1. Introduction

Anisakis simplex is a pathogenic nematode belonging to the genus

Anisakis, family Anisakidae, and order Ascaridida. Human anisakiasis is a gastrointestinal tract parasitic infection caused by third-stage larvae (L3) of

A. simplex. The life cycle of

Anisakis nematodes involves marine fish, squid, and crustaceans as intermediate or paratenic hosts and marine mammals as definitive hosts [

1]. Humans are accidental hosts and are infected by consuming raw or inadequately cooked fish containing

Anisakis L3 larvae. Therefore, infection has been directly linked to eating habbits.

Symptoms of anisakiasis include severe abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting caused by damage to the human gastrointestinal tract, primarily the stomach and intestines, secondary to mucosal and submucosal penetration of

Anisakis L3 larvae [

2]. In addition to the pathogenic effects of tissue damage, allergic reactions in sensitized humans can be caused by

Anisakis larvae. In 1990, the first allergic reaction to

Anisakis-contaminated fish was reported in Japan by Kasuya et al, who pointed out the allergenic potency of

Anisakis antigens, in addition to active gastrointestinal tract larval penetration [

3]. Shortly after that report, 28 patients allergic to

Anisakis were reported in Spain in 1996 [

4].

Anisakis allergy is primarily caused by consumption of raw seafood containing

A. simplex, and recurrence has been thought to be caused by eating raw or undercooked seafood [

5,

6,

7]. Gastrointestinal allergy is also referred to as gastroallergic anisakiasis (GAA) [

8], which requires long-term management to deal with the acute phase and prevent prolonged allergic symptoms. In addition, most patients develop

Anisakis allergy by oral sensitization, although sensitization by inhalation has been reported in occupational allergy [

9], in which sensitization is caused by

Anisakis worm protein (AWP) and not by live

Anisakis worms.

Anisakis allergy has been mainly reported in Southeast Asia and Western Europe, with Japan having the highest prevalence (>90%) [

10]. Furthermore, in Japan, 10% to 30% of adult allergies are thought to be caused by

Anisakis [

11].

The diagnosis of

Anisakis allergy is mainly based on measurement of specific IgE level using the CAP-FEIA method, measurement of total IgE level, and skin prick test [

11,

12]. In addition, the BAT method for measuring specific IgE levels in blood cells has been reported to correlate well with symptoms [

13]. Another possible tool is the IgE crosslinking–induced luciferase expression (EXiLE) test [

14,

15,

16], which is a convenient in vitro method of measuring the function of specific IgE antibodies using cultured cells without using patient blood cells for the diagnosis of

Anisakis allergy. In this study, we aimed to examine the utility of the EXiLE method for the diagnosis and long-term management of

Anisakis allergy by comparing it with the CAP-FEIA method and investigating fluctuations in specific IgE blood levels over time in patients detected to have allergic reactions by the EXiLE method.

In particular, we compared the results of the EXiLE method with the specific IgE levels detected by the CAP-FEIA method and evaluated fluctuations in specific IgE blood levels over time in patients detected to have allergic reactions by the EXiLE method.

To the best of our knowledge, this was the first study to demonstrate the application of the EXiLE test.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Anisakis Worm Proteins

Species plural identification as

A. simplex nematodes was performed using a PCR-based method [

17]. After being collected from the abdomen of a chub mackerel (

Scomber japonicus) purchased at local markets in Ehime, Japan,

A. simplex L3 larvae were washed in PBS and immediately frozen at −20°C until use. For antigen preparation, 10 larvae were suspended in 0.8 mL of PBS containing a protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich, Burlington, MA, USA); ground with biomarker (Nippi Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan); and sonicated for 30 s 10 times in an ultrasonic crushing device (BIORUPTORII, Sonic Bio Co., Ltd., Kanagawa, Japan). After centrifugation at 12,000 g at 4°C for 5 min, protein extracts were obtained and used the antigen sample (i.e., AWP) in the experiment. Protein concentrations were determined using Protein Assay CBB solution (# 29449-44, Nacalai tesque, Kyoto, Japan ). The protein solutions were stored in aliquots at −80°C until use.

2.2. Analysis of Serum Samples

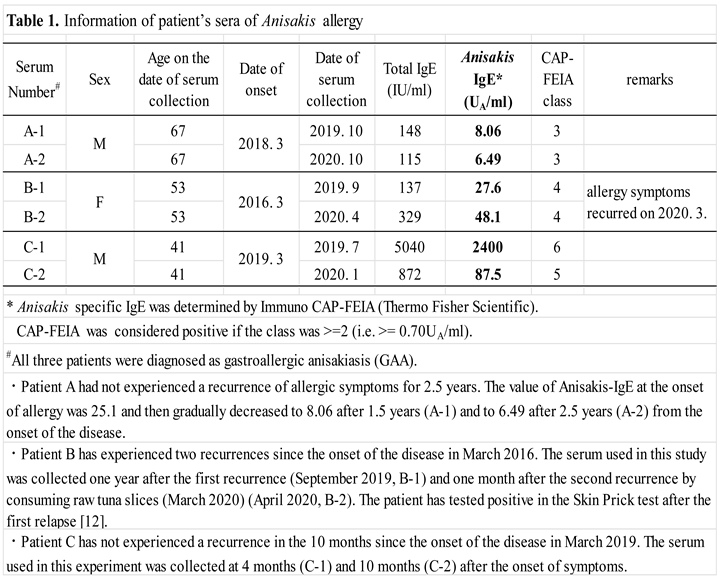

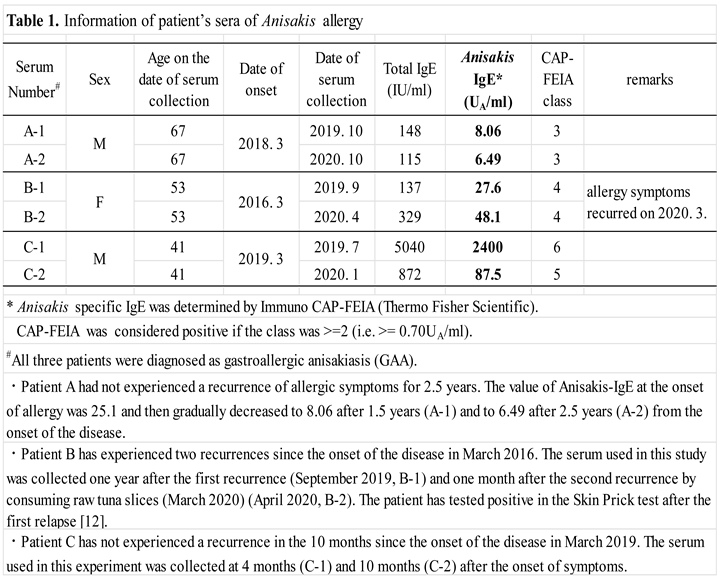

This study was approved by the ethics committee of the National Hospital Organization, Sagamihara National Hospital, Okayama University of Sciences, Teikyo Heisei University. Six serum types were collected from three patients during consultation at the first visit and after 6–12 months. The total and Anisakis-specific IgE levels in each serum sample were measured using ImmunoCAP-FEIA at the date of serum collection. Results of serum sample analyses are presented in Table 1. Pooled serum samples from healthy donors were purchased from Cosmo Bio (Tokyo, Japan) and used as negative controls.

2.3. IgE Immunoblotting

First, after adjusting the AWP concentration to 1 mg/mL using PBS, an equal volume of 2× Laemmli Sample Buffer (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) and 1/10 volume of 1M dithiothreitol solution (Nacalai tesque, Kyoto, Japan) were added [

18]. After boiling the prepared sample at 100°C for 2 min, SDS-electrophoresis was performed using 10 μL of sample per well and 10 μL of rainbow marker (Cytiva, Uppsala, Sweden) added to a 12% precast gel (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) at a constant current of 20 mA. After completion of electrophoresis, the precast gel removed from the fixation plate was applied to a transfer buffer containing 10% methanol (Tris/Glycine Transfer Buffer) for equilibration. The activated 0.2-μm polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (PVDF, Bio-Rad, Herules, CA, USA) was then subjected to overnight electrical transfer at 3-W constant power. After the transfer, the PVDF membrane was immersed in PBS-0.05% Tween 20 (PBS-T), washed by shaking for 5 min, and then immersed in Blocking One (Nacalai tesque, Kyoto, Japan) for 1 h. The cleaned PVDF membrane was cut into 4-mm-wide strips. The washed PVDF membrane was immersed in primary antibodies from the serum samples of each patient, 10-fold diluted with 5% Blocking One-PBS-T and shaken at 4°C overnight. After incubation with the primary antibody, the membrane was rinsed twice with PBS-T and washed three times with shaking for 10 min each. The membrane was then immersed in a secondary antibody [goat anti-human IgE, HRP conjugate (Nordic-MUbio, Susteren, Netherlands)], 2000-fold diluted with 5% Blocking One-PBS-T, and incubated under shaking at room temperature for 1 h. After incubation with the secondary antibody, the membrane was rinsed twice with PBS-T, washed three times by shaking for 10 min, and then incubated with Amersham ECL Prime Western Blotting Detection Reagent (Cytiva, Uppsala, Sweden) for approximately 1 min to detect chemiluminescence using Amersham Imager 680. All experiments were performed at least twice to confirm reproducibility.

2.4. Luciferase Assay

HuRa-40 cells were seeded at a density of 5 × 104 cells/50 µL/well in a clear-bottom 96-well plate (#165306, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and were sensitized overnight using 100-fold diluted serum samples from the three patients (six types). Subsequently, the cells were washed three times with sterile PBS, then added with different concentrations of AWP solution (0, 0.06, 0.22, 0.78, 2.72, 9.52, 33.3, 117, 408, 1429, and 5000 ng/mL) to make a volume of 50 μL/well. The cells were cultured/stimulated for 3 h at 37°C in the incubator. We used goat anti-human IgE antibodies (100 ng/mL; Bethyl Laboratories, Montgomery, TX, USA) as positive controls.

After stimulation, a homogeneous luciferase substrate solution (ONE-Glo TM EX; Promega, Madison, WI, USA) was added to a volume of 50 μL/well, and the plate was placed for 5 min at room temperature. The chemiluminescence (luciferase activity) in each well was measured using GloMax® luminometer (GM3510, Promega). EXiLE results were measured as the fold-change in luciferase activity; cell activity without antigen stimulation was set at 1. The cutoff value was established based on the highest value (+3SD) obtained in the experiments using control serum samples.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Spearman’s rank correlation test was performed to compare the results between the EXiLE and CAP-FEIA methods.

3. Results

3.1. IgE Immunoblotting

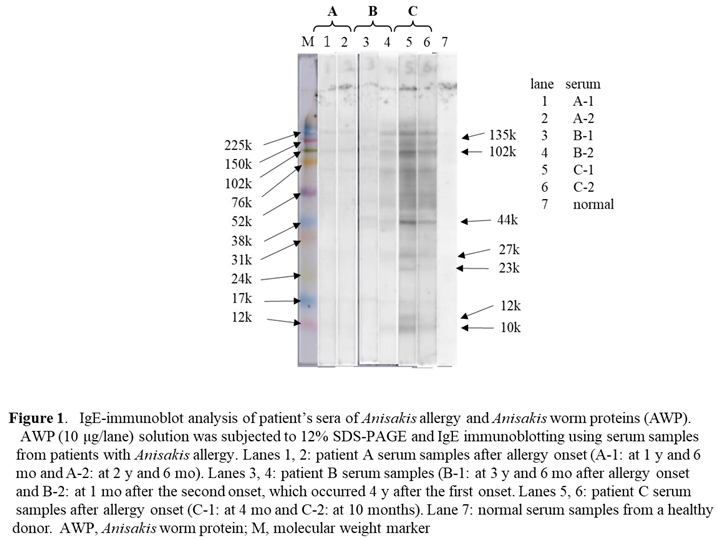

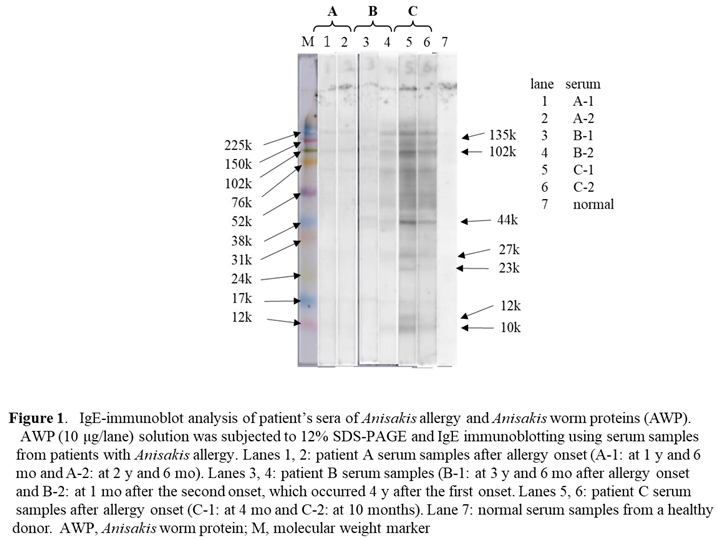

Results of the IgE immunoblot analyses are presented in Figure 1, and those for the serum sample analyses are shown in Table 1. In patient C who had high

Anisakis-specific IgE antibody levels on CAP-FEIA, the serum IgE antibodies were confirmed to be bound to multiple AWPs (Figure 1, lane 5). In particular, according to the identified molecular weight (MW), the major binding proteins seemed to be Ani s 7 (135 kDa) [

19], Ani s 2 (102 kDa) [

20], and Ani s 3 (44 kDa) [

21]. Moreover, the IgE-binding activity of AWP was stronger in serum C-1, which had a CAP-FEIA value of 2400 (Figure 1, lane 5), than in serum C-2, which had a CAP-FEIA value of 87.5 (Figure 1, lane 6). The IgE-binding activity of AWP was weaker in the serum of patient B than in the serum of patient C (Figure 1, lanes 3 and 4). Using serum B-2, which had a CAP-FEIA value of 48.1, a clear IgE immunoblotting pattern was obtained (Figure 1, lane 4), and the main binding proteins had MWs of 135, 102, and 44 kDa. The binding activity in lane 3 using serum B-1 with a CAP-FEIA value of 27.8 was almost the same but weaker than that in lane 4. IgE binding to AWP using the serum samples of patient A was slight (Figure 1, lanes 1 and 2); that in A-1 seemed to be slightly higher than that in A-2 (CAP-FEIA value: 8.06 vs. 6.49).

Based on the results, the main IgE-binding AWPs were considered to have relatively large MWs (>40 kDa), and IgE binding was observed in patients with Anisakis allergy and low serum Anisakis IgE level on CAP-FEIA.

3.2. Luciferase Assay

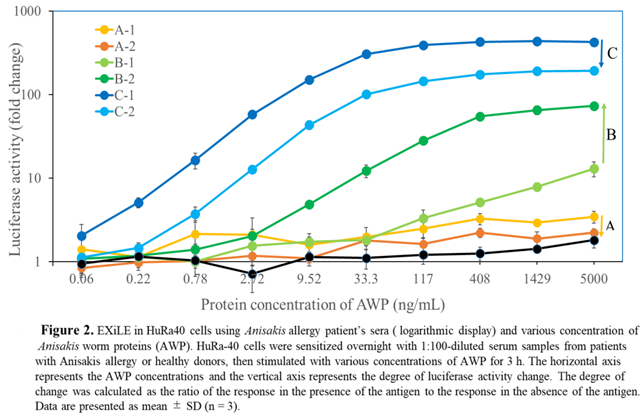

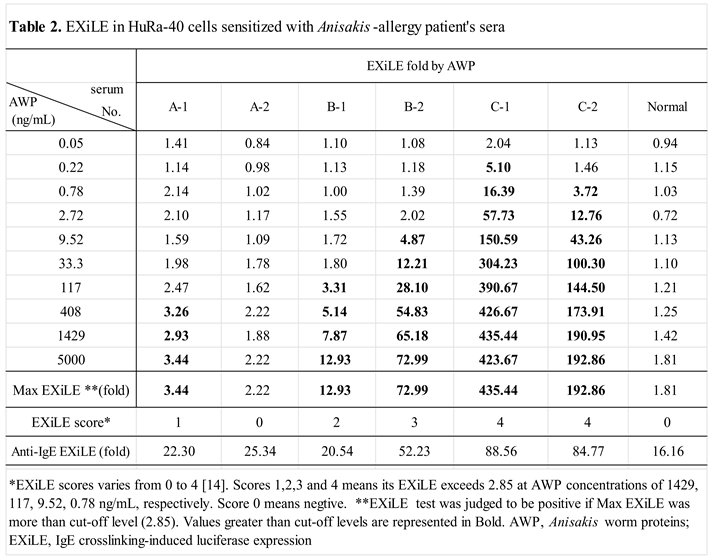

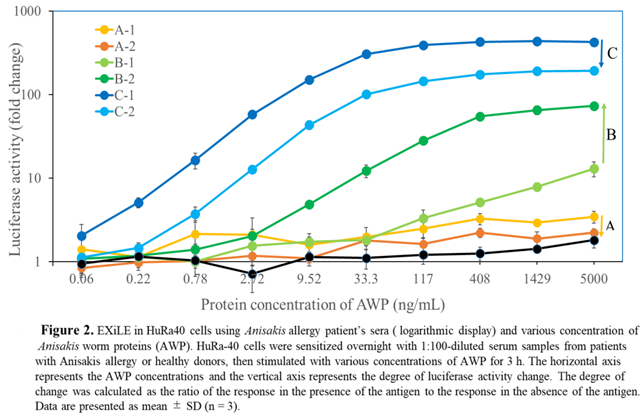

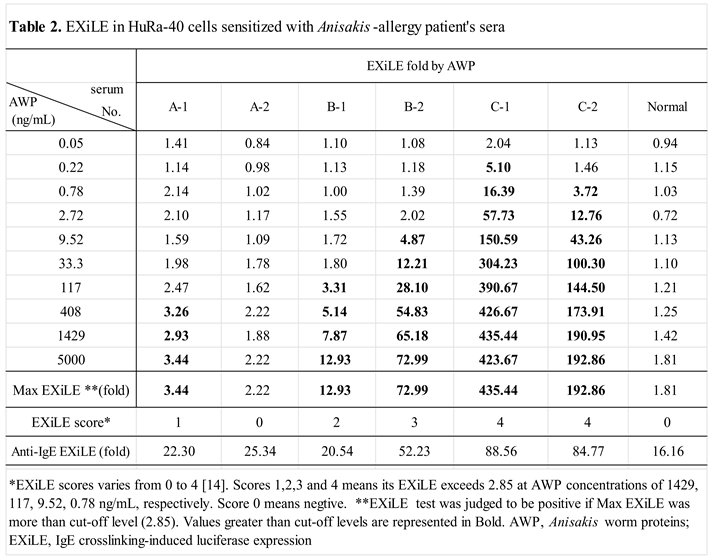

The dose-response curves of AWP concentration and luciferase activity (fold-change) (Figure 2) showed that the AWP concentration limit differed among the serum samples (0.22ng/mL for C-1, 0.78ng/mL for C-2, 9.52 ng/mL for B-2, 117ng/mL for B-1, and 408ng/mL for A-1). These results indicated that the detection limit decreased with increasing antigen-specific IgE value. Table 2 presents the EXiLE scores in the serum samples are shown. The EXiLE scores in serum samples 1, 2, 3, and 4 corresponded to the minimum concentrations of 1429, 117, 9.52, and 0.78 ng/mL, respectively, for AWP response. We analyzed the correlation between the scores of the CAP-FEIA and EXiLE tests using Spearman’s rank test. There was a good correlation between the CAP-FEIA and EXiLE scores (R = 0.91, p < 0.01).

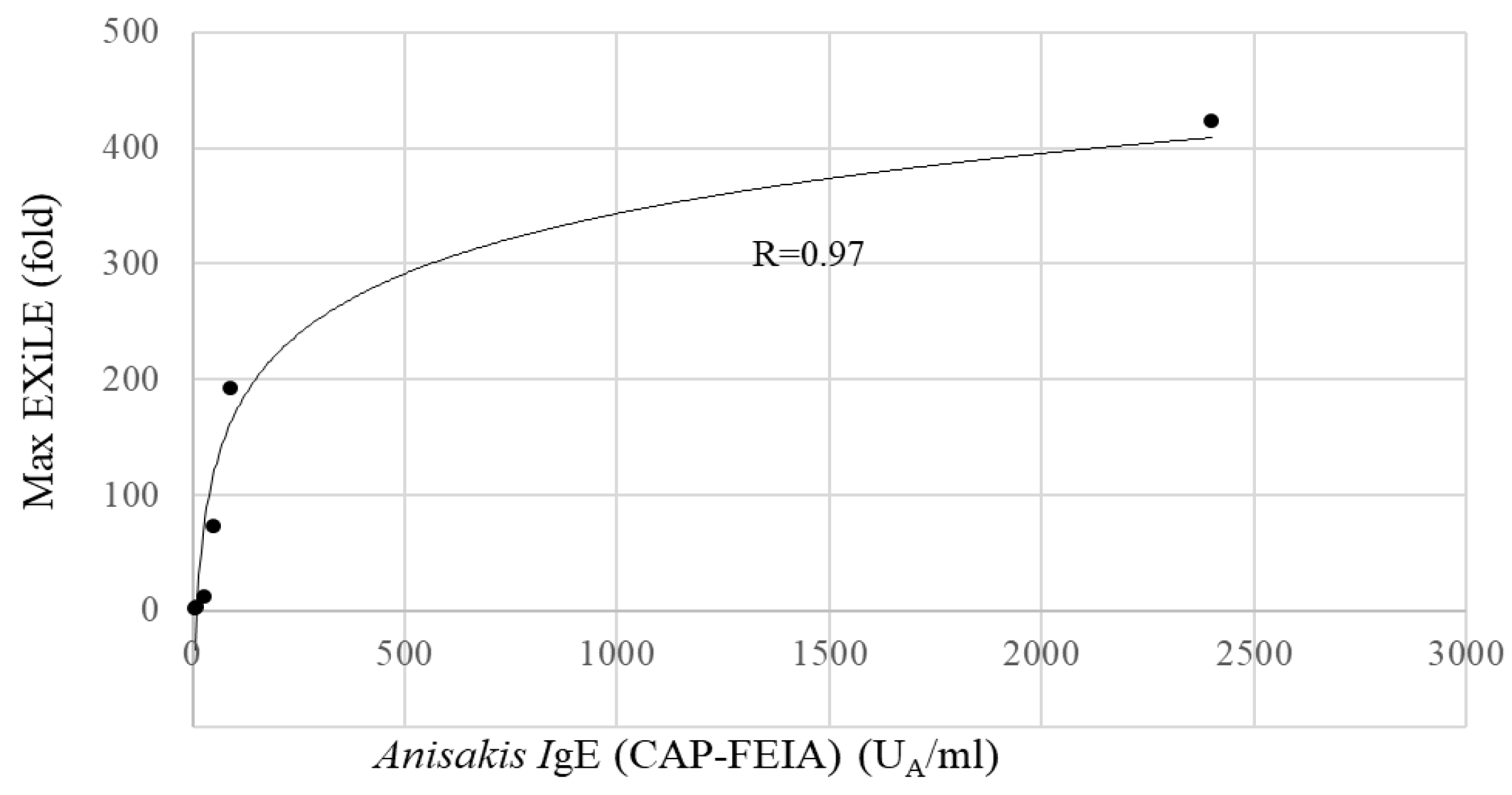

The obtained maximum luciferase activity (EXiLE level) in each serum sample using 5000 ng/mL of AWP demonstrated that as the antigen-specific IgE serum level (CAP-FEIA) increased, the maximum EXiLE level increased and a good correlation between the two was observed ( R = 0.91, p < 0.01) by a Spearman’s rank test.

Figure 3 shows a scatter plot in Excel between the CAP- FEIA value and the maximum EXiLE level and good correlation was observed. Furthermore, the EXiLE level and CAP-FEIA value obtained with 1429, 408, 117, 33.3, and 9.52 ng/mL of AWP were found to have good correlation (R >0.92, p < 0.01).

On subsequent examination of the EXiLE level changes over time, the maximum EXiLE level in patients C and A decreased after the initial blood draw (C-1 to C-2 and A-1 to A-2); that in patient B increased (B-1 to B-2) (Figure 2), and this increase was consistent with the increase in the CAP-FEIA value (Table 1). In patient B, the reason for the increase in maximum EXiLE level over time might be resensitization due to consumption of raw tuna slices before the second blood draw.

4. Discussion

Anisakis allergy, which has been increasingly observed in recent years, has attracted attention as an IgE-dependent immediate allergy. A high blood titer of

Anisakis-specific IgE antibody is the key finding for diagnosing

Anisakis allergy, although results must be carefully interpretated, because some healthy people who have been sensitized do not develop

Anisakis allergy. In addition,

Anisakis was reported to have 16 types of allergen components [

22], but their clinical significance have not been established. Therefore, several issues in the diagnosis of

Anisakis allergy remain to be addressed. In this study, we examined the diagnostic utility of the EXiLE method, a simple in vitro measurement of antigen-specific IgE antibodies that reflect clinical symptoms.

Our results showed a good correlation between the EXiLE level and the CAP-FEIA value and a sufficiently low detection limit of the antigen concentration (0.22 ng/mL). The lowest effective

Anisakis antigen concentration of the EXiLE method was almost the same as the reported lowest effective concentration of peanuts or egg white solution [

14,

16]. These results strongly suggested that the increased luciferase expression in HuRa-40 cells reflects crosslinking of the antigen-specific IgE bound to FcεR1 on mast cells. Therefore, good EXiLE values were obtained using serum samples of patients with

Anisakis allergy. Conversely, based on the detection limit of antigen-specific IgE, sensitivity was slightly lower with the EXiLE method than with the CAP-FEIA method. For example, in serum sample A-2, the CAP-FEIA value was 6.49 U

A/mL and was judged as positive, whereas the EXiLE value was less than the cutoff and was judged as negative. The reason for the negative ExiLE test result for A-2 was unclear; however, considering that this sample was obtained 2.5 years after allergy onset, the functional IgE level might have decreased over time. Nevertheless, the EXiLE method appeared to be useful for the diagnosis of

Anisakis allergy and could supplement other tools, such as the skin prick test, for the determination of specific functional IgE.

In addition, using the EXiLE method in addition to the CAP-FEIA method for long-term management, the reactivity of

Anisakis-specific IgE was found to change over time after the onset of

Anisakis allergy. In one patient, the reason for the increase in maximum EXiLE level over time might be resensitization due to consumption of raw tuna slices before the second blood draw [

12]. Long-term monitoring of antigen-specific IgE in serum is important for dietary guidance for patients with

Anisakis allergy, especially in Japan, where consumption of raw fish is customary. In the future, collecting data from many patients who were monitored may help prevent the onset and recurrence of

Anisakis allergy. Moreover, this novel in vitro EXiLE method for

Anisakis allergy has potential applications for the following: (i) diagnostic supplement for the determination of serum allergen-specific IgE following the CAP-FEIA test, (ii) screening of allergen components in

Anisakis worm extract, and (iii) standardization of allergen extracts for clinical use.

Author Contributions

Investigation, Haruyo Akiyama, Masashi Niwa, Chisato Kurisaka and Yuto Hamada; Supervision, Reiko Teshima; Writing–original draft, Reiko Teshima; Writing-review editing, Haruyo Akiyama, Yuto Hamada and Yuma Fukutomi. All authors will be updated at each stage of manuscript processing, including submission, revision, and revision reminder, via emails from our system or the assigned Assistant Editor.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Abbreviations

| CAP-FEIA |

CAP-fluorescence enzyme immunoassay |

| IgE |

immunoglobulin E |

| HRP |

horseradish peroxidase |

| PBS |

phosphate-buffered saline |

| SDS |

sodium dodecyl sulfate |

| CBB |

Coomassie Brilliant Blue |

| SD |

standard deviation |

References

- Nieuwenhuizen, N.E.; Lopata, A.L. Anisakis – A food-borne parasite that triggers allergic host defences. Int. J. Parasitol. 2013, 43, 1047–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Thiel, P.H. Anisakiasis. Parasitol. 1962, 52, 16–17. [Google Scholar]

- Kasuya, S.; Hamano, H.; Izumi, S. Mackerel-induced urticaria and Anisakis. Lancet 1990, 335, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez de Corres, l.; Audicana, M.; Del Pozo, M.D.; Munoz, D.; Fernandez, E.; Navarro, J.A.; Garcia, M.; Diez, J. J. Anisakis simplex induces not only anisakiasis: report on 28 cases of allergy caused by this nematode. J. Investig. Allergol. Clin. Immunol. 1996, 6, 315–319. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hamada, Y.; Nakatani, E.; Watai, K.; Iwata, M.; Nakamura, Y.; Ryu, K.; Kamide, Y.; Sekiya, K.; Fukutomi, Y. Effects of raw seafood on the risk of hypersensitivity reaction recurrence in patients with an Anisakis allergy: A retrospective observational study in Japan. Allergol. Int. 2023, 73, 171–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanovic, J. ; Baltic, M.Z.; Boskovic, M.; Kilibarda, N.; Dokmanovic, M.; Markovix,R.; Janjic, J.; Baltic, B. Anisakis allergy in human. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 59, 25–29. [Google Scholar]

- EFSA Panel on Biological Hazards. Scientific opinion of April 2010 on risk assessment of parasites in fishery products. EFSA J. 2010, 8, 1543.

- Daschner, A.; Alonso-Gomez, A.; Cabanas, R.; Suarez-de-Parga, J.M.; Lopez-Serrano, M.C. Gastroallergic anisakiasis:borderline between food allergy and parasitic disease-clincal and allergologic evaluation of 20 patients with confirmed acute parasitism by Anisakis simplex. J.Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2000, 105, 176–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nieuwenhuizen, N.E.; Lopata, A.L. Jeebhay, M. F.; Herbert, D.R.; Robins, T.G.; Brombacher, F. Exposure to the fish parasite Anisakis causes allergic airway hyperreactivity and dermatitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol.. 2006, 117, 1098–1105. [Google Scholar]

- Baird, F.J.; Gasser, R.B.; Jabbar, A.; Lopata, A.L. Foodborne anisakiasis and allergy. Mol. Cell. Probes 2014, 28, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morishima, R.; Motojima, S.; Tsuneishi, D.; Kimura, T.; Nakashita, T.; Fudouji, J.; Ichikawa, S.; Ito, H.; Nishino, H. Anisakis is a major cause of anaphylaxis in seaside areas: An epidemiological study in Japan. Allergy 2019, 75, 441–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamada, Y. ; Sugano,S. ; Kamide, Y.; Sekiya, K.; Fukuttomi, Y. Anisakis allergy verusus gastric anisakiasis: a case of repeated Anisakis-assosiated symptoms. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Global 2024, 3, 100207. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Muñoz, M.; Luque, R.; Nauwelaers, F.; Moneo, I. Detection of Anisakis simplex-induced basophil activation by flow cytometry. Cytom. Part B: Clin. Cytom. 2005, 68B, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akiyama, H.; Kurisaka, C.; Kumasaka, K.; Nakamura, R. Novel IgE crosslinking-induced luciferase expression method using human-rat chimeric IgE receptor-carrying mast cells. J. Immunol. Methods 2024, 529, 113682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akiyama, H.; Kurisaka, C.; Muramatsu, D.; Takada, S.; Toyama, K.; Yoshioka, K. , Consideration of the EXiLE test for predicting anaphylaxis after diclofenac ethalhyaluro- nate administration. J. Immunotox. 2024, 21, 2417758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, R.; Uchida, Y.; Higuchi, M.; Tsuge, I.; Urisu, A.; Teshima, R. A convenient and sensitive allergy test: IgE crosslinking-induced luciferase expression in cultured mast cells. Allergy 2010, 65, 1266–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abe, Z.; Yagi, K. Identification of anisakinae larvae by diasnostic PCR. Seikatsu Eisei 2005, 49, 168–171. [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli, U.K. Cleavage of Structural Proteins during the Assembly of the Head of Bacteriophage T4. Nature 1970, 227, 680–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, E.; Anadón, A.M.; García-Bodas, E.; Romarís, F.; Iglesias, R.; Gárate, T.; Ubeira, F.M. Novel sequences and epitopes of diagnostic value derived from the Anisakis simplex Ani s 7 major allergen*. Allergy 2008, 63, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Pérez, J.; Fernández-Caldas, E.; Marañón, F.; Sastre, J.; Bernal, M.L.; Rodríguez, J.; Bedate, C.A. Molecular Cloning of Paramyosin, a New Allergen of Anisakis simplex. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2000, 123, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asturias, J.A.; Eraso, E.; Martı́nez, A. Cloning and high level expression in Escherichia coli of an Anisakis simplex tropomyosin isoform. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2000, 108, 263–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, M.; Shimakura, K.; Kobayashi, Y. ; Yoshikawa, T,; Hashimoto, T. ; Azuma, N.; Matsui,K. Component analysis of three anisakiasis allergy cases in our department -including comparison with 10 existing reports-. J. Soc. Allergol. 2023, 72, 1154–1157. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).