We investigated 14 distinct layer pruning strategies, organized into six categories, activation, mutual information, gradient, weight, attention, and strategic fusion, alongside a random pruning baseline. We evaluated each strategy using nine datasets. This section presents how each strategy reduces model size while retaining (or even surpassing) performance, and highlights the advantages of integrating multiple layer-specific signals in a unified pruning framework.

3.1. Strategic Fusion Optimizes Model Compression

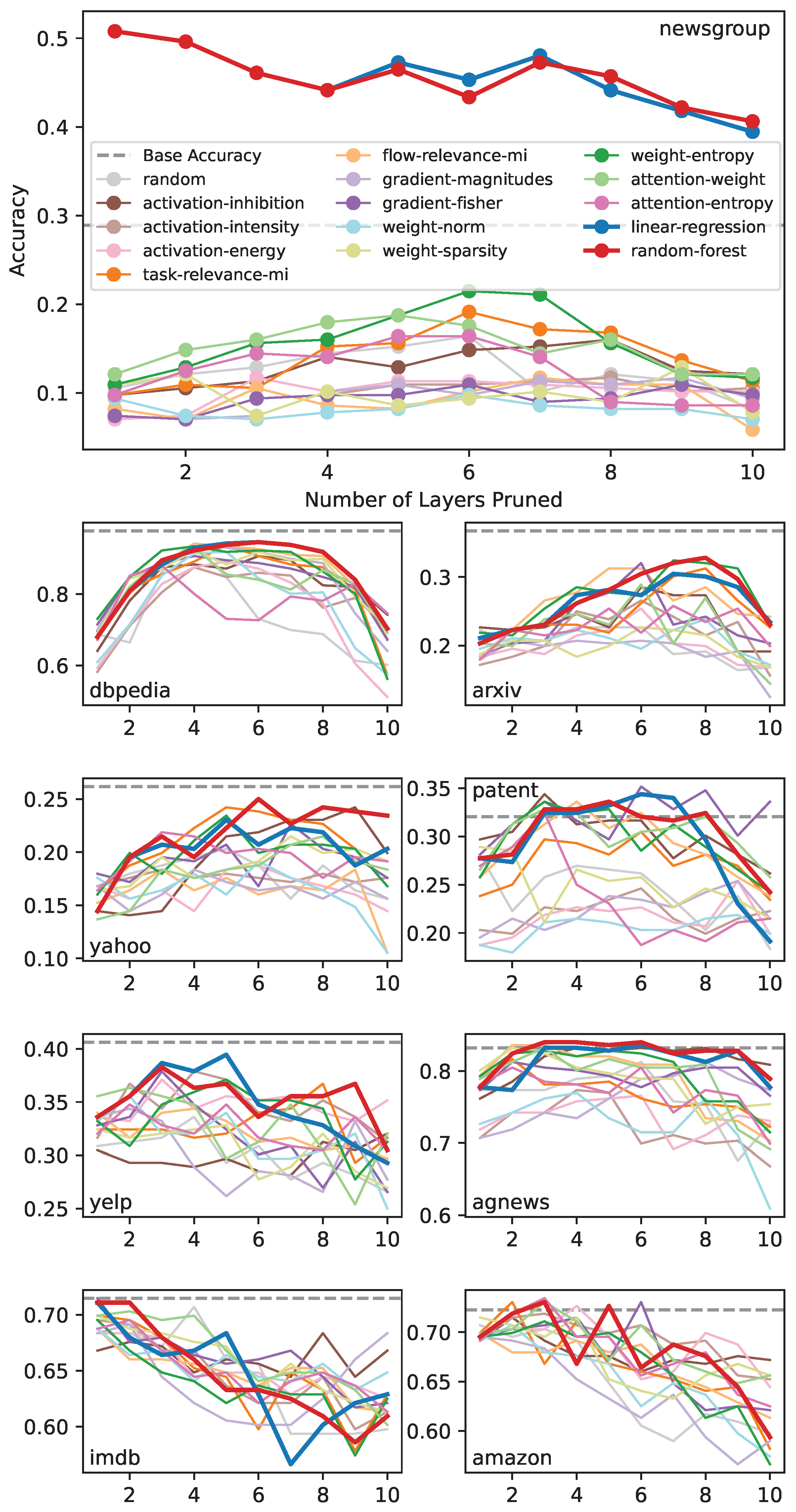

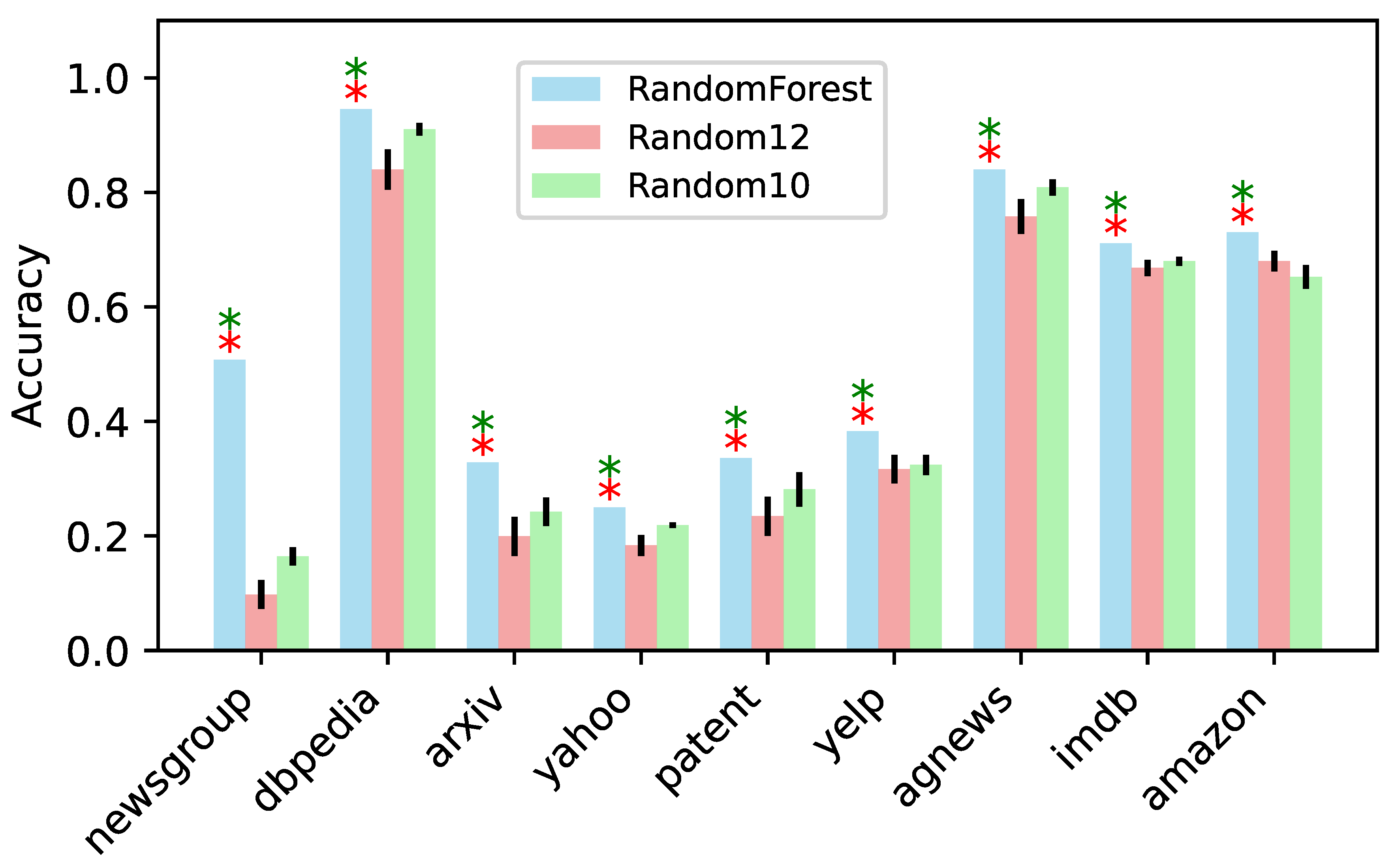

accuracy-trends-vs-layers-pruned illustrates the accuracy trends as the model is sequentially compressed by pruning layers, one at a time, across nine datasets. For the newsgroup dataset, the trends derived from strategic fusion methods (Random Forest and Linear Regression) are notably distinct from the others. Other well-performing methods include Weight-Entropy, Task-Relevance-MI, and in some datasets, Gradient-Fisher. Although the performance of different strategies varies across the datasets, the general trends of high-performing strategies remain consistent.

The trends in

Figure 1 provide a comprehensive view of how each strategy performs as the layers are pruned sequentially across the datasets. However, the ultimate goal is to identify a model, with a specific number of pruned layers, that performs optimally. To this end, we extracted the maximum accuracy achieved by each strategy for each dataset, as summarized in

Table 1. The results reveal that the strategic fusion with the random forest performs best for seven out of nine datasets, while the strategic fusion with linear regression leads for five datasets. Other notable methods, such as Task-Relevance-MI, Gradient-Fisher, and Attention-Weight, also perform well in specific datasets. Interestingly, the highest accuracies achieved by these individual strategies are also obtained through the strategic fusion methods, with the exception of Gradient-Fisher for one dataset. This indicates that strategic fusion-based layer pruning consistently outperforms individual strategy-based pruning, highlighting the importance of considering interactions between layer-specific metrics for informed pruning decisions. Moreover, the superior performance of the random forest-based fusion suggests that nonlinear interactions between these metrics are more prevalent and impactful than linear ones.

So far, we have focused on maximum accuracy as a measure of effectiveness for the best-performing model on each dataset. However, relying solely on maximum accuracy overlooks three critical factors. First, strategies that yield accuracies close to the maximum, such as the second or third best, can also be effective and merit consideration, as small differences in accuracy may not translate into meaningful performance differences. Second, this approach ignores the accuracy drops from the baseline model, which are crucial for assessing the feasibility of pruning. Ideally, pruning should result in a negligible or no accuracy drop; substantial drops could make pruning unsuitable. Third, some strategies might achieve slightly lower accuracy but with more layers pruned, resulting in smaller models, a trade-off that is essential for many resource-constrained applications. Addressing these factors allows for a more nuanced evaluation of the strategies and their practical effectiveness.

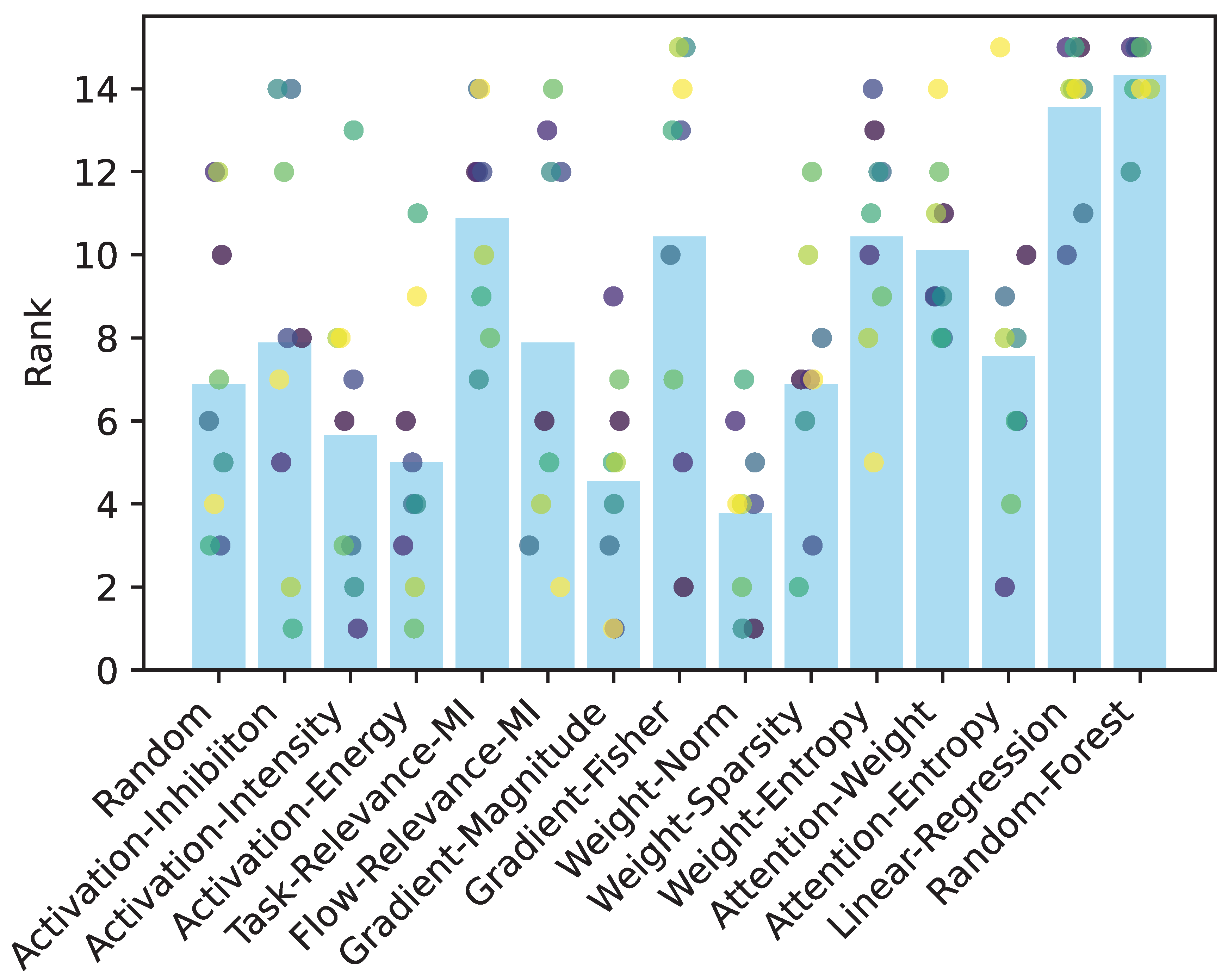

We addressed the first factor by computing the rank of each strategy for each dataset. For a given dataset, the strategies are ranked based on maximum accuracy and the rank (index + 1) is assigned to each strategy. These ranks, displayed in

Figure 2, reveal that the random forest consistently achieves high ranks in all datasets, followed by linear regression. Both methods are clearly distinguishable from other individual strategies. Although certain datasets rank individual strategies higher, such as Gradient-Fisher, Task-Relevance-MI, Weight-Entropy, and Attention-Weight, most datasets rank these independent strategies lower overall.

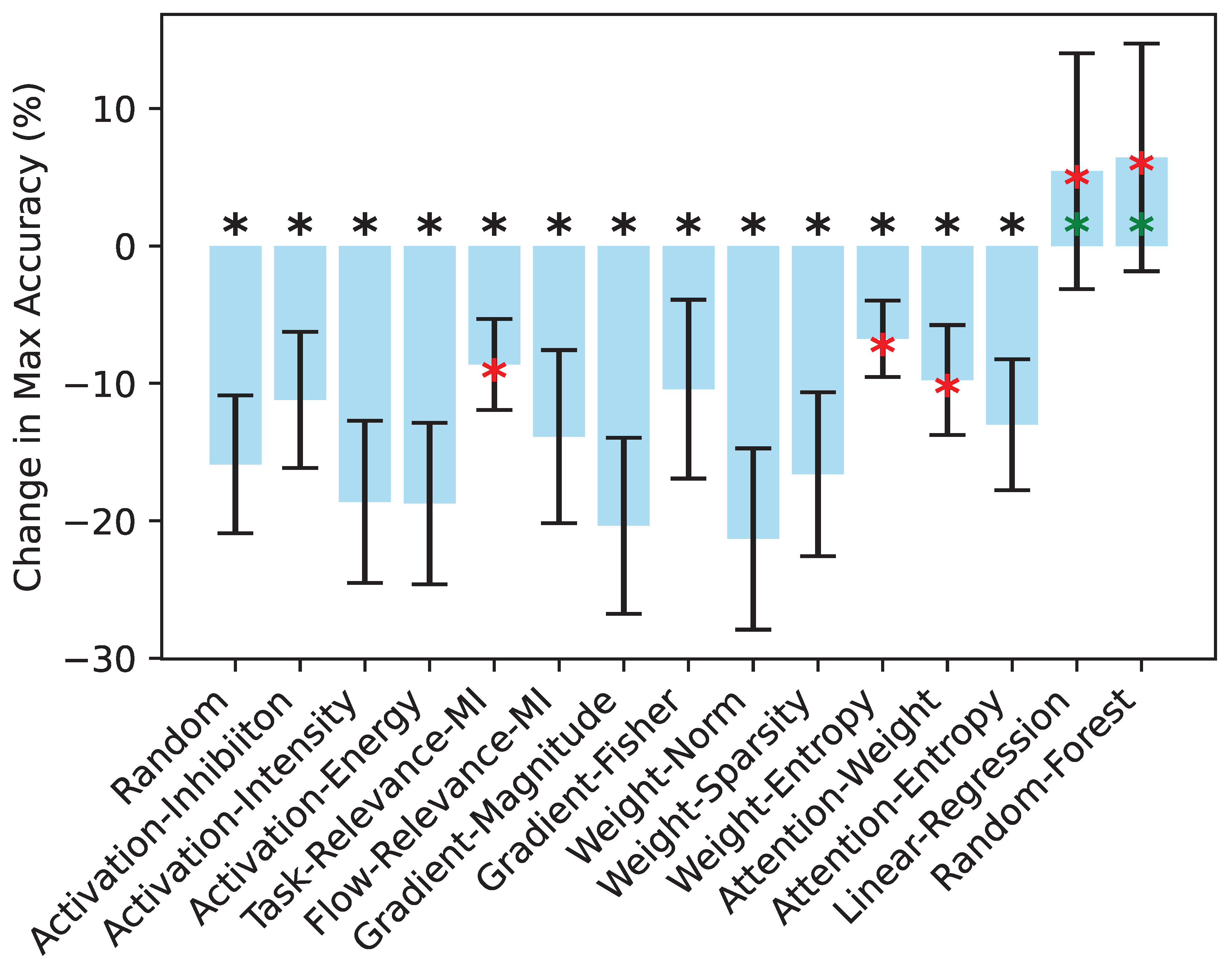

To address concerns about decline in accuracy, we calculated the change in maximum accuracy relative to baseline accuracy, as shown in

Figure 3. Independent strategies show consistent accuracy drops, with their accuracies statistically lower than zero (Wilcoxon signed-rank test,

). In contrast, the changes in accuracy in strategic fusion approaches, both linear regression and random forest, are not significantly different from zero (

), indicating that strategic fusion maintains baseline accuracy. Among individual strategies, Task-Relevance-MI, Weight-Entropy, and Attention-Weight showed smaller accuracy drops than the random method (

), demonstrating their relative effectiveness.

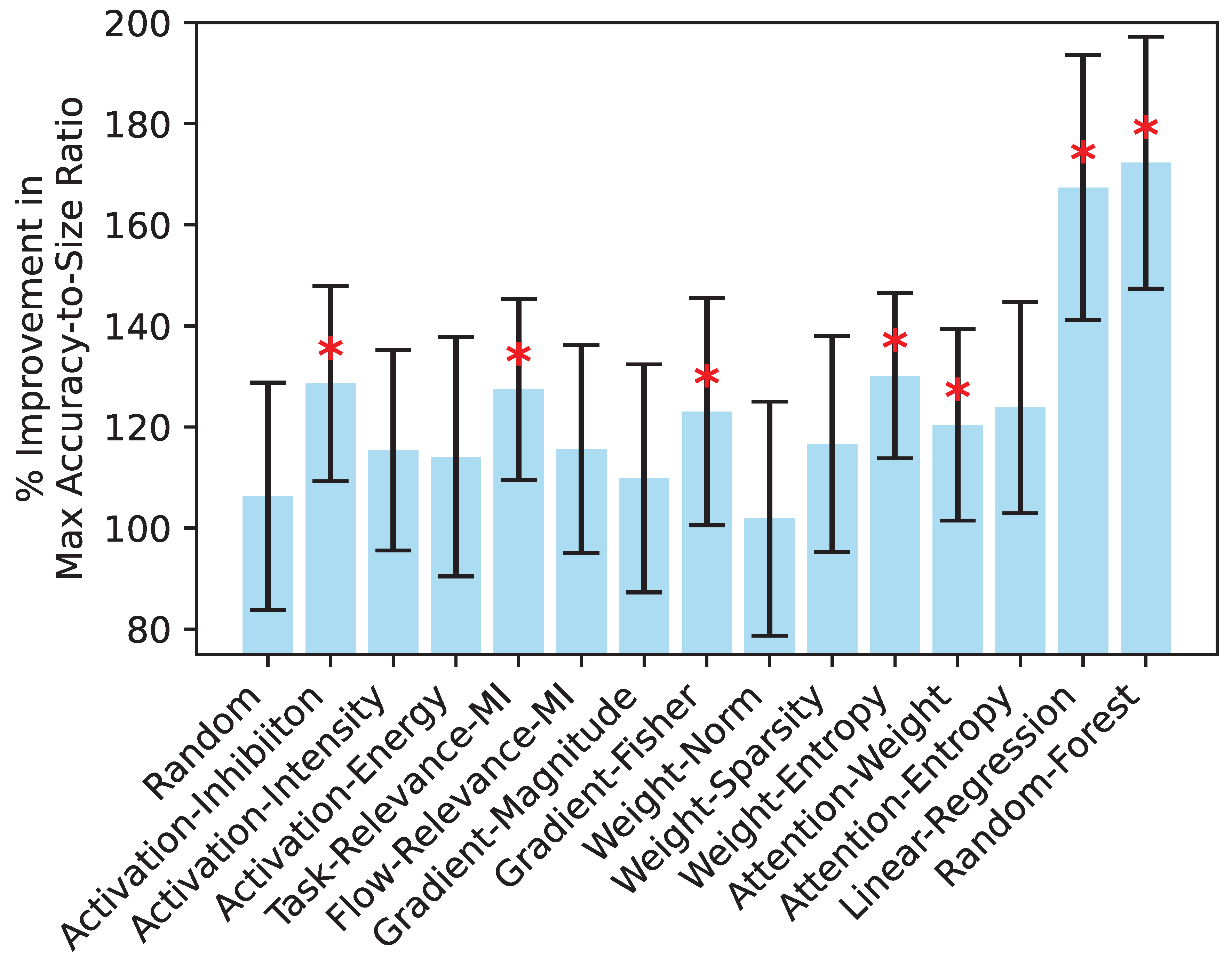

To address both accuracy and model size considerations, we computed the percentage improvement in the maximum accuracy-to-size ratio by comparing the ratio of the maximum accuracy to the size of the compressed model with the corresponding ratio for the base model. This improvement reflects the relative percentage increase in the accuracy-to-size ratio of the compressed model compared to the original uncompressed model, highlighting the efficiency gained through pruning. The size of the model is determined by the number of parameters it contains. The original uncompressed model has 109,489,930 parameters, and pruning one layer reduces the number of parameters by 7,087,872. These parameters are converted to gigabytes assuming each weight uses 32-bit precision. This sequential reduction in parameters during pruning is factored into the size calculations, providing a basis for evaluating the trade-off between accuracy and size.

This metric, shown in

Figure 4, indicates that the mean value of this metric is significantly higher for the two strategic fusion approaches (Linear-Regression and Random-Forest) and for five individual strategies (Activation-Inhibition, Task-Relevance-MI, Gradient-Fisher, Weight-Entropy, and Attention-Weight) compared to the random method (

). However, as the figure shows, the maximum accuracy-to-size ratio achieved by strategic fusion approaches is distinctly higher and clearly outperforms the independent strategies, highlighting the superior performance of strategic fusion in balancing accuracy and compression.

Figure 1.

Comparison of accuracies across nine datasets as the increasing number of transformer layers being pruned. Each colored line corresponds to a distinct pruning strategy, with the dashed line indicating the unpruned baseline accuracy. The plots highlight how different pruning criteria affect model performance at varying compression levels.

Figure 1.

Comparison of accuracies across nine datasets as the increasing number of transformer layers being pruned. Each colored line corresponds to a distinct pruning strategy, with the dashed line indicating the unpruned baseline accuracy. The plots highlight how different pruning criteria affect model performance at varying compression levels.

Figure 2.

Ranking of the strategies for various datasets. Bars represent the mean rank of each method, while dots indicate the rank for individual datasets. Ranks are computed by sorting strategies for each dataset based on their maximum accuracy, with the highest accuracy assigned rank 15 (because of a total of 15 strategies including random), the second highest rank 14, and so on.

Figure 2.

Ranking of the strategies for various datasets. Bars represent the mean rank of each method, while dots indicate the rank for individual datasets. Ranks are computed by sorting strategies for each dataset based on their maximum accuracy, with the highest accuracy assigned rank 15 (because of a total of 15 strategies including random), the second highest rank 14, and so on.

Figure 3.

Percentage change in maximum accuracy compared to the baseline for each strategy. Black asterisks indicate that the means are significantly less than zero. Red asterisks indicate that the means are significantly higher than the mean of random method. Green asterisks indicate that the means are not significantly different from zero. All tests are based on Wilcoxon signed-rank test, .

Figure 3.

Percentage change in maximum accuracy compared to the baseline for each strategy. Black asterisks indicate that the means are significantly less than zero. Red asterisks indicate that the means are significantly higher than the mean of random method. Green asterisks indicate that the means are not significantly different from zero. All tests are based on Wilcoxon signed-rank test, .

Figure 4.

Maximum accuracy-to-size ratio for each method, averaged across all datasets. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean. Red asterisks indicate strategies in which the ratio is statistically significantly different from the random strategy (Wilcoxon signed-rank test, ).

Figure 4.

Maximum accuracy-to-size ratio for each method, averaged across all datasets. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean. Red asterisks indicate strategies in which the ratio is statistically significantly different from the random strategy (Wilcoxon signed-rank test, ).

Table 1.

Maximum accuracy achieved by each method for each dataset. Bold values indicate the method that achieves the highest maximum accuracy for the corresponding dataset.

Table 1.

Maximum accuracy achieved by each method for each dataset. Bold values indicate the method that achieves the highest maximum accuracy for the corresponding dataset.

| Strategy |

newsgroup |

dbpedia |

arxiv |

yahoo |

patent |

yelp |

agnews |

imdb |

amazon |

| Baseline (uncompressed) |

0.289 |

0.977 |

0.367 |

0.262 |

0.320 |

0.406 |

0.832 |

0.705 |

0.723 |

| Random |

0.164 |

0.938 |

0.227 |

0.203 |

0.281 |

0.336 |

0.812 |

0.707 |

0.707 |

| Activation-Inhibition |

0.160 |

0.906 |

0.285 |

0.242 |

0.344 |

0.320 |

0.832 |

0.684 |

0.715 |

| Activation-Intensity |

0.117 |

0.875 |

0.266 |

0.184 |

0.246 |

0.379 |

0.773 |

0.695 |

0.719 |

| Activation-Energy |

0.117 |

0.891 |

0.254 |

0.188 |

0.254 |

0.371 |

0.766 |

0.684 |

0.727 |

| Task-Relevance-MI |

0.191 |

0.938 |

0.312 |

0.242 |

0.305 |

0.367 |

0.816 |

0.699 |

0.730 |

| Flow-Relevance-MI |

0.117 |

0.941 |

0.312 |

0.184 |

0.336 |

0.344 |

0.836 |

0.688 |

0.699 |

| Gradient-Magnitudes |

0.117 |

0.930 |

0.207 |

0.184 |

0.254 |

0.344 |

0.812 |

0.691 |

0.695 |

| Gradient-Fisher |

0.109 |

0.906 |

0.320 |

0.227 |

0.352 |

0.379 |

0.812 |

0.715 |

0.730 |

| Weight-Norm |

0.098 |

0.918 |

0.238 |

0.191 |

0.219 |

0.355 |

0.770 |

0.688 |

0.707 |

| Weight-Sparsity |

0.129 |

0.922 |

0.227 |

0.215 |

0.289 |

0.328 |

0.832 |

0.699 |

0.715 |

| Weight-Entropy |

0.215 |

0.934 |

0.324 |

0.234 |

0.336 |

0.371 |

0.828 |

0.695 |

0.711 |

| Attention-Weight |

0.188 |

0.93 |

0.289 |

0.215 |

0.328 |

0.363 |

0.832 |

0.703 |

0.730 |

| Attention-Entropy |

0.164 |

0.879 |

0.258 |

0.219 |

0.324 |

0.348 |

0.805 |

0.695 |

0.734 |

| Linear-Regression |

0.508 |

0.945 |

0.305 |

0.230 |

0.344 |

0.395 |

0.836 |

0.711 |

0.730 |

| Random-Forest |

0.508 |

0.945 |

0.328 |

0.250 |

0.336 |

0.383 |

0.840 |

0.711 |

0.730 |

3.2. Knowledge Distillation Mitigates Accuracy Drops

We have established that strategic fusion-based layer pruning, specifically with Random-Forest, is an effective compression technique. However, as with other compression methods, this approach often reduces the accuracy compared to the original model, with some rare exceptions. One way to mitigate this accuracy drop is through knowledge distillation, where the compressed model (student) is trained to mimic the predictions of the original model (teacher). During this process, the teacher model provides "soft labels" (probabilistic outputs) as guidance, which helps the student model learn finer-grained information about the data distribution beyond hard labels.

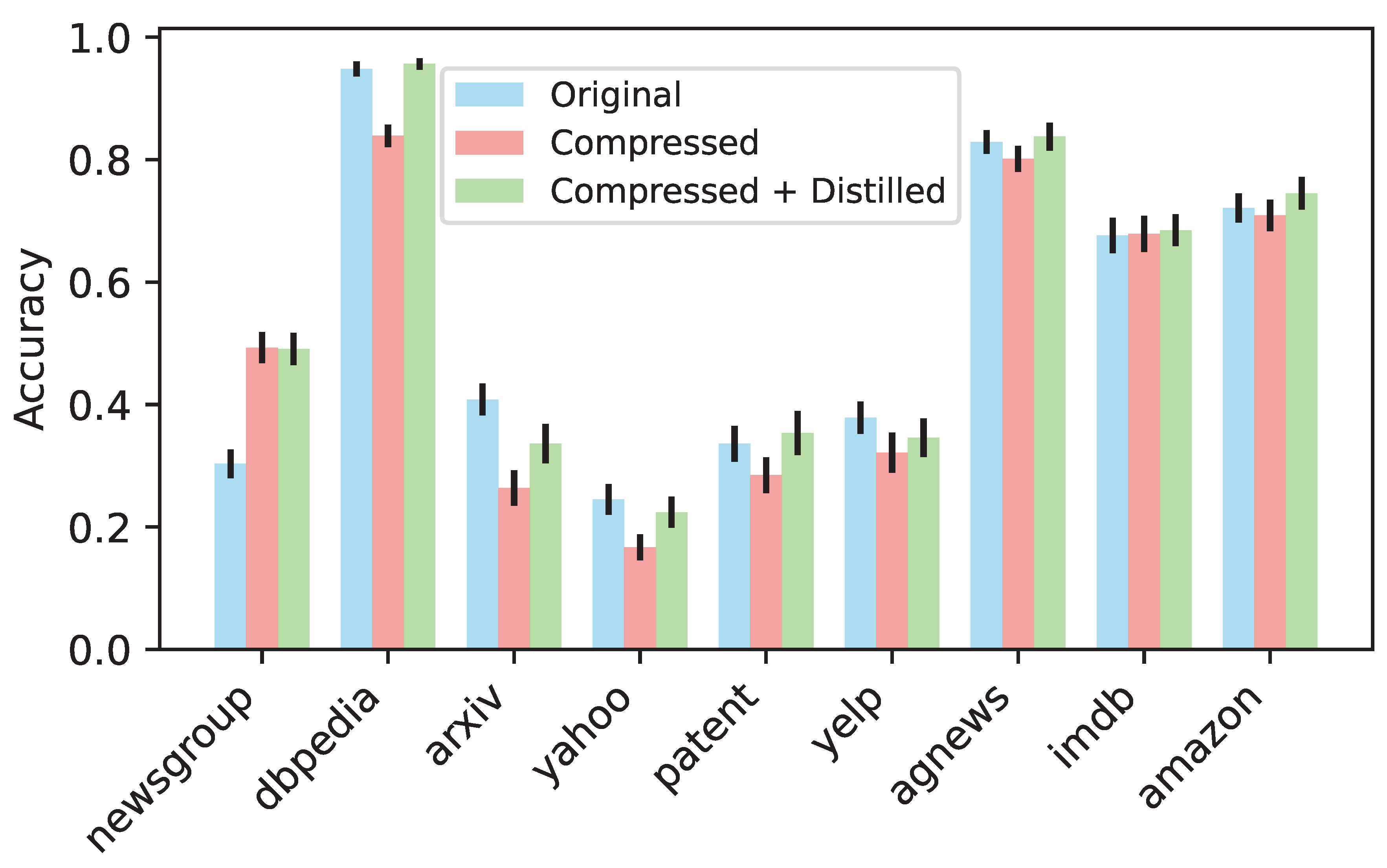

To evaluate this, we created a student model based on the compressed model that achieved the highest accuracy using the random forest-based layer pruning strategy. We then trained the student model using the teacher model and compared the accuracies of the original model, the compressed model, and the compressed model with distillation. These results are shown in

Figure 5. In most datasets, the compressed model exhibited a drop in accuracy compared to the original model, except for newsgroup and imdb, where the compressed model performed with higher accuracies. After applying knowledge distillation, the accuracy of the compressed model improved in most cases and, in some instances, even surpassed the original model’s accuracy. Using accuracies after distillation, the accuracy-to-size ratio increased by a factor of 18.84 on average (mean: 18.84, std: 6.28, min: 10.29, max: 29.29).

Figure 5.

Accuracy comparison between the original model, compressed model (random forest strategic fusion), and compressed model with knowledge distillation. Distillation surpasses original accuracy for six datasets, and mitigates accuracy drops in the remaining three.

Figure 5.

Accuracy comparison between the original model, compressed model (random forest strategic fusion), and compressed model with knowledge distillation. Distillation surpasses original accuracy for six datasets, and mitigates accuracy drops in the remaining three.

Our results align with the findings by [

26], who showed that pruning combined with selective retraining achieves state-of-the-art compression with minimal performance degradation. However, the improvement is not evident for datasets in which the compressed model already significantly outperformed the original model. This suggests that the teacher model may have limitations in effectively transferring knowledge to the student model in these scenarios. Therefore, while random forest-based compression followed by knowledge distillation effectively mitigates accuracy drops, distillation may not be necessary when the compressed model already achieves higher accuracy.

3.3. Why Does Strategic Fusion Outperform Individual Strategies?

In this section, we address why strategic fusion performs better than individual strategies. Strategic fusion combines multiple strategies to capture the significance of each layer in a more comprehensive way. Linear regression aggregates individual strategies using a linear weighted combination, while random forest captures the nonlinear interactions between the strategies. This allows fusion models to incorporate multiple layer-specific signals and ensures that no single strategy or signal dominates the pruning decision. The aggregated metric essentially uses the strengths of individual strategies, compensating for their potential weaknesses, and leads to better-informed pruning decisions.

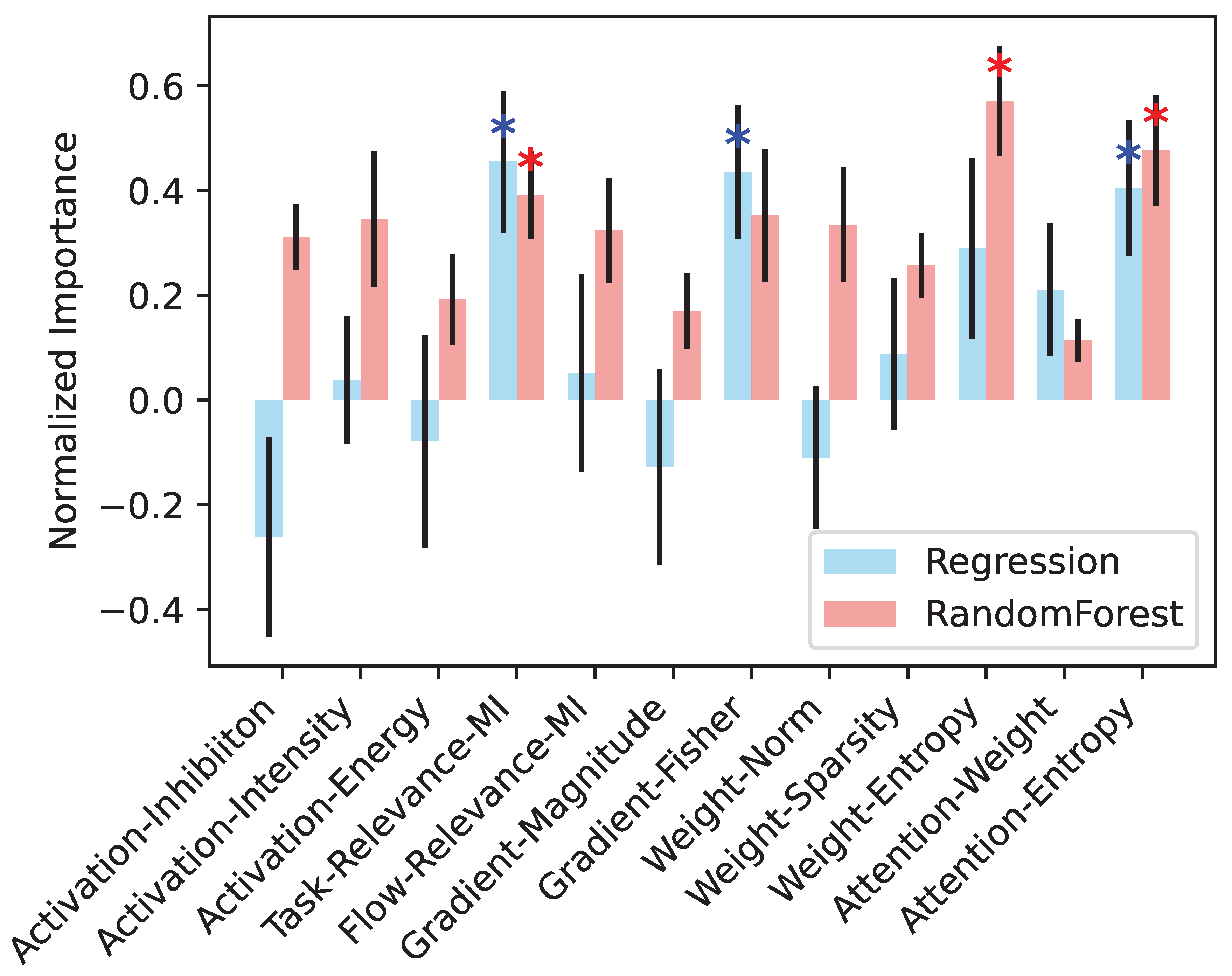

We analyze different strategies from different perspectives. First, we measure how much each underlying strategy contributes to the fusion models. Specifically, we retrieve the learned weights (linear regression) or feature importance (random forest) assigned to each strategy, rescale them in

, and average them across datasets as shown in

Figure 6. We observe that Task-Relevance-MI and Gradient-Fisher are dominant in the linear regression fusion, while Task-Relevance-MI and Weight-Entropy contribute more to the random forest fusion. Intriguingly, Attention-Entropy plays a significant role in both fusion strategies, but did not appear among top performers in other analyses (

Table 1 and

Figure 2 and

Figure 4). This finding is a good example of why single-metric pruning, such as strategies with attention entropy or activation energy, can fail.

Figure 6.

Normalized importance of each method, averaged across all datasets. Errorbar indicates standard error of mean. Blue asterisk indicates that the weight assigned to the strategy/feature by linear regression is significantly higher than zero. Red asterisk indicates that the importance of the strategy in random forest is significantly higher than the median importance across all strategies. All tests are based on Wilcoxon signed-rank test, .

Figure 6.

Normalized importance of each method, averaged across all datasets. Errorbar indicates standard error of mean. Blue asterisk indicates that the weight assigned to the strategy/feature by linear regression is significantly higher than zero. Red asterisk indicates that the importance of the strategy in random forest is significantly higher than the median importance across all strategies. All tests are based on Wilcoxon signed-rank test, .

Attention entropy (defined in Equation (16)) measures how broadly or narrowly attention is spread. Ignoring the small constant

for simplicity, we have:

where

is the attention score from token

i to token

j for head

k. For each specific

i and

k:

High entropy arises when attention is evenly distributed (

), giving

. Low entropy arises when attention is entirely focused on a single token (

), giving

. Accordingly, the attention output:

where

is the value vector for token

j in head

k, becomes:

and

Equation (26) implies that, with high entropy, no single token receives a higher score than others, so the heads capture broader context and miss key details. Conversely, attention-output-low-entropy implies that, with low entropy, the heads are entirely focus on token

and neglect the context from other tokens. Both extremes are suboptimal, as an effective balance between context and focus is crucial. A single-signal pruning strategy, based solely on attention entropy, tends to favor one of these extremes. Consequently, such a strategy is unlikely to perform well, whether it prioritizes pruning low-entropy or high-entropy layers first. In contrast, fusion-based strategies adaptively achieve this balance by considering interactions with other metrics.

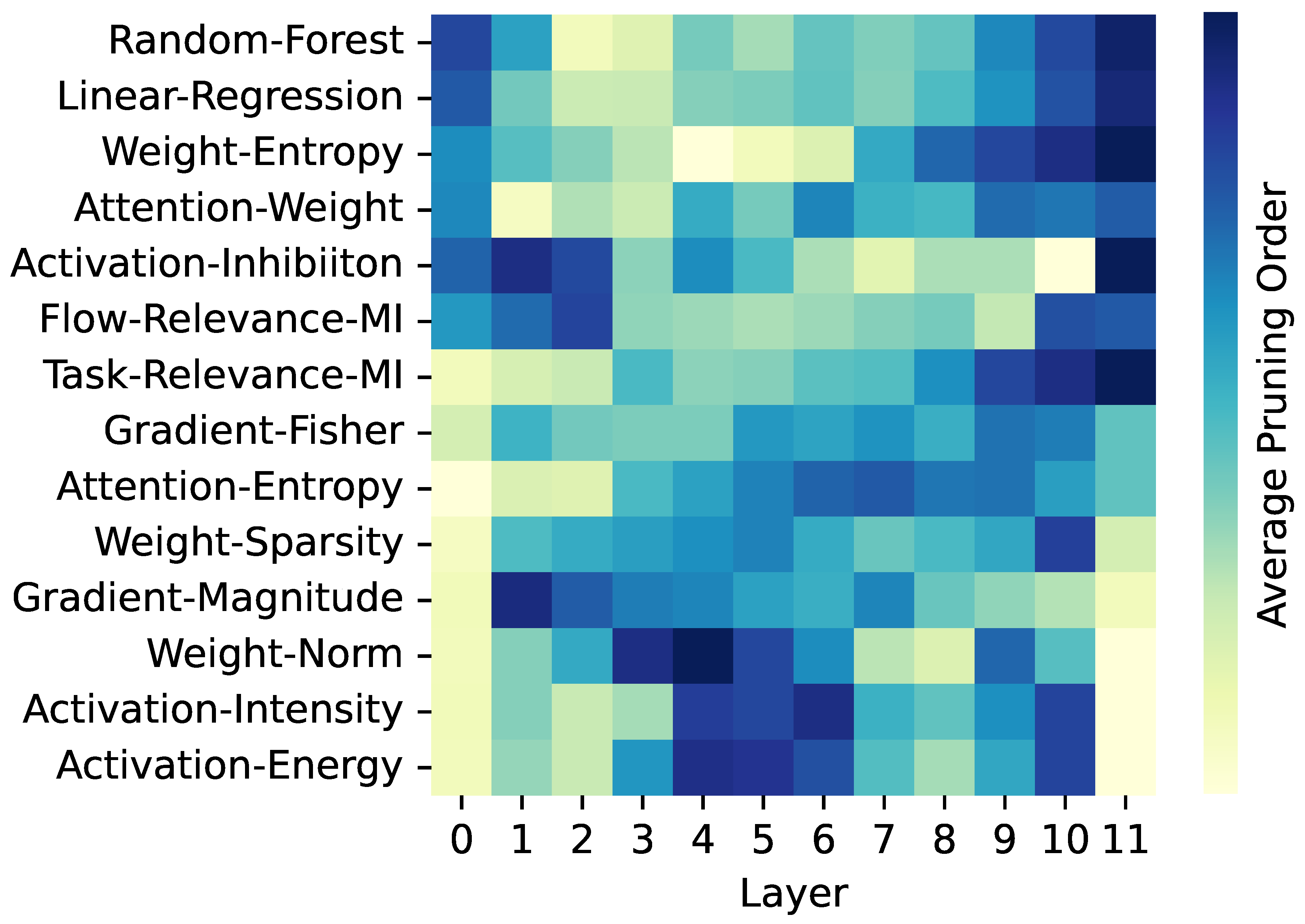

Second, we investigate the similarities and differences between the strategies, and get an insight why one might perform better than the other. We use the sequence of layers pruned by each strategy for this investigation. We computed the importance ranks of the layer as the order of sequence of pruning, e.g., if a layer is pruned first by a strategy, the rank is 1, while if a layer is pruned second, the rank is 2, and so on.

Figure 7 demonstrates the average ranking of layer importance for various strategies. High-performing strategies, such as Random-Forest and Linear-Regression, rank the edge layers (beginning and ending layers) higher. Top-performing individual strategies, such as Weight-Entropy, Attention-Weight, and Activation-Inhibition, also rank the edge layers higher. Other top-performing individual strategies, such as Task-Relevance-MI and Gradient-Fisher, rank the ending layers higher. In contrast, poorly performing strategies, such as Weight-Norm, and Activation-Energy, consistently assign lower ranks to the both edge layers and prune them early. The starting layers extract low-level features from the input, and the ending layers translate these into task-specific outputs. Therefore, any strategy that prunes the edge layers early can disrupt critical functionality and lead to accuracy degradation.

Many metrics may exhibit consistently low or high values in the edge layers. Single-metric strategies rely on predefined patterns (e.g., pruning layers with low metric values first, or high metric values first) to determine the pruning order. However, these predefined patterns do to account for the contextual significance of the layers, such as their functional roles in the model. For example, the output layer is specialized for task-specific processing. For a given task, only a few neurons may exhibit high activity, while many outputs remain close to zero. This can result in low values for metrics such as activation energy, activation intensity, or weight norm. However, these low metric values should not imply that the output layer is less important, as it plays a crucial role in translating the learned features into task-specific predictions. Fusion methods can avoid this issue by combining multiple metrics, allowing the model to account for the functional importance of layers rather than relying on any predefined rules or on individual metric values.

Figure 7.

Heatmap of average order in which each layer was pruned for various pruning strategies. Darker colors indicate layers pruned later in the sequence, while lighter colors represent layers pruned earlier.

Figure 7.

Heatmap of average order in which each layer was pruned for various pruning strategies. Darker colors indicate layers pruned later in the sequence, while lighter colors represent layers pruned earlier.

Third, the fusion model is more analogous to brain circuits than a single strategy. Fusion strategy mirrors how the brain integrates diverse signals to make decisions [

27]. The human brain does not rely on a single cue, but instead combines information from multiple sources, such as sensory inputs, contextual relevance, and past experiences, to prioritize and allocate resources effectively. Similarly, fusion strategies aggregate multiple individual strategies, each reflecting a distinct aspect of layer importance. This fusion enables a comprehensive assessment of which layers to prune first and next. While this analogy is not data-driven and is based on what is known about brain functions, it does not provide definitive conclusions about pruning strategies. Instead, it serves as an inspiration to guide further research in exploring biologically inspired approaches to model optimization.