1. Introduction

Natural rubber (NR), primarily consisting of

cis-1,4-polyisoprene, is a naturally synthesized polymer predominantly derived from the

Hevea brasiliensis tree. However, rising demand for NR, coupled with challenges such as price volatility, restricted cultivation regions, susceptibility to environmental stressors, pest infestations, and lengthy maturation periods, has heightened the need for alternative NR sources[

1].

Taraxacum kok-saghyz (TKS), a green and high-yielding rubber-producing plant, presents as an appealing alternative due to its ease of cultivation, rapid harvest cycles, and broad adaptability to various geographic regions[

2,

3]. The main rubber component in TKS is similar to the molecular structure and physical-mechanical properties of Brazilian natural rubber (NR), highlighting the potential of TKS as an alternative source of NR.[

4,

5,

6].

Taraxacum kok-saghyz natural rubber (TKNR) is primarily found in the roots of TKS in latex form, mirroring the structure of NR[

7,

8,

9]. The TKNR content in TKS roots ranges from 2.8% to 28.7%, influenced by factors such as plant strain, cultivation environment, and diurnal temperature variation[

10,

11,

12,

13]. David A. Ramirez-Cadavid and colleagues have conducted extensive research on TKNR extraction methods, initially developing a solvent-based extraction technique to isolate rubber from

Taraxacum kok-saghyz roots (TK)[

14]. Subsequently, they advanced a novel aqueous extraction method, and more recently, an alkaline pretreatment approach for TKNR extraction[

15,

16]. Additionally, Shomaila Sikandar et al. identified the thermophilic fungus

STm as a source of hydrolytic enzymes that facilitate TKNR extraction from TKS using enzymatic hydrolysis[

17]. Shuai Zhao and co-researchers developed an extraction method that leverages yeast fermentation to simultaneously produce TKNR and biofuel ethanol from TKS[

18]. Collectively, these advancements have accelerated the progress toward industrial-scale TKNR extraction.

However, several challenges remain. For example, while solvent extraction is effective, it is constrained by high costs, environmental risks, and safety concerns. Aqueous extraction, though promising, can disrupt TKNR’s network structure, requires substantial water resources, and yields TKNR of lower purity. Alkaline and enzymatic extraction methods, while less disruptive, still yield relatively low purity and efficiency[

19], leaving room for optimization in terms of yield and cost-effectiveness[

20,

21].In TKNR extraction, yield and efficiency are essential parameters, as the composition and quality of the extract directly impact TKNR performance, serving as primary metrics for assessing the effectiveness of the extraction process[

22,

23,

24].

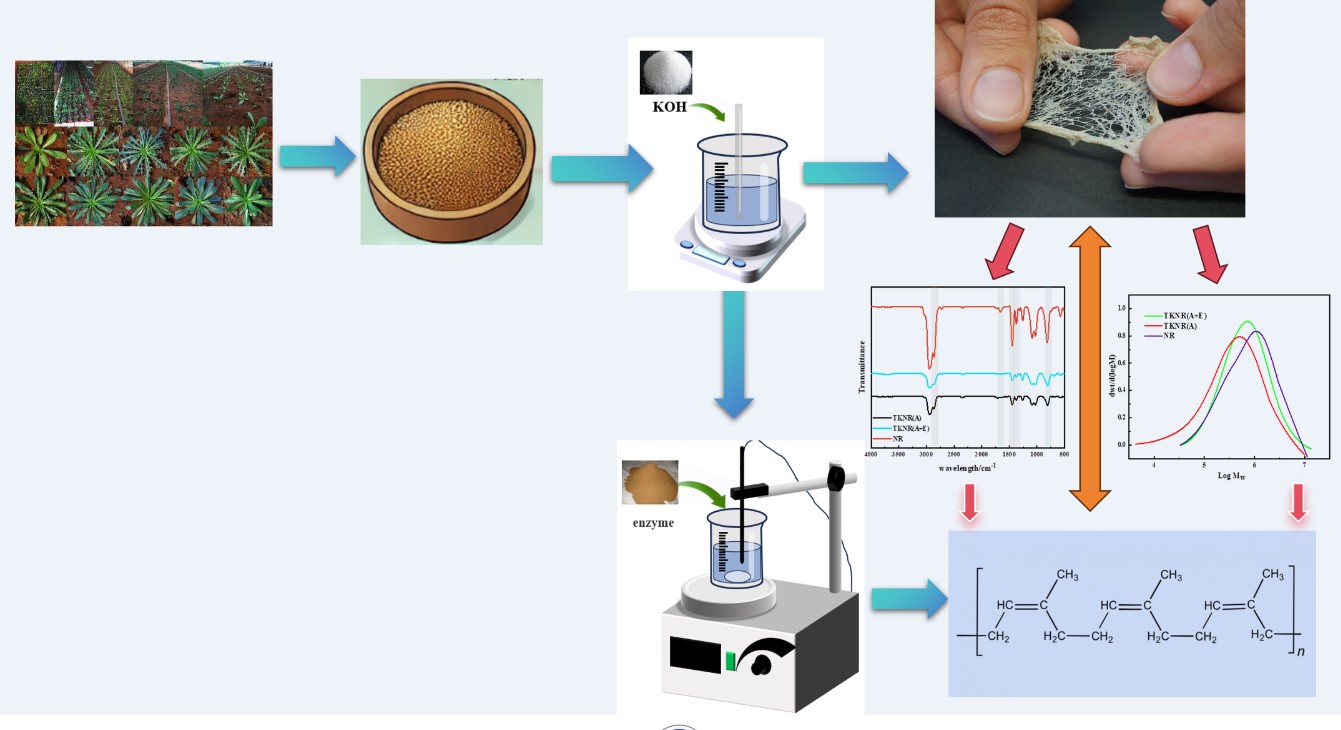

This study evaluates TKNR extraction using two approaches: an alkaline extraction method and a combined approach integrating alkaline treatment with enzymatic hydrolysis. Structural analysis of the extracted TKNR was performed using Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), crosslink density measurement, and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). Thermal stability, glass transition temperature, and crystallinity were further assessed through thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC). The study results show that the TKNR extracted by both methods is highly similar to NR in molecular structure and crosslinking network. The green and efficient extraction method combining alkaline treatment and enzymatic hydrolysis offers significant advantages, providing a theoretical foundation for the industrial production of TKNR.2. Results and Discussion

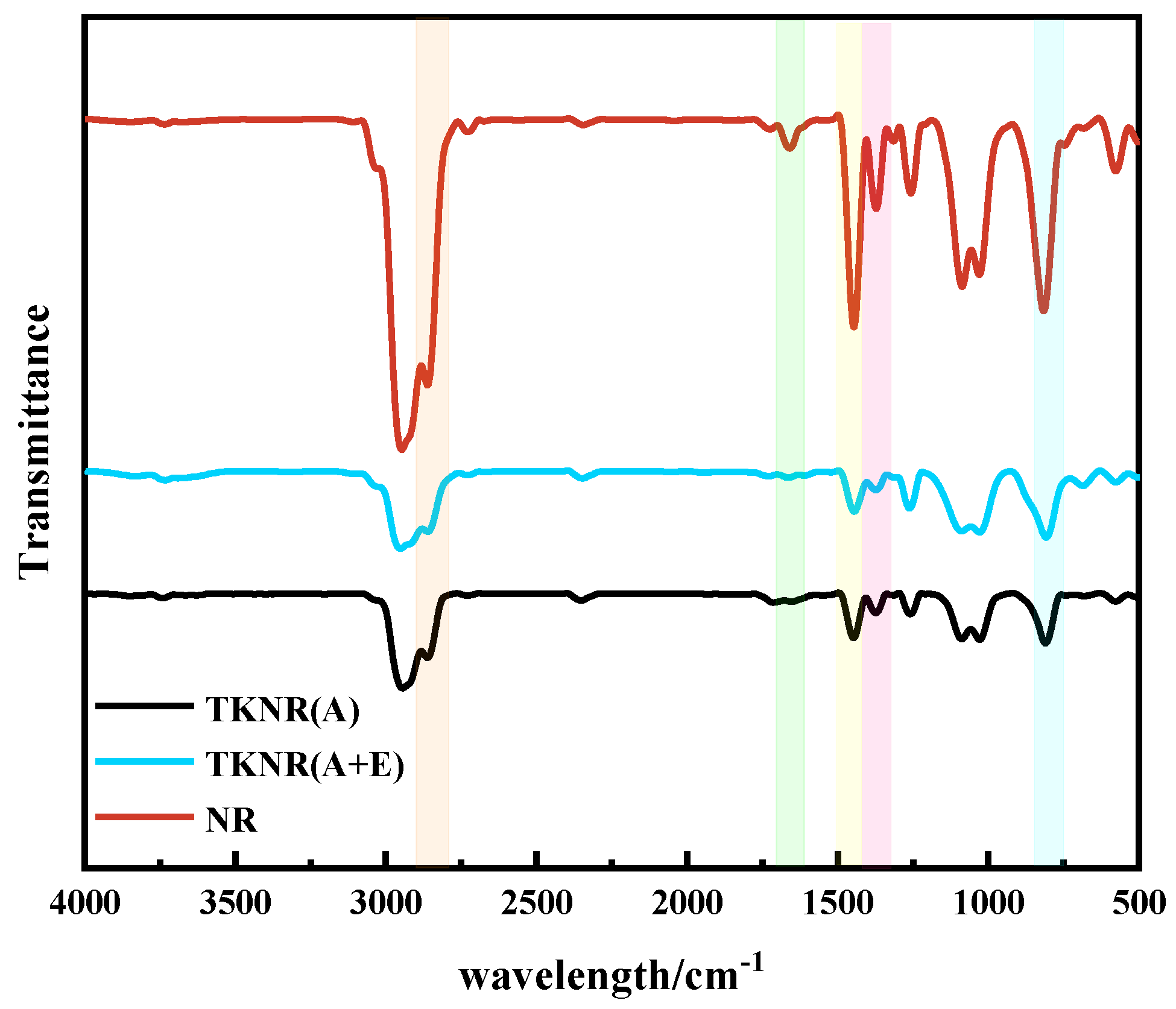

2.1. Analysis of Rubber Molecular Structure

Figure 1 presents the FTIR spectra of NR and TKNR, with characteristic absorption peaks of TKNR observed at 1376 cm⁻¹, corresponding to the symmetric deformation vibration of methyl groups, and at 836 cm⁻¹, indicating the out-of-plane deformation of the C—H bond in cis-disubstituted carbon-carbon double bonds. These peaks, also characteristic of NR, effectively distinguish different forms of polyisoprene. Additional peaks at 2962 cm⁻¹, 2928 cm⁻¹, and 1449 cm⁻¹ correspond to the asymmetric stretching vibration of CH₃, the asymmetric stretching vibration of CH₂, and the antisymmetric deformation vibration of methylene, respectively. The close alignment of these peaks with those in NR indicates that TKNR possesses a structure identical to NR, characterized by a high content of rubber hydrocarbons. However, certain peaks in the TKNR spectrum, including those at 1376 cm⁻¹ and 836 cm⁻¹, exhibit reduced intensities relative to NR, likely due to partial molecular chain degradation or a reduction in functional groups during alkaline or alkaline-enzymatic extraction processes[

25].

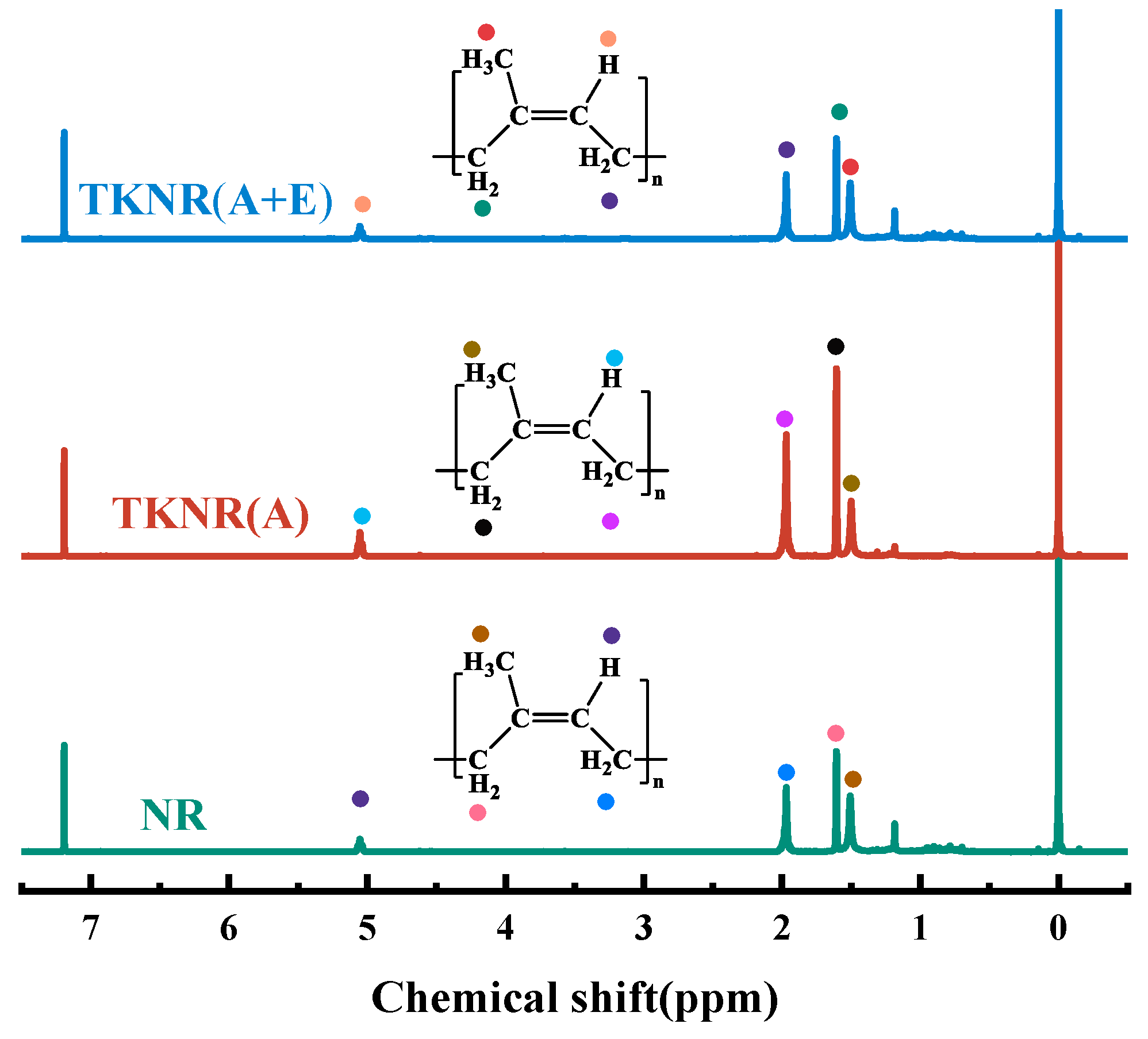

Figure 2 displays the ¹H NMR spectra of NR and TKNR. The peaks at 0 ppm and 7.19 ppm correspond to the internal standard TMS and the deuterated chloroform solvent, respectively. For TKNR, the two —CH₂ peaks appear at 1.61 ppm and 1.97 ppm, the C-H peak at 5.05 ppm, and the —CH₃ peak at 1.50 ppm. These peak positions are nearly identical to those observed in NR, confirming that both materials exhibit the same cis-1,4-polyisoprene structure. However, the overall absorption intensities in TKNR are generally lower than in NR, suggesting potential partial degradation or reduced rubber hydrocarbon content as a result of the extraction process. Notably, the —CH₃ and —CH₂ peaks at 1.50 ppm and 1.61 ppm show significantly lower intensities in TKNR than in NR, reflecting the impact of extraction on molecular integrity, which leads to a reduction in characteristic group concentrations[

26]. Prolonged alkaline treatment in the alkaline-based method appears to result in more pronounced molecular chain disruption.

2.2. Molecular Weight and Distribution Characteristics of Rubber

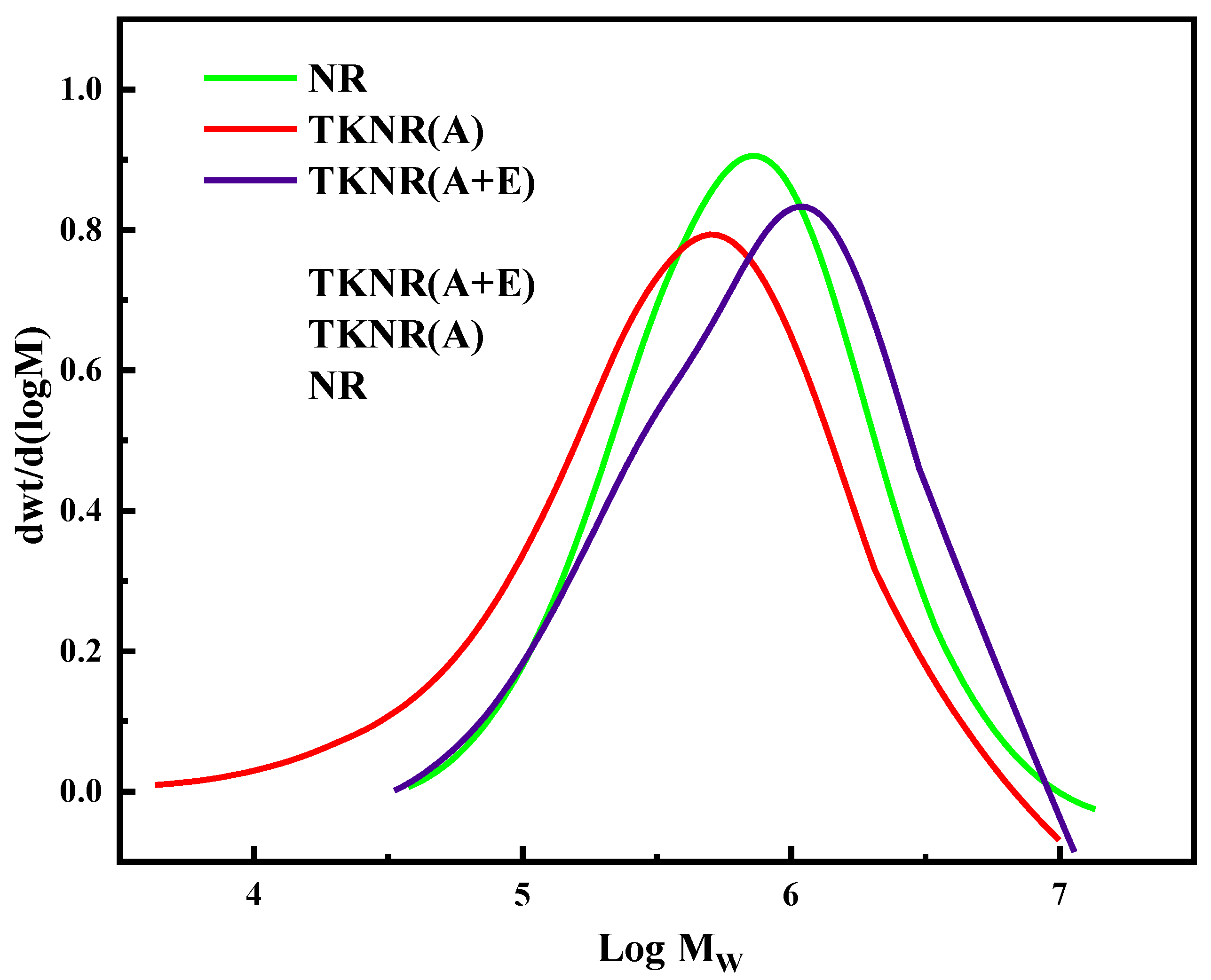

Table 1 presents the molecular weights of NR and TKNR extracted by two methods, and Figure3 illustrates their molecular weight distributions. According to the comparisons of weight-average molecular weight (

Mw), number-average molecular weight (

Mn), and polydispersity index (PDI) in

Table 1 and

Figure 4, NR exhibits an Mw of 1.30 × 10⁶, Mn of 4.4 × 10⁵, and a PDI of 3.0, reflecting a broad and relatively uniform molecular weight distribution.

In contrast, TKNR extracted by the alkali-based method (A) shows an Mw of 7.0 × 10⁵, Mn of 1.6 × 10⁵, and a PDI of 4.6, indicating a significantly lower molecular weight and a higher PDI. This suggests a broader and less uniform molecular weight distribution, likely due to an increase in low-molecular-weight components resulting from molecular chain degradation during extraction. On the other hand, TKNR extracted by the alkali-assisted enzymatic method (A+E) exhibits an Mw of 1.10 × 10⁶, Mn of 4.1 × 10⁵, and a PDI of 2.5, closer to the values observed for NR. This indicates that enzymatic extraction causes less molecular chain degradation, retains more high-molecular-weight components, and produces a more uniform molecular weight distribution[

27].

The molecular weight distribution curves further corroborate these findings. The curve for TKNR extracted via the alkali-based method (A) shifts towards lower molecular weights and has a reduced peak, while the curve for TKNR extracted by the enzymatic method (A+E) closely resembles that of NR, with a higher peak and narrower distribution. This suggests that the enzymatic method better preserves the integrity of rubber molecular chains, leading to a more consistent molecular weight distribution. Thus, compared to the alkali-based method, the enzymatic method achieves superior retention of both molecular weight and distribution uniformity in TKNR.

2.3. Analysis of the Main Components of Rubber

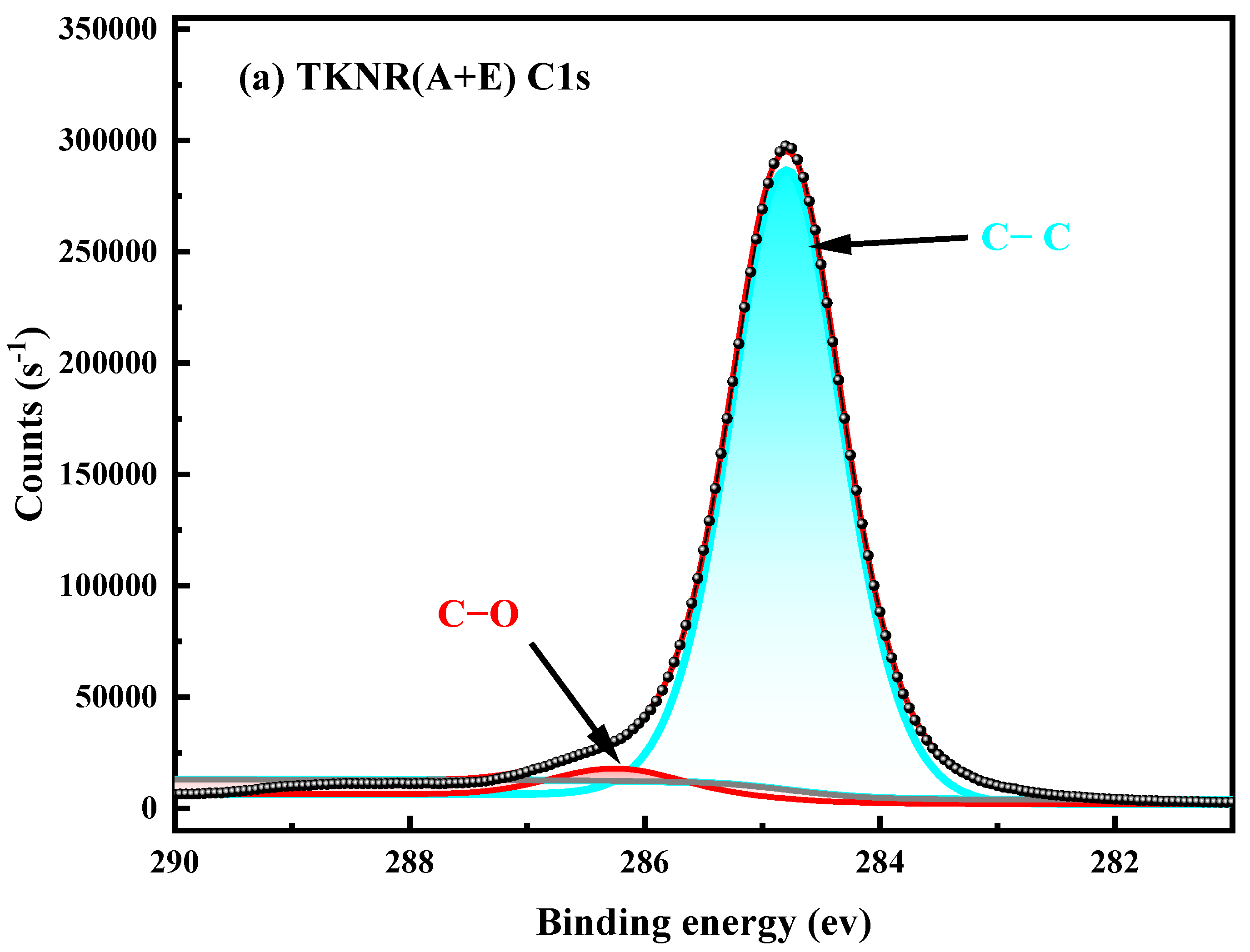

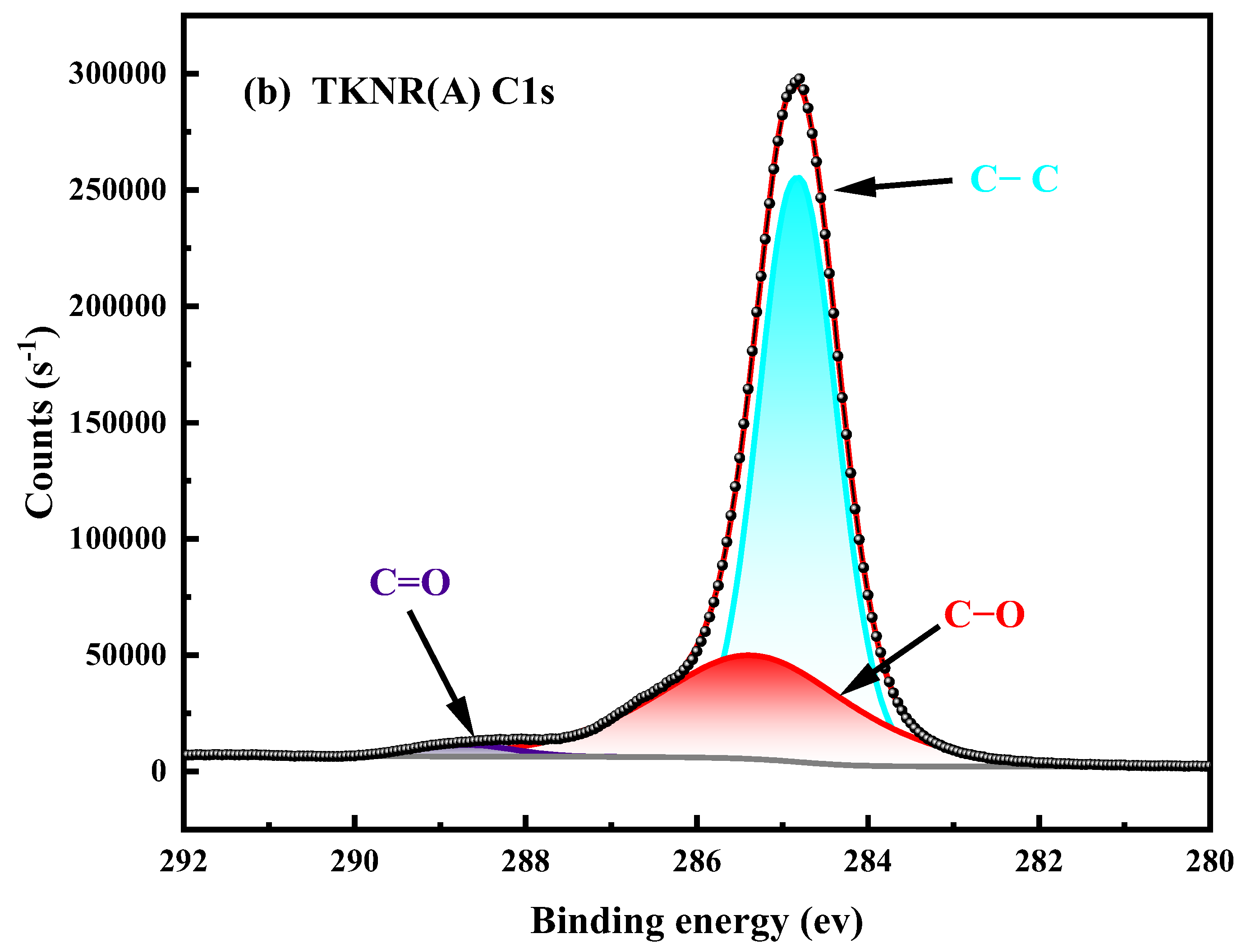

Figure 4 presents the XPS C spectra, highlighting the influence of different extraction methods on the structure and chemical composition of TKNR. In

Figure 4a, the C-C main peak at 285.0 eV for TKNR extracted via the alkaline-enzyme method aligns closely with that of NR, indicating effective preservation of the polyisoprene backbone structure. Additionally, the C-O secondary peak is relatively minor, and the C=O peak is nearly absent in the alkaline-enzyme sample, suggesting minimal formation of oxidation products during extraction. This indicates that the mild conditions of the alkaline-enzyme method effectively reduce molecular chain oxidation and degradation, preserving the chemical purity and structural integrity of TKNR [

28].

Conversely, TKNR extracted using the alkaline method (

Figure 4b) also retains the C-C main peak, but exhibits substantially larger C-O and C=O peak areas, indicating a higher degree of oxidation. This increase in oxidation likely results from the harsher extraction conditions of the alkaline method, leading to the formation of more oxidized compounds and impurities. Such oxidation can compromise the chemical purity of the material and potentially reduce its physical properties, such as elasticity and mechanical strength. Therefore, the alkaline-enzyme extraction method demonstrates clear advantages, significantly limiting oxidation-related side reactions and preserving the molecular integrity of TKNR, resulting in chemical characteristics more closely aligned with those of NR.

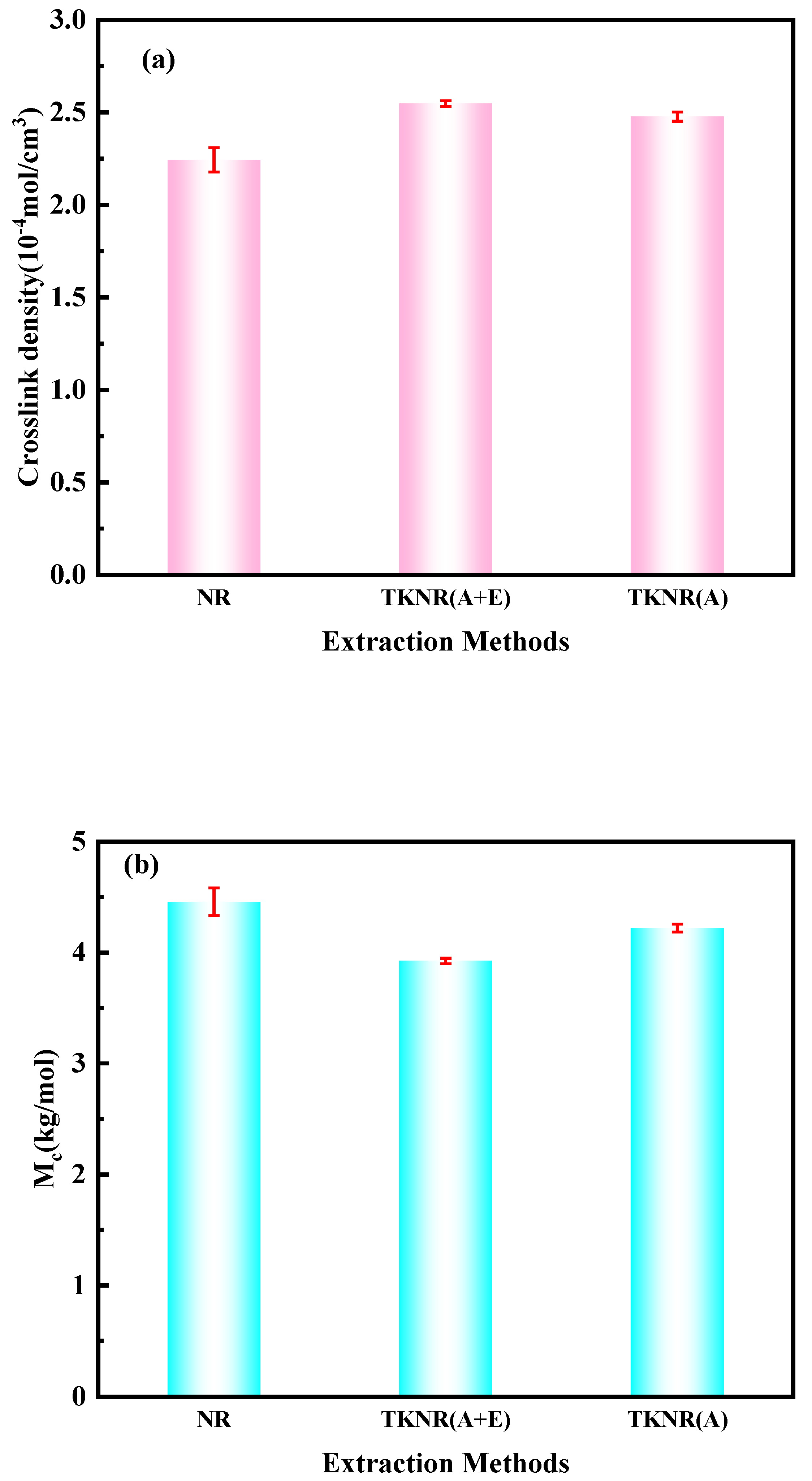

2.4. Analysis of Rubber Crosslink Density

Figure 5 illustrates the crosslink density and molecular weight between crosslinks (Mc) for natural rubber (NR) and

Taraxacum kok-saghyz natural rubber (TKNR).

Figure 5 (a) and 5(b) depict the influence of various extraction methods on the crosslink network structures of TKNR and NR. The crosslink density (ν) of NR is measured at 2.24 × 10⁻⁴ mol/cm³, which is significantly lower than that of TKNR extracted via the alkaline-enzymatic method (2.55 × 10⁻⁴ mol/cm³) and the alkaline method (2.48 × 10⁻⁴ mol/cm³). This observation indicates that both extraction methods result in TKNR exhibiting a higher crosslink density compared to NR.

Moreover, the analysis of Mc reveals that NR has an Mc value of 4.46 kg/mol, which is greater than the values obtained for TKNR via the alkaline-enzymatic method (3.92 kg/mol) and the alkaline method (4.22 kg/mol). This finding suggests that NR possesses greater molecular chain spacing, reflecting a relatively looser crosslink network. In contrast, TKNR extracted using the alkaline-enzymatic method exhibits a smaller Mc and a higher ν, indicative of a denser crosslink network. These results demonstrate that TKNR extracted by both the alkaline-enzymatic and alkaline methods forms a tighter crosslink network than NR, with the alkaline-enzymatic method proving particularly effective in enhancing the crosslink density of TKNR.

2.5. Thermal Stability and Glass Transition Analysis of Rubber

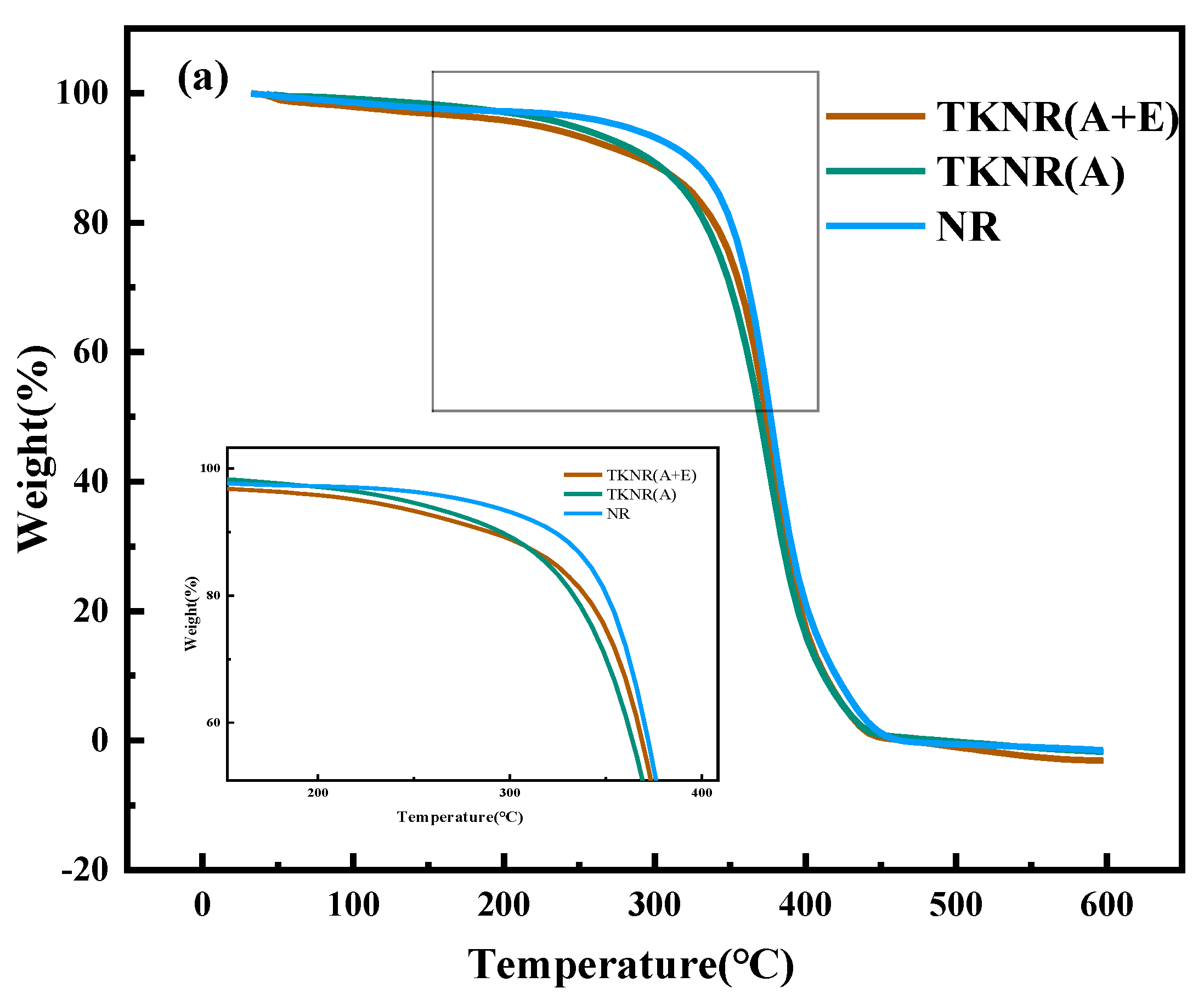

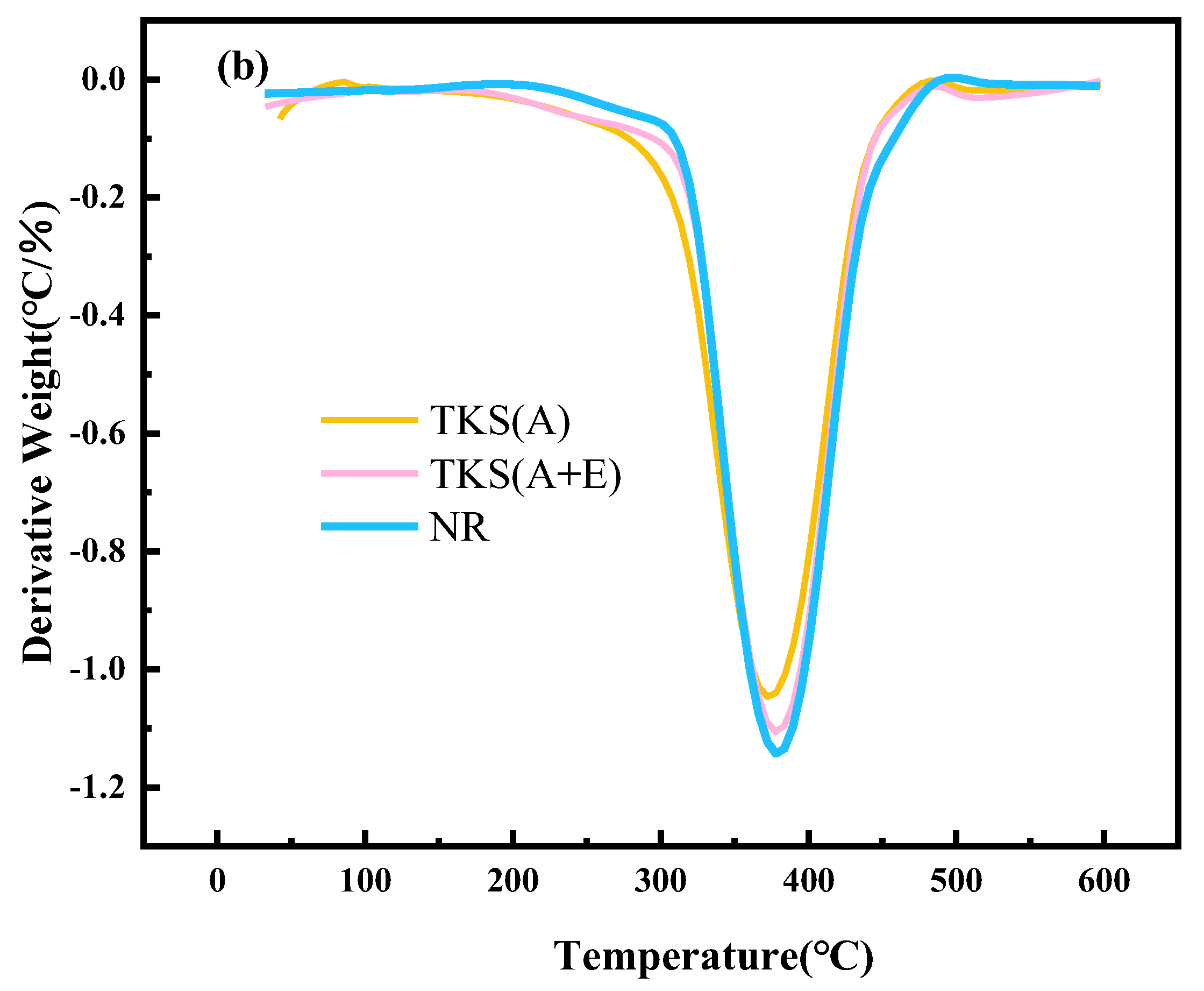

Figures 6(a) and (b) present the thermogravimetric (TG) and derivative thermogravimetric (DTG) curves for natural rubber (NR), Taraxacum kok-saghyz natural rubber (TKNR) extracted via the alkaline method (A), and TKNR extracted via the alkaline-enzymatic method (A+E). The TG and DTG curves clearly indicate that the extraction method significantly influences the thermal stability of TKNR. NR demonstrates a lower initial degradation temperature, which reflects its inferior thermal stability. In contrast, TKNR (A) and TKNR (A+E) exhibit higher initial degradation temperatures, suggesting enhanced thermal stability associated with these extraction methods.

Figure 6.

Thermal stability of NR and TKNR: (a) TG; (b) DTG.

Figure 6.

Thermal stability of NR and TKNR: (a) TG; (b) DTG.

Furthermore, the peak corresponding to the maximum weight loss rate in the DTG curve indicates that TKNR (A+E) experiences a slower thermal decomposition at elevated temperatures, further affirming its superior thermal stability. This improvement can be attributed to the crosslinking reactions induced by enzymatic treatment, which enhance the material's thermal stability[

29].

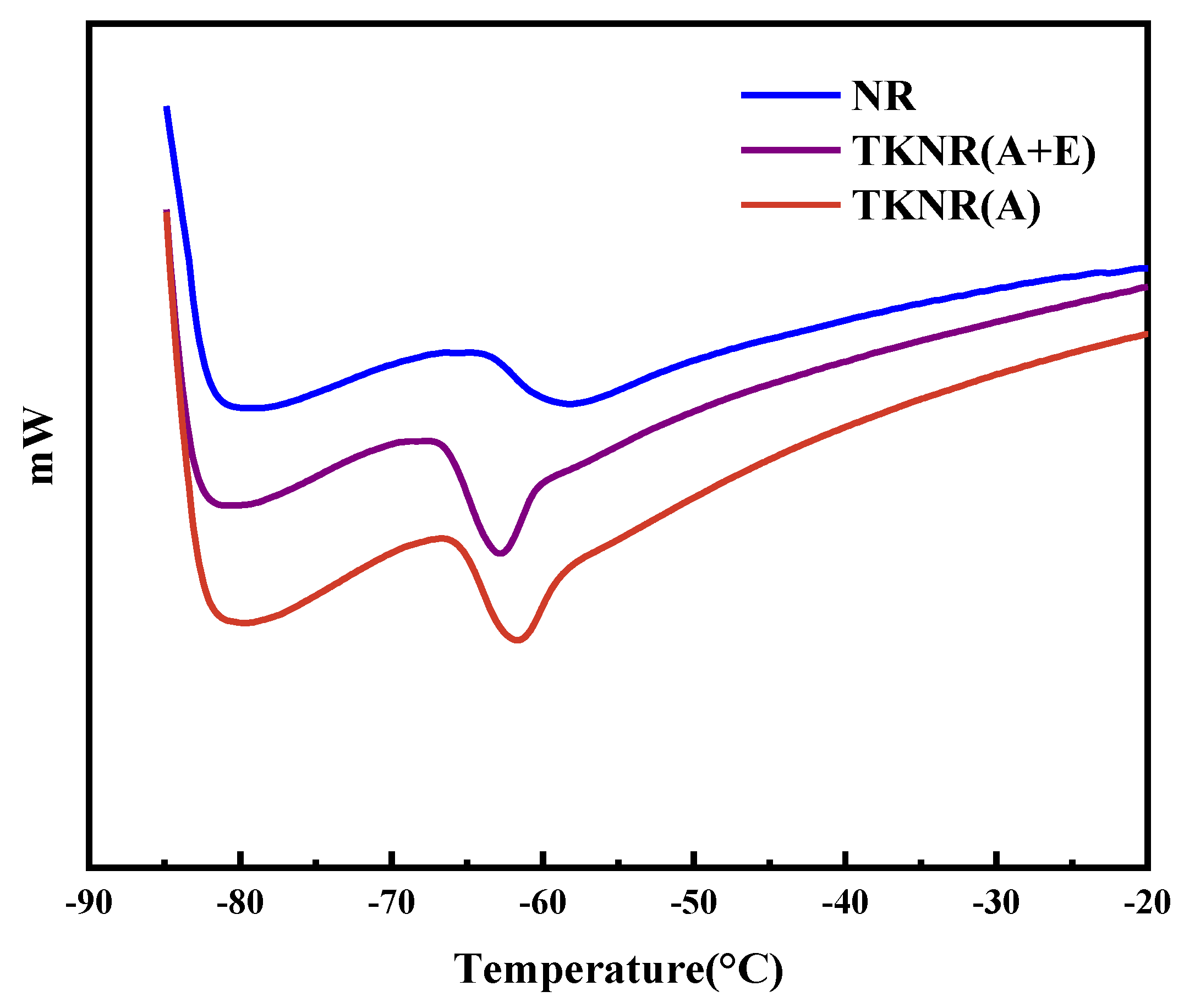

Figure 7 illustrates the differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) curves for NR, TKNR (A), and TKNR (A+E). The DSC curves highlight the effects of various extraction methods on the glass transition temperature (Tg) and crystallinity of the samples. NR exhibits the lowest Tg, indicative of its higher molecular chain flexibility. Conversely, both TKNR (A) and TKNR (A+E) display elevated Tg values, with TKNR (A+E) showing the most significant increase, suggesting that enzymatic treatment enhances the rigidity of the molecular chains.

Additionally, the crystallinity of TKNR extracted via both the alkaline and alkaline-enzymatic methods is markedly higher than that of NR, with TKNR (A+E) exhibiting the most pronounced melting peak. This observation suggests that enzymatic treatment promotes a more orderly arrangement of molecular chains, thereby enhancing the material's crystallinity[

30]. Consequently, the alkaline-enzymatic extraction method not only effectively improves the thermal stability of TKNR but also enhances its overall thermal performance by increasing Tg and crystallinity.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

Dried Taraxacum kok-saghyz roots were obtained from the Agricultural Science Research Institute of the Ili Autonomous Prefecture, Xinjiang. Natural rubber (NR) was sourced from the Jinlian Processing Branch of Hainan Natural Rubber Industry Group Co., Ltd. Potassium hydroxide (KOH, 90%), dichloromethane (CH₂Cl₂, 98%), and tetrahydrofuran (THF, AR, ≥99.5%) were supplied by Guangzhou Chemical Reagent Factory. Pectinase (500 U/mg), cellulase (400 U/mg), and sodium citrate buffer (0.5 M, pH 6.0) were purchased from Aladdin Reagent (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. Deuterated chloroform (D, 99.8%) was acquired from Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd., and toluene (AR, ≥99.5%) was obtained from Xilong Chemical Co., Ltd.

3.2. Methods

3.2.1. Alkaline Method (A) for Extracting Taraxacum kok-saghyz Rubber

T. kok-saghyz (TKS) roots are composed of root bark, root flesh, and root core, each with distinct TKNR concentrations: the root bark contains the highest TKNR content, the root flesh has a lower amount, and the root core is nearly devoid of TKNR. To enhance extraction efficiency and purity, the root bark and root core were processed separately. TKNR was extracted from the root bark using an alkaline treatment, while the minimal TKNR in the root flesh was recovered through acid treatment. First, 300 g of cleaned and pre-dried TKS roots (dried for 1–3 days) were boiled in water for 2 hours at a solid-to-liquid ratio of 1:5, with this boiling process repeated three times. Following boiling, the root bark, flesh, and core were separated. The root bark was then treated with 3% potassium hydroxide (KOH) at 100°C for 2 hours, with intermittent stirring to promote reaction efficiency. Upon completion, the treated bark was thoroughly rinsed and subjected to centrifugation at 4000–5000 rpm for 15 minutes using a GL-21M centrifuge (Xiangyi Instrument Co., Ltd.). The upper layer containing the floating rubber was collected and subsequently dried.

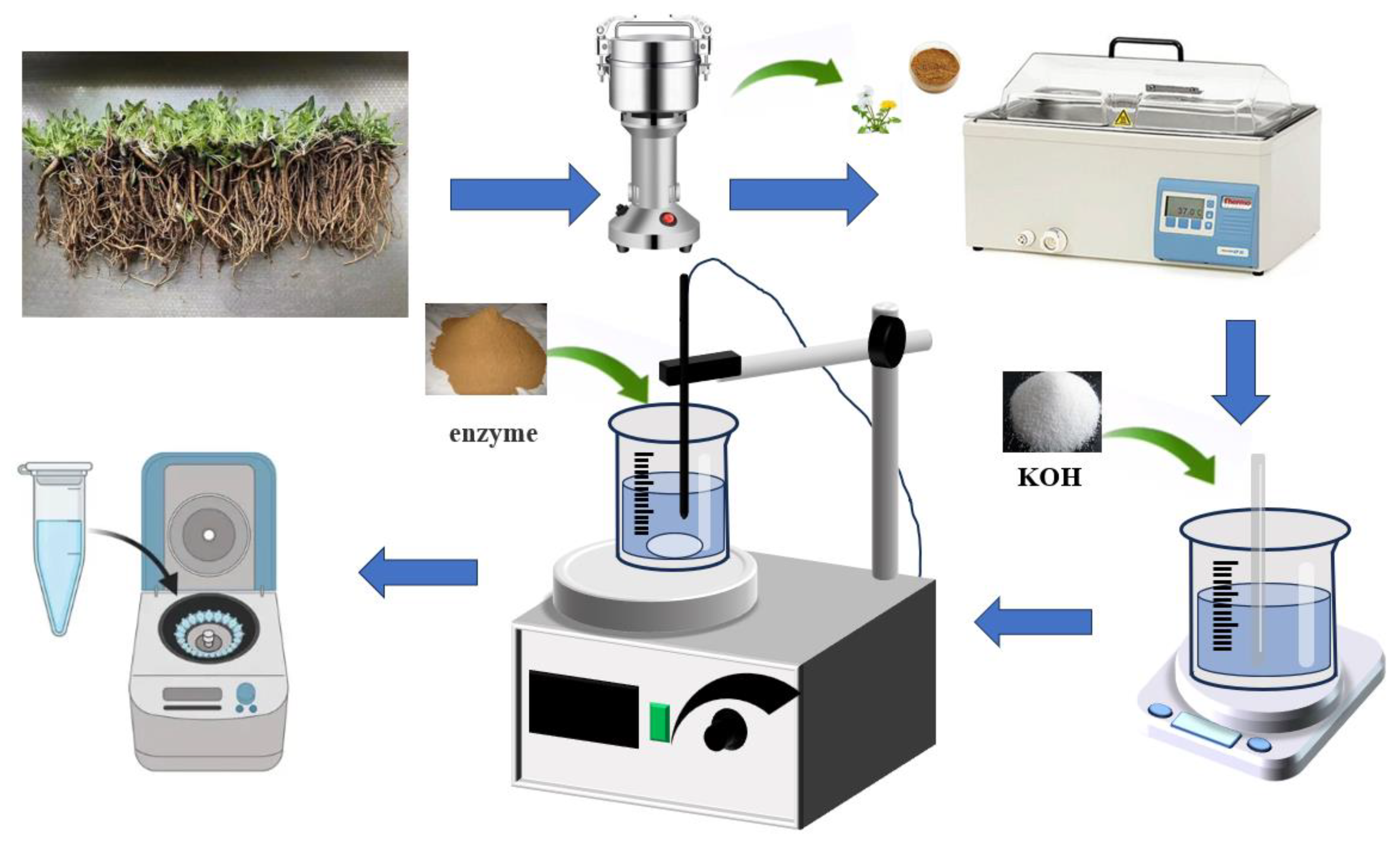

3.2.2. Alkaline Treatment Combined with Enzymatic Hydrolysis (A+E) for Extracting Taraxacum kok-saghyz Rubber

To extract TKNR, 300 g of cleaned and dried Taraxacum kok-saghyz (TKS) roots were crushed and boiled in water at 100°C for 30 minutes. The mixture was filtered through a 178 μm (80 mesh) sieve, and this process was repeated three times.

The residue was then dried, and the filtrate was collected and dried separately to obtain inulin as a by-product. The dried residue was weighed, and KOH was added at a ratio of 60 mg KOH per gram of dry root, dissolved in 500 mL of deionized water. This mixture was treated at 120°C for 30 minutes, then filtered, and lignin was precipitated by acidifying the filtrate. The residue was subsequently washed with 5 L of deionized water, followed by an additional 2 L, and allowed to stand at 4°C overnight to remove residual alkali ions. After further filtration and washing, the residue was suspended in 1.5 L of deionized water, and pectinase and cellulase were added at a 1.5:1 ratio (42 mg pectinase and 27.5 mg cellulase per gram of dry root). The pH of the mixture was adjusted using 0.5 M sodium citrate buffer (pH 5.5). The mixture was then sealed in a beaker and stirred magnetically at 50°C and 200 rpm for 48–72 hours.

Upon completion of the enzymatic reaction, the mixture was centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 30 minutes at 4°C. The upper layer containing the floating rubber was carefully collected, dried, and stored. An illustration of the extraction process is presented in

Figure 8.

3.3. Characterizations

3.3.1. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

FTIR analysis was performed using a Perkin-Elmer Spectrum One FTIR spectrometer (USA). A sample of 5–10 mg was dissolved in dichloromethane, and the resulting solution was applied to a potassium bromide (KBr) pellet. The solvent was evaporated under an infrared lamp, after which the KBr pellet was positioned in the transmission accessory. The analysis was conducted in transmission mode (TR) over a scan range of 4000–500 cm⁻¹, with a total of 32 scans recorded.

3.3.2. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy (¹H NMR)

¹H NMR analysis was conducted using a Bruker AVANCE NEO 400 MHz spectrometer (Bruker BioSpin AG, Switzerland). A sample of 5–10 mg was dissolved in deuterated chloroform (CDCl₃), filtered through a 0.22 μm membrane, and subsequently transferred into an NMR tube. The analysis was performed to obtain the ¹H NMR spectrum.

3.3.3. Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC)

Molecular weight and molecular weight distribution were analyzed using a Waters 1515 GPC system (Waters, USA). A sample of 5-10 mg was dissolved in tetrahydrofuran (THF) and protected from light in an amber bottle. After complete dissolution, the solution was filtered through a 0.22 μm membrane and analyzed for 45 minutes to determine molecular weight and polydispersity.

3.3.4. X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS)

XPS measurements were conducted using a Thermo Fisher Scientific K-Alpha XPS spectrometer (USA). A sample of 20–30 mg was cut into small pieces and adhered to the sample holder using conductive tape. C 1s spectra were recorded to analyze the composition of the rubber.

3.3.5. Crosslink Density Analysis

Crosslink density was determined using a VTNMR20-010V-T crosslink density analyzer (Shanghai Niumag Corporation). A sample of appropriate size was placed into a glass tube and stabilized in the magnetic field before measurement. Crosslink density and rubber network structure were calculated using the XLD-2 model.

3.3.6. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

TGA was performed using a Mettler Toledo TGA/DSC 1/1100 thermogravimetric analyzer (Switzerland). The sample was heated from 25°C to 600°C at a rate of 10°C/min under a nitrogen flow of 60.0 mL/min to assess thermal stability.

3.3.7. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

DSC analysis was conducted using a METTLER TOLEDO DSC822e differential scanning calorimeter (Switzerland). The sample was heated from -85°C to 100°C at a rate of 10°C/min under a nitrogen flow of 60.0 mL/min to determine the glass transition temperature and crystallinity.

4. Conclusions

The FTIR and ¹H NMR analyses indicate that both the alkaline and alkaline-enzymatic extraction methods successfully preserved the cis-1,4-polyisoprene backbone structure of Taraxacum kok-saghyz natural rubber (TKNR), which is similar to that of natural rubber (NR). However, TKNR extracted via the alkaline-enzymatic method exhibited less degradation of molecular chains, with smaller losses in the intensity of C-H deformation and methyl symmetric deformation vibrations, suggesting better protection of the molecular chain integrity. Additionally, XPS results revealed that the alkaline-enzymatic method effectively minimized oxidation side reactions that typically occur under harsh extraction conditions, producing fewer oxidation products, and the chemical properties of the extracted TKNR were found to be closer to those of NR. Molecular weight and distribution analysis further demonstrated that the alkaline-enzymatic extracted TKNR exhibited a weight-average molecular weight (Mw) and polydispersity index (PDI) closer to NR, with lower molecular chain degradation. Gel content analysis showed that the alkaline-enzymatic method provided greater stability in maintaining the rubber network structure. Crosslink density and molecular weight between crosslinks (Mc) analyses indicated that the crosslink network was denser and more uniform compared to the alkaline method. Furthermore, thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) confirmed that TKNR obtained via this method had enhanced thermal stability and a lower glass transition temperature (Tg).Overall, the alkaline-enzymatic extraction method not only achieves a chemical purity close to that of NR, but also offers superior molecular structure integrity and physical properties compared to the alkaline method, making it the most promising approach for extracting Taraxacum kok-saghyz natural rubber to date.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.Z.; methodology, J.Z.; software, J.Z.; validation, J.Z., X.L. and L.L.; formal analysis, J.Z., F.Z.,Q.Z., R.Y., Y.Z.; investigation, J.Z.; resources, X.L. and L.L; data curation, J.Z., F.Z.,Q.Z., Y.Z. and R.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, J.Z.; writing—review and editing, X.L. and R.T.; visualization, J.Z.; supervision, X.L. and L.L.; project administration, X.L. and L.L; funding acquisition, X.L. and L.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Hainan Province Science and Technology Special Fund (ZDYF2022XDNY209); Central Public-interest Scientific Institution Basal Research Fund (1630122022006); National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFD23012053-4); the earmarked fund for Tropical High-efficiency Agricultural Industry Technology System of Hainan University (THAITS-3); the Key Laboratory of Natural Rubber Processing of Hainan Province (No. HNXJ2024601); Hainan Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (521RC1039).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Yamashita, S.; Takahashi, S., Molecular Mechanisms of Natural Rubber Biosynthesis. Biochem. 2020, 89, 821-851. [CrossRef]

- Demirbas, M. F.; Balat, M., Recent advances on the production and utilization trends of bio-fuels: A global perspective. Manag. 2006, 47, 2371-2381. [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.; Yang, D.-d.; Yu, X.-c.; Xu, C., Multi-omics-driven development of alternative crops for natural rubber production. J. Integr. Agric. 2023, 22, 959-971. [CrossRef]

- Iaffaldano, B.; Cardina, J.; Cornish, K. Hybridization Potential between the Rubber Dandelion and Common Dandelion. Ecosphere 2018, 9,e02115. [CrossRef]

- Gabit, B.; Karina, G.; Gulnar, G.; Kairat, U.; Yaroslav, G.; Aleksey, C.; Bulat, K. Multilocus DNA Polymorphism of Some Rubber-bearing Dandelions (Taraxacum spp.) of Russia and Kazakhstan. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2022, 69, 335-348. [CrossRef]

- Keener, H. M.; Shah, A.; Klingman, M.; Wolfe, S.; Pote, D.; Fioritto, R. Progress in Direct Seeding of an Alternative Natural Rubber Plant, Taraxacum kok-saghyz (L.E. Rodin). Agronomy 2018, 8, 9. [CrossRef]

- Saeedi, F.; Naghavi, M. R.; Sabokdast, M.; Jariani, P. Taraxacum kok-saghyz L.E. Rodin as a Novel Potential Source of Natural Rubber in Iran: A Good Candidate for Commercial Use. Iran. Polym. J. 2023, 32, 1257-1269. [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Cadavid, D. A.; Cornish, K.; Michel, F. C. Taraxacum kok-saghyz (TK): Compositional Analysis of a Feedstock for Natural Rubber and Other Bioproducts. Ind. Crops Prod. 2017, 107, 624-640. [CrossRef]

- Abdul Ghaffar, M. A.; Meulia, T.; Cornish, K. Laticifer and Rubber Particle Ontogeny in Taraxacum kok-saghyz (Rubber Dandelion) Roots. Microsc. Microanal. 2016, 22, 1034-1035. [CrossRef]

- King-Smith, N.; Molnar, K.; Blakeslee, J. J.; McMahan, C. M.; Pillai, A. S.; Mutalkhanov, M.; Puskas, J. E.; Cornish, K. Extractable Latex Yield from Taraxacum kok-saghyz Roots is Enhanced by Increasing Rubber Particle Buoyancy. Ind. Crops Prod. 2023, 206,117698. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, B. X.; Ding, G. H.; Ma, J. J.; Wang, L. L.; Yu, L.; Ruan, X. Y.; Zhang, X. Y.; Zhang, W. F.; Wang, X. C.; Xie, Q. L. Comparison of Morphological Characteristics and Determination of Different Patterns for Rubber Particles in Dandelion and Different Rubber Grass Varieties. Plants 2020, 9,1561. [CrossRef]

- Gao, S. K.; Guo, M. M.; Gao, J. Q.; Huang, Z. J.; Gan, M.; Zhang, J. C.; Dong, Y. Y. Rapid Determination of Rubber Content Using a Pyrolyzer Hyphenated with a Miniaturized Mass Spectrometer. Separations 2024, 11,103. [CrossRef]

- Martirosyan, L. Y.; Goldberg, V. M.; Barashkova, I. I.; Kasparov, V. V.; Martirosyan, Y. T.; Motyakin, M. V.; Gaydamaka, S. N.; Varfolomeev, S. D. Quantitative Determination of Natural Rubber Content of Taraxacum kok-saghyz E. Rodin Plants Using Spin Probe Method of Electron Paramagnetic Resonance Spectroscopy. Biophysics 2023,68,591-595. [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Cadavid, D. A.; Valles-Ramirez, S.; Cornish, K.; Michel, F. C. Simultaneous Quantification of Rubber, Inulin, and Resins in Taraxacum kok-saghyz (TK) Roots by Sequential Solvent Extraction. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 122, 647-656. [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Cadavid, D. A.; Cornish, K.; Hathwaik, U.; Kozak, R.; McMahan, C.; Michel, F. C. Development of Novel Processes for the Aqueous Extraction of Natural Rubber from Taraxacum kok-saghyz (TK). J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2019, 94, 2452-2464. [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Cadavid, D. A.; Hathwaik, U.; Cornish, K.; McMahan, C.; Michel, F. C. Alkaline Pretreatment of Taraxacum kok-saghyz (TK) Roots for the Extraction of Natural Rubber (NR). Biochem. Eng. J. 2022, 181,108376. [CrossRef]

- Sikandar, S.; Ujor, V. C.; Ezeji, T. C.; Rossington, J. L.; Michel, F. C.; McMahan, C. M.; Ali, N.; Cornish, K. STm: A Source of Thermostable Hydrolytic Enzymes for Novel Application in Extraction of High-quality Natural Rubber from Taraxacum kok-saghyz (Rubber Dandelion). Ind. Crops Prod. 2017, 103, 161-168. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Jie, X.; Ma, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, J. C.; Li, Y. S.; Nie, Q. H.; Ma, Y. Preparation of Rubber and Biofuel Ethanol Simultaneously by the Yeast Fermentation Process. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 24185-24197. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, R.; Shen, Z. L.; Si, R. Z.; Polaczyk, P.; Li, Y. C.; Zhou, H. Y.; Huang, B. S. Alkali-activated Slag (AAS) and OPC-based Composites Containing Crumb Rubber Aggregate: Physico-mechanical Properties, Durability and Oxidation of Rubber upon NaOH Treatment. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 367,132896. [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, Y.; Hu, B.; Liao, S.; Liao, X.-X. Composition Properties of Rubber from Parts of Taraxacum kok-saghyz Roots. J. Rubber Res. 2022, 24, 607-613. [CrossRef]

- Piccolella, S.; Sirignano, C.; Pacifico, S.; Fantini, E.; Daddiego, L.; Facella, P.; Lopez, L.; Scafati, O. T.; Panara, F.; Rigano, D. Beyond Natural Rubber: Taraxacum kok-saghyz and Taraxacum brevicorniculatum as Sources of Bioactive Compounds. Ind. Crops Prod. 2023, 195,116446. [CrossRef]

- Buranov, A. U.; Elmuradov, B. J. Extraction and Characterization of Latex and Natural Rubber from Rubber-bearing Plants. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 734-743. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Ji, H.; Zhang, C.; Liu, A. Optimization of Extraction Process from Taraxacum officinale Polysaccharide and Its Purification, Structural Characterization, Antioxidant and Anti-tumor Activity. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2019, 14, 194-206. [CrossRef]

- Olsen, K. M.; Li, L.-F. Rooting for New Sources of Natural Rubber. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2018, 5, 89. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S. Q.; Chen, Y. H.; Han, D. R.; Tian, X. F.; Ma, D. L.; Jie, X.; Zhang, J. C. Extraction Process and Characterization of Taraxacum kok-saghyz (TKS) Latex. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25351. [CrossRef]

- Salehi, M.; Bahmankar, M.; Naghavi, M. R.; Cornish, K. Rubber and Latex Extraction Processes for Taraxacum kok-saghyz. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 178, 114562. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Guo, T. Y.; Ma, X.; Liu, J. H.; Dong, Y. Y.; Zhang, J. C. Rational Rubber Extraction and Simultaneous Determination of Rubber Content and Molecular Weight Distribution in Taraxacum kok-saghyz Rodin by Size-Exclusion Chromatography. Chromatographia 2019, 82, 1459-1466. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, T.; Lenders, M.; Hillebrand, A.; van Deenen, N.; Munt, O.; Reichelt, R.; Eisenreich, W.; Fischer, R.; Prüfer, D.; Gronover, C. S. Characterization of Rubber Particles and Rubber Chain Elongation in Taraxacum kok-saghyz. BMC Biochem. 2010, 11. [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, Y.; Junkong, P.; Ohashi, T.; Phakkeeree, T.; Sakaki, Y.; Tohsan, A.; Kohjiya, S.; Cornish, K. Strain-induced Crystallization Behaviour of Natural Rubbers from Guayule and Rubber Dandelion Revealed by Simultaneous Time-resolved WAXD/tensile Measurements: Indispensable Function for Sustainable Resources. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 95601-95610. [CrossRef]

- Musto, S.; Barbera, V.; Maggio, M.; Mauro, M.; Guerra, G.; Galimberti, M. Crystallinity and Crystalline Phase Orientation of Poly(1,4-cis-isoprene) from Hevea brasiliensis and Taraxacum kok-saghyz. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2016, 27, 1082-1090. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).