by artists past, take on the mantle of cultural transmission, translated through their imagination and new ways of seeing in the present.

Symbols of the Feminine Mystique and Gender in Translation: Adam and Eve, Joan of Arc and Ophelia

Figure 21,

Figure 22 and

Figure 23 provide examples of artworks that include aspects of feminine mystery in various facets of cultural influence.

The Arts East to West Define Human Gender that Persists to Present, at the Heart of Cultural Heritage

The lion’s share of iconic images by artists of Greece, Rome, and the Renaissance symbolize the nature of male and female identity and gender-defining masculinity in dominance and strength, and femininity as beauty, sexuality, and weakness, as well as traits associated with revenge and rage of betrayal. These sexual symbols are conveyed powerfully through mythology and the Bible and dominate painting and representational art to present leaving women trapped in a conflicted identity, between good and evil – for example, Medea, Medusa, Olympia, and Juliet, giving way to sayings as “if looks could kill (Medusa) “deadly attraction” etc. Human cultural heritage is steeped in the “battle of the sexes” – and we are currently in such a moment of conflict and confusion.

The scale of the current cultural struggle over gender identity – what is a man? – what is a women? – is unparalleled. The “norm” is being challenged – images in the arts of same-sex couples being affectionate remain rare, while contentious, one might say, part of culture wars, real and virtual.

Medea – Passionate Love Turns to Passionate Hate

Medea, an enduring symbol of extreme human emotions that challenges mental states of being, sets the stage for Martha Graham’s 1946 work Cave of the Heart. A 2017 performance at the Teatro Royal, Madrid, uses original sets by Isamu Noguchi and music by the American composer, Samuel Barber (1910–1981), adapted from Beverly Emmons Premiere, May 10, 1946, at Columbia University in New York City, for which Graham’s Medea has been interpreted by Xin Ying.

Human Identity and Creativity expressed in Routine Patterns of Life, Now Dominated by Computer Devices

Routine by T. Giannini (2024)

Routine

Makes life seem

as if it goes on forever

The unforeseen

Disrupts the expected

Life intercepted

uncorrected

Reflected

in mirrors of the mind

Be kind to the past

Will memories last

Routine broken

Words unspoken

Love’s a token

of time together

Ironically, at the very time that AI, science, and technology are moving forward at unprecedented speed operating in the global Technosphere with millions of participants, human identity, gender, and cultural connections are at the top of the mind, and are more prominent and contentious than ever. This is while new AI tools can be seen to empower individuals to be more creative and expressive, and participate as artists and learners. And yet, we take our cues about self from our cultural past threading it through to the present day, with help from global platforms making arts and culture increasingly available to view. How can we escape from this routine (see

Figure 24)?

A 2024 exhibition at Tate Britain,

Now You See Us, focused on women artists and their struggle for recognition and respect, and ways art confronts sexism and dominance of male artists [

44]. Yes, we see these women artists at the Tate, but once the show ends, then what? The question and issues return to one of female identity, the ingrained image of women from the Ancient Greeks and Romans, through its many iterations to the present.

Hollywood Stories, Lady Gaga and Refik Anadol: The Disney Effect on the Global Stage

A preview of the film,

The Joker: Folie A Deux, starring Lady Gaga, was filmed at the Louvre in Paris, to the chagrin of many Louvre aficionados because it shows Gaga putting lipstick on the mouth of the

Mona Lisa, giving her a smile [

45]. She pulls out her lipstick and draws a smile on the

Mona Lisa – not quite an homage to Leonardo da Vinci. A key moment is when Lady Gaga sings the lyrics, “the Joker is me”, a powerful statement of a great female singer taking on a role associated with male identity (see

Figure 25).

From Disneyland to Dataland, Refic Anadol announced the opening of Dataland in Los Angeles for 2025. The website highlights a key goal, “Where human imagination meets the creative potential of machines”, featuring AI as its creative force [

46].

6. The Female Image

Gustave Klimt and Female Imagery

Klimt’s cross-cultural inspiration and vision of male and female human identity permeates his art from Japanese prints, the motifs of Egyptian mythology and Byzantine iconography, and its use of gold leaf for spiritual evocations as did Klimt, as we see in his magnificent rendering of

Judith (1901) and his most famous painting,

The Kiss, expanding our notions of impressionism in a modernist context (see

Figure 26). 21st-century cultural identity à la Klimt more than ever resonates with contemporary cultural heritage reinterpreted and freshly narrated in new cultural contexts as it swirls across the globe via Internet platforms infused with AI apps and code. Klimt loved the female figure and visits to Italy fueled his fascination with gold [

47]:

“All art is erotic,” Klimt once wrote, and his work, as a whole, undeniably delights in the raptures of the female figure (Klimt was a notoriously amorous man, and had at least 14 children in his lifetime through hushed affairs).”

“Klimt had an omnivorous artistic appreciation, embracing the flatness of Japanese prints, the motifs of Egyptian mythology, and Impressionist’s modernism.”

“When it came to his passion for gold, religious iconography of the Byzantine era came to the fore. In 1903, Klimt took pivotal trips to Venice and (twice) to Ravenna, Italy.”

The Female Symbol of Medusa

Medusa, from the ancient Greek myth, is generally described as a woman with living snakes in place of hair; her appearance is so hideous that anyone who looks upon her is turned to stone (see

Figure 27). It is interesting to note that contemporary artists and filmmakers still find Medusa a compelling theme [

48].

Afghan Women, 1st Century to 2024 – The Ideation of the Barbie Aesthetic and Fashion

A 1st-century sculpture of an Afghan goddess reveals a feminine persona persistent in the forefront of 21st-century culture: eye makeup, lip color, coiffed hair, lowcut neckline and necklace, large breasts, tiny cinched waist compared to her hips, and slim jeweled wrists (see

Figure 28). Her grace and beauty seem anathema to Afghan women today whose identity has been erased by the Taliban decree (see

Figure 29), documenting its increasing brutality towards women [

49].

Expressed in the Afghan law on women’s rights is that women should not be seen or heard (see

Figure 30) [

51]. Meanwhile, more than 22,000 ancient cultural treasures originating from Afghanistan have been moved from their hiding places and inventoried for their safety [

50]. With almost half of Afghanistan’s population of 43 million being female, the world looks on while 20 million women have been erased, justified by literal translations of mythological symbols of female identity such as Medusa, Medea, and femme fatale.

Hollywood’s Ode to Castrati: Women Should Not Be Seen nor Heard

Expressed in the Afghan law on women’s rights is that women should not be seen nor heard, as we see in England when castrati sang the female roles, famously in the example of Handel’s opera

Rinaldo. Handel’s opera aria

Lascia ch’io pianga from

Rinaldo, composed in 1711 was performed for his adoring London audience. In 1994, the aria was featured in the Hollywood Sony Classics film

Farinelli, based on the life of a 1eading 19th-century castrato who used the stage name Farinelli, the most famous castrato of his time. The

Farinelli film won a Golden Globe award and was distributed globally [

52].

The Femme Fatale – Symbol of Dangerous and Deadly Beauty

Symbolism in painting and the femme fatale is another characterization of female beauty as dangerous – a duality of identity and being, that permeates male thought and feeling to justify shunning or excluding women, constituting a difficult or impossible challenge for women to face in dealing with self in society, mostly controlled by men [

53,

54].

Modern Artists, Edvard Munch and Pablo Picasso Interpret the Madonna

Madonna by Edvard Munch (see

Figure 31, left) was on view at the exhibition

Femme Fatale: Gaze – Power – Gender at the Hamburger Kunsthalle, 2022–2023, curated by Dr. Markus Bertsch [

55,

56]. Munch produced a number of versions of this image, including many drawings (e.g., see

Figure 31, right). Around 1916, Munch wrote [

57]:

“A pause when the word stops revolving. Your face encompasses the beauty of the whole earth. Your lips, as red as ripening fruit, gently part as if in pain. It is the smile of a corpse. Now the hand of death touches life.”

In the above description of the Madonna, a young, nude woman with a red halo over her head, Munch evokes a combination of death and sex, as well as sacred and profane issues. Munch transforms his Madonna from a nude femme fatale to a Vampire, showing that these female symbols flow one into the other, as they do in the male imagination, making women victims of male projection of their fears and desires (see

Figure 32) [

58].

Pablo Picasso deeply engaged with the subject of mother and child throughout his life by way of his paintings as seen in the works above,

Figure 33 (left),

Maternité, 1901, from his blue period to the surreal expressionism of

Figure 33 (right), illustrating his 1971

Motherhood with Apple. The 1901 painting became the victim of a crime, being physically assaulted by two political protestors in 2024 at the National Gallery, London, obliterating Picasso’s image with an image of their own depicting a Gazan mother and children, thus risking the destruction of cultural heritage [

59].

Symbolism – Images of the Mind and Heart Beyond Realism

The symbolist movement has its roots in France with the symbolist poets, Charles Baudelaire, Arthur Rimbaud, and Paul Verlaine, interpreted most prominently by painters Gustave Klimt, Odilon Redon, and Edvard Munch. Symbolism emerging in the late 19th century tied closely with Surrealism, and memorialized in the 1924 Manifesto of poet André Breton, tied to movements in art that rejected realism. The critic Jean Moréas (1856–1910) introduced the term symbolists to distinguish them and published the Symbolist Manifesto (Le Symbolisme) in Le Figaro on September 18, 1886, identifying Baudelaire, Rimbaud and Verlaine, as the movement’s leaders.

7. Conclusion – Culture Streaming the Globe

Since 2018, computing and AI computational technology have been advancing at unprecedented speed on the global stage, where we see a sharp rise in human adoption of digital devices by billions of people, their messages blanketing the Technosphere, reaching frenzied levels of interaction. With Hollywood digital content rapidly shifting to streaming and YouTube, Hollywood has become more a concept than a place. In sharp contrast, the male and female personas, and the stories they tell reflect the aesthetics and roles of female and male stars, which are being conveyed through the lens of cultural heritage and art, which have changed little from the arts of the Renaissance onwards, a situation that has deep consequences, particularly for women. Women as victims of sexual assault is on the rise and often involves stars of the arts and entertainment. Kanye West said about his choking and gagging the model Jenn An, “This is art. This is f--king art. I am like Picasso.” [

61].

According to

The Hollywood Reporter in October 2024, the influence of social media is beginning to challenge the Hollywood film industry’s dominance, saying, “Hollywood, meet your new A-List.” There were no actors in the accompanying photograph. Featured instead were TikTokers and Instagram “influencers” who function primarily as infomercial salespeople [

62]. Tik Tok and social media influencers are now entwined with the Hollywood crowd as an accepted source of new star talent and diversity.

In terms of equal representation of males and females in film, it is not a question of how many women versus the number of men, it is more a question of the female identities represented. For example, one male versus a harem – so the metrics for determining equality should reflect the roles of males and females. And yes, women of the highest status and income, such as Beyoncé and Kardashian, place high importance on their female identity and sexual appeal featuring their body’s form – popping breasts, tiny waist, long shapely legs dressed up in the classical Barbie mermaid dress. Thus, given the complexity of female identity – despite her talent, in the first instance, she needs to meet the physical attributes and play the associated role vis à vis her male counterpart. Noticeably, women surpass men in the number of assaults they suffer as victims – rapes, stabbings, shootings, kidnappings, murders, mutilation, sex trafficking, slavery, etc.

The more attractive a woman is, the more likely a male predator is to say “she was asking for it” – which seems to invoke the symbol of the femme fatale. Consider that 85% of crime victims are women. Also noted is that some 75% of fatal victims of domestic violence are women and that “Nearly every 1 in 2 women in the United States will face physical violence from an intimate partner at some point in their lives [

63].

The many facets of female identity portray a complex image, and certainly not an either or. Women struggle with these oppositions – as they strive to embrace their beauty while developing their intellectual, artistic, and creative talents in a range of fields, recognizing the central role art and artists play in the conceptualization of the self. Human identity, male and female, as viewed here through the lens of the arts and heritage in our journey across 2,500 years suggests new ways to take important steps forward for both women and men to chart a new path toward seeking greater equality and understanding of gender identity as a lived experience, recognizing the powerful influence of cultural heritage, a matter of history, DNA, genes, art, and imagination. The separation between real and virtual life is slipping away as our digital devices mediate most of life’s activities with Hollywood at the helm, where the mediation is also the message, the instructions, and the images of the mind’s eye – our lifeline to the world and ourselves. The choice to opt out or let go seems no longer available.

On the other hand, people are increasingly gaining greater access to streaming platforms as the range and power of digital tools designed for use by millions of people grows exponentially, giving them a voice as players and participants in the arts and culture. Looking back to the Renaissance and forward to the present, cultural heritage expressed in painting and sculpture to digital art on computational platforms, continues to focus on human form and identity, male and female, which accounts for some 75% of arts production. With the steady rise of human use of AI at home, and at the office, feelings of loneliness and isolation have become key issues to the art of love and life, to fewer woman choosing motherhood, as the number of abortions show dramatic increase, while robots and chatbots advance and multiply. Over the past few years, the age of AI has advanced rapidly and beyond expectation. On the other hand, as this study illustrates, cultural transmission of human identity and gender has stayed the course from 2,500 BCE to the 21st century creating two highly distinctive paths. One about the development of technology, the other, human identity and gender, male and female across time and place. What is relatively new is that millions of people now have access to the Internet and Web, and most recently, global streaming and social media where Hollywood dominates arts and culture on the silver screen. Yet gender wars have little advanced from their historical and symbolic roles enumerated in this study – as not a day goes by lacking examples of abuse, regardless of class, profession or wealth despite new levels of access to arts and information. Thanks to global neural networks, platforms, and interactive participatory media, hopefully cultural transmission across the global stage powered by AI platforms will ameliorate human identity and gender conflict tied to cultural heritage wars.

Culture wars destroying human heritage are intensifying especially in in the Middle East, Syria, Ukraine and Russia, while at the same time, culture conflict on city streets, are causing human death tolls to rise alongside the loneliness and isolation of losing a loved-one [

4]. The hope is that AI tools and global interaction will shed new light on love and understanding –

but when(see

Figure 36)?

But When by T. Giannini (2024)

When your loved one dies

Cries of grief

Disbelief

Transfer to your paralyzed body

Unrealized hope

The scope of life

Sliced in two

I love you

I knew who you were

From outside in

Can life begin again

But when

Waiting for a sign

You’re no longer mine

I’m lost in the deep ocean

Of my mind’s devotion

Will I find love again

But when

Looking out

Into space

No trace of life

Lost in an expanding void

Lonely and paranoid

Can I hide the pain

Can I love again

But When

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.G. and J.B.; methodology, T.G.; formal analysis, T.G. and J.B.; investigation, T.G.; resources, T.G. and J.B.; writing—original draft preparation, T.G. and J.B.; writing—review and editing, J.B. and T.G.; project administration, J.B.; funding acquisition, T.G. and J.B. Both authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Jonathan Bowen is funded by the UK Universities Superannuation Scheme (USS).

Acknowledgments

Jonathan Bowen received support and additional funding from Museophile Limited. Recent EVA London conference papers on Electronic Visualisation and the Arts (e.g., [37,42]) have been inspirational for the background of this paper. Finally, thank you to the reviewers for their help in improving this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

-

The Arts and Computational Culture: Real and Virtual Worlds. Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Springer Series on Cultural Computing. Giannini, T.; Bowen, J.P. (Eds.). [CrossRef]

- Giannini, T.; Bowen, J.P. Museums and Digital Culture: From reality to digitality in the age of COVID-19. Heritage. 2022, 5(1), 192–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannini, T.; Bowen, J.P. Computational Culture: Transforming Archives Practice and Education for a Post-Covid World. ACM Journal on Computing and Cultural Heritage 2022, 15, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannini, T.; Bowen, J.P. Global Cultural Conflict and Digital Identity: Transforming Museums. Heritage. 2023, 6(2), 1986–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addicoat, M. Google Deepmind founder shares Nobel prize in chemistry for AI that unlocks the shape of proteins. The Conversation, October 9, 2024. Available online: https://theconversation.com/google-deepmind-founder-shares-nobel-prize-in-chemistry-for-ai-that-unlocks-the-shape-of-proteins-240921 (accessed on December 8, 2024).

- Jowett, P. Growth opportunity for creative industries from venture capital, study finds. Arts Professional, October 16, 2024. Available online: https://www.artsprofessional.co.uk/news/growth-opportunity-for-creative-industries-from-venture-capital-study-finds (accessed on December 28, 2024).

- PEC. Growth Finance for Creative Industries. Policy and Evidence Centre, Newcastle University, UK, October 16, 2024. Available online: https://pec.ac.uk/state_of_the_nation/growth-finance-for-the-creative-industries/ (accessed on December 28, 2024).

- Halperin, J. What Really Happened in the Art Market in 2023? Artnet, March 20, 2024. Available online: https://news.artnet.com/market/intelligence-report-year-ahead-2024-data-dive-2453162 (accessed on December 28, 2024).

- Machado, P.; Romero, J.; Greenfield, G. (Eds.) Artificial Intelligence and the Arts:Computational Creativity, Artistic Behavior, and Tools for Creatives. Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Computational Synthesis and Creative Systems. [CrossRef]

- McMurtrie, B. Is This the End of Reading? Chronicle of Higher Education, May 9, 2024. Available online: https://www.chronicle.com/article/is-this-the-end-of-reading (accessed on January 1, 2025).

- Bowen, J.P.; Copeland, B.J. Turing, Warhol, and Monroe: Development of The Turing Guide cover. In EVA London 2024: Electronic Visualisation and the Arts, London, UK, 2024; J. P. Bowen, J. Weinel, A. Borda, Ed.; BCS: Swindon, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, N. Andy Warhol Portraits: A Definitive Guide. Artland Magazine, August 29, 2024. Available online: https://magazine.artland.com/andy-warhol-portraits-a-definitive-guide/ (accessed on January 1, 2025).

- Commodore Computer Museum. Andy Warhol and his Commodore Amiga (footage with Debbie Harry). YouTube, 2023. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GVuS0K9cBi0 (accessed on January 1, 2025).

- Friedman, V. Old School Glamour at the Met Gala of the West Coast. The New York Times, October 21, 2024. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2024/10/21/style/academy-museum-gala-best-dressed.html (accessed on January 1, 2025).

- IMDb. David and Goliath. IMDb, 2016. Available online: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt4352408/ (accessed on January 3, 2025).

- White, K. Was Botticelli’s Famed ‘Birth of Venus’ a Fertility Symbol? Artnet News, July 11, 2024. Available online: https://news.artnet.com/art-world-archives/botticellis-the-birth-of-venus-3-things-2507805 (accessed on January 1, 2025).

- Kinsella, E. Andy Warhol’s Computer Portrait of Debbie Harry Goes on Sale for a Cool $26 Million. Artnet, August 2, 2024. Available online: https://news.artnet.com/market/warhol-amiga-debbie-harry-portrait-for-sale-2520022 (accessed on January 1, 2025).

- Yerebakan, O.C. Andy Warhol’s filmed portraits of celebrities head to Hollywood. The Art Newspaper, February 12, 2024. Available online: https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2024/02/12/warhol-celebrity-portraits-screen-tests-christies-los-angeles-frieze (accessed on January 1, 2025).

- The Warhol. Warhol and the Amiga – July 25, 2017 – November 1, 2019. The Andy Warhol Museum, 2017. Available online: https://www.warhol.org/exhibition/warhol-and-the-amiga/ (accessed on January 1, 2025).

- The Andy Warhol Diaries. Warner Books, 1989. Warhol, A.; Hackett, P. (Eds.).

- McAllister, M. Andy Warhol & Selfies. The Andy Warhol Museum, December 20, 2015. Available online: https://www.warhol.org/andy-warhol-selfies/ (accessed on January 1, 2025).

- Cassady, D.; Shotgun the Warhol: Christie’s to sell Shot Sage Blue Marilyn for $200m. The Art Newspaper, 21 March 2022. Available online: https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2022/03/21/shotgun-the-warhol-christies-to-sell-shot-sage-blue-marilyn-for-pound200m (accessed on January 1, 2025).

- Netflix. The Andy Warhol Diaries. IMDb, 2022. Available online: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt18082212/ (accessed on January 1, 2025).

- Li, J.; Bowen, J.P. Female Self-presentation through Online Dating Applications. In EVA London 2022: Electronic Visualisation and the Arts, London, UK, 2022; J. P. Bowen, J. Weinel, A. Borda, Ed.; BCS: Swindon, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapart, J.; L’exposition Lacan rassemble des œuvres de Dali, Courbet et Vélasquez. Centre Pompidou-Metz, December 2023. Available online: https://tout-metz.com/centre-pompidou-metz-exposition-lacan-rassemble-oeuvres-dali-courbet-velasquez-2023-845637.php (accessed on January 1, 2025).

- Azimi, R. Deborah de Robertis scandal divides art world. Le Monde, June 3, 2024. Available online: https://www.lemonde.fr/en/culture/article/2024/06/03/deborah-de-robertis-scandal-divides-art-world_6673663_30.html (accessed on January 1, 2025).

- Ho, K.K. Two Activists Arrested After Sticking Posters Around “Liberty Leading The People” Painting at the Louvre. Art News, May 9, 2024. Available online: https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/louvre-museum-paris-protest-eugene-delacroix-painting-1234705732/ (accessed on January 1, 2025).

- Miller, C. Caravaggio’s Last Painting: The Martyrdom of Saint Ursula. Daily Art Magazine, November 1, 2024. Available online: https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/caravaggios-martyrdom-of-saintt-ursula/ (accessed on January 1, 2025).

- CallasFan. Maria Callas – Medea Finale, Studio Fantastic Sound. YouTube, 2012. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RyvenB0lrpU (accessed on January 1, 2025).

- Spence, L. The Final Days of Maria Callas. Volta Magazine, May 1, 2024. Available online: https://voltamagazine.com/the-final-days-of-maria-callas/?lang=en (accessed on January 1, 2025).

- Schwartz, L.; ’Fresh Air’ marks the 100th birthday of legendary opera soprano Maria Callas. Fresh Air, Interlochen Public Radio, October 25. 2023. Available online: https://www.interlochenpublicradio.org/2023-10-25/fresh-air-marks-the-100th-birthday-of-legendary-opera-soprano-maria-callas (accessed on January 1, 2025).

- Spence, L. Cast a Diva: The Hidden Life of Maria Callas. The History Press, 2022.

- Maltezou, R. Greece opens Maria Callas museum for a glimpse into opera diva’s life. Reuters, October 26, 2023. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/greece-opens-maria-callas-museum-glimpse-into-opera-divas-life-2023-10-25/ (accessed on January 1, 2025).

- OXH Gallery. OXH Gallery Debuts an Exhibition Exploring Motherhood. Hyperallergic, May 16, 2024. Available online: https://hyperallergic.com/914982/oxh-gallery-debuts-exhibition-exploring-motherhood/ (accessed on January 1, 2025).

- Halperin, J. The hangover after the museum party: institutions in the US are facing a funding crisis. The Art Newspaper, January 1, 2024. Available online: https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2024/01/19/us-museums-funding-crisis-new-generation (accessed on January 1, 2025).

- Art World. Nam June Paik and History of Video Art. Artdex, 2023. Available online: https://www.artdex.com/nam-june-paik-and-history-of-video-art/ (accessed on January 1, 2025).

- Bowen, J.P.; Giannini, T.; Borda, A.; Mason, C. Computation, AI, and Creativity. In EVA London 2024: Electronic Visualisation and the Arts, London, UK, 2024; J. P. Bowen, J. Weinel, A. Borda, Ed.; BCS: Swindon, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swift, T. Marjorie. SongMeanings, 2020. Available online: https://songmeanings.com/songs/view/3530822107859605224/ (accessed on January 1, 2025).

- Hatcher, K. Taylor Swift and Poet Emily Dickinson Are Related, Ancestry Reveal. People Magazine, March 4, 2024. Available online: https://people.com/taylor-swift-poet-emily-dickinson-related-ancestry-reveals-8603638 (accessed on January 1, 2025).

- Jhala, K. Twitter explodes with debate around long-awaited statue of feminist trailblazer Mary Wollstonecraft. The Art Newspaper, November 10, 2020 Available online:. Available online: https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2020/11/10/twitter-explodes-with-debate-around-long-awaited-statue-of-feminist-trailblazer-mary-wollstonecraft (accessed on January 1, 2025).

- Jebb, L. As winner of renamed ABS Digital Art Prize is announced, have we reached a turning point for conversations around NFTs and culture? The Art Newspaper, June 24, 2024. Available online: https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2024/06/24/as-winner-of-renamed-abs-digital-art-prize-is-announced-have-we-reached-a-turning-point-for-conversations-around-nfts-and-culture (accessed on January 1, 2025).

- Giannini, T.; Bowen, J.P. Generative Art and Computational Imagination: Integrating poetry and art. In EVA London 2023: Electronic Visualisation and the Arts, London, UK, 2023; J. P. Bowen, J. Weinel, G. Diprose, Ed.; BCS: Swindon, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RVig. “Les Fleurs du Mal”, Generative Art, 3min. RVig Generative Art, YouTube, 2021. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dZISyH-yHbY (accessed on January 1, 2025).

- Lawson, J. Revealed: The Sensational Lives of 6 Overlooked British Women Artists. Artnet News, September 21, 2024. Available online: https://news.artnet.com/art-world/women-artists-tate-britain-2525667 (accessed on January 1, 2025).

- Musée du Louvre. Joker Folie à Deux x Louvre | Lady Gaga, Mona Lisa. YouTube, 2024. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kWaRCCfbJpE&t=21s (accessed on January 2, 2025).

- Gelt, J. Dataland, the world’s first AI arts museum, will anchor the Grand complex in downtown L.A. MSN, September 24, 2024. Available online: https://www.msn.com/en-us/news/technology/dataland-the-world-s-first-ai-arts-museum-will-anchor-the-grand-complex-in-downtown-l-a/ar-AA1r6WXV (accessed on January 2, 2025).

- White, K. The Surprising Backstory Behind Gustav Klimt’s Obsession With Gold. Artnet News, October 1, 2024. Available online: https://news.artnet.com/art-world-archives/gustav-klimt-gold-2543498 (accessed on January 2, 2025).

- Steer, E. Why are artists obsessing over Medusa? Plaster Magazine, October 20, 2023. Available online: https://plastermagazine.com/articles/medusa-contemporary-art-muse/ (accessed on January 2, 2025).

- Mazurana, D.; Samar, S. How the Taliban’s new ‘vice and virtue’ law erases women by justifying violence against them. The Conversation, September 30, 2024 Available online:. Available online: https://theconversation.com/how-the-talibans-new-vice-and-virtue-law-erases-women-by-justifying-violence-against-them-239159 (accessed on January 2, 2025).

- NBC. Afghan treasures emerge from hiding places. NBC News, November 18, 2004. Available online: https://www.nbcnews.com/id/wbna6522609 (accessed on January 2, 2025).

- Ahmadi, B.; Richer, J.; Baggerman, J.; Byrd, W.; Worden, S. Where is Afghanistan Three Years into Taliban Rule? US Institute of Peace (USIP), September 19, 2024. Available online: https://www.usip.org/publications/2024/09/where-afghanistan-three-years-taliban-rule (accessed on January 2, 2025).

- Farinelli1. Handel – Lascia ch’io pianga. YouTube, 2018. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TqdFoRjL1Bk (accessed on January 2, 2025).

- Manioudaki, A. Mythological Femmes Fatales in Mysterious Symbolist Paintings. Daily Art Magazine, September 19, 2024. Available online: https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/symbolist-mythological/ (accessed on January 2, 2025).

- Mirchandani, R.; Jeffrey, L. Femme Fatale – A shroud of mystery and beauty, she traps all who fall victim to her charms. C Magazine, December 18, 2023. Available online: https://cmagazine.org/2023/12/18/femme-fatale/ (accessed on January 2, 2025).

- Bunyan, M. Exhibition: ‘Femme Fatale: Gaze – Power – Gender’ at the Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg. Art Blart, April 6, 2023. Available online: https://artblart.com/tag/the-femme-fatale-in-symbolist-art/ (accessed on January 2, 2025).

- Teverson, M. Female Rage in Art. Daily Art Magazine, Daily Art Magazine, May 6, 2024. Available online: https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/female-rage-in-art/ (accessed on January 2, 2025).

- Art Institute of Chicago. The Femme Fatale. Becoming Edvard Munch: Influence, Anxiety, and Myth, The Art Institute of Chicago, 2013. Available online: https://archive.artic.edu/munch/femme_fatale/ (accessed on January 2, 2025).

-

Anon; Provost, E. Edvard Munch’s Vampire: A Scary Femme Fatale or a Tender Lover? Daily Art Magazine, December 12, 2024. Available online: https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/edvard-munchs-vampire-a-scary-femme-fatale-or-a-tender-lover/ (accessed on January 2, 2025).

- Kelly, P. Two arrested after Picasso painting targeted by protestors at London’s National Gallery. The Art Newspaper, October 10, 2024. Available online: https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2024/10/10/two-arrested-after-picasso-painting-targeted-by-protestors (accessed on January 2, 2025).

- Diamond, M.L. As Hollywood and Netflix descend on NJ, they need more hotels like the Molly Pitcher Inn. Asbury Park Press, October 7, 2024. Available online: https://www.app.com/story/money/business/2024/10/07/fort-monmouth-netflix-studio-film-productions-in-nj-need-hotels/75346552007/ (accessed on January 2, 2025).

- Archiki, L. Former ‘Next Top Model’ Contestant Accuses Kanye West of Choking and Gagging Her. The Daily Beast, November 23, 2024. Available online: https://www.thedailybeast.com/former-next-top-model-contestant-jennifer-an-accuses-kanye-west-of-choking-and-gagging-her/ (accessed on January 2, 2025).

- Bateman J (2024) Hollywood is dead, according to Justine Bateman. Here’s what comes next. Fast Company, November 2, 2024. Available online: https://www.fastcompany.com/91220089/hollywood-is-dead-according-to-justine-bateman-heres-what-comes-next (accessed on January 2, 2025).

- Wisniewska, M.J. Domestic Violence Statistics 2024. Break The Cycle, December 7, 2024. Available online: https://www.breakthecycle.org/domestic-violence-statistics/#What-Percentage-of-Domestic-Violence-Victims-Are-Female?- (accessed on January 2, 2025).

Figure 5.