Submitted:

02 January 2025

Posted:

07 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Sensory Integration

3. Sensorimotor Integration

4. Basal Ganglia and Sensorimotor Integration

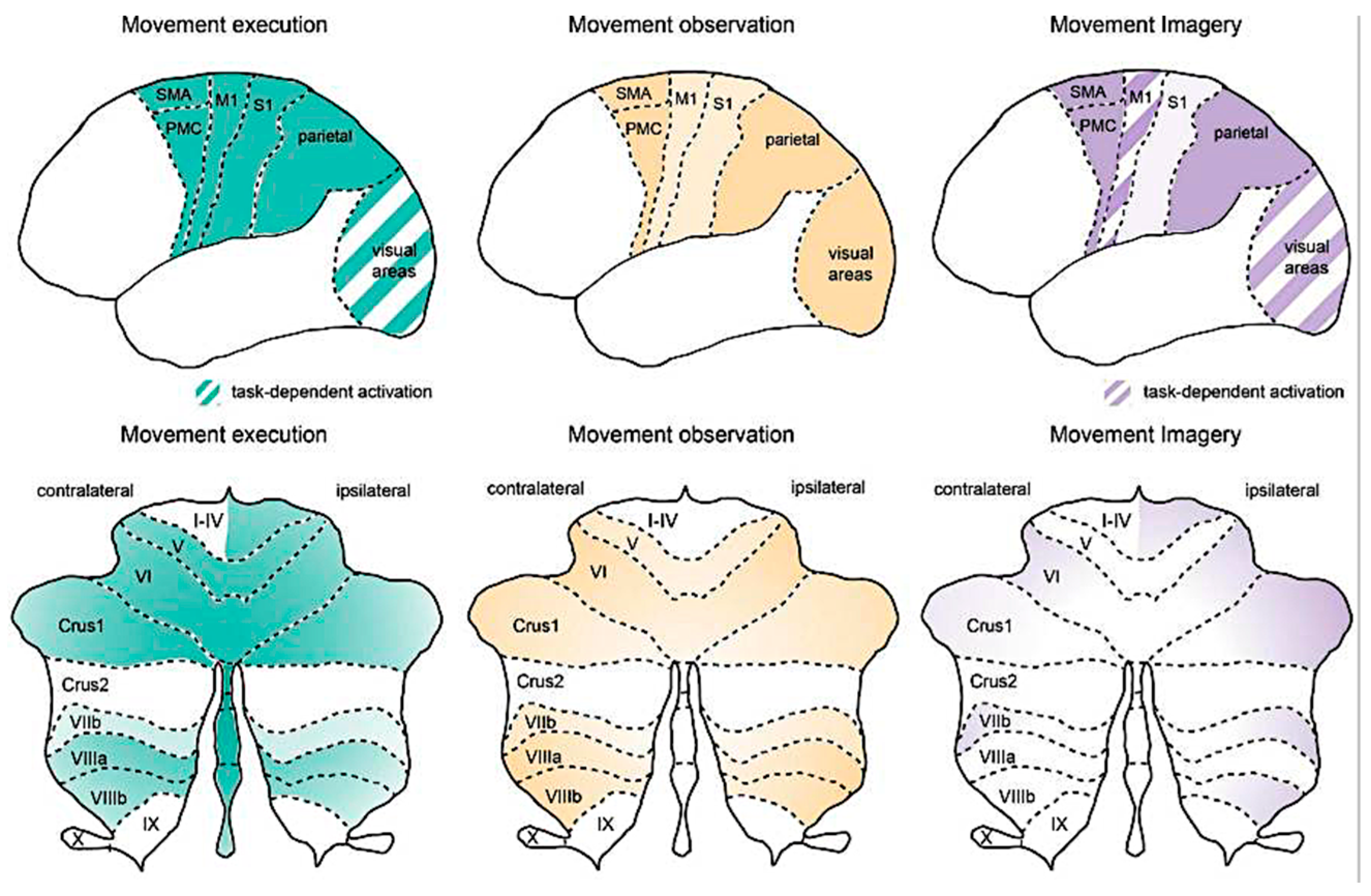

5. Cerebellum and Sensorimotor Integration

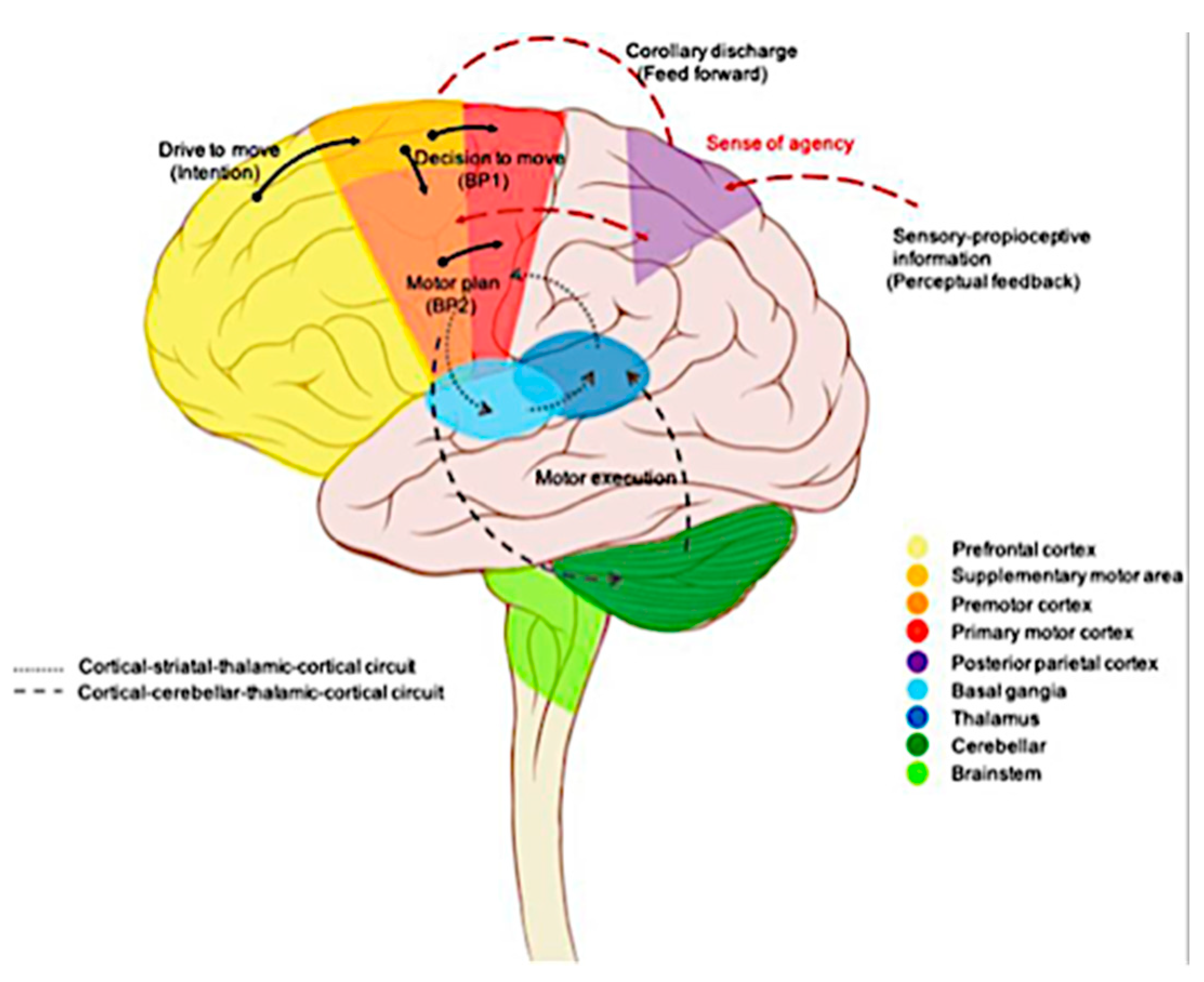

6. Cortical Areas and Sensorimotor Integration

7. Mental Imagery and Sensorimotor Integration

8. Implications

9. Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stein, B.E.; Stanford, T.R.; Rowland, B.A. Multisensory Integration and the Society for Neuroscience: Then and Now. J. Neurosci. 2020, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angelaki, D.E.; Gu, Y.; DeAngelis, G.C. Multisensory Integration: Psychophysics, Neurophysiology, and Computation. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2009, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noel, J.P.; Blanke, O.; Serino, A. From Multisensory Integration in Peripersonal Space to Bodily Self-Consciousness: From Statistical Regularities to Statistical Inference. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2018, 1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turecek, J; Ginty, D. How Two Intermingled Sensory Pathways Combine to Encode Touch. Nature 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, K.G.; Leow, Y.N.; Le, N.M.; Adam, E.; Huda, R.; Sur, M. Cortical-Subcortical Interactions in Goal-Directed Behavior. Physiol. Rev. 2023, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keil, J.; Senkowski, D. Neural Oscillations Orchestrate Multisensory Processing. Neuroscientist 2018, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, M.; Spennemann, D.H.R.; Bond, J. Sensory and Multisensory Perception—Perspectives toward Defining Multisensory Experience and Heritage. J. Sens. Stud. 2024, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michail, G.; Senkowski, D.; Holtkamp, M.; Wächter, B.; Keil, J. Early Beta Oscillations in Multisensory Association Areas Underlie Crossmodal Performance Enhancement. Neuroimage 2022, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Rueda, A.; Jensen, K.; Noormandipour, M.; de Malmazet, D.; Wilson, J.; Ciabatti, E.; Kim, J.; Williams, E.; Poort, J.; Hennequin, G.; et al. Kinetic Features Dictate Sensorimotor Alignment in the Superior Colliculus. Nature 2024, 631, 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, A.G.E.; McDougle, S.D. Context Is Key for Learning Motor Skills. Nature 2021, 600, 387–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacoboni, M.; Dapretto, M. The Mirror Neuron System and the Consequences of Its Dysfunction. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2006, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizzolatti, G.; Luppino, G. The Cortical Motor System. Neuron 2001, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizzolatti, G.; Cattaneo, L.; Fabbri-Destro, M.; Rozzi, S. Cortical Mechanisms Underlying the Organization of Goal-Directed Actions and Mirror Neuron-Based Action Understanding. Physiol. Rev. 2014, 94, 655–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steriade, M. Grouping of Brain Rhythms in Corticothalamic Systems. Neuroscience 2006, 137, 1087–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.R. When Brain Rhythms Aren’t ‘Rhythmic’: Implication for Their Mechanisms and Meaning. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2016, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thut, G.; Miniussi, C.; Gross, J. The Functional Importance of Rhythmic Activity in the Brain. Curr. Biol. 2012, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalobos, N.; Almazán-Alvarado, S.; Magdaleno-Madrigal, V.M. Elevation of GABA Levels in the Globus Pallidus Disinhibits the Thalamic Reticular Nucleus and Desynchronized Cortical Beta Oscillations. J. Physiol. Sci. 2022, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blenkinsop, A.; Anderson, S.; Gurney, K. Frequency and Function in the Basal Ganglia: The Origins of Beta and Gamma Band Activity. J. Physiol. 2017, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavi, M.; Dostrovsky, J.O.; Hodaie, M.; Lozano, A.M.; Hutchison, W.D. Spatial Extent of Beta Oscillatory Activity in and between the Subthalamic Nucleus and Substantia Nigra Pars Reticulata of Parkinson’s Disease Patients. Exp. Neurol. 2013, 245, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barone, J.; Rossiter, H.E. Understanding the Role of Sensorimotor Beta Oscillations. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2021, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merel, J.; Botvinick, M.; Wayne, G. Hierarchical Motor Control in Mammals and Machines. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, G.E.; Crutcher, M.D. Functional Architecture of Basal Ganglia Circuits: Neural Substrates of Parallel Processing. Trends Neurosci. 1990, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graybiel, A.M. A Stereometric Pattern of Distribution of Acetylthiocholinesterase in the Deep Layers of the Superior Colliculus. Nature 1978, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, G.E.; DeLong, M.R.; Strick, P.L. Parallel Organization of Functionally Segregated Circuits Linking Basal Ganglia and Cortex. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 1986, VOL. 9, 357–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Torre-Martinez, R.; Ketzef, M.; Silberberg, G. Ongoing Movement Controls Sensory Integration in the Dorsolateral Striatum. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambu, A.; Tokuno, H.; Takada, M. Functional Significance of the Cortico-Subthalamo-Pallidal ‘hyperdirect’ Pathway. Neurosci. Res. 2002, 43, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; de Hemptinne, C.; Miller, A.M.; Leibbrand, M.; Little, S.J.; Lim, D.A.; Larson, P.S.; Starr, P.A. Prefrontal-Subthalamic Hyperdirect Pathway Modulates Movement Inhibition in Humans. Neuron 2020, 106, 579-588.e3. [CrossRef]

- Ding, L. Contributions of the Basal Ganglia to Visual Perceptual Decisions. Annu. Rev. Vis. Sci. 2023, 9, 385–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condé, H. Organization and Physiology of the Substantia Nigra. Exp. Brain Res. 1992, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, W. Dopamine Reward Prediction-Error Signalling: A Two-Component Response. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2016, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matityahu, L.; Gilin, N.; Sarpong, G.A.; Atamna, Y.; Tiroshi, L.; Tritsch, N.X.; Wickens, J.R.; Goldberg, J.A. Acetylcholine Waves and Dopamine Release in the Striatum. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Threlfell, S.; Lalic, T.; Platt, N.J.; Jennings, K.A.; Deisseroth, K.; Cragg, S.J. Striatal Dopamine Release Is Triggered by Synchronized Activity in Cholinergic Interneurons. Neuron 2012, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apicella, P. The Role of the Intrinsic Cholinergic System of the Striatum: What Have We Learned from TAN Recordings in Behaving Animals? Neuroscience 2017, 360, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moretti, R.; Caruso, P.; Crisman, E.; Gazzin, S. Basal Ganglia: Their Role in Complex Cognitive Procedures in Experimental Models and in Clinical Practice. Neurol. India 2017, 65. [Google Scholar]

- O’Rawe, J.F.; Leung, H.C. Topographic Organization of the Human Caudate Functional Connectivity and Age-Related Changes with Resting-State FMRI. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2022, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, V.; D’Esposito, M. The Role of PFC Networks in Cognitive Control and Executive Function. Neuropsychopharmacology 2022, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosakowski, H.L.; Saadon-Grosman, N.; Du, J.; Eldaief, M.C.; Buckner, R.L. Human Striatal Association Megaclusters. J. Neurophysiol. 2024, 131, 1083–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoni, D. The Cerebellum and Sensorimotor Coupling: Looking at the Problem from the Perspective of Vestibular Reflexes. Cerebellum 2007, 6, 24–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazantsev, V.B.; Nekorkin, V.I.; Makarenko, V.I.; Llinás, R. Olivo-Cerebellar Cluster-Based Universal Control System. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, J.H. Cerebellar Learning Mechanisms. Brain Res. 2015, 1621, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheron, G.; Márquez-Ruiz, J.; Dan, B. Oscillations, Timing, Plasticity, and Learning in the Cerebellum. Cerebellum 2016, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, S.M.; Bastian, A.J. Cerebellar Control of Balance and Locomotion. Neuroscientist 2004, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llinás, R.R. The Olivo-Cerebellar System: A Key to Understanding the Functional Significance of Intrinsic Oscillatory Brain Properties. Front. Neural Circuits 2014, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pisotta, I.; Molinari, M. Cerebellar Contribution to Feedforward Control of Locomotion. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2014, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leech, K.A.; Roemmich, R.T.; Gordon, J.; Reisman, D.S.; Cherry-Allen, K.M. Updates in Motor Learning: Implications for Physical Therapist Practice and Education. Phys. Ther. 2022, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Streng, M.L.; Popa, L.S.; Ebner, T.J. Cerebellar Representations of Errors and Internal Models. Cerebellum 2022, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Z.; Davis, C.; Thomas, A.M.; Economo, M.N.; Abrego, A.M.; Svoboda, K.; De Zeeuw, C.I.; Li, N. A Cortico-Cerebellar Loop for Motor Planning. Nature 2018, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boven, E.; Cerminara, N.L. Cerebellar Contributions across Behavioural Timescales: A Review from the Perspective of Cerebro-Cerebellar Interactions. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2023, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boven, E.; Pemberton, J.; Chadderton, P.; Apps, R.; Costa, R.P. Cerebro-Cerebellar Networks Facilitate Learning through Feedback Decoupling. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debaere, F.; Wenderoth, N.; Sunaert, S.; Van Hecke, P.; Swinnen, S.P. Internal vs External Generation of Movements: Differential Neural Pathways Involved in Bimanual Coordination Performed in the Presence or Absence of Augmented Visual Feedback. Neuroimage 2003, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henschke, J.U.; Pakan, J.M.P. Engaging Distributed Cortical and Cerebellar Networks through Motor Execution, Observation, and Imagery. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2023, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virameteekul, S.; Bhidayasiri, R. We Move or Are We Moved? Unpicking the Origins of Voluntary Movements to Better Understand Semivoluntary Movements. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Klein-Flügge, M.C.; Bongioanni, A.; Rushworth, M.F.S. Medial and Orbital Frontal Cortex in Decision-Making and Flexible Behavior. Neuron 2022, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nick, Q.; Gale, D.J.; Areshenkoff, C.; De Brouwer, A.; Nashed, J.; Wammes, J.; Zhu, T.; Flanagan, R.; Smallwood, J.; Gallivan, J. Reconfigurations of Cortical Manifold Structure during Reward-Based Motor Learning. Elife 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, J.L. Research on the Cerebellum Yields Rewards. Nature 2020, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sendhilnathan, N.; Semework, M.; Goldberg, M.E.; Ipata, A.E. Neural Correlates of Reinforcement Learning in Mid-Lateral Cerebellum. Neuron 2020, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonsmeier, B.A.; Andronie, M.; Buecker, S.; Frank, C. The Effects of Imagery Interventions in Sports: A Meta-Analysis. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, T.; Cui, H. Neural Geometry from Mixed Sensorimotor Selectivity for Predictive Sensorimotor Control 2024. [CrossRef]

- Rizzolatti, G.; Luppino, G. The Cortical Motor System. Neuron 2001, 31, 889–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzolatti, G.; Fogassi, L.; Gallese, V. Neurophysiological Mechanisms Underlying the Understanding and Imitation of Action. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2001, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbri-Destro, M.; Rizzolatti, G. Mirror Neurons and Mirror Systems in Monkeys and Humans. Physiology 2008, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacoboni, M. Neurobiology of Imitation. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2009, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzolatti, G.; Fabbri-Destro, M.; Cattaneo, L. Mirror Neurons and Their Clinical Relevance. Nat. Clin. Pract. Neurol. 2009, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizzolatti, G.; Cattaneo, L.; Fabbri-Destro, M.; Rozzi, S. Cortical Mechanisms Underlying the Organization of Goal-Directed Actions and Mirror Neuron-Based Action Understanding. Physiol. Rev. 2014, 94, 655–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizzolatti, G.; Sinigaglia, C. The Functional Role of the Parieto-Frontal Mirror Circuit: Interpretations and Misinterpretations. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2010, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizzolatti, G.; Ferrari, P.F.; Rozzi, S.; Fogassi, L. The Inferior Parietal Lobule: Where Action Becomes Perception. In Percept, Decision, Action: Bridging the Gaps; 2008; pp. 129–145 ISBN 9780470034989.

- Fogassi, L. The Mirror Neuron System: How Cognitive Functions Emerge from Motor Organization. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2011, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohbayashi, M. The Roles of the Cortical Motor Areas in Sequential Movements. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2021, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Land, W.M.; Volchenkov, D.; Bläsing, B.E.; Schack, T. From Action Representation to Action Execution: Exploring the Links between Cognitive and Biomechanical Levels of Motor Control. Front. Comput. Neurosci. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spapé, M.M.; Serrien, D.J.; Ravaja, N. 3-2-1, Action! A Combined Motor Control-Temporal Reproduction Task Shows Intentions, Motions, and Consequences Alter Time Perception. Heliyon 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosslyn, S.M.; Ganis, G.; Thompson, W.L. Neural Foundations of Imagery. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2001, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muraki, E.J.; Speed, L.J.; Pexman, P.M. Insights into Embodied Cognition and Mental Imagery from Aphantasia. Nat. Rev. Psychol. 2023, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, P.E. Mental Imagery in Music Performance: Underlying Mechanisms and Potential Benefits. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2012, 1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, M.A.; Tamir, D.I. Neural Representations of Situations and Mental States Are Composed of Sums of Representations of the Actions They Afford. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeannerod, M. Mental Imagery in the Motor Context. Neuropsychologia 1995, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanakawa, T. Organizing Motor Imageries. Neurosci. Res. 2016, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulder, T. Motor Imagery and Action Observation: Cognitive Tools for Rehabilitation. In Proceedings of the Journal of Neural Transmission; 2007; Vol. 114. [Google Scholar]

- Cona, G.; Semenza, C. Supplementary Motor Area as Key Structure for Domain-General Sequence Processing: A Unified Account. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2017, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffin, E.; Mattout, J.; Reilly, K.T.; Giraux, P. Disentangling Motor Execution from Motor Imagery with the Phantom Limb. Brain 2012, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitamura, M.; Kamibayashi, K. Changes in Corticospinal Excitability during Motor Imagery by Physical Practice of a Force Production Task: Effect of the Rate of Force Development during Practice. Neuropsychologia 2024, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzolatti, G.; Fabbri-Destro, M.; Nuara, A.; Gatti, R.; Avanzini, P. The Role of Mirror Mechanism in the Recovery, Maintenance, and Acquisition of Motor Abilities. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, C.; Kraeutner, S.N.; Rieger, M.; Boe, S.G. Learning Motor Actions via Imagery—Perceptual or Motor Learning? Psychol. Res. 2024, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, C.G.A.V.S. Imagery and Motor Learning: A Special Issue on the Neurocognitive Mechanisms of Imagery and Imagery Practice of Motor Actions. Psychol. Res. 2024, 88, 1785–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ida, H.; Fukuhara, K.; Ogata, T. Virtual Reality Modulates the Control of Upper Limb Motion in One-Handed Ball Catching. Front. Sport. Act. Living 2022, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seitz, S.; Schuster-Amft, C.; Wandel, J.; Bonati, L.H.; Parmar, K.; Gerth, H.U.; Behrendt, F. Effect of Concurrent Action Observation, Peripheral Nerve Stimulation and Motor Imagery on Dexterity in Patients after Stroke: A Pilot Study. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambert, K.J.M.; Singhal, A.; Leung, A.W.S. The Lateralized Effects of Parkinson’s Disease on Motor Imagery: Evidence from Mental Chronometry. Brain Cogn. 2024, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Kulvicius, T.; Tamosiunaite, M.; Wörgötter, F. Simulated Mental Imagery for Robotic Task Planning. Front. Neurorobot. 2023, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, H.; Zhang, Y.; Rajabi, N.; Taleb, F.; Yang, Q.; Kragic, D.; Li, Z. Shaping High-Performance Wearable Robots for Human Motor and Sensory Reconstruction and Enhancement. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).